Abstract

Objectives

To measure the neonatal autopsy rate at a tertiary referral centre and identify trends over the past decade. To identify factors that may influence the likelihood of consent being given for autopsy. To examine any discordance between diagnoses before death and at autopsy.

Design

Retrospective review of patients' records.

Setting

Tertiary neonatal referral centre affiliated to university.

Outcome measures

Sex, gestational age, birth weight, type of delivery, and length of stay in neonatal unit for baby. Maternal age, marital status, history of previous pregnancies, and details of who requested permission for autopsy. Concordance between diagnoses before death and at autopsy.

Results

An autopsy was performed in 209/314 (67%) cases. New information was obtained in 50 (26%) autopsies. In six (3%) cases this information was crucial for future counselling. In 145 (74%) there was complete concordance between the clinical cause of death and the findings at autopsy. From 1994 onwards the autopsy rate in the neonatal unit fell. The only significant factor associated with consent for autopsy was increased gestational age.

Conclusions

Important extra information can be gained at neonatal autopsies. This should help parents to make an informed decision when they are asked to give permission for their baby to have an autopsy. These findings are of particular relevance in view of the recent negative publicity surrounding neonatal autopsies and the general decline in the neonatal autopsy rate over the decade studied.

What is already known on this topic

The neonatal autopsy rate dropped in Illinois during the 10 years from 1984 to 1993

Over recent years there has been a large amount of negative publicity surrounding neonatal autopsies in the United Kingdom

What this study adds

Over a quarter of neonatal autopsies yielded new information; in 3% of cases this information was crucial

This finding is likely to be of use to bereaved parents who are asked to give permission for autopsy and provides a more positive perspective on the utility of neonatal autopsies

Introduction

Autopsy has been important in medicine since the 15th century1 and has contributed greatly to clinical knowledge.2–4 Neonatal autopsy has a particularly valuable role in the counselling of families after the loss of an infant as it can help the grieving process, improve parental understanding, and alleviate concerns over prenatal events.5–9 Genetic conditions or obstetric factors of relevance to future pregnancies may also be identified.10

Recently the rate and perceived importance of autopsies of adults has declined considerably.11–14 Conversely rates of neonatal autopsy have generally remained higher, with previous reports ranging from 59% to 81%.3,10,13–17 In 2000, however, the neonatal autopsy rate declined in Illinois.18 Parental consent is thought to be the major limiting factor.16 The public's exposure to the purposes and value of the autopsy is sparse, and perceptions are often dominated by melodramatic treatment in the media.19

We measured the rate of neonatal autopsy at a tertiary referral centre over the past decade to investigate the role of various factors in determining consent for autopsy. We also examined the yield of new information in terms of discordance between diagnoses before and after death.

Methods

We carried out the study in a neonatal unit in the main tertiary neonatal referral centre for the south east of Scotland. We included records of all deaths in the neonatal unit from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 1999. The policy in the unit is that a senior clinician, normally the relevant consultant, approaches relatives for consent for autopsy after each death. Autopsies were performed only after parental consent or at the request of the procurator fiscal. Each examination was performed by one of four consultant paediatric pathologists using standard techniques.20

We recorded the cause of death from the original death certificate, which was normally completed by a consultant. We obtained maternal and infant details from the original medical records and abstracted autopsy findings from the concluding summary of the pathologist's report. Death certificates were not available for 1990-2; in these cases the cause of death was determined by a consultant neonatologist after review of the patients' records.

We used a modified version of previously published schemes11,18 to classify the concordance between autopsy findings and diagnoses before death (table 1). We compared the proportion of events in each group using the χ2 test for discrete variables and Student's t test for numerical variables.

Table 1.

Classification of concordance between diagnosis before death and at autopsy*

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| IA | Diagnosis that, had it been detected before death, would probably have led to change in management that might have resulted in cure or prolonged survival |

| IB | Diagnosis with significant implications for future genetic advice |

| II | Diagnosis that, had it been detected before death, would probably not have led to change in management or survival because: • No appropriate therapy was available at the time • Appropriate therapy was given even though the diagnosis was unknown at the time • Patient had acute cardiopulmonary arrest that was appropriately managed, but patient did not survive for definitive management • Patient had “do not resuscitate” status |

| III | Diagnosis that may or may not have been related to main disease process and was contributory cause of death |

| IV | Diagnosis unrelated to outcome and may or may not have affected eventual prognosis of patient |

| V | Complete concordance between diagnosis before death and findings at autopsy |

Modified from Kumar et al18 and Goldman et al.11

Results

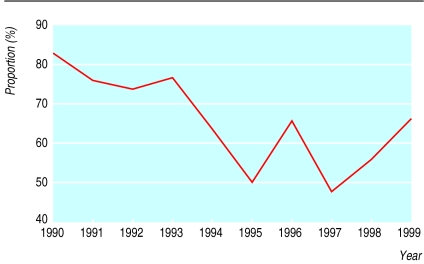

In over a quarter of cases new information was obtained at autopsy (see table A on bmj.com for further details). A single class Ia diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus was identified along with five class Ib diagnoses with implications for genetic advice—namely, Smith-Lemli-Opitz type II syndrome, De Lange's syndrome, ornithine carbamyltransferase deficiency, DiGeorge syndrome, and GM1 gangliosidosis. An autopsy was performed in 209 of the 314 cases studied (see table B on bmj.com). The overall rate of neonatal autopsy of 67% remained substantially higher than the prevailing rate in adults. From 1994 onwards, however, the annual autopsy rates dropped below levels earlier in the decade (figure). Gestational age was the only factor that was found to differ significantly between the groups who did and did not give permission for autopsy, with means of 32 and 30 weeks respectively (table 2). Details of other factors that we examined and that were not associated with consent for autopsy can be found in table C on bmj.com.

Table 2.

Factors related to baby and mother according to whether autopsy was performed

| Category | Autopsy performed

|

No autopsy

|

P value* | Data not available | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (range) | SD | Mean (range) | SD | ||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 32.2 (22-42) | 6.44 | 30.1 (23-42) | 6.79 | 0.0066 | 15 | |

| Birth weight (g) | 1828 (400-5250) | 1179 | 1669 (365-5230) | 1246 | 0.1402 | 7 | |

| Length of stay (days) | 15.4 (1-210) | 35.6 | 14.2 (1-240) | 32.3 | 0.3807 | 6 | |

| Age at death (days) | 15.8 (1-210) | 35.6 | 15.2 (1-210) | 34.8 | 0.4465 | 28 | |

| Maternal age (years) | 27.3 (15-43) | 5.81 | 28.0 (16-42) | 6.16 | 0.1923 | 51 | |

Mean of each group compared with Student's t test.

Discussion

Earlier studies have reported higher yields of new information from neonatal autopsies, ranging from 34% to 48%, though classification criteria and procedures varied between publications.10,13–15,18,21 In our study a single observer classified the level of concordance between diagnoses before death and at autopsy. Review by a multidisciplinary team, including a pathologist, may have resulted in a higher yield. We abstracted clinical diagnoses from the death certificates when they were available. The reliability of death certificates largely depends on how accurately clinicians record clinical information.22 In Edinburgh certificates were normally completed after consideration of the case by the consultant in charge.

Demographic features such as the sex of the infant and maternal age or marital status have never been identified as significant determinants of consent for neonatal autopsy.3,16,17 VanMarter et al17 and Maniscalco and Clarke3 also found gestational age to be a significant factor. Possibly clinicians are less likely to encourage parents to give consent for autopsy in extremely preterm infants.17 In general the strength of requests for individual autopsies is likely to vary because clinicians will have different views as to its importance in a specific case.

The finding that in about a quarter of cases new information was gained is likely to be of use to bereaved families when they are considering permission for an autopsy. The proportion of neonatal deaths attributed to major genetic or congenital abnormalities has increased. Accurate diagnosis in such cases, either before or after death, is highly important for future counselling. Information obtained at autopsy may not have directly affected clinical management but is essential for audit or educational purposes.21 Arguably the greatest value of the neonatal autopsy is to families during the grieving process. Such unique benefits are far more difficult to quantify.9,23

The apparent reduction in the neonatal autopsy rate in Edinburgh over the decade studied warrants serious debate. There is no obvious single explanation but possible influences include a shift in the attitude of clinicians towards autopsies or a change in the public's willingness to grant permission. Economic or procedural considerations did not feature during the period studied. The recent high profile disclosure concerning organ retention in the United Kingdom24 can only have served to harm the public's view of autopsies. A concerted effort will be needed to promote the value and purposes of the neonatal autopsy.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Autopsy rate in neonatal unit (1990-9)

Acknowledgments

We thank Gill Mitchell for her invaluable help in tracing patient records. We are grateful to Professor Neil McIntosh for his comments on the original protocol.

Footnotes

Editorial by Khong

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Three tables with further data can be found on bmj.com

References

- 1.Dorsey DB. A perspective on the autopsy. Am J Clin Pathol. 1977;69:217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landefeld CS, Chren MM, Myers A, Geller R, Robbins S, Goldman L. Diagnostic yield of the autopsy in a university hospital and a community hospital. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1249–1254. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805123181906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maniscalco WM, Clarke TA. Factors influencing neonatal autopsy rate. Am J Dis Child. 1982;136:781–784. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1982.03970450023005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berthrong M. The autopsy as a vehicle for the lifetime education of pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:506–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch CS. Talking to the family after an autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:513–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds RC. Autopsies—benefits to the family. Am J Clin Pathol. 1977;69:220–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowe J, Clyman R, Green C, Mikkelsen C, Haight J, Ataide L. Follow-up of families who experience a perinatal death. Pediatrics. 1978;62:166–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdes-Dapena M. The postautopsy conference with families. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:497–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckwith JB. The value of the pediatric postmortem examination. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1989;36:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saller DN, Jr, Lesser KB, Harrel U, Rogers BB, Oyer CE. The clinical utility of the perinatal autopsy. JAMA. 1995;273:663–665. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman L, Sayson R, Robbins S, Cohn LH, Bettmann M, Weisberg M. The value of the autopsy in three medical eras. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1000–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198304283081704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burrows S. The postmortem examination. Scientific necessity or folly? JAMA. 1975;233:441–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhar V, Perlman M, Vilela MI, Haque KN, Kirpalani H, Cutz E. Autopsy in a neonatal intensive care unit: utilization patterns and associations of clinicopathologic discordances. J Pediatr. 1998;132:75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meier PR, Manchester DK, Shikes RH, Clewell WH, Stewart M. Perinatal autopsy: its clinical value. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craft H, Brazy JE. Autopsy—high yield in neonatal population. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:1260–1262. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140260062027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khong TY, Mansor FAW, Staples AJ. Are perinatal autopsy rates satisfactory? Med J Austr. 1995;162:469–470. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb140007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VanMarter LJ, Taylor F, Epstein MF. Parental and physician-related determinants of consent for neonatal autopsy. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:149–153. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460020039023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar P, Angst DB, Taxy J, Mangurten HH. Neonatal autopsies: a 10-year experience. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown HG. Lay perceptions of autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:446–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keeling JW. The perinatal necropsy. In: Keeling JW, editor. Fetal and neonatal pathology. London: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter HJ, Keeling JW. Value of perinatal necropsy examination. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:180–184. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.2.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kircher LT. Autopsy and mortality statistics: making a difference. JAMA. 1992;267:1264–1268. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger LR. Requesting the autopsy: A pediatric perspective: psycho-social and professional aspects of the autopsy in caring for the dying child and his family. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1978;17:445–452. doi: 10.1177/000992287801700511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter M. Alder Hey report condemns doctors, management, and coroner. BMJ. 2001;322:255. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.