Abstract

SLC1A5, short for solute carrier family 1 member 5, is a neutral amino acid transporter whose expression has been reported to be upregulated in various cancers, including esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Despite this, little has been described regarding the immunological involvement of SLC1A5 expression in the tumor microenvironment of ESCC. Given this, we adopted in silico analyses together with a wet lab strategy to investigate the prognostic and clinicopathological meaning of SLC1A5 expression in ESCC. In silico analyses of SLC1A5 expression data available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database revealed that SLC1A5 expression was unrelated to the prognosis of ESCC, which holds true when extended to other types of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC). Further analyses revealed that SLC1A5 expression correlated markedly with the infiltration density of effector CD8+ T cells in ESCC, and the same was true for HNSC and LUSC when extrapolated. As experimental confirmation, multiplexed immunofluorescent staining was undertaken to verify the correlation between SLC1A5 expression and infiltration of CD8+ T cells in a tissue microarray prepared from ESCC and matched normal control tissues. Our data confirmed that SLC1A5 expression was not associated with prognosis but was associated with the exclusion of CD8+ T cells. Taken together, all the data we curated strongly support the notion that SLC1A5 expression is associated with CD8+ T-cell exclusion in the tumor microenvironment of SCC.

Keywords: SLC1A5, Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), CD8+ T, Prognosis, Exclusion

1. Introduction

SLC1A5, also known as ASCT2 [1], belongs to the SLC1 family and is localized in the plasma membrane of cells, playing a key role in glutamine and neutral amino acid transport [2,3] in various cancer cells. Aside from its fundamental physiological role as a transporter of amino acids to support the tumor metabolome, a great deal of evidence has shown that SLC1A5 has many additional functions that have been reported to be able to foster the proliferation and development of tumors [4], therefore making it an attractive target for cancer therapy [5]. Despite these pioneering reports, the immunological and clinicopathological involvement of SLC1A5 expression in the tumor microenvironment of ESCC remains unknown.

The tumor microenvironment (TME), where different cellular players coexist, is a crucial mediator of cancer progression and therapeutic outcome [6]. The major players include tumor, immune and various supporting cells, including stromal, fibroblasts and endothelial cells [7]. Circulating in the blood, immune cells can be attracted, thereby entering tumor tissues, by chemokines secreted by tumor or inflammatory cells. Responsible for tumor cell recognition and elimination, CD8+ T cells play a pivotal role in the antitumor response [8]. Intriguingly, infiltrating cytotoxic T cells express inhibitory receptors, such as PD-1, LAG-3 and Tim-3 [9], whose function under physiological circumstances is to contract the immune response upon binding to their corresponding ligands that are expressed by tumor cells. Many tumor cells can take advantage of this mechanism to escape T-cell attack. Several studies [8,10,11] have meta-analyzed that the infiltration density of CD8+ T cells is linked with overall survival and reviewed [12] that the infiltrating density of CD8+ T cells in cancerous tissues was influenced by many factors, such as abnormal signaling pathways [13] and genes [14] in tumor cells. A question naturally aroused here is whether there will be a relationship between SLC1A5 expression and the infiltrating density of CD8+ T cells in ESCC that has been little described in SCC remains to be established.

Initial observations [15] suggested that the immunological implication of SLC1A5 was from breast cancer, where altered glutamine pathways mediated by SLC1A5 and SLC7A5 seemed to have a heavy impact on the composition of immune cell infiltrates in breast cancer. This view has been further strengthened by in silico analyses [16] performed subsequently on the basis of multiple cancers in which the expression of SLC1A5 correlated highly with tumor immune cell infiltration, especially in liver cancer. Taking these previous data together, we hypothesized that SLC1A5 may also be immunologically involved in the TME of SCC. Therefore, to understand the immunological and prognostic implications of SLC1A5 expression in the TME of ESCC, in silico analyses along with a wet lab strategy were undertaken to investigate the role of SLC1A5 mainly in ESCC, which was then expanded and extended to other types of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that are commonly seen, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC). The data from in silico analyses showed that SLC1A5 expression was unrelated to the prognosis of patients with SCC but associated with the exclusion of infiltrating CD8+ T cells in the TME of ESCC, as evidenced by multiplexed immunofluorescent staining. Overall, we revealed that SLC1A5 expression was associated with the exclusion of infiltrating CD8+ T cells in the TME of ESCC, strongly supporting the notion that elevated SLC1A5 could prevent CD8+ T cells from infiltrating the TME of SCC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. SCC data acquisition and analyses

Making full use of SLC1A5 mRNA expression data available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [17,18] and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [19,20], this study took advantage of online bioinformatic analysis tools, including Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) [21] 2021 version [22], an integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions (TISIDB) [23] and Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) 2.0 version [24], to assay SLC1A5 mRNA expression in SCC, including ESCC, HNSCC and LUSC, three main types of SCC included in the TCGA database. Data regarding SLC1A5 mRNA expression in other types of carcinoma, other than SCC, were disregarded.

2.2. Tissue microarray

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, and 87 paired ESCC tissues and matched normal samples and 6 additional unpaired ESCC samples were enrolled. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant involved. The sample tissues were clinically staged and graded following hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, according to the World Health Organization criteria, 2016 version [25]. None of the samples were collected from patients undergoing chemo- or radiotherapy before surgery. The generation of the ESCC tissue microarray used for multiplexed immunofluorescent staining [26] was outsourced to Shanghai Outdo Biotech. Co. Ltd. (Superchip, Shanghai, China). Eighty-seven paired ESCC tissues and their matched normal dots and an additional 6 unpaired ESCC dots were arranged on a single slide. The clinicopathological variables comprising demographics, clinical stage, TNM classifications, and overall survival were retrieved when available. Notably, of 93 cases, 5 cases had missing clinical stage and invasion information, and 3 cases had missing gross classification when analyzing the clinicopathological significance of SLC1A5 expression.

2.3. Multiplexed immunofluorescent staining

As described elsewhere [26], briefly, after blocking with 3% hydrogen peroxide in Tris buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) for 5 min, the ESCC tissue microarray was then incubated with the primary rabbit antibody for SLC1A5 (20350-1-AP; 1:1000; Proteintech, China) for 30 min. Slides were then incubated using horseradish peroxidase labeled anti-rabbit Envision (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for 5 min each step before visualization using Opal 570 tyramide signal amplification (TSA) (1:50) for another 5 min. Subsequently, antigen retrieval was conducted again to prepare the slides for the next antibody. Employing this Opal staining approach, all samples were sequentially stained with the primary mouse antibody for CD8a (#60168, clone D4 W2Z; 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) and visualized with Opal 540 TSA (1:50). The slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (1:2000) for nuclear visualization and subsequently cover-slipped with fluorescence antifade mounting medium (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). In the experiment, the negative control was set up as normal IgG from the same species, which will not cross-react with antigen when used at the recommended concentration, whereas breast cancer tissue [15] on which SLC1A5 has been reported to be expressed was set as the positive control.

2.4. Multispectral image acquisition and analysis

ESCC tissue microarrays that underwent multiplex fluorescent staining for each fluorophore were imaged using Vectra Multispectral Imaging System version 2 (Perkin Elmer, USA) under the appropriate fluorescent filters (green for Opal 570, blue for Opal 540 and DAPI) to yield the spectral library required for multispectral analysis. A whole slide scan of the multiplex tissue sections produced multispectral fluorescent images visualized in Phenochart (Perkin Elmer, USA) and imaging at 20 × power for further analysis. Analysis of the multispectral images was conducted using inForm image analysis (Perkin Elmer, USA). Representative images of each sample used to establish tissue segmentation, which was applied to batch analysis of all high-power multispectral images. The positivity threshold of each marker was then determined and recorded for further data analysis.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were compared between two groups using Student’s t tests. The F test was used to compare the variances of two samples. The Wilcoxon test was used for data that were not normally distributed. For categorical data, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was employed. Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyze the relationship between the mRNA level of SLC1A5 and infiltration of CD8+ T cells. Regarding the correlation between the number of SLC1A5+ cells and CD8a+ cells, Spearman correlation was adopted. The overall survival rate was analyzed by the log-rank test when plotting the Kaplan‒Meier curve. The cutoff score was determined using the Youden index approach when stratifying the high and low expression of SLC1A5 in the epithelial or stromal compartment of ESCC. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version V.16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

3. Results

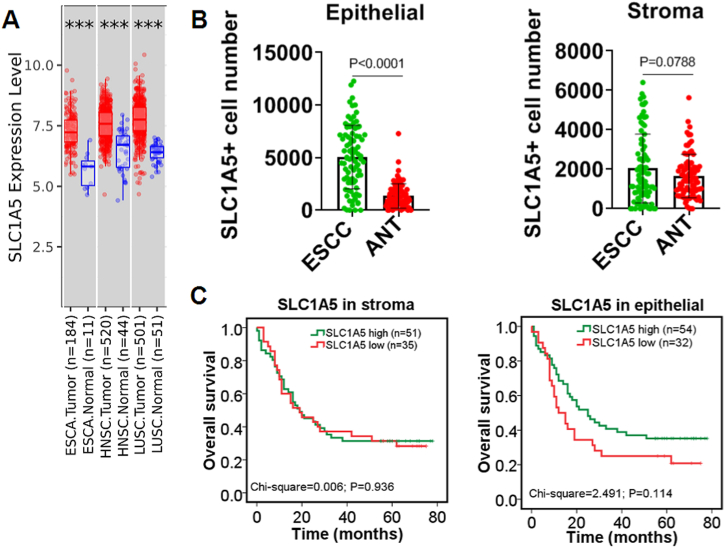

3.1. Elevated SLC1A5 was unrelated to the overall prognoses of SCC

To understand the expression pattern of SLC1A5 in SCC tissues, we analyzed, taking advantage of several online bioinformatic analysis websites, the mRNA level of SLC1A5 in SCC, including ESCA, HNSCC and LUSC, in our setting. The data revealed that SLC1A5 was significantly upregulated in SCC tissues in comparison with normal control tissues (Fig. 1A). Next, to confirm SLC1A5 expression in ESCC tissues we collected on our own, multiplexed immunofluorescent staining was undertaken to observe the expression of SLC1A5 (Supplementary figure s1). It should be noted that in scanning the slide, the Opal 570 wave length denotes SLC1A5 staining (Supplementary figure s2). In the epithelial compartment of ESCC, the number of ESCC cells with SLC1A5-positive staining was much greater than that of the corresponding adjacent normal tissue (ANT). In the stromal compartment of ESCC, no significant difference was identified in the number of SLC1A5-positive cells between ESCC and its ANT in our experimental setting (Fig. 1B). Prognostically, the expression of SLC1A5, whether in the epithelia or stroma, was found to be unrelated to the overall survival of patients with ESCC (Fig. 1C). To verify the prognostic data we calculated, two different kinds of online bioinformatic databases (TISIDB and TIMER 2.0 version) were used. Consistent with our experimental data, bioinformatic data available from the TISIDB and TIMER 2.0 databases corroborated each other, supporting that SLC1A5 expression was unassociated with overall prognosis in SCC, including ESCA, HNSCC and LUSC (Supplementary figures s3 and s4). Taken together, all the data we gleaned here strongly indicated that overexpressed SLC1A5 was unrelated to the overall prognoses of SCC.

Fig. 1.

Upregulated SLC1A5 was unrelated to the overall prognosis of ESCC. A: Differential expression of SLC1A5, as in silico analyzed by TIMER 2.0 version database (http://timer.cistrome.org/), between squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adjacent normal tissue (ANT) controls. ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; HNSC, head and neck squamous carcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous carcinoma. The statistical significance computed by the Wilcoxon test is annotated by the number of stars (***p < 0.001). B: Quantitative analyses of the difference in SLC1A5-positive staining cell number between ESCC and paired normal controls, as evidenced by multiplexed immunofluorescent staining, in epithelial and stromal sections. Independent sample T tests were used. n = 86 cases for ESCC and ANT. C: Prognostic meaning of SLC1A5 expression in the epithelium and stroma of ESCC, totaling 86 cases. The log-rank test was employed when Kaplan‒Meier survival curves were plotted.

3.2. SLC1A5 was associated with the exclusion of CD8+ T cells in SCC

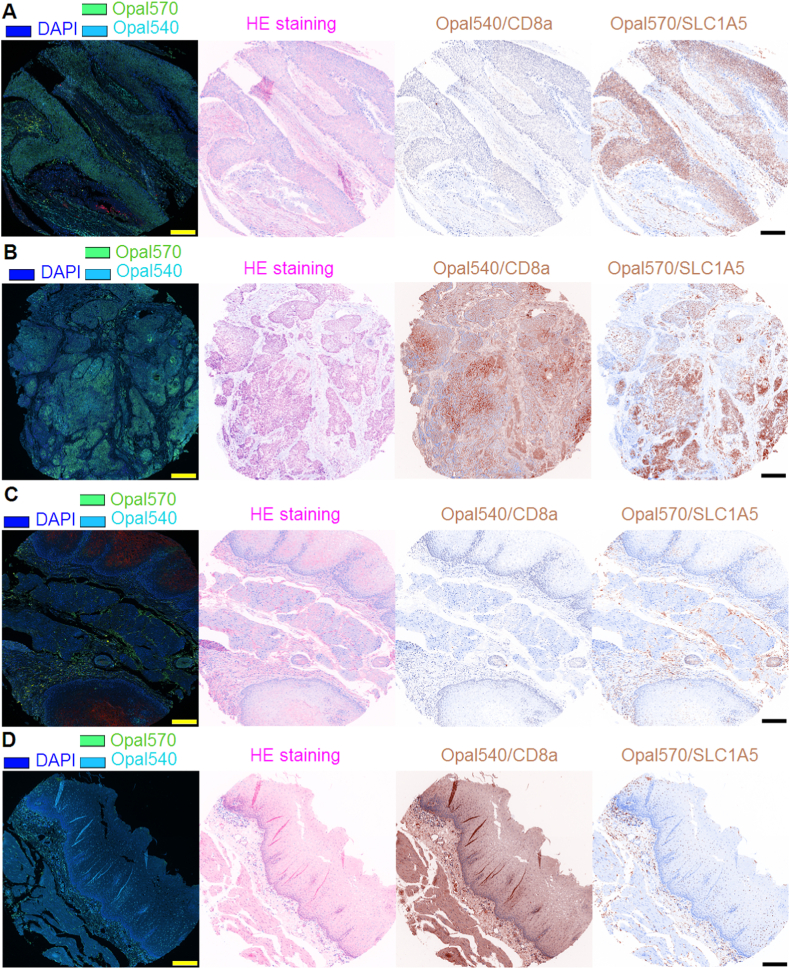

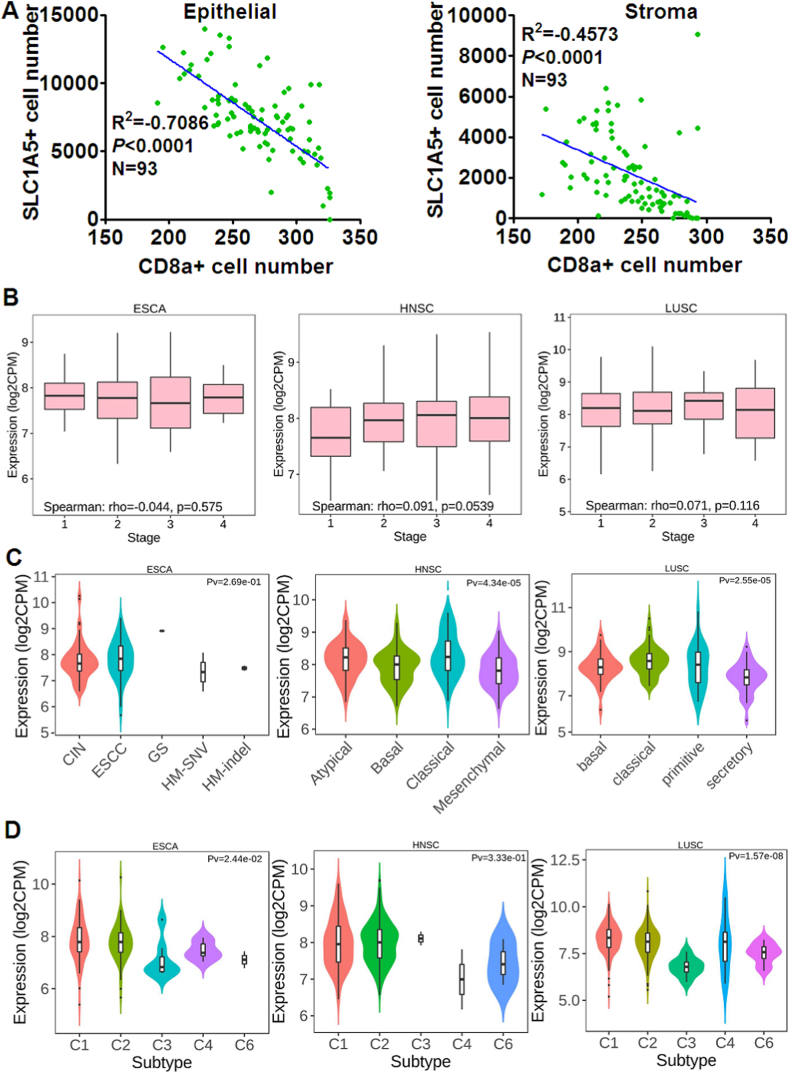

Having learned that SLC1A5 expression was unrelated to the overall prognosis of SCC, we next analyzed the infiltrating density of CD8+ T cells along with SLC1A5 expression in ESCC and paired ANT, discovering a hidden but interesting trend that in both ESCC and ANT where SLC1A5 was elevated, the infiltrating density of CD8+ T cells was remarkably lower and vice versa (Fig. 2A–D), explicitly suggesting that SLC1A5 might prevent CD8+ T cells from infiltrating ESCC tissues. Returning to the online bioinformatic databases, we were in an attempt to confirm the potential correlation between SLC1A5 expression and infiltration of CD8+ T cells in SCC, exhibiting that whichever databases we took advantage of including GEPIA 2021 version, TISIDB and TIMER 2.0 version, SLC1A5 mRNA expression level remarkably and negatively correlated with the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in ESCA, HNSCC and LUSC (Fig. 3A–C). To further confirm the indication provided by the databases we described above, we quantitatively analyzed the data from our multiplexed immunofluorescent staining of the ESCC tissue microarray using the Spearman correlation analysis approach. Our data were completely in agreement with those displayed in the database (Fig. 4A). All the data we curated here strongly and explicitly indicate that SLC1A5 was markedly associated with the exclusion of CD8+ T cells in SCC.

Fig. 2.

SLC1A5 and CD8a expression, as exemplified by multiplexed immunofluorescent staining, in ESCC. A–B: ESCC dots where the scale bar represents 100 μm. C–D: adjacent normal tissue (ANT) dots where the scale bar denotes 100 μm. DAPI was used for nuclear labeling. HE, hematoxylin-eosin; of these four dots presented, A and C actually matched those from the same patient, whereas B and D were paired from the same patient.

Fig. 3.

SLC1A5 mRNA levels were significantly and negatively correlated with the infiltration level of CD8+ T cells in ESCA, HNSC and LUSC. A: As analyzed by TIMER version 2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/), a significant negative correlation between the SLC1A5 mRNA level and infiltration of CD8+ T cells was displayed in ESCA, HNSC and LUSC. B: Similarly, calculated to be remarkably inverse, the correlation between the SLC1A5 mRNA level and the infiltration level of CD8+ T cells was analyzed using GEPIA 2021 version (http://gepia2021.cancer-pku.cn/) in ESCA, HNSC and LUSC. C: A significantly inverse correlation can be achieved through the TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of SLC1A5 expression across immune and molecular subtypes of ESCA, HNSCC and LUSC. A: In ESCC, regardless of the epithelial or stromal compartment, the number of cells stained positively with SLC1A5 significantly and negatively correlated with the number of cells stained with CD8a in the ESCC tissue microarray we performed, totaling 93 dots. B: Correlation between SLC1A5 mRNA level and clinical stage, as analyzed by the TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/), in ESCA, HNSC and LUSC. C: Analysis by the TISIDB database. The associations with molecular subtypes of ESCA, HNSC and LUSC classified by the TCGA database are shown. For ESCA, there were four molecular subtypes available from the TISIDB database, including chromosomal instability, CIN (CIN = 74), esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, ESCC (ESCC = 90), genome stability, GS (GS = 1), hypermutated single nucleotide variation, HM-SNV (HM-SNV = 2) and hypermutated insertion or deletion (indel), HM-indel (HM-indel = 2). Of HNSC, 67 were atypical, 87 were basal, 48 were classical and 74 were mesenchymal. For LUSC, the molecular subtypes included 42 basal cases, 63 classical cases, 26 primitive cases and 39 secretory cases. D: Likewise, associations were analyzed between SLC1A5 mRNA and immune subtypes of ESCA, HNSC and LUSC, classified by TCGA database. With regard to the immune subtypes of ESCA, HNSCC and LUSC, C1 stands for wound healing, C2 denotes IFN-γ dominant, C3 represents inflammatory, C4 is lymphocyte depleted, C5 stands for immunologically quiet and C6 TGF-β dominant. In ESCA, C1 = 71, C2 = 87, C3 = 7, C4 = 6, and C6 = 2; in HNSC, C1 = 128, C2 = 379, C3 = 2, C4 = 2, and C6 = 3; and in LUSC, C1 = 275, C2 = 182, C3 = 8, C4 = 7, and C6 = 14.

3.3. Clinicopathological significance of SLC1A5 expression in epithelial and stromal compartments of ESCC

Next, further evaluation was performed on the association of SLC1A5 expression with clinical stage and molecular/immune subtypes in SCC. In ESCA in terms of stage, no marked difference can be observed between stages ranging from I to 4 (Fig. 4B); the same goes for LUSC as well. In HNSC, there was an approaching but not achieving statistical trend (p = 0.0539) of the SLC1A5 mRNA level, running the gamut of clinical stages from 1 to 4 (Fig. 4B). In our own setting, we found that SLC1A5 expression was not associated with clinical stage. A little disappointingly, no other significant association was observed between SLC1A5 expression and clinicopathological parameters, regardless of the epithelial or stromal compartment (Table 1). With regard to tumor grade, no data were available for ESCA and LUSC from the TISIDB database, but there was an extremely significant correlation between SLC1A5 mRNA expression and tumor grade in HNSCC (Supplementary figure 5). Making full use of data concerning SLC1A5 mRNA expression, we found no significant difference between molecular subtypes of ESCA provided by TCGA, including chromosomal instability (CIN), ESCC, genome stability (GS), hypermutated single nucleotide variation (HM-SNV) and hypermutated insertion or deletion (indel) (HM-indel). However, there were significant differences in SLC1A5 mRNA expression between the molecular subtypes of HNSC and LUSC (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the expression difference of SLC1A5 mRNA expression between different immune subtypes of ESCA, HNSC and LUSC was also evaluated, revealing that aside from HNSC, there were significant differences in SLC1A5 mRNA expression between immune subtypes of both ESCA and LUSC (Fig. 4D). Noticeably, the SLC1A5 mRNA level was shown to be lowest in the inflammatory subtype of ESCA and LUSC, suggesting that SLC1A5 might negatively regulate inflammation in SCC.

Table 1.

Expression significance of SLC1A5 in the epithelial and stroma compartments of ESCC.

| parameters | N | SLC1A5 in epithelial |

χ2 | P | N | SLC1A5 in stroma |

χ2 | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | L | H | L | ||||||||

| ANT | 87 | 37 | 50 | 7.898 | 0.007 | 87 | 40 | 47 | 3.661 | 0.073 | |

| ESCC | 93 | 59 | 34 | 93 | 56 | 37 | |||||

| Gender | Male | 77 | 47 | 30 | 1.113 | 0.396 | 77 | 46 | 31 | 0.042 | 1.000 |

| Female | 16 | 12 | 4 | 16 | 10 | 6 | |||||

| Age (years) | >60 | 72 | 48 | 24 | 1.431 | 0.304 | 72 | 45 | 27 | 0.695 | 0.453 |

| ≤60 | 21 | 11 | 10 | 21 | 11 | 10 | |||||

| Differentiation | Well-moderate | 74 | 49 | 25 | 1.203 | 0.296 | 74 | 45 | 29 | 0.054 | 1.000 |

| poor | 19 | 10 | 9 | 19 | 11 | 8 | |||||

| Stage | Ⅰ-Ⅱ | 48 | 32 | 16 | 1.415 | 0.531 | 48 | 30 | 18 | 0.958 | 0.615 |

| Ⅲ-IV | 40 | 25 | 15 | 40 | 24 | 16 | |||||

| T classification | T1-T2 | 24 | 18 | 6 | 1.864 | 0.222 | 24 | 16 | 8 | 0.562 | 0.481 |

| T3-T4 | 69 | 41 | 28 | 69 | 40 | 29 | |||||

| N classification | N0 | 45 | 29 | 16 | 0.038 | 1.000 | 45 | 28 | 17 | 0.147 | 0.832 |

| N1–N3 | 48 | 30 | 18 | 48 | 28 | 20 | |||||

| Invasion | mucosa | 60 | 35 | 25 | 2.036 | 0.406 | 60 | 34 | 26 | 1.326 | 0.519 |

| submucosa | 28 | 20 | 8 | 28 | 18 | 10 | |||||

| Size (cm3) | <16.25 | 46 | 29 | 17 | 0.006 | 1.000 | 46 | 28 | 18 | 0.016 | 1.000 |

| ≥16.25 | 47 | 30 | 17 | 47 | 28 | 19 | |||||

| Gross classification | Ulcerative | 51 | 27 | 24 | 9.192 | 0.076 | 51 | 25 | 26 | 8.964 | 0.083 |

| Fungating | 8 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 2 | |||||

| Medullary | 24 | 18 | 6 | 24 | 19 | 5 | |||||

| Intraluminal | 8 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 2 | |||||

4. Discussion

In the present investigation, both bioinformatic analyses and wet lab strategy were undertaken to evaluate the clinicopathological and prognostic meaning of SLC1A5 expression in ESCC, showing that overexpressed SLC1A5 was of no prognostic meaning but associated with exclusion of CD8+ T cells in ESCC, which can be extrapolated to other types of SCC including HNSCC and LUSC that is also tenable. Our findings have important implications for understanding and enriching the role of SLC1A5 in the tumor microenvironment of SCC from the perspective of immune regulation.

Generally, having a high rate of glutamine uptake and exhibiting glutamine addiction, tumor cells underwent metabolic reprogramming to fit into the new microenvironment where tumor cells were surrounded. Numerous studies have revealed that glutamine metabolism plays a key role in the progression of many tumors, including SCC [5]; therefore, targeting glutamine uptake through the transporter SLC1A5 will be thought of as a promising and effective strategy for the treatment of cancer. In effect, many investigators subscribed to this viewpoint, with a couple of literature reviews [3,27] published to support the targetability of SLC1A5 in the curing of cancer. A good example is from a study on HNSCC [5], revealing that knockdown of SLC1A5 can strengthen the response to cetuximab in HNSCC. A similar phenomenon described regarding the biological roles of SLC1A5 can also be observed in other kinds of carcinoma, other than SCC. Because our study was short of exploration of the basic biological role of SLC1A5 in SCC, we will not dwell upon this. Instead, returning to our initial question, we will place more emphasis on the discussion surrounding the clinicopathological and prognostic meaning of SLC1A5 expression in the setting of SCC that we have been concerned with.

In terms of prognostic significance, analyses of previous research performed on SLC1A5 in SCC, including HNSCC [5], tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) [28], laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) [29], ESCC [30] and oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [31], supported that elevated SLC1A5, relative to paired normal controls, was pronouncedly associated with poor overall survival of SCC. Inconsistently, we did not observe the phenomenon that upregulated SLC1A5 can predict shorter survival in ESCC, not to mention the prognostic analysis data available from bioinformatic databases we took advantage of. The possible reasons leading to the discrepancy were unknown but may be due to technical aspects. Take, for instance, sensitivity in approach taken to detect SLC1A5 expression, specificity and correctness of primary antibody against SLC1A5, cutoff score chosen to stratify the high/low expression of SLC1A5 and so on. In the previous studies reviewed above, immunohistochemistry was used most frequently. However, multiplexed immunofluorescent staining with more sensitivity was adopted in our research. Different primary antibodies against SLC1A5 from different sources were so predominant that they cannot be overlooked. All these factors undoubtedly have a certain effect on the outcome analysis of survival.

Although SLC1A5 expression was unrelated to the prognosis of ESCC, which holds true when extended to other types of SCC, including HNSCC and LUSC, with the aid of bioinformatic analysis, it will not discourage us from further exploring SLC1A5 and mining the data available from databases concerning SCC. In particular, in light of the evidence from previous studies demonstrating that glutamine deprivation [32] can overcome tumor immune evasion and that enhanced glutamine uptake [15] can influence the composition of infiltrating immune cells in breast cancer, one hypothesis naturally emerges from these earlier findings is that SLC1A5, acting as a transporter of glutamine, might have an unknown relationship that needs to be established with the infiltration of immune cells in ESCC. Driven by this hypothesis, we reanalyzed the correlation between the SLC1A5 mRNA level and the number of infiltrating effector CD8+ T cells in SCC encompassing ESCA, HNSCC and LUSC and discovered that there was an extremely significant negative correlation between the SLC1A5 mRNA level and the infiltrating density of effector CD8+ T cells in SCC. CD8+ T cells can be classified into activated CD8+ T cells (Act CD8+ T cells), central memory CD8+ T cells (Tcm CD8+) and effector memory CD8+ T cells (Tem CD8+) [33]. We arrived at the conclusion through bioinformatic mining that SLC1A5 was associated with the exclusion of CD8+ T cells and only applied to Tem CD8+ cells in the setting of SCC. This bioinformatic finding was subsequently corroborated by our experimental data showing that elevated SLC1A5 was remarkably associated with the exclusion of CD8a+ T cells in ESCC tissues. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report striking up the relationship between SLC1A5 expression and the exclusion of CD8+ T cells in the context of SCC. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism underlying how SLC1A5 expression could influence the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in the TME of SCC remains unclear and beyond the scope of this study.

Recently, a growing body of literature has investigated the biological function of SLC1A5 in various types of cancer; in contrast, little attention has been given to the clinicopathological significance of SLC1A5 in SCC, with the exception of only one study [34] conducted on epithelial ovarian cancer, reporting that SLC1A5 expression was associated with clinicopathological parameters, including stage and pathological grade. Herein, we did not observe that SLC1A5 expression was correlated with tumor grading and clinical staging of ESCC. There was agreement between our experimental data and bioinformatic analysis of ESCA, displaying that no correlation was found between clinical stage and SLC1A5 mRNA expression in ESCA. When extended to HNSCC and LUSC, data from bioinformatic analyses showed that there was an approaching but not significant trend toward a correlation between SLC1A5 mRNA levels and clinical stage only in HNSCC. Furthermore, to make the best use of data included by TCGA, we accidently assayed the correlation between SCL1A5 mRNA levels and molecular/immune subtypes of SCC, which has never been reported before. These bioinformatically analyzed correlations obviously warrant experimental confirmation with SCC tissues in a large sample size in the future. Furthermore, extra care should be taken when exploiting ESCA data available from TCGA. In our investigation, for example, of ESCA data with a total of 184 ESCA cases included in the TCGA database, the number of ESCC cases was 90, accounting for approximately fifty percent, with the remainder being esophageal adenocarcinoma, which is histopathologically and etiologically different from ESCC. When exploiting ESCA data available from TCGA in our investigation, we conflated ESCC with esophageal adenocarcinoma, analyzing them as a whole. Therefore, we were incapable of ruling out the potential confounding effects brought about by esophageal adenocarcinoma in analyzing the prognosis as well as clinicopathological meaning of the SLC1A5 mRNA level in ESCA.

Finally, our findings in this report were subject to two limitations that need to be acknowledged. The main shortcoming from which this study suffered is that we did not control for the number of tumor cells in the use of multiplexed immunofluorescent staining by using a specific biomarker to label ESCC cells, for instance, cytokeratin 4 [35], which was used for the identification of tumor cells from epithelial cells. It would be less likely to standardize the number of tumor cells in both the epithelial and stromal compartments of ESCC without controlling the number of ESCC cells by cytokeratin 4 staining. Another underlying source of uncertainty lies in the multiplexed immunofluorescent staining used to calculate the expression of SLC1A5 and CD8a in the ESCC tissue microarray. Technically, multiplexing technology is a powerful tool; however, note should be taken when performing the experiment to avoid artificial staining and false positive signals [36] due to species cross-reaction between antibodies. Given these findings, more research is required before the association between SLC1A5 expression and the exclusion of CD8+ T cells is more clearly understood in the context of SCC.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting that SLC1A5 expression was unrelated to prognosis but associated with the exclusion of CD8+ T cells in the setting of SCC. In addition, SLC1A5 expression was associated with clinical stage in ESCC.

5. Ethics statements

The studies were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. The patients/participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Shutao Zheng: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Tao Liu; Qing Liu: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Conggai Huang; Yan Liang; Yiyi Tan: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Xiaomei Lu; Li Zhang: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Funding statement

The study was partly supported by the special funds for the development of local science and technology from the central government (ZYYD2022B06), and partly grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Autonomous Region (2022D01E26), Key Research and Development Project of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2020B03003, 2020B03003-1) and Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC.81960552),and Leading talent project of scientific and technological innovation in Tianshan talents training plan of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2022TSYCLJ0031).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14571.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

Overview of the ESCC tissue microarray we employed that underwent multiplexed immunofluorescent staining. The dot numbered 1E corresponds to Fig. 2A; dot 2E corresponds to Fig. 2C; correspondingly, dot 1G corresponds to Fig. 2B, and dot 2G corresponds to Fig. 2D.

Shown are the emission spectra of two marker-fluorophore pairs and the tissue autofluorescence signal used for spectral unmixing. Spectral signatures were captured from single-stained controls using multispectral imaging at every 10 nm wavelength across all filter cubes (DAPI, FITC, Cy3, Texas Red, and Opal 690). The unmixed units were a function of the dynamic range of the camera. The curves were then normalized to the maximum intensity for each fluorophore (0.6) so they could be presented within the same graph.

Prognostic significance of SLC1A5 mRNA level, as analyzed by TIMER 2.0 version database (http://timer.cistrome.org/), in ESCA (n=183), HNSCC (n=514) and LUSC (n=498).

Similarly, the prognostic value of the SLC1A5 mRNA level was analyzed by the TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/) in ESCA, HNSC and LUSC.

The correlation between SLC1A5 mRNA level and tumor grade, as analyzed by the TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/), in HNSC is shown.

References

- 1.Scalise M., Console L., Cosco J., Pochini L., Galluccio M., Indiveri C. ASCT1 and ASCT2: brother and sister? SLAS Discov. 2021;26:1148–1163. doi: 10.1177/24725552211030288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y., Zhao T., Li Z., Wang L., Yuan S., Sun L. The role of ASCT2 in cancer: a review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018;837:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teixeira E., Silva C., Martel F. The role of the glutamine transporter ASCT2 in antineoplastic therapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2021;87:447–464. doi: 10.1007/s00280-020-04218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garibsingh R.A., Ndaru E., Garaeva A.A., Shi Y., Zielewicz L., Zakrepine P., et al. Rational design of ASCT2 inhibitors using an integrated experimental-computational approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104093118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z., Liu R., Shuai Y., Huang Y., Jin R., Wang X., et al. ASCT2 (SLC1A5)-dependent glutamine uptake is involved in the progression of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2020;122:82–93. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0637-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagaev A., Kotlov N., Nomie K., Svekolkin V., Gafurov A., Isaeva O., et al. Conserved pan-cancer microenvironment subtypes predict response to immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:845–865 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackenzie N.J., Nicholls C., Templeton A.R., Perera M.P., Jeffery P.L., Zimmermann K., et al. Modelling the tumor immune microenvironment for precision immunotherapy. Clin Transl Immunol. 2022;11 doi: 10.1002/cti2.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borsetto D., Tomasoni M., Payne K., Polesel J., Deganello A., Bossi P., et al. Prognostic significance of CD4+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/cancers13040781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P., Chen Y., Long Q., Li Q., Tian J., Liu T., et al. Increased coexpression of PD-L1 and TIM3/TIGIT is associated with poor overall survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021;9 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigo J.P., Sanchez-Canteli M., Lopez F., Wolf G.T., Hernandez-Prera J.C., Williams M.D., et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9050486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hao J., Li M., Zhang T., Yu H., Liu Y., Xue Y., et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes differs depending on lymphocyte subsets in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:614. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X., Xiang Y., Li F., Yin C., Li B., Ke X. WNT/beta-Catenin signaling pathway regulating T cell-inflammation in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2293. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luke J.J., Bao R., Sweis R.F., Spranger S., Gajewski T.F. WNT/beta-catenin pathway activation correlates with immune exclusion across human cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:3074–3083. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vougiouklakis T., Bao R., Nakamura Y., Saloura V. Protein methyltransferases and demethylases dictate CD8+ T-cell exclusion in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oncotarget. 2017;8:112797–112808. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansari R.E., Craze M.L., Althobiti M., Alfarsi L., Ellis I.O., Rakha E.A., et al. Enhanced glutamine uptake influences composition of immune cell infiltrates in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2020;122:94–101. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0626-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao J., Yang Z., Tu M., Meng W., Gao H., Li M.D., et al. Correlation between prognostic biomarker SLC1A5 and immune infiltrates in various types of cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.608641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomczak K., Czerwinska P., Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp. Oncol.(Pozn) 2015;19:A68–A77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z., Jensen M.A., Zenklusen J.C. A practical guide to the cancer genome Atlas (TCGA) Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1418:111–141. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett T., Edgar R. Mining microarray data at NCBI’s gene expression Omnibus (GEO) Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;338:175–190. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-097-9:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chicco D. geneExpressionFromGEO: An R package to facilitate data reading from gene expression Omnibus (GEO) Methods Mol. Biol. 2022;2401:187–194. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1839-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Z., Li C., Kang B., Gao G., Li C., Zhang Z. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C., Tang Z., Zhang W., Ye Z., Liu F. GEPIA2021: integrating multiple deconvolution-based analysis into GEPIA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W242–W246. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ru B., Wong C.N., Tong Y., Zhong J.Y., Zhong S.S.W., Wu W.C., et al. TISIDB: an integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4200–4202. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li T., Fan J., Wang B., Traugh N., Chen Q., Liu J.S., et al. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice T.W., Ishwaran H., Kelsen D.P., Hofstetter W.L., Apperson-Hansen C., Blackstone E.H., et al. Recommendations for neoadjuvant pathologic staging (ypTNM) of cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction for the 8th edition AJCC/UICC staging manuals. Dis. Esophagus. 2016;29:906–912. doi: 10.1111/dote.12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francisco-Cruz A., Parra E.R., Tetzlaff M.T., Wistuba I.I. Multiplex immunofluorescence assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2055:467–495. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9773-2_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahi K., Holst J. ASCT2: a potential cancer drug target. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2019;23:555–558. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2019.1627328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toyoda M., Kaira K., Ohshima Y., Ishioka N.S., Shino M., Sakakura K., et al. Prognostic significance of amino-acid transporter expression (LAT1, ASCT2, and xCT) in surgically resected tongue cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;110:2506–2513. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikkuni O., Kaira K., Toyoda M., Shino M., Sakakura K., Takahashi K., et al. Expression of amino acid transporters (LAT1 and ASCT2) in patients with stage III/IV laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2015;21:1175–1181. doi: 10.1007/s12253-015-9954-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honjo H., Kaira K., Miyazaki T., Yokobori T., Kanai Y., Nagamori S., et al. Clinicopathological significance of LAT1 and ASCT2 in patients with surgically resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016;113:381–389. doi: 10.1002/jso.24160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo Y., Li W., Ling Z., Hu Q., Fan Z., Cheng B., et al. ASCT2 overexpression is associated with poor survival of OSCC patients and ASCT2 knockdown inhibited growth of glutamine-addicted OSCC cells. Cancer Med. 2020;9:3489–3499. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leone R.D., Zhao L., Englert J.M., Sun I.M., Oh M.H., Sun I.H., et al. Glutamine blockade induces divergent metabolic programs to overcome tumor immune evasion. Science. 2019;366:1013–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.aav2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin M.D., Badovinac V.P. Defining memory CD8 T cell. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2692. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo H., Xu Y., Wang F., Shen Z., Tuo X., Qian H., et al. Clinical associations between ASCT2 and pmTOR in the pathogenesis and prognosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2018;40:3725–3733. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takikita M., Hu N., Shou J.Z., Giffen C., Wang Q.H., Wang C., et al. Fascin and CK4 as biomarkers for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:945–952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D., Pang Z., Clarke G.M., Nofech-Mozes S., Liu K., Cheung A.M., et al. Ki-67 membranous staining: biologically relevant or an artifact of multiplexed immunofluorescent staining. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2016;24:447–452. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Overview of the ESCC tissue microarray we employed that underwent multiplexed immunofluorescent staining. The dot numbered 1E corresponds to Fig. 2A; dot 2E corresponds to Fig. 2C; correspondingly, dot 1G corresponds to Fig. 2B, and dot 2G corresponds to Fig. 2D.

Shown are the emission spectra of two marker-fluorophore pairs and the tissue autofluorescence signal used for spectral unmixing. Spectral signatures were captured from single-stained controls using multispectral imaging at every 10 nm wavelength across all filter cubes (DAPI, FITC, Cy3, Texas Red, and Opal 690). The unmixed units were a function of the dynamic range of the camera. The curves were then normalized to the maximum intensity for each fluorophore (0.6) so they could be presented within the same graph.

Prognostic significance of SLC1A5 mRNA level, as analyzed by TIMER 2.0 version database (http://timer.cistrome.org/), in ESCA (n=183), HNSCC (n=514) and LUSC (n=498).

Similarly, the prognostic value of the SLC1A5 mRNA level was analyzed by the TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/) in ESCA, HNSC and LUSC.

The correlation between SLC1A5 mRNA level and tumor grade, as analyzed by the TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/), in HNSC is shown.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.