ABSTRACT

Antibiotic tolerance, the ability of bacteria to sustain viability in the presence of typically bactericidal antibiotics for extended time periods, is an understudied contributor to treatment failure. The Gram-negative pathogen Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, becomes highly tolerant to β-lactam antibiotics (penicillin and related compounds) in a process requiring the two-component system VxrAB. VxrAB is induced by exposure to cell wall damaging conditions, which results in the differential regulation of >100 genes. While the effectors of VxrAB are relatively well known, VxrAB environment-sensing and activation mechanisms remain a mystery. Here, we used transposon mutagenesis to screen for mutants that spontaneously upregulate VxrAB signaling. This screen was answered by genes known to be required for proper cell envelope homeostasis, validating the approach. Unexpectedly, we also uncovered a new connection between central carbon metabolism and antibiotic tolerance in Vibrio cholerae. Inactivation of pgi (vc0374, coding for glucose-6-phosphate isomerase) resulted in an intracellular accumulation of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate, concomitant with a marked cell envelope defect, resulting in VxrAB induction. Deletion of pgi also increased sensitivity to β-lactams and conferred a growth defect on salt-free LB, phenotypes that could be suppressed by deleting sugar uptake systems and by supplementing cell wall precursors in the growth medium. Our data suggest an important connection between central metabolism and cell envelope integrity and highlight a potential new target for developing novel antimicrobial agents.

IMPORTANCE Antibiotic tolerance (the ability to survive exposure to antibiotics) is a stepping stone toward antibiotic resistance (the ability to grow in the presence of antibiotics), an increasingly common cause of antibiotic treatment failure. The mechanisms promoting tolerance are poorly understood. Here, we identified central carbon metabolism as a key contributor to antibiotic tolerance and resistance. A strain with a mutation in a sugar utilization pathway accumulates metabolites that likely shut down the synthesis of cell wall precursors, which weakens the cell wall and thus increases susceptibility to cell wall-active drugs. Our results illuminate the connection between central carbon metabolism and cell wall homeostasis in V. cholerae and suggest that interfering with metabolism may be a fruitful future strategy for the development of antibiotic adjuvants.

KEYWORDS: antibiotic tolerance, glycolysis, pgi, cell wall stress, VxrAB

INTRODUCTION

Antibiotic treatment failure is increasingly common in health care settings. Antibiotic resistance, the ability of bacteria to grow in the presence of antibiotics, is a major contributor to treatment failure and poses a well-recognized, massive threat to public health. Antibiotic tolerance, which is the prolonged survival of bacteria after antibiotic exposure (1), has also been linked to treatment failure (2) and the development of antibiotic resistance (2–5). Lastly, intrinsic resistance, i.e., the ability to grow in the presence of low concentrations of antibiotic by means of intrinsic diffusion barriers, target availability, and damage repair functions (sometimes in addition to well-defined resistance factors), likely also contributes to the decreased effectiveness of antibiotics in the clinical setting (6).

While the mechanisms of frank antibiotic resistance are well understood, the mechanisms of tolerance and intrinsic resistance remain understudied, preventing us from gaining a more comprehensive insight into the causes of antibiotic treatment failure. Many Gram-negative clinical pathogens are tolerant to antibiotics that target the bacterial cell wall, for example, the ordinarily bactericidal β-lactam antibiotics (7). β-Lactams inhibit cell wall synthesis, which in susceptible bacteria usually results in degradation of the essential cell wall via the activity of endogenous lytic enzymes, called autolysins (8). The cell wall consists mostly of peptidoglycan (PG), a complex macromolecule that comprises alternating sugars cross-linked by short peptide chains. This structure normally provides protection against an osmotically variant environment and governs bacterial shape (9). Defying the essentiality of PG, tolerant Gram-negative pathogens survive cell wall degradation induced by antibiotics and assume a nonreplicating spheroplast form that readily reverts to normal growth upon removal of the antibiotic (7, 10–12).

Vibrio cholerae is a particularly tolerant enteric pathogen that exhibits high survival upon antibiotic-mediated cell wall degradation, essentially rendering β-lactam antibiotics bacteriostatic agents (11). V. cholerae’s tolerance is governed by the VxrAB two-component system (also known as WigKR) (13, 14). Once activated, the inner membrane-localized histidine kinase VxrA phosphorylates the cytosolic VxrB, a transcription factor that alters expression of a large regulon, contributing to the tolerance phenotype. Specifically, upon signal recognition, VxrAB downregulates genes involved in iron acquisition (15) and cell shape (16) while upregulating genes involved in peptidoglycan synthesis (15), biofilm formation and motility (17), and type VI secretion (13). The downstream effectors of this system are well characterized; however, what activates VxrA remains poorly understood. A homologous system in the related bacterium Vibrio parahaemolyticus has been proposed to bind β-lactams directly (18, 19), but strong evidence for this is lacking (20, 21). In addition, it is unlikely that β-lactams are the only activators of VxrAB; other structurally distinct antibiotics, overactive cell wall degradation enzymes, and mechanical stress also activate the system (14, 22). With numerous contributors to VxrA induction, we sought to uncover genetic pathways promoting activation of VxrAB to find genes involved in general cell wall homeostasis. In addition to known or expected factors, we found that a disruption in the gene coding for the glycolysis enzyme glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (vc0374, pgi) causes strong cell wall defects concomitant with reduced tolerance and diminished intrinsic resistance. Our data showcase a novel connection between glycolysis and cell envelope turnover in the cholera pathogen and open the door for the future development of novel antimicrobial agents that potentiate β-lactam antibiotics by interfering with central carbon metabolism.

RESULTS

A screen for induction of the VxrAB regulon identifies expected and novel cell envelope maintenance factors.

To identify cell envelope maintenance factors in V. cholerae on a genome-wide scale, we screened for transposon-mediated mutational activation of VxrAB using our previously validated VxrAB-responsive promoters PvxrAB-lacZ and Pvca0140-lacZ (Fig. 1A) on plates containing the chromogenic LacZ substrate X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). Putative VxrAB activator Tn insertion mutants were then identified by mapping the transposon insertion sites via arbitrary PCR (see Materials and Methods for details). The first round (2 biological replicates of mutagenized cultures) yielded mostly hits in genes with known roles in cell envelope maintenance (ldcV, coding for a cytoplasmic l,d carboxypeptidase [23]; vca0040, a putative undecaprenol phosphate translocase [24, 25]; and the main penicillin-binding protein, PBP1a, with its activators LpoA and CsiV [26]), internally validating our screen.

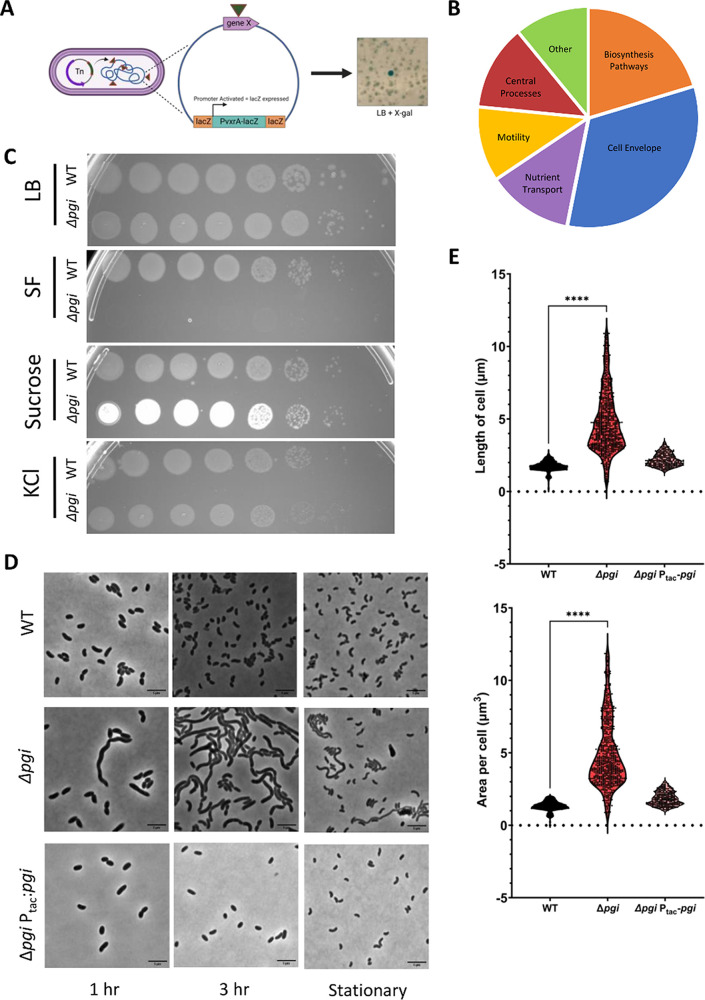

FIG 1.

A transposon screen reveals severe cell envelope defects in a pgi mutant. (A) Schematic depicting the transposon screen strategy. (B) Pie chart of the pathways that answered the screen and their respective distribution of hits. (C) Overnight cultures of the indicated strains were serially diluted and spotted on LB, SF, SF–180 mM sucrose, and SF–200 mM KCl. (D) The indicated strains were diluted 100-fold into fresh LB and then imaged on an agarose pad after 1 and 3 h of growth. Stationary-growth-phase cultures were also imaged. Bar = 5 μm. (E) Area and length were quantified at 3 h of growth with MicrobeJ. n > 250 individual cells. Welch’s t test was conducted. ****, P < 0.0001.

We reasoned that the large number of mutants in PBP1a, LpoA, and CsiV might have obscured screen saturation. We thus repeated the screen in the presence of 10 mM d-methionine (which specifically inhibits growth of mutants with mutations in the PBP1a pathway: pbp1a, lpoA, and csiV [27]). This modified screen yielded additional hits, including the gluconeogenesis pathway gene vc2544 (coding for fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase) and the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis gene pgi, coding for glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (vc0374). For a full list of genes, see Table S1 in the supplemental material. Additionally, many other pathways answered the screen (Fig. 1B), providing new leads for future work. We validated all hits by plating on X-Gal after single-colony purification. Interestingly, we qualitatively noticed that VxrAB background levels appeared elevated in all colonies after conjugational transfer of the transposon shuttle vector. This possibly reflected conjugation-induced cell envelope damage inflicted by the donor strain’s type IV secretion system (28), resulting in a high number of false positives. To prioritize informative genes further, we thus included growth on salt-free LB (SF), a condition expected to affect the viability of some mutants with cell envelope defects (29, 30), as a validation step. This additional step narrowed down several mutants that exhibited subtle growth defects in SF, but one mutant in particular, with a transposon insertion in vc0374 (pgi), had a severe growth defect on both solid and liquid SF but not standard LB (Fig. S1A). The transposon mutant in the other glucose metabolism gene that answered the screen, vc2544 similarly exhibited a slight morphology defect (albeit in stationary phase) and a subtle growth defect in liquid SF (Fig. S1A and B); however, the pgi defects were more severe. A connection between mutations in glycolysis and cell envelope defects had not previously been reported in V. cholerae, and we thus decided to focus on the pgi mutant for further analysis.

A pgi mutant exhibits a pronounced cell envelope defect.

To validate our transposon screen, we first constructed a clean Δpgi mutant and tested it for growth and cell envelope defects. Consistent with our screen and validation results, the Δpgi strain did not exhibit a growth defect in LB but did show a severe growth defect in SF, both on plates (Fig. 1C) and in liquid medium (Fig. S2A and B). The defect on SF medium could be fully complemented by inducible expression of pgi, excluding the possibility of polar effects. To explore if the SF defect was due to reduced osmolarity or instead was specific to the absence of sodium, we plated serial dilutions of a pgi mutant culture on SF supplemented with KCl (200 mM) or sucrose (180 mM). Both adjustments restored growth of the Δpgi mutant (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the growth defect is indeed due to low osmolarity. Next, we imaged Δpgi mutant cells grown in LB during stationary phase and exponential phase using phase microscopy. We noted striking morphological defects in the Δpgi mutant, including cell elongation and growth (indicative of a division defect) (Fig. 1D); these defects were more pronounced during rapid exponential growth and partially resolved during stationary phase. Cell area and length were calculated using ImageJ and significantly differed between the wild type (WT) and the Δpgi mutant (Fig. 1E). These results support the idea that the Δpgi mutation causes defects in cell envelope homeostasis.

The pgi mutant exhibits reduced tolerance and resistance to cell wall-acting antibiotics.

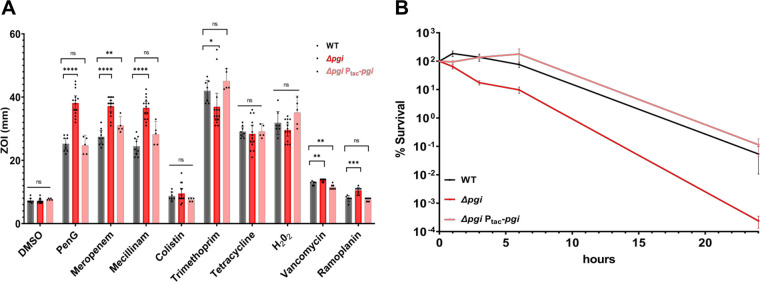

We reasoned that the pgi mutant’s cell wall defect might enhance susceptibility to cell wall-acting antibiotics; indeed, pgi previously answered our TnSeq screen for tolerance defects in V. cholerae (10). We next performed a zone-of-inhibition (ZOI) assay using a panel of antibiotics, to further parse this out. Consistent with its cell wall defect, the Δpgi mutant was significantly (P < 0.0001 using Welch’s t test) more sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin G (PenG), meropenem, and mecillinam, while exhibiting little to no sensitivity differences to antimicrobials with other mechanisms of action, i.e., hydrogen peroxide, colistin, and tetracycline (Fig. 2A). Susceptibility to antibiotics that are typically excluded from Gram-negative bacteria by the outer membrane permeability barrier (vancomycin and ramoplanin) was also slightly but significantly increased in the pgi mutant, suggesting increased outer membrane damage (31, 32). As a side note, we also observed a slight increase in trimethoprim resistance in the pgi mutant background, but the biological significance of this observation is unclear.

FIG 2.

A pgi mutant exhibits decreased tolerance and reduced resistance to cell wall-active antibiotics. (A) ZOI measurements from a disk diffusion experiment on LB agar. Concentrations of the noted antibiotics are listed in Materials and Methods. Data represent at least 5 independent biological replicates; raw data points are shown with bars indicating 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was assessed via Welch’s t test. ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (B) Time-dependent killing experiment. Bacteria were grown to exponential phase and then treated with 100 μg/mL PenG (10× MIC). At the indicated time points, serial dilutions were plated on LB and grown overnight at 30°C. Data represent the means and standard errors for 6 independent biological replicates.

To next test the pgi mutant’s effect on antibiotic tolerance, we conducted a time-dependent killing experiment using PenG (100 μg/mL, 10× MIC). While viability of the WT strain decreased only slightly during the experiment, consistent with our previous observations (10), the Δpgi mutant exhibited a dramatic, 10,000-fold drop in survival over the course of 24 h (Fig. 2B). Collectively, our data suggest that pgi plays a central role in intrinsic resistance and tolerance against cell wall-acting antibiotics.

Suppressor mutations in sugar transport system components restore Δpgi defects.

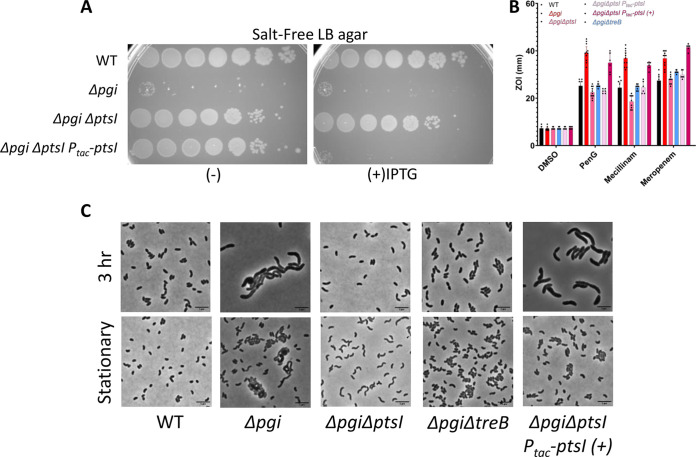

While conducting the above-mentioned plating and kinetic experiments in SF medium, we noticed a high frequency of spontaneous suppressor mutants arising in the Δpgi background. With the goal of gaining more mechanistic insight into pgi’s role in cell wall homeostasis, we purified these mutants to study their effects. Whole-genome sequencing revealed a similar set of suppressors in 3 independent rounds of selection. Of the 67 suppressors we isolated and subjected to whole-genome sequencing, 52 mapped to the ptsI gene (vc0965), coding for the first protein in the phosphate relay system, which ultimately effects sugar phosphorylation during phosphotransferase-mediated uptake. The remaining suppressors mapped to another component of the phosphotransferase system (PTS), vc0964 (crr, coding for the EIIA component), treB (vc0910, encoding the trehalose import EIIB component), and two genes involved in maltose transport, vca0944 and vca0011 (Table S2) (33). Our initial validation revealed that these mutations at least partially suppressed all phenotypes associated with the pgi mutation, i.e., the SF growth defect, morphological defects upon culturing in LB, and antibiotic sensitivity phenotypes, despite selection in SF only (Fig. S3A to C).

The identity of suppressor mutations implied likely loss of function. To validate suppression of the Δpgi strain phenotypes, we constructed clean deletions strains in the WT and the Δpgi backgrounds, focusing on ptsI and treB. These mutations indeed restored viability of the Δpgi strain to various degrees. Deletion mutants and complementation strains in ptsI completely rescued the Δpgi SF sensitivity phenotype and morphological defects (Fig. 3A to C), while Δpgi strain promoted partial restoration of morphology and cell viability, with complete restoration of intrinsic resistance, as measured by ZOI assay (Fig. 3B and C). Consistent with previous work in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica (34), our suppressor analysis thus overwhelmingly suggests that the pgi mutant suffers from sugar phosphate toxicity, which can be mitigated by curbing sugar uptake.

FIG 3.

Mutants in sugar uptake systems suppress Δpgi mutant cell envelope defects. (A) The indicated mutant strains carrying IPTG-inducible complementation constructs were serially diluted and plated on SF agar with or without IPTG. (B) ZOI measurements from a disk diffusion experiment conducted on LB agar. Data represent 6 independent biological replicates; raw data points are shown. (C) The indicated mutant strains were imaged after growth in exponential phase in LB. +, IPTG inducer. Bar = 5 μm.

Untargeted metabolomics reveal accumulation of glycolysis intermediates in the pgi mutant.

We next sought to determine the specific compound that may cause the observed Δpgi defects. To examine the metabolite differences in the pgi mutant versus the WT, we conducted untargeted metabolomics analyses of both strains during their exponential growth in LB, where the mutant exhibited the most dramatic phenotype. Using both positive and negative hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) to probe both central metabolism and cell envelope precursors based on their surface charges, over 800 metabolites appeared altered between the WT and the Δpgi mutant (Fig. S4) (see Materials and Methods for details of analysis). Multivariate analysis was done, and principal-component analysis (PCA) showed a clear differentiation between WT and the Δpgi groups. Metabolites with roles in glycolysis, like β-d-fructose-6-phosphate (6-o-phosphono hex-2-xylofuranose) and glucose-6-phosphate, were dramatically (53- and 236-fold, respectively) increased in the pgi mutant. These results are partially consistent with those obtained with pgi mutants in E. coli and other Gram-negative species grown in the presence of glucose, where an accumulation of glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) was likewise observed (34). The accumulation of both G6P and fructose 6-phosphate (F6P) suggests that both sugar import (indicated by the accumulation of G6P) and gluconeogenesis (accumulation of F6P) are active during growth in LB medium.

Alternatively to gluconeogenesis, the F6P accumulation could be due to enhanced flux into the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (similar to the E. coli pgi mutant [35]). While metabolomics did not reveal any typical PPP intermediates, enhanced metabolic flux into the PPP can in principle result in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (35), which in turn might affect the viability of the Δpgi mutant on salt-free LB. To test this, we plated the pgi mutant on SF plates containing catalase (which restored growth to a ΔoyxR ΔkatB ΔkatG hypersensitive mutant as a positive control for effective catalase activity in our plate assay [Fig. S5]). Catalase did not restore growth to the Δpgi mutant, suggesting that at least hydrogen peroxide production does not contribute to the mutant’s cell wall defect.

The accumulation of G6P was surprising, as LB medium does not contain any added glucose and has a very low fermentable-sugar content (36). To test if LB contains residual glucose, we used a glucose quantification kit to assess glucose levels in our LB medium. Surprisingly, we found that this medium does contain significant amounts of glucose (3 μg/mL) (Fig. S6B), likely explaining the pgi mutant’s phenotypes. However, our suppressor screen was also answered by treB, coding for a component of the trehalose uptake PTS. This could either indicate TreB’s moonlighting ability to also import glucose (or another sugar that can be converted to G6P) or suggest the presence of trehalose in LB. Trehalose can be imported by V. cholerae and converted to glucose-6-phosphate by the hydrolase TreC (37). Residual yeast-derived trehalose in LB could in principle contribute to glucose accumulation in the pgi mutant, and this would be consistent with TreB answering our Δpgi SF suppressor screen (Fig. 3). To explore this possibility further, we first plated the pgi mutant on M9 minimal medium (MM) with 0.1% Casamino Acids and SF plates containing trehalose. Similar to the results on glucose plates, the Δpgi mutant failed to grow on trehalose, and this could be partially suppressed by deletion of treB, raising the possibility that trehalose might contribute to Δpgi mutant phenotypes (Fig. S6A). However, direct quantification of trehalose using a commercial kit failed to reveal significant trehalose in LB, suggesting either concentrations below the limit of detection (0.1 to 8.0 μg/L) or indeed a lack of trehalose.

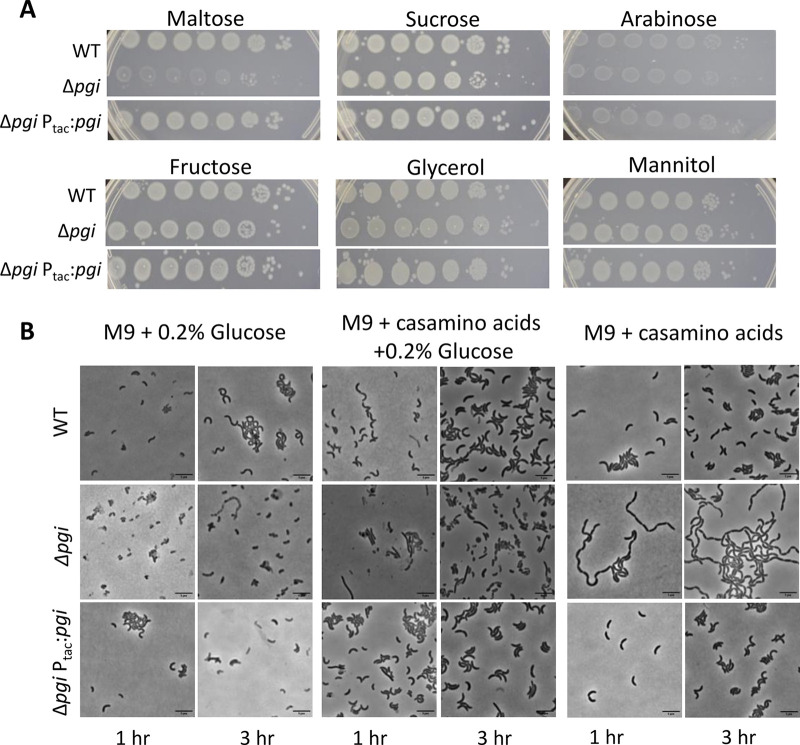

Glycolytic sugars inhibit pgi growth.

While there is indeed glucose in LB, G6P can be produced from diverse other sugars. Without pgi, the flow between gluconeogenesis and glycolysis, through the conversion of F6P and G6P, is halted. To dissect the putative contributions of G6P (predominantly produced via sugar uptake) versus F6P (likely produced predominantly via gluconeogenesis in the pgi mutant), we plated our pgi mutant on gluconeogenic versus glycolytic carbon sources. To achieve this, we supplemented MM agar either with Casamino Acids or with Casamino Acids with different sugars and tested viability (Fig. 4A). We noticed that carbon sources that can be converted to F6P through gluconeogenesis (Casamino Acids, fructose, mannitol, and glycerol) (34) did not cause a decrease in viability in the Δpgi mutant. In contrast, maltose, which can likely be converted to G6P through V. cholerae’s homologs of E. coli’s mal operon, caused a plating defect in the Δpgi background (Fig. 4A). These observations support our growing model that the toxicity we observed in a Δpgi background mutant stemmed from the accumulation of glucose. In addition to the plating defects described above, we also found that growth on glycolytic carbon sources (glucose and maltose) but not a gluconeogenic carbon source (Casamino Acids) caused severe growth rate defects (Fig. S7). Thus, G6P accumulation (or a metabolic product originating from G6P) likely causes the Δpgi defects.

FIG 4.

Glycolytic sugars induce toxicity in a Δpgi mutant. (A) Serial dilutions of the indicated strains were plated on M9 minimal media agar supplemented with either 0.1% Casamino Acids, 0.2% sugars, or both and grown overnight at 30°C. (B) The indicated strains were washed and diluted 50-fold in fresh growth medium with the indicated carbon sources and grown to exponential phase. The cells were then imaged on an agarose pad after 1 and 3 h of growth. Bar = 5 μm.

We previously showed that in LB, the pgi mutant has an enlarged and filamentous morphology. Our metabolomics results suggested that both gluconeogenesis and glycolysis are active during growth in LB, and we sought to dissect the contributions of each pathway to the morphology of the Δpgi mutant. To this end, we conducted microscopy using either 0.1% Casamino Acids (promoting gluconeogenesis), 0.2% glucose (glycolysis), or 0.1% Casamino Acids plus 0.2% glucose (both) to examine morphological defects. In medium containing only glucose, the cells stopped growing, concomitant with significant accumulation of cell debris (indicative of enhanced lysis) but with no striking morphological defects of remaining intact cells. The lack of growth matches our observations in the growth curve assays (Fig. S7). After growth in glucose with Casamino Acids, the cells exhibited a mixed morphology, with some cells becoming filamented, but also with spheroplast formation and mild chaining (Fig. 4B), similar to the phenotype in LB medium (Fig. 1D). Unexpectedly, in Casamino Acids, where F6P presumably accumulates, the cells exhibited a daughter cell separation defect (Fig. 4B), reminiscent of a mutant with a mutation in V. cholerae’s sole amidase, AmiB (30). Taken together, these data suggest that while glucose toxicity (likely due to G6P accumulation) inhibits growth of the Δpgi mutant, gluconeogenesis also contributes to morphological defects. We were particularly intrigued by the pgi mutant’s morphological similarity to a ΔamiB mutant and will explore the connection between central carbon metabolism and daughter cell separation in future work.

Glucose toxicity in the pgi mutant may contribute to reduced cell wall precursor synthesis.

Next, we asked how the accumulation of the glycolysis metabolites we measured in metabolomics may cause growth inhibition in the Δpgi strain. Glucose-6-phosphate accumulation is associated with cell wall stress in other bacteria and even fungi (38, 39). G6P can be converted to G1P by PgcA (also called pgm in E. coli); in Bacillus subtilis, G1P likely inhibits the cell wall precursor synthesis enzyme, GlmM (40), which converts glucosamine-6-phosphate (Gln6P) to glucosamine-1-phosphate (Gln1P), an important step in the synthesis of the essential PG precursor UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc). We hypothesized that a similar GlmM poisoning by, for example, G1P might at least partially explain the pgi mutant’s cell wall defects. According to our metabolomic data, the pgi mutant accumulates (albeit slightly) Gln6P, the natural substrate for GlmM, perhaps indeed suggesting reduced GlmM activity. High concentrations of sugar phosphates (G1P, as in B. subtilis, or G6P) might competitively inhibit GlmM activity (or another precursor synthesis enzyme) due to their structural similarity to the natural substrate Gln6P. Of note, it is difficult to distinguish G6P from G1P using metabolomics; it is formally possible that the pgi mutant exhibits an undetected G1P increase in addition to G6P.

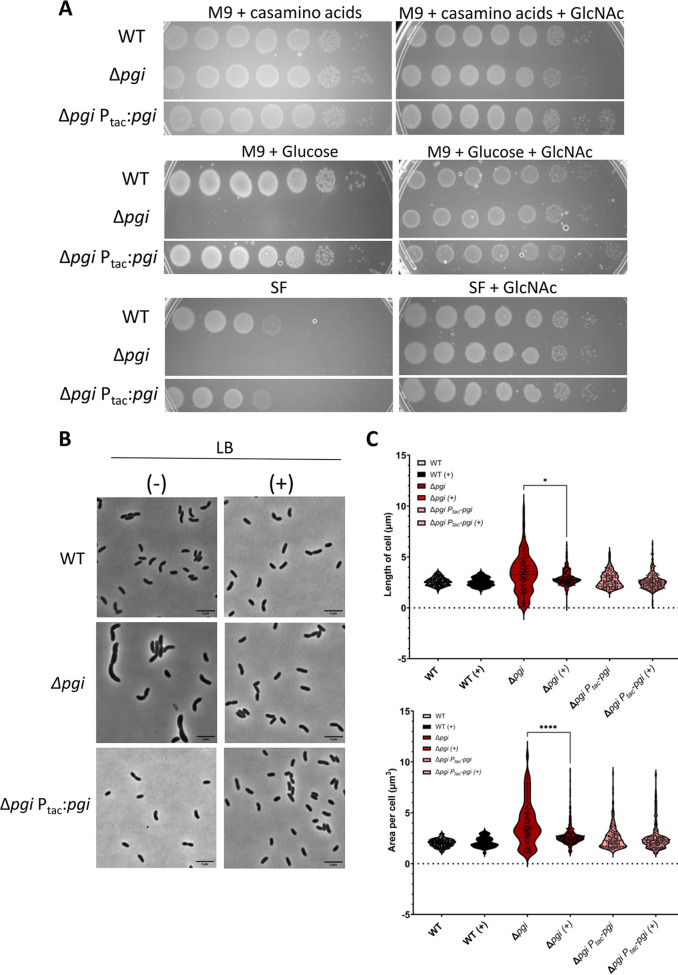

If there was indeed precursor limitation due to GlmM competitive inhibition, externally supplying Gln6P (GlmM’s natural substrate) might relieve this inhibition. V. cholerae lacks a direct importer for glucosamine but can convert external GlcNAc to Gln6P (33). We thus supplied the Δpgi mutant with GlcNAc, which in V. cholerae is imported via the NagE transporter and then converted to Gln6P via NagA (41, 42). Addition of GlcNAc to either SF or solid MM with 0.2% glucose (where the pgi mutant exhibited a drastic growth defect) indeed fully rescued growth (Fig. 5A), which is in line with an inherent reduction of PG precursor synthesis being at the heart of pgi mutant phenotypes. These results are also recapitulated in the morphology defects of the Δpgi mutant; LB supplementation with 0.2% GlcNAc completely restored WT morphology (Fig. 5B and C). Cell area and length were also calculated and showed that GlcNAc addition resulted in partial restoration of cell length but complete restoration of cell area (Fig. 5C). These data support our hypothesis that the lethal effect we observed in a pgi mutant is due to G6P accumulation interfering with cell wall synthesis.

FIG 5.

Supplementation with N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) suppresses Δpgi mutant phenotypes. (A) Serial dilutions of the indicated strains were plated on salt-free LB (SF) or M9 minimal media supplemented with Casamino Acids (0.2%) or glucose (0.2%), with or without the addition of 0.2% GlcNAc and grown overnight at 30°C. (B) The indicated strains were diluted 100-fold into fresh LB with (+) or without (−) 0.2% GlcNAc and then imaged on an agarose pad after 1 and 3 h of growth. Stationary-growth-phase cultures were also imaged. Bar = 5 μm. (C) Area and length were quantified after 3 h of growth in the presence and absence of 0.2% GlcNAc with MicrobeJ. n > 500 individual cells. Welch’s t test was conducted. *, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

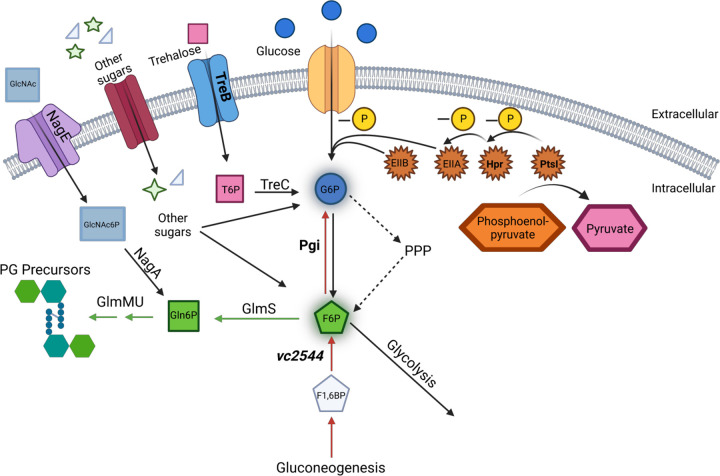

Herein, we present data demonstrating that disrupting glycolysis interferes with optimal cell wall homeostasis in Vibrio cholerae (Fig. 6). Deletion of a gene encoding a key enzyme in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, pgi, caused severe morphological defects and increased sensitivity to low osmolarity and cell wall-targeting antibiotics. Suppressors of this defect mapped to sugar uptake systems, with partial suppression afforded by inactivation of the trehalose uptake system. In addition, we found that the pgi mutant accumulates G6P and F6P during growth in LB, with indirect evidence that minimal G6P might also be derived from trehalose. While LB is generally considered a medium virtually devoid of sugars (and especially glucose) (36), our data demonstrate that there is in fact glucose in LB—caveat experimentator! (36)—and at least Vibrio cholerae might potentially either convert other components of this rich medium (e.g., trehalose and maltose) to glucose or produce sugars upstream of G6P production (e.g., trehalose) as metabolic by-products (which are later reimported) during growth in LB (though V. cholerae does not appear to carry trehalose biosynthesis pathway genes). Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that a ptsI mutation reduces the length of E. coli cells grown in LB broth, likewise suggesting a role for sugar uptake in cell division and/or elongation (43). These data seem to be in line with what we report here, both because they suggest that some glucose (or other glycolytic sugar) is available in LB broth and because they imply a connection between sugar metabolism and cell envelope homeostasis and cell growth.

FIG 6.

Overview model of central carbon metabolism and PG precursor synthesis. Extracellular glucose and trehalose can be taken up into the cell through PtsG and TreB, respectively. Trehalose is converted to trehalose-6P (T6P) by TreC. Glucose is phosphorylated via the PtsI/Hpr/EIIA(crr)/EIIB phosphorelay cascade, which is initiated by the phosphate transfer from PEP to PtsI (other sugars and their transporters potentially also contribute to the accumulation of G6P). Pgi converts G6P to F6P during glycolysis (black) and vice versa during gluconeogenesis (red). The PPP also contributes to the generation of F6P from G6P. F6P can be converted to Gln6P by GlmS and then further to cell wall precursors by GlmMU. Extracellular GlcNAc can be up taken and phosphorylated by NagE and the PTS to GlcNAc-6P. This is then converted to Gln6P by NagA. Genes answering the screen for VxrAB activation are in bold, and metabolites that increased in the pgi mutant are indicated by glow around the edges of the metabolite icon.

Our data shed new light on the emerging connection between central metabolism and cell wall homeostasis. Mutants disrupted in carbon flux have been extensively characterized in model organisms like E. coli and B. subtilis. In B. subtilis, for example, a checkpoint protein, encoded by cpgA, is impacted by glucose toxicity. When it is deleted, a cascading imbalance of metabolites contributes to accumulation of 6-phosphogluconate and subsequent shutdown of both the pentose phosphate pathway and glycolysis by simultaneous inhibition of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (GndA) and pgi, resulting, among other defects, in cell envelope damage (44). Also in B. subtilis, mutating pgi and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (i.e., this mutant is defective in both glycolysis and PPP) results in the accumulation of glucose-1-phosphate, which causes apparent cell wall synthesis inhibition and ultimately cell lysis (40). This was shown to be the consequence of conversion of G6P (accumulating in the double mutant) to G1P via PgcA; G1P subsequently inhibits an unknown step in PG precursor synthesis, likely GlmM (40). While our data do not reveal the exact mechanism of cell wall perturbations in the pgi mutant, a similar metabolic poisoning of GlmM or another precursor synthesis enzyme might be the culprit.

In principle, cell wall precursor synthesis might also be reduced in the pgi mutant due to its diminished ability to generate F6P, the critical branching point between glycolysis and PG precursor synthesis. However, our metabolomics revealed a substantial accumulation of F6P in the pgi mutant (53-fold compared to the WT), rather than a decrease, suggesting that either PPP or gluconeogenesis can efficiently generate F6P, and/or that the effective shuttling of F6P into PG precursor synthesis is blocked at the level of GlmS activity. Interestingly, growth in gluconeogenic carbon sources (amino acids) induced a chaining defect in the pgi mutant. Thus, the accumulation of F6P may interfere with the activity of the amidase AmiB, its activators, or lytic transglycosylases, another class of autolysins implicated in daughter cell separation (45). However, the large metabolic perturbations in the pgi mutant might also indirectly affect expression levels of these drivers of cell separation. Deciphering the exact mechanism of cell wall perturbations in the pgi mutant will be part of a future study.

Of note, a recent study reported high toxicity of arabinose in WT V. cholerae, especially during growth in gluconeogenic medium (M9 minimal media - Casamino Acids) (46). The phenotype of arabinose toxicity was cell wall degradation (mimicking exposure to β-lactam antibiotics) suggesting inhibition of cell wall synthesis by a metabolite in the arabinose degradation pathway. The mechanism of arabinose intoxication of cell wall synthesis is unknown (and likely distinct from the mechanisms observed here, based on phenotypic differences); arabinose also did not exacerbate growth defects in the Δpgi strain (Fig. 4A), but these data indicate multiple connections between carbon metabolism and cell wall homeostasis, at least in the cholera pathogen.

The division defect (filamentation) we observed in the pgi mutant might also indicate a dysfunctional sensor system (OpgH-FtsZ) that connects nutrient availability with cell division in E. coli (47, 48). However, V. cholerae lacks a key domain in the OpgH sensor (49), suggesting that this may not be the case. Nonetheless, the fact that apparent reduction in precursor synthesis results in a division defect (in addition to general cell envelope defects) is intriguing, since it suggests that division is more susceptible to changes in precursor availability than other growth processes.

Interestingly, our original screen was also answered by a mutant with a mutation in the gluconeogenesis enzyme fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase. This mutant had a more subtle phenotype than the pgi mutant, perhaps indicating that disruption of gluconeogenesis causes a decrease in F6P levels (which is only partially buffered by glycolysis using LB’s limited glucose or by F6P generation through the pentose phosphate pathway), and the associated decrease in PG precursor availability might be the underlying cause of this mutant’s cell wall defects.

Consistent with internal inhibition of cell wall synthesis, our data also demonstrate that G6P accumulation promotes increased susceptibility to cell wall acting antibiotics, reducing both intrinsic resistance and tolerance to cell wall-acting agents in the cholera pathogen. Our data thus add support to the emerging model that interfering with central metabolism is a promising strategy to potentiate antibiotics (50). Crucially, glycolysis flux as a modulator of cell wall homeostasis appears to be conserved from bacteria to fungi (38, 39), and it is thus an intriguing possibility that this may represent an ancient homeostatic feedback mechanism between the nutrient state of the cell and cell envelope integrity that could be exploited as a broad target for the development of antimicrobials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All V. cholerae strains used in this study are derivatives of V. cholerae El Tor strain N16961 (Table S3). V. cholerae was grown on Luria-Bertani (also called lysogeny broth) (LB) medium (for a 1-L bottle, 10 g casein peptone, 5 g yeast extract, 10 g NaCl, and 12 g agar; all premade from Fisher Bioreagents), in salt-free LB (for a 1-L bottle, 10 g Tryptone and 5 g yeast extract, with addition of 15 g agar for solid medium), or in M9 minimal medium with 0.1% Casamino Acids (for a 1-L bottle, 15 g agar and 200 mL 5× M9 salts [for a 1-L bottle, 35 g Na2HPO4·7H2O, 15 g KH2PO4, 2.5 g NaCl, 5 g NH4Cl], 10 mL 20% Casamino Acids [vol/vol], 0.5 mL 1 M MgSO4, 0.1 mL 1 M CaCl2, and 1 mL FeCl3/citric acid) at 30°C unless otherwise indicated; 200 μg/mL of streptomycin was also added (N16961 is streptomycin resistant). Where applicable, growth media were supplemented with 0.2% (vol/vol) glucose, 0.2% (vol/vol) trehalose, or 0.2% (vol/vol) GlcNAc. For growth experiments, overnight cultures were diluted 500-fold into 1 mL designated growth medium containing streptomycin and incubated in 100-well honeycomb wells in a Bioscreen growth plate reader (Growth Curves America) at 37°C with random shaking at maximum amplitude, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was recorded at 10-min intervals.

Plasmid and strain construction.

Oligonucleotides used in this study are summarized in Table S4. E. coli DH5α λpir was used for general cloning, while E. coli MFDλpir (a diaminopimelic acid [DAP] auxotroph) or SM10 λpir was used for conjugation into V. cholerae (51). Plasmids were constructed using Gibson assembly (52). All plasmids were Sanger sequence verified. The transcriptional fusion plasmid pAW61 was used to create the PvxrAB-lacZ and Pvca0140-lacZ reporter strains. To this end, 500-bp regions upstream of the genes vca0565 (vxrA) and vca0140 were amplified from N16961 genomic DNA by PCR and cloned into the pAW61 vector, a suicide plasmid containing E. coli lacZ downstream of a multiple cloning site, flanked by V. cholerae lacZ upstream and downstream sequences, as well as the sacB marker for counterselection. pAW61 was then used to deliver the reporter construct into the V. cholerae chromosome, replacing native lacZ with the promoter-lacZ fusion. Conjugation of pAW61 into V. cholerae was performed by mixing overnight cultures 1:1 (100 μL donor plus 100 μL recipient) in 800 μL fresh LB, followed by pelleting (7,000 rpm, 2 min) and resuspending in 100 μL LB. The mixture was then spotted onto LB agar (with 600 μM DAP for E. coli MFDλpir growth) and incubated for 4 h (overnight for pTOX5 deletions) at 37°C. Selection for single-crossover mutants was then achieved by streaking the mating mixture on streptomycin (200 μg/mL) plus carbenicillin (100 μg/mL) in the absence of DAP. Deletion mutants were then obtained by counterselection on salt-free LB plus 10% sucrose (vol/vol) (to inhibit growth of sacB+ single crossover mutants). Mutants were then verified by colony PCR using primers 41 (AIW567) and 8 (MKchromolacZ rev) (Table S2).

Gene deletions were constructed using the pTOX5 cmR/msqR allelic exchange system (53). In short, 500-bp regions flanking the gene to be deleted were amplified from N16961 genomic DNA by PCR, cloned into the suicide vector pTOX5, and conjugated into V. cholerae. The first round of selection after mating on LB–DAP–1% glucose (vol/vol) was performed on LB–chloramphenicol (5 μg/mL)–streptomycin–1% (vol/vol) glucose at 30°C. Chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were picked into Eppendorf tubes with 1 mL LB–1% glucose, incubated at 37°C without agitation for 3 h, pelleted (7,000 rpm for 2 min), and counterselected on M9 minimal media containing 2% (vol/vol) rhamnose at 30°C. Deletions were verified by PCR. Since the pgi mutation confers glucose sensitivity, we created mutants in this background without glucose supplementation and then verified plasmid loss with patch plating with and without chloramphenicol. Successful knockouts were then verified using flanking and internal primers, respectively, and verified with whole-genome sequencing.

Complementation strains were created using the chromosomal integration plasmid pTD101, a derivative of pJL1 (54) containing lacIq and a multiple-cloning site under the control of the IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible Ptac promoter. pTD101 integrates into the native V. cholerae lacZ (vc2338) locus. Genes for complementation experiments were amplified from N16961 genomic DNA, introducing a strong consensus ribosome-binding site (RBS) (AGGAGA), and cloned into pTD101 using Gibson assembly. pTD101 was integrated into the V. cholerae chromosome as described above for pAW61 and colony PCR verified using primers 5 and 8.

Transposon mutagenesis.

Overnight cultures of PvxrAB-lacZ and Pvca0140-lacZ strains and E. coli SM10 carrying the mariner transposon delivery plasmid pSC189 (55) were washed, conjugated in equal volumes, and spotted onto 45-μm filter discs placed on LB plates. These were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, resuspended in 2 mL of LB, plated onto large LB–X-Gal–kanamycin (50 μg/mL)–streptomycin (200 μg/mL) plates, and grown overnight at 37°C. Blue colonies (“vxrAB on”) were picked and purified on the same medium overnight at 30°C. Single colonies were then picked and resuspended in a 96-well plate with 100 μL LB-streptomycin. Arbitrary PCR was conducted using ARB 1, ARB 2, Himarout, and H1 primers (Table S2). The first PCR utilized ARB1 and Himarout, adding external oligonucleotides to the transposon-specific sequences. A 1.5-μL portion of PCR product was added to the mixture for PCR 2, where H1 and Arb2 were used to make internal complementary sequences. Transposon–genomic-DNA junctions were identified using Sanger sequencing with H1 primers followed by nucleotide BLAST. Hit annotations are those found in the KEGG database.

Cell viability assay.

To test cell viability, overnight cultures were added to sterile 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for serial dilution from 1:10 to 1:107. Five microliters of overnight cultures and diluted cultures was spotted for determination of CFU per milliliter on different medium plates, as described in the figure legends. Dried plates were then incubated at 30°C overnight, and colonies were counted the next day. For time-dependent killing experiments, overnight cultures of wild-type and mutant strains were diluted 1:100, grown in LB medium at 37°C for 1.5 h, and supplemented with 100 μg/mL PenG and continued to grow at 37°C. At designated time points, samples were collected, serially diluted using sterile 1× PBS, and plated for determination of CFU per milliliter on LB plates. Plates were then incubated at 30°C overnight, and colonies were counted the next day.

Antibiotic sensitivity assay.

For ZOI assays, a lawn of overnight cultures (100 μL) was spread on an LB plate and allowed to dry for 15 min. Ten microliters of antibiotic solution (100 mg/mL PenG, 10 mg/mL meropenem, 20 mg/mL mecillinam, 12 mg/mL colistin, 100% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO], 50 mg/mL trimethoprim, 5 mg/mL tetracycline, 100% hydrogen peroxide, 100 mg/mL vancomycin, 100 mg/mL ramoplanin) was placed on Thermo Scientific Oxoid antimicrobial susceptibility test filter disks (6 mm; product code 10609174) on the agar surface and incubated at 37°C overnight before measurements. Statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s t test.

Microscopy.

Strains were grown as previously described and imaged without fixation on either LB–0.8% agarose pads or M9 minimal media–0.1% Casamino Acids–0.8% agarose pads using a Leica DMi8 inverted microscope. Phase-contrast images were analyzed using MicrobeJ, an ImageJ plug-in. Default parameter settings were applied.

Spontaneous suppressor identification.

Spontaneous suppressors were obtained from the pgi mutant on salt-free LB, followed by incubation at 37°C overnight. Colonies were single-colony purified, grown overnight in LB, and then validated for stability of the mutation by renewed growth in salt-free LB. Validated suppressors were identified using whole-genome sequencing (Microbial Genome Sequencing Center [MiGS], Pittsburg, PA) using NCBI NC_002505 and NC_002506 as the reference genomes.

Metabolomics.

Samples were diluted 1:100 from stationary growth into LB and grown for 1.5 h at 37°C to reach exponential growth. They were centrifuged at 750 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 80% (vol/vol) methanol. The samples were kept at −80°C and transferred to the Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility (Cornell University). There, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 to 8°C to pellet the cell debris. Then, the metabolite-containing supernatant was transferred to a new 15-mL conical tube on dry ice and lyophilized to a pellet using no heat. The samples were resuspended with 50% acetonitrile (ACN) at 0°C, centrifuged, and dried down for final reconstitution in 100 μL of ACN-H2O-formic acid (50/50/0.1) for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis.

Chromatographic separation was performed on a Vanquish ultrahigh-performance LC (UHPLC) system coupled to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). For HILIC chromatography, a SeQuant ZIC pHILIC column (5 μm; 2.1 by 150 mm) was used. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 10 mM ammonium acetate in water at pH 9.8 and (B) acetonitrile. The gradient was as follows: 0 to 15 min, 90 to 30% solvent B; 15 to 18 min, isocratic 30% solvent B;1 8 to 19 min, 30 to 90% solvent B; 19 to 27 min, 90% solvent B. This was followed by 3 min of re-equilibration of the column before the next run. The flow rate was 250 μL/min, and the injection volumes were set to 2 μL. To avoid possible bias, the sequence of injections was randomized.

All of the samples were analyzed by negative and positive electrospray ionization (ESI) in full scan MS mode. Nitrogen as the sheath, auxiliary, and sweep gas was set at 50, 8, and 1 U, respectively. Data were acquired under a resolving power of 120,000 (at m/z 200); automatic gain control target, 3e6 ions; maximum injection time, 100 ms; scan range, 67 to 1,005 m/z; spray voltage, 3.50 kV; and capillary temperature, 275°C. For the global quality control (QC) sample, full-scan MS1 data were acquired after every 5 to 10 samples and used for normalization in quantitation data analysis by Compound Discoverer 3.1 software. ESI−/+ data-dependent MS/MS spectra were generated on the QC sample and used for identification of metabolites. The acquired raw files were processed using commercial software, Compound Discoverer 3.1 (CD 3.1), from Thermo Fisher Scientific with an untargeted metabolomics workflow for normalization, peak alignment, related statistical analyses, and compound identification/annotation. An in-house mzVault spectral library and the public mzCloud database were used to annotate compounds on an MS/MS level with a mass tolerance of 10 ppm, and additional databases, including ChemSpider, BioCyc, Human Metabolome Database, and the KEGG database, were searched for annotations and pathway analyses.

The software parameters for alignment were 5 ppm mass tolerance for the adaptive curve model and 0.5 min maximum shift allowed. For detecting unknown compounds, 5 ppm mass tolerance for detection was used along with 30% intensity tolerance, 3 for the signal-to-noise threshold, and 2 × 106 as the minimum peak intensity. Multivariate analysis was done, and PCA showed a clear differentiation between groups. QC (pooled samples of equal volume) was used for normalization across all samples, and QC (group) samples were used for identification.

Quantification of sugars.

Glucose in LB was quantified using the glucose (GO) assay kit from Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. GAGO20) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In summary, d-glucose is converted to d-gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide. The basic hydrogen peroxide is then mixed with reduced o-dianisidine, and a colorimetric reaction occurs that is measured at 540 nm. A standard curve was created using known glucose concentrations. Trehalose was measured using the Meganzyme kit K-TREH, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Tolerance research in the Dörr lab is supported by NIH R01-AI143704. M.K. is supported by NSF GRFP no. DGE-1650441.

We thank John Helmann and Yesha Patel for critical comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Tobias Dörr, Email: td348@cornell.edu.

George O'Toole, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brauner A, Fridman O, Gefen O, Balaban NQ. 2016. Distinguishing between resistance, tolerance and persistence to antibiotic treatment. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:320–330. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazarovits G, Gefen O, Cahanian N, Adler K, Fluss R, Levin-Reisman I, Ronin I, Motro Y, Moran-Gilad J, Balaban NQ, Strahilevitz J. 2022. Prevalence of antibiotic tolerance and risk for reinfection among E. coli bloodstream isolates: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 75:1706–1713. 10.1093/cid/ciac281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin-Reisman I, Ronin I, Gefen O, Braniss I, Shoresh N, Balaban NQ. 2017. Antibiotic tolerance facilitates the evolution of resistance. Science 355:826–830. 10.1126/science.aaj2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulaiman JE, Lam H. 2021. Evolution of bacterial tolerance under antibiotic treatment and its implications on the development of resistance. Front Microbiol 12:617412. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.617412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Windels EM, Michiels JE, Van den Bergh B, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2019. Antibiotics: combatting tolerance to stop resistance. mBio 10:e02095-19. 10.1128/mBio.02095-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reygaert WC. 2018. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol 4:482–501. 10.3934/microbiol.2018.3.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross T, Ransegnola B, Shin J-H, Weaver A, Fauntleroy K, VanNieuwenhze MS, Westblade LF, Dörr T. 2019. Spheroplast-mediated carbapenem tolerance in Gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00756-19. 10.1128/AAC.00756-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dörr T. 2021. Understanding tolerance to cell wall–active antibiotics. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1496:35–58. 10.1111/nyas.14541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Typas A, Banzhaf M, Gross CA, Vollmer W. 2011. From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:123–136. 10.1038/nrmicro2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver AI, Murphy SG, Umans BD, Tallavajhala S, Onyekwere I, Wittels S, Shin J-H, VanNieuwenhze M, Waldor MK, Dörr T. 2018. Genetic determinants of penicillin tolerance in Vibrio cholerae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e01326-18. 10.1128/AAC.01326-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dörr T, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2015. Endopeptidase-mediated beta lactam tolerance. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004850. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monahan LG, Turnbull L, Osvath SR, Birch D, Charles IG, Whitchurch CB. 2014. Rapid conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to a spherical cell morphotype facilitates tolerance to carbapenems and penicillins but increases susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1956–1962. 10.1128/AAC.01901-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng AT, Ottemann KM, Yildiz FH. 2015. Vibrio cholerae response regulator VxrB controls colonization and regulates the type VI secretion system. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004933. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dörr T, Alvarez L, Delgado F, Davis BM, Cava F, Waldor MK. 2016. A cell wall damage response mediated by a sensor kinase/response regulator pair enables beta-lactam tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:404–409. 10.1073/pnas.1520333113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin J-H, Choe D, Ransegnola B, Hong H-R, Onyekwere I, Cross T, Shi Q, Cho B-K, Westblade LF, Brito IL, Dörr T. 2021. A multifaceted cellular damage repair and prevention pathway promotes high level tolerance to β-lactam antibiotics. EMBO Rep 22:e51790. 10.15252/embr.202051790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peschek N, Herzog R, Singh PK, Sprenger M, Meyer F, Fröhlich KS, Schröger L, Bramkamp M, Drescher K, Papenfort K. 2020. RNA-mediated control of cell shape modulates antibiotic resistance in Vibrio cholerae. Nat Commun 11:6067. 10.1038/s41467-020-19890-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teschler JK, Cheng AT, Yildiz FH. 2017. The two-component signal transduction system VxrAB positively regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 199:e00139-17. 10.1128/JB.00139-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho SY, Yoon S. 2020. Structural analysis of the sensor domain of the β-lactam antibiotic receptor VbrK from Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 533:155–161. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Wang Q, Zhang H, Yang M, Khan MI, Zhou X. 2016. Sensor histidine kinase is a β-lactam receptor and induces resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:1648–1653. 10.1073/pnas.1520300113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh BC, Chua YK, Qian X, Lin J, Savko M, Dedon PC, Lescar J. 2020. Crystal structure of the periplasmic sensor domain of histidine kinase VbrK suggests indirect sensing of β-lactam antibiotics. J Struct Biol 212:107610. 10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan K, Teschler JK, Wu R, Jedrzejczak RP, Zhou M, Shuvalova LA, Endres MJ, Welk LF, Kwon K, Anderson WF, Satchell KJF, Yildiz FH, Joachimiak A. 2021. Sensor domain of histidine kinase VxrA of Vibrio cholerae: a hairpin-swapped dimer and its conformational change. J Bacteriol 203:e00643-20. 10.1128/JB.00643-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harper CE, Zhang W, Shin J-H, van Wijngaarden E, Chou E, Lee J, Wang Z, Dörr T, Chen P, Hernandez CJ. 2022. Mechanical stimuli activate gene expression via a cell envelope stress sensing pathway. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.09.25.509347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hernández SB, Dörr T, Waldor MK, Cava F. 2020. Modulation of peptidoglycan synthesis by recycled cell wall tetrapeptides. Cell Rep 31:107578. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sit B, Srisuknimit V, Bueno E, Zingl FG, Hullahalli K, Cava F, Waldor MK. 2023. Undecaprenyl phosphate translocases confer conditional microbial fitness. Nature 613:721–728. 10.1038/s41586-022-05569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roney IJ, Rudner DZ. 2022. Two broadly conserved families of polyprenyl-phosphate transporters. Nature 613:729–734. 10.1038/s41586-022-05587-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dörr T, Lam H, Alvarez L, Cava F, Davis B, Waldor M. 2014. A novel peptidoglycan binding protein crucial for PBP1A-mediated cell wall biogenesis in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Genet 10:e1004433. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caparrós M, Pisabarro AG, de Pedro MA. 1992. Effect of D-amino acids on structure and synthesis of peptidoglycan in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 174:5549–5559. 10.1128/jb.174.17.5549-5559.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho BT, Basler M, Mekalanos JJ. 2013. Type 6 secretion system–mediated immunity to type 4 secretion system–mediated gene transfer. Science 342:250–253. 10.1126/science.1243745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt KL, Peterson ND, Kustusch RJ, Wissel MC, Graham B, Phillips GJ, Weiss DS. 2004. A predicted ABC transporter, FtsEX, is needed for cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 186:785–793. 10.1128/JB.186.3.785-793.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Möll A, Dörr T, Alvarez L, Chao MC, Davis BM, Cava F, Waldor MK. 2014. Cell separation in Vibrio cholerae is mediated by a single amidase whose action is modulated by two nonredundant activators. J Bacteriol 196:3937–3948. 10.1128/JB.02094-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Y, Helm JS, Chen L, Ye X-Y, Walker S. 2003. Ramoplanin inhibits bacterial transglycosylases by binding as a dimer to lipid II. J Am Chem Soc 125:8736–8737. 10.1021/ja035217i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Citron DM, Merriam CV, Tyrrell KL, Warren YA, Fernandez H, Goldstein EJC. 2003. In vitro activities of ramoplanin, teicoplanin, vancomycin, linezolid, bacitracin, and four other antimicrobials against intestinal anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2334–2338. 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2334-2338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes CA, Dalia TN, Dalia AB. 2017. Systematic genetic dissection of PTS in Vibrio cholerae uncovers a novel glucose transporter and a limited role for PTS during infection of a mammalian host. Mol Microbiol 104:568–579. 10.1111/mmi.13646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulanger EF, Sabag-Daigle A, Thirugnanasambantham P, Gopalan V, Ahmer BMM. 2021. Sugar-phosphate toxicities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 85:e00123-21. 10.1128/MMBR.00123-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christodoulou D, Link H, Fuhrer T, Kochanowski K, Gerosa L, Sauer U. 2018. Reserve flux capacity in the pentose phosphate pathway enables Escherichia coli’s rapid response to oxidative stress. Cell Syst 6:569–578.E7. 10.1016/j.cels.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sezonov G, Joseleau-Petit D, D'Ari R. 2007. Escherichia coli physiology in Luria-Bertani broth. J Bacteriol 189:8746–8749. 10.1128/JB.01368-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimmele M, Boos W. 1994. Trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 176:5654–5664. 10.1128/jb.176.18.5654-5664.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y, Yan K, Qin Q, Raimi OG, Du C, Wang B, Ahamefule CS, Kowalski B, Jin C, van Aalten DMF, Fang W. 2022. Phosphoglucose isomerase is important for Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall biogenesis. mBio 13:e01426-22. 10.1128/mbio.01426-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuckman D, Donnelly RJ, Zhao FX, Jacobs WR, Connell ND. 1997. Interruption of the phosphoglucose isomerase gene results in glucose auxotrophy in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol 179:2724–2730. 10.1128/jb.179.8.2724-2730.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad C, Freese E. 1974. Cell lysis of Bacillus subtilis caused by intracellular accumulation of glucose-1-phosphate. J Bacteriol 118:1111–1122. 10.1128/jb.118.3.1111-1122.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav V, Panilaitis B, Shi H, Numuta K, Lee K, Kaplan DL. 2011. N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate deacetylase (nagA) is required for N-acetyl glucosamine assimilation in Gluconacetobacter xylinus. PLoS One 6:e18099. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meibom KL, Li XB, Nielsen AT, Wu C-Y, Roseman S, Schoolnik GK. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae chitin utilization program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:2524–2529. 10.1073/pnas.0308707101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sloan R, Surber J, Roy EJ, Hartig E, Morgenstein RM. 2022. Enzyme 1 of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system is involved in resistance to MreB disruption in wild-type and ΔenvC cells. Mol Microbiol 118:588–600. 10.1111/mmi.14988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sachla AJ, Helmann JD. 2019. A bacterial checkpoint protein for ribosome assembly moonlights as an essential metabolite-proofreading enzyme. Nat Commun 10:1526. 10.1038/s41467-019-09508-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weaver AI, Jiménez-Ruiz V, Tallavajhala SR, Ransegnola BP, Wong KQ, Dörr T. 2019. Lytic transglycosylases RlpA and MltC assist in Vibrio cholerae daughter cell separation. Mol Microbiol 112:1100–1115. 10.1111/mmi.14349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Espinosa E, Daniel S, Hernández SB, Goudin A, Cava F, Barre F-X, Galli E. 2021. l-Arabinose induces the formation of viable nonproliferating spheroplasts in Vibrio cholerae. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e02305-20. 10.1128/AEM.02305-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weart RB, Levin PA. 2003. Growth rate-dependent regulation of medial FtsZ ring formation. J Bacteriol 185:2826–2834. 10.1128/JB.185.9.2826-2834.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill NS, Buske PJ, Shi Y, Levin PA. 2013. A moonlighting enzyme links Escherichia coli cell size with central metabolism. PLoS Genet 9:e1003663. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weaver AI, Alvarez L, Rosch KM, Ahmed A, Wang GS, van Nieuwenhze MS, Cava F, Dörr T. 2022. Lytic transglycosylases mitigate periplasmic crowding by degrading soluble cell wall turnover products. Elife 11:e73178. 10.7554/eLife.73178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stokes JM, Lopatkin AJ, Lobritz MA, Collins JJ. 2019. Bacterial metabolism and antibiotic efficacy. Cell Metab 30:251–259. 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrières L, Hémery G, Nham T, Guérout A-M, Mazel D, Beloin C, Ghigo J-M. 2010. Silent mischief: bacteriophage Mu insertions contaminate products of Escherichia coli random mutagenesis performed using suicidal transposon delivery plasmids mobilized by broad-host-range RP4 conjugative machinery. J Bacteriol 192:6418–6427. 10.1128/JB.00621-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6:343–345. 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lazarus JE, Warr AR, Kuehl CJ, Giorgio RT, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2019. A new suite of allelic-exchange vectors for the scarless modification of proteobacterial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e00990-19. 10.1128/AEM.00990-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyata ST, Unterweger D, Rudko SP, Pukatzki S. 2013. Dual expression profile of type VI secretion system immunity genes protects pandemic Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003752. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson AC, Perego M, Hoch JA. 2007. New transposon delivery plasmids for insertional mutagenesis in Bacillus anthracis. J Microbiol Methods 71:332–335. 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S7 and Tables S1 to S4. Download jb.00476-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 3.4 MB (3.4MB, pdf)