Abstract

Enzymatic processes, particularly those capable of performing redox reactions, have recently been of growing research interest. Substrate specificity, optimal activity at mild temperatures, high selectivity, and yield are among the desirable characteristics of these oxidoreductase catalyzed reactions. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) or NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases have been extensively studied for their potential applications like biosynthesis of chiral organic compounds, construction of biosensors, and pollutant degradation. One of the main challenges associated with making these processes commercially viable is the regeneration of the expensive cofactors required by the enzymes. Numerous efforts have pursued enzymatic regeneration of NAD(P)H by coupling a substrate reduction with a complementary enzyme catalyzed oxidation of a co-substrate. While offering excellent selectivity and high total turnover numbers, such processes involve complicated downstream product separation of a primary product from the coproducts and impurities. Alternative methods comprising chemical, electrochemical, and photochemical regeneration have been developed with the goal of enhanced efficiency and operational simplicity compared to enzymatic regeneration. Despite the goal, however, the literature rarely offers a meaningful comparison of the total turnover numbers for various regeneration methodologies. This comprehensive Review systematically discusses various methods of NAD(P)H cofactor regeneration and quantitatively compares performance across the numerous methods. Further, fundamental barriers to enhanced cofactor regeneration in the various methods are identified, and future opportunities are highlighted for improving the efficiency and sustainability of commercially viable oxidoreductase processes for practical implementation.

Keywords: biocatalysis, cofactor regeneration, electrocatalysis, oxidoreductases, photocatalysis

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

A variety of enzymes produced by microorganisms has been gaining attention of researchers for extra-cellular production of various chemicals, including beverages, food additives, pharmaceutical products, and biofuels.[1] Enzymes may be beneficial over chemocatalysts owing to their ability of sustainable synthesis, high selectivity, substrate specificity, optimal activity at mild conditions, and high yield.[2] Enzymatic reactions have been studied for their extensive application in biomass conversion to commodity chemicals ranging from fuel hydrocarbons to aliphatic and aromatic alcohols, ketones, and carboxylic acids, as well as for production of chiral compounds.[3,4] Advances in molecular biology to produce more efficient recombinant enzymes and improvements in biocatalyst recovery and reuse by techniques like immobilization have further facilitated enzymes to become even more competitive to chemocatalysts.[5] Among all known enzymes, oxidoreductases constitute one quarter of all enzymes.[6] Although certain oxidoreductases possess prosthetic groups to facilitate redox reactions,[7] most of them are generally dependent on nonprotein cofactors like nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) [NAD(P)H] (Figure 1) to catalyze the transfer of electrons from an electron donor (reductant) to an electron acceptor (oxidant) molecule.[8] The cofactor thus works as an electron donor/acceptor in the redox reaction catalyzed by the enzyme while being exhausted in stoichiometric quantity. The exogenous addition of stoichiometric nicotinamide cofactors is commercially infeasible due to high costs,[9] hence continuous regeneration of the cofactor is required. To address this concern, precursor fermentation uses whole-cell biocatalysts to produce and regenerate cofactors for example, which are useful for one-pot enzymatic cascade systems.[10,11] Significant challenges are associated with whole-cell biocatalysis as it is difficult to control the amount of the different proteins produced by the organism, resulting in a mixture of byproducts, which leads to complicated downstream separation. In addition, metabolic demands of the organism might also reduce the overall efficiency of the biocatalytic process. In cell-free biocatalysis involving oxidoreductases, NAD(P)H regeneration is imperative for these processes to be commercially viable.

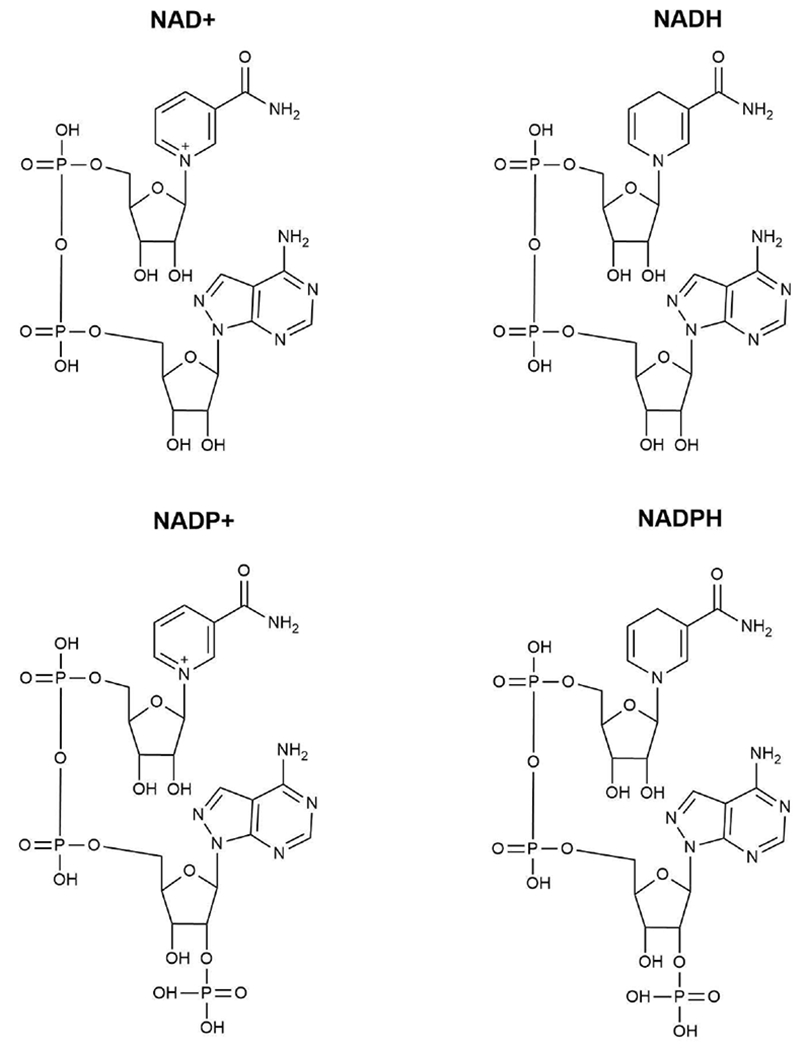

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide cofactors (non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated).

A quantitative measure of the cofactor regeneration can be estimated using the total turnover number (TTN), defined by Chenault et al. as the total number of moles of product formed per mole of cofactor during a complete reaction.[12] However, in several articles, the distinction between turnover number (TN) and TTN is ambiguous. For this Review, we have defined TN as the moles of product formed per mole of cofactor (TNcofactor) or per mole of enzyme (TNenzyme) or per mole of catalyst in general (TNcatalyst) used during a complete reaction.[12] Among all known regeneration methods, enzymatic regenerations have been reported to achieve the highest TNcofactor of >500000.[13] Enzymatic regenerations require coupled redox processes, in which a desired substrate oxidation is accompanied by a cosubstrate reduction. The NAD(P)+, thus, cycles between its reduced and oxidized forms, reducing the overall cost of using the cofactor.

In addition to enzymatic cofactor regeneration methods, other approaches can provide the required regeneration, including chemical, electrochemical, and photochemical regeneration, as shown in Figure 2. Chemical regeneration methods are somewhat similar to the enzymatic regeneration approach as the in-situ regeneration or direct electron transfer using hydride sources enables the cofactor to be used in catalytic amounts. Hydride acceptors such as pyridinium and flavin derivatives have been used in one of the earlier studies for regeneration of NAD+ ;[14] however, they were required in excess amount compared to the catalytic concentration of the oxidized cofactor. Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl rhodiumIII bipyridyl [Cp*Rh(bpy)] complexes have been efficiently used for formate-dependent NAD+ reduction[15] as well as pH-dependent reversible hydride exchange, which can facilitate regeneration of both reduced and oxidized cofactors.[16] Heterogeneous catalysts like platinum on alumina,[17] and pyrolytic graphite modified with a hydrogenase and a diaphorase subunit[18] have also been demonstrated to regenerate NADH using hydrogen as the hydride source.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of different NAD(P)H regeneration strategies.

Electrochemical NAD(P)H regeneration uses electrons transferred between electrodes. This is an attractive method of regeneration as redox reactions and the corresponding cosubstrates or coproducts can be compartmentalized, simplifying downstream separation. Several research works in this area can be traced back to 1980s,[19–22] where authors regenerated the cofactors sometimes directly or via an electron-mediator like [Cp*Rh(bpy)(H2O)]2+.[23] Electrochemical regeneration mechanisms have been used extensively in biofuel cells and biosensors applications.[24,25]

Photochemical regeneration has also been used by exploiting light harvesting capability of artificial, biomimetic photosensitizers like cadmium sulfide (CdS) and titania (TiO2)[26–29] for the regeneration of NADH.[30] The small bandgap between the valence and conduction bands of these materials facilitates the excitation of electrons, which are then utilized in the electron transfer mechanism, responsible for the cofactor regeneration. However, the positive holes generated on the photosensitizer are required to be filled, which is commonly done by using a sacrificial donor like triethanolamine.[31,32]

A brief comparison of the different NAD(P)+ and NAD(P)H regeneration strategies (enzymatic, chemical, electrochemical, and photochemical) are listed in Table 1. Considering the large number of research articles published over the last two decades, multiple Reviews have also been published covering multienzymatic systems,[7,33,34] heterogeneous pathways-inspired regeneration,[9] organometallics-based approach for NAD(P)H regeneration,[35] and cofactor regeneration in oxidative biocatalytic processes,[36] but no comprehensive Review has appeared in nearly a decade, despite significant developments. Additionally, no Review has presented a uniform analysis comparing the productivity of various methods of regeneration. In this comprehensive Review, it is our goal to discuss and comment on different methods for nicotinamide cofactor regeneration and provide a quantitative comparison to highlight the effectiveness and utility of the tools or methodology used in these different modes of regeneration. TN based on cofactor and/or catalyst have been used to compare different strategies in enzymatic, chemical, electrochemical, and photochemical regeneration. For electrochemical regeneration methods, electrode potentials have also been used as a measure of comparison where TNs were not reported or could not be calculated. Most of the discussion comprises peer reviewed publications from the last decade; however, results from important studies published earlier have also been included based on their relevance to the context.

Table 1.

Comparison of the different cofactor regeneration strategies.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| enzymatic | low impact on environment; high total turnover numbers; 100% selectivity; high enantioselectivity | enzyme denaturation; high cost of purified enzymes |

| chemical | moderate cost; hydrogen and oxygen could be used for reduced and oxidized cofactor regeneration, respectively | requires sacrificial donor; difficult downstream separation; mutual inactivation when used in enzymatic cascades; low total turnover numbers |

| electrochemical | renewable electricity sources can be used; enzymes can be immobilized on electrode surface; less complex downstream separtion; wide range of applications | low total turnover numbers; transition metal-based electron mediators required to enhance rate of regeneration and avoid inactive NAD2 dimer formation; high overpotentials required |

| photochemical | use of renewable energy (solar) for photoexcitation; broad applications | requires sacrificial donor; low total turnover numbers; requires transition metal-based electron mediators; quantum efficiency is low |

2. Enzymatic Regeneration

2.1. Types of enzymatic regeneration methods

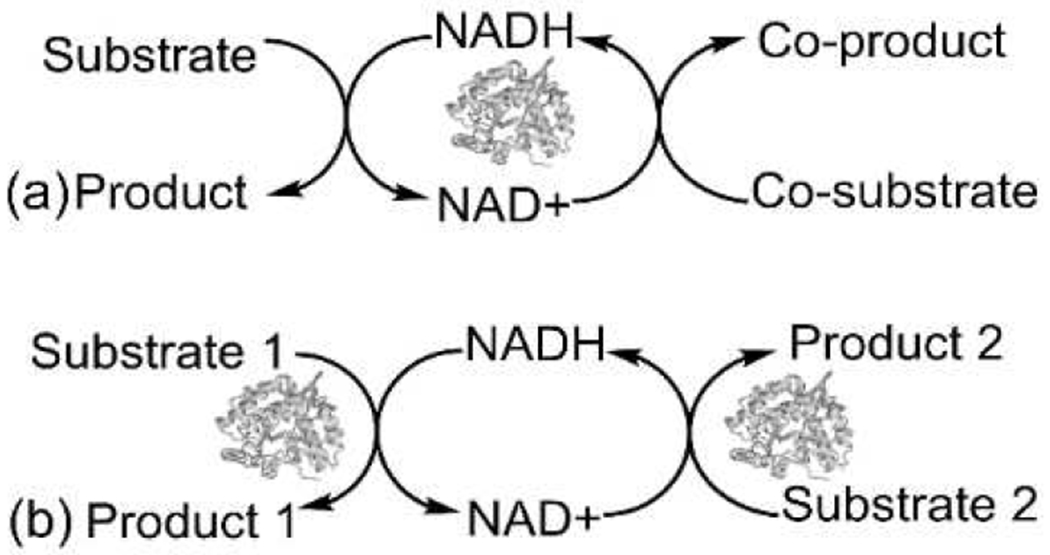

Due to the growing emphasis on sustainable large-scale production of chemicals and pharmaceuticals, enzymatic processes, particularly those associated with redox enzymes, have gained traction over the years as reflected in several recent Review articles.[37–40] For NAD(P)-coupled redox enzymes, cofactor regeneration is essential for practical implementation. Two modes of enzymatic regeneration are (i) substrate-coupled and (ii) enzyme-coupled reactions. In a substrate-coupled reaction,[41] the same enzyme simultaneously oxidizes one substrate and reduces another to produce a product and coproduct (Figure 3a). The cofactor is regenerated toggling to and from its reduced to oxidized form. Alternatively, an enzyme-coupled reaction requires a separate regenerating enzyme (Figure 3b).[42] Multi-enzymatic cascade reactions use two or more enzymes with different substrates to facilitate cofactor regeneration and are classified into four types: (i) linear, (ii) orthogonal, (iii) parallel, and (iv) cyclic.[43] The orthogonal or parallel cascades are applicable for NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenase enzymes like the family of alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs) to catalyze commercially important reactions like the production of enantiopure alcohols by stereoselective reduction of prochiral ketones.[44] Reduced nicotinamide cofactors are required in important organic syntheses like Bayer–Villiger oxidations (a parallel cascade) and dynamic kinetic resolution reactions (a cyclic cascade).[45] In the latter case, cofactor regeneration has been demonstrated in one-pot coupled enzymatic synthesis by parallel oxidation of racemic alcohols and reduction of the corresponding ketone to produce enantiopure secondary alcohols,[46,47] as a possible alternative to chemocatalytic dynamic kinetic resolution reactions.[48]

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of cofactor regeneration using (a) substrate-coupled and (b) enzyme-coupled cascade reaction.

The importance of cofactor regeneration for applications in the syntheses of chiral drugs is readily apparent. Indeed, extracts from Rhodococcus ruber DSM 44541, which displayed different enantioselectivity for oxidation and reduction steps, were used by Voss et al. to demonstrate deracemization of pharmaceutically relevant secondary alcohols.[49] The system under investigation was a one-pot/two-step sequence and the enzymatic cofactor recycling system was switched back and forth between oxidation and reduction to achieve 100% pure enantiomers. Such strategies enable a continuous biotransformation process but also enhance the turnover number of both the enzyme and the cofactor several fold and make these processes more appealing towards industrial applications.

Another important reason for such enzymatic reactions gaining attraction is their capability of CO2 conversion to valuable chemicals or fuels like formate and methanol among others, in environmentally beneficial systems.[50–52] In one case, methanol yields as high as 95% were obtained from CO2 in a three-enzyme cascade.[53] One of the earliest enzymatic regenerations leveraging formate/CO2 interconversion with formate dehydrogenase (FDH) from Candida boidinii as the regenerating enzyme was demonstrated by Shaked and Whitesides[54] in the production of d-lactate from pyruvate. FDH has since become a common choice for a regenerating enzyme of either NAD+ or NADH. Partially entrapping these cofactors using nanofiltration membrane reactors can be of additional advantage as the soluble cofactors are retained within the reactor, which facilitates the design of a continuous reactor using similar coupled 2-enzyme regeneration approach.[55] Numerous NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenases have been utilized with in situ cofactor regeneration. Despite several advantages, challenges remain in these systems related to enzyme and cofactor retention and reuse, high cost, and difficult downstream separation.

2.2. Cofactor regeneration in whole-cell biocatalytic systems

Whole-cell biocatalysis with co-expression of two enzymes like leucine dehydrogenase (LeuDH) and FDH has been demonstrated to work in an NADH recycling cascade for the production of enantiopure drug precursors.[56] Further improvement of such two-enzyme cascades can be found in the work done by Jiang and Fang, who regulated the co-expression of individual enzymes by regulating the strength of ribosome binding sites to equilibrate the enzyme activities and achieve high yield of the product of interest.[57] However, the ratio of the NADH-dependent dehydrogenase enzymes is crucial in deciding the final product concentration in such cofactor regenerating cascade systems. For example, Qi et al. discovered that in a LeuDH/FDH-catalyzed enzyme-coupled cascade reaction for the production of l-norvaline, non-competitive inhibition by NADH at high concentration led to low equilibrium product concentration.[58] The authors maintained that optimizing the enzyme concentration ratio was important to maintain high productivity. Additionally, they also demonstrated a fed-batch reactor, which further enhanced the productivity of the cascade process, limiting the inhibition associated with high concentration of the d isomer. Some whole-cell biocatalytic processes have additional advantage as the cofactor is produced and recycled in vivo.[59] For instance, the drug precursor molecule (4R,6R)-actinol can be produced by enantioselective reduction of ketoisophorone by the action of two enzymes (alcohol dehydrogenase and enoate reductase), both of which are produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Uzir and Najimudin demonstrated this important reaction by using whole-cell biotransformation using baker’s yeast where they maintained that the in-vivo produced cofactor was recycled within the cells by simultaneous oxidation of some arbitrary compound (Figure 4).[59] However, in other whole-cell biocatalysis systems with co-display of two enzymes, exogenous cofactor addition might be necessary, and in-vivo regeneration is not an option in such a case. Han et al. worked with such a system where glucoamylase (GA) and glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) were co-displayed on engineered bacterial surfaces for the production of glucono-δ-lactone using starch as the substrate.[60] They solved the issue of NAD+ regeneration by introducing a third enzyme, l-lactate dehydrogenase, which simultaneously reduced pyruvate to l-lactic acid. Similar tools like co-encapsulation and co-immobilization of redox enzymes, particularly those which are used for oxidation of alcohols, are frequently employed for efficient regeneration strategies.[38,61–65]

Figure 4.

Production of (4R,6R)-actinol from ketoisophorone using combination of two enzymes with cofactor recycling. ER = enoate reductase; ADH = alcohol dehydrogenase; Xred and Xox represent arbitrary species undergoing oxidation and reduction, respectively.

2.3. Cofactor regeneration in cell-free biocatalytic systems

2.3.1. Single enzyme cascade regeneration

Redox enzymes with a wide range of substrate specificity like that of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) can regenerate the NAD(P)H cofactors by suitable coupling of substrates. Prediction of thermodynamic equilibria is particularly important to understand the feasibility of a redox reaction to proceed spontaneously.[66] For example, Jadhav et al. used a substrate-coupled strategy for the production of n-butanol from n-butyraldehyde with around 74% substrate conversion using ethanol as the cofactor regenerating substrate with a TNcofactor of 507.[41] Using single enzyme cascades for NAD(P)H regeneration by coupling suitable substrates is economically advantageous as it does not necessitate a second biocatalyst. Several ADHs, known for their catalytic promiscuity, like ADH2 from Haloferax volcanii[67] and ADH from Lactobacillus brevis,[68] have been used for enantioselective reduction of ketones with suitable co-substrates like ethanol or isopropanol. A wide range of substrate specificity enables these enzymes to carry out redox reactions without having to use a second enzyme for the cofactor regeneration, and the enantiopure products are typically expensive, which may be worth producing even at relatively low cofactor turnover numbers. Some other enzymes like glucose dehydrogenase do not generally accept substrates other than glucose, which necessitates the use of a second enzyme for the cofactor regeneration. However, in a recent impressive work, Yan et al. developed a rational design using saturation mutagenesis to create a mutant GDH enzyme with enhanced substrate specificity[69] and utilized this enzyme for the production of enantiopure (R)-2-chromandelic acid methyl ester, an important drug precursor with glucose as the co-substrate for NAD(P)H regeneration. However, not all alcohol dehydrogenases/ketoreductases can be used in single enzyme cascades for in-situ cofactor regeneration. In the case of organic retrosynthesis, where multiple substrates are required to be combined to produce a target molecule, it becomes necessary to develop multi-enzyme cascades, with cofactor regeneration as an important component of the holistic retrosynthetic strategy.[70,71]

2.3.2. Multienzymatic cascade regeneration

2.3.2.1. Multienzymatic cascade using formate dehydrogenase

Regeneration of NAD(P)H cofactors in cell-free biocatalysis, which is extremely important for the economic feasibility of cofactor-dependent redox enzyme-catalyzed processes, had been in use as early as 1980s, as reported by Kula and Wandrey,[72] who went a step further to modify these cofactors to demonstrate their efficient use in a continuous reactor for the production of l-leucine. Formate dehydrogenase from Candida boidinii has been a very popular choice as the regenerating enzyme for cofactor regeneration purpose along with other NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases.[73–76] The interconversion of formate and CO2, both of which are benign materials, as well as the ease of downstream separation and compatibility of formate dehydrogenase to be coupled with other enzymes have driven this choice.[43,77] In fact, formate has been described as “a mediator between physicochemical and biological realms” by Yishai et al. in their Review, where they discussed several methods of formate production and use.[78] Coupling of enzymes in a multi-enzymatic cascade depends on multiple factors, like the optimum pH for individual enzymes, optimum temperature, and substrate or product inhibition effects. In certain studies, redox enzyme cascades were used for the sequential oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes to carboxylicacids, but cofactor regeneration was done electrochemically in alcohol-based biofuel cells.[79,80] Typically, in an enzymatic cofactor regeneration process, simultaneous oxidation and reduction of two substrates take place through transfer of electrons and H+ ions via intermediate enzyme-cofactor complexes. The stability of the regenerating enzyme is therefore of high importance as it is a cost-limiting factor in such processes.[81] Other factors like kinetics of enzyme-cofactor interaction as well as the kinetics of enzyme-cofactor complex interaction with the substrate might also affect the overall rate of a closed loop cascade reaction.[82] For instance, Wichmann et al. reported that NADH strongly inhibited FDH in an FDH/LEUDH (leucine dehydrogenase)-coupled cascade reaction. To achieve maximum substrate conversion, FDH required a higher fraction of total activity (55%) to overcome this inhibition.[83]

2.3.2.2. Multienzymatic cascade using other redox enzymes

While formate dehydrogenase is a common choice for enzyme-mediated cofactor regeneration, primarily due to the chemically benign nature of its substrate and product, other redox enzymes like glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), xylose dehydrogenase (XDH), NAD(P)H oxidase, and phosphite dehydrogenase (PDH) are some of the many NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases that have been used for in-situ cofactor regeneration using one-pot cascade syntheses.[84–87] Enzymatic cofactor regeneration using one-pot cascade reactions allows multistep reactions without needing to isolate or purify intermediates, thus decreasing the energy and solvent requirements for intermediate separation processes, leading to higher economic feasibility.[88] So far, the highest TNcofactor among multienzymatic regeneration systems was achieved in the work reported by Angelastro et al., where the authors demonstrated NADP+ regeneration leveraging the chemistry of glutathione reductase (GR) combined with glutaredoxin (GRX).[13] In this novel strategy, NADP+ was regenerated from NADPH by GR with simultaneous reduction of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) to glutathione (GSH), which was complimented by GRX-catalyzed reduction of disulfide compounds like 2-hydroxyethyl disulfide (HED) or cystine. This regeneration strategy was used in the synthesis of 6-phosphogluconate from glucose-6-phosphate catalyzed by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, with a cofactor turnover number (TNcofactor) of 500000 (Figure 5). While offering astounding enzyme performance, the products are of somewhat limited commercial value. In a more recent study by Jia et al., NADP+ regeneration catalyzed by myoglobin was used for complimenting glucose dehydrogenase-catalyzed oxidation of d-glucose to gluconic acid.[89] Compared to the aforementioned study, while the TNcofactor was ten times lower (≈50000), the product is of greater commercial value, while also being able to regenerate the synthetic biomimetic cofactor 1-benzyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3-carboxamide (BNA+) with higher catalytic efficiency compared to NADP+ and NAD+. Another noteworthy implementation of multienzyme one-pot cascade can be found in the work by Mutti et al., in which the authors set up a hydrogenborrowing cascade for the synthesis of chiral amines from alcohols.[90] The cascade method, which constituted an alcohol dehydrogenase and an amine dehydrogenase, demonstrated the ability to convert chiral secondary alcohols to amines with optical inversion, amination by retaining optical configuration of enantiomeric secondary alcohols, enantioselective conversion of racemic secondary alcohols to amines, and amination of primary alcohols.

Figure 5.

Glutathione reductase/glutaredoxin-based NADP + regeneration strategy for the conversion of glucose to 6-phosphogluconate using hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.[13]

Although enzymatic synthesis is an efficient route for producing fine chemicals, the requirement of cofactor regeneration in NAD(P)H-dependent enzymes makes it difficult to use them for industrial purposes. For instance, an expensive and rare sugar, d-ribulose, which is also a useful precursor in asymmetric synthesis, can be produced by Enterobacter aerogenes ribitol dehydrogenase (EaRDH) using ribitol as the substrate.[91] Singh et al. used EaRDH in an enzyme coupled cascade with lipoamide dehydrogenase as the regenerating enzyme to produce d-ribulose with extremely efficient in-situ NAD regeneration.[92] The regeneration system, according to the authors, enabled them to increase d-ribulose yield from 0.6 to around 87%. In this case the oxidized cofactor was regenerated by simultaneous reduction of the dye 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenon catalyzed by lipoamide dehydrogenase. Another such example is the recent study by Su et al., whose objective was to produce l-tagatose from d-galactitol using galactitol dehydrogenase.[93] An efficient cofactor regeneration scheme using NADH oxidase as the regenerating enzyme enabled the authors to achieve high productivity using 3mm cofactor per 100 mm of substrate. Asymmetric transformations could benefit immensely from this kind of enzyme-catalyzed cascade reactions, using the right choice of regenerating enzyme with similar initial rate of substrate conversion using innocuous substrates that can also facilitate downstream separation. For example, tetrahydrofuran-3-one and tetrahydrothiofuran-3-one are extremely difficult to reduce to corresponding alcohols in enantiomeric excess, even with thermostable alcohol dehydrogenases.[94] These chiral alcohols are valuable in drug synthesis and can be produced by engineered thermostable alcohol dehydrogenase, as was done by Sun et al., who used triple-code saturation mutagenesis approach, a directed evolution, to modify the binding site of Thermoethanolicus brockii ADH to achieve the enantioselective reduction of such “difficult-to-reduce ketones”.[95] Although the authors’ intention was not to establish a NAD(P)H regenerating enzymatic cascade, but for enzymes with capabilities of catalyzing the production of such important drug precursors, it is needless to say that coupling with a suitable enzymatic cofactor regeneration system adds immense value to industrial application of these enzymes.

2.4. Enzymatic regeneration using immobilized enzyme/cofactors

Multienzymatic cascades are becoming increasingly popular as they provide access to several specialty chemicals under benign conditions of operation and especially because these cofactor regeneration schemes enable redox enzymes to a greater extent by extenuating the requirement of these expensive cofactors. Multienzyme cascade systems with cofactor regeneration are more advantageous with immobilized enzyme than free enzymes owing to higher enzyme stability, reusability, and ability to be used in continuous-flow biocatalysis. For example, in the study by Velasco-Lozano et al., co-immobilization of l-alanine dehydrogenase and FDH from Candida boidinii was done using polyethyleneimine as an anchoring layer to irreversibly immobilize the enzymes on agarose beads modified with aldehyde moieties.[65] There was progressive decrease in residual enzyme activity in each consecutive cycle, but the system retained 80% activity after 5 cycles. However, the turnover number was reported as 150 and the authors also cited diffusion resistance for the cofactors as a technical challenge. Another example worth mentioning is a study involving an expensive aromatic ester, cinnamyl cinnamate, which is extensively used in fragrance and flavoring applications and can be produced from condensation of cinnamic acid and cinnamyl alcohol catalyzed by lipase. By employing ADH in a cofactor regeneration cascade system with FDH as the regenerating enzyme, naturally occurring cinnamaldehyde was reduced to cinnamyl alcohol with an overall yield of about 54%.[64] To enhance the cofactor turnover number, researchers have also been able to tether or anchor the NAD cofactors alongside enzymes. Chen et al. featured a zeolitic imidazole framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanoreactor for co-encapsulation of ADH and LDH to demonstrate a self-sufficient cofactor recycling cascade system (Figure 6).[61] In addition to co-encapsulation of the redox enzymes, another major issue addressed by their work was encapsulation of the cofactor NAD+ by covalently tethering it to a phenylboronic acid conjugated poly(allylamine) polymer. This phenomenal study was able to demonstrate a roughly 5-fold increase in the rate of pyruvate reduction with the mentioned enzymatic cascade system compared to the homogeneous enzyme-cofactor assembly. Similar work by Hartley et al. used polyethylene glycol to modify NADH and used it in a modular cascade system leading to a cofactor turnover number > 10000.[96]

Figure 6.

NAD+-mediated two-enzyme biocatalytic cascade in ZIF-8 NMOF nanoreactor.[61] NMOF refers to ZIF-8 nano metal–organic framework; AlcDH = alcohol dehydrogenase, LacDH = lactate dehydrogenase. The red dots represent conjugated polymer-bound NAD+.

Advanced techniques like closed-loop cofactor regeneration strategy are possible, as demonstrated in a recent study by Baulmer et al., who used a substrate-coupled approach for NADH regeneration by setting up a modular system using an immobilized HaloTagged ADH from Lactobacillus brevis.[97] The authors demonstrated conversion of several prochiral ketones to corresponding alcohols with >99% enantioselectivity and turnover numbers up to 2023 molmol−1. The most noticeable innovation in this study was the use of a flow liquid–liquid extraction (FLLEX) system, which separated and recycled the cofactors back into the feed stream of this continuous reactor system.

From the discussion on enzymatic cofactor regeneration schemes, based on the references provided in this section, it can be noticed that the observed turnover numbers for the cofactor can vary to a great extent (Table 2). Using an immobilized enzyme or cofactor is one of the important strategies that may enhance the cofactor turnover number by several folds. The observed turnover numbers depend heavily on the design of the experiments and the reported values may be considered lower limits of the potential of any given system. For example, reports vary with respect to the number of cycles of batch reactions attempted and concentrations utilized. Additionally, it is not uniformly clear in reported studies if the enzymes or cofactors degrade chemically. Enzymatic cofactor regeneration strategies are clearly useful because of their simplicity in operation and the ability to bring in redox bioconversions of substrates that are otherwise extremely difficult. As enzyme stability in continuous operation is one of the major challenges, future research should be targeted towards addressing this issue, which can enhance the turnover numbers further and achieve greater industrial relevance.

Table 2.

Comparison of turnover numbers as observed in different studies using enzymatic regeneration methods.

| Enzyme | Substrate | TN [cofactor] | TN [enzyme] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADH | ammonia/ammonium | 5[b] | 236[b] | [90] |

| myoglobin | oxygen | 50000[a] | – | [89] |

| glutathione reductase/glutaredoxin | 2-hydroxyethyl disulfide | 500000[a] | – | [13] |

| FDH | formate | 6300[b] | – | [57] |

| XDH | xylose | 160[a] | 3500[b] | [85] |

| mutant phosphite dehydrogenase | sodium phosphite | 2630[a] | 90000[b] | [87] |

| diaphorase | 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | 174[b] | – | [92] |

| NADH oxidase | oxygen | 33[b] | 26000[b] | [93] |

| LbADH | 2-propanol | 12855[a] | – | [97] |

| GA-GDH | starch | 120[b] | – | [60] |

| NOx | oxygen | 11000[a] | 1843[a] | [96] |

| LbADH | (S)-5-nitrononane-2,8-dione | 14000[a] | – | [98] |

| ADH | ethanol | 507[b] | 30000[b] | [41] |

| ADH | ethanol | 370[b] | 12000[b] | [61] |

| FDH | formate | 112[b] | 37000[b] | [62] |

Used directly from reference.

Calculated from data provided in reference.

NOx = NADH oxidase, LbADH = Lactobacillus brevis alcohol dehydrogenase.

3. Chemical Regeneration Methods

Although enzymatic regeneration of cofactor has proven to be the most efficient technique based on turnover number,[99] complexities arise due to the requirement of additional substrate(s) and in some cases additional enzyme(s). For NAD-dependent enzymatic reactions focused on a single substrate, alternate methods of cofactor regeneration have been explored. Chemical regeneration primarily based on transition metal complexes like [Cp*Rh(bpy)]2+ (Figure 7) has long been employed in this regard to avoid addition of the expensive nicotinamide cofactors in stochiometric amounts.[9,17,100–102]

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of chemical regeneration of NADH.

3.1. Methods involving organometallic complexes in NAD(P)H regeneration

In the early 1980s, rhodium-based organometallic complexes gained huge attention owing to their excellent capability to function as electron relays in reduction of proton to hydrogen.[103] To exploit the redox property of such organometallic complexes, Steckhan and coworkers explored a pentamethyl bipyridyl rhodium(III) complex for direct chemical reduction of NAD+ using formate as the hydride source.[104] The intermediate rhodium-hydride complex was identified using 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy using 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine as the ligand. Several challenges were identified associated with this mode of NADH regeneration, like degradation of NADH in tris buffer, replacement of the aquo ligand by hydroxo ligand at higher pH, and action of ammonia as a ligand in higher pH when ammonium formate was used as the hydride source. Some of these studies, which investigate the chemical mode of cofactor regeneration, have been done using NAD analogue molecules. For example, benzyl nicotina-midium (BNA+), an analogue of NAD+, was used as a model reductant in a study of enantioselective reduction of ketone catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase, which was subsequently demonstrated with NADH using ruthenium and rhodium complexes.[105] In-situ NADH regeneration was achieved under appropriate reaction conditions using [RuCl2(TPPTS)2]2 [TPPTS = tris(m-sulfonatophenyl)phosphine] and [Cp*(bpy)Rh(H2O)]Cl2 complexes and hydrogen (Figure 8). The simplicity of this process lies in the elimination of unwanted by-products as gaseous hydrogen acts as both the hydride and proton source for the enantioselective enzymatic reduction of ketones. Matsuo and Mayer characterized the mechanism of cofactor regeneration using these NADH analogues with cis-[RuIV(bpy)2(py)(O)]2+ as the catalyst for oxidation and found that the hydrogen atom transfer is rather the preferred kinetic mechanism than hydride transfer.[106]

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of Ru complex-based cofactor recycling with in-situ coupling with a reductase enzyme.

3.1.1. Mechanism of NAD+ reduction and regioselective nature of hydride transfer

One of the complexities in regenerating the reduced NAD(P)H cofactor lies in the regioselective reduction of the 1,4-pyridinium ring.[107] Reduction of NAD+ to NADH by transition metal complexes may give the preferred 1,4-addition product or the 1,6-addition product, which is not catalytically active. In an effort to unravel the mechanism of this regioselective reduction, Fish and co-workers used various pyridinium models of NAD+, with a variety of 3-substituents to investigate binding, steric, and electronic effects in their regioselective reductions conducted in 1:1 H2O/THF.[107] It was revealed that in presence of formate as the hydride donor, the aquo complex reacts with the formate, which further decomposes in a β-elimination process to produce CO2. The regioselective transfer of the hydride is facilitated by the amide functionality of the NAD+ and eventual replacement of the aqua complex occurs by displacement of the reduced 1,4-NADH from the coordination entity. To shed further light on the mechanism of hydride transfer, Miller and co-workers[108] isolated an intermediate pentamethylcyclopentadiene Rh complex, from fleeting rhodium hydride and studied the hydride transfer ability of the diene, including reduction of NAD+. The involvement of the pentamethylcyclopentadienyl ligand in hydride transfer was a novel finding for these Rh-complex mediated regenerations, and the proposed mechanism (Figure 9) was consistent with density functional theory (DFT) calculation results for several closely related Rh and Ir complexes. Based on studies on several RhIII and RuII complexes and comparing the corresponding turnover frequencies (TOF), it is now known that ligands in the coordination sphere have significant effect on the activity of the complexes,[109] and in general, RhIII complexes were found to be much more efficient than RuII complexes based on the TOF. One big advantage of such metal complexes is that they can be incorporated within enzymes like alcohol dehydrogenase from Thermonobacter brockii,[110] or protease enzymes like papain,[109,111] to synthesize a metalloenzyme, engineered as a biomimetic solution for NADH regeneration in enzymatic reactions.

Figure 9.

Proposed mechanism for the reduction of NAD+ through a [(Cp*H)Rh(bpy)]+ intermediate.

Analogous to enzymatic regeneration schemes with formate as the hydride donor, a study by Sadler and coworkers used [(η6-arene)Ru(en)Cl]PF6 (arene is hexamethylbenzene, p-cymene, indan; en is ethylenediamine) for reduction of NAD+ to 1,4-NADH with formate as the hydride donor.[112] The plot of TON vs. time was found to be a straight line, which indicated that the reduction of NAD+ was of zero order with respect to the NAD+ concentration. However, the turnover frequency vs. formate concentration plot showed Michaelis-type kinetics with respect to formate concentration, with a maximum TOF of 1.46 h−1 and Km = 58 mΜ (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Plot of TOF against formate concentration. Plot constructed based on data provided in Ref. [112].

3.1.2. Effect of metal-ligand interaction

Metal–ligand interaction is a major factor that drives the reducing capability of organometallic complexes.[113,114] A recent study evaluated to role of substituent position on bipyridine ligand upon the catalytic efficiency of RhIII complexes for NADH regeneration. For the series of –CH2OH substituents, the 5,5’-substituted bipyridine RhIII complex had the lowest reduction potential of all positional isomers and could effectively regenerate NADH with a notably high turnover frequency of 1100 h−1.[115] Several studies have deemed Rh complexes superior over other transition metal complexes. While in a prior study by Macchioni and co-workers,[116] the TOF achieved with a novel Ir complex was about 143 h−1, a very recent study has achieved a TOF of 3731 h−1 using a pyridine-2-sulfonamidate-substituted iridium complex.[117] The enhanced acidity of the central metal atom induced by the electron-withdrawing –SO2–moiety and an amine was attributed to have such an effect. In several studies, like the one conducted by Sadler and co-workers,[118] it is evident that the transfer hydrogenation of NAD+ as cofactor can be made reversible by varying the pH. Additionally, the reduced nicotinamide cofactor can be used as a hydride source to reduce ketones in presence of the cyclopentadienyl bipyridyl derivatives of RuII and IrIII catalysts and an appropriate enzyme.

3.2. Other methods of chemical cofactor regeneration

Early studies like that conducted by Jones et al.[119] demonstrated sodium dithionite as a possible reagent for regioselective regeneration of 1,4-NADH and the maximum TNcofactor was 105 with low product yield. However, enzymes are likely to suffer deactivation by high concentration of sodium dithionite, hence they did not gain attraction for further studies. For enzyme/cofactor ratio, which gave high yield, the TNcofactor observed was as low as around 30 and the overall process of cyclohexanone reduction was only viable in a preparative scale. The laccase-mediator system (LMS) is based on a combination of 2,2’-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS)-catalyzed oxidation of NAD(P)H and laccase-catalyzed reduction of molecular oxygen as terminal oxidant. LMS systems are useful for coupling with ADH-catalyzed oxidation reactions, and in a recent study, chemical regeneration of NAD+ was achieved with turnover numbers of 300 and 16000 with respect to NADH and ABTS, respectively.[120] Natural flavin adenine mononucleotide (FMN), which is a metal-free organocatalyst capable of NAD+ regeneration,[14] suffers from slow kinetics of hydride transfer, making it difficult to achieve high turnover numbers. In an impressive recent work, Zhu et al. developed a synthetic, water-soluble bridged flavinium organocatalyst and demonstrated atom-economical NADP+ regeneration using oxygen as the regenerating substrate.[121] With a TNcofactor of around 50, the reaction rate tripled with the NADP+ regeneration system compared to natural FMN catalyst. Further, the regeneration system supported three different glucose dehydrogenase-catalyzed oxidations of monosaccharides like xylose, mannose, and glucose.

Although the use of transition metal-based pentamethyl cyclopentadienyl bipyridyl complexes has successfully demonstrated NAD(P)H cofactor regeneration capability by chemical means, major limitations remain due to the highly regioselective nature of the hydride transfer, requirement of an electron donor, and mutual inactivation in chemoenzymatic systems.[17,32,105,122] Table 3 features some of chemically (mostly transition metal complex) catalyzed cofactor regeneration methods discussed in this section, and it can be observed that low turnover number in chemical regeneration is common, making it less viable when compared to enzymatic regeneration methods. Another limitation of transition metal complex-based regeneration, which impedes its large-scale application, is the cost associated with expensive metals like Rh and Ru and the fact that it is a homogeneous catalyst. Accordingly, its separation, recovery, and recycling are prohibitive challenges. In recent studies, attempts to immobilize such catalysts on solid support, particularly on periodic mesoporous organosilica, have gained attention,[123–126] which might pave the way for a new generation of chemocatalytic regeneration with improved cost for large-scale application.

Table 3.

Comparison of turnover numbers as observed in different studies using chemical regeneration methods.

| Catalyst | Substrate | TN [cofactor] | TN [catalyst] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (bis)phosphine Rh complex | H2 | 49[a] | 1470[a] | [102] |

| (Cp)*Rh(bpy) complex | formate | – | 43–170[a] | [109] |

| (Cp)*Rh(bpy) complex | formate | – | 550[b] | [115] |

| FMN derivative | O2 | 50[b] | – | [121] |

| ABTS | O2 | 300[a] | 16000[a] | [120] |

| (Cp)*Rh(bpy) complex | formate | 5.7[a] | 13[b] | [123] |

| (Cp)*Rh(bpy) complex | formate | 0.75[b] | 1500[a] | [127] |

| (Cp)*Rh(bpy) complex | formate | 20.5[b] | 41[b] | [128] |

| (Cp)*Rh(bpy) complex | formate | 10[b] | 50[b] | [129] |

| (Cp)*IrCl(phen) complex | formate | 2[b] | 1[b] | [130] |

Used directly from reference

Calculated from data provided in reference.

4. Electrochemical Regeneration Methods

Electrochemical methods are appealing for NADH regeneration processes as the electricity to drive the reaction can be sourced from renewable energy and the fixed electrode can facilitate easier product separation. In general, electrochemical regeneration can be broadly classified into direct and indirect electrochemical regeneration. Some of the of the earliest works on direct electrochemical regeneration of nicotinamide cofactors, both reduced (NADH) and oxidized (NAD+) forms, were done by Aizawa et al.[131,132] in attempts to demonstrate a cofactor regeneration strategy similar to those of chemical regeneration without having to use electron mediators. Although direct regeneration of enzymatically active cofactors has been successfully demonstrated, it has been proven to be difficult due to formation of inactive dimers, requirement of high cathodic overpotential for NAD+ reduction and slow kinetics of second electron transfer and protonation.[133–136] Aizawa et al. resolved the problem of inactive NAD2 dimer formation by covalently tethering the cofactor on to sodium alginate,[131] but also recognized that characterizing the cofactors during NADH regeneration was challenging due to their adsorption on the electrode surface.

While indirect regeneration can avoid issues associated with high overpotential and inactive dimer formation (in NAD+ reduction), the addition of electron shuttles can complicate downstream processing and purification. Here, we discuss the state of the art of direct and indirect electrochemical NAD(P)H and NAD(P)+ regeneration and provide yield and electrode potential as measures of comparison to other regeneration methods. Notably, the electrochemical regeneration literature rarely provides sufficient data to calculate TNenzyme and TNcofactor, complicating comparisons to other methods of cofactor regeneration.

4.1. Direct electrochemical regeneration of NADH

The electrochemical reduction of NAD+ for regeneration of 1,4-NADH is accomplished in two-step electron transfer[137] as shown below [Eqs. (1) and (2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

It is now recognized that direct electrochemical reduction of NAD+ additionally leads to the formation of enzymatically inactive dimers (Figure 11).[131,135,138–140] It was observed by Moiroux et al.[141] that the reduction of NAD+ to the free radical (NAD•) occurred at a cathodic potential of −0.858 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode (SHE), which rapidly dimerized and that the second electron transfer to NAD• occurred −1.358 V vs. SHE. It was concluded that the second electron transfer was kinetically less favorable than dimerization because of the adsorption of NAD• radical on the electrode surface. Several researchers have tested different electrode materials and modifications on them to overcome these problems.[135,137–140,142–145]

Figure 11.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in its oxidized form (NAD+), and its reduction to enzymatically active 1,4-NADH and enzymatically inactive dimer NAD2. R stands for adenosine diphosphoribose. Reproduced from Ref. [138]. Copyright (2006) with permission from Elsevier.

Ali et al. illustrated the effect of electrode potentials on NAD+ reduction using glassy carbon (GC) electrode and achieved yield as high as 96% of enzymatically active 1,4-NADH at high cathodic overpotentials.[139] It was observed that the reduction of NAD+ commenced at around −0.785 V vs. SHE but the slow rate of NADH production was evident from UV/Vis spectrophotometry. At high overpotential of around −1.685 V (vs. SHE), the absorbance plateau was reached at 3.5 h indicating a faster rate of NAD+ reduction to yield enzymatically active 1,4-NADH (more than 3 times higher). This trend was not observed when they tried electrochemical reduction of NAD+ on Au and Cu electrodes in an earlier work,[140] suggesting the importance of adsorption. On bare Au electrode, at low cathodic potential, the rate of NAD+ reduction was lower than that at higher overpotentials, but the yield of enzymatically active 1,4-NADH was inverse, varying from 75–28% at low versus high overpotentials. On bare Cu, a similar trend was observed as yield was found to vary from 71–52% at low versus high overpotentials. When the Au electrode was surface-modified with deposits of Pt, the yield of active reduced cofactor increased from 28 up to 63%. It was hypothesized that the Pt modification enhanced the kinetics of the second electron transfer and simultaneous hydrogenation of the NAD radical and minimized the dimerization of neighboring NAD radicals. In fact, it was shown in a contemporary study that changing the overpotential for NAD+ reduction from −0.273 to −0.573 V (vs. SHE) on a polycrystalline gold electrode, the ratio of 1,4-NADH to the inactive NAD2 dimer decreased from 0.78 to 0.28.[138] However, earlier studies suggest that the reduction peak at an electrode potential of −0.958 V vs. SHE on bare GC electrode corresponds to reduction of NAD+ to NAD radical in a single electron transfer step, but in case of a Ru-modified GC electrode at the same overpotential, a pronounced reduction peak appeared, corresponding to two-electron reduction of NAD+ to 1,4-NADH.[135,146] It was postulated that a submonolayer Ru modification on GC electrode can help avoid the formation of NAD2 dimer, thereby increasing the yield of NADH up to 96%. It was also evident from an electro-impedance study that the irreversible NAD+ reduction on Ru/GC was mass transfer-controlled below cathodic potentials of around −0.858 V vs. SHE. A possible reason for requirement of high overpotential for NAD+ reduction is the large electrontunneling distance between the electrode and the nicotinamide ring of the NAD+ molecule. Not only can Ru modification reduce the electron tunneling distance by reorientation of the adsorbed NAD species on the electrode surface, but also Ru sites act as proton providing sites.[135] It has also been reported that on GC electrodes, reduction of NAD+ is accompanied by hydrogen evolution.[135,142,144] This observation is further bolstered by relevant studies, which suggest that Ru-modified GC electrode is an excellent candidate for hydrogen evolution reaction.[147–149] In this context, a relatively recent study by Rahman et al. investigated two different types of Ru modification of glassy carbon electrodes (nanoparticle and film type) and studied the electrochemical response from each of these surface-modified electrodes with respect to NAD+ reduction and the role of hydrogen adsorption on the electrode surface during NAD+ reduction.[150] From cyclic voltametric studies, it was evident that Ru nanoparticle-modified GC electrode exhibited higher current density at the NAD+ reduction peak when compared to bare GC electrode but it could not clarify whether all of it was enzymatically active 1,4-NADH. In case of Ru-film-modified electrodes, a multifold increase in current density along with shift in the reduction peak voltage to around −0.678 V vs. SHE led the authors to conclude that hydrogen evolution reaction predominantly occurred in the Ru-film-modified electrode. However, it was finally concluded from UV absorption spectra at 340 nm that Ru-nanoparticle-modified GC electrode was more efficient with respect to NAD+ reduction. In a related work, nano-patterned Pt and Ni, electrochemically deposited on glassy carbon electrodes, were used to demonstrate direct reduction of NAD+ at lower electrode potentials compared to bare GC electrodes, and with higher recovery (up to 100%) of enzymatically active 1,4-NADH.[142] The nanoparticles on electrode surface provided adsorbed hydrogen at or adjacent to the NAD radical formation sites to promote faster radical protonation (Figure 12). Cyclic voltammograms showed characteristic peaks pertaining to hydrogen adsorption and desorption, which were not present on bare GC electrodes in the potential region investigated. Linear polarization voltammograms revealed that the current density on GC–Pt electrode was much higher than that on the bare GC electrode, which was due to the current generated due to hydrogen evolution reaction in addition to NAD+ reduction as observed by other researchers as well.[150] At an electrode potential of around −1.6 V, 100% recovery of 1,4-NADH was achieved with the nano-patterned GC–Pt electrode (Figure 13).[142]

Figure 12.

Representation of the bifunctional character of GC–Pt electrodes used for 1,4-NADH regeneration. Reproduced from Ref. [142]. Copyright (2012) with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 13.

Percentage recovery of enzymatically active 1,4-NADH at different electrode potential from reduction of 1 mm NAD+ in a batch electrochemical reactor using GC–Pt electrode. Reproduced from Ref. [142]. Copyright (2012) with permission from Elsevier.

Other carbon nanomaterials and transition metal-based electrodes have also been of great interest among researchers.[137,143–145,151] Ali et al. worked with bare Ti, Ni, Cd, and Co electrodes owing to their good hydrogen adsorption capacity.[144] The trend of regeneration of 1,4-NADH with increasing negative electrode potential was not uniform. The authors explained that Ti has a stronger affinity for H adsorption and a lower rate of hydrogen (H2) evolution reaction at a given potential than other metals. The larger concentration of surface adsorbed hydrogen facilitates desired NADH formation at a low electrode potential (96% yield at −0.185 V vs. SHE) compared to the undesired NAD dimerization. At higher potentials elevated rates of both NAD radical formation and H2 evolution explain the lower yield of NADH and the higher yield of NAD-dimer. By contrast, Ni, Cd, and Co electrodes exhibit lower M–Hads bond strength, higher H2 evolution rates, and lower yields of NADH. Despite its lower M–Hads bond strength than Pt, nickel nanoparticles were used to decorate multiwalled carbon nanotubes in a separate study of NADH regeneration.[137] A recovery of around 98% of 1,4-NADH was possible at an electrode potential of around −1.6 V. Although electrode modification for higher recovery of enzymatically active 1,4-NADH in direct electrochemical regeneration has been common, it suffers from limitations like higher expense of synthesis, loss of the modification layer, and possible denaturation of enzymes. Accordingly, their large-scale application has not been very widespread. To synthesize electrode material feasible for large-scale application, Barin et al. characterized pristine Cu foam, Ag- and Pt-modified Cu foam to study their efficacy for 1,4-NADH regeneration.[145] It was observed that foam deposition time affected the yield of NADH in all cases and pristine Cu foam could achieve higher yield of 1,4-NADH (up to 80%) than the bimetallic Cu foam electrodes. In subsequent study, the authors demonstrated coupled electroenzymatic CO2 reduction using the Cu foam electrodes in both batch and semi-continuous mode.[143,152] In the batch mode, up to 77% yield of active NADH was achieved at an electrode potential of −0.878 V vs. SHE. Although the authors did not comment on NADH regeneration efficiency in the semi-continuous mode, there was an increase in the final product (formate) yield by 42% compared to the batch mode. The increase in formate production could be attributed to the continuous removal of the product, which shifted the equilibrium towards product side and facilitated cofactor regeneration.

4.2. Indirect electrochemical regeneration of 1,4-NADH using electron mediators

Steckhan maintained that indirect electrochemical synthesis, via an electron transfer mediator, can offer a viable path for cofactor regeneration.[153] In these methods, the electron transfer mediator homogeneously reacts with the substrate (e. g., NAD+) leading to its reduction, after which the mediator is regenerated at the electrode surface. This approach avoids several problems associated with high overpotential requirements and inactive dimer formation. However, care must be exercised in selecting the mediator. Cp*RhIII(bpy) complexes are mostly used for this purpose, where the RhIII complex is reduced to RhI by the cathode, protonates to a Rh-hydride complex, which then transfers the hydride and the two electrons to the NAD(P)+ to regenerate the RhIII complex (Figure 14).[154] The principle was applied to regenerate NADH from NAD+ coupled with HLADH catalyzed ketone reduction using a bipyridyl rhodium complex as the electron mediator.[91] Although the method was effective, the intermediate Rh hydride was found to have been deposited on the electrode surface along with low observed rates of NAD+ reduction. Most of the studies thus far have not been successful in demonstrating direct electrochemical reduction of NAD+ to regenerate enzymatically active reduced cofactor with 100% recovery without surface modification of the electrode. As an alternative, indirect electrochemical regeneration of enzymatically active 1,4-NADH via electron mediators has been extensively studied to remediate the problem of NAD radical dimerization.[15] Following the footsteps of Steckhan and co-workers,[19] several researchers have demonstrated the use of electron mediators and discussed their efficiencies in regeneration of reduced nicotinamide cofactors while also limiting the formation of catalytically inactive NAD dimers.[126,154–162]

Figure 14.

Mechanism of [Cp*RhIII(bpy)Cl]Cl complex-mediated indirect electrochemical NADH regeneration method.

Among redox mediators, (2,2-bipyridyl)(pentamethyl cyclopentadienyl)rhodium [Cp*Rh(bpy)] is the most common owing to its less cathodic reduction potential to avoid direct NAD+ reduction and the capability of selective hydride transfer to yield the reduced form of the enzymatically active cofactor.[163] Hildebrand et al. functionalized the 2,2-bipyridine moiety to synthesize a series of substituted Rh complexes and investigated the possibility of faster overall rate to catch up to the rate of enzymatic reaction.[164] From a series of electrochemical measurements, it was clear that the electron transfer from the cathode to mediator was not influenced by change in the bipyridine moiety. Out of all the screened mediators, Cp*[Rh(4,4-dimethoxy-2-2’-bpy)] had a little higher reduction potential due to electron-donating effect but also showed significantly faster rate for cofactor regeneration leading to three times higher turnover frequency than the unsubstituted Cp*(bpy)Rh complex. Similar Rh complex like [Cp*Rh(bpy)Cl]+, which undergoes multistep redox transformation to enable efficient hydride transfer to regenerate 1,4-NADH, has been extensively studied in solution.[16,165,166] Free Rh complexes in solution might interact with the enzyme to decrease its activity, and it has also been observed that the pH of the medium can affect the proton transfer ability of Rh complex redox mediators, which can be attributed to loss of protons at higher pH.[155] Sivanesan and Yoon synthesized a bis(hydroxymethyl) pentamethyl bipyridyl Rh complex, which had a lower reduction peak at −0.549 V vs. SHE, about −0.17 V more anodic than the potential for NAD dimerization.[157] Reduction of NAD+ by this compound was achieved at −0.592 V vs. SHE, but the authors did not clarify the yield of enzymatically active 1,4-NADH. Walcarius et al. synthesized substituted derivatives of [Cp*Rh-(bpy)Cl]+ and studied the impact of immobilization of the mediator on to the SWCNT electrode surface. They observed mediator deactivation upon immobilization, which led to the suppression of catalytic reduction of NAD+.[154] The authors suggested that non-covalent immobilization methods, like π–π stacking, which has been previously applied to modify glassy carbon electrode with Rh complex-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) can be used to immobilize the mediator of interest, [Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O]2+, to avoid its deactivation on the electrode surface and retain the catalytic activity.[167] Despite its limitations, covalent immobilization of Rh complexes on electrode surface can be a useful tool to facilitate reusability of electrodes and separation of the final reaction products in biocatalytic reactions. It is even more convenient to have the enzyme in close contact with these mediators as demonstrated in a relevant experimental work by Zhang et al. with a turnover frequency of 1.3 s−1 and faradaic efficiency of 83%.[160] Bucky paper electrode was chosen for excellent electrical properties and the bipyridyl ligand was grafted on to the surface by electroreduction. Subsequent treatment with [RhCp*Cl2]2 was done to generate the complex and the enzyme was immobilized on this electrode by overcoating on a glassy fiber layer. In a more recent study, carboxylic acid moieties were introduced into the bipyridyl ligand of a RhIII complex, used to transfer electrons from a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) electrode coated with zirconia.[162] Owing to their excellent catalytic activity, Rh(bpy) complexes have been effectively featured in several research works of practical importance like CbFDH-catalyzed CO2 reduction[156] and quantitative detection of adenosine,[158] both of which require 1,4-NADH regeneration. In the case of photochemical cofactor regeneration, which is to be discussed later in this Review, the application of external electrical source is an alternative to sacrificial electron donors. Lee et al. have shown [Cp*Rh(bpy)Cl] can effectively transfer electrons from silicon nanowires, when used as photocathodes connected to an external bias in glucose dehydrogenase catalyzed production of l-glutamate from α-ketoglutarate (Figure 15).[168] Similar application of a Rh complex-mediated NADH regeneration is also featured in a water oxidation-driven photoelectrochemical cell (PEC) platform with simultaneous CO2 reduction by formate dehydrogenase.[169]

Figure 15.

Schematic illustration of the photo-electroenzymatic reaction using a silicon nanowire (SiNW) photocathode. Reproduced from Ref. [168]. Copyright (2014) with permission from Wiley-VCH GmbH & Co.

Other redox mediators like methyl viologen and ferredoxin can also be used as redox mediators in conjunction with NAD(P)H regenerating enzymes like diaphorase, ferredoxin-NAD(P) reductase, and other “VAPOR” (viologen accepting pyridine-nucleotide oxidoreductase) enzymes.[15] In conjunction with an oxidoreductase-catalyzed enzymatic reaction, lipoamide dehydrogenase can be used for 1,4-NADH regeneration via methyl viologen mediator, which transfers the electrons from the cathode. The regeneration typically takes place in a three-reaction sequence (Figure 16), as was shown in the work of Chen et al., where synthesis of lactate from pyruvate was achieved in a membrane packed-bed reactor.[170] Another instance of methyl viologen mediated electroreduction of NAD+ with lipoamide dehydrogenase (LDH), also known as diaphorase, occurs at low cathodic overpotential.[171] In-situ spectrophotometric study showed that the amount of NADH produced was incumbent on the LDH concentration while the rate of NADH regeneration depended on initial NAD+ concentration and followed Michaelis–Menten kinetics. Diaphoraseviologen conjugate formed by covalent attachment has been featured in a recent work by Dinh et al.,[172] which provides more flexible operational strategy as it can be separated from the reaction medium for further reuse. The authors also argued that the proximity of the enzyme-mediator would facilitate higher conversion of NAD+ based on their observation of different final conversion between viologen-diaphorase conjugate-catalyzed reaction versus native diaphorase-catalyzed reaction with exogenously added viologen.

Figure 16.

Three-reaction sequence of methyl viologen-lipoamide dehydrogenase-catalyzed NADH regeneration coupled to LDH-catalyzed lactate production. MV+/MV2+ = methyl viologen mediator; LipDH = lipoamide dehydrogenase; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase.

While it is evident that redox mediators can bypass high cathodic overpotential and dimer formation while regenerating enzymatically active 1,4-NADH during indirect electrochemical reduction, the process still requires downstream separation or immobilization of the cofactor on to the electrode surface. To overcome these problems, Yuan et al. demonstrated in their recent study that cobaltocene-modified poly-(allylamine), a redox polymer, can be potentially used to immobilize diaphorase, which can independently mediate the electroreduction of NAD+ in alcohol dehydrogenase-catalyzed reactions to produce methanol and propanol.[161] The attractive features of this regeneration system were relatively small applied overpotential and high current density, also considered to be an indicator of enhanced electron transfer kinetics. Table 4 enlists different direct and indirect electrochemical systems for NADH regeneration with electrode potentials and corresponding yield of 1,4-NADH.

Table 4.

Different electrode materials with corresponding yields, used in direct and indirect electrochemical regeneration methods.

| Electrode | Potential[a] [V vs. SHE] | Yield [%] | Type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC | −1.685 | 98 | direct | [139] |

| Cu | −0.585 | 52 | direct | [140] |

| Au | −0.585 | 28 | direct | [140] |

| Pt-modified Au | −0.485 | 63 | direct | [140] |

| GC-Pt | −0.985 | 100 | direct | [142] |

| GC-Ni | −0.885 | 100 | direct | [142] |

| Cu foam | −0.9 | 78 | direct | [143] |

| Ru-modified GC | −1.0 | 73 | direct | [150] |

| Cu | −0.8 | 91 | Rh mediator | [156] |

| GC or Pt | −0.8 | 36 | Rh mediator | [157] |

| Bucky paper | −0.575 | 9 | Rh mediator | [160] |

| FTO | −0.9 | 90 | Rh mediator | [162] |

Conversion of reference electrode potentials to potentials against SHE is done as outlined in Ref. [173].

4.3. Electrochemical regeneration of NAD+

The direct electrochemical regeneration of the oxidized cofactor, NAD+, reportedly occurs through a three-step process with the displacement of two electrons[136] shown as follows [Eqs. (3)–(5)]:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Similar to NAD(P)+ reduction, direct electrochemical oxidation of NAD(P)H on a bare electrode also takes place at a high overpotential.[17–178] Cyclic voltammograms from a carbon nanotube-modified GC electrode have been demonstrated to have a sharp, large anodic peak at −0.238 V vs. SHE, corresponding to direct oxidation of NAD(P)H, whereas on bare GC electrode, the anodic peak is observed at 0.961 V vs. SHE.[179] Although NAD radical dimerization does not seem to be a problem for direct electrochemical regeneration of the oxidized cofactor NAD(P), it is still necessary to modify the electrode surface or use redox mediators to overcome the high overpotential for electrochemical oxidation of NAD(P)H. Sosna et al. studied HMP (flavohaemoglobin)-modified graphite electrodes, but it was evident from CV studies that the electrode did not exhibit the characteristic redox peak from NADH oxidation.[180] However, when HMP was incorporated in an osmium-complex redox polymer matrix similar to that studied by Yuan et al.,[161] NADH oxidation was observed at reduced overpotentials. With an innovative advance by Megarity et al. in bioelectrocatalytic regeneration of NADP+, ferredoxin NADP reductase (FNR) enzyme was adsorbed in porous indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode, which was capable of regenerating the oxidized cofactor at a sufficiently low electrode potential of 0.08 V vs. SHE.[181,182] A second enzyme (alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme) was also co-immobilized in the ITO pores, which produced a nanoconfinement effect, leading to an increase in the local concentration of the NADPH, which facilitated the oxidative regeneration on the ITO electrode. This co-confined FNR/ADH enzyme on ITO electrode, also termed as “electrochemical leaf” by the authors, was used to explore the bidirectional nature of the NADP+/NADPH conversion by reversing the applied voltage to either direction to demonstrate ADH catalyzed deracemization of 4-phenyl-2-butanol to a single enantiomer.[183] This concept was extended to other studies as well, where multiple redox enzymes, including FNR, were nanoconfined in the electrode pores, used to demonstrate the production of aspartic acid,[184] and used to regenerate another biologically important coenzyme, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from its monophosphate form (AMP).[185] A TNcofactor of 936 was achieved in the former study, while in the latter, TNcofactor was around 90. However, the nanoconfinement effect of the electrochemical leaf provides a unique way of combining multiple redox enzymes near high local concentrations of the cofactors and reaction intermediates, leading to high reaction rates and redox biotransformations at relatively low electrode potentials.

In recent times, the promising future prospect of biofuel cells has been driving the research for more efficient bioelectrodes, which requires easy and fast electron transfer from the active site of the biocatalyst to the electrode surface. Efforts to decrease the high overpotentials for NADH oxidation have led researchers to investigate certain redox mediators like Nile blue[186] and methylene green-modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) electrodes[187] which have been employed for NAD(P)H oxidation in biofuel cell/biosensor applications. Integration of metallic nanoparticles like Au on MWCNT electrode surface displays excellent catalytic performance in terms of shifting the oxidation peak by 0.2 V.[188] Different types of surface-modified electrodes with their capabilities to decrease the NADH oxidation potential and immobilize enzymes and cofactors have been commonly used in biosensing applications.[189–192] Studies with SWCNT-coated Pt electrodes also yielded similar results in terms of steady-state current generation at fixed potential versus NADH concentration.[193] Linear amperometric response was observed with NADH concentration and the detection limit found to be as low as 0.17 μM.

Bioelectrocatalysis is an important field of interdisciplinary research, the aim of which is to achieve redox catalysis by synergistically coupling the advantages of biocatalysis like high selectivity and mild reaction conditions with those of electrocatalysis like possible utilization of renewable electricity.[194] The role of nicotinamide cofactors is indispensable as they facilitate the electron relay mechanism between the enzyme and substrate. Electrochemical regeneration has been so popular because they can eliminate additional enzymes and substrates required for cofactor regeneration in a cascade process and avoid complicated downstream separation processes to facilitate easier product recovery. Both direct and indirect electrochemical methods have been demonstrated to effectively reduce NAD+ to enzymatically active 1,4-NADH. However, most of these methods could not achieve TNs as high as enzymatic regeneration methods.[9,195] Table 5 lists different electrodemediator/catalyst combinations used for electrochemical NADH regeneration coupled to an enzymatic system and their corresponding turnover numbers. While TNcofactor are generally below 100, a single result from 2009 reached 18000 and incorporated methyl viologen mediator in a polymer modified electrode. This offers excitement to prompt reproduction and expansion of this technology.

Table 5.

Comparison of turnover numbers as observed in different studies using electrochemical regeneration methods.

| Electrode | Catalyst/mediator | Substrate | TNcofactor | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZrO2-coated FTO | Cp*RhIII(bpy complex | CO2 | 79[a] | [162] |

| glassy carbon | cobaltocene modified PAA/Diaphorse | formaldehyde | 5.2[b] | [161] |

| Bucky paper | Cp*RhIII(bpy complex | d-fructose | 2.6[a] | [160] |

| carbon paper | ethyl carboxy viologen/diaphorase | pyruvate | <1[b] | [172] |

| ITO | ferredoxin NADP reductase | pyruvate | 936[a] | [184] |

| Cu | Cp*RhIII(bpy complex | CO2 | 6.4[b] | [156] |

| carbon cloth | cobaltocene modified PAA/Diaphorse | ethyl 4-chloroacetoacetate | 30[b] | [196] |

| graphite | MV2+/AMAPOR | 2-oxoglutarate/NH4+ | 1000[a] | [197] |

| carbon plate | MV2+/diaphorase | pyruvic acid/CO2 | 18000[a] | [198] |

| Au-Hg | MV2+/diaphorase | benzoylformate | 158[a] | [199] |

| carbon Felt | Cp*RhIII(bpy complex | acetophenone | 64[a] | [200] |

| glassy carbon | BPV-LPEI/diaphorase | acetoacetyl coenzyme A | 8[b] | [201] |

Used directly from reference

Calculated from data provided in reference.

In some cases, electrode modifications required to minimize overpotential and dimer formation (in case of NAD+ reduction) are expensive and sometimes complicated. Alternatively, redox mediators can be used, but they still need to be separated from the product solution or immobilized on electrode surface for repeated usage. Toxicity and sustainability of certain inorganic redox mediators must be evaluated and improved in indirect electrochemical methods. Nevertheless, there is yet a lot of scope in the field of electrochemical regeneration of nicotinamide cofactors with regards to electrode modification, development of environmentally benign redox mediators, development of immobilization techniques without affecting the kinetics of the redox process, and applicability of such methods in conjunction with enzyme-coupled process for a wide range of product syntheses.

5. Photocatalytic Regeneration Methods

The concept of photobiocatalysis has emerged from the natural photosynthetic process, which uses solar energy to catalyze biochemical reactions with very high efficiency, and thus, light-driven biocatalysis has emerged as a subject of great interest.[202–206] Solar energy being an abundant source of energy, photochemical routes for visible light-driven cofactor regeneration coupled with homogeneous enzymatic synthesis have become increasingly popular among researchers and a discussion topic for several Reviews.[206–212] Photocatalytic cofactor regeneration involves the coupling of nicotinamide cofactor reduction or oxidation with a photocatalyst, which is a semiconductor with a low bandgap for promotion of electrons under photoexcitation. These electrons are then transferred to nicotinamide cofactors during the enzyme-catalyzed redox reactions.[213] A terminal reductant is required in all cases to balance the electron loss from the photocatalyst when the reduced cofactor regeneration is required. Different types of materials have been studied based on their ability to generate electrons under photoexcitation and relay the electrons to be used in biocatalytic redox reactions. One of the bigger challenges while selecting an appropriate photocatalyst has been the issue of electron-hole recombination. In this section we discuss photoenzymatic systems in which a photocatalyst capable of regenerating the oxidized (NAD+) or reduced (NADH) cofactor is coupled with an enzymatic system acting with or without an electron mediator. Quantitative comparisons based on turnover number and yield have been made wherever possible.

5.1. Photoregeneration of the reduced cofactor 1,4-NADH

The electron transfer mechanism in photocatalytic NAD(P)H regeneration is similar to that of chemical regeneration, where a sacrificial electron donor like ethylene diamine tetraacetate (EDTA)[30] is exhausted to donate electrons to the photo-generated holes on a typical photocatalyst like TiO2[28,29,214] or g-C3N4[215] created by visible light excitation. The electrons eliminated from the photocatalyst surface are then available for NAD(P)+ reduction, which is generally coupled to a redox enzyme-mediated reaction requiring the reduced NAD(P)H cofactor.

One of the early works using a cadmium sulfide (CdS) semiconductor coupled with hydrogenase enzyme for NADH photoregeneration using formate as the electron source was done by Shumilin et al.[216] The study established a direct electron transfer mechanism facilitated by the CdS photocatalyst in presence of a NAD-dependent hydrogenase. The electrons available from the formate photooxidation were transferred directly to the hydrogenase electron transport chain via the CdS semiconductor. A high ratio of hydrogenase/photocatalyst enables the enzyme to utilize all available reducing equivalents in the system up to a certain maximum value. More recent studies like that by Park et al.[30] used a mediator for more efficient electron transfer to the cofactor (Figure 17). The redox mediator in this case is a Cp*Rh(bpy) complex, which effectively utilized the photoexcited electrons as well as improved the photonic efficiency.[16,28,217–219] The novelty of the work is the solid-state synthesis of the photocatalyst W2Fe4Ta2O17, which has been found to be superior to the benchmark photocatalyst TiO2 in terms of rate of NADH generation. Pristine TiO2 has been reported by Wang et al. to be used for electron mediated regeneration of NADH where EDTA was used as the sacrificial electron donor.[220] The study investigated the effects of mediator concentration, different electron donors, and pH on the yield of NADH. The photo-regeneration of 1,4-NADH achieved a high yield; however, trace amount of enzymatically inactive 1,6-NADH was reported by the authors.

Figure 17.

Schematic diagram of the photocatalyst–enzyme-coupled bioreactor functioning under visible light.