Abstract

Background:

Severe injury and associated hemorrhagic shock lead to an inflammatory response and subsequent increased tissue damage. Numerous reports have shown that injury-induced inflammation and the associated end-organ damage is driven by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation via damage-associated molecular patterns. We examined the effectiveness of Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564), an inhibitor of TLR4 function, in reducing inflammation induced during hemorrhagic shock with resuscitation (HS/R) or after peripheral tissue injury (bilateral femur fracture, BFF).

Material and methods:

Mice underwent HS/R or BFF with or without injection of Eritoran (5 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle control given before, both before and after, or only after HS/R or BFF. Mice were sacrificed after 6 h and plasma and tissue cytokines, liver damage (histology; aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase), and inflammation (NF-κB) and gut permeability were assessed.

Results:

In HS/R Eritoran significantly reduced liver damage (values ± SEM: alanine aminotransferase 9910 ± 3680 U/L versus 1239 ± 327 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase 5863 ± 2000 U/L versus 1246 ± 243 U/L, P < 0.01) at 6 h compared with control when given just before HS and again just prior to resuscitation. Eritoran administration also led to lower IL-6 levels in plasma and liver and less NF-κB activation in liver. Increases in gut barrier permeability induced by HS/R were also prevented with Eritoran. Eritoran similarly diminished BFF-mediated systemic inflammatory responses.

Conclusion:

These data suggest Eritoran can inhibit tissue damage and inflammation induced via TLR4/myeloid differentiation factor 2 signaling from damage-associated molecular patterns released during HS/R or BFF. Eritoran may represent a promising therapeutic for trauma patients to prevent multiple organ failure.

Keywords: Organ damage, Tight junctions, DAMPs, Mice, Toll-like receptor, Liver

1. Introduction

According to data published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, unintentional injuries were the leading cause of death in people aged between 1 and 44 y [1]. The inflammatory response resulting from tissue damage and associated hemorrhagic shock and reperfusion injury (HS/R) plays an important role in the fate of injured patients. Work by our laboratory and others has shown that both HS/R and trauma (e.g., bilateral femur fracture [BFF]) activate the immune system through pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLR) [2]. This activation of the immune system is seen as a robust systemic inflammatory response, which can result in subsequent organ damage [3]. Our previous findings [2–5] and the work of others [6–9] indicate that TLR4 plays a central role in HS/R and trauma-induced organ injury and inflammation, as TLR4-deficient mice show reduced inflammation and tissue damage in these settings compared with controls [2,5].

The best-understood mechanism for TLR4 activation is by the pathogen-associated molecular pattern, lipopolysaccharide (LPS; endotoxin), which is found on the outer wall of gram-negative bacteria. LPS binds to the TLR4 signaling complex through direct interaction of its conserved lipid A moieties with the TLR4 accessory protein, myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD2) [10]. Lipid A interacts with this complex via acyl chains attached to its diglucosamine backbone [11]. Subsequent activation of this complex leads to dimerization of MD2/TLR4 complexes and activation of downstream intracellular signaling mediators, such as myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88, TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β, and TRIF-related adaptor molecule 2, leading to production of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines [12]. This leads to inflammatory responses characteristic of sepsis.

However, in the setting of sterile injury as seen in trauma, LPS is probably not the dominant activator of TLR4. Instead there is evidence that damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP), such as high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), released by damaged or stressed cells, drive TLR4 activation [13]. Consequently, this TLR4 activation leads to increased inflammation and damage after HS/R injury or trauma [3]. However, the mechanisms of DAMP-induced TLR4 signaling are unclear and the role for MD2 has not been established.

Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564) is a synthetic molecule with a tetra-acylated lipid A structure [14] derived from the non-pathogenic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Eritoran has been shown to act in humans and mice to antagonize LPS signaling via TLR4 by binding in the lipophilic pocket of MD2, so mimicking lipid A but preventing MD2/TLR4 complex activation [15]. Eritoran is known to be a well-tolerated drug in humans [16] and is therefore a plausible candidate for treatment of TLR4/MD2-induced inflammatory damage. In a rat model of renal ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) injury, Eritoran reduced the I/R-related inflammatory response [17]. Furthermore, in a mouse myocardial I/R model Eritoran attenuated infarct size and inflammatory response [18]. In both of these models of isolated organ damage the inflammation is thought to be driven by DAMPs, suggesting that Eritoran can also block TLR4 function in the setting of sterile tissue injury.

In our present study, our aim was to investigate the effectiveness of Eritoran in reducing inflammation and organ dysfunction induced in two independent systemic models of injury: HS/R and BFF. We show here that Eritoran was able to prevent liver injury, as well as reduce gut barrier dysfunction in HS/R. Eritoran treatment also suppressed the early inflammatory response in both models. Thus Eritoran is an effective candidate for reducing organ damage not only in local ischemia models but also in models that lead to a robust systemic inflammatory response, such as trauma or hemorrhagic shock. This suggests that Eritoran may serve as a potential therapy in trauma and hemorrhagic shock, and further confirms the importance of TLR4/MD2 signaling in hemorrhagic shock–induced inflammation and organ injury. Our findings in this study also shed light on the importance of the timing of Eritoran treatments, with the observable effects resulting in reduction of systemic inflammation relating to the half-life of the drug.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal care

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. Experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with all regulations regarding the care and use of experimental animals as published by the National Institutes of Health. Male C57BL/6 (WT) mice (Charles River Laboratories International, Wilmington, MA), aged 8–12 wk and weighing 20–30 g, were used in experiments. Animals were allowed access to rodent chow and water ad libitum.

2.2. Experimental groups

2.2.1. Hemorrhagic shock

Mice were assigned to the following main groups: (1) uninjured control (no injection or manipulation, n = 6); (2) injection control (injection of vehicle or Eritoran, n = 6/group [gp]); and (3) HS/R (2 h hemorrhagic shock + 4 h fluid resuscitation, n = 6–8/gp). The HS/R and injection control groups were further divided into three subgroups: Group A, Eritoran or vehicle 30 min before HS; Group B, Eritoran or vehicle 30 min before HS and immediately prior to resuscitation; Group C, Eritoran or vehicle immediately prior to resuscitation only. In all cases and all time points Eritoran or vehicle was given intravenously (i.v.) at a dose of 5 mg/kg body weight (BW) and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to 150 μL total volume. HS/R group mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg; Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Deerfield, IL) and inhaled isoflurane (Abbott Labs, Chicago, IL).

The procedure was carried out as previously described [2,19]. Briefly, after bilateral groin dissections, both femoral arteries were cannulated using polyethylene tubing flushed with 2 U heparin per animal (Pharmacia & Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI). Baseline mean arterial pressure was determined with one catheter connected to a blood pressure transducer (Micro-Med, Tustin, CA). Then, using the second catheter, hemorrhage was induced to a mean arterial pressure of 25 mm Hg for 2 h followed by fluid resuscitation with Ringer’s solution (three times the volume of shed blood) through this catheter. Successful resuscitation was defined by the restoration of normal blood pressure. After resuscitation, catheters were removed, vessels were ligated, and the wounds were closed. Body temperature was measured with a rectal probe and constantly kept at 37°C ± 0.5°C throughout the experiment using heating lamps. Injection control group mice underwent anesthesia without cannulation or HS/R. Uninjured control mice were sacrificed without any procedures performed in order to obtain physiological baseline levels. All animals were sacrificed after a total time course of 6 h.

2.2.2. Endotoxemia

Additional experiments also involved groups of mice that underwent BFF or endotoxemic shock. Endotoxemic shock was induced by giving mice intraperitoneal LPS [#L3012; Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO] at a dose of 3 mg/kg BW in 150 μL PBS. These mice were also given either vehicle or Eritoran (5 mg/kg BW) 30 min prior to LPS injection (n = 3/gp). Animals were sacrificed after 6 h.

2.2.3. Bilateral femur fracture

Mice subjected to BFF and soft tissue injury were anesthetized with intraperitoneal sodium pentobarbital for the whole experiment (6 h) as previously described [2]. Briefly, soft tissue damage was induced in this model by clamping both thigh muscles with a large hemostat for 30 s. Mice also were given BFF, performed manually with the aid of hemostats. For BFF experiments, Eritoran (5 mg/kg BW) or vehicle was given at the time of BFF and again after 3 h. Mice were sacrificed after 6 h, having been under anesthesia the whole time.

2.3. Blood and tissue collection and plasma analysis

Anesthetized mice as described above were euthanized by opening the chest cavity and performing cardiac puncture with blood withdrawal. The collected heparinized blood samples were centrifuged at 1200g for 10 min, supernatant was centrifuged again at 1200g for 5 min, and plasma was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. One aliquot was used unfrozen for quantification of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and creatine kinase (CK) levels (Dry-Chem Veterinary Chemistry Analyzer; HESKA, Loveland, CO; slides from Fujifilm Corporation, Asaka-shi Saitama, Japan). Stored aliquots were used to determine plasma cytokine levels by Luminex multiplexing bead array platform (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and results were confirmed by ELISA for interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor α (R&D, Minneapolis, MN). Samples from each mouse were analyzed.

Immediately after cardiac puncture the left liver lobe, left lung, left kidney, and one third of the terminal ileum were harvested and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C. Blood was flushed from the entire animal using PBS by cardiac puncture [19], followed by perfusion with 2% paraformaldehyde before collecting the right liver, right lung, right kidney, and two thirds of the terminal ileum for hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining and immunofluorescence (IF). Each tissue sample was divided equally for H&E and IF staining.

2.4. Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Harvested tissues were further fixed for 2 h with 2% paraformaldehyde, followed by rehydration of tissues in 30% sucrose for 24 h. The samples were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen–cooled 2-methylbutane and stored at −80°C until ready for sectioning. Cryopreserved tissues were sectioned to 5-μm thickness and were incubated with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h, followed by five washes with PBS + 0.5% bovine serum albumin (PBB). Apoptotic cells in liver, lung, and gut sections were identified using terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining following manufacturer’s protocol (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Additional primary antibodies used were: rabbit-cleaved caspase 3 (1:100; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); rat-Ly-6G (1:100; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); hamster-CD11c (1:100; BD Pharmingen); rabbit-ZO-1 (1:50; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by incubation in the appropriate Alexa Fluor phalloidin (1:250; Invitrogen) and Cy3-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1000; Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Samples were washed three times with PBS + 0.5% bovine serum albumin, followed by a single wash with PBS prior to 30 s incubation with Hoeschst nuclear stain. Nuclear stain was removed and samples were washed with PBS prior to being coverslipped using Gelvatol (23 g polyvinyl alcohol 2000, 50mL glycerol, 0.1% sodium azide to 100 mL PBS). Positively stained cells in five random fields were imaged on a Fluoview 1000 confocal scanning microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY). Imaging conditions were maintained at identical settings with original gating performed within each antibody-labeling experiment with the negative control (no primary antibody).

2.5. H&E staining and bright-field microscopy

Tissues harvested for histologic analysis were fixed for an additional 18 h in 2% paraformaldehyde followed by 70% ethanol. Fixed sections were processed and embedded in paraffin wax, and sections were cut (5 μm) and stained with H&E. Images of histologic sections were obtained in a blinded manner.

2.6. NF-κB p65 and JNK/pJNK

Nuclear extractions from whole frozen liver tissues using the nuclear extraction kit (TransAm, Rixensart, Belgium) were performed for each mouse. Subsequently, TransAm NF-κB kit (TransAm) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to measure activated p65 in liver tissues. This kit is a DNA-binding ELISA assay to measure binding capacity of the above-mentioned transcription factors by specific double-stranded oligonucleotide sequences fixed on the bottom of a 96-well plate. Activated transcription factors are able to bind to the sequences and could be detected using antibodies against the activated transcription factor. JNK and pJNK levels were measured in whole tissue lysate using Star-Elisa JNK and pJNK Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s manual.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance (with post hoc testing according to Student-Newman-Keuls method) and Student t-test procedures using Sigmaplot 11 software(Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM), with differences being accepted as statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Eritoran attenuates responses to LPS in vivo and in vitro

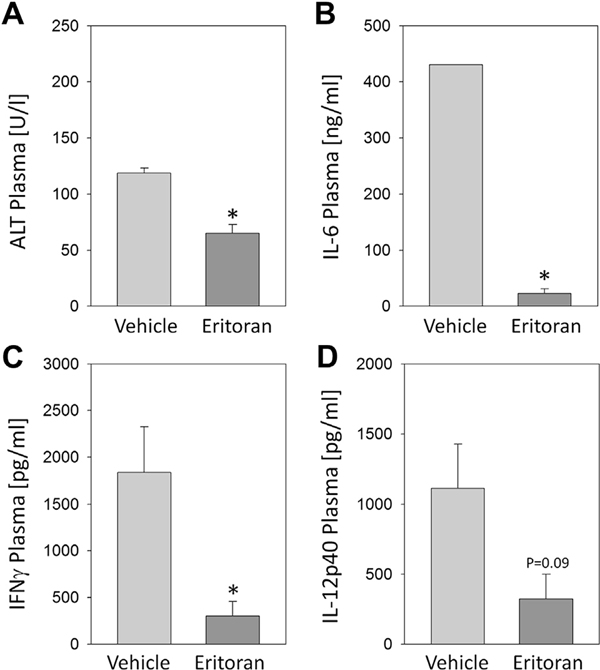

Eritoran is a structural analogue of the lipid A portion of LPS, which binds to MD2 and so antagonizes LPS-mediated TLR4 signaling. To establish the dose and effectiveness of Eritoran pretreatment in vivo, we administered i.v. Eritoran (5 mg/kg BW in 150 μL total volume) or 150 μL of solute without Eritoran (vehicle) to mice 30 min before intraperitoneal injection with 3 mg/kg BW LPS. The Eritoran-treated mice had significantly lower levels of IL-6, interferon γ, and plasma ALT, as well as a trend for reduced levels of IL-12p40 cytokine (Fig. 1A–D) after 6 h. These findings are consistent with published data from Kawa et al. [20] and the known effect of Eritoran to reduce inflammatory cytokines and end-organ damage in response to LPS stimulation and confirm the effectiveness of Eritoran to block TLR4 signaling in vivo using 5 mg/kg BW.

Fig. 1 –

C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with Eritoran or vehicle followed by intraperitoneal LPS (5 mg/kg BW). After 6h, plasma (A) ALT, (B) IL-6, (C) IFNγ, and (D) IL-12 levels were measured. n = 3–4 per experimental group, *P< 0.05. Data represent mean ± SEM. IFNγ = interferon γ.

3.2. Eritoran modulates systemic inflammation after HS/R or trauma

To determine whether Eritoran would block inflammation-associated signaling in our models of sterile injury, we used our well-established mouse models of HS/R and BFF [21]. For investigation using HS/R, C57BL/6 mice were divided into three experimental Eritoran-treated groups, each with their own vehicle controls. These groups were designed to enable investigation of the optimal timing of Eritoran treatments. Groups received the following treatment: Group A, single treatment (150 μL volume) 5 mg/kg BW Eritoran or vehicle i.v. 30 min prior to HS/R; Group B, two treatments (150 μL volume each treatment) 5 mg/kg BW Eritoran or vehicle i.v. (first treatments 30 min prior to HS/R; second treatment immediately prior to resuscitation); Group C, single treatment (150 μL volume) 5 mg/kg BW Eritoran i.v. immediately prior to resuscitation.

At 6 h after the start of hemorrhagic shock, plasma and tissue samples were collected for analysis. There were no significant differences in the volume of blood required to be removed from each mouse to achieve a mean arterial pressure of 25–30 mm Hg, or in mean arterial pressures before and after reperfusion between any of the experimental and control groups (data not shown).

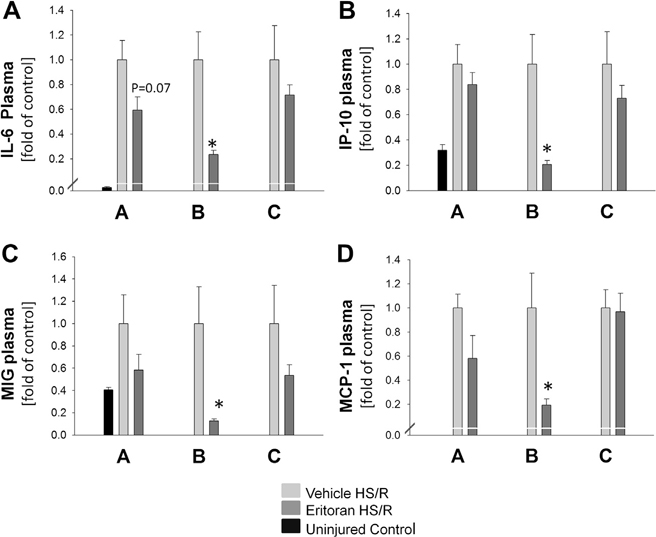

Plasma level of IL-6 was used as a marker of systemic inflammation, and was significantly reduced in Eritoran Group B mice compared with their vehicle controls (394 ± 59 pg/mL versus 1676 ± 415 pg/mL; P < 0.01). Eritoran Group A (P = 0.07) and Eritoran Group C (P = 0.4) mice also trended towards decreased levels of IL-6, although this did not reach significance (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, plasma levels of chemokines, including IP-10 (Fig. 2B), MIG (Fig. 2C), and MCP-1 (Fig. 2D), showed similar results, with significantly reduced chemokine levels in Eritoran Group B mice compared with vehicle-treated HR/S Control Group B and a trend towards lower chemokine levels in Eritoran Groups A and C compared with their corresponding vehicle groups, although this failed to reach significance. For clarity, results shown in Figure 2 depict cytokine/chemokine levels for each group normalized to their own vehicle controls. Significance was calculated, however, using the raw data from each group without this transformation.

Fig. 2 –

C57BL/6 mice were treated with Eritoran or vehicle as follows: Group A, immediately before HS/R; Group B, immediately before AND just prior to resuscitation; Group C, just prior to resuscitation. Uninjured control results are shown. Plasma (A) IL-6, (B) IP-10, (C) MIG, and (D) MCP-1 at 6 h is shown. Data are depicted as values normalized to their own group vehicle controls and shown as fold changes. n = 6–8 per experimental group, *P < 0.05. Data represent mean ± SEM. P = 0.07, Group A IL-6 versus control.

We also determined plasma levels of CK as an estimate of muscle and tissue damage. CK levels were significantly reduced in Eritoran Group B mice compared with vehicle controls (13,968 ± 1064 U/L versus 18,733 ± 1563 U/L; P < 0.05). Similarly to cytokine and chemokine levels, levels of CK in Eritoran Groups A and C were attenuated, but not to a level of statistical significance. CK levels were comparable between Eritoran and vehicle groups at baseline, without HS/R injury (Eritoran Control Group B 807 ± 243 U/L and vehicle Control Group B 723 ± 124 U/L).

To assess the effect of Eritoran in tissue trauma without HS/R, we utilized a model of BFF in anesthetized mice [2,19]. Mice were given Eritoran immediately after BFF, and additionally at the 3 h time point. Similarly to HS/R, Eritoran-treated mice had significantly reduced plasma IL-6 levels at 6 h after injury compared with vehicle controls (177 ± 23 pg/mL versus 389 ± 118 pg/mL; P < 0.05), indicating reduced levels of inflammation. There were no differences in ALT levels after BFF between Eritoran and vehicle treatments (data not shown). However, ALT levels are only modestly increased in this model [2,19].

3.3. Liver inflammation and gut permeability after HS/R are attenuated by Eritoran treatment

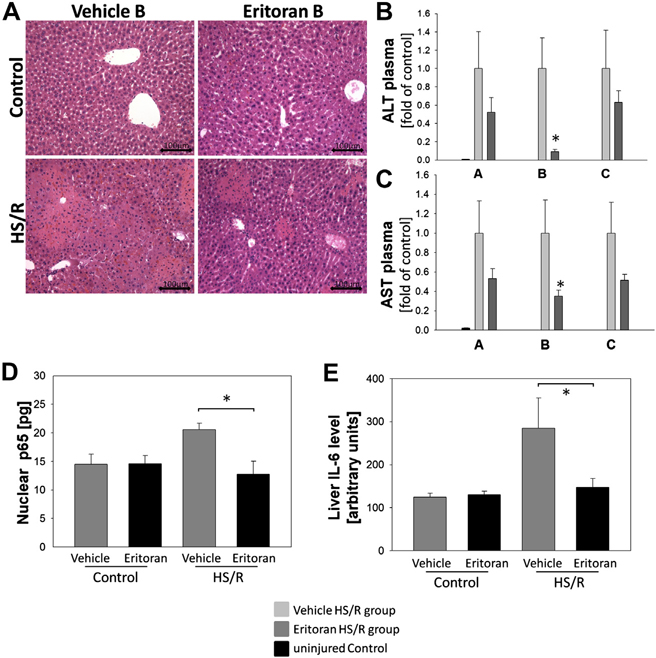

As we had shown significantly reduced inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels in mice treated with Eritoran both before and after HS/R (Group B), we next wanted to determine whether this reduction in systemic inflammatory markers was also reflected in a reduction in end-organ damage. We stained liver tissue sections from vehicle-treated and Eritoran-treated Group B mice with H&E to assess liver damage histologically (Fig. 3A). We observed reduced liver tissue damage in liver from Eritoran Group B mice, with fewer and smaller areas of necrosis compared with vehicle controls (Fig. 3A). Additionally, plasma ALT and AST levels, used as parameters for liver damage, were significantly reduced in Eritoran Group B mice compared with vehicle controls (Fig. 3B and C).

Fig. 3 –

(A) H&E staining of liver tissue from Group B mice. (B) Plasma ALT and (C) AST in Eritoran- or vehicle-treated mice or controls at 6 h after HS/R. (D) Liver nuclear NF-κB p65 levels in Group B mice or controls at 6 h after HS/R. (E) Liver tissue IL-6 levels in Group B Eritoran- or vehicle-treated mice or controls. n = 6–8 per experimental group, *P < 0.05. Data represent mean ± SEM, scale bar 100 μm.

We next wanted to determine whether inflammatory signaling downstream of TLR4 was also attenuated in the liver with Eritoran treatment. To do this we looked at activation (nuclear localization) of the transcription factor NF-κB, and its p65 subunit, in liver tissue homogenates [22]. We found that activation of NF-κB subunit p65 was significantly reduced in livers of Eritoran Group B mice compared with vehicle controls (Fig. 3D). Correspondingly, levels of IL-6, a cytokine dependent on activation of NF-κB, in whole-cell lysates of liver tissue from Eritoran Group B mice were also reduced compared with vehicle-treated mice after HS/R (Fig. 3E). Additionally, Eritoran reduced levels of activated (phosphorylated) JNK, known to be activated by TLR4 signaling, in whole-tissue lysates of liver tissue of mice subjected to hemorrhagic shock by 7% compared with vehicle-treated mice (data not shown, P = 0.14).

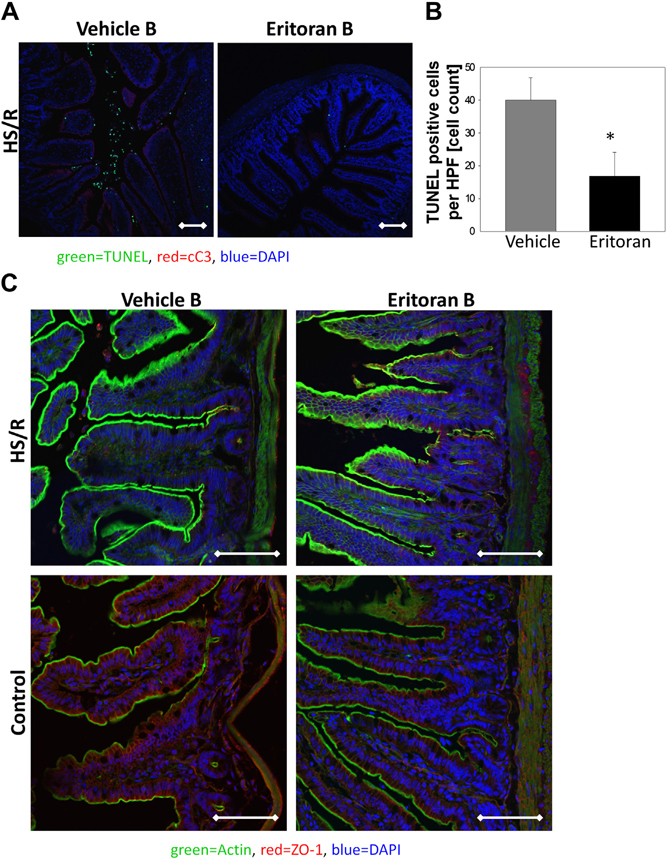

The intestinal mucosa is subject to injury and dysfunction in HS/R [23]; therefore, we assessed whether Eritoran reduced inflammation and cell death in the gut after HS/R. Apoptosis was assessed by TUNEL immunofluorescence in the ileum of Eritoran Group B mice compared with vehicle controls. Eritoran Group B mice had significantly fewer TUNEL-positive cells in the ileum compared with the vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 4A and B). The loss of ZO-1, a marker of tight junctions in epithelia, correlates with a loss of gut barrier function [24]. We stained for ZO-1 immunofluorescence in gut tissue sections of Eritoran Group B mice and their vehicle controls. We observed higher levels of ZO-1 immunofluorescence in the gut of Eritoran Group B mice compared with vehicle-treated mice after HS/R (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the gut barrier is also more preserved in HS/R after Eritoran treatment.

Fig. 4 –

(A) Immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase 3 (cC3; red), DAPI (nucleus; blue), and TUNEL (green) in paraformaldehyde-fixed terminal ileum from Group B Eritoran- and vehicle-treated mice. (B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive immunofluorescent cells in five power fields. (C) Immunofluorescence of Zonula occludens (ZO)-1 (red), DAPI (blue), and actin (green) in paraformaldehyde-fixed terminal ileum from Group B Eritoran- and vehicle-treated mice. Representative images are shown. n = 6–8 per experimental group, *P < 0.05. Data represent mean ± SEM, scale bar 100 μm.

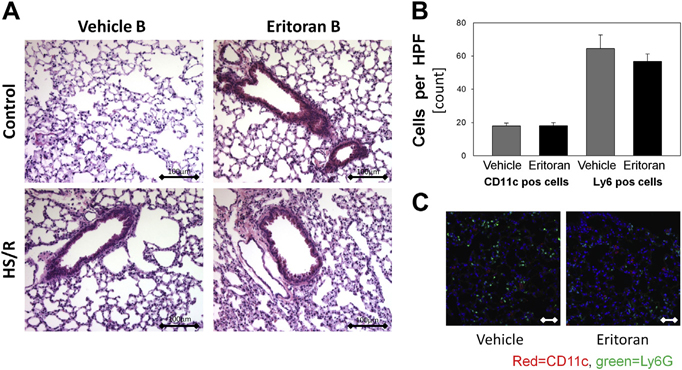

3.4. Eritoran does not reduce lung inflammation or damage after HS/R

The lung is also subject to inflammation and dysfunction even in short-term models of HS/R [9]. We assessed lung histology and found no differences in lung congestion, edema, or hemorrhage when comparing Eritoran Group B and vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 5A). We further assessed immune cell infiltration in the lung by immunofluorescence using Gr1/Ly-6G as a neutrophil marker and CD11c as a dendritic cell marker. We found no differences in immune cell infiltration between lungs of Eritoran Group B mice and vehicle-treated mice after HS/R (Fig. 5B and C). However, JNK phosphorylation was significantly reduced in the lung in the Eritoran-treated group (Supplementary Fig.).

Fig. 5 –

(A) H&E staining of paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung sections from Group B Eritoran- and vehicle-treated mice. (B,C) Immunofluorescence and quantification for CD11c-positive dendritic cells (red) or Ly6G-positive neutrophils (green) in lung tissue from Group B Eritoran- and vehicle-treated mice. Representative images are shown. n = 6–8 per experimental group, *P < 0.05. Data represent mean ± SEM, scale bar 100 μm.

4. Discussion

There is now ample evidence that inflammation and early organ damage induced by hemorrhagic shock is TLR4-dependent in rodents [3,5,6,19,25]. The study reported here was undertaken to determine whether a well-characterized inhibitor of the TLR4/MD2 complex protected mice in a model of hemorrhagic shock with resuscitation. We show here that Eritoran suppresses hemorrhagic shocke–induced inflammation, as well as liver and gut damage, when administered twice during the experiment: first as a pretreatment and second just prior to resuscitation. Herewith we underline the important role of TLR4 in the initiation and early propagation of immune activation in hemorrhagic shock and, furthermore, the importance of TLR4 activation in the resuscitation phase after hemorrhagic shock in the context of reperfusion injuries. Based on the known mechanism of action of Eritoran as an inhibitor of binding to the hydrophobic LPS binding pocket of MD2, these studies also suggest a role for MD2 in the activation of TLR4-dependent signaling following trauma.

The role of TLR4 and MD2 in sepsis and infection is well characterized. However, studies have also shown a role for TLR4 acting as a DAMP receptor in sterile inflammation such as I/R, HS/R, or trauma [26]. DAMPs are endogenous molecules found in the extracellular matrix, released by dying cells or actively secreted from cells, and they function as danger signals. Activation of the TLR signaling by DAMPs has been shown to play a vital role in the pathogenesis of tissue damage, but the mechanism of TLR4 activation by DAMPs is not fully understood. In this context, our data suggest an important role for the TLR4/MD2 complex in activation of the TLR4 complex by DAMPs. Consequently, blocking DAMP signaling through TLR4 with a drug such as Eritoran might be beneficial during sterile injury, and may prevent a cascade of TLR4 activation, tissue damage, and further DAMP release. In particular, liver damage that follows HS/R is mainly TLR4-dependent [3,6].

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a well-characterized DAMP that is secreted by liver tissue after liver I/R and leads to inflammatory tissue damage. It is known that HMGB1–TLR4 interactions also mediate tissue injury after HS/R [27]. HMGB1 is released readily from necrotic or damaged cells, and may then signal the presence of this tissue injury through TLR4, thus initiating an inflammatory cycle that causes further damage to viable cells. Additionally, it is well known that oxidative stress leads to tissue damage [28], and reactive oxygen species are generated by cells during HS/R [9]. Reactive oxygen species may have direct toxic effects on cells, as well as a role in upregulation of TLR4 [9]. Tsung et al. showed that hypoxia-induced HMGB1 release by hepatocytes is dependent on both reactive oxygen species and TLR4 [27]. Our findings suggest that Eritoran diminishes liver damage after HS/R, presumably by preventing DAMP-induced TLR4 signaling, such as by HMGB1.

Interestingly, Eritoran did not prevent the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lung, although we did observe decreased inflammatory signaling in the form of lower levels of phosphorylated JNK. The lack of difference in lung inflammatory cell infiltration data was initially surprising to us, but may suggest that mechanisms other than TLR4-dependent inflammatory responses may play a significant role in lung damage after HS/R. Alternatively, our findings may reflect the failure of Eritoran to adequately perfuse and affect activation of alveolar macrophages, which are known to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of tissue damage in lung tissue after HS/R [29]. These findings may suggest that optimal dosing strategies would need to be determined in order for Eritoran to have a protective effect in the lung in these conditions if given intravenously.

We confirm here that Eritoran can effectively block LPS-induced TLR4 signaling in vivo in our animal model. Eritoran, therefore, may have a dual role not only in reducing DAMP-induced organ damage, but also in reducing any LPS-TLR4-mediated inflammation resulting from LPS leak or interaction with the gut wall. However, the observation that Eritoran also protects in heart and kidney models of I/R [17,30], which are not thought to involve release of microbial molecules, supports the idea that Eritoran can also block non–pathogen-associated molecular pattern mechanisms of TLR4-MD2 activations.

Eritoran has already been used in a phase II multi-center clinical sepsis trial, where Eritoran-treated patients with a high risk of death from sepsis showed trends towards decreased mortality. Interestingly, Eritoran did not alter IL-6 cytokine release in these patients [31] even though the Eritoran dose was sufficient to block the effect of measured LPS levels [32], which suggests it has other anti-inflammatory effects apart from blocking LPS signaling. A phase III trial of Eritoran in severe sepsis has been completed, with results not yet in the literature.

Eritoran pharmacodynamics and half-life time are dose-dependent, and it is rapidly inactivated in whole blood by binding to high-density lipoproteins. This suggests the half-life of Eritoran becomes much shorter than the pharmacokinetic suggested value of 50 h. Therefore higher doses or a continuous infusion of Eritoran are recommended for optimal effect [33]. Our data with drug administration at different time points confirm this short bioactivity of Eritoran, with significant differences only in experimental groups with repeated drug application. We could find trends in decreases in tissue damage in experimental groups given single doses of Eritoran, which suggests that both early and later phases of tissue damage after HS/R are MD2-dependent. Giving Eritoran at both time points leads to a significant reduction in inflammation and tissue damage, suggesting the importance of hemorrhagic shock and reperfusion phase in development of MD2/TLR4-dependent tissue damage and inflammation. In a clinical situation it may be that Eritoran would produce the most benefit by being given as an infusion, but this would have to be tested separately in vivo. Overall, our data suggest that early treatment with high concentrations of Eritoran, or even continuous infusion, would be appropriate in clinical trials investigating its protective effects after HS/R or trauma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Alicia Frank and Derek Barclay for technical help with this work.

This work is supported through grants from the National Institutes of Health (grant: Molecular Biology of Hemorrhagic Shock, NIH # 5P50GM053789).

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.023.

REFERENCES

- [1].WISQARS. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2007. 2007. 9-3-2011.Ref Type: Online Source. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- [2].Levy RM, Prince JM, Yang R, et al. Systemic inflammation and remote organ damage following bilateral femur fracture requires Toll-like receptor 4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2006;291:R970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Prince JM, Levy RM, Yang R, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling mediates hepatic injury and systemic inflammation in hemorrhagic shock. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202:407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fan J TLR cross-talk mechanism of hemorrhagic shock-primed pulmonary neutrophil infiltration. Open Crit Care Med J 2010;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mollen KP, Levy RM, Prince JM, et al. Systemic inflammation and end organ damage following trauma involves functional TLR4 signaling in both bone marrow-derived cells and parenchymal cells. J Leukoc Biol 2008;83:80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barsness KA, Arcaroli J, Harken AH, et al. Hemorrhage-induced acute lung injury is TLR-4 dependent. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2004;287:R592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen H, Koustova E, Shults C, Sailhamer EA, Alam HB. Differential effect of resuscitation on Toll-like receptors in a model of hemorrhagic shock without a septic challenge. Resuscitation 2007;74:526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Reino DC, Pisarenko V, Palange D, et al. Trauma hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury involves a gut-lymph-induced TLR4 pathway in mice. PLoS One 2011;6:e14829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McGhan LJ, Jaroszewski DE. The role of toll-like receptor-4 in the development of multi-organ failure following traumatic haemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Injury 2012;43:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Park BS, Song DH, Kim HM, Choi BS, Lee H, Lee JO. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature 2009;458:1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].DeMarco ML, Woods RJ. From agonist to antagonist: structure and dynamics of innate immune glycoprotein MD-2 upon recognition of variably acylated bacterial endotoxins. Mol Immunol 2011;49:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Levy RM, Mollen KP, Prince JM, et al. Systemic inflammation and remote organ injury following trauma require HMGB1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;293:R1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Montminy SW, Khan N, McGrath S, et al. Virulence factors of Yersinia pestis are overcome by a strong lipopolysaccharide response. Nat Immunol 2006;7:1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mullarkey M, Rose JR, Bristol J, et al. Inhibition of endotoxin response by e5564, a novel Toll-like receptor 4-directed endotoxin antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003;304:1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bennett-Guerrero E, Grocott HP, Levy JH, et al. A phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study of Eritoran (E5564), a lipid A antagonist, in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg 2007;104:378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu M, Gu M, Xu D, Lv Q, Zhang W, Wu Y. Protective effects of Toll-like receptor 4 inhibitor eritoran on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transpl Proc 2010;42:1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shimamoto A, Chong AJ, Yada M, et al. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 4 with eritoran attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circulation 2006;114:I270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gill R, Ruan X, Menzel CJ, et al. Systemic inflammation and liver injury following hemorrhagic shock and peripheral tissue trauma involve functional TLR9 signaling on bone marrow-derived cells and parenchymal cells. Shock 2011;35:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kawa K, Tsutsui H, Uchiyama R, et al. IFN-gamma is a master regulator of endotoxin shock syndrome in mice primed with heat-killed Propionibacterium acnes. Int Immunol 2010;22:157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kobbe P, Kaczorowski DJ, Vodovotz Y, et al. Local exposure of bone components to injured soft tissue induces Toll-like receptor 4-dependent systemic inflammation with acute lung injury. Shock 2008;30:686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Korff S, Falsafi R, Czerny C, et al. Time dependency and topography of hepatic NF-kappaB activation after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in mice. Shock 2012;38:486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yang R, Gallo DJ, Baust JJ, et al. Ethyl pyruvate modulates inflammatory gene expression in mice subjected to hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002;283:G212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Luyer MD, Buurman WA, Hadfoune M, et al. Pretreatment with high-fat enteral nutrition reduces endotoxin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha and preserves gut barrier function early after hemorrhagic shock. Shock 2004;21:65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fan J, Li Y, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR, Wilson MA. Hemorrhagic shock-activated neutrophils augment TLR4 signaling-induced TLR2 upregulation in alveolar macrophages: role in hemorrhage-primed lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mollen KP, Anand RJ, Tsung A, Prince JM, Levy RM, Billiar TR. Emerging paradigm: toll-like receptor 4-sentinel for the detection of tissue damage. Shock 2006;26:430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tsung A, Klune JR, Zhang X, et al. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4 dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. J Exp Med 2007;204:2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Powers KA, Szaszi K, Khadaroo RG, et al. Oxidative stress generated by hemorrhagic shock recruits Toll-like receptor 4 to the plasma membrane in macrophages. J Exp Med 2006;203:1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fan J, Li Y, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR, Wilson MA. Neutrophil NAD(P)H oxidase is required for hemorrhagic shock-enhanced TLR2 up-regulation in alveolar macrophages in response to LPS. Shock 2007;28:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ehrentraut S, Lohner R, Schwederski M, et al. In vivo toll-like receptor 4 antagonism restores cardiac function during endotoxemia. Shock 2011;36:613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tidswell M, Tillis W, LaRosa SP, et al. Phase 2 trial of eritoran tetrasodium (E5564), a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Barochia A, Solomon S, Cui X, Natanson C, Eichacker PQ. Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564) treatment for sepsis: review of preclinical and clinical studies. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2011;7:479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wong YN, Rossignol D, Rose JR, Kao R, Carter A, Lynn M. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of E5564, a lipid A antagonist, during an ascending single-dose clinical study. J Clin Pharmacol 2003;43:735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.