Abstract

Background

Before 1991, the infectious diseases surveillance systems (IDSS) of the former Soviet Union (FSU) were centrally planned in Moscow. The dissolution of the FSU resulted in economic stresses on public health infrastructure. At the request of seven FSU Ministries of Health, we performed assessments of the IDSS designed to guide reform. The assessment of the Armenian infectious diseases surveillance system (AIDSS) is presented here as a prototype.

Discussion

We performed qualitative assessments using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for evaluating surveillance systems. Until 1996, the AIDSS collected aggregate and case-based data on 64 infectious diseases. It collected information on diseases of low pathogenicity (e.g., pediculosis) and those with no public health intervention (e.g., infectious mononucleosis). The specificity was poor because of the lack of case definitions. Most cases were investigated using a lengthy, non-disease-specific case-report form Armenian public health officials analyzed data descriptively and reported data upward from the local to national level, with little feedback. Information was not shared across vertical programs. Reform should focus on enhancing usefulness, efficiency, and effectiveness by reducing the quantity of data collected and revising reporting procedures and information types; improving the quality, analyses, and use of data at different levels; reducing system operations costs; and improving communications to reporting sources. These recommendations are generalizable to other FSU republics.

Summary

The AIDSS was complex and sensitive, yet costly and inefficient. The flexibility, representativeness, and timeliness were good because of a comprehensive health-care system and compulsory reporting. Some data were questionable and some had no utility.

Background

Health information systems (HIS) provide a scientific and technological framework to gather, manage, and interpret data to inform the public, policymakers, administrators, and health-care workers about the distribution and determinants of health conditions. Further, they can (and should) guide and measure the impact of interventions [1]. Public health surveillance – a subset of HIS – has been defined as the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of outcome-specific data for use in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice[2]. Public health surveillance can be used to 1) assess the overall health status of a population, 2) describe the natural history of disease, 3) monitor disease trends, 4) detect epidemics, 5) evaluate the effect of prevention and control measures, 6) generate hypotheses, and 7) facilitate epidemiologic and laboratory research [3].

Before 1991, the Soviet Union centrally planned the infectious diseases surveillance systems (IDSS) of its 15 republics. Approximately 300 million persons were covered under the IDSS. Central monetary and technical support for the IDSS ended in 1991. As a result, the republics have struggled to maintain their respective IDSS. The former Soviet Union (FSU)-wide diphtheria outbreak in the 1990s [4] and the re-emergence of malaria in Tadjikistan in 1991 [5] and in Armenia [6] and Azerbaijan [7] in 1994 indicated that financial constraints resulting in the disruption of public health infrastructure and services had increased the risk of the re-emergence of infectious diseases [8].

After 1991, this transition to nationalism, privatization, and social reorganization posed new challenges to each republic of the FSU. The loss of centralized training, public health expertise, and resources especially impacted the surveillance systems in each republic. [9] Further, privatization of the FSU medical systems resulted in under-budgeted public health services and inadequately paid personnel [10]. Combined with these infrastructure problems, the increased population migration – both within the FSU and internationally – contributed to morbidity and mortality through population dislocation [8]. This has increased the risk of exposure to re-emerging microbial and environmental pathogens and limited access to health services and good nutrition [9,10].

The most important of these changes was the financial crises resulting from the severance of economic ties among all republics of the FSU. Public health officials were challenged to transform the bulky, state-sponsored IDSS. With high inflation and unemployment, they also suffered from shortages of vaccines, hospital supplies, and essential drugs. Provision of basic public health services were compromised, including repairing antiquated water and sewer systems, resulting in increased risk for gastroenteritis and infections with hepatitis A [11]; the largest documented outbreak of typhoid in this century occurred in Tajikistan in February 1997 [12]. Practices such as reusing syringes during vaccination and poor sterilization procedures during dentistry have contributed to nosocomial outbreaks of HIV and a high prevalence of infections with hepatitis B [13].

The objective of this work was to assess the current status and functioning of various IDSS, so as to guide reform efforts. At the invitation of seven Ministries of Health (MoHs), we performed assessments in the Russian Federation and in the Republics of Kazakhstan, Tadjikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Armenia, and in the Kyrgyz Republic. We found striking homogeneity in comparing the IDSS from one republic to another; and, for clarity, we present here representative findings by using the Armenian component of the IDSS (AIDSS) as a prototype.

Discussion

We used the CDC guidelines to assess the seven IDSS [14]; these guidelines have recently been republished in revised form [15]. This strategy includes an assessment of public health importance, objectives and usefulness, operation of the system, cost, and the seven system attributes (i.e., simplicity, flexibility, acceptability, sensitivity, predictive value positive, representativeness, and timeliness). The assessment involves gathering both qualitative (i.e., simplicity, flexibility, and acceptability) and observations of the quantitative (i.e., sensitivity, predictive value positive, representativeness, and timeliness) attributes.

In Armenia, we attempted to gather as much information as possible with respect to the construct and utility of the AIDSS from those most integral to its functioning and application. Therefore, we conducted face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions with approximately 50 epidemiologists at the Ministry of Health, the National Sanitary Epidemiologic Service, the Institute of Epidemiology, and two regional, three districts, and one city Sanitary Epidemiologic Service (SES) office. We also interviewed 23 health-care workers at village health centers, polyclinics, hospitals, and laboratories, which serve as the primary reporting units for the AIDSS.

At the time of this assessment, the AIDSS was moving toward reform, and we chose not to use the limited resources to gather quantitative data (e.g., through chart reviews) to assess the quantitative attributes of the AIDSS (i.e., sensitivity, predictive value positive, representativeness, and timeliness). Rather, we relied on qualitative observations gleaned in the course of the interviews. We present here the qualitative observations made of the AIDSS and recommendations for reform. We believe these observations and recommendations reflect the status of the IDSS of the other FSU republics.

Description of the AIDSS

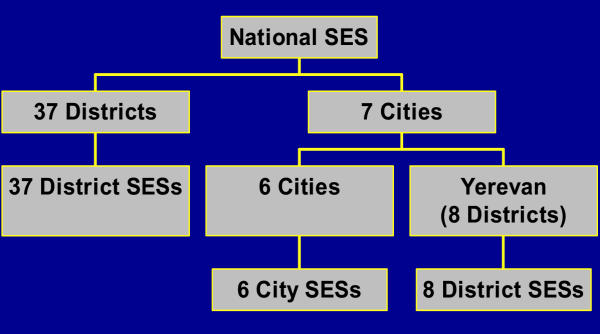

A republic of 3.3 million, Armenia gained its independence from the FSU on September 21, 1991 (Figure 1). The country is divided into 11 regions, which are subdivided into 37 districts (Figure 2). Responsibility for the AIDSS rests with the Department of Hygiene and Epidemiologic Surveillance – a department of the Armenian MoH (AMoH) – composed of 52 functional units known as the Sanitary Epidemiologic Service (SES). The units or stations of the SES parallel the geopolitical divisions of Armenia. There exists one SES station in each district. Each city has one SES station, except Yerevan, the capital. Yerevan has eight districts, each with one SES station. The national SES is also located in Yerevan.

Figure 1.

The Caucasus region of the New Independent States (NIS)

Figure 2.

The Sanitary Epidemiologic Stations (SES)

The SES, per se, developed from a model created in the late 1800s in russia and uniformly developed over many years in the republics of the FSU. Its principle functions are to collect and analyze public health surveillance data and to implement and enforce strategies for the prevention and control of infectious diseases. Traditionally, the SES had approximately 10% of the entire medical person-power and budget of the AMoH, and was separate from the curative medical care system [16,17]. The SES was staffed by epidemiologists (physicians), microbiologists, sanitary hygienists, and other health workers (paramedics and physician assistants). The district SES was the basic public health unit that monitored infectious diseases, investigated outbreaks, attended to child and adolescent health, inspected the food-service industry, monitored water purity, and dealt with occupational and environmental health problems throughout Armenia [6]. City-, regional-, and national-level SES administrations were larger, with specialized staff.

The SES collected infectious diseases data from all health-care facilities throughout the country. Before 1991, Armenia had a comprehensive and free health-care delivery system accessible to all citizens with health facilities and health-care workers employed under the auspices of the AMoH. Outpatient facilities (village health centers and polyclinics) and hospitals reported to the AIDSS. Each district had 12–45 village health centers, two polyclinics, and one hospital. The seven cities in Armenia had variable numbers of polyclinics and hospitals.

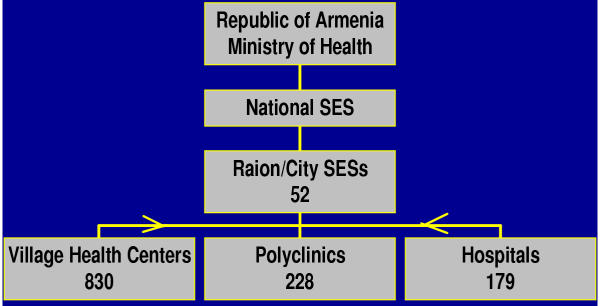

Altogether, Armenia had 830 village health centers, 228 polyclinics, and 179 hospitals (Figure 3). Data from these health facilities were reported to the 52 districts and city SES and then to the national SES, which forwarded aggregated data to the Department of Hygiene and Epidemiologic Surveillance in the AMoH.

Figure 3.

The flow of information, infectious diseases surveillance system, Republic of Armenia, 1996

Objectives and Data Collection, Reporting, Analyses, and Response

The objectives of the AIDSS were to identify cases of infectious diseases, document outbreaks, and monitor trends in disease occurrence. It collected aggregated and case-based data on new cases of 64 infectious diseases. This list included some diseases with low pathogenicity (e.g., pediculosis and scabies) and some diseases with inadequate or non-existent preventive measures (e.g., infectious mononucleosis and parapertussis). There existed no tiered (e.g., confirmed, probable, and suspected) standardized case definitions. The reporting of confirmed or suspected cases of some infectious diseases required immediate reporting via telephone or in person within 12–24 hours. These included epidemic prone diseases (e.g., diphtheria, polio, plague).

Data were provided monthly and yearly from the district to national SES. Reports from the national SES were sent monthly to the AMoH and the other 14 republics of the FSU and back to the district SES twice a year. The district and city SES reported immediately to the national SES.

At all levels, epidemiologists used descriptive statistics for data analyses. These included the calculation of aggregated case numbers and incidence and prevalence rates based on estimates of the population size provided by the state agency charged with gathering census data; limited stratification by person, time, and place; and the assessment of trends. Epidemiologists did not use analytic methods to assess risk factors for diseases, even though they were collected.

Cases and contacts of every disease were investigated by a district or city SES epidemiologist within 24 hours of the receipt of the case report, using a standardized form known as the epid carta. This form was not disease specific, yet lengthy (46 questions, many of which required subjective responses). Little or no feedback was provided to the original reporting sources and no routine or formal sharing of data and information occurred between the district SES and health-care facilities. Table 1 summarizes the public health practice activities in Armenia, stratified by health facility.

Table 1.

Public health surveillance and action core and support activities, by health level, Republic of Armenia, 1996

| Organization Level | Public Health Surveillance and Action Core and Support Activity | ||||||||||

| Detection | Registration | Confirmation (Epidemiologic and Laboratory) | Reporting/ Feedback | Analyses | Acute (Outbreak-Type) Response | Planned (Management-Type) Response | Communication | Training | Supervision | Resource-Provision | |

| Primary Health Facilities | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| District SES | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| District Lab | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| District Lab | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Regional SES | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Regional Lab | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| National SES | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| National Lab | X | X | X | X | |||||||

Qualitative Attributes

Simplicity

Referring to both its structure and ease of operation, the AIDSS was complex. Epidemiologists gathered voluminous information on each case; parallel vertical public health programs reported duplicative information; much time was required to collect, register, and report case information; and many staff maintained the system.

Flexibility and Acceptability

Addressing the extent to which the AIDSS could adapt to changing information needs or operating conditions and reflecting the willingness of participants to provide information and monitor the system, the AMoH, itself, determined both its flexibility and acceptability. Because the AMoH provided salaries for health-care personnel, it could enforce compulsory reporting, through monetary fines and professional demotions. Changes in reportable conditions or criteria were made rapidly because administrative SES employees carried out orders quickly and completely at all levels in the system.

Quantitative Attributes

While we did not quantitatively measure the attributes of sensitivity, predictive value positive, representativeness, and timeliness, we did make qualitative observations.

Sensitivity

Assessing the AIDSS's ability to account for all incidents of a disease (i.e., the proportion of cases detected, correctly diagnosed, and reported), we learned that detection of most reportable infectious conditions did come to medical attention. This was enhanced because all citizens received free health care and because primary care physicians were responsible for care (including community outreach) of persons in their assigned territories. However, due to constrained resources, laboratory confirmation of reportable infectious diseases was limited in practice. As such, reporting was based on clinical or epidemiologic, rather than laboratory information.

Predictive Value Positive

The likelihood that a disease report constituted a true case of that disease was diminished because of the lack of laboratory confirmation and standardized case definitions.

Representativeness

We felt that, ideally, the AIDSS accurately described the distribution of diseases in the population by person, time, and place because disease reporting was mandatory and failure to report was a punishable offense. And, because of the penalties, all official reporting to the national level did occur on a monthly basis. However, it was common practice for epidemiologists to conceal cases of infectious disease and willfully underreport epidemic morbidity, because outbreaks meant that the epidemiologists were not performing their duties of preventing and controlling infectious diseases. This paradox resulted in epidemiologists managing two sets of information: one officially reported to higher-ups and one unofficially kept (with more accurate numerators).

Timeliness

Information for action or for long-term planning was available because mandatory reporting to the SES within 12–24 hours of diagnosis for most conditions under surveillance allowed rapid implementation of control and prevention measures.

Costs

Because budgets were relatively non-existent in the FSU, historical data on the costs of operating the AIDSS were not available. In the FSU centrally planned economy, resources were obtained from cost centers (e.g., utilities were not metered, office supplies were requested by quantity and not cost, and salaries were provided from the central budget). However, numerous observations led us to conclude that the AIDSS was relatively inefficient and costly; in large part, because the expenditure was paid from the public sector.

The AIDSS was labor intensive. Being paper-driven, reporting dieases for which no practical public health interventions exist misallocated scarce resources. Other common public health activities with high opportunity cost in the AIDSS were indiscriminate disinfection of homes and work sites. Environmental background monitoring practices by district and regional SES included routine collection of specimens and laboratory testing (e.g., air and water samples, food products, and items that children may come in contact with such as toys or eating utensils) in addition to evaluation of physical factors (noise, vibration, microclimate, electromagnetic fields, levels of lighting, and ionic radiation) at several sites (e.g., work places and day-care centers).

When cases of hepatitis A, acute gastroenteritis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, or pediculosis were reported, disinfection of homes, schools, day-care centers and work places was conducted by public health workers who used chloramine application and steam cleaning of all hard surfaces and laundering of all clothing and bedding materials. The effectiveness of such disinfection practices or environmental background monitoring has not been documented, and is likely of doubtful public health utility.

During disease outbreaks, it was common practice to investigate every case and culture all available materials, and decontamination efforts were instituted regardless of epidemiologic evidence. It was common practice to hospitalize children < 1 year of age with pneumonia for 7–14 days, and children of all ages with acute gastroenteritis for 7–15 days. It was also common to hospitalize both adults and children with hepatitis A for 21 days, with syphilis for two weeks, with gonorrhea for three weeks, and with tuberculosis for one year. These isolation practices, meant to prevent disease transmission to the community, were consequences of central planning in which emphasis was placed on input indicators such as the occupancy rates of hospitals. Incentives (budget allocations) placed on input rather than output measures led to a level of medical infrastructure that has been difficult to maintain given current levels of funding available for the health sector.

Because financial issues were a major driving factor, cost analyses of surveillance practices and control measures could identify areas for cost-savings. Analyses of the surveillance system in Ukraine (using 1996 budget figures) revealed that excessive culturing represented 47% of the cost per capita expenditure of the L'viv Regional SES and disinfection procedures accounted for almost 30% of the entire Pustomity District SES's budget (V. Carande-Kulis, CDC, personal communication).

Recommendations

Based on this assessment, we developed recommendations with respect to the three main surveillance functions of data collection, analysis and interpretation, and retrospective and prospective responses.

Data Collection

• Eliminate punitive consequences to obtain accurate reporting;

• Restrict the number of routinely reportable diseases based on measures of mortality, morbidity, severity, communicability, and preventability;

• Categorize events under surveillance into a three-tiered surveillance system:

○ disease elimination (e.g., polio);

○ case-based (e.g., diphtheria); and

○ indicator-based (e.g., number of children immunized by two years of age);

• Simplify reporting procedures and forms by

○ limiting urgent reporting of diseases to those that require prompt institution of control measures;

○ requiring only information necessary to direct control measures and perform basic analyses; and

○ developing disease-specific forms with diseases chosen for case-based surveillance;

• Develop tiered (confirmed, probable, and suspected) standardized case definitions for all events under surveillance; and

• Computerize demographic and risk-factor data for systematic and detailed analysis of reported diseases and rapid dissemination of information.

Analysis and Interpretation

• Provide ongoing capacity for training in analytic epidemiology; and

• Base interventions on epidemiologic evidence. Use analytic epidemiology (case-control and cohort studies and presentation of data using 2 × 2 tables, odds ratios, relative risks, and tests of significance) for hypothesis generation, risk factor identification, outbreak investigations and intervention design and monitoring.

Retrospective and Prospective Responses

• Provide feedback to all reporting sources and share information across vertical program lines and with officials throughout the public health community in a timely fashion (e.g., via a monthly public health bulletin). A bulletin could include descriptions of important outbreak investigations, disease-specific analyses of surveillance data, graphic and tabular information on selected diseases, indicators of community health, and recommendations for public health concerns.

Current HIS Reform Efforts in Armenia

This assessment stimulated and guided reform efforts that were initiated in December 1992 through a cooperative project among the AMoH, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and CDC. This project provided technical and material assistance toward reform of the Armenian HIS. The approach focused on training a cohort of public health officials and epidemiologists in the modern aspects of epidemiology, biostatistics, surveillance techniques, and scientific communications; developing Armenia-specific case definitions; facilitating HIS reform strategies through workshops and training sessions; and developing the capacity to publish an epidemiologic bulletin.

Since 1996, this HIS reform activity has been self-sustained with no additional monetary support from USAID [6]. In 1996, the AMoH created a national HIS program for the development and reform of the HIS and the Armenian National Health Analytic-Information Centre [18]. The system has been transformed into a comprehensive HIS and includes chronic diseases, maternal and child health, and injury data. Diseases are now categorized by a three-tiered approach: disease elimination (e.g., polio), case-based (e.g., diphtheria) and indicator-based (e.g., number of children immunized by two years of age).

Preparations are now being made for additional training and to assess and improve clinic case diagnoses, management, and recording, and clinic records. New regional centers equipped with computers and faxes have been organized for the collection, analyses, and reporting of health information. National and regional public health bulletins are being published monthly in three languages - Armenian, Russian and English – and distributed to wide audiences. Tiered, standardized case definitions and essential health indicators for decision-making at the clinic and community level have been developed and disseminated. These include health status, performance, and resource indicators.

Comprehensive HIS reform is critical throughout the FSU. Timely, accurate, and relevant health information are necessary to assess the burden of disease and disability; understand changing health patterns; measure the needs for and improve services; address inequities in health; provide information for policy formulation and planning; and provide a basis for intra- and international comparisons on health status and care utilization [1]. Timeliness, accuracy, and relevancy are augmented by efficiency. Integrating all sources of data into one comprehensive HIS prevents duplicate recording and reporting across services and programs, averts labor-wasting inefficiencies, and saves scarce resources.

A comprehensive HIS includes the capacity to obtain data from vital registries, clinical, administrative, and other records; from provider and population-based surveys and sentinel systems for infectious and chronic diseases, and disabilities; and maternal and child health, nutrition, and program implementation indicators, including access, coverage, and service quality [1]. This reform activity should include the development of an indicator monitoring system based on selected essential, action-oriented indicators of health status, service performance, and resources that can be used for decision-making at the local level.

Summary

We found the AIDSS to be a complex and sensitive, yet costly and inefficient surveillance system for infectious diseases. Despite the lack of standardized case definitions, feedback of information, and computer technology, it functioned fairly well before 1991. However, the functioning and continuation of the AIDSS has been affected both directly and indirectly by events of the past decade.

Overall, the former AIDSS was useful because it detected cases of infectious diseases, estimated morbidity, monitored trends in disease occurrence, and documented outbreaks. The comprehensive no-cost health-care delivery system and compulsory reporting of diseases to the AMoH enhanced its flexibility, representativeness, and timeliness. The strengths of the AIDSS stemmed from the large numbers of health facilities and trained personnel and the separation of preventive from curative medicine, that secured an independent status (including separate budget) for preventive medicine and public health practitioners.

The AIDSS also had weaknesses. Though the system meticulously tracked persons (from birth to death), very few of these data were computerized, analyzed, or used to develop, direct, or evaluate public health policy. In most cases, when used, data guided regulation and punishment rather than public health decision-making. Simply put, data were used to fix blame and punish rather than to find and implement effective interventions.

Epidemiologists were motivated to perform actions that both pleased their supervisors and avoided the punishment of monetary loss or demotion. For example, it was common practice for epidemiologists to hide select cases of infectious disease and willfully underreport epidemic morbidity because outbreaks meant that the epidemiologists were not performing their duties of preventing and controlling infectious diseases. These disincentives to thoroughness and honesty resulted in surveillance data and reports that did not reflect true incidence and prevalence of disease, circumstances, needs, responses, or impacts [9].

Because the AIDSS was but a component of the systems designed for the entire FSU, the AIDSS did not address Armenia-specific needs. Further, because of the lack of tiered, standardized case definitions, there existed a potential for misclassification of diseases. Lack of feedback to reporting sources hampered improvements in clinical practice. Monitoring conditions for which there were no practical public health interventions, the multi-tiered and duplicative reporting processes, and the use of expensive and indirect monitoring and control measures such as excessive culturing, disinfection, and prolonged hospitalization led to waste of resources. As a result, the system did not guide control measures optimally nor use resources efficiently.

As the republics of the FSU embrace various aspects of democratization, improvement of public health surveillance systems such as the IDSS should be a goal if decision makers are to use credible data for informed public health practice.

Competing interests

We certify that we have participated sufficiently in the conception and design of this work, as well as its execution and the analyses of the data. Further, we have collaboratively written the manuscript and take public responsibility for it. We believe the manuscript represents valid work. We have reviewed the final version of the submitted manuscript and approve it for publication. Neither this manuscript nor one with substantially similar content under our authorship has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere. If requested, we shall produce the data upon which the manuscript is based for examination by the editors.

We certify that we have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. Drs. Wuhib, Chorba, MacKenzie, and McNabb were employees of the U.S. federal government when this work was performed and prepared for publication; therefore, it is not protected by the Copyright Act, and there is no copyright of which the ownership can be transferred. Dr. McNabb serves as corresponding author; his address is listed.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all SES epidemiologists in the respective Ministries of Health who shared their knowledge of the IDSS and contributed to the discussions on recommendations, and individuals from CDC including Drs. Daniel Bleed, Robin Ikeda, Lyle Conrad, Scott Wetterhall, Siiri Bennett, Gulbanu Altynbaeva and Scott Deitchman and Mr. Bruce Ross.

Contributor Information

Tadesse Wuhib, Email: tew7@cdc.gov.

Terence L Chorba, Email: tlc2@cdc.gov.

Vladimir Davidiants, Email: drd@armhealth.am.

William R Mac Kenzie, Email: wrmackenzie@mindspring.com.

Scott JN McNabb, Email: sym3@cdc.gov.

References

- Fisher G, Pappas G, Limb M. Prospects, problems and prerequisites for national health examination surveys in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:1639–1650. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker SB, Berkelman RL. Public health surveillance in the United States. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:164–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teutsch SM, Thacker SB. Planning a public health surveillance system. Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization. 1995;16:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy IR, Dittmann S, Sutter RW. Current situation and control strategies for resurgence of diphtheria in newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. Lancet. 1996;347:1739–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90811-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Epidemic malaria-Tadjikistan, 1995. MMWR. 1996;45:513–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemic malaria transmission – Armenia, 1997. MMWR. 1998;47:526–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO World malaria situation in 1994. Part III. Wkly Epidemiologic Rec. 1997;72:285–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine Emerging infections: Microbial threats to health in the United States Washington: National Academy Press; 1992. [PubMed]

- McNabb SJN, Chorba TL, Cherniack MG. Public health concerns in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the New Independent States. Current Issues in Public Health. 1995;1:136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Gellert GA. International health assistance for Eurasia. N EngI J Med. 1992;326:1021–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204093261512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public health assessment – Russian Federation, 1992. MMWR. 1992;41:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemic typhoid fever – Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 1997. MMWR. 1998;47:752–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellert GA. Prevention of nosocomial HIV infection in the Soviet Union-an international responsibility. N EngI J Med. 1990;323:1844–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012273232616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for evaluating surveillance systems. MMWR. 1988;37:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the guidelines. . MMWR. 2001;50:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass Rl. A perspective on environmental health in the USSR: research and practice. Archives of Environmental Health. 1975;30:391–5. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1975.10666732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass Rl. The SANEPID Service in the U.S.S.R. Public Health Rep. 1976;91:154–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenia Ministry of Health Prikaz (Adminstrative Directive) #550. 1996.