Summary

Background

Multidimensional poverty is associated with dementia, but no evidence is available for countries in conflict.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in two provinces of Afghanistan between February 15th 2022 and April 20th 2022 among adults age 50 and older. Multidimensional poverty included six dimensions of well-being and 16 indicators of deprivation. The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale measured dementia. Poverty between adults with and without dementia was examined, adjusting for sex. Associations between dementia and poverty were investigated using multivariate regression model.

Findings

Of the 478 adults included, 89 (52.7%) had mild, and 25 (14.8%) had moderate to severe dementia. More women than men had mild (52.7% vs 33.3%) and moderate-to-severe dementia (14.8% vs 5.8%). Approximately 33.9% adults with mild and 51.2% adults with moderate-to-severe dementia were found to be deprived in four or more dimensions compared to 21.8% without dementia. The difference in four dimensions of multidimensional poverty between adults with mild and moderate-to-severe dementia and adults without dementia was respectively 59.5% and 152.88%. Education, employment, health, and living conditions were the main contributors to the adjusted poverty head count ratio. Multidimensional poverty in four or five dimensions was strongly associated with dementia among older adults particularly over 70 years old (odds ratio [OR], 17.38; 95% CI, 2.22–135.63), with greater odds for older women overall (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.76–4.11).

Interpretation

Our findings suggest that early improvement in social determinants of health through targeted structural policies may lower dementia risk later in life. Specifically, better access to free, quality education, healthcare, and basic living standard together with employment opportunities could reduce risk of dementia.

Funding

The present study was funded by a grant from the Alzheimer Association (AARG-NTF-21-851241).

Keyword: Afghanistan, Dementia, Multidimensional poverty, Rural areas, Social and environmental determinants of health

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched Pub Med, Google Scholar and SCOPUS for scientific publications about poverty and dementia in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) since 2000 without language restriction up until December 1st 2022. We used the following combination of search terms: “dementia”, “Alzheimer” “Alzheimer disease∗“, “cognitive disorders” and “poor” or “poverty” OR “social determinants of health”. We showed that multidimensional poverty has a high impact on adults with dementia and that at an advanced age, it is also strongly associated with dementia. Dimensions of deprivation reflect early life inequities that accumulate during the life course to result in poor health at a late stage. No study on dementia in a crisis context exist. One study examined risk prediction models applied to LMICs contexts.1 One study found that people with Alzheimer's disease have a lower level and smaller range of capabilities.2 Another study in a middle-income country showed that multidimensional poverty was linked to dementia.3 However, no study has shown this in a conflict context.

Added value of this study

Our study builds on a small corpus of literature that investigates social and environmental determinants of dementia. Our findings show that the risk of dementia in older adults is strongly associated with multidimensional poverty, particularly for women.

Implications of all the available evidence

Individuals who report multiple deprivations during the life course are at increased risk of developing dementia. Public policies targeting addressing major social determinants of health, primarily free quality education and healthcare and employment, can reduce risk factors for dementia at a later stage in life.

Introduction

The aging population is growing, particularly in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) where improvements in healthcare and infrastructure supporting basic needs like nutrition have increased life expectancy.4 LMICs now face a crisis among their aging population resulting from a higher risk of dementia and cognitive impairments.5 The World Health Organization estimates that adults affected with dementia will reach 152 million by 2050 with at least 60% of them living in LMICs.6

A greater prevalence of dementia will result in higher costs shared mostly by LMICs representing a compounding economic burden.1,2 In the absence of formal geriatric services, families shoulder this burden in LMICs.3 Older adults are often providers of childcare and complete essential household chores and tasks. The increase in dementia prevalence threatens the fragile balance of multi-generational familial socioeconomic system.7,8 As older adults transition to being the recipients of medical care, both family breadwinners and children will experience a reduction in their capacity to work outside of the home and to attend school.9

Multiple conditions have been linked to social and environmental determinants of health (SEDOH).10, 11, 12 The 2020 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care identified twelve potentially modifiable risk factors that have been documented to date, including smoking, air pollution, hypertension, depression, traumatic brain injury, absence of education, and social exclusion.13 The World Health Organization recently acknowledged that inequalities in SEDOH during the life course such as access to care, treatments, and healthy diets may increase the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia prevention.14 Yet limited research examines how SEDOH increases dementia risk evaluated using measures of multidimensional poverty which are associated with chronic health conditions.15 This methodology responds to critiques that income or consumption do not characterize poverty and well-being.16 Instead, it investigates well-being and factors that influence well-being beyond a utility perspective.17

Afghanistan has been in a chronic state of crisis and is no exception to the dementia burden affecting other LMICs. After more than four decades of war, Afghanistan is facing a political crisis with a radical change of regime, an environmental crisis with higher occurrences of floods and drought, an eroded agricultural sector, and a developing economic crisis. In 2020, half of the population was living under the national poverty line. A 2021 United Nations Development Program (UNDP) study projected that 97% of Afghans will be poor in 2022 following a contraction of the GDP estimated at 13.2%.18 Older adults are particularly at risk of multidimensional poverty as evidenced in Afghanistan,19 the United States,20 Hong Kong,21,22 Iran,23 and Taiwan.24 Estimates from a mental health study (n = 4336) established dementia prevalence at 5.8% for Afghans over age 65.25 In this study, we examined major contributors to multidimensional poverty of older Afghans and its association with dementia. We hypothesized that SEDOH measured with a multidimensional poverty methodology is positively associated with dementia in older adults.

Methods

Study design and setting

We randomly selected 1038 older adults among a sample of 2434 households from an education study carried in 43 villages of Badakhshan and Ghazni provinces, where 25% of primary school going children (grades 3–5) were living and interviewed them between February 15th 2022 and April 20th 2022. Informed consent was obtained from each participant and informant. Instruments were forward and backward translated into Dari and Pashto (dominant languages in Afghanistan) with different translators to ensure accuracy and were tested and validated. The study received approval by the Human Research Protection Office of Washington University in St Louis and by the Ministry of Public Health in Afghanistan. We adhere to the STROBE guidelines for this study.

Dementia outcome

The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS)26 was used to assess dementia. Since gold standard imaging or cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers are impossible to obtain rapid screening appeared to be the only way to assess dementia risk. Demographics, health conditions, education, employment, various aspect of livelihood, depression, stress, stigma, and exposure to traumatic events data were obtained. Two field supervisors and eight enumerators were trained over one week on survey concepts and goals, questionnaires, and interview techniques.

Multidimensional poverty measures I

To measure multidimensional poverty, we included six dimensions that are central to well-being, namely education, health, living standards, economic activity, social participation, and psychological well-being (See Table 1). Each dimension is composed of one or several indicators defining human development (see note in Supplementary file). Multidimensional poverty can be measured for a number of dimensions within a spectrum ranging from one dimension—the “intersection” approach considering poor as anyone falling below a threshold on one dimension—or the “union” approach which considers poor as anyone falling beyond a threshold on all defined dimensions (See note in Supplementary material).

Table 1.

Dimensions of poverty, indicators and cutoff of deprivation.

| a. Dimensions | b. Indicators | c. Deprivation cutoff (Deprived if …) |

|---|---|---|

| Education | ||

| 1. Adult educational attainment | What is the older adult highest Education Level? | Did not go to school |

| Health status | ||

| 2. Activities limitation and functioning problem | Any Difficulties you may have doing certain activities because of a health problem? | Participant answered “a lot of difficulty/cannot do at all” in ANY of 6 Questions of Washington Group for disability statistics: Seeing, Hearing, walking, concentrating, dressing, communicating |

| 3. Food security | Are you food insecure? | Food Consumption Score (FCS) is unacceptable—households with a score less than 35 |

| Household-level material well-being/Living standards | ||

| 4. Crowded space | How many people per room? | More than three people per room |

| 5. Water source | What is the main source of drinking water for your current household? | The household does not have “Piped drinking water in dwelling” |

| 6. Energy source cooking | What is the main source of energy that this household uses for cooking? | Deprived if the household does NOT use gas or electricity instead uses wood, coal. |

| 7. Energy source heating | What is the main source of energy that this household uses for heating? | Deprived if the household does NOT use gas or electricity instead uses wood, coal, other source such as plastic |

| 8. Energy source lighting | What is the main source of energy that this household uses for lighting? | Deprived if the household does NOT use gas or electricity instead uses paraffin, wood, coal, candles, animal dung. |

| 9. Sanitation | What type of toilet does your current household use? | The household does not “Own flush toilet inside the house” OR “Own flush toilet outside the house” |

| 10. What assets does the household own? | Does any member of your household own any of the following? Radio, tape recorder/Television/Mobile phone/Pressure cooker-big pots/Refrigerator/Generator solar panels/Bicycle-Motorbike/Car-Tractor/House or apartment | Less than 6 assets. But if family own a tractor or a car they are automatically set as non-deprived |

| 11. What animals does your household own? | Does any member of your household own any of the following animals? Camels/Cows & buffalos/Horse/Donkeys/seeps-goats/Poultry | Owning no animals |

| Economic activity | ||

| 12. Employment | Which one of the following best describes what you are currently doing? Are you currently looking for job or what is the reason for not looking for a job? | Participant responded “yes to currently looking for a job” OR “Participant was not looking for a job because he/she has the following reason: I am too old, I am disabled” |

| Social participation | ||

| 13. Stigma (Experienced unfair treatment) | Have you been unfairly treated? 0–1 is minimal discrimination; 1–1.5 is low discrimination; 1.5–2 is moderate discrimination; and 2 and above is considered high discrimination | Stigma score is > 1.5 (had at least moderate discrimination) on the Unfair treatment scale. |

| Psychological well-being | ||

| 14. Depression | Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale. CES-D-10 scale is a self-report measure composed of 10 items assessing symptoms of depression in the last week. The total score—between 0 and 30—is calculated by adding the 10 items. Intensity of depression rises with the score with 10 being mild depression. | Depression score is ≥ 15 (moderate depression) |

| 15. Distress | 22 items Afghan symptoms checklist (ASC) scale. The scale ranges from 0 to 88. Scores of 0 is normal range; scores below 1 and 22 suggest low distress. Score between 23 and 44 suggests moderate distress; score between 49 and 66 suggests high distress; score beyond 67 up to 88 suggests very high distress | ASC score is above 49. |

| 16. Exposure to traumatic events | List of 20 traumatic events that sometimes happen to people with response “yes” or “no”. The higher the number of events exposed to, the higher the risk of trauma. | Exposure to five or more traumatic events. |

(a) Indicates the dimension of deprivation. (b) Describes how each indicator of deprivation is constructed (questions or measures with items asked). (c) Specifies what is the cutoff identifying those deprived from those who are not for each indicator of deprivation.

Education is essential in crisis contexts to support future employment and income, as well as promoting health and hygiene,27 social justice, and peace.28 Participants were considered deprived if they were never enrolled in primary school, a threshold that reflects the enduring lack of schooling in protracted crisis contexts and the historically low enrolment in Afghanistan, particularly for girls.29,30

Health comprised two indicators. Firstly, disability is known to be associated with poverty and social exclusion in Afghanistan.19,31 Difficulty or inability to complete activities in 14 domains of the short version of the Disability Screening Questionnaire was considered as the cut-off for deprivation of health status.32 Secondly, food insecurity measured by the food consumption score affects half of the population with devastating effects including caloric deficiency, no dietary diversity, and delayed child development.33

Unemployment is an important characteristic of multidimensional poverty34 including in Afghanistan.19 Being unemployed and looking for a job or being discouraged to look for a job because of low wage, high age, a disease or a disability was the cut-off.

Household living standards was composed of seven indicators (crowded space, unsafe water, cooking, heating, lighting sources, unimproved sanitation, few assets or no animals). Cut-off were based on UNICEF or World Health Organization standards for hygiene and health.

Stigma were measured using the Discrimination and Stigma Scale with moderate stigma as the cut-off.35 Finally, measures of depression, distress, and exposure to traumatic events defined psychological well-being,36 a critical component of multidimensional poverty, particularly in the case of disability37 and cognitive disorders linked to aging.38 Depression measured using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R-10)39 has been linked to multidimensional poverty among older adults.38 A threshold of 15 or more was retained as the cut-off since two-thirds were mildly depressed (score >10). Distress was assessed using the 22-item Afghan symptoms checklist (ASCL) with a score of 49 considered as the cut-off.40 The traumatic event checklist shows that exposure to five traumatic events or more was associated with childhood psychiatric disorders in Afghanistan.41

Statistical analysis

We measured prevalence of poverty comparing older rural Afghans with and without dementia using independently gauged dimensions referring to shortfalls on each of the sixteen indicators.42 The multidimensional poverty measure considers a cut-off within each dimension and across dimensions (see Supplementary material). Study participants were considered deprived in a given dimension if they fell below this cut-off on indicators of a dimension. They were considered multidimensionally poor if they were deprived on at least d dimensions, d varying between one and sixteen.

We assessed normality of distribution for the intensity of poverty (A) using Q–Q plots. We then used Student t-tests to separately assess and one at a time the difference in (A) between adults with RUDAS cut-offs of no dementia, mild dementia or moderate-to-severe dementia stratifying by sex and age group, and found that all mean differences were significant.43 We also conducted a Dunn's test to perform multiple pairwise comparisons together with a Bonferroni adjustment and results remained unchanged (data not shown). We examined overlap of indicators of deprivation using Spearman rank correlation analysis.

Logistic regression models examined the association between multidimensional poverty and a binary outcome of either ‘no-to-mild’ and ‘moderate-to-severe’ dementia. Multidimensional poverty exposure was defined by d ≥ 4. This threshold corresponds to the highest gap in intensity of poverty between older adults with and without dementia, and a prevalence of poverty of 29.2% among all older adults and 59.5% among older adults with dementia, to be compared to 2020 estimates of 49.4% poor while the whole population is at risk of poverty today.18 Other adjusted covariates included, sex (male/female), age (continuous), marital status (living alone/with partner), and household size (continuous). A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using Stata (v.16.1).

Ethics committee approval

The present study received ethical approval from the Human Research Protection Office of Washington University in St Louis and the Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan.

Role of the funding source

The funders were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor did they have a role in the writing of the manuscript and decision to submit it for publication. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and accepted the responsibility to submit it for publication.

Results

Participant characteristics

Out of 1038, we interviewed 478 older adults and excluded 560 (54%) due to absence at the time of interview (death or migration, see Fig. 1). We identified 235 adults without dementia, 192 adults with mild dementia and 43 with moderate-to-severe dementia using the RUDAS.

Fig. 1.

Participants Recruitment through three stages sampling selection. At the 1st stage of sampling, villages are selected. At the 2nd stage, households within each village were randomly selected. At the 3rd stage of sampling, older adults 50 years old or more were randomly selected among all adults 50 years old or more identified in the selected households.

Compared to women (32.5%), more men were classified as not having dementia (60.8%) (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The proportion of adults without dementia decreased significantly between age 50–59 years old (60.9%) and 70 years old and above (12.3%) (p < 0.001). A higher proportion of older adults with moderate-to-severe dementia were living alone without partner (23.3% compared to 4.1% among those without dementia, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Sample demographic characteristics by dementia status.

| No dementia n = 235 | Mild dementia n = 192 | Moderate to severe dementia n = 43 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | ||||

| Male | 188 (77.4) | 103 (53.7) | 18 (41.9) | <0.001 |

| Female | 55 (22.6) | 89 (46.3) | 25 (58.1) | |

| Age (n, %) | ||||

| 50–59 | 148 (60.9) | 96 (50.0) | 8 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| 60–69 | 65 (26.8) | 52 (27.1) | 11 (25.6) | |

| ≥70 | 30 (12.3) | 44 (22.9) | 24 (55.8) | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 58.4 (81) | 61.6 (9.6) | 70.6 (11.3) | |

| Marital status (n, %) | ||||

| Living with partner | 233 (95.9) | 164 (85.4) | 33 (76.7) | <0.001 |

| Living alone | 10 (4.1) | 28 (14.6) | 10 (23.3) | |

| Household size (mean, SD) | 8.9 (3.0) | 9.3 (3.2) | 9.7 (3.5) |

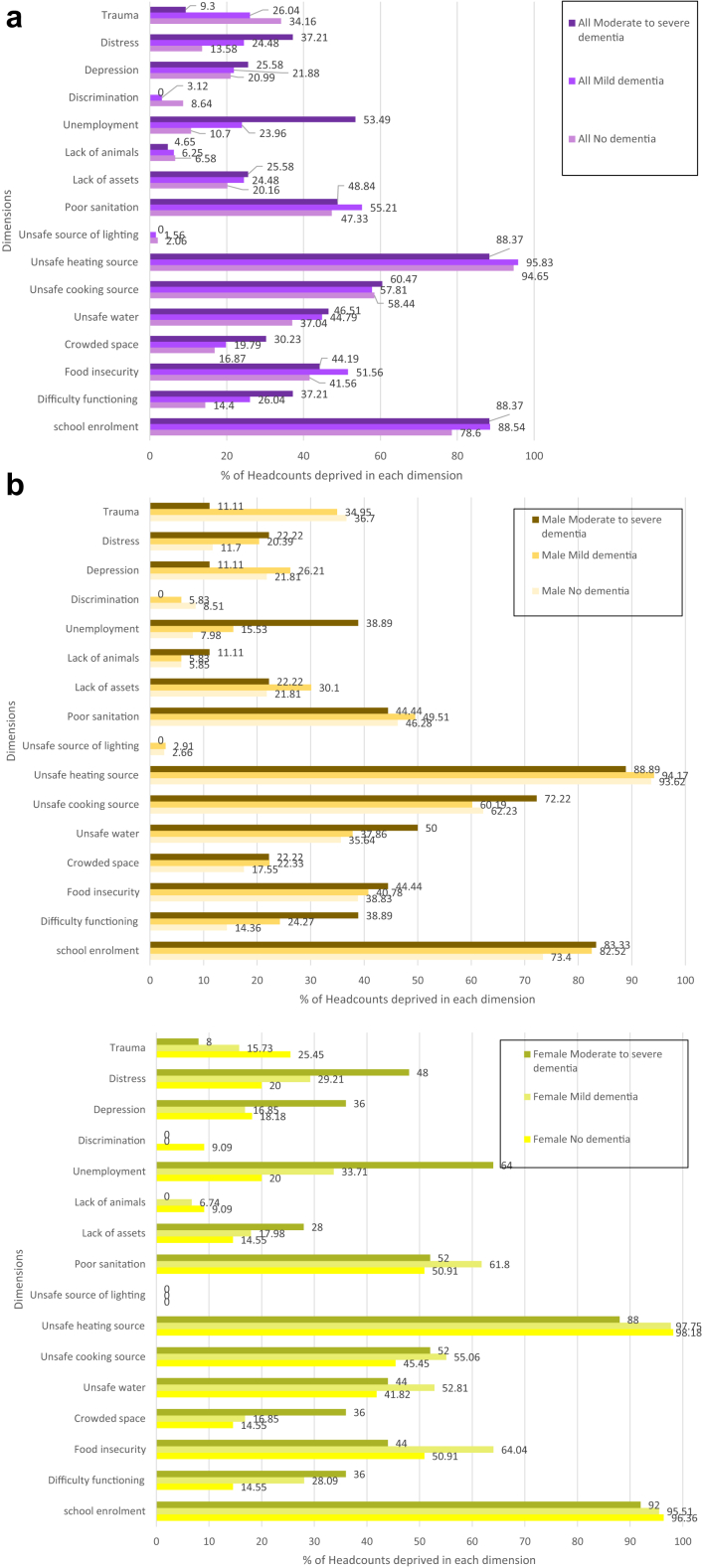

A higher proportion of adults with moderate-to-severe dementia were significantly more deprived of education (88.4% vs 78.6%, p < 0.014), health status (37.2% vs 14.4%, p < 0.001), employment (53.5% vs 10.7%, p < 0.001), and were more often distressed (37.2% vs 13.6%, p < 0.001) compared to adults without dementia. Differences were not significant for food insecurity (2.6%), crowded space (13.4%), unclean water (9.5%), cooking source (2%), sanitation (1.5%), lack of assets (5.4%), depression (4.6%), and opposite for heating (−6.3%) and lighting (−2.1%) sources, lack of animals (−1.9%), stigma (−8.6%), and trauma (−24.9%) (Fig. 2 and Table S1 in supplement). Men with moderate/severe dementia were more often deprived of health (38.9% vs 14.4%, p < 0.01) and employment (38.9% vs 8.0%, p < 0.001) compared to those without dementia. Women with moderate/severe dementia were also more often deprived of employment (64% vs 20%, p < 0.001) but not significantly of health. Women with moderate/severe dementia were significantly less likely to be stigmatized (−9.1%, p < 0.008) compared to those without dementia. The difference exists but was marginally significant for men. Differences in deprivation on other indicators for both sexes were marginally significant. A higher number of adults with dementia aged 50–59 years old and over 70 years old were deprived of employment (p < 0.003 and p < 0.002 respectively). Poor health status was more prevalent after 60 years old (p < 0.022), and depression after 70 years old (p < 0.012), for adults with dementia.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of poverty for each of the 16 indicators of deprivation. (a) Shows the prevalence of poverty by indicator and by dementia status alone (b) Shows the prevalence of poverty by indicator, by dementia status and by sex and (c) Shows the prevalence of poverty by indicator, by dementia status and by age group (50–59 years old; 60–69 years old and over 70 years old).

We estimated Spearman rank correlation coefficients between each pair of indicators (Table 3). We found no evidence of strong correlation between indicators, confirming limited association between them. We observed some significant correlations for living standard indicators. We kept all eight indicators and assigned each an eighth of the dimension weight in the equal nested weights structure to avoid over-representation44 (see Supplementary material). Similarly, we found some correlation between depression/distress and depression/trauma part of the same dimension. While stigma was also associated with depression, distress, and trauma, it specifically assesses a link between prejudice resulting from negative stereotypes and discrimination against a specific group, and was therefore kept in a separate dimension.45 Limited correlations between indicators substantiate a multidimensional approach to poverty rather than a single welfare indicator such as income to represent complexity that innervates poverty.

Table 3.

Spearman rank correlations between indicators of deprivation.

| School enrolment | Difficulty functioning | Food insecurity | Crowded space | Unsafe water | Unsafe cooking source | Unsafe heating source | Unsafe source of lighting | Poor sanitation | Lack of assets | Lack of animals | Unemployment | Stigma | Depression | Distress | Trauma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School enrolment | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Difficulty functioning | 0.0647 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Food insecurity | 0.0022 | 0.2337∗ | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Crowded space | 0.0315 | −0.0707 | −0.1827 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Unsafe water | 0.0961∗ | 0.1937∗ | 0.2664 | −0.1481∗ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Unsafe cooking source | 0.1155∗ | −0.0307 | −0.1348∗ | 0.0571 | −0.0898∗ | 1 | ||||||||||

| Unsafe heating source | 0.0671 | 0.0338 | 0.128∗ | −0.1169∗ | 0.1249∗ | 0.2091∗ | 1 | |||||||||

| Unsafe source of lighting | −0.0298 | 0.0523 | −0.0545 | 0.0604 | −0.0756 | 0.044 | −0.1125∗ | 1 | ||||||||

| Poor sanitation | −0.0338 | 0.1831∗ | 0.295∗ | −0.1547∗ | 0.3469∗ | −0.0446 | 0.1691∗ | −0.0343 | 1 | |||||||

| Lack of assets | 0.1309∗ | −0.0321 | −0.1614∗ | 0.1325∗ | −0.0599 | 0.3314∗ | 0.0403 | 0.2038∗ | 0.0384 | 1 | ||||||

| Lack of animals | −0.0474 | −0.0283 | 0.0737 | 0.0268 | −0.0228 | −0.1664∗ | −0.052 | −0.0338 | −0.0378 | −0.0355 | 1 | |||||

| Unemployment | 0.0805 | 0.3073 | 0.0997∗ | −0.0038 | 0.0858 | −0.0792 | 0.0039 | −0.0241 | 0.0829 | −0.0411 | 0.0008 | 1 | ||||

| Stigma | −0.0619 | −0.0378 | 0.1206∗ | −0.1195∗ | 0.0171 | −0.0875 | −0.0212 | −0.0319 | 0.0785 | −0.0879 | 0.1235∗ | −0.0537 | 1 | |||

| Depression | 0.0299 | −0.0866 | 0.0545 | 0.077 | −0.151 | 0.1676∗ | 0.037 | 0.0893 | −0.0776 | 0.2277∗ | 0.0099 | 0.0042 | 0.1126∗ | 1 | ||

| Distress | −0.0019 | 0.1115∗ | 0.2098∗ | −0.0196 | 0.0598 | −0.1169∗ | 0.0742 | 0.016 | 0.0982 | −0.0562 | 0.0641 | 0.1298∗ | 0.194∗ | 0.2292∗ | 1 | |

| Trauma | −0.0792 | 0.0119 | −0.0628 | −0.0043 | −0.0675 | 0.0473 | −0.052 | 0.0616 | −0.0311 | 0.0703 | −0.0114 | −0.0722 | 0.1856∗ | 0.1367∗ | 0.0287 | 1 |

∗p < 0.05.

Multidimensional poverty

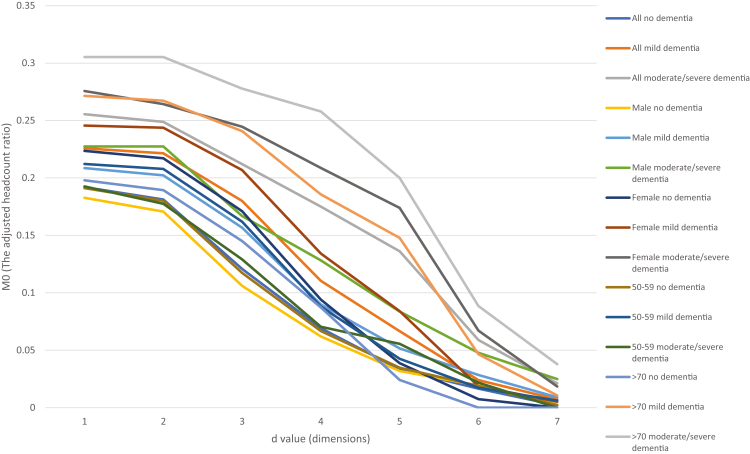

The level of poverty measured by (H) varied according to dementia and the cut-off d considered. The union approach of deprivation determines that an individual was multidimensionally poor if deprived on one dimension (d = 1).46 We found respectively 95.5%, 96.9% and 97.7% of adults with no, mild, and moderate to severe dementia to be poor (Fig. 3 and Supplement Table S2). An intersectional approach considers complete multidimensionally poverty as being deprived in all dimensions (d = 16) where 1.3% were poor in d = 7 indicators. A higher proportion of men and women with moderate-to-severe dementia were poorer irrespective of the d between one and seven compared to respectively men and women without dementia (except for d = 2 for women). On d = 7, no woman without dementia was poor, but 4% of women with moderate-to-severe were poor. The proportion of poorer women with moderate-to-severe dementia was higher for d = 1 and 3 < d < 6 than for men with moderate-to-severe dementia (Supplement Table S3). For d = 4, the proportion of poor adults without dementia was 21.8% while it was 33.9% among older adults with mild dementia and 51.2% among those with moderate-to-severe dementia (Supplement Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Adjusted poverty headcount ratio for the equal indicator weighting structure stratified by dementia status alone (no, mild, moderate to severe cognitive impairment and dementia), by dementia status and sex (male, female) and by dementia status and age group (50–59 years old; 60–69 years old and over 70 years old).

Whatever the cut-off d value between one and seven, older adults with moderate-to-severe dementia had a significantly (p < 0.05) higher adjusted headcount ratio (M0) compared to adults with both mild or no dementia (Fig. 3). The difference varied between 33.1% for d = 1 and 983.6% for d = 7 (Supplement Table S2).

(M0) was higher for a cut-off (d) between one and seven for both women and men with moderate-to-severe dementia compared respectively to women and men without dementia (Fig. 3, Supplement Table S3). The difference in depth of poverty as measured by (M0) is significant for both men and women whatever (d). For d = 4, the difference is respectively 107.1% (p < 0.046) and 121.8% (p < 0.003) between men and women with moderate-to-severe dementia compared to those without dementia. Multidimensional poverty was significantly higher among adults older than 70 years old with moderate-to-severe dementia whatever the cut-off (d) with a difference of 195.6% for d = 4 (p < 0.001). This difference was not significant for adults aged 50–69 years old (p < 0.896, Supplement Table S4).

Whatever the cut-off (d) for dementia status and sex, education was the highest contributor. Interestingly, unemployment was the second contributor to poverty for both men and women with moderate-to-severe dementia, and even more so for women for all (d), as well as for older adults above 70 with moderate to severe dementia for 1 < d < 5 compared to older adults above 70 without dementia and to older adults 50–69 with moderate to severe dementia (Table 4). Health and living conditions were third contributors with similar level of contribution to poverty, with health becoming a more important contributor than living conditions as we consider a higher value of (d). Health was a higher contributor than living conditions to poverty for older adults above 70 with moderate-to-severe dementia.

Table 4.

Percentage contribution of each indicator of deprivation to multidimensional poverty by dementia status alone (no, mild, moderate to severe cognitive impairment and dementia), by dementia status and sex (male, female) and by dementia status and age group (50–59 years old; 60–69 years old and over 70 years old).

| d | Indicator of deprivation | All | All |

Male |

Female |

Age 50-69 |

Over 70 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dementia | Mild dementia | Moderate/severe dementia | No dementia | Mild dementia | Moderate/severe dementia | No dementia | Mild dementia | Moderate/severe dementia | No dementia | Mild dementia | Moderate/severe dementia | No dementia | Mild dementia | Moderate/severe dementia | |||

| 1 | Education | 0.412 | 0.426 | 0.409 | 0.360 | 0.418 | 0.412 | 0.382 | 0.449 | 0.405 | 0.348 | 0.430 | 0.435 | 0.427 | 0.404 | 0.340 | 0.327 |

| Health | 0.165 | 0.152 | 0.179 | 0.166 | 0.152 | 0.162 | 0.191 | 0.152 | 0.195 | 0.151 | 0.150 | 0.173 | 0.142 | 0.167 | 0.196 | 0.178 | |

| Living conditions | 0.184 | 0.195 | 0.178 | 0.158 | 0.207 | 0.188 | 0.181 | 0.164 | 0.169 | 0.144 | 0.200 | 0.192 | 0.174 | 0.167 | 0.144 | 0.149 | |

| Employment status | 0.098 | 0.058 | 0.111 | 0.218 | 0.045 | 0.078 | 0.178 | 0.093 | 0.143 | 0.242 | 0.046 | 0.083 | 0.142 | 0.140 | 0.183 | 0.256 | |

| Stigma | 0.028 | 0.047 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.046 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.017 | 0.000 | |

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.113 | 0.121 | 0.109 | 0.098 | 0.129 | 0.131 | 0.068 | 0.099 | 0.087 | 0.116 | 0.129 | 0.105 | 0.114 | 0.070 | 0.119 | 0.090 | |

| 2 | Education | 0.416 | 0.433 | 0.412 | 0.360 | 0.432 | 0.415 | 0.382 | 0.436 | 0.408 | 0.347 | 0.435 | 0.437 | 0.432 | 0.422 | 0.346 | 0.327 |

| Health | 0.163 | 0.149 | 0.176 | 0.170 | 0.146 | 0.158 | 0.191 | 0.157 | 0.194 | 0.158 | 0.148 | 0.169 | 0.154 | 0.156 | 0.195 | 0.178 | |

| Living conditions | 0.179 | 0.189 | 0.176 | 0.155 | 0.197 | 0.186 | 0.181 | 0.166 | 0.167 | 0.138 | 0.194 | 0.190 | 0.166 | 0.154 | 0.141 | 0.149 | |

| Employment status | 0.102 | 0.062 | 0.113 | 0.224 | 0.049 | 0.080 | 0.178 | 0.096 | 0.144 | 0.252 | 0.049 | 0.085 | 0.154 | 0.147 | 0.186 | 0.256 | |

| Stigma | 0.029 | 0.050 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 0.018 | 0.000 | |

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.111 | 0.118 | 0.109 | 0.091 | 0.124 | 0.132 | 0.068 | 0.102 | 0.086 | 0.105 | 0.126 | 0.106 | 0.093 | 0.067 | 0.115 | 0.090 | |

| 3 | Education | 0.359 | 0.365 | 0.365 | 0.320 | 0.355 | 0.361 | 0.312 | 0.387 | 0.368 | 0.324 | 0.367 | 0.383 | 0.382 | 0.359 | 0.324 | 0.297 |

| Health | 0.194 | 0.186 | 0.206 | 0.171 | 0.185 | 0.187 | 0.191 | 0.188 | 0.223 | 0.162 | 0.187 | 0.204 | 0.127 | 0.179 | 0.211 | 0.187 | |

| Living conditions | 0.158 | 0.160 | 0.161 | 0.147 | 0.167 | 0.168 | 0.173 | 0.144 | 0.154 | 0.134 | 0.164 | 0.171 | 0.165 | 0.135 | 0.136 | 0.141 | |

| Employment status | 0.135 | 0.092 | 0.139 | 0.263 | 0.078 | 0.103 | 0.243 | 0.122 | 0.170 | 0.273 | 0.075 | 0.109 | 0.212 | 0.191 | 0.206 | 0.281 | |

| Stigma | 0.036 | 0.067 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.073 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 0.020 | 0.000 | |

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.117 | 0.129 | 0.112 | 0.099 | 0.141 | 0.142 | 0.081 | 0.103 | 0.085 | 0.108 | 0.140 | 0.116 | 0.113 | 0.064 | 0.102 | 0.094 | |

| 4 | Education | 0.311 | 0.310 | 0.314 | 0.304 | 0.295 | 0.304 | 0.316 | 0.342 | 0.323 | 0.300 | 0.308 | 0.328 | 0.312 | 0.318 | 0.293 | 0.303 |

| Health | 0.207 | 0.189 | 0.226 | 0.194 | 0.201 | 0.219 | 0.226 | 0.161 | 0.231 | 0.180 | 0.183 | 0.224 | 0.195 | 0.219 | 0.230 | 0.194 | |

| Living conditions | 0.138 | 0.134 | 0.140 | 0.142 | 0.140 | 0.139 | 0.158 | 0.121 | 0.141 | 0.135 | 0.139 | 0.150 | 0.156 | 0.104 | 0.124 | 0.139 | |

| Employment status | 0.172 | 0.118 | 0.182 | 0.263 | 0.107 | 0.124 | 0.226 | 0.141 | 0.227 | 0.280 | 0.103 | 0.152 | 0.234 | 0.199 | 0.230 | 0.269 | |

| Stigma | 0.048 | 0.099 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.098 | 0.056 | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.103 | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.080 | 0.026 | 0.000 | |

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.124 | 0.151 | 0.113 | 0.097 | 0.158 | 0.158 | 0.075 | 0.134 | 0.079 | 0.106 | 0.164 | 0.123 | 0.104 | 0.080 | 0.098 | 0.095 | |

| 5 | Education | 0.280 | 0.270 | 0.285 | 0.285 | 0.261 | 0.275 | 0.277 | 0.294 | 0.293 | 0.287 | 0.268 | 0.282 | 0.296 | 0.287 | 0.288 | 0.282 |

| Health | 0.193 | 0.167 | 0.216 | 0.178 | 0.165 | 0.206 | 0.207 | 0.171 | 0.223 | 0.168 | 0.155 | 0.207 | 0.148 | 0.287 | 0.224 | 0.184 | |

| Living conditions | 0.127 | 0.119 | 0.127 | 0.140 | 0.122 | 0.127 | 0.147 | 0.110 | 0.127 | 0.138 | 0.122 | 0.130 | 0.160 | 0.090 | 0.124 | 0.136 | |

| Employment status | 0.210 | 0.128 | 0.228 | 0.285 | 0.139 | 0.137 | 0.277 | 0.098 | 0.293 | 0.287 | 0.113 | 0.215 | 0.296 | 0.287 | 0.240 | 0.282 | |

| Stigma | 0.062 | 0.141 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.122 | 0.098 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.155 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 0.000 | |

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.127 | 0.175 | 0.103 | 0.113 | 0.191 | 0.157 | 0.092 | 0.131 | 0.065 | 0.120 | 0.188 | 0.116 | 0.099 | 0.048 | 0.091 | 0.116 | |

| 6 | Education | 0.252 | 0.259 | 0.249 | 0.247 | 0.259 | 0.249 | 0.242 | 0.258 | 0.251 | 0.249 | 0.259 | 0.245 | 0.253 | NA | 0.255 | 0.245 |

| Health | 0.205 | 0.168 | 0.227 | 0.226 | 0.172 | 0.231 | 0.242 | 0.129 | 0.219 | 0.218 | 0.168 | 0.224 | 0.253 | NA | 0.229 | 0.221 | |

| Living conditions | 0.123 | 0.116 | 0.116 | 0.144 | 0.119 | 0.107 | 0.152 | 0.097 | 0.133 | 0.140 | 0.116 | 0.122 | 0.158 | NA | 0.108 | 0.141 | |

| Employment status | 0.159 | 0.103 | 0.159 | 0.247 | 0.115 | 0.107 | 0.242 | 0.000 | 0.251 | 0.249 | 0.103 | 0.163 | 0.253 | NA | 0.153 | 0.245 | |

| Stigma | 0.103 | 0.181 | 0.091 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.142 | 0.000 | 0.258 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.181 | 0.082 | 0.000 | NA | 0.102 | 0.000 | |

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.159 | 0.172 | 0.159 | 0.137 | 0.163 | 0.166 | 0.121 | 0.258 | 0.146 | 0.145 | 0.172 | 0.163 | 0.084 | NA | 0.153 | 0.147 | |

| 7 | Education | 0.226 | 0.220 | 0.226 | 0.230 | 0.220 | 0.225 | 0.233 | NA | 0.229 | 0.226 | 0.220 | 0.229 | NA | NA | 0.222 | 0.230 |

| Health | 0.208 | 0.110 | 0.226 | 0.230 | 0.110 | 0.225 | 0.233 | NA | 0.229 | 0.226 | 0.110 | 0.229 | NA | NA | 0.222 | 0.230 | |

| Living conditions | 0.113 | 0.083 | 0.094 | 0.158 | 0.083 | 0.099 | 0.146 | NA | 0.086 | 0.170 | 0.083 | 0.086 | NA | NA | 0.111 | 0.158 | |

| Employment status | 0.189 | 0.220 | 0.151 | 0.230 | 0.220 | 0.113 | 0.233 | NA | 0.229 | 0.226 | 0.220 | 0.114 | NA | NA | 0.222 | 0.230 | |

| Stigma | 0.075 | 0.220 | 0.075 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 0.113 | 0.000 | NA | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 0.114 | NA | NA | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.189 | 0.147 | 0.226 | 0.153 | 0.147 | 0.225 | 0.155 | NA | 0.229 | 0.151 | 0.147 | 0.229 | NA | NA | 0.222 | 0.153 | |

Multivariate analysis

The risk of dementia was 4.4 times higher (95% CI 2.05–9.35) for multidimensionally poor older adults, for d = 4. It was 2.3 times higher (95% CI, 0.94–5.36) but not significant (p < 0.067) for poor older adults adjusting for sex, marital status, age, and household size It was higher for adults ≥70 years (17.4, 95% CI 2.25–135.63, see Table 5). The results remain the same for d = 5. Being female increased the relative risk of dementia by 3.2 (95% CI 2.17–4.78, p < 0.001) in the unadjusted model and by 2.7 (95% CI 1.4.16, p < 0.001) in the adjusted model but not significantly if we only consider adults >70 years old. Similarly, living without a partner increased the risk for older adults in the unadjusted (4.49, p < 0.001) and adjusted models (2.47, p < 0.021), but not significantly if we only consider adults >70 years old. Household size had marginal influence in all models. We tested the interaction between poverty ∗sex and poverty ∗marital status, but results were not significant.

Table 5.

Logistic regression results of multidimensional poverty on dementia adjusted for gender, marital status, age and household size for adults over 50 years old and over 69 years old.

| Unadjusted analysis |

Adjusted analysis 50 and over |

Adjusted analysis 69 and over |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p-value | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Multidimensionally poor (Ref: not poor) | 4.42 | 2.05–9.532 | <0.001 | 15.61 | 1.42–171.6 | 0.025 | 17.38 | 2.22–135.6 | 0.006 |

| Female (Ref: male) | 3.22 | 2.17–4.778 | <0.001 | 5.50 | 1.73–17.40 | 0.004 | 2.52 | 0.78–8.141 | 0.122 |

| Living alone (Ref: living with partner) | 4.49 | 2.18–9.251 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 0.27–4.18 | 0.913 | 2.51 | 0.60–10.4 | 0.207 |

| Household size (continuous) | 1.05 | 0.98–1.10 | 0121 | 1.08 | 0.99–1.17 | 0.079 | 0.99 | 0.94–1.04 | 0.816 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.054 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 0.91–1.26 | 0.387 | 1.10 | 0.91–1.32 | 0.295 |

| Constant | 0.00 | 0.00–0.05 | 0.006 | 0.18 | 0.00–5.90 | 0.332 | |||

OR, odd ratios; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference category.

The model was fully adjusted with sex, marital status, age, and household size.

Sensitivity analysis

Multidimensional poverty calculation was repeated using the equal-indicator weight (EIW) structure between the six dimensions and results held when adjusting for sex (data not shown). Multidimensional poverty was found to be significantly higher for older adults with moderate-to-severe dementia compared to older adults without dementia for any cut-off (d). Both women and men with dementia were poorer than women and men without dementia for all (d). Contributions of dimensions to (M0) consistently showed the pre-eminence of education, and employment for older adults with and without dementia and for both sexes.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide evidence that older adults with dementia face higher risk of multidimensional poverty in a protracted crisis setting. Exposure to multidimensional poverty, considering six domains of SEDOH– namely education, health, living standards, economic activity, stigma, and psychological well-being were associated with dementia. Older women, and particularly those with dementia were poorer and on a higher number of dimensions compared to men, including men with dementia. A similar relationship for older women being poorer than older men was established in Iran.23 Using the same methods in this study, we demonstrated that older women in South Africa were more at risk for dementia.38 Being a widow, separated or divorced was a risk factor for dementia. The literature has shown that being a woman without a life partner in Afghanistan is associated with higher risk of common mental disorders (distress, anxiety, mild to moderate depression).47 We found that higher poverty was associated with dementia at an older age. Additionally, deprivation of education first, but also health and employment contributed substantially to multidimensional poverty, eventually linking social and environmental determinants of health to dementia. Universal access to free quality education and healthcare during the life course might contribute to both prevention and lower dementia severity in later life, particularly in LMICs including crisis contexts where difficulties are heightened.48 Access to the labour market during the adult life might also contribute to lower the risk and consequences of dementia later in life, a finding that remains to be further investigated. Unfortunately, while men are allowed to participate in public life and are expected to work outside home, women remain confined within domestic walls of their family compound in application to the Islamic rule of purdah (seclusion) or the segregation of genders.49, 50, 51 Overall, promoting socioeconomic fairness through redistributive public policies might mitigate negative consequences of existing health inequities.52 In conflict settings, the dearth of resources and the absence of services to serve a growing aging population, and higher rate of dementia reinforce the need for provision of essential services such as healthcare, early education livelihoods, and employment stimulus to simply improve the population overall standard of living. Stigma did not contribute much to poverty indicating that respect for elders remains what has traditionally been a strong value in a country that promote familial obligations above anything else. Older adults did not experience discriminatory behaviours from family members and friends or ill-treatment in the public sphere such as going to the mosque, seeking healthcare, in interactions with the police or with other people in the community. The contributions from indicators of psychological well-being were not extremely high, and very different according to the dementia status. Overall, older adults endured depression, anxiety, and traumatic events but traditional family support systems, despite a multi-decade process of disruption due to war, economic, and political upheaval, kept ensuring family cohesiveness and individual resilience.

This study has some limitations. First, it was not possible to establish causality between poverty and dementia since poverty can be a risk factor or a consequence of dementia. Second, the RUDAS captured multiple cognitive limitations without being able to establish a formal diagnosis or corroboration with conventional biomarkers (e.g., imaging cerebrospinal fluid). Third, sample size was limited, reducing the statistical power to further investigate the association between multidimensional poverty and dementia at an older age (beyond 75 years old). Fourth, 53.9% of participants in the initial sample were missing interviews, which might have introduced bias in our results because we cannot assume they were missing completely at random and therefore generalizing our findings to the two provinces of Badakhshan and Ghazni must be considered with caution. Fifth, we were not able to collect information about comorbidities in absence of healthcare availability, cost-prohibitive routine medical visits to the closest healthcare facility, or due to limited capacity of available healthcare structure to provide care. Finally, with the exception of education, indicators of early life risk factors were not available or measured due to recall bias.

This study is unique by its insight into Afghanistan, a country in political turmoil for over four decades and facing the consequences of climate variations, a new government isolated from the international community, and the COVID pandemic. Our evidence suggests that daily stressors compounded over years resulting from SEDOH identified through multiple dimensions of poverty increases dementia risk in middle adulthood. Public health professionals should directly consider addressing dementia in crisis settings rather than conceptualizing it as a “back burner” issue. While SEDOH influences numerous chronic conditions, in crisis contexts such as Afghanistan, dementia risk may be mitigated by accessible and quality education and free universal healthcare. Public health professionals and physicians irrespective of specialties can raise awareness of dementia risks in these complex settings to reduce dementia's impact while at the same time improving overall health status of the population.48

Contributors

JFT conceived designed and supervised the study, carried the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. JFT, YZ, and SP supervised the data collection. YZ and SP cleaned the data and carried the first analysis. GB, SP, and YZ accessed the data and verified the analysis. JFT, GB, and YZ interpreted the data. RA and DK provided overall technical support. All authors read, contributed, and approved the final manuscript.

Data sharing statement

All data is available upon request to the first author.

Declaration of interests

Dr. Babulal receives research support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (R01AG068183, R01AG067428, R01AG074302, R01AG074302), BrightFocus Foundation (A2021142S), and the Alzheimer's Association (SG-22-968620).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Alzheimer's Association (AARG-NTF-21-851241). The authors are thankful to the enumeration team who worked in challenging conditions to collect the information for this study in rural provinces of Badakhshan and Ghazni in Afghanistan. They thank all the respondents for their participation in the present study. Finally, they are thankful to Terje Magnussønn Watterdal, Country Director of the Norwegian Afghanistan Committee (NAC), and all the colleagues in the NAC for their ongoing support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101906.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Thrush A., Hyder A. The neglected burden of caregiving in low-and middle-income countries. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(3):262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nandi A., Counts N., Chen S., et al. Global and regional projections of the economic burden of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias from 2019 to 2050: a value of statistical life approach. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;51:101580. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schatz E., Seeley J. Gender, ageing and carework in East and Southern Africa: a review. Glob Public Health. 2015;10(10):1185–1200. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1035664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Y.-T., Fratiglioni L., Matthews F.E., et al. Dementia in Western Europe: epidemiological evidence and implications for policy making. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(1):116–124. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parra M.A., Butler S., McGeown W.J., Nicholls L.A.B., Robertson D.J. Globalising strategies to meet global challenges: the case of ageing and dementia. J Glob Health. 2019;9(2) doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson C. Alzheimer’s Disease International; London: 2018. World Alzheimer report 2018. The state of the art of dementia research: new frontiers. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casale M. 'I am living a peaceful life with my grandchildren. Nothing else. 'Stories of adversity and 'resilience' of older women caring for children in the context of HIV/AIDS and other stressors. Ageing Soc. 2011;31(8):1265. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skovdal M., Ogutu V.O., Aoro C., Campbell C. Young carers as social actors: coping strategies of children caring for ailing or ageing guardians in Western Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernqvist S. Negotiating parenthood: experiences of economic hardship among parents with cognitive difficulties. J Intellect Disabil. 2015;19(3):215–229. doi: 10.1177/1744629515571379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehury B., Mohanty S.K. Multidimensional poverty, household environment and short-term morbidity in India. Genus. 2017;73(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s41118-017-0019-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinilla-Roncancio M., Mactaggart I., Kuper H., et al. Multidimensional poverty and disability: a case control study in India, Cameroon, and Guatemala. SSM Popul Health. 2020;11 doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorant V., Deliège D., Eaton W., Robert A., Philippot P., Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):98–112. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livingston G., Huntley J., Sommerlad A., et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2022. A blueprint for dementia research. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callander E.J., Schofield D.J., Shrestha R.N. Chronic health conditions and poverty: a cross-sectional study using a multidimensional poverty measure. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkinson A.B. Multidimensional deprivation: contrasting social welfare and counting approaches. J Econ Inequal. 2003;1(1):51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen A.K. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. Development as freedom. [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations Development Programme . United Nations Development Programme; Kabul: 2021. Economic instability and uncertainty in Afghanistan after August 15. A rapid appraisal. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trani J.-F., Kuhlberg J., Cannings T., Chakkal D. Multidimensional poverty in Afghanistan: who are the poorest of the poor? Oxf Dev Stud. 2016;44(2):220–245. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhongde S. Measuring multidimensional poverty and deprivation. Springer; 2017. Assessing multidimensional deprivation among the elderly in the USA; pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou K.-L., Lee S.-Y. Superimpose material deprivation study on poverty old age people in Hong Kong study. Soc Indic Res. 2018;139(3):1015–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan L.-S., Chou K.-L. Poverty in old age: evidence from Hong Kong. Ageing Soc. 2018;38(1):37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohaqeqi Kamal S.H., Basakha M., Alkire S. Multidimensional poverty index: a multilevel analysis of deprivation among Iranian older adults. Ageing Soc. 2022:1–20. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X2200023X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen K.-M., Leu C.-H. Multidimensional perspective of the poverty and dynamics of middle-aged and older adults in Taiwan. Int Soc Work. 2022;65(1):142–159. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovess Masfety V., Sabawoon A., Mazzega-Grossin A. Conseil Santé & Governance Institute of Afghanistan; Kabul: 2018. National mental health survey and assessment of mental health services in Afghanistan. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storey J.E., Rowland J.T., Conforti D.A., Dickson H.G. The Rowland universal dementia assessment scale (RUDAS): a multicultural cognitive assessment scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16(1):13–31. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feinstein L., Sabates R., Anderson T.M., Sorhaindo A., Hammond C. Measuring the effects of education on health and civic engagement: proceedings of the Copenhagen symposium. OECD Paris; France: 2006. What are the effects of education on health; pp. 171–354. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith Ellison C. The role of education in peacebuilding: an analysis of five change theories in Sierra Leone. Compare. 2014;44(2):186–207. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones A.M. Afghanistan on the educational road to access and equity. Asia Pacific J Educ. 2008;28(3):277–290. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kissane C. The way forward for girls' education in Afghanistan. J Int Womens Stud. 2012;13(4):10–28. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trani J.F., Ballard E., Pena J. Stigma of persons with disabilities in Afghanistan: examining the pathways from stereotyping to mental distress. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trani J.F., Babulal G.M., Bakhshi P. Development and validation of the 34-item disability screening questionnaire (DSQ-34) for use in low and middle income countries epidemiological and development surveys. PLoS One. 2015;10(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United Nations . 2022. Afghanistan: nearly 20 million going hungry.https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/05/1117812 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basu K., Nolen P. In: Rational choice and social welfare theory and applications. Pattanaik P.K., Tadenuma K., Xu Y., Yoshihara N., editors. Springer; Berlin: 2008. Unemployment and vulnerability: a class of distribution sensitive measures, its axiomatic properties, and applications; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brohan E., Clement S., Rose D., Sartorius N., Slade M., Thornicroft G. Development and psychometric evaluation of the discrimination and stigma scale (DISC) Psychiatry Res. 2013;208(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund C., Breen A., Flisher A.J., et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(3):517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trani J.-F., Bakhshi P., Myer Tlapek S., Lopez D., Gall F. Disability and poverty in Morocco and Tunisia: a multidimensional approach. J Human Dev Capabil. 2015;16(4):518–548. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trani J.-F., Moodley J., Maw M.T.T., Babulal G.M. Association of multidimensional poverty with dementia in adults aged 50 years or older in South Africa. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e224160. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radloff L.S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen A., Ventevogel P., Sancilio A., Eggerman M., Panter-Brick C. Comparing the validity of the self reporting questionnaire and the Afghan symptom checklist: dysphoria, aggression, and gender in transcultural assessment of mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panter-Brick C., Eggerman M., Gonzalez V., Safdar S. Violence, suffering, and mental health in Afghanistan: a school-based survey. Lancet. 2009;374(9692):807–816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alkire S., Foster J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J Public Econ. 2011;95(7–8):476. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruxton G.D., Beauchamp G. Time for some a priori thinking about post hoc testing. Behav Ecol. 2008;19(3):690–693. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alkire S., Maria F.J.S.S.S., Paola E.R.J.M.B., et al. Oxford University Press; USA: 2015. Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Link B.G., Phelan J.C. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bourguignon F., Chakravarty S. The measurement of multidimensional poverty. J Econ Inequal. 2003;1:25–49. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trani J.F., Bakhshi P. Vulnerability and mental health in Afghanistan: looking beyond war exposure. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50(1):108–139. doi: 10.1177/1363461512475025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization . 2017. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupree N. In: Development effort in Afghanistan: is there a will and a way? The case of disability and vulnerability. Trani J.F., editor. L'Harmattan; Paris: 2011. The historical and cultural context of disability in Afghanistan; p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cerveau T. In: Development efforts in Afghanistan: is there a will and a way? The case of disability and vulnerability. Trani J.F., editor. L'Harmattan; Paris: 2011. Deconstructing myths; facing reality. Understanding social representations of disability in Afghanistan; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bakhshi P., Trani J.F. In: Development efforts in Afghanistan: is there a will and a way? The case of disability and vulnerability. Trani J.F., editor. L'Harmattan; Paris: 2011. A gender analysis of disability, vulnerability and empowerment in Afghanistan. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Commission on Social Determinants of Health . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health final report. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.