Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in disruption in every facet of life including health service delivery. This has threatened the attainment of global targets to improve health and wellbeing of all persons. In particular, for persons living with chronic diseases, who require consistent monitoring by health professionals and medication to enhance their health, understanding how the pandemic has disruption their access to health care delivery is critical for interventions aimed at improving health service delivery for all as well as preparedness for future pandemic. This study applied the constructs of the Health Belief Model, to explore the influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health seeking behaviors of persons living with chronic diseases. The design was exploratory descriptive. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect data among persons living with chronic diseases in the Cape Coast Metropolis of Ghana. Thematic analysis, both inductive and deductive, was conducted to unearth the findings. Awareness of increased susceptibility and risk of a more severe episode if they contracted COVID-19 as a result of the existing chronic diseases was identified. Lack of access to health professionals during the peak of the pandemic as well as the fear of contracting the virus while accessing their regular chronic disease clinic was the main barriers identified. Information in the media served as cues to action for adopting preventive health strategies. Behavior modifications; dietary and lifestyle, self-medication and adoption of COVID-19 related precautions were practiced. Susceptibility to contracting COVID-19 contributed to missed adherence to treatment appointment. The health belief model was a useful framework in exploring the health seeking behavior of the adults living with chronic conditions during the COVID-19 in this study setting. Intensifying targeted education for persons living with chronic diseases will contribute to the adoption of positive health seeking behaviors during future pandemic.

Keywords: behavioral health, health promotion, qualitative methods, COVID, disease management

Introduction

Chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability worldwide and ranked the first 7 of the top 10 leading causes of deaths in 2019.1 About 15 million of these deaths are recorded among persons aged between 30 and 69 years annually, and 85% of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 The burden of chronic diseases has reached epidemic proportions in Ghana, accounting for 43% of all deaths.3 To address the global burden of chronic diseases, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 3.4 aims to reduce by one-third all premature deaths associated with chronic diseases by 2030.2

However, with the emergence of COVID-19, with its associated high infectivity and mortality rate,4 national efforts and resources have been directed toward curbing its spread, thereby disrupting the healthcare priority agenda, including those directed toward chronic diseases. The pandemic has caused disruptions to essential health services in over 90% of countries including Ghana; impacting routine care for chronic diseases and the availability of resources such as medication.5 Furthermore, although there is evidence of an association between chronic medical conditions and heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 as well as predicted worse outcomes for persons with underlying chronic diseases,6,7 studies have reported underutilization of services directed at managing chronic diseases during the pandemic.8

Understanding how the pandemic affects persons living with chronic conditions is critical in mitigating the effect of the pandemic, promoting overall health and preparedness for future pandemics. It is also important to acknowledge that an individual’s health seeking behavior also affects the acceptability and utilization of health services, which invariably affects the success of policies and strategies to curtail the pandemic.9,10 Although several studies have been conducted on how COVID-19 impacted the management of chronic diseases, there is a paucity of information on how the health seeking behaviors of persons living with these conditions contributed to their self-management of their chronic diseases.

Health seeking behaviors are those actions undertaken by individuals who acknowledge that they have a health problem in the bid to find a remedy.11

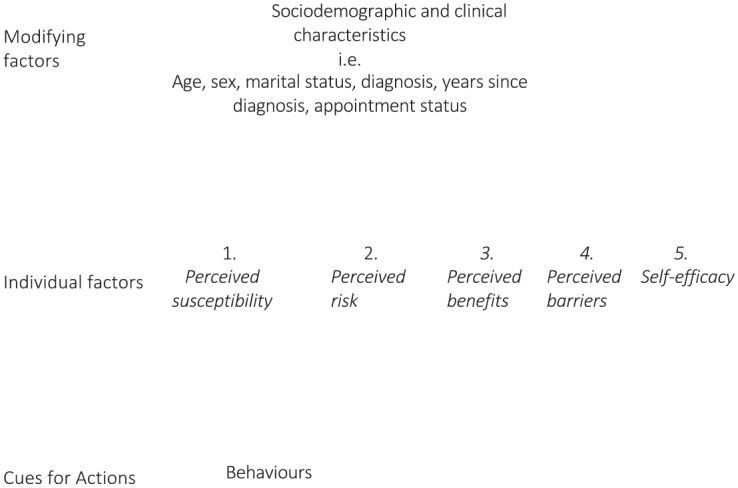

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is a conceptual framework that proposes constructs for the prediction and explanation of health-related behavior changes.12 It is a widely used framework that describes and predicts preventive health behavior.13,14 It places emphasis on intra-personal elements, such as risk-related beliefs that affect people’s health-related decision making.14 Three main constructs of the model; Modifying factors, Individual beliefs, and Actions,15 were explored in the context of how COVID-19 could influence the health seeking behaviors of adults living with chronic conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Constructs of the health believe model.

The modifying factors addresses the demographic and clinical features of the participants that could influence the individuals’ health seeking behaviors. Five sub-concepts were explored under individual beliefs constructs. They include; (a) Perceived susceptibility which explains how the individual/participant evaluates the likelihood of getting sick or experiencing an unintended result. (b) Perceived severity addressed the individual’s evaluation of the seriousness of the sickness, illness or undesirable result and the potential repercussions. (c) Perceived benefits focused on the individual’s evaluation of the advantages of adopting the advised action. (d) Perceived barriers addressed the individual’s appraisal of the factors that deter him or her from adopting the encouraged behavior or activity. (e) Self-efficacy looks at the individual’s confidence in his/her ability to carry out actions required to obtain a desired performance outcome. The final concept in the HBM used in this study is cues for action. This concept is the motivating factor required to start the decision-making process needed to follow a suggested health action. These cues of action are derived from internal signs and symptoms or from external sources such as information derived from reading a newspaper article or advice from people.14,15

This study therefore sought to apply the health belief model (HBM) as a framework to explore the influence of COVID-19 on health seeking behaviors of adults living with chronic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The study utilized an exploratory descriptive design to investigate the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health seeking behaviors of adults living with chronic conditions. Data collection was conducted between February and April 2022. The population was made up of persons diagnosed with either Hypertension or Diabetes Mellitus before the COVID-19 pandemic and who had routine check-up schedules at the Cape Coast Metropolitan Hospital in the Central Region of Ghana. The study was delimited to Hypertension or Diabetes Mellitus because they are a leading cause of non-communicable disease-related admission and mortality in Ghana.16,17

Sampling Strategies

To recruit participants, nurses-in-charge of the hypertension and diabetic out-patient clinics were approached to discuss the purpose of the study. With their help, 2 lists covering patients who honored and those who missed appointments during of the pandemic were generated by reviewing the patients’ clinic records. Patients who were 18 years or older at the time of the data collection and had at least 1 year history of diagnoses with hypertension or diabetes prior to the pandemic were purposively recruited into the study. In total, 22 participants were approached, although none of them declined participation, 2 persons could not be reached on the telephone numbers they provided on the day scheduled for the interviews. Twenty participants were therefore enrolled and interviewed. At enrollment, all participants provided their socio-demographic characteristics and clinical history.

Data Collection

Face-to-face interviews using a semi-structured guide were conducted in English and Fante (a local Ghanaian language predominantly spoken in the region). The interview guide was based on the constructs of the health believe model. Three members of the researcher team conducted independent interviewers. This ensured investigator triangulation.18 The interviews were conducted at a convenient time and place and COVID-19 protocols such as social distancing and wearing of nose mask were maintained during the interaction. Four pilot interviews were conducted initially and used to improve the interview guide but were not included in the final analysis. Following this, interviews were conducted and audio-recorded. Each interview lasted between 35 and 45 min. Data saturation was achieved by the 18th interview but an additional 2 persons were interviewed to confirm saturation.

Data Processing and Analytical Approach

All audio recordings were transferred from the recorder and saved on a password protected computer. The interviews were then transcribed verbatim and back translation was done for the interviews conducted in Fante to ensure the essence of the participants’ experiences were not lost during translation. The data were analyzed using the thematic analytical approach proposed by Braun and Clarke.19

Both inductive and deductive analysis were conducted to unearth the health seeking decisions, and practices of the participants during the pandemic. Both manual and computer-assisted analysis using NVivo 10 software were conducted. To begin with, the researchers familiarized themselves with the data and in the process identified recurring ideas, experiences and phenomena that were assigned labels or codes. The constructs of the Health Belief Model (HBM) were then applied as a reference framework to deductively analyze the qualitative findings. The 3 concepts of the health belief model; modifying factors, individual beliefs and actions, guided the analysis and presentation of findings. Each concept also had sub-concepts/categories under which the findings are presented.

Results

The findings are presented in line with the 3 main concepts in the health belief model.

Concept 1: Modifying characteristics

The participants demographic (age, sex, and marital status) and clinical (years since diagnosis and co-morbidity or otherwise) characteristics reflect the concept of the modifying factors in the health belief model.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Of the 20 participants who were recruited for the study, majority of the participants were females (n = 11/20), 50 years or older (12/20), while half of the participants were married (10/10). Most of the participants were diagnosed with Hypertension (14/20) and the longest years since diagnosis was 20 years. A slight majority (11/20) reportedly missed clinic appointments scheduled for the management of their existing chronic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. The participants had an aggregated 187 years’ experience of managing chronic diseases. The participants sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| Participant ID | Age | Sex | Marital status | Diagnosis | Years since diagnosis | Appointment status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 86 | M | Widow | Co-morbidity | 16 | Missed |

| P2 | 66 | M | Married | Co-morbidity | 8 | Up to date |

| P3 | 60 | M | Married | Hypertension | 7 | Up to date |

| P4 | 41 | F | Divorced | Hypertension | 14 | Missed |

| P5 | 80 | F | Widow | Hypertension | 19 | Up to date |

| P6 | 48 | F | Married | Hypertension | 6 | Missed |

| P7 | 40 | F | Married | Hypertension | 2 | Missed |

| P8 | 80 | F | Widow | Co-morbidity | 15 | Up to date |

| P9 | 40 | F | Single | Hypertension/HIV | 2 | Missed |

| P10 | 58 | F | Divorced | Hypertension | 20 | Up to date |

| P11 | 40 | F | Married | Diabetes | 2 | Up to date |

| P12 | 40 | M | Married | Hypertension | 2 | Up to date |

| P13 | 69 | M | Married | Hypertension | 3 | Up to date |

| P14 | 79 | F | Married | Hypertension | 10 | Missed |

| P15 | 63 | M | Widower | Hypertension | 6 | Missed |

| P16 | 86 | M | Widower | Hypertension | 16 | Missed |

| P17 | 66 | M | Married | Co-morbidity | 9 | Missed |

| RB | 29 | F | Single | Diabetes | 9 | Missed |

| P19 | 41 | F | Separated | Hypertension | 14 | Up to date |

| P20 | 70 | M | Married | Hypertension | 7 | Missed |

Concept 2: Individual factors

Perceived susceptibility

All the participants except 3 were aware of their susceptibility to COVID-19 because of their existing chronic diseases.

If you are hypertensive or diabetic, it’s so easy for you to get the COVID. (P8, Female, co-morbid & up-to date)

Although, they perceive they had a higher susceptibility to contracting the virus compared to others without any chronic disease, none of them knew the factors underscoring this fact or bothered to know why. One participant said:

Please I can’t tell since I am not a doctor. (P1, Male, co-morbid & missed appointments)

Sometimes when you get there [consulting room], there are so many people waiting after you that you don’t have the time to even ask such questions. (P20, Male, Hypertensive & missed appointments)

Perceived severity

All the participants suggested that contracting COVID-19 could exacerbate the chronic disease which could also lead to other complications.

I think that COVID is a terrible disease, if you don’t manage it well, it can worsen your hypertension and cause you to have a stroke. (P9, Female, Hypertensive/HIV& missed appointments)

I had COVID-19 and it affected my kidneys. They said I had kidney injuries and my liver got swollen. So, I was admitted for about three months before I got well. It’s all because I had that chronic disease. Otherwise, those who don’t have [a chronic disease], some people don’t even notice they have gotten it [corona virus]. (P10, Female, Hypertensive & up-to date)

Although, most of the participants knew that the cost of treatment of COVID-19 was borne by the government, the impact of contracting the condition on the family and close associates were also found in the narratives.

As I sit here, I have five of my grandchildren living with me, so if I contract this disease [COVID-19], who will take care of them. I am told that the ambulance will come and take me away. . . who will take care of them. (P5, Female, Hypertensive & up-to date)

From the narratives, all the participants believed that contracting COVID-19 while managing a chronic disease could result in a more severe disease episode and death, compared to others who did not have any chronic disease.

I heard that if you have hypertension and diabetes and you get COVID, you have a high probability of dying than if you don’t. . . I mean like 90 percent chance of dying. It is serious ooh. . . (P17, Male, co-morbid & missed appointments)

For one participant, his perception of the severity of the condition was informed by witnessing a family member who had a chronic disease dying shortly after contracting COVID-19.

I think it all lasted like three days from the time when the ambulance came to pick her [sister-in-law] and the time when my wife told me she had died. . . I believe it could have been as a result of her diabetes because I heard that other younger people in the community who also got it, are well and back home. (P16, Male, Hypertensive & missed appointment)

Perceived benefits

For all the participants, reducing their risk of contracting virus as well as controlling the chronic diseases they were living with was reportedly the most important benefit of adopting positive health behavior during the pandemic. Many of the participants suggested that contracting COVID-19 will possibly result in death and therefore felt that proactively managing their health was an important benefit to living a healthy life.

With all that is going on with my health now, I know that contracting COVID-19 will push me into my grave and I am not ready for that. That is why I do all that I am told to do, like stay at home. (P9, Female, Hypertension/HIV & missed appointment)

The perception that they could not be a conduit for the transmission of the virus to other family members and close associates was also identified in the narratives.

If I don’t get it [corona virus], my children will also not get it from me. My neighbours will not get it from me. So, that is also a benefit of not getting COVID. (P11, Female, Diabetes & up-to date)

A participant alluded to the fact that COVID-19 related death robbed the individual and family from perpetuating family traditions and therefore intimated that as a benefit of seeking and practicing a healthy behavior during the pandemic.

They say that all die be die, but this one [death associated with [COVID-19] is very painful. You will not even have family members to bury you or properly mourn you. . . Having lived all these years, I deserve a proper burial. (P1, Male, co-morbid & missed appointments)

Perceived barriers

The participants identified several barriers that they believed made it harder to access the care and information necessary to manage their chronic diseases and prevent COVID-19. Lack of access to health professionals during the peak of the pandemic was mainly identified as the main barrier. For many of them, the fear of contracting the virus while accessing their regular chronic disease clinic was the main explanation for the missed clinic appointments.

I stopped going to the hospital for almost a year because I didn’t want to catch the virus [corona] there. Hence, I couldn’t get my drugs. . . then I developed the stroke and had to be brought here anyway. (P20, Male, Hypertension & missed appointment)

I didn’t go for my appointment because, I heard on the news that, we were only to go to the hospital when you were very ill. But I was alright, so I decided to stay home and manage myself. (P1, Male, co-morbid & missed appointment)

A few of the participants, intimated that following the precautions for prevention of COVID-19 came with additional financial burden. This they narrated made them inconsistent in its use and therefore cause fear of contracting the virus an issue of concern during the peak of the pandemic.

They said we should wear mask and use hand sanitiser. But at the peak of the pandemic, the prices were so high that, I sometimes had to choose when to use them and when not to depending on when the people gathered were many or not. So, I was worried most of the time that I could have contracted the virus and that was not good for my BP [blood pressure]. The prices made it impossible to use them [mask and hand sanitiser] as was required. (P7, Female, Hypertension & missed appointment)

Others also intimated the loss of revenue as a barrier to ensuring that the adopted healthy behaviors that could avert contracting the corona virus and also maintain their health.

During that time everybody was home. People were not buying my foodstuffs because some had lost their jobs or source of revenue. So how were we supposed to buy the gloves and sanitiser? (P19, Female, Hypertension & up-to date)

Self-efficacy

For several of them, the actions required to ensure their chronic diseases are effectively managed did not demand additional efforts from what they were previously doing. Thus, they were confident that they had the capacity to do same.

For the past 20 years since I was told that I have hypertension, I have been managing it without developing any complications. So, I believe that all I had to do was to continue taking my drugs and resting when I am tired. That has not changed. . . (P10, Female, Hypertension & up-to date)

For others also, although they initially had to refrain from accessing the health care facilities in fear of contracting COVID-19, the ability to manage their chronic diseases was still available to them as they had access to community chemical shops and pharmacies where they could procure the needed treatment over the counter.

I was sure that as for the drugs I could get them because, the chemical shops were opened and I also knew the drugs and dosages that I was on. So, I was not worried about controlling my BP and the sugar. (P17, Male, co-morbid & missed appointment)

Other participants also alluded to the fact that most of the precautionary measures required to ensure they were protected against contracting the virus only required effort, which they believed they effectively applied.

As for me I accepted to stay at home as my children suggested; no church, no funerals, no meetings of any sort. I think that, staying at home saved me a lot of money and also ensured that I was not in contact with people who had corona [COVID-19]. I only talked to my grandchildren on the phone. (P5, Female, Hypertension & up-to date)

The main thing the nurses said would ensure I don’t get COVID was frequently washing my hands. As for that one, I was already doing it, so I only had to increase the frequency. (P2, Male, co-morbid & up-to date)

For others also, their living conditions and socioeconomic status made it difficult to fully adopt the precautionary measures, thus impacting their capacity to effectively ensure that they prevented COVID-19.

If you leave in a family housei like me, you can’t think about social distancing. My grandchildren always brought their friends from other houses to watch TV in my room. How could I stop them? Schools had closed and they needed something to do or else mine [grandchildren] will go out. So, I didn’t have control over that. Although, I initially decided to give them a face mask when they came to my room, I could not sustain it because of the cost. (P14, Female, Hypertension & missed appointment)

Concept 3: Actions

Cues for action

Knowledge of their susceptibility that served as a cue to action was informed by reports gathered from the media and their interactions with health professionals. Most of the participants were concerned about the mortality rate associated with the disease announced on the radio.

I heard the staff of Ghana Health Service interviewed TV and radio saying that those who have pre-existing conditions such as hypertension and diabetes [mellitus] are more likely to get the COVID-19 and die. (P6, Female, Hypertension & missed appointment)

For most of the participants, this knowledge of their heightened susceptibility because of the chronic diseases they were managing incited fear and anxiety, that became a catalyst for adhering to precautionary measures.

Because the nurses at the clinic [hypertensive] told me to be careful so that I don’t get the virus. So, initially, I was so afraid of getting the infection that I decided not to go out of my house. (P18, Female, Diabetes & missed appointment)

For one of the participants, witnessing the illness, diagnosis, quarantine and subsequent death of a family member was the cue for action.

She also had hypertension like me, but she was younger. I don’t know what happened but I heard she was still selling her wares from home, so she didn’t bother to practice social distancing. I heard she started coughing, and then went to the hospital. According to my wife, she was kept there [admitted] when she was diagnosed with the illness [COVID-19]. They [health staff] didn’t allow us to see her because she was very sick. I think that the hypertension actually made her feel the pain of the disease and died after a short while. They didn’t even allow us [family] to bury her. . . So, as for me I am very careful. (P16, Male, Hypertensive & missed appointment)

For another participant who was a health professional, her experiences working in the hospital confirmed the messages she had learnt from her colleagues and superiors that having a chronic disease increased your risk and the severity of the condition.

Working in the hospital gave me an experience that many people do not have. Some of my colleagues contracted the virus and were quarantined but none of them died. But our records showed that several people died and they mostly had other existing chronic disease. So, this made me take extra precautions to ensure that I didn’t contract COVID because I have hypertension. (P11, Female, Diabetes & up-to date)

Yet another participant’s personal experiences of contracting COVID also served as a cue for adhering to the precautions to prevent reinfection.

I was a victim, I had COVID-19. . . (P10, Female, Hypertension & up-to date)

Behaviors

Most of the participants adopted protective behaviors to ensure that they did not contract the virus. A number of the participants reported avoiding crowded areas and ensuring physical distancing.

The main thing for me was not going into crowded places. So, I even stopped going to the hospital because I felt that that was the place where the people carrying the virus will go. (P15, Male, Hypertensive & missed appointment)

Self-medication was also identified as a strategy adopted by some participants.

I heard that Zinc [tablets] and Vitamin C was very good in fighting the virus so I bought some and took it myself. . . No, it was not prescribed by the doctor. (P17, Male, co-morbid & missed appointment)

Although, adopting this precaution included not honoring review appointments at the clinic, all the participants intimated adhering to their medication by accessing them over-the-counter.

Last year [2021] when COVID was all over the place, I used my old prescription to get drugs at the chemical shop just behind my house. So, as for the drugs to manage my hypertension, I never missed even a day. (P15, Male, Hypertensive & missed appointment)

For others also, they followed the COVID-19 precautions to ensure that they did not contract the virus.

I always washed my hands regularly and used my sanitiser and face mask even though it was difficult to breath at first. But I had to do it to prevent the disease. (P13, Male, Hypertensive & up-to date)

Another behavior reported by many of the participants was dietary modifications. Although, several participants had already modified their diet before the pandemic as part of management of their chronic diseases, the advent of COVID-19 resulted in further modifications.

I increased the use of local spices such as ginger and cloves in my meals as I heard they improve your health and prevent all kinds of diseases. (P6, Female, hypertensive & missed appointment)

I drank a lot of the Sobolo.ii I was told it would boost our health [immunity] and prevented diseases. (P4, Female, Hypertensive & missed appointment)

Others also adopted traditional approaches to disease prevention such as the drinking of herbal preparations and steam inhalations as a remedy for preventing COVID-19 and managing their chronic conditions.

I also drink “dudoiii.” It is very good. They [children] add the roots of several plants and boil. Then allow it to cool. Then I drink it in portions until it finishes. Then we boil another batch. It is a trusted ancient medicine that can kill all the bacteria and viruses that cause diseases. (P16, Male, Hypertensive & missed appointment)

I do steam inhalation. . . I boil the leaves of neem tree and add Robbiv and then do a steam inhalation while sitting under a pile of cloths. It makes me sweat profusely and clears my nose. I am sure that because they say the COVID lives in your chest, it will not survive. (P2, Male, co-morbid & up-to date)

Narrations of faith-based interventions were also gleaned from the participants. For several of them, although, they could not fellowship with other believers during the peak of the pandemic when the country instituted lock down and ban on gathering, prayer was important in preventing the infection. Faith in a God who was able to protect them resonated in several of the participants narrations.

Our faith was that when we pray, we won’t get the disease. (P5, Female, Hypertension & up-to date)

Discussion

The current study applied the concepts of the health belief model to qualitatively explore the health seeking behaviors of adults living with chronic diseases during the pandemic. In this study, in relation to the concept of Modifying factors, participants demographic characteristics such as age, sex and marital status, and clinical characteristics including, years since diagnosis and co-morbidity or otherwise and appointment status were explored. These characteristics gave insight into the context of the participants’ and the health seeking behaviors they adopted during the pandemic. However, because the study was qualitative in nature, inferences were not made based on these modifying characteristics.

Following the exploration of the concept of Individual beliefs, the study findings revealed that participants were aware of their susceptibility to COVID-19 and the possibility of a more severe illness episode as a result of their existing chronic diseases. Similarly, in Ethiopia, 79.2% of study participants knew about the susceptibility and increase risk for severe episodes of COVID-19 of people living with chronic diseases.20 This increase awareness is an important precursor for the adoption of positive health seeking behavior that promote health and prevention of diseases like COVID-19.21 In spite of the high level of awareness, most participants in this study were unaware of the factors underlying this fact. The participants deferred that knowledge to experts. Similar to findings in a Sri Lankan study which found an association between perceived benefits and health seeking behaviors in the general population,22 this study found that maintenance of health and the avoidance of contracting COVID-19 were the main benefits informing the health seeking behavior identified in this study. Also, preventing contracting the condition to protect family members were also an important benefit for adhering to the COVID-protocols and the management of their existing chronic diseases. Similar findings are reported in rural Central Appalachia where the main benefits were associated with concerns about family and community.23

Furthermore, participants in this study exhibited self-efficacy. This corroborates other quantitative studies22,24,25 that established significant relationship between self-efficacy and COVID-19 preventive behavior. This self-efficacy stemmed from confidence built on past experiences of managing their chronic diseases. This finding corroborates a review that reported that as people gain confidence in managing their chronic diseases, there is less reliance on the health system.26

On the concept of Action, the abundance of information in the media on the increased susceptibility and the severity of COVID-19 if they contracted the virus was primarily the cue to action. In this relatively new pandemic, participants relied also on information gathered through the increased media reportage. Studies have identified the increasing reliance on the media for health related information27,28 among people with chronic diseases. Its noteworthy that, although information abounded during the peak of the pandemic, myths and the lack of information targeted at different groups of persons having varied health needs resulted in uninformed decision making such as miss appointments at the chronic disease clinic resulting with one client suffering a stroke in this study. This phenomenon corroborates findings recorded among HIV patients.29 If not checked, efforts made at achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) target 3.4 that seeks to promote life and health for persons living with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) through prevention and treatment30,31 will be eroded.

Study findings also unearthed behavior modification strategies by incorporating folk knowledge as well as information gleaned from the society and media into self-management. These included the use of dietary modifications and traditional home remedies such as steam inhalation to prevent COVID-19 and invariably maintain their health. Similar findings were reported by other studies in Italy,32 United States33 and Ghana.34 Although, no study has reported dietary modification and supplementation,35 or established the effectiveness of steam inhalation36 could prevent COVID-19, Hibino and Hayashida intimated that in the wake of vaccine hesitancy, effective non-pharmaceutical interventions, healthy lifestyles and improved dietary patterns could improve the health of individuals and reduce the risk for COVID-19.37 Several other studies emphasized the relevance of micronutrients such as zinc and Vitamins in the optimization of immune system and regulating immune response.38 These dietary modifications could also improve the management of the existing chronic diseases.

Limitations and Strengths

Because gatekeepers were involved in generating the list of eligible participants, the possibility of selection bias cannot be excluded as clients are long-term attendants of the clinic who were well-known to the health professionals. To address this, the researchers had the sole responsibility of contacting the eligible participants. Also, we cannot rule out the possibility of social desirability as participants shared their health seeking behaviors. To minimize this, recruitment was conducted among both those who were up-to date and those who had missed appointment.

The study’s strength lies in its application of a theory to analyze the health seeking behaviors of the participants. This study therefore contributes to evidence creation and knowledge base of the influence of COVID-19 on health seeking behavior among persons living with chronic diseases.

Conclusion

The health belief model was a useful framework in exploring the health seeking behavior of adults living with chronic conditions during the COVID-19 in this study setting. These findings have important implication for the management of chronic conditions during pandemic and thus are critical for preparedness toward future pandemics. Several cues were present that impacted the participants behaviors directed at maintaining health with regards to the management of chronic disease and preventing the contracting of COVID-19. Modification to diet and lifestyle, and adoption of COVID-19 related precautions enhance the health of the participants.

Recommendations for Policy and Practice

To avert missed visits and its implications for national and global health targets, it is recommended that policies or guidelines are enacted to ensure continuous service delivery to chronic disease management during pandemics and similar situations in the future.

There is the need for health professionals to intensify education on the factors contributing to the perceived susceptibility of person’s living with chronic diseases to contracting COVID-19 and during future pandemics. This could contribute to positive health seeking behaviors and an improved quality of life even during pandemics.

Recommendations for Future Research

Further research on the effectiveness of those non-pharmacologic interventions utilized by chronic disease patients in this study to prevent and manage COVID-19 is recommended.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend many appreciations to all the patients who participated in the study as well as the Staff and Management of the Cape Coast Metropolitan Hospital for granting the needed support to conduct the study.

A communal home which houses members of the extended family.

Juice made from the extracts from hibiscus flower and laced with local spices such as ginger, negro pepper, cloves to taste which are believed to have a lot of medicinal purposes.

Mixture of roots, herbs and spices used by the Akans to treat minor ailments and to prevent diseases.

Balm made with Eucalyptus and menthol used to relieve nasal congestion and pain.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: SAA, DOY, DTD, ESB, and AAOF designed the research. SAA, DFA, and NKY collected the data, analyzed and drafted the manuscript. SAA, DOY, DTD, ESB, and AAOF reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the University of Cape Coast, Directorate of Research, Innovation and Consultancy’s Sixth Research Support Grant.

Ethical Approval: Approval for the study was granted by the University of Cape Coast Institutional Review Board (UCCIRB/EXT/2022/02). Ethical principles proposed by Helsinki Declaration of Scientific Research for the conduct of research were also adhered to (20). Pseudonyms were chosen by the participants to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. Participants gave both written and oral informed consents for participation and publication of the findings.

ORCID iD: Susanna Aba Abraham  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3100-770X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3100-770X

References

- 1. WHO. Global Health Estimates 2019: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2019. WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. Key facts. Noncommunicable diseases. Published 2021. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

- 3. Yawson AE, Abuosi AA, Badasu DM, Atobra D, Adzei FA, Anarfi JK. Non-communicable diseases among children in Ghana: health and social concerns of parent/caregivers. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16(2):378-388. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i2.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470-1477. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chudasama YV, Gillies CL, Zaccardi F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: A global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res. 2020;14(5):965-967. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laires PA, Dias S, Gama A, et al. The association between chronic disease and serious COVID-19 outcomes and its influence on Risk Perception: Survey Study and database analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(1):e22794. doi: 10.2196/22794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murray C. The Lancet: Latest global disease estimates reveal perfect storm of rising chronic diseases and public health failures fuelling COVID-19 pandemic. IHME. Published 2020. Accessed October 7, 2021. http://www.healthdata.org/news-release/lancet-latest-global-disease-estimates-reveal-perfect-storm-rising-chronic-diseases-and [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shimels T. The trend of Health Service utilization and challenges faced during the COVID-19 pandemic at primary units in Addis Ababa: A Mixed-methods study. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2021;8:1-8. doi: 10.1177/23333928211031119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaikh BT, Hatcher J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. J Public Health. 2005;27(1):49-54. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Westgard CM, Rogers A, Bello G, Rivadeneyra N. Health service utilization, perspectives, and health-seeking behavior for maternal and child health services in the Amazon of Peru, a mixed-methods study. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1056-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Q, Feng S, Wong IOL, Ip DKM, Cowling BJ, Lau EHY. A population-based study on healthcare-seeking behaviour of persons with symptoms of respiratory and gastrointestinal-related infections in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duarsa ABS, Mardiah A, Hanafi F, Karmila D, Anulus A. Health belief model concept on the prevention of coronavirus disease-19 using path analysis in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Int J One Health. 2021;7(1):31-36. doi: 10.14202/IJOH.2021.31-36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herrmann A, Hall A, Proietto A. Using the health belief model to explore why women decide for or against the removal of their ovaries to reduce their risk of developing cancer. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Green E, Murphy E, Gryboski K. The Health Belief Model. Wiley Encycl Health Illness Behav Soc. 2014;2:766-769. doi: 10.1002/9781118410868.WBEHIBS410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bosu WK, Bosu DK. Prevalence, aAwareness and cControl of hHypertension in Ghana: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sarfo-Kantanka O, Sarfo FS, Oparebea Ansah E, Eghan B, Ayisi-Boateng NK, Acheamfour-Akowuah E. Secular trends in admissions and mortality rates from diabetes mellitus in the central belt of Ghana: a 31-year review. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. UNAIDS. An Introduction to Triangulation. UNAIDS; 2010. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/10_4-Intro-to-triangulation-MEF.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Melesie Taye G, Bose L, Beressa TB, et al. COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and prevention practices among people with hypertension and diabetes mellitus attending public health facilities in Ambo, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:4203-4214. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S283999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tian M, Chen Y, Zhao R, et al. Chronic disease knowledge and its determinants among chronically ill adults in rural areas of Shanxi Province in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:948. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mahindarathne PP. Assessing COVID-19 preventive behaviours using the health belief model: A Sri Lankan study. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2021;16(6):914-919. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2021.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adeniran E, Ahuja M, Awasthi M, et al. Factors associated with adherence to evidence-based recommendations for covid-19 prevention among people with cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2021;143(Suppl 1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shahnazi H, Ahmadi-Livani M, Pahlavanzadeh B, Rajabi A, Hamrah MS, Charkazi A. Assessing preventive health behaviors from COVID-19: a cross sectional study with health belief model in Golestan Province, northern of Iran. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00776-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deshpande S, Basil MD, Basil DZ. Factors influencing healthy eating habits among college students: an application of the health belief model. Health Mark Q. 2009;26(2): 145-164. doi: 10.1080/07359680802619834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allegrante JP, Wells MT, Peterson JC. Interventions to support behavioral self-management of chronic diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:127-146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hopkinson NS. Social media as a source of information for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis. 2014;11(2):59-60. doi: 10.1177/1479972314528959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abraham SA, Agyemang SO, Ampofo EA, Agyare E, Adjei-Druye A, Obiri-Yeboah D. Living with hepatitis B virus infection; media messaging matters. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32(7):591-599. doi: 10.1177/0956462420965837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abraham SAA, Doe PF, Osei Berchie G, Agyare E, Ayisi Addo S, Obiri-Yeboah D. Explorative–descriptive study on the effects of COVID-19 on access to antiretroviral therapy services: the case of a teaching hospital in Ghana. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e056386. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Singh Thakur J, Nangia R, Singh S. Progress and challenges in achieving noncommunicable diseases targets for the sustainable development goals. FASEB BioAdvances. 2021;3(8): 563-568. doi: 10.1096/fba.2020-00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bennett JE, Kontis V, Mathers CD, et al. NCD Countdown 2030: pathways to achieving Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2020;396(10255):918-934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31761-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Maria M, Ferro F, Vellone E, Ausili D, Luciani M, Matarese M. Self-care of patients with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(5):1431-1447. doi: 10.1111/jan.15115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Finlay JM, Kler JS, O’Shea BQ, Eastman MR, Vinson YR, Kobayashi LC. Coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study of older adults across the United States. Front Public Health. 2021;9:1-12. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.643807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saah FI, Amu H, Seidu AA, Bain LE. Health knowledge and care seeking behaviour in resource-limited settings amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study in Ghana. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0250940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coelho-Ravagnani CDF, Corgosinho F, Sanches F, Prado CM, Laviano A, Mota JF. Dietary recommendations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Kompass Nutr Diet. 2021;1(1):3-7. doi: 10.1159/000513449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chowdhury MNR, Alif YA, Alam S, et al. Theoretical effectiveness of steam inhalation against SARS-CoV-2 infection: updates on clinical trials, mechanism of actions, and traditional approaches. Heliyon. 2022;8(1):e08816. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hibino S, Hayashida K. Modifiable host factors for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19: diet and lifestyle/diet and lifestyle factors in the prevention of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2022;14:9. doi: 10.3390/nu14091876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Faria Coelho-Ravagnani C, Campos Corgosinho F, Ziegler Sanches F, Marques Maia Prado C, Laviano A, Mota J. Dietary recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutr Rev. 2021;79(4):382-393. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]