Abstract

Background

Optimizing patient outcomes and reducing complications require constant monitoring and effective collaboration among critical care professionals. The aim of the present study was to describe the perceptions of physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers regarding the key roles, responsibilities and clinical decision-making related to mechanical ventilation and weaning in adult Intensive Care Units (ICUs) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

Methods

A multi-centre, cross-sectional self-administered survey was sent to physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers of 39 adult ICUs at governmental tertiary referral hospitals in 13 administrative regions of the KSA. The participants were advised to discuss the survey with the frontline bedside staff to gather feedback from the physicians, respiratory therapists and nurses themselves on key mechanical ventilation and weaning decisions in their units. We performed T-test and non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests to test the physicians, respiratory therapists, and nurses’ autonomy and influence scores, collaborative or single decisions among the professionals. Moreover, logistic regressions were performed to examine organizational variables associated with collaborative decision-making.

Results

The response rate was 67% (14/21) from physician directors, 84% (22/26) from respiratory therapist managers and 37% (11/30) from nurse managers. Physician directors and respiratory therapist managers agreed to collaborate significantly in most of the key decisions with limited nurses’ involvement (P<0.01). We also found that physician directors were perceived to have greater autonomy and influence in ventilation and waning decision-making with a mean of 8.29 (SD±1.49), and 8.50 (SD±1.40), respectively.

Conclusion

The key decision-making was implemented mainly by physicians and respiratory therapists in collaboration. Nurses had limited involvement. Physician directors perceived higher autonomy and influence in ventilatory and weaning decision-making than respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers. A critical care unit’s capacity to deliver effective and safe patient care may be improved by increasing nurses’ participation and acknowledging the role of respiratory therapists in clinical decision-making regarding mechanical ventilation and weaning.

Key Words: clinical decision-making, critical care, decision-making, intensive care unit, mechanical ventilation, role and responsibility

INTRODUCTION

Mechanical ventilation can be lifesaving but is associated with complications [1–3]. Thus, promptly weaning patients from the ventilator is pivotal in reducing the risk of adverse events [4,5]. Multi-disciplinary teamwork is vital to successful mechanical ventilation management and prompt weaning [6]. Effective collaboration among critical care professionals can be achieved through consistent, open, comprehensive communication and shared team goals [7,8]. This model ensures patient safety, minimizes adverse events and subsequently improves the quality of care and patient outcomes [8]. Ineffective team working leads to clinical decisions that are delayed, inconsistent or fragmented [9].

However, multi-disciplinary teams within Intensive Care Units (ICU) vary in the distribution of responsibilities, roles and skills among different professional groups. This variation is not just at the international level but even between individual ICUs within the same geographical region [10]. This variation can be attributed to many factors, including organizational structure, economic factors, cultural differences, various interprofessional skills/backgrounds and socio-political factors [11–13]. For example, in North America, studies on ventilation and weaning describe the role of respiratory therapists in mechanical ventilation-related clinical decision-making [14]. In contrast, in Europe, critical care nurses are the professional group responsible for these decisions [15].

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) the role of respiratory therapists shares similarities with the North American model [16]. The development of the respiratory therapy profession in KSA can be traced back to 1975 in Riyadh [17]. In 2002, the Saudi Commission for Health Specialists formally recognized the respiratory therapy profession by establishing the Respiratory Care Scientific Committee [16]. Today, respiratory therapists play a significant role in mechanical ventilation management and weaning in ICUs as a core responsibility of their daily routine in critical care [18].

The literature lacks empirical evidence related to the roles and responsibilities with regards to ventilation, weaning and clinical decision-making practices in adult ICUs. Most studies on this topic have discussed the implementation of ventilation and weaning in the form of physician-led, nurse-led or respiratory therapist-led protocols instead of describing the professional group actively responsible for key ventilation decisions [14,19–28].

A survey in Australia and New Zealand explored the professional groups responsible for decision-making on ventilation and weaning [6]. The study revealed that physicians and nurses make clinical decisions in collaboration. However, nurses in Australia and New Zealand were independently responsible for titrating ventilator settings to physiologic parameters [6]. Similarly, an international survey investigated the same question in eight European countries [15]. The present study showed that key decisions were also made in collaboration in most ICUs in those countries. Moreover, a Norwegian survey conducted among physician directors and nurse managers highlighted that nurse managers were perceived to have greater influence, autonomy and collaboration contact regarding mechanical ventilation decisions compared with physician directors’ perceptions [29]. In this study, for the professional group making these key decisions in relation to mechanical ventilation and weaning, we hypothesized that there would be a variation in the perceived roles and responsibilities between the health professional groups.

To our knowledge, there is no published report to investigate decision-making regarding ventilation and weaning in Saudi ICUs. Therefore, the present study aims to describe the perceptions of physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers regarding the roles, responsibilities and clinical decision making in relation to mechanical ventilation and weaning in Saudi adult ICUs.

METHODS

Study design and sampling

A multi-centre, cross-sectional, self-administered survey was sent to physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers. The centres that were chosen are governmental tertiary referral hospitals in 13 administrative regions of the KSA, which were identified through the Saudi Ministry of Health Statistical Yearbook 2020 [30]. We contacted the academic and training affairs unit of each hospital to distribute the online survey to the targeted professional groups. The survey was then distributed to the physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers in the same unit. A total of 39 adult ICUs that routinely apply mechanical ventilation to critically unwell patients were identified through communication with each hospital’s medical administration.

Study population

Physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers in the same unit of adult ICUs were invited to participate from September 2021 to November 2021. According to the telephone call made by the principal investigator to hospitals’ administrations, the number of eligible participants varied between hospitals because some hospitals with more than one adult ICU had only one physician director or one respiratory manager, while most ICUs had their own nurse manager. Thus, the number of responses from nurse managers was expected to be higher than for the other two groups. Furthermore, the participants were advised to discuss the survey with the frontline bedside staff to receive up-to-date information on key mechanical ventilation and weaning decisions in their units. ICUs for paediatrics and neonates, as well as units that do not provide mechanical ventilation on a regular basis, such as critical care and high-dependency units, were not included.

Survey development and pilot testing

The questionnaire was originally used in Australia and New Zealand in 2008 and refined in another study conducted in Europe in 2011 [6,15]. The survey was contextually adapted to the Saudi demographic and staffing in adult ICUs. The survey did not need to be translated into Arabic or other languages because the study population wrote and spoke English in their units.

The original survey was written to explore only nurses’ perceptions regarding key ventilation and weaning decisions. Thus, the same questions were replicated to fit the physician directors and respiratory therapist managers in the same unit to avoid specific group selection biases.

The adapted survey included seven main themes: (1) ICU demographics; (2) perceptions of physicians, respiratory therapists and nurses regarding responsibilities for six mechanical ventilation decisions; (3) ratios of each included professional to patients for patients receiving invasive and non-invasive ventilation in the ICU; (4) autonomy and influence of the included professionals on the decisions made regarding mechanical ventilation practices; (5) frequency of independent decisions made by each professional regarding seven key mechanical ventilation management decisions; (6) presence of ICU guidelines/policies/protocols for management and weaning of mechanical ventilation; and (7) frequency of using automated weaning modes in ICUs. In addition, an area for narrative thoughts or remarks was also included.

The validity of the survey was assessed by three members of an expert panel in critical care at Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Scotland, UK. The survey was then electronically sent to King Abdullah Medical Complex in Jeddah, KSA for a pilot test to assess its comprehensiveness and clarity. Three responses (one each) were received from an adult ICU’s physician director, respiratory therapist manager and nurse manager in the same unit. One comment on Question 5 regarding ICU demographics – “Number of staffed beds in your hospital” – was received and the question was modified to “Please identify the number of staffed beds (beds that you can admit patients to).” The pilot test responses were not included in the final analysis because it was conducted for validity and clarity purposes. The survey is available in Appendix 1.1

Data collection

The Survey Hero platform was used to collect responses from the participants. This platform has multiple qualities, including high data security and ease of use for the researcher and the participants [31]. No contact details or personal identifiers were requested to maintain the anonymity of participants. The principal investigator arranged for the survey to be administered by the academic and training affairs unit of the included hospitals. The academic and training affairs units sent the surveys out via email to the physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers in the same unit of each adult ICU in their hospitals. A weekly reminder email was sent to the participants to fill the survey.

Statistical methods

ICU demographics, such as hospital type, type of ICU, number of ICUs in the hospital, number of ICU beds and approximate number of beds staffed were analyzed using descriptive statistics to determine frequencies and percentages. Descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations and medians were used to determine the responses to the roles, responsibilities and clinical decision-making regarding mechanical ventilation and weaning in Saudi adult ICUs. T-test and non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used to test the autonomy and influence scores, collaborative or single decisions among the professionals respectively (T-test for two quantitative variables and U-test were for categorical variables). Moreover, multiple logistic regressions were performed to examine organizational characteristics, including staff ratios for invasive and non-invasive intubated patients, hospital teaching status, number of ICU beds, ICU types (ie, open vs. closed), perceived autonomy and contribution to ventilator decision-making, the use of automated systems and protocols/guidelines for the management of mechanical ventilation and weaning. Results of logistic regressions were presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two tailed, and a P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using the Statistical software StataSE version 13. However, the qualitative remarks concerning the autonomy and influence were analyzed on the bases of five underlying concepts of collaboration; sharing, partnership, interdependency, power and process [32].

Ethical considerations

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Saudi Central Ethical Committee at the Ministry of Health (Reference Number: 21 – 46E). Administrative approval from each included hospital was obtained according to the local guidelines before data collection.

RESULTS

ICU characteristics and response rate

The response rate was 67% (14/21) from physician directors, 84% (22/26) from respiratory therapist managers and 37% (11/30) from nurse managers. The major ICU characteristics of the surveyed ICUs are shown in Table 1. The most reported nurse-to-patient ratio among nurse managers was 1:2 for intubated patients (82%, 9/11) and >1:2 for non-invasive ventilated patients (55%, 6/11). In contrast, the ratio for respiratory therapists to invasively ventilated patients ranged from 1:2 to 1:10, with 82% (18/22) reporting a respiratory therapist-to-patient ratio >1:2. The respiratory therapist to non-invasive ventilated patient ratio reported was >1:2 for 86% (19/22) of ICUs.

TABLE 1.

ICU demographics by hospitals

| Hospital characteristics | Total | Al Noor Specialist Hospital – Mecca Region | Arar Central Hospital – Northern Borders Region | Asir Central Hospital – Asir Region | Dammam Medical Complex – Eastern Province | King Abdulaziz Specialist Hospital – Al Jawf Region | King Fahad Central Hospital – Jazan Region | King Fahad General Hospital – Medina Region | King Fahad Hospital – Al Bahah Region | King Fahad Specialist Hospital – Qassim Region | King Fahad Specialist Hospital-Tabuk Region | King Khalid General Hospital-Hail Region | King Khalid Hospital-Najran Region | King Saud Medical City – Riyadh Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital type | ||||||||||||||

| University affiliated | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Community/teaching | 36 (76.60) | 3 (100.00) | - | 3 (100.00) | 3 (100.00) | - | 5 (100.00) | 2 (100.00) | 3 (100.00) | 7 (100.00) | 2 (100.00) | 4 (100.00) | - | 4 (100.00) |

| Community/non-teaching | 11 (33.40) | - | 4 (100.00) | - | - | 2 (100.00) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 (100.00) | - |

| Primary ICU specialty | ||||||||||||||

| Mixed medical/surgical/trauma | 28 (59.57) | 2 (66.67) | 4 (100.00) | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | 1 (50.00) | 4 (80.00) | 1 (50.00) | 1 (33.33) | 4 (57.14) | 2 (100.00) | 2 (50.00) | 2 (40.00) | 2 (50.00) |

| Mixed medical/surgical | 14 (29.79) | 1 (33.33) | - | 1 (33.33) | 1 (33.33) | 1 (50.00) | 1 (20.00) | 1 (50.00) | 2 (66.67) | 3 (42.86) | - | 1 (25.00) | 1 (20.00) | 1 (25.00) |

| Medical (only) | 4 (8.51) | - | - | 1 (33.33) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (40.00) | 1 (25.00) |

| Trauma/ Neuro | 1 (2.13) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (25.00) | - | - |

| ICU type | ||||||||||||||

| Closed (intensivist-led) | 11 (23.40) | 1 (33.33) | - | - | 3 (100.00) | 1 (50.00) | 1 (20.00) | 1 (50.00) | - | - | - | - | - | 4 (100.00) |

| Open (under the care of physicians from any specialty) | 36 (76.60) | 2 (66.67) | 4 (100.00) | 3 (100.00) | - | 1 (50.00) | 4 (80.00) | 1 (50.00) | 3 (100.00) | 7 (100.00) | 2 (100.00) | 4 (100.00) | 5 (100.00) | - |

| Number of total ICU beds | ||||||||||||||

| 10–20 | 7 (14.89) | - | - | - | - | 2 (100.00) | 2 (40.00) | - | 1 (33.33) | - | 2 (100.00) | - | - | - |

| 21–40 | 23 (48.94) | 2 (66.67) | 4 (100.00) | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | - | - | 1 (50.00) | 2 (66.67) | 5 (71.43) | - | 4 (100.00) | 2 (40.00) | - |

| 41–60 | 13 (27.66) | 1 (33.33) | - | 2 (66.67) | 1 (33.33) | - | 3 (60.00) | 1 (50.00) | - | 2 (28.57) | - | - | 3 (60.00) | - |

| >60 | 4 (8.51) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 (100.00) |

| Total sample | 47 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

All data are presented as n (%); n = number of responses.

For six different models, only the number of ICU beds was found to significantly influence the collaborative decision on readiness to wean (P=0.04). The odds ratio was 3.88 (95%CI: 1.04–14.27), indicating that an increase in ICU beds will increase the likelihood of collaborative decisions on patients’ readiness to wean by 3.88 times.

Ventilation protocols and automated weaning modes used

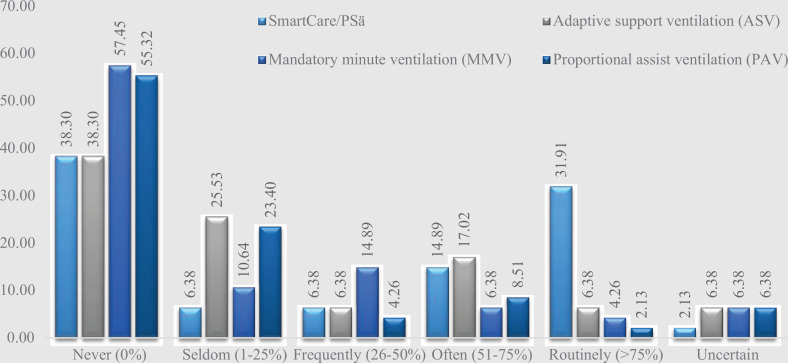

Of the 39 ICUs, 38 (97%) had a guideline/policy/protocol for the management of mechanical ventilation, 32 (82%) for weaning from mechanical ventilation and 35 (90%) for the management of patients for whom extubation failed. Automated weaning modes, including SmartCare/PSä, adaptive support ventilation, mandatory minute ventilation, and proportional assist ventilation, were found to be used in 59% (23/39) of the ICUs. However, SmartCare/PSä was the most commonly reported automated weaning mode, used over 50% of the time in the ICUs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Automated weaning modes in the ICUs

Interprofessional decision-making for ventilation and weaning

Six questions on the questionnaire assessed whether health professionals collaborate on six key decisions related to ventilation and weaning practices. All responses are summarized and presented in Table 2. For the analysis of collaborative responsibility among health professionals, physician directors and respiratory therapist managers significantly agreed on collaborating for most of the key decisions (P<0.01), while nurses’ limited involvement stood out (Table 3). Only a significant proportion of respiratory therapist managers (15/22, 68%; P=0.02) collaborated on the selection of initial ventilator settings, whereas the proportion of physician directors (7/15, 50%; P=1.00) and nurse managers (4/11, 36%; P=0.21) who collaborated on this was not significant.

TABLE 2.

Responsibility for ventilation and weaning decisions by health professionals

| Key mechanical ventilation decisions | Health professionals n (%) | Total n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician directors (n=14) | Nurse managers (n=11) | Respiratory therapist managers (n=22) | ||

| Initial ventilator settings | ||||

| Physician only | 5 (35.71) | 4 (36.36) | 2 (9.09) | 11 (23.40) |

| Collaborative | 7 (50.00) | 4 (36.36) | 15 (68.18) | 26 (55.32) |

| Respiratory therapists only | 2 (14.29) | 3 (27.27) | 5 (22.73) | 10 (21.28) |

| Nurses only | - | - | - | - |

| P-value | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.02* | - |

| Titration of ventilator settings | ||||

| Physician only | 1 (7.15) | 1 (9.09) | - | 2 (4.26) |

| Collaborative | 12 (87.71) | 6 (54.55) | 21 (95.45) | 39 (82.98) |

| Respiratory therapists only | 1 (7.14) | 4 (36.36) | 1 (4.55) | 6 (12.77) |

| Nurses only | - | - | - | - |

| P-value | <0.01* | 0.67 | <0.01* | - |

| Readiness to wean | ||||

| Physician only | 4 (28.57) | 6 (54.55) | 3 (13.64) | 13 (27.66) |

| Collaborative | 10 (71.43) | 5 (45.45) | 19 (86.36) | 34 (72.34) |

| Respiratory therapists only | - | - | - | - |

| Nurses only | - | - | - | - |

| P-value | 0.02* | 0.67 | <0.01* | - |

| Weaning method | ||||

| Physician only | 4 (28.57) | 1 (9.09) | 5 (22.73) | 10 (21.28) |

| Collaborative | 10 (71.43) | 9 (81.82) | 13 (59.09) | 32 (68.09) |

| Respiratory therapists only | - | 1 (9.09) | 4 (18.18) | 5 (10.64) |

| Nurses only | - | - | - | - |

| P-value | 0.02* | <0.01* | 0.22 | - |

| Readiness to trail of extubation | ||||

| Physician only | 4 (28.57) | 5 (45.45) | 3 (13.64) | 12 (25.53) |

| Collaborative | 10 (71.43) | 6 (54.55) | 19 (86.36) | 35 (74.47) |

| Respiratory therapists only | - | - | - | - |

| Nurses only | - | - | - | - |

| P-value | 0.02* | 0.67 | <0.01* | - |

| Weaning failure | ||||

| Physician only | 2 (14.29) | 2 (18.18) | 2 (9.09) | 6 (12.77) |

| Collaborative | 12 (85.71) | 8 (72.73) | 20 (90.91) | 40 (85.11) |

| Respiratory therapists only | - | 1 (9.09) | - | 1 (2.13) |

| Nurses only | - | - | - | - |

| P-value | <0.01* | <0.01* | 0.03 | - |

| Total | 14 | 11 | 22 | 47 |

P-value indicates the proportion of collaboration versus non-collaboration for the individual group.

Indicates significant P-values.

Note: The percentages do not add up to 100% due to overlapping data.

TABLE 3.

Collaborative responsibility for ventilator decision making among health professionals

| Key mechanical ventilation decisions | Health professionals n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician directors (n=14) | Nurse managers (n=11) | Respiratory therapist managers (n=22) | |

| Initial ventilator settings | |||

| Physician and respiratory therapist | 7 (50.00) | 4 (36.36) | 15 (68.18) |

| Physician, respiratory therapist and nurse | 1 (7.14) | - | 1 (4.55) |

| P-value | <0.01* | ||

| Titration of ventilator settings | |||

| Physician and respiratory therapist | 12 (85.71) | 6 (54.55) | 21 (95.45) |

| Physician, respiratory therapist and nurse | 3 (21.43) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (4.55) |

| P-value | <0.01* | ||

| Readiness to wean | |||

| Physician and respiratory therapist | 10 (71.43) | 5 (45.45) | 19 (86.36) |

| Physician, respiratory therapist and nurse | 2 (14.29) | 2 (18.18) | 3 (13.64) |

| P-value | <0.01* | ||

| Weaning method | |||

| Physician and respiratory therapist | 10 (71.43) | 9 (81.82) | 13 (59.09) |

| Physician, respiratory therapist and nurse | 1 (7.14) | - | 1 (4.55) |

| P-value | <0.01* | ||

| Readiness to trail of extubation | |||

| Physician and respiratory therapist | 10 (71.43) | 6 (54.55) | 19 (86.36) |

| Physician, respiratory therapist and nurse | 2 (14.29) | 1 (9.09) | 2 (9.09) |

| P-value | <0.01* | ||

| Weaning failure | |||

| Physician and respiratory therapist | 12 (85.71) | 8 (72.73) | 20 (90.91) |

| Physician, respiratory therapist and nurse | 3 (21.43) | 3 (27.27) | 4 (18.18) |

| P-value | <0.01* | ||

P-value indicates the proportion of collaboration between health professionals.

Indicates significant P-values.

However, a significant proportion of both physician directors (12/14, 85%; P<0.01) and respiratory therapist managers (21/22, 95%; P<0.01) collaborated on titration of ventilator settings, whereas the proportion of nurse managers (6/11, 54%; P=0.67) who collaborated was not significant. Moreover, a significant proportion of both physician directors (10/14, 71%; P<0.01) and respiratory therapist managers (19/22, 86%; P<0.01) were found to collaborate on the determination of patients’ readiness to wean, whereas the proportion of nurse managers (5/11, 45%; P=0.67) who collaborated was not significant.

In the determination of weaning method, only a significant proportion of physician directors (10/14, 71%; P=0.02) and nurse managers (9/11, 81%; P<0.01) reported collaboration, whereas the proportion of respiratory therapist managers (13/22, 59%; P<0.22) who reported collaboration was not significant. Further, regarding the patients readiness to trial of extubation decisions, only a significant proportion of physician directors (10/14, 71%; P=0.02) and respiratory therapist managers (19/22, 86%; P<0.01) collaborated on these decisions, unlike nurse managers (6, 54%; P=0.67). In the recognition of weaning failure decisions, all health professionals significantly reported collaborating on this decision: 12/14 physician directors (85; P<0.01), 20/22 respiratory therapist mangers (91%; P<0.01) and 8/11 nurse managers (73%; P=0.03).

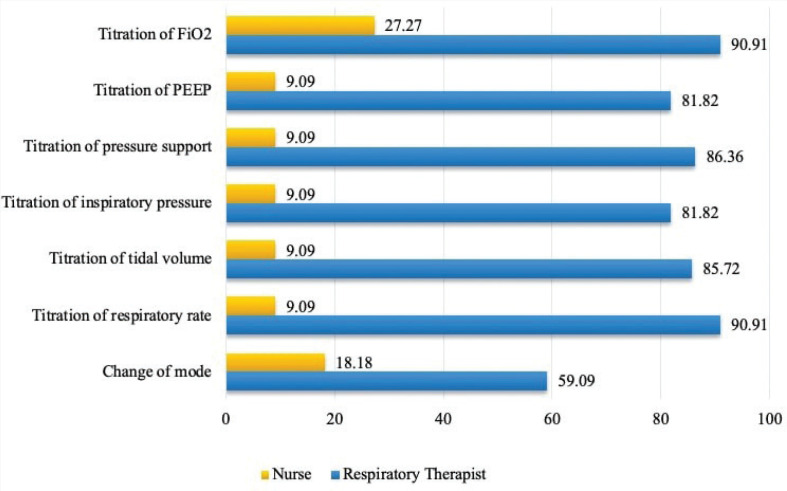

Respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers were asked about the type of ventilator setting decisions that were made independently without consulting physicians >50% of the time. The results showed variability in the decision making between the two groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The proportion of nurses and respiratory therapists who make ventilator setting decisions independently >50% of the time

Fraction Inspired Oxygen (FiO2), Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP)

Respiratory therapists were likely to be involved in making all types of ventilator decisions independently in their daily routine, with the least involvement in the change in mode (13/22, 59%; 95%CI: 36.46, 78.43). However, it was also clear that nurses adjusted all ventilator settings on their own more than 50% of the time. But nevertheless, they were most commonly active in adjusting FiO2 (3/11, 27%; 95% CI: 7.16, 64.59).

Physicians’, respiratory therapists’ and nurses’ autonomy and influence

Physicians had significantly greater autonomy in ventilation and weaning decision-making (mean: 8.29; SD: 1.49) than respiratory therapists (mean: 7.18; SD: 1.99) and nurses (mean: 4.45; SD: 1.81) (P<0.01). As such, on the influence rating scale, physicians showed significantly more influence on decision-making than respiratory therapists and nurses, with means of 8.50 (1.40) for physicians, 8.05 (1.50) for respiratory therapists and 4.18 (2.18) for nurses (P<0.01).

Physician directors’, respiratory therapist managers’ and nurse managers’ narrative remarks on autonomy and influence

A total of 19 remarks were received from all participants concerning their autonomy and influence on ventilation and weaning decision-making. Four concepts of collaboration were identified (shared responsibility, partnership, power and interdependency) from the conceptual framework of five concepts of collaboration by D’Amour et al [32].

Of the four subcategories, shared responsibility was the most frequently coded theme in the data. The predominant issue reported was the shared responsibility among respiratory therapists and nurses regarding changing or titration of ventilator settings due to respiratory therapist staff shortages (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Constructive content analysis of remarks concerning physicians’, respiratory therapists’ and nurses’ autonomy and influence

| Collaboration concepts | Physicians | Nurses | Respiratory therapists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared responsibility | - | Nurses used to change key settings only per physicians’ order and if respiratory therapists were not present at bedside (5*). | Physicians and nurses mostly make the changes due to a shortage of respiratory therapists (2*). |

| Partnership | Physicians discuss every vented case with respiratory therapists for management (2*). | - | - |

| Interdependency | Decisions are made according to the patient’s condition, ABG interpretation and physicians’ opinions in collaboration with respiratory therapists (2*). | - | - |

| Power | - | Decisions are influenced mainly by physicians and respiratory therapists without significant nurse inputs (2*). Nurses do not feel enough confidence to manage mechanical ventilation (1). |

Respiratory therapists have a reasonable influence on mechanical ventilation treatment plans during medical rounds (3*). Physicians sometimes refuse to follow respiratory therapists’ plans if they are not convinced of those plans (2*). |

Frequency of time the remark is expressed by physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and/or nurse managers. ABG Arterial blood gas.

Approximately one-half of the remarks reported power differences among team members. The nurse managers perceived that physicians and respiratory therapists made most of the decisions without significant input from the nurses. Nurses’ lack of confidence in the ability to manage mechanical ventilation was reported by nurse managers as an issue that limited the power of nurses to collaborate. Respiratory therapist managers were perceived as having a reasonable influence on the decisions made during the medical rounds; however, their collaborated decisions were sometimes “refused” (quote from respiratory therapist manager) by physicians if they were unconvinced of the idea.

Both respiratory therapists and nurses confessed that their autonomy and influence regarding ventilator decisions were directed by medical staff. Moreover, physician directors linked physicians and respiratory therapists’ autonomy for making decisions under the concept of “interdependence” with “patient’s condition, Arterial Blood Gas interpretation by respiratory therapists and physicians’ opinions” (quotes from physician directors).

However, organizational factors such as a guideline/policy/protocol for the management of mechanical ventilation and weaning as well as hospital type did not explain all groups’ perceived autonomy and influence.

DISCUSSION

The literature review identified that the bulk of existing studies were limited to the European context and thus there was a critical literature gap for ventilation management practices and decisions in the KSA and the Middle East region at large. Therefore, the present study aimed to describe the perceptions of physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers regarding the key roles, responsibilities and clinical decision-making related to mechanical ventilation and weaning in adult ICUs in the KSA.

The present study shows that the inter-professional collaboration approach was the predominant model in ventilation and weaning decision-making at the studied Saudi adult ICUs. These results are consistent with previous studies, which investigated ventilation and weaning decision-making among critical care across Europe, Australia and New Zealand [6,15,29]. However, the results of these studies demonstrated that inter-professional collaborative decision-making was implemented between physicians and nurses only, which is inconsistent with the current study’s findings. The reason for this was that the mentioned studies were conducted in settings with distinct organizational structures and staff hierarchies.

Our findings showed that ventilation and weaning decision-making in the Saudi context is implemented mainly by physicians and respiratory therapists in collaboration in terms of most key decisions and nurses have limited involvement. However, the physician directors showed the least collaboration with respiratory therapists in the initial ventilator setting.

A European survey found that physicians were likelier than nurses to select initial ventilator settings [15]. A possible explanation for this is that physicians are in a position to lead the ventilation initiation where intubation takes place and such a critical situation could affect the collaborative decision. Furthermore, the respiratory therapists were found to be the least collaborative in determining the weaning method. This finding was also reported from a physician director’s perspective toward nurses [29]. Physician directors assumed that nurses are less collaborative in determining the weaning method. These results can likely be attributed to the skills and capabilities of the health professional in charge. Thus, the weaning method is determined based on the in-charge health professional’s matched skills and capabilities.

In our study, nurse managers showed low collaborative responses compared with physician directors and respiratory therapist managers in most key decision-making. The reason for this could be that nurses believe that ventilation and weaning decisions are the role of physicians or respiratory therapists; therefore, their involvement is limited. A comment received in the narrative analysis from a nurse manager was that “nurses used to change key settings only per physicians’ orders and if a respiratory therapist was not present at the bedside,” which supported our speculation.

Although most key ventilator decisions were made in collaboration, variability in perceived collaboration toward ventilation and weaning decision-making between physicians, respiratory therapists and nurses was clearly recognized. This result was supported by similar findings from previous studies [33–35]. Professional, organizational and systemic factors that create power differences and delineate role responsibility are likely to cause variation in the degree of collaboration [36]. The findings of the present study could be used to infer certain elements that may have influenced the power gradients and decision-making practices between the groups. Nurse managers identified the inability of nurses to control mechanical ventilation as a problem that hampered their ability to engage in the conceptual framework analysis of interprofessional collaboration.

Critical care nurses have been described as an “around-the-clock surveillance system” [37]. Previous studies have demonstrated that critical care nurses play a significant role in ventilation and weaning collaborative decision-making. In a Norwegian survey, physicians acknowledged that nurses share information that informs clinical decisions [29]. Rose et al linked the occurrence of inter-professional collaboration with nurses’ assessment and knowledge of the patient to inform clinical decisions [6]. Rose and Nelson noted that nurses are in an excellent position to identify psychological and physiological indications of weaning readiness and failure, to titrate ventilation, to interpret patients’ altered pathophysiology and to monitor changes to the adjusted ventilator settings [11].

However, our study findings are contrary to previous studies’ findings on critical care nurses’ roles [6,15,29]. Neither the physician directors, respiratory therapist managers nor the nurses themselves perceived the significance and value of nurses’ input in collaborative decision-making. According to the narrative analysis, nurse managers have linked their collaborative inputs to the shortage of respiratory therapist staff and medical orders. It seems that nurses were unable to share their experiences and knowledge with the ICU multidisciplinary team. These results warrant further investigation with a larger cohort to examine the collaborative relationship between physicians, respiratory therapists and nurses and its effect on patient outcomes.

The current study found that respiratory therapists were likely to make all ventilator settings independently (without consulting physicians) in their daily routines, with the least involvement in the mode change. By contrast, nurses rarely made all ventilator settings independently but they were most frequently involved in titrating FiO2. To a certain degree, these results align with the autonomy and influence-rating scale results rated by respiratory therapists and nurses. Respiratory therapist managers had reasonable autonomy and influence, while nurse managers rated their autonomy and influence as much lower than respiratory therapists. However, physician directors rated their autonomy and influence as higher than other professions. As a result, the narrative analysis revealed that both the respiratory therapists’ and the nurses’ autonomy and influence were directed by the medical staff. Respiratory therapists managers revealed in the narrative comments that when respiratory therapists propose their conscious choices to physicians, they are rejected if the physicians are not convinced. Previous studies have suggested that less independence and autonomy of an ICU inter-professional team is associated with a medically dominated clinical environment [38,39]. Therefore, it is conceivable to assume that the implemented ventilation and weaning protocols were either physician-led or physician-directed practices.

Respiratory therapists’ high independence in making decisions might be due to their increasing input in ventilation and weaning decision-making. Another possible explanation for respiratory therapists’ increases in independent decision-making, as explained by some physician directors in their narrative responses, is that decisions are taken based on the arterial blood gas interpretation, which is generally performed by respiratory therapists.

Within the literature, for respiratory therapists and critical care nurses who take on the role of respiratory therapists in some settings, the level of protocol and autonomy in ventilator decision-making was linked with greater job satisfaction, improved patient outcomes, lower staff turnover, improved patient satisfaction, lower job stress and subsequently improved quality of care [8,38,40–46].

The autonomy and influence of nurses are negatively affected by many factors, including lack of experience and competency and the presence of protocol [6,15,29]. However, experience and competency factors are not necessarily implied with respiratory therapists, as their core qualification is in respiratory anatomy and physiology, the management of ventilator changes and weaning readiness [47]. Another potentially fruitful avenue for future research is to investigate the possible issues that limit inter-professional autonomy and influence ventilation and weaning decisions.

Another noteworthy finding of the current study is that only the number of ICU beds was found to statistically significantly influence the collaborative decision on readiness to wean. However, we found no association between the presence of a guideline/policy/protocol and inter-professional collaboration or autonomy. It suggested that protocols, arguably, will have little impact in a clinical environment that encourages inter-professional collaboration [6,15,29]. We observed that an increase in the patient-to-health professional (nurse and respiratory therapists) ratio would decrease the likelihood of collaborative decisions for all six key ventilator and weaning decisions.

The effects of an increased patient-to-nurse ratio, when the nurse has the same ability or role as a respiratory therapist, on patient care and outcomes have been exclusively described [11,15]. Previous study noted that inter-professional collaboration is influenced by the patient-to-nurse ratio and the presence of a protocol [11]. However, there are no such data for respiratory therapists; hence, little is known about the implications of respiratory therapists’ staffing patterns on patient outcomes.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide insight into the practical application of automated weaning modes in the KSA. The automated weaning modes, including SmartCare/PSä, adaptive support ventilation, mandatory minute ventilation and proportional assist ventilation, were found to be used in 57% of the ICUs. However, SmartCare/PSä was the most commonly reported automated weaning mode (used over 50% of the time in the sampled ICUs).

The purpose of automated weaning modes is to improve ventilatory support adaption to the demands of patients through constant monitoring and real-time interventions [48]. A review of randomized and quasi-randomized trials comparing spontaneous breathing trials with automated weaning modes showed the effectiveness of SmartCare/PSä utilization to wean patients from mechanical ventilation [49]. It was found that weaning with SmartCare/PSä reduced weaning time, ICU stays, time to successful extubation and the percentage of patients receiving ventilation for more than 7 and 21 days when compared with non-automated weaning methods. However, other studies have demonstrated no effect between the two systems [50,51]. Further research is necessary to close these knowledge gaps because there are few papers in the literature on the use of automated weaning modes in the KSA.

Limitations

The present study has a number of shortcomings that must be noted. First, despite our anticipation that the response rate for nurse managers would be higher than that of physician directors and RT managers, the response rate for nurse managers was under-represented. As a result, nursing responsibilities may have been overestimated.

Second, only government referral tertiary hospitals were involved in the survey’s execution. As a result, there are certain restrictions on how broadly these findings may be applied, particularly to other private or public hospitals that lack comparable ICU workforces and organizational structures.

Third, we failed to link physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers from the same units at hospitals with more than one ICU. This was due to the approach we chose to present the survey to the stakeholders and our efforts to protect anonymity.

Fourth, there may be political prejudice among potential respondents, which may have influenced how they responded because they were concerned about how the results may affect their actions in the future.

Finally, we acknowledge that there are a number of confounding variables that may have an impact on our findings, including the demographics of our sample, the length of time they have been licensed as practitioners, their level of expertise in critical care, and the type of training or education they have received in this area.

Key recommendations

It is recommended that further research should assess the impact of professional, organizational and systemic factors that create power differences and delineate role responsibility between professionals regarding the degree of inter-professional collaboration. Additionally, further investigation with a larger cohort to examine physicians’, respiratory therapists’ and nurses’ collaborative relationships and their effect on patient outcomes is warranted.

As the results show, variable perceived inter-professional collaboration and blurred professional boundaries, standardized ventilation and weaning practices and promoting collaborative decision-making via using a plan in the form of a collaborative ventilation and weaning board and flow sheet might improve practice. As respiratory therapists and nurses are members of an inter-professional team, more acknowledgement of respiratory therapists’ role and more involvement of critical care nurses in sharing their knowledge and experience to inform clinical decision-making may positively impact a unit’s ability to provide effective and safe care.

CONCLUSION

The results show variable perceived inter-professional collaboration and blurred professional boundaries toward key decision-making for ventilation and weaning between physician directors, respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers. The diversity of inter-professional perspectives and blurred professional boundaries could have an impact on clinical practice. As a result, clinical decision-making regarding ventilation and weaning may be delayed, inconsistent or fragmented [9]. However, the most dominant approach to key decision-making in relation to mechanical ventilation and weaning was implemented mainly by physicians and respiratory therapists in collaboration and nurses had limited involvement. In addition, physician directors perceived higher autonomy and influence in ventilatory and weaning decision-making than respiratory therapist managers and nurse managers. The present study developed a profile of the roles and responsibilities of key ventilation and weaning decisions of ICU workforces in the KSA, which will serve as a basis for future studies.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials are available at https://www.cjrt.ca/wp-content/uploads/Supplement-cjrt-2022-053.docx.

DISCLOSURES

Acknowledgements

We would also like to thank the Saudi Central Ethical Research Committee at the Ministry of Health, the Health Affairs office of each administrative region in the KSA and the administrations of the sample hospitals for their support and facilitation during the data collection period. Special thanks go to the respondents from all the sampled ICUs for completing the survey during these uncertain times due to COVID-19.

Authors contribution

Literature search: MGA; Data collection: MHA, JAA, HOA, MAA; Study design: MGA ; Analysis of data: MGA; Manuscript preparation: MGA, SKA; Review of manuscript: MGA, JKS, MAA.

Sources of financial support

Authors received no financial support to conduct the present study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Saudi Central Ethical committee at the Ministry of Health (Reference Number: 21 – 46E). Administrative approval from each included hospital was obtained according to the local guidelines before data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burns SM, Dempsey E. Long-term ventilator management strategies: Experiences of two hospitals. AACN Clin Issues 2000;11(3):424–41. 10.1097/00044067-200008000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes MR, Smith CD, Tecklenburg FW, Habib DM, Hulsey TC, Ebeling M. Effects of a weaning protocol on ventilated pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) patients. Top Health Inf Manage 2001;22(2):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacIntyre NR. Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support: A collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 2001;120(6):375S–95S. 10.1378/chest.120.6_suppl.375S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dries DJ, McGonigal MD, Malian MS, Bor BJ, Sullivan C. Protocol-driven ventilator weaning reduces use of mechanical ventilation, rate of early reintubation, and ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2004;56(5):943–52. 10.1097/01.TA.0000124462.61495.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djunaedi H, Cardinal P, Greffe-Laliberte G, Jones G, Pham B. Does a ventilatory management protocol improve the care of ventilated patients? Respir Care 1997;42(6):604–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose L, Nelson S, Johnston L, Presneill JJ. Workforce profile, organisation structure and role responsibility for ventilation and weaning practices in Australia and New Zealand intensive care units. J Clin Nurs 2008;17(8):1035–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reader TW, Flin R, Cuthbertson BH. Team leadership in the intensive care unit: The perspective of specialists*. Crit Care Med 2011;39(7):1683–91. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318218a4c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheelan SA, Burchill CN, Tilin F. The link between teamwork and patients’ outcomes in intensive care units. Am J Crit Care 2003;12(6):527–34. 10.4037/ajcc2003.12.6.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen BS, Severinsson E. Physicians’ perceptions of protocol-directed weaning in an intensive care unit in Norway. Nurs Health Sci 2009;11(1):71–6. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00433.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Depasse B, Pauwels D, Somers Y, Vincent JL. A profile of European ICU nursing. Intensive Care Med 1998;24(9):939–45. 10.1007/s001340050693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose L, Nelson S. Issues in weaning from mechanical ventilation: Literature review. J Adv Nurs 2006;54(1):73–85. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angus DC, Sirio CA, Clermont G, Bion J. International comparisons of critical care outcome and resource consumption. Crit Care Clin 1997;13(2):389–408. 10.1016/S0749-0704(05)70317-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke T, Mackinnon E, England K, Burr G, Fowler S, Fairservice L. A review of intensive care nurse staffing practices overseas: What lessons for Australia? Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2000;16(4):228–42. 10.1054/iccn.2000.1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoo GWS, Park L. Variations in the measurement of weaning parameters: A survey of respiratory therapists. Chest 2002;121(6):1947–55. 10.1378/chest.121.6.1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose L, Blackwood B, Egerod I, et al. Decisional responsibility for mechanical ventilation and weaning: An international survey. Crit Care 2011;15(6):R295. 10.1186/cc10588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Otaibi HM, AlAhmari MD. The respiratory care profession in Saudi Arabia: Past and present. Ann Thorac Med 2016;11(4):237. 10.4103/1817-1737.191872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeBakey ME, Beall AC Jr, Feteih N, et al. King Faisal Specialist hospital and research centre cardiovascular surgery unit: Progress report after two years. Cardiovasc Res Center Bull 1980;18(3):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kacmarek RM. The mechanical ventilator: Past, present, and future. Respir Care 2011;56(8):1170–80. 10.4187/respcare.01420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ely EW, Baker AM, Dunagan DP, et al. Effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med 1996;335(25):1864–9. 10.1056/NEJM199612193352502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris J. Weaning from mechanical ventilation: Relating the literature to nursing practice. Nurs Crit Care 2001;6(5):226–31. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norton L. The role of the specialist nurse in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation and the development of the nurse-led approach. Nurs Crit Care 2000;5(5):220–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson J, O’Brien M. Challenges for the future: The nurse’s role in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1995;11(1):2–5. 10.1016/S0964-3397(95)81126-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De D. Clinical skills: A care plan approach to nurse-led extubation. Br J Nurs 2004;13(18):1086–90. 10.12968/bjon.2004.13.18.16142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saura P, Blanch L, Mestre J, Valles J, Artigas A, Fernandez R. Clinical consequences of the implementation of a weaning protocol. Intensive Care Med 1996;22(10):1052–6. 10.1007/BF01699227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horst HM, Mouro D, Hall-Jenssens RA, Pamukov N. Decrease in ventilation time with a standardized weaning process. Archiv Surg 1998;133(5):483–9. 10.1001/archsurg.133.5.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 1997;25(4):567–74. 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marelich GP, Murin S, Battistella F, Inciardi J, Vierra T, Roby M. Protocol weaning of mechanical ventilation in medical and surgical patients by respiratorycare practitioners and nurses: Effect on weaning time and incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 2000;118(2):459–67. 10.1378/chest.118.2.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnan JA, Moore D, Robeson C, Rand CS, Fessler HE. A prospective, controlled trial of a protocol-based strategy to discontinue mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169(6):673–8. 10.1164/rccm.200306-761OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haugdahl HS, Storli S, Rose L, Romild U, Egerod I. Perceived decisional responsibility for mechanical ventilation and weaning: A Norwegian survey. Nurs Crit Care 2014;19(1):18–25. 10.1111/nicc.12051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MOH . Statistical Yearbook Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia: @SaudiMOH; 2021. <https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Pages/Default.aspx> (Accessed October 28, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.ServeyHero . Privacy Policy / GDPR 2021. <https://www.surveyhero.com/privacy> (Accessed October 28, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Amour D, Oandasan I. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: An emerging concept. J Interprof Care 2005;19(sup1):8–20. 10.1080/13561820500081604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeves S, Lewin S. Interprofessional collaboration in the hospital: Strategies and meanings. J Health Serv Res Policy 2004;9(4):218–25. 10.1258/1355819042250140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, Freeth D, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(3). 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin JS, Ummenhofer W, Manser T, Spirig R. Interprofessional collaboration among nurses and physicians: Making a difference in patient outcome. Swiss Med Wkly 2010;140(3536):140. 10.4414/smw.2010.13062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.San Martín-Rodríguez L, Beaulieu M-D, D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M. The determinants of successful collaboration: A review of theoretical and empirical studies. J Interprof Care 2005;19(sup1):132–47. 10.1080/13561820500082677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, Sloane DM, Silber JH. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA 2003;290(12):1617–23. 10.1001/jama.290.12.1617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaboyer W, Najman J, Dunn S. Factors influencing job valuation: A comparative study of critical care and non-critical care nurses. Int J Nurs Stud 2001;38(2):153–61. 10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00052-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coombs M. Power and conflict in intensive care clinical decision making. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2003;19(3):125–35. 10.1016/S0964-3397(03)00040-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metcalf AY, Stoller JK, Habermann M, Fry TD. Respiratory therapist job perceptions: The impact of protocol use. Respir Care 2015;60(11):1556–9. 10.4187/respcare.04156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, et al. Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Crit Care Med 1999;27(9):1991–8. 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanchfield KC, Biordi DL. Power in practice: A study of nursing authority and autonomy. Nurs Adm Q 1996;20(3):42–9. 10.1097/00006216-199602030-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finn CP. Autonomy: An important component for nurses’ job satisfaction. Int J Nurs Stud 2001;38(3):349–57. 10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00065-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyle DK, Bott MJ, Hansen HE, Woods CQ, Taunton RL. Manager’s leadership and critical care nurses’ intent to stay. Am J Crit Care 1999;8(6):361. 10.4037/ajcc1999.8.6.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kennerly S. Perceived worker autonomy: The foundation for shared governance. J Nurs Adm 2000;30(12):611–7. 10.1097/00005110-200012000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wade GH. A model of the attitudinal component of professional nurse autonomy. J Nurs Educ 2004;43(3):116–24. 10.3928/01484834-20040301-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blackwood B. Can protocolised-weaning developed in the United States transfer to the United Kingdom context: A discussion. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2003;19(4):215–25. 10.1016/S0964-3397(03)00053-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lellouche F, Brochard L. Advanced closed loops during mechanical ventilation (PAV, NAVA, ASV, SmartCare). Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2009;23(1):81–93. 10.1016/j.bpa.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burns KEA, Lellouche F, Nisenbaum R, Lessard MR, Friedrich JO. Automated weaning and SBT systems versus non-automated weaning strategies for weaning time in invasively ventilated critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014(9):CD008638. 10.1002/14651858.CD008638.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dongelmans DA, Veelo DP, Paulus F, et al. Weaning automation with adaptive support ventilation: A randomized controlled trial in cardiothoracic surgery patients. Anesth Anal 2009;108(2):565–71. ttps://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e318190c49f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rose L, Presneill JJ, Johnston L, Cade JF. A randomised, controlled trial of conventional versus automated weaning from mechanical ventilation using SmartCare™/PS. Intensive Care Med 2008;34(10):1788–95. 10.1007/s00134-008-1179-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]