Abstract

Purpose

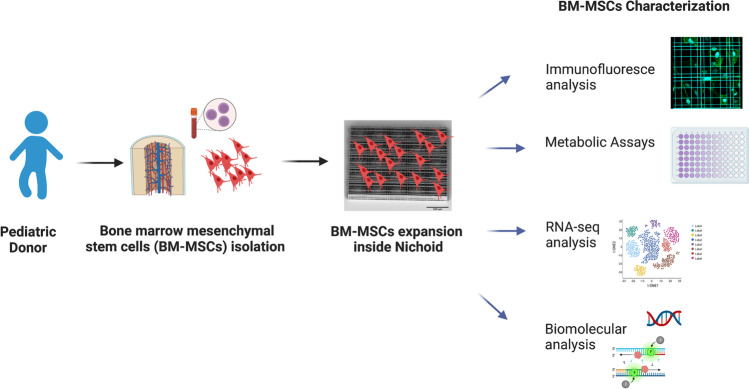

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a promising source for stem cell therapies in numerous diseases, including pediatric respiratory system diseases. Characterized by low immunogenicity, high anti-inflammatory, and immunoregulatory features, MSCs demonstrated an excellent therapeutic profile in numerous in vitro and preclinical models. MSCs reside in a specialized physiologic microenvironment, characterized by a unique combination of biophysical, biochemical, and cellular properties. The exploitation of the 3D micro-scaffold Nichoid, which simulates the native niche, enhanced the anti-inflammatory potential of stem cells through mechanical stimulation only, overcoming the limitation of biochemical and xenogenic growth factors application.

Materials and Methods

In this work, we expanded pediatric bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) inside the Nichoid and performed a complete cellular characterization with different approaches including viability assays, immunofluorescence analyses, RNA sequencing, and gene expression analysis.

Results

We demonstrated that BM-MSCs inside the scaffold remain in a stem cell quiescent state mimicking the condition of the in vivo environment. Moreover, the gene expression profile of these cells shows a significant up-regulation of genes involved in immune response when compared with the flat control.

Conclusion

The significant changes in the expression profile of anti-inflammatory genes could potentiate the therapeutic effect of BM-MSCs, encouraging the possible clinical translation for the treatment of pediatric congenital and acquired pulmonary disorders, including post-COVID lung manifestations.

Lay Summary

Regenerative medicine is the research field integrating medicine, biology, and biomedical engineering. In this context, stem cells, which are a fundamental cell source able to regenerate tissues and restore damage in the body, are the key component for a regenerative therapeutic approach. When expanded outside the body, stem cells tend to differentiate spontaneously and lose regenerative potential due to external stimuli. For this reason, we exploit the scaffold named Nichoid, which mimics the in vivo cell niche architecture. In this scaffold, mesenchymal stem cells “feel at home” due to the three-dimensional mechanical stimuli, and our findings could be considered as an innovative culture system for the in vitro expansion of stem cells for clinical translation.

Future Perspective

The increasing demand of safe and effective cell therapies projects our findings toward the possibility of improving cell therapies based on the use of BM-MSCs, particularly for their clinical translation in lung diseases.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Regenerative medicine, Mesenchymal stem cells, Nichoid scaffold, Engineered stem cell niche

Introduction

A regenerative approach based on stem cell potential is nowadays studied as a potential treatment for respiratory system diseases in adult as well as pediatric patients [1, 2]. To this end, the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) could be of crucial interest as these are primary candidates for cellular therapies and tissue engineering [3]. Indeed, MSCs are multipotent cells that can self-renew and differentiate into multiple tissue-forming cell lineages [4], showing secretion [5], homing [6], and immunomodulatory properties.

For these reasons, MSCs were found to have a good therapeutic efficacy in congenital and acquired pulmonary diseases, including SARS-COV-2 infection [7, 8], as demonstrated in pre-clinical studies and clinical trials performed in both adult and pediatric patients [9–11]. Indeed, both congenital interstitial lung disease [12, 13] and pulmonary injury due to infectious etiology (SARS, H1N1, COVID-19) appear to be characterized by inflammatory and fibrotic changes in the lung parenchyma, leading to gas exchange impairment and chronic respiratory failure associated with high morbidity and mortality. In this setting, MSCs regulate immune and inflammatory responses, thus supporting reparative and regenerative processes. Nowadays, 285 MSCs clinical trials involve pediatric patients affected by different diseases, including osteogenesis imperfecta, perinatal arterial ischemic stroke, diabetes, and pneumonia. Unfortunately, only 10 registered clinical trials were completed or reached the recruitment for phase III. The lack of therapeutic effect could be related to the conventional systems for stem cell expansion, which do not mimic the physiological environment, causing spontaneous stem cell differentiation and senescence [14, 15]. Several research groups overcame this limitation using biochemical or exogenous growth factors, such as leukemia inhibitor factor (LIF) and bovine serum albumin (BSA), for basic research [16, 17]. From a regulatory point of view when referring to clinical translation, the addition of exogenous factors represents a cellular manipulation, and this is considered a risk when the cells or their products must be transferred to pediatric patients [18, 19]. In this context, the use of 3D scaffolds or biomaterials to better simulate a physiological ex-vivo environment is becoming more relevant. Indeed, in 2019, Chen et al. studied a 3D-printed cartilage extracellular matrix (ECM)/gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) loaded with MSCs exosomes for the treatment of osteoarthritis [20]. The following year, Ji et al. demonstrated a possible application of chitin-derived hydrogels to encapsulate MSCs for bone regeneration [21]. Finally, a recent publication by Dong et al. exploited an electrospun polycaprolactone/silk fibroin scaffold functionalized with MSC-derived extracellular matrix [22].

Alternative mechanical-induced culture methods have been proposed to maintain or even increase the therapeutic properties of stem cells, and among them, there is the micro-engineered three-dimensional substrate Nichoid, which recapitulates the architecture of the physiological niche in vitro [23]. This scaffold mimics the physiological environment of MSCs, and thus, the stemness features and the immunomodulatory properties of these cells are maintained or even increased. Indeed, previous studies demonstrated the Nichoid’s ability to affect stem cells’ migration and proliferation [23–29]. This approach was also found to enhance the pluripotency and differentiation capabilities of stem cells isolated from different sources simply through the arrangement of geometric and physical distribution [30–32]. Recent studies also confirmed the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Nichoid-cultured neural precursors cells in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease [30] and the molecular signature associated with mechanotransduction processes induced simply through the Nichoid mechanical stimulation [31, 32]. It is for this reason that the expansion of MSCs inside the Nichoid scaffold could represent a potential therapeutic prospect for respiratory diseases. For the first time, in this study, we performed a comprehensive characterization of pediatric bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) expanded inside the Nichoid in terms of viability, morphology, and gene expression analysis, opening the possibility to the exploitation of this micro-scaffold as a stem cell expansion platform for translational medicine, including pediatric lung disease.

Materials and Methods

Mesenchymal Stem Cells

BM-MSCs were isolated and expanded from residual bone marrow cells harvested from a female pediatric 10 years old patient, after signing an informed consent, as previously reported in [33], that have been used in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [33]. Mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient separation and plated at the density of 160.000 cells/cm2 in complete medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (D‐MEM-Low Glucose + Glutamax) (Gibco) supplemented with 5% human platelet lysate (Macopharma), and 1% Gentamicine (Gibco)). Cultures were kept at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. After 48 h, non-adherent cells were removed, and culture medium was replaced twice a week. At confluence, ≥ 80% MSCs were detached with recombinant Trypsin–EDTA (Euroclone) and replated. BM-MSC surface antigens were evaluated by flow cytometry using CD73, CD90, CD105, and class I-HLA as positive markers and CD34, CD14, CD45, and CD31 (all antibodies from Beckman Coulter) as negative markers. Briefly, 1 × 105 cells/tube were incubated at 4 °C with FITC or PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Ten thousand events were acquired by the FACS Navios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Analysis was performed by Navios software (Beckman Coulter).

Microfabrication of Nichoids

3D micro-scaffold Nichoids were fabricated on circular glass coverslips 150–170 μm thick and with a 12 mm diameter (BioOptika) previously covered with 23 μl of SZ2080 photoresist by drop-casting. Nichoid microfabrication through two-photon polymerization was done as previously reported [34]. Samples were developed in solvent solution to remove the unpolymerized resin and characterized through scanning electron microscopy (Phenom Pro, Phenom World) to ensure their integrity. Before cell culture, Nichoids were sterilized by washing with deionized water, then they were covered with ethanol 70% for 1.5 h and then exposed to UV radiation for 1 h.

Cell Seeding Inside the Nichoid Scaffold

1 × 104 BM-MSCs at passage 3–5 were seeded inside the Nichoid and in standard 2D condition (plastic multiwell polystyrene) in a single drop of 35 μl of culture medium. The multi-well was then kept in the incubator for a minimum of 1 h to allow cells to enter inside the niches. After that, the Nichoid was covered with complete medium.

Immunocytochemistry Analysis

Cells were seeded inside the Nichoid and on ethanol-washed glass coverslips as 2D control. After 7 days of cell expansion, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific), pH 7.4, for 20 min at room temperature, and then washed with PBS following the protocol reported in [31, 35]. The coverslips were incubated overnight at 4 °C in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum (NGS, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.3% Triton X-100 (BDH, VWR), and the appropriate primary antibody. Cell features were assessed with antibodies against Vimentin (1:200 Immunological Sciences). To visualize alpha-actin filaments, cells were stained using Phalloidin, Fluorescein Isothiocyanate Labeled (Phalloidin-FITC, 1:50, Sigma). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Then, BM-MSCs were rinsed with PBS and 10% NGS and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor® 488 and 647, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1.5 h. Samples were mounted using Prolong glass antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Olympus FluoView FV10i). As a control, the appropriate secondary antibody was administrated omitting the primary one (Alexa Fluor® 488 or 647, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunocytochemistry analysis was performed acquiring three different fields for each sample for three independent experiments.

Alamar Blue Assay

The Alamar Blue assay (Thermo Fisher) is a metabolic assay that uses the reducing power of living cells as a cellular health indicator [36]. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, from a stock solution of 0.2 mg/ml of resazurin solution, a dilution of 1:10 was used for each sample, and the multiwell was incubated for 24 h in the dark and avoiding light exposure inside the incubator. The solution was then transferred in a 96 multiwell plate, and the absorbance at 570 nm and 600 nm was detected with a Multiskan GO spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The equation applied to determine the percent reduction of resazurin is the following:

where

- λ1

570nm (reduced)

- λ2

600nm (oxidized)

- CRED

concentration of reduced form of resazurin

- COX

oxidized form of resazurin

- εOX

molar extinction coefficient of resazurin oxidized form

- εRED

molar extinction coefficient of resazurin reduced form

- A

absorbance of test wells

- A’

absorbance of negative control well. The negative control well should be a mix of clean culture media and resazurin.

| Wavelength (λ) | εOX | εRED |

|---|---|---|

| 570 nm | 80,586 | 155,677 |

| 600 nm | 117,216 | 14,652 |

RNA Extraction and Library Preparation for RNA-Seq and Bioinformatic Data Analysis

Total RNA from cells expanded for 7 days inside the Nichoid and in control condition was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) following standard protocol and then quantified using the Multiskan GO spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Extracted RNA was used for both gene profiling study and PCR analysis. RNA-seq libraries were prepared with the CORALL Total RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (Lexogen, Vienna, Austria) using 500 ng total RNAs of BM-MSCs-Nichoid and BM-MSCs grown in control condition. The RiboCop rRNA Depletion Kit (Lexogen, Vienna, Austria) was used to remove rRNA. Qualities of sequencing libraries were assessed with D1000 ScreenTape Assay using the 4200 TapeStation System (Agilent) and quantified with Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen). BlueBee® Genomics Platform (Lexogen, Austria) pipeline was used to obtain transcript abundance, and the quality of individual sequences was evaluated using FastQC software (version 0.11.9). Adapters were trimmed with Cutadapt software, whereas UMI were removed with UMI tools. Reads were mapped using STAR software (version 2.7) with Gencode Release 27 (GRCh38) as a reference, and transcript intensities were computed using the Mix2 RNA-Seq Data Analysis Software (Lexogen, Austria) with the “-strandness forward” option. Differential expression analysis was performed using R package DESeq2, and genes were considered differentially expressed with |log2(Nichoid samples/Control samples)|≥ 1 and a False Discovery Rate ≤ 0.1 [37]. Moreover, R software was used to generate heatmaps (heatmap.2 function from the R ggplots package) and PCA plots (prcomp function from the R ggplots package [38]). The NDEx plugin [39] was used to perform analyses concerning the interaction of the differentially expressed genes [40]. The pathways analysis was performed through g:Profiler ordering differentially expressed coding genes according to |log2(Nichoid/Control)| and considering the Reactome database [41, 42].

Real-Time PCR Analysis

A total of 500 ng of RNA were retrotranscribed using the iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad) kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed with the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad) using SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The NCBI’s Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) tool was used to design primers. Gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method as reported by [43]. GAPDH was used as endogenous control.

Primers used for BM-MSCs analysis:

| GAPDH FW | AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT |

| GAPDH REV | AGCCTTGACGGTGCCATGGAATTTGCCATG |

| CYCLIN E FW | CGTGCGTTTGCTTTTACAGA |

| CYCLIN E REV | AGCACCTTCCATAGCAGCAT |

| CCNB1 FW | CGGGAAGTCACTGGAAACAT |

| CCNB1 REV | AAACATGGCAGTGACACCAA |

| CDK2 FW | GCCCTAATCTCACCCTCTCC |

| CDK2 REV | AAGGGTGGTGGAGGCTAACT |

| FGF1 FW | GTGGATGGGACAAGGGACAG |

| FGF1 REV | ATTTGGTGTCTGTGAGCCGT |

| PAG1 FW | TCATTGCTGGGAAAAGGCCAAGA |

| PAG1 REV | AGAGCTGTGTCCTTGGAGGAA |

| SOCS3 FW | GGAGGTGACGAGCCCCC |

| SOCS3 REV | AAACTTGCTGTGGGTGACCA |

Statistical Analysis

Statistics was evaluated using GraphPad Prism 8 version (GraphPad Software). When two conditions were analyzed, Student’s unpaired t-test was used. When three or more conditions were analyzed, one-way ANOVA was used followed by Tukey’s post-test. For all in vitro experiments, data are reported as mean ± standard error mean (SEM). The level of statistical significance was set at p-value = 0.05.

Results

Characterization of BM-MSCs Expanded Inside the Nichoid

BM-MSC surface antigens were evaluated by flow cytometry to confirm mesenchymal features. CD90, CD73, CD105, and HLA-I surface antigens were expressed on more than 95% of MSCs, while less than 5% resulted positive for CD31, CD34, CD14, and CD45 molecules resulting compliant to the criteria defined by the International Society for Cellular Therapy [44].

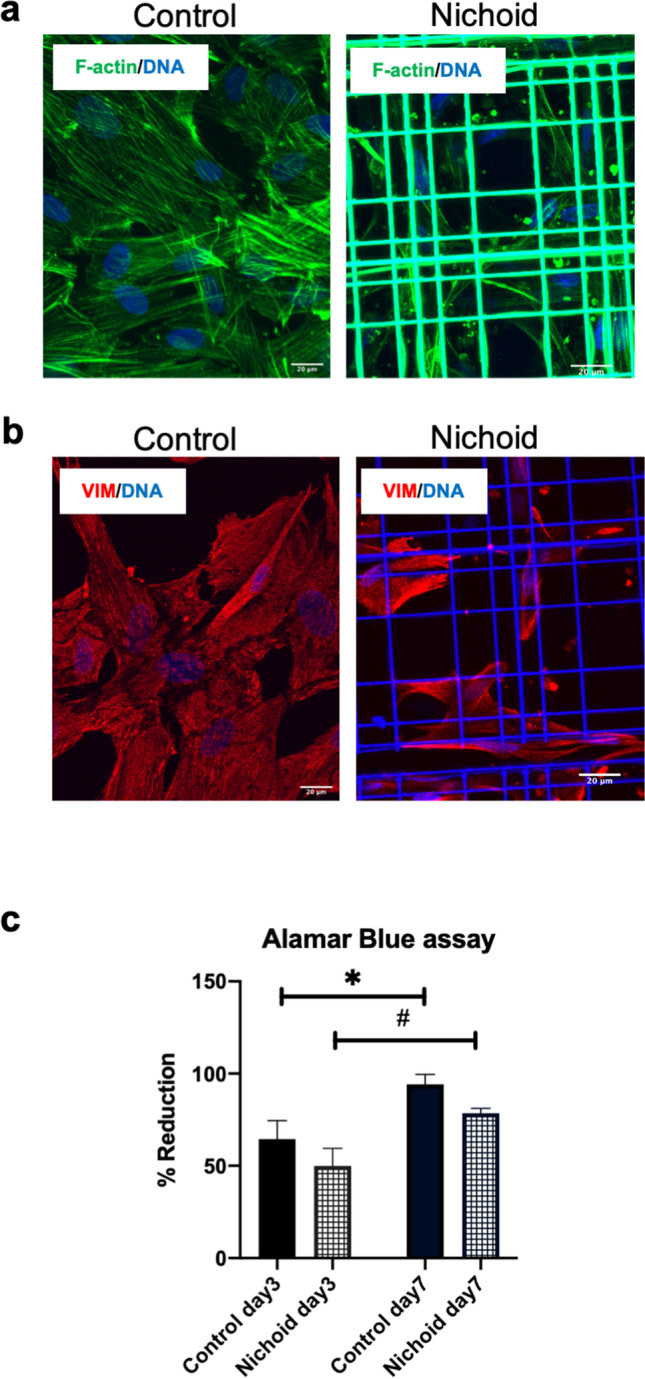

BM-MSCs (104 /1.9 cm2) were cultured inside the Nichoid scaffold and in standard conditions (used as control) for 7 days and then fixed for immunofluorescence analysis. In Fig. 1a, nuclei are stained in blue (Hoechst), and alpha-actin filaments are stained in green using Phalloidin-FITC, giving a qualitative information on the distribution of alpha-actin filaments. BM-MSCs grown on the flat substrate have a highly organized and large cytoskeleton, characterized by the presence of orientated filaments along the entire body of the cell. Nichoid-expanded BM-MSCs exhibit a different cytoskeletal organization: alpha-actin filaments are thin and form a more enhanced cortical actin network in comparison to cells in control conditions (Fig. 1a). These observations demonstrate that the geometrical and physical constrains of the Nichoid affect BM-MSCs morphology. In Fig. 1b, the positivity to Vimentin staining, a mesenchymal cytoskeletal marker, demonstrates that BM-MSCs maintain the mesenchymal feature when expanded inside the Nichoid, showing that the maintenance inside the 3D micro-scaffold does not determine spontaneous differentiation. In order to evaluate the viability of BM-MSCs grown inside the Nichoid, a metabolic Alamar Blue assay was performed. The Alamar Blue solution was incubated at 3 and 7 days after seeding (please see the “Materials and Methods” for details). As reported in Fig. 1c, there is a significative increase in metabolic activity from day 3 to day 7 with a comparable trend both in 3D and flat conditions. At day 3, the reduction levels of control cells and Nichoid-expanded cells were 64.49 ± 20.18% and 49.91 ± 18.96%, respectively. At day 7, the measured reduction value was 94.20 ± 13.30% for control cells and 78.51 ± 5.97% for Nichoid cells. The high metabolic activity levels observed in BM-MSCs grown inside the Nichoid for 7 days suggest that the structure does not alter the viability of the cells. The synthetic niche is thus suitable for the expansion of BM-MSCs.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of BM-MSCs growth inside the Nichoid. a Immunofluorescence images of alpha-actin filaments in green (Phalloidin FITC) and nuclei in blue (Hoechst) in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid and 2D control. b Immunofluorescence analysis of mesenchymal cytoskeletal Vimentin (red) and nuclei in blue (Hoechst) in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid and control standard conditions. Scale bar: 20 μm. c Alamar Blue assay of BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid and in control condition at day 3 and day 7 after seeding. Data are expressed as mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *p < 0.05 control day 3 vs control day 7. #p < 0.05 Nichoid day 3 vs Nichoid day 7

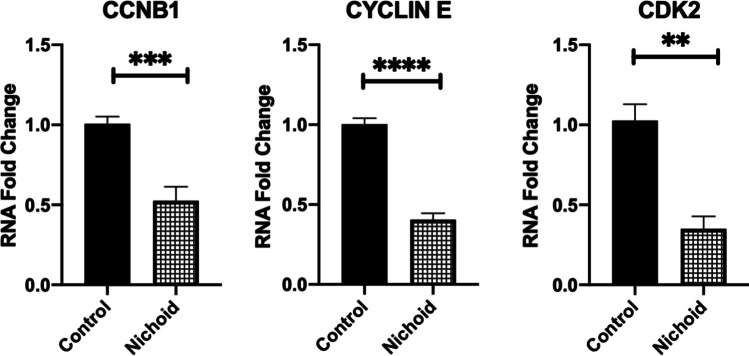

Moreover, the expression of cell cycle markers was assessed by real-time PCR to evaluate how BM-MSCs’ proliferation differs inside the Nichoid with respect to the control condition. Specifically, we analyzed different checkpoints in the cell cycle such as cyclin B1 (CCNB1), a regulatory protein involved in the control of the cell cycle at the mitosis G2/M transition [45], cyclin E1 regulator of CDK kinases essential for G1/S transition during cells cycle [46], and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) serine/threonine protein kinase regulator of progression during the cell cycle [47]. In Fig. 2, a significative downregulation of all investigated cyclins was observed in BM-MSCs grown inside the Nichoid compared to the standard conditions, suggesting a quiescence state such as the one present in the physiological stem cell niche [48, 49].

Fig. 2.

BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid show the physiological quiescent state. Cyclins markers gene expression by real-time PCR of BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid with respect to standard conditions. Data are expressed as the mean of three independent experiments with similar results ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs controls

Gene Expression of the Nichoid-Expanded BM-MSCs

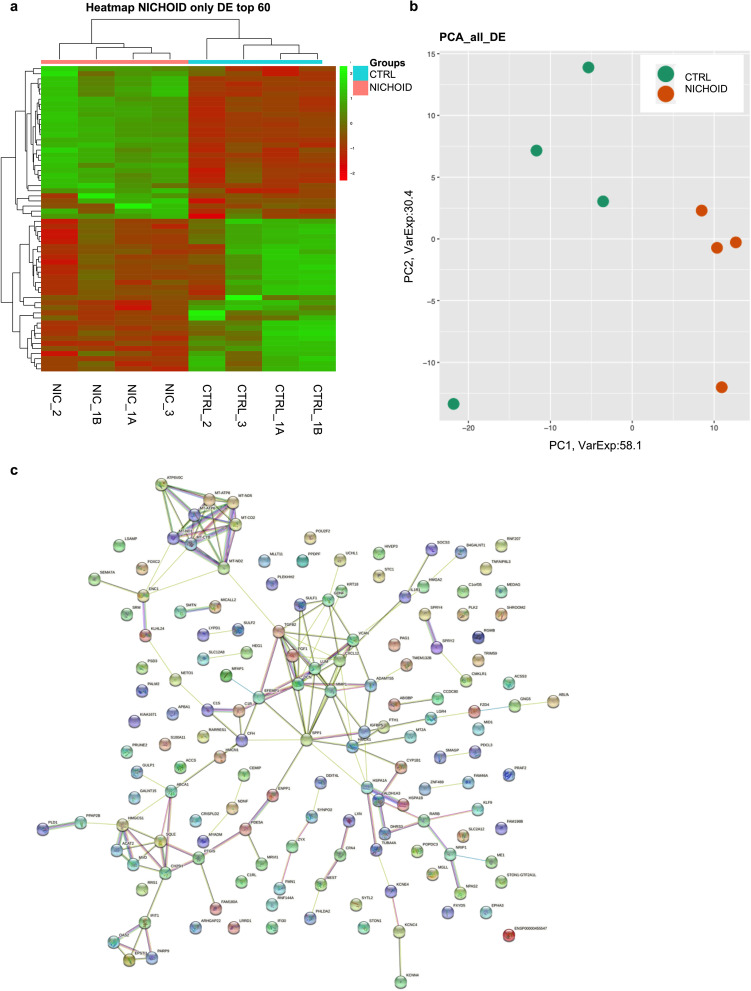

Differential gene expression in BM-MSCs grown inside the Nichoid was evaluated with respect to controls. The gene expression profiles are reported in Fig. 3: heatmap (Fig. 3a) and PCA analyses (Fig. 3b) show different expression profiles between the two conditions, suggesting the influence of the Nichoid on specific cellular features. The heatmap displays the differentially expressed genes through a color code: up-regulated genes are represented in green and down-regulated genes in red. The clustering analysis reported on the top of the heatmap divided Nichoid samples and control samples in two different “families”: Nichoid samples were colored in pink, and control samples were colored in light blue. Indeed, Nichoid samples (N = 4) were grouped together and separated from control samples (N = 4). As expected, biological replicates within each group presented similar expression profiles, as shown by the color code. Similarly, PCA analysis of the DE RNAs in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid showed different expression profiles. Nichoid samples (orange) were grouped together and were well separated from control samples (green). Finally, all deregulated genes were subjected to a network STRING analysis to evaluate the links, and the most connected dysregulated gene is fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) in Fig. 3c.

Fig. 3.

Transcriptome profile in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid vs standard conditions. a Expression profiles of differently expressed genes in Nichoid-grown BM-MSCs vs standard conditions reported as a heatmap. We considered as differentially expressed only genes showing |log2(Nichoid samples/Control samples)|≥ 1 and a False Discovery Rate ≤ 0.1; up-regulated genes are represented in green and down-regulated genes in red. b Expression profiles of significative differently expressed genes in Nichoid-grown BM-MSCs vs standard conditions reported as principal component analysis (PCA). c STRING interaction network based on significative deregulated genes where the nodes are proteins, and the edges represent the predicted functional connections. The combined score is computed by considering the probabilities from the different evidence channels corrected for the probability of randomly observing an interaction

Moreover, we investigated the affected pathways related to the significantly dysregulated genes via the g:Profiler web tool. Specifically, we report the top 20 deregulated pathways found with the Reactome database, highlighting the pathways altered following BM-MSCs expansion inside the Nichoid. In Table 1, we reported the names of dysregulated pathways with the relative p-value, the total number of involved genes for the specific pathway, and the involved number of genes in our analysis. Finally, we also reported the name of specific genes that are dysregulated in the pathways. Interestingly, this analysis demonstrated an alteration in pathways related to cell metabolism and immune response.

Table 1.

Reactome top 20 deregulated pathways performed by g:Profiler web tool. The table reports the name of deregulated pathways with the relative p-value, the total number of involved genes for the specific pathway, and the involved number of genes in our analysis. The fifth column depicts the name of the specific genes dysregulated in the pathways

| Perturbated pathways | Adjusted p-value | Term size | Intersection size | Intersections |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | 9,63835E-13 | 2075 | 31 | GNG5, NPAS2,ACSS3,CEMIP,MT-ND2,PTGIS,PLD1,MVD,ABCA1,MT-CO2,MGLL,MT-ND1,HMGCS1,PARP9,MT-ATP8,MT-ND5,MT-ATP6,CH25H,VCAN,MT-CYB,HMOX1,B4GALNT1,SQLE,SRM,ACAT2,TNFAIP8L3,ME1,ENPP1,LUM,DCN,CYP1B1 |

| Metabolism of lipids | 1,82E-07 | 728 | 15 | NPAS2, ACSS3,PTGIS,PLD1,MVD,ABCA1,MGLL,HMGCS1,CH25H,B4GALNT1,SQLE,ACAT2,TNFAIP8L3,ME1,CYP1B1 |

| Respiratory electron transport, ATP synthesis by chemiosmotic coupling | 4,50E-07 | 127 | 7 | MT-ND2, MT-CO2,MT-ND1,MT-ATP8,MT-ND5,MT-ATP6,MT-CYB |

| The citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport | 1,00074E-06 | 177 | 8 | MT-ND2,MT-CO2,MT-ND1,MT-ATP8,MT-ND5,MT-ATP6,MT-CYB,ME1 |

| Immune system | 1,00074E-06 | 2041 | 19 | HSPA1B,PAG1,C1S,MT2A,ATP6V0C,TUBA4A,PLD1,CRISPLD2,SOCS3,IFIT1,CFH,OAS2,HSPA1A,IL1R1,IFI30,FTH1,MMP1,HMOX1,C1ORF35 |

| Signal transduction | 3,79281E-06 | 2514 | 15 | GNG5,PDE5A,PAG1,ARHGAP22,ALDH1A3,ATP6V0C,GDNF,TUBA4A,DHRS3,PLD1,FGF1,EPSTI1,SOCS3,ABCA1,MGLL |

| Extracellular matrix organization | 6,11705E-06 | 298 | 9 | EFEMP1,MFAP1,SPP1,VCAN,MMP1,LUM,ADAMTS5,TGFB2,DCN |

| Cholesterol biosynthesis | 9,25359E-06 | 24 | 4 | MVD,HMGCS1,SQLE,ACAT2 |

| Metabolism of steroids | 3,23404E-05 | 148 | 6 | PTGIS,MVD,HMGCS1,CH25H,SQLE,ACAT2 |

| Respiratory electron transport | 5,7508E-05 | 103 | 5 | MT-ND2,MT-CO2,MT-ND1,MT-ND5,MT-CYB |

| Interferon gamma signaling | 7,76787E-05 | 87 | 5 | MT2A,SOCS3,OAS2,IFI30,MID1 |

| Cellular responses to stimuli | 0,000101278 | 765 | 8 | NPAS2,HSPA1B,MT2A,ATP6V0C,TUBA4A,MT-CO2,HMGA2,HSPA1A |

| Interferon Signaling | 0,000207149 | 193 | 6 | MT2A,SOCS3,IFIT1,OAS2,IFI30,MID1 |

| Signaling by nuclear receptors | 0,000207149 | 291 | 7 | GNG5,ALDH1A3,DHRS3,ABCA1,NRIP1,RARB,CXCL12 |

| Neuronal System | 0,000277254 | 400 | 5 | KCNC4,APBA1,GNG5,KCNN4,TUBA4A |

| Potassium Channels | 0,000298821 | 103 | 3 | KCNC4,GNG5,KCNN4 |

| Cellular responses to stress | 0,000669883 | 751 | 7 | NPAS2,HSPA1B,ATP6V0C,TUBA4A,MT-CO2,HMGA2,HSPA1A |

| Disease | 0,000780704 | 1639 | 15 | GNG5,TUBA4A,FGF1,ABCA1,HSPA1A,PARP9,IL1R1,VCAN,PLK2,HMOX1,LUM,FZD4,ADAMTS5,DCN,CYP1B1 |

| Neutrophil degranulation | 0,000897936 | 476 | 7 | HSPA1B,ATP6V0C,PLD1,CRISPLD2,HSPA1A,FTH1,C1ORF35 |

| HSP90 chaperone cycle for steroid hormone receptors (SHR) in the presence of ligand | 0,000897936 | 57 | 3 | HSPA1B,TUBA4A,HSPA1A |

Following the pathway analysis performed on the deregulated genes, to better investigate the effect of the Nichoid on BM-MSCs gene expression profile, we focused our attention on the top 10 deregulated coding genes for log2FC values (Table 2). These genes were involved in different pathways, such as cell adhesion and morphology, enzymatic activity, and immune response (as reported in the GeneCards database).

Table 2.

Top 10 deregulated genes identified after transcriptome analysis. Gene function description was obtained from the GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/)

| Gene | Log2FC | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

EPHA3 EPH Receptor A3 |

2.28 | It belongs to the ephrin receptor subfamily of the protein-tyrosine kinase family. The encoded protein is a receptor tyrosine kinase that leads to contact-dependent bidirectional signaling into neighboring cells. It is involved in the regulation of cell–cell adhesion, cytoskeletal organization, and cell migration |

|

ACSS3 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Short Chain Family Member 3 |

2.14 | It encodes a protein that catalyzes the synthesis of acetyl-CoA from short-chain fatty acids. It is a key enzyme for the activation of propionate metabolism, and it is required for acetate utilization and histone acetylation |

|

PAG1 Phosphoprotein Membrane Anchor With Glycosphingolipid Microdomains 1 |

2.03 | It encodes a type III transmembrane adaptor protein that binds to the tyrosine kinase csk protein. It is thought to be involved in the regulation of T-cell activation. It promotes cytoskeletal activation and recruitment to lipid rafts. It may be involved in cell adhesion signaling |

|

RHGAP22 Rho GTPase Activating Protein 22 |

2.02 | It encodes a member of the GTPase activating protein family which activates a GTPase belonging to the RAS superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins |

| RP11-20I23.1 | 2.02 | It encodes a protein with a conserved domain, referred to as the TBC domain, characteristic of proteins which interact with GTPases. TBC domain proteins may serve as GTPase- activating proteins for a particular group of GTPases involved in the regulation of membrane trafficking |

|

RARRES1 Retinoic Acid Receptor Responder 1 |

− 2.64 | It is identified as a retinoid acid (RA) receptor-responsive gene. It encodes a type 1 membrane protein, which is an inhibitor of the cytoplasmic carboxypeptidase AGBL2. It may regulate the alpha-tubulin tyrosination cycle |

|

APBA1 Amyloid Beta Precursor Protein Binding Family A Member 1 |

− 2.70 | It encodes a member of the X11 protein family. It is a neuronal adapter protein that interacts with the Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein (APP). It is also regarded as a putative vesicular trafficking protein in the brain that can form a complex with the potential to couple synaptic vesicle exocytosis to neuronal cell adhesion |

|

MEST Mesoderm Specific Transcript |

− 2.78 | It encodes a member of the alpha/beta hydrolase superfamily. The encoded protein may play a role in development. It is a distinct gene associated with adipocyte differentiation and proliferation |

|

KCNC4 Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily C Member 4 |

− 2.92 | It encodes components of voltage-gated potassium channels. This protein mediates the voltage-dependent potassium ion permeability of excitable membranes |

|

LSAMP Limbic System Associated Membrane Protein |

− 3.33 | It encodes a member of the immunoglobulin LAMP, OBCAM and neurotrimin (IgLON) family of proteins. It mediates selective neuronal growth and axon targeting. It contributes to the guidance of developing axons and neural growth in the limbic system |

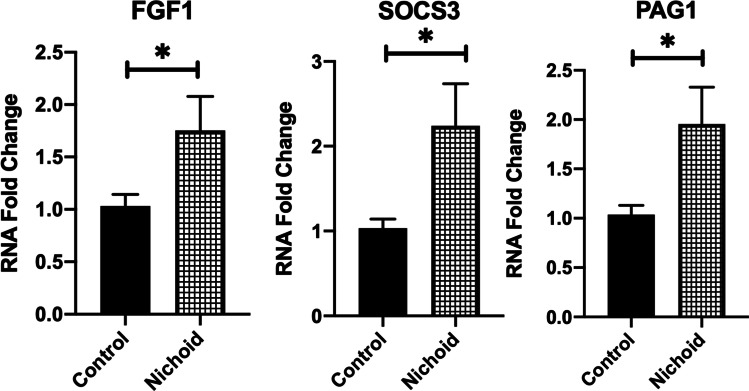

Finally, to validate RNA-seq analysis by real-time PCR, we selected three important genes implicated in the regulation of key cellular features. FGF1 resulted significatively up-regulated in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid with respect to controls (Fig. 4). This gene is involved in cell survival activities, such as cell growth, morphogenesis, tissue repair, tumor growth, and invasion. At the same time, two other genes implicated in the immune response and suppression of cytokine signaling were analyzed to validate RNA-seq analysis. PAG1, one of the most deregulated genes involved in T-cell activation and in immune system pathways, resulted up-regulated. Moreover, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), part of the previous presented IL-18 and interferon gamma pathways, resulted significantly up-regulated in BM-MSCs from Nichoid with respect to control conditions.

Fig. 4.

Validation of transcriptomic profile between BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid vs standard conditions. Genes involved in immunomodulatory pathways were analyzed by real-time PCR in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid with respect to control standard conditions. Data are expressed as the mean of three independent experiments with similar results ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs control

Discussion and Conclusion

Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated the beneficial effects of MSCs in the treatment of chronic, autoimmune, and auto-inflammatory diseases, including lung disorders [50]. In this work, the limits of 2D standard expansion were overcame exploiting the 3D scaffold Nichoid. BM-MSCs were fully characterized through several techniques, and it was demonstrated that the Nichoid mimics the physiological stem niche, maintaining the stem cell potential. Indeed, recent works demonstrate the stemness maintenance of neural stem cells of murine origin [35, 51, 52], but in this work, for the first time, we characterized human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells growth inside the Nichoid with a specific focus on the anti-inflammatory gene expression profile.

BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid created an actin cortex at the cell-grid interface and the consequent focal adhesions formation simulated an ex-vivo physiological niche, as previously demonstrated by Jacchetti et al. with rat mesenchymal stem cells [53]. Moreover, the Vimentin staining, a mesenchymal stem marker, was still present in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid, demonstrating that MSCs culture inside the Nichoid do not undergo spontaneous differentiation. The effects of the synthetic niche on the metabolic activity of BM-MSCs were studied, and a comparable increase in metabolic activity was observed in both culture conditions, suggesting that the synthetic niche is suitable for BM-MSCs culture. We highlighted a decreasing trend in the metabolic activity for BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid with respect to the control condition. This is also concordant with results obtained on cyclins mRNA expression by real-time PCR analysis. Indeed, BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid expressed significant lower levels of cell cycle positive regulators (cyclin E, CDK2, and CCNB1) with respect to the control condition. The downregulation of these genes indicated the cell cycle arrest at the G0 phase [54–56]. It has already been demonstrated that stem cells remain in a reversible quiescent state inside the stem niche, preserving the self-renewal potential [48, 49, 57, 58]. Indeed, BM-MSCs did not over-proliferate and remained in a quiescent state inside the synthetic niche, preserving stemness potential and preventing spontaneous differentiation, confirming the potential application of the Nichoid for stem cell expansion.

In order to acquire more in-depth insights over the effects of the Nichoid on cellular responses, a transcriptome analysis via RNA sequencing was performed. This technique allowed to observe significative differential gene profiles between BM-MSCs expanded in the micro-scaffold and the respective bidimensional controls. Deregulated genes were involved in several cellular pathways, including metabolism, morphology, enzymatic activity, and immune response, corroborating the hypothesis of a better response for cells expanded inside the Nichoid with respect to control condition. RNA sequencing revealed the Nichoid’s ability to impact on gene expression of BM-MSCs without the use of any chemical or xenogeneic factor, guaranteeing the safety of 3D scaffold-expanded cells.

A significative up-regulation of FGF1, SOCS3, and PAG1 in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid with respect to the control condition was observed. FGF1 is of critical importance in regulating stem cell pluripotency [59]. Indeed, FGF/FGFR signaling implicates fundamental cellular processes such as metabolism, cell survival, proliferation, migration, differentiation, embryonic development, and tissue regeneration. In 2017, Ghazavi et al. investigated the effect of intravenous administration of FGF1 transfected adipose-derived (AD)-MSCs for stroke therapy, observing a significant improvement of neurological functions and an increased density of FGF1 protein in the peri-infarct area [60]. At the same time, Liu et al. demonstrated that SCs could inhibit Th17 cell differentiation through the activation of SOCS3 suppressors, suggesting a possible mechanism through which MSCs could reduce pathological manifestations of some autoimmune diseases [61]. Finally, PAG1, which affected immune receptor signaling in T and B cells, was up-regulated and limited the inflammation effect. Indeed, Ullah et al. demonstrated that the PAG1 deficiency predisposed toward allergic sensitization and airways inflammation [62]. The results of gene up-regulation in BM-MSCs expanded inside the Nichoid, in agreement with the above-reported studies, suggest the improvement of the cells’ anti-inflammatory effects, possibly potentiating the therapeutic outcome of BM-MSCs. Although the injection of these targets has anti-inflammatory effects in several diseases and tumor suppression activity, possible side effects such as an over-proliferation stimulation could occurred [63]. However, a physiological production of these anti-inflammatory targets induced only by mechanical stimulation instead of a chemical and exogenous administration could reduce the possible side effects, potentially enhancing the stem cells’ safety. Moreover, preclinical and clinical results support the use of MSCs for therapeutic treatment also in lung diseases [9, 11], and in this work, the exploitation of the Nichoid could be a next ameliorating step for cell therapy production and hence clinical translation. Indeed, our results support the use of a 3D synthetic niche for the expansion of MSCs to render cellular and acellular products more suitable for clinical applications. These preclinical in vitro findings underline the possible clinical translation of the use of micro-scaffold as an MSCs culture expansion system for the future treatment of pediatric congenital and acquired pulmonary disorders, including post-COVID lung manifestations. To reach this important aim, more investigations, including in vivo experimental models, are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Pediatric Clinical Research Centre Fondazione “Romeo ed Enrica Invernizzi” and Neurogel En Marche Foundation.

Author Contribution

BB: experiments design, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and revision. SC: conceptualization of the study, experiments design, monitoring of project development, data interpretation, draft writing, and revision. LM and FR: RNA-seq, bioinformatic analysis, and data interpretation. MAA: cell culture expansion. EJ: monitoring of IF analysis and acquisition. EM and CB: support in experimental validation. MTR: supervision of the work, draft revision, and financial support. GZ, CC, VC, and GP: draft revision and financial support. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Italian Ministry of Research (MUR, FISR-COVID project LUNGCHILDMSC, G.A. FISR2020IP_02959).

Data Availability

Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing Interests

MTR is a co-founder of the university spin-off company MOAB Srl and holds shares. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bianca Barzaghini and Stephana Carelli contributed equally to the work.

References

- 1.Lau AN, Goodwin M, Kim CF, Weiss DJ. Stem cells and regenerative medicine in lung biology and diseases. Mol Ther. 2012;20(6):1116–1130. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simones AA, Beisang DJ, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Roberts KD. Mesenchymal stem cells in the pathogenesis and treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a clinical review. Pediatr Res. 2018;83(1–2):308–317. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hipp J, Atala A. Sources of stem cells for regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Rev. 2008;4(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s12015-008-9010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggenhofer E, Luk F, Dahlke MH, Hoogduijn MJ. The life and fate of mesenchymal stem cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:148. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.le Blanc K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(5):383–396. doi: 10.1038/nri3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kallmeyer K, Pepper MS. Homing properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15(4):477–479. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.997204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afarid M, Sanie-Jahromi F. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and COVID-19: Cure, Prevention, and Vaccination. Stem Cells Int. 2021:2021:6666370. 10.1155/2021/6666370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Jayaramayya K, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem-cell-derived exosomes for COVID-19 treatment. BMB Rep. 2020;53(8):400. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2020.53.8.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelizzo G, Silvestro S, Avanzini MA, Zuccotti G, Mazzon E, Calcaterra V. Mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of interstitial lung disease in children: a look from pediatric and pediatric surgeon viewpoints. Cells. 2021;10(12). MDPI. 10.3390/cells10123270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Pelizzo G, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells for cutaneous wound healing in a rabbit model: pre-clinical study applicable in the pediatric surgical setting. J Transl Med. 2015;13:219. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0580-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelizzo G, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells: novel therapeutic option for mutated FLNA-associated respiratory failure in the pediatric setting. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(1):190–197. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nathan N, Berdah L, Delestrain C, Sileo C, Clement A. Interstitial lung diseases in children. Presse Med. 2020;49(2):103909. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clement A, Nathan N, Epaud R, Fauroux B, Corvol H. Interstitial lung diseases in children. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5(1):1–24. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bijonowski BM, Yuan X, Jeske R, Li Y, Grant SC. Cyclical aggregation extends in vitro expansion potential of human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20448. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77288-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takai H, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. DNA damage foci at dysfunctional telomeres. Curr Biol. 2003;13(17):1549–1556. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams RL, et al. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1988;336(6200):684–687. doi: 10.1038/336684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikolits I, Nebel S, Egger D, Kreß S, Kasper C. Towards physiologic culture approaches to improve standard cultivation of mesenchymal stem cells. Cells. 2021;10(4). 10.3390/cells10040886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Harris AR, Walker MJ, Gilbert F. Ethical and regulatory issues of stem cell-derived 3-dimensional organoid and tissue therapy for personalised regenerative medicine. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Kadiry AE, Rafei M, Shammaa R. Cell Therapy: Types, Regulation, and Clinical Benefits. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:756029. 10.3389/fmed.2021.756029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Chen P, et al. Desktop-stereolithography 3D printing of a radially oriented extracellular matrix/mesenchymal stem cell exosome bioink for osteochondral defect regeneration. Theranostics. 2019;9(9):2439. doi: 10.7150/thno.31017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-loaded thermosensitive hydroxypropyl chitin hydrogel combined with a three-dimensional-printed poly (ε-caprolactone)/nano-hydroxyapatite scaffold to repair bone defects via osteogenesis, angiogenesis and immunomodulation. Theranostics. 2020;10(2):725. doi: 10.7150/thno.39167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong L, et al. MSC-derived immunomodulatory extracellular matrix functionalized electrospun fibers for mitigating foreign-body reaction and tendon adhesion. Acta Biomater. 2021;133:280–296. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raimondi MT, et al. Three-dimensional structural niches engineered via two-photon laser polymerization promote stem cell homing. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(1):4579–4584. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nava MM, et al. Synthetic niche substrates engineered via two-photon laser polymerization for the expansion of human mesenchymal stromal cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;11(10):2836–2845. doi: 10.1002/term.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nava MM, et al. Two-photon polymerized ‘nichoid’ substrates maintain function of pluripotent stem cells when expanded under feeder-free conditions. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0387-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remuzzi A et al. Effect of the 3D Artificial Nichoid on the morphology and mechanobiological response of mesenchymal stem cells cultured in vitro. Cells. 2020;9(8). 10.3390/cells9081873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Raimondi MT, Eaton SM, Nava MM, Laganà M, Cerullo G, Osellame R. Two-photon laser polymerization: from fundamentals to biomedical application in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. J Appl Biomater Funct Mater. 2012;10(1):55–65. doi: 10.5301/JABFM.2012.9278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricci D, Nava MM, Zandrini T, Cerullo G, Raimondi MT, Osellame R. Scaling-up techniques for the nanofabrication of cell culture substrates via two-photon polymerization for industrial-scale expansion of stem cells. Materials (Basel). 2017;10(1). 10.3390/ma10010066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Jacchetti E, et al. The nuclear import of the transcription factor MyoD is reduced in mesenchymal stem cells grown in a 3D micro-engineered niche. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81920-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carelli S, et al. Neural precursors cells expanded in a 3D micro-engineered niche present enhanced therapeutic efficacy in vivo. Nanotheranostics. 2021;5(1):8–26. doi: 10.7150/ntno.50633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rey F, et al. Dissecting the effect of a 3D microscaffold on the transcriptome of neural stem cells with computational approaches: a focus on mechanotransduction. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):1–37. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Messa L et al (2021) Neural precursor cells expanded inside the 3D micro-scaffold Nichoid present different non-coding RNAs profiles and transcript isoforms expression: possible epigenetic modulation by 3D growth. Biomedicines 9(9). 10.3390/biomedicines9091120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Avanzini MA, et al. Generation of mesenchymal stromal cells in the presence of platelet lysate: a phenotypic and functional comparison of umbilical cord blood-and bone marrow-derived progenitors. Haematologica. 2009;94(12):1649. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.006171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zandrini T, Shan O, Parodi V, Cerullo G, Raimondi MT, Osellame R. Multi-foci laser microfabrication of 3D polymeric scaffolds for stem cell expansion in regenerative medicine. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11761. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48080-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carelli S, et al. Neural precursors cells expanded in a 3D micro-engineered niche present enhanced therapeutic efficacy. Nanotheranostics. 2021;5(1):8–26. doi: 10.7150/ntno.50633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rampersad SN. Multiple applications of Alamar Blue as an indicator of metabolic function and cellular health in cell viability bioassays. Sensors. 2012;12(9):12347–12360. doi: 10.3390/s120912347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu A, Ibrahim JG, Love MI. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(12):2084–2092. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pratt D, et al. NDEx, the network data exchange. Cell Syst. 2015;1(4):302–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen EY, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuleshov MV, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dominici M, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li B, et al. Regulating the CCNB1 gene can affect cell proliferation and apoptosis in pituitary adenomas and activate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(5):4651–4658. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Möröy T, Geisen C. Cyclin E. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(8):1424–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fagundes R, Teixeira LK. Cyclin E/CDK2: DNA replication, replication stress and genomic instability. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:774845. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.774845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hicks MR, Pyle AD. The emergence of the stem cell niche. Trends Cell Biol. 2023 ;33(2):112–123. 10.1016/j.tcb.2022.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.van Velthoven CTJ, Rando TA. Stem cell quiescence: dynamism, restraint, and cellular idling. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24(2):213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ullah I, Subbarao RB, Rho GJ. Human mesenchymal stem cells - current trends and future prospective. Biosci Rep. 2015;35(2). 10.1042/BSR20150025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Rey F et al (2020) Dissecting the Effect of a 3D Microscaffold on the transcriptome of neural stem cells with computational approaches: a focus on mechanotransduction. Int J Mol Sci 21(18). 10.3390/ijms21186775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Messa L et al (2021) Neural precursor cells expanded inside the 3d micro-scaffold nichoid present different non-coding rnas profiles and transcript isoforms expression: possible epigenetic modulation by 3d growth. Biomedicines 9(9). 10.3390/biomedicines9091120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Jacchetti E, et al. The nuclear import of the transcription factor MyoD is reduced in mesenchymal stem cells grown in a 3D micro-engineered niche. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81920-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gulaia V, et al. Molecular mechanisms governing the stem cell’s fate in brain cancer: factors of stemness and quiescence. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:388. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rumman M, Dhawan J, Kassem M. Concise review: quiescence in adult stem cells: biological significance and relevance to tissue regeneration. Stem Cells. 2015;33(10):2903–2912. doi: 10.1002/stem.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rumman M, et al. Induction of quiescence (G0) in bone marrow stromal stem cells enhances their stem cell characteristics. Stem Cell Res. 2018;30:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116(6):769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marescal O, Cheeseman IM. Cellular mechanisms and regulation of quiescence. Dev Cell. 2020;55(3):259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mossahebi-Mohammadi M, Quan M, Zhang J-S, Li X. FGF signaling pathway: a key regulator of stem cell pluripotency. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:79. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghazavi H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor type 1 (FGF1)-overexpressed adipose-derived mesenchaymal stem cells (AD-MSC(FGF1)) induce neuroprotection and functional recovery in a rat stroke model. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2017;13(5):670–685. doi: 10.1007/s12015-017-9755-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu X, Ren S, Qu X, Ge C, Cheng K, Zhao RCH. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit Th17 cells differentiation via IFN-γ-mediated SOCS3 activation. Immunol Res. 2015;61(3):219–229. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ullah MA, et al. PAG1 limits allergen-induced type 2 inflammation in the murine lung. Allergy. 2020;75(2):336–345. doi: 10.1111/all.13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun Y, Fan X, Zhang Q, Shi X, Xu G, Zou C. Cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete FGF-1 to promote ovarian proliferation, migration, and invasion through the activation of FGF-1/FGFR4 signaling. Tumor Biology. 2017;39(7):1010428317712592. doi: 10.1177/1010428317712592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request.