Abstract

The World Trade Center (WTC) disaster and its recovery work involved a range of hazardous occupational exposures that have not been fully characterized but can be reasonably assumed to have the potential to cause mucosal inflammation in the upper and lower airways. A high prevalence of lower airway disease (LAD) symptoms was reported by several early surveys. Clinical studies further categorized the diagnoses as irritant-induced asthma (of subacute onset), nonspecific chronic bronchitis, chronic bronchiolitis, or aggravated preexistent obstructive pulmonary disease in a substantial proportion of patients. Risk factors for WTC-related LAD included early (on September 11 or 12, 2001) arrival at the WTC site and work at the pile of the collapsed towers. Cigarette smoking (but not atopy) also seemed to be a risk factor for LAD. No data thus far suggest an increased incidence of neoplastic or interstitial lung disease, but ongoing surveillance is clearly necessary.

Keywords: Occupational medicine, Occupational lung disease, Asthma, Irritants, Inhalation injury, Bronchiolitis

Introduction

The terrorist attack on the World Trade Center (WTC), the subsequent tower collapse, and the 9.5-month recovery of the site exposed hundreds of thousands of people to debris, dust, smoke, and fumes. Surveys conducted after September 11, 2001, among rescue and clean-up workers and volunteers [1-5], office workers [6], building evacuees [7], and residents of Lower Manhattan [8-10] reported a high prevalence of symptoms suggestive of respiratory and other physical and psychological diseases. Preliminary reports on the clinical evaluation of WTC workers and volunteers suggested the need for dedicated multidisciplinary clinical centers to provide diagnostic and treatment services [11]. Seven years after the establishment of the first such center to characterize and treat presumably WTC-related occupational illnesses [12••], it is possible to summarize the experience with the short–and medium-term lower respiratory health effects observed in these workers.

Occupational Inhaled Toxicant Exposures at the World Trade Center

The collapse and burning of the WTC and neighboring buildings released a complex mixture of irritant dust, smoke, and gaseous materials. Smoldering fires continued until mid-December 2001, making it the longest-lasting urban fire in recorded US history. For months, the rescue, recovery, and service restoration endeavor exposed several tens of thousands of workers and volunteers to the pollutants released at the WTC site.

The characterization of the released toxicants at the WTC site is fragmentary and particularly deficient for its volatile components. Most dust samples were collected after the first 48 h of the attack (ie, after the exposure time period that has been most closely and consistently associated with lower respiratory symptoms and disease). The dust contained a complex mix of pulverized cement, glass fibers, asbestos, silica, lead, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, metals, and polychlorinated biphenyls [13, 14]. In a study of settled outdoor dust collected 4 days after the towers collapsed, more than 98% of the particles had an aerodynamic diameter exceeding 10 μm and a very alkaline pH [14]. Studies of settled dust inside buildings surrounding the WTC showed similar characteristics to those observed outdoors [15, 16].

In contrast to those studies, a study of suspended particles reported the following: 1) a higher proportion of fine (inhalable) particles (PM2.5) in October 2001 (16%–86% of total dust) and April 2002 (7%–85% of total dust); 2) a higher concentration of fine particles near the center of the WTC disaster site, with a decreasing gradient toward its periphery; and 3) a decrease in concentrations of total dust and fine particles between those two time points [17]. Studies analyzing dust particles recovered from WTC workers’ sputum and lung biopsy samples have demonstrated the presence of unusual metal alloys and carbon nanotubes, respectively [18, 19]. Of course, the significance of those findings in relation to potential lung disease causation remains to be established.

Aside from the few analytical exposure studies summarized previously, several symptom surveys [2, 5, 20] and clinical studies [12••] recorded self-reported information on occupational exposures at the WTC site. Early arrival at the site and long exposure duration were highly common among workers at the WTC. For instance, in one clinical study, about half of the workers arrived at the WTC site within the first 48 h of the terrorist attack, and their occupational exposure duration averaged 18 weeks [12••]. The specific duties of the different workers also usually determined their arrival time, location within the recovery area, and exposure duration. For instance, laborers primarily participated in cleaning of the buildings surrounding the fallen towers, arrived on or after the fifth day after the terrorist attack, and their exposure duration averaged about 20 weeks [21]. Firefighters, police officers, and ambulance workers, on the other hand, arrived very soon after the attack and worked at or very close to the site of the fallen towers, but their exposure duration was less prolonged. Most workers stayed within certain specific locations, and the working population declined exponentially after the first few days and weeks of the towers’ collapse.

Risk Factors for Presumed World Trade Center–Related Lower Airway Disease

From the limited knowledge about the inhaled particles at the WTC disaster site briefly summarized in the previous section, and in consideration of their hydrosolubility and size characteristics, the estimation has been that many of them were irritants capable of causing inflammatory mucosal changes, with the upper airway as their primary, but not exclusive target [22, 23]. There clearly were enough particulates capable of reaching and injuring the distal airways. Most studies have consistently identified early arrival at the WTC disaster site (within the first 48 h of the attack) as the most consistent risk factor for the presumed WTC-related lower airway diseases (LADs) that have been observed thus far [2, 5, 12••, 21]. Exposure duration seems to be a weaker predictor of LAD in smaller clinical studies [12••] but has been suggested by much larger symptom-based survey studies [5, 24•].

Other factors in all likelihood contributed to determine individual susceptibility to inhaled toxicants, including worksite location (eg, near the site of the collapsed towers [5]), occupational activities [21], clean-up methods, and use of appropriate protective equipment and strategies. The well-reported limited availability, adequacy, and/or use of protective respiratory equipment in all likelihood enhanced the respiratory hazard [17, 20, 25, 26]. Besides these exposure-related factors, potential health effects also may have varied depending on underlying medical conditions (including presumed [12••] or confirmed [27] preexisting lung disease). A history of tobacco use, identified as a risk factor for irritant-induced occupational asthma [28], was identified as such in the single clinical study of WTC workers [12••], in which, it needs to be noted, aggravated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was also one of the outcome diagnoses. On the other hand, atopy did not seem to be a risk factor for LAD (as it seemed to be for presumed WTC-related rhinitis and upper airway disease [27]). Additional individual susceptibility factors remain to be investigated.

Asthma and Lower Airway Diseases

Although there have been a good number of symptom-based survey studies and a few case reports, only one clinical study has been published to date characterizing the apparent WTC-related pulmonary diseases observed in former workers at the WTC [12••], and documenting that asthma is not the only LAD that appears to have resulted from WTC occupational exposures.

Most individuals who developed clinically characterized respiratory illness usually did so less than 6 months after termination of their occupational exposures at the WTC disaster site [12••], and a symptom-based survey suggested an increased incidence (above the expected population-based rate) of self-reported asthma for 18 months after September 11, 2001 [24•]. Symptom surveys reported a substantial prevalence of lower respiratory symptoms, including exertional and nonexertional dyspnea, wheezing, and cough [2, 20, 29]. Surveys with spirometric data [2, 4, 20, 29] indicated that the most common abnormality found was that of a reduced forced vital capacity (FVC), which can result from restriction or from gas trapping [30]. The few studies with substantial occupational surveillance spirometric data from before the WTC attack clearly documented that the decline far exceeded what would be expected from aging, even among smokers [2, 4]. Although clinical studies have suggested obstruction as the underlying physiologic explanation for that finding, correlations have been notoriously weak and fail to explain fully each individual case [31].

Irritant-Induced Asthma

One screening survey conducted 6 months after 9/11 reported the presence of bronchial hyperreactivity in 20% of firefighters present at the WTC on the morning of the attack, compared with 8% of those who arrived within 48 h of the attack [2]. Although many workers were diagnosed with irritant-induced asthma, only about 25% showed evidence of nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity [12••, 31]. Furthermore, most workers who were eventually diagnosed formally with irritant-induced asthma had a rather insidious onset of symptoms, sometimes up to a few weeks or months after leaving the site [12••]. That insidious and gradual onset of symptoms allowed most workers firmly diagnosed with irritant-induced asthma to continue working for as long as has been documented. In patients with a clinical diagnosis of irritant-induced asthma, bronchial hyperreactivity was almost always mild (eg, provocative concentration causing a 20% drop in forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1] of 8 or 10 mg/mL), and in virtually all cases, the bronchial hyperreactivity response pattern was characterized by a similar reduction in both FVC and FEV1 [12••].

Symptomatic patients who did not meet criteria for a diagnosis of asthma were reclassified into other clinical syndromes depending on clinical findings. Overall, from a random sample of 168 patients evaluated in great detail, patients were classified as having irritant-induced occupational asthma, aggravated COPD, chronic bronchitis, and small airway disease in 22.6%, 14.3%, 13.1%, and 3.6% of the patients, respectively [12••].

World Trade Center–Exacerbated Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Many workers with preexistent obstructive lung disease seemed to experience substantial aggravation of their condition after their WTC exposures. In the case of asthmatics, many were on no treatment or only on as-needed (and then rarely so), short-acting, inhaled bronchodilators and required maintenance medications after their WTC work experience. Preexistent COPD was suspected when fixed obstruction, overinflation, decreased diffusion capacity, and/or emphysematous chest CT scan changes (usually mild in degree) were observed in individuals who had also been cigarette smokers [12••]. It is interesting to note that the finding of an obstructive ventilatory impairment by spirometry was more frequent among ever-smokers [12••], but not in all studies [20].

Nonspecific Chronic Bronchitis

It is clear that evidence of nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity has been present in only about 25% of the patients evaluated by pulmonary specialists [12••, 31]. Although several bronchial hyperreactivity testing limitations could explain this finding, patients with asthma symptoms, practically normal plethysmographic lung volumes and/or diffusion capacity, and no evidence of bronchial hyperreactivity or air trapping by chest CT scan were reclassified as having a nonspecific chronic bronchitis syndrome. This group accounted for 13% of a clinical sample (and close to 25% of those with presumed WTC-related LAD). Treatment of these cases may not differ from that of asthma or COPD, with similarly apparently satisfactory results.

Chronic Bronchiolitis

Besides the first two case reports of biopsy-proven, presumably WTC-related constrictive bronchiolitis [12••, 32], Mendelson et al. [33] published a case series reporting on additional cases strongly suggested by the presence of end-expiratory air trapping on paired-view chest CT scans. The latter allowed the classification of some cases of WTC-related LAD as bronchiolitis [12••].

Bronchiolitis and small airway dysfunction are distinctly difficult to diagnose in clinical pulmonary medicine, and open lung biopsy has been extremely rarely indicated in patients whose lung function abnormalities have been quantitatively relatively mild [2, 12••]. Besides the studies mentioned, several findings have suggested the presence of small airway dysfunction more frequently than diagnosed in symptomatic patients. Those findings have included the following: 1) the frequent finding of reduced FVC in spirometry (with preserved TLC) [30]; 2) the low frequency of methacholine reactivity generally and in individuals with asthma-like clinical presentations [34]; 3) FVC reduction response to bronchoprovocation testing [35]; 4) air trapping by paired inspiratory/expiratory chest CT scans [33]; and 5) evidence of long-term, accelerated FVC decline in those lacking bronchodilator response, which could suggest the effect of inflammatory remodeling occurring at the level of the small airways [36•, 37]. A study using impulse oscillometry technique lacked a characterization of occupational lung disease diagnoses [38], and when that is done, this technique does not seem to provide sufficiently specific diagnostic or physiologic information [39].

Bronchiolitis and small airway dysfunction are part of the spectrum of abnormalities associated with asthma, particularly during chronic inflammatory remodeling. Finally, a few highly prevalent comorbidities in this patient population may contribute some confounding factors given their potential association with small airway disease. Rhinitis and overweight/obesity were prevalent in about 80% of the WTC workers [12••, 36•], and both are suspected to be associated with small airway dysfunction [40] .

Other Pulmonary Diseases

A higher-than-expected incidence of histologically confirmed sarcoid-like granulomatous lung disease or sarcoidosis was reported among firefighters and ambulance workers in the first 5 years after the attack on the WTC [41]. All 26 reported cases had intrathoracic adenopathy, and 6 (23%) had extrathoracic manifestations. On the other hand, only 3 of the 26 patients had total lung capacity or diffusion capacity below 80% of predicted. Sarcoidosis is often asymptomatic and found through screening chest radiographs; thus, some cases diagnosed after 9/11 may have been the result of increased detection from screening of a large number of individuals with respiratory symptoms, and increased reporting for disability purposes.

Although parenchymal or interstitial lung diseases could potentially result from WTC exposures [42], surveillance among firefighters thus far has failed to reveal an increased incidence of this type of disease [41], and clinical studies among other types of workers have failed to identify a substantial number of cases [12••, 31]. There have been isolated case reports of other lung diseases, such as eosinophilic pneumonia [43], interstitial fibrosis with predominantly peribronchiolar changes [12••, 19], and granulomatous pneumonitis [44]. Overall, cases of interstitial lung disease of any type, including sarcoidosis, remain few and heterogeneous when compared with the thousands of WTC-exposed individuals with upper and lower airway disease, but surveillance systems are (and need to stay) in place to try to identify additional incident cases.

Longitudinal Trends

With regard to lower respiratory symptom trends, among WTC firefighters, the prevalence of shortness of breath and wheezing remained relatively unchanged from 2001 to 2005. On the other hand, daily cough (more prevalent at baseline than shortness of breath or wheezing) decreased markedly by the second year of follow-up [2, 45]. The decline in daily cough did not seem to be explained by a decrease in a few selected rhinosinusitis symptoms, as those remained relatively stable [45].

Longitudinal follow-up of self-reported incident asthma diagnoses among recovery workers, community reoccupants, and passersby demonstrated an increase over expected general population rates for about 18 months after September 11, 2001 [24].

With regard to functional changes after WTC occupational exposures, and among non-firefighting WTC workers, average spirometric measurements remained quite stable, with a unimodal normal distribution of changes. The only significantly associated risk factors for accelerated spirometric decline in a minority of those workers were the absence of bronchodilator response at baseline and further weight gain on follow-up [36•]. As expected, current smoking also seemed to have an adverse functional effect and was controlled for in a similar analysis among firefighters and emergency medical service workers. This latter study corroborated the observation of stability in lung function after exposure [46•]. Both studies demonstrated that early arrival at the WTC site (a risk factor for development of occupationally related LAD) was not a predictor of accelerated FVC and FEV1 decline on follow-up.

Other Comorbidities

Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Upper Airway Disease

Rhinosinusitis, perennial and often associated with pharyngitis and laryngitis, was diagnosed in almost 80% of those in the largest published clinical case series of WTC worker patients [12••, 23]. The irritant-induced inflammatory process led to nonallergic rhinosinusitis or worsening of preexisting allergic rhinosinusitis. A triad of WTC-related lower and upper airway and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was the most common presentation (30%) among workers treated for chronic persistent illness in or before 2003 [12••].

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

A survey of 332 firefighters with WTC-related cough (severe enough to require a medical leave) reported that 87% of them had heartburn [2]. In the only clinical study that has thus far investigated this issue, 58% of patients experienced chronic GERD symptoms, in most cases associated with symptoms and laryngoscopic findings consistent with laryngopharyngeal reflux disease [12••]. Furthermore, temporally related GERD shared with LAD diagnosis [12••], and probably post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms [47], the association with arrival at the WTC site within the first 48 h of the attack. GERD also seemed to be associated with the presence of spirometric abnormalities and with being diagnosed with a WTC-related LAD, and not with being diagnosed with a WTC-related psychiatric disease [48]. GERD is known to be associated with lung disease [49-51] and is a well-known cause of chronic cough. Methacholine challenge test was helpful in excluding asthma in patients with GERD-related asthma symptoms. In detailed clinical studies, however, the reflux syndromes have been somewhat heterogeneous [48]; thus, more research is necessary to clarify this association.

Other Medical Conditions

Obstructive sleep apnea is diagnosed often in a population characterized by 80% or higher predominance of both male sex and prevalence of overweight/obesity. A trend toward more severe apnea–hypopnea index with increasing occupational WTC exposure may deserve further investigation by future studies [52]. Respiratory irritant exposure and/or some of the already mentioned comorbidities may explain some of the cases of vocal cord dysfunction that have been identified [53] and certainly needs to be identified, as it frequently mimics asthma or complicates its management. No specific cancer types have been identified as resulting from exposure to the WTC disaster to date, but cancers generally have long latency periods. Prospective studies are ongoing to detect elevated rates of any cancers as well as other diseases.

Psychological Diseases

It should not be necessary to emphasize that psychological conditions affect respiratory symptom perception, adherence to treatment, response to treatment, and possibly disease course. Clinical studies of former WTC workers and volunteers have documented formally diagnosed psychological illness in nearly 42% of workers [12••]. The most frequent diagnoses (often combined) have been chronic PTSD, major depressive disorder, and agoraphobia with panic disorder [12••].

In the wake of the disaster, rescue and recovery workers and volunteers, as well as residents, office workers, and students in downtown Manhattan were subjected to daily stress for months. Many workers witnessed the deaths of friends, relatives, and/or coworkers. Some were exposed to human remains, feared a second attack, or experienced uncertainty about the safety of their worksites. The role of the mass communication media in amplifying the traumatic experience has been largely unexplored [54]. Follow-up symptom survey studies have identified several risk factors for the development of possible chronic PTSD and major depressive disorder [47, 55]. From the occupational point of view, in at least some symptom surveys, early arrival and exposure duration seemed to be related to the risk of developing chronic PTSD symptoms [47], but that had not been identified in clinical (although smaller) studies [12••].

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Medicolegal Considerations

Clinical expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of WTC workers’ symptoms was developed at the WTC Health Effects Treatment Program, established at Mount Sinai Hospital in January 2003 as the first dedicated multidisciplinary clinical center to provide individualized diagnostic and treatment services to these workers [12••].

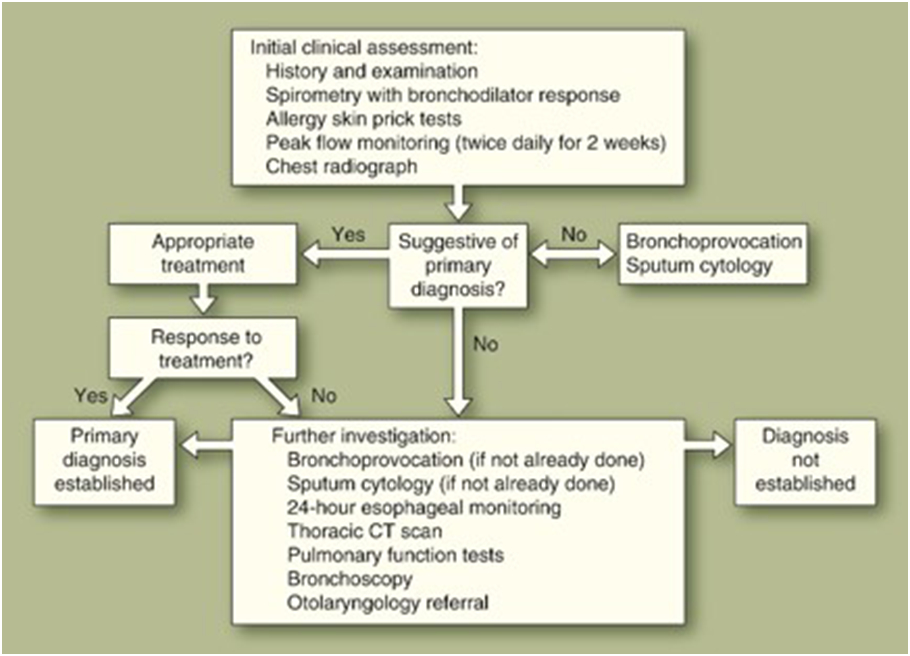

The evaluation of these patients required a very detailed inventory of clinical symptoms, as well as occupational and WTC-related exposure history. To characterize the type of LAD, and given the high prevalence of chronic cough (defined as unexplained cough persistent for >8 weeks, with a normal chest radiograph), a previously published diagnostic algorithm was adapted for the purpose of evaluating symptomatic workers (Fig. 1) [56]. The diagnostic approach was also consistent with the recommended strategy for investigation of a reduced FVC [30], which is the most common spirometric abnormality reported in this patient population [2, 12••, 20].

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for the investigation of lower respiratory symptoms among former World Trade Center workers and volunteers. (Adapted from Brightling et al. [56])

Challenges in the documentation of abnormalities in the WTC worker population have been as follows: 1) general unavailability of pre-episode pulmonary functional data, 2) the fact that diagnostically demonstrable bronchial hyperreactivity is often intermittent or can disappear in occupational asthma with time after exposure removal [28, 57], and 3) the general inadequacy of available testing methods for detection of small airway dysfunction [12••, 33, 34, 38, 39].

Treatment of the different conditions followed generally accepted and established guidelines in the case of asthma or COPD. In the case of the nonspecific chronic bronchitis syndrome and chronic bronchiolitis, the treatment was similar, but with generally less satisfactory results or clear responses in the latter. One crucially important component of the treatment was the adequate control of the symptoms of the frequent comorbidities described previously.

In the case of the former WTC rescue and recovery workers, prevention was aimed at post-WTC occupational exposures, which were considerable for many occupations (eg, firefighters, demolition and construction laborers, construction trade workers, ironworkers, welders). For the roughly 50% of workers who were actively employed 2 years after ending their WTC work, WTC Health Effects Treatment Program physicians used medical treatment and reduced exposure and/or vocational retraining to maintain the workers’ productivity to the extent possible (de la Hoz, unpublished data).

The medicolegal classification of these workers’ LAD was generally based on the objective documentation of a clinical diagnosis (as described previously), review (when available) of previous medical records and pulmonary functional data, symptom onset within 6 months of leaving the WTC site [12••], and objective evidence of functional deficits and residual disability. In many cases, comorbidities (particularly psychological and musculoskeletal diseases) added considerably to occupational LAD-related disability. The low filing rate, high rate of controversion of, and/or prolonged delay in processing of claims before disability boards for firefighters, police officers, and New York City workers [58] and the New York State Workers’ Compensation Board [59] have recently begun to be documented.

Conclusions

It seems clear that occupational exposures at the WTC site were hazardous to exposed workers. High prevalence of lower respiratory symptoms, functional abnormalities, and marked functional decline after WTC occupational exposures were documented by surveys conducted during or shortly after the 9.5-month recovery effort. Irritant-induced asthma has been the best documented diagnosis, but clinical studies have clearly revealed other presentations of LAD, partly as a result of preexisting disease or risk factors. Cigarette smoking (but not atopy) seemed to be a risk factor for diagnosis of a presumed WTC-related LAD. The different LAD diagnoses described thus far are, as expected, overlapping, classification is often difficult at a particular point in time, and classification could change with continued longitudinal observation of individual patients. There has been more evidence (though not unmitigated) for an obstructive than for a restrictive impairment as the underlying explanation for the frequently observed reduction in FVC among WTC workers. The most challenging diagnosis to document is that of chronic bronchiolitis and small airway disease given the known limitations of pulmonary functional testing. Thus far, large longitudinal studies have demonstrated remarkable spirometric stability in this patient population, with further weight gain and lack of bronchodilator response as risk factors for functional deterioration. Lack of bronchodilator response may reflect small airway dysfunction and postinflammatory remodeling. Although one study suggested an increased incidence of sarcoidosis (or sarcoidosis-like) abnormalities, particularly the first year after the towers collapsed, no study thus far has shown an increased incidence of interstitial or neoplastic lung diseases. Similarly, self-reported incident asthma diagnoses, increased after September 11, 2001, seemed to return to the expected population baseline 18 months later. Clearly, long-term, ongoing surveillance is necessary to follow these trends and identify possible late-emerging diseases. Future research is likely to investigate additional susceptibility risk factors for disease and clinical deterioration.

Acknowledgments

The publication of this work was made possible by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, cooperative agreement no. U10 OH008225. The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Herbstman JB, Frank R, Schwab M, et al. : Respiratory effects of inhalation exposure among workers during the clean-up effort at the World Trade Center disaster site. Environ Res 2005, 99:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prezant DJ, Weiden M, Banauch GI, et al. : Cough and bronchial responsiveness in firefighters at the World Trade Center site. N Engl J Med 2002, 347:806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buyantseva LV, Tulchinsky M, Kapalka GM, et al. : Evolution of lower respiratory symptoms in New York police officers after 9/11: a prospective longitudinal study. J Occup Environ Med 2007, 49:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banauch GI, Hall C, Weiden M, et al. : Pulmonary function after exposure to the World Trade Center collapse in the New York City Fire Department. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 174:312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler K, McKelvey W, Thorpe L, et al. : Asthma diagnosed after September 11, 2001 among rescue and recovery workers: findings from the World Trade Center Health Registry. Environ Health Perspect 2007, 115:1584–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trout D, Nimgade A, Mueller A, et al. : Health effects and occupational exposures among office workers near the World Trade Center disaster site. J Occup Environ Med 2002, 44:601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Surveillance for World Trade Center disaster health effects among survivors of collapsed and damaged buildings. MMWR Surveill Summ 2006, 55:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Self-reported increase in asthma severity after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center-Manhattan, New York, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002, 51:781–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reibman J, Lin S, Hwang S-AA, et al. : The World Trade Center Residents’ Respiratory Health Study: new-onset respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function. Environ Health Perspect 2005, 113:406–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin S, Reibman J, Bowers JA, et al. : Upper respiratory symptoms and other health effects among residents living near the World Trade Center site after September 11, 2001. Am J Epidemiol 2005, 162:499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin SM, Herbert R, Skloot G, et al. : Health effects of World Trade Center site workers. Am J Ind Med 2002, 42:545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.••. de la Hoz RE, Shohet MR, Chasan R, et al. : Occupational toxicant inhalation injury: the World Trade Center (WTC) experience. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2008, 81:479–485. This article provides the clinical characterization of the LAD (including irritant-induced asthma) observed between 2003 and 2006 and the second case report of biopsy-proven chronic bronchiolitis.

- 13.Wallingford KM, Snyder EM: Occupational exposures during the World Trade Center disaster response. Toxicol Ind Health 2001, 17:247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lioy PJ, Weisel C, Millette JR, et al. : Characterization of the dust/smoke aerosol that settled east of the World Trade Center (WTC) in Lower Manhattan after the collapse of the WTC 11 September 2001. Environ Health Perspect 2002, 110:703–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Offenberg JH, Eisenreich SJ, Chen LC, et al. : Persistent organic pollutants in the dusts that settled across Lower Manhattan after September 11, 2001. Environ Sci Technol 2003, 37:502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Offenberg JH, Eisenreich SJ, Gigliotti CL, et al. : Persistent organic pollutants in dusts that settled indoors in lower Manhattan after September 11, 2001. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 2004, 14:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geyh AS, Chillrud S, Williams DL, et al. : Assessing truck driver exposure at the World Trade Center disaster site: personal and area monitoring for particulate matter and volatile organic compounds during October 2001 and April 2002. J Occup Environ Hyg 2005, 2:179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fireman EM, Lerman Y, Ganor E, et al. : Induced sputum assessment in New York City firefighters exposed to World Trade Center dust. Environ Health Perspect 2004, 112:1564–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu M, Gordon RE, Herbert R, et al. : Lung disease in World Trade Center responders exposed to dust and smoke-carbon nanotubes found in the lungs of WTC patients and dust samples. Environ Health Perspect 2010, 118:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Physical health status of World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers and volunteers—New York City, July 2002–August 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004, 53:807–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de la Hoz RE, Hill S, Chasan R, et al. : Health care and social issues of immigrant rescue and recovery workers at the World Trade Center site. J Occup Environ Med 2008, 50:1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shusterman D: Toxicology of nasal irritants. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2003, 3:258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Hoz RE, Shohet MR, Cohen JM: Occupational rhinosinusitis and upper airway disease: the World Trade Center experience. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2010, 10:77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.•. Brackbill RM, Hadler JL, DiGrande L, et al. : Asthma and posttraumatic stress symptoms 5 to 6 years following exposure to the World Trade Center terrorist attack. JAMA 2009, 302:502–516. This was a longitudinal follow-up of self-reported incident asthma diagnoses and PTSD symptoms from the largest registry of WTC-exposed individuals.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Use of respiratory protection among responders at the World Trade Center—New York City, September 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002, 51:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman DM, Baron SL, Bernard BP, et al. : Symptoms, respiratory use, and pulmonary function changes among New York City firefighters responding to the World Trade Center disaster. Chest 2004, 125:1256–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de la Hoz RE, Shohet MR, Wisnivesky JP, et al. : Atopy and upper and lower airway disease among former World Trade Center workers and volunteers. J Occup Environ Med 2009, 51:992–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malo J-L, L’Archeveque J, Castellanos L, et al. : Long-term outcomes of acute irritant-induced asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 179:923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salzman SH, Moosavy FM, Miskoff JA, et al. : Early respiratory abnormalities in emergency services police officers at the World Trade Center site. J Occup Environ Med 2004, 46:113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. : Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005, 26:948–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiden MD, Ferrier N, Nolan A, et al. : Obstructive airways disease with air trapping among firefighters exposed to World Trade Center dust. Chest 2010, 137:566–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann JM, Sha KK, Kline G, et al. : World Trade Center dyspnea: bronchiolitis obliterans with functional improvement: a case report. Am J Ind Med 2005, 48:225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendelson DS, Roggeveen M, Levin SM, et al. : Air trapping detected on end-expiratory high resolution CT in symptomatic World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers. J Occup Environ Med 2007, 49:840–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de la Hoz RE, Berger KI, Klugh TT, et al. : Frequency dependence of compliance in the evaluation of patients with unexplained respiratory symptoms. Respir Med 2000, 94:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibbons WJ, Sharma A, Lougheed D, Macklem PT: Detection of excessive bronchoconstriction in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 153:582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.•. Skloot GS, Schechter CB, Herbert R, et al. : Longitudinal assessment of spirometry in the World Trade Center Medical Monitoring Program. Chest 2009, 135:492–498. This was a longitudinal follow-up of spirometric measurements.

- 37.Bergeron C, Al Ramli W, Hamid Q: Remodeling in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009, 6:301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oppenheimer BW, Goldring RM, Herberg ME, et al. : Distal airway function in symptomatic subjects with normal spirometry following World Trade Center dust exposure. Chest 2007, 132:1275–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de la Hoz RE, Lessnau K, Lowenstein S: Oscillometric abnormalities in former World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers and volunteers [abstract P1050]. Abstracts of the 2009 Annual Meeting of the European Respiratory Society. Available at http://www.ersnet.org/learning_resources_player/abstract_print_09/main_frameset.htm. Accessed April 12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan EJ, Hall DR: Abnormalities of lung function in hay fever. Thorax 1976, 31:80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izbicki G, Chavko R, Banauch GI, et al. : World Trade Center “sarcoid-like” granulomatous pulmonary disease in New York City Fire Department rescue workers. Chest 2007, 131:1414–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szeinuk J, Padilla ML, de la Hoz RE: Potential for diffuse parenchymal lung disease after exposures at World Trade Center Disaster site. Mt Sinai J Med 2008, 75:101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rom WN, Weiden M, García R: Acute eosinophilic pneumonia in a New York City firefighter exposed to World Trade Center dust. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166:797–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Safirstein BH, Klukowicz A, Miller R, Teirstein A: Granulomatous pneumonitis following exposure to the World Trade Center collapse. Chest 2003, 123:301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webber MP, Gustave J, Lee R, et al. : Trends in respiratory symptoms of firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster: 2001–2005. Environ Health Perspect 2009, 117:975–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.•. Aldrich TK, Gustave J, Hall CB, et al. : Lung function in rescue workers at the World Trade Center after 7 Years. N Engl J Med 2010, 362:1263–1272. This was another longitudinal follow-up of spirometric measurements.

- 47.Perrin MA, DiGrande L, Wheeler K, et al. : Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. Am J Psychiatry 2007, 164:1385–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de la Hoz RE, Christie J, Teamer J, et al. : Reflux symptoms and disorders and pulmonary disease in former World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers and volunteers. J Occup Environ Med 2008, 50:1351–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Wallander M-A, et al. : Gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma-a longitudinal study in U.K. general practice. Chest 2005, 128:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kempainen RR, Savik K, Whelan TP, et al. : High prevalence of proximal and distal gastroesophageal reflux disease in advanced COPD. Chest 2007, 131:1666–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morehead RS: Gastroesophageal reflux disease and non-asthma lung disease. Eur Respir J 2009, 18:233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de la Hoz RE, Aurora RN, Landsbergis P, et al. : Snoring and obstructive sleep apnea among former World Trade Center rescue workers and volunteers. J Occup Environ Med 2010, 52:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de la Hoz RE, Shohet MR, Bienenfeld LA, et al. : Vocal cord dysfunction in former World Trade Center (WTC) rescue and recovery workers. Am J Ind Med 2008, 51:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Randall RD, Bryant RA, Amsel L, et al. : The psychology of ongoing threat. Am Psychol 2007, 62:304–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al. : Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med 2002, 346:982–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brightling CE, Ward R, Goh KL, et al. : Eosinophilic bronchitis is an important cause of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999, 160:406–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malo J-L, Ghezzo H: Recovery of methacholine responsiveness after end of exposure in occupational asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004, 169:1304–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Trade Center Medical Working Group of New York City: 2009 Annual Report on 9/11 Health. Available at http://www.labor.state.ny.gov/agencyinfo/pdfs/9-11_WPTF_Annual_Report_2009_0601.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 59.New York State Workers’ Compensation Board. World Trade Center cases in the New York Workers’ Compensation System. Available at http://www.wcb.state.ny.us/content/main/TheBoard/WCBWTCReport2009.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2010. [Google Scholar]