Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Describe the components of a biological signal processing system and how they connect together.

-

•

Know how the outputs from physiological electrodes and transducers are processed and amplified.

-

•

Explain how simple filters work and why they are important in a system.

-

•

Understand the process of converting physiological signals into digital ones.

Key points.

-

•

Physiological electrodes produce very small outputs and must be amplified carefully.

-

•

Transducers are used to convert physiological signals into electrical signals that must be amplified and processed carefully.

-

•

Filters are important in signal processing and can be high pass or low pass.

-

•

Amplifiers used to process physiological signals must use differential inputs.

-

•

Signals can be converted to digital ones using analogue-to-digital converters.

This is the third paper in a series on electricity in this journal and links with the previous related articles.1,2 It examines the effect of connecting components together to form building blocks that can be used for biological signal processing. The processing of the signals can be carried out in the analogue or digital domains. The basic processing system is shown in Fig. 1, and all the functions are discussed in this review. The reader is referred to standard texts on the topic for further details.3

Fig 1.

Biological processing block diagram showing the path from electrodes or transducer, to amplifier, filter, process and then converting the signal to digital form. ADC, analogue-to digital-converter. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

Electrodes and transducers

Physiological electrodes

Electrodes that are applied directly to the human body are used both for the measurement of bioelectric events and to deliver current to living tissue in the form of stimulation (or diathermy). An electrode normally has direct contact, via an electrolyte, to the tissue.

When a metallic electrode comes into contact with an electrolyte (a conductive gel), an electrochemical reaction occurs, which resembles three components connected in series: a voltage output source, a capacitor and a resistor. Many different metal combinations can be used, but the silver–silver chloride electrode pair has many advantages. It has good stability, low drift, low noise and a low impedance, and this is why it is commonly used.

The electrodes used on humans must be connected to a suitable biological amplifier as their voltage output is very small. The total impedance of both the electrode impedance and the electrode–skin impedance must be much lower than the amplifier input impedance in order to maximise the transfer of physiological signal from the body and to minimise signal distortion. The total electrode impedance (skin plus electrode) can be thought of as a series resistor (Relectrode) with the physiological signal generator as in Fig. 2. The combination of the electrode-related impedance and the amplifier input resistance (Ramplifier) form a voltage divider. As the electrode resistance becomes lower than the amplifier input resistance, then the voltage across the amplifier input will be similar to the signal source voltage. It is also important to make the electrode impedance as low as possible so that the induced interference voltage (normally domestic mains) is as low as possible. As V=IR, where I is the induced interference current (transmitted from the mains equipment by stray capacitance, which is explained in the differential amplifier section below) and R is the electrode impedance, then to get the lowest V, R should be low. Reducing the mains interference (lowering I) by switching off the equipment, increasing the distance from mains powered equipment and using battery-powered equipment will also help. The method of decreasing the skin–electrode impedance is to abrade the skin with a coarse cleaning paste and clean to skin with alcohol before applying the electrodes. This reduction in impedance also gives a reduction in motion artefacts.

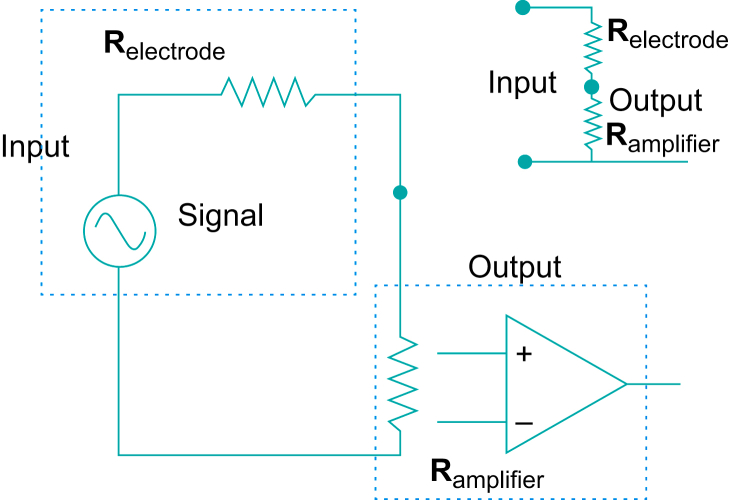

Fig 2.

Diagram of a physiological signal generator plus series electrode resistance (Relectrode) plus amplifier input resistance (Ramplifier). The voltage divider is formed by the combination of the two resistances with the signal being the input voltage, and the output voltage being the voltage across the amplifier. This equivalent circuit is also shown in the diagram in the top right. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

Transducers

Biomedical transducers are used to convert physiological signals to analogue electrical signals, and these then can then be processed, either by analogue means or after digital conversion, in the digital domain.

Transducers come in many forms. The majority are found in the following classes: resistive, inductive, capacitive, photoelectric, piezoelectric, thermoelectric and chemical.

The variation of resistance has been used extensively to convert temperature and mechanical displacement (pressure) to electrical signals. The resistance of a conductor is dependent on the material, the geometric configuration and the temperature. The choice of material is dependent on its linearity or sensitivity for that purpose. The resistance transducers have a wide range of uses in medicine, from thermometers and thermistors to pressure (resistive) transducers. A blood pressure transducer is a good example, shown in Fig. 3. The transducer is connected to the amplifier or processing circuits via a bridge circuit, shown in Fig. 4.

Fig 3.

Diagram of a typical blood pressure transducer which uses resistive strain gauges. The pressure moves the diaphragm back and forth, which causes the strain gauges to be compressed or expanded. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

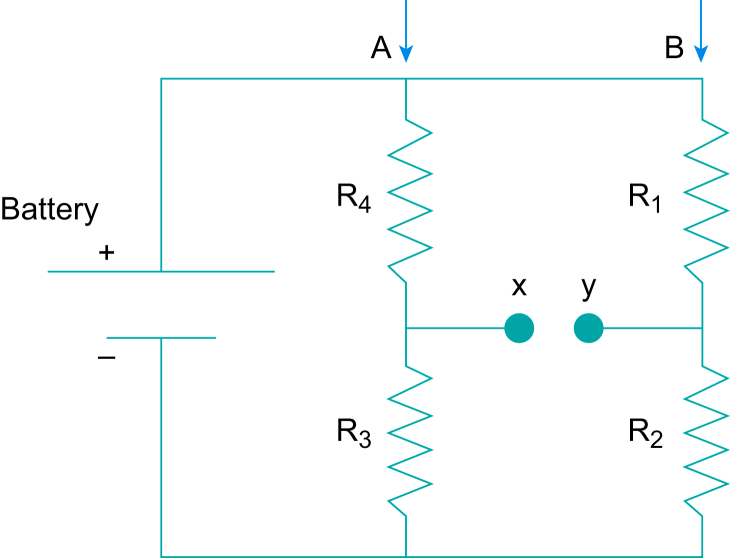

Fig 4.

A bridge circuit. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

Bridge circuits

The circuit shown can be thought as two voltage dividers in parallel (A and B in the diagram). If R1=R4 and R3=R2, then both points x and y will be at the same potential. Both voltage dividers A and B will divide the battery voltage by the same amount, the voltage difference between x and y will be zero, that is the bridge is in balance. If R3 is replaced with an unknown resistance such as the resistance strain gauge in this example, then R2 can be substituted with a variable resistance, similar in value to the R3, which can be adjusted so that the voltage difference between x and y is zero, and the bridge can be balanced. A very small pressure change, which results in a very small change in resistance can be detected and further amplified. The bridge in effect balances out the resting potential (which can be a large voltage).

Inductive transducers are also used in medicine. The inductance can be changed by the movement of an inductance core inside a coil, caused, for example by a blood pressure wave in a similar way to the resistive-based transducer. The change in inductance can be measured and further processed. Capacitive transducers are another alternative. These can be very accurate, sensitive and linear but require complex driving electronics. A capacitor consists of two conducting surfaces separated by an insulator. The distance between the plates can be changed by, for example the blood pressure wave.

Photoelectric transducers are also used in medicine, and consist of photovoltaic cells, photoconductive cells, and phototransistors/diodes. The most well-known use of the phototransistor or light emitting diode is in pulse oximetry.4

Piezoelectric transducers rely on the effect of certain materials which develop a voltage difference across them when a pressure is applied or the material is distorted in some way and vice versa. These transducers are used particularly in ultrasound and can be used to detect blood pressure and body sounds, and are used as accelerometers.5

Chemical transducers play an important role in the assessment of metabolism. There are two main types: those that measure chemical composition of the blood, tissue and organ fluids, and those that measure the composition of the respiratory gases. Many chemical transducers are electrochemical cells in which the quantity to be measured causes a change in cell potential or a change in current through the cell.6

Biological signal processing

Frequency response

Signals from electrodes and transducers can be contaminated by noise, artefacts and other issues such as baseline wander (low frequency artefacts caused by movement or respiration) and drift (low frequency artefacts caused by electronic issues). The physiological signals are each comprised of range of frequencies. This can be analysed as a fundamental frequency (a sine wave) and a number of harmonics (multiples of the fundamental) which decrease in amplitude as the frequency increase, until lost in the noise. Ideally the processing system needs to amplify and process exactly those frequencies contained in the signal and nothing else, removing the electrical contamination. This can be partly done by using filters.

Filters

Low pass filters remove the higher frequency components above its cut-off (and pass the lower ones) and high pass filters remove the low frequency components below its cut-off. The ideal is for the low pass filter's cut-off to be set at the highest frequency of interest of the biological signal, and the high pass to be set at exactly the lowest. Filters can be complex, can be analogue or digital, but simple analogue versions can describe the mode of operation. A simple analogue low pass filter is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig 5.

A simple low pass filter. This shows a square wave input and resultant output across the capacitor. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

If a square wave, Vinput, is applied to the resistor capacitor network shown in Fig. 5, the capacitor charges up on the rising edge of the input with a time constant t equal to the product of the resistance (R measured in Ω) and the capacitance (C in Farads), t=RC, and the output voltage will be Vouput=Vinput(1−e–t/RC). When the square wave is in the off state, or 0 V, the voltage will decrease exponentially with the same time constant. It can be seen from the diagram that, with the appropriate values of R and C, the output from the network is a filtered version of the input.

This RC network is a simple first-order low-pass filter removing the high frequency components of the square wave and letting the low frequency parts through. The cut-off frequency of this filter is the frequency value above which there is attenuation of higher frequencies. Below the cut-off value, the filter lets all frequency values through with no attenuation, and above that value the frequencies are attenuated. If this filter had the cut-off frequency low enough, the output wave would appear like a sine wave, as only the fundamental harmonic of the square wave would be let through, which is purely a sine wave. The cut-off frequency of the filter is f=1/2RC. Above the cut-off frequency, the output voltage due to the filter action is reduced by half every time the input frequency is doubled. This type of filter could be useful in filtering EEG signals, so that the higher frequency noise, such as muscle signals, is prevented from passing through the filter.

If the resistor and capacitor are interchanged, then this circuit will behave very differently. It will block a DC input but will pass high frequencies with little attenuation. Again, the input frequency at which this situation changes is given by the time constant. This CR combination is called a high pass filter.

In order for all these circuits to function, the output Vout must have minimal load (or resistance) across it. This is impossible in real situations – the circuit must be connected to something or connected to a special non-loading interface (a buffer). This special interface or buffer can be provided by using operational amplifiers.

Amplifiers

Operational amplifiers

Integrated circuits which contain operational amplifiers have largely replaced the transistor as building blocks in electronics circuits. They can be made to provide amplification (where output/input >1), attenuation, filtering, oscillators and many other functions. The operational amplifier is contained typically in an eight-pin (legs), mini dual-in-line package containing hundreds of tiny electronic components. It provides very high amplification on its own (>106) and has an extremely high input resistance (>106), which means it does not load or draw any significant current from the preceding circuit. Its inputs are also differential, that is it will only amplify a voltage difference not an absolute voltage. The performance of operational amplifiers is ‘controlled’ by feedback, which is achieved by connecting the output to the input, usually by a resistor or capacitor, which enables the designer to determine the gain and stability of the circuit.

The amplifier circuits can be added to the simple RC circuits described earlier to provide practical filtering circuits. However, such filters are inefficient because they filter typically only a quarter of the signal amplitude after the signal frequency has been doubled. The ideal filters would attenuate totally the signal amplitude directly after the cut-off frequency. Complicated circuits containing many operational amplifiers are required to produce efficient filters that are near the ideal case.

Single-ended amplifiers

As biological electrical signals, or signals that originate from transducers, are very small in magnitude, they need to be amplified by an amplifier, which provides voltage gain (output voltage/input voltage). The simplest amplifier is single-ended where there is one input terminal and one output terminal with a common to both input and output. A diagram is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig 6.

A single-ended amplifier in which the common ground is both one side of the input and one side of the output. It also shows the system amplifying the domestic mains voltage as well. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

This form of amplifier is suitable for audio amplification, for example from a microphone, and the output could be connected to a loudspeaker. The gain in this case can be around 1000 times, similar to that required for an ECG amplifier. If this amplifier were connected to a patient via two electrodes, then the loudspeaker would only give out mains ‘hum’ and the ECG signal would be submerged in the noise. The mains voltage from lights, etc (which is much bigger than the ECG voltage) appears at the input via a small natural capacitance as shown in Fig. 6. The amplifier will amplify this as well. Also, in this situation the patient is earthed, which is not desirable in terms of their safety. One solution would be to make the amplifier battery powered and put the patient in a completely screened room, with no mains apparatus nearby. Another solution would be to use a patient isolated differential amplifier.

Patient isolated differential amplifier

The problem in obtaining an ECG signal is that the amplifier must detect the difference in potential between the two electrodes applied to the patient whilst ignoring the induced electrical interference signals which appear equally at both electrodes (by capacitance) and are therefore common to both. A differential amplifier does this and has two inputs in addition to the common point. Three electrodes are connected to the patient. For best results, the common electrode is ideally placed at a neutral point on the body, and commonly the right leg is used for this in the ECG amplifier. The differential amplifier is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig 7.

Patient connected differential amplifier measuring the ECG, showing connection to a patient. RA, right arm; LA, left arm; RL, right leg. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

If this ECG signal, referenced to the neutral point, is applied between the positive and negative inputs of the amplifier, as shown, then the output of the amplifier will be a magnified version of the ECG. However, if one of the electrodes of the ECG signal is connected to both the positive and negative inputs at the same time, then no output will result. The mains signal will be common to both of the positive and negative inputs at the same time. At all times throughout the mains voltage cycle, the voltage, with respect to the common input, will be the same value, and so will not be amplified. The facility to ignore signals which are common to both input terminals is defined as the common mode rejection, and the manner in which the amplifier can amplify only the ECG signal and reject the common mains signals is called the common mode rejection ratio (CMRR) and is the differential signal gain/common mode signal gain. The common electrode is needed so that the ECG voltages are referred to it and are in the range of the supply of the amplifier. It could be connected to earth, which is undesirable, or it can be floating (i.e. not connected to earth). A floating or patient isolated amplifier is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig 8.

Patient isolated differential amplifier showing isolation provided by fibreoptics, and the power supply arrangements for the patient amplifier. LED, light-emitting diode. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

The supply for the patient amplifier (and modulator and associated circuits) is obtained from an isolating transformer, which is rectified (and smoothed) to produce DC. This provides isolation from the earth and mains supply. The signal output from the patient amplifier is connected to the main equipment by either an opto-isolator (as in this diagram) or another signal isolating transformer. In this way, the patient side of the equipment is totally separate from the main equipment and not earthed, but floating. The signal output from the patient connected amplifier first modulates a light beam (i.e. the signal fluctuations are impressed on the beam by using a light emitting diode), and this beam is passed through a fibreoptic cable. At the end of the cable, the light is converted back to an electrical signal by a photodiode (or similar), and then is de-modulated to bring the signal back to its original form. It is then further amplified as necessary. The output now is completely isolated from the patient.

Digital signal processing

The physiological signals can be manipulated and processed by the electronic circuits (e.g. filtered or differentiated) and then converted (or quantified) to the digital domain by an analogue-to-digital converter (ADC), and then analysed by the computer. If the signal is hidden in the noise, or very noisy, the digital signal processing can often help to improve matters. The resulting processed signal or calculated value can be displayed on a screen or used for some other function.

The advantages of digital signal processing is that once a signal, such as an ECG voltage, is converted to a series of numbers or digitised, these values cannot change, drift or become contaminated with noise. All these can be disadvantages with the analogue processes described previously.

The analogue signal is first converted to a digital value by an ADC. This device takes a snapshot or a sample of the waveform at exact time intervals, converts this analogue value to a number and sends it to the computer for storage and processing. The effect of sampling a sine wave is shown in Fig. 9, and it appears that a staircase waveform is the result. In the reconstruction, this staircase is simply low-pass filtered to give the same sine wave again. For an eight-bit system, as shown in the figure (8 units of memory, each either 0 or 1, giving values of 00000000–11111111), the sampled number is between 0 and 255. If the signal is ranging from 0 to 5 V, then the digital number produced is the signal multiplied by 255 and divided by 5. For example, 2.5 V would be 128 or 10000000 binary. Systems can have many more bits, which can give higher resolutions. For example, 16 bits will give 0–65536.

Fig 9.

Conversion of analogue signal to digital values. The diagram shows a sine wave sampled at 10 equally spaced in time points. The open circles represent a sample, and these samples will have a corresponding digital value. For example, the fifth sample in the diagram has a value of 153, the 10th has a value of 204 and the 15th a value of 51. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

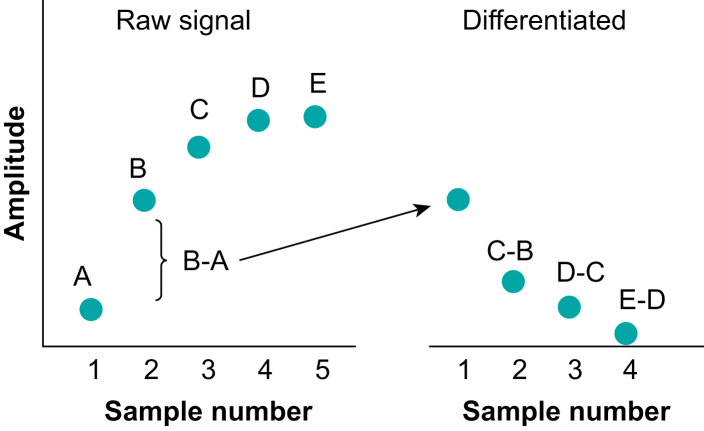

The computer can carry out numerous mathematical tasks on these digital data, which are now just a series of numbers – it can digitally filter them, low pass or high pass, differentiate or integrate them, or just measure simple parameters such as the maxima or minima of a signal in a set time frame. One example of this is a simple approximation to differentiation, when two adjacent samples are subtracted from each other. This is shown in Fig. 10, showing the raw signal and its differentiated version next to it.7 Sample A in the raw signal is subtracted from B, which gives the first sample in the differentiated version, and so on.

Fig 10.

Diagram showing the principle of digital differentiation. The raw signal consists of five samples A–E. The differentiation is carried out by taking B–A, then C–B etc. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

There are mathematical rules about how frequently samples need to be taken from a waveform so that the information of the original analogue waveform is preserved. The minimum sample rate is defined as the Nyquist rate, and this rate is greater than twice the highest frequency component of the signal being processed. At this rate all the frequency information in the original signal will be kept. If it is sampled less, frequency ‘aliasing’ occurs where low frequency components suddenly appear which are not really there. This is illustrated in Fig. 11. Of course, the signal can be sampled much higher than the Nyquist rate; this does not improve signal quality but increases the amount of data collected, and the amount of data storage needed.

Fig 11.

Diagram showing a sine wave sample at above the Nyquist rate (open circles) and below the rate (closed circles). Aliasing occurs when the sampling is too low and results in an aliased wave – a much lower frequency wave than the sampled sine wave. (Figure reproduced with permission from Magee and Tooley.3).

For further information, please refer to Chapters 4, 5, 10, 12, 15, 18,19, 20, 21 and 24 in the work of Magee and Tooley.3

Declaration of interests

The author declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Biography

Mark A. Tooley BScMSc PhD CEng CSci FInstP FIET FIPEM FRCP FREng was the head of medical physics and bioengineering and director of research and development at the Royal United Hospitals in Bath. He is an honorary professor at the University of Bath, and visiting professor at the University of the West of England. He was past president of the Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine. He was a specialist scientific advisor for NHS England, and currently a digital clinical advisor for the West of England Academic Health Science network. He is a member of the Medical Technology Advisory Committee of the National Institute for Care and Excellence. He taught for many years on physics in anaesthesia, EEG and electricity courses for anaesthetists. His interests are in depth of anaesthesia, biosignals, clinical measurement, medical simulation and innovative solutions for patients' care.

Matrix codes: 1A03, 2A04, 3J00

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

References

- 1.Tooley M.A. Electricity, magnetism and circuits. BJA Educ. 2023;2:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bjae.2022.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tooley M.A. Electrical safety, defibrillation and diathermy. BJA Educ. 2023;3:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bjae.2022.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magee P., Tooley M.A. 2nd Edn. OUP; Oxford: 2011. The physics, clinical measurement and equipment of anaesthetic practice. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds K.J., De Kock J.P., Tarassenko L., et al. Temperature dependence of the light emitting diode and its theoretical effect on the pulse oximeter. Br J Anaesth. 1991;67:638–643. doi: 10.1093/bja/67.5.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manbachi A., Cobbold R.S.C. Development and application of piezoelectric materials for ultrasound generation and detection. Ultrasound. 2011;19:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw I., Magee P. Acid base quantification. A comparison of Classical & Stewart’s approach with recent developments. BJA Educ. 2022;11:440–447. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman J.D., Bolton M.P. Microprocessor detection of electrocardiogram R-waves. J Med Eng Technol. 1979;3:235–241. doi: 10.3109/03091907909160662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]