Abstract

Cell cycle arrests in the G1, S, and G2 phases occur in mammalian cells after ionizing irradiation and appear to protect cells from permanent genetic damage and transformation. Though Brca1 clearly participates in cellular responses to ionizing radiation (IR), conflicting conclusions have been drawn about whether Brca1 plays a direct role in cell cycle checkpoints. Normal Nbs1 function is required for the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint, but whether Nbs1 has a definitive role in the G2/M checkpoint has not been established. Here we show that Atm and Brca1 are required for both the S-phase and G2 arrests induced by ionizing irradiation while Nbs1 is required only for the S-phase arrest. We also found that mutation of serine 1423 in Brca1, a target for phosphorylation by Atm, abolished the ability of Brca1 to mediate the G2/M checkpoint but did not affect its S-phase function. These results clarify the checkpoint roles for each of these three gene products, demonstrate that control of cell cycle arrests must now be included among the important functions of Brca1 in cellular responses to DNA damage, and suggest that Atm phosphorylation of Brca1 is required for the G2/M checkpoint.

The cellular responses to DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation (IR) include activation of cell cycle checkpoints that delay progression of cells through the cell cycle (6, 7). IR-induced checkpoints are active at the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase, in the S phase, and at the transition from the G2 phase to mitosis (G2/M). The surveillance mechanisms responsible for initiating these checkpoints appear to facilitate maintenance of the integrity of the genome, presumably because they ensure that damaged DNA templates are neither replicated nor segregated into the daughter cells until they are repaired. The option to undergo apoptosis can be considered as one of the checkpoint endpoints, and a failure of the cell to die under appropriate circumstances can lead to inappropriate survival of cells with altered genomes. Failure of these mechanisms to adequately monitor the state of DNA or to signal for repair or apoptosis after DNA has been damaged is a hallmark of most cancer cells (7).

The regulatory network of proteins involved in cell cycle checkpoints has been the focus of numerous studies, and the protein Atm plays a central role in this network in mammalian cells (16, 19). The ATM gene is mutated in the autosomal recessive disease ataxia-telangeictasia (A-T). Patients with A-T display a complex phenotype of clinical abnormalities, including progressive cerebellar ataxia, telangiectasias, predisposition to cancer, and hypersensitivity to IR (11). Cells from A-T patients show defects in cell cycle checkpoints and hypersensitivity to IR. Since Atm activity is required for optimal induction and phosphorylation of p53 protein following IR, the G1 checkpoint is affected in A-T cells (3, 9, 23). A lack of an IR-induced S-phase checkpoint results in persistent DNA synthesis at early time points after IR (radioresistant DNA synthesis [RDS]), and cells derived from patients with A-T and Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS) exhibit this abnormal phenotype (22). Atm phosphorylation of serine 343 in Nbs1, the altered protein in NBS, has recently been shown to be required for this IR-induced S-phase checkpoint (13, 27). Though additional substrates of Atm kinase have been found, including Brca1, Chk2, CtIP, and Mdm2 (5, 10, 12, 15), Atm phosphorylation of these targets has not been definitively functionally linked to the IR-induced S-phase or G2/M cell cycle checkpoints.

Accumulated data have demonstrated an important role for Brca1 in cellular responses to IR (20); however, conflicting conclusions have been drawn about whether Brca1 plays a direct role in cell cycle checkpoints. Though deletion of exon 11 from Brca1 in primary murine cells affects a G2/M checkpoint and causes mitotic abnormalities (25), normal IR-induced G2/M and S-phase checkpoints have been reported for the Brca1-defective human tumor cell line HCC1937 (21). Similarly, though normal Nbs1 function is clearly required for the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint, a definitive role for Nbs1 in the G2/M checkpoint has not been established. Results reported here demonstrate that Nbs1 is not required for the G2/M checkpoint whereas Brca1 function is required for both the IR-induced S-phase and G2/M checkpoints. Further, Atm phosphorylation of serine 1423 in Brca1 is implicated in the G2/M checkpoint signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and irradiation.

Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines from healthy persons (GM0536; NIGMS Human Mutant Cell Repository, Camden, N.J.) and from persons who were homozygous for the NBS1 mutation (NBS7078A) (4) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum. Simian virus 40-transformed human fibroblast lines from a healthy A-T heterozygote or from a patient with A-T (GM0637 or GM9607, respectively; NIGMS Human Mutant Cell Repository) and the Brca1-mutant human breast cancer cell line HCC1937 and HeLa cells (both from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were all grown as monolayers in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. AT22IJET cells, generously provided by Yossi Shiloh (Tel Aviv University), were maintained in 100 μg of hygromycin B (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) ml−1. Note that the ATM heterozygous GM0637 cells are indistinguishable from cells with two wild-type ATM alleles in the RDS assay (data not shown). All cell lines were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Radiation from a 137Cs source was delivered at a rate of approximately 120 cGy/min.

Immunofluorescent detection of phosphorylated histone H3.

Cells were harvested 1 to 1.5 h after irradiation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in suspension (concentration, 106 cells per ml) by the addition of 2 ml of 70% ethanol and by incubation at −20°C for as long as 24 h. After fixation, the cells were washed twice with PBS, suspended in 1 ml of 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS, and incubated on ice for 15 min. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was suspended in 100 μl of PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.75 μg of a polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of histone H3 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.) and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. The cells were then rinsed with PBS containing 1% BSA and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulinG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.) diluted at a ratio of 1:30 in PBS containing 1% BSA. After a 30-min incubation at room temperature in the dark, the cells were washed again, resuspended in 25 μg of propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml and 0.1 mg of RNase A (Sigma)/ml in PBS, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min before the fluorescence was measured. Cellular fluorescence was measured by using a Becton Dickinson (San Jose, Calif.) FACSCalibur flow cytometer/cell sorter.

RDS assay.

Inhibition of DNA synthesis after irradiation was assessed as previously described (13, 17). Briefly, cells in the logarithmic phase of growth were prelabeled by culturing in DMEM containing 10 nCi of [14C]thymidine (NEN Life Science Products, Inc., Boston, Mass.) for approximately 24 h; this prelabeling provides an internal control for cell number by allowing normalization for total DNA content of samples. The medium containing [14C]thymidine was then replaced with normal DMEM, and the cells were incubated for another 24 h. When cells were to be transiently transfected, they were incubated in normal DMEM for 6 h after the [14C]thymidine-containing medium was discarded. Cells were irradiated, incubated for 30 to 45 min, and then pulse-labeled with 2.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine (NEN Life Science Products)/ml for 15 min. Cells were harvested, washed twice with PBS, and fixed in 70% methanol for at least 30 min. After the cells were transferred to Whatman filters and fixed sequentially with 70% and then 95% methanol, the filters were air dried and the amount of radioactivity was assayed in a liquid scintillation counter. The resulting ratios of 3H counts per minute to 14C counts per minute, corrected for those counts per minute that were the result of channel crossover, were a measure of DNA synthesis.

Transfection of wild-type and mutated BRCA1 genes into HCC1937 cells.

Transfection of HCC1937 cells with the gene encoding hemagglutinin-tagged wild-type Brca1 (generously provided by D. Livingston, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Mass.) or mutant (alanine substitution at serine 1423) Brca1 and transfection of HeLa cells with kinase-inactive ATM (2, 13) were performed in the logarithmic phase of growth with Lipofectamine (Life Technologies). The efficiency of transfection was assessed by cotransfection with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter vector and analyzing for GFP expression by flow cytometry 36 h after transfection. The efficiency of transfection in multiple assessments was always between 90 and 97% (data not shown). For assessment of Brca1 expression in the transfectants, the cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and total cellular lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in an 8% polyacrylamide gel. Expressed transfected Brca1 proteins were detected by Western blot analysis with an antihemagglutinin monoclonal antibody (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.).

RESULTS

Brca1 participates along with Atm and Nbs1 in the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint.

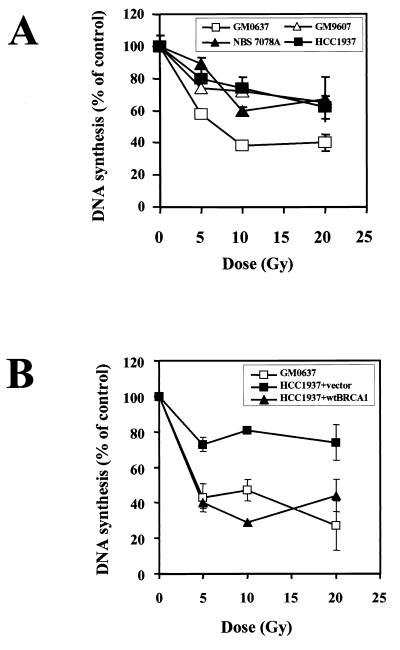

The IR-induced S-phase checkpoint in mammalian cells is thought to primarily represent an inhibition of replicon initiation and is measured as a transient decrease in [3H]thymidine incorporation at early time points (30 to 90 min) after irradiation (18). The absence of this IR-induced S-phase arrest, referred to as a RDS, has been previously reported for cells from both A-T and NBS patients (22). One study has reported a normal S-phase checkpoint in Brca1-null cells (21), but no experimental details or data were provided to support this conclusion. In our hands, the S-phase arrest after irradiation over an IR dose range from 5 to 20 Gy in the Brca1-null cell line HCC1937 was defective and was indistinguishable from cells lacking Atm or Nbs1 (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Atm, Nbs1, and Brca1 are all involved in the S-phase checkpoint activated by IR. (A) Replicative DNA synthesis was assessed 30 min after various doses of ionizing irradiation in control cells (GM0637) and cells defective in Atm (GM9607), Nbs1 (NBS7078A), or Brca1 (HCC1937) function. (B) Replicative DNA synthesis was assessed 30 min after various doses of ionizing irradiation in control cells (GM0637) and in HCC1937 cells transfected with either empty vector or wild-type BRCA1. Error bars represent the averages of at least triplicate samples. If the error bar is not visible, the standard error is smaller than the symbol.

To demonstrate that this abnormality was due to a lack of Brca1 function and not some other genetic alteration in this cell line, the HCC1937 cells were transfected with a full-length BRCA1 cDNA and the complemented cells were assessed for this checkpoint. Flow cytometric analysis of GFP expression indicated that the transfection efficiency was greater than 90%, and expression of the wild-type Brca1 was easily detected by Western blot analysis. Because transient overexpression of Brca1 can induce apoptosis, the cells were irradiated 36 h after transfection, a time point when wild-type Brca1 was expressed and the number of apoptotic cells was minimized. Brca1 transfection by itself did not affect the [3H]thymidine incorporation in nonirradiated cells. However, the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint was restored in the HCC1937 cells following complementation with Brca1 (Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that, in addition to the previously reported involvement of Atm and Nbs1, normal Brca1 function is also required for the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint.

Development of a facile assay to evaluate the G2-to-M transition after irradiation in mammalian cells by flow cytometry.

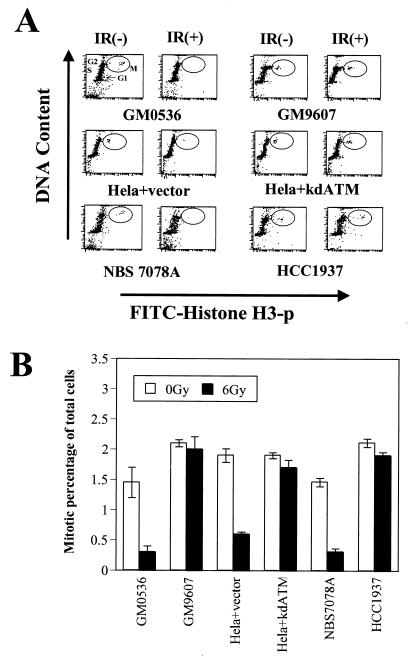

Rapid assessment of the progression of cells from G2 into mitosis is made difficult by the fact that both G2 and mitotic cells have a 4N DNA content and thus are not simply distinguishable from each other by standard PI staining and flow cytometry. Historically, the lack of the IR-induced G2 checkpoint in A-T cells has been assessed by performing mitotic spreads and counting the mitotic cells remaining in the culture at various times after IR (17, 26). Using such an assay, the number of mitotic figures is markedly diminished within 30 min after IR in cells from healthy individuals while cells from A-T patients continue to exhibit mitoses. However, this type of assay is both cumbersome to perform and difficult to quantitate accurately. These difficulties could be circumvented by having a facile way to distinguish the G2 cells from the mitotic cells in the population of cells with a 4N DNA content. Since histone H3 is phosphorylated exclusively during mitosis, an antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of histone H3 can be used to identify the mitotic cells and thus distinguish G2 cells from mitotic cells in a flow cytometric assay (8). Costaining of cells with PI to assess DNA content and an anti-phospho-histone H3 antibody demonstrates that the mitotic cells can be distinguished from G2 cells in the 4N population of cells (Fig. 2A, top row, first column). Note that we have used this assay in a variety of different mammalian cell types and the 1.5% to 3% of cells in mitosis at any given time has been very reproducible (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Within 30 to 60 min after irradiation, a significant decrease in the number of cells in mitosis was evident (Fig. 2A, top row, second column, and B). The decrease of the mitotic percentage is time dependent and dose independent (data not shown). In normal cells, the number of mitotic cells will drop 80% within an hour (Fig. 2B). These effects after IR are qualitatively the same as those seen when mitotic entry is assessed by counts of mitotic spreads (data not shown), but counts of mitotic figures in such analyses are difficult to accurately quantitate. Thus, this flow cytometric assay provides a facile and quantitative way to assess the IR-induced G2 checkpoint and the genetic determinants that control it.

FIG. 2.

Atm and Brca1, but not Nbs1, are required for the IR-induced G2 checkpoint. (A) Flow cytometric profiles of cell cycle distribution before [IR(−)] and 1 h after [IR(+)] IR using a combination of staining for DNA content (y axis) and for histone H3 phosphorylation (x axis). The 4N population of cells is distinguished as either in G2 or in mitosis (encircled, M). Control cells (GM0536 and HeLa+vector) and cells defective in Nbs1 (NBS7078A) exhibit a marked decrease in the number of mitotic cells after IR, while cells defective in Atm (GM9607 and HeLa+kdATM) or Brca1 (HCC1937) continue to enter mitosis after IR. (B) Mitotic cells as a percentage of total cells before and after IR (quantitation of data shown in panel A). The error bars represent the variability after combining the results of at least three different experiments for each cell line.

Participation of Atm and Brca1, but not Nbs1, in the IR-induced G2 checkpoint.

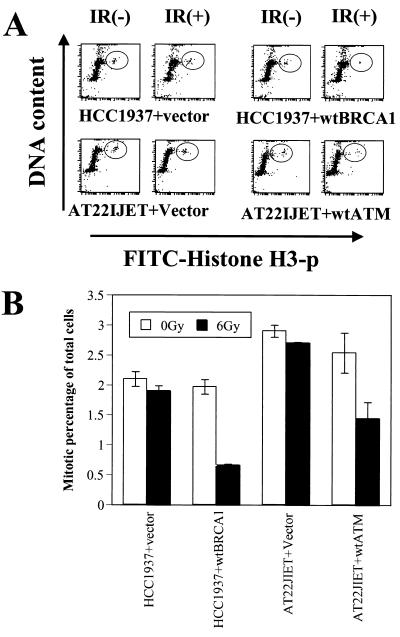

Cells from A-T patients have previously been shown to lack IR-induced G2 arrest (1, 17), and this flow cytometric assay confirmed this abnormality. While irradiation of normal cells (GM0536) resulted in an approximately 75% decrease in the number of mitotic cells, there was little to no decrease in the percentage of A-T cells (GM9607) in mitosis 60 min after irradiation (Fig. 2). This checkpoint abnormality was observed in a large number of different A-T cell lines (data not shown). Inhibition of Atm function in HeLa cells by transfection of a dominant-negative construct of ATM similarly demonstrated the loss of the G2 checkpoint (Fig. 2, HeLa+kdATM). In contrast to the cells with defective Atm function, cells from an NBS patient (NBS7078A) exhibited a normal IR-induced G2 checkpoint (Fig. 2). Thus, in contrast to its critical role in the S-phase checkpoint, Nbs1 function does not appear to be required for the G2 checkpoint. The Brca1-null cell line HCC1937 exhibited a G2/M checkpoint abnormality similar to that seen in the A-T cells (Fig. 2). In order to assess whether this abnormality in HCC1937 cells was due to their altered Brca1 function, wild-type Brca1 was reintroduced into the cells by transient transfection. Transfection of Brca1 did not affect cell cycle distribution in nonirradiated cells. However, restoration of Brca1 function restored the IR-induced G2 arrest in these cells (Fig. 3), thus demonstrating a role for Brca1 in this checkpoint pathway.

FIG. 3.

Introduction of wild-type Brca1 complements the G2/M checkpoint defect in HCC1937 cells. (A) Assessment of the G2/M checkpoint as in Fig. 2A, comparing HCC1937 cells transfected with either control vector or wild-type BRCA1. A-T cells transfected with control vector or complemented with wild-type ATM are shown for comparison. (B) Quantitation of data shown in panel A, averaged over three experiments.

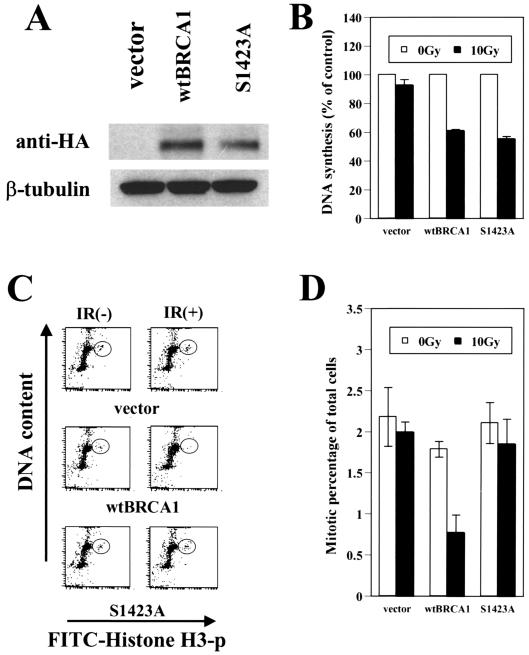

Serine 1423 of Brca1 is important for the IR-induced G2/M checkpoint but not the S-phase checkpoint.

Since similar cell cycle checkpoint defects were found in cells defective in Atm and Brca1, and since Brca1 is phosphorylated by Atm in vitro and in vivo (5, 24), we examined the impact of mutating a major Atm phosphorylation site in BRCA1 (serine 1423 to alanine). While the mutated Brca1 still rescued the S-phase checkpoint defect in HCC1937 cells (Fig. 4B), the G2/M checkpoint defect was not complemented (Fig. 4C and D). The failure to complement the G2/M checkpoint is not attributable to a lack of expression of the mutant Brca1, since the S-phase checkpoint was rescued in the same cells (Fig. 4B) and since the mutant Brca1 is expressed at levels similar to those of the wild-type protein (Fig. 4A). These results implicate Atm phosphorylation of serine 1423 of Brca1 in the regulation of the IR-induced G2/M checkpoint.

FIG. 4.

BRCA1 mutated at serine 1423 complements the S-phase checkpoint but not the G2/M checkpoint. (A) Expression of transduced hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Brca1 (wild type and Brca1 with an alanine substitution at serine 1423) was assessed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. β-Tubulin levels are shown as a loading control. (B) Replicative DNA synthesis was assessed 30 min after 10 Gy of ionizing irradiation in the complemented HCC1937 cells. Error bars represent the averages of at least triplicate samples. (C) Assessment of the G2/M checkpoint comparing HCC1937 cells complemented with either control vector, wild-type Brca1, or Brca1 with serine 1423 mutated to alanine (S1423A). (D) Quantitation of data shown in panel C, averaged over three experiments.

DISCUSSION

Exposure of cells to DNA-damaging agents can result in perturbations of cell cycle progression and in cell death. The molecular mechanisms controlling these endpoints has important implications for both cancer causation and tumor responses to cytotoxic therapies. Patients carrying mutations in both alleles of the ATM or NBS1 gene are at high risk for the development of lymphoid malignancies (22), while patients with heterozygous mutations in BRCA1 have a markedly increased risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer (14). Cells defective in the function of any of these three gene products exhibit decreased viability after exposure to ionizing irradiation (21, 22). Atm function is also required for the arrests of cell cycle progression in the G1, S, and G2 phases typically seen after the exposure of the cells to ionizing irradiation (9, 16), and Nbs1 function has been reported to be required for the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint but not for the G1 checkpoint (13, 27). However, conclusions about the role of Nbs1 in the G2 checkpoint and the importance of Brca1 in any of these checkpoints have been left somewhat ambiguous from previous reports.

Here, examination of the cell cycle arrests following IR demonstrated that cells defective in any of these three gene products lack the rapid, but transient, arrest typically seen in the S phase. Similar to the previously reported complementation of the S-phase checkpoint defects in Atm-null and Nbs1-null cells with their respective missing gene products (13, 28), introduction of wild-type BRCA1 into Brca1-null cells restored the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint. This implicates Brca1 in the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint for the first time. Though our data suggest that Atm phosphorylation of serine 1423 of Brca1 is not an important step in the IR-induced S-phase delay, this does not mean that Atm phosphorylation of Brca1 is not important for this checkpoint. Since Atm phosphorylates other sites in Brca1 (5), one or more of these other sites could be important for this function. This could be addressed by mutating each phosphorylation site individually and examining them for a failure to complement RDS.

Using a facile flow cytometric assay that distinguishes G2 cells from mitotic cells, we were also able to confirm that the progression of cells from G2 into mitosis is halted at very early times after irradiation and to demonstrate that this IR-induced cell cycle arrest requires the function of Atm and Brca1 but not Nbs1. This result confirms the earlier suggestion from studies with mouse cells (25) that Brca1 participates in the IR-induced G2/M checkpoint. Finally, since mutation of serine 1423 in Brca1, a major phosphorylation site by Atm (5, 24), abolished complementation of the G2/M checkpoint, Atm phosphorylation of this site is implicated in the G2/M checkpoint pathway. This is the first target of Atm that has been shown to affect this checkpoint. Though the mechanism by which Brca1 affects cell cycle progression in G2 remains to be elucidated, the potential involvement of serine 1423 phosphorylation in this process provides a starting point for subsequent investigations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Jim Houston, Angela Justman, and Diane Woods. We thank all members of the Kastan laboratory for helpful discussions, Yossi Shiloh for providing complemented A-T cells, and David Livingston for providing the wild-type BRCA1 cDNA.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA71387 and CA21765) and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beamish H, Williams R, Chen P, Lavin M F. Defect in multiple cell cycle checkpoints in ataxia-telangiectasia postirradiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20486–20493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canman C E, Lim D S, Cimprich K A, Taya Y, Tamai K, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Kastan M B, Siliciano J D. Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science. 1998;281:1677–1679. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canman C E, Wolff A C, Chen C Y, Fornace A J, Jr, Kastan M B. The p53-dependent G1 cell cycle checkpoint pathway and ataxia-telangiectasia. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5054–5058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carney J P, Maser R S, Olivares H, Davis E M, Le Beau M, Yates J R, III, Hays L, Morgan W F, Petrini J H. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell. 1998;93:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortez D, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge S J. Requirement of ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Brca1 in the DNA damage response to double-strand breaks. Science. 1999;286:1162–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elledge S J. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartwell L H, Kastan M B. Cell cycle control and cancer. Science. 1994;266:1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juan G, Traganos F, James W, Ray J, Roberge M, Sauve D, Anderson H, Darzynkiewicz Z. Histone H3 phosphorylation and expression of cyclins A and B1 measured in individual cells during their progression through G2 and mitosis. Cytometry. 1998;32:71–77. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19980601)32:2<71::aid-cyto1>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kastan M B, Zhan Q, el-Deiry W S, Carrier F, Jacks T, Walsh W V, Plunkett B S, Vogelstein B, Fornace A J., Jr A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia. Cell. 1992;71:587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khosravi R, Maya R, Gottlieb T, Oren M, Shiloh Y, Shkedy D. Rapid ATM-dependent phosphorylation of MDM2 precedes p53 accumulation in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14973–14977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavin M F, Shiloh Y. The genetic defect in ataxia-telangiectasia. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:177–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Ting N Y Y, Zheng L, Chen P-L, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, Lee E Y-H, Lee W-H. Functional link of BRCA1 and ataxia telangiectasia gene product in DNA damage responses. Nature. 2000;406:210–215. doi: 10.1038/35018134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim D S, Kim S T, Xu B, Maser R S, Lin J, Petrini J H, Kastan M B. ATM phosphorylates p95/nbs1 in an S-phase checkpoint pathway. Nature. 2000;404:613–617. doi: 10.1038/35007091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin A, Weber B. Genetic and hormonal risk factors in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1126–1135. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuoka S, Rotman G, Ogawa A, Shiloh Y, Tamai K, Elledge S. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10389–10394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190030497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan S E, Kastan M B. p53 and ATM: cell cycle, cell death, and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1997;71:1–25. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan S E, Lovly C, Pandita T K, Shiloh Y, Kastan M B. Fragments of ATM which have dominant-negative or complementing activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2020–2029. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Painter R B, Young B R. Radiosensitivity in ataxia-telangiectasia: a new explanation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7315–7317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotman G, Shiloh Y. ATM: a mediator of multiple responses to genotoxic stress. Oncogene. 1999;18:6135–6144. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scully R, Livingston D. In search of the tumour-suppressor functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Nature. 2000;408:429–432. doi: 10.1038/35044000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scully R, Shridar G, Vlasakova K, Chen J, Socolovsky M, Livingston D. Genetic analysis of BRCA1 function in a defined tumor cell line. Mol Cell. 1999;4:1093–1099. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiloh Y. Ataxia-telangiectasia and the Nijmegen breakage syndrome: related disorders but genes apart. Annu Rev Genet. 1997;31:635–662. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siliciano J D, Canman C E, Taya Y, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Kastan M B. DNA damage induces phosphorylation of the amino terminus of p53. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3471–3481. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tibbetts R, Cortez D, Brumbaugh K, Scully R, Livingston D, Elledge S, Abraham R. Functional interactions between BRCA1 and the checkpoint kinase ATR during genotoxic stress. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2989–3002. doi: 10.1101/gad.851000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X, Weaver Z, Linke S P, Li C, Gotay J, Wang X W, Harris C C, Ried T, Deng C X. Centrosome amplification and a defective G2-M cell cycle checkpoint induce genetic instability in BRCA1 exon 11 isoform-deficient cells. Mol Cell. 1999;3:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zampetti-Bosseler F, Scott D. Cell death, chromosome damage and mitotic delay in normal human, ataxia telangiectasia and retinoblastoma fibroblasts after X-irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 1981;39:547–558. doi: 10.1080/09553008114550651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao S, Weng Y C, Yuan S S, Lin Y T, Hsu H C, Lin S C, Gerbino E, Song M H, Zdzienicka M Z, Gatti R A, Shay J W, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, Lee E Y. Functional link between ataxia-telangiectasia and Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene products. Nature. 2000;405:473–477. doi: 10.1038/35013083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziv Y, Bar-Shira A, Pecker I, Russell P, Jorgensen T J, Tsarfati I, Shiloh Y. Recombinant ATM protein complements the cellular A-T phenotype. Oncogene. 1997;15:159–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]