Abstract

Transcriptome evaluation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the lungs of laboratory animals during long-term treatment has been limited by extremely low abundance of bacterial mRNA relative to eukaryotic RNA. Here we report a targeted amplification RNA sequencing method called SEARCH-TB. After confirming that SEARCH-TB recapitulates conventional RNA-seq in vitro, we applied SEARCH-TB to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected BALB/c mice treated for up to 28 days with the global standard isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol regimen. We compared results in mice with 8-day exposure to the same regimen in vitro. After treatment of mice for 28 days, SEARCH-TB suggested broad suppression of genes associated with bacterial growth, transcription, translation, synthesis of rRNA proteins and immunogenic secretory peptides. Adaptation of drug-stressed Mycobacterium tuberculosis appeared to include a metabolic transition from ATP-maximizing respiration towards lower-efficiency pathways, modification and recycling of cell wall components, large-scale regulatory reprogramming, and reconfiguration of efflux pumps expression. Despite markedly different expression at pre-treatment baseline, murine and in vitro samples had broadly similar transcriptional change during treatment. The differences observed likely indicate the importance of immunity and pharmacokinetics in the mouse. By elucidating the long-term effect of tuberculosis treatment on bacterial cellular processes in vivo, SEARCH-TB represents a highly granular pharmacodynamic monitoring tool with potential to enhance evaluation of new regimens and thereby accelerate progress towards a new generation of more effective tuberculosis treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ongoing public health crisis, killing approximately 1.2 million people each year.1 A key challenge for global TB control is the length of treatment required to cure TB, 4–6 months for infection with drug-sensitive genotypes. The need for prolonged treatment is thought to be due to a transition of the M. tuberculosis (Mtb) population to harder-to-kill phenotypes as therapy progresses.2 At the start of treatment, the Mtb population is highly susceptible to killing. When mice or humans initiate the global standard isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol (HRZE) regimen, ~99% of the culturable bacterial population is eliminated during the initial days to weeks of the bactericidal phase. Thereafter, the rate of killing slows considerably3–7 as drug-tolerant phenotypes come to dominate the residual Mtb population. Drug-tolerant phenotypes have been defined as Mtb with decreased susceptibility to killing despite an absence of drug resistance conferring mutations.2,8

Eliminating drug-tolerant Mtb phenotypes is considered crucial to shortening the duration of TB treatment.2 The central focus of contemporary drug discovery and regimen development is drug-tolerant Mtb phenotypes that cause relapse and dictate the need for prolonged treatment.2,9–11 Unfortunately, the physiologic state of the Mtb subpopulation that withstands drug treatment in vivo remains obscure, limiting our ability to rationally design regimens that target specific cellular processes.

Transcriptional profiling has been used extensively as a readout of how drugs affect bacterial cellular processes in vitro.12–18 By contrast, we are not aware of previous genome-wide transcriptional profiling of Mtb during prolonged treatment of laboratory animals. In vivo analyses are important because the pathogen adapts its cellular processes to the physicochemical conditions and immune responses it encounters in the host, resulting in a phenotype and transcriptome distinct from that measured in vitro.19–27 Since phenotypic characteristics of the Mtb population strongly influence drug sensitivity,28 understanding the effect of drugs on the bacterial populations that cause disease in vivo would enable us to better “know the enemy,” thereby informing drug and regimen development.

The central impediment to transcriptional profiling in vivo is that Mtb mRNA is generally present at extremely low abundance relative to host RNA even in a treatment-naïve animal. When the pathogen burden decreases due to treatment, quantification of Mtb mRNA becomes progressively more difficult. To elucidate Mtb signal from the overwhelming eukaryotic background, diverse methods have been used to first enrich and then quantify Mtb mRNA (Fig. 1). Enrichment methods have included various combinations of differential cell lysis to separate Mtb and eukaryotic material during sample preparation, reverse transcription with pathogen-specific primers, depletion of host and/or bacterial rRNA, various hybridization capture methods, and selective PCR amplification of target Mtb transcripts. Enrichment is followed by quantification via microarray,19,20,27,29 multiplex PCR,7,21,25,30–33 or RNA-seq.22,26,34–37 Unfortunately, even the most sophisticated and contemporary platforms have limited sensitivity that has precluded transcriptional evaluation of the effect of long-term treatment with potent TB regimens. In this work, we demonstrate SEquening after Amplicon enRiCHment for TB (SEARCH-TB), a targeted, highly sensitive, pathogen-specific sequencing method for enriching and quantifying the Mtb transcriptome in tissues of infected animals. Using a novel combination of enrichment (differential cell lysis during sample preparation + targeted amplification) and quantification (RNA-seq), SEARCH-TB achieves sensitivity that will enable routine use of transcriptional profiling for drug evaluation in animal models, expanding understanding of drug effect and accelerating new regimen development.

Fig. 1. Visual summary of methods previously used to quantify the Mtb transcriptome in vivo.

Each horizontal arrow represents a distinct combination of enrichment and quantification. Varying enrichment methods are represented via the symbols shown in the key. SEARCH-TB is a unique combination of enrichment (eukaryotic cell lysis + targeted amplification) followed by quantification via RNA-seq that has enabled transcriptome evaluation in mice treated for weeks with a potent combination regimen. Image created with Biorender.com.

Here, we used SEARCH-TB to evaluate gene expression of the Mtb population that persists in the lungs of BALB/c mice treated with HRZE for up to four weeks. We further used SEARCH-TB to compare the effect of HRZE in vivo and in vitro. SEARCH-TB has the potential to serve as a highly granular readout of drug effect by providing a molecular readout of cellular adaptations of in vivo drug-tolerant Mtb.

METHODS

Design of the SEARCH-TB assay

The SEARCH-TB assay uses an AmpliSeq for Illumina custom pool designed to amplify coding sequence (CDS) of Mtb complex (MTBC) organisms. To assure amplification across diverse lineages, the design used eight MTBC reference genomes (Table S1). Annotations were prepared for Mtb H37Rv (NC_000962) and Mtb Erdman (AP012340.1) as described in the Supplemental Information. To avoid off-target amplification (i.e., of non-MTBC organisms), primers were cross-referenced during design with 12 “exclusion” genomes that included phylogenetically diverse bacteria as well as human and mouse (Table S2).

Evaluation of amplification bias

We tested for amplification bias (i.e., differences in amplification efficiency between primer pairs targeting different Mtb sequences) using replicate human lung RNA samples spiked with Mtb genomic DNA (gDNA) (Supplemental Information). Since all targeted sequences are present as single copies in gDNA, an entirely unbiased assay would hypothetically result in the same copy number for all targets, indicating that all primer pairs amplified with identical efficiency. We defined amplification bias as deviation from this ideal by comparing the observed expression for a gene to the expected expression assuming no amplification bias (Supplemental Information).

Evaluation of repeatability of amplification

To evaluate repeatability, we spiked 1pg Mtb RNA into 1ng human lung RNA (Supplemental Information). We compared counts per million (CPM) values for each gene between technical replicates. We also evaluated repeatability over time by prepping and sequencing 19 of the in vitro and murine samples described below two times with up to a 4-month intervening interval. We quantified batch effect by calculating the difference in expression (normalized with DESeq2’s variance stabilizing transformation38) of each gene between replicate pairs, then averaging across replicates. We compared the magnitude of the batch effect with the observed treatment effect.

Concordance of SEARCH-TB with conventional RNA-seq

We evaluated whether SEARCH-TB identified the same transcriptional changes as a conventional RNA-seq method without Mtb targeted amplification (Illumina TrueSeq) after 24-hour in vitro isoniazid (INH) exposure (Supplemental Information). We first evaluated RNA from control (N=4) and INH-treated samples (N=4) via conventional RNA-seq to serve as a reference standard. We then spiked the same RNA from control and INH-treated Mtb into human lung RNA at a ratio of 1:1,000 and sequenced via SEARCH-TB. After calculating differential expression between control and INH-treated samples separately for conventional RNA-seq and SEARCH-TB using edgeR,39 we compared the significant genes and fold-changes identified by the two platforms.

In vitro experiments

Mtb strains H37Rv and Erdman were cultured in vitro using Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.085 g/l NaCl, 0.2% glucose, 0.2% glycerol, 0.5% BSA, and 0.05% Tween-80. All culturing was performed at 36.5°C and 5.0% CO2. Single use frozen Mtb aliquots were revived in 7H9 and grown to mid-log phase then cultures were diluted to OD600=0.05, dispensed in 5.0 ml aliquots into sterile glass tubes (20 by 125 mm) containing sterile stir bars (12 by 4.5 mm), and outgrown for 18 h under rapid agitation (~200 rpm stirring speed using a rotary magnetic tumble stirrer) prior to the initiation of drug exposure. RNA was collected from Mtb H37Rv exposed to INH or Mtb Erdman exposed to HRZE in vitro (Supplemental Information).

Murine drug experiments

All animal procedures were conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines and approved by the Colorado State University Animal Care and Use Committee as described in the Supplemental Information. Briefly, female BALB/c mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were aerosol infected (Glas-Col) with Mtb Erdman strain resulting in the deposition of 4.55±0.03 (SEM) log10 CFU in lungs one day following aerosol. After 11 days, five mice were euthanized to serve as the pre-treatment control group. Groups of five mice each were treated with HRZE at standard doses five days a week for 14 or 28 days before euthanasia. Lungs were aseptically dissected, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen before processing.

RNA extraction, sequencing, and data preparation

RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing and data preparation are detailed in the Supplemental Information.

Statistical analysis of murine and in vitro experiments

Murine and in vitro sequence data were analyzed together using edgeR39,40 to identify the effect of HRZE treatment in and compare gene expression between murine and in vitro experiments. We fit negative binomial generalized linear models to each gene and included terms for murine and in vitro time points (control, day 14 and day 28 in mice; control, day 4 and day 8 in vitro). Likelihood ratio tests were performed to compare expression between murine time points, between in vitro time points, and between murine and in vitro experiments before and at the end of treatment. Genes with Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value41 less than 0.05 were considered significant. For murine experiments, we used hierarchical clustering to identify groups of genes with similar changes in gene expression over the course of treatment as follows. First, for genes that were differentially expressed between at least two time points, we calculated the expected expression at each time point using the edgeR models. Then, the expected expression values were hierarchically clustered based on Euclidian distance using Ward’s method42 to find clusters of genes with similar patterns of expression over time.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using data for the 500 most variable genes after normalization with DESeq2’s variance stabilizing transformation.38

Using hypergeometric tests in the hypeR R package,43 we performed functional enrichment for each pairwise combination of murine and in vitro time points to evaluate whether differentially expressed genes were overrepresented in gene categories established by Cole44 or curated from the literature (Table S3). Enrichment analysis was run twice for each pairwise combination, first using significantly upregulated genes and then using significantly downregulated genes. Gene categories with <8 genes were excluded. Gene categories with Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-values41 less than 0.05 were considered significant. All analysis used R (v4.1.1).45

Online analysis tool

Differential expression, functional enrichment, and visualizations can be evaluated interactively using an Online Analysis Tool [https://microbialmetrics.org/analysis-tools/] created using the R package Shiny.46

RESULTS

Validation of SEARCH-TB assay

Results of SEARCH-TB design

Primers were designed to amplify 3,733 (92.6%) of 4,031 CDS in the Mtb H37Rv genome. Primers for 95 genes failed to amplify in initial testing and were excluded from analysis. Additionally, we excluded 70 genes that were not present in the Mtb Erdman strain used in murine and in vitro experiments. The final panel analyzed targeted 3,568 Mtb genes (Fig. S2).

Evaluation of amplification bias

Using gDNA (a matrix in which each target sequence should be present in equal abundance), we quantified deviation from the ideal value that would be expected if all primers had identical amplification efficiency (Fig. 2a). Of all primer pairs, 78% were within one log2 fold change of the ideal value.

Fig. 2. Evaluation of SEARCH-TB platform.

a. Distribution of log2 fold differences of normalized gDNA SEARCH-TB expression data relative to the value expected if there were no amplification bias. Zero (dashed vertical line) represents no amplification bias. b. Evaluation of repeatability of SEARCH-TB showing normalized expression data (log counts per million) for two technical replicates in which Mtb RNA was spiked into human lung RNA. c-d. Volcano plot showing log2 fold-changes and −log10 p-values induced by in vitro INH exposure as quantified by RNA-seq (c) and SEARCH-TB (d). Genes significantly down- and upregulated with INH exposure relative to control (adj. p-value< 0.05) are shown in blue and red. e. Comparison of differential expression between INH treated samples and control samples from RNA-seq or SEARCH-TB data. Purple shading indicates genes with concordant fold-change direction and significance between RNA-seq and SEARCH-TB. green shading indicates genes that were significant in RNA-seq or SEARCH-TB results, but not both. Gold shading indicates genes that were significant for both RNA-seq and SEARCH-TB, but in opposite directions. Gray shading indicates genes that were not significantly differentially expressed in either RNA-seq or SEARCH-TB. f. Comparison of INH vs. control fold-changes from RNA-seq data vs. SEARCH-TB data. Purple, green, gold and gray colors have the same meaning as in e.

Repeatability of amplification

SEARCH-TB results were highly repeatable among spike-in technical replicates (Fig. 2b). The batch effect between replicates prepared and sequenced over time was minimal relative to the treatment effect (Fig. S3).

Concordance of SEARCH-TB with conventional RNA-seq

RNA from in vitro exposure showed a similar direction and scale of differential expression when sequenced via SEARCH-TB and conventional RNA-seq (Fig. 2c–d). The gene sets identified as differentially expressed by the two platforms strongly overlapped (Fig. 2e). The fold-changes quantified by the two platforms showed strong agreement (R2=0.82) (Fig. 2f), indicating that while SEARCH-TB is uniquely capable of profiling in drug-treated animals, both platforms provide the same biological information in in vitro RNA.

Transcriptional differences of between Mtb in murine and in vitro controls

In the absence of HRZE, a PCA plot showed the transcriptional profiles of the pre-treatment murine control and the in vitro early log-phase growth control were distinct (Fig. 3a) with 2,444 (68%) differentially expressed genes (Fig. 3b). Compared with the in vitro control, untreated mice appeared to harbor a less active Mtb phenotype with lower expression of genes associated with rRNA protein synthesis (adj-P=1.7×10−18), aerobic metabolism (adj-P=2.1×10−5), fatty acid synthesis (adj-P=0.002) and other growth-associated processes (Online Analysis Tool). Conversely, Mtb in untreated mice had higher expression of processes previously associated with adaptation to the host47, including genes in the DosR regulon that responds to hypoxia, nitric oxide, and carbon monoxide48,49 (adj-P=1.4×10−12), the KstR1 and KstR2 regulons involved in cholesterol catabolism50 (adj-P=7.2×10−5 and 3.9×10−4, respectively), mycobactin genes that respond to iron scarcity51 (adj-P=6.4×10−4) and other processes (Online Analysis Tool). SEARCH-TB recapitulated specific previously described adaptations for persistence in vivo, including higher expression in untreated mice compared to the in vitro control of icl1 (adj-P=3.8×10−13), the first gene of the glyoxylate bypass used during catabolism of fatty acids52, and increased expression of tgs1 (adj-P=8.1×10−35) involved in triacylglycerol synthesis under environmental stress53.

Fig. 3. Overview of transcriptional response to HRZE in mice and in vitro experiments.

a. Principal components plot including all mouse (triangles) and in vitro (squares) samples. Time points are shown by color. b. Volcano plot summarizing the differential expression between Mtb in mice and in vitro prior to treatment. Genes significantly down- (blue) or upregulated (red) in mice relative to in vitro (adj-P-value< 0.05) are shown. c. Mtb CFU and RS ratio values for control mouse samples and 14- or 28- days after HRZE treatment initiation. d-e. Volcano plots summarizing the differential expression between Mtb in 14-day HRZE treated and control mouse samples (d) and 28-day HRZE treated and control mouse samples (e). f. Estimated gene expression over time in mice. Genes that were significantly differentially expressed between at least two treatment time points are shown (N=2,429). Values are row-scaled, with red and blue indicating higher and lower expression, respectively. Hierarchical clustering of genes identified four broad patterns. g. Average log2 fold change for each of the four clusters relative to control. Values above and below zero represent up- and downregulation relative to control, respectively. h. Comparison of differential expression between mouse (day 28) or in vitro (day 8) relative to respective controls. Purple shading indicates genes with concordant fold-change direction and significance between mouse and in vitro experiments. Green shading indicates genes that were significant for either mouse or in vitro experiments but not both. Gold shading indicates genes that were significant for both mouse and in vitro experiments but in opposite directions. Gray shading indicates the genes that were not differentially expressed with HRZE treatment either in mouse or in vitro experiments. i. Comparison of fold-changes between mouse (day 28) or in vitro (day 8) relative to respective controls. Purple, green, gold, and gray colors have the same meaning as in h.

Efficacy of drug treatment

In mice, treatment with HRZE reduced the CFU burden by 99.8% by day 28 (7.63 to 4.82 log10 CFU). A newer marker, the RS ratio,10 declined more rapidly than CFU, indicating that interruption of rRNA synthesis occurs more rapidly than killing (Fig. 3c).

Global effect of HRZE on the Mtb transcriptome

In mice, treatment with HRZE transformed the Mtb transcriptome, significantly altering expression of 2,049 (57%) and 2,329 (65%) genes at day 14 and day 28 relative to pre-treatment control on day 0, respectively (Fig. 3d–e). A smaller set of genes (159 (4%)) was differentially expressed at day 28 relative to day 14. Hierarchical clustering identified clusters of genes with similar expression changes over time (Fig. 3f). The greatest transcriptional change occurred by day 14 (Fig. 3g, Clusters 2 and 4). A smaller subset of genes changed more gradually (Fig. 3g, Clusters 1 and 3). In vitro HRZE exposure also had a large impact on the Mtb transcriptome, altering expression of 2,748 (77%) and 2,800 (78%) of genes at day 4 and day 8 relative to control, respectively.

There were broad similarities as well as important differences between the effects of HRZE in mice and in vitro. Considering the effect of HRZE on gene expression at the latest treatment time points (8 days in vitro and 28 days in mice), differentially expressed genes were largely concordant between the mouse and in vitro samples (Fig 3h). However, eight days of HRZE in vitro induced overall larger fold-changes than 28 days of HRZE in mice (Fig. 3i). A notable subset of genes changed in discordant directions (colored gold in Fig. 3i), indicating differences between the effect of HRZE in mice and in vitro that are further described below.

Effect of HRZE on bacterial cellular processes

Since our primary focus is Mtb phenotypes that survive prolonged drug exposure, the remainder of this manuscript describes only expression changes at the latest time point (28 days in mice or 8 days in vitro) relative to control, unless otherwise noted. Differences between other time points can be evaluated via the Online Analysis Tool.

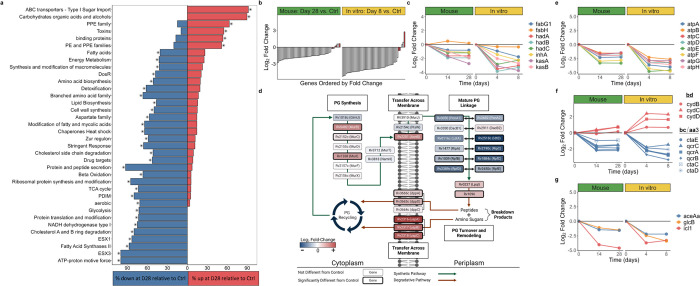

Genes significantly impacted by 28-day HRZE treatment in mice were enriched for 36 of the 124 functional gene sets (Table S3) evaluated in enrichment analysis. Figure 4a provides a global portrait of change in cellular processes.

Fig. 4. Summary of gene set enrichment and transcriptional changes in biological processes.

a. Gene categories significantly enriched for genes differentially expressed between day 28 and control murine samples. The percentage of genes in each category significantly up- (red) or down- (blue) regulated for each comparison is illustrated. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (adj-P<0.05). b. Fold-change of ribosomal protein genes in mice at day 28 (left) and in vitro (right) at day 8, relative to control. Red bars indicate the four alternative C-ribosomal protein paralogs. c, e-g Fold-change values in mice at days 14 and 28 (left) and in vitro (right) at days 4 and 8, relative to control for FAS-II (c), ATP synthetase (e), cytochrome bcc/aa3 supercomplex and the bd oxidase (f), and glyoxylate bypass (g) gene sets. d. Graphical representation of changes in the peptidoglycan synthesis, modification, and recycling pathways in mice at day 28 relative to control. Log2 fold-change values for genes in the process are indicated by the color of each box and the bolded outlines of boxes represent genes that are significantly differentially expressed. Figure adapted from Maitra et al., 2019.76 Image created with Biorender.com.

Growth and synthesis of macromolecules

A dominant effect of HRZE was decreased expression of categories associated with growth and synthesis of macromolecules. Genes coding for ribosomal proteins were profoundly suppressed after treatment in mice (adj-P=2.9×10−15) and in vitro (adj-P=1.0×10−14) relative to their respective controls (Fig. 4b), consistent with decreased ribosome synthesis, a process fundamentally coupled with bacterial replication.54,55 An exception to this pattern were the four alternative C-ribosomal protein paralogs lacking the zinc-binding CXXC motif that are a component of ribosomal remodeling. As shown in red in Figure 4b, genes for the alternative ribosomal proteins (rpmB1, rpsR2, rpsN2, rpmG1) had either sustained or significantly increased expression relative to control, consistent with ribosomal remodeling by a slowly replicating Mtb population.

Reduced protein synthesis was additionally suggested by decreased expression of the protein translation and modification category that includes genes responsible for translational initiation, promotion of tRNA binding, elongation, termination, and protein folding (adj-P=0.006 in mice, adj-P=0.007 in vitro). Concordant with downregulation of translation, transcription appeared suppressed, as evidenced by significant decrease in genes coding for gyrase A and B subunits (gyrA, gyrB) in mice and in vitro (least significant adj-P=1.8×10−5).

Cell-wall synthesis, remodeling, and recycling

Mycolic acids.

Slowing of the initial step of mycolic acid synthesis was suggested by decreased expression of Rv2524c (fas), the gene coding for fatty acid synthetase I (FAS-I), in mice (adj-P=1.7×10−9) and in vitro (adj-P=3.2×10−9) and by decreased expression of the fas transcriptional regulator Rv320856 in mice (adj-P=1.9×10−4) and in vitro (adj-P=1.1×10−11). Genes coding for the second step of elongation of acyl-coenzyme A to long chain fatty acids by fatty acid synthetase II (FAS-II) were also significantly decreased in both mice (adj-P=0.011) and in vitro (adj-P=0.027) (Fig. 4c). Finally, in Mtb treated with HRZE in mice and in vitro, there was decreased expression of the set of genes associated with elongation, desaturation, modification, and transport of the mature mycolic acids to the cell wall.

Phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIM).

Genes coding for PDIM biosynthesis, the outer surface glycolipids that are important for intracellular survival and virulence, were significantly downregulated in mice (adj-P=9.9×10−5) and in vitro (adj-P=0.017).

Peptidoglycan.

In contrast to the downregulation observed in mycolic acid and PDIM genes, key genes involved in peptidoglycan synthesis, modification, and recycling had increased expression. Specifically, all five peptidoglycan synthesis genes assayed in the division cell wall operon (ftsQ, murC, ftsW, murD, murR, murE) had significantly increased expression at 14 days of HRZE and three remained significantly upregulated at day 28 after HRZE treatment in mice (Online Analysis Tool). Active recycling was also suggested by significantly increased expression with HRZE treatment in mice and in vitro of genes coding for the UspABC amino-sugar importer and the DppABCD dipeptide importer that transport peptidoglycan breakdown products (Fig. 4d).57

Trehalose.

The TreY/Z genes that synthesize free trehalose from glycogen were significantly upregulated at all post-treatment time points in mice and in vitro. The other two trehalose synthesis pathways (OtsA/B and GlgE/TreS) were not differentially expressed with HRZE treatment in mice or in vitro. Remodeling of the trehalose component of the cell envelope was suggested by significantly increased expression of Rv3451 (cut3) under the test conditions in mice (adj-P=0.002) and in vitro (adj-P=4.2×10−4), which codes for a stress-responsive trehalose dimycolate hydrolase.58 Additionally, both mice and in vitro samples had significantly increased expression of four of the five genes for the LpqY/SugABC importer that is specific for the transport of trehalose.59

Metabolic readjustment

Electron transport and aerobic respiration.

The eight genes that collectively code for ATP synthetase were strongly suppressed in mice (adj-P=7.6×10−4) and in vitro (adj-P=.003) (Fig. 4e). Oxidative phosphorylation appeared to transition from the primary cytochrome bcc/aa3 supercomplex (downregulated) to the alternative less efficient cytochrome bd oxidase (upregulated) that has been implicated in persistence under environmental and drug stress60 (Fig 4f). Genes of the TCA cycle were downregulated with HRZE treatment in mice (adj-P=0.001) and in vitro (adj-P=0.010). Genes coding for NADH dehydrogenase types I and II and succinate dehydrogenase types I and II were also downregulated (Online Analysis Tool). By contrast, three of the four fumarate reductase genes were significantly induced by HRZE in mice, and all were induced in vitro.

Central carbon metabolism.

Slowing of the TCA cycle was not accompanied with increased expression of glyoxylate bypass genes, an alternative pathway previously implicated in drug tolerance.52 Instead, the gene for isocitrate lyase (icl1), the first step of the glyoxylate bypass, was among the most profoundly suppressed by HRZE both in mice (adj-P=1.9×10−37) and in vitro (adj-P=2.0×10−14) (Fig. 4g). The gene coding for the alternative isocitrate lyase (aceAa) was also significantly downregulated during HRZE treatment in mice (adj-P=7.3.x10−13) and in vitro (adj-P=3.x10−15). Genes associated with carbon storage as triacylglycerol had discordant regulation in mice and in vitro. Specifically, tgs1, a gene in the DosR regulon which codes for triacylglycerol synthase, decreased 4.4-fold (adj-P=7.0×10−13) in mice but increased 10.9-fold (adj-P=3.2×10−16) in vitro.

Cholesterol degradation

Although more highly expressed in mice than in vitro prior to drug exposure, genes related to cholesterol breakdown were suppressed by HRZE in mice and increased by HRZE in vitro (Fig 5a, significance of individual genes in Online Analysis Tool).

Fig. 5. Summary of transcriptional changes in biological processes.

a. Log2 fold-change values for genes in the cholesterol degradation pathway for mice at day 28 and in vitro at day 8, relative to control. Deeper red values represent higher upregulation of genes after drug treatment relative to control, while deeper blue values represent higher downregulation. Figure adapted from Pawełczyk et al., 202177. b-g. Fold-change in mice (left) and in vitro (right), relative to control for heat shock proteins (red bar represents hspX) (b), dosR (c), antigen 85 (d), ESX-1 (red bar represents esxA, blue bar represents esxB) (e), the Rv2686c-2688c efflux pump (f), and the DrrABC efflux pump (g) gene sets.

Glycerophosphodiesters.

The four genes coding for the UgpABCE transporter responsible for import of glycerophosphodiesters that are a major source of carbon and phosphate61 were strongly upregulated at both treatment time points in mice and in vitro (Online Analysis Tool).

Lipolytic enzymes

The complex repertoire of lipolytic enzymes that are implicated in Mtb dormancy and virulence includes Lipase family genes predicted based on sequences to have lipase/esterase activity. In mice, 11 of the lipase genes included in the SEARCH-TB assay had significantly increased expression, including lipY that codes for triacylglycerol lipase LipY. There was particularly strong induction of lipY in vitro (15.5-fold increase, P=1.2×10−35). Additionally, three of the four phospholipase C genes (plcA, plcB, plcC) were significantly upregulated in mice.

Canonical stress responses

Although the 14 heat shock proteins (HSPs) that act as chaperones in protein folding are often described as a stress response, expression of HSP genes largely decreased following HRZE exposure. A notable discordance between mice and in vitro results is the hypoxia-responsive hspX (arc) (noted in red in Fig. 5b) that had the greatest negative fold-change of all genes evaluated in mice (48.8-fold decrease, adj-P=4.8×10−57) yet was significantly upregulated in vitro (4.6-fold increase, adj-P=2.0×10−8). Concordant with the hspX result, we found that HRZE significantly decreased expression of the DosR regulon in mice (adj-P=0.032) but induced the DosR regulon in vitro (adj-P=2.2×10−7) (Fig. 5c). Genes of the stringent response, which is typically induced by nutrient deprivation and other environmental stresses, were significantly downregulated with HRZE treatment in mice (adj-P=2.9×10−15) and in vitro (adj-P=1.6×10−14) (Online Analysis Tool). Similarly, relA, the gene coding for the stringent response regulator was significantly decreased in mice (adj-P=2.0×10−6) and in vitro (adj-P=7.0×10−6).

Secretion of peptides and immunogenic proteins

Genes coding for the Antigen 85 complex, the major secreted protein that is essential for intracellular survival within macrophages62, were profoundly downregulated under the test conditions in mice (smallest fold-decrease=6.5, least-significant adj-P=3.1×10−24) and in vitro (smallest fold-decrease=14.2, least-significant adj-P=2.6×10−31) (Fig. 5d). Expression of the ESX-1 locus was downregulated (adj-P=9.4×10−5 in mice, adj-P=1.3×10−5 in vitro) with particularly strong suppression of esxA and esxB, genes coding for highly-immunogenic early secretory antigenic 6 kDa (ESAT-6) and culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10), in mice (smallest fold-decrease=10.0, least-significant adj-P=4.7×10−24) and in vitro (smallest fold-decrease=55.7, least-significant adj-P=2.4×10−35) (Fig. 5e). Expression of all 9 genes assayed in the ESX-3 locus was significantly downregulated with particularly strong suppression of immunogenic esxG and esxH in mice (smallest fold-decrease=18.5, least-significant adj-P=1.1×10−34) and in vitro (smallest fold-decrease=44.3, least-significant adj-P=4.0×10−32). In contrast, six of the seven genes in the ESX-4 locus that a recent review63 described as having “wholly unknown” function had significantly increased expression. Interestingly, the Sec-independent Tat system that exports pre-folded proteins had significantly increased expression of genes coding for the TatBC complex (tatB, tatC) but significantly decreased expression of the gene for the PMF-dependent TatA pore protein (tatA).

Efflux pumps

Most of the diverse set of transporters that includes putative drug efflux pumps had altered expression after HRZE exposure, but the direction of their regulation varied (Table S4). As examples, Rv2686c-2688c that is associated with fluoroquinolone tolerance64 was upregulated in mice and in vitro (Fig. 5f) but DrrABC that is associated with daunorubicin tolerance and appears in clinical drug-resistant strains64 was downregulated (Fig. 5g).

Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation

SEARCH-TB indicated large-scale regulatory reprogramming. For example, most of the 188 transcription factors assayed in mice changed after 28 days of HRZE treatment, with 66 significantly increased and 47 significantly decreased. The regulatory perturbation was even more pronounced in vitro with 87 significantly increased and 55 significantly decreased transcription factors after 8 days of HRZE treatment. Of the 12 sigma factor genes included in SEARCH-TB, sigF, sigI and sigM were significantly upregulated following HRZE treatment in both mice and in vitro. sigA, sigB, sigD and sigK were significantly downregulated in both mice and in vitro. Expression of sigC and sigL was significant in both mice and in vitro but in discordant directions, suggesting differing regulatory responses in vivo and in vitro.

HRZE appeared to activate the post-transcriptional toxin-antitoxin system that modulates the concentration of existing transcripts. Toxin genes had significantly increased expression in mice (adj-P=0.011) and in vitro (adj-P=0.027). The counter-regulatory antitoxins that restrict toxin activity were not categorically altered in mice but were significantly suppressed in vitro (adj-P=0.037).

Drug targets

Because processes that are upregulated following prolonged drug exposure may represent survival mechanisms that could be targeted to eradicate persisting Mtb, we evaluated genes that code for drug targets. Evaluation of targets of 31 existing drugs or investigational compounds (36 genes) (Table S5) were predominantly suppressed in mice (19 down-regulated and 3 upregulated) and in vitro (26 down-regulated and 2 upregulated). Notable exceptions to downregulation of drug targets were increased expression of the genes for Mur ligases B and C that initiate peptidoglycan synthesis in mice65 and increased expression of rfe, the gene for phosphoglycosyltransferases WecA that initiates arabinogalactan synthesis in mice and in vitro.66

Transcriptional differences between Mtb in mice and in vitro at final time points

After 8 and 28 days of HRZE treatment, the in vitro and murine Mtb transcriptomes were more similar than they were prior to HRZE exposure (Fig 3a). Nonetheless, 1,014 genes (28%) remained differentially expressed between the final murine and in vitro time points.

DISCUSSION

This work established the SEARCH-TB platform, a method for elucidating the Mtb transcriptome during drug exposure in vivo. After 28 days of treatment with the global standard 4-drug combination (HRZE) and 99.8% reduction in the burden of culturable Mtb in mouse lungs, SEARCH-TB indicated broad suppression of cellular activity including slowing of metabolism, synthesis of macromolecules and secretion of immune-modulating peptides. SEARCH-TB also suggested bacterial adaptation to drug stress, including a shift in electron transport to the alternative less efficient cytochrome bd oxidase, ribosomal remodeling, cell wall remodeling and recycling, and reprogramming of regulatory and efflux pump activity. The effects of HRZE in mice and in vitro had both broad similarities and notable differences that likely reflect effects of immunity and environment. As the first platform capable of nearly genome-wide quantification of extremely low abundance Mtb transcripts in mice, SEARCH-TB should enable highly granular evaluation of the effect of drugs and regimens in vivo.

Unsurprisingly, at baseline, prior to the start of HRZE treatment, SEARCH-TB indicated that Mtb cellular processes differed substantially between mice and early log phase growth, reflecting bacterial adaptation to immunity and the lung environment. These differences between untreated mouse and in vitro control are consistent with a recent review47 of the treatment-naïve in vivo Mtb transcriptome, both in terms of broad cellular processes (downregulation of genes associated with transcription, translation and metabolism in vivo) and specific adaptations (e.g., increased expression of genes of the DosR regulon, glyoxylate bypass genes). Importantly, the transcriptome of the untreated mouse was the starting point for our current analysis of drug effect. Combination antimicrobial treatment is a categorically different type of stress than environmental conditions such as pH, hypoxia, and nutrient starvation. Correspondingly, as highlighted in the discussion below, SEARCH-TB showed that drug exposure elicited transcriptional adaptations that often diverge from well-established transcriptional responses to environmental stress.

SEARCH-TB results indicated that a major effect of HRZE treatment in mice is suppression of Mtb growth and metabolism. Consistent with previous in vitro analyses of drug effects, transcription results suggested decreased synthesis of all major macromolecules, including rRNA, protein, lipids, and cell wall constituents. An additional manifestation of decreased bacterial activity was decreased protein and peptide secretion, including the ESX1 Type VII secretion system that exports the highly immunogenic ESAT-6 and CFP-10 proteins. This suggests that drug stress might alter the pathogen’s capacity to modulate host immunity.

Despite the broad downregulation of activity, SEARCH-TB provided evidence that drug-stressed Mtb is not inert or incapacitated. Increased expression of genes associated with peptidoglycan and trehalose synthesis and recycling suggested active cell wall modification. SEARCH-TB indicated broad transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory reprogramming and reconfiguration of efflux pump expression. HRZE appears to have induced reconfiguration of metabolism and energy generation away from high respiratory activity that maximizes ATP generation, and towards reduced respiratory efficiency and oxidative phosphorylation activity.

A striking finding was that HRZE led to significantly decreased expression of the DosR regulon in mice. DosR is the Mtb response to impaired aerobic respiration induced by hypoxia, nitric oxide, or carbon monoxide exposure.67 DosR was termed the “dormancy survival regulon” because impaired respiration leads to growth arrest. In mice, HRZE appeared to arrest growth yet expression of the DosR regulon was suppressed. We hypothesize that once 99.8% of culturable Mtb have been eliminated and secretion of immunogenic peptides, including Ag85, ESAT-6 and CFP-10, is diminished in the residual population, host immunity may be modulated. A less-intense inflammatory response would be predicted to decrease increase localized oxygen availability and decrease nitric oxide production, thereby diminishing induction of DosR-inducing conditions that restrict aerobic respiration. The hypothesis that DosR may be an indirect readout of immune response is consistent with our previous observation that the DosR regulation has significantly lower expression in TB patients with AIDS than in immunocompetent patients.33 Also consistent with this hypothesis was our finding that in vitro, in the absence of immunity, HRZE significantly increased rather than decreased expression of DosR genes.

Also notable was expression of the gene for isocitrate lyase, the first step of the glyoxylate bypass that is essential to establishing infection in animals.68–70 Consistent with these prior results, we found that icl1 was highly expressed in untreated mice relative to log phase growth. icl1 was also shown to have increased expression following sublethal exposure to rifampin, INH or streptomycin in vitro and was identified as a mediator of drug tolerance.52 By contrast, we found that treatment with lethal doses of HRZE strongly suppressed, rather than induced, expression of both icl1 and aceAa which codes for an alternative isocitrate lyase. This highlights, first, that adaptations associated with prolonged tolerance to HRZE differ from adaptations to host environments that enable persistent infection in the absence of drug therapy and, second, that the response to exposure to a combination regimen in vivo may differ from single drug exposure in vivo.

Drugs have historically targeted transcription, translation, and other growth-associated cellular processes71 that SEARCH-TB shows are downregulated after treatment with HRZE. While transcriptional downregulation of drug targets does not necessarily mean a drug will be ineffective, genes such as the Mur ligases that have increased expression after 1-month of HRZE treatment in vitro are noteworthy as they might indicate adaptations that enable Mtb to withstand drug exposure. Similarly, genes coding for the alternative bd oxidase that is a proposed drug target72 were upregulated at a time when nearly all other metabolism-associated genes had suppressed expression.

A novel comparison in this report is the effect of HRZE in the mouse versus in vitro. Although the physiologic state of Mtb appeared quite different in mice and in vitro at pre-treatment baseline, HRZE induced broadly similar changes in vivo and in vitro. The magnitude of fold-change was greater in vitro, potentially indicating a lower effective drug exposure in the mouse. Nonetheless, we also observed discordant transcriptional changes such as in expression of the DosR regulon, indicating that drug effect in vitro is not a simple surrogate for effect in the mouse. Furthermore, at the latest treatment endpoints, a large number of genes remained differentially expressed between in vitro and the mouse, likely indicating the importance of immunity and pharmacokinetics in the mouse.

As a highly granular readout of the effect of TB treatment on bacterial cellular processes, SEARCH-TB may improve precision of pharmacodynamic evaluation, providing greater information than the existing standard method of assessing drug effectiveness in vivo (i.e., culture-based enumeration of bacterial burden73). We have previously shown that CFU burden does not capture the entirety of complex drug effects in vivo. For example, regimens that have identical effects on CFU in mice can have different long-term relapse outcomes.10,74 In previous studies, we demonstrated that quantification of rRNA synthesis via the RS ratio showed proof of concept that molecular measures of bacterial cellular processes in vivo can distinguish regimens that are indistinguishable based on CFU.10,74 SEARCH-TB advances molecular characterization of drug effects in vivo to a higher level of granularity. Others have demonstrated the power of Mtb transcriptional readouts of drug effect to predict drug interactions in vitro.75 We believe that SEARCH-TB has potential to enable a new era of pharmacodynamic evaluation in which drug interactions and regimens are assessed based on molecular effects on cellular process in vivo.

This report has several limitations. First, between-target variation in the amplification efficiency of SEARCH-TB primers likely affects the rank-order of gene counts, meaning that, for individual genes, a higher absolute count does not necessarily indicate greater expression. However, because amplification is highly repeatable, the modest amplification bias identified does not affect estimation of differential expression between groups which is the primary purpose of SEARCH-TB. Indeed, we showed that SEARCH-TB provides the same biological interpretation as conventional RNA-seq. Second, specific and efficient primers could not be designed for ~12% of Mtb transcripts. Third, transcriptional profiling is inherently unable to resolve the enduring question of whether the drug-tolerant subpopulation that persists late into treatment results from selection (i.e., elimination of easily-killed Mtb) or physiological transformation of Mtb that were present at baseline. Finally, this initial demonstration of SEARCH-TB evaluated a single regimen (HRZE) in a single murine model. Important next steps include evaluation of individual drugs and diverse regimens in additional animal models.

SEARCH-TB enabled what to our knowledge is the first evaluation of the effect of prolonged drug treatment on Mtb transcription in animal models, revealing adaptations distinct from those observed under environmental stress. The Mtb subpopulation that survived one month of HRZE treatment appeared substantially less active than prior to treatment but was not inert with transcriptional changes suggesting adaptation for survival. SEARCH-TB should enable a new era of in vivo molecular pharmacodynamics with potential to accelerate identification of new highly potent regimens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

We are grateful to the Illumina Design Team that developed the custom primer pool used in SEARCH-TB.

Funding.

GR acknowledges funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-009105). NDW and RD acknowledge funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1170003). NDW and PN acknowledge funding from the US National Institutes of Health (1R01AI127300-01A1). NDW acknowledges funding from Veterans Affairs (1I01BX004527-01A1).

Data availability.

All raw sequencing data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession PRJNA939248. Individual samples have BioSample accession numbers SAMN33461189 through SAMN33461251.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2020. (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connolly L. E., Edelstein P. H. & Ramakrishnan L. Why is long-term therapy required to cure tuberculosis? PLoS Med. 4, e120 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchison D. A. Basic mechanisms of chemotherapy. Chest 76, 771–780 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jindani A., Aber V. R., Edwards E. A. & Mitchison D. A. The early bactericidal activity of drugs in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 121, 939–949 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jindani A., Doré C. J. & Mitchison D. A. Bactericidal and sterilizing activities of antituberculosis drugs during the first 14 days. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 1348–1354 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies G. R., Brindle R., Khoo S. H. & Aarons L. J. Use of nonlinear mixed-effects analysis for improved precision of early pharmacodynamic measures in tuberculosis treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 3154–3156 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter N. D. et al. Transcriptional adaptation of drug-tolerant Mycobacterium tuberculosis during treatment of human tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 212, 990–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balaban N. Q., Gerdes K., Lewis K. & McKinney J. D. A problem of persistence: Still more questions than answers? Nature Reviews Microbiology 11, 587–591 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchison D. A. Role of individual drugs in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 4, 796–806 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter N. D. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis precursor rRNA as a measure of treatment-shortening activity of drugs and regimens. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies G. R. Early clinical development of anti-tuberculosis drugs: Science, statistics and sterilizing activity. Tuberculosis 90, 171–176 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Knegt G. J. et al. Rifampicin-induced transcriptome response in rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 93, 96–101 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waddell S. J. et al. The use of microarray analysis to determine the gene expression profiles of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in response to anti-bacterial compounds. Tuberculosis 84, 263–274 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boshoff H. I. M. et al. The transcriptional responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to inhibitors of metabolism: Novel insights into drug mechanisms of action. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40174–40184 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson M. et al. Exploring drug-induced alterations in gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microarray hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 12833–12838 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deb C. et al. A novel in vitro multiple-stress dormancy model for Mycobacterium tuberculosis generates a lipid-loaded, drug-tolerant, dormant pathogen. PLoS One 4, e6077 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betts J. C., Lukey P. T., Robb L. C., McAdam R. A. & Duncan K. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 717–731 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keren I., Minami S., Rubin E. & Lewis K. Characterization and transcriptome analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persisters. MBio 2, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honeyborne I. et al. Profiling persistent tubercule bacilli from patient sputa during therapy predicts early drug efficacy. BMC Med. 14, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma S. et al. Transcriptome analysis of mycobacteria in sputum samples of pulmonary tuberculosis patients. PLoS One 12, e0173508 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gautam U. S., Mehra S. & Kaushal D. In-vivo gene signatures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in C3HeB/FeJ mice. PLoS One 10, e0135208 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai R. P. J. et al. Transcriptomic characterization of tuberculous sputum reveals a host Warburg effect and microbial cholesterol catabolism. MBio 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garton N. J. et al. Cytological and transcript analyses reveal fat and lazy persister-like bacilli in tuberculous sputum. PLoS Med. 5, 0634–0645 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talaat A. M., Lyons R., Howard S. T. & Johnston S. A. The temporal expression profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 4602–4607 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockwood N., Lai R. P. J., Seldon R., Young D. B. & Wilkinson R. J. Variation in pre-therapy levels of selected Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcripts in sputum and their relationship with 2-month culture conversion. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 106 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pisu D., Huang L., Grenier J. K. & Russell D. G. Dual RNA-seq of Mtb-infected macrophages in vivo reveals ontologically distinct host-pathogen interactions. Cell Rep. 30, 335–350.e4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudock T. A. et al. Hypoxia sensing and persistence genes are expressed during the intragranulomatous survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 56, 637–647 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karakousis P. C., Williams E. P. & Bishai W. R. Altered expression of isoniazid-regulated genes in drug-treated dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61, 323–331 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bukka A., Price C. T. D., Kernodle D. S. & Graham J. E. Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA expression patterns in sputum bacteria indicate secreted Esx factors contributing to growth are highly expressed in active disease. Front. Microbiol. 2, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gautam U. S. et al. DosS is required for the complete virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice with classical granulomatous lesions. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 52, 708–716 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coppola M. et al. New genome-wide algorithm identifies novel in-vivo expressed Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens inducing human t-cell responses with classical and unconventional cytokine profiles. Sci. Rep. 6, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia B. J. et al. Sputum is a surrogate for bronchoalveolar lavage for monitoring Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcriptional profiles in TB patients. Tuberculosis 100, 89–94 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter N. D. et al. Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to impaired host immunity in HIV-infected patients. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 1205–1211 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skvortsov T. A., Ignatov D. V., Majorov K. B., Apt A. S. & Azhikina T. L. Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcriptome profiling in mice with genetically different susceptibility to tuberculosis. Acta Naturae 5, 62–69 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaikh A. et al. Early phase of effective treatment induces distinct transcriptional changes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis expelled by pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–13 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornejo-Granados F. et al. Targeted RNA-seq reveals the M. tuberculosis transcriptome from an in vivo infection model. Biology (Basel). 10, 848 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Betin V. et al. Hybridization-based capture of pathogen mRNA enables paired host-pathogen transcriptional analysis. Sci. Rep. 9, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Love M. I., Huber W. & Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J. & Smyth G. K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarthy D. J., Chen Y. & Smyth G. K. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 4288–4297 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benjamini Y. & Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murtagh F. & Legendre P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: Which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? J. Classif. 31, 274–295 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Federico A. & Monti S. HypeR: An R package for geneset enrichment workflows. Bioinformatics 36, 1307–1308 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cole S. T. et al. Erratum: Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 396, 190 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2021).

- 46.Chang W. et al. shiny: Web application framework for R. (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kundu M. & Basu J. Applications of transcriptomics and proteomics for understanding dormancy and resuscitation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Frontiers in Microbiology 12, 642487 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voskuil M. I. et al. Inhibition of respiration by nitric oxide induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy program. J. Exp. Med. 198, 705–713 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voskuil M. I., Bartek I. L., Visconti K. & Schoolnik G. K. The response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Front. Microbiol. 2, 105 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kendall S. L. et al. Cholesterol utilization in mycobacteria is controlled by two TetR-type transcriptional regulators: kstR and kstR2. Microbiology 156, 1362–1371 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reddy P. V. et al. Disruption of mycobactin biosynthesis leads to attenuation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for growth and virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 1255–1265 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nandakumar M., Nathan C. & Rhee K. Y. Isocitrate lyase mediates broad antibiotic tolerance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 5, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sirakova T. D. et al. Identification of a diacylglycerol acyltransferase gene involved in accumulation of triacylglycerol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis under stress. Microbiology 152, 2717–2725 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gourse R. L., Gaal T., Bartlett M. S., Appleman J. A. & Ross W. rRNA transcription and growth rate-dependent regulation of ribosome synthesis in Escherichia coli. Annual Review of Microbiology 50, 645–677 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maitra A. & Dill K. A. Bacterial growth laws reflect the evolutionary importance of energy efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 406–411 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mondino S., Gago G. & Gramajo H. Transcriptional regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 372–387 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fullam E., Prokes I., Fütterer K. & Besra G. S. Structural and functional analysis of the solute-binding protein UspC from Mycobacterium tuberculosis that is specific for amino sugars. Open Biol. 6, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Y. et al. A hydrolase of trehalose dimycolate induces nutrient influx and stress sensitivity to balance intracellular growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe 15, 153–163 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalscheuer R., Weinrick B., Veeraraghavan U., Besra G. S. & Jacobs W. R. Trehalose-recycling ABC transporter LpqY-SugA-SugB-SugC is essential for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 21761–21766 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mascolo L. & Bald D. Cytochrome bd in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A respiratory chain protein involved in the defense against antibacterials. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 152, 55–63 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fenn J. S. et al. Structural basis of glycerophosphodiester recognition by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis substrate-binding protein ugpb. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 1879–1887 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karbalaei Zadeh Babaki M., Soleimanpour S. & Rezaee S. A. Antigen 85 complex as a powerful Mycobacterium tuberculosis immunogene: Biology, immune-pathogenicity, applications in diagnosis, and vaccine design. Microbial Pathogenesis 112, 20–29 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gröschel M. I., Sayes F., Simeone R., Majlessi L. & Brosch R. ESX secretion systems: Mycobacterial evolution to counter host immunity. Nature Reviews Microbiology 14, 677–691 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Remm S., Earp J. C., Dick T., Dartois V. & Seeger M. A. Critical discussion on drug efflux in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 46, 1–15 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shinde Y., Ahmad I., Surana S. & Patel H. The Mur enzymes chink in the armour of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 222, 113568 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huszár S. et al. N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate transferase, WecA, as a validated drug target in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Voskuil M. I. Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression during environmental conditions associated with latency. Tuberculosis 84, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gould T. A., Van De Langemheen H., Muñoz-Elías E. J., McKinney J. D. & Sacchettini J. C. Dual role of isocitrate lyase 1 in the glyoxylate and methylcitrate cycles in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 940–947 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McKinney J. D. et al. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406, 735–738 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muñoz-Elías E. J. & McKinney J. D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 are jointly required for in vivo growth and virulence. Nat. Med. 11, 638–644 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shetye G. S., Franzblau S. G. & Cho S. New tuberculosis drug targets, their inhibitors, and potential therapeutic impact. Translational Research 220, 68–97 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee B. S., Sviriaeva E. & Pethe K. Targeting the cytochrome oxidases for drug development in mycobacteria. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 152, 45–54 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gumbo T., Lenaerts A. J., Hanna D., Romero K. & Nuermberger E. Nonclinical models for antituberculosis drug development: A landscape analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 211, S83–S95 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dide-Agossou C. et al. Combination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RS ratio and CFU improves the ability of murine efficacy experiments to distinguish between drug treatments. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 66, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ma S. et al. Transcriptomic signatures predict regulators of drug synergy and clinical regimen efficacy against tuberculosis. MBio 10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maitra A. et al. Cell wall peptidoglycan in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An Achilles’ heel for the TB-causing pathogen. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 43, 548–575 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pawełczyk J. et al. Cholesterol-dependent transcriptome remodeling reveals new insight into the contribution of cholesterol to Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw sequencing data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession PRJNA939248. Individual samples have BioSample accession numbers SAMN33461189 through SAMN33461251.