Abstract

Pooled CRISPR screens coupled with single-cell RNA-sequencing have enabled systematic interrogation of gene function and regulatory networks. Here, we introduce Cas13 RNA Perturb-seq (CaRPool-seq), which leverages the RNA-targeting CRISPR–Cas13d system and enables efficient combinatorial perturbations alongside multimodal single-cell profiling. CaRPool-seq encodes multiple perturbations on a cleavable CRISPR array that is associated with a detectable barcode sequence, allowing for the simultaneous targeting of multiple genes. We compared CaRPool-seq to existing Cas9-based methods, highlighting its unique strength to efficiently profile combinatorially perturbed cells. Finally, we apply CaRPool-seq to perform multiplexed combinatorial perturbations of myeloid differentiation regulators in an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) model system and identify extensive interactions between different chromatin regulators that can enhance or suppress AML differentiation phenotypes.

Recent technological advances that couple pooled genetic perturbations with single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) or multimodal characterization (that is, Perturb-seq, CRISPR droplet sequencing, CRISP–seq and expanded CRISPR-compatible cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (ECCITE-seq)1–4), promise to transform our understanding of gene function. In particular, the ability to perform combinatorial perturbations represents an opportunity to decode complex regulatory networks, with pioneering work demonstrating the ability to identify epistasis and other genetic interactions5–7. However, there are specific technical and analytical challenges associated with pooled single-cell screens that are exacerbated when considering combinatorial perturbations. For example, undetected or incorrectly assigned single-guide RNAs can affect up to 20% of cells6; this is compounded when multiple independent sgRNAs are introduced and independently detected in each cell. Moreover, perturbations introduced by Cas9 are not uniformly efficient, and a considerable fraction of targeted cells may exhibit no phenotypic effects of perturbation8,9. Therefore, when performing two or more simultaneous perturbations, the fraction of cells where all perturbations are both successfully introduced and successfully detected can decrease dramatically.

Type VI CRISPR–Cas proteins, such as the VI-D family member RfxCas13d, are programmable RNA-guided and RNA-targeting nucleases that enable targeted RNA knockdown. Notably, RfxCas13d is also capable of processing a CRISPR array into multiple mature CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs)10, presenting an attractive option for combinatorial perturbations at the RNA level. Recently, we confirmed that RfxCas13d can lead to striking target-RNA knockdown, and learned a set of optimal targeting rules from thousands of guide RNAs tiling multiple transcripts11. We therefore sought to combine pooled CRISPR–Cas13 screens with single-cell readouts to perform combinatorial and multimodal pooled genetic screens.

Results

Engineered CRISPR arrays enable Cas13 gRNA capture in single cells

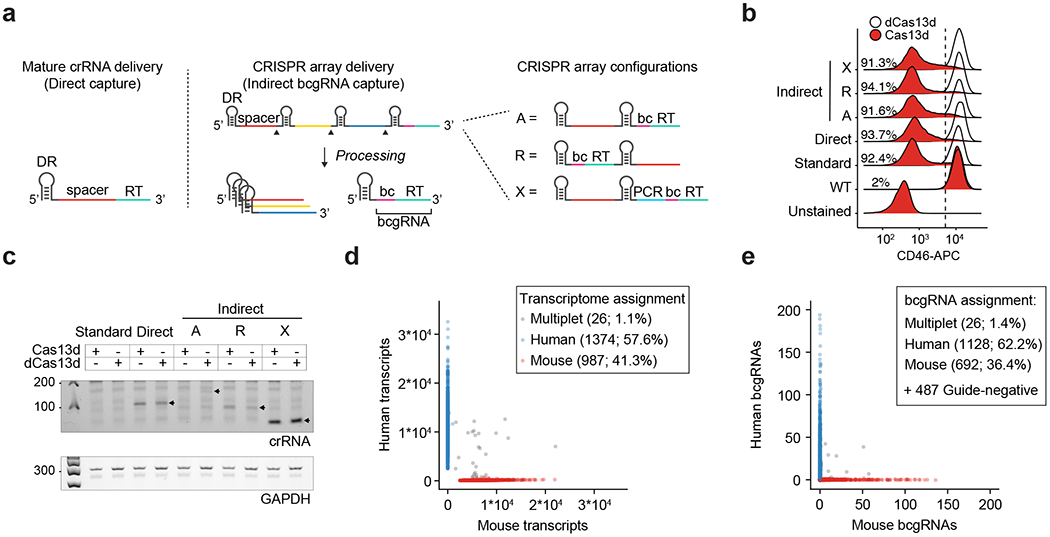

Our method for Cas13 RNA Perturb-seq (CaRPool-seq) is enabled via an optimized molecular strategy to deliver individual or multiple gRNA perturbations in each cell and detect their identity during a single-cell sequencing experiment. Type VI-A, C and D Cas13 crRNAs consist of a short 5′ direct repeat and a variable spacer (also called gRNA) at the 3′ end, and therefore lack a common priming site for reverse transcription (RT). We developed two alternative approaches for Cas13 gRNA detection: (1) ‘direct’ capture, which adds a ‘capture sequence’ to the 3′ end of the 23-nt target spacer (Fig. 1a); and (2) an ‘indirect’ capture strategy, where a dedicated crRNA of the CRISPR array contains an array specific barcode (barcode gRNA, bcgRNA) with different positional configurations of the bcgRNA within a CRISPR array (Fig. 1a). We evaluated the performance of each method by targeting cell surface proteins and measuring knockdown via flow cytometry (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1), and by quantifying crRNA detection via PCR with reverse transcription (Fig. 1c). While all methods successfully induced robust knockdown (Fig. 1b), we found that indirect guide capture with an optimized configuration resulted in the strongest crRNA transcript detection ability (configuration X, Fig. 1c), for both catalytically active and inactive Cas13 proteins.

Fig. 1 |. Efficient capture of gRNAs for CaRPool-seq.

a, Scheme of direct and indirect array-based gRNA capture approaches. Direct capture uses a reverse transcription (RT) handle added directly downstream to the gRNA. For the indirect capture method, a bcgRNA is captured as a cleavable part of a CRISPR array. Three different CRISPR array configurations (A, R and X) have been tested (bc, barcode; PCR, PCR primer annealing site; A, array; R, reversed array configuration; X, extra PCR handle). b, Density plots showing the CD46-APC signal on Cas13d-mediated CD46 knockdown (red) and dCas13d-mediated controls (white) using the four CaRPool-seq configurations described in a, as well as standard gRNA. The CS1 reverse transcription handle was used in all cases. N > 5,000 cells examined per sample. c, PCR amplicons of reverse-transcribed crRNAs from lentivirally infected cells used in b of one representative experiment. Expected product sizes: Direct capture 109 bp, A-type and R-type array 99 bp, X-type array 52 bp, unprocessed A-type array (159 bp). d, Species-mixing experiment profiling 2,387 HEK293FT-Cas13d or mouse NIH/3T3-Cas13d cells lentivirally transduced with CRISPR array virus. The CRISPR array includes a NT gRNA and a bcgRNA in X-type configuration. Axes show the number of transcripts associated with each cell barcode. Datapoint colors and boxed labels are assigned based on transcriptome classification (Methods). e, Number of bcgRNAs associated with each cell barcode. Datapoint colors are based on transcriptome classification, and boxed labels are based on observed bcgRNA.

These results demonstrate that RfxCas13d crRNAs can be modified by adding a common reverse transcription handle either directly to the gRNA or as a separate bcgRNA as part of a CRISPR array, allowing for reverse transcription and amplification. Notably, our strategy for indirect detection is well-suited for delivering multiple gRNAs into a single cell alongside a detectable bcgRNA that encodes the collective identity of these perturbations. In addition, using a unique set of reverse transcription handle and Illumina PCR priming sequence in our modified crRNA (Extended Data Fig. 2) ensures that these perturbations can be detected not only alongside scRNA-seq, but also when profiling additional molecular modalities (for example, CITE-seq12 for simultaneous transcriptome and surface protein profiling).

As proof of principle, we first tested the ability of CaRPool-seq to detect and assign bcgRNAs in a single-cell species-mixing experiment. We separately transduced RfxCas13d-expressing human embryonic kidney 293FT (HEK293FT) and mouse NIH/3T3 cells with a viral pool of three CRISPR arrays containing a nontargeting (NT) gRNA and a species-specific bcgRNA. We profiled a mixture of human and mouse cells with the 10X Genomics Chromium system (v.3), aiming to detect both cellular transcriptomes and the bcgRNAs. Of 2,387 cells, we found that 78.5% expressed a single bcgRNA (1.1% >1 bcgRNAs; 20.4% no detected bcgRNA). Moreover, we observed extremely high concordance between RNA and bcgRNA labels in singlet cells (99.2%) (Fig. 1d,e). These numbers demonstrate that CaRPool-seq enables pooled perturbation screens that can be efficiently and accurately demultiplexed into a single-cell readout.

CaRPool-seq enables combinatorial gene targeting with multimodal single-cell readout

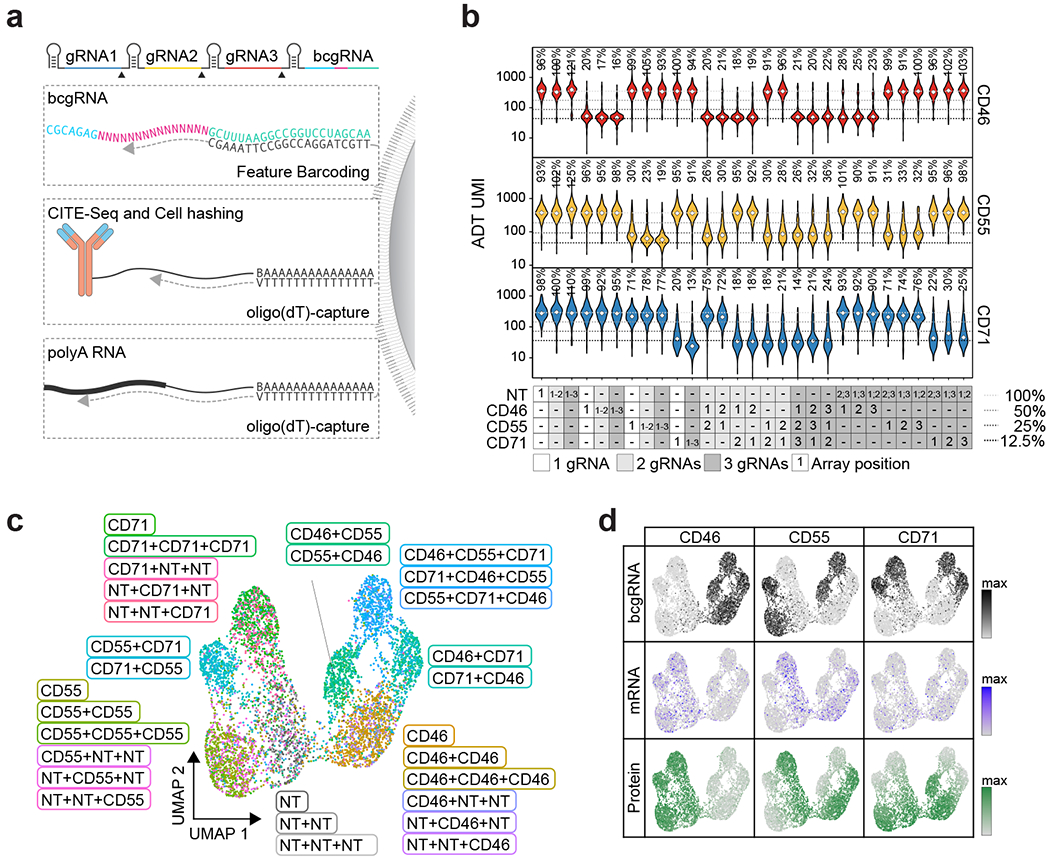

Next, we tested the ability of CaRPool-seq to distinguish combinatorial perturbations on multiple molecular modalities at single-cell resolution. We designed gRNAs targeting three cell surface proteins, CD46, CD55 and CD71, as well as NT gRNAs. We created 29 crRNA arrays (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), each of which contains up to three gRNAs and a bcgRNA, allowing for the perturbation of these genes individually or in combination. We transduced HEK293FT cells with a viral pool of all crRNAs and performed CaRPool-seq with CITE-seq12 readout (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3a), allowing the assessment of each perturbation on both the cellular transcriptome and antibody-derived tags (ADTs) associated with CD46, CD55 and CD71 surface protein levels.

Fig. 2 |. CaRPool-seq enables combinatorial gene targeting with a multimodal single-cell readout.

a, CaRPool-seq can be combined with CITE-seq and Cell Hashing modalities. b, Violin plots depicting protein expression of target genes (ADT UMI counts for CD46, CD55, CD71), grouped by CRISPR arrays (n = 29; median number of cells 269; s.d. 97 cells). Three dashed lines indicate 50, 25 and 12.5% UMI count relative to the median of all NT cells. Diamonds indicate the median UMI count. The number above each violin plot indicates the mean level of reduction across single cells. CD71 + CD71 was not included in the experiment. c, UMAP visualization of single-cell protein expression profiles of CaRPool-seq experiment (n = 6,986 cells). Cells are colored based on the single or combinatorial perturbations they received. d, Expression levels of bcgRNA (black), mRNA (blue) and protein (ADT, green) for CD46, CD55, CD71 superimposed on the UMAP visualization (n = 6,986 total cells).

We obtained 9,355 single-cell profiles and demultiplexed them into groups based on the detected bcgRNA (Extended Data Fig. 3b; 74.7% expressed a single bcgRNA, 80.8% expressed at least one bcgRNA). We observed, on average, a 76.5% (±5.7%) mean reduction in protein levels for each targeted gene after perturbation with Cas13 demonstrating clear evidence of robust molecular perturbation (Fig. 2b–d). Moreover, the strength of knockdown was similar for multi-gRNA crRNA arrays relative to single gRNA perturbations (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3c–e). When examining transcriptomic pseudobulk profiles for all 26 targeting gRNA groups, we observed decreased messenger RNA expression for each targeted transcript, even when perturbing transcripts of three genes simultaneously (15 examples in Extended Data Fig. 3f,g). The average strength of transcriptomic knockdown (mean 65%, s.d. 8.7%) was consistently reduced compared to the observed protein reduction. Target RNAs are continuously being produced and degraded before the target can be translated into protein. Further, analogous to how Cas9-nuclease targeting often produces RNAs degraded by nonsense mediated decay13, it is possible that Cas13 cleavage produces RNA molecules that can be detected by scRNA-seq but cannot be translated into functional protein14, suggesting that the level of measured RNA knockdown underestimates the phenotypic effect of Cas13 perturbation.

We performed several analyses to demonstrate that Cas13d-mediated gene knockdown does not introduce notable off-target effects or deleteriously alter cellular fitness. We identified eight genes whose sequence contains potential off-target binding sites for any of our three perturbations, but found that the expression of these genes was not significantly changed in our CaRPool-seq data (Extended Data Fig. 4a). We also performed CD55 target knockdown followed by more sensitive bulk RNA-seq and found no evidence for elevated levels of Cas13d off-targets (Extended Data Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 3). In addition, previous reports have suggested that expression and target-dependent activation of Cas13d can induce broad nonspecific degradation of cytoplasmic and nuclear mRNA, and a reduction in cellular proliferation or fitness15. Notably, transcripts of mitochondrial genes have been suggested to be at least partially protected from Cas13d collateral activity15. Hence in the presence of collateral activity, mitochondrial genes may appear relatively upregulated compared to nuclear and cytoplasmic genes. Therefore, we compared mitochondrial gene expression levels in cells that have received one or more targeting gRNAs compared to NT control cells (Extended Data Fig. 4c), and did not observe upregulation in our CaRPool-seq data. Last, we classified cell cycles stage for each cell, and found no difference in cell cycle distributions (indicative of their proliferation state) compared to NT control cells (Extended Data Fig. 4d–f). Our findings likely reflect CaRPool-seq’s controlled delivery of Cas13d and gRNAs using single integration lentiviral systems instead of transient overexpression, which is consistent with the suggestion that lower and more controlled Cas13 expression can mitigate collateral activity16.

CaRPool-seq efficiently recovers cells with multiple perturbations

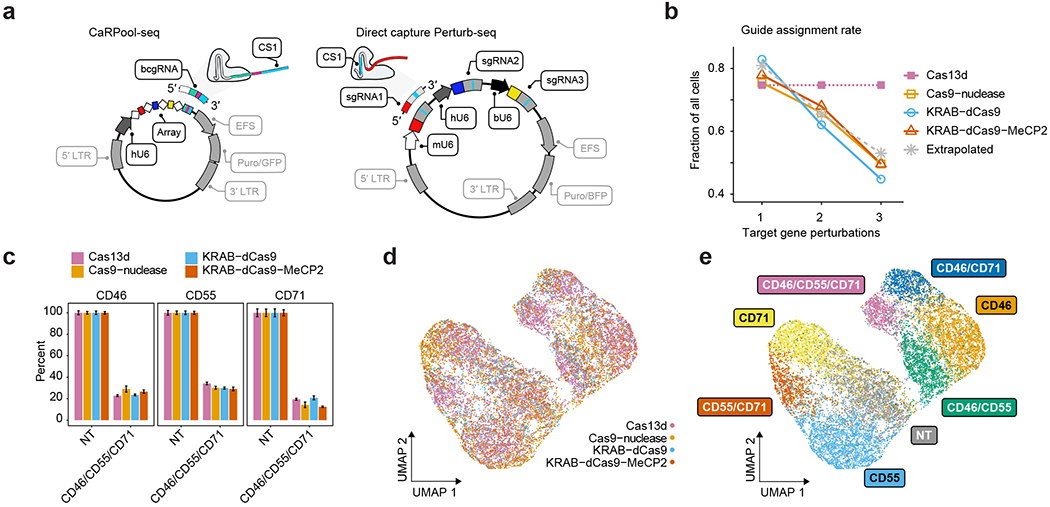

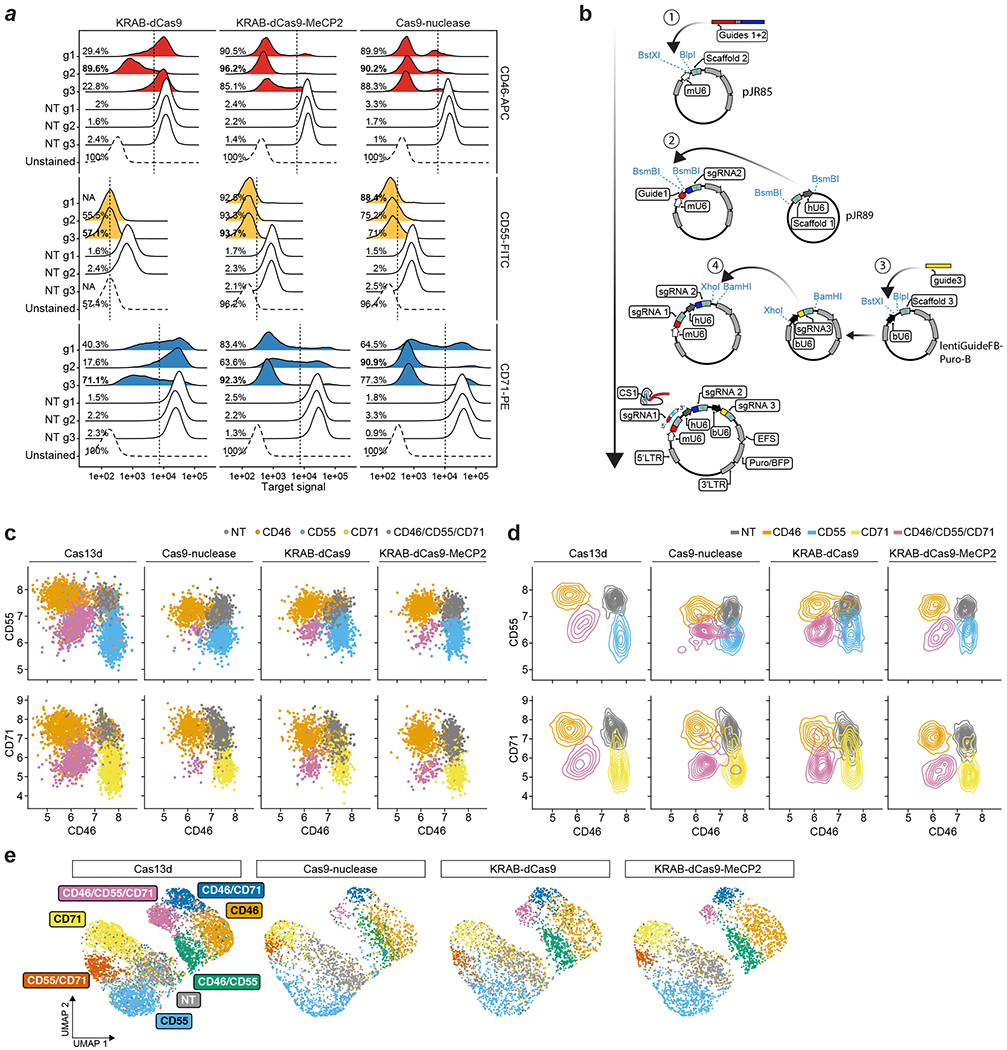

We next benchmarked the performance of CaRPool-seq against direct capture Perturb-seq6 using three different Cas9 effectors: Cas9-nuclease, a first-generation CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) system, Krüppel associated box (KRAB) fused to dCas9 (refs. 17,18) and a second-generation, dual-effector CRISPRi system, KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2 (refs. 18,19). In CaRPool-seq one bcgRNA encodes the combined gRNA identities, while direct capture Perturb-seq requires independent detection of one sgRNA feature per perturbation (Fig. 3a). We replicated our previously described experimental system, targeting the same three cell surface markers (CD46, CD55 and CD71) alone or in combination. For each target, we evaluated three sgRNAs from established CRISPR-KO20 and CRISPRi21 sgRNA libraries (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and selected the best sgRNA for Perturb-seq (Extended Data Fig. 5b). In addition, we used Cell Hashing22 to label cells targeted with vectors encoding single, double or triple perturbations. As in CaRPool-seq, we quantified gRNA, RNA and ADT levels in each cell.

Fig. 3 |. Benchmarking CaRPool-seq against alternative combinatorial perturbation approaches.

a, Plasmid vectors for lentivirus production for triple perturbation scenarios comparing CaRPool-seq and Direct Capture Perturb-seq6. b, Fraction of cells where the correct combination of gRNA was detected for single, double and triple perturbations. The dashed gray line represents a theoretical extrapolation based on an assumption of independent sgRNA detection with P = 0.81 (ref. 6). c, Relative expression of cell surface proteins CD46, CD55 and CD71 in cells with assigned NT (s)gRNAs or a combination of three targeting (s)gRNAs (NT, n = 448, 711, 510, 577; CD46/CD55/CD71, n = 874, 55, 142, 89 for Cas13d, Cas9-nuclease, KRAB–dCas9 and KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2, respectively). The expression level of each target is normalized to NT control. Bars indicate mean across cells with s.e.m. error bars. d, Protein level ADT-based clustering of single-cell expression profiles of merged CaRPool-seq (n = 6,986), Perturb-seq experiments using Cas9 (n = 2,836), KRAB–dCas9 (n = 2,911) or KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2 (n = 3,038). Cells are colored by perturbation technology. e, As for d. Cells are colored based on the single or combinatorial perturbation received.

Our benchmarking analysis found that, in contrast to CaRPool-seq, alternative Cas9-based approaches struggled to efficiently identify and detect combinatorial perturbations (Fig. 3b). For example, in the KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2 experiment, we recovered 1,570 cells that received vectors targeting three genes. Among these cells, only 779 (49.6%) were associated with the correct three sgRNA after sequencing. In the remaining cells, we detected too few perturbations (zero, one or two gRNAs, 31.2%), too many (four or more gRNAs 10.0%), or an improper combination of three gRNA (9.2%). This observed drop-off is fully consistent with the theoretical expectation of recovery for multiple independently detected gRNAs and highlights the challenge of efficiently profiling multiple perturbations with existing approaches. Since CaRPool-seq associates combinatorial perturbations with a single bcgRNA, the efficiency of detection does not vary between single and multiple perturbations.

We next compared the strength of perturbation across methods. We first considered cells where three perturbations were successfully detected based on either the bcgRNA (CaRPool-seq) or independently detected gRNA (Perturb-seq). When considering these cells, all methods successfully induced a similarly strong depletion of all three surface proteins (Cas13d 74.5%, Cas9 75.5%, KRAB–dCas9 75.2%, KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2 77.3%) (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). We next analyzed all cells based on their ADT levels. CaRPool-seq and Perturb-seq cells clustered together (Fig. 3d), and grouped by gRNA identity (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5e), again demonstrating that the strength of phenotypic protein perturbation was similar across all methods. We conclude that CaRPool-seq and Perturb-seq can both effectively introduce combinatorial perturbations into single cells. However, CaRPool-seq exhibits clear advantages in the ability to successfully identify and detect these perturbations and therefore represents an attractive approach for performing combinatorial single-cell CRISPR screens.

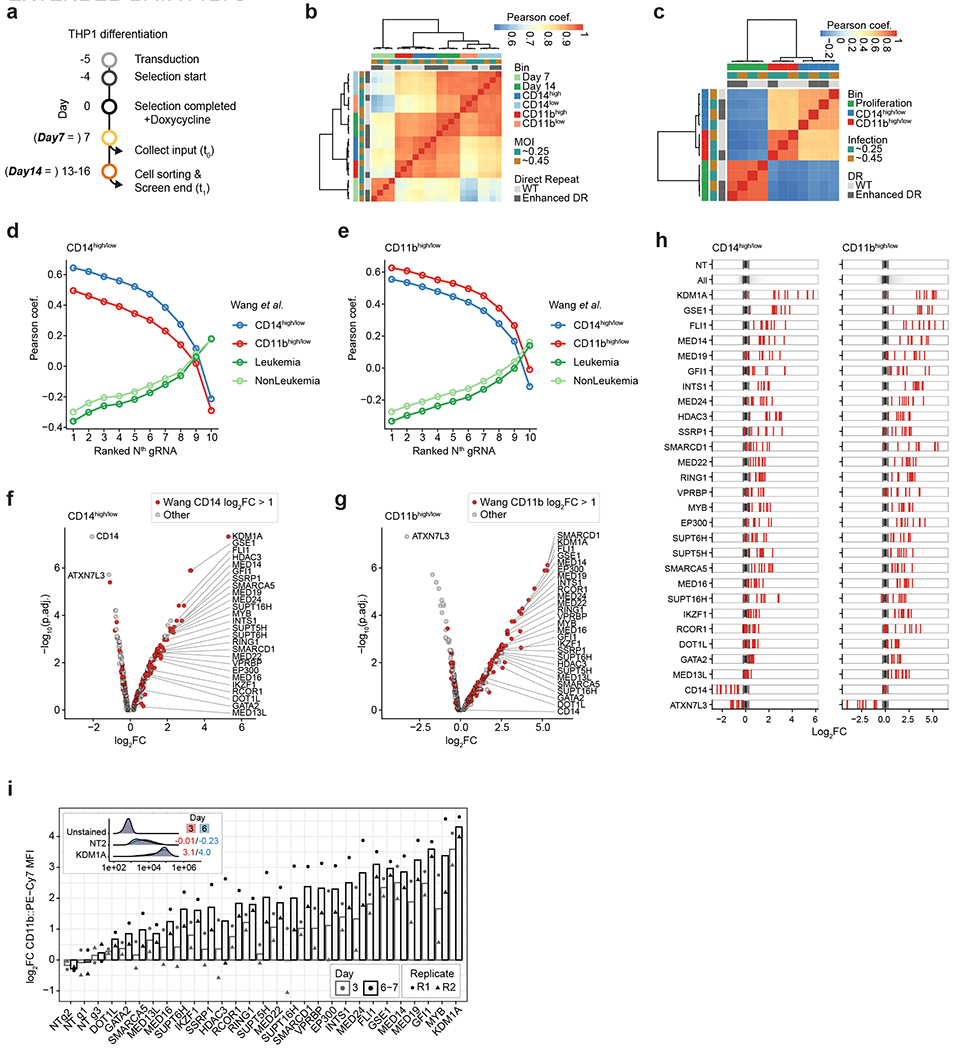

A pooled RNA-targeting CRISPR screen identifies genes involved in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) differentiation

To demonstrate the throughput and potential of CaRPool-seq to characterize genetic interactions, we performed a multiplexed screen of 158 combinatorial gene pairs. Motivated by recent work23, we aimed to characterize potential interactions between previously identified regulators of leukemic differentiation, which can influence the response to chemotherapy and small-molecule drugs. We generated a human MLL-AF9 NRASG12D AML cell line (THP1 cells), with a stably integrated doxycycline-inducible Cas13d cassette, as a model system. We first performed a bulk Cas13d CRISPR screen using a targeted library of 439 genes with ten gRNA per gene. On day 13–16 post-Cas13d induction, cells were sorted into bins based on their surface expression of CD14 and CD11b, immunophenotypic markers of monocyte differentiation. By comparing gRNA representation between low and high-expressing bins, we selected 26 genes that influenced differentiation consistently across multiple independent gRNAs and that have also been identified previously in orthogonal pooled Cas9 screens23 (Extended Data Fig. 6a–h and Supplementary Table 4). Through individual perturbations with a flow-cytometry readout, we found that target gene perturbations led to detectable CD11b expression changes after 3 days (Extended Data Fig. 6i). Consistent with previous work23, these genes were largely associated with DNA-binding and chromatin remodeling functions, and include a subset of previously identified regulators of AML differentiation.

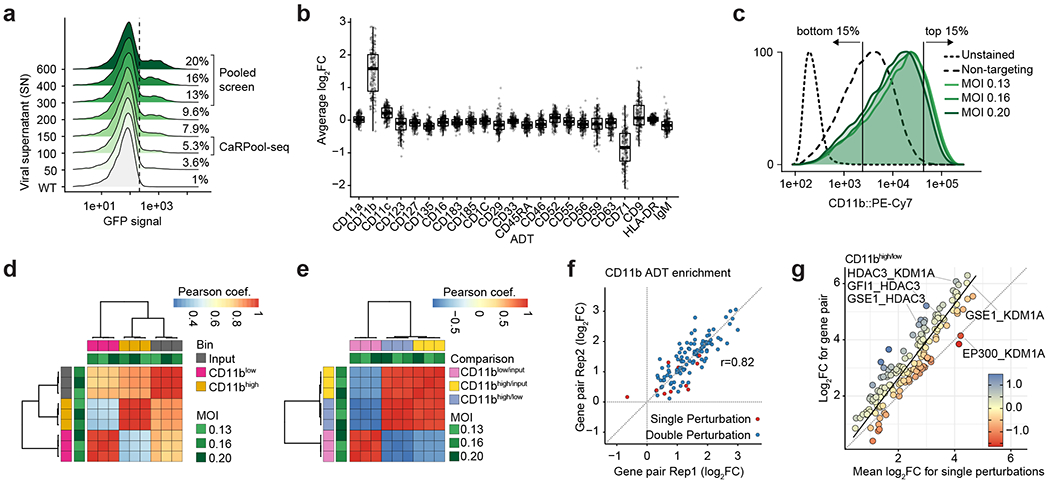

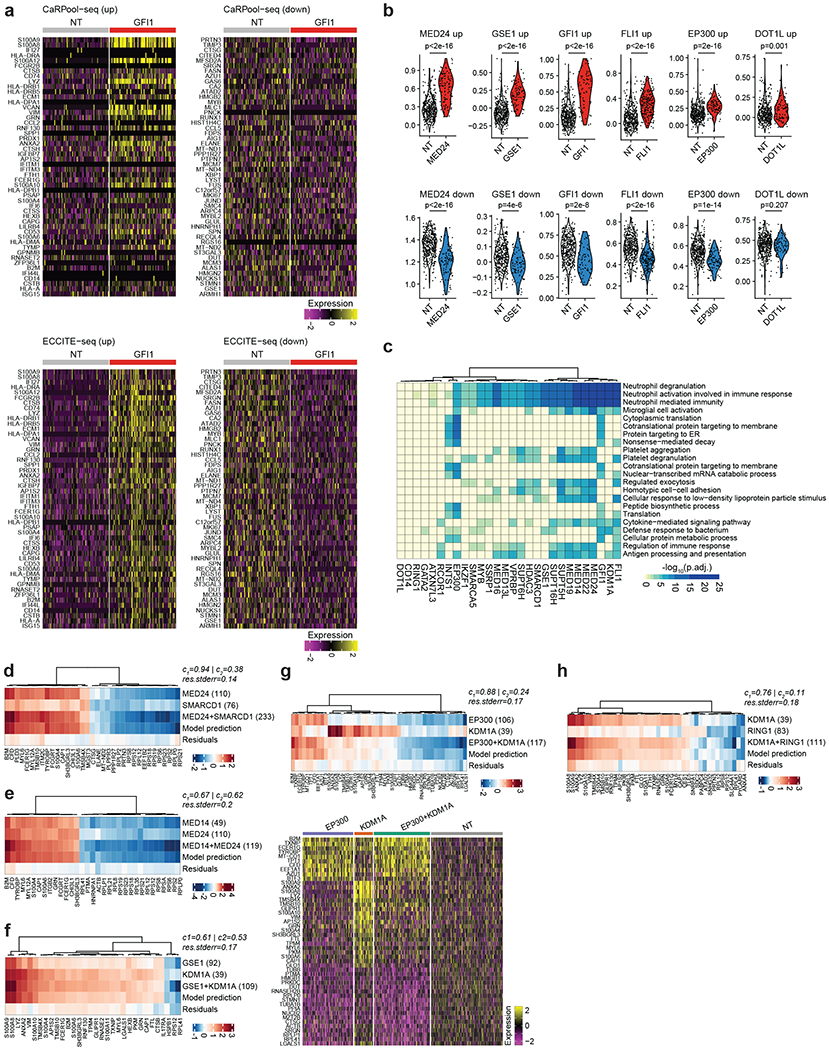

CaRPool-seq identifies genetic interactions in AML differentiation

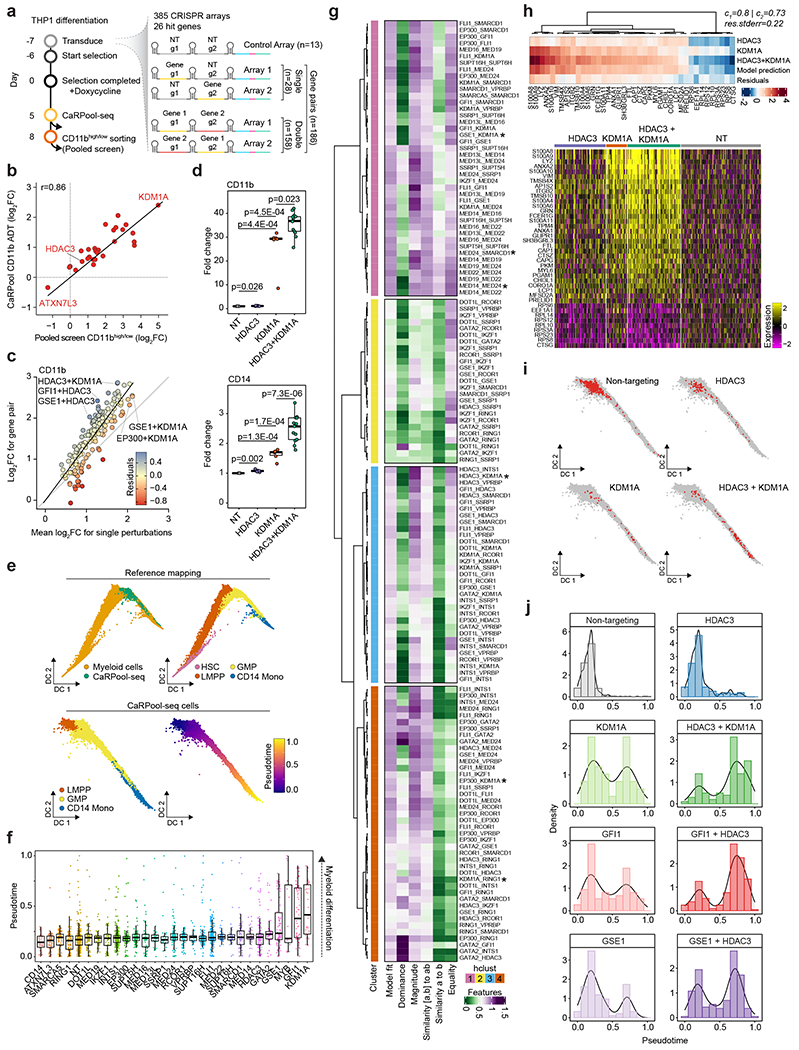

We next applied CaRPool-seq to test the effects of combinatorially perturbing these regulators (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 7a). We infected cells with a pooled library of 385 crRNA arrays. This library encoded 28 single perturbations (26 regulators and two negative control genes) and 158 paired perturbations. It also encompassed technical replicates for each perturbation using two independent gRNAs, as well as NT controls. We profiled the transcriptome, cell surface protein levels and gRNA expression for 31,308 demultiplexed single cells.

Fig. 4 |. CaRPool-seq identified genetic interactions in AML differentiation.

a, Timeline for THP1 cell infection, CaRPool-seq and pooled screen for CD11b expression. Pooled lentivirus library encodes 385 CRISPR arrays, with 158 gene pair perturbations, 28 single-gene perturbations (each with two nonoverlapping gRNAs (technical replicate); single, gene_g1/NT_g2 and NT_g1/gene_g2; pair, geneA_g1/geneB_g2 and geneA_g2/geneB_g1) and 13 NT controls. b, Correlation of bcgRNA enrichment in the pooled screen (CD11bhigh/low) and CD11b ADT log2FC for cells grouped by bcgRNA cells relative to control cells in CaRPool-seq. c, Correlation of CD11b ADT log2FC of cells with dual perturbations, and the mean log2FC of both single perturbations (n = 158 gene pairs). Residuals indicate the distance to the average linear relationship. d, Relative cell surface marker expression. Monoclonal THP1 KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2 cells were infected with dual sgRNA lentiviral particles, carrying 0, 1 or 2 targeting sgRNAs (NT + NT n = 3; KDM1A + NT n = 6; HDAC3 + NT n = 6; KDM1A + HDAC3 n = 13 combinations). Puromycin-selected cells were stained for CD11b (top, PE-Cy7) and CD14 (bottom, APC) 7 days posttransduction. Shown is the mean fluorescence intensity (>5,000 cells per sample) for each sample compared to the mean fluorescence intensity of the three NT samples (one-tailed t-tests). e, Diffusion map showing THP1 CaRPool-seq cells integrated into a subset of a human bone marrow reference (see Methods). Pseudotemporal ordering was performed jointly on all cells and is shown for CaRPool-seq (n = 30,707) separately. f, Pseudotime quantification of singly perturbed cells (total cells, n = 2,612; single-gene perturbation, median n = 74 cells; s.d. n = 86 cells). g, Regression model results decomposing the observed dual perturbation responses as a linear combination of single-gene perturbation responses (Methods). h, Comparison of transcriptional responses for dual versus single perturbation. Heatmap shows deviation in average gene expression relative to unperturbed cells for the 20 most significantly regulated genes (Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test). Average heatmap (top) is accompanied by single-cell gene expression heatmap (bottom) (HDAC3 n = 96 cells, KDM1A n = 36 cells and HDAC3 + KDM1A n = 99 cells). i, CaRPool-seq diffusion map as in e highlighting cells that have received indicated gRNAs. j, Quantification of pseudotemporal ordering of perturbed cells. Boxes in d and f indicate the median and interquartile ranges, with whiskers indicating 1.5 times the interquartile range.

We first compared the level of surface protein expression for each perturbation to NT controls (Extended Data Fig. 7b). As expected, we found that each single-gene perturbation affected CD11b expression, with observed log2 fold changes that were in strong agreement with the level of gRNA enrichment from bulk CRISPR screens (R = 0.86; Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 7c–e and Supplementary Table 5). Observed log2 fold changes for all perturbations were also reproducible (R = 0.82, Extended Data Fig. 7f) across technical replicate perturbations when comparing effects measured for independent gRNAs. We next compared the observed effects of the 158 dual gene perturbations to the effects resulting from the two corresponding single perturbations. We observed a strong correlation and found that the dual perturbation was typically stronger than the average of individual knockdowns, but weaker than the product (Fig. 4c). We also observed both synergistic and dampening effects. For example, individual knockdown of the histone demethylase KDM1A (log2fold change (FC) 2.41) and the histone deacetylase HDAC3 (log2FC 0.53) lead to strong and weak CD11b upregulation, respectively, but dual perturbation led to a synergistic effect (log2FC 2.85). In contrast, while individual knockdown of EP300 also leads to CD11b upregulation (log2FC 1.57), dual perturbation with KDM1A (log2FC 2.05) was weaker than the individual KDM1A knockdown. We observed similar findings using data from our Cas13d CD11b pooled screen (Extended Data Fig. 7g and Supplementary Table 5). To further validate the synergistic relationship between KDM1A and HDAC3 we infected KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2 expressing THP1 cells with multiple independent sgRNAs and measured CD11b and CD14 cell surface protein expression 7 days postinfection using flow cytometry. Again, we observed synergistic upregulation of both surface markers (Fig. 4d) after dual perturbation.

We next explored the transcriptional profiles in our CaRPool-seq dataset. We first sought to orthogonally validate the transcriptomic signatures we observed on perturbation of single genes by comparing with alternative technologies and datasets. We found that the differential gene expression signatures for single-gene perturbations obtained using ECCITE-seq (5′ scRNA-seq, Cas9 perturbation)23 can be readily reproduced in our CaRPool-seq (3′ scRNA-seq, Cas13d perturbation) data (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). These differentially regulated gene modules were typically associated with genetic programs associated with the differentiation and function of myeloid cells (Extended Data Fig. 8c). To further explore comparisons between human hematopoiesis and our in vitro model system, we integrated our CaRPool-seq dataset with an scRNA-seq reference of hematopoietic progenitors and mature myeloid cells from the Human Cell Atlas and Human Biomolecular Atlas Project24–27, aligning CaRPool-seq THP1 cells to their closest neighbors in the reference dataset, and constructing a joint differentiation trajectory (Fig. 4e). We found that NT control cells localized to early points, but that single perturbations (that is, KDM1A, GFI1, GSE1) pushed cells further down the differentiation trajectory (Fig. 4f), consistent with their role in enhancing leukemic differentiation.

We applied a recent pioneering framework7 that fits a regression model to decompose the observed perturbation responses in doubly perturbed cells as a linear combination of single-gene perturbation responses. The fit and coefficients of this model describe multiple types of genetic interaction, including epistasis, genetic suppression and synergistic relationships. Fitting these models to each of our pairwise perturbations revealed a diversity of genetic interactions, which we broadly clustered into four groups (Fig. 4g). For 33 gene pairs in cluster 1, we saw that each individual gene’s profile contributed equally to the dual perturbation response and the linear model exhibited a strong fit. As a positive control, many of the pairs in this cluster represented perturbations of two proteins in the same complex (that is, MED14/MED24, SUPT16H/SUPT6H), which show similar gene expression responses for singly and doubly perturbed cells (Extended Data Fig. 8d–f). This cluster also represented pairs of proteins residing in separate complexes (MED24/SMARCD1 of mediator and SWI/SNF complexes), which share similar perturbation signatures (Extended Data Fig. 8d). Dual perturbation of KDM1A and the transcriptional repressor GSE1 also fell in this cluster (Extended Data Fig. 8f), consistent with previous work that suggests a cooperative interaction via colocalization at repressed promoters to inhibit myeloid differentiation28.

In cluster 4, we identified genetic interactions where one gene’s effect appeared to dominate over the other. We generally observed that transcriptional responses varied widely when pairing KDM1A knockdown with different chromatin regulators. For example, we found that the EP300-signature appeared more strongly than the KDM1A-signature when combinatorial perturbing both genes (Extended Data Fig. 8g). Dually perturbed cells exhibited higher expression of progenitor genes (that is the progenitor marker AZU1), and reduced expression of differentiated marker genes (that is, myeloid marker S100A4) compared to individual KDM1A perturbation. In contrast, the KDM1A response signature dominated when paired with perturbation of the polycomb repressive complex member RING1 (Extended Data Fig. 8h). Dual perturbation of HDAC3 enhanced the KDM1A transcriptional response signature (Fig. 4h), consistent with our previously described immunophenotypic results for these cells (Fig. 4c). This transcriptional response led dually perturbed cells to be distributed at later segments of our integrated myeloid differentiation trajectory, exhibiting enhanced differentiation compared to either single perturbation (Fig. 4i,j). These findings support and provide a molecular explanation for recent observations that combination therapies of KDM1A antagonist and HDAC inhibitors exhibit an enhanced response29. Moreover, we identified additional synergistic combinations between HDAC3/GFI and HDAC3/GSE1, both of which enhanced the expression of immunophenotypic markers (Fig. 4c), as well as transcriptional differentiation state (Fig. 4j).

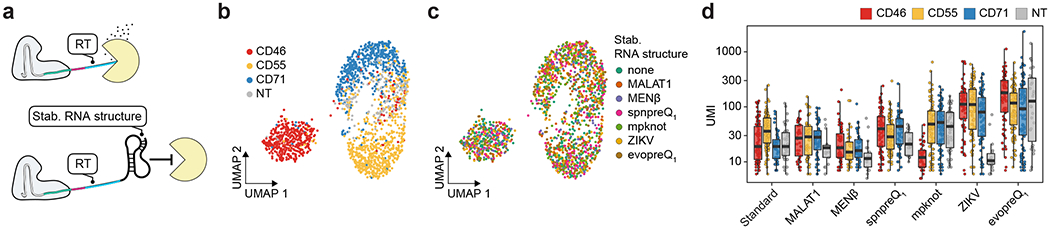

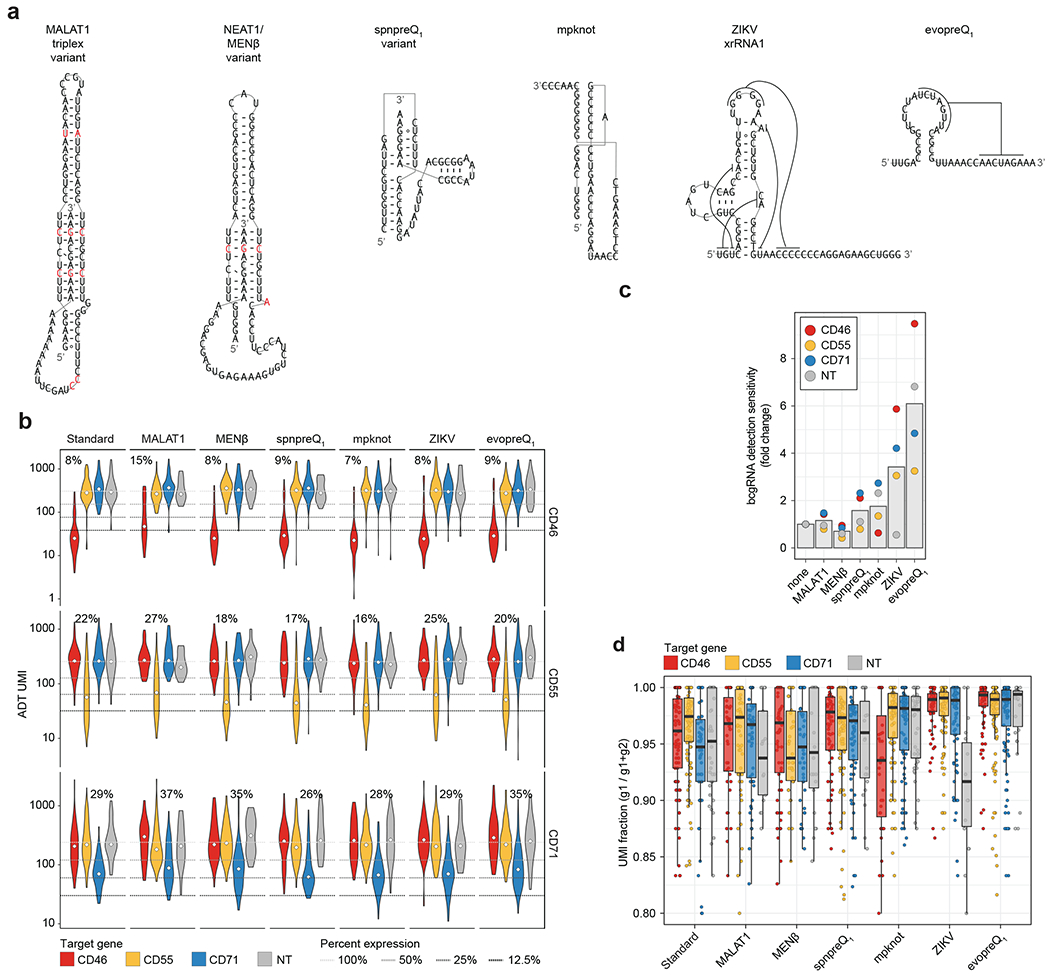

Stable RNA structures improve bcgRNA detection

While our paper was in review, Nelson et al.30 reported that the inclusion of structured RNA motifs on prime editing gRNAs (pegRNAs) led to protection from exonuclease degradation, increased stability, and enhanced efficiency. While we expect that crRNA are typically protected from degradation while complexed with Cas13 (refs. 31,32), the ends of longer bcgRNA molecules may still be accessible and susceptible to degradation. These ends include reverse transcription priming sites that are essential for CaRPool-seq bcgRNA detection. Therefore, we tested the addition of stably structured stabilizing RNA elements at the 3′ end of the bcgRNA to antagonize nucleolytic decay (Fig. 5a). We tested six different structures (Extended Data Fig. 9a), and repeated our benchmarking experiment targeting CD46, CD55 and CD71 in HEK293FT cells. While protein knockdown was indistinguishable for all six structures (Fig. 5b,c and Extended Data Fig. 9b), we found that two elements (Zika virus-derived xrRNA1 dumbbell33; evopreQ1 pseudoknot34) led to a robust increase in bcgRNA unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts (Fig. 5d). In particular, the evopreQ1 pseudoknot element led to a sixfold higher bcgRNA detection UMI counts compared to our initial design (Extended Data Fig. 9c). The increased sensitivity also systematically improved the signal-to-noise ratio to distinguish true bcgRNA UMI counts from spurious secondary bcgRNA UMI counts (Extended Data Fig. 9d). This modified bcgRNA structure therefore further improves the performance of CaRPool-seq, and is recommended for future experiments.

Fig. 5 |. Stable RNA structures improve bcgRNA detection in CaRPool-seq experiments.

a, Model of 3′ exonucleolytic decay of bcgRNAs when embedded in CRISPR–Cas13d ribonucleoprotein complex. RT represents the reverse transcription handle. b, UMAP visualization of single-cell protein expression profiles of CaRPool-seq experiment (n = 1,770 cells). The experiment included four different gRNAs (NT control, CD46, CD55 and CD71) in combination with one out of seven different stabilizing elements. Cells are colored based on the single perturbations they received. c, UMAP visualization of single-cell protein expression profiles of CaRPool-seq experiment as shown in b. Cells are colored based on the structured RNA element they received (no stabilizing element (standard) or one of the six shown in Extended Data Fig. 9a). d, UMI counts for the assigned bcgRNA for each cell separated by target gene and RNA stabilizing element. UMI counts >2,000 are not shown. Boxes indicate the median and interquartile ranges, with whiskers indicating 1.5 times the interquartile range (total cells n = 1,770; conditions n = 28; cell per condition, median n = 63 cells; s.d. n = 30 cells). ZIKV, zika virus.

Discussion

Here, we present CaRPool-seq, a flexible method for performing CRISPR–Cas13 RNA-targeting screens with a single-cell sequencing-based readout. We introduced an optimized strategy to deliver multiple gRNA as part of a single CRISPR array, which is subsequently cleaved into individual crRNAs. We demonstrate that this strategy is well-suited for performing combinatorial perturbations, whose identity is encoded in a single barcode that can be reliably detected alongside multiple molecule modalities including scRNA-seq and CITE-seq.

Through benchmarking, we show that CaRPool-seq is more efficient and accurate when assigning multiple perturbations in single cells when compared to Cas9-based technologies. Even with individual perturbations, the user can still benefit from CaRPool-seq. In particular, as an RNA-targeting enzyme, Cas13d can be uniquely applied to target specific RNA isoforms, or even circular, enhancer or antisense RNA molecules. RNA-directed approaches may also be optimal when targeting a single member of a local gene cluster, where alternative KRAB-mediated repressive strategies may ‘spread’ and introduce off-target effects35. CaRPool-seq can profile additional cellular modalities such as cell surface protein levels and, in the future, can be extended to additional molecular modalities including intracellular protein levels and chromatin accessibility. Moreover, the strategy of introducing multiple perturbations through cleavable arrays is extendable to other CRISPR systems, including Cas12 (ref. 36) and Cas7-11 (ref. 37), and represent promising extensions of this work. And as combinatorial screens scale rapidly, we note that CaRPool-seq is compatible with pioneering approaches for targeted scRNA-seq, including hybridization-based 10X Targeted Gene Expression Panels6 or multiplexing PCR-based approaches38.

There are current limitations with CaRPool-seq that may be overcome by future advances. For example, RNA-targeting CRISPR proteins cannot currently activate gene expression through transcription or translation in mammalian cells39. Additionally, our work suggests a pooled cloning strategy for medium-sized CaRPool-seq CRISPR arrays; however, further optimizations may be required for long arrays with very large numbers of targeting gRNAs. Lastly, while we did not observe direct or indirect evidence for RfxCas13d’s promiscuous collateral activity in our CaRPool-seq experiments, other RNA-targeting CRISPR effectors37,40,41 may represent an alternative for future experiments.

Combinatorial screens have the potential to shed substantial new light on the structure of genetic regulatory networks, and also to identify combinatorial perturbations that achieve desirable cellular phenotypes. Our CaRPool-seq analysis of AML differentiation regulators benefited from recently developed computational frameworks to identify genetic interactions from multiplexed perturbation screens, and these types of data will be valuable resources for systematic reconstruction of complex pathways and cell circuits. Moreover, our identification of combinatorial perturbations that enhanced AML differentiation phenotypes was consistent with previous identification of efficacious multi-drug therapies, suggesting that future experiments may help to nominate candidates for combined drug treatments. We conclude that CaRPool-seq represents a powerful addition to the growing toolbox of methods for multiplexed single-cell perturbations.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01705-x.

Methods

Pooled Cas13d library design and cloning

We design two libraries for pooled cloning, one to identify genes that lead to THP1 cell differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 6) and one for combinatorial targeting with CaRPool-seq (Fig. 4).

First, we designed a RfxCas13d gRNAs library for single gRNA expression targeting 439 individual genes. We selected 240 genes that led to CD11b or CD14 upregulation in Cas9 screens23, in addition to 199 control genes in TLR4-signaling. We selected the transcript with the highest isoform expression (CCLE, https://sites.broadinstitute.org/ccle/datasets) per gene and designed gRNAs using our Cas13design algorithm11. For each gene, we selected ten gRNAs from efficacy quartile Q4 (or Q3), spread along the coding region. Selected gRNAs had no secondary target sites with 0–2 mismatches to the cognate site42. In total, we designed 4,390 gRNAs and 410 NT control gRNAs (>3 mismatches to hg19-annotated transcripts). Library cloning has been described before11. In brief, pooled oligonucleotides (Twist) were amplified using 8× PCR reactions with eight amplification cycles using direct repeat-specific forward primer (Supplementary Table 2). The amplicon was Gibson-cloned into pLentiRNAGuide_001 and pLentiRNAGuide_002 (Addgene nos. 138150 and138151). Complete library representation with minimal bias (90th percentile/10th percentile crRNA read ratio of 1.8 for both libraries) was verified by Illumina sequencing (MiSeq).

For the CaRPool-seq library, we manually inspected all gRNA enrichments from the pooled screen library described above. For each target genes, we picked the two most enriched (depleted for CD14/ATXN7L3) gRNAs avoiding overlapping gRNAs. For each gene, we paired the two gRNAs with an NT gRNA (n = 28 single perturbations, n = 56 arrays). For 17 genes, we designed all pairwise combinations (n = 136 gene pairs, n = 272 arrays). For nine genes we designed a subset of possible gene pairs within the same complex (n = 22 gene pairs, n = 44 arrays). We added 13 NT control arrays. In total, we design 385 arrays with 186 single or double perturbations, each represented by two independent technical replicate gRNA combinations. For the bcgRNAs, we designed random 15mer sequences with hamming distance greater than four to one another. We balanced the relative CRISPR array abundance by the negative effect on cell proliferation of the targeted genes and increased the number of array copies in the pool to minimize dropout in the CaRPool-seq experiment. The oligos for synthesis were designed in the following way:

PCR-handle::BsmBI-site::gRNA1::DR::gRNA2::LguI-bridge::barcode::BsmBI-site::PCR-handle

Pooled oligonucleotides (Twist, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) wer amplified using Pfu-Ultra-II following the manufacturer’s recommendation using 1 μl of enzyme and 20 ng (1 ng μl−1) of the oligo pool in a 50 μl reaction 95 °C/2 min, 5× (95 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 15 s), 72 °C for 3 min). The amplicon was 2× solid phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) purified, followed by BsmBI-digestion and additional 2× SPRI cleanup. All of the product was ligated into BsmBI-digested pLentiRNAGuide_003 (without evopreQ1 sequence element) using T7-DNA ligase and cloned as described in ref. 11 with >1,000 colonies per construct. The resulting plasmid pool was digested with LguI to enable ligation of the third direct repeat and small RNA-handle to complete the bcgRNA and CRISPR array. The LguI insert (Supplementary Table 2) was cloned into pLentiRNAGuide_001, digested with LguI and gel-purified (2% eGel). Complete library representation with minimal bias (90th percentile/10th percentile crRNA read ratio 2.6/4.8), and correct gene pair to bcgRNA linkage (>94%) was verified by Illumina sequencing (MiSeq). During library cloning, we noticed two critical details: alternative polymerase KAPA and Q5 can lead to a stronger bias in relative array abundance. Further, reducing the number of PCR cycles with increased oligo pool input amounts can decrease bcgRNA reassortment. Last, while we chose a two-step cloning strategy, a single-step strategy may yield similar results. pLentiRNAGuide_003 has been deposited to Addgene (no. 192505).

Pooled CRISPR screening

Pooled Cas13d screens have been performed as described before in ref. 11, with minor modifications. Cas13d expression was induced after THP1 cells were fully selected (1 μg ml−1 doxycycline). Growth medium with fresh puromycin, blasticidin and doxycycline was replenished every 2–4 days, and cells were split as needed always maintaining a guide representation of >1,000×.

For the single gRNA pooled screen, we collected a 1,000× representation at 7 and roughly 14 days post-Cas13d induction and before sorting. After 2 weeks (13–16 days) we stained 15 million cells (roughly 3,000× representation), using FcX-blocking buffer (BioLegend no. 422302; 10 min at room temperature) and followed by either CD11b (BioLegend clone ICRF44 no. 301322, 4 μl per 1 × 106 cells per 100 μl or CD14 (BioLegend clone HCD14 no. 325608, 4 μl per 1 × 106 cells per 100 μl staining (30 min at 4 °C), and finally resuspending cells on PBS with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Sigma no. D9542, 0.4 μg ml−1) to detect any apoptotic or dead cells. We sorted the cells (Sony SH800) based on their signal intensities (CD11b or CD14: lowest 10–15% and highest 10–15%). Cells were PBS-washed and frozen at −80 °C until sequencing library preparation. In total, we prepared four independent transductions (two multiplicities of infection (MOI) and two alternative direct repeats), performed CD14 sorts for all four transduction replicates, and CD11b sorts for three transduction replicates collecting 1 × 106 to 1.5 × 106 cells per bin.

For the combinatorial perturbation pooled screen, we performed three transduction replicates (MOI 0.13–0.20). Eight days post-Cas13d induction, we collected an input representation (>1,000× coverage) and stained 20–30 million cells with FcX-blocking, CD11b and DAPI as described above. Cells were CD11b-sorted (lowest 15% and highest 15% signal intensity). Cells were PBS-washed and frozen at −80 °C until sequencing library preparation. Library preparations for the single gRNA pooled screen were done as described before11. For the combinatorial targeting pooled screen, we adopted a PCR strategy similar to the CaRPool-seq bcgRNA readout. Pooled screen readout PCR1 remained unchanged. In PCR2, we amplified the 15 basepair (bp) barcode sequence using a soluble Nextera-Read1-CS1 feature capture primer including an optional 28 randomized bases mirroring UMI and cell barcode, and RPIx Read2 i7 index primer. The amplicon was completed in PCR3 using Feature SI primer 2 (10X Genomics) and P7 primer.

Pooled CRISPR screen analysis

Raw reads were demultiplexed based on Illumina i7 barcodes using bcl2fastq and, if applicable, by their custom in-read barcode using a custom python script. For the single gRNA pooled screen, read1 sequencing reads were trimmed to the expected gRNA length by searching for known anchor sequences relative to the guide sequence using a custom python script (https://github.com/hwessels/Cas13). For the combinatorial pooled screen, we extracted the first 15 bases in read2. For the single gRNA pooled screen, we collapsed (FASTX-Toolkit v.0.0.14) processed reads to count duplicates followed by string-match intersection with the reference to retain only perfectly matching alignments (average mapping rate 82.3%, median gRNA count 167). For the combinatorial pooled screen, preprocessed reads were aligned to the barcode reference using bowtie43 (v.1.1.2) with parameters -v 1 -m 1–best –strata (average mapping rate 97%; median barcode read count 635; one barcode was not detected in input samples). For each dataset, raw counts were normalized using a median of ratios method as in DESeq2 (ref. 44) and batch corrected using combat implemented in SVA (v.3.34.0)45. gRNA and bcgRNA enrichments were calculated building the count ratios between a sorting bin or timepoint and the indicated reference sample followed by log2-transformation (log2FC). For every gRNA or bcgRNA, we considered the mean log2FC across replicates. For the single gRNA pooled screen, we used the four best performing gRNAs per target gene to calculate the mean log2FC, where we determined best as either highest or lowest dependent on the sign of the mean enrichment across all ten gRNAs. As we have previously described11, we noticed that log2FC enrichments were generally more pronounced in samples using the enhanced direct repeat. Consistency between replicates and selected gRNAs was estimated using Robust Rank Aggregation (v.1.1)46. For the combinatorial pooled screen, we calculated the mean of both replicate arrays per gene pair. We noticed GFI1 g2 did not lead to strong effects in the pooled screen and in the CaRPool-seq experiment. The technical replicate arrays including GFI1 g2 were removed in all analyses. Enrichments are available in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 (P values derived from Robust Rank Aggregation).

Direct capture Perturb-seq

Monoclonal CRISPR–Cas effector protein-expressing cell lines (Cas9-nuclease, KRAB–dCas9, KRAB–dCas9–MeCP2) were infected with one of six sgRNA pools (KO-1, KO-2, KO-3 or CRISPRi-1, CRISPRi-2 and CRISPRi-3) (Supplementary Table 1), providing 1–3 sgRNAs in a single vector and a total of nine cell line pool combinations. Cell survival after selection ranged between 1.7 and 5.5% (MOI < 0.1) assuring a high single integration probability. Viral titers were confirmed by measuring the fraction of BFP-positive cells for pools that have received vectors carrying 2+ sgRNAs using flow cytometry. Cells were passaged every 2–3 days (replenishing puromycin and blasticidin at each split) maintaining high sgRNA representation (>1,000× coverage). We confirmed that >98% of cells were BFP-positive before the 10X experiment. We performed 10X (Chromium Single Cell 3′ Gene Expression v.3 with Feature Barcoding technology for CRISPR screening, nos. 1000074, 1000075 and 1000079) 12 days posttransduction. Cells were stained with a pool of five TotalSeq-A antibodies (0.75 μg per antibody per 2 × 106 cells) (Supplementary Table 6) following the CITE-seq protocol12. In addition, we used Cell hashing22 (Supplementary Table 7) to track the nine cell line pool combinations. Before the run, cell viability was determined (≥96%). We ran one 10X lane, leveraging our hashed experimental design loading 38,600 cells. mRNA, sgRNA feature, hashtags (hashtag-derived oligos, HTOs), protein (Antibody-derived oligos, ADTs) libraries were constructed by following 10X Genomics Cell hashing and CITE-seq protocols12,22. All libraries were sequenced together on one NextSeq 75 cycle high-output run.

Direct capture Perturb-seq analysis

Gene expression data was mapped to the hg38 (ensembl v.97) genome reference using Cellranger (v.3.0.1). Guide RNA reads were mapped simultaneously to a sgRNA feature reference (Supplementary Table 1). Before feature mapping, we performed 5′ adapter trimming using cutadapt to account for varying lengths of poly-G tracks five prime to the sgRNA feature (first -g AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACAT -O 5; then -O 1 -e 0 -g XGGGGGGGGGG) and trimmed the resulting reads to a length of 18 bases. We used CITE-seq-count package (v.1.4.2) for HTO and ADT quantification. Count matrices were then used as input into the Seurat R package (v.4.0)47 to perform downstream analyses. We detected 16,842 cells. HTO and sgRNA counts were normalized using the centered log-ratio transformation approach (margin of 2). To assign experimental conditions and remove cell doublets, we used the HTODemux function in Seurat, with default parameters.

For sgRNA assignment, we customized HTODemux to return identities of second and third sgRNA without changing the underlying modeling approach. We flagged cells with an incorrect number of expected sgRNAs based on the HTO pool assignment. Furthermore, we flagged cells with an unexpected combination of sgRNAs not present in the sgRNA pool used to transduce the cells.

For the analysis shown in Fig. 3, we only retained cells with the correct sgRNA numbers and identities. ADT counts were log-normalized, before running ScaleData (do.scale=FALSE, vars. to.regress=Perturb-Seq.approach). PCA was performed on normalized ADT counts using all five features, followed by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) dimensional reduction using four dimensions. To compare target knockdown across Perturb-seq approaches for NT cell and cells that received all three (s)gRNAs (CD46, CD55, CD71), we normalized cellular ADT counts using median of ratios across ADT features that were not targeted (CD29, CD56) to derive a scaling factor per cell, and divided the normalized ADT counts by the mean ADT counts in NT cells for each Perturb-seq approach.

CaRPool-seq experiments

We transduced and treated Cas13d-NLS expressing HEK293FT, NIH/3T3 or THP1 cells as described in the Supplementary Information. In the species mixing, we used a pool of three bcgRNAs per species together with NT gRNAs. The HEK293FT CaRPool-seq experiment included 29 CRISPR arrays (Supplementary Table 1) barcoding a diverse set of array configurations around four gRNAs that allowed us to assess gRNA positioning within the CRISPR array, effects of the relative gRNA amount per cell and combinatorial targeting of multiple RNA transcripts. CaRPool-seq species mixing and CaRPool-seq were conducted simultaneously in one lane of 10X Genomics 3′ kit. CaRPool-seq was performed on THP1 cells 5 days post-Cas13d induction (1 μg ml−1 Doxycycline) using four lanes of a 10X Genomics 3′ kit. THP1 CaRPool-seq library design and cloning were described above. Before the runs, cell viability was determined ≥95% for each experiment.

The HEK293FT CaRPool-seq experiment was stained with a pool of five TotalSeq-A antibodies (0.75 μg per antibody per 2 × 106 cells) (Supplementary Table 6) as following the CITE-seq protocol12. Similarly, THP1 cells were first treated with FcX-blocking buffer (BioLegend no. 422302, 10 min at room temperature), before staining cells with a pool of 22 TotalSeq-A antibodies (Supplementary Table 6). To keep track of the experiment identity and identify multiplets, samples were hashed (subsequent to CITE-seq antibody staining) (Supplementary Table 7) following the Cell Hashing protocol22. mRNA, hashtags (HTOs), protein (Antibody-derived oligos, ADTs) libraries were constructed by following 10X Genomics Cell hashing and CITE-seq protocols12,22.

Species mixing and HEK293FT CaRPool-seq experiment libraries were sequenced together on one NextSeq 75 cycle high-output run. THP1 CaRPool-seq libraries were sequenced on NovaSeq6000 using the XP S4 2 × 100 v.1.5 workflow. Sequencing reads coming from the mRNA library were mapped to a joined genome reference of hg38 (ensemble v.97) and mm10 using the Cellranger Software (v.3.0.1), or to hg38 using Cellranger v.6.0.0 for the THP1 experiment. bcgRNA library reads were mapped simultaneously to a barcode reference (Supplementary Table 1) using Cellranger. To generate count matrices for HTO and ADT libraries, the CITE-seq-count package (v.1.4.2) was used (https://github.com/Hoohm/CITE-seq-Count). Count matrices were then used as input into the Seurat R package (v.4.0)47 to perform all downstream analyses.

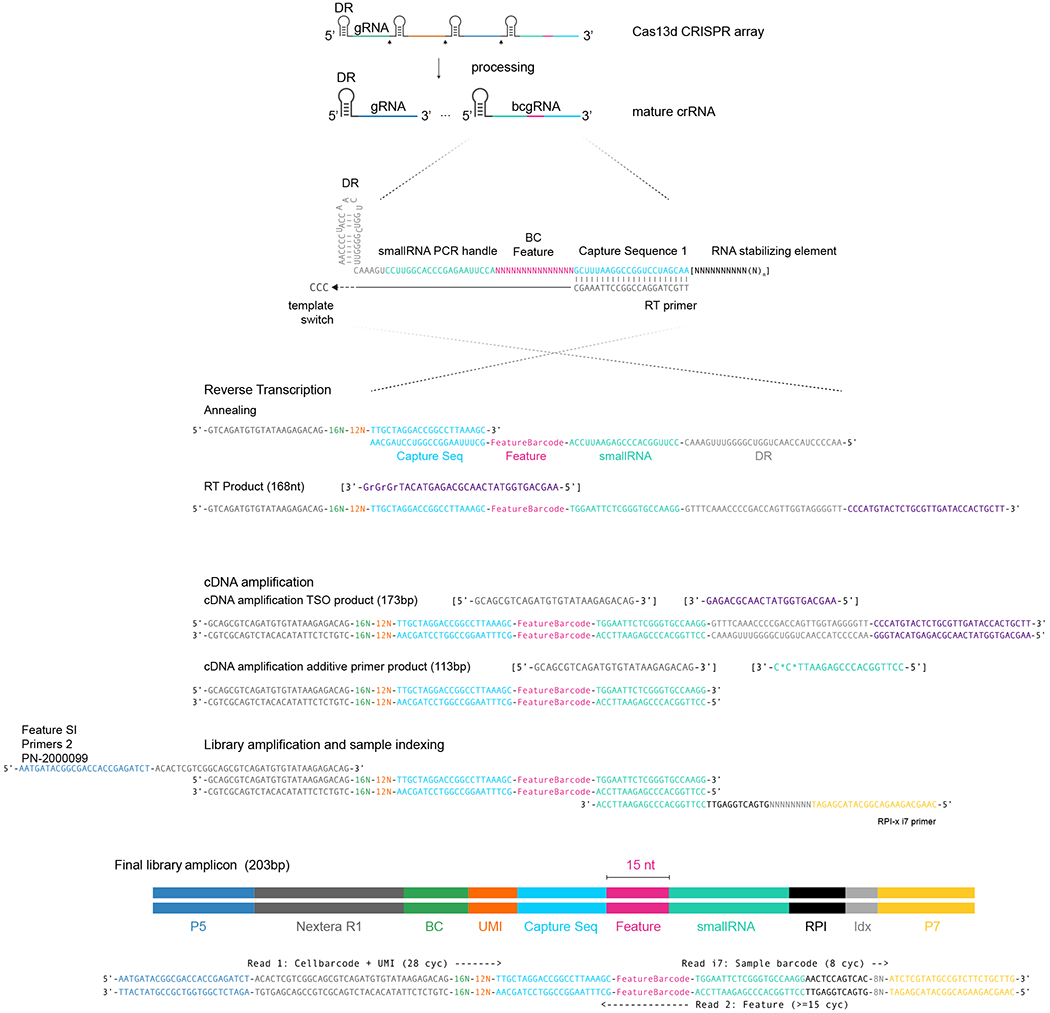

CaRPool-seq library preparation

We used Cas13 CRISPR array configurations of type X (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 2). Specifically, the bcgRNA was placed in the last array position and entailed a spacer sequence composed of a five-prime Illumina small RNA PCR handle, a 15mer barcode and a three-prime capture sequence 1 (CS1) compatible with 10X Genomics feature barcoding. This composition allowed the specific amplification of a bcgRNA amplicon with a unique combination of forward and reverse primers. Moreover, usage of the Illumina 5′ PCR handle allows for efficient sequencing of the bcgRNA amplicon with the first base of read2 being the first barcode base. In our last experiment (Fig. 5), we added structured RNA elements 3′ to the CS1 sequence.

CaRPool-seq experiments were conducted using the 10X Genomics 3′ kit (Chromium Single Cell 3′ Gene Expression v3 with feature barcoding technology for CRISPR screening, nos. 1000074, 1000075 and 1000079). Library construction for bcgRNA derived oligos is outlined in Extended Data Fig. 2 and largely followed 10X Genomics user guide CG000184 Rev C with some modifications. Specifically, we eluted the GEM-RT in 33 μl and added 2 μl containing 0.4 μM ADT additive primer (for bcgRNAs and ADTs) and 0.2 μM HTO additive primer before complementary DNA amplification. The cDNA was purified using 0.6× SPRI cleanup for mRNA fraction. The supernatant containing ADT, HTO and bcgRNA cDNA was purified by adding another 1.4× SPRI (0.6 + 1.4 = 2× SPRI) followed by a second 2× SPRI cleanup. The purified short fragments were split into three pools (for example, 3 × 20 μl). One pool each was used for HTO and ADT library construction as described before12,22. Half of the remaining pool (10 μl) was used to construct the bcgRNA library using two PCR recipes. PCR1 adds Illumina P5 and P7 handles to the bcgRNA amplicon (100 μl of PCR1:50 μl of 2× KAPA Hifi PCR Mastermix, up to 45 μl of bcgRNA PCR template, 2.5 μl of Feature SI Primers 210 μM, 2.5 μl of TruSeq Small-RNA RPIx primer (containing i7 index) 10 μM;95 °C 3 min, 12× (95 °C 20 s, 60 °C 8 s, 72 °C 8 s), 72 °C 1 min). The 1.6× SPRI-purified PCR1 product was amplified in PCR2 (100 μl: 50 μl of 2× KAPA Hifi PCR Mastermix, up to 45 μl of PCR1 product, 2.5 μl of P5 primer 10 μM, 2.5 μl of P7 primer 10 μM; 95 °C 3 min, 4× (95 °C 20 s, 60 °C 8 s, 72 °C 8 s), 72 °C 1 min). The final bcgRNA amplicon (203 bp) can be sequenced with standard Illumina sequencing primers (≥28 cycles read1 and ≥15 cycles read2) (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3a).

CaRPool-seq data analysis

Cells from species-mixing and HEK293FT CaRPool-seq experiments were processed together. Cells with <2,500 UMI were removed. HTO and bcgRNA counts were normalized using the centered log-ratio transformation approach (margin of 2). We used HTODemux to identify cell doublets and assign experimental conditions. Only human cells were hashed, with mouse NIH/3T3 cells being the only cell population without a hashtag. We removed all hashing doublets within the CaRPool-CITE-seq experiment (HTO-01 to HTO-08) and to human cells in the species-mixing experiment (HTO-10). In addition, we removed all cells labeled with a single HTO-01 to HTO-08 if the fraction of mouse reads was >10%, and cells without any HTO if not at least 10% mouse reads were present. Like this, we removed all doublets between CaRPool-seq species mixing and CaRPool-CITE-seq experiments while retaining potential collisions/doublets within the species-mixing experiment. At this point, the experiment was split into two separate objects. For the species-mixing experiment, we determined species identity by quantifying the fraction of human reads for RNA and for the species-specific bcgRNAs (human >0.9, mouse <0.1, collision 0.9 to 0.1). For the HEK293FT CaRPool-CITE-seq experiment RNA counts were log-normalized using the standard Seurat workflow after removing all mouse features and RNA counts. bcgRNA identity was determined using MultiSeqDemux (autoThresh=T). Cells without a bcgRNA assigned and cells with multiple bcgRNA assignments were removed. Differential expression analyses were done using FindMarkers (Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test, pseudocount.use of 1 × 10−4). We converted log2 fold changes to percent knockdown for each target gene in each of the 26 targeting conditions and took the mean to calculated the average target knockdown,

For the THP1 experiment we detected 52,496 single cells (nFeature_RNA > 1,000, nFeature_RNA < 8,000, percent.mt < 20) after HTO demultiplexing using HTOdemux as described above. Model-based bcgRNA assignments (HTODemux or MultiSeqDemux) did not yield satisfying results supported by the observed phenotypic changes, likely due to model limitations imposed by the high number of bcgRNA features. Instead, we assigned bcgRNAs to single cells by applying the following rules: We compared UMI counts for the bcgRNA with the highest UMI count (g1) to, if present, the second detected bcgRNA (g2). bcgRNA counts for g2 may derive from spurious counts arising from library preparation, or from integration of more than one viral element (bcgRNA multiplet). We considered cells with g1 < 5 as negative. We assigned g1 if: (1) g1 = (5–9) and g2 = (0–1) or (2) g1 > 9 and g1/(g1 + g2) > 0.8 and g2 < 11. All other cells were considered bcgRNA multiplets. We assigned 31,308 with a single bcgRNA. Comparing differential gene expression results for technical replicates embedded in the CaRPool-seq library, we noticed GFI1 g2 did not lead to upregulation of CD11b ADT or upregulation of the expected gene expression signature. We removed all cells with GFI1 g2 (n = 601).

Changes in cell surface protein ADT levels for gene pair or individual CRISPR array were calculated using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test in FindMarkers relative to NT control cells. Changes were determined by repeating the differential expression analysis ten times with ≤30 randomly samples cells per cell group to account for differing numbers of cells followed by averaging. We compared differential CD11b expression between single and dual perturbations by comparing the log2-tranformed fold changes of dually perturbed cells to the log2-transformed mean fold changes of the two single-gene perturbations.

Cas13d gRNA off-target evaluation

To identify potential Cas13d gRNA off-target binding sites we aligned gRNAs to the human transcriptome (GRCh38 cdna.all and noncoding RNA from emsembl release 97) using blastn (v.2.6.0) (megablast) with the following parameters (-strand minus -max_target_seqs 10,000 -evalue 10,000 -word_size 5 -perc_identity 0.7). Second, candidates were further filtered to match with at least 17 bases, as shorter matches do not lead to target knockdown and show a blastn e.value of <100. In Extended Data Fig. 4a, we demonstrate that despite the potential for off-target binding, we do not observe transcriptomic perturbation for these genes.

Cas13d collateral activity was evaluated by comparing expression levels of mitochondrial genes15 in cells expressing targeting gRNAs versus NT gRNAs using FindMarkers (Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test, pseudocount. use 1 × 10−4). To assess differences in cell fitness, we classified single-cell transcriptomes into gene expression programs usually observed at different cell cycle stages (Seurat’s CellCycleScoring), and compared the distribution of cells per cell cycle stages between groups of cells.

Modeling of genetic interactions in single-cell data

To decompose transcriptomic profiles of double perturbation, we used a linear regression model as previously introduced7 and implemented it in R. First, we z-scaled the log-normalized gene expression counts for all cells with respect to the mean and standard deviation of the control group (NT cells). In this way, we have subtracted the baseline expression profiles from each cell and can directly compare the deviation from each perturbation to NT conditions. Next, we grouped cells by gene pair and calculated pseudobulk z-scaled profiles (single perturbations (a, b), and double perturbation (ab)) by calculating the mean across cells for each feature. The average NT-cell profile returns a vector of all zeros. We generated average profiles for 1,530 genes with an average UMI count >0.5. We included gene pairs when all cell groups were represented by at least 25 cells (Examples in Fig. 4g and Extended Data Fig. 8d–h).

As previously introduced7, we model the average z-scale profiles using:

with δa and δb being the pseudobulk z-scaled profile for cells assigned to single perturbations a and b, repectively, while δab is the pseudobulk z-scaled profile for cells assigned to double perturbation ab. c1 and c2 are constants fitted to the data indicating the relative weight of δa and δb profiles. The vector ϵ collects the residuals to the model fit. In our plots, a is the first gene in the gene pair and b is the second gene. c1 corresponds to a, and c2 to b.

We implemented the previously introduced model-fitting procedure7, using the rlm function from the MASS package (v.7.3-58.1), and extracted the mean coefficients (c1 and c2) and residual error ϵ. We collected six measures to evaluate the fit as described before7 (dcor function in energy package v.1.7-10):

Model fit: dcor (c1a + c2a, ab)

Dominance: |log10 (c1/c2)|

Magnitude: (c12 + c22)1/2

Similarity of single to double profiles: dcor ((a,b), ab)

Similarity of single profiles: dcor (a,b)

Equality of contribution: min (dcor (a,ab), dcor (b,ab))/max (dcor (a,ab), dcor (b,ab))

Each feature and its interpretation are described in detail in ref. 7. Features were scaled (margin of 2) before hierarchal clustering (dist, euclidean; methods, ward) to generate a dendrogram, shown in Fig. 4g. For clarity, the heatmap in Fig. 4g shows unscaled values.

The example interactions shown in Fig. 4h and Extended Data Fig. 8d–h depict the union of top 20 differentially expressed genes for each cell group (a, ab) relative to NT cells (selected by P value) derived using the Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test in FindMarkers. Model prediction and residuals are derived from the modeling approach described above. The color scale represents the average z-score normalized expression per gene pair.

Extended Data

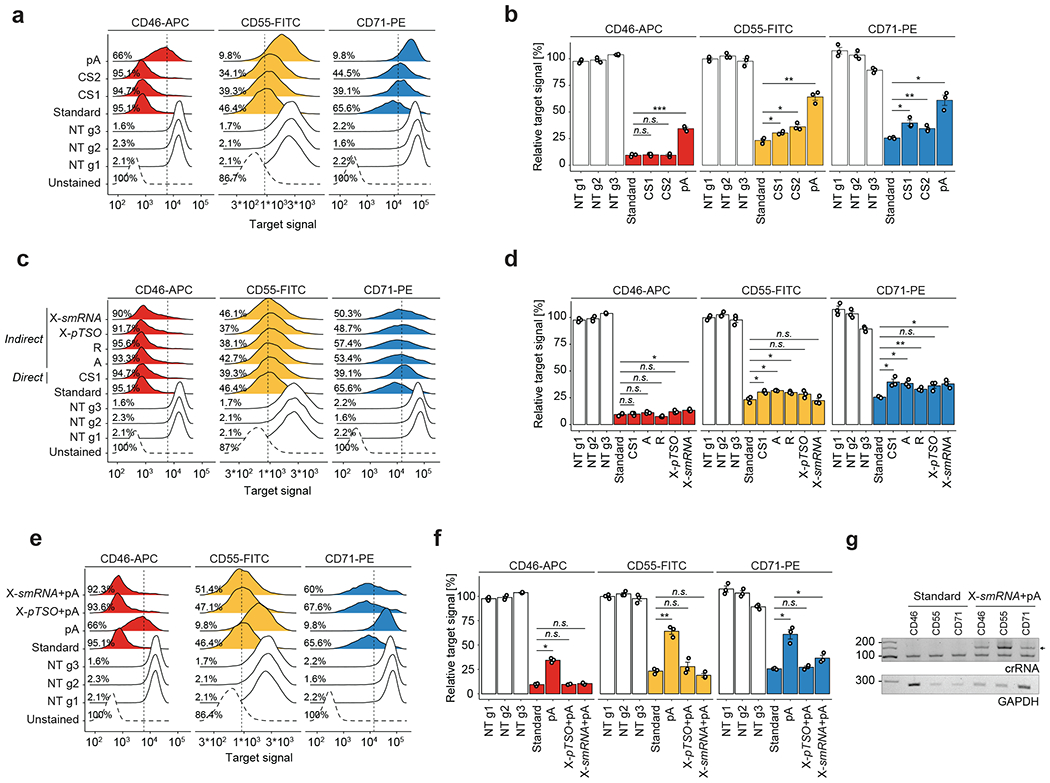

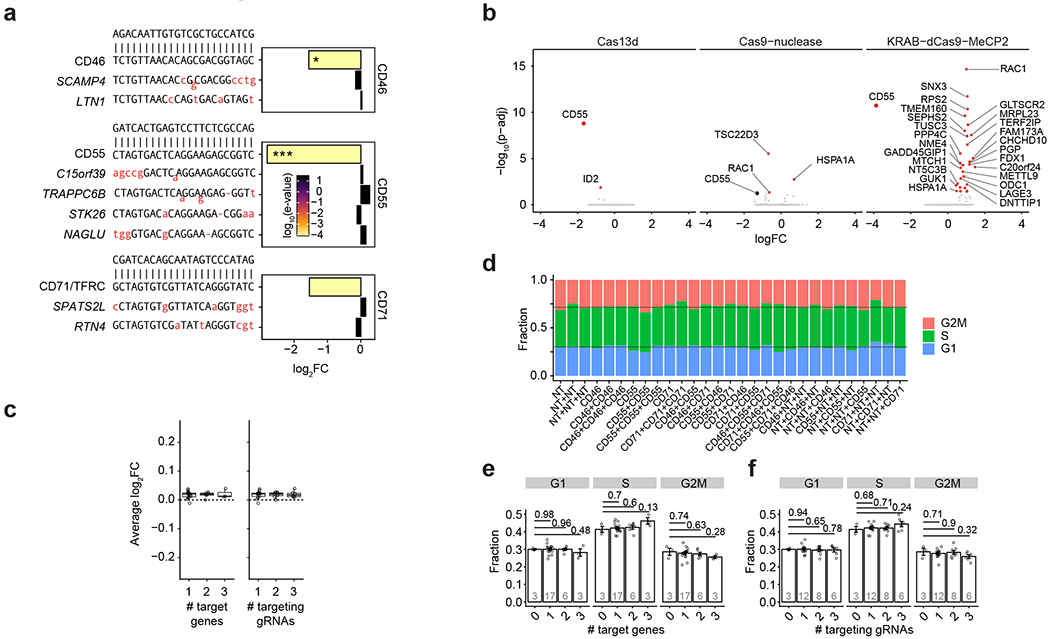

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Direct and indirect Cas13 guide RNA capture allow for robust target knockdown.

a) Density plots showing the CD46-APC, CD55-FITC and CD71-PE flow cytometry signal upon Cas13d-mediated knockdown with either regular gRNAs or a direct capture gRNA with one of three reverse transcription handles (pA(30) = polyA-tail of length 30, CS1 = 10x Genomics Capture Sequence 1, CS2 = 10x Genomics Capture Sequence 2, NT = non-targeting). Vertical lines mark the threshold for CD-protein negative cells (2nd percentile of NT cell populations), indicating the percent negative cells for one replicate experiment. Importantly, the Cas13-mediated function shows a unimodal response, suggesting limited cell-to-cell differences in target gene knockdown. N > 5000 cells examined per sample. Shown is one representative replicate. b) Summary analysis of biological replicate experiments (n = 3) as shown in (a). Y-axis shows the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) relative to the average of all NT cell populations. Direct capture constructs with CS1 or CS2 enable strong knockdown for CD46, but reduced knockdown for CD55 and CD71. Direct capture with pA-handle shows strongly reduced knockdown efficiency compared to regular gRNAs (standard condition). Two-sided t-test with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. Error bars depict SEM. c) Density plots showing the CD46-APC, CD55-FITC, and CD71-PE signal upon Cas13d-mediated knockdown with either regular gRNAs, a direct capture gRNA, or indirect capture construct of types A, R, and X as shown in Fig. 1a. CS1 was used in all constructs with RT-handle. Type X was used with either a partial TSO (pTSO) PCR priming site or an Illumina smallRNA PCR-handle sequence. Vertical lines mark the threshold for CD-protein negative cells, indicating the percent negative cells for one replicate experiment. N > 5000 cells examined per sample. Shown is one representative replicate. d) Summary analysis of biological replicate experiments (n = 3) as shown in (c). Y-axis shows the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) relative to the average of all NT cell populations. Indirect capture constructs show strong target gene knockdown similar to regular gRNAs (standard condition) for all three target genes. The slight reduction in targeting efficiency in indirect guide capture may be explained by CRISPR array processing constraints. Two-sided t-test with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. Error bars depict SEM. e) Density plots showing the CD46-APC, CD55-FITC, and CD71-PE signal upon Cas13d-mediated knockdown with either regular gRNAs, a direct capture gRNA, or indirect capture construct of type X. Here, comparing the effect and placement of a polyA-tail RT-handle. pA indicates direct capture construct with polyA-tail. Type X was used with either a pTSO or smallRNA PCR-handle sequence. Vertical lines mark the threshold for CD-protein negative cells, indicating the percent negative cells for one replicate experiment. N > 5000 cells examined per sample. Shown is one representative replicate. f) Summary analysis of biological replicate experiments (n = 3) as shown in (e). Y-axis shows the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) relative to the average of all NT cell populations. Indirect capture constructs show strong target gene knockdown like regular gRNAs (standard condition) for all three target genes. Target knockdown with direct capture through a polyA-tail sequence is limited. Two-sided t-test with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. Error bars depict SEM. g) PCR amplicons of reverse-transcribed crRNAs from lentivirally infected cells used in (e) showing one representative experiment. Indirect capture of Type-X crRNAs with smallRNA PCR-handle and polyA-tail (arrow) allowed for reverse transcription and amplification. These results show that indirect gRNA capture can be facilitated with polyA-tail capture as an alternative to CS1-based capture.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |.

bcgRNA capture scheme adapted from 10x Genomics Feature Barcoding technology.

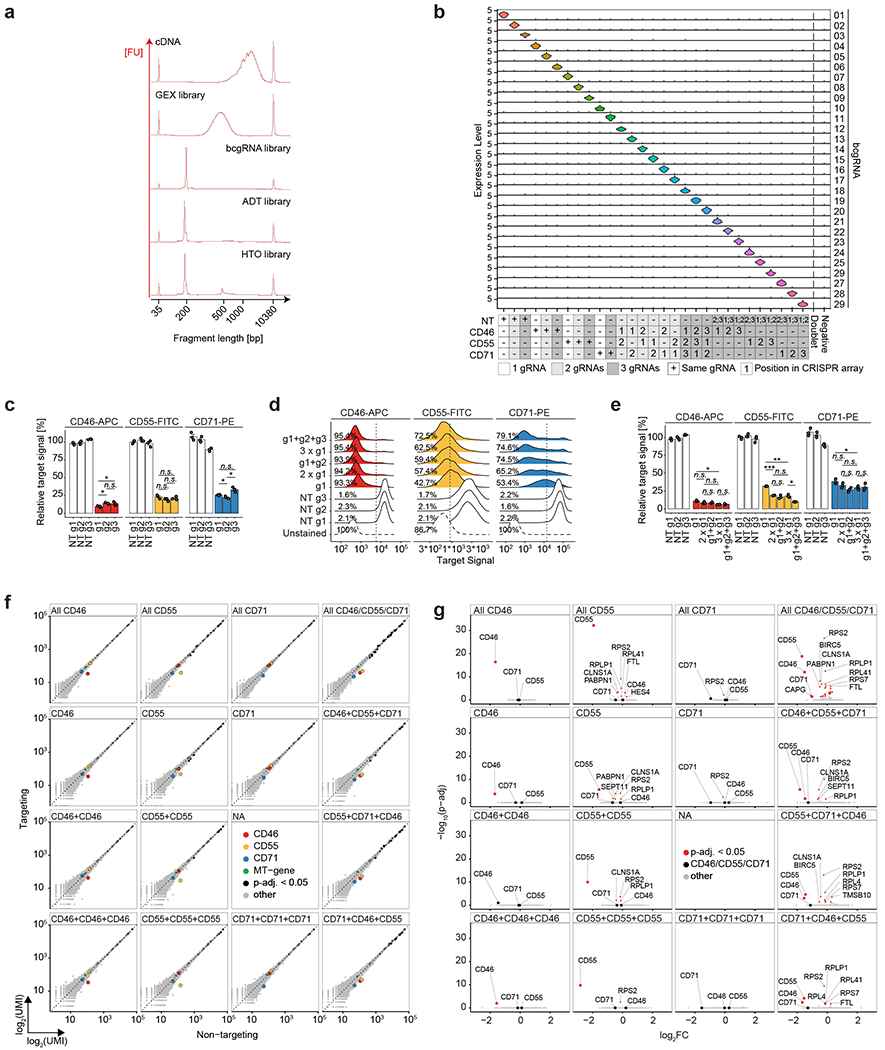

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. CaRPool-seq enables efficient bcgRNA capture and specific target RNA knockdown.

a) Representative BioAnalyzer traces of cDNA and four jointly assayed modalities (GEX = gene expression, bcgRNA = barcode guide RNA, ADT = antibody derived tags, HTO = hashtag oligonucleotides). b) Stacked violin plot showing normalized bcgRNA UMI counts for cells grouped by assigned CRISPR array [total cells n = 9,355, cells with single bcgRNA n = 6,986, (74.7%), n = 29 single bcgRNA conditions; median number of cells 269 per condition, s.d. 97 cells]. c) Bar plots depicting CD46-APC, CD55-FITC, and CD71-PE signal upon Cas13d-mediated knockdown with three alternative gRNAs per target gene relative to the mean of three NT controls measured by flow cytometry. Y-axis shows the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) relative to the average of all NT cell populations. Two-sided t-test with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. (N = 3 replicate experiments; error bars depict SEM). Guide RNA g1 was used in CaRPool-seq experiments. Guide RNAs g2 and g3 are used in figures (d) and (e). d) Density plots showing the CD46-APC, CD55-FITC, and CD71-PE signal upon Cas13d-mediated knockdown with either 1, 2, or 3 copies of the same gRNA (g1) per CRISPR array or 2 and 3 alternative gRNAs (g2, g3). Vertical lines mark the threshold (2nd percentile of combined NT conditions) for CD-protein negative cells, indicating the percent negative cells for one replicate experiment. N > 5000 cells examined per sample. Shown is one representative replicate. e) Summary analysis of biological replicate experiments (n = 3) as shown in (d). Y-axis shows the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) relative to the average of all NT cell populations. The Analysis suggests that target gene knockdown differences between the number of gRNAs per array are more pronounced than differences between gRNA identities with the same total gRNA count, given that gRNA efficiencies are comparable as shown in (c). CRISPR arrays encoding multiple gRNAs against the same target may be used to further enhance target knockdown. Two-sided t-test with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. Error bars depict SEM. f) Scatterplots showing normalized pseudobulk RNA UMI count profiles of cells grouped by indicated CRISPR arrays (y-axis) and control cells that received non-targeting (NT) gRNAs (x-axis). Respective target genes (CD46, CD55, CD71) are highlighted in color. Genes on the MT chromosome are colored green. Other significantly differentially regulated genes (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test; adjusted p-value < 0.05) are highlighted in black. Genes highlighted in black showed a median expression change of 12.8% (s.d. 9.9%). CD71 + CD71 was not included in the experiment. g) Volcano plots showing differential gene expression results cells grouped by indicated CRISPR arrays and control NT cells. Cells grouping is the same as in (f). The x-axis indicates log-transformed fold changes. The y-axis depicts −log10-transformed adjusted p-values (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test). Significantly differentially regulated genes (adjusted p-value < 0.05) are highlighted in red.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Evaluation of Cas13d specific off-target effects in CaRPool-seq.

a) Sites, and relative expression levels of gRNA-dependent predicted off-target transcripts from gRNAs targeting CD46, CD55 and CD71. Red letters indicate mismatches and indels to cognate perfect match target site. E-values derived from Blastn. (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test * p.adj. < 0.05, ** p.adj. < 0.01, *** p.adj. < 0.001). b) Bulk RNA-seq result for Cas13d, Cas9-nuclease, and KRAB-dCas9-MeCP2 based targeting of CD55 using three independent CD55-targeting and NT (s)gRNAs, respectively. Volcano plots show differential gene expression results of CD55 targeting conditions relative to corresponding NT conditions grouped by indicated CRISPR effector protein. The x-axis indicates log-transformed fold changes. The y-axis depicts −log10-transformed adjusted p-values (DESeq2). Significant differentially regulated genes (adjusted p-value < 0.05, Wilcoxon’s rank sum test) are highlighted in red. The three approaches show a varying number of differentially expressed genes in addition to CD55 reduction (n = 1 Cas13d, n = 3 Cas9, n = 30 KRAB-dCas9-MeCP2). Cas13d gRNA and Cas9 sgRNA efficiency is shown in Extended Data Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 5a. c) Differential gene expression of mitochondrial genes. Differential gene expression was assessed between all 26 cell populations expressing gene-targeting gRNAs and cells expressing a single NT gRNA. Across all differential gene expression analyses (n = 26), none of the 13 mitochondrial genes encoded on the mitochondrial chromosome was expressed significantly different from control cells (adjusted p-value < 0.05; Wilcoxon’s rank sum test). The figure shows the average log2 fold change (FC) across all 13 mitochondrial genes per condition (n = 26) grouped by the number of target genes (left) and number of targeting gRNAs (right) indicating that observed changes are independent of target RNA and gRNA amounts. d) Fraction of cells classified into indicated cell cycle stages for each condition (n = 29). Dotted lines indicate the means of the three NT cell populations. Statistical testing for differences in cell cycle stage assignment for cell populations targeting e) varying numbers of target genes per cell, or using f) increasing numbers of gRNAs per cell did not show significant differences to NT control cell populations expressing zero targeting gRNAs (p-values derived from two-sided students t-test, not corrected for multiple testing. Bars in (e) and (f) show mean. Error bars depict SEM. N numbers indicated inside bars).

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Comparison of CaRPool-seq to alternative combinatorial perturbation approaches.

a) Density plots showing the CD46-APC, CD55-FITC, and CD71-PE flow cytometry signal upon Cas9-nuclease mediated knockout (KO) and CRISPRi-mediated (KRAB-dCas9, KRAB-dCas9-MeCP2) knockdown with three alternative sgRNAs from established genome-wide KO20 and CRISPRi21 libraries. Vertical lines mark the threshold (2nd percentile of combined NT conditions) for CD-protein negative cells, indicating the percent negative cells for one replicate experiment. Single guide RNAs with the highest percentage of negative cells (bold) were selected for direct capture Perturb-seq experiments (NA = sgRNA not assayed). b) Cloning strategy for triple sgRNA plasmid vectors. Dual sgRNA constructs were cloned as described before 6. The third sgRNA was cloned behind a bovine U6 promoter using an alternative sgRNA scaffold tested before 6. c) Cell surface protein expression (log2-normalized UMI counts) of CD46, CD55 and CD71 in cells assigned with indicated (s)gRNAs. CaRPool-CITE-seq (n = 4,979 cells) and Perturb-seq experiments using Cas9-nuclease (n = 2,270), KRAB-dCas9 (n = 2,104) or KRAB-dCas9-MeCP2 (n = 2,326). d) Contour plots of data shown in (c). e) Protein level ADT-based clustering of single-cell expression profiles of merged CaRPool-CITE-seq (n = 6,986 cells) and Perturb-seq experiments using Cas9-nuclease (n = 2,836), KRAB-dCas9 (n = 2,911) or KRAB-dCas9-MeCP2 (n = 3,038) effector proteins as in Fig. 3e. Cells are labelled by the assigned target gene combination based on detected bcgRNA or sgRNAs and split by Perturb-seq.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. A pooled Cas13 screen identifies regulators of AML differentiation.

a) Timeline for THP1 cell infections and pooled screen readouts for CD14 and CD11b fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS). We transduced a pooled lentivirus library with 4,800 gRNAs targeting 439 genes (10 gRNAs per gene) and 410 NT control gRNAs. Each gRNA was tested using two alternative Cas13d direct repeat (DR) sequences [wildtype (WT) or enhanced DR; see Methods]. Cells were infected at two different MOIs for each DR. Cells were collected at day 7 (timepoint 0; t0) and approximately day 14 (range between day 14 and day 16; t1) post Cas13d induction. On day 14, cells were sorted based on their cell surface protein expression into CD14 and CD11b high (top 15%) and low (bottom 15%) bins. At each time point, we collected and sorted cell populations with >1000x coverage. With alternative MOI infections and DR sequences used, we conducted four and three replicated phenotypic cell sorts for CD14 and CD11b. b) Pearson correlation of normalized and batch corrected gRNA counts for all samples. c) Pearson correlation of log2-transformed gRNA enrichments of the population of interest relative to the corresponding control population (CD11bhigh/low: gRNA counts in CD11bhigh bin divided by CD11blow bin; CD14high/low: gRNA counts in CD14high bin divided by CD14low bin; proliferation: gRNA counts at t1 divided by t0). d) Correlation of log2FC gene enrichments for CD14 upregulation (CD14high/low) to enrichments presented in Wang et al. Correlation analysis was repeated for every single ranked gRNA (see Methods), always considering only one ranked gRNA per target gene. This analysis indicated that, as expected, target gene enrichments for CD14 upregulation correlated best with CD14 target gene enrichments in Wang et al., and that correlations were similarly high for the top-ranked 4-5 gRNA. e) Similar analysis as presented in d showing result for target genes regulating CD11b enrichments. f) Volcano plot showing gene enrichments for target genes regulating CD14 upregulation (CD14high/low). Each gene is represented as the mean of the four top-ranked gRNAs across all replicate experiments (see Methods). Y-axis shows −log10 transformed adjusted p-value derived from Robust Ranked Aggregation (RRA). Target genes selected based on previous results (Wang et al.) are shown in red. The 28 genes used in the subsequent CaRPool-seq experiment are highlighted. As expected, CD14 was the most depleted gene. g) Similar analysis as presented in (f) showing results for target genes that lead to CD11b enrichment. CD11b-targeting gRNAs were not included in the gRNA library. h) Consistent gRNA enrichment/depletion of all 28 target genes. (NT = all non-targeting gRNAs, All = all gRNAs, Gene Name = Red ticks highlighting targeting specific gRNAs atop of the non-targeting gRNA distribution (n = 10 per target gene). Dotted lines indicate the 95 percent confidence interval for NT gRNA distribution). i) CD11b expression upon individual gRNA infections for 26 hit genes and three NT controls. Cas13d expressing THP1 cells were transduced with individual gRNA-delivering lentivirus targeting one out of 26 selected target genes (gRNA was selected from pooled screen). Cells were assayed repeatedly (three and six-to-seven days post Cas13d-induction with doxycycline) for CD11b levels. Y-axis shows the CD11b::PE-Cy7 MFI relative to the average of all three NT control samples for the respective time point. Bars show the mean of two independent replicates (two THP1 Cas13d cell thaws infected on separate days). The inset shows CD11b::PE-Cy7 levels in KDM1A and NT targeted cells three and six days after Cas13d induction.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Combinatorial targeting of AML differentiation regulators.

a) Titration of CaRPool-seq lentivirus four days after transduction. Viral constructs contain a Puromycin-2A-GFP expression cassette. Density plots show the percent GFP positive cells compared to the 99th percentile of WT control cells. The percent GFP-positive cells indicate the MOI. Low-MOI cells were used in the CaRPool-seq experiment, and high-MOI conditions were used for pooled screen readout (= 3 infections). b) Differential expression analysis for ADTs of cell surface proteins assayed in the CaRPool-seq experiment. Each point represents results for one gene pair summarizing the effect across both independent CRISPR array replicates per gene pair (n = 186, single and double perturbations). To account for differences in cell number per gene pair we calculated log2FC as the mean of 10 samples of a random cell using 30 cells (or all cells for gene pairs < 30 cells) per gene pair relative to the same number of NT control cells. All but two gene pairs show elevated levels of CD11b. Boxes indicate the median and interquartile ranges, with whiskers indicating 1.5 times the interquartile range. c) Density plots showing the CD11b::PE-Cy7 signal of THP1 cells transduced with NT gRNAs or the CaRPool-seq library 8 days post Cas13d-induction. We collected unsorted cells alongside cells sorted based on CD11b signal collecting the 15% of lowest and highest CD11b signal. We collected and sorted cell populations with >1000x coverage. d) Pearson correlation of normalized and batch corrected bcgRNA counts for all samples. e) Pearson correlation of log2-transformed bcgRNA enrichments of population of interest relative to the corresponding control population (CD11bhigh/low: bcgRNA counts in CD11bhigh bin divided by CD11blow bin; CD11bhigh/input: bcgRNA counts in CD11bhigh bin divided by unsorted input representation; CD11blow/input: bcgRNA counts in CD11blow bin divided by unsorted input representation). f) Comparison of log2FC CD11b ADT enrichments relative to NT cells in CaRPool-seq data comparing the two technical replicate gene pair arrays. Shown are all technical replicates where both arrays were represented by at least 25 cells (n = 122 gene pairs). g) Correlation of CD11bhigh/low log2FC enrichments in dual perturbation cells and the mean log2FC of both single perturbation cells corresponding to the dual perturbation (n = 158 gene pairs). Residuals indicate the distance to the average linear relationship. For each gene pair, we used the mean of both replicate CRISPR arrays.

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Transcriptome analysis of combinatorial targeting of AML differentiation regulators.