Keywords: basement membrane, embryogenesis, mesothelium, visceral pleura

Abstract

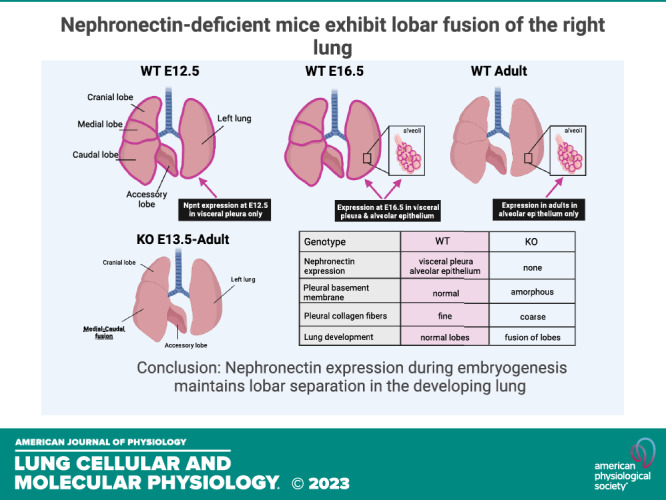

Nephronectin (NPNT) is a basement membrane (BM) protein and high-affinity ligand of integrin α8β1 that is required for kidney morphogenesis in mice. In the lung, NPNT also localizes to BMs, but its potential role in pulmonary development has not been investigated. Mice with a floxed Npnt allele were used to generate global knockouts (KOs). Staged embryos were obtained by timed matings of heterozygotes and lungs were isolated for analysis. Although primary and secondary lung bud formation was normal in KO embryos, fusion of right lung lobes, primarily the medial and caudal, was first detected at E13.5 and persisted into adulthood. The lung parenchyma of KO mice was indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) and lobe fusion did not alter respiratory mechanics in adult KO mice. Interrogation of an existing single-cell RNA-seq atlas of embryonic and adult mouse lungs identified Npnt transcripts in mesothelial cells at E12.5 and into the early postnatal period, but not in adult lungs. KO embryonic lungs exhibited increased expression of laminin α5 and deposition of collagen IV in the mesothelial BM, accompanied by abnormalities in collagen fibrils in the adjacent stroma. Cranial and accessory lobes extracted from KO embryonic lungs fused ex vivo when cultured in juxtaposition, with the area of fusion showing loss of the mesothelial marker Wilms tumor 1. Because a similar pattern of lobe fusion was previously observed in integrin α8 KO embryos, our results suggest that NPNT signaling through integrin α8, likely in the visceral pleura, maintains right lung lobe separation during embryogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Nephronectin (NPNT) is a basement membrane (BM) protein that is the key ligand for integrin α8 in mediating kidney morphogenesis in the mouse (1). NPNT expressed by epithelial cells of the ureteric bud interacts with α8β1 in the metanephric mesenchyme to promote timely branching of the bud and subsequent formation of nephrons (1, 2). Global knockouts (KOs) of either NPNT or α8 exhibit complete or partial kidney agenesis (2, 3), thus limiting the postnatal survival of these animals. NPNT has five EGF-like repeats at the amino terminus, as well as a mucin region containing the integrin recognition motif arginine-glycine aspartic acid (RGD) and a synergy site for high-affinity binding to integrin α8 (4). The protein also has a carboxy-terminal MAM (meprin-A5 protein-receptor tyrosine phosphatase µ) domain through which it interacts with heparan sulfate proteoglycans and the Fraser syndrome (FS)-associated proteins FRAS1, FREM1, and FREM2 (5, 6). A homolog of NPNT, called EGFL6 (also known as MAEG), has a similar protein structure to NPNT, with 41% overall homology, and localizes to BMs; like NPNT, EGFL6 binds integrin α8 through an RGD site, although with an affinity two orders of magnitude lower than NPNT (5). The FS-associated proteins in BMs form a ternary complex (7) that acts as a scaffold for the deposition and retention of NPNT and EGFL6 in BMs, not only in the mouse fetal kidney but also in the skin and lung (5, 6). A possible role for NPNT in lung morphogenesis has not yet been explored.

Previously, we showed that integrin α8 protein localizes diffusely to the lung mesenchyme at multiple stages in mouse development (8). With the deletion of α8, embryonic lungs had abnormal airway morphogenesis and increased mesenchymal cell migration (9). Another striking phenotype that was observed in the majority of α8 KOs is the fusion of two of the four lobes of the right lung, the medial and caudal, by day 16 in embryogenesis (9). Similarly, null or missense mutations in the FS-associated proteins in mice give rise to fused right lung lobes (10–12). Because NPNT associates with both integrin α8 and FS-associated proteins, we leveraged mice with a floxed allele of Npnt to delete NPNT and determine the effect of NPNT deletion on lung development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The strain carrying a floxed allele of Npnt (NpntFlox) in which exon 1 is flanked by loxP sites (B6;129P2-Npnttm1Lfr/Mmmh) (2) was obtained from Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center U42OD010918 and backcrossed for 10 generations onto the C57BL/6J background. The knockout allele in which exon 1 has been deleted was obtained by breeding the mice with the Pdgfrb-Cre transgenic (13) (a gift from Dr. Dean Sheppard at UCSF), which we found to have occasional germline activity, especially when the dam is Cre+. A typical breeding scheme is depicted in Supplemental Fig. S1 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21603804). We used PCR genotyping of tail biopsy genomic DNA from offspring to identify progeny that had the Npnt null allele without inheritance of Cre (assessed using primers 5′-TGCCACGACCAAGTGACAGCAATG-3′ and 5′- AGAGACGGAAATCCATCGCTC-3′). The following primers were used for genotyping the Npnt alleles: 5′- GCAACCTTCAGCGTCCC-3′ and 5′- CAGTCCATCCTGATCACTACTGGCTGTA-3′ for the floxed and WT alleles, and 5′- CAGAACGCGTACTTCCACTTCC-3′ and 5′- CAGTCCATCCTGATCACTACTGGCTGTA-3′ for the KO. Npnt+/− mice were then crossed to generate animals with global knockout of NPNT. To obtain embryonic lungs, Npnt+/− females were mated with Npnt+/− males or Npnt−/− females were mated with Npnt−/− males and checked each morning for a vaginal plug. Noon on the day a plug was detected was considered day 0.5 in gestation. Pregnant mice were euthanized by isoflurane overdose at days 11.5 through 18.5 and embryos were extracted from the uterine horns and dissected free of surrounding tissue. Adult mice were euthanized by isoflurane overdose for collection and processing of lungs. Genotyping of tissue samples was performed using the primers listed above. All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Wisconsin and the Medical University of South Carolina.

Analysis of Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

Mouse whole lung single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq data) (10× Chromium) from Zepp et al. (14) were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE149563). Seven time points (E12.5, E15.5, E17.5, P3, P7, P15, and P42) were analyzed using Partek Flow (St. Louis, MO). Briefly, cells were removed based on low detected genes (<500), high mitochondrial counts (>10%), and high ribosomal counts (>25%). Counts were normalized, filtered using principal component analysis (PCA, 100 components), and underwent dimensionality reduction using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Cell populations were identified using graphical clustering (Louvain algorithm) and expression of specific markers: epithelial (Cldn4, Sftpc, Scgb3a2), endothelial (Gpihbp, Vwf, Fabp4, Car4), mesenchymal (Wnt2, Mfap5, Hhip, Pdgfrb), erythroid (Alas2), immune (C1qa, Ccl4), and mesothelial (Wilms tumor 1, Wt1).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from homogenized lung tissue using the Aurum Total RNA Mini kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in conjunction with DNase treatment as per the manufacturer’s specifications. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using iScript Reverse Transcription SuperMix (Bio-Rad). Real-time PCR was done using an ABI OneStep Plus or Bio-Rad CFX instrument with ABI TaqMan Gene Expression Assays. Quantification of gene expression was normalized to B2m (for adult) or Rpl13a (for embryo). Taqman assays include: B2m (Mm00437762_m1), Col4a1 (Mm01210125_m1), Egfl6 (Mm00469452_m1), Itga8 (Mm01324958_m1), Lama5 (Mm01222029_m1), Npnt (Mm00473794_m1 for analysis of overall expression, Mm00473783_m1 for analysis of KO), and Rpl13a (Mm01612986_gH). Relative expression was determined by the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Histology and Immunofluorescence/Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and adult lungs were inflation fixed at 20–25 cm H2O in 10% neutral buffered formalin for embedding in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to visualize lung morphology. Whole slide scanning was performed using an Aperio Digital Pathology Slide Scanner in the University of Wisconsin Translational Research Initiatives in Pathology Core Laboratory. For immunofluorescence/immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized sections were steamed in IHC-Tek Epitope Retrieval Solution (IHCWorld) for 40 min, then blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and 5% serum. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody diluted in TBST containing 1% BSA. Primary antibodies included goat anti-mouse NPNT polyclonal (R&D, Catalog Number AF4298) at 2 µg/mL, rabbit anti-mouse collagen IV polyclonal (Chemicon/Millipore Sigma, Catalog Number AB756P) at 10 µg/mL, rabbit anti-human WT1 IgG (Invitrogen, clone SC06-41, Catalog Number MA5-32215) at 0.5 µg/mL, and IgG isotype controls (Jackson Immunoresearch). For immunofluorescence, staining was visualized using Alexa Fluor555-conjugated (Invitrogen) antibodies at 4 µg/mL and images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U epifluorescence microscope, using the same laser intensities to compare sections. For immunohistochemistry to detect WT1, sections were developed with the ImmPRESS HRP Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG Polymer Detection Kit (Vector Labs, Catalog Number MP-7451) and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Electron Microscopy

Embryonic lungs were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by further fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde buffered in 0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4 (PB). Lungs were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in PB, rinsed with distilled water, and dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol to 100%. For scanning electron microscopy (EM) dehydrated samples were critical-point dried in a Leica CPD300, sputtered coated with platinum (25 nm) in a Leica ACE600, and viewed in a Hitachi S3400N Variable Pressure SEM. For transmission EM, dehydrated lungs were transitioned with acetone and embedded in a resin mixture of Embed 812 kit and cured at 60°C. Samples were sectioned (90 nm) on a Leica Ultracut UC6 ultramicrotome, collected on a 1 × 2 mm Formvar-coated slot copper, poststained with uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate, and viewed at 80 kV on an FEI CM120 microscope. Images were captured with an AMT BioSprint12 digital camera.

Second Harmonic Generation Imaging

Lungs were dissected from E16.5 embryos and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging of the lungs was done using a Bruker Ultima Multiphoton scanhead on a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope. The system is coupled to a Coherent Chameleon Ti-Sapphire laser and equipped with Hamamatsu R3788 multi-alkali photomultipliers. Images were collected with a ×60 oil [1.4 numerical aperture (NA)] Nikon objective with a digital zoom of 3.3. The images were excited at 890 nm and filtered with a (450/40) filter cube for SHG, and a (562/30) filter for autofluorescence. The images were composed of a 10- to 12-µm z-stack with 1-µm steps at the surface of each lung. SHG images were preprocessed in ImageJ to remove residual autofluorescence by subtracting the channel for autofluorescence from the SHG channel. A maximum intensity projection was then made from the autofluorescence-subtracted stack. To visualize the fiber distribution in z, the autofluorescence-subtracted stack was resliced to obtain an orthogonal view, and then a maximum intensity projection was made.

Alkaline Phosphatase Staining of Embryo Lungs

Embryos at stage E12.5 were dissected from the uterine horns as described earlier and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing in PBS, lungs were removed from the dorsal side of the embryos and stained at room temperature with a solution prepared from Ready-to-Use NBT/CIP tablets (Roche). Lungs were stored in 20% glycerol and images were acquired using a Zeiss AxioZoom Stereo Microscope.

Ex Vivo Lung Lobe Culture

Lungs were dissected from embryos at stage E15.5 in sterile PBS. The cranial and accessory lobes were removed and placed contacting each other on a permeable support in a 12-well plate (Corning, Catalog Number 3462) containing DMEM plus 0.1% BSA in both the insert and well. Lungs were incubated for 2 days at 37°C/5% CO2, then washed three times with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (9). After washing in PBS, images of the lung lobes were acquired using a Zeiss AxioZoom Stereo Microscope. To visualize the area of fusion in embryonic KO lobes, tissue was embedded in paraffin and sectioned for staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Images were captured with a Keyence BZ-X800 microscope.

Respiratory Mechanics in Adult Mice

WT and NPNT KO males were weighed, anesthetized with isoflurane, and subjected to a tracheotomy to evaluate lung mechanics using a flexiVent instrument (SciReq, Montreal, QC, Canada). Mice were ventilated at a tidal volume of 10 mL/kg body wt, a positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cmH2O, and 150 breaths/min. Spontaneous respiration was suppressed by intraperitoneal injection of pancuronium bromide (0.08 mg/kg) and maintenance of the mice on 5% isoflurane. Resistance (Rrs), elastance (Ers), and compliance (Crs) of the respiratory system were determined using the Mouse Mechanics Scan script and flexiWare software version 7.6.

RESULTS

Npnt Expression in the Developing Mouse Lung

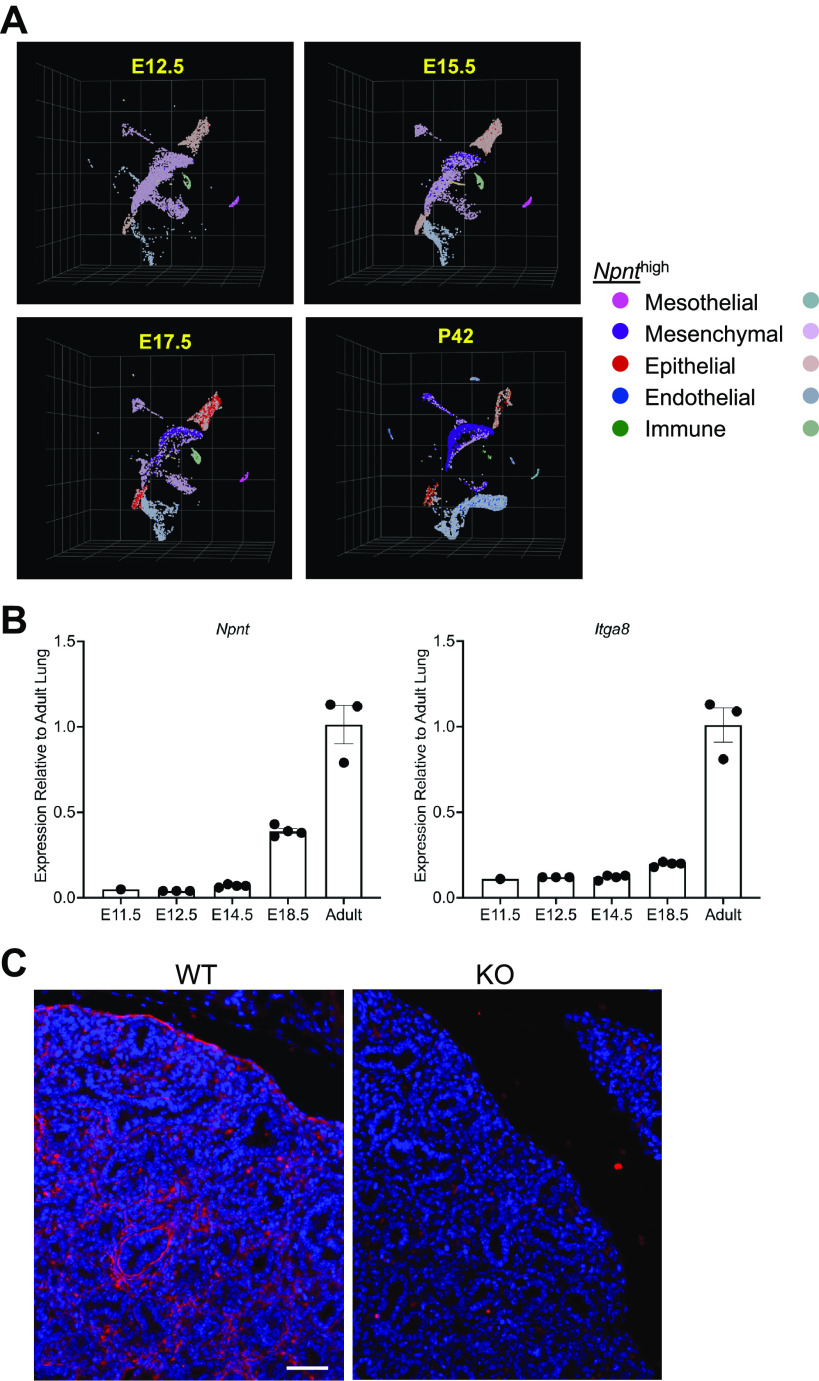

NPNT was previously shown to localize to BMs of the epithelia and visceral pleura in mouse embryonic lungs (1, 5). To determine all the cell types that express Npnt at specific stages in embryogenesis as well as postnatally, we mined an existing single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data set recently generated by Zepp et al. (14). Our analysis revealed that Npnt mRNA is found almost exclusively in mesothelial cells (that comprise the visceral pleura) at E12.5 and remains highly expressed in these cells during subsequent embryogenesis and the early postnatal period (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. S2; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17192711). By E15.5, low-level expression is also detected in epithelial and mesenchymal cells, and this expression becomes progressively stronger at E17.5 and in adult lung (Fig. 1A). By postnatal day 42, Npnt transcripts have substantially diminished in the mesothelial cell population (Fig. 1A). RT-PCR analysis showed that whole lung expression of both Npnt and its major receptor integrin α8 (Itga8) is lower in embryos relative to adult and increases during development (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Expression of Npnt mRNA and protein in mouse lungs. A: uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plots of lung cells at days E12.5, E15.5, and E17.5 in embryogenesis and in the adult (postnatal day 42). Lineages (muted colors) were defined as described in the materials and methods. Npnt expression on the UMAP plots is shown in bright colors. B: qPCR for Npnt and Itga8 from lung RNAs at days E11.5, E12.5, E14.5, and E18.5 in embryogenesis and from adult. Expression in the embryo lungs is shown relative to adult. Means ± SE. C: immunofluorescence for NPNT in E16.5 lungs from wildtype (WT) and knockout (KO). Scale bar, 50 µm.

Absence of NPNT during Embryogenesis Leads to Fusion of Right Lung Lobes after They Form

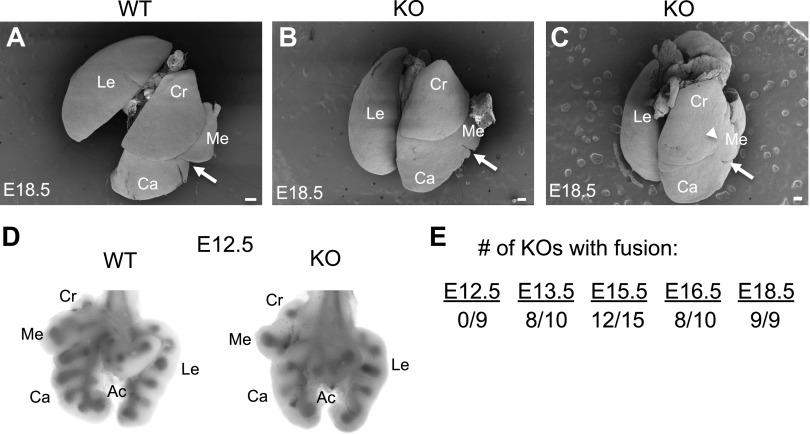

To assess a potential role for NPNT in lung development, we examined staged embryos with the genotypes Npnt+/+ (WT) and Npnt−/− (denoted Npnt KO). Immunofluorescence for NPNT in the lungs at embryonic stage E16.5 showed the expected pattern of protein localization in WT and absence of staining in KO (Fig. 1C). At this time point and later (E18.5, Fig. 2), we found that in KO embryos, the medial and caudal lobes of the right lung were fused (Fig. 2, B and C). Rather than the clear separation of these lobes seen in WT (arrow in Fig. 2A), there was only a cleft marking where the fissure should be in the KO (arrows in Fig. 2, B and C). In addition, some KO embryos exhibited partial fusion of the cranial lobe with the medial (arrowhead in Fig. 2C) and fusion of the proximal end of the accessory lobe to the caudal (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Characterization of lung lobe fusion in nephronectin (NPNT) knockout (KO) embryos. Scanning electron micrographs of dorsal views of lungs from wildtype (WT, A) and KO (B and C) embryos at E18.5 are shown. The accessory lobe is not readily visible from the dorsal side. The arrows denote the fusion between medial and caudal lobes, and the arrowhead denotes the area of fusion between the cranial and medial lobes. Abbreviations for the individual lung lobes: Ca, caudal; Cr, cranial; Me, medial; Ac, accessory; Le, left. Scale bars = 300 µm (A) or 200 µm (B and C). D: ventral views of whole mount WT and KO E12.5 lungs stained for alkaline phosphatase to visualize the lung lobe buds. E: the number of KO embryos demonstrating right lung lobe fusion at different stages in development is indicated.

To determine if the lobes fuse after they develop or if the phenotype is due to incomplete septation, we examined KO lungs at stage E12.5. At this time point, the primary lung buds have undergone secondary budding to form the five distinct lobes (one left, four right). KO lungs were indistinguishable from WT at E12.5 (Fig. 2D), indicating that budding was normal in the mutants. We then assessed lungs from embryos at different stages in development to establish when lobe fusion occurs in the KO. Fusion was not detected in KO lungs at E12.5 but was evident in the majority of mutants at E13.5, E.15.5, and E16.5 and in all E18.5 embryos examined (Fig. 2E).

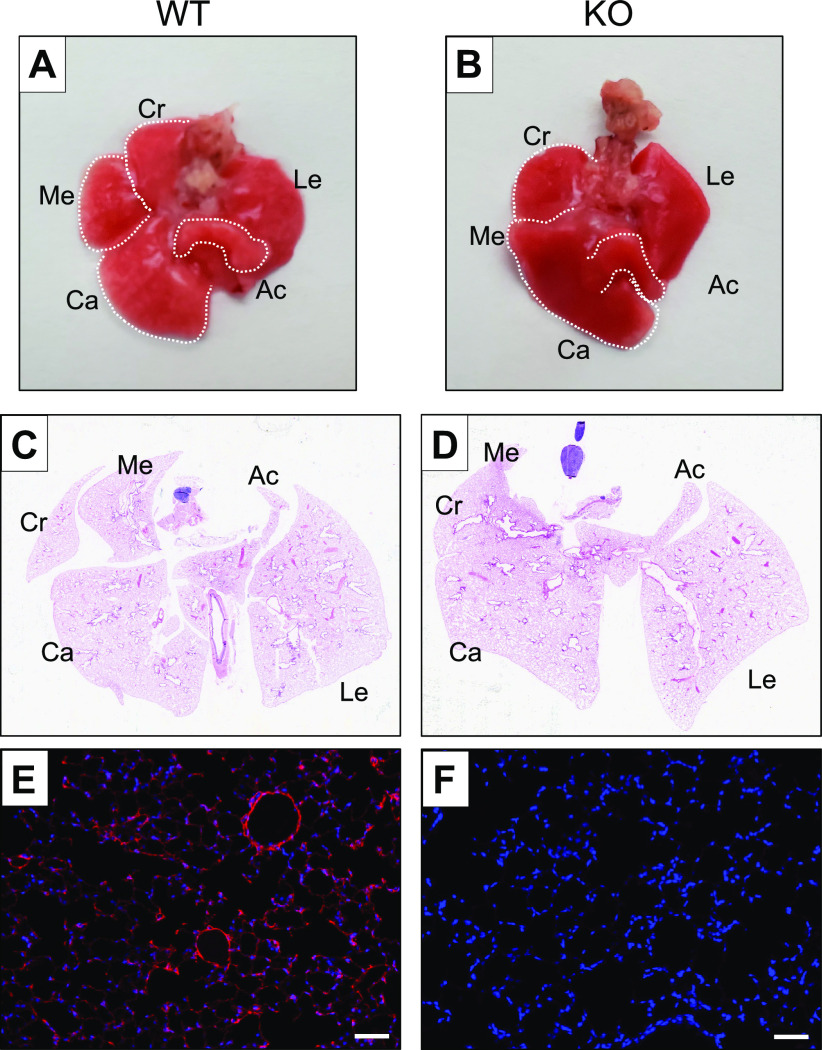

Persistence of the Lung Lobe Fusion Phenotype in Npnt KO Adults

Because kidney agenesis is incomplete in Npnt KOs and some of the mice develop one kidney (or infrequently both), a limited number of mutants can survive into adulthood. We examined the lungs in 32 adult KOs and found that all still exhibited fusion of the medial and caudal lobes of the right lung (Fig. 3, A and B), with 22% (7 of 32 examined) of the mice also showing involvement of the cranial lobe (Fig. 3, C and D) and 81% (13 of 16 examined) with fusion of the proximal end of the accessory lobe. Hence, in contrast to the kidney, NPNT deficiency in the lung is 100% penetrant. Immunofluorescence of WT lung sections showed that NPNT localizes to the alveoli as well as the basal aspect of airways and blood vessels (Fig. 3E), consistent with the classification of NPNT as a BM protein. We confirmed the absence of NPNT in adult KO lungs (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Right lung lobe fusion in nephronectin (NPNT) knockout (KO) adults. Gross ventral views of adult wildtype (WT, A) and KO (B) lungs, with individual right lobes outlined (dashed white lines). Lung sections from adult WT (C) and KO (D) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for whole slide scanning. Abbreviations for the individual lung lobes: Ac, accessory; Ca, caudal; Cr, cranial; Me, medial; Le, left. Immunofluorescence for NPNT in WT (E) and KO (F) lungs. Scale bar, 50 µm.

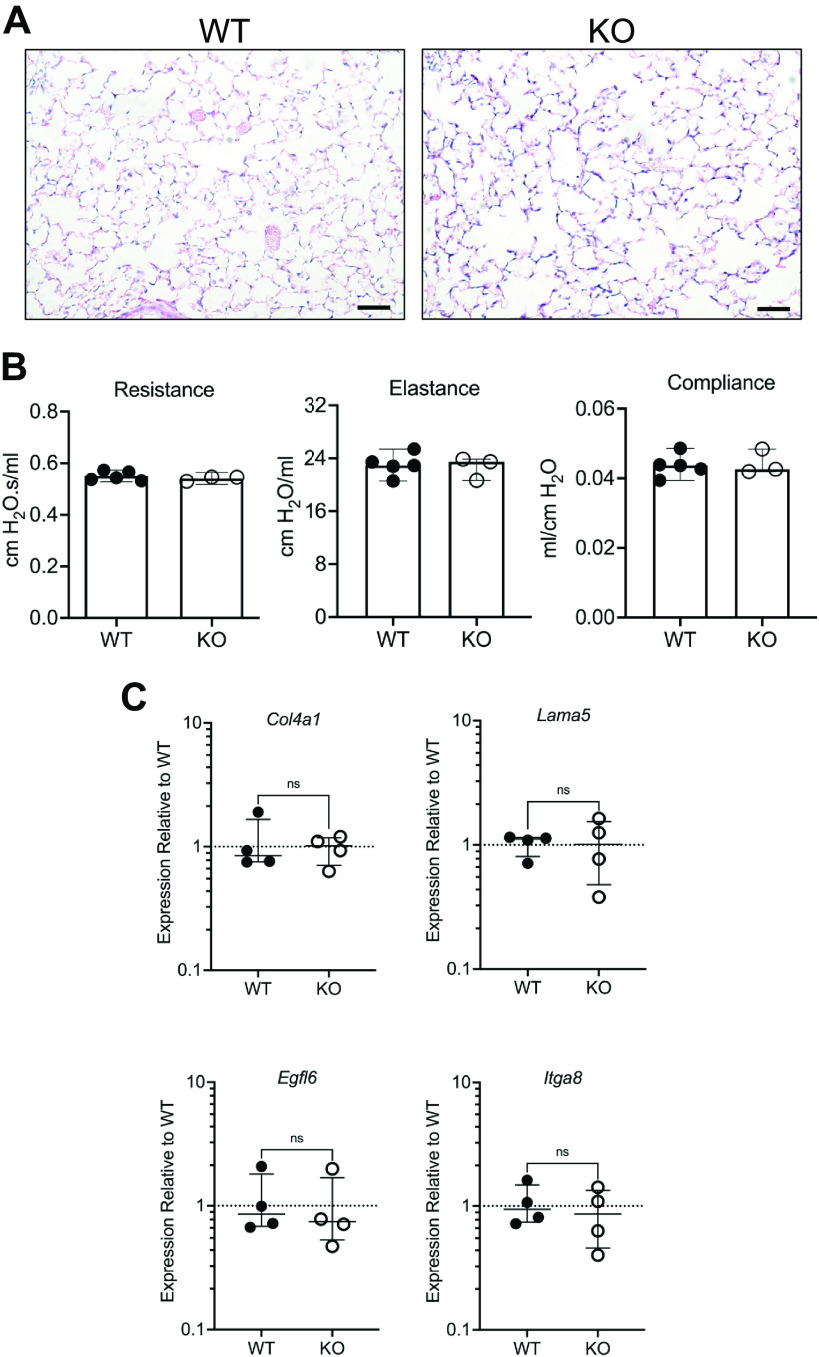

At the histological level, there were no apparent differences in the parenchyma of adult KO lungs as compared with WT (Fig. 4A). In support of this finding, no changes in resistance, elastance, or compliance of the respiratory system were observed in KO mice (Fig. 4B), suggesting that deletion of NPNT does not perturb overall lung mechanics. We also found no differences in transcript levels of the BM structural proteins collagen IV and laminin α5 (Fig. 4C). Laminin α5 is expressed in both embryonic and adult lungs and is the only laminin α subunit within the BM of the visceral pleura (15). No changes in expression of integrin α8 or the NPNT homologue EGFL6 were noted in adult KO lungs (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Characterization of lung lobe fusion in nephronectin (NPNT) knockout (KO) adults. A: representative images of sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin to show the parenchyma in lungs from wildtype (WT) and KO. Scale bar, 50 µm. B: parameters of lung mechanics in WT and KO adult males. The bars represent the means with 95% confidence intervals. C: transcriptional levels of collagen IV (Col4a1), laminin α5 (Lama5), EGFL6 (Egfl6), and integrin α8 (Itga8) in left lung RNA was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Shown are the medians with interquartile ranges. Statistical significance was assessed by a Mann–Whitney test using Prism 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, LLC).

Alterations in the Visceral Pleura of Npnt KO Embryonic Lungs

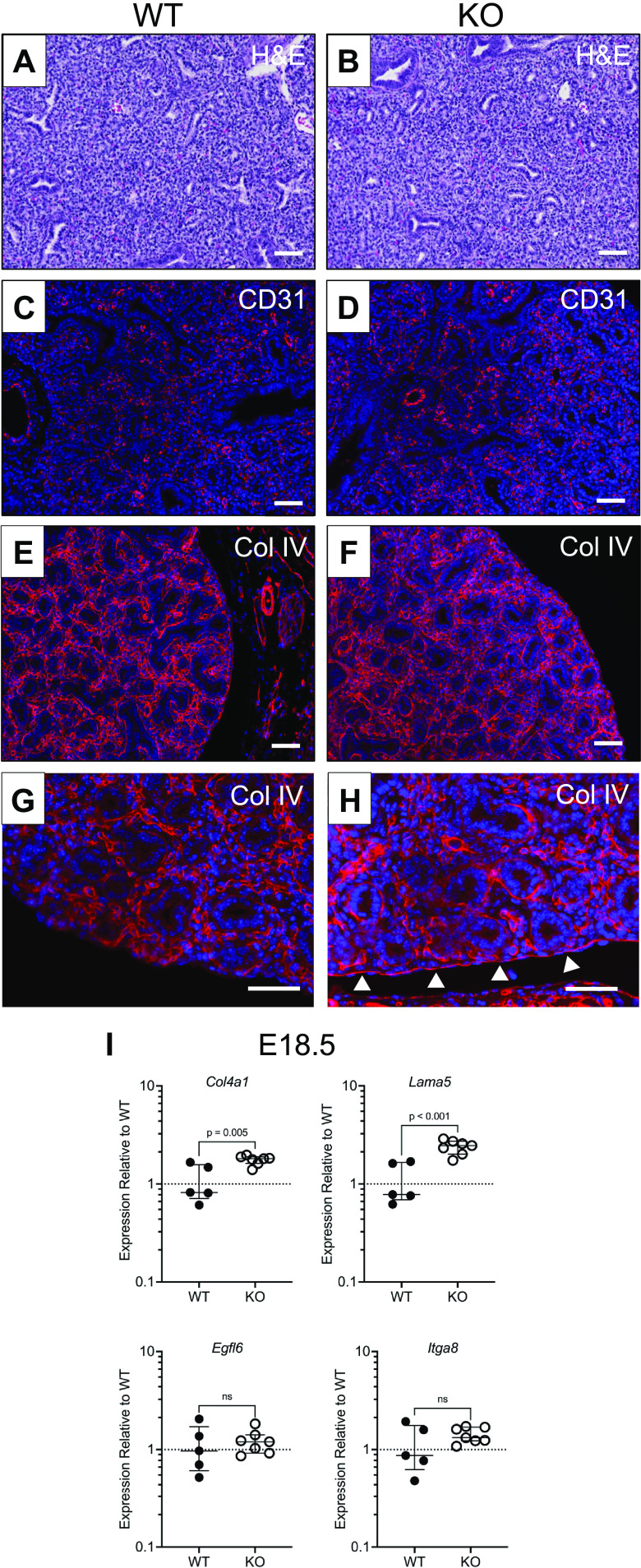

We then assessed if other defects were apparent in Npnt KO lungs during their development. As in the adult lung, WT and KO embryonic lungs had similar parenchymal morphology (Fig. 5, A and B), suggesting that branching morphogenesis is unaffected by the mutation. Similarly, the pattern of CD31 staining was equivalent in WT and KO lungs, indicating that the development of the vasculature is also not impacted by the deletion of NPNT (Fig. 5, C and D). Because NPNT is a BM protein, we evaluated whether its absence affected the two major BM structural proteins, collagen IV and laminin. Although the overall immunostaining profile of collagen IV appeared similar between the two genotypes (Fig. 5, E and F), high-power imaging showed increased deposition of the protein in the visceral pleura (Fig. 5, G and H). RT-PCR confirmed that both collagen IV and laminin α5 transcripts are elevated in KO embryo lungs, whereas expression of EGFL6 and integrin α8 was not different (Fig. 5I).

Figure 5.

Histological and gene expression analysis of embryonic nephronectin (NPNT) knockout (KO) lungs. Sections of wildtype (WT) (A, C, E, and G) and KO (B, D, F, and H) lungs at E16.5 were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A and B) or immunostained for CD31 (C and D) and collagen IV (E–H). In H, the arrowheads point to the enhanced immunostaining for collagen IV in the mesothelial basement membrane (BM) of KO lungs. Scale bar, 50 µm. I: transcriptional expression of collagen IV (Col4a1), laminin α5 (Lama5), EGFL6 (Egfl6), and integrin α8 (Itga8) was measured in E18.5 right lungs by quantitative RT-PCR. Shown are the medians with interquartile ranges. Statistical significance was assessed by an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test using Prism 9.4.1.

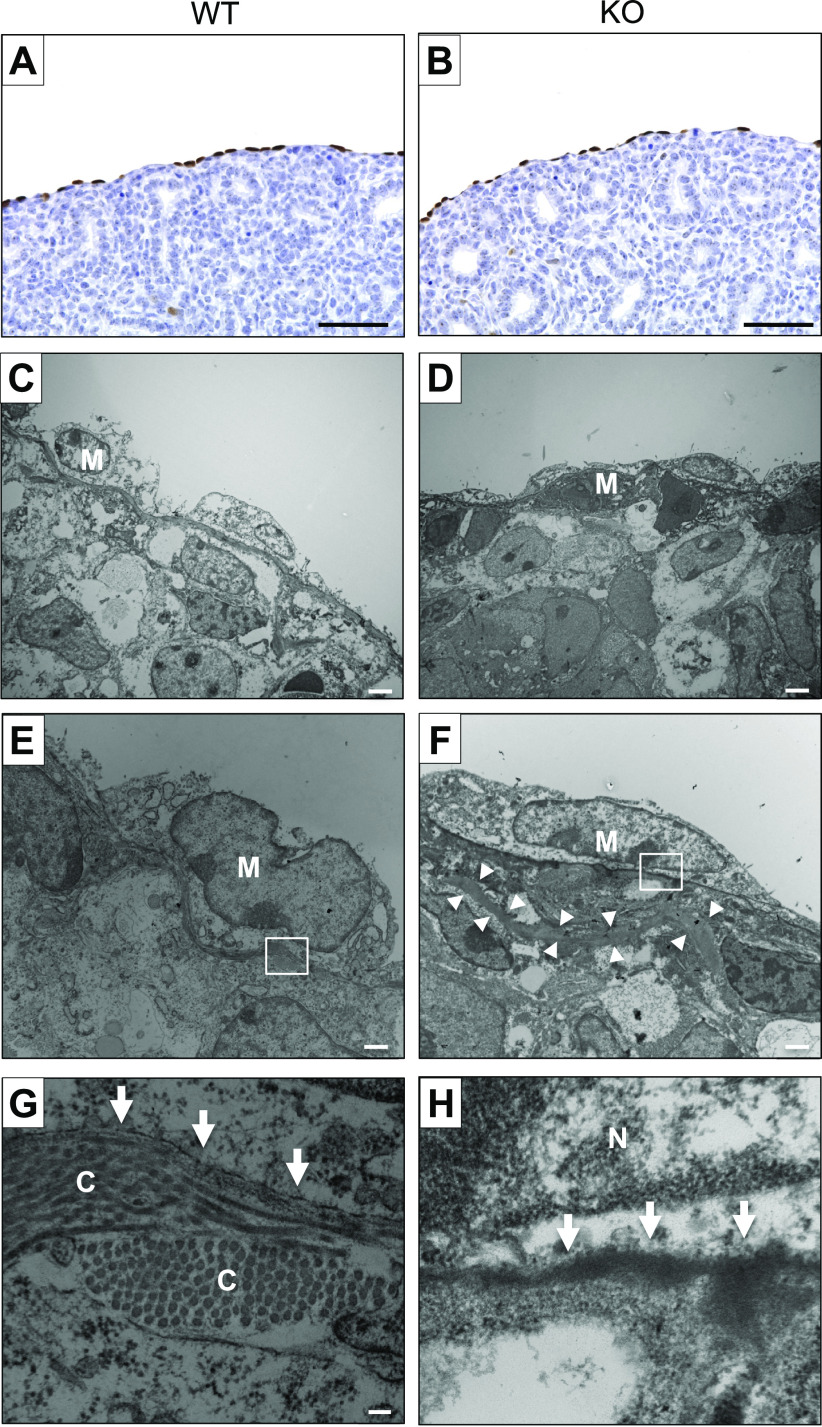

Given that NPNT is expressed in mesothelial cells of the visceral pleura (Fig. 1, A and C), and that this tissue layer has been implicated in mediating lobe formation (16), we examined the visceral pleura in E16.5 lungs. Both WT and KO visceral pleura were positive for the mesothelial cell marker Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) (Fig. 6, A and B). At the ultrastructural level, we found that the mesothelial layer appeared intact in KO lungs compared with WT and had no obvious structural changes in the cells (Fig. 6, C and D), which can vary in morphology from flattened and elongated to columnar or cuboidal (17). High-resolution imaging showed that in WT lungs, the visceral pleura is characterized by a well-defined BM and a discrete layer of collagen fibrils in the adjacent stroma (Fig. 6, E and G). By contrast, the BM appeared dense in some KOs (Fig. 6, F and H) or amorphous in others (Supplemental Fig. S3; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21603822). In addition, the KO visceral pleura was largely devoid of organized collagen fibrils at the BM interface (Fig. 6, G and H); instead, thick bundles of extracellular matrix (ECM) were observed farther into the stroma (arrowheads in Fig. 6G).

Figure 6.

Analysis of the visceral pleura in nephronectin (NPNT) knockout (KO) lungs at E16.5. Sections of wildtype (WT, A) and KO (B) lungs were immunostained for the mesothelial cell marker Wilms tumor 1 (WT1). Scale bar, 50 µm. Transmission electron microscopic images of WT (C, E, and G) and KO (D, F, and H) visceral pleura are shown. The boxed areas in E and F are shown at high magnification in G and H, respectively. The arrows indicate the BM, and the arrowheads point to thick cables of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the KO visceral pleura. C, collagen; Me, mesothelial cell; N, nucleus of mesothelial cell. Scale bars, 2 µm in C and D (×3,400), 1 µm in E and F (×7,100), 100 nm in G and H (×66,000).

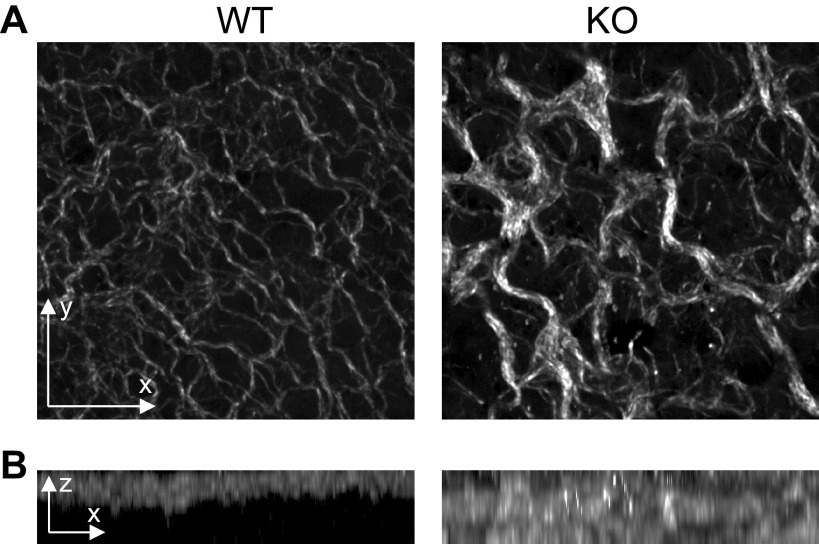

To further examine collagen organization in the visceral pleura, we imaged WT and KO embryonic lungs by second harmonic generation microscopy. As expected, the WT visceral pleura exhibited a thin layer of uniformly distributed and well-structured fibrils (Fig. 7A). In the KO, the visceral pleura contained disordered, thick fibrils (Fig. 7A) that extended to a greater depth in the stroma than in WT (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Characterization of fibrillar collagen in the visceral pleura of E16.5 lungs. Formalin-fixed lungs from embryos at E16.5 were assessed by second harmonic generation microscopy. A: en face z-stack images of the embryonic lung surface were obtained to visualize collagen fibrils (in white). The images shown are representative of three wildtype (WT) and four knockout (KO) lungs analyzed. B: orthogonal views of the z-stack images in A are shown to illustrate the collagen fibril depth and heterogeneity in KO visceral pleura. Orientation in the tissue is denoted by the arrows.

Npnt KO Embryonic Lung Lobes Can Fuse Ex Vivo

Benjamin et al. (9) showed that deletion of integrin α8, similar to its ligand NPNT, also gives rise to fused medial and caudal lobes of the right lung in embryos. These investigators performed a series of elegant experiments in which they isolated embryonic lobes not usually involved in fusion in vivo, namely the cranial and accessory lobes, and allowed the lobes to incubate in proximity for 48 h. They found that in contrast to WT, the cranial and accessory lobes from integrin α8 KO lungs were able to fuse ex vivo (9). Because we observed that the cranial lobes in Npnt KO lungs were not always fused, and accessory lobes exhibited only partial fusion, we were able to dissect out these lobes and use them in similar ex vivo experiments. We demonstrated that cranial and accessory lobes from Npnt KO embryos at E15.5 fuse ex vivo, but these lobes from WT or heterozygous embryos do not (Fig. 8A). Histological analysis of the KO lobes confirmed tissue fusion, with the fused area having the typical morphology of the surrounding parenchyma (Fig. 8B). The WT1 antibody immunostained the mesothelial cells on the lung surface, as expected, but not cells within the fusion (Fig. 8C). Together, these results indicate that in the KO, the specific lobes that fuse in vivo is dictated, at least in part, by proximity; that fusion is an active process, rather than a failure of lobes to form as separate entities; and that the process of fusion is accompanied by the loss of WT1 positivity.

Figure 8.

Fusion of knockout (KO) embryonic lung lobes ex vivo. A: cranial and accessory lung lobes from wildtype (WT), heterozygous (Het), and KO E15.5 embryos were isolated, placed in contact on a permeable support, and incubated 2 days before washing, fixation, and imaging. In B, fused lobes from a KO embryo lung were paraffin embedded and processed for sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin staining. The boxed area within the fusion site is shown magnified to the right of the image. In C, a separate section from the same fused lobes as in B was immunostained for Wilms tumor 1 (WT1). Magnified views of the visceral pleura (upper box) and the fusion area (lower box) are shown to the right of the image. Scale bars in C, 100 µm for original image, 50 µm for boxed areas.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that the absence of NPNT during lung morphogenesis in the mouse embryo results in the fusion of specific lobes in the right lung, similar to that observed in knockouts of integrin α8 (9, 18) and the FS-associated BM proteins FRAS1, FREM1, and FREM2 (10–12). Early in lung development, Npnt mRNA is almost exclusively expressed in mesothelial cells of the visceral pleura, a tissue layer that appears to play an integral role in lobation. Because the FS-associated proteins form a complex for NPNT deposition in BMs during embryogenesis, we propose that NPNT in the visceral pleural BM is an important link between this matrix and interstitial integrin α8, the key receptor for NPNT. Our working model is that these proteins interact to maintain proper lobation in the right lung as embryogenesis progresses, although the mechanism is not yet known.

During embryogenesis, lung development begins at E9–9.5 with the formation of two almost symmetrical primary buds from the laryngotracheal groove. The left lung bud produces the single left lobe and the right lung bud undergoes secondary budding to give rise to four lobes, the cranial, medial, caudal, and accessory, which are established by E12 (19, 20). Our results showed that secondary bud formation in KO lungs was similar to WT at E11.5 (data not shown) and that four distinct lobes were evident in the right lung at E12.5 (Fig. 2D). However, by E13.5, fusion of the medial and caudal lobes was detected in the majority of KO lungs, suggesting that a mechanism that governs fusion initiates between these two time points. By contrast, the integrin α8 KO was reported to still have separate lung lobes at E13, with the majority of E16 embryos showing lobe fusion (9), but this difference in timing of lobe fusion could be due to how embryos are staged. Regardless, in both KOs, fusion of the right lung lobes occurs after they have formed.

As was shown for the α8 KO, fusion in Npnt KO fetal lungs primarily occurs between the medial and caudal lobes, although the cranial lobe is also involved in 22% of the adult KOs that we have examined. Of note, the accessory lobe, which angles away from the other three right lobes toward the left, was fused to the caudal lobe in 81% of the adult KO lungs assessed, but only at the proximal end: the bulk of the lobe remained separate. Involvement of the cranial and accessory lobes was not previously reported for α8 KO lungs, although we have observed fusion of the proximal accessory lobe to the caudal in adult α8 KO lungs (our unpublished observations). When isolated at a fetal stage, the accessory and caudal lobes from Npnt KO lungs had an intrinsic ability to fuse ex vivo if in proximity (Fig. 8). Indeed, in proposing potential mechanisms for fusion of specific right lung lobes in the integrin α8 KO, Benjamin et al. (9) invoked proximity as an important determinant. Once fusion of the lobes occurs in the Npnt KO embryo, the fusion persists throughout adulthood, with no discernible effects on respiratory mechanics (Fig. 4). Moreover, our ex vivo experiments suggest that fusion is limited to the fetal stages of lung development (Fig. 8). In support of this conclusion, right lung lobes from mice with postnatal deletion of NPNT (using the Npnt-Flox allele in conjunction with a tamoxifen-inducible ROSA-CreER allele) do not undergo fusion (our unpublished observations). NPNT may no longer be functionally required in the visceral pleura for maintaining lobation at adult stages. Indeed, our analysis of the mouse lung scRNA-seq atlas showed that there is little to no expression of Npnt in mesothelial cells from 6-wk-old mice (Fig. 1). Accordingly, FRAS1 immunostaining in fetal lungs also decreases in late-stage embryogenesis (10). The same phenomenon was observed in the skin, where levels of FRAS1 and other FS-associated proteins, which promote anchoring of the epidermis to the papillary dermis, are abundant in early embryogenesis but then decline (21). Collagen VII has been proposed to functionally replace the FS-associated proteins in the postnatal skin (22), and there may be a similar substitution process occurring in the lung.

In both fetal and adult Npnt KOs, we did not observe any other obvious defects in the lung parenchyma (Figs. 4 and 5), aside from right lobe fusion. At E16.5, branching morphogenesis and development of the vasculature appeared to be normal, as was also noted in the FRAS1 and FREM2 KOs (10, 12), as well as the laminin α5 KO, in which the lung mesothelial BM is entirely absent (15). In addition, compared with WT, the lung epithelia in Npnt KOs showed no difference in the overall immunostaining pattern for collagen IV, a major structural protein in BMs, although expression of the transcripts for both collagen IV and laminin α5 were upregulated in embryonic lungs (Fig. 5). Of note, there was no difference in expression of these genes in lungs from adult mutants, indicating that the increase is transient and limited to embryogenesis. Although Egfl6 transcript levels were not altered in the Npnt KO lung, EGFL6 is normally present in BMs of the epithelia in the developing lung (5) and may compensate for the lack of NPNT in this compartment. In contrast to the Npnt KO, lungs from integrin α8-deficient embryos showed a reduction in branching and alterations in its patterning, both of which were rescued during postnatal alveolarization (18); here, the function of integrin α8β1 is likely mediated by ligands other than NPNT, such as fibronectin (8) or tenascin-C (23, 24).

The mechanism by which NPNT acts to maintain the separation of the lobes in the mouse fetal right lung is unknown. The visceral pleura likely plays an integral role in lobation, because it has been described as folding into the lung to separate the mesenchyme that envelops the lobar bronchi (16). The pleura consists of a thin sheet of mesothelial cells attached to a BM and includes the underlying connective tissue. Mesothelial cells in Npnt KO embryo lungs express the marker WT1 (Fig. 6), similar to α8 KO lungs (9), suggesting that their differentiation state is not affected in these mutants. However, WT1 was not detected in regions of fusion, either ex vivo (Fig. 8) or in vivo (data not shown). These results suggest that fusion involves the loss of mesothelial cells and/or a change in their identity. One possibility is that the mesothelial cells transdifferentiate as fusion occurs. Lineage-labeling studies have shown that in the normal course of embryogenesis, mesothelial cells undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and contribute to vascular smooth muscle cells and mesenchyme in the lung, with no detectable WT1 positivity outside of the visceral pleura (25, 26). Additional work will need to be done to assess fully the transdifferentiation potential of Npnt KO mesothelial cells and track their fate during lobe fusion.

Analysis of the visceral pleura by transmission electron microscopy confirmed that the mesothelial cells appeared normal in KO embryonic lungs as compared with WT. However, there were notable differences in the visceral pleura BM and adjacent connective tissue of KO embryonic lungs: the BM did not form a sharp boundary between the mesothelial cells and the stroma as it does in WT (Fig. 6). We speculate that this change in BM morphology may be due to the increased collagen IV in this matrix as observed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 5). In addition, the disposition and attributes of collagen fibrils at the BM-stroma interface were markedly abnormal (Fig. 7). Taken together, these findings give rise to the possibility that NPNT in the BM, potentially through cross talk with interstitial cells, is involved in regulating the deposition and organization of ECM in the visceral pleura in embryogenesis. Less collagen fibrils in the proximal stroma may destabilize the pleura and promote the de-adhesion and movement of cells. Supporting this idea, Benjamin et al. (9) found that α8-deficient mesenchymal cells migrate faster than WT in vivo, which they posited could contribute to the fusion phenotype. Because our results strongly suggest that NPNT is the relevant ligand for integrin α8 in regulating lung lobe separation, lack of this ligand could elicit similar changes in mesenchymal cell behavior. The loss of NPNT likely has such a dramatic effect on the visceral pleura because EGFL6 is not strongly expressed in this compartment (5) and appears to be unavailable to substitute for NPNT. Further investigations to characterize the phenotype of Npnt KO mesothelial cells from fetal lung and their interactions with mesenchymal cells should help delineate the role of this protein in lobation.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21603804.

Supplemental Fig. S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17192711.

Supplemental Fig. S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21603822.

GRANTS

This study was partially funded by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL133751 (to L.M.S.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.L.W. and L.M.S. conceived and designed research; C.L.W. and B.M.B. performed experiments; C.L.W., C.F.H., B.M.B., and S.A.G. analyzed data; C.L.W., C.F.H., and L.M.S. interpreted results of experiments; C.L.W. prepared figures; C.L.W. drafted manuscript; C.L.W., C.F.H., S.A.G., and L.M.S. edited and revised manuscript; C.L.W., C.F.H., B.M.B., S.M.P., S.A.G., and L.M.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Hiram Gonzalez and David Andes in the Department of Medicine, Randall Massey in the School of Medicine and Public Health EM Core, and William Schneider in the Geosciences EM Core for assistance with tissue preparation and electron microscopy; the Medical University of South Carolina Histology Core; Leilani Marty-Santos and Deneen Wellik in the Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology for sharing RNA from staged WT embryos; and Benjamin Simon for excellent technical assistance. The authors also acknowledge the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Translational Research Initiatives in Pathology Laboratory and Experimental Animal Pathology Laboratory, supported by P30 CA014520, for use of their services. The graphical abstract image was created with BioRender.com and published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brandenberger R, Schmidt A, Linton J, Wang D, Backus C, Denda S, MüLler U, Reichardt LF. Identification and characterization of a novel extracellular matrix protein nephronectin that is associated with integrin alpha8beta1 in the embryonic kidney. J Cell Biol 154: 447–458, 2001. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Linton JM, Martin GR, Reichardt LF. The ECM protein nephronectin promotes kidney development via integrin alpha8beta1-mediated stimulation of Gdnf expression. Development 134: 2501–2509, 2007. doi: 10.1242/dev.005033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Müller U, Wang D, Denda S, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA, Reichardt LF. Integrin alpha8beta1 is critically important for epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during kidney morphogenesis. Cell 88: 603–613, 1997. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sato Y, Uemura T, Morimitsu K, Sato-Nishiuchi R, Manabe R, Takagi J, Yamada M, Sekiguchi K. Molecular basis of the recognition of nephronectin by integrin alpha8beta1. J Biol Chem 284: 14524–14536, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900200200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiyozumi D, Takeichi M, Nakano I, Sato Y, Fukuda T, Sekiguchi K. Basement membrane assembly of the integrin α8β1 ligand nephronectin requires Fraser syndrome-associated proteins. J Cell Biol 197: 677–689, 2012. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sato Y, Shimono C, Li S, Nakano I, Norioka N, Sugiura N, Kimata K, Yamada M, Sekiguchi K. Nephronectin binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans via its MAM domain. Matrix Biol 32: 188–195, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kiyozumi D, Sugimoto N, Sekiguchi K. Breakdown of the reciprocal stabilization of QBRICK/Frem1, Fras1, and Frem2 at the basement membrane provokes Fraser syndrome-like defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 11981–11986, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601011103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wagner TE, Frevert CW, Herzog EL, Schnapp LM. Expression of the integrin subunit alpha8 in murine lung development. J Histochem Cytochem 51: 1307–1315, 2003. doi: 10.1177/002215540305101008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Benjamin JT, Gaston DC, Halloran BA, Schnapp LM, Zent R, Prince LS. The role of integrin alpha8beta1 in fetal lung morphogenesis and injury. Dev Biol 335: 407–417, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petrou P, Pavlakis E, Dalezios Y, Galanopoulos VK, Chalepakis G. Basement membrane distortions impair lung lobation and capillary organization in the mouse model for Fraser syndrome. J Biol Chem 280: 10350–10356, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beck TF, Shchelochkov OA, Yu Z, Kim BJ, Hernández-García A, Zaveri HP, Bishop C, Overbeek PA, Stockton DW, Justice MJ, Scott DA. Novel frem1-related mouse phenotypes and evidence of genetic interactions with gata4 and slit3. PloS one 8: e58830, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Timmer JR, Mak TW, Manova K, Anderson KV, Niswander L. Tissue morphogenesis and vascular stability require the Frem2 protein, product of the mouse myelencephalic blebs gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11746–11750, 2005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505404102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foo SS, Turner CJ, Adams S, Compagni A, Aubyn D, Kogata N, Lindblom P, Shani M, Zicha D, Adams RH. Ephrin-B2 controls cell motility and adhesion during blood-vessel-wall assembly. Cell 124: 161–173, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zepp JA, Morley MP, Loebel C, Kremp MM, Chaudhry FN, Basil MC, Leach JP, Liberti DC, Niethamer TK, Ying Y, Jayachandran S, Babu A, Zhou S, Frank DB, Burdick JA, Morrisey EE. Genomic, epigenomic, and biophysical cues controlling the emergence of the lung alveolus. Science 371: eabc3172, 2021. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nguyen NM, Miner JH, Pierce RA, Senior RM. Laminin alpha 5 is required for lobar septation and visceral pleural basement membrane formation in the developing mouse lung. Dev Biol 246: 231–244, 2002. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schittny JC. Development of the lung. Cell Tissue Res 367: 427–444, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2545-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Batra H, Antony VB. The pleural mesothelium in development and disease. Front Physiol 5: 284, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cremona TP, Hartner A, Schittny JC. The development of integrin alpha-8 deficient lungs shows reduced and altered branching and a correction of the phenotype during alveolarization. Front Physiol 11: 530635, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.530635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hogan BL. Morphogenesis. Cell 96: 225–233, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Warburton D, Schwarz M, Tefft D, Flores-Delgado G, Anderson KD, Cardoso WV. The molecular basis of lung morphogenesis. Mech Dev 92: 55–81, 2000. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pavlakis E, Chiotaki R, Chalepakis G. The role of Fras1/Frem proteins in the structure and function of basement membrane. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 43: 487–495, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chiotaki R, Petrou P, Giakoumaki E, Pavlakis E, Sitaru C, Chalepakis G. Spatiotemporal distribution of Fras1/Frem proteins during mouse embryonic development. Gene Expr Patterns 7: 381–388, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schnapp LM, Hatch N, Ramos DM, Klimanskaya IV, Sheppard D, Pytela R. The human integrin alpha 8 beta 1 functions as a receptor for tenascin, fibronectin, and vitronectin. J Biol Chem 270: 23196–23202, 1995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.23196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao Y, Young SL. Tenascin in rat lung development: in situ localization and cellular sources. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 269: L482–L491, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.4.L482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Que J, Wilm B, Hasegawa H, Wang F, Bader D, Hogan BL. Mesothelium contributes to vascular smooth muscle and mesenchyme during lung development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 16626–16630, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808649105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dixit R, Ai X, Fine A. Derivation of lung mesenchymal lineages from the fetal mesothelium requires hedgehog signaling for mesothelial cell entry. Development 140: 4398–4406, 2013. doi: 10.1242/dev.098079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21603804.

Supplemental Fig. S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17192711.

Supplemental Fig. S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21603822.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.