Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, extracellular vesicles, lung development

Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are secreted lipid-enclosed particles that have emerged as potential biomarkers and therapeutic agents in lung disease, including bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a leading complication of preterm birth. Many unanswered questions remain about the content and cargo of EVs in premature infants and their role in lung development. To characterize EVs during human lung development, tracheal aspirates were collected from premature neonates between 22 and 35 wk gestational age and analyzed via nanoparticle tracking analysis, electron microscopy, and bead-based flow cytometry. EVs were detectable across late canalicular through saccular stages of lung development, demonstrating larger sizes earlier in gestation. EVs contained an abundance of the EV-enriched tetraspanins CD9, CD63, and CD81, as well as epithelial cell and immune cell markers. Increases in select surface proteins (CD24 and CD14) on EVs were associated with gestational age and with the risk of BPD. Finally, query of expression data obtained from epithelial cells in a single-cell atlas of murine lung development found that epithelial EV marker expression also changes with developmental time. Together, these data demonstrate an association between EV profile and lung development and provide a foundation for future functional classification of EVs, with the goal of determining their role in cell signaling during development and harnessing their potential as a new therapeutic target in BPD.

INTRODUCTION

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among premature infants, with 75% of those born between 22 and 24 wk gestational age (GA) developing BPD (1). Despite advances that have improved survival in premature infants, the incidence of BPD has increased in recent years (1). Although the environmental exposures resulting in BPD, such as hyperoxia, inflammation, and mechanical stretch, are well described, the precise molecular mechanisms that lead to impaired alveolarization and vascular hypoplasia is an area of active investigation (2, 3). There exist significant knowledge gaps regarding how cells in the lung communicate during normal lung development and in the setting of injury after preterm birth (4–6).

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are one route of likely intercellular communication during lung development. EVs are membrane-bound particles ranging from ∼50 nm to 1 µm in size that originate from the endosomal or plasma membrane (7). EVs have been identified as important mediators of cellular communication and vehicles for the transfer of molecular contents including nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids (8). EVs have been isolated from various biological fluids and have been studied in many organs, including the lung (9); however, how EV characteristics evolve over the course of normal lung development remains unknown. Because proper lung development requires tremendous cellular and structural changes, it is possible that EVs are both markers and mediators of these dynamic processes. Given the rising interest in the use of EVs made by stromal cells as a potential therapy for BPD (10, 11), it is essential to determine the function of endogenous lung EVs. To understand the relationship between EVs and lung development, we isolated EVs from tracheal aspirates from infants born between 22 and 35 wk gestation, describing the morphology and characteristics of EVs throughout the late canalicular and saccular stages of lung development.

METHODS

Study Population

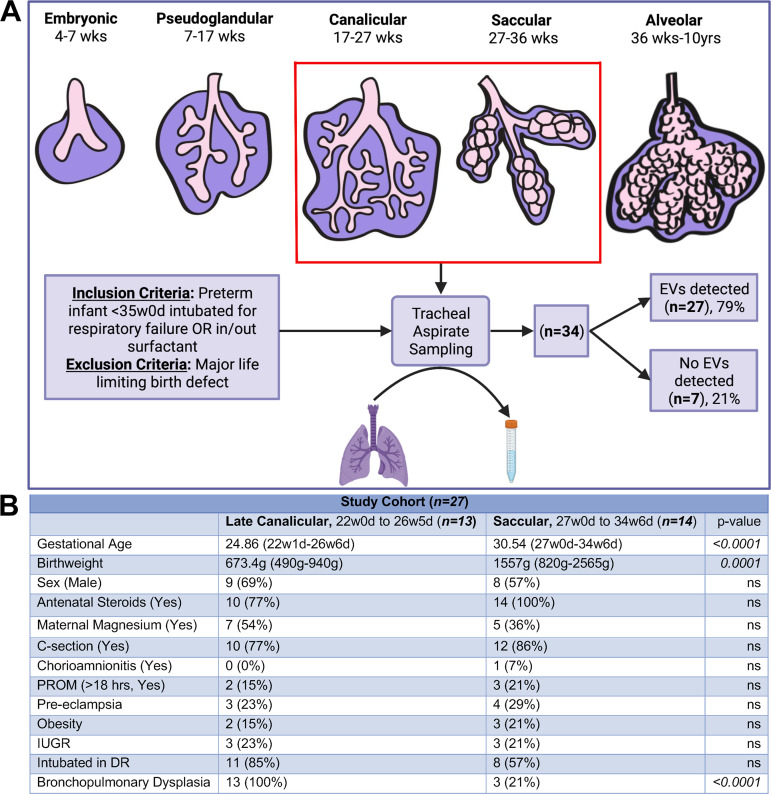

Tracheal aspirates (TAs) were collected from neonates admitted to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Mildred Stahlman Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Inclusion criteria included prematurity less than or equal to 35 wk gestation, with TAs being collected as part of routine standard of care (i.e., intubation for respiratory failure and intubation for surfactant administration). Exclusion criteria included presence of a major life-limiting birth defect (Fig. 1A). This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

A: schematic of study design with details of patient enrollment and sample collection. B: demographic information for study patients stratified into two groups: late canalicular stage (22w0d to 26w5d, n = 13) and saccular stage (27w0d to 34w6d, n = 14); statistical analysis by Fisher’s exact test. d, days; DR, delivery room; EVs, extracellular vesicles; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; ns, nonsignificant; PROM, premature rupture of membranes; w, weeks. [Image created with BioRender.com and published with permission.]

Tracheal Aspirate Sample Collection and Processing

Tracheal aspirate (TA) collection was performed by a licensed respiratory therapist as a part of routine care, with 0.5 mL of normal saline instilled into the endotracheal (ET) tube via the side port in the Ballard suction device. The suction catheter was advanced to just below the tip of the ET tube, and the saline was aspirated into a sputum trap connected to the Ballard suction device. After TAs were collected, they were processed by centrifugation to remove cells at 500 g for 10 min at 4°C. Then, centrifugation at 2,000 g for 20 min at 4°C was performed to remove cellular debris. Supernatants were stored at −80°C in aliquots (Fig. 1A).

Visualization and Quantification of Tracheal Aspirate-Derived Extracellular Vesicles among Premature Neonates

To isolate EVs for electron microscopy (EM), 150 µL of sample per subject was purified using size-exclusion chromatography with the qEVsingle (Izon) 70-nm column and then concentrated on a 100-kDa spin filter (Amicon). EVs were then adhered to freshly glow-discharged, 300-mesh carbon-coated grids for 10 s, followed by two brief washes in ddH2O and stained with 2% uranyl acetate. Transmission electron microscopy was performed with a Tecnai T12 that operates at 100 keV using an AMT NanoSprint CMOS camera. Diluted TA samples were analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) with a ZetaView (Particle Metrix). Concentration and particle size were determined within the optimal particle per frame value of 200–300 particles/frame. Then, 100-nm beads were used to calibrate the instrument for small particle detection, and PBS washes were performed until <10 particles/frame were detected between samples. Visualization and quantitation of particles were performed as per guidelines set forth by the International Society of Extracellular Vesicles (12).

Bead-Based Flow Cytometry Analysis

For each sample, 35 µL of TA was incubated with the MACSPlex Exosome (Miltenyi) kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by flow cytometry on a FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences). This kit contains 37 different bead populations, each bound to a unique antibody, and provides a sensitive and reproducible semiquantitative methodology to detect EVs in various biofluids (13). For each run, purified plasma EVs were included as a positive control and PBS was included as a negative control for EV detection in parallel with samples. In addition, the bead array contains two bead-capture isotype controls [Recombinant Engineered Antibody (REA) and mIgG1] to test for nonspecific bead binding within each biospecimen tested. The EVs were detected using a cocktail of antibodies labeled with allophycocyanin (APC) against the tetraspanin membrane proteins CD9 and CD63. APC fluorescence intensity in molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome (MESF) was assigned using the Quantum APC MESF kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the QuickCal v. 3.0 analysis template to calculate a calibration curve that allowed the association of APC fluorescence values with MESF units (Bangs Laboratories) to control for variations in flow cytometer fluorescence detection between runs. FlowJo software was used to process the data, and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software version 9.2.0. P values are provided from Mann–Whitney tests without adjustment, and statistical tests performed are detailed within figure legends.

Application to a Single-Cell Atlas of Lung Development

We analyzed data from a recently completed single-cell transcriptomic atlas of mouse lung development from E12, E15, E16, E18, P0, P3, P5, P7, P14, and P64 from the pseudoglandular through the alveolar stages. These data (NCBI GEO Accession Nos. GSE165063 and GSE160876) were analyzed as described previously (14). We queried the expression data obtained to characterize EV markers detected throughout lung development.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

TA samples were collected from 34 patients with gestational ages ranging from 22w1d to 34w6d (Fig. 1A). Twenty-seven samples contained detectable EVs. The seven samples that did not contain detectable EVs were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1A). Patients were divided into two groups: late canalicular (defined as GA of 22w0d to 26w6d) and saccular (defined as 27w0d to 34w6d; Fig. 1B). The average GA in the late canalicular stage group was 24.86 (range: 22w1d to 26w6d), and the average GA in the saccular stage group was 30.54 (range: 27w0d to 34w6d). As expected, the average birthweight was lower in the late canalicular versus the saccular stage group, that is, 673.4 g (490–940 g) versus 1,557 g (820–2,565 g; P = 0.001). All neonates in the late canalicular group went on to develop BPD, whereas 3 of 14 (21%) neonates developed BPD in the saccular group (P = <0.001). There were no statistically significant differences observed between these two groups for the remaining demographic variables collected (Fig. 1B), and the birthweights of the saccular stage infants who developed BPD ranged between 820 and 1,070 g.

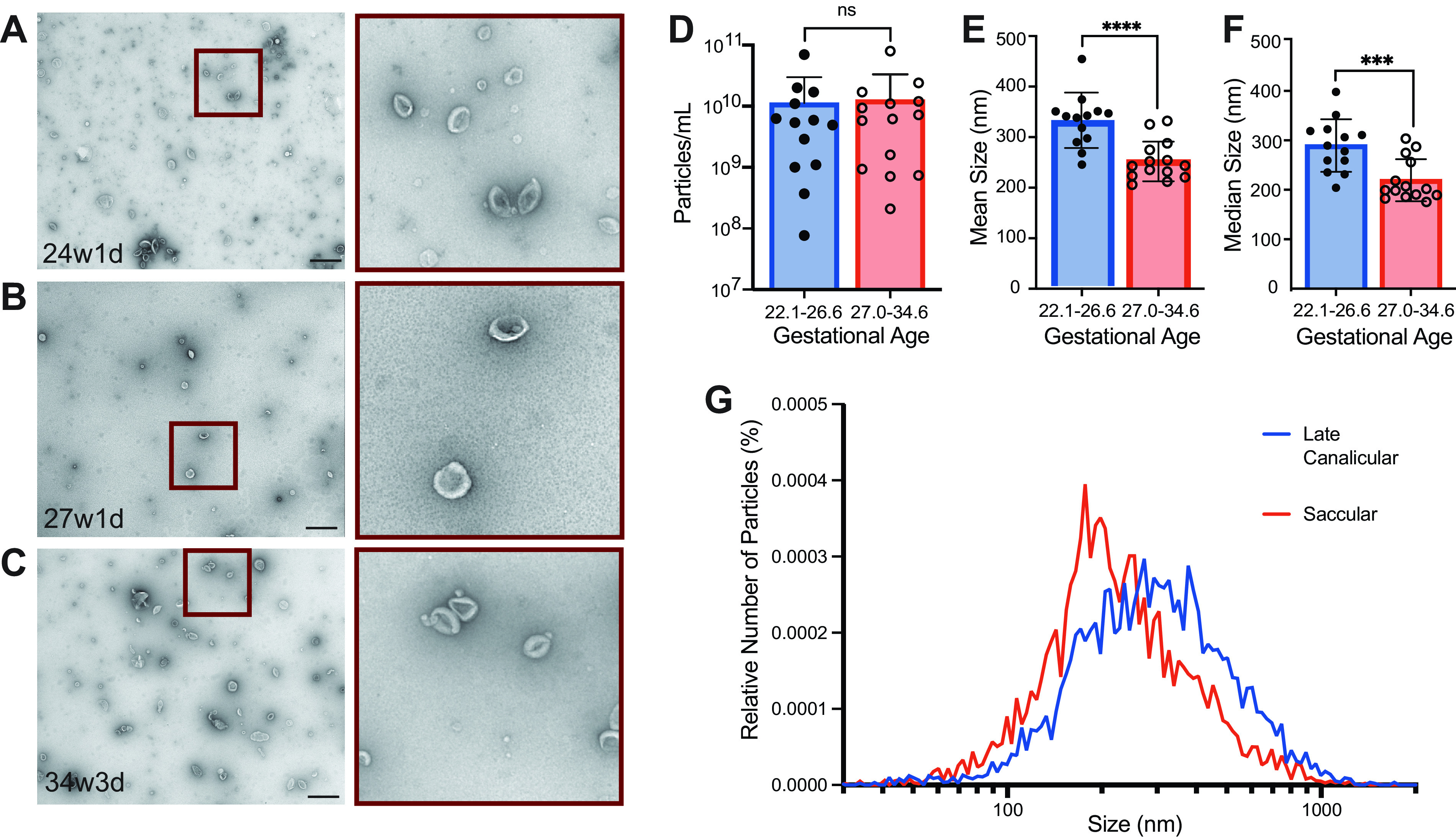

Extracellular Vesicles Are Abundant in Tracheal Aspirates across Gestational Ages

Three samples from different gestational ages (24w1d, 27w1d, 34w3d) were processed for electron microscopy (EM) to assess for the presence and morphology of EVs in TA samples. EVs of varying sizes were detected and demonstrated a classic cup-shaped morphology in all three samples (Fig. 2, A–C). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was performed on all samples to determine EV concentration and diameter. Among infants with detectable EVs, no difference was observed in the relative concentration of particles detected in the late canalicular stage and the saccular stage of lung development (Fig. 2D). However, infants in the late canalicular stage had larger mean and median diameter of EVs compared with infants in the saccular stage (Fig. 2, E and F). This represented a shift in the distribution of particle sizes when averaged across all samples (Fig. 2G).

Figure 2.

Tracheal aspirates were purified using size-exclusion chromatography and then visualized using electron microscopy from three samples. A: patient at 24w1d gestational age. B: patient at 27w1d gestational age. C: patient at 34w3d gestational age (Scale bar = 600 nm, n = 1 at each gestational age). Tracheal aspirates were analyzed using nanoparticle tracking analysis to determine particle concentration (D) and size (E and F). Samples were divided between the late canalicular and the early saccular stage of lung development. Mann–Whitney test was performed (****P ≤ 0.0001, ***P ≤ 0.001, n = 13, 22w1d-26w2d gestational age and n = 14, 27w0d-34w6d gestational age). G: size distribution of EVs by relative number of particles expressed as a percentage of total particles averaged across all samples from this analysis. d, days; EVs, extracellular vesicles; w, weeks.

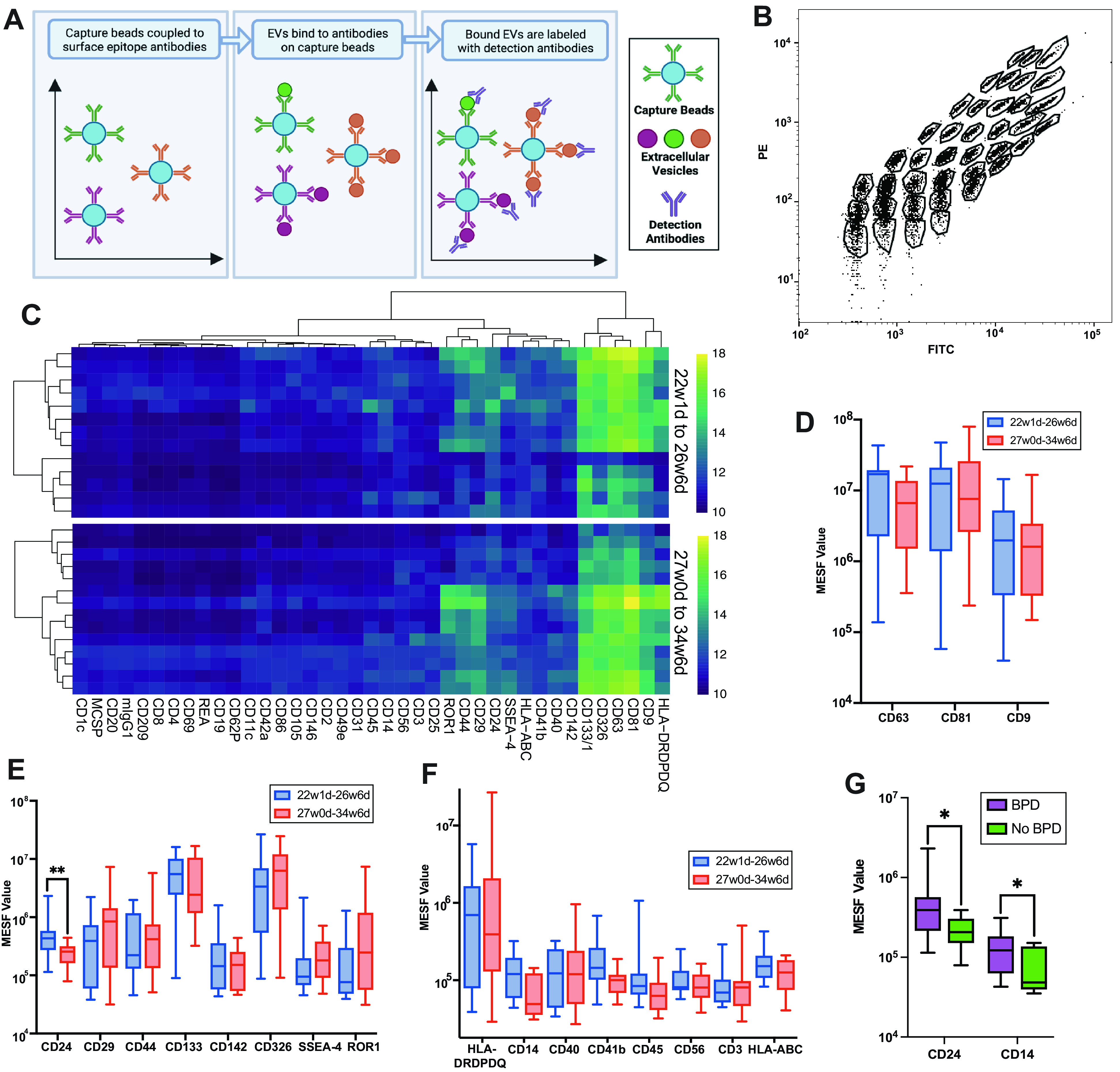

Extracellular Vesicles Carrying Epithelial and Immune Proteins Are Present across the Stages of Lung Development

To assay populations of lung EVs in collected TAs, we used a bead-based flow cytometry array (Fig. 3, A and B). Most samples had robustly detectable EVs; however, 7 out of 34 patients had a mean EV detection signal less than two standard deviations above the PBS control and were eliminated from the analysis (data not shown). The small number of samples with low EV recovery were from infants who ranged in gestational age from 26w2d to 32w4d with birthweights of 740–1,785 g, with no notable differences from the other samples, suggesting a stochastic technical issue. An unsupervised hierarchical clustering of all markers by group was then performed by calculating the Euclidean distance and using complete linkage for clustering (Fig. 3C). This analysis revealed an abundance of the EV-enriched tetraspanins CD9, CD63, and CD81 in TAs across gestational ages. TAs also had particularly high levels of EVs carrying two epithelial markers, CD326 (EPCAM) and CD133 (PROM1), consistent with the detection of abundant EVs derived from epithelial cells. Additional epithelial markers detected were CD142 and ROR1. EVs recovered from TAs from preterm infants also carried markers that can be found in other cell lineages, as well as epithelial cells, such as CD24, CD29, CD44, and SSEA-4. We also detected markers expressed by immune cells, including CD3, CD14, CD40, CD41b, CD45, CD56, HLA-ABC, and HLA-DRDPDQ (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

A: schematic demonstrating the EV bead-capture assay. B: example flow cytometry plot of the 39 unique bead populations representing the 37 surface epitopes plus two isotype controls. C: unsupervised hierarchal clustering of the data was performed for each group of samples. Quantification of EV markers CD9, CD63, and CD81 (D) and abundant epithelial cell-expressed (E) and immune cell-expressed (F) markers on bead-captured EVs between groups. G: levels of CD24 and CD14 in EVs among patients who went on to develop BPD. Mann–Whitney test was performed (**P ≤ 0.01, *P ≤ 0.05, n = 13, 22w1d-26w2d gestational age and n = 14, 27w0d-34w6d gestational age; n = 16 BPD and n = 11 no BPD). BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; d, days; EV, extracellular vesicle; MESF, molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome; PE, phycoerythrin; w, weeks.

After stratifying the samples between the late canalicular and the saccular stage of lung development by gestational age, a Mann–Whitney test was performed for each pair of markers. No differences in detection of the EV-enriched tetraspanins CD9, CD63, and CD81 were found (Fig. 3D). However, we identified higher levels of CD24+ EVs in samples from the late canalicular versus the saccular stage (P = 0.0095; Fig. 3E). We detected no statistically significant difference between immune-specific markers but found detectable modest increases in CD14+ EVs in the late canalicular versus the saccular stage (P = 0.0664; Fig. 3F). Among infants who went on to develop BPD, higher levels of CD24+ (P = 0.0186) and CD14+ (P = 0.0372) EVs were detected, compared with infants who did not develop BPD (Fig. 3G).

Application of an Epithelial Single-Cell Atlas to Extracellular Vesicle Cargos Detected in Lung Development

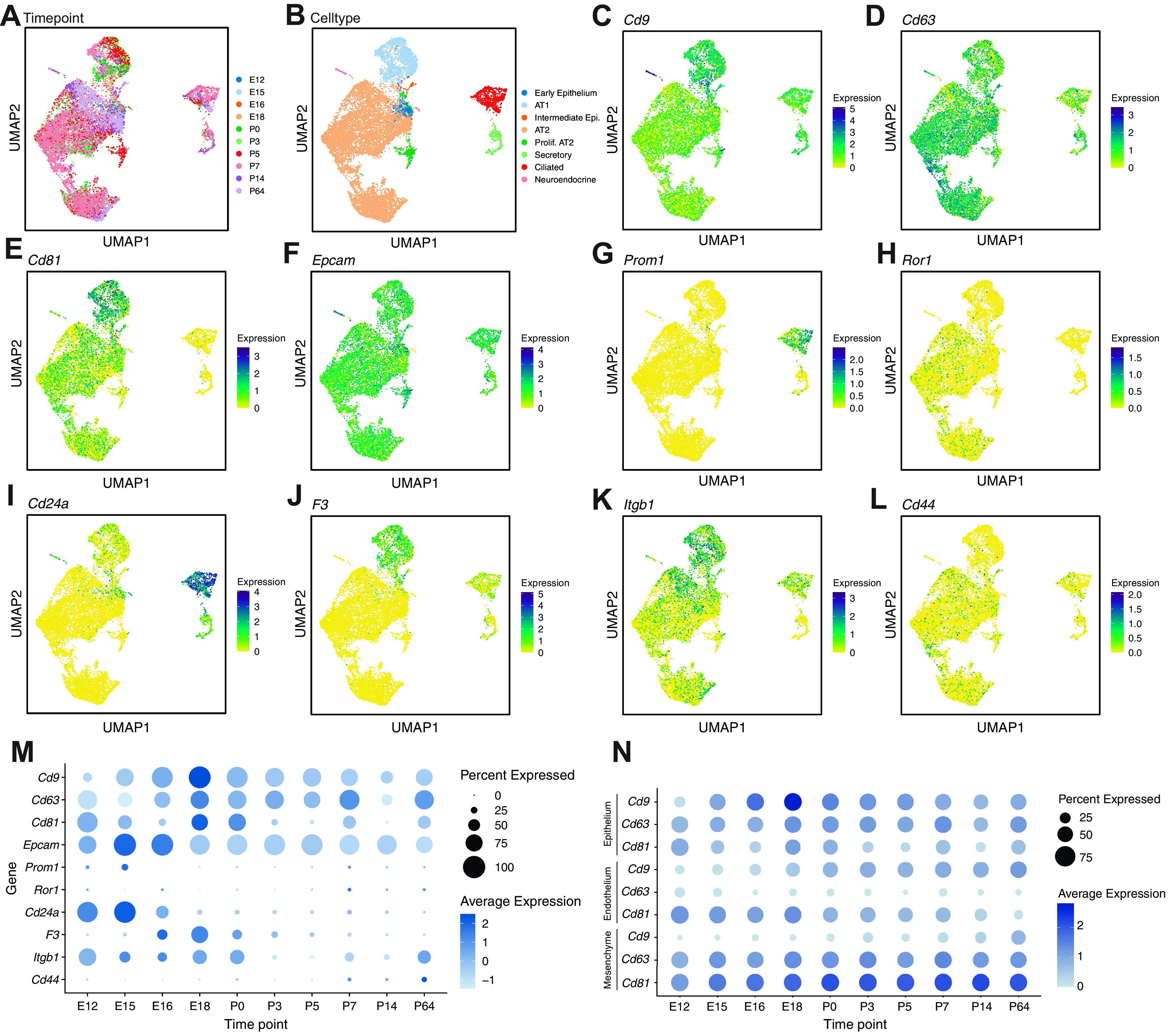

Analysis of single-cell RNA transcriptomes from >10,000 mouse lung epithelial cells across developmental time was used to characterize hallmark gene expression of markers detected on TA EVs (Fig. 4, A and B). We queried this atlas for gene expression for the markers from the bead-capture assay (Fig. 4, C–L). We identified widespread expression of EV-enriched tetraspanins Cd9, Cd63, and Cd81 across cell types in the late canalicular (mouse embryonic days 16–17) and saccular (mouse embryonic day 18 to postnatal day 4) stages, with relatively higher expression of Cd9 and Cd81 in alveolar type 1 pneumocytes (AT1) and Cd63 in alveolar type 2 pneumocytes (AT2). Gene expression of Epcam (Cd326) and Prom1 (Cd133), the two most abundantly detected epithelial markers on EVs in TA samples from preterm infants, showed peak expression levels in the canalicular stage in mice. Epcam (Cd326) was expressed broadly in all cell types, whereas Prom1 (Cd133) was mostly found in ciliated epithelium. Across all epithelial cells, expression of CD24a was significantly higher in the late canalicular versus the saccular stage mice (Fig. 4M), mirroring the levels of CD24+ EVs in preterm infants (Fig. 3E). Interrogation of the major parenchymal cell populations from the full atlas of >100,000 cells demonstrates differential expression of Cd9, Cd63, and Cd81, over time, with each subpopulation of cells having a different trajectory (Fig. 4N).

Figure 4.

A single-cell transcriptomic atlas demonstrates differential expression of EV markers across developmental time (n = at least 4 mice pooled at each timepoint). A: UMAP embedding colored by timepoint from E12 to P64. B: UMAP embedding of all epithelial cells that clustered, annotated by cell type. C–E: UMAP embedding of epithelial cells colored by EV-enriched tetraspanins (Cd9, Cd63, and Cd81, respectively). Darker colors indicate greater expression. F–L: UMAP embedding of epithelial cells colored by epithelial expression of Epcam (CD326), Prom1 (CD3133), Ror1, CD24a (CD24), F3 (CD142), Itgb1 (CD29), and Cd44, respectively. Darker colors indicate greater expression. M: hallmark gene expression in epithelial cells plotted across developmental time from prenatal timepoints through adulthood, with dot size indicating proportion of cells within a cluster expressing that gene and color saturation indicating relative expression level. N: expression of EV tetraspanins Cd9, Cd63, and Cd81 in epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and mesenchymal cells across the developmental time from prenatal time points through adulthood. EV, extracellular vesicle; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that EVs can be reliably detected in tracheal aspirate fluid among premature neonates as early as 22 wk gestation by both EM and a bead-based flow cytometry assay using CD9 and CD63 to identify EVs. We found an increased EV size and level of CD24 in EVs in preterm infants born in the late canalicular versus the saccular stage of lung development. This study adds to important prior research showing differences in EVs and their cargo miRNAs from tracheal aspirates and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids in infants with and without BPD (15–17). Ultimately, work in this area will be essential to understand how EVs participate in cellular communication and developmental transitions required for organogenesis and disease pathogenesis. In addition, abundant levels of EV marker gene expression in epithelial cells are noted across analogous stages in mouse lung development, allowing the possibility that EV production during this developmental window is conserved between humans and mice.

Given what is known about lung development and BPD, it is interesting to hypothesize how EVs carrying the markers identified in this study might participate in normal physiological and pathological processes. In both the late canalicular and the saccular stage of lung development, the most abundant epithelial expressed proteins in EVs included CD133, CD326, CD142, CD24, and ROR1, and this is consistent with genetic tracing strategies detecting abundant epithelial EVs in mouse lung fluids (18). Future studies are needed to address whether EVs from other populations of cells important for lung development and BPD, such as mesenchymal cells, may also produce unique populations of EVs during this critical developmental window. Within the transcriptomic atlas of the developing lung, expression of EV-enriched tetraspanins Cd9, Cd81, and Cd63 was detected in proximal airway cells and distal alveolar type 1 and type 2 pneumocytes, with Cd9 being especially enriched in alveolar type 1 cells. Although these EV markers were also expressed in the mesenchyme and endothelium, given that these samples were obtained by aspiration from the epithelium-lined airspace and that the most abundant detected markers were CD326 and CD133, we speculate that the bulk of the EVs detected in TAs is derived from epithelial cells. Indeed, it is possible that the EVs obtained in the human TAs present an opportunity for a liquid biopsy of the entire respiratory tree, including the distal growing alveoli, which are just beginning to form during this developmental window.

Our identification of CD24a as being increased in early lung development and the correlation with detection of higher levels of CD24+ EVs in BPD raise the possibility that CD24+ EVs are functionally important in the developing lung. In the adult human, CD24 is abundantly expressed in bronchial respiratory and alveolar epithelium as well as lung macrophages (19) and has been shown to inhibit the NF-κB pathway (20, 21). The NF-κB family of transcription factors are important regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation, inflammation, and angiogenesis, playing key roles in how the lung reacts to injury and alveolar development (22). Whereas excessive NF-κB signaling is associated with the development of BPD (23), insufficient NF-κB is also associated with impaired alveologenesis (24). Ultimately, CD24 on EVs may even have a therapeutic potential to promote lung repair, as CD24-loaded EVs are being tested in viral-induced hyperinflammation and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) as targeted therapy in COVID-19 (25).

Among the infants who went on to develop BPD, we observed significant increased detection of CD14+ EVs independent of the stage of lung development at the time of birth, without a generalized increase in all immune markers in the panel. Inflammation is a notable component of BPD in human patients and animal models (26). Indeed, in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), another form of acute lung injury, CD14+ EVs have recently been identified as a potential biomarker for disease severity and mortality (27). Notably, our samples were obtained within the first 24 h of birth, suggesting that early increased CD14+ EVs have a potential role as an early predictor and mediator of BPD risk.

Our understanding of the mechanism whereby EVs function in intercellular signaling within the normal developing and preterm lung remains elusive. This analysis of a set of surface markers provides clues as to possible cell-signaling pathways that may be mediated by EVs. For example, ROR1, which belongs to the Wnt family of receptors (28), was detected on the surface of EVs across samples. Notably, Wnt signaling is essential for normal alveologenesis (29), with dysregulated Wnt signaling playing a role in the fibroblast activation associated with BPD and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (30, 31). In addition, secreted Wnt ligands are carried on the surface of EVs (32). Although additional work is needed to delineate the full spectrum of Wnt mediators carried by EVs, the possible interaction of Wnt ligands and receptors on secreted EVs could be a mechanism for modulation and titration of the Wnt gradient required for the saccular to alveolar transition.

This study has several notable limitations that are not unique to human studies, including that not all samples obtained contained detectable levels of EVs. We speculate that this is due to the technical limitations in suctioning techniques in small infants; however, we do show that EVs are detectable in the majority of samples down to 22 wk gestation. In addition, our bead-based assay does not represent a comprehensive investigation of all possible surface proteins on and subpopulations of EVs, and future work to expand this assay to include markers of other cells in the alveolus and airway as well as signaling ligands will be important as we further refine our characterization of the EV profile in preterm infants. Despite these limitations, this study defines the characteristics of EVs during this critical window in lung development and provides foundational data for future studies.

In summary, we report a developmental trajectory of relative enrichment of CD24+ EVs and an association of early increased levels of CD24+ and CD14+ EVs with development of BPD. This work provides a foundation for future directions to elucidate the role of EVs in lung development and injury, including determination of the cell source of EVs throughout the stages of lung development and mechanisms of EV biological function, with the overall goal of identifying a potential therapeutic agent for restoring lung development in premature neonates.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by NIH T32 GM007569 (M.S.R.), American Academy of Pediatrics Marshall Klaus Perinatal Research Award (M.S.R.), NIH DP2HL152426 (H.H.P.), NIH K08143051 (J.M.S.S.), The Francis Family Foundation (J.M.S.S.), NIH T32GM008554 (K.E.B.), NIH T32HL094296 (N.M.M.), and The John and Leslie Hooper Neonatal-Perinatal Endowment Fund (M.S.R.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.A.R., J.M.S.S., and H.H.P. conceived and designed research; M.A.R., K.E.B., N.M.N., C.S.J., and Z.J.B. performed experiments; M.A.R. analyzed data; M.A.R., J.M.S.S., and H.H.P. interpreted results of experiments; M.A.R. and N.M.N. prepared figures; M.A.R. drafted manuscript; M.A.R., N.M.N., J.M.S.S., and H.H.P. edited and revised manuscript; M.A.R., K.E.B., N.M.N., C.S.J., Z.J.B., J.M.S.S., and H.H.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Experiments were performed in part using the Vanderbilt University Cell Imaging Shared Resource (supported by NIH Grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, and DK5963). Pilot work for this project was supported by a voucher from the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR, UL1TR002243). ZetaView (Particle Metrix) used is provided as shared equipment by the Vanderbilt Center for Extracellular Vesicle Research. The Human Protein Atlas was referenced for this work at proteinatlas.org. Figure 1A and graphical abstract image were created with BioRender.com and published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Stark AR, Bauer CR, Donovan EF, Korones SB, Laptook AR, Lemons JA, Oh W, Papile LA, Shankaran S, Stevenson DK, Tyson JE, Poole WK; NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196: 147.e1–8, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jobe AH. Mechanisms of lung injury and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Perinatol 33: 1076–1078, 2016. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Popova AP. Mechanisms of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Cell Commun Signal 7: 119–127, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s12079-013-0190-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warburton D, El-Hashash A, Carraro G, Tiozzo C, Sala F, Rogers O, Langhe SD, Kemp PJ, Riccardi D, Torday J, Bellusci S, Shi W, Lubkin SR, Jesudason E. Lung organogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol 90: 73–158, 2010. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)90003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bäckström E, Hogmalm A, Lappalainen U, Bry K. Developmental stage is a major determinant of lung injury in a murine model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Res 69: 312–318, 2011. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31820bcb2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Surate Solaligue DE, Rodríguez-Castillo JA, Ahlbrecht K, Morty RE. Recent advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of late lung development and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 313: L1101–L1153, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00343.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Niel G, D'Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19: 213–228, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 200: 373–383, 2013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berumen Sánchez G, Bunn KE, Pua HH, Rafat M. Extracellular vesicles: mediators of intercellular communication in tissue injury and disease. Cell Commun Signal 19: 104, 2021. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00787-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Willis GR, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Anastas J, Vitali SH, Liu X, Ericsson M, Kwong A, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S. Mesenchymal stromal cell exosomes ameliorate experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia and restore lung function through macrophage immunomodulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197: 104–116, 2018. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0925OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Willis GR, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Reis M, Yeung V, Liu X, Ericsson M, Andrews NA, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived small extracellular vesicles restore lung architecture and improve exercise capacity in a model of neonatal hyperoxia-induced lung injury. J Extracell Vesicles 9: 1790874, 2020. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2020.1790874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R , et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles 7: 1535750, 2018. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wiklander OPB, Bostancioglu RB, Welsh JA, Zickler AM, Murke F, Corso G, Felldin U, Hagey DW, Evertsson B, Liang XM, Gustafsson MO, Mohammad DK, Wiek C, Hanenberg H, Bremer M, Gupta D, Björnstedt M, Giebel B, Nordin JZ, Jones JC, El Andaloussi S, Görgens A. Systematic methodological evaluation of a multiplex bead-based flow cytometry assay for detection of extracellular vesicle surface signatures. Front Immunol 9: 1326, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Negretti NM, Plosa EJ, Benjamin JT, Schuler BA, Habermann AC, Jetter CS, Gulleman P, Bunn C, Hackett AN, Ransom M, Taylor CJ, Nichols D, Matlock BK, Guttentag SH, Blackwell TS, Banovich NE, Kropski JA, Sucre JMS. A single-cell atlas of mouse lung development. Dev Camb Engl 148: dev199512, 2021. doi: 10.1242/dev.199512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lal CV, Olave N, Travers C, Rezonzew G, Dolma K, Simpson A, Halloran B, Aghai Z, Das P, Sharma N, Xu X, Genschmer K, Russell D, Szul T, Yi N, Blalock JE, Gaggar A, Bhandari V, Ambalavanan N. Exosomal microRNA predicts and protects against severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely premature infants. JCI Insight 3: e93994, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siddaiah R, Oji-Mmuo CN, Montes DT, Fuentes N, Spear D, Donnelly A, Silveyra P. MicroRNA signatures associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia severity in tracheal aspirates of preterm infants. Biomedicines 9: 257, 2021. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9030257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oji-Mmuo CN, Siddaiah R, Montes DT, Pham MA, Spear D, Donnelly A, Fuentes N, Imamura-Kawasawa Y, Howrylak JA, Thomas NJ, Silveyra P. Tracheal aspirate transcriptomic and miRNA signatures of extreme premature birth with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol 41: 551–561, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-00868-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pua HH, Happ HC, Gray CJ, Mar DJ, Chiou NT, Hesse LE, Ansel KM. Increased hematopoietic extracellular RNAs and vesicles in the lung during allergic airway responses. Cell Rep 26: 933–944.e4, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347: 1260419, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y, Chen GY, Zheng P. CD24-Siglec G/10 discriminates danger- from pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Trends Immunol 30: 557–561, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barkal AA, Brewer RE, Markovic M, Kowarsky M, Barkal SA, Zaro BW, Krishnan V, Hatakeyama J, Dorigo O, Barkal LJ, Weissman IL. CD24 signalling through macrophage Siglec-10 is a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 572: 392–396, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alvira CM. Nuclear factor-kappa-B signaling in lung development and disease: one pathway, numerous functions. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 100: 202–216, 2014. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bourbia A, Cruz MA, Rozycki HJ. NF-kappaB in tracheal lavage fluid from intubated premature infants: association with inflammation, oxygen, and outcome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 91: F36–F39, 2006. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.045807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iosef C, Alastalo TP, Hou Y, Chen C, Adams ES, Lyu SC, Cornfield DN, Alvira CM. Inhibiting NF-κB in the developing lung disrupts angiogenesis and alveolarization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L1023–L1036, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00230.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shapira S, Ben Shimon M, Hay-Levi M, Shenberg G, Choshen G, Bannon L, Tepper M, Kazanov D, Seni J, Lev-Ari S, Peer M, Boubas D, Stebbing J, Tsiodras S, Arber N. A novel platform for attenuating immune hyperactivity using EXO-CD24 in COVID-19 and beyond. EMBO Mol Med 14: e15997, 2022. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202215997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a continuing story. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 11: 354–362, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mahida RY, Price J, Lugg ST, Li H, Parekh D, Scott A, Harrison P, Matthay MA, Thickett DR. CD14-positive extracellular vesicles in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid as a new biomarker of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 322: L617–L624, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00052.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Borcherding N, Kusner D, Liu GH, Zhang W. ROR1, an embryonic protein with an emerging role in cancer biology. Protein Cell 5: 496–502, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0059-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frank DB, Peng T, Zepp JA, Snitow M, Vincent TL, Penkala IJ, Cui Z, Herriges MJ, Morley MP, Zhou S, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. Emergence of a wave of Wnt signaling that regulates lung alveologenesis by controlling epithelial self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Rep 17: 2312–2325, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sucre JMS, Vickers KC, Benjamin JT, Plosa EJ, Jetter CS, Cutrone A, Ransom M, Anderson Z, Sheng Q, Fensterheim BA, Ambalavanan N, Millis B, Lee E, Zijlstra A, Königshoff M, Blackwell TS, Guttentag SH. Hyperoxia injury in the developing lung is mediated by mesenchymal expression of Wnt5A. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 201: 1249–1262, 2020. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1513OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martin-Medina A, Lehmann M, Burgy O, Hermann S, Baarsma HA, Wagner DE, De Santis MM, Ciolek F, Hofer TP, Frankenberger M, Aichler M, Lindner M, Gesierich W, Guenther A, Walch A, Coughlan C, Wolters P, Lee JS, Behr J, Königshoff M. Increased extracellular vesicles mediate WNT5A signaling in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198: 1527–1538, 2018. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1580OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gross JC, Chaudhary V, Bartscherer K, Boutros M. Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nat Cell Biol 14: 1036–1045, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ncb2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.