Abstract

RNAs are involved in the crucial processes of disease progression and have emerged as powerful therapeutic targets and diagnostic biomarkers. However, efficient delivery of therapeutic RNA to the targeted location and precise detection of RNA markers remains challenging. Recently, more and more attention has been paid to applying nucleic acid nanoassemblies in diagnosing and treating. Due to the flexibility and deformability of nucleic acids, the nanoassemblies could be fabricated with different shapes and structures. With hybridization, nucleic acid nanoassemblies, including DNA and RNA nanostructures, can be applied to enhance RNA therapeutics and diagnosis. This review briefly introduces the construction and properties of different nucleic acid nanoassemblies and their applications for RNA therapy and diagnosis and makes further prospects for their development.

Key words: Nucleic acid nanoassembly, DNA nanotechnology, RNA nanotechnology, RNA therapy, RNA detection, DNA origami, RNA interference, DNA tetrahedron

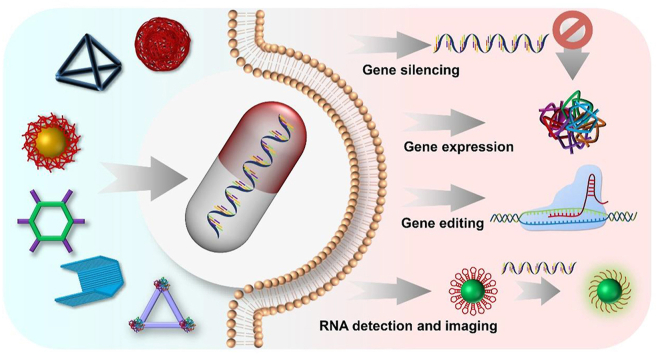

Graphical abstract

Nucleic acid nanoassemblies with different shapes and structures are fabricated for enhanced RNA-based gene silencing, gene expression, gene editing, gene detection, and imaging strategies.

1. Introduction

Due to numerous roles in disease genesis and progression, RNAs have emerged as promising therapeutic and diagnostic candidates1,2. RNA therapy is one of the best therapeutic strategies as it targets disease-causing genes in a sequence-specific manner, enabling more precise and personalized treatments for diverse life-threatening diseases. By introducing a specific nucleic acid sequence to the desired tissue, gene expression can be downregulated, augmented, or corrected. Small interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are representative molecules for gene inhibition, whereas messenger RNA (mRNA) and CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/Cas (CRISPR-associated protein) systems are usually employed to increase or correct target gene expression3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Currently, a few RNA-based therapeutics are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and/or the European Medicines Agency (EMA), aiming at the treatment of various diseases by gene modifications with siRNA or ASOs (Table 1)12.

Table 1.

RNA therapeutics approved by the FDA and/or EMA.

| Therapeutic | Type | Route of administration | Disease | Target gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fomivirsen (vitravene) | 21-mer ASO | Intravitreal | Cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompromised patients | Cytomegalovirus IE-2 mRNA |

| Mipomersen (kynamro) | 20-mer ASO | Subcutaneous | Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia | Apolipoprotein B mRNA |

| Nusinersen (spinraza, ASO-10-27) | 18-mer ASO | Intrathecal | Spinal muscular atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing (exon 7 inclusion) |

| Eteplirsen (exondys 51) | 30-mer ASO | Intravenous | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD pre-mRNA splicing (exon 51 skipping) |

| Inotersen (tegsedi, AKCEA-TTR-LRx) | 20-mer ASO | Subcutaneous | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | TTR mRNA |

| Patisiran (onpattro) | 21 nt ds-siRNA | Intravenous | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | TTR mRNA |

| Golodirsen (vyondys 53, SRP-4053) | 25-mer ASO | Intravenous | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD pre-mRNA splicing (exon 53 skipping) |

| Givosiran (givlaari) | 21 nt ds-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Acute hepatic porphyria | δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase 1 mRNA |

| Viltolarsen (viltepso, NS-065, NCNP-01) | 21-mer ASO | Intravenous | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD pre-mRNA splicing (exon 53 skipping) |

| Volanesorsen (waylivra) | 20-mer ASO | Subcutaneous | Familial chylomicronaemia syndrome | APOC3 mRNA |

| Inclisiran (leqvio, ALN-PCSsc) | 22 nt ds-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, elevated Chol, homozygous/heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia | PCSK9 mRNA |

| Lumasiran (oxlumo, ALN-GO1) | 21 nt ds-siRNA | Subcutaneous | Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 | HAO1 mRNA |

APOC3, apolipoprotein CIII; DMD, dystrophin; HAO1, hydroxyacid oxidase 1; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; SMN2, survival of motor neuron 2; TTR, transthyretin.

In addition to RNA therapy, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including circular RNA (circRNA), miRNA, and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), have been proposed as promising diagnostic biomarkers13. Among those ncRNAs, miRNAs are able to incorporate into RNA-inducing silencing complex (RISC) for subsequent mRNA downregulation or degradation, therefore influencing the output of many protein-coding genes. Several miRNAs have been used as a monitoring indicator of numerous diseases, such as cancer and coronary artery disease14, 15, 16, 17.

Even though RNA molecules have promising prospects in disease therapy and diagnosis, their clinical applications have been hampered by some obstacles18,19. Intracellular and extracellular barriers, including RNases degradation, clearance by the immune system, nonspecific interactions with proteins or nontarget cells, and renal clearance, may hinder RNA molecules from reaching the target tissues20, 21, 22, 23. Several obstacles remain before RNAs can be used in clinics for disease diagnostics, such as low abundance, sequence similarities, reproducibility, time, cost, and complexity24.

Researchers have made significant efforts to maximize the therapeutic and diagnostic potency of RNAs. Currently, nanomaterials made of lipids, polymers, peptides, and exosomes, have been investigated for RNA delivery4,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32. Considering the cytotoxicity and immune response of those materials33, nucleic acid nanoassemblies with better biocompatibility, structural programmability, and ready access to modifications are attracting much attention as promising carriers for nucleic acid drugs34. Unlike polymer- or lipid-based nanomaterials, nucleic acid-made nanomaterials can be degraded by the inherent nuclease, thereby avoiding toxicity of the delivery vehicles35, 36, 37, 38. Nucleic acid nanoassemblies are usually fabricated by bottom-up construction, and the designer precisely controls each property and step along the way. Theoretically, the researchers assemble any desired structure by nucleic acid sequences39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46. The well-ordered structure and high stability also improved the recognition efficiency and reduced the nonspecific adsorption of RNAs on the biosensing platform47. Recently, many reviews on the progress of biomedical applications of nucleic acid nanoassemblies were published in a more detailed summary48, 49, 50, 51. This review will focus on the representative and enlightening works in RNA-based therapy and diagnostic strategies with DNA and RNA nanoassemblies in recent years (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Nucleic acid nanoassembly-enhanced RNA theranostics.

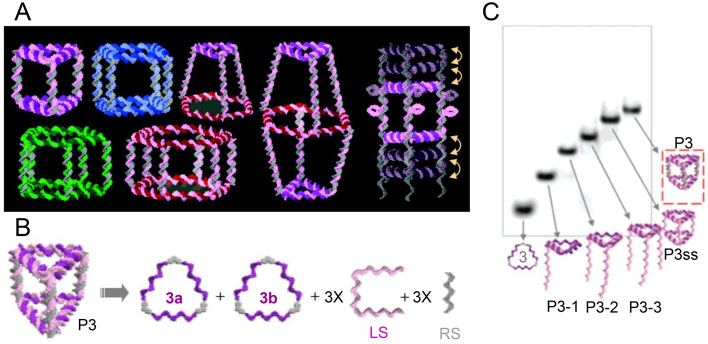

2. Emergence of nucleic acid nanoassemblies

Nucleic acid nanoassemblies, fabricated with DNA and RNA nanotechnology, have long been motivated by the aim of developing efficient drug delivery systems, tools for molecular biology, and nanodevices for disease diagnosis. Looking back into history, the concept of nucleic acid nanotechnology was proposed in the early 1980s, when Seeman pioneered an advanced DNA nanotechnology in materials science based on the principle of programmable self-assembly of DNA52, 53, 54, 55, 56. He proposed that DNA could be used as materials to build branched junctions. The research group constructed a closed polyhedral object from DNA by adding sticky ends to branched DNA molecules. Since then, short single-stranded DNAs have fabricated various DNA tiles, such as double-crossover, triple-crossover, and three-point star structures57.

In 1996, the DNA-mediated assembly of gold nanoparticles was achieved by functionalizing a gold nanoparticle with a single DNA strand58. With the development of DNA nanotechnology, more complicated DNA structures, DNA “walker”, have been designed, offering promising applications in biosensing and early cancer diagnosis59. Soon after, publications by Woo and Rothemund60,61 transformed the landscape of DNA nanotechnology. They revealed that DNA origami technology could be a powerful tool for DNA nanostructure assembly. With multiple short single-stranded DNAs called staples, a long DNA scaffold folded into nanostructures. DNA origami is a promising technology for the bottom-up construction of well-designed DNA structures ranging from nanometers to sub-micrometers. Without a long DNA scaffold, scientists presented a simple and robust approach for assembling DNA nanostructures by DNA “bricks”. The technique involves the computer design of arbitrary structures and their assembly using short synthetic DNA strands that form interconnected staggered duplexes62. More recently, other sophisticated DNA structures in two dimensions (2D) and three dimensions (3D), such as DNA–protein hybrid nanoscale shapes and “meta-DNA” structures, have been developed63,64.

RNA nanotechnology has attracted the attention of bioengineers due to its self-assembly properties into controllable nanostructures65, 66, 67. The versatile structure and function, the favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics profiles, and the potential as a therapeutic modality potentiate RNA nanoassemblies to be promising candidates for drug delivery. The structure variety of RNA nanostructures could be achieved by canonical Waston‒Crick, noncanonical base pairing, base stacking, and networks of tertiary contacts68. Many pioneering groups proposed the emergence of RNA nanotechnology. Early discoveries about RNA nanotechnology began with studies on bacteriophages.

As is well known, bacteriophage phi29 employs a unique pRNA to package its genomic DNA into the procapsid. Guo et al.69 found that the pRNA upper and lower loops are involved in RNA/RNA interactions. Mutation in only one loop resulted in inactive pRNAs. Mixing two, three, and six inactive mutant pRNAs restored DNA packaging activity in bacteriophage phi29, forming of pRNA dimers, trimmers, and hexamers. Then in the early 2000s, Jaeger, Westhof, and Leontis70 focused on studying nanoscaled RNA objects by tectoRNAs and artificial modular RNA units. With the development of RNA nanotechnology, RNA nanoassemblies can be constructed using hand–hand interactions69,71, 72, 73, foot-to-foot interactions71, 72, 73, stable natural RNA motifs70,74, 75, 76, 77, tectonics67,72,76,78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, and computational design88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94. The popularity of DNA origami has inspired researchers to study RNA origami. Geary et al.95 presented a method for designing single-stranded RNA structures (RNA origami) that fold either by heat-annealing or co-transcriptional folding. The arrays of antiparallel RNA helices can be accurately controlled by RNA tertiary motifs and a unique type of crossover pattern. As depicted in Fig. 2, these pioneering studies provide a solid foundation for further developments of nucleic acid nanoassemblies. In the next part, we will focus on several representative methods for constructing DNA and RNA nanoassemblies.

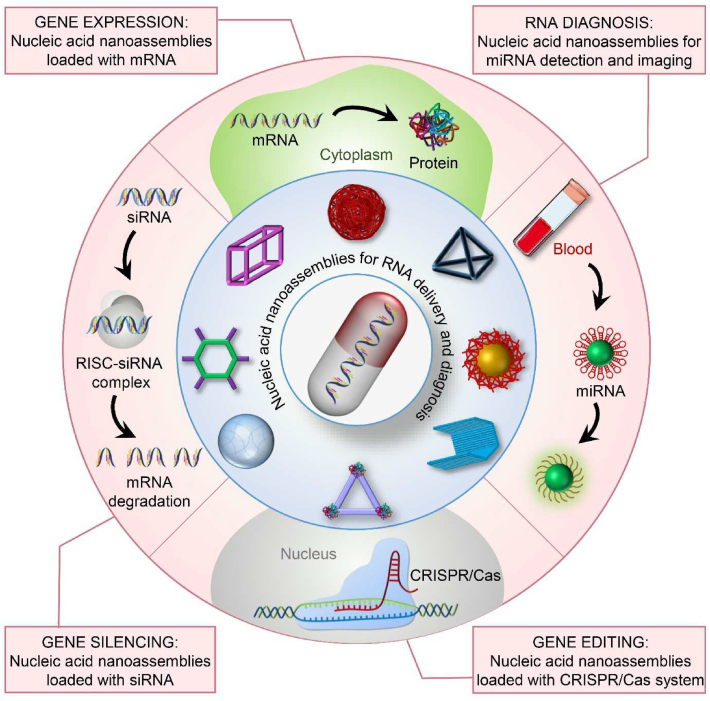

Figure 2.

Discoveries and major development of nucleic acid nanoassemblies.

3. Structural nucleic acid nanoassemblies

3.1. DNA nanoassemblies

3.1.1. DNA origami-derived nanoassemblies

DNA nanoassemblies were developed as DNA junctions and lattices in the early stage. The commonly used Y-shaped DNA has been constructed as a component of several DNA structures, such as DNA dendrimer, DNA barcode, and DNA hydrogel96, 97, 98, 99. The DNA origami technology61, which refers to a long single-stranded DNA scaffold (usually bacteriophage M13), paired with hundreds of complementary short-stranded DNA (usually 20–60 bp), and folded into a certain shape and different dimensions of nanoassemblies through programming, such as square, rectangle, star, disk, triangle, smile face, and wireframe41,61. Some researchers folded a map of China with this technology, which was also the first asymmetric nanopattern constructed using DNA origami100. Since DNA origami has many cross-structures of single-stranded DNA, its elastic modulus is approximately several times than that of a single DNA, which significantly increases the stability and toughness of internal structure, laying a solid foundation for its application in various fields101.

The structure of early DNA origami synthesis was relatively simple, but after the ongoing efforts of scientists, DNA origami has developed rapidly in just a dozen years. Many complex structures with 2D, 3D, and even curved surfaces have been assembled102, 103, 104, 105, 106. Yan, Liu, Han, and colleagues106 presented an approach to construct DNA nanostructures with intricate curved surfaces in 3D space by the DNA origami folding technique. However, manufacturing and manipulating an increasingly long scaffold strand to build even larger DNA origami structures remains challenging. Ong et al.105 proposed an alternative strategy involving the assembly of DNA bricks without the need for a scaffold. Each brick consisted of four short binding domains arranged so that the bricks interlocked. They also assembled a cuboid that can be used for 3D sculpting, enabling the creation of shapes like a teddy bear.

3.1.2. DNA polyhedrons

Researchers have adopted a bottom-up self-assembly method to synthesize a variety of 3D DNA nanostructures of various shapes and sizes. The 3D DNA nanostructures, such as cube54, and tetrahedron108, octahedron107 are all comprised of DNA strands with unique sequences. Chen and Seeman54 were the first to fabricate self-assembled cube nanostructures using DNA as raw material. However, its preparation process is cumbersome and requires multiple reactions, such as DNA chain circularization, enzyme ligation, and purification. Turberfield's group108,109 also adopted this face-to-center design using four single strands of DNA and obtained a series of DNA tetrahedral structures of different sizes. All of its preparation relied on simple complementary hybridization between single strands of DNA. Shih et al.107 folded a single DNA strand with a length of 1669 bases into an octahedral structure of DNA through complementary pairing with five auxiliary strands. The octahedral 3D frame structure could be observed by cryo-electron microscopy, demonstrating that the DNA strands fold successfully.

Later, Sleiman and colleagues110 constructed triangular, cubic, pentameric, hexameric prisms, heteroprism, and biprism assemblies in quantitative yields (Fig. 3A–C). Synthesizing large numbers of unique DNA strands to construct large structures poses a huge challenge in structure design111. He et al.44 demonstrated a simple solution to this problem through the one-pot self-assembly process. Sticky-ended, three-point-star motifs were firstly assembled by individual single strands of DNA. The three-point-star motif was composed of a long repetitive central strand, three identical medium strands, and three identical short peripheral strands. Then the tiles are further assembled into polyhedrons through a sticky-end association between the tiles. Using symmetrical three-pointed star tiles with sticky ends as the basic structural unit, they constructed various DNA polyhedral structures, such as tetrahedrons, dodecahedrons, and buckyballs.

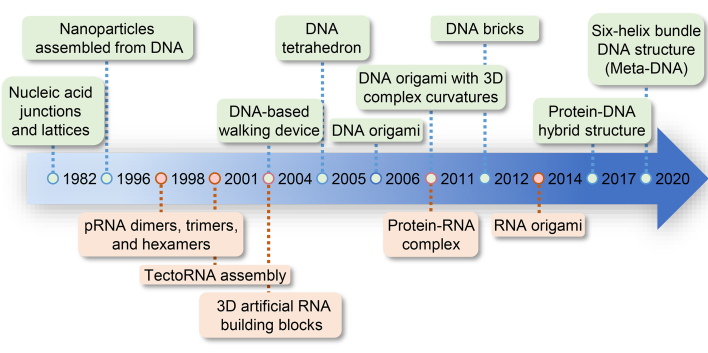

Figure 3.

3D DNA polyhedrons. (A) Structurally switchable 3D discrete DNA assemblies. (B) Scheme of general assembly concept used in constructing discrete DNA prism (P3). (C) PAGE analysis of all possible intermediates for P3. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 110. Copyright © 2007, American Chemical Society.

Among those sophisticated DNA structures, tetrahedral DNA nanostructures (TDNs) are one of the robust and straightforward 3D structural models112. It is characterized by excellent biocompatibility and programmability, abundant functional modification sites, strong mechanical rigidity, and high stability113. TDNs have been demonstrated to exhibit extraordinary cell membrane affinity, enhanced endocytosis, and tissue penetration. The natural ability of TDNs to scavenge reactive oxygen species may be beneficial for treating degenerative inflammatory diseases114. TDNs are composed of four single strands of DNA with equal lengths mixed and annealed in equal quantities. The 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-ends of every single strand meet at the vertex of tetrahedron or form a port on the side, where the port can be joined using DNA ligase or functionalized with other ligands115,116. The functionalization of TDNs refers to the structural modification of functional peptides, proteins, fluorescent dyes, and nucleic acid molecules117, 118, 119, 120. Ma et al.121 employed a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeted DNA aptamer-modified DNA tetrahedron (HApt-tFNA) as a drug delivery system for microtubule inhibitor maytansine. The conjugation with aptamer reduced the untargeted toxicity and severe side effects of cytotoxic drugs. The functional groups can be modified at different locations on TDNs. For instance, Xia et al.122 effectively increased the uptake rate of DNA tetrahedron in glioblastoma cells by adding tumor-penetrating peptide at the apex of tetrahedral nanostructure. Studies have also suspended the functionalized molecules or groups from the side arms of tetrahedral structures. Some researchers123 designed a tetrahedron DNA sensor based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer, which sensitively monitored telomerase activity in cells and was further applied to detect telomerase inhibitors.

3.1.3. Rolling circle amplification-mediated DNA nanoassemblies

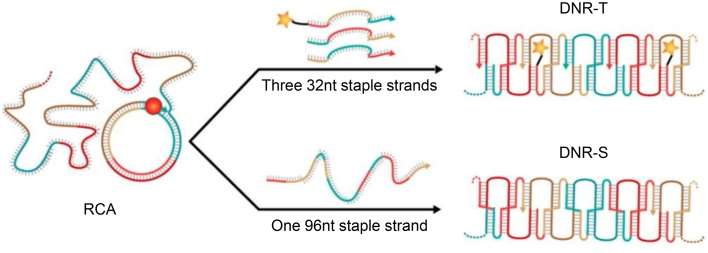

The rolling circle amplification (RCA) process continuously extends complementary single-stranded DNA using single-stranded circular DNA as a template under the catalysis of Phi29 DNA polymerase124. Different nanostructures can be built using RCA products of different lengths, such as nanoribbon125 and nanoclews126,127. In this strategy, a very small circular oligonucleotide acts as a template for a DNA polymerase, producing long repeating product sequences. Unlike other DNA synthesis methods, the RCA process produces multiple copies without the requirement for either a cooling or heating procedure. Therefore, the most significant advantage of RCA technology is that the reaction can be carried out under isothermal conditions, which is impossible with other nucleic acid amplification technologies. Inspired by natural one-dimensional structures with a high aspect ratio, such as actin filaments and microtubules, Chen et al.125 constructed DNA nanoribbon structures using RCA product as the scaffold. The nanoribbon was folded by only three short staple strands or one concatenated long-staple strand. The distinct rigid structure of nanoribbon with a high aspect ratio and nanoscale dimension allowed the penetration of nanoribbon through cell membranes and facilitated endosome escape. The siRNA-loaded nanoribbon downregulated the target mRNA expression and protein production by approximately 40% and 45%, respectively (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

DNA nanoribbon fabricated by RCA process for gene silencing. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 125. Copyright © 2015, American Chemical Society.

3.1.4. Peptide nucleic acid

Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) is an artificially synthesized nucleic acid analog in which the negatively charged sugar-phosphate backbone is replaced by N-(2-aminoethyl) glycine units linked by peptide bond128. Since PNA shares specific molecular recognition via the precise Watson–Crick base pairing and offers the advantages of peptides, more and more researchers have realized its potential in nucleic acid nanotechnology. Owing to many benefits, including high affinity and specificity to DNA or RNA, chemical stability, and resistance to nucleases and proteases129, peptide nucleic acid and DNA or RNA form a more stable double-stranded structure. Due to the excellent hybridization properties of PNA, many studies have focused on modifying various nanostructured materials with PNA chains to detect target RNAs, such as silicon nanowires130, gold nanoparticles131, metal–organic framework (MOF)132, and silver nanoparticles133,134.

For instance, Wu et al.132 presented a unique biosensor composed of PNA labeled with fluorophores and conjugated with MOF to detect multiplexed miRNAs in living cancer cells. The fluorescence of fluorophore-labeled PNA was quenched when PNA probes were firmly bound to the MOF nanostructure. Upon presentation of the target miRNA, the fluorophore-labeled PNA was released from the MOF structure and hybridized with the target miRNAs, leading to the recovered fluorescence signal. Inserting PNA molecules into DNA building blocks develops PNA-containing nucleic acid nanoassemblies with higher chemical and thermal stability. Lukeman et al.135 incorporated PNA into a DNA crossover-based molecule (DX molecule) to form 2D nucleic acid arrays. The DX molecule consists of two double-helical DNA domains linked by two crossover points. The structure of DX molecule can be elaborated by appending a hairpin between the two crossover points. The system will likely serve as a prototype for analyzing the helical repeat of a polynucleotide by atomic force microscope (AFM) images with few materials required135.

PNA molecules are also able to form hybrid-quadruplexes with DNA. Compared with the DNA-made quadruplex, the resulting hybrid-quadruplexes exhibited remarkably high thermodynamic stability. The hybrid-quadruplexes served as therapeutic targets or telomeres imaging agents136. Moreover, PNA could be used to precisely assemble peptides or proteins into dynamic structures. Flory et al.137 demonstrated an approach to fabricate nucleic acid–amino acid complexed 3D DNA nanocage using PNA to assemble peptides. The PNA peptides bound to the target DNA nanocage at room temperature in less than 10 min. Antisense peptide nucleic acids (asPNAs) are synthetic DNA analogs that specifically inhibit gene expression and can be used to control bacteria growth138. Since asPNA is not negatively charged, the stability and specificity of PNA binding are relatively high139. Lin and coworkers139 constructed a tetrahedral DNA nanostructure for the delivery of asPNA. The targeting gene was efficiently transported into bacteria cells and successfully inhibited gene expression in a concentration-dependent manner.

3.2. RNA nanoassemblies

3.2.1. RNA origami-derived nanoassemblies

RNA origami is a framework that can be folded from a single strand of RNA with the delicate design of nanostructures95. Unlike the existing DNA origami technology, RNA origami requires the participation of RNA polymerase, and a large amount of RNA can be folded into a specified shape simultaneously. In addition, RNA origami can be performed in living cells, using enzymes in the cells for production. Researchers may design RNA origami using 3D models and computer software and then synthesize DNA sequences that encode the RNA strand. By adding RNA polymerase to these synthesized DNAs, the fabrication of RNA origami can be performed automatically. A recent publication described RNA Origami automated design (ROAD) software, which built origami models from a library of structural modules, identified potential folding barriers, and designed optimized sequences140. Using the ROAD software, they extended the scale and functional diversity of RNA scaffolds, simplifying the construction of custom RNA scaffolds for further applications in nanomedicine and synthetic biology.

3.2.2. Rolling circle transcription-mediated RNA nanoassemblies

Enzymatic RNA polymerization via rolling circle transcription (RCT) has been reported for RNA nanoparticles141, 142, 143, 144. The conventional approach of RCT includes the replication of long RNA strands by two complementary circular DNAs. The two resulting RNA strands are able to bind together by RNA hybridization and self-assemble into an RNA architecture145. The size of RCT product can be controlled by increasing or decreasing the amount of polymerase during the reaction process68. Lee et al.144 proposed the synthesis of RNA interference (RNAi) polymers that self-assemble into nanoscale pleated sheets of hairpin RNA by RCT, which in turn form sponge-like microspheres. Direct transfection can be obtained by coating the polycation polyethylenimine (PEI) onto the microspheres. The enzymatic RCT reaction has excellent advantages in generating RNAi nanostructures at a low cost compared with chemical synthesis. Similarly, a siRNA-generating nanosponge was designed and fabricated through a complementary RCT process. Two complementary circular DNA templates were used to produce two long RNA strands. One DNA template contained the target mRNA sequence, and the other contained an entirely complementary sequence to the template. The resultant RNA strands hybridized to form double-stranded (dsRNA) and became entangled. This RNAi design approach could be universally applied to target any known mRNA sequences146.

3.2.3. phi29 pRNA-3WJ-based RNA nanoassemblies

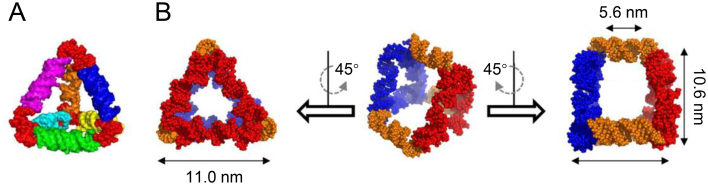

Shu et al.147 found that a few pieces of RNA oligomers from pRNA of bacteriophage phi29 self-assembled to form thermodynamically stable three-way junctions (3WJ). This pRNA-3WJ motif serves as a robust scaffold for designing and constructing RNA polygons148, 149, 150. In addition to 2D architectures, 3D RNA nanoparticles, such as tetrahedron (Fig. 5A)151 and prism (Fig. 5B)152, can also be constructed by phi29 pRNA 3WJ motif. Aptamers, ribozyme, and siRNA could be functionalized at the edges of RNA tetrahedrons with high precision without affecting the RNA nanostructure. When conjugating with human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeting aptamer, the RNA tetrahedrons may accumulate in orthotopic breast tumors without significant distribution in other organs151.

Figure 5.

phi29 pRNA-3WJ-based RNA nanoassemblies. (A) 3D computational model of RNA tetrahedrons. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 151. Copyright © 2016, John Wiley & Sons. (B) Computer model structure of RNA triangular nanoprism. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 152. Copyright © 2016, John Wiley & Sons.

3.2.4. RNA–protein nanostructures

Natural RNA often binds with proteins to form complexes with complicated structures and sophisticated functions (e.g., ribosomes), which has led to an interest in using RNA–protein complexes (RNPs)153. Saito, Inoue, and colleagues154 constructed equilateral triangular nanostructures using RNA and ribosome protein L7Ae. The triangle consists of three proteins bound to the RNA nanostructure. The L7Ae protein was bound to the kink-turn motif in the RNA, allowing the RNA to bend from a triangle. Later, they developed a tetragon-shaped RNA nanostructure composed of ribosomal protein L1 and RNA motif. AFM confirmed the formation of square-shaped nanostructure. RNA stability against nucleases was also improved by this RNA–protein nanostructure (Fig. 6)155. These RNP nanostructures potentially formed a multifunctional agent for biomedical applications.

Figure 6.

RNA–protein nanostructures. 3D model of square-shaped RNP nanostructure composed of RNA strand and Li protein. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 155. Copyright © 2015, American Chemical Society.

4. Properties and advantages of nucleic acid nanoassemblies

Nucleic acids have been widely explored to develop various exquisite nanoassemblies. Unlike other drug delivery systems, nucleic acid nanoassemblies exhibit excellent programmability, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. The programmability allows the precise engineering of nucleic acid nanoassemblies with controllable shapes, sizes, and functions. Nucleic acid nanostructures have demonstrated efficient cell internalization and recognition of certain molecules and membrane signals when functionalized with specific targeting ligands. Moreover, multi-functional payloads, controllable pharmacological profiles, and high detection rates can be achieved using nucleic acid nanoassemblies as carriers for theranostics. These merits allow them to be ideal carriers and probes for biomedical research and clinical diagnosis. Here in this section, we have summarized and discussed the basic properties and advantages of nucleic acid nanoassemblies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary on applications and advantages of nucleic acid nanoassembly-enhanced RNA theranostics.

| Research area | Application | Properties and advantage |

|---|---|---|

| RNA delivery | Delivery carriers for siRNA, shRNA, antisense, miRNA, mRNA, and CRISPR/Cas system | Excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability Programmability Narrow size distribution Efficient cell internalization Multi-functional payload Controllable pharmacological profiles Spatial confinement effect |

| RNA detection | Electrochemical and optical detection of miRNA and mRNA |

4.1. Excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and programmability

Compared to other polymer drug delivery carriers, the inherent biocompatibility and biodegradability are distinctive features of nucleic acid nanoassemblies. Ribonucleic acid is an important biopolymer made of oligonucleotides. Each DNA or RNA nucleotide comprises a sugar group, a nucleobase, and a phosphate group. Four possible nucleobases can be present in DNA, such as adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine, while RNA is adenosine, cytidine, guanosine, and uridine. With the high programmability of paring combinations between oligonucleotides, it is possible to achieve diverse DNA and RNA chains, providing an excellent platform to fabricate well-controlled and user-desired systems for efficiently delivering therapeutic RNA molecules.

4.2. Efficient cell internalization

Due to the phosphodiester bond in the backbone, DNA or RNA is negatively charged. The negative charge in the phosphate backbone disallows nonspecific targeting and minimizes the formation of protein corona that may affect targeted delivery68. Since the cell membrane is also electronegative, the electrostatic repulsion may hinder the nucleic acid molecule from entering the cell effectively without transfection reagents. However, recent studies have revealed that DNA nanoparticles reached intracellular organelles, such as endoplasmic reticulum and lysosomes, through a pinocytosis mechanism mediated by caveolin or clathrin156. Fan's team demonstrated that the self-assembled DNA nanoassemblies could be taken up by cells through endocytosis, showing the ability to enter cells more efficiently than single-stranded or double-stranded nucleic acid molecules. By single-particle tracking approach to tracking the cell entry pathway of DNA tetrahedrons, they demonstrated that DNA tetrahedrons, which are 7 nm in size, could be internalized by the caveolin-mediated pathway and degraded in a microtubule-dependent manner157. The efficient cell internalization is probably due to the programmed “like-charge attraction” at the interface of cytoplasmic membrane by DNA nanostructures. Tetrahedral DNA nanostructures approach the cell membrane primarily with their corners to minimize electrostatic repulsion. They also induce uneven charge redistribution in the membrane under short-distance confinement by caveolin158.

The extent of cell uptake is influenced by the size and shape of nucleic acid nanoassemblies. Multiple endocytic mechanisms may be involved in the cell uptake process for larger nanostructures. For example, the endocytic pathway of a 200 nm nano-self-assembly consisting of zinc and nucleic acids was investigated by Bull and coworkers159. The results demonstrated that macropinocytosis, clathrin-dependent endocytosis, clathrin-independent endocytosis, and direct transduction contributed to the cell uptake of Zn/DNA cluster159. Zhang et al.160 constructed a self-assembled quantum dot (QD) DNA hydrogel with an 80 nm diameter and elucidated the mechanism of its uptake in depth. The clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis were involved in the endocytic pathway of this hydrogel. Although the high aspect ratio of DNA nanotubes is attributed to higher cell uptake161, the geometries of DNA nanostructures underplay the need for a high aspect ratio162. In this study, Bastings et al.163 found that larger particles with greater compactness were preferentially internalized compared to hollow structures, such as cylindrical barrels or octahedrons. Besides the size and shape, specific targeting and enhanced cell internalization could be achieved by conjugating nucleic acid nanoassemblies with targeting moieties specific to receptors on cell membranes or functional groups responsive to external stimuli164, 165, 166. A few examples will be elucidated and discussed in Section 5.

4.3. Multi-functional payload

The precise treatment and diagnosis of diseases benefit from the combination therapy with multiple agents167,168, such as gene agents169, photosensitizers170,171, and contrast agents172. In recent years, researchers have designed and developed many static or dynamic nucleic acid nanoassemblies to carry small molecule drugs, antibodies, immune adjuvants, and siRNA into target cells and have achieved many encouraging results173. Due to the leaky vasculature and dysfunctional lymphatic system within a tumorous zone, the enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR) facilitated the retention and accumulation of nanomaterials in the solid tumor tissues174. However, more evidence now suggests that the active process of endothelial transcytosis might be the dominant mechanism of the extravasation of nanomaterials into the solid tumor tissues175. To enhance the specific targeting of nanomaterials, functional groups, such as aptamers, proteins, and receptors, can be seamlessly introduced into nucleic acid nanoassemblies176, 177, 178. The function of an RNA molecule mainly depends on the tertiary structure and encoded information179, 180, 181. Many functional modules composed of RNA, such as siRNAs, aptamers, and ribozymes, could be fused into the core sequences of RNA nanoassemblies while retaining their functionality68,147,182. For instance, Shu et al.182 reported the incorporation of pRNA-3WJ into fusion complexes harboring multiple RNA functionalities. When the functional therapeutic RNA moieties, such as ribozyme, siRNA, and aptamers, were fused to any of the three branches in the 3WJ motif, the incorporated RNA functional modules folded into their original structures with authentic functions.

4.4. Controllable pharmacological profile

One of the essential characteristics of nanomaterials is the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profiles, which mainly depend on the size and surface charge. To avoid rapid renal excretion and entrapment by liver Kupffer cells and macrophages, the adequate size of nanoparticles for phagocytosis ranges from 20 to 200 nm183, 184, 185. Most of the current nucleic nanoassemblies are main-ly designed within this size range. Specifically, unlike polymer nanoparticles, which are difficult to control the particle size consistently, nucleic acid nanoassemblies are usually designed and synthesized with narrow size distributions68. This consistency resulted in repeatable PK/PD profiles, allowing a better study of their in vivo therapeutic effect. The in vivo biodistribution and excretion of nucleic acid nanoassemblies were investigated by researchers. By positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, the rectangular DNA origami nanostructure has preferentially accumulated in the kidney, highlighting its potential role in renal-targeting delivery186,187. In another study, RNA nanoparticles constructed with a 3WJ motif are stretchable and shrinkable, like rubber or an amoeba. This rubber-like or amoeba-like deformation property enables RNA nanoparticles to squeeze out of the tumor vasculature and accumulate in the tumor tissue. In addition, it was demonstrated that 5, 10, and 20 nm RNA nanoparticles could be rapidly excreted by the renal with little accumulation in the body. These exciting findings illustrated that RNA nanoparticles exhibit high tumor-targeting efficiency and low toxicity in the body. Therefore, RNA holds excellent promises in developing cancer-targeting drug delivery systems188.

4.5. Space confinement effect

Hybridization chain reaction (HCR) has attracted great interest in detecting early-stage diseases. In the HCR process, recognizing the target triggered the chain reaction between two hairpin species. However, the random collision and interaction of two hairpins in a bulk 3D fluidic space may lead to longer response time and lower reaction velocity. DNA nanostructures could be employed as the skeleton and nanocarriers of desired hairpins and show great editability for controlling the spatial distribution of biosensors. Owing to the spatial confinement of DNA nanostructure, the collision frequency between hairpins was enhanced, resulting in accelerated reaction speed and improved reaction efficiency. He et al.189 constructed a DNA tetrahedron amplifier based on spatial confinement hairpin DNA assembly. The amplifier achieved efficient mRNA imaging and accelerated signal amplification for detecting tumor-derived mRNA. Liu et al.190 and Zhang et al.191 developed tetrahedral DNA framework-enhanced HCR probes for miRNA imaging and detection. These probes demonstrate outstanding potential for clinical diagnosis and therapeutic applications.

5. Nucleic acid nanoassembly-improved RNA therapeutics and diagnosis

The intrinsic features and properties make nucleic acid nanoassemblies to be potential drug delivery vehicles and biosensors for RNA-based therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. The recent applications of nucleic acid nanoassemblies for gene silencing, gene expression, gene editing, and RNA detection and imaging are introduced in this section. We have also included some examples of DNA and RNA nanoassemblies as delivery systems for RNA therapeutic strategies in Table 3119,126,127,167,192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201 and Table 4144,146,79,202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, respectively. Representative nucleic acid nanocarriers as biosensors for RNA detection approaches have been listed in Table 547,211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223.

Table 3.

Representative DNA nanoassemblies for RNA therapy.

| RNA payload | Nanoassembly and technology | Targeting ligand | Disease | Feature | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA | DNA nanorectangle and nanotube | DNA origami | Not applicable | SCLC (DMS53) and NSCLC (H1299) | 90% knockdown of Bcl-2 | 192 |

| DNA nanosuitcase | DNA polyhedron | Not applicable | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | Near 100% yield, cargo release on demand | 193 | |

| DNA nanoclew | RCA | Not applicable | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | Metal- or cation-free conjugation | 126 | |

| Oligonucleotide nanoparticle | DNA polyhedron | 28 different targeting ligands | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (KB) | FA-conjugated tetrahedron exhibited the greatest gene silencing | 119 | |

| DNA nanotube | DNA polyhedron | Aptamer | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) and human acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Cell-subtype discrimination and precise siRNA delivery for efficient gene silencing | 194 | |

| DNA nanodevice | DNA origami | TAT peptide | Human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) | GSH-triggered drug release, combination of RNA interference and chemotherapy induced potent tumor growth inhibition | 167 | |

| shRNA | Not applicable | DNA origami | Aptamer | Human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) | Marked antitumor effect against multidrug-resistant tumor | 195 |

| Antisense | DNA tetrahedron | DNA polyhedron | Nuclear localization signal peptide | Lung adenocarcinoma (A549) | In response to the intracellular reductive microenvironment | 196 |

| DNA Cages | DNA polyhedron | Not applicable | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | DNA-economic, efficient knockdown | 197 | |

| mRNA | DNA nanogel | RNA–DNA hybridization | Not applicable | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | pH-responsive mRNA release under acidic condition | 198 |

| Cas9/sgRNA | DNA nanoclew coated with PEI | RCA | Not applicable | Osteosarcoma (U2OS) | Balancing binding and release of Cas9/sgRNA complex by nanoclew | 127 |

| DNA–PCL nanogel | RNA–DNA hybridization | Not applicable | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | Excellent physiological stability against nuclease digestion | 199 | |

| Cas9/sgRNA and antisense | Branched DNA based-nanoplatform | RNA–DNA hybridization | Aptamer | Human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) | Synergistic tumor therapy of gene editing and gene silencing | 200 |

| Cas12a/crRNA | DNA nanoclew | RCA | Galactose | Osteosarcoma (U2OS) | Chol regulation, efficient Pcsk9 disruption | 201 |

Table 4.

Representative RNA nanoassemblies for RNA therapy.

| RNA payload | Nanoassembly and technology | Targeting ligand | Disease | Key finding | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA | DNA/RNA hybrid nanoparticle | RCT and RNA–DNA hybridization | Chol and FA | Ovarian cancer (SKOV3) and lung adenocarcinoma (A549) | Low cost, directly accessible routes to targeted and systemic delivery | 202 |

| RNA nanoring and nanocube | RNA tectonics | Not applicable | Human breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231/GFP) | Co-transcriptional assembly | 203 | |

| RNA nanoring | RNA tectonics | Aptamer | HIV-1 and human breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231/GFP) | Functionalization with different classes of molecules | 204 | |

| RNA nanoring | RNA tectonics | Not applicable | Not applicable | Thermostable and ribonuclease resistance | 79 | |

| Equilateral triangular nanoassembly | L7Ae-based RNA–protein complex | Peptide | Human breast adenocarcinoma (SKBR3) | Protein-controllable assembly | 205 | |

| PEI-layered microsponge | RCT | Not applicable | Ovarian cancer (T22) | Self-assemble and efficient delivery of siRNA | 144 | |

| RNA nanosponge | RCT | Not applicable | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | Universal approach to manipulate gene expression | 146 | |

| Anti-miRNA | RNA micelle | 3WJ RNA nanotechnology | FA | oral squamous cell carcinoma (KB) and colon cancer (HT29) | Strong binding and internalization to cancer cells | 206 |

| RNA nanoparticle | 3WJ RNA nanotechnology | Aptamer | Human breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231) | High specificity in TNBC tumor targeting | 207 | |

| miRNA | RNA nanoparticle | 6WJ RNA nanotechnology | Not applicable | Liver cancer (HepG2) | Rubber-like properties, co-delivery of paclitaxel and miRNA | 208 |

| mRNA | RNA nanoassembly | RNA–DNA hybridization | Not applicable | Not applicable | RNase stability, selective RNA dissociation intracellularly | 209 |

| Cas9/sgRNA and siRNA | Poly-ribonucleoprotein nanoparticle | RCT | Not applicable | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | More efficient than cationic non-viral gene delivery system, dicer specific cleavage | 210 |

TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; 6WJ, six-way junctions.

Table 5.

Representative nucleic acid nanoassemblies for RNA diagnosis.

| Nucleic acid nanoassembly | Detection method | Mechanism | Limit of detection | Disease | Feature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA tetrahedron | Electrochemical | HRP | 10 fmol/L | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | PCR-free | 211 |

| Electrochemical | HRP | 10 fmol/L | Pancreatic carcinoma | Simultaneously detect four miRNAs | 212 | |

| Electrochemical | Ag/AgCl reaction | 0.4 fmol/L | Human breast adenocarcinoma | Recycling of microRNA | 213 | |

| Electrochemical | HRP | 0.1 fmol/L | Not applicable | Superb tacticity and stereochemical conformality | 214 | |

| Electrochemical | HRP and HCR | 10 amol/L | Not applicable | HCR amplification | 215 | |

| Electrochemical | HCR | 12.17 amol/L | Not applicable | Ratiometric electrochemiluminescence-electrochemical hybrid biosensor | 47 | |

| DNA walking machine | Electrochemical | Surface plasmon resonance | 1.51 and 1.67 fmol/L | Not applicable | Enzyme-free | 216 |

| Electrochemical | Surface plasmon resonance | 3.3 fmol/L | Human prostate cancer (22Rv1) and cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | “On-off-super on” | 217 | |

| Optical | RCA | 58 fmol/L | Not applicable | Rapid, sensitive, specific and economical | 218 | |

| DNAzyme ferris wheel | Optical | HRP mimicking catalysis | 0.5 pmol/L | Human prostate cancer (22Rv1) and cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | Non-enzyme colorimetric detection | 219 |

| DNA tetrahedron/Au Nps | Optical | Fluorescence | 8.4 amol/L | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | Multiple miRNA detection | 220 |

| DNA/Au Nps/QD assembly | Optical | Photoluminescence | 4.6 pmol/L | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) and human breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231, MCF-7) | Live cell compatible | 221 |

| Upconversion NP-based DNA nanomachine | Optical | Fluorescence | 3.71 pmol/L | Cervical carcinoma (HeLa) | Live cell compatible, imaging of intracellular miRNA | 222 |

| DNA nanoprobe | Optical | Fluorescence | 200 pmol/L | Human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) and lung cancer (A549) | Live cell compatible, self-delivery | 223 |

5.1. Gene silencing

5.1.1. Nucleic acid nanoassemblies for siRNA delivery

RNAi is an ancient defense mechanism for external invasion3,224, which was first discovered by the Fire and Mello research team in Caenorhabditis elegans in 1998225. RNAi has been widely used to manipulate gene expression. When exogenous double-stranded genes (dsRNA) enter the cells for transcription, they are cut into siRNA with a specific length by the endonuclease Dicer. The cleaved siRNA can be melted into a sense strand and an antisense strand by the helicase in the cytoplasm, where the sense strand is cut into fragments, and the antisense strand is combined with the RISC containing various nucleases. It specifically binds to its targeted mRNA to induce efficient cleavage and degradation of mRNA, thereby inhibiting protein expression226,227. In addition to the above regulatory mechanisms, antisense strand nucleic acids regulate gene transcription through steric hindrance, achieving alternative splicing of RNA precursors and inhibiting protein translation228. Elbashir et al.229 further pointed out that introducing the cleaved siRNA sequences directly into the cell avoided the Dicer enzyme-catalyzed reaction, thereby achieving a better gene silencing effect.

Currently, the commonly delivered sequence of siRNA therapy is a functional nucleic acid molecule composed of 21–23 base double-stranded RNA230,231. The most prominent feature of siRNAs is their versatility. Changing the sequence design of siRNA makes it very convenient to realize the regulation of different target genes, inhibit the synthesis of corresponding proteins, and the proliferation of cells, such as cancer cells. In 2018, the first commercial siRNA-based therapeutic drug, ONPATTRO® (patisiran, ALN-TTR02), was approved by FDA and the European Commission4,232. Although siRNA holds great potential in drug development, several barriers hinder its extensive clinical applications. For example, siRNA can be quickly degraded into fragments after exposure to endonucleases or exonucleases, thus inhibiting the accumulation of enough therapeutic drugs in the target tissue. Moreover, the instability under nuclease and poor pharmacokinetic behavior may cause unsatisfied gene silencing233.

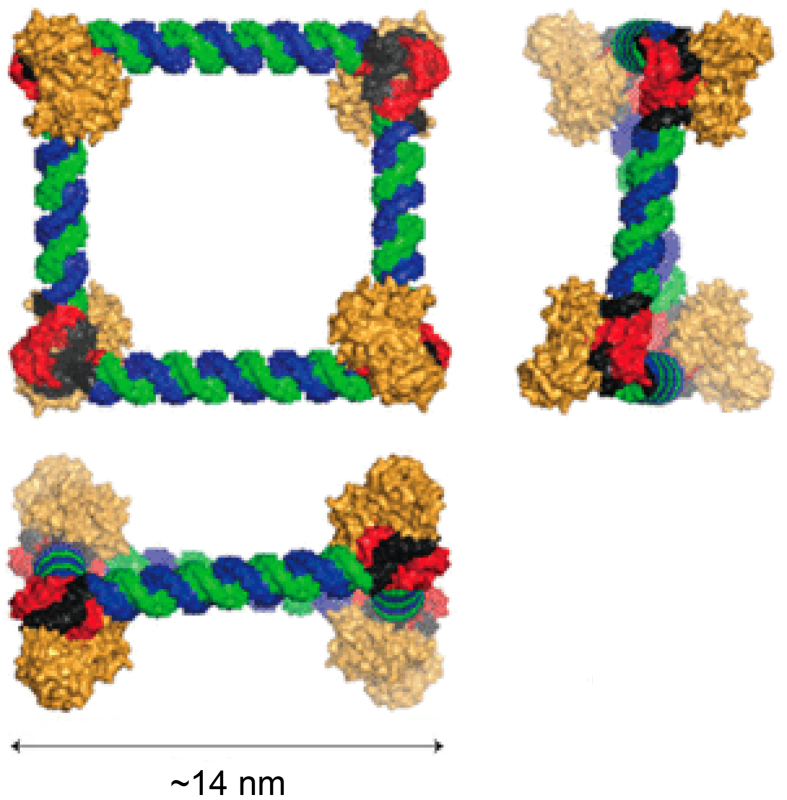

DNA nanoassemblies protect siRNA from degradation efficiently and consequently facilitate gene silencing. Rahman et al.192 constructed DNA nanoparticles with rectangular or tubular shapes to deliver B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) siRNA. Those DNA nanoparticles were self-assembled from short DNA strands and achieved high yields of different structures. All the DNA nanoparticles exhibited efficient cell uptake and 70% silencing of Bcl-2 mRNA. The systemic delivery of Bcl-2 siRNA in mice showed significant tumor growth inhibition and low toxicity. Although DNA origami structures load and release siRNAs, their structures are composed of hundreds of DNA strands, complicating their applications. As an alternative, Bujold et al.193 identified the minimum number of DNA components required for siRNA delivery. They designed and optimized a trigger-responsive siRNA-encapsulating DNA “nanosuitcases”. The nanostructure protected siRNA and selectively release it in the presence of chosen trigger stands, Bcl-2 and/or Bcl-xL, in different microenvironments (Fig. 7A–C).

Figure 7.

DNA “nanosuitcases” encapsulated with trigger-responsive siRNA. (A) Scheme illustrating self-assembly of “nanosuitcases” and siRNA release mechanism. (B) Potency of elongated luciferase siRNA. (C) Serum stability of siRNA-containing prism in biological conditions. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 203. Copyright © 2016, American Chemical Society.

Compared to DNA polyhedron and origami, the construction of RCA-based spherical nanostructure is simple and efficient. Ruan et al.126 immobilized siRNA onto the surface of a DNA nanoclew formulated by RCA. The tunable size of DNA nanoclew can be controlled by variation of amplification time. The size of the nanoclew product was 68 nm, as detected by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Then siRNA was engrafted onto the nanoclew by annealing. The complex of siRNA and DNA nanoclew can be efficiently taken up by cancer cells and released within cells under endogenous Dicer digestion. Without inducing toxicity, the DNA nanostructure demonstrated potent gene knockdown at both mRNA and protein levels. Although linear nucleic acids cannot enter cells quickly without the help of a transfection agent19,30,234, the spherical nucleic acids (SNA) generated by RCA can be recognized by class A scavenger receptors, resulting in internalization by different cell types in the absence of transfection agents126,235,236. In addition, compared to the rapid degradation of linear nucleic acids, SNA helped the loaded therapeutic RNA from potent enzymatic degradation in the blood circulation18,237, 238, 239. These superior advantages endow SNAs with a high potential for therapeutic RNA delivery in the disease treatment field.

It is hypothesized that intracellular delivery of siRNA nanoparticles can be promoted by active targeting to the specific surface receptors on cancer cells240,241. To ascertain whether targeted delivery of siRNA to cancer cells can be achieved, Lee et al.119 conjugated various cancer-targeting ligands on oligonucleotide nanoparticles. FA-conjugated nanoparticles exhibited the most effective gene silencing conjugated various cancer-targeting ligands on oligonucleotide nanoparticles among the 28 targeting ligands (from peptides to small molecules) tested. More than 50% gene reduction was observed in HeLa cells in a dose-dependent manner. Aptamers were also well explored as active targeting ligands. Ren et al.194 constructed a DNA dual “lock-and-key” strategy for siRNA delivery. A hairpin structure was functionalized on an oligonucleotide vehicle to act as a “key” in their system. Two kinds of aptamers were bonded on the cell surface to serve as the double “locks”. The dual recognition mode induced the “locked-open” status and achieved cell-specific recognition and precise siRNA delivery.

Although several targeting ligands that selectively bind cell or tissue-associated receptors (e.g., folate (FA), antibody-protamine fusion proteins, and aptamers) have been investigated for targeted delivery of siRNA240,242, 243, 244, most of the receptors are often expressed by multiple cells. Some of the receptors overexpressed in disease conditions are also expressed in normal tissues245. Therefore, a single receptor-targeted delivery strategy may produce an off-target effect and severe toxicity. Stimuli-responsive DNA-self-assembled systems that enable siRNA release in certain conditions may address the challenges of targeted delivery and controlled release246. Wang et al.167 constructed a DNA origami incorporated with disulfide bond to deliver siRNA and the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin using a DNA origami technique. The DNA nanodevice allowed the triggered release of siRNA in response to glutathione (GSH) levels in the tumor cells. As trans-activator of transcription (TAT) peptides are able to enhance the cell internalization performances of nanoparticles247, they decorated the nanodevice with 28TAT peptides. The combination of stimuli-responsive ligands and TAT peptides helped to avoid undesirable toxicity and enhance cancer treatment efficiency.

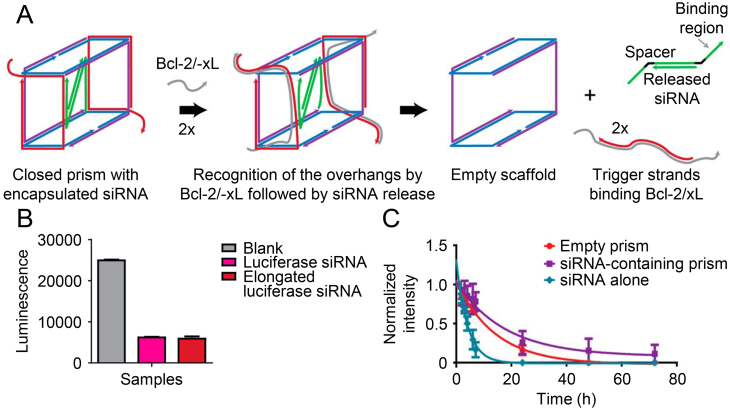

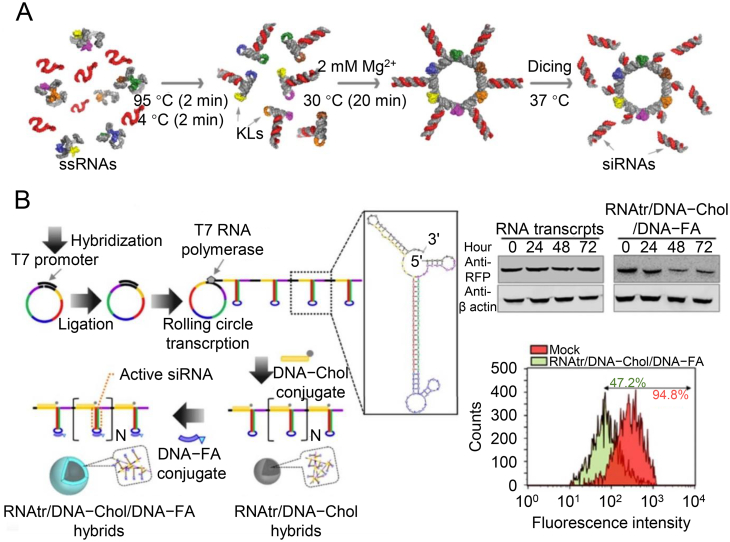

RNA nanoassemblies have also been applied for siRNA delivery. Based on the principles of RNA architectonics, the single-stranded RNAs form monomers with prefolded structural motifs followed by bottom-up assemblies79. Shapiro and colleagues204 developed RNA nanorings functionalized with multiple siRNAs simultaneously (Fig. 8A). They also demonstrated that the incorporation of RNA aptamers specific to EGFR achieved cell-targeting properties. Jang et al.202 polymerized RNAs via RCT and hybridized them with DNA–cholesterol (DNA–Chol) and DNA–FA conjugates. The simple design for coating the targeting ligands facilitated the receptor-dependent cell uptake and consistent accumulation at the tumor sites (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

RNA nanotechnology for siRNA delivery. (A) RNA nanorings functionalized with multiple siRNAs, promoting cell transfection and gene knockdown. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 219. Copyright © 2014, American Chemical Society. (B) Polymerized RNAs via RCT and hybridized with DNA–Chol and DNA–FA conjugates, silencing RFP gene. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 220. Copyright © 2015, Nature Publishing Group.

5.1.2. Nucleic acid nanoassemblies for other RNA silencing delivery

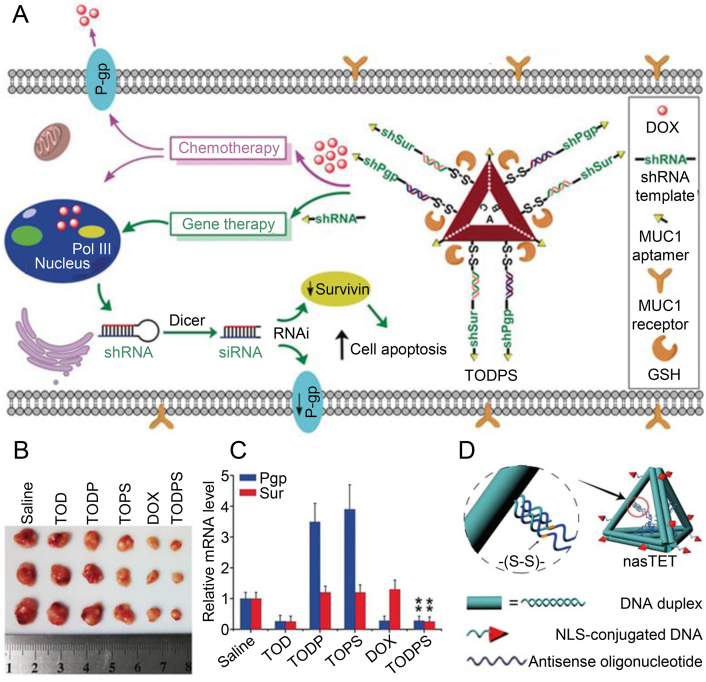

The rationally designed multifunctional DNA nanostructure-based siRNA delivery systems promoted cell growth inhibition in the tumor tissues. In addition to siRNA, small hairpin RNA (shRNA) transcription templates with enhanced stability are also a candidate to elicit significant gene silencing. Yang et al.196 developed a method to co-deliver linear shRNA transcription templates and chemotherapeutic drugs into drug-resistance cancer cells. The shRNA transcription templates were designed against multidrug-resistant (MDR) associated genes, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and survivin, and hybridized with transmembrane glycoprotein Mucin 1 targeting aptamer. Due to the cleavable capture strands, the DNA nanostructure can be spilled into two components after incubation with GSH. After administering multifunctional DNA nanoassemblies containing gene-silencing elements and chemotherapeutic drugs, researchers achieved a significant antitumor effect against MDR tumors in vivo. Their drug delivery systems can be adapted to deliver gene-editing systems, immune-related adjuvants, and antibody-based drugs as well (Fig. 9A–C).

Figure 9.

DNA nanoassembly for shRNA and DOX delivery. (A) DNA origami-based nanostructure for shRNA and chemotherapeutic drug delivery against a multidrug-resistant tumor. (B) Tumor inhibition by DNA origami-based nanostructure. (C) Relative mRNA levels (down expression) of P-gp and surviving genes in mice treated with DNA origami-based nanostructure. (A–C) Reproduced with permission from Ref. 221. Copyright © 2018, John Wiley & Sons. (D) Multifunctional double-bundle DNA tetrahedron for ASOs delivery. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 222. Copyright © 2018, American Chemical Society.

ASOs that are complementary to the target mRNA sequence can also be used to regulate gene expression. For the first time, Yang et al.196 reported that a double-bundle DNA tetrahedron-based ASO delivery system silenced proto-oncogene C-RAF into live cells. The DNA tetrahedron was functionalized with a nuclear location signal peptide that helps to deliver ASOs toward the nucleus. Subsequently, the disulfide bonds in ASOs induced the release of ASOs in response to the reductive microenvironment (Fig. 9D). The expression of miRNAs is closely associated with tumor progression. For example, the overexpression of miRNA21 in the tumor tissue is correlated to tumor proliferation and apoptosis through phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN), programmed cell death protein 4 (PDCD4), and other signal transduction pathways248, 249, 250. Yin et al.206 constructed an RNA micelle platform to deliver anti-miR21 for inhibiting miR21 and inducing the apoptosis of tumor cells. The RNA micelle exhibited better tumor tissue targeting and accumulation in a mouse xenograft model. Even without a targeting ligand, the RNA micelles were able to inhibit tumor growth significantly.

5.2. Gene expression

In recent years, in vitro transcribed mRNA has come into focus as a promising unique therapeutic agent. In 1990s, Wolff et al.251 demonstrated that direct injection of mRNA into the skeletal muscle of mice induced gene expression of the encoded protein in the injection site. Since then, many preclinical studies of mRNA have been initiated for several applications, including vaccination approaches and protein substitution for diverse diseases252, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 258, 259, 260. Compared to DNA therapeutics, mRNA can be translated into cytoplasm directly, therefore, does not need to enter the nucleus to be functional. Consequently, mRNA induces rapid protein expression even in difficult-to-transfect cells, such as immune cells261. In addition, mRNA-based therapeutics do risk insertional mutagenesis because they do not integrate into the host genome262. The advantages mentioned above make mRNA a potent candidate for the development of RNA therapies. However, mRNA is less stable than DNA and may completely degrade via physiological metabolic pathways. Therefore, efficient drug delivery systems must protect mRNA from degradation and facilitate mRNA to pass the cell membrane.

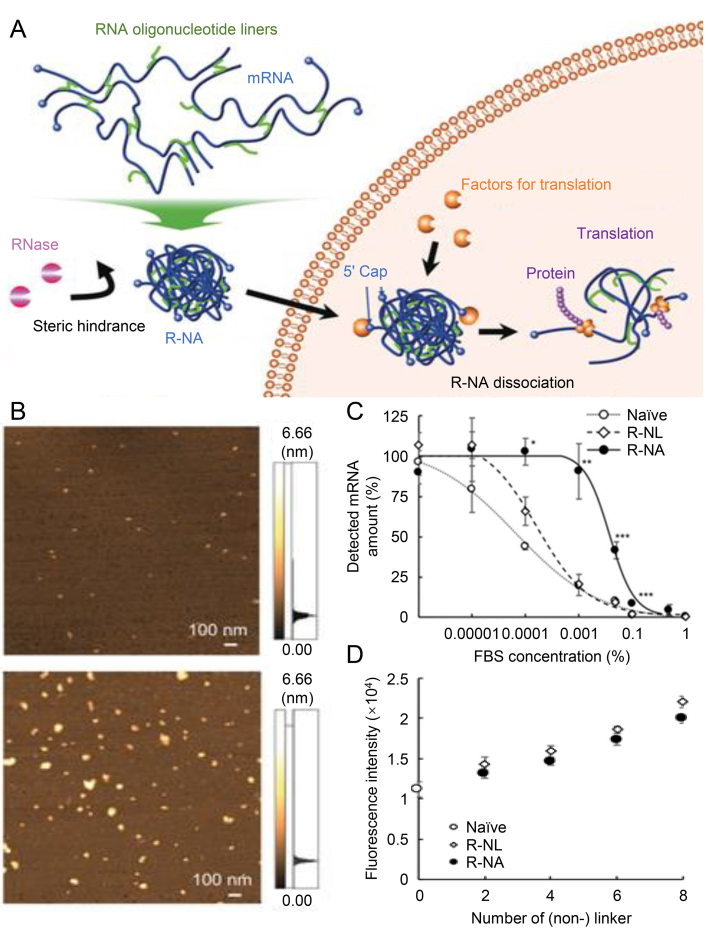

Researchers have developed many delivery vehicles for mRNA therapies, such as lipid-based nanoparticles, polymer nanoparticles, and virus-like particles263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268. At the same time, mRNA modification strategies have been well explored for reducing their immunogenicity269. Although these strategies have been promising, more efficient approaches for mRNA delivery are still needed before reaching the clinical stage. Rolling circle replication has been shown to assemble long DNA and RNA strands into microstructures144,270. Kim et al.271 reported a unique strategy for efficient mRNA delivery by RCT to produce proteins in cells. The self-assembled RNA nanostructure was generated by T7 RNA polymerases that transcribed mRNA strands with the plasmid DNA as the template DNA. A green fluorescence protein (GFP)-encoding plasmid DNA containing the promoter region for T7 polymerase was designed for the RCT process. Due to the increased nuclease resistance, the mRNA nanostructure allowed for prolonged and higher protein expression. Without RCT, Fu et al.198 developed another smart responsive DNA nanogel to deliver mRNA into cells. A specific DNA quadruplex structure, I-motif, was adopted due to its pH-responsive behavior. A well-designed “X”-shaped DNA scaffold and I-motif were crosslinked to form a compact nanogel. Under an acidic microenvironment, the nanogel disintegrated in the lysosome and release mRNA for protein expression. The translation efficiency of this system was comparable to the commercial liposome transfection agent but with lower toxicity and higher biocompatibility. Yoshinaga et al.209 tackled the issue of mRNA degradation by constructing a unique mRNA nanoassembly (R-NA). In their strategies, RNA linkers, an RNA chain that is complementary to mRNA, hybridized the mRNA molecules in different positions. This straightforward mRNA-engineering approach promotes the RNase stability of mRNA by approximately 100-fold (Fig. 10A–D).

Figure 10.

DNA nanoassembly for mRNA delivery. (A) Schematically illustrating a strategy for mRNA delivery by binding mRNA into nanoassembly. (B) AFM images of naïve mRNA (top) and R-NAs (bottom). (C) Serum stability of mRNA toward RNase. (D) Quantification of dsRNA amount using ethidium bromide. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 249. Copyright © 2019, John Wiley & Sons.

5.3. Gene editing

Gene editing is an emerging and accurate genetic engineering technology that modifies specific target genes in the genome of organisms. The most widely explored gene editing system, CRISPR/Cas genome editing system, has attracted tremendous interest and generated numerous research publications272, 273, 274. In this system, a Cas nuclease guided by a single guide RNA (gRNA) is able to cleave a target gene sequence by base-paring of gRNA and the target DNA sequence275.

As the CRISPR/Cas platform undergoes further development for disease therapy, efficient delivery systems pose a significant challenge. Although the CRISPR/Cas system greatly facilitates gene editing, it also has certain limitations. For instance, sgRNA and Cas9 have been frequently encoded within the plasmid DNA, leading to a higher potential for genome integration276,277. Furthermore, the template-driven approach limits control over the total amount of Cas9 protein and sgRNA, and the excess dosing may induce off-target cleavage278. Alternatively, a CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex enables direct gene editing after entering the cells and is supposed to cause the least off-target effect279. Sun et al.127 reported a yarn-like DNA nanoclew synthesized by RCA to deliver Cas9 protein together with sgRNA for gene editing. After loading the DNA nanoclew with Cas9/sgRNA, they applied a cationic PEI coating to induce endosome escape through the “proton-sponge” effect. The partial complementarity between the single-stranded DNA and Cas9/sgRNA greatly enhanced the extent of genome editing. Similarly, Ha et al.210 reported an RCT approach to deliver the CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex. Interestingly, they incorporated a Dicer substrate siRNA following the sgRNA sequence into the template sequence for RCT. Thus, the Dicer would cleave the poly-ribonucleoprotein nanoparticles after intracellular delivery. Those nanoparticles containing siRNA sequences led to improved disruption rates of the target gene and the protein expression levels compared to nanoparticles without such sequences. They also provide a potential tool to simultaneously deliver multiple sgRNAs at a specific ratio.

Despite spherical nucleic acid based on RCA/RCT, DNA-based nanocarriers can be tailored to target the terminal of sgRNA through complementary base pairing. For example, Ding et al.199 developed a nucleic acid nanogel for the intracellular delivery of Cas9/sgRNA complex. In their system, the Cas9/sgRNA complex was loaded inside the nanogel. Therefore, it can be protected and rapidly delivered into the cells. The nanogel consisting of DNA-grafted poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), DNA linkers, and the Cas9/sgRNA complexes were assembled via nucleic acid hybridization. The brushed DNA on DNA-grafted PCL was complementary to the terminal of sgRNA, which is exposed from the Cas9/sgRNA complex. The nanogel was tolerable to nuclease in a short time, while it can also be released in the presence of intracellular nuclease. Based on this merit, the Cas9/sgRNA-loaded nanogel enables efficient genome editing in vitro in cancer cells. Targeting ligands could be conjugated on DNA-based nanocarriers to promote the delivery of Cas9/sgRNA system. Liu et al.200 described a branched DNA nanostructure to deliver sgRNA/Cas9/antisense for synergistic cancer therapy. The nanostructure containing aptamer and influenza hemagglutinin peptide was designed for targeted delivery and endosome escape. The two disulfide linkages within the nanostructure efficiently released the protein and RNA through GSH and RNase H digestion. Finally, Cas9/sgRNA and antisense achieved a remarkable antitumor effect. There have been a lot of efforts reporting the delivery systems of Cas9/sgRNA. However, only a few studies were focused on the delivery and administration systems of the Cas12a/crRNA ribonucleoprotein, including the gold nanoparticles and electroporation approach280,281. Gu, Sun, and colleagues201 prepared a DNA nanoclew coated with a cationic layer of PEI to allow the administration of Cas12a/crRNA complex. Interestingly, an anionic polymer layer harboring charge reversal behavior was coated on the surface of PEI/DNA nanoclew. Moreover, a hepatocyte-targeted ligand, galactose, was conjugated to the anionic layer of nanoclew to enable the active targeting of hepatocytes through systemic administration. Because of the negative charge and charge-reversal behavior of anionic coating at physiological pH, the DNA nanoclew circulated in the blood with high biocompatibility while releasing the Cas12a protein and crRNA into the acidic microenvironment of endosomes after internalizing into hepatocytes.

5.4. RNA diagnosis

Early diagnosis of many diseases, especially cancer, profoundly impacted survival rates and maximize positive outcomes282. Until now, thousands of miRNAs have been identified in the human genome, and more than 60% of human protein-coding genes have been under selective pressure to maintain paring to miRNAs283. Since miRNA plays vital roles in biological processes, they could be potential diagnostic markers for several diseases284. For instance, accurate detection and imaging of miRNAs in live cells are significant for early cancer diagnosis285. However, the short length and sequence similarity of miRNA detection remain a technical challenge due to the low abundance. Northern blotting, the widely accepted gold standard for miRNA detection, is both time- and labor-intensive, making it inappropriate for routine applications. Other alternative methods, such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)286, the isothermal amplification methods287,288, and the hybridization-based microarray technology289, 290, 291, barely meet the high standards for point-of-care testing of miRNA. Ideal miRNA detection testing requires sufficiently high sensitivity and selection to detect very minute RNA with low cost and portability for routine clinical applications. Nucleic acids are the natural biosensors for miRNAs. Therefore, their nanoassemblies have served as detection sensors for miRNAs24.

In addition to miRNA, the expression level of cancer-related mRNA reveals important information about cancer progression and prognosis292. Detection of intracellular RNA expression levels is of great significance for cancer diagnosis. Researchers have explored numerous approaches for endogenous mRNA identification and characterization, such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)293 and microarray assays294. However, these methods cannot reveal the transient changes in RNA in living cells. The loss of important biological information due to the lack of detection methods has prompted people to seek alternative ways to detect mRNA in living cells. In this regard, detecting probes based on nucleic acid nanostructures may be attractive technologies for detecting mRNA in living cells because of their high sensitivity, real-time and in situ monitoring capabilities, and low cytotoxicity. Herein we have grouped the RNA detecting strategies by sensing approaches (electrochemical and optical) and included the representative examples in Table 547,211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223.

5.4.1. Electrochemical approaches

DNA tetrahedron has been one of the most commonly used nucleic acid nanoassemblies with good rigidity, excellent cell permeability, and enzyme resistance295. Therefore, the DNA tetrahedron-based electrochemical sensors have been used for miRNA sensing. Fan's group211 developed a 3D DNA nanostructure-based sensor platform for PCR-free miRNA detection. The base-stacking strategies were employed to design the electrochemical miRNA sensor. In the electrochemical sensor, a capture probe appended to one vertex of the tetrahedron-structured probe is complementary to the target miRNAs. The thiol groups of tetrahedron structure at the other three vertices were immobilized at the Au surface. A biotin-tagged DNA strand was the signal probe, which was complementary to the miRNA sequence. A sandwich structure can be obtained by the base-paring between the probes and miRNA sequence. At the end of signal probe, the biotin tag specifically binds to avidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and generates quantitative electrochemical signals.

Several researchers have investigated the variation of detection probe. Zeng et al.212 employed DNA tetrahedron probes and a disposable 16-channel screen-printed gold electrode detection platform to detect four pancreatic carcinoma-related miRNAs, such as miRNA21, miRNA155, miRNA196a, and miRNA210. Based on the binding of polyHRP40 onto a gold electrode surface that generated catalytic amperometric readout, the limit of detection is as low as 10.0 fmol/L. Finally, they profiled serum levels of the four miRNA for eight pancreatic carcinoma patients and eight healthy controls with this electrochemical miRNA biosensor. Ge et al.215 fabricated a DNA tetrahedron-based biosensor to detect DNA and miRNAs. Upon the capture of miRNA, an HCR process was initiated by biotin-modified hairpin substrates. The recruited multiple HRP molecules enhanced the limit of detection down to 10.0 amol/L for miRNA. Some electrochemical approaches have been designed to proceed without using HRP. Miao et al.213 fabricated an electrochemical biosensor for the ultrasensitive detection of miRNA based on tetrahedral nucleic acid nanostructures. The strand displacement polymerization is employed to lead to the recycling of miRNA. Taking advantage of the solid-state Ag/AgCl reaction, the biosensor exhibited high sensitivity with the limit of detection low to 0.4 fmol/L. This approach offered excellent performance for detecting miRNA from breast cancer patients.

To increase the detection sensitivity and accuracy of the electrochemistry-based biosensor, a unique and elaborate electrochemiluminescence (ECL)-electrochemical (EC) ratiometric biosensor based on a DNA tetrahedral platform and HCR amplification was fabricated. A hairpin DNA (miRNA-helper) was designed and synthesized, which is complementary to the target miRNA sequence. Two Ru (bpy)32+-labeled hairpins were used as the detection probes. Upon the presentation of miRNA-133a, it hybridized with the miRNA helper, resulting in an HCR process to obtain an amplified signal. To enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of target miRNA, methylene blue was tagged with the miRNA-helper, which generated an independent signal of the concentration of miRNA-133a and reflect the real-time state of electrode surface. The final quantitative analysis of target miRNA can be achieved by measuring the signal ratio of Ru and methylene blue47.

Due to remarkable regulation and elasticity, a DNA walking machine, consisting of a biped and a well-defined track, has been investigated for RNA detection. Yuan's group217 fabricated an ECL sensor combined with a 3D DNA walking machine and an “on-off-super on” strategy for detecting miRNA. The walking machine was immobilized on Au@Fe3O4 with a relatively large surface area and easy magnetic separation. Upon presentation of the target miRNA, the walker probe was released by protecting probe. The released walker probe was then paired with the support probe to form the recognition site for Nt.BsmAI. Subsequently, the intermediate DNA was released under the shearing of Nt.BsmAI nicking endonuclease, triggering the following ECL signal. The signal was generated by distance-based energy transfer between CdS:Mn QDs and Au nanoparticles. As a result, a “super on” state signal was obtained by the excited surface plasma resonance of AuNPs from CdS:Mn QDs. The “on-off-super on” device provided a sensitive and efficient way for miRNA-based cancer diagnosis and circumvented the false-positive signal. Without the Nt.BsmAI nicking endonuclease, Yuan's group216 has also fabricated a bi-directional DNA walking machine for sensitive detection of two different miRNAs. The detection limit is as low as 1.51 and 1.67 fmol/L for miRNA-21 and miRNA-155, respectively.

Exosomes have been recognized as extracellular organelles that carry multiple signaling biomolecules, including protein, mRNA, and microRNAs296, 297, 298, 299, 300. Liu et al.301 developed a “sandwich-type” ECL biosensor that harmonized PNA and SNA nanoprobe to improve the detection specificity and efficiency of target miRNA in exosomes. After collecting tumor exosomes from blood and extracting the miRNA. The target miRNA prehybridized with SNA to form conjugates. Then electrode surface-assembled PNA probes specifically recognized the complexity of miRNA and SNA by forming a PNA–miRNA–SNA construct. A large amount of RuHex cations then electrostatically bind to the negatively charged construct, quantifying the DNA strands. The PNA probe afforded a neutrally charged surface that primarily improves the specific recognition and hybridization strength of miRNA molecules, while SNA loads dense signaling molecules for signal amplification.

5.4.2. Optical approaches

Beyond electrochemical sensing, nucleic acid nanoassemblies have been used in optical properties to generate fluorescence220, luminescence221, and colorimetric signals. Zhou et al.219 constructed a miRNA-triggered DNAzyme Ferris wheel for colorimetric detection of miR-141 in human prostate cancer cells. The nanoassembly mimiced the HRP activity and catalyzed an intensified color transition of the sample solution219. Li's group218 fabricated a DNA walking machine based on the RCA reaction and enzymatic recycling cleavage strategy. The RCA strategy was applied to amplify the output of DNA walking machine. Then a molecular beacon and the RCA product hybridize to form double sequences, which can be recognized by the DNA-nicking enzyme to generate a fluorescence signal.

Though many RNA biosensors amplify the existence of a low amount of RNA to an intensive fluorescence signal, most of them are not suitable for intracellular RNA imaging. Detection of specific cell RNA is challenging because it requires delivery approaches to access the cytoplasm, where most mature mRNA or miRNA are located. DNA-based fluorescence probes have been used for RNA imaging due to their non-invasive and quantitative capability. Chen et al.223 developed a DNA nanoprobe for cancer-related miRNA detection and bioimaging. The nanoprobe was composed of a Y-shape and pyrene-modified DNA self-assembly. Taking advantage of the pyrene-excimer strategy, the DNA nanoprobe generated accurate signal output and avoided the false-positive results caused by nuclease digestion. The probe showed good cell permeability and bio-stability, resulting in a high resolution of the miRNA imaging.

Zhang et al.222 constructed a photo zipper-locked DNA nanomachine for precise intracellular miRNA imaging. The nanomachine was composed of upconversion nanoparticles with surface functionalization of a DNA walker and its corresponding substrate strands labeled with quencher BHQ2. Cy3 was immobilized on the surface of upconversion nanoparticles, which facilitated energy transfer under near-infrared (NIR) light irradiation. The nanomachine provided precise intracellular imaging of the target miRNA. Ren et al.302 designed “nano string light” for mRNA imaging based on DNA cascade reaction along a DNA nanowire. The “nano string light” was fabricated by hybridizing specific DNA hairpin probe pairs to a DNA nanowire generated by RCA. The probe was labeled with FA to target human cervix carcinoma cells actively. Then the target mRNA was able to hybridize with the hairpin structure to trigger the DNA cascade hybridization, leading to instant light of the probe. Without transfection reagents, the “nano string light” facilitated the intracellular delivery and imaging of mRNA molecules. Therefore, it could be used for disease diagnostics and therapy. DNA tetrahedron has been applied for detecting-related mRNA in living cells. He et al.303 fabricated self-assembled DNA tetrahedron nanotweezers with four customized oligonucleotide strands. In the presence of the target mRNA, the nanotweezers altered its structure from the open to closed state, leading to dual fluorophores in close proximity and high FRET efficiency. The “off” to “on” signal mode provided an accurated mRNA detection without false-positive signals from complex biological matrices.

6. Conclusion and outlook

The efficient delivery of a therapeutic gene into target tissues has remained a significant barrier to realizing an effective gene-based medicine. With the rapid development of nanotechnology in the recent decade, unique gene delivery systems have become available. Liposomes are often used to deliver nucleic cargo, such as DNA or RNA, for therapeutic benefit. It has been reported that oppositely charged cationic liposomes are superior to either neutral or anionic liposomes as gene delivery carriers. However, the cationic liposomes showed dose-dependent toxicity. Due to the excellent biocompatibility, degradability, and controllable self-assembly, nucleic acid nanoassemblies with various functionalities have yielded massive potential for their application in biomedicine. Further studies can be carried out in the following areas to broaden the depth and breadth of the research on nucleic acid nanoassemblies.

Modifying the carrier surface with functional groups with long-circulating characteristics like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), which is frequently used in other drug delivery systems304, might be an effective way to improve pharmacokinetics. Some targeting ligands, such as antibodies, aptamers, and peptides, can be conjugated to the surface of nanostructure, which might be helpful for specific tissue accumulation. In addition, early exploration revealed that some of the nucleic acid nanoassemblies enter cells mainly through the endocytosis mechanism. It might not be the same case for all nucleic acid-based materials. The influence of various factors, such as the shape and surface modification of nanoassemblies on biological systems, is still unclear. Further research and exploration are required to understand their mechanism of action.