Abstract

The early stages of Drosophila melanogaster development rely extensively on posttranscriptional forms of gene regulation. Deployment of the anterior body patterning morphogen, the Bicoid protein, requires both localization and translational regulation of the maternal bicoid mRNA. Here we provide evidence that the bicoid mRNA is also selectively stabilized during oogenesis. We identify and isolate a protein, BSF, that binds specifically to IV/V RNA, a minimal form of the bicoid mRNA 3′ untranslated region that supports a normal program of mRNA localization during oogenesis. Mutations that disrupt the BSF binding site in IV/V RNA or substantially reduce the level of BSF protein lead to reduction in IV/V RNA levels, indicating a role for BSF in RNA stabilization. The BSF protein is novel and lacks all of the characterized RNA binding motifs. However, BSF does include multiple copies of the PPR motif, whose function is unknown but appears in other proteins with roles in RNA metabolism.

Many forms of gene regulation occur posttranscriptionally. These include nuclear functions, such as alternative splicing of mRNAs, and a variety of processes in the cytoplasm, such as regulated stability, localization, translation, and modification of mRNAs. Most of the cytoplasmic forms of regulation act primarily in controlling the level or distribution of proteins encoded by the affected mRNAs and are especially useful in two situations. One is when the level of a protein must be changed very rapidly. Although activation or repression of transcription can modulate the level of gene expression, mechanisms that act on mRNAs are more direct and thus can generate more rapid changes. Cytoplasmic forms of posttranscriptional control are also common for maternal mRNAs. Transcripts made by the mother and contributed to the egg may be translated long after their synthesis, and the timing of translational activation or repression can be crucial for normal development (40). Similarly, the localization of some maternal mRNAs to specific regions within the egg can be an essential form of regulated gene expression (5).

Numerous examples of posttranscriptional control of maternal mRNAs have emerged from the analysis of Drosophila melanogaster early development (22). One of these is the maternally contributed bicoid (bcd) mRNA, which encodes a protein that is largely responsible for organizing the anterior body pattern of the embryo (8, 9). Correct deployment of the Bcd protein in an anterior gradient in the embryo relies on prelocalization of bcd mRNA to the anterior pole of the oocyte, where it persists into embryogenesis. Accumulation of Bcd protein occurs only after fertilization, suggesting that the bcd mRNA is not translated during oogenesis (10). Activation of translation is likely to be mediated by cytoplasmic polyadenylation of the bcd mRNA, which occurs early in embryogenesis (32). The bcd mRNA is stable early in embryogenesis but rapidly disappears after about 3 h of growth, revealing a role for mRNA stability or instability in its control (38). Each of these regulated aspects of bcd mRNA activity—mRNA localization, translational activation, and stability—is mediated by cis-acting elements present in the bcd mRNA 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (30, 32, 38). Each element is expected to function by binding one or more regulatory proteins.

Most of the known regulated mRNAs with prominent roles in early Drosophila development have been identified through genetic approaches. Similar approaches have proven to be much less useful for finding the expected regulatory proteins that bind specifically to these mRNAs. Although several genes have been implicated in bcd mRNA localization (36, 37), of these only staufen has been shown to encode an RNA binding protein that interacts specifically with bcd mRNA (12). Staufen acts only very late in the localization process (27, 37), so other RNA binding proteins must be required. Notably, most of the proteins that bind to cis-acting elements responsible for posttranscriptional control of Drosophila maternal mRNAs have been identified by biochemical rather than genetic strategies (15, 17, 21, 29, 34). One possible explanation for the limited success of genetic approaches invokes redundancy. For example, multiple proteins could act in recognition of the bcd mRNA localization signals, and loss of a single binding protein might incur only a subtle defect. In this situation, a mutant defective for a binding protein would have a weak or imperceptible phenotype and would not be recovered from simple mutant screens. There is already strong evidence for such redundancy in bcd mRNA localization (27, 28); other regulatory processes might also involve redundancy, explaining why genetic approaches have failed to identify many of the regulatory factors.

In previous work we initiated a biochemical approach to identify regulatory proteins that bind to the bcd mRNA. We described a protein, Exl, that binds to a specific region of the bcd mRNA 3′ UTR, and we presented evidence supporting a role in mRNA localization (29). Here we have extended that biochemical approach to find additional binding proteins. We report the isolation of a protein, BSF, that binds specifically to the bcd mRNA 3′ UTR. Characterization of the function of BSF by using both biochemical and genetic assays very strongly suggests that it acts in stabilization of the bcd mRNA during oogenesis and that it plays a redundant role in this process. Our results add another form of posttranscriptional control to those known to act through the bcd 3′ UTR. Notably, the sequences required for stabilization during oogenesis are distinct from those involved in destabilization during embryogenesis (38), and so the processes appear to be distinct.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNAs.

DNA fragments corresponding to wild-type IV/V, IV, and V RNAs (27), all subdomains of the bcd mRNA 3′ UTR (see Fig. 1), were subcloned into transcription vectors for preparation of RNA probes (p2865, p5008, and p2866). Linker scanning (LS) mutants were constructed by standard PCR methods using oligonucleotide primers designed to replace adjacent 10-nucleotide (nt) segments of IV/V with the sequence GAAUCGAUUC. LS2 replaces nt 4399 to 4408 (coordinates from GenBank accession number X51741) and LS3 replaces nt 4409 to 4418, and the series continues with 10-nt substitutions up to LS27, which replaces nt 4649 to 4658. LS15 replaces UAUUUUCAAU (nt 4529 to 4538). All mutants were constructed in transcription vectors to allow synthesis of sense RNAs for use as probes in RNA binding assays. Individual LS mutants, flanked by XbaI restriction sites, were subcloned into the P transformation vector p2405. This vector includes the osk promoter, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding region, and a short 3′ UTR with a polyadenylation signal; the cloning site is within the 3′ UTR (26). The wild-type version is P[gfpIV/V], and the mutants are, for example, P[gfpIV/VLS15]. For experiments to test the function of BSF, a second reporter transgene bearing the IV/V localization signal was also used. It makes use of the bicoid promoter and includes a lacZ sequence tag (27).

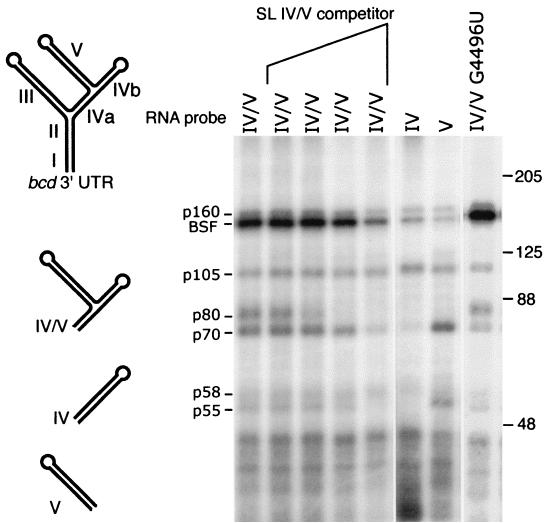

FIG. 1.

Proteins that bind to IV/V RNA. A schematic diagram of the predicted secondary structure of the bcd mRNA 3′ UTR is shown at the left, with individual domains indicated by roman numerals. The subdomains of the RNA used in this work, IV/V, IV (created by site-directed mutagenesis to remove V; see reference 27), and V, are shown below. UV cross-linking was used to monitor binding of Drosophila ovarian proteins to 32P-labeled RNA probes (identified above each lane). Individual binding proteins are identified by approximate molecular size at the left (migration of size standards noted at the right). For the competition binding experiments, 0.1-, 1-, 12-, or 122-fold molar excess cold IV/V RNA was added to the binding reactions. Subdomains of IV/V RNA (IV and V) or a mutant IV/V that is defective in RNA localization in vivo (G4496U) (27) were used to better define binding specificities. Two proteins, p55 and p70, bind sites in V based on their strong binding to IV/V and V and weak or nondetectable binding to IV. Three proteins, p58, p105, and p160, bind to all probes tested. Two proteins, p80 and BSF, require the intact IV/V RNA for strong binding. None of the binding interactions is noticeably affected by the G4496U point mutation. SL, stem-loop.

The cDNA clone SD10676 of the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) was obtained from Research Genetics (Birmingham, Ala.). Restriction fragments of the cDNA were subcloned for DNA sequencing. A deletion derivative of bsf encoding the N-terminal 1,007 amino acids was subcloned into the pET3a vector for expression in Escherichia coli.

Antibodies.

The N-terminal 1,007 amino acids of BSF were expressed in E. coli, partially purified, and used as an immunogen for production of antiserum in rats. Antiserum to the BSF protein was tested by Western blot analysis of TNT reactions (Promega) expressing either BSF or a control protein in rabbit reticulocyte lysates. A band of approximately 150 kDa was detected in ovary extracts and in the lysates expressing BSF and was absent in the control lysate (R. Mancebo and P. M. Macdonald, unpublished).

Drosophila ovarian extracts. (i) Large-scale isolation of ovaries.

Embryos from W1118 flies were collected overnight onto egg-laying plates in large fly houses and were seeded into larval containers. The larvae and adults that emerged were fed yeast paste (autoclaved to reduce the amount of proteolysis that might occur during ovary extract preparation if active yeast were present in the gut). The adults were homogenized in approximately 10 liters of IB (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) with a blender using short pulses at low speed. The total amount of flies homogenized was 215.5 g. The homogenate was first filtered through a 500-μm mesh membrane and collected onto a 70-μm mesh membrane. The filtrate that was retained on the 70-μm mesh was then filtered through a 150-μm mesh and collected onto a 60-μm mesh membrane, followed by washes with IB. The settled volume of filtrate was 1.5 ml and was enriched for all stages of egg chambers.

(ii) Preparation of large-scale ovary extract for purification.

The filtrate from the large-scale isolation of ovaries was washed four times with 20 ml of EB (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 mM benzamidine, 2 μg of pepstatin per ml, 2 μg of leupeptin per ml). Egg chambers were disrupted by Dounce homogenization in EB 100 times on ice. The extract was filtered through Miracloth and spun at ∼20,000 × g for 15 min at 0°C in a microcentrifuge. The clear supernatant was removed and recentrifuged. The clear supernatant from the second spin was removed, mixed with cold 50% glycerol to a final concentration of 10% glycerol, and frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath. This preparation yielded approximately 29.8 mg of protein in 1.78 ml of extract.

(iii) Preparation of small-scale ovary extract.

Ovaries were individually dissected in water at room temperature and placed in cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Isolated ovaries were then washed four times with cold EB-O (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5 to 7.7], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml). Washed ovaries were homogenized in approximately 2.5 volumes of EB-O on ice in a microcentrifuge tube with a plastic pestle. Extract was spun at ∼20,000 × g for 15 min at 0 to 4°C in a microcentrifuge. The clear supernatant was removed, recentrifuged if any particular matter remained, mixed with approximately 0.7 volume of 50% cold glycerol, and frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath.

RNA binding assays.

UV cross-linking assays were performed as described (17), except that the binding buffer included 10 mM EDTA, 0.9 mM benzamidine, 0.9 μg of pepstatin per ml, and 0.9 μg of leupeptin per ml. For competition binding assays (see Fig. 1), increasing amounts of IV/V RNA (trace labeled to facilitate quantitation) were added to binding reactions at room temperature 5 to 10 min prior to addition of labeled IV/V RNA probe. Proteins for the binding assays were from ovarian extracts (described above) or synthesized from cDNAs in coupled transcription and translation extracts (Promega).

Purification of BSF.

Ovary extract from the large-scale preparation described above was fractionated on a 1-ml Q-Sepharose Hi-Trap column (Pharmacia) using an Econo Low-Pressure Chromatography System (Bio-Rad) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was loaded and washed with buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF) also containing 100 mM NaCl. Proteins were eluted in buffer A containing 298 mM NaCl. Eluted fractions were tested for P150 binding activity using the UV cross-linking assay described above.

Fractions demonstrating BSF activity from the Q-Sepharose column were incubated with 65 μl of Reactive 4 Blue Dye resin at 4°C for approximately 4.5 h. The supernatant was removed and the resin was washed with 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, and 1 μg of leupeptin per ml. Proteins bound to the dye resin were eluted with IV/V RNA at 4°C on a rotator for approximately 1.5 h. The elution solution contained 10 μg of IV/V RNA (made using the T7-MEGAshortscript transcription system from Ambion) and 350 μg of yeast tRNA in 260 μl of elution buffer (approximately 2.2 mM MgCl2, 6.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 11 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 mM benzamidine, 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml). Eluted proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electroblotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (ProBlott; Applied Biosystems).

Protein sequencing.

The 150-kDa protein band was excised from the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and wetted with 1 μl of methanol. The band was reduced and alkylated with isopropylacetamide (18) followed by digestion in 20 μl of 0.05 M ammonium bicarbonate containing 0.5% Zwitergent 3-16 (Calbiochem) with 0.2 μg of trypsin (Frozen Promega Modified) at 37°C for 17 h (23).

Peptides generated by trypsin were subjected to collision-induced dissociation in an ion trap mass spectrometer (LCQ; Finnigan MAT). A 1-μl aliquot (5%) of the tryptic digest was loaded onto a 75-μm inside diameter, 360-μm outside diameter, 20-cm length of fused silica capillary packed with 15 cm of POROS 10R2 reverse-phase beads (PerSeptive Biosystems). Peptides were eluted with 15 min of acetonitrile gradient at a flow rate of 200 nl/min as previously described (3).

Peptide masses and selected b and y series fragment ions were used to search an in-house (Genentech) protein and DNA sequence database with an enhanced version of the FRAGFIT program (2, 16).

bsf genetics.

The P element stock l(2)k07109, generated and characterized by the BDGP, was obtained from Amy Beaton at the BDGP. The stock carries two P element insertions, one in 25F1-2 and one in 36E3-4. We used complementation tests with Df(2L)M36F-S5 to show that the 36E P insertion is not lethal. Because the 36E P insertion reduces but does not eliminate BSF protein (see Fig. 6A), we initiated efforts to use this insertion to make stronger alleles of bsf. However, recombination and complementation tests strongly suggest that the 36E P element of l(2)k07109 is no longer w+, rendering it useless for any screen for stronger alleles of bsf that relies on loss of w+. Consequently we halted our efforts to obtain stronger alleles.

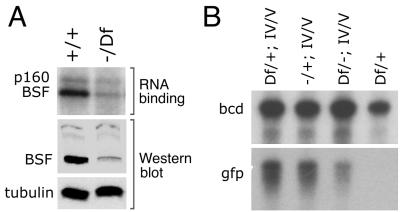

FIG. 6.

A mutant with a reduced level of BSF protein has reduced levels of IV/V RNA. (A) Ovaries from wild-type and bsf1/Df(2L) M36F-S5 females were tested for levels of BSF RNA binding activity (upper panel) and BSF protein (middle panel). RNA binding was monitored by a UV cross-linking assay. The binding to p160 (see Fig. 1) serves as a control to demonstrate that similar amounts of wild-type and mutant extracts were used for the assays. Levels of BSF protein in wild-type and mutant extracts were determined by Western blot analysis using antibodies raised against a bacterially expressed part of BSF. Loading controls are provided by the light background band at the top of the BSF blot and reprobing of the blot with anti-tubulin antibodies (bottom panel). (B) RNase protection assays of ovarian RNA levels for endogenous bcd mRNA and the reporter gfp mRNA bearing the wild-type IV/V domain of the bcd 3′ UTR. The endogenous bcd mRNA is not affected by reduction in the level of BSF and is used to normalize the amounts of RNA used for each assay. RNAs are from ovaries of flies with the genotypes indicated at the top (a plus sign is used to indicate bsf1, as carried on a Sp or CyO chromosome). Df and a minus sign indicate the deficiency and P insertion mutants, respectively [Df(2L)M36-S5 and bsf1], and the reporter RNA transgene is indicated by IV/V. The last lane is a control to show that no gfp RNA signal is detected in the absence of the reporter transgene. Flies transheterozygous for Df(2L)M36-S5 and bsf1 (third lane) show a consistent 3- to 5-fold reduction in reporter RNA levels (as determined by phosphorimaging analysis; see Materials and Methods) relative to the control flies (first two lanes). Similar results were obtained using a different transgene bearing the IV/V localization signal but driven by the bcd promoter.

Determination of mRNA levels in transgenic flies.

Females bearing individual LS mutant transgenes were fattened, their ovaries were dissected, and their RNA was isolated (25). For each reaction, 10 μg of nucleic acid was mixed with labeled RNA probes from both the gfp and bcd genes to compare the levels of LS mutant IV/V RNAs with endogenous bcd mRNA, respectively, in multiprobe RNase protection assays (41).

To test the role of BSF in stabilization of bcd mRNA, Df(2L)M36-S5/CyO Dp(2;2)M(2)m+ females were crossed to l(2)k07109/CyO; P[gfpIV/V]/TM2 males. Progeny females of the genotype Df(2L)M36-S5/l(2)k07109; P[gfpIV/V]/+ were fattened in yeasted vials for 2 to 4 days. Ovaries were dissected, RNA was isolated, and the levels of reporter (gfpIV/V) and endogenous bcd mRNAs were determined by RNase protection assay (RPAIII; Ambion). As controls, RNAs from the sibling genotypes of Df(2L)M36-S5/CyO; P[gfpIV/V]/+, l(2)k07109/CyO; P[gfpIV/V]/+, and Df(2L)M36-S5/CyO; +/TM2 were also tested. RNase protection assays were quantitated by phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics) using three independent sets of assays. These experiments were repeated using the bcd+lacZIV/V reporter (27) with similar results.

Immunolocalization of BSF.

Adult females were fattened and ovaries were dissected in PBS. Ovaries were disrupted by being rapidly pipetted through a drawn-out pasteur pipette and were fixed for 30 min in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 200 μl of PBS, 40 μl of 37% formaldehyde, and 1 ml of heptane. The samples were washed in several changes of PBT (PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100) and 5% goat serum, incubated overnight in rat anti-p150 diluted 1:1,000 in PBT and 1% goat serum, washed five to seven times in PBT and 5% goat serum, incubated for 2 h in Cy5-labeled goat anti-rat secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunochemicals) diluted 1:600 in PBT, and washed in PBT. Samples were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs) and examined by confocal microscopy using a Leica TCS SPII microscope.

Specificity of the antibodies was determined by comparing fluorescence levels in wild-type and bsf1/Df(2L)M36F-S5 transheterozygous ovaries. To allow a direct comparison of the two genotypes, the wild-type flies also carried a transgene expressing GFP fused to asparaginyl tRNA synthetase, which is dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (R. Mancebo and P. M. Macdonald, unpublished). The wild-type and bsf mutant flies were mixed and processed (dissected, fixed, and stained) together, with the genotypes distinguished by the presence or absence of GFP fluorescence.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Our sequence of the SD10676 cDNA has been deposited at GenBank with accession number AF327844.

RESULTS

To search for proteins that may regulate the activity or distribution of bcd mRNA we focused on the IV/V region (Fig. 1), a 271-nt portion of the bcd 3′ UTR that supports a normal pattern of mRNA localization during oogenesis (27). Unlike the complete 3′ UTR, the IV/V RNA lacks redundant information for the initial step of bcd mRNA localization. Specifically, the localization activity of IV/V can be greatly reduced by a point mutation (G4496U), while the same mutation has only a subtle and transient effect on the activity of the complete 3′ UTR. The absence of functional redundancy is a prerequisite for experiments in which an attempt is made to correlate a protein binding site with a biological activity.

Extracts prepared from Drosophila ovaries were tested for the presence of proteins that bind to IV/V RNA using a UV cross-linking assay. A number of proteins bind under these conditions, and all those larger than 50 kDa are identified in Fig. 1. The assays were also performed in the presence of increasing amounts of competitor RNA as an initial test for binding specificity. Most of the bands detected in the assay are unaffected by addition of the competitor, but the binding of four proteins, p55, p70, p80, and BSF, is clearly reduced. To explore a possible role for any of the proteins in bcd mRNA localization, RNA probes corresponding to the isolated parts of IV/V (predicted stem-loops IV and V) (Fig. 1) were used in separate binding assays; RNAs IV and V have no localization activity in vivo and thus may fail to bind one or more localization factors (27). Many proteins bind equally well to all probes. Two proteins, p55 and p70, bind to V RNA but not IV RNA, suggesting that they recognize sites contained entirely within V. Finally, p80 and BSF bind much better to IV/V RNA than to either of the isolated parts (which do not support mRNA localization) and are thus the best candidates to act in mRNA localization. To explore further a possible role for the cross-linking proteins in bcd mRNA localization, a binding assay was done with a point-mutated IV/V RNA (G4496U) that interferes with mRNA localization in vivo (27). The G4496U mutation had no effect on the binding of any of the proteins detected in this assay. Although this result does not rule out involvement of any of the binding proteins in bcd mRNA localization, it does suggest that other roles may be more likely. Here we characterize one of the proteins, BSF, and we describe experiments that assess its function. Our data argue very strongly for a role in stabilization of bcd mRNA, so we refer to this protein as bicoid mRNA stability factor or BSF.

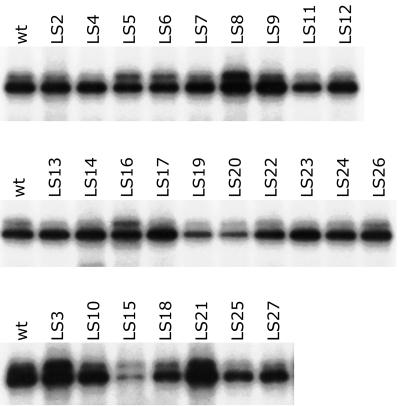

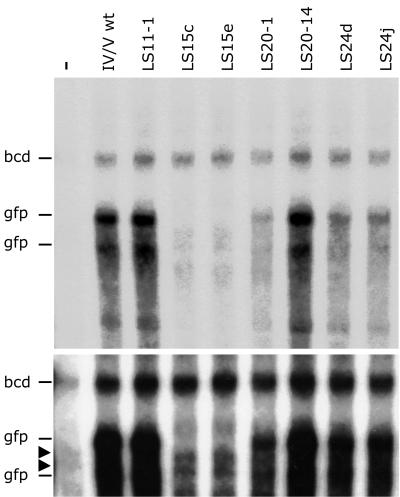

Identification of a stability element within the bcd 3′ UTR that is recognized by BSF.

Our strategy for testing the role of BSF was to first identify mutations in IV/V RNA that interfere with BSF binding in vitro and then to determine the consequences of these same mutations in vivo. We used LS mutagenesis to create a series of 27 mutants that collectively alter most of the 271 nt of IV/V. Each mutant replaces a 10-nt segment of IV/V with a synthetic sequence (see Materials and Methods). Wild-type and mutant IV/V RNAs were used as probes in binding assays, as shown in the three panels of Fig. 2. Each panel represents a separate experiment, and band intensities should be compared to the wild-type control from the same experiment. One mutant RNA, LS15, is most severely impaired in BSF binding. Several others (e.g., LS19 and LS20) are also impaired but to a lesser extent. Almost all of the same LS mutants were also tested in vivo. Each mutant was introduced into a reporter construct (27), transgenic fly strains were established, and patterns of mRNA localization in transgenic ovaries were monitored by in situ hybridization. For the LS15 mutant, no localized reporter mRNA was detected in any of four independent transgenic fly stocks, and the underlying cause was unique among all mutants tested: the LS15 mutant fails to accumulate any mRNA (Fig. 3). In comparison, the LS11 mutant, which is completely defective in mRNA localization, retains normal levels of transgene mRNA (a complete phenotypic description of the full set of linker scan mutants will be published elsewhere). The simplest interpretation of our results is that the LS15 mutant destabilizes the IV/V RNA. Although we cannot exclude alternate explanations that invoke low-probability events (such as alteration of the transgene during transposition into the Drosophila genome or selective and consistent targeting of the transgene to regions of the genome that interfere with its expression), data presented below are fully consistent with the conclusion that the LS15 mRNA is unstable and that instability is the consequence of the defect in BSF binding.

FIG. 2.

BSF binding to LS mutant IV/V RNAs. LS mutant RNA probes were used for UV cross-linking assays. Each panel shows a separate experiment testing the binding of BSF to a subset of the mutants. LS15 displays the most severe reduction in BSF binding (the autoradiographic exposure is longer in this panel than in others; note the intensity of the wild-type [wt] band). Several mutants, including LS19 and LS20, also show reduced BSF binding, but to a lesser extent. Some of the mutants display enhanced binding to BSF. Although we do not know the reason for this effect, it could reflect subtle differences in RNA folding, and we have observed similar effects for other RNA binding proteins (17).

FIG. 3.

Flies carrying LS15 transgenes fail to accumulate IV/V RNA. The autoradiograph shows RNase protection assays that probe the levels of both endogenous bcd RNA and transgenic gfp reporter RNA in the same reaction (designated at the left). The two gfp bands presumably reflect RNase cleavage within the probe, a common occurrence. RNA samples were from females carrying a wild-type gfp IV/V reporter (IV/V wt) or LS mutant gfp IV/V reporter or from 0- to 24-h embryos with no transgene (lane labeled with a minus). The latter lane reveals background bands (indicated with arrowheads) that migrate near the gfp signals but are not from gfp, being present in RNA samples lacking gfp RNA. Neither of two independent transgenic stocks of the LS15 mutant shows detectable reporter mRNA (there is no signal at the positions of the gfp reporter bands, shown more clearly in the lower panel, which is a longer exposure of a part of the autoradiograph shown in the upper panel). Other LS mutant transgenic stocks display some variation in transcript levels, as seen here for two independent LS20 stocks, but the gfp RNA can always be detected, in contrast to what is observed for the LS15 stocks.

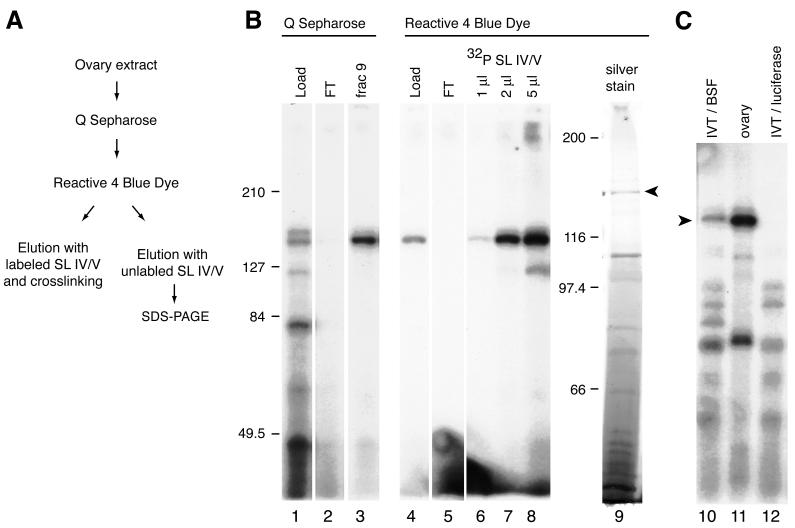

Biochemical purification of BSF.

To initiate a biochemical and genetic analysis of BSF, we purified the protein from isolated Drosophila ovaries. The purification is outlined in Fig. 4A and is described in detail in Materials and Methods. For the penultimate step of purification, proteins were bound to Reactive 4 Blue Dye and specifically eluted using IV/V RNA. Chromatography on the dye column was first performed on an analytical scale, by eluting with radiolabeled RNA and testing fractions for the presence of BSF by a UV cross-linking assay (Fig. 4B, lanes 4 through 8). The separation was repeated at a preparative scale using unlabeled IV/V RNA. Silver staining of eluted fractions separated by SDS-PAGE revealed a single prominent protein band in the expected size range as well as a number of other smaller proteins (Fig. 4B, lane 9). The candidate BSF protein was excised from the gel and processed for sequencing.

FIG. 4.

Purification of BSF. (A) Outline of the purification. SL, stem-loop. (B) Analysis of BSF during the purification steps. All lanes, except lane 9, show UV cross-linking assays. Lanes 1 through 3 show the purification of BSF away from other RNA binding activities during Q-Sepharose fractionation. Lanes 4 through 8 show the elution of BSF from Reactive 4 Blue Dye. All of the BSF binding activity is retained on the column (lanes 4 and 5) and can be eluted with labeled IV/V RNA (lanes 6 through 8). Lane 9 shows a silver-stained gel of the eluted proteins from the Reactive 4 Blue Dye. An arrowhead indicates the BSF protein. FT, flowthrough. (C) A cDNA identified from peptide sequences from purified BSF encodes a 150-kDa protein that binds IV/V RNA. Each lane shows the result of a UV cross-linking assay with IV/V RNA probe and the following extracts: lane 10, in vitro translation (IVT) of the putative bsf RNA in rabbit reticulocyte lysates; lane 11, ovary extract; lane 12, in vitro translation of luciferase RNA in rabbit reticulocyte lysates. Proteins synthesized by in vitro translation (lanes 10 and 12) are not purified, and the background binding activities are those from the translation system.

Amino acid sequences were obtained from 11 peptides from the purified BSF protein. Six of these peptides correspond to three expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from the BDGP; we subsequently found all three ESTs to be derived from the same mRNA, which also contains sequences corresponding to three of the other sequenced peptides. One of the EST cDNAs (SD10676) was translated in vitro, and the reaction products were used in the UV cross-linking assay. As shown in Fig. 4C, the cDNA encodes a protein of about 150 kDa that binds IV/V RNA, supporting the conclusion that the cloned gene is bsf. Genetic analysis (below) confirms this conclusion.

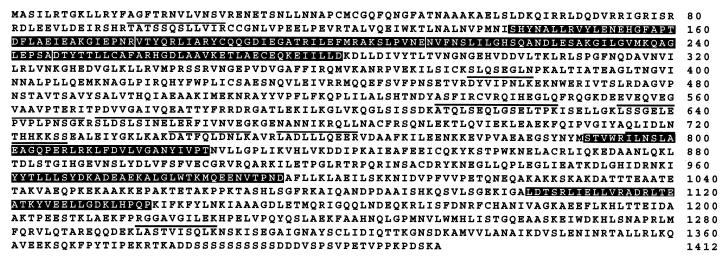

BSF contains multiple copies of the PPR motif.

The cDNA SD10676, which encodes BSF, was completely sequenced. The single large open reading frame predicts a protein of 1,412 amino acids and includes 9 of 11 peptide sequences obtained from the purified BSF protein (Fig. 5). The most notable feature of the BSF sequence is the presence of seven copies of the PPR motif, with four copies adjacent to one another near the amino terminus and three copies dispersed over the carboxyl-terminal half of the protein. The PPR motif, which is usually about 35 amino acids long, has no assigned function but has already been identified in over 200 proteins that are widely represented in plant organelles (33). Two proteins that contain the motif have been characterized genetically, and each plays a role in RNA metabolism (4, 14, 31). Notably, the PPR-containing PET309 protein has been shown to act in either processing or stabilization of certain RNAs in yeast (31). Based on these observations, BSF is a member of a new protein family that may have a common function in RNA metabolism.

FIG. 5.

Predicted BSF protein sequence. The sequence shown is that predicted by conceptual translation of the SD10676 EST cDNA. Nine peptides sequenced from purified BSF are overlined (note that two peptides, LSSGELEPVPLPNSGK and ILNSLAEAGQPER, are each split between two lines). The seven iterations of the PPR motif are indicated by black boxes with white text. The protein corresponds to CG10302 of the proteins predicted from analysis of the Drosophila genome sequence (1) (http://www.fruitfly.org/annot/). There are several differences between our experimental data and the characteristics of the predicted protein. The most significant is that our sequence includes an additional 137 amino acids at the amino terminus. One of the sequenced peptides lies within this region, confirming that this part of the cDNA is indeed translated.

Sequence comparisons of BSF with those of the GenBank database identify two proteins that are most closely related, a human leucine-rich protein of unknown function (expectation [E] value of <10−136) and a predicted Drosophila protein (E < 10−68). Both proteins also contain multiple copies of the PPR motif, although the extensive homology between BSF and the leucine-rich protein is not limited to these repeated structural elements.

Despite the biochemical evidence that BSF is an RNA binding protein, none of the known RNA binding motifs are present in the protein. Thus, BSF appears to define a novel class of RNA binding protein.

Mutations that reduce the level of BSF in the cell lead to a reduction of IV/V RNA.

The cytological map position of the bsf gene is on the left arm of the second chromosome at 36E3-4 (BDGP). A search of the BDGP database revealed that none of the P element insertion mutants (35) whose exact chromosomal position has been determined by DNA sequencing lies in or near the bsf gene. However, there are other P element insertions in the same region that have not been mapped so precisely. These mutants were obtained, and heterozygous flies were tested for BSF protein levels by Western blot analysis. One mutant stock, l(2)k07109, displays a reduced level of BSF. The l(2)k07109 chromosome carries two P element insertions on the second chromosome, one in the bsf region and one in 25F. The latter insertion is responsible for the lethal phenotype, as the BDGP has shown that l(2)k07109 is lethal in trans to a deficiency removing 25F, and we found that l(2)k07109 is viable in trans to Df(2L)M36F-S5, a deficiency that removes all of 36E. The viability of l(2)k07109/Df(2L)M36F-S5 flies allowed us to test them for BSF protein levels, which are very substantially reduced (Fig. 6A). Thus, the 36E P insertion of l(2)k07109 reduces the level of BSF protein, a common phenotype for P element mutants, and we refer to the P insertion as bsf1. Our efforts to use the bsf1 flies to generate stronger alleles have failed for reasons outlined in Materials and Methods. Nevertheless, even in the absence of a null allele the bsf1/Df(2L)M36F-S5 transheterozygotes may provide a partial loss-of-function phenotype for bsf.

Flies transheterozygous for bsf1 and Df(2L)M36F-S5 are viable and fertile, with no obvious morphological defects in oogenesis. When eggs from such females are fertilized by wild-type or bsf1 sperm, they progress normally through embryogenesis and display no cuticular pattern defects (development is arrested later for bsf1/bsf1 individuals because of the 25E lethal mutation on the chromosome). As a first test for a molecular defect in the ovaries of bsf1/Df(2L)M36F-S5 females, we examined the level of endogenous bcd mRNA but found no substantial difference relative to the wild type (data not shown). However, the apparent mRNA instability phenotype associated with LS15 (the LS mutant defective in BSF binding) is detected for transgenes containing only the IV/V portion of the bcd mRNA 3′ UTR (Fig. 3), while deletion from the complete bcd 3′ UTR of the region corresponding to LS15 has no substantial effect on mRNA levels (mutants Δ15 and Δ16 of the gene are described in reference 28). Thus, LS15 could block the action of only a single component of a redundant stabilizing system, and reduction of BSF activity would only be detected when redundancy is eliminated. Accordingly, we tested the level of the reporter mRNA bearing the wild-type IV/V RNA in flies transheterozygous for bsf1 and Df(2L)M36F-S5. Compared to control flies, the bsf mutant flies display a consistent three- to fivefold reduction in the level of wild-type IV/V RNA (Fig. 6B). We have no direct evidence that proves a mechanism by which a reduction in BSF levels reduces the level of IV/V RNA. Nevertheless, the fact that BSF binds to sequences within IV/V RNA argues for a posttranscriptional role, an interpretation consistent with the mRNA stabilization role suggested for BSF by the LS mutant analysis.

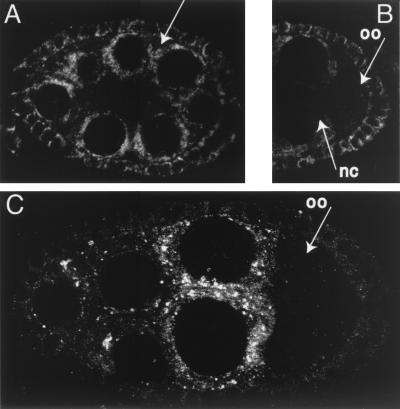

BSF appears in particles within the cytoplasm during oogenesis.

The subcellular distribution of BSF protein was determined by immunofluorescent detection in whole-mount ovaries (Fig. 7). At all stages of oogenesis the protein is cytoplasmic. During the previtellogenic stages of oogenesis BSF is present in both the nurse cells and the oocyte at similar levels (Fig. 7A and B). Within the nurse cells BSF appears primarily in regions surrounding the nuclei, and within these regions the protein is often concentrated in a punctate pattern (Fig. 7A). As oogenesis proceeds (Fig. 7C), the tight association of BSF with nurse cell nuclei is lost. The particulate appearance of BSF is enhanced, but the particles are more evenly dispersed throughout the cytoplasm of the nurse cells. In the oocyte the BSF levels are reduced relative to the nurse cells. At no time does BSF appear to be concentrated at sites of bcd mRNA accumulation, at either the apical regions of the nurse cells or the anterior margin of the oocyte.

FIG. 7.

Distribution of BSF in ovaries. Anti-BSF antibodies were used to detect BSF protein in whole-mount ovaries. Signal specificity was confirmed by comparison of wild-type ovaries (shown) with bsf1/Df(2L)M36F-S5 ovaries (see Materials and Methods). (A) Egg chamber showing the concentration of BSF in a punctate pattern surrounding nurse cell nuclei. A similar distribution is observed in the somatic layer of follicle cells that surround the nurse cells and oocyte, with differences in the degree of perinuclear concentration among different follicle cells. (B) Posterior part of an egg chamber in which the level of BSF in the oocyte (oo) is similar to that in the nurse cells (nc). (C) Vitellogenic stage egg chamber. BSF is now present at lower levels in the oocyte. Within the nurse cells the punctate distribution of BSF persists, but the concentration of BSF at the periphery of nurse cell nuclei is lost. This egg chamber displays a preferential accumulation of BSF in the nurse cells closest to the oocyte; this pattern is common but not universal. The follicle cells continue to show variable concentrations around the nuclei.

DISCUSSION

The bcd mRNA has long served as a model example of the importance and variety of posttranscriptional regulatory events that can be mediated by the 3′ UTR. Sequences that direct the subcellular localization, translation, and embryonic degradation of bcd mRNA have all been found within the 3′ UTR. Here we have identified an additional function, mRNA stabilization during oogenesis. Our data indicate that stabilization of the IV/V domain of the bcd 3′ UTR is achieved by interaction of the BSF protein with a cis-acting stability element in the RNA. Three lines of evidence support this model of BSF action. First, mutation of the stability element eliminates accumulation of RNA. Second, BSF binding is greatly reduced by the same mutation in the RNA stability element. And third, a mutant with significantly reduced expression of BSF displays a reduction in the level of IV/V RNA. Taken together, these data make a very strong case for BSF-mediated stabilization of bcd mRNA.

Redundancy.

The consequence of mutating either the IV/V RNA stability element or bsf is the elimination or reduction, respectively, of the reporter mRNA bearing the IV/V 3′ UTR. In contrast, mutation of bsf has no discernable effect on endogenous bcd mRNA. Similarly, deletion of the LS15 region from the full bcd 3′ UTR is tolerated, and the deletion mutant RNAs are readily detectable (28). The striking context dependence of mutating either the cis or trans components of this RNA stabilization system suggests that there is redundancy in the stabilization process: sequences outside IV/V are sufficient for stabilization, and another factor(s) can perform the same function as BSF. This redundancy is not surprising given the redundancy already demonstrated for localization of bcd mRNA (27). Indeed, the IV/V subdomain of bcd RNA was used in this work because it lacks the mRNA localization redundancy of the full 3′ UTR.

An alternative explanation for the observation that a mutation in the RNA stabilization element leads to a reduction in the level of IV/V RNA while a deletion of the stabilization element from the full bcd 3′ UTR appears to have no affect is suggested by known mechanisms of mRNA stabilization. Specifically, binding of the iron response element protein to sequences in the transferrin receptor mRNA 3′ UTR blocks endonucleolytic attack and thus stabilizes the mRNA (7). It is possible that the LS15 mutant disrupts the BSF binding site but not a nearby nucleolytic cleavage site and thus confers instability. In contrast, the larger deletion mutants that do not affect stability of the bcd 3′ UTR (Δ15 and Δ16 of the gene described in reference 28; 45 and 54 nt deleted, respectively) might eliminate both the protection and cleavage elements, making them resistant to targeted degradation. Distinguishing among these and other possible explanations will require more detailed analysis of the cis-acting elements.

Interaction of BSF with IV/V RNA.

BSF binds IV/V RNA significantly better than either IV or V RNA alone. IV/V may be a better binding substrate because it contains more iterations of a repeated binding site. Alternatively, the binding site may consist of elements from both the IV and V regions, or presentation of the binding site may require a structure that only the complete IV/V RNA can adopt. In this case the weaker binding to the isolated parts could represent nonspecific binding. Although several LS mutants do reduce BSF binding, as might be expected if each disrupts one copy of a repeated binding site, the fact that the LS15 mutant has a more dramatic effect argues against simple repetition of equivalent binding sites. The other option, that BSF recognizes a site whose composition or formation requires the intact IV/V, appears to be more consistent with our data, although the options are not mutually exclusive. The notion that IV/V is structured is not new, and there are now several studies either suggesting or demonstrating that at least part of this region must adopt a specific folding for mRNA localization (13, 24, 26).

The RNA binding domain of BSF appears to be novel, as none of the known RNA binding motifs appear in the protein. The single type of recognizable domain, the PPR motif, is also found in other proteins that act in RNA metabolism (14, 31), and one or more of the seven copies of this motif in BSF could contribute to RNA binding. However, BSF must also fulfill its function of stabilizing the IV/V RNA, and the PPR motifs could act in this process. Identification and analysis of the BSF RNA binding domain may resolve these issues.

mRNA stability in Drosophila development.

Control of mRNA stability serves an important role in Drosophila development. Multiple transcripts with roles in development of the adult peripheral nervous system are normally destabilized posttranscriptionally by conserved 3′ UTR regulatory sequences (19, 20). In the embryo the transcripts of the pair-rule genes have extremely short half-lives, a property that contributes to their restriction to the apical cytoplasm at the periphery of the blastoderm (11). Additionally, a number of maternal mRNAs, including bcd, are programmed for rapid turnover during the first few hours of embryogenesis, with some variation in the timing of elimination (6). Recent studies on the timing of degradation and the cis-acting elements acting in this process for several such mRNAs have revealed the existence of at least two distinct degradation pathways (6). For some maternal mRNAs instability elements have been identified, although no common features have yet emerged (6, 34, 38).

There are fewer examples of mRNAs that are actively stabilized, perhaps in part because evidence for stabilization would most likely come from directed mutagenesis of the mRNA, experiments typically not done without some preliminary indication that a regulatory sequence exists. A notable exception is the α2-globin mRNA, which is extraordinarily stable in erythroid cells. A naturally occurring mutation causes destabilization, although the mutation does not directly affect the sequences conferring stability. Instead, the stop codon is inactivated, allowing ribosomes to displace stabilizing factors from the 3′ UTR of the mRNA (39). The best examples of actively stabilized mRNAs in Drosophila are those where stabilization is a local phenomenon; the retention of an mRNA in only one part of the embryo clearly suggests that the mRNA is either moved or selectively degraded or stabilized. Localized stabilization was first demonstrated for the posteriorly localized hsp83 mRNA, and it now appears that the same mechanism may contribute to the localization of other maternal mRNAs at the posterior pole of the embryo (6). The action of differential mRNA stability in mRNA localization raises the question of whether mRNA instability may also act in bcd mRNA localization. Although we cannot exclude a minor contribution of such a mechanism to localization of the bcd mRNA, we have found no supporting evidence. Mutations in either the complete bcd 3′ UTR or the isolated IV/V RNA that interfere with localization typically have no measurable effect on stability (Fig. 3) (28). The only possible exception is the destabilized LS15 mutant, for which localization cannot be monitored. Despite the apparent differences in the roles for instability, it is possible that the same machinery may be used. Bashirullah and coworkers (6) have narrowly mapped the hsp83 mRNA protection element to a 106-nt segment of the 3′ UTR, and we have compared this to the segment of bcd mRNA that, on the basis of the LS15 phenotype, includes a stability element. We can find no strong similarities in either primary sequence or predicted secondary structure, but the uncertainties surrounding the nature of the BSF binding site make it difficult to draw any conclusions about a later role for BSF in RNA stabilization during embryogenesis. Nevertheless, BSF is present throughout embryogenesis (data not shown), and thus its function is probably not limited to stabilization of maternal mRNAs, independent of which maternal mRNAs it regulates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant GM42612 from the National Institutes of Health to P.M.M.

We thank members of the Macdonald lab for helpful discussions, Karen Kerr and Yemane Geddes for technical assistance, Amy Beaton of the BDGP for P element insertion stock l(2)k07109, the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks, and Tim Stearns for monoclonal anti-tubulin antibody. Mike Simon graciously provided lab space at a critical juncture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M D, Celniker S E, Holt R A, Evans C A, Gocayne J D, Amanatides P G, Scherer S E, Li P W, Hoskins R A, Galle R F, George R A, Lewis S E, Richards S, Ashburner M, Henderson S N, Sutton G G, Wortman J R, Yandell M D, Zhang Q, Chen L X, Brandon R C, Rogers Y H, Blazej R G, Champe M, Pfeiffer B D, Wan K H, Doyle C, Baxter E G, Helt G, Nelson C R, Gabor Miklos G L, Abril J F, Agbayani A, An H J, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Baldwin D, Ballew R M, Basu A, Baxendale J, Bayraktaroglu L, Beasley E M, Beeson K Y, Benos P V, Berman B P, Bhandari D, Bolshakov S, Borkova D, Botchan M R, Bouck J, Brokstein P, Brottier P, Burtis K C, Busam D A, Butler H, Cadieu E, Center A, Chandra I, Cherry J M, Cawley S, Dahlke C, Davenport L B, Davies P, de Pablos B, Delcher A, Deng Z, Mays A D, Dew I, Dietz S M, Dodson K, Doup L E, Downes M, Dugan-Rocha S, Dunkov B C, Dunn P, Durbin K J, Evangelista C C, Ferraz C, Ferriera S, Fleischmann W, Fosler C, Gabrielian A E, Garg N S, Gelbart W M, Glasser K, Glodek A, Gong F, Gorrell J H, Gu Z, Guan P, Harris M, Harris N L, Harvey D, Heiman T J, Hernandez J R, Houck J, Hostin D, Houston K A, Howland T J, Wei M H, Ibegwam C, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnott D, Henzel W J, Stults J T. Rapid identification of comigrating gel-isolated proteins by ion trap-mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:968–980. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnott D, O'Connell K L, King K L, Stults J T. An integrated approach to proteome analysis: identification of proteins associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Anal Biochem. 1998;258:1–18. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkan A, Walker M, Nolasco M, Johnson D. A nuclear mutation in maize blocks the processing and translation of several chloroplast mRNAs and provides evidence for the differential translation of alternative mRNA forms. EMBO J. 1994;13:3170–3181. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bashirullah A, Cooperstock R L, Lipshitz H D. RNA localization in development. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:335–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bashirullah A, Halsell S R, Cooperstock R L, Kloc M, Karaiskakis A, Fisher W W, Fu W, Hamilton J K, Etkin L D, Lipshitz H D. Joint action of two RNA degradation pathways controls the timing of maternal transcript elimination at the midblastula transition in Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1999;18:2610–2620. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binder R, Horowitz J A, Basilion J P, Koeller D M, Klausner R D, Harford J B. Evidence that the pathway of transferrin receptor mRNA degradation involves an endonucleolytic cleavage within the 3′ UTR and does not involve poly(A) tail shortening. EMBO J. 1994;13:1969–1980. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. The bicoid protein determines position in the Drosophila embryo in a concentration-dependent manner. Cell. 1988;54:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. A gradient of bicoid protein in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 1988;54:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driever W, Siegel V, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Autonomous determination of anterior structures in the early Drosophila embryo by the bicoid morphogen. Development. 1990;109:811–820. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edgar B A, Weir M P, Schubiger G, Kornberg T. Repression and turnover pattern fushi tarzu RNA in the early Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1986;47:747–754. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90517-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrandon D, Elphick L, Nüsslein-Volhard C, St. Johnston D. Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell. 1994;79:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrandon D, Koch I, Westhof E, Nüsslein-Volhard C. RNA-RNA interaction is required for the formation of specific bicoid mRNA 3′ UTR-STAUFEN ribonucleoprotein particles. EMBO J. 1997;16:1751–1758. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisk D G, Walker M B, Barkan A. Molecular cloning of the maize gene crp1 reveals similarity between regulators of mitochondrial and chloroplast gene expression. EMBO J. 1999;18:2621–2630. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunkel N, Yano T, Markussen F H, Olsen L C, Ephrussi A. Localization-dependent translation requires a functional interaction between the 5′ and 3′ ends of oskar mRNA. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1652–1664. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henzel W J, Billeci T M, Stults J T, Wong S C, Grimley C, Watanabe C. Identifying proteins from two-dimensional gels by molecular mass searching of peptide fragments in protein sequence databases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5011–5015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim-Ha J, Kerr K, Macdonald P M. Translational regulation of oskar mRNA by bruno, an ovarian RNA-binding protein, is essential. Cell. 1995;81:403–412. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krutzsch H C, Inman J K. N-isopropyliodoacetamide in the reduction and alkylation of proteins: use in microsequence analysis. Anal Biochem. 1993;209:109–116. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai E C, Burks C, Posakony J W. The K box, a conserved 3′ UTR sequence motif, negatively regulates accumulation of enhancer of split complex transcripts. Development. 1998;125:4077–4088. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai E C, Posakony J W. The Bearded box, a novel 3′ UTR sequence motif, mediates negative post-transcriptional regulation of Bearded and Enhancer of split complex gene expression. Development. 1997;124:4847–4856. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lie Y S, Macdonald P M. Apontic binds the translational repressor Bruno and is implicated in regulation of oskar mRNA translation. Development. 1999;126:1129–1138. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipshitz H D, Smibert C A. Mechanisms of RNA localization and translational regulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:476–488. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lui M, Tempst P, Erdjument-Bromage H. Methodical analysis of protein-nitrocellulose interactions to design a refined digestion protocol. Anal Biochem. 1996;241:156–166. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macdonald P M. bicoid mRNA localization signal: phylogenetic conservation of function and RNA secondary structure. Development. 1990;110:161–171. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macdonald P M, Ingham P, Struhl G. Isolation, structure and expression of even-skipped: a second pair-rule gene of Drosophila containing a homeo box. Cell. 1986;47:721–734. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macdonald P M, Kerr K. Mutational analysis of an RNA recognition element that mediates localization of bicoid mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3788–3795. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macdonald P M, Kerr K. Redundant RNA recognition events in bicoid mRNA localization. RNA. 1997;3:1413–1420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macdonald P M, Kerr K, Smith J L, Leask A. RNA regulatory element BLE1 directs the early steps of bicoid mRNA localization. Development. 1993;118:1233–1243. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macdonald P M, Leask A, Kerr K. exl protein specifically binds BLE1, a bicoid mRNA localization element, and is required for one phase of its activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10787–10791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macdonald P M, Struhl G. cis-acting sequences responsible for anterior localization of bicoid mRNA in Drosophila embryos. Nature. 1988;336:595–598. doi: 10.1038/336595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manthey G M, McEwen J E. The product of the nuclear gene PET309 is required for translation of mature mRNA and stability or production of intron-containing RNAs derived from the mitochondrial COX1 locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:4031–4043. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sallés F J, Lieberfarb M E, Wreden C, Gergen J P, Strickland S. Coordinate initiation of Drosophila development by regulated polyadenylation of maternal messenger RNAs. Science. 1994;266:1996–1999. doi: 10.1126/science.7801127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Small I D, Peeters N. The PPR motif—a TPR-related motif prevalent in plant organellar proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:46–47. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smibert C A, Wilson J E, Kerr K, Macdonald P M. smaug protein represses translation of unlocalized nanos mRNA in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2600–2609. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spradling A C, Stern D, Beaton A, Rhem E J, Laverty T, Mozden N, Misra S, Rubin G M. The Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project gene disruption project: single P-element insertions mutating 25% of vital Drosophila genes. Genetics. 1999;153:135–177. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephenson E C, Chao Y, Fackenthal J D. Molecular analysis of the swallow gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1655–1665. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.St. Johnston D, Driever W, Berleth T, Richstein S, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Multiple steps in the localization of bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 1989;107(Suppl.):13–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.Supplement.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Surdej P, Jacobs-Lorena M. Developmental regulation of bicoid mRNA stability is mediated by the first 43 nucleotides of the 3′ untranslated region. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2892–2900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss I M, Liebhaber S A. Erythroid cell-specific mRNA stability elements in the α2-globin 3′ nontranslated region. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2457–2465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wickens M, Goodwin E B, Kimble J, Strickland S, Hentze M. Translational control of developmental decisions. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, editors. Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. pp. 295–370. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zinn K, DiMaio D, Maniatis T. Identification of two distinct regulatory regions adjacent to the human b-interferon gene. Cell. 1983;34:865–879. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]