Abstract

Acceptability has become a key consideration in the development, evaluation and implementation of health and social interventions. This commentary paper advances key learnings and recommendations for future intervention acceptability research with young people in Africa, aimed at supporting the achievement of developmental goals. It relates findings of the adolescent acceptability work conducted within the Accelerate Hub, since mid 2020, to broader inter-disciplinary literatures and to current regional health and social priorities. We argue that, in order to strengthen the quality and applied value of future acceptability work with young people, we need to do three things better. First, we need to consolidate prior findings on acceptability, within and across intervention types, to inform responses to current public health and social challenges and further the conceptual work in this area. Second, we need to better conceptualise acceptability research with young people, by developing stronger conceptual frameworks that define acceptability and its constructs, and predict its relationship with intervention engagement. Third, we need to better contextualise findings by considering acceptability data within a broader social and political context, which in turn can be supported by better conceptualisation. In this paper we describe contributions of our work to each of these three inter-connected objectives, and suggest ways in which they may be taken forward by researchers and practitioners in the future. These include aggregating evidence from past interventions to highlight potential barriers and enablers to current responses in priority areas; involving key actors earlier and more meaningfully in acceptability research; further developing and testing behavioural models for youth acceptability; and working collaboratively across sectors towards programmatic guidance for better contextualisation of acceptability research. Progress in this field will require an inter-disciplinary approach that draws from various literatures such as socio-ecological theory, political economy analysis, health behaviour models and literature on participatory research approaches.

Background

Acceptability is increasingly recognised as a key consideration in the development, evaluation and implementation of social interventions, particularly in the health sector (Magwood et al., 2019; Sekhon, Cartwright, & Francis, 2017). Defined by Sekhon et al. (2017, p. 4) as “a multi-faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a healthcare intervention consider it to be appropriate, based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention”, acceptability has been described as a necessary - although not sufficient - condition for high uptake and effectiveness of interventions (Diepeveen, Ling, Suhrcke, Roland, & Marteau, 2013; Sekhon et al., 2017). This provides a strong case to invest resources in acceptability research, whether linked to trials, other intervention evaluations or to intervention development and implementation. However, it is important to use these resources optimally to best support the achievement of developmental goals (Otim, Almarzouqi, Mukasa, & Gachiri, 2020).

Since 2020, as part of The UKRI GCRF Accelerating Achievement for Africa’s Adolescents Hub (Accelerate Hub), a network of multi-disciplinary researchers working to promote the wellbeing and opportunities of African adolescents, we have been conducting acceptability research focused specifically on this population group. Today’s young people are the continent’s future and they represent a priority population for health and social interventions in Africa (Salam, Das, Lassi, & Bhutta, 2016). Better understanding, assessing and strengthening their acceptability of interventions has the potential to lead to more effective interventions and better developmental outcomes (Stok et al., 2016). Our work within the Hub has comprised various components, including: a systematic review of acceptability studies with young people in Africa published over the past decade (Somefun et al., 2021); reviews of conceptual and empirical literature on acceptability across disciplines; reviews of health behaviour models that can help explain the adoption of new products or interventions; and on-going expert consultation within our Hub team and broader networks of young people, researchers, practitioners and other development partners. Our objectives were to aggregate the empirical evidence related to young people in Africa, better define the construct of acceptability in this population, and further instrument development to assess acceptability with adolescents and youth.

Our findings from this work have in part been published (Somefun et al., 2021) and are in part in the process of being finalised. The purpose of this commentary paper is to highlight key learnings and advance recommendations for the field, by relating our findings to current public health and social priorities in Africa, and to the broader literature. We argue that acceptability research, with young people in Africa and beyond, is too important a dimension of intervention development to continue with the largely ad-hoc, project-specific and fragmented approach that has characterized it to date. The concept of acceptability is currently defined differently across studies, sectors and literatures (Gooding, Phiri, Peterson, Parker, & Desmond, 2018; Sekhon et al., 2017; Somefun et al., 2021). The level and quality of reporting on empirical acceptability findings is also inconsistent as these are often reported briefly as ‘add-ons’ or one component of broader evaluations (Somefun et al., 2021). Moreover, there appears to be a limited amount of knowledge aggregation, transfer and exchange of acceptability findings to cross-inform similar projects with similar populations, or shape national and regional responses to public health and social challenges. To our knowledge, our recently published mapping review represents the first initiative to systematically bring together findings of acceptability studies with young people in Africa (Somefun et al., 2021).

To strengthen the quality and applied value of future acceptability work, we believe that we need to do three things better: consolidate, conceptualise and contextualize. First, we need to consolidate prior findings on acceptability, within and across intervention types, to inform responses to current public health and social challenges and further the conceptual work in this area. Conceptualise refers to the need to further theorize acceptability, and develop better conceptual frameworks that define its constructs and predict its relationship with intervention engagement outcomes. Contextualise refers to the need to better position adolescent acceptability data within a broader social and political context, and can in turn be facilitated by stronger conceptualisation. Each of these points is discussed in greater detail below.

1. Consolidate

Our work points to the importance of aggregating past acceptability findings for specific populations and intervention types. This can generate learnings for current and future national, regional or even global responses to public health and social challenges. The potential value of consolidating acceptability evidence is highlighted by two patterns emerging from our systematic review findings, considered in relation to the broader literature.

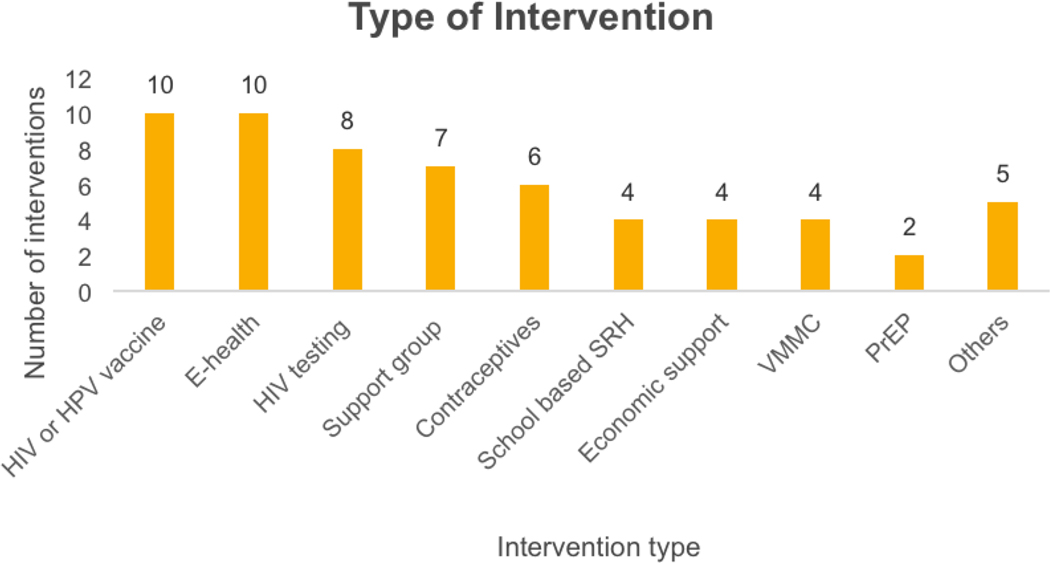

First, despite the diversity of settings, types, and modes of delivery of interventions assessed for acceptability with young adults in Africa over a decade (see Figure 1), several common themes emerged across studies, to explain why young people found them acceptable or not.

Figure 1:

Types and numbers of interventions assessed for acceptability, by acceptability studies with young people in Africa (2010–2020).

Somefun OD, Casale M, Haupt Ronnie G, et al. (2021). Decade of research into the acceptability of interventions aimed at improving adolescent and youth health and social outcomes in Africa: a systematic review and evidence map. BMJ Open 2021;11:e055160. Page 5.

These were: the intervention being easy to use or participate in, understanding of the intervention, the intervention allowing for greater autonomy (particularly among young women), feeling supported while participating in the intervention and feeling assured that one’s privacy and confidential information would be protected (Somefun et al., 2021). Overarching themes explaining low or lack of acceptability included: stigma, myths or distrust; lack of knowledge or support; conservative views about the intervention or its content; concerns around intervention costs and access; and fear of pain and side effects (Somefun et al., 2021). These findings suggest that certain factors may be important for African youth’s acceptance and uptake of programs, regardless of intervention type. Particular attention should therefore be paid to these crosscutting dimensions when designing and implementing interventions in this population.

Second, when considered in relation to the broader literature, our findings suggest that factors shaping acceptability for particular types of interventions or products may be similar, despite addressing different public or social health challenges at different points in time. For example, in a recent publication (Gittings et al., in press), we considered primary data on COVID-19 vaccine perceptions and intentions among South African adolescents, against our systematic review findings (Somefun et al., 2021) relating to HPV and hypothetical HIV vaccine interventions. The primary data was collected over closed Facebook groups in May 2021, as part of the Hub’s broader adolescent engagement work (Gittings et al., 2021). Our joint findings demonstrated significant overlap of reasons for vaccine acceptability and unacceptability. Common reasons explaining vaccine hesitancy were myths and inadequate understanding of vaccine interventions or the diseases they aimed to prevent, mistrust of scientists and government institutions, perceived low vulnerability to illness, fear of the injection and side effects, and questions around vaccine efficacy. In contrast, common reasons for vaccine acceptability included first-hand experience and information from trusted close sources (e.g. family, friends and peers), perceived effectiveness of the vaccines and a desire to be protected from illness (Gittings et al., in press).

These joint findings, and the broader literature on (mainly adult) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa (Menezes, Simuzingili, Debebe, Pivodic, & Massiah, 2021) suggest that acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines broadly reflects acceptability of other types of vaccines. These findings demonstrate how looking across the evidence relating to adolescent acceptability of specific past interventions can shine valuable light on possible barriers and enablers to current or future interventions, and elucidate areas for future exploration where there is little evidence. This may also be the case for the use of emergent technologies to respond to health issues that have been around for longer. One potential example is the recently piloted RTS,S malaria vaccine. Although recommended by the WHO for widespread use primarily for children in sub-Saharan Africa (The Lancet, 2021), acceptability among young caregivers and broader adult populations will be important. Other examples may be found in the rollout of recently approved long-acting injectable ART (Venkatesan, 2022) and new delivery mechanisms for HIV prevention using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In a recent South African study, participants drew on their knowledge, experience and community perceptions of the contraceptive implant, a similar technology already in use, to form their perspectives of a new HIV prevention implant (Krogstad et al., 2018).

Besides its applied value in informing social interventions, consolidating existing evidence can be important to support efforts to better conceptualise or build theory.

2. Conceptualise

Our acceptability work has highlighted the need to strengthen theory and frameworks to better guide acceptability research with young people, in Africa and beyond. It reinforced the lack of consistent definitions and measurement tools for acceptability, that makes comparability of findings challenging (Sekhon et al., 2017; Somefun et al., 2021). Of the 55 studies included in our systematic review, only seven provided an explicit definition of acceptability and only six referred to a conceptual framework; moreover, studies used a wide range of tools and indicators to assess acceptability, none of which were standardized and previously validated (Somefun et al., 2021). Our broader interdisciplinary reviews of acceptability literature also highlighted the lack of conceptual frameworks to guide acceptability research specifically with adolescents and youth.

To contribute to addressing this gap, we conducted inductive thematic analyses of both explicit definitions, where available, and operational definitions of acceptability used across studies included in our systematic review, and of acceptability findings highlighting young people’s reasons for acceptability or lack thereof i. We then reviewed emerging themes against an existing acceptability framework developed by Sekhon et al. (2017), the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability. We chose this as our reference framework, as it is, to our knowledge, derived from the first systematic approach to identifying how acceptability of healthcare (or other social) interventions has been defined, theorised, and assessed, and to unpack the various components of acceptability (Sekhon et al., 2017).

As illustrated in Table 1, there was overlap between our emerging themes and all seven components of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (affective attitude, self-efficacy, intervention coherence, perceived effectiveness, burden, opportunity costs and ethicality). However, our analyses also highlighted additional factors shaping young people’s intervention acceptability: alignment to the social and cultural norms and practices that characterize young people’s contexts and communities; relevance to young people’s needs and lived experiences; broader perceived (mainly social) positive effects of the intervention beyond the achievement of its intended purpose (e.g. effects on broader social relations or gender equity); perceived negative effects of interventions (e.g. negative impacts on social relations, social equity, anticipated side effects of biomedical interventions); and the perceived acceptability of other key individuals in the young person’s life (e.g. caregivers, peers or partners).

Table 1:

Themes emerging from our systematic review thematic analyses in relation to components of Sekhon et al’s (2017) TFA

| Theme emerging from our thematic analyses | Related component in TFA | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Emerging themes that overlap with components of Sekhon et al’s TFA | ||

| Overall feelings towards intervention | Affective attitude | How young people (YP) feel about the intervention |

| Understanding of intervention | Intervention coherence | Extent to which YP have adequate knowledge and understanding of the intervention |

| Perceived effectiveness | Perceived effectiveness | Extent to which the intervention is perceived to achieve its purpose |

| Costs related to participating | Burden and Opportunity Costs | Anticipated or experienced direct or opportunity costs required to participate in the intervention |

| Ease of use | Self-efficacy | YP’s confidence to perform the behaviours required to use or participate in the intervention |

| Alignment with individual value system | Ethicality | Extent to which the intervention fits with the YP’s individual value system |

| Emerging themes that extend beyond components of Sekhon et al’s TFA | ||

| Alignment with social and cultural norms and practices | Extent to which intervention is considered to be aligned with community values, or broader social, cultural and religious norms and practices | |

| Relevance | Extent to which YP consider the intervention relevant to their needs and lived experience | |

| Broader perceived positive effects | Broader anticipated or experienced positive social effects of the intervention for the YP, their household or community (beyond intervention objectives) | |

| Perceived negative effects | Anticipated or experienced negative consequences of the intervention for the YP, their household or community | |

| Perceived acceptability of others | YP’s perceived acceptability of the intervention by other key individuals in their lives | |

Drawing from these findings, we are currently developing a revised conceptual framework for acceptability with young people. We see this work as providing an essential foundation for two important further developments from a public health and social intervention perspective: 1) the development of a behavioural model, that hypothesizes relationships between young people’s acceptability and intervention engagement (Perski & Short, 2021); 2) the development of better tools and indicators to assess acceptability through applied research with young people.

Compared to Sekhon et al’s Theoretical Framework of Acceptability, our findings strongly emphasise the social and structural factors shaping young people’s acceptability of interventions. It has been argued that theories used for public health and behavioural change interventions often focus on individual variables, such as motivation and capabilities, and tend to neglect social and environmental variables related to context (Davis, Campbell, Hildon, Hobbs, & Michie, 2015). The social dimensions of acceptability are likely to be relevant to some extent for all population groups, but may be particularly important for adolescents, given the nature of this life phase (Stok et al., 2016). The need to better incorporate the social dimension of acceptability in conceptual frameworks for young people highlights our next point, which is the importance of contextualizing.

3. Contextualise

Intervention acceptability is not simply a result of individual characteristics and preferences, but also deeply embedded in the structural and sociocultural context in which young people live (Sabben et al., 2019). This is important to take into account when both designing research studies and interpreting findings. Findings of our review work, and the broader literature (Archary, Pettifor, & Toska, 2020; Chirwa-Kambole, Svanemyr, Sandøy, Hangoma, & Zulu, 2020) highlight the importance of better contextualising acceptability research, by positioning young people’s acceptability within its broader social and political context. Contextualising should encompass a consideration of both the influence of relationships and other social factors on young people’s acceptability, and acceptability among other key stakeholders who are central to intervention success (Chirwa-Kambole et al., 2020; Ybarra, Bull, Prescott, & Birungi, 2014).

A better understanding of the various potential influences on young people’s acceptability may best be achieved by adopting a social-ecological approach and drawing from social and gender norms theory. Social norms refer to the informal, mostly unwritten, rules that define acceptable, appropriate, and obligatory actions in a given group or society (Cislaghi & Heise, 2018). Over the last decade social norms theory has gained prominence in international development, informing work on child protection, health and governance policy and programming (Cislaghi & Heise, 2020). It has also reinforced the need to consider the relationships, norms and structures that influence individual attitudes and behaviours at various levels, from the family, church to wider government policies (Kilanowski, 2017; Marcus & Harper, 2014; Sommer & Mmari, 2015). This has led to public health agencies such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention embracing an approach to public health that looks at the complex of web of relationships within which an individual is located (Dahlberg & Krug, 2006).

The social-ecological approach and social norms theory may also be useful to better understand who has a vested interest in and direct influence on intervention success. These approaches have helped development practitioners identify key ‘reference’ groups that can shape norms and behaviours, and help ensure uptake and acceptability of an intervention (Michaeljon Alexander-Scott, Emma Bell, & Jenny Holden, 2016). A further potentially useful resource in this regard is political economy analysis (PEA), which has its roots in the governance and human rights sectors (Menocal et al., 2018). It typically involves analysis of power and the process of contestation and bargaining between economic and political elites, as well as understanding the more informal rules of the game (Menocal et al., 2018). Decisions about which social interventions to invest in are rarely politically neutral. Understanding who stands to win or lose from intervention decisions, what may be driving the agendas among donors and other key actors, and how this may affect their attitudes to interventions, are key to understanding what shapes notions of ‘social acceptability’ or ‘political acceptability’ (Sekhon et al., 2017; Tabourdeau & Grange, 2020). There have been various examples of politically informed and gender aware programming among organisations in Africa aimed at addressing gender inequities. Examples include the Voices for Change program in Nigeria, NGOs such as the South-African based Sonke Gender Justice, and civil society networks such as Girls Not Brides and Malawi Interfaith Action (Elaine Denny & Claire Hughes, 2017; Peacock, 2013). These organizations and networks have taken a ground-up approach to advocate for interventions that key community actors have identified as important for their wellbeing. They have worked with stakeholders, such as local religious and traditional leaders, whose buy-in is critical for addressing harmful gender norms, promoting effective implementation, and preventing backlash against programs supporting gender and broader social justice (Helen, Siow, Gibson, Hudson, & Roche, 2018).

How best to combine the various literatures and approaches described above, and apply them to better contextualize acceptability research, will require further thought and work, ideally to be taken forward through collaborations between researchers and practitioners. This could involve developing an overarching framework and programmatic guidance that draws on these different fields.

Moreover, while a comprehensive discussion of methodological approaches is beyond the scope of this paper, we should highlight that the timing, duration and quality of end-user and stakeholder engagement are key to better designing and evaluation interventions. Including key actors early on and potentially throughout the intervention life cycle, and more meaningfully engaging them in the research, is likely to increase buy-in and result in more responsive and impactful policy and programming (Archary et al., 2020; Gourlay et al., 2019). In this regard we could certainly draw from exploratory and experiential methods adopted in participatory and community-based research approaches (Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Krogstad et al., 2018).

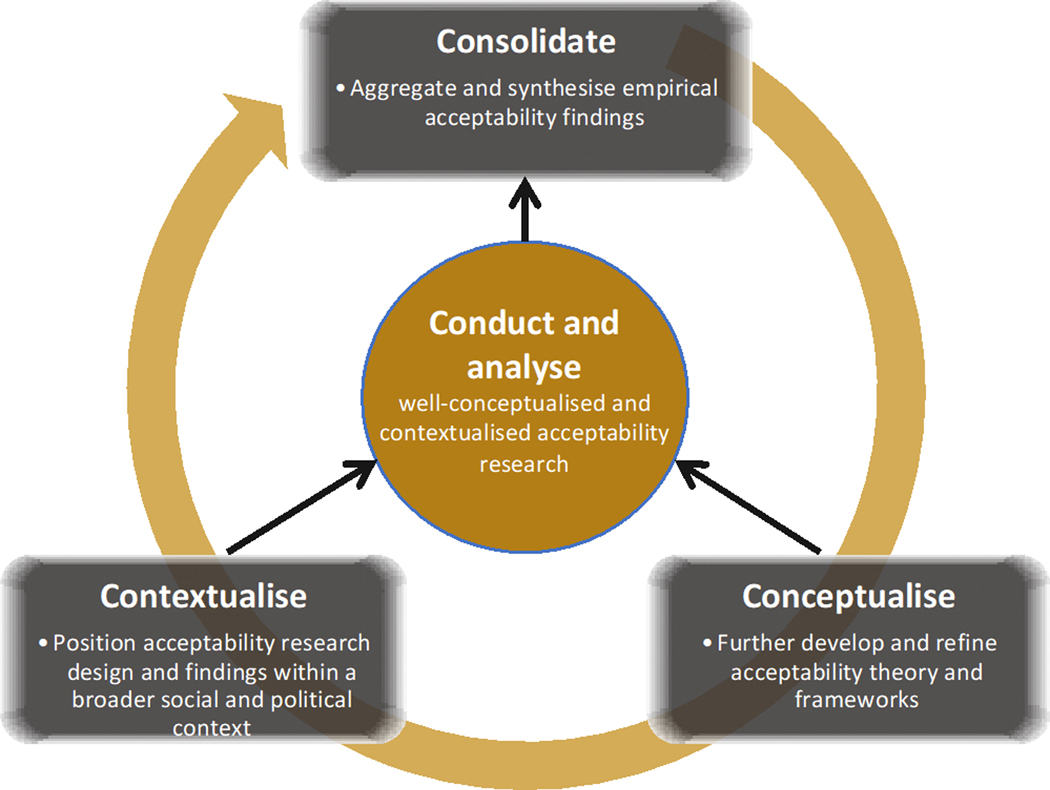

4. Consolidate, conceptualise, contextualise, conduct: a potential cyclic process of empirical research and theory building

While not mutually exclusive, the three components discussed above could be envisaged as elements of a cyclic process, where inductive and deductive phases follow each other and theory and data can be regarded as starting or end points (Schwarzer, 2014; Weinstein & Rothman, 2005) (see Figure 2).With each cycle the quality of a theory can be strengthened by improving, for example, its clarity of constructs, clarity of relationships between constructs and ability to explain causality (Davis et al., 2015). Similarly, with each cycle the quality of empirical research can be strengthened, through better- conceptualised and contextualised research designs and analyses.

Figure 2:

Potential cycle of inductive-deductive acceptability empirical research and theory building

Conclusion

We have reiterated the importance of acceptability research among young people and argued that, to improve the quality and relevance of this research, we need to better consolidate, conceptualise and contextualise. We recognise that the importance of these dimensions is not limited to acceptability research. Reviews of existing literature, the use of theoretical frameworks, and an adequate consideration of the context in which the research is to be conducted are core components of good research practice for health and social research more broadly. In this paper we have highlighted the considerable scope to strengthen these dimensions with regard to acceptability research, particularly with young people, and put forward some ideas as to how this can be best achieved.

We agree with the assertion that health behaviour theory development will happen more quickly if individual investigators build on each other’s work (Weinstein & Rothman, 2005). We hope that growing interest in intervention acceptability will continue, and that this work will be taken forward by researchers, policymakers and practitioners similarly concerned with the wellbeing of young people in Africa and globally. This should include: aggregating acceptability evidence from past interventions to highlight potential barriers and enablers to current health and social responses in priority areas; involving key actors earlier and more meaningfully in acceptability research; further developing and testing behavioural models for youth acceptability; and working collaboratively across sectors to develop programmatic guidance aimed at better contextualising acceptability research.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our funders: the UKRI GCRF Accelerating Achievement for Africa’s Adolescents (Accelerate) Hub (ES/S008101/1); the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (n° 771468); UK Medical Research Council [MR/R022372/1]; the Fogarty International Center and National Institutes of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health [K43TW011434]; UNICEF-ESARO; Oak Foundation [R46194/AA001] and [OFIL-20-057]; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) [1008200039].

Footnotes

To derive implicit definitions, in the absence of explicit definitions, we reviewed the methods, variables and indicators used by the study authors to assess acceptability, using a reasonable level of inference. A similar approach was used by Sekhon et al. (2017) in their development of the Theoretical Framework for Acceptability (Sekhon et al., 2017).

Contributor Information

Marisa Casale, School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape; Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford.

Rachel Yates, Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape; Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford.

Lesley Gittings, Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto; Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town.

Genevieve Haupt Ronnie, Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town.

Oluwaseyi Somefun, School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape.

Chris Desmond, Centre for Rural Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

References

- Archary M, Pettifor AE, & Toska E (2020). Adolescents and young people at the centre: global perspectives and approaches to transform HIV testing, treatment and care. J Int AIDS Soc, 23(Suppl 5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirwa-Kambole E, Svanemyr J, Sandøy I, Hangoma P, & Zulu JM (2020). Acceptability of youth clubs focusing on comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education in rural Zambian schools: a case of Central Province. BMC health services research, 20(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi B, & Heise L. (2018). Theory and practice of social norms interventions: eight common pitfalls. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 83. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0398-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi B, & Heise L. (2020). Gender norms and social norms: differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociology of health & illness, 42(2), 407–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A, & Jewkes R. (1995). What is participatory research? Social science & medicine, 41(12), 1667–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg LL, & Krug EG (2006). Violence: a global public health problem. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 11, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, & Michie S. (2015). Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 323–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diepeveen S, Ling T, Suhrcke M, Roland M, & Marteau TM (2013). Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC public health, 13(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny Elaine, & Hughes Claire. (2017). Attitudes, practices and social Norms survey: Endline Report, Voices for Change. Retrieved from https://www.itad.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/V4C-ASPN-Endline-Report-Print-Ready-ID-179962-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gittings L, Casale M, Kannemeyer N, Ralayo N, Cluver L, Kelly J, . . . Toska E. (in press). “Even if I’m well informed, I will never get it”: COVID-19 vaccine beliefs, intentions and acceptability among adolescents and young people in South Africa. South African Health Review. [Google Scholar]

- Gittings L, Toska E, Medley S, Cluver L, Logie CH, Ralayo N, . . . Mbithi-Dikgole J. (2021). ‘Now my life is stuck!’: Experiences of adolescents and young people during COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa. Global public health, 16(6), 947–963. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1899262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding K, Phiri M, Peterson I, Parker M, & Desmond N. (2018). Six dimensions of research trial acceptability: how much, what, when, in what circumstances, to whom and why? Social Science & Medicine, 213, 190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mthiyane NT, Orindi BO, Muuo S, Kwaro D, . . . Floyd S. (2019). Awareness and uptake of layered HIV prevention programming for young women: analysis of population-based surveys in three DREAMS settings in Kenya and South Africa. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helen D, Siow O, Gibson S, Hudson D, & Roche C. (2018). From Silos to Synergy: Learning from Politically Informed, Gender Aware Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Kilanowski JF (2017). Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model. Journal of Agromedicine, 22(4), 295–297. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2017.1358971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad EA, Atujuna M, Montgomery ET, Minnis A, Ndwayana S, Malapane T, . . . van der Straten A. (2018). Perspectives of South African youth in the development of an implant for HIV prevention. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21(8), e25170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwood O, Leki VY, Kpade V, Saad A, Alkhateeb Q, Gebremeskel A, . . . Sun AH (2019). Common trust and personal safety issues: A systematic review on the acceptability of health and social interventions for persons with lived experience of homelessness. PloS one, 14(12), e0226306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R, & Harper C. (2014). Gender justice and social norms-processes of change for adolescent girls. London: Overseas Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes NP, Simuzingili M, Debebe ZY, Pivodic F, & Massiah E. (2021). What is driving COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Sub-Saharan Africa? Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/what-driving-covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-sub-saharan-africa [Google Scholar]

- Menocal AR, Cassidy M, Swift S, Jacobstein D, Rothblum C, & Tservil I. (2018). Thinking and working politically through applied political economy analysis: a guide for practitioners. Center of Excellence on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance, USAID, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Michaeljon Alexander-Scott Emma Bell, & Holden Jenny. (2016). DFID Guidance Note: shifting social norms to tackle violence against women and girls (VAWG): Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG). [Google Scholar]

- Otim ME, Almarzouqi AM, Mukasa JP, & Gachiri W. (2020). Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A Conceptual Review of Normative Economics Frameworks. Frontiers in Public Health, 8(693). doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.584547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock D. (2013). South Africa’s Sonke Gender Justice Network: Educating men for gender equality. Agenda, 27(1), 128–140. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2013.808793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perski O, & Short CE (2021). Acceptability of digital health interventions: embracing the complexity. Translational Behavioral Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabben G, Mudhune V, Ondeng’e K, Odero I, Ndivo R, Akelo V, & Winskell K. (2019). A smartphone game to prevent HIV among young Africans (Tumaini): assessing intervention and study acceptability among adolescents and their parents in a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(5), e13049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam RA, Das JK, Lassi ZS, & Bhutta ZA (2016). Adolescent Health Interventions: Conclusions, Evidence Gaps, and Research Priorities. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 59(4S), S88–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R. (2014). Life and death of health behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review, 8, 53–56. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.810959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, & Francis JJ (2017). Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC health services research, 17(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somefun OD, Casale M, Haupt Ronnie G, Desmond C, Cluver L, & Sherr L. (2021). Decade of research into the acceptability of interventions aimed at improving adolescent and youth health and social outcomes in Africa: a systematic review and evidence map. BMJ Open, 11(12), e055160. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M, & Mmari K. (2015). Addressing structural and environmental factors for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-and middle-income countries. American journal of public health, 105(10), 1973–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stok FM, de Ridder DTD, de Vet E, Nureeva L, Luszczynska A, Wardle J, . . . de Wit JBF (2016). Hungry for an intervention? Adolescents’ ratings of acceptability of eating-related intervention strategies. BMC public health, 16(1), 5. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2665-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabourdeau G, & Grange C. (2020). From User Acceptance to Social Acceptance. [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet. (2021). Malaria vaccine approval: a step change for global health. Lancet, 398(10309), 1381. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02235-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan P. (2022). Long-acting injectable ART for HIV: a (cautious) step forward The Lancet Microbe, 3 (2), e94. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00009-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND, & Rothman AJ (2005). Commentary: Revitalizing research on health behavior theories. Health Education Research, 20(3), 294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Bull SS, Prescott TL, & Birungi R. (2014). Acceptability and feasibility of CyberSenga: an Internet-based HIV-prevention program for adolescents in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS care, 26(4), 441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]