Abstract

Nemaline myopathy is a skeletal muscle disease that affects 1 in 50 000 live births. The objective of this study was to develop a narrative synthesis of the findings of a systematic review of the latest case descriptions of patients with NM. A systematic search of MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Scopus was performed using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using the keywords pediatric, child, NM, nemaline rod, and rod myopathy. Case studies focused on pediatric NM and published in English between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020, in order to represent the most recent findings. Information was collected about the age of first signs, earliest presenting neuromuscular signs and symptoms, systems affected, progression, death, pathologic description, and genetic changes. Of a total of 385 records, 55 case reports or series were reviewed, covering 101 pediatric patients from 23 countries. We review varying presentations in children ranging in severity despite being caused by the same mutation, in addition to current and future clinical considerations relevant to the care of patients with NM. This review synthesizes genetic, histopathologic, and disease presentation findings from pediatric NM case reports. These data strengthen our understanding of the wide spectrum of disease seen in NM. Future studies are needed to identify the underlying molecular mechanism of pathology, to improve diagnostics, and to develop better methods to improve the quality of life for these patients.

Keywords: nemaline myopathy, myopathy, sarcomere, muscle

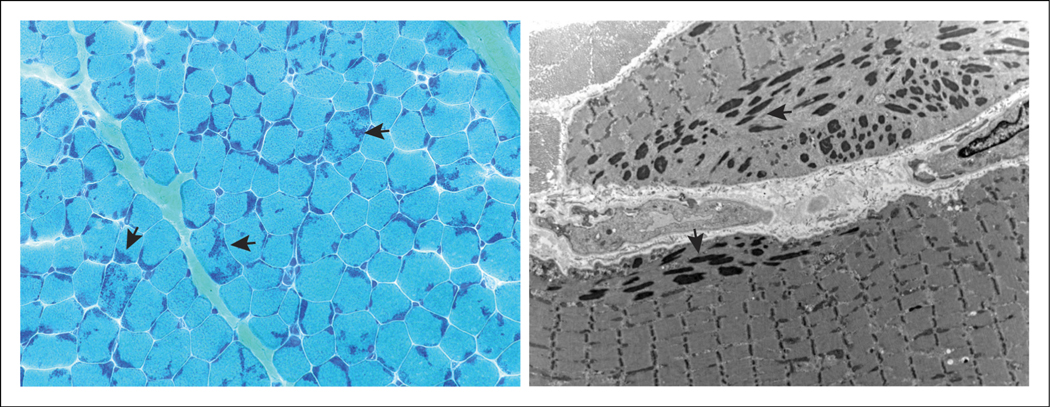

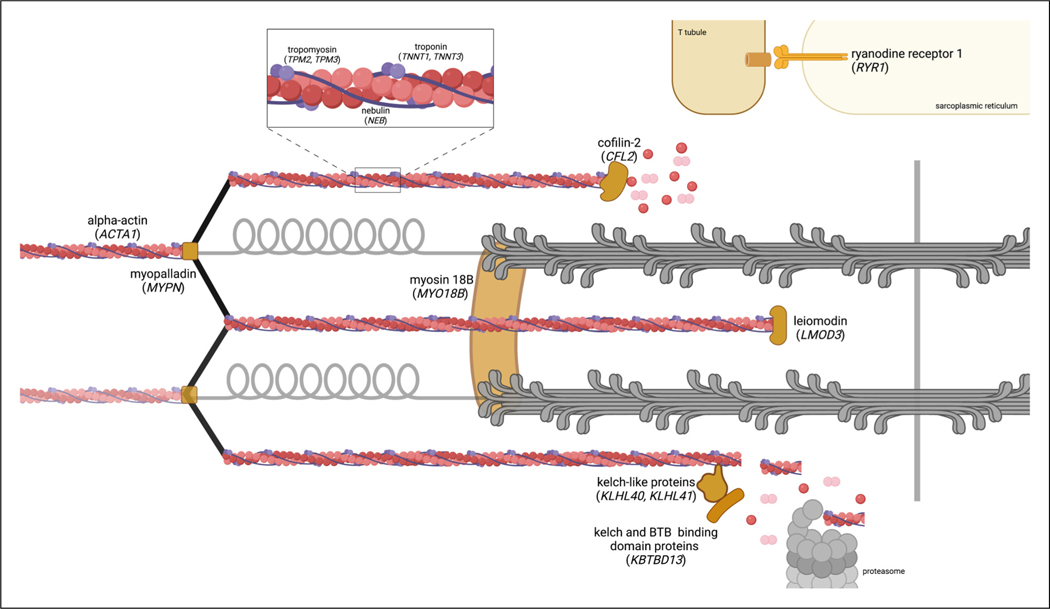

Nemaline myopathy (NM) is a primary skeletal muscle disease and histopathologic diagnosis with variable clinical presentation and genetic causes. It has an estimated incidence of 1 in 50 000 live births.1 The disorder was first described in 1963 in the case of a child with hypotonia and “microgranules” in a muscle biopsy.2,3 Clinicohistopathologic diagnosis of several congenital myopathies includes the detection of such aggregates, distinguished as cores, electron-dense rods, or central nuclei.4 Rods detected in the sarcoplasm or inside the nucleus leads to a diagnosis of NM. These rods are often seen emanating from the muscle Z-disc, the anchor point of the sarcomere unit (Figure 1). Sarcomeric proteins have been shown to make up a portion of these aggregates (Figure 2).5,6 Additionally, individual muscle fibers may be affected by either atrophy or hypertrophy.7,8

Figure 1.

Pathologic findings in NM. Light microscopy of Gomori trichrome-stained muscle biopsy shows nemaline bodies within various fibers (left, cross-section). Electron-dense rods disrupt sarcomeric organization in the muscle (right, longitudinal section). Arrows highlight some of the present nemaline rods/bodies.

Figure 2.

Sarcomere-related proteins causative of NM. Created with BioRender.com.

To date, pathogenic variants in 12 genes have been identified as causative of NM (Table 1).9 Several of the implicated proteins localize to the thin filament of the sarcomere: skeletal alpha-actin 1 (ACTA1), cofilin (CFL2), leiomodin 3 (LMOD3), nebulin (NEB1), and kelch repeat and BTB domain containing protein 13 (KBTBD13).10–15 Mutations have also been found in Kelch-like family member proteins (KLHL40, KLHL41) that regulate the protein turnover of thin filaments.16 Additional structural or regulatory components of the sarcomere may be affected as shown by mutations in genes encoding myosin 18B (MYO18B), myopalladin (MYPN), ryanodine receptor 1 (RYR1), slow skeletal muscle troponin T (TNNT1), fast skeletal muscle troponin T (TNNT3), and slow muscle alpha-tropomyosin (TPM2, TPM3).17–21 As far as the functions of the proteins, skeletal alpha-actin is the main component of the actin filament, which is structurally supported by nebulin, troponin, tropomyosin, and myopalladin.10,13,17,19,21 Leiomodin is an actin nucleator, while cofilin is an actin-severing protein involved in maintaining the balance between filamentous and monomeric actin.11,12 Meanwhile, the KBTBD13 adaptor protein works with KLHL40 and KLHL41 to regulate thin filament stability with the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Figure 2).15,16

Table 1.

Genetics of Pediatric NM Case Reports (2010–2020): Genetic Changes Described in the Cases Reviewed Presently, Including Number of Cases by Gene Symbol, Genetic and Protein Changes, and a Description of Protein Function.

| Gene Symbol | Cases | Protein Function | Genetic and Protein Changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTA1 | 22 | Principal actin isoform of skeletal muscle thin filament | c.283C>A, p.Asn94Lys | Saito 2011 |

| c.350A>G, p.Asn117Ser | Yang 2016 | |||

| c.356G>A, p.Glu85Lys | Lehtokari 2018 | |||

| c.407T>C, p.Val136Ala | Ennis 2015 | |||

| c.430C > T, p.Leu144Phe | Saito 2011 | |||

| c.448A>G, p.Thr150Ala | Miyatake 2014 | |||

| c.455G>C, p.Gly152Ala | Ravenscroft 2011 | |||

| c.478G>A, p.Gly160Ser | Yokoi 2019 | |||

| c.487C>G, p.His163Asp | Moreno 2017 | |||

| c.557A>G, p.Asp186Gly | Levesque 2013 | |||

| c.611C>T, p.Thr204Ile | Moreno 2017 | |||

| c.760A>C, p.Asn254His | Pula 2020 | |||

| c801G>C, p.Gly270Arg | Saito 2011 | |||

| c.868G>A, p.Asp290Asn | Seidahmed 2016 | |||

| c.871A>T, p.Tyr5927HisfsX17 | Moureau-Le Lan 2018 | |||

| c.911delG, p.Gly304AlafsX24 | Friedman 2014 | |||

| c.1049C>T, p.Ser350Leu | Moreno 2017 | |||

| c.1074G>T, p.Trp358Cys | Gatayama 2013 | |||

| c.1075A>C, p.Ile359Leu | Yeşilbaş 2019 | |||

| c.1127G > C, p.Cys376Ser | Waisayarat 2015 | |||

| CFL2 | 6 | Actin-severing and actin-binding protein | c.19G>A, p.Val7Met | Ockeloen 2012 |

| c.100_103delAAAG, p.Lys34Glnfs*6 | Ong 2014 | |||

| c.235G>T, p.Asp79Tyr | Fattori 2018 | |||

| c.256G>C, p.Asp86His | Fattori 2018 | |||

| c.281delC, p.Ser94LeufsTer6 | Fattori 2018 | |||

| KLHL40 | 10 | Binding partner of E3 ligase cullin 3 | c.604delG, p.Ala202Argfs*56 | Natera-de Benito 2016 |

| c.1405G>T, p.Gly469Cys | Kawase 2015 | |||

| c.1516A>C p.Thr506Pro | Yeung 2020 | |||

| c.1327G>A, p.Gly433Ser | Yeung 2020 | |||

| c.1498C>T, p.Arg500Cys | Seferian 2016 | |||

| c.1513G>C, p.Ala505Pro | Natera-de Benito 2016 | |||

| chr3:42727712G>A, p.Trp201Ter | Avasthi 2019 | |||

| LMOD3 | 5 | Actin nucleator | c.366delG, p.Lys122AsnFs*6 | Marguet 2020 |

| c.882dupA, p.Asp295Argfs*2 | Michael 2018 | |||

| c.1069G>T, p.Glu357* | Michael 2018 | |||

| c.1628G>T, p.Arg543Leu | Marguet 2020 | |||

| p.Glu121ArgfsTer5 | Berkenstadt 2018 | |||

| p.L245del | Berkenstadt 2018 | |||

| MYO18B | 2 | Unconventional myosin, function not well characterized | c.6496G>T; p.Glu2166* | Malfatti 2015 |

| NEB1 | 24 | Structural component of sarcomere, binds actin | c.300dup, p.Tyr101fs*5 int49 | Malfatti 2014 |

| c.3458 + 1G>A | Kapoor 2012 | |||

| c.1825dup, p.Pro541Profs*2 | Lehtokari 2011 | |||

| c.2414 + 5G>A | Lehtokari 2011 | |||

| c.5060G > A, p.W1687X | Kiiski 2015 | |||

| c.5343 + 5G>A, p.Arg1747_Thr1778del | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.5574C > G, p.Tyr1858Stop | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.6496-G > A, p.2166_2234del | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.7432 + 1916_7535 + 372del, p.Arg2478_ Asp2512del | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.11086A>C, p.Thr3696Pro | Moureau-Le Lan 2018 | |||

| c.13066delT, p.Tyr4356Thrfs*8 ex110 | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.17535G > A, p.Glu5845Glu | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.17779_17780delTA, p.Tyr5927HisfsX17 | Moureau-Le Lan 2018 | |||

| c.18676C>T, p.Gln6226* | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.19101 + 5G > A, p.Leu6333_Glu6367del | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.20928G>T; p.Gly6976Gly | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.21076CC>T, p.Arg7026Ter | Moureau-Le Lan 2018 | |||

| c.21796_21810delinsT, p.Pro7266fs*30 | Moureau-Le Lan 2018 | |||

| c.22273del, p.Val7425Serfs49* | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.22591–3C>G, p.7531Val_ Ser7564del | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.2310 + 5G>A, c.17779_17780delTA, p.His738_Asp770del | Moureau-Le Lan 2018 | |||

| c.23420_23421del, p.Arg7807Serfs*16 | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.24250_24253dupGTCA, p.T8085fsX8100 | Gajda 2015 | |||

| c.24269del, p.Arg8090fs*54 | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.24372_24375dupAAGA, p.Val8126fs | Scoto 2013 | |||

| c.24440_24441insGTCA, p.Pro8148Serfs*15 | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.24527_24528delCT, p.P8176fsX8179 | Gajda 2015 | |||

| c.24579G>A, p.Ser8193Ser ex119 | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.24686_ 24687del, p.Glu8229Glufs*18 | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.24735_ 24736del(AG), p.Arg8245fs*1 | Malfatti 2014 | |||

| c.163689G>T, GAG>UGA | Kapoor 2012 | |||

| hg19 chr1:g.(154,156,325_154,156,028) _(154,173,059_154,177,712) | Kiiski 2015 | |||

| RYR1 | 2 | Intracellular calcium channels at the sarcoplasmic reticulum | c.4455–4G>A c.4718C>T, p.Pro1573Leu c.7585G>A, p.Asp2529Asn |

Tiberi 2020

Kondo 2012 Kondo 2012 |

| TNNT1 | 15 | Muscle contraction regulator | c.309 + 1G>A | van der Pol 2014 |

| c.323C>G, p.Ser108X | Marra 2015 | |||

| c.574_577delinsTAGTGCTGT | Abdulhaq 2015 | |||

| c.661G>T, p.Glu221X | D’Amico 2019 | |||

| arr[GRCh37] 19q13.42(55652193_55663445)x0 | Streff 2019 | |||

| TPM2 | 2 | Muscle contraction regulator | c.415_417delGAG, p.E139del | Citirak 2014 |

| Unknown | 13 |

NM symptoms may present at any point during fetal development to adulthood. Typically, NM presents similarly to other congenital myopathies: hypotonia, muscle weakness, and decreased or absent myostatic stretch reflexes. Defects are observed in the musculoskeletal system, such as fractures, kyphoscoliosis, joint contractures, skull enlargement, pectum excavatum, and pes planus. Creatine kinase levels are normal, although this is also the case in other myopathies. Many patients are born with characteristic myopathic facies affecting mainly the mouth, resulting in a high-arched palate and drooling; occasionally patients present with ophthalmoplegia, which is rarely seen in other musculoskeletal conditions. Complications in the respiratory system are common.22 In rare cases, cardiac and renal systems may also be affected secondary to the musculoskeletal defects.23–25 The differential diagnosis for patients with severe hypotonia and bulbar weakness is broad, but at birth includes myotonic dystrophy type 1, congenital myasthenic syndromes, spinal muscular atrophy type 0/1, mitochondrial myopathies, and Pompe disease.26,27

The goal of this systematic review was to synthesize latest published findings in pediatric patients with NM as an initial step toward describing genotype-phenotype descriptions. Our examination of case reports published between 2010 and 2020 details novel genetic findings, newly described clinical presentations, and clinical considerations for the care of pediatric NM patients.

Methods

A systematic search of Pubmed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Scopus was performed using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.28 The search strategy used the keywords (pediatric* OR child*) AND (NM OR nemaline rod OR rod myopathy). This protocol was not registered. Included case series or studies were published between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020; originally published in English; had pediatric patients (<21 years old); and focused on NM as the main topic. The time period selected limited our search to publications with the most recent peer-reviewed findings on pediatric NM. Reviews, meta-analyses, book chapters, and abstracts were excluded. Selected references were exported to Sciwheel, at which point all duplicates were removed.29 Titles were read for concordance with inclusion criteria as a screen, after which abstracts were read to select for eligible articles. Full text of all eligible articles was read, and any that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria were removed from consideration. These full-text articles fulfilled the CARE guidelines for case reports.30 Data were extracted and tabulated about age of first signs, earliest presenting neuromuscular signs and symptoms, accompanying body systems affected, progression, death, pathologic description, genetic changes, and consanguinity. These data were synthesized with attention to the recommendations of “Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports.”31 Extracted data are available on request.

Results

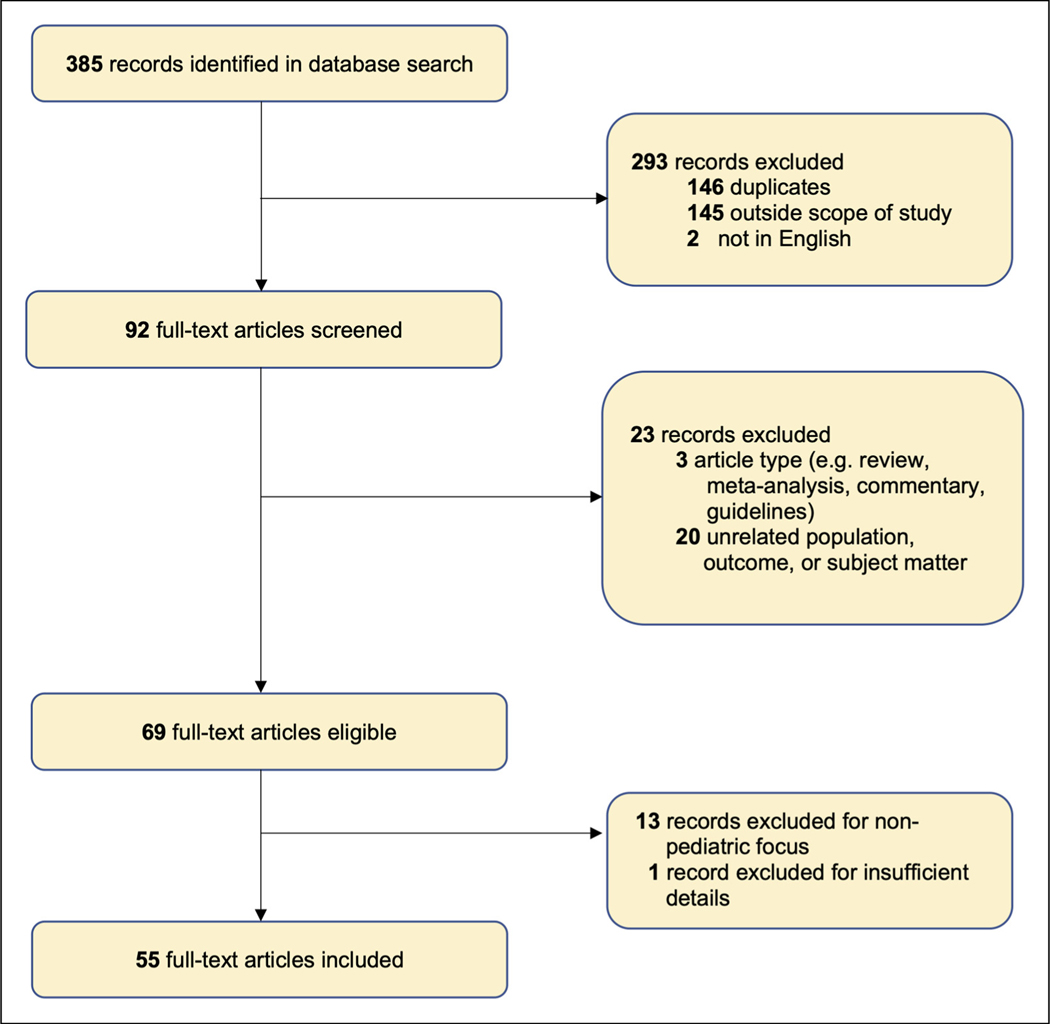

The database search yielded a total of 385 records (Figure 3). Of the 69 eligible articles, 55 case reports or series of 101 pediatric patients from 23 countries were selected for this review (Supplementary Material). By genetic mutation, reports implicated ACTA1, KLHL40, NEB, and TNNT1, in addition to other genes with a minor contribution (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Study selection process using PRISMA flow diagram.

Genetics

Improved clinical availability of next-generation sequencing has increased identification of novel mutations associated with pediatric NM, especially exome sequencing.32 The 88 cases covered by this review with available genetic information implicate several variants as causative of NM: 24% deletions and 6% duplications. These resulted in 25% missense mutations and 9% frameshift mutations. These changes were predicted to cause protein truncations in 19% of the cases. NM mutations were found to be de novo in 11% of cases. Further examination of the sequencing data revealed that 30% of the patients were heterozygous for the mutated gene, 23% were homozygous, and 7% were compound heterozygous.

NEB and ACTA1 have been identified as the most commonly mutated genes in NM. Of the pediatric cases examined for this review, 25% had mutations in NEB whereas 22% in ACTA1. Consistent with previous literature, many of the NEB mutations were frameshifts and present in compound heterozygous combinations.33 Fifty percent of the ACTA1 mutations were missense, and 45% were reported as de novo in the proband. For 2 patients, the ACTA1 mutations were predicted to produce a truncated protein or affect the binding site for actin’s interactors. Three cases with ACTA1 mutations had parents with gonadal mosaicism, which had not been previously reported, whereas one case showed somatic mosaicism.34–36 Identifying mosaic mutations required additional in-depth sequencing because of being very-low-grade.

New mutations were found in less common causative genes, such as CFL2, KLHL40, RYR, TNNT1, and TPM3 (Table 1). New variants in TNNT1 were documented in non-Amish populations.37–39 van der Pol et al predict that the combination of splice site mutations and a deletion in TNNT1 would produce short in-frame transcripts that would be targeted by nonsense-mediated decay.39 One family harbored a novel 4-basepair deletion in CFL2 likely causing a premature stop codon in the protein.40 Three patients from 2 unrelated families described by Fattori et al had mutations that may cause misfolding, lack of actin-binding, and protein degradation of cofilin 2.40,41 In southern China, researchers identified a KLHL40 founder mutation that inherited both homozygous and heterozygous, which often leads to a truncation of the protein.42 Several new mutations in tropomyosin genes, including TPM3, have also been identified.43,44 RYR mutations have been associated with various myopathies, but rarely with NM. Massively parallel sequencing in one patient in this review brought to light a new mutation in RYR1, causing NM with ophthalmoplegia.45

Histopathologic Features

Pathology information was available for 64% of the patients reviewed (Table 2). Of these, 75% confirmed presence of cytoplasmic nemaline rods or bodies. Curiously, one case report about a patient with an LMOD3 mutation noted that the rods were surrounded by a filamentous halo.46 Eight percent of patients had intranuclear rods; 4 of the 5 patients with intranuclear rods had a confirmed mutation in ACTA1, with the fifth not having any information about genetic causes. Internalized nuclei (found in 9%) were seen in patients with different mutated genes, including ACTA1, CFL2, and TNNT1.38,41,44,47

Table 2.

Main Clinicopathologic Features Reported.

| n (%) | Associated genes | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at first reported signs | ||

| Fetal | 31 (31) | ACTA1, KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT3, TNNT1 |

| Birth | 38 (38) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, MYO18B, NEB1, TNNT1, TPM2 |

| Infancy (<1 y) | 13 (13) | CFL2, LMOD3, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| 1–13 y | 13 (13) | ACTA1, CFL2, NEB |

| Early signs | ||

| Decreased fetal movements | 9 (9) | ACTA1, KLHL40 |

| Locked-in state | 1 (1) | KLHL40 |

| Polyhydramnios | 14 (14) | ACTA1, KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, RYR1 |

| Neonatal hypotonia | 64 (64) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, MYO18B, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1, TNNT3 |

| Delayed motor development | 29 (29) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1, TPM2 |

| Abnormal gait/frequent falls | 10 (10) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, TPM2 |

| Muscle weakness | ||

| Unspecified | 22 (22) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| Axial and proximal | 31 (31) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, MYO18B, NEB1, TNNT1, TNNT3, TPM2 |

| Distal | 23 (23) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, MYO18B, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| Tremor | 7 (7) | TNNT1 |

| Feeding difficulty | 16 (16) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, MYO18B, NEB1, TNNT3 |

| Early respiratory difficulty | 36 (36) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, RYR1 |

| Spinal curvature | 37 (37) | ACTA1, CFL2, LMOD3, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1, TNNT3 |

| Scoliosis | 15 (15) | ACTA1, CFL2, LMOD3, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1, TNNT3 |

| Kyphosis | 11 (11) | ACTA1, CFL2, LMOD3, TNNT1 |

| Rigid spine | 5 (5) | ACTA1, LMOD3, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| Lordosis | 5 (5) | ACTA1, CFL2, LMOD3, NEB1 |

| Facial involvement | 55 (55) | |

| Facial weakness | 29 (53) | ACTA1, CFL2, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT3, TPM2 |

| Ptosis | 6 (11) | KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, TPM2 |

| Ophthalmoplegia | 1 (2) | RYR1 |

| Facial dysmorphias | 29 (53) | |

| High-arched palate | 23 (42) | ACTA1, CFL2, LMOD3, MYO18B, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1, TNNT3, TPM2 |

| Micrognathia | 4 (7) | ACTA1, NEB1 |

| Cleft palate/lip | 2 (4) | KLHL40 |

| Myopathic facies | 9 (16) | ACTA1, KLHL40, LMOD3, TNNT1 |

| Elongated face | 7 (13) | ACTA1, NEB, RYR1 |

| Macrocephaly | 2 (4) | NEB |

| Dysmorphic features | 3 (5) | NEB |

| Thoracic deformities | ||

| Pectus excavatum | 2 (2) | ACTA1, MYO18B |

| Pectus carinatum | 5 (5) | TNNT1 |

| Respiratory | 57 (56) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, MYO18B, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1 |

| Tracheotomy | 15 (27) | ACTA1, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 30 (54) | ACTA1, LMOD3, NEB1, TNNT1, RYR1 |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 6 (11) | ACTA1, CFL2, NEB1 |

| Sleep apnea | 2 (4) | NEB1 |

| Pleural effusion, chylothorax | 3 (5) | ACTA1, KLHL40 |

| Cardiac | 13 (13) | |

| Hypertrophy | 2 (15) | MYO18B |

| Ventricular dilatation | 4 (31) | ACTA1, MYO18B, TNNT1 |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | 2 (15) | NEB1 |

| Atrioseptal defect | 2 (15) | LMOD3 |

| Cardiomegaly | 1 (8) | |

| Bradycardia | 1 (8) | RYR1 |

| Transient supraventricular tachycardia | 1 (8) | MYO18B |

| Joints/skeletal | 39 (39) | |

| Contractures | 21 (54) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, RYR1, TNNT1 |

| Arthrogryposis | 10 (26) | ACTA1, LMOD3, NEB1 |

| Club feet | 7 (18) | KLHL40, LMOD3, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| Fractures | 3 (8) | KLHL40 |

| Hip hyperlaxity | 3 (8) | KLHL40, NEB1, TNNT3 |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 3 (3) | ACTA1, TNNT1 |

| Neurologic | ||

| Intellectual disability | 1 (1) | NEB1 |

| Decreased white matter | 3 (3) | ACTA1 |

| Wheelchair bound | 7 (7) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40, NEB1 |

| Death | 36 (36) | |

| 0–1 mo | 5 (14) | ACTA1, NEB1 |

| 1–6 mo | 12 (33) | ACTA1, KLHL40, LMOD3, MYO18B, NEB1, RYR1 |

| 6 mo-1 y | 3 (8) | ACTA1, KLHL40, NEB1, TNNT3, |

| 1–5 y | 7 (19) | KLHL40, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| 5–10 y | 5 (14) | ACTA1, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| >10 y | 5 (14) | NEB1, TNNT1 |

| Cause of death | ||

| Sepsis | 3 (8) | ACTA1, KLHL40, MYO18B |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 3 (8) | ACTA1, TNNT3 |

| Cardiopulmonary arrest | 3 (8) | ACTA1, KLHL40, RYR1 |

| Infection | 2 (6) | KLHL40, LMOD3, |

| Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury | 1 (3) | |

| Terminated pregnancy | 4 (4) | KLHL40, LMOD3 |

| Pathology features | 65 (64) | |

| Cytoplasmic nemaline rods | 49 (75) | |

| Intranuclear rods | 5 (8) | ACTA1 |

| Fiber size variation | 26 (40) | ACTA1, CFL2, LMOD3, MYO18B, NEB1, TNNT1 |

| Internalized nuclei | 6 (9) | ACTA1, CFL2, MYO18B, TNNT1 |

| Increased fibrous connective tissue | 18 (28) | ACTA1, CFL2, TNNT1, TNNT3 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration | 3 (5) | ACTA1, TNNT1 |

| Atrophic fibers | 8 (12) | ACTA1, MYO18B, TNNT3 |

| Fingerprint bodies | 1 (2) | LMOD3 |

| Rods surrounded by halos | 1 (2) | LMOD3 |

| Mitochondrial aggregates | 1 (2) | NEB1 |

| Myofibrillar degradation | 3 (5) | ACTA1, CFL2, KLHL40 |

Other common features included fiber size variation (40%) and increased endomysial fibrous connective tissue (28%). Five percent of cases described some form of inflammatory cell infiltration. One study found that 2 patients had necrotic muscle fibers with T cells that stained positive for CD4 and negative to CD8.48 Atrophic fibers were found in 12% of patients with no correlation to age of first symptoms or death at the time of case report. Detailed analysis of patients with NEB mutations categorized them into 3 groups by time of symptom onset, which correlated with differences on histology such as differences in the amount of sarcomeric dissociation, rod pattern, and fiber type.49

Spectrum of Disease

The selected case reports described a variety of clinical presentations, some with symptoms in organ systems beyond the typical muscle weakness of NM (Table 2). The first reported signs often came as early as fetal development for 9% of cases, with a decrease in fetal movements or polyhydramnios on antenatal ultrasonography, typically during the second or third trimesters. The most common early sign of disease was neonatal hypotonia, seen in 64% of children, followed by early respiratory difficulty (36%) and spinal curvature (37%). More than half of patients had respiratory complications throughout childhood, including respiratory failure as evidenced by placement of tracheostomy. Mutations in MYO18B, TNNT1, and ACTA1 were seen in some cases that involved cardiomyopathy.17,50–52 One patient presented early with left-sided hypertrophy causing pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dilatation.17 Dilated cardiomyopathy was identified in 2 patients with ACTA1 mutations; this was paired with dyskinesia of the left ventricle in one child.34,51

Muscle weakness presented differently across patients. Pattern of weakness was axial and proximal in 31% of cases, whereas distal involvement was reported for 23%. Facial weakness was noted for just under one-third of children, although a broad spectrum of facial dysmorphic patterns was described. Some patients are born with significant craniofacial deformities, including cleft lip, atrophy of facial and masticator muscles, and jaw deformity, which can impact the patient’s ability to close their mouth.53 Joint contractures and arthrogryposis were common, described in almost 40% of patients. Another possible presenting symptom is hyperextension of the neck, for which Tiberi et al recommend neurologic examination after birth to check for possible muscle disorder such as NM.54 One patient with decreased movement in utero was found to have very fragile ribs on postnatal chest radiograph.26

The majority of patients exhibiting early lethality (36% of patients were deceased) were diseased within the first year of life; causes of death included sepsis, respiratory insufficiency, cardiopulmonary arrest, infection, or hypoxic-ischemic brain injury.

Patients with NM typically have normal intelligence, but Saito et al documented patients with ACTA1 dominant missense mutations with delays on word comprehension testing that “may result from abnormal development of the central nervous system, not only from hypoxic events or limited social experiences.”55 All 3 patients had decreased white matter volume, enlargement of the lateral ventricles, and frontal lobe hypoplasia.

Clinical severity varied significantly, even among patients with mutations in the same gene. Some with ACTA1 mutations were reported to have mild phenotypes, whereas one patient had dysautonomia in addition to myopathic symptoms.56–58 Anticipation was seen in a family harboring an ACTA1 missense mutation, where the mother had some weakness while her child had myopathic facies, high-arched palate, lumbar hyperlordosis, and delayed motor milestones.59 One child with an ACTA1 mutation of Thai ancestry had primary pulmonary lymphangiectasia on histology, in addition to pleural adhesions and a choroid plexus papilloma causing communicating hydrocephalus.47 For KLHL40 mutations, some patients had moderate presentation whereas others experienced fetal akinesia or a total locked-in state because of the severity of their disease.60–62 LMOD3 mutations also could present prenatally as decreased fetal movements, polyhydramnios, and arthrogryposis, or later in childhood, with a milder phenotype or even disease progression.12,46,63 Mutations in TNNT1 were reported in patients of varied ethnic backgrounds, including a case series of Amish patients presenting with the prototypical progressive muscle weakness, contractures, and tremors; of Italian siblings with severe failure to thrive and rigid spine; and of a Palestinian cohort that showed signs of transient tremors, progressive spinal rigidity, and limb contractures.64–66

Clinical Care Considerations

Care for patients with NM should follow standard multidisciplinary supportive care as reviewed in the Consensus Statement on Standard of Care for Congenital Myopathies.67 Biopsy is critical to the diagnosis of NM; however, selection of the biopsy location may introduce sampling error. A potential advance was discussed by one paper that showed the potential of using imaging—magnetic resonance imaging, in particular—to guide the decision of what muscle to biopsy.27 Better understanding of the genetic underpinnings of NM may allow for making the diagnosis of NM without the need for biopsy.32

NM patients require multifaceted care that addresses specific needs and prevention involving wide expertise from specialists and health care professions. The varied presentations of NM in some patients in this review bring to light several considerations for clinical practice.

Respiratory function is commonly affected in NM patients, as 36% of the patients described had early respiratory difficulty and 56% had neuromuscular respiratory failure or weakness. Some patients experienced recurrent respiratory infection, which is cause for concern given that respiratory insufficiency, cardiopulmonary arrest, infection, and sepsis were the majority of the reported causes of death across case reports. NM patients may also experience complications postprocedure such as pleurodesis, where pneumothorax can be treated using biphasic cuirass ventilation.68 Monitoring sleep and pulmonary function over time is important to assess for nocturnal hypoventilation, obstructive sleep apnea, and restrictive lung disease. One patient underwent inspiratory muscle strength training for 2 weeks after major surgery. This short-term intervention increased her mean inspiratory pressure and allowed her to breathe unassisted for 11–13 hoursper day, compared with her medical historyof restrictive lung disease and recurrent ventilatory failure postoperation.69

NM has variable impacts on the motor function of each patient and, therefore, care involves a combination of orthopedic, physical therapy, occupational/speech therapy, and neuropharmacologic agents. Speech therapy involving oral motor exercises, tongue strengthening exercises, and diadochokinesia exercises were used by one study team to help a patient with severe dysarthria improve the intelligibility of her speech.70 Two case reports present rare instances where there is a role for neuropharmacologic agents in improving the life of patients with NM. The report by Sahin et al documented decreased drooling and spontaneous extremity movement from a child that was previously immobile after treatment with L-tyrosine.71 For a child with a KLHL40 mutation presenting with myasthenic symptoms without antibodies directed against the acetylcholine receptor, use of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor pyridostigmine greatly improved endurance and strength, which regressed when the medication was no longer administered.72

Given that the histologic appearance of NM resembles that of core-rod myopathy, it is recommended that anesthesia be approached with caution in NM patients so as to mitigate any theoretical risk for malignant hyperthermia particularly if a mutation in RYR1 is present.73 In a case of cleft palate repair, the team was able to avoid the use of succinylcholine by using propofol and fentanyl for induction, intubation, and adjustment of IV access, with rocuronium for facial muscle relaxation.74 Intubation itself can pose challenges because of the facial dysmorphias of some patients.75

For children, follow-up care should occur at regular intervals, which should be more frequent (3–4 months) for infants as opposed to older children (6–12 months). The majority of the deceased patients reviewed passed away during the first year of life, suggesting that the timing of visits for children with early-onset NM symptoms may need to occur more frequently.

Discussion

NM is a myopathy that can range from severe to mild with weakness manifesting at birth. Defects of sarcomere components or its regulators result in actin aggregates within the muscle, seen easily on electron microscopy of muscle biopsy. Several important knowledge gaps remain, including how the disease affects children across all ages. The articles surveyed in this review deepen the understanding of pediatric NM patients and provide clues that may aid in identifying subtle cases after careful evaluation.

The continued improvement in sequencing and its increased accessibility makes the possibility of identifying causative genes more feasible, including for those that produce larger proteins such as nebulin. Sequencing results confirm the heterogeneity of genes that cause NM, and several new variants were identified in pediatric NM patients, which expand our understanding of how it is inherited. The majority of patients reviewed had mutations in NEB and ACTA1 as has been previously reported. New examples of gonadal mosaicism leading to inheritance were identified in ACTA1 patients by using more sophisticated sequencing modalities. Patients from non-Amish populations were found to harbor TNNT1 mutations different from the Amish founder mutation, which resulted in a different phenotypic picture with failure to thrive and spinal rigidity rather than only progressive muscle weakness, contractures, and tremors. Many of the case reports implicated nonsense-mediated decay as the mechanism by which translation of faulty transcript of NM genes is reduced, in particular for recessive form of the disease.

Increased information about causative genes and mutations provides the opportunity to incorporate genetics into the diagnostic process. Looking forward, as the genetic profile of NM further develops, it may be possible to shift away from a reliance on muscle biopsy given that this procedure is invasive and can cause discomfort for a child. However, much remains to be discovered since there are cases where a mutated gene has not yet been identified.26,48,52,53,58,68,69,70,71 Sequencing is not as accessible across the globe and may pose financial hardship in some cases; thus, it is unlikely to become the sole source of diagnostic information in the near future.

The cases described not only the expected presence of nemaline rods on histology but also details about fiber size variation, filaments surrounding the rods, and inflammatory cell infiltration. These subtleties require further study to identify if these findings correlate with genotype or clinical severity.

The clinical features presented mirror many of the existing descriptions of NM, yet they highlight additional opportunities for clinical intervention to improve the lives of NM patients. A number of cases listed decreased fetal movements or antenatal ultrasonographic findings such as polyhydramnios as early signs; although not specific enough to be diagnostic, these may serve to document the need for a neuromuscular examination at birth. Subtle findings at birth such as hyperextension of the neck should also lead the clinician to consider a more thorough neurologic examination.54 Given that early respiratory difficulty was cited in more than one-third of patients, more needs to be done to identify ways to provide respiratory support for neonates with suspected NM with special attention to the various craniofacial deformities found in some patients. Respiratory health is critical, considering the number of patients described as experiencing recurrent infection and dying from pulmonary complications particularly in the first year of life.

Little was mentioned about management of spinal curvature despite almost 40% of patients experiencing this complication. Among these cases, there were examples of both dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in patients with mutations in ACTA1, TNNT1, and MYO18B. Cardiomyopathy had been reported in ACTA1 and Amish TNNT1 patients previously; however, this report of a pediatric patient with a mutation MYO18B was one of the first that showed an association with hypertrophy.17 The case of MYO18B also highlight that cardiac phenotypes seen in model organisms may serve to identify genes that may later be found to be important in skeletal muscle and be linked to NM pathology. The article by Saito et al55 introduces the point that normal intelligence may not be common to all patients with NM and therefore emphasizes the need for more detailed analysis of the pediatric brain. Lastly, these cases collectively underscore how presentation is not consistent across patients with mutations in the same gene; future studies examining patients with different mutations in the same gene should carefully track the precise symptoms that may distinguish severity.

To compile the most recent clinical reports of NM, this review is limited by the findings shared in the literature. Therefore, the trends identified in the results are based on the information explicitly described in the case reports, which varied in their detail (Table 2). The lack of histologic or genetic results for some patients reduces the correlations that can be made between genotype and phenotype. Studies that include a large cohort of patients with NM with different genetic mutations are needed to identify such patterns, especially if sequencing and testing are done in a comparable manner. These studies will allow for more robust correlation between genotype and phenotype that may be useful in predicting prognosis.

Greater interplay between clinical and basic science findings will be critical in developing clinical prevention and treatment strategies. Future studies may consider tests, procedures, and treatments for NM. For example, further study should examine the value of imaging, as suggested by Ennis et al.27 The value of L-tyrosine as treatment should also be considered, although there have been mixed results in human and animal studies. Ryan et al describe improvement in bulbar function, activity level, and exercise tolerance in 4 patients who received L-tyrosine supplementation; however, the underlying genetic change was identified in only 1 patient in TPM3.76 A study in mice with a mutation in ACTA1 showed similar improvements in mobility in addition to showing a decrease in rods and degenerating fibers on muscle biopsy.77 However, work in zebrafish models of nebulin NM have not shown these changes after administration of L-tyrosine or other supplements.78 These findings are similar to a study using 2 established mouse models and one zebrafish model with ACTA1 mutations.79 Continued genetic studies are needed to characterize the responsible genes that cause other forms of NM. More reports sharing best practices in improving quality of life for NM patients would benefit the field, particularly related to respiratory and orthopedic care that would benefit many of the patients reviewed.

Overall, this review demonstrates the progress that has been, and is yet to be, made in the diagnosis and mechanistic understanding of NM in children. More research, particularly into the importance of sarcomeric structures and regulatory proteins in maintaining healthy muscle, will be needed. These concepts will be critical to establishing best practices and standards for diagnosis and treatment in pediatric NM.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, A Foundation Building Strength (grant number NIAMS R56AR077017 [VAG], NIGMS R35GM1411877 [MB], NIGMS T32GM007739 [BC], P30 CA008748 [Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, VAG]).

Footnotes

Ethical Approval

Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Wallgren-Pettersson C. Congenital Nemaline Myopathy: A Longitudinal Study. Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conen PE, Murphy EG, Donohue WL. Light and electron microscopic studies of “myogranules” in a child with hypotonia and muscle weakness. Can Med Assoc J. 1963;89:983–986. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shy GM, Engel WK, Somers JE, Wanko T. Nemaline myopathy. A new congenital myopathy. Brain. 1963;86:793–810. doi: 10.1093/brain/86.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nance JR, Dowling JJ, Gibbs EM, Bönnemann CG. Congenital myopathies: an update. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12-(2):165–174. doi: 10.1007/s11910-012-0255-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallgren-Pettersson C, Jasani B, Newman GR, et al. Alpha-actinin in nemaline bodies in congenital nemaline myopathy: immunological confirmation by light and electron microscopy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1995;5(2):93–104. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(94)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domazetovska A, Ilkovski B, Cooper ST, et al. Mechanisms underlying intranuclear rod formation. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 12):3275–3284. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpe P, Damiani E, Margreth A, Pellegrini G, Scarlato G. Fast to slow change of myosin in nemaline myopathy: electrophoretic and immunologic evidence. Neurology. 1982;32(1):37–41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miike T, Ohtani Y, Tamari H, Ishitsu T, Une Y. Muscle fiber type transformation in nemaline myopathy and congenital fiber type disproportion. Brain Dev. 1986;8(5):526–532. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(86)80098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malfatti E, Romero NB. Nemaline myopathies: state of the art. Rev Neurol. 2016;172(10):614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schröder JM, Durling H, Laing N. Actin myopathy with nemaline bodies, intranuclear rods, and a heterozygous mutation in ACTA1 (Asp154Asn). Acta Neuropathol. 2004;108(3):250–256. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal PB, Greenleaf RS, Tomczak KK, et al. Nemaline myopathy with minicores caused by mutation of the CFL2 gene encoding the skeletal muscle actin-binding protein, cofilin-2. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(1):162–167. doi: 10.1086/510402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkenstadt M, Pode-Shakked B, Barel O, et al. LMOD3-associatednemaline myopathy: prenatal ultrasonographic, pathologic, and molecular findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(7):1827–1833. doi: 10.1002/jum.14520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelin K, Ridanpää M, Donner K, et al. Refined localisation of the genes for nebulin and titin on chromosome 2q allows the assignment of nebulin as a candidate gene for autosomal recessive nemaline myopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5(4):229–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallgren-Pettersson C, Donner K, Sewry C, et al. Mutations in the nebulin gene can cause severe congenital nemaline myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(7–8):674–679. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambuughin N, Yau KS, Olivé M, et al. Dominant mutations inKBTBD13, a member of the BTB/Kelch family, cause nemaline myopathy with cores. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(6):842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravenscroft G, Miyatake S, Lehtokari V-L, et al. Mutations in KLHL40 are a frequent cause of severe autosomal-recessive nemaline myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(1):6–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malfatti E, Böhm J, Lacène E, Beuvin M, Romero NB, Laporte J.A premature stop codon in MYO18B is associated with severe nemaline myopathy with cardiomyopathy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2015;2(3):219–227. doi: 10.3233/JND-150085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von der Hagen M, Kress W, Hahn G, et al. Novel RYR1 missense mutation causes core rod myopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(4): e31–e32. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston JJ, Kelley RI, Crawford TO, et al. A novel nemaline myopathy in the Amish caused by a mutation in troponin T1. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(4):814–821. doi: 10.1086/303089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gommans IMP, Davis M, Saar K, et al. A locus on chromosome15q for a dominantly inherited nemaline myopathy with core-like lesions. Brain. 2003;126(pt 7):1545–1551. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin JJ-C, Eppinga RD, Warren KS, McCrae KR. Human tropomyosin isoforms in the regulation of cytoskeleton functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;644:201–222. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85766-4_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arai A, Mitsuhashi S, Saito Y, et al. Nemaline (actin) myopathywith myofibrillar dysgenesis and abnormal ossification. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19(7):485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.06.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakajima M, Shima Y, Kumasaka S, Kuwabara K, Migita M, Fukunaga Y. An infant with congenital nemaline myopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Nippon Med Sch. 2008;75-(6):350–353. doi: 10.1272/jnms.75.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Amico A, Graziano C, Pacileo G, et al. Fatal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and nemaline myopathy associated with ACTA1 K336E mutation. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16(9–10):548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladha S, Coons S, Johnsen S, Sambuughin N, Bien-Wilner R, Sivakumar K. Histopathologic progression and a novel mutation in a child with nemaline myopathy. J Child Neurol. 2008;23-(7):813–817. doi: 10.1177/0883073808314363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelardi L. Hypotonia at birth: a case study of ACTA-1 mutation, acongenital myopathy. Neonatal Netw. 2018;37(4):212–217. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.37.4.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ennis J, Dyment DA, Michaud J, McMillan HJ. Congenital nemaline myopathy: the value of magnetic resonance imaging of muscle. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;42(5):338–340. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2015.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sciwheel Limited. Sciwheel. http://sciwheel.com. Published 2010. Accessed July 27, 2021.

- 30.Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, et al. CARE Guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23(2):60–63. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herman I, Lopez MA, Marafi D, et al. Clinical exome sequencing in the diagnosis of pediatric neuromuscular disease. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(3):304–310. doi: 10.1002/mus.27112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehtokari V-L, Kiiski K, Sandaradura SA, et al. Mutation update: the spectra of nebulin variants and associated myopathies. Hum Mutat. 2014;35(12):1418–1426. doi: 10.1002/humu.22693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyatake S, Koshimizu E, Hayashi YK, et al. Deep sequencing detects very-low-grade somatic mosaicism in the unaffected mother of siblings with nemaline myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24(7):642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seidahmed MZ, Salih MA, Abdelbasit OB, et al. Gonadal mosaicism for ACTA1 gene masquerading as autosomal recessive nemaline myopathy. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170(8):2219–2221. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokoi T, Sei K, Enomoto Y, Naruto T, Kurosawa K. Somatic mosaicism of a heterogeneous mutation of ACTA1 in nemaline myopathy. Pediatr Int. 2019;61(11):1169–1171. doi: 10.1111/ped.13962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandaradura SA, Bournazos A, Mallawaarachchi A, et al. Nemaline myopathy and distal arthrogryposis associated with an autosomal recessive TNNT3 splice variant. Hum Mutat. 2018;39-(3):383–388. doi: 10.1002/humu.23385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marra JD, Engelstad KE, Ankala A, et al. Identification of a novel nemaline myopathy-causing mutation in the troponin T1 (TNNT1) gene: a case outside of the old order Amish. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51(5):767–772. doi: 10.1002/mus.24528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Pol WL, Leijenaar JF, Spliet WGM, et al. Nemaline myopathy caused byTNNT1 mutations in a Dutch pedigree. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2014;2(2):134–137. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ong RW, AlSaman A, Selcen D, et al. Novel cofilin-2 (CFL2) four base pair deletion causing nemaline myopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1058–1060. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ockeloen CW, Gilhuis HJ, Pfundt R, et al. Congenital myopathy caused by a novel missense mutation in the CFL2 gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22(7):632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeung KS, Yu FNY, Fung CW, et al. The KLHL40 c.1516A>Cis a Chinese-specific founder mutation causing nemaline myopathy 8: report of six patients with pre- and postnatal phenotypes. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8(7):e1229. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Citirak G, Witting N, Duno M, Werlauff U, Petri H, Vissing J. Frequency and phenotype of patients carrying TPM2 and TPM3 gene mutations in a cohort of 94 patients with congenital myopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24(4):325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiiski K, Lehtokari VL, Manzur AY, et al. A large deletion affecting TPM3, causing severe nemaline myopathy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2015;2(4):433–438. doi: 10.3233/JND-150107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kondo E, Nishimura T, Kosho T, et al. Recessive RYR1 mutations in a patient with severe congenital nemaline myopathy with ophthalomoplegia identified through massively parallel sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(4):772–778. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michael E, Hedberg-Oldfors C, Wilmar P, Visuttijai K, Oldfors A, Darin N. Long-term follow-up and characteristic pathological findings in severe nemaline myopathy due to LMOD3 mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(2):108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.201812.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waisayarat J, Suriyonplengsaeng C, Khongkhatithum C, Rochanawutanon M. Severe congenital nemaline myopathy with primary pulmonary lymphangiectasia: unusual clinical presentation and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:27. doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-0270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang C, Wang J, Lu H. Clinical and pathological features of childhood-onset nemaline myopathy: a report of four cases. Case Report Med. 2012;2012:203602. doi: 10.1155/2012/203602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malfatti E, Lehtokari V-L, Böhm J, et al. Muscle histopathology in nebulin-related nemaline myopathy: ultrastrastructural findings correlated to disease severity and genotype. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:44. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Streff H, Bi W, Colón AG, Adesina AM, Miyake CY, Lalani SR. Amish nemaline myopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy caused by a homozygous contiguous gene deletion of TNNT1 and TNNI3 in a mennonite child. Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62(11):103567. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gatayama R, Ueno K, Nakamura H, et al. Nemaline myopathywith dilated cardiomyopathy in childhood. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1986–e1990. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mir A, Lemler M, Ramaciotti C, Blalock S, Ikemba C. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a neonate associated with nemaline myopathy. Congenit Heart Dis. 2012;7(4):E37–E41. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2011.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xue Y, Magoulas PL, Wirthlin JO, Buchanan EP. Craniofacial manifestations in severe nemaline myopathy. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(3):e258–e260. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tiberi E, Costa S, De Rose DU, et al. Expanding the spectrum of congenital myopathies: prenatal onset with extreme hyperextension of the neck. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(4):1549–15532020. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saito Y, Komaki H, Hattori A, et al. Extramuscular manifestations in children with severe congenital myopathy due to ACTA1 gene mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011;21(7):489–493. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levesque L, Del Bigio MR, Krawitz S, Mhanni AA. A de novo dominant mutation in ACTA1 causing congenital nemaline myopathy associated with a milder phenotype: expanding the spectrum of dominant ACTA1 mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2013;23-(3):239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang L, Yu P, Chen X, Cai T. The de novo missense mutationN117S in skeletal muscle α-actin 1 causes a mild form of congenital nemaline myopathy. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(2):1693–1696. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chou PC, Liang WC, Nonaka I, Mitsuhashi S, Nishino I, Jong YJ. Intranuclear rods myopathy with autonomic dysfunction. Brain Dev. 2013;35(7):686–689. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lehtokari VL, Gardberg M, Pelin K, Wallgren-Pettersson C. Clinically variable nemaline myopathy in a three-generation family caused by mutation of the skeletal muscle alpha-actin gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(4):323–326. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawase K, Nishino I, Sugimoto M, et al. Nemaline myopathy with KLHL40 mutation presenting as congenital totally locked-in state. Brain Dev. 2015;37(9):887–890. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Avasthi KK, Agarwal S, Panigrahi I. KLHL40 mutation associated with severe nemaline myopathy, fetal akinesia, and cleft palate. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2019;14(4):222–224. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_60_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seferian AM, Malfatti E, Bosson C, et al. Mild clinical presentation in KLHL40-related nemaline myopathy (NEM 8). Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26(10):712–716. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marguet F, Rendu J, Vanhulle C, et al. Association of fingerprint bodies with rods in a case with mutations in the LMOD3 gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2020;30(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.201912.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fox MD, Carson VJ, Feng H-Z, et al. TNNT1 Nemaline myopathy: natural history and therapeutic frontier. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(18):3272–3282. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.D’Amico A, Fattori F, Fiorillo C, et al. Severe nemaline myopathy manifesting as “Amish phenotype” related to homozygous mutation in TNNT1. Acta Myol. 2018;37(1):66. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abdulhaq UN, Daana M, Dor T, et al. Nemaline body myopathy caused by a novel mutation in troponin T1 (TNNT1). Muscle Nerve. 2016;53(4):564–569. doi: 10.1002/mus.24885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang CH, Dowling JJ, North K, et al. Consensus statement on standard of care for congenital myopathies. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(3):363–382. doi: 10.1177/0883073812436605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hino H, Suzuki Y, Ishii E, Fukuda M. Biphasic cuirass ventilation for treatment of an air leak after pneumothorax in a patient with nemaline myopathy: a case report. J Anesth. 2016;30(6):1087–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00540-016-2250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith BK, Bleiweis MS, Zauhar J, Martin AD. Inspiratory muscle training in a child with nemaline myopathy and organ transplantation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(2):e94–e98. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181dde680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cervera-Mérida JF, Villa-García I, Ygual-Fernández A. Speech treatment in nemaline myopathy: a single-subject experimental study. J Commun Disord. 2020;88(106051), doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.106051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sahin S, Oncel MY, Bidev D, Okur N, Talim B, Oguz SS. Nemaline rod myopathy treated with l-tyrosine to relieve symptoms in a neonate. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2019;117(4):E382–E385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benito D N-d, Nascimento A, Abicht A, et al. KLHL40-relatedNemaline myopathy with a sustained, positive response to treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. J Neurol. 2016;263-(3):517–523. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-8015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tran S. Anesthetic consideration for patients with nemaline rod myopathy: a literature review. Pediatr Anesth Crit Care J. 2017;5(1):31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tran NH, Chhibber A. Anesthetic management of a pediatric patient with NEB1-genotype nemaline rod myopathy for cleft palate repair. Pediatr Anesth Crit Care J. 2016;4(2):78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oliveira M, Fernandes AL, Vargas S. Using sevoflurane in a pediatric patient with nemaline rod myopathy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28(8):749–750. doi: 10.1111/pan.13458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ryan MM, Sy C, Rudge S, et al. Dietary l-tyrosine supplementation in nemaline myopathy. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(6):609–613. doi: 10.1177/0883073807309794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen M-AT, Joya JE, Kee AJ, et al. Hypertrophy and dietary tyrosine ameliorate the phenotypes of a mouse model of severe nemaline myopathy. Brain. 2011;134(pt 12):3516–3529. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sztal TE, McKaige EA, Williams C, Oorschot V, Ramm G, Bryson-Richardson RJ. Testing of therapies in a novel nebulin nemaline myopathy model demonstrate a lack of efficacy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0546-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Messineo AM, Gineste C, Sztal TE,et al.L-tyrosine supplementation does not ameliorate skeletal muscle dysfunction in zebrafish and mouse models of dominant skeletal muscle α-actin nemaline myopathy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11490. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]