Abstract

The urinary bladder harbors a community of microbes termed the urobiome, which remains understudied. In this study, we present the urobiome of healthy infant males from samples collected by transurethral catheterization. Using a combination of extended culture and amplicon sequencing, we identify several common bacterial genera that can be further investigated for their effects on urinary health across the lifespan. Many genera were shared between all samples suggesting a consistent urobiome composition among this cohort. We note that, for this cohort, early life exposures including mode of birth (vaginal vs. Caesarean section), or prior antibiotic exposure did not influence urobiome composition. In addition, we report the isolation of culturable bacteria from the bladders of these infant males, including Actinotignum schaalii, a bacterial species that has been associated with urinary tract infection in older male adults. Herein, we isolate and sequence 9 distinct strains of A. schaalii enhancing the genomic knowledge surrounding this species and opening avenues for delineating the microbiology of this urobiome constituent. Furthermore, we present a framework for using the combination of culture-dependent and sequencing methodologies for uncovering mechanisms in the urobiome.

Keywords: Urobiome, pangenome, urinary tract infection, pediatric urology, urinary microbiome

1. Introduction

Until the past decade, it was presumed that the healthy urinary bladder was a sterile environment. However, advances in genetic sequencing and extended culture methodologies have uncovered a resident microbiota of the bladder, and this community has been termed the urobiome1,2. Since the discovery of the urobiome, several studies have demonstrated connections between urobiome dysbiosis and a variety of genitourinary diseases, including nephrolithiasis, recurrent UTIs (rUTIs), female urinary urge incontinence (UUI), male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), and bladder cancer3–7. However, despite a decade of research on the urobiome, little progress has been made to understand the development of the urobiome and the mechanistic interactions of the urobiome with urinary pathogens.

To begin to address the question of urobiome development, several studies have investigated the urobiome of children8–12. However, these studies sampled pediatric subjects with a variety of pre-existing urinary tract diseases or infection, which was the indication for urinary catheterization. For a variety of other anatomic niches, including the skin and gastrointestinal tract, early life development of the resident microbiota shapes future microbial diversity and susceptibility to disease13. Therefore, defining the development of the healthy pediatric urobiome is a vital endeavor. To bridge this gap in the field and investigate the urinary microbiome of healthy infants, we collected catheterized urine samples under sterile operating room conditions at the time of circumcision of male infants under one year of age. Notably, none of the subjects had structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities, or prior urinary tract infection. Thus, our study represents the first investigation of the healthy infant urobiome, albeit limited to the male gender. We provide evidence of a detectable and culturable urobiome of healthy infant males. Using complementary approaches of extended culture and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, we report a diverse and consistent urobiome signature in infant males that does not appear to be perturbed by early life exposures, such as mode of delivery (vaginal vs. Caesarean section) or prior antibiotic exposure for non-urinary infections. Among the urobiome residents cultured, we report Actinotignum schaalii as a species of interest, because of its prevalence in both the adult and pediatric urobiomes2,8,14–18 and its implication as a uropathogen in certain patient populations19–21. To facilitate future mechanistic work on this urobiome member, we provide whole genome sequencing information of nine independent strains of A. schaalii.

Research investigations of the urobiome are still within their first decade. As ongoing research continues to define the urinary microbiome, standardized methods and reporting are vital22. Given the low biomass of the urinary microbiome, the potential for contamination during sample collection, processing and analysis is high. In this work, we utilize both culture-dependent and independent methodologies to assess the infant urobiome. We present rigorous sampling and processing controls to benchmark the potential contaminants introduced during sample collection and processing. We include extensive methodological, bioinformatic, and statistical documentation to promote accessibility and reproducibility within the nascent urobiome field.

2. Materials And Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Sample Collection

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB # 191815). Parental guardians provided written informed consent for sterile urinary catheterization under anesthesia in the operating room prior to the circumcision procedure. Exclusion criteria included structural or functional genitourinary abnormalities, prior urinary tract infection, or prior urethral catheterization. Urine samples were collected by transurethral catheterization following sterilization of the glans penis and foreskin. Urine samples were stored in sterile Falcon tubes and immediately placed on ice for transport to permanent storage. Within 2 hours of collection, urine samples were transferred to an −80°C freezer for indefinite storage.

2.2. Extended Culture

Prior to freezing urine samples, 100mL of urine was spread onto Columbia Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (BD BBL™ 221263) and Brucella Agar (Thermo Scientific™ R01255). Duplicate plates were incubated in aerobic and anaerobic conditions (anaerobiosis was attained using BD GasPak™ EZ anaerobe pouch system). Negative control plates of each respective agar were incubated simultaneously. Plates were incubated for up to 5 days at 37°C. Aerobic conditions included 5% CO2 atmosphere. Colonies were analyzed by MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltonics), and colony identification performed pyrochemically by MALDI Biotyper® (Bruker Corporation) with an extended research-use taxonomic library. Glycerol stocks were frozen for each unique colony isolated.

2.3. Amplicon 16S rRNA Sequencing

Urine samples were shipped on ample dry ice to University of California at San Diego Microbiome Center for DNA extraction and sequencing. DNA was extracted using the ThermoFisher MagMAX™ Microbiome Ultra Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (A42357) from 500mL of sample. To benchmark DNA extraction efficiency, ten-fold serial dilutions of ZymoBIOMICS™ Microbial Community Standard (D6300) were extracted in parallel with urine samples. Following DNA extraction, the V4 hypervariable 16S rRNA region was amplified using the 515F and 806R primers from the Earth Microbiome Project23. To benchmark PCR amplification of 16S rRNA, ten-fold serial dilutions of ZymoBIOMICS™ Microbial Community DNA Standard (D6306) were amplified in parallel with extraction standards and urine samples. Additionally, negative control wells (extraction blanks) lacking sample input were subjected DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing. Further description of the methods and controls is available in the Supplementary Methods.

2.4. 16S rRNA Sequencing Analysis

All sequencing processing and analyses were completed in R (version 4.2.1). Sequences were processed using DADA2 to trim, filter, learn error rates, denoise, merge, and remove chimeras from reads24. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were assigned to merged reads with the SILVA rRNA database (version 138.1) using the DADA2 function assignTaxonomy. ASVs were merged with their taxonomy in the R package phyloseq25. The R package Decontam was used to identify and remove potential contaminant ASVs using the prevalence method and a threshold of 0.3. This threshold was chosen after evaluating the removal of contaminating ASVs of the ZymoBIOMICS™ Microbial Community Standard dilution series (Supplementary Methods). The R packages microbiome, microViz, and vegan were used to format and visualize the 16S rRNA data.

2.5. DNA Extraction from Actinotignum schaalii and Whole Genome Sequencing

Colonies of A. schaalii were resuspended in PBS, lysed with a combination of lysostaphin, lysozyme, and Proteinase K at 37°C. Next, the suspension was treated with RNase. Following dilution of the lysate in H2O, the mixture was sonicated at 34 kHz for 4 minutes. DNA was purified with three successive extractions in phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). Finally, DNA was precipitated from ethanol and resuspended in H2O. DNA was sent on dry ice to SeqCenter (formerly, Microbial Genomic Sequencing Center, Pittsburgh, PA). Sample libraries were prepared using the Illumina DNA Prep kit and IDT 10bp UDI indices, and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 2000, producing 2×151bp reads. Demultiplexing, quality control and adapter trimming was performed with bcl-convert (v3.9.3).

2.6. Actinotignum schaalii Sequencing Analysis

Trimmed reads were assembled into contigs >1000bp using Shovill (v. 1.1)26. Contigs were annotated with Bakta using default settings27. Annotated files were analyzed by Roary to construct the core genome and pangenome28. Anvi’o was used to visualize the pangenome, calculate average nucleotide identity, and visualize a phylogenetic tree29,30. Contigs were reformatted into anvi’o format and annotated with the COG20 database31. Functional enrichment of the core and accessory genomes were calculated using anvi’o pangenome summarize function. ABRicate was used to determine the presence of antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors on the unannotated contigs. ResFinder (v. 4.0), MegaRes (v. 3.0), and VirulenceFinder Database (VFDB, v. 5). were used as the reference databases of ABRicate. Contigs were uploaded to the antiSMASH online interface and analyzed with antiSMASH beta version 7.0 which includes an updated algorithm for the prediction of non-ribosomal peptide produced metallophores32,33. antiSMASH settings were relaxed detection strictness, and KnownClusterBLAST, MIBig cluster comparison34, and Cluster Pfam analysis.

3. Results

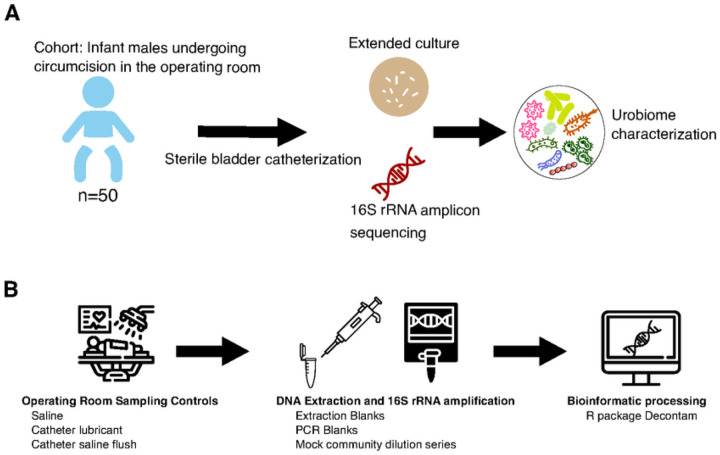

This study aimed to bridge a gap in our knowledge of the healthy pediatric urobiome. Our study prospectively enrolled 50 healthy male infants that underwent urinary catheterization during routine operative circumcision (Figure 1A). Below, we describe the pipeline we established to increase rigor and reproducibility within urobiome research, followed by a description of our findings.

Figure 1. Study Schematic and Analysis Workflow.

A) Illustration of study design. Fifty male infants were sterilely catheterized in the operating theatre prior to undergoing circumcision. Urine was immediately plated for extended quantitative urine culture (EQUC). DNA was extracted from urine samples, amplified with V4 16S rRNA primers, and sequenced using Illumina paired-end chemistry. The combination of urine culture and sequencing results was used to describe the urobiome composition. B) Illustration of analysis workflow and evaluation of potential contaminant sources. Sampling controls were collected contemporaneously with urine samples in the operating theatre. Extraction blanks and a mock microbial community dilution series were used to benchmark DNA extraction. No template blanks were subjected to 16S rRNA PCR amplification to benchmark PCR amplification. All controls mentioned were subjected to Illumina paired-end sequencing. The Decontam package in R was used to filter potential contaminant sequences.

Establishing Methodology for Low Biomass Urine Samples from Infants

The method of sample collection is a key concern in urobiome research. Genital and intestinal contaminants confound urobiome results22. To obtain sterile catheterized samples from healthy infants, we selected the population of infant males undergoing circumcision in the operating room. Informed consent for bladder catheterization was obtained from parental guardians. We collected urine from 50 male infants following induction of general anesthesia and sterilization of the periurethral area. The median age of the infants was 215 days (~7 months old, Table 1). The average amount of urine collected was 5.81 mL (range 0.4–28mL). Urine was immediately plated for extended quantitative urine culture (EQUC) as described in the methods to isolate and identify culturable bacteria. For sequencing, aliquots of the same urine were immediately frozen at −80°C to prevent microbial growth or contamination prior to processing for sequencing.

Table 1.

Cohort Details

| Participants (n) | 50 |

| Median age (days) at Sample Collection (IQR) | 215 (190, 252) |

| Male sex | 100% |

| Birth History | |

| Caesarean section | 27 (54%) |

| Preterm | 18 (36%) |

| NICU following birth | 18 (36%) |

| Health Exposures | |

| Prior antibiotic exposure | 12 (24%) |

| Type of Nutrition | |

| Breast Milk only | 5 (10%) |

| Formula | 19 (38%) |

| Breast Milk and Formula | 15 (30%) |

| Solids or Puree | 11 (22%) |

| Urine Collection | |

| Volume of urine (mean, range) | 5.81 mL (0.4–28 mL) |

We modified existing EQUC urobiome protocols to preserve urine volume for DNA extraction2. We utilized two non-selective agar media (blood agar and Brucella agar) plated in duplicate and incubated under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Aliquots of the same urine were subjected to DNA extraction using a commercially available kit which utilizes bead beating and DNA binding by magnetic beads for DNA isolation and purification. Isolated DNA was amplified using standardized PCR primers for the V4 region of the 16S rRNA. 16S rRNA amplicons were sequenced by Illumina paired-end sequencing.

The urobiome is a low biomass environment. There are myriad potential sources of contamination, a concern which is accentuated for low biomass samples. Contamination can be introduced at any step of sample processing, from sample collection to DNA extraction and amplification to sequencing35–37. We utilized three types of negative controls: 1) DNA extraction blanks; 2) no template PCR amplification blanks; and 3) sampling controls (Figure 1B). Specifically, we included eight DNA extraction blanks which underwent all steps of DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing. We included four no DNA template blanks during PCR amplification of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA. Finally, we included three types of sampling controls (operating theatre saline, mineral oil used for catheter lubrication, and saline flushed through a sterile catheter); four sets of which were collected on separate days. To our knowledge, this is the first urobiome study to report sampling controls collected contemporaneously with urine samples.

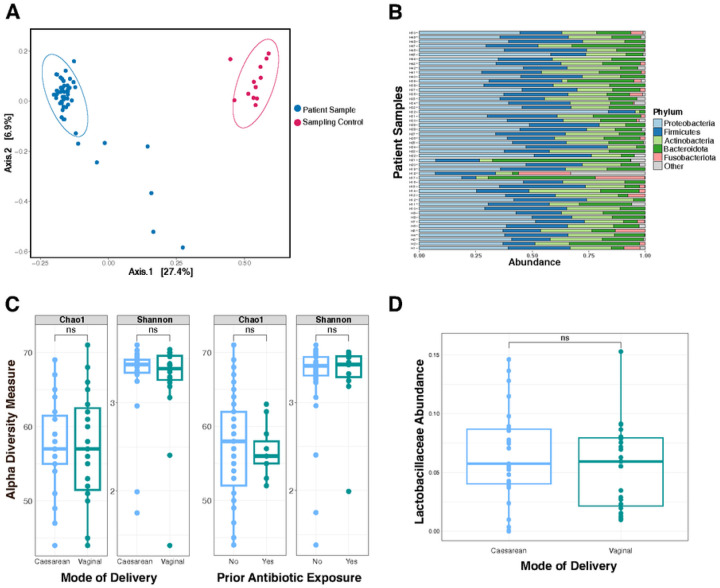

We sequenced sampling controls on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 to add additional resolution to rare contaminant sequences and due to sequencing equipment availability. Urine samples were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq. Notably, all samples and controls were processed in the same laboratory using the same reagents. To account for the different read numbers between MiSeq and NovaSeq platforms, we utilized a dilution series of a mock microbial community. Sampling controls had consistently higher 16S rRNA reads than extraction blanks. All sample read counts are shown in Supplementary Table S1. We applied the R package Decontam to remove sequences that were more prevalent in the blank extraction controls or PCR blanks compared to the sampling controls. A total of 37 specific genera were retained following filtering using Decontam. The most prevalent genera present in the sampling controls were Campylobacter, Rodentibacter, Mannheimia, Alloprevotella (Supplementary Table S2). The sampling controls (n=12) clustered distinctly from the subjects’ samples (n=50) (PERMANOVA p=0.001) (Figure 2A). Nonetheless, the number of 16S rRNA reads in sampling controls indicates that this is a potential source of contamination that must be accounted for within urobiome studies.

Figure 2. 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Reveals a Consistent Urobiome Composition.

A) Beta diversity between infant urine samples and sampling controls. Beta diversity was calculated by the phyloseq “ordinate” function using Bray-Curtis distances. Urine samples were significantly different than sampling controls by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, p=0.001). PERMANOVA was calculated using the vegan function “adonis2”. B) Phyla-level taxonomic profiles of urine samples from 50 infants. Urine samples are depicted along the vertical axis and taxonomic relative abundance on the x-axis. Plot created with the microViz function “comp_barplot”. C) Alpha diversity metrics (Shannon index and Chao1) between urine from infants born by vaginal delivery vs. Caesarean section (left); and between urine from infants previously exposed to antibiotics vs. antibiotic naïve (right). Alpha diversity was calculated within the phyloseq package using the “plot_richness” function. Alpha diversity was not significant different between groups by Wilcoxin rank sum test (p>0.05). D) Relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae in urine samples between infants born by vaginal delivery vs. Caesarean section. The Lactobacillaceae family was agglomerated with the phyloseq command “tax_glom”. There was no significant difference in Lactobacillaceae abundance between groups by Wilcoxin rank sum test (p>0.05).

Characterizing the Urobiome by Amplicon Sequencing

Prior urobiome studies2,38 have used agarose gel electrophoresis to determine “negative samples” following 16S rRNA amplification (and thus excluded those samples from sequencing). The absence of a band in gel electrophoresis to determine negative samples has a false negative rate of 30% and should be avoided when sampling low biomass environments39. We subjected all samples to 16S rRNA amplification and sequencing. Every subject’s sample had higher sequencing reads than blank extraction controls. The range of merged non-chimeric 16S rRNA reads in the subjects’ samples from Illumina MiSeq sequencing was 6604–60040 reads compared to 2345–4149 reads in the extraction blank controls (Supplementary Table S1). We used the R package Decontam to identify potential contaminants which were sequences more prevalent in the negative controls than the urine samples. Given the different library sizes and readily apparent compositional differences (Figure 2A), we did not apply Decontam to remove sampling controls from subject samples. Next, we filtered ASVs less than 1% abundance in the whole subject dataset. This threshold has previously been applied to urobiome datasets7. Supplementary Table S3 includes all taxa from subject urine samples identified by 16S rRNA sequencing with literature citations regarding prior detection in urobiome studies.

Following above-described filtering steps, there were 74 unique taxa remaining from the urine samples (Supplementary Table S4). Consistent with prior reports, the phyla Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroides, and Actinobacteria were frequently detected (Figure 2B)40. The genera shared between subject samples and sampling controls were Campylobacter, Staphylococcus, Nocardiopsis, Halomonas, Saccharopolyspora, Vibrio, Porphyromonas, Rheinheimera, Cloacibacterium, and Anaerobacillus. Urine samples had a median of 41 unique genera (range 32–57). Six genera were detected in all 50 subject urine samples: Staphylococcus, Nocardiopsis, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Corynebacterium, and Nesterenkonia. Three genera were found in 49 of the 50 samples: Aliihoeflea, Saccharopolyspora, and Sphingobacterium. Three genera were found in 48 of the 50 samples: Escherichia-Shigella, Lactobacillus, and Halomonas. The most abundant genera were Nocardiopsis, Staphylococcus, Escherichia-Shigella (median abundance >5%); five additional genera had median abundance >3%: Lactobacillus, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Prevotella, and Lacibacter.

We sought to investigate whether various subject exposures influenced the diversity of the urobiome. Measures of community diversity are commonly used to summarize information about the richness and distribution of microbials species in the community41. We compared two measures of alpha diversity (Chao1, Shannon) for two subject exposures: mode of birth (vaginal delivery vs. Caesarean section) and prior antibiotic exposure (Figure 2C). While both of these exposures are known to alter the gastrointestinal and skin microbiota of infants42, no significant difference in alpha diversity was detected in the urine samples between either exposure (Figure 2C).

Next, we sought to determine whether specific taxa are influenced by subjects’ exposures. We selected the taxonomic family Lactobacillaceae which was present in variable amounts in the 50 subjects.Lactobacillaceae are well studied members of the urogenital microbiota, particularly in post-pubescent women43,44. Lactobacillaceae are transferred to infants during vaginal birth, and intestinal abundance of Lactobacillaceae are decreased in infants born by Caesarean section45. We compared Lactobacillaceae abundance between infants born by vaginal birth vs. Caesarean section (Figure 2D). There was no significant difference inLactobacillaceae abundance between these groups. Together, these data display a detectable and consistent urobiome among infant males. Twelve genera were detected in ≥48 of the 50 urine samples. Early life exposures, such as mode of birth and prior antibiotic exposure, did not significantly influence urobiome composition.

Expanded Quantitative Urine Culture Identifies Culturable Members of the Infant Urobiome

To facilitate future mechanistic studies between urobiome members and the urothelium, or uropathogenic bacteria, we designed an extended quantitative urine culture (EQUC) protocol with the goal of capturing as many bacteria as possible using limited urine volume from infants. Indeed, 32/50 (64%) of urine samples led to identifiable growth on one or more of the media and conditions. This percentage is consistent with several prior urobiome studies utilizing extended culture across the human lifespan1,2,8,14. Colony identification was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry. Among the 12 sampling controls, only 1 colony grew from extended culture, Cutibacterium acnes, a likely skin contaminant. This suggests that the 16S rRNA reads observed in the sampling controls were due to residual DNA, not viable bacteria.

The species identified by extended culture are listed in Table 2. The range of unique species was 1–5 per urine sample. The most common taxonomic families detected were Actinomycetaceae (n=15), Peptoniphilaceae(n=7), and Enterococcaceae(n=6). The most common species isolated were Actinotignum schaalii (n=9), Enterococcus faecalis (n=6), and Peptoniphilus harei (n=5).

Table 2.

Extended Quantitative Urine Culture

| Species | Number of Isolates |

|---|---|

| Actinomyces europaeus | 1 |

| Actinomyces naeslundii | 1 |

| Actinomyces odontolyticus | 1 |

| Actinomyces radingae | 1 |

| Actinomyces turicensis | 2 |

| Actinotignum schaalii | 9 |

| Aerococcus urinae | 1 |

| Alloscardovia ommnicolens | 1 |

| Anaerococcus spps. | 1 |

| Bacillus cereus | 1 |

| Bifidobacterium breve | 1 |

| Bifidobacterium dentium | 1 |

| Bifidobacterium longum | 1 |

| Citrobacter koseri | 1 |

| Clostridium sordelli | 1 |

| Clostridium tertium | 1 |

| Corynebacterium aurimucosum group | 1 |

| Corynebacterium spps. | 1 |

| Cutibacterium acnes | 2 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 6 |

| Escherichia coli | 2 |

| Finegoldia magna | 1 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 |

| Murdochiella asaccharolytica | 2 |

| Paenibacillus spps. | 1 |

| Peptoniphilus harei | 5 |

| Peptostreptococcus anaerobius | 1 |

| Prevotella corporis | 1 |

| Prevotella spps. | 1 |

| Prevotella timonensis | 1 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 |

| Rauotella ornithinolytica | 1 |

| Rothia aeria | 1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 |

| Staphylococcus capitis | 1 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 1 |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 2 |

| Streptococcus mitis oralis | 3 |

| Streptococcus salivarius | 1 |

| Streptococcus vestibularis | 1 |

| Trueperella bernardiae | 1 |

| Veillonella parvula group | 2 |

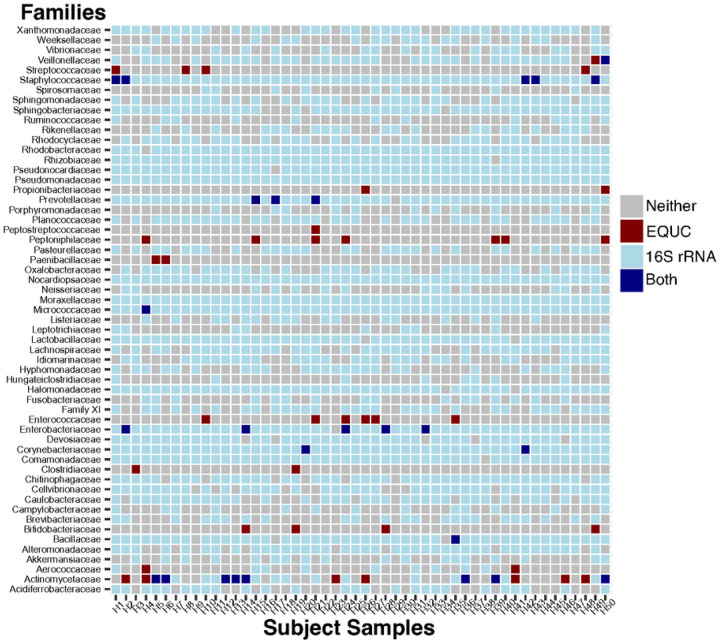

Extended culture and amplicon sequencing are complementary but not strictly equivalent approaches. We created a concordance map that displays which taxonomic families were detected by EQUC, 16S rRNA sequencing, or both (Figure 3). We included families detected in >0.1% relative abundance in the 16S rRNA dataset. There were a total of 49 taxonomic families across the 50 subjects’ urine samples. The family Actinomycetaceae was the most frequently detected family by EQUC and exhibited a high level of concordance with 16S rRNA results.

Figure 3. Concordance between EQUC and Amplicon Sequencing Results.

Co-occurrence detection patterns of taxonomic families between EQUC and amplicon sequencing methodologies. Taxonomic families are arranged vertically and patient samples horizontally. The rectangles indicate the detection of the family by EQUC (maroon), 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing (light blue), both methodologies (dark blue), or neither methodology (gray).

We inspected the concordance map for taxonomic families disproportionately represented in either EQUC or 16S rRNA results. The families Moraxellaceae, Nocardiopsaceae, Pseudomonadaceae were detected in all urine samples by 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, but not by EQUC. Similarly, the physiologically important family Lactobacillaceae was frequently detected by amplicon sequencing but not isolated by EQUC. The families Bifidobacteriaceae, Enterococcaceae, Peptoniphilaceae, Streptococcaceae were detected >3 times by EQUC but not present in the 16S rRNA results. These discordances highlight potential limitations of each method and the importance complementary approaches for sampling the urobiome.

Actinotignum schaalii is a Common Culturable Constituent of the Infant Urobiome

Actinotignum schaalii was the most common species identified in our extended culture and exhibited high concordance with the 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing results. Of the 32 urine samples that grew at least one bacterial species, nine (28.1%) grew A. schaalii. A. schaalii (formerly Actinobaculum schaalii) has been detected in numerous urobiome studies to date2,8,14–18,46. Intriguingly, in addition to being reported in this study and others as an asymptomatic colonizer of the urobiome, A. schaalii is also an opportunistic causative agent of urinary tract infections47. Specifically, there is concern of an increasing incidence of A. schaalii urinary tract infections19–21. Given the relatively fastidious growth requirements of A. schaalii, standard clinical microbiological techniques may not detect A. schaalii from urine samples21,48,49, highlighting the need to broaden our understanding of A. schaalii in the urinary tract. To date, genome analysis of A. schaalii has been limited to genome announcements without comprehensive analysis50. To expand our understanding of A. schaalii, we performed whole-genome sequencing on nine separate A. schaalii isolates identified by extended culture of urine from male infants.

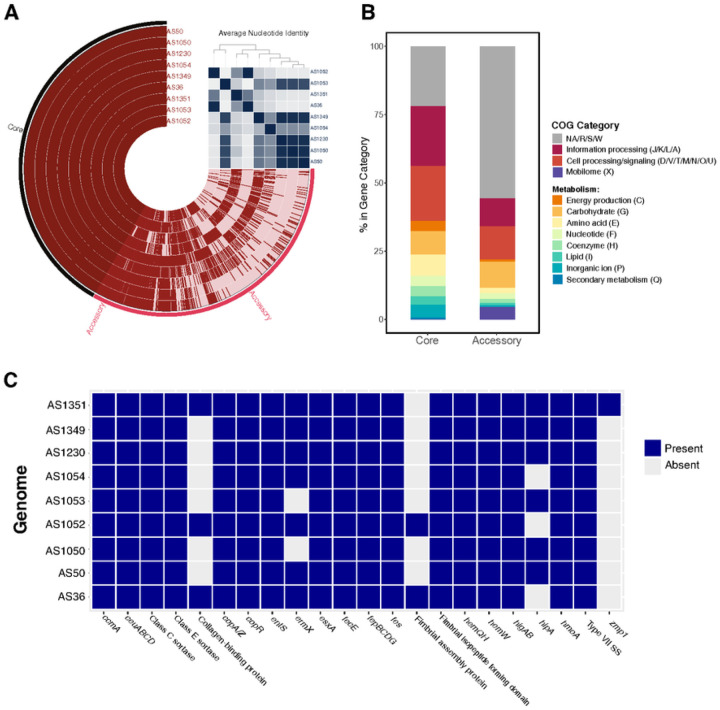

We generated high quality whole genome sequences of each A. schaalii isolate, with a mean Q30 sequencing coverage of 275x. The mean genome length was 2,325,278 bp with an average of 1931 coding sequences (CDS). Following annotation of genes with Bakta27, we computed the pangenome with Roary28. The core genome shared by all nine isolates was composed of 831 genes. An additional 2081 genes were found in 2–8 of the isolates. Finally, there were 1626 unique genes found in only 1 of the nine isolates. We visualized the pangenome and calculated average nucleotide identify (ANI) with anvi’o (Figure 4A). We compared the gene clusters in the core and accessory genomes using by annotating clusters by COG category within anvi’o. Overall, 21.9% of the core genome and 55.8% of the accessory genome were classified as general functions (R), unknown functions (S) or unassigned within the COG database (NA) (Figure 4B). The core genome was enriched for genes involved in information processing (DNA replication, transcription, etc.; COG J/K/L/A), cell processing/signaling (COG D/V/T/M/N/O/U), and energy production (COG C). Interestingly the accessory genome was enriched for genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism (COG G) Intuitively, gene clusters involved in mobile gene transfer (COG X) were elevated in the accessory genome (4.6% vs. 0.06%), consistent with the flexible nature of the accessory genome.

Figure 4. Genomic Characterization of Actinotignum schaalii Isolates.

A) Nine A. schaalii genomes isolated by EQUC from distinct subjects were subjected to whole genome sequencing. A. schaalii pangenome of the nine isolates visualized using anvi’o. Core genes were present in 100% of isolates (9/9) while the accessory genome consists of gene present in <9 of the genomes. Clustering of the genomes is based on average nucleotide identity (ANI), shown in the upper right matrix. B) Relative abundance of COG categories represented in the core and accessory genomes. C) Presence-absence matrix of fitness factors and antimicrobial resistance genes. ABRicate was used to screen contigs using the MegaRes, ResFinder, and Virulence Factor databases.

To identify potential determinants of A. schaalii fitness in the urinary tract, we used ABRicate to screen for the presence of antimicrobial resistance genes and known fitness factors, utilizing the ResFinder, MegaRes, and the VirulenceFinder Database. Notably, the Actinomycetaceae family is poorly represented in the VFDB and genomic datasets in general51, limiting the identification of putative virulence factors. We also annotated contigs with Bakta which reduces the number of CDS annotated as hypothetical proteins27. We manually curated potential fitness factors from the Bakta annotations. Seven of the nine isolates encoded ermX, an rRNA methyltransferase conferring resistance to macrolides. All nine isolates encoded the Esx-1 Type VII secretion system and its toxin esxA (Figure 4C). Esx-1 has been most extensively characterized in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a member of the phylum Actinobacteria like A. schaalii52,53. EsxA is an anti-eukaryotic membrane-permeabilizing toxin and is required for virulence in M. tuberculosis53.

Metal acquisition and homeostasis are key fitness determinants for microbial-host interactions54,55. All nine isolates contained the enterobactin transporters, entS and fepBCDG (Figure 4C). The siderophore enterobactin, an iron-chelating small molecule, is a known fitness factor within the iron-deplete urinary tract56. Analysis of A. schaalii contigs using antiSMASH32,33 to identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), particularly those responsible for siderophores production, did not reveal any putative BGCs that may produce enterobactin or related molecules (Supplementary Table 5). Systems for the acquisition and metabolism of heme were also ubiquitous in the 9 isolates. Specifically, all nine isolates encoded hemQ and hemH (coproheme decarboxylase and ferrochetalase, respectively) which are involved in heme biosynthesis, the heme chaperone hemW, the heme ATPase transporter ccmA, and the heme-degrading monooxygenase hmoA. Furthermore, all nine isolates encoded copper detoxification systems. Copper is toxic to bacteria in high concentrations and is elevated in the urinary tract during infection57,58. Thus, copper detoxification is considered a fitness factor in the urinary tract. All nine isolates encoded copA/Z, a copper exporter and chaperone respectively, and copR, a copper responsive transcriptional regulator (Figure 4C). Together, these results indicate that A. schaalii encodes known fitness factors within the phylum Actinobacteria (e.g. EsxA) and within disparately related urinary pathogens (metal acquisition and detoxification).

4. Discussion

The importance of understanding how the microbiome of a given anatomic niche shapes the biology and health of a host has never been more critical. In the genitourinary tract it is now well-accepted that a urobiome exists and plays a role in several urologic conditions3–7. Yet, compared to other anatomic niches, like the oral cavity, the gut and the skin, research surrounding the microbiome of the bladder is at its infancy. We use complementary approaches of extended culture and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to identify bacteria in catheterized urine samples from healthy infant males. With EQUC, we isolated 43 unique bacterial species and 64% of urine samples grew at least one colony by EQUC (Table 2), a percentage consistent with many prior urobiome studies1,2,8,14. These patient-derived isolates open exciting avenues for studying the interactions of urobiome members.

Our study reveals twelve genera (Staphylococcus, Nocardiopsis, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Corynebacterium, Nesterenkonia, Aliihoeflea, Saccharopolyspora, Sphingobacterium, Escherichia-Shigella, Lactobacillus, and Halomonas) that were detected by 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing in ≥48 of the 50 urine samples. This indicates a consistent urobiome composition among healthy infant males. Urobiome alpha diversity was not significantly different between infants born by vaginal vs. Caesarean section, nor was diversity affected by prior antibiotic exposure (Figure 2C).

Males younger than one-year-old have higher rates of urinary tract infection (UTI) than females59. Various explanations for this difference have been proposed, including hormone levels and lack of circumcision60,61. The abundance of the taxon Enterobacteriaceae, the predominant cause of UTIs, in our dataset (Figure 3) may offer an additional exploratory hypothesis for the higher rates of UTIs in male infants. As previously noted, none of the subjects in this study had prior UTI. Notably, in our cohort, urobiome alpha diversity was not significantly different between infants born by vaginal vs. Caesarean section, nor was diversity affected by prior antibiotic exposure (Figure 2C). This could be due to several reasons: the median age of the male subjects was 7 months old; it is possible that any differences in urobiome composition arising from different modes of delivery have not persisted over time. Another possibility is that once the urobiome is established, it is not perturbed by diet, given the limited metabolites that are excreted in the urine compared to the gut. Likewise, depending on the antibiotic class, dosage and duration of course, antibiotic concentrations in the urine may not have been sufficient to leave a lasting imprint on the urobiome.

Interestingly, amplicon sequencing did not detect the genus Porphyromonas in high abundance, nor did any samples grow Porphyromonas on EQUC (Porphyromonadaceae in Figure 3). Porphyromonas has been previously described as a major component of the male pediatric urobiome from voided urine samples12. Our analysis and another pediatric urobiome study62 did not detect Porphyromonas in catheterized samples, suggesting that Porphyromonas may originate from the urethra and not the bladder. This observation is supported by urethra-specific sampling in adult males63.

The family Nocardiopsaceae, specifically the genus Nocardiopsis, was frequently identified in our 16S rRNA data (Figure 3). The closely related genera Nocardioides has been detected in several urobiome studies38,64. Still, soil and water bacteria, like Nocardiopsis, are well described contaminants of laboratory supplies and reagents. Our methods for filtering contaminants did not remove Nocardiopsis from our subjects’ samples. This requires further attention to determine whether Nocardiopsis may be a yet unculturable member of the urobiome or an unfiltered sequencing contaminant.

As ongoing research continues to define the urinary microbiome, standardized methods and reporting are vital22. Given the low biomass of the urinary microbiome, the potential for contamination is high. We utilized rigorous sampling and processing controls to benchmark the potential contaminants introduced during sample collection and processing. Importantly, this study sets the precedent of collecting and reporting urinary catheter controls as a potential source of contamination. Following sampling of more catheter types and collection environments, the contaminant identification package SourceTracker may become useful within the urobiome field65. The analysis of urobiome amplicon sequencing data must account for the low biomass of this sample type and potential sources of contamination. Thus far, reporting of analysis parameters and filtering thresholds has been insufficient for the replication of these studies. To promote reproducibility within the urobiome field, we have included extensive methodological and bioinformatic detail herein. We hope this resource will improve the reproducibility of amplicon sequencing analysis by the urobiome field.

Finally, thus far, urobiome studies have been predominately descriptive studies. Using Actinotignum schaalii as a representative example, we show how the complementary approaches of extended culture and sequencing can uncover exploratory hypotheses by which bacteria may colonize and opportunistically infect the urinary tract. Using whole genome sequencing of nine A. schaalii genomes isolated by extended culture, we identified that A. schaalii possesses the transporters for enterobactin uptake but not the biosynthetic machinery for its production. This intriguing observation raises the questions of whether A. schaalii produces yet unidentified siderophores or whether A. schaalii may utilize siderophores produced by other urobiome constituents, known as xenosiderophore scavenging. These observations produce a testable hypothesis for the interactions of A. schaalii with other members of the urobiome community.

In summary, our study provides a snapshot of the pediatric urobiome of healthy infant males. From extended culture, we create an inventory of cultured urobiome constituents for future mechanistic studies. Finally, we report a comprehensive map of genomic features for the urobiome resident A. schaalii that appears to exhibit both commensal and uropathogenic properties in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the members of the Division of Pediatric Urology for their collegiality and support. This study was funded by Vanderbilt Trans-Institutional Programs; the Vanderbilt Institute for Infection, Immunology & Inflammation; and the NIH under awards P20DK123967 (JES, DC, and MH), T32GM007347 (SAR), F30AI169748 (SAR), F31DK131902 (GHM) and T32AI112541 (GHM). This publication includes data generated at the UC San Diego IGM Genomics Center utilizing an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 that was purchased with funding from a NIH SIG grant (#S10 OD026929).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Files

Contributor Information

Maria Hadjifrangiskou, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Seth Reasoner, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Viktor Flores, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Gerald Van Horn, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Grace Morales, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Leslie Peard, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Benjamin Abelson, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Carmila Manuel, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Jessica Lee, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Bailey Baker, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Timothy Williams, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Jonathan Schmitz, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Douglass Clayton, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All sequence data derived from this work are publicly available in NCBI-Genbank databases under Bioproject PRJNA912725. Accession numbers are listed within Supplementary Table S6. All code used for bioinformatic analysis is publicly available within the supplementary methods: https://github.com/reaset41/Infant-Urobiome.

References

- 1.Wolfe A. J. et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol 50, 1376–1383 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilt E. E. et al. Urine is not sterile: Use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol 52, 871–876 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kachroo N. et al. Meta-analysis of clinical microbiome studies in urolithiasis reveal age, stone composition, and study location as the predominant factors in urolithiasis-associated microbiome composition. mBio 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearce M. M. et al. The female urinary microbiome in urgency urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213, 347.e1–347.e11 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oresta B. et al. The Microbiome of Catheter Collected Urine in Males with Bladder Cancer According to Disease Stage. J Urol 205, 86–93 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajic P. et al. Male Bladder Microbiome Relates to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur Urol Focus 6, 376–382 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaughan M. H. et al. The Urinary Microbiome in Postmenopausal Women with Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. J Urol 206, 1222–1231 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storm D. W. et al. A Child’s urine is not sterile: A pilot study evaluating the Pediatric Urinary Microbiome. J Pediatr Urol 18, 383–392 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole E., Shaikh N. & Forster C. S. The pediatric urobiome in genitourinary conditions: a narrative review. Pediatric Nephrology vol. 37 1443–1452 Preprint at 10.1007/s00467-021-05274-7 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinneman L. et al. Assessment of the urinary microbiome in children younger than 48 months. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 565–570 (2020) doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forster C. S. et al. A cross-sectional analysis of the urine microbiome of children with neuropathic bladders. J Pediatr Urol 16, 593.e1–593.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredsgaard L. et al. Description of the voided urinary microbiota in asymptomatic prepubertal children – A pilot study. J Pediatr Urol 17, 545.e1–545.e8 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gensollen T., Iyer S. S., Kasper D. L. & Blumberg R. S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science (1979) 352, 539–544 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price T. K. et al. Bladder bacterial diversity differs in continent and incontinent women: a cross-sectional study. in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology vol. 223 729.e1–729.e10 (Mosby Inc., 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas-White K. et al. Culturing of female bladder bacteria reveals an interconnected urogenital microbiota. Nat Commun 9, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al K. F. et al. Ureteral Stent Microbiota Is Associated with Patient Comorbidities but Not Antibiotic Exposure. Cell Rep Med 1, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqui N. Y. et al. Updating Urinary Microbiome Analyses to Enhance Biologic Interpretation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyce C., Halverson T., Gonzalez C., Brubaker L. & Wolfe A. J. The Urobiomes of Adult Women With Various Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Status Differ: A Re-Analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cattoir V. Actinobaculum schaalii: Review of an emerging uropathogen. Journal of Infection 64, 260–267 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann P. et al. Actinobaculum schaalii an emerging pediatric pathogen? BMC Infect Dis 12, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horton L. E., Mehta S. R., Aganovic L. & Fierer J. Actinotignum schaalii infection: A clandestine cause of sterile pyuria? Open Forum Infect Dis 5, 10–12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brubaker L. et al. Forming Consensus To Advance Urobiome Research. mSystems 6, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson L. R. et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551, 457–463 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Callahan B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 13, 581–583 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMurdie P. J. & Holmes S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One 8, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seemann Torsten. Shovill. https://github.com/tseemann/shovill.

- 27.Schwengers O. et al. Bakta: Rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb Genom 7, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page A. J. et al. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31, 3691–3693 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eren A. M. et al. Anvi’o: An advanced analysis and visualization platformfor ‘omics data. PeerJ 2015, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eren A. M. et al. Community-led, integrated, reproducible multi-omics with anvi’o. Nature Microbiology vol. 6 3–6 Preprint at 10.1038/s41564-020-00834-3 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galperin M. Y. et al. COG database update: Focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D274–D281 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medema M. H. et al. AntiSMASH: Rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 39, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blin K. et al. AntiSMASH 6.0: Improving cluster detection and comparison capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res 49, W29–W35 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kautsar S. A. et al. MIBiG 2.0: A repository for biosynthetic gene clusters of known function. Nucleic Acids Res 48, D454–D458 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stinson L. F., Keelan J. A. & Payne M. S. Identification and removal of contaminating microbial DNA from PCR reagents: impact on low-biomass microbiome analyses. Lett Appl Microbiol 68, 2–8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenhofer R. et al. Contamination in Low Microbial Biomass Microbiome Studies: Issues and Recommendations. Trends in Microbiology vol. 27 105–117 Preprint at 10.1016/j.tim.2018.11.003 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss S. et al. Tracking down the sources of experimental contamination in microbiome studies. Genome Biol 15, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karstens L. et al. Does the urinary microbiome play a role in urgency urinary incontinence and its severity? Front Cell Infect Microbiol 6, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minich J. J. et al. KatharoSeq Enables High-Throughput Microbiome Analysis from Low-Biomass Samples. mSystems (2018) doi: 10.1128/mSystems. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez-Carrasco V., Soriano-Lerma A., Soriano M., Gutiérrez-Fernández J. & Garcia-Salcedo J. A. Urinary Microbiome: Yin and Yang of the Urinary Tract. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology vol. 11 Preprint at 10.3389/fcimb.2021.617002 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shade A. Diversity is the question, not the answer. ISME Journal vol. 11 1–6 Preprint at 10.1038/ismej.2016.118 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dominguez-Bello M. G. et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 11971–11975 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrova M. I., Lievens E., Malik S., Imholz N. & Lebeer S. Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health. Frontiers in Physiology vol. 6 Preprint at 10.3389/fphys.2015.00081 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witkin S. S. Lactic acid alleviates stress: good for female genital tract homeostasis, bad for protection against malignancy. Cell Stress Chaperones 23, 297–302 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller N. T., Bakacs E., Combellick J., Grigoryan Z. & Dominguez-Bello M. G. The infant microbiome development: Mom matters. Trends in Molecular Medicine vol. 21 109–117 Preprint at 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.002 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis D. A. et al. The human urinary microbiome; bacterial DNA in voided urine of asymptomatic adults. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lotte R., Lotte L. & Ruimy R. Actinotignum schaalii (formerly Actinobaculum schaalii): A newly recognized pathogen-review of the literature. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 22, 28–36 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuuminen T., Suomala P. & Harju I. Actinobaculum schaalii: Identification with MALDI-TOF. New Microbes New Infect 2, 38–41 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevens R. P. & Taylor P. C. Actinotignum (formerly Actinobaculum) schaalii: a review of MALDI-TOF for identification of clinical isolates, and a proposed method for presumptive phenotypic identification. Pathology 48, 367–371 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yassin A. F. et al. Draft genome sequence of Actinotignum schaalii DSM 15541T: Genetic insights into the lifestyle, cell fitness and virulence. PLoS One 12, 1–27 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seshadri R. et al. Expanding the genomic encyclopedia of Actinobacteria with 824 isolate reference genomes. Cell Genomics 100213 (2022) doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdallah Abdallah M., G. van P. N. C. D. C. P. A. C. J. L. J. V.-G. C. M. J. E. A. B. J. and B. W. Type VII secretion — mycobacteria show the way. Nat Rev Microbiol (2007) doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rivera-Calzada A., Famelis N., Llorca O. & Geibel S. Type VII secretion systems: structure, functions and transport models. Nature Reviews Microbiology vol. 19 567–584 Preprint at 10.1038/s41579-021-00560-5 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murdoch C. C. & Skaar E. P. Nutritional immunity: the battle for nutrient metals at the host–pathogen interface. Nat Rev Microbiol 20, 657–670 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerner R. R., Nuccio S. P. & Raffatellu M. Iron at the host-microbe interface. Molecular Aspects of Medicine vol. 75 Preprint at 10.1016/j.mam.2020.100895 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson A. E., Heffernan J. R. & Henderson J. P. The iron hand of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: The role of transition metal control in virulence. Future Microbiol 13, 813–829 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hyre A. N., Kavanagh K., Kock N. D., Donati G. L. & Subashchandrabose S. Copper is a host effector mobilized to urine during urinary tract infection to impair bacterial colonization. Infect Immun 85, 1–14 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Subashchandrabose S. & Mobley H. L. T. Back to the metal age: battle for metals at the host-pathogen interface during urinary tract infection. Metallomics 7, 935–942 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larcombe J. Urinary tract infection in children: recurrent infections. BMJ Clin Evid 2015, 1–9 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albracht C. D., Hreha T. N. & Hunstad D. A. Sex effects in pyelonephritis. Pediatric Nephrology 36, 507–515 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh-Grewal D., Macdessi J. & Craig J. Circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: A systematic review of randomised trials and observational studies. Archives of Disease in Childhood vol. 90 853–858 Preprint at 10.1136/adc.2004.049353 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kassiri B. et al. A Prospective Study of the Urinary and Gastrointestinal Microbiome in Prepubertal Males. Urology 131, 204–210 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hrbacek J., Morais D., Cermak P., Hanacek V. & Zachoval R. Alpha-diversity and microbial community structure of the male urinary microbiota depend on urine sampling method. Sci Rep 11, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng J. et al. Alterations in Urobiome in Patients With Bladder Cancer and Implications for Clinical Outcome: A Single-Institution Study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Knights D. et al. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking. Nat Methods 8, 761–765 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All sequence data derived from this work are publicly available in NCBI-Genbank databases under Bioproject PRJNA912725. Accession numbers are listed within Supplementary Table S6. All code used for bioinformatic analysis is publicly available within the supplementary methods: https://github.com/reaset41/Infant-Urobiome.