Abstract

Background:

Cocaine is the most commonly reported illicit stimulant used in the U.S., yet limited research has examined recent changes in cocaine use patterns and co-occurring substance use and mental health characteristics among adults using cocaine.

Methods:

Self-report data from adults (age 18 years or older) participating in the 2006 to 2019 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) were used to estimate trends in prevalence of past-year cocaine use by demographic characteristics, cocaine use disorder, cocaine injection, frequency of use. For 2018–2019, prevalence of co-occurring past-year use of other illicit and prescription substances and mental health characteristics were estimated. Multivariable logistic regression examined demographic, substance use, and mental health characteristics associated with past-year cocaine use in 2018–2019.

Results:

The annual average estimated prevalence of past-year cocaine use among adults was highest in 2006–2007 (2.51%), declined to 1.72% in 2010–2011, and then increased to 2.14% in 2018–2019. The annual average estimated prevalence of past-year cocaine use disorder was highest in 2006–2007 (0.71%) and declined to 0.37% in 2018–2019. Characteristics associated with higher adjusted odds of past-year cocaine use included: males; ages 18–49; Hispanic ethnicity; income <$20,000; large or small metro counties; use of other substances (nicotine, alcohol, marijuana, sedative/tranquilizers, prescription opioids, prescription stimulants, heroin, and methamphetamine); and serious psychological distress and suicidal ideation or attempt.

Conclusion:

Additional efforts to support prevention and response capacity in communities, expand linkages to care and retention for substance use and mental health, and enhance collaborations between public health and public safety are needed.

1. Introduction

Cocaine is a potent and addictive central nervous system stimulant and is the most commonly used illicit stimulant in the U.S. (Zimmerman, 2012; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2020). According to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA’s) 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment, cocaine is increasingly available in U.S. drug seizures, especially since 2013. Availability, coca cultivation, and cocaine production remain at elevated levels and have led to further expansion of the domestic cocaine market (Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA], 2019). In addition, DEA data indicate that illicit opioids such as illicitly manufactured fentanyl are increasingly prevalent in the cocaine supply. Since 2013, law enforcement laboratories have reported submissions of “speedball” (cocaine and heroin) and “super speedball” (cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl) mixtures to DEA’s National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS), with an increase from 18 reports from five states in 2013 to 2,695 reports from 34 states, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC in 2017 (DEA, 2019).

Coincident with the changing supply of cocaine in the U.S., cocaine-related emergency-departments (ED) visits and overdose deaths have been increasing. Evidence indicates that opioids, especially synthetic opioids such as illicitly manufactured fentanyl, have been involved in many of these ED visits and deaths, with 74.2% of cocaine-related overdose deaths involving opioids in 2018 (Cano et al., 2020). Hoots et al. (2020) found that rates of overdose deaths involving cocaine with opioids decreased 12.0% per year from 2006 to 2010, remained stable from 2010 to 2014, and increased 46.0% per year from 2014 to 2017; whereas, rates without opioids decreased 21.2% per year from 2006 to 2009, remained stable from 2009 to 2014, and increased 23.6% per year from 2014 to 2017. For ED visits, between 2006 and 2016, rates involving cocaine with opioids increased 14.7% per year whereas rates involving cocaine without opioids increased 11.3% per year from 2006 to 2012 and then remained stable from 2012 to 2016 (Hoots et al., 2020).

In 2019, over 41 million adults 18 years or older reported lifetime use of cocaine and 5.4 million reported past-year use (SAMHSA, 2020). Use of cocaine, especially long-term use, is associated with a range of negative health effects, including cardiovascular and neurological effects, increased risk of infectious disease transmission, adverse psychological and behavioral effects, and increased mortality (Butler et al., 2017; Goldstein et al., 2009; Riezzo et al., 2012). While it is well known that substance use and use disorders are associated with other mental illnesses (Compton et al., 2007; Narvaez et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2016), cocaine use, in particular, appears to exacerbate mental disorder symptoms, especially mood disorder symptoms and the presence of mental illness symptoms appears to be associated with increased cocaine use (Rounsaville, 2004). With this in mind, the recent law enforcement data indicating increasing cocaine production and availability (DEA, 2019), along with the recent data on emergency department visits (Hoots et al., 2020) and overdose deaths involving cocaine (Kariisa et al., 2019) have raised concerns about a resurgent threat of cocaine use and related harms in the U.S. in the midst of the ongoing opioid overdose epidemic.

Less is known about recent changes in cocaine use patterns. A recent study examining overall trends in cocaine use found that past-year use has been increasing in the U.S. since 2011 (Cano et al., 2020); however, this study did not examine changes in demographic trends or patterns of use among those using cocaine, limiting the ability of public health practitioners, the substance use prevention and treatment community, policy-makers, and clinicians to target prevention, treatment and response efforts. To address this research gap, this study used nationally-representative data to further examine trends underlying the recent increase in cocaine use and whether similar trends were found for cocaine use disorder, cocaine injection, and frequency of use of cocaine as well as to assess additional reported substance use and mental health problems among those using cocaine.

2. Methods

Data for this study come from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which is a nationally representative household survey of noninstitutionalized civilians 12 years of age and older administered by SAMHSA. NSDUH conducts face-to-face interviews to collect information on alcohol, drug, and tobacco use, and mental health, among other behavioral and health issues. Detailed survey methodology and analysis methods are provided on the SAMSHA website (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ], 2020). For this analysis, the public-use dataset was used and further limited to adults (≥18 years old) (SAMHSA CBHSQ, 2020).

First, to analyze trends over time, 2006 to 2019 NSDUH public-use-file data were used, aggregated into two-year intervals: 2006–2007, 2008–2009, 2010–2011, 2012–2013, 2014–2015, 2016–2017, and 2018–2019. Two-year pooled intervals were used to improve the precision of estimates particularly when stratifying by population subgroups. The unweighted sample sizes for these intervals ranged from 74,228 to 85,765 survey participants. Average annual estimated prevalences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for adults (≥18 years old) were estimated for past-year cocaine use, past-year cocaine use disorder [defined in the NSDUH survey as meeting at least one of four cocaine abuse criteria and/or three of seven cocaine dependence criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (CBHSQ, 2020)], and past-year injection of cocaine, as well as by sex, age group, and race/ethnicity. Among adults who reported past-year cocaine use, average annual prevalences were also estimated for past-year cocaine use disorder, past-year injection of cocaine, and days of cocaine use (both mean days of use and frequency of use categories, 1–29 days, 30–99 days, 100–199 days, and 200 days or more). For each outcome, t-tests for pairwise comparison between two different time points were used to test for statistically significant differences at P<0.05 between the latest year group (2018–2019) and prior year groupings (2006–2007, 2008–2009, 2010–2011, 2012–2013, 2014–2015, 2016–2017).

Second, using 2018–2019 data, among adults reporting past-year use of cocaine, we estimated past-year use of other substances (i.e., use of tobacco, marijuana, heroin, or methamphetamine; and misuse of prescribed stimulants, tranquilizers, sedatives, and opioids) and past-month binge drinking(defined as drinking ≥5 drinks for males or ≥4 drinks for females on the same occasion on ≥1 day in the past-month). We also estimated past-month nicotine dependence [based on Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale score (CBHSQ, 2020; Shiffman et al., 2004)] and other substance use disorders (i.e., alcohol, marijuana, heroin, methamphetamine, prescribed stimulants, prescribed tranquilizers, prescribed sedatives, and prescribed opioids [which are represented by prescription pain relievers in the data set as this category is composed largely of opioids (CBHSQ, 2020)]). Past-month binge drinking and past-month nicotine dependence were used as they did not have an equivalent past-year measure. In addition, we assessed past-year receipt of substance use treatment among those reporting past-year cocaine use and also among those with past-year cocaine use disorder. Third, we assessed the percentage of adults reporting past-year cocaine use that also reported past-year serious psychological distress [defined as a score of 13 or higher from the six items on the K6 Distress Scale during the “worst month” in past year (CBHSQ, 2020; Kessler et al., 2005)], major depressive episode, serious thoughts of suicide, making a suicide plan, attempting suicide, and receiving mental health treatment.

Lastly, logistic regression was performed to identify individual characteristics associated with past-year cocaine use in 2018–2019. Variables included in both bivariable and multivariable models were: sex, age, race/ethnicity, annual household income, insurance coverage type, educational attainment, residence county type [according to the 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes from the U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) (USDA Economic Research Service, n.d.)], other substance use (past-month tobacco use, past-month binge drinking, past-year use of marijuana, heroin, and methamphetamine, and past-year misuse of prescription tranquilizers/sedatives, prescription stimulants, and prescription opioids), and mental health variables (serious psychological distress, major depressive episode, suicidal ideation or attempt). Multicollinearity was assessed using correlation between predictors and variance inflation factor and was not observed in the final model. Results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals. All analyses are weighted and were conducted using the survey procedures in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) to account for the NSDUH complex survey design and sample weights (CBHSQ, 2020).

3. Results

The annual average estimated prevalence of past-year cocaine use among adults declined from 2.51% in 2006–2007 to 1.72% in 2010–2011 and then increased to 2.14% in 2018–2019 (Table 1). For past-year cocaine use disorder, the annual average estimated prevalence was highest in 2006–2007 (0.71%) and then declined to 0.37% in 2018–2019. Past-year injection of cocaine in 2018–2019 (0.05%) was lower than that in 2016–2017 (0.08%) and similar to all other years in the study.

Table 1:

Trends in Prevalence of Past-Year Cocaine Use, Use Disorders, and Frequency of Use Among Adults and By Demographic Groups, United States, 2006–2019

| 2006–2007 (N=74,228)± | 2008–2009 (N=75,211)± | 2010–2011(N=78,052)± | 2012–2013 (N=75,293)± | 2014–2015 (N=85,232)± | 2016–2017 (N=85,179)± | 2018–2019 (N=85,765)± | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Prevalence | Percent | SE | Percent | SE | Percent | SE | Percent | SE | Percent | SE | Percent | SE | Percent | SE |

| Past-Year Use | 2.51*** | 0.08 | 2.17 | 0.07 | 1.72*** | 0.06 | 1.87** | 0.07 | 1.89** | 0.06 | 2.19 | 0.06 | 2.14 | 0.06 |

| Past-Year Use Disorder | 0.71*** | 0.05 | 0.55*** | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.03 |

| Past-Year Injection | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08* | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Past-Year Use Disorder Among Those Reporting Past-Year Use | 28.37*** | 1.60 | 25.26*** | 1.38 | 20.78 | 1.61 | 21.77* | 1.52 | 18.94 | 1.22 | 17.04 | 1.20 | 17.18 | 1.15 |

| Past-Year Injection Among Those Reporting Past-Year Use | 2.53 | 0.51 | 3.48 | 0.73 | 3.55 | 0.75 | 3.86* | 0.74 | 2.72 | 0.41 | 3.28* | 0.42 | 2.02 | 0.31 |

| Mean Days of Past-Year Use | 48.70** | 3.01 | 39.92 | 2.15 | 34.64 | 2.60 | 40.96 | 2.98 | 34.79 | 1.95 | 36.98 | 2.29 | 35.48 | 2.64 |

| Prevalence by Demographic Group | ||||||||||||||

| Sex† | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 1.64 | 0.07 | 1.52 | 0.06 | 1.07*** | 0.07 | 1.09*** | 0.07 | 1.31* | 0.06 | 1.43 | 0.07 | 1.52 | 0.07 |

| Male | 3.46*** | 0.14 | 2.86 | 0.12 | 2.42* | 0.11 | 2.72 | 0.12 | 2.53* | 0.10 | 3.00 | 0.14 | 2.81 | 0.10 |

| Age Group† | ||||||||||||||

| 18–25 | 6.64*** | 0.15 | 5.61 | 0.19 | 4.68** | 0.16 | 4.70** | 0.16 | 5.08 | 0.22 | 5.71 | 0.23 | 5.53 | 0.22 |

| 26–34 | 4.14 | 0.32 | 3.78* | 0.19 | 2.93*** | 0.22 | 3.54** | 0.25 | 3.18*** | 0.19 | 4.21 | 0.19 | 4.37 | 0.18 |

| 35–49 | 2.20** | 0.15 | 1.80 | 0.14 | 1.53 | 0.14 | 1.48 | 0.13 | 1.47 | 0.10 | 1.61 | 0.13 | 1.70 | 0.11 |

| 50 or older | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.37* | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.06 |

| Race/Ethnicity† | ||||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.56** | 0.10 | 2.33 | 0.09 | 1.71*** | 0.07 | 2.00 | 0.09 | 1.89** | 0.07 | 2.28 | 0.08 | 2.20 | 0.07 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.38 | 0.27 | 1.84 | 0.18 | 1.42 | 0.18 | 1.62 | 0.20 | 2.28 | 0.23 | 1.90 | 0.20 | 1.95 | 0.25 |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.38 | 0.19 | 1.17* | 0.16 | 1.27* | 0.15 | 1.19* | 0.17 | 1.28* | 0.12 | 1.85 | 0.19 | 1.85 | 0.21 |

| Hispanic | 2.89* | 0.24 | 2.08 | 0.17 | 2.22 | 0.22 | 1.85 | 0.15 | 1.91 | 0.16 | 2.20 | 0.16 | 2.20 | 0.14 |

| Frequency of Past-Year Use | ||||||||||||||

| 1–29 Days | 65.58** | 1.75 | 67.98* | 1.55 | 71.55 | 1.61 | 68.84 | 1.70 | 70.65 | 1.52 | 72.60 | 1.47 | 73.26 | 1.45 |

| 30–99 Days | 11.03*** | 1.06 | 8.68* | 1.05 | 7.26 | 0.81 | 7.39 | 0.98 | 7.08 | 0.78 | 6.60 | 0.83 | 5.73 | 0.83 |

| 100–199 Days | 16.26 | 1.28 | 17.46 | 1.03 | 16.67 | 1.29 | 17.67 | 1.49 | 18.19 | 1.39 | 14.85 | 1.13 | 15.54 | 1.03 |

| >200 Days | 7.13 | 0.90 | 5.89 | 0.68 | 4.51 | 0.82 | 6.11 | 0.95 | 4.08 | 0.57 | 5.96 | 0.74 | 5.47 | 0.84 |

Asterisks indicate a statistically significant change in percentage between time interval indicated and 2018–19, as determined using a t-test for pairwise comparison between two different time points:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Percentage among adults reporting cocaine use in the past year

Source: National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, Public Use Data Files, 2006–2019 (SAMHSA CBH, 2020)

Unweighted Sample Size

When examining past-year cocaine use disorder among adults reporting past-year cocaine use, the prevalence was higher in 2006–2007(28.37%) compared to 2018–2019 (17.18%). The prevalence of past-year injection of cocaine among those reporting past-year cocaine use was higher in 2012–2013 (3.86%) than in 2018–2019 (2.02%). The mean number of days of cocaine use among adults reporting past-year cocaine use was 48.70 days in 2006–2007 compared to 35.48 days in 2018–2019. When examined by frequency-of-use category, the prevalence of adults reporting 1–29 days of cocaine use was higher in 2018–2019 (73.26%) compared to 2006–2007 (65.58%); the prevalence of adults reporting 30–99 days was lower in 2018–2019 (5.73%) compared to 2006–2007 (11.03%). The prevalence of those reporting more than 100–199 days or more than 200 days did not change significantly over the time period.

Prevalence of past-year cocaine use among females in 2018–2019 (1.52%) was significantly higher than the prevalence in 2010–2011 (1.07%); for males, the prevalence in 2018–2019 (2.81%) was significantly higher than the prevalence in 2010–2011 (2.42%) but lower than in 2006–2007 (3.46%) (Table 1). The prevalence among 18–25 year-olds in 2018–2019 (5.53%) was significantly higher than the prevalence in 2010–2011 (4.68%) but lower than the prevalence in 2006–2007 (6.64%). The prevalence among 26–34 year-olds in 2018–2019 (4.37%) was significantly higher than the prevalence in 2010–2011 (2.93%). The prevalence among 35–49 year-olds in 2018–2019 (1.70%) was significantly lower than the prevalence in 2006–2007 (2.20%). The prevalence among people 50 years or older in 2018–2019 (0.59%) was significantly higher than the prevalence in 2010–2011 (0.37%).

The prevalence of past-year cocaine use among non-Hispanic whites in 2018–2019 (2.20%) was significantly higher than the prevalence in 2010–2011 (1.71%) and lower than in 2006–2007 (2.56%) (Table 1). The prevalence among non-Hispanic blacks in 2018–2019 was not significantly different than any of the other time periods in the study. The prevalence among the non-Hispanic other racial/ethnic group in 2018–2019 (1.85%) was higher than the prevalence for 2008–2009 (1.17%), 2010–2011(1.27%), 2012–2013 (1.19%), 2014–2015 (1.28%). Among Hispanics of any race, the prevalence in 2018–2019 (2.20%) was lower than the prevalence in 2006–2007 (2.89%).

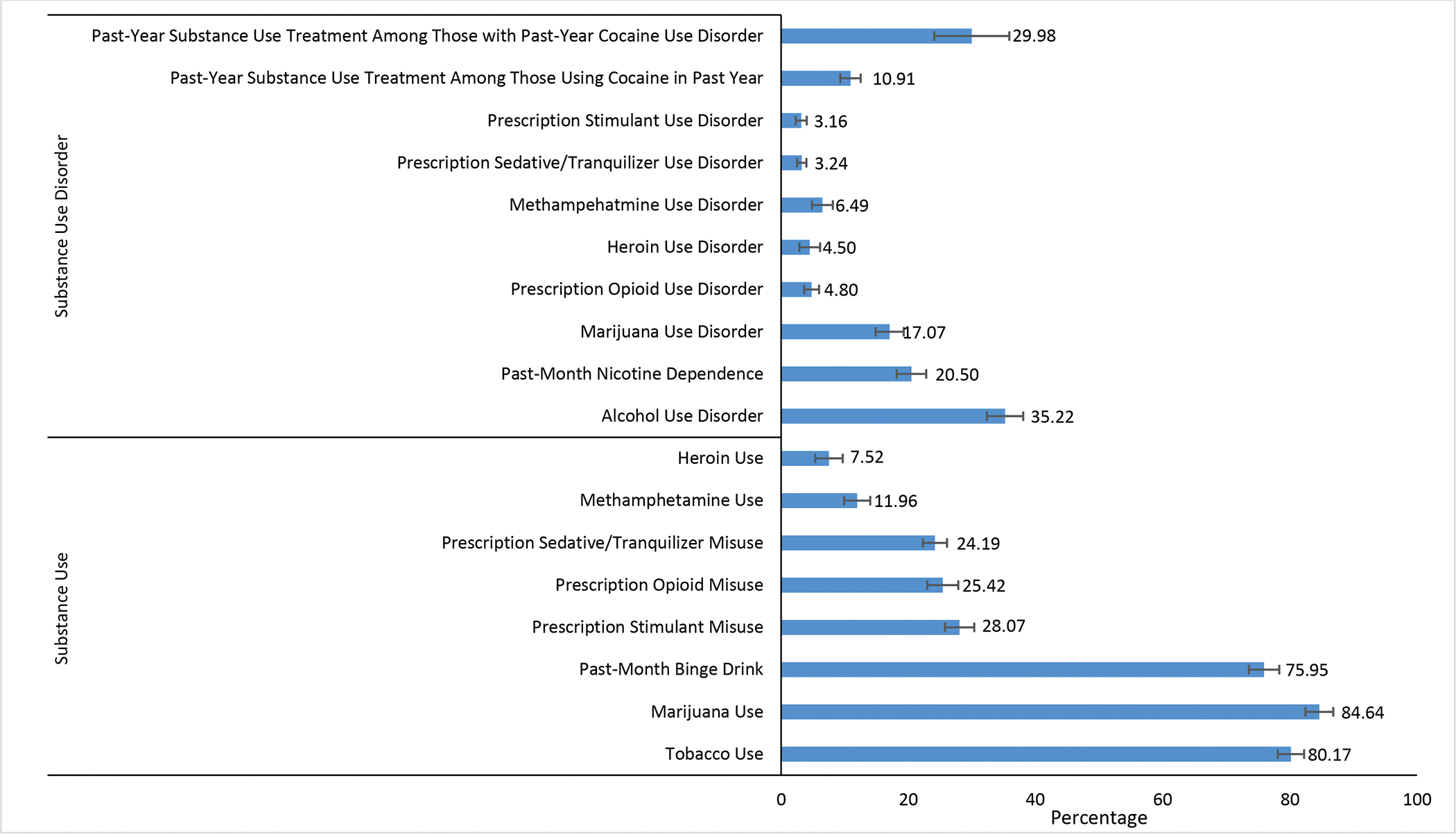

In 2018–2019, other past-year substance use among adults reporting past-year cocaine use was highest for past-year marijuana use (84.64%), past-year tobacco use (80.17%), and past-month binge drinking (75.95%) (Figure 1). Nearly thirty percent (28.07%) of adults reporting past-year cocaine use reported past-year misuse of prescription stimulants, followed by prescription opioid misuse (25.42%), prescription sedative/tranquilizer misuse (24.19%), past-year methamphetamine use (11.96%), and past-year heroin use (7.52%). For past-year substance use disorders among adults reporting past-year cocaine use, 35.22% had a past-year alcohol use disorder, 17.07% marijuana use disorder, 4.80% prescription opioid use disorder, 4.50% heroin use disorder, 6.49% methamphetamine use disorder, 3.24% prescription sedative/tranquilizer use disorder, and 3.16% prescription stimulant use disorder; 20.50% had past-month nicotine dependence. Among adults with a past-year cocaine use disorder, 29.98% reported receiving substance use treatment in the past year, and among adults reporting past-year cocaine use, 10.91% reported receiving substance use treatment in the past year.

Figure 1. Co-Occurring Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders* among Adults Reporting Past-Year Cocaine Use, United States, 2018–2019.

*All variables are past-year unless specifically stated past-month

Source: National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, Public Use Data Files, 2018–2019 (SAMHSA, CBH, 2020)

Unweighted Sample Size = 85,765

Error bars represent 95% Confidence Interval.

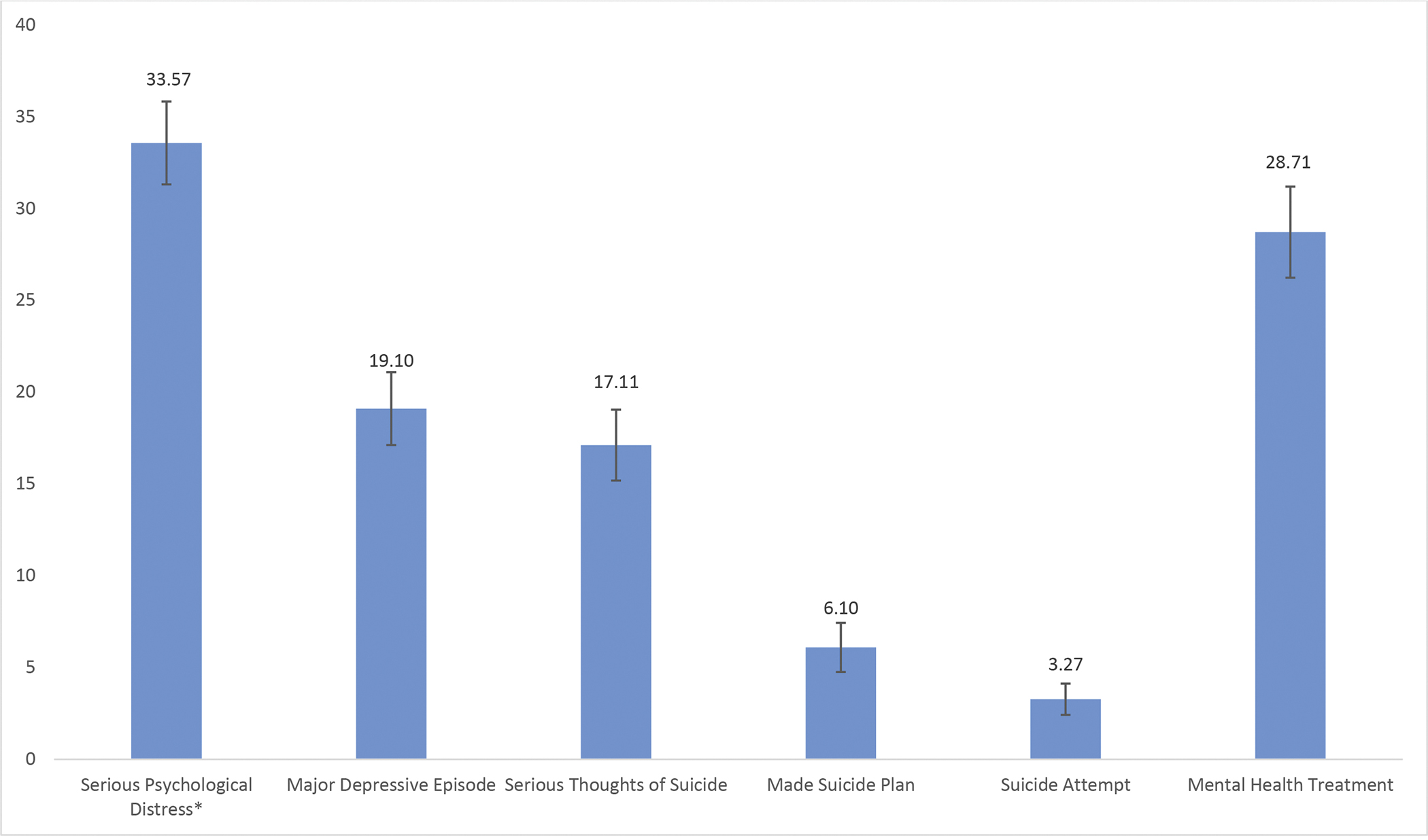

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of selected mental health indicators among adults reporting past-year cocaine use. A large minority reported having serious psychological distress (33.57%) and receiving mental health treatment in the past year (28.71%). Past-year major depressive episode was reported by 19.10% of adults reporting past-year cocaine use; having serious thoughts of suicide in the past year was reported by 17.11%, 6.10% made a suicide plan in the past year, and 3.27% reported attempting suicide in the past year.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Past-Year Mental Health Characteristics Among Adults Reporting Past-Year Cocaine Use, United States, 2018–2019.

Source: National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, Public Use Data Files, 2018–2019 (SAMHSA, CBH, 2020)

Unweighted Sample Size =85,765

Error bars represent 95% Confidence Interval

*Serious psychological distress is defined as a score of 13 or higher from the six items on the K6 Distress Scale (for worst month in past year). (CBHSQ, 2020; Kessler et al., 2005).

Table 2 shows the results of the bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models. In the multivariable model, characteristics associated with higher adjusted odds for past-year cocaine use included: males (aOR=1.37, 95% CI:1.20–1.56) compared to females; age 18–25 years (aOR=1.97, 95% CI: 1.56–2.49) and age 26–34 years (aOR=1.84, 95% CI: 1.40–2.40) compared to people 50 years or older; Hispanics (aOR=1.29, 95% CI: 1.11–1.51) compared to Non-Hispanic whites. Living in a large metro (aOR=1.65, 95% CI: 1.33–2.06) or small metro (aOR=1.34, 95% CI: 1.08–1.67) compared to a non-metro county was also associated with higher odds of past-year cocaine use. Substance use and abuse patterns associated with higher odds of past-year cocaine use include past-month tobacco use (aOR=2.82, 95% CI: 2.45–3.23); past-month binge drinking (aOR=3.74, 95% CI:3.15–4.44); past-year marijuana use (aOR=7.90, 95% CI: 6.52–9.57); past-year prescription sedative/tranquilizer misuse (aOR=2.49, 95% CI: 2.01–3.08); past-year prescription stimulant misuse (aOR=4.17, 95% CI:3.50–4.96); past-year prescription opioid misuse (aOR=1.70, 95% CI:1.36–2.13); past-year heroin use (aOR=8.60, 95% CI: 3.82–19.36); and past-year methamphetamine use (aOR=4.04, 95% CI: 2.65–6.16). Mental health characteristics associated with past-year cocaine use included past-year serious psychological distress (aOR=1.21, 95% CI: 1.01–1.45) and suicidal ideation or attempt (aOR=1.31, 95% CI: 1.03–1.66).

Table 2.

Characteristics Associated with Past-Year Cocaine Use among Adults, U.S., 2018–2019†

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | Ref | Ref |

| Male | 1.87 (1.66,2.11) | 1.37 (1.20,1.56) |

| Age Group | ||

| 18–25 | 9.89 (7.78,12.58) | 1.97 (1.56,2.49) |

| 26–34 | 7.66 (6.07,9.68) | 1.84 (1.40,2.40) |

| 35–49 | 2.90 (2.34,3.60) | 1.22 (0.98,1.52) |

| 50 or older | Ref | Ref |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.89 (0.67,1.17) | 1.01 (0.75,1.36) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 0.85 (0.66,1.08) | 1.10 (0.89,1.36) |

| Hispanic | 1.01 (0.88,1.17) | 1.29 (1.11,1.51) |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 1.87 (1.56,2.24) | 1.25 (1.00,1.56) |

| $20,000-$49,999 | 1.28 (1.11,1.48) | 1.11 (0.94,1.33) |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 1.13 (0.91,1.40) | 1.09 (0.83,1.42) |

| $75,000 or more | Ref | Ref |

| Insurance Status | ||

| Private or other insurance | Ref | Ref |

| Medicaid-only | 2.00(1.68,2.38) | 1.02 (0.83,1.25) |

| Uninsured | 2.13 (1.80,2.52) | 1.09 (0.89,1.34) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | Ref | Ref |

| High school graduate | 1.12 (0.90,1.38) | 0.88 (0.67,1.17) |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 1.41 (1.11,1.80) | 1.02 (0.75,1.39) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 1.02 (0.80,1.32) | 1.27 (0.93,1.73) |

| County Type ± | ||

| Large metro | 1.76 (1.42,2.18) | 1.65 (1.33,2.06) |

| Small metro | 1.48 (1.20,1.83) | 1.34 (1.08,1.67) |

| Non-metro | Ref | Ref |

| Substance Use † | ||

| Past-Month Tobacco Use | 10.73 (9.42,12.22) | 2.82 (2.45,3.23) |

| Past-Month Binge Drink | 9.45 (8.25,10.83) | 3.74 (3.15,4.44) |

| Past-Year Marijuana Use | 29.64 (24.88,35.32) | 7.90 (6.52,9.57) |

| Past-Year Prescription Sedative/Tranquilizer Misuse | 17.03 (15.17,19.12) | 2.49 (2.01,3.08) |

| Past-Year Prescription Stimulant Misuse | 30.22 (26.71,34.18) | 4.17 (3.50,4.96) |

| Past-Year Prescription Opioid Misuse | 10.25 (8.93,11.77) | 1.70 (1.36,2.13) |

| Past-Year Heroin Use | 52.63 (35.16,78.78) | 8.60 (3.82,19.36) |

| Past-Year Methamphetamine Use | 25.65 (20.64,31.87) | 4.04 (2.65,6.16) |

| Mental Health | ||

| Past-Year Serious Psychological Distress* | 3.91 (3.50,4.37) | 1.21 (1.01,1.45) |

| Past-Year Major Depressive Episode | 3.07 (2.68,3.51) | 0.86 (0.68,1.09) |

| Past-Year Suicidal Ideation or Attempt | 4.57 (3.97,5.27) | 1.31 (1.03,1.66) |

Reference group is no use (misuse) in past-month or past-year; Bold text indicates statistically significant results; aOR=adjusted odds ratio, adjusted for all variables included in model; unadjusted odds ratios are provided for comparison.

Based on the 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes from the U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA Economic Research Service, n.d.)

Serious psychological distress is defined as a score of 13 or higher from the six items on the K6 Distress Scale, used by NSDUH for worst month in past year (CBHSQ, 2020; Kessler et al., 2005).

Source: National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, 2018–2019 (SAMHSA CBH, 2020)

Unweighted Sample Size =85,765

4. Discussion

In the United States, while the prevalence remains lower than in 2006–2007, past-year cocaine use among adults has been increasing since 2012–2013; however, this increase appears to be driven by adults who are using cocaine infrequently, or less than 30 days in the past year. Importantly, we did not find an increase in the prevalence of past-year cocaine use disorder or past-year cocaine injection. In fact, both the prevalence of past-year cocaine use disorder among all adults as well as among adults reporting past-year cocaine use declined approximately 40% in 2018–2019 compared to 2006–2007. Other studies have shown that, despite increases in cocaine-involved overdose deaths during the same time frame, most of the increase in these deaths is driven by overdoses that involve both opioids and cocaine (Jones et al., 2017; Gladden et al., 2019; Kariisa et al., 2019; Hoots et al., 2020; O’Donnell et al., 2020), linking cocaine-related harms to the ongoing opioid crisis. O’Donnell et al. (2020) highlighted illicitly manufactured fentanyl found in overdose deaths in combination with cocaine to be more prevalent than deaths involving cocaine alone. Given this information, interventions related to the distribution and use of naloxone are critical for people who use cocaine (O’Donnell et al., 2020). Strengthening public health and public safety partnerships can improve detection and response to emerging overdose trends related to cocaine and illicitly manufactured fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, leading to better targeted interventions, such as community education or increasing distribution of naloxone.

Other concerning findings in our study included high rates of past year use of other substances (up to 84.64%) and past year substance use disorders (up to 35.22%), as well as psychological distress, depression, and suicidal ideation among adults using cocaine. Together with the fact that only 29.98% of adults with a cocaine use disorder received substance use treatment in the past year, these findings point to the need for more comprehensive prevention, treatment, and response strategies that address rising cocaine availability and harms in conjunction with efforts to combat the opioid overdose epidemic.

Our findings provide new insights into populations to prioritize for prevention, treatment, and response efforts. For example, adults 18–25 years of age and 26–34 years of age are primarily driving the increases in cocaine use seen in this study, and it is possible that some of the increase in use is related to initiation among these younger aged adults. In support of this idea, the 2019 NSDUH report finds that adults 18–25 years of age make up the largest proportion of those reporting past year initiation of cocaine use (SAMHSA, 2020). It is also possible, given the high rates of past-year use of other substances noted in our study, that these adults are adding cocaine to the other substances they more routinely use and so their use of cocaine is infrequent. In either case, these younger age groups present an important opportunity for targeted strategies to discontinue early use and early interventions to prevent subsequent development of a use disorder, in both college and non-college settings. While research is limited, prevention strategies include screening and brief interventions in school or healthcare settings, skills training, and individually tailored, electronically delivered interventions (Stockings et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2017). Treatment options for cocaine-use disorder are largely psychosocial, as there are no approved pharmaceutical interventions for treatment, as there are for opioid use disorder (Kampman, 2019).

Other demographic groups of interest for targeting interventions include males and those living in large or small metropolitan areas. Individuals reporting Hispanic ethnicity had statistically significantly higher adjusted odds of reporting past year cocaine use as well, although it should be noted that the prevalence of use for this group was lower in 2018–2019 than in 2006–2007. Methamphetamine, the other primary illicit stimulant used in the U.S. that has also seen increases in availability, use, and overdose deaths in recent years (DEA, 2019; Gladden et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2020b; Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2020; O’Donnell et al., 2020), has somewhat different risk factors. As with cocaine, higher odds of methamphetamine use are seen among males and adults using other substances. However, unlike cocaine, methamphetamine use was more likely to be reported by adults in older age groups, those who lived in nonmetro counties, and who had less than a bachelor’s degree; methamphetamine use was substantially less likely to be reported by non-Hispanic blacks (Jones et al., 2020a). These differences point to the need to account for differences in the local illicit drug supply and substance use patterns in communities when tailoring prevention and response strategies.

High rates of past year use of other substances, substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders are noteworthy, particularly past year use of tobacco (80.17%), marijuana (84.64%) and past month binge alcohol consumption (75.95%). Such overlap with other substances and with non-substance psychiatric disorders is typical for illicit drug use which often overlap with other behavioral health issues (Compton et al., 2007; Narvaez et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2016). Because of the cross-sectional nature of the data in our study, it is not clear whether the other substance use and psychiatric symptoms may have contributed to the onset of cocaine use or whether cocaine use may have exacerbated these other conditions. In either case, the practical implication is that persons who are identified as using cocaine should be carefully assessed for other substance use and psychiatric disorders and referred to appropriate evidence-based mental health and substance use treatment services. This can include both questioning patients about their use of substances as well as testing for substance use (e.g. urine, saliva, or serum tests) (Dolan et al., 2004; McNeely et al., 2016). The association with suicidal thoughts and behaviors also suggests the importance of assessment of suicide risk in patients identified as using cocaine (Park & Zarate, 2019). Suicide prevention strategies, such as better social and financial support systems, might also be pursued in addition to mental health treatment (Stone et al., 2017).

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, NSDUH data are self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability biases. Second, because the survey is cross-sectional and different persons were sampled each year, inferring causality from the observed associations between the predictors examined and self-reported past-year cocaine use is not possible. Third, NSDUH does not include homeless persons not living in shelters, active duty military, or persons residing in institutions such as those who are incarcerated; thus, substance use estimates in this study might not be generalizable to the total U.S. population. Finally, NSDUH provides estimates of persons meeting diagnostic criteria for cocaine and other substance use disorders based on self-reported responses to the individual questions that make up the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder, not estimates of the number of persons receiving a diagnosis from a health care provider.

Conclusions

Although adult use of cocaine in the U.S. has increased in the past decade, the frequency of use and the prevalence of cocaine use disorder have decreased. These trends and patterns should be continuously monitored to inform ongoing prevention efforts. Association with past year suicidal thoughts and behaviors suggests a particular need for both substance-related and mental health-related services for persons who use cocaine, in addition to broader suicide prevention strategies. Given rising availability of cocaine, cocaine use, and harms associated with cocaine use such as overdose deaths, additional efforts to support prevention and response capacity in communities, expand linkages to care and retention for substance use and mental health, and enhance collaborations between public health and public safety are needed.

Footnotes

Declarations of Competing Interests: Dr. Compton reports long-term holdings in General Electric Company, 3M Companies and Pfizer, Incorporated, unrelated to the present work.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- Butler AJ, Rehm J, & Fischer B (2017). Health outcomes associated with crack-cocaine use: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Drug and Alcohol Depend, 180, 401–416. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano M, Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, & Vaughn MG (2020). Cocaine use and overdose mortality in the United States: Evidence from two national data sources, 2002–2018. Drug and Alcohol Depend, 214, 108148. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2020). 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Public Use File Codebook. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. Retrieved from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/. Accessed 8/16/2020. [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2007). Prevalence, Correlates, Disability, and Comorbidity of DSM-IV Drug Abuse and Dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. of Gen. Psychiatry, 64(5), 566. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Smith D, & Briley D (2017). Substance use prevention and treatment outcomes for emerging adults in non-college settings: A meta-analysis. Psychol. of Addict. Behav.: J. of the Society of Psychol. in Addict. Behav, 31(3), 242–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration. (2019). 2019 Drug Enforcement Administration National Drug Threat Assessment. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/2019-NDTA-final-01-14-2020_Low_Web-DIR-007-20_2019.pdf. Accessed 8/16/2020.

- Dolan K, Rouen D, & Kimber J (2004). An overview of the use of urine, hair, sweat and saliva to detect drug use. Drug and Alcohol Rev, 23(2), 213–217. 10.1080/09595230410001704208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden RM, O’Donnell J, Mattson CL, & Seth P (2019). Changes in Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths by Opioid Type and Presence of Benzodiazepines, Cocaine, and Methamphetamine—25 States, July–December 2017 to January–June 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep, 68(34), 737–744. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6834a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RA, DesLauriers C, Burda A, & Johnson-Arbor K (2009). Cocaine: History, social implications, and toxicity: a review. Semin. in Diagn. Pathol, 26(1), 10–17. 10.1053/j.semdp.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Smith SM, Pickering RP, Huang B, & Hasin DS (2016). Epidemiology of DSM-5 Drug Use Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(1), 39. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoots B, Vivolo-Kantor A, & Seth P (2020). The rise in non-fatal and fatal overdoses involving stimulants with and without opioids in the United States. Addict, 115(5), 946–958. 10.1111/add.14878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, Baldwin GT, & Compton WM (2017). Recent Increases in Cocaine-Related Overdose Deaths and the Role of Opioids. Am. J. of Public Health, 107(3), 430–432. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Compton WM, & Mustaquim D (2020a). Patterns and Characteristics of Methamphetamine Use Among Adults—United States, 2015–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep, 69(12), 317–323. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Olsen EO, O’Donnell J, & Mustaquim D (2020b). Resurgent Methamphetamine Use at Treatment Admission in the United States, 2008–2017. Am. J. of Public Health, 110(4), 509–516. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman KM (2019). The treatment of cocaine use disorder. Sci. Adv., 5(10), eaax1532. 10.1126/sciadv.aax1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariisa M, Scholl L, Wilson N, Seth P, & Hoots B (2019). Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Cocaine and Psychostimulants with Abuse Potential—United States, 2003–2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep, 68(17), 388–395. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6817a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, & Walters EE (2005). Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. of Gen. Psychiatry, 62(6), 617. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely J, Wu L-T, Subramaniam G, Sharma G, Cathers LA, Svikis D, Sleiter L, Russell L, Nordeck C, Sharma A, O’Grady KE, Bouk LB, Cushing C, King J, Wahle A, & Schwartz RP (2016). Performance of the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS) Tool for Substance Use Screening in Primary Care Patients. Annals of Intern. Med., 165(10), 690. 10.7326/M16-0317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez JCM, Jansen K, Pinheiro RT, Kapczinski F, Silva RA, Pechansky F, & Magalhães PV (2014). Psychiatric and substance-use comorbidities associated with lifetime crack cocaine use in young adults in the general population. Compr. Psychiatry, 55(6), 1369–1376. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, Mattson CL, Hunter CT, Davis NL. Vital Signs: Characteristics of Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids and Stimulants — 24 States and the District of Columbia, January–June 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:1189–1197. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park LT, & Zarate CA (2019). Depression in the Primary Care Setting. N. Engl. J. of Med, 380(6), 559–568. 10.1056/NEJMcp1712493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riezzo I, Fiore C, De Carlo D, Pascale N, Neri M, Turillazzi E, & Fineschi V (2012). Side Effects of Cocaine Abuse: Multiorgan Toxicity and Pathological Consequences. Curr. Medicinal Chem, 19(33), 5624–5646. 10.2174/092986712803988893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ (2004). Treatment of cocaine dependence and depression. Biological Psychiatry, 56(10), 803–809. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters A, Hickcox M The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence, Nicotine & Tob. Res, Volume 6, Issue 2, April 2004, Pages 327–348, 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockings E, Hall W, Lynskey M, Morley K, Reavley N, Strang J, Patton G and Degenhardt L, 2016. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), pp.280–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DM, Holland KM, Bartholow B, Crosby AE, Davis S, and Wilkins N (2017). Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policies, Programs, and Practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2020). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2002–2019 (NSDUH-2002–2019-DS0001). Retrieved from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/. Accessed 5/1/2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20–07-01–001, NSDUH Series H-55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ Accessed 2/11/2020. [Google Scholar]

- USDA ERS - Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. (n.d.). Retrieved February 16, 2021, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx

- Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hoots BE, Seth P, & Jones CM (2020). Recent trends and associated factors of amphetamine-type stimulant overdoses in emergency departments. Drug and Alcohol Dep, 216, 108323. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman JL (2012). Cocaine Intoxication. Crit. Care Clin, 28(4), 517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]