Abstract

Background

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is a rare autosomal recessive lipid storage disease caused by a mutation in the CYP27A1 gene. Due to the disruption of bile acid synthesis leading to cholesterol and cholestanol accumulation, CTX manifests as premature cataracts, chronic diarrhea, and intellectual disability in childhood and adolescence. This report presents a case of CTX with an unusual phenotype of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) in middle age.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old woman presented with behavioral and personality changes. She showed disinhibition, such as hoarding and becoming aggressive over trifles; compulsive behavior, such as closing doors; apathy; and dietary change. The patient showed a progressive cognitive decline and relatively sparing memory and visuospatial function. She had hyperlipidemia but no family history of neurodegenerative disorders. Initial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images showed a high signal in the periventricular area, and brain spectroscopy showed hypoperfusion in the frontal and temporal lobes, mimicking bvFTD. However, on physical examination, xanthomas were found on both the dorsum of the hands and the Achilles tendons. Hyperactive deep tendon reflexes in the bilateral biceps, brachioradialis, and knee and positive Chaddock signs on both sides were observed. Four years later, FLAIR images showed symmetrical high signals in the bilateral dentate nuclei of the cerebellum. Her serum cholestanol (12.4 mg/L; normal value ≤6.0) and 7α,12α-dihydroxycholest-4-en-3-one (0.485 nmol/mL; normal value ≤0.100) levels were elevated. A novel likely pathogenic variant (c.1001T>A, p.Met334Lys) and a known pathogenic variant (c.1420C>T, p.Arg474Trp) of the CYP27A1 gene were found in trans-location. The patient was diagnosed with CTX and prescribed chenodeoxycholic acid (750 mg/day).

Conclusions

This report discusses the case of a middle-aged CTX patient with an unusual phenotype of bvFTD. A novel likely pathogenic variant (c.1001T>A, p.Met334Lys) was identified in the CYP27A1 gene. Early diagnosis is important because supplying chenodeoxycholic acid can prevent CTX progression.

Keywords: behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, CYP27A1 gene mutation, novel likely pathogenic variant, case report

Introduction

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX, OMIM: 213700) is an autosomal recessive lipid storage disease caused by a mutation in the CYP27A1 gene (chromosome 2q33-qter) (1). Mutations in the gene encoding the mitochondrial enzyme sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27) can lead to decreased bile acid synthesis, increased cholestanol production, and sterol accumulation in multiple systems, including the nervous system, tendons, and eye lenses (2). It is a rare disease with an incidence of ~5 per 100,000 people worldwide, and 10 cases have been reported in South Korea (3–10). This report discusses a case of CTX with an unusual phenotype of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD).

Case description

A 60-year-old woman visited the Department of Neurology, Samsung Medical Center in South Korea because of progressive abnormal behavior, personality change, and cognitive decline over the past 4 years. At the age of 56, she showed disinhibition, such as hoarding plastic bottles or paper cups and becoming aggressive over trifles. She also showed compulsive behavior, such as closing doors; apathy; and dietary change. The patient showed a progressive cognitive decline and relatively sparing memory and visuospatial function. However, at the age of 58, she started to show memory impairment as she could not remember where she put her money. She also showed visuospatial dysfunction as she got lost in her neighborhood and could not find her car in a parking lot. At the age of 60, disinhibition and apathy worsened along with increased appetite. In addition, she complained of nonspecific dizziness and unstable gait. She had a history of hyperlipidemia and no family history of neurological diseases in her first- or second-degree relatives.

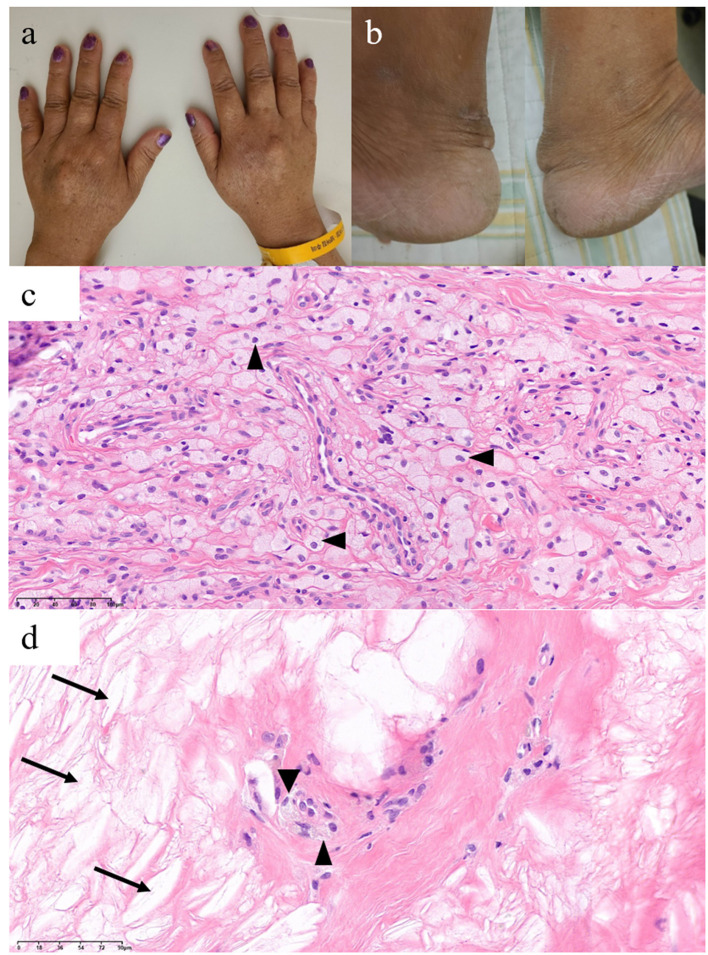

On neuropsychological tests, her Mini-Mental State Examination score was 22, her clinical dementia rating score was 1, and the detailed results revealed global cognitive impairment (Table 1). On neurological examination, she showed hyperactive deep tendon reflexes in the bilateral biceps, brachioradialis, and knee and positive Chaddock signs on both sides. Although no gross gait abnormalities or ataxia were observed, she showed bilateral sway on tandem gait. Upon physical examination, xanthomas were found in the bilateral dorsum of the hands and the Achilles tendons (Figures 1a, b). A skin biopsy revealed diffuse infiltration of foamy macrophages in the dermis, and a tendon biopsy revealed numerous lipid crystal clefts and a small number of foamy macrophages (Figures 1c, d).

Table 1.

The neuropsychological test results.

| Age | 60 years old (before treatment) | 61 years old (after treatment) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain (highest possible score) | Raw score | z-score | Raw score | z-score |

| Attention | ||||

| Digit span forward (9) | 6 | 0.04 | 6 | 0.04 |

| Digit span backward (8) | 3 | −0.93 | 3 | −0.93 |

| Language | ||||

| Korean version of the Boston naming Test (60) | 37* | −2.05 | 35* | −2.39 |

| Visuospatial function | ||||

| Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (36) | 23.5* | −2.93 | 27* | −1.81 |

| Memory | ||||

| Seoul verbal learning test | ||||

| Immediate recall (1st, 2nd, 3rd free recall trials: 12 + 12 + 12 = 36) | 12* | −1.97 | 19 | −0.39 |

| Delayed recall (12) | 1* | −2.52 | 3* | −1.65 |

| Recognition score (24) | 13* | −4.32 | 19* | −1.11 |

| Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test | ||||

| Immediate recall (36) | 0* | −2.43 | 5* | −1.65 |

| Delayed recall (36) | 4* | −1.89 | 3* | −2.05 |

| Recognition score (24) | 17* | −1.61 | 10 | 0.04 |

| Frontal/executive function | ||||

| Controlled oral word association test | ||||

| Semantic, animal (20) | 6* | −2.43 | 9* | −1.68 |

| Semantic, supermarket (20) | 5* | −2.33 | 11* | −1.23 |

| Phonemic, sum of scores from 3 alphabets (45) | 8* | −1.90 | 3* | −2.47 |

| Stroop test | ||||

| Word reading (112) | 111 | 17 | ||

| Color reading (112) | 52* | −2.06 | 73 | −0.82 |

| General cognition | ||||

| Mini-mental state examination (30) | 22* | −3.69 | 26* | −1.23 |

| Global severity scales | ||||

| Clinical dementia rating (sum of boxes) | 1 (6) | 0.5 (4) | ||

| Global deterioration scale | 5 | 4 | ||

| Neuropsychiatric inventory | 38/144 | 9/144 | ||

Figure 1.

Xanthomas findings of this patient with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Xanthomas on bilateral (a) dorsum of the hands and (b) Achilles tendons. Histological findings of the dorsum of the hand (c) and Achilles tendon (d) xanthomas show foamy macrophages (arrowheads) and lipid crystal clefts (arrows).

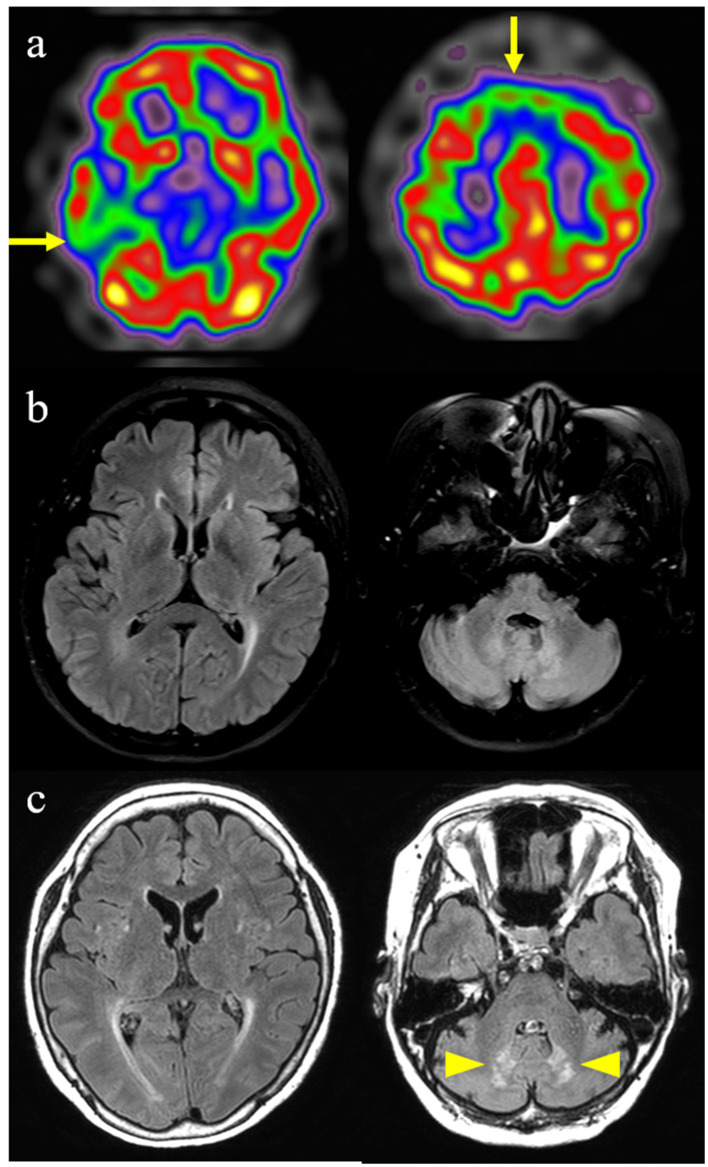

Brain spectroscopy performed at 56 years of age showed hypoperfusion in the bilateral frontal and right temporal lobes (Figure 2a). A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed during the same period showed slight periventricular white matter changes on T2 FLAIR images, but no other specific abnormalities were observed (Figure 2b). An 18F-flutemetamol PET scan was interpreted as negative for amyloid. Her clinical phenotype and spectroscopy findings corresponded to probable bvFTD based on Rascovsky criteria for bvFTD (12).

Figure 2.

Brain imaging findings of this patient with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. (a) Brain spectroscopy shows hypoperfusion in bilateral frontal and right temporal lobes (arrows). (b) Initial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image shows slight periventricular white matter changes. (c) Follow-up fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image performed 4 years later shows the progression of periventricular white matter changes and newly developed symmetrical hyperintense lesions in the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum (arrowheads).

However, follow-up T2 FLAIR images, performed at the age of 60 years, demonstrated progression of periventricular white matter changes and newly developed symmetrical hyperintense lesions in the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum (Figure 2c). Although no evidence of peripheral neuropathy was found in the nerve conduction study (NCS), her posterior tibial somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) and visual evoked potential tests (VEP) were abnormal. Bone mineral osteodensitometry revealed the presence of osteoporosis. Ophthalmic examination revealed age-related macular degeneration with no cataracts or retinal invasion.

CTX was suspected based on xanthomas and follow-up brain MRI findings; thus, serum cholestanol and related gene tests were performed. Serum cholestanol (12.4 mg/L; normal value ≤6.0) and 7α,12α-dihydroxycholest-4-en-3-one (0.485 nmol/mL; normal value ≤0.100) levels were elevated. The serum levels of very-long-chain fatty acids for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy and arylsulfatase A for metachromatic leukodystrophy were within the normal range. In genetic analysis with whole exome sequencing, a likely pathogenic variant (LPV) (NM_00784.4:c.1001T>A, p.Met334Lys) and a pathogenic variant (PV, NM_000784.4: c.1420C>T, p.Arg474Trp) were found in the CYP27A1 gene, which was confirmed to be translocated via genetic testing of her daughter and son, who carried each variant as heterozygous. The c.1001T>A (p.Met334Lys) had not been reported previously and the c.1420C>T (p.Arg474Trp) has been observed in several CTX patients and classified as pathogenic in ClinVar. (ClinVar accession number as VCV000004259.12) (13–18). The patient was finally diagnosed with CTX and was prescribed with chenodeoxycholic acid (750 mg/day). Eight months after the treatment, her disinhibition symptoms decreased. In neuropsychological tests, she showed improvements in visuospatial function, memory, frontal/executive function, general cognition, and global severity scales (Table 1).

Discussion

This report discusses the case of a middle-aged CTX patient with an unusual phenotype of bvFTD, confirmed by a novel likely pathogenic and a known pathogenic variant, as compound heterozygous variants, (c.[1001T>A];[1420C>T], p.[Met334Lys];[Arg474Trp]) in the CYP27A1 gene with elevated serum cholestanol and 7α,12α-dihydroxycholest-4-en-3-one levels.

Our CTX case is unique in that disease onset occurred during middle age and that the patient showed an unusual bvFTD phenotype. CTX is usually found in adolescence or early adulthood and is characterized by premature bilateral cataracts, chronic diarrhea in childhood, premature atherosclerosis, tendon xanthoma, and progressive neurological dysfunction (cerebellar and pyramidal signs, intellectual disability, peripheral neuropathy, and seizures) (19). However, our patient had no such premature symptoms and showed slow progressive abnormal behavior during late middle age. Her slowly progressive symptoms of disinhibition, apathy, compulsive behavior, and dietary changes and her frontotemporal hypoperfusion met the clinical criteria for probable bvFTD (12). There have been two rare case reports of CTX presenting with frontal dysfunction in adults. A 44-year-old woman with the FTD phenotype was reported in Japan (20). This patient had increased serum levels of cholestanol with a heterozygous mutation in the CYP27A1 gene. Another 53-year-old man with the FTD phenotype of CTX was reported in the United States. This patient was compound heterozygous for two mutations in CYP27A1 (NM_000784.3 (CYP27A1): a missense mutation of 1016C > T on one allele and a 1435C > G mutation on the other allele) (21). The two previously reported cases, along with our case, suggest that the middle-age-onset bvFTD phenotype might be a subtype of CTX.

The FTD phenotype of CTX can be explained by diffuse white matter pathology and neuronal loss, shown as symmetric high-intensity on brain MR T2-weighted images in the periventricular cerebral white matter as well as diffuse atrophy. White matter pathology may result from the disproportionate incorporation of cholesterol into the glial cell membrane and alterations in myelin lipid composition (22, 23). Also, intracerebral lipid deposition associated with xanthomas and local inflammatory responses can damage myelinated axons, gray matter formation, neuronal cell bodies, and neuronal integrity (19, 24), leading to neuronal loss and deterioration in behavior and cognition.

Several differential diagnoses should be considered when assessing patients with xanthomas and symmetric lesions in the dentate nuclei of the cerebellum. Tendonous xanthomas need to be differentiated from other hereditary diseases, such as familial hypercholesterolemia and sitosterolemia (1). Familial hypercholesterolemia, the most common cause of tendon xanthomas, is an autosomal dominant disorder that leads to increased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, but with normal cholestanol levels (25). While familial hypercholesterolemia usually manifests as intertriginous xanthomas in children, sitosterolemia and CTX manifest as tendonous xanthomas in adults (1, 26). Sitosterolemia can be differentiated from CTX by the absence of neurological symptoms and premature cataracts (27). Furthermore, hyperintensities of dentate nuclei on MRI should be differentiated from other diseases, including metronidazole toxicity, lead poisoning, maple syrup urine disease, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy caused by the JC virus (28). These disorders manifest as acute encephalopathy rather than the insidious onset seen in CTX. Thus, if progressive bvFTD symptoms appear in adults with xanthoma or a characteristic appearance of dentate in MRI, the possibility of CTX should be considered; the serum cholestanol and 7α,12α-dihydroxycholest-4-en-3-one levels should be further evaluated, and mutations in the CYP27A1 gene (1) should be searched for.

In addition, the patient showed abnormalities in SSEP and VEP, which supports the diagnosis of CTX (1, 29–31). Our patient was also revealed to have osteoporosis and ocular abnormalities, which are widely described as common manifestations in CTX patients (1, 32, 33).

Our patient was confirmed to have CTX based on biochemical and genetic tests. Biochemical tests showed increased levels of cholestanol and 7α,12α-dihydroxycholest-4-en-3-one, which is a highly sensitive metabolic biomarker of CTX (34). Genetic tests identified an LPV (c.1001T>A, p.Met334Lys) and a PV (c.1420C>T, p.Arg474Trp) in the CYP27A1 gene in trans. The variant c.1420C>T (p.Arg474Trp) has been found in several CTX patients as homozygous or compound heterozygous (13–18) and classified as pathogenic in ClinVar (accession number: VCV000004259.12). Although c.1001T>A (p.Met334Lys) has not been reported as a cause of CTX, we suggest the variant is likely pathogenic based on the following evidence: (i) The p.Met334Lys is located in a chemical substrate binding site in the P450 domain, which is a critical and well-established functional domain. In particular, the region from the 330th to the 345th amino acid is clustered by the binding site without any known benign variant (PM1). (ii) The p.Met334Lys is absent in the population database (gnomAD, https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/, accessed on 27, Jan.2023) (PM2). (iii) The p.Met334Lys was located in trans with the PV, c.1420C>T (PM3), and the patient's phenotype and biochemical test results were highly specific for CTX (PP4). Therefore, we classified the variant as likely pathogenic with three moderate evidences of pathogenicity.

In conclusion, CTX is an underdiagnosed disease, and the phenotype is often incomplete. Progressive dementia can be the only neuropsychiatric sign associated with CTX (21). Early recognition and intervention of CTX are important because treatment with chenodeoxycholic acid reverses metabolic abnormalities and prevents or ameliorates nervous system dysfunction. Therefore, we suggest that the diagnosis of CTX should be considered in patients with progressive dementia and xanthoma, even in the absence of premature CTX symptoms.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of ethical and privacy restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional review board of Samsung Medical Center. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

MC interpreted the patient data regarding cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis disease and was a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. E-JK, SM, N-YJ, and SL collected data and helped to draft the manuscript. NH, SS, and HJ reviewed the patient data and manuscript. Y-LS performed a pathological examination of the skin. J-HJ and Y-EK performed the genetic analysis of the patient and the next of kin and interpreted the results. HK supervised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the “National Institute of Health” research project (project No. 2021-ER1003-01 and 2021-ER1004-01); the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (NRF-2022R1A2C2092346); and the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, for the design of the study and interpretation of data and the ICT Creative Consilience program (IITP-2023-2020-0-01821) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation) for the collection and analysis of data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Nie S, Chen G, Cao X, Zhang Y. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: a comprehensive review of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2014) 9:179. 10.1186/s13023-014-0179-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorkhem I, Fausa O, Hopen G, Oftebro H, Pedersen JI, Skrede S, et al. Role of the 26-hydroxylase in the biosynthesis of bile acids in the normal state and in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. An in vivo study. J Clin Invest. (1983) 71:142–8. 10.1172/JCI110742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JS, Lee SS, Lee KW, Lee SB, Myung HJ, Chi JG, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis–A case report of two siblings. Seoul J Med. (1988) 29:83–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Lew M, Kim SJ. A Case of preeumect Cerebrotedinous Xanthomatosis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. (1988) 29:775–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee WK, Yoon BJ. A case of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. (1988) 29:783–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park CI, Kim YC, Shin JC, Kim YW, Lim KB. A case of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Ann Rehabil Med. (1998) 22:460–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung SJ, Kim HT. A case of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Korean Neurol Assoc. (2000) 18:94–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SW, Choi EH, Ahan SK. A case of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Korean J Dermatol. (2002) 40:1261–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh S, Kim HK, Park HD, Ki CS, Kim MY, Jin SM, et al. Three siblings with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: a novel mutation in the CYP27A1 gene. Eur J Med Genet. (2012) 55:71–4. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo S, Kim S, Bae DW, Park IS, Kim JS, Lee KS, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with spinal cord syndrome. J Korean Neurol Assoc. (2014) 32:215–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn SJIHBR. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery. Incheon: Human Brain Research & Consulting Co. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rascovsky, K., Hodges J. R., Knopman D., Mendez M. F., Kramer J. H., Neuhaus J., et al. L. (2011). Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134, 2456–2477. 10.1093/brain/awr179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KS, Kubota S, Kuriyama M, Fujiyama J, Bjorkhem I, Eggertsen G, et al. Identification of new mutations in sterol 27-hydroxylase gene in Japanese patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX). J Lipid Res. (1994) 35:1031–9. 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)40096-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakamatsu N, Hayashi M, Kawai H, Kondo H, Gotoda Y, Nishida Y, et al. Mutations producing premature termination of translation and an amino acid substitution in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene cause cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis associated with parkinsonism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1999) 67:195–8. 10.1136/jnnp.67.2.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rystedt E, Olin M, Seyama Y, Buchmann M, Berstad A, Eggertsen G, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: molecular characterization of two Scandinavian sisters. J Intern Med. (2002) 252:259–64. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Yuan Y, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Feng L. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with a compound heterozygote mutation and severe polyneuropathy. Neuropathology. (2007) 27:62–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koyama S, Kawanami T, Tanji H, Arawaka S, Wada M, Saito N, et al. A case of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis presenting with epilepsy as an initial symptom with a novel V413D mutation in the CYP27A1 gene. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2012) 114:1021–3. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekijima Y, Koyama S, Yoshinaga T, Koinuma M, Inaba Y. Nationwide survey on cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Japan. J Hum Genet. (2018) 63:271–80. 10.1038/s10038-017-0389-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verrips A, Hoefsloot LH, Steenbergen GC, Theelen JP, Wevers RA, Gabreels FJ, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic characteristics of patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Brain 123 (Pt 5). (2000) 908–19. 10.1093/brain/123.5.908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugama S, Kimura A, Chen W, Kubota S, Seyama Y, Taira N, et al. Frontal lobe dementia with abnormal cholesterol metabolism and heterozygous mutation in sterol 27-hydroxylase gene (CYP27). J Inherit Metab Dis. (2001) 24:379–92. 10.1023/A:1010564920930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyant-Marechal L, Verrips A, Girard C, Wevers RA, Zijlstra F, Sistermans E, et al. Unusual cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with fronto-temporal dementia phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 139A. (2005) 114–7. 10.1002/ajmg.a.30797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanrietvelde F, Lemmerling M, Mespreuve M, Crevits L, Reuck De, Kunnen J, et al. MRI of the brain in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (van Bogaert-Scherer-Epstein disease). Eur Radiol. (2000) 10:576–8. 10.1007/s003300050964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang CC, Lui CC, Wang JJ, Huang SH, Lu CH, Chen C, et al. Multi-parametric neuroimaging evaluation of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and its correlation with neuropsychological presentations. BMC Neurol. (2010) 10:59. 10.1186/1471-2377-10-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraidakis MJ. Psychiatric manifestations in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Transl Psychiatry. (2013) 3:e302. 10.1038/tp.2013.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koopal C, Visseren FL, Marais AD, Westerink J, Spiering W. Tendon xanthomas: not always familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. (2016) 10:1262–5. 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz PD, Jr, East C, Bergstresser PR. Dermal, subcutaneous, and tendon xanthomas: diagnostic markers for specific lipoprotein disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. (1988) 19:95–111. 10.1016/S0190-9622(88)70157-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kidambi S, Patel SB. Sitosterolaemia: pathophysiology, clinical presentation and laboratory diagnosis. J Clin Pathol. (2008) 61:588–94. 10.1136/jcp.2007.049775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bond KM, Brinjikji W, Eckel LJ, Kallmes DF, Mcdonald RJ, Carr CM, et al. Dentate update: imaging features of entities that affect the dentate nucleus. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2017) 38:1467–74. 10.3174/ajnr.A5138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mondelli M, Rossi A, Scarpini C, Dotti MT, Federico A. Evoked potentials in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and effect induced by chenodeoxycholic acid. Arch Neurol. (1992) 49:469–75. 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530290051011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilo-De-La-Fuente B, Jimenez-Escrig A, Lorenzo J, Pardo J, Arias M, Ares-Luque A, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Spain: clinical, prognostic, and genetic survey. Eur J Neurol. (2011) 18:1203–11. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginanneschi F, Mignarri A, Mondelli M, Gallus G, Del Puppo M, Giorgi S, et al. Polyneuropathy in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and response to treatment with chenodeoxycholic acid. J Neurol. (2013) 260:268–74. 10.1007/s00415-012-6630-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuriyama M, Fujiyama J, Kubota R, Nakagawa M, Osame M. Osteoporosis and increased bone fractures in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Metabolism. (1993) 42:1497–8. 10.1016/0026-0495(93)90205-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Federico A, Dotti MT. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: clinical manifestations, diagnostic criteria, pathogenesis, and therapy. J Child Neurol. (2003) 18:633–8. 10.1177/08830738030180091001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoflinger P, Hauser S, Yutuc E, Hengel H, Griffiths L, Radelfahr F, et al. Metabolic profiling in serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain of patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Lipid Res. (2021) 62:100078. 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of ethical and privacy restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.