Abstract

Objectives

To use serological testing to assess the pre-Omicron seroprevalence, seroconversion, and seroreversion of infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children and adolescents in Montréal, Canada.

Design

This analysis is from a prospective cohort study of children aged 2-17 years (at baseline) that included blood spots for antibody detection. The serostatus of participants was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using the receptor-binding domain from the spike protein and the nucleocapsid protein as antigens. We estimated seroprevalence, seroconversion rates, and the likelihood of seroreversion at 6 months and 1 year.

Results

The baseline (October 2020 to April 2021) seroprevalence was 5.8% (95% confidence interval [CI] 4.8-7.1), which increased to 10.5% (May to September 2021) and 11.0% (November 2021 to March 2022) for the respective follow-ups (95% CI 8.6-12.7; 95% CI 8.8-13.5). The crude rate of seroconversion over the study period was 12.8 per 100 person-years (95% CI 11.0-14.7). The adjusted hazard rates of seroconversion by child characteristics showed higher rates in children who were female, whose parent identified as a racial or ethnic minority, and in households with incomes in the lowest tercile of our study population. The likelihood of remaining seropositive at 6 months was 68% (95% CI 60-77%) and dropped to 42% (95% CI 32-56%) at 1 year.

Conclusion

Serological studies continue to provide valuable contributions for infection prevalence estimates and help us better understand the dynamics of antibody levels after infection.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Serology, Cohort, Pediatric, Seroconversion, Seroreversion

Introduction

With the emergence of highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants and the widespread use of at-home tests, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to challenge public health surveillance efforts and limit the precision in disease occurrence estimates. In the absence of reliable data on the rates of infection, seroprevalence studies remain important in estimating the prevalence of infected individuals, particularly among young and healthy populations who are more likely to experience mild or asymptomatic infection, although contributing to disease transmission.

Repeated serological testing allows the monitoring of antibody dynamics in populations, including seroconversion and seroreversion. Several studies have documented these dynamics after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a general agreement that seroconversion, the development of antibodies specific to the virus, typically occurs within 2-3 weeks after symptom onset [1,2]. Among seropositive individuals, the estimates of antibody waning are variable, with some suggesting that seroreversion occurs more rapidly among younger adults and those with mild or asymptomatic infections [3,4]. Few data are available on seroreversion in children; although, a few cohort studies have found that immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibodies waned (yet remained detectable) starting at 2 months up to at least 18 months after the infection, with higher antibody levels consistently observed among younger children [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Furthermore, there are few studies that have calculated the rates of seroconversion and seroreversion, which are important immunology measures that allow comparability at different points in time or among different study populations.

In this prospective school-based cohort study, we used serological testing to assess the prevalence, seroconversion, and seroreversion of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children and adolescents in Montréal, Canada. We also identified the characteristics of study participants associated with increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

Participants were initially recruited through selected day cares and schools in four different neighborhoods to reflect diversity in terms of geography, cumulative COVID-19 cases, and neighborhood socioeconomic status. The populations living in the West Island and Plateau-Mont-Royal are more affluent and highly educated, whereas Montréal North is one of the city's poorest and most racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods, and Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve (HOMA) is a working-class neighborhood with nearly one-third of the population living below the poverty line [10].

We obtained electronic informed consent from parents or legal guardians and assent from children and teenage participants. The study protocol was approved by the research ethics boards of the Université de Montréal and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine. The details of the full cohort study procedures are available in the study protocol [11]. This study followed the reporting requirements of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement [12].

Procedures

For each round of data collection, parents completed a questionnaire, which included questions on the household, the general health of their child, any SARS-CoV-2 tests taken, observed symptoms, and test results. The questions on household income and dwelling type were included after the baseline collection began. Once the questionnaires were complete, the participants were sent specimen collection kits for finger prick whole blood samples. The current analysis includes data from three rounds of data collection: October 2020 to April 2021 (round 1), May to September 2021 (round 2), and November 2021 to March 2022 (round 3).

Laboratory testing

The serostatus of participants was determined by a pair of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using the receptor-binding domain (RBD) from the spike protein and the nucleocapsid protein (N) as antigens. The precise laboratory protocols for the validation and implementation of the two assays are available in a supplement and in previous publications [11,13]. There were 59 seronegative samples that were initially identified as poor-quality samples but they were subsequently analysed because a better quality sample was not received from these participants.

Statistical analysis

Our original sample size calculation was based on neighborhood seroprevalence estimates and we required a sample size of 457 children per neighborhood (total of 1828 children), with a projected seroprevalence of 5% and a desired precision of 2% [14]. Age was grouped to correspond to the school level and vaccination age categories, i.e., 2-4, 5-11 and 12-17 years. Household income was dichotomized as the lowest tercile versus the upper two terciles. The overweight binary variable was based on the Centers of Disease Control body mass index percentile cut-off of 85% [15]. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.0.

Seroprevalence estimates

If a participant was positive for RBD, was unvaccinated, or received their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine within 9 days of their blood spots (DBSs) sample, they were classified as being infection-induced seropositive [16]. Participants who were both RBD- and N-positive were also classified as being infection-induced seropositive, regardless of the vaccination status. Those who were RBD-positive but N-negative at least 9 days from the date of their first vaccination, were classified as vaccine-induced seropositive but seronegative for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Participants negative for both RBD and N, regardless of the vaccination status, were classified as seronegative for SARS-CoV-2 infection. The unadjusted seroprevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated by univariate logistic regression with inverse probability of censoring weight correction (IPCW) to adjust for the potential selection bias from loss to follow-up. IPCW was implemented using the ipw package and the survey package in R.

Seroconversion estimates

Seroconversion rates were defined as the number of newly seropositive participants divided by the sum of participants’ time under observation while at risk of infection, i.e., the time to first seropositive test, time to first self-reported reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or antigen positive test, or time to last seronegative test for participants that remained uninfected for the duration of the follow-up. The adjusted hazard rates of seroconversion were estimated using pooled logistic regression to accommodate the nonproportional hazards [17]. Missing values were imputed using multivariate imputation by chained equations. The minimally sufficient adjustment sets for regressions were identified using directed acyclic graphs constructed in DAGitty Version 3.0 (for example, SFigure 1). When the children were found to be seropositive at baseline, in the absence of a self-reported positive RT-PCR or antigen test, the approximate time of seroconversion was less accurately measured than for the subsequent rounds of data collection. For this reason, a sensitivity analysis was conducted, where the sample included only children who were seronegative at baseline or seropositive with a self-reported positive RT-PCR or antigen date. These children were followed for up to two subsequent rounds of serology testing. A separate sensitivity analysis was carried out using records with complete data (complete case analysis).

Seroreversion estimates

Seroreversion was defined as a seronegative test in a child who was previously seropositive. The days to seroreversion was defined as the number of days between the first positive test and the first negative serology test. If a positive self-reported RT-PCR test or antigen test date was provided and occurred before the seropositive test date, this self-reported date was then used. The median time to seroreversion and the likelihood of remaining seropositive at 6 months and 1 year were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves. In the main analyses, children who were seropositive in any round of data collection were followed up to their first seronegative test or their last seropositive test if they never seroreverted. This required at least one serology test after seroconversion. If a child was vaccinated, they were censored at vaccination. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted (i) excluding children who were seropositive at baseline without a self-reported RT-PCR or antigen positive test result (without censoring at vaccination) and (ii) all seroconverted children followed up to their first seronegative or last seropositive result, without censoring at vaccination. The first sensitivity analysis was motivated by the lack in accuracy of the time of seroconversion for seropositive children identified at the baseline assessment. For the second, the classification into seronegative status after vaccination is complex so the main analyses censors vaccinated children at the time of vaccination; however, there is a loss in statistical precision as fewer seroreversions were observed. We assess the sensitivity of these results to include the follow-up time after vaccination, thereby gaining statistical precision at the potential cost of biasing the time to seroreversion.

Results

The pandemic context in Montréal during the study period is described in SFigure 2. There were 1812 children from 1373 households who initially enrolled in the study and completed the baseline questionnaire. Of these participants, 1632 (90%) provided a DBS sample that was of sufficient quality for the serological analysis; none of these children were vaccinated, 27 had previously tested positive by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and 95 were found to be seropositive. A total of 63 additional children were recruited from 45 households and provided DBS in subsequent rounds. Among the 936 DBS participants in round 2, 209 were vaccinated, 33 had previously tested positive by PCR/antigen, and 93 tested seropositive for an infection. Among the 723 DBS participants at round 3, 345 were vaccinated, 21 had previously tested positive by PCR, and 78 tested seropositive for a natural infection. Further breakdowns of the participants from each round are available in the supplement (SFigures 3-5). A total of 45% and 57% of the participants were lost to follow-up by the second and third rounds of data collection, respectively, but there was little evidence of differential loss to follow-up by participant and household characteristics, except for the greater losses for participants from the West Island neighborhood (STable 1 ). The age group distribution changed through rounds of data collection mainly due to children aged 2-4 years aging into the 5-11-year group.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics for each round of data collection.

| Round 1 n (%) | Round 2 n (%) | Round 3 n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1632 | 936 | 723 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 801 (49.1) | 449 (48.0) | 342 (47.3) |

| Male | 831 (50.9) | 487 (52.0) | 381 (52.7) |

| Age, years | |||

| 2-4 | 329 (20.2) | 151 (16.1) | 89 (12.3) |

| 5-11 | 727 (44.5) | 448 (47.9) | 346 (47.9) |

| 12-18 | 576 (35.3) | 337 (36.0) | 288 (39.8) |

| Body mass index | |||

| Underweight or normal weight | 1179 (72.2) | 687 (73.4) | 518 (71.6) |

| Overweight | 267 (16.4) | 135 (14.4) | 109 (15.1) |

| Missing | 186 (11.4) | 114 (12.2) | 96 (13.3) |

| Chronic medical conditions | |||

| None | 1517 (93.0) | 861 (92.0) | 663 (91.7) |

| Yes | 103 (6.3) | 69 (7.4) | 55 (7.6) |

| Missing | 12 (0.74) | 6 (0.64) | 5 (0.69) |

| Neighborhood | |||

| HOMA | 357 (21.9) | 218 (23.3) | 173 (23.9) |

| Montréal North | 237 (14.5) | 139 (14.9) | 121 (16.7) |

| Plateau | 534 (32.7) | 302 (32.3) | 243 (33.6) |

| West Island | 504 (30.9) | 277 (29.6) | 186 (25.7) |

| Parental respondent's level of education | |||

| No Bachelor's degree | 384 (23.5) | 184 (19.7) | 166 (23.0) |

| Bachelor's degree | 647 (39.6) | 380 (40.6) | 265 (36.7) |

| Graduate degree | 581 (35.6) | 362 (38.7) | 284 (39.3) |

| Missing | 20 (1.2) | 10 (1.1) | 8 (1.1) |

| Bedroom density | |||

| <1.5 persons per bedroom | 1103 (67.6) | 638 (68.2) | 469 (64.9) |

| 1.5+ persons per bedroom | 502 (30.8) | 287 (30.7) | 244 (33.7) |

| Missing | 27 (1.7) | 11 (1.2) | 10 (1.4) |

| Parental respondent's race and ethnicity | |||

| Racial or ethnic minority | 201 (12.3) | 110 (11.8) | 76 (10.5) |

| White | 1406 (86.2) | 815 (87.1) | 640 (88.5) |

| Missing | 25 (1.5) | 11 (1.2) | 7 (1.0) |

| Number of bedrooms | |||

| 1-2 bedrooms | 332 (20.3) | 185 (19.8) | 154 (21.3) |

| 3 bedrooms | 740 (45.3) | 417 (44.6) | 337 (46.6) |

| 4 bedrooms | 445 (27.3) | 267 (28.5) | 182 (25.2) |

| 5 bedrooms | 104 (6.4) | 61 (6.5) | 45 (6.2) |

| Missing | 11 (0.7) | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.7) |

| Dwelling type | |||

| Single family | 576 (35.3) | 452 (48.3) | 306 (42.3) |

| Other | 537 (32.9) | 425 (45.4) | 315 (43.6) |

| Missing | 519 (31.8) | 59 (6.3) | 102 (14.1) |

| Annual household income | |||

| < $100,000 CAD | 329 (20.2) | 270 (28.8) | 202 (27.9) |

| ≥ $100,000 CAD | 686 (42.0) | 585 (62.5) | 401 (55.5) |

| Missing | 617 (37.8) | 81 (8.7) | 120 (16.6) |

| Household member occupation | |||

| Not essential | 913 (55.9) | 522 (55.8) | 395 (54.6) |

| Essential, not health | 441 (27.0) | 242 (25.9) | 192 (26.6) |

| Essential, health | 267 (16.4) | 166 (17.7) | 131 (18.1) |

| Missing | 11 (0.7) | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.7) |

| Vaccinated at least 10 days before blood spots | 0 (0.0) | 209 (22.3) | 345 (47.7) |

At baseline or round 1 of data collection, the mean (SD) age of the children who provided a DBS sample was 9.6 (4.4) years and 801 (49%) were female, with 354 participants (22%) from day cares, 725 (44%) from primary schools, and 553 (34%) from secondary schools. Most parents had at least a bachelor's degree (1228 [75%]), and 201 (12%) self-identified as belonging to a racial or ethnic minority group (Table 1). On average, there were two adults and two children in 3-4-bedroom households. There were missing data values for household income for 9-38% of children (depending on the round of data collection) and dwelling type for 6-32% of children. Body mass index (height and/or weight) was missing or was an implausible value according to CDC charts, for 11-14% of children. The remaining variables had less than 2% missing values.

Seroprevalence estimates

Serology data were available for 1632, 936, and 723 children participating in the first, second, and third rounds of data collection, respectively (Table 1). The round 1 (October 2020 to March 2021) seroprevalence was 5.8% (95 of 1632, 95% CI 4.8-7.1) (Table 2 ). In rounds 2 and 3, the seroprevalence had nearly doubled to 10.5% and 11.0%, respectively (93 of 936, 95% CI 8.6-12.7; 78 of 723, 95% CI 8.8-13.5). The likelihood of seroprevalence was also significantly associated with neighborhood, with participants from the West Island having the lowest seroprevalence and Montréal North having the highest seroprevalence across all rounds. Though not consistently significant across all three rounds of data collection, the participants in the 5-11-year age group, those with parents identifying as a racial or ethnic minority, and those in homes with higher bedroom density and lower household income tended to have a higher seroprevalence. Participants living in single-family homes had significantly lower seroprevalence in all rounds of testing.

Table 2.

Unadjusted seroprevalence by demographic characteristics, by round of data collection, weighted by inverse probability of censoring weights for rounds 2 and 3.

| Round 1 |

Round 2 |

Round 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seropositive (n/total n) | Seroprevalence % (95% CI) | Seropositive (n/total n) | Weighted seroprevalence % (95% CI) | Seropositive (n/total n) | Weighted seroprevalence % (95% CI) | |

| Total | 95/1632 | 5.8% (4.8-7.1) | 93/936 | 10.5% (8.6-12.7) | 78/723 | 11.0% (8.8-13.5) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 40/831 | 4.8% (3.6-6.5) | 41/487 | 8.9% (6.6-12.0) | 33/381 | 8.8% (6.2-12.2) |

| Female | 55/801 | 6.9% (5.3-8.8) | 52/449 | 12.1% (9.3-15.6) | 45/342 | 13.2% (10.0-17.4) |

| Age, yearsc | ||||||

| 2-4 | 16/329 | 4.9% (3.0-7.8) | 13/151 | 8.4% (4.9-14.0) | 6/89 | 6.4% (2.8-13.9) |

| 5-11 | 41/727 | 5.6% (4.2-7.6) | 54/448 | 13.1% (10.1-16.8) | 48/346 | 14.1% (10.7-18.3) |

| 12-18 | 38/576 | 6.6% (4.8-8.9) | 26/337 | 8.2% (5.6-11.8) | 24/288 | 8.8% (5.9-12.9) |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Underweight or normal weight | 72/1179 | 6.1% (4.9-7.6) | 65/687 | 10.1% (7.9-12.7) | 59/518 | 11.4% (8.9-14.5) |

| Overweight | 12/267 | 4.5% (2.6-7.7) | 17/135 | 12.1% (7.6-18.8) | 8/109 | 7.7% (3.9-14.8) |

| Chronic medical conditions | ||||||

| None | 90/1517 | 5.9% (4.8-7.2) | 84/861 | 10.3% (8.4-12.7) | 70/663 | 10.9% (8.7-13.6) |

| Yes | 5/103 | 4.9% (2.0-11.1) | 8/69 | 12.1% (6.1-22.3) | 8/55 | 13.7% (6.9-25.2) |

| Neighborhooda,b,c | ||||||

| HOMA | 28/357 | 7.8% (5.5-11.1) | 25/218 | 12.3% (8.4-17.8) | 20/173 | 12.6% (8.2-18.8) |

| Montréal North | 22/237 | 9.3% (6.2-13.7) | 22/139 | 17.1% (11.5-24.7) | 21/121 | 18.3% (12.1-26.6) |

| Plateau | 28/534 | 5.2% (3.6-7.5) | 29/302 | 9.8% (6.9-13.8) | 31/243 | 13.6% (9.7-18.8) |

| West Island | 17/504 | 3.4% (2.1-5.4) | 17/277 | 6.4% (4.0-10.3) | 6/186 | 3.0% (1.3-6.5) |

| Parental respondent's level of education | ||||||

| No Bachelor's degree | 18/384 | 4.7% (3.0-7.3) | 22/184 | 12.0% (8.0-17.8) | 16/166 | 8.7% (5.3-13.8) |

| Bachelor's degree | 41/647 | 6.3% (4.7-8.5) | 35/380 | 9.9% (7.2-13.5) | 28/265 | 10.8% (7.5-15.3) |

| Graduate degree | 36/581 | 6.2% (4.5-8.5) | 36/362 | 10.5% (7.6-14.3) | 34/284 | 12.9% (9.3-17.6) |

| Parental respondent's race and ethnicitya,b | ||||||

| Racial or ethnic minority | 22/201 | 10.9% (7.3-16.1) | 19/110 | 18.8% (12.3-27.7) | 10/76 | 13.8% (7.5-24.0) |

| White | 73/1406 | 5.2% (4.1-6.5) | 74/815 | 9.4% (7.5-11.7) | 67/640 | 10.4% (8.2-13.1) |

| Number of bedrooms | ||||||

| 1-2 bedrooms | 18/332 | 5.4% (3.4-8.4) | 22/185 | 12.3% (8.1-18.1) | 25/154 | 17.5% (12.0-24.7) |

| 3 bedrooms | 47/740 | 6.4% (4.8-8.4) | 40/417 | 10.1% (7.4 -13.5) | 35/337 | 10.5% (7.6-14.4) |

| 4 bedrooms | 26/445 | 5.8% (4.0-8.4) | 27/267 | 10.9% (7.5-15.6) | 14/182 | 7.9% (4.7-13.0) |

| 5 bedrooms | 4/104 | 3.8% (1.5-9.8) | 4/61 | 6.7% (2.5-16.6) | 4/45 | 8.0% (3.0-19.6) |

| Bedroom densityc | ||||||

| [0,1.5) | 60/1103 | 5.4% (4.2-6.9) | 55/638 | 9.2% (7.1-11.9) | 36/469 | 7.8% (5.6-10.7) |

| 1.5+ | 35/502 | 7.0% (5.0-9.6) | 38/287 | 13.6% (10.0-18.2) | 42/244 | 17.6% (13.2-23.1) |

| Dwelling typea,b,c | ||||||

| Single family | 34/576 | 5.9% (4.2-8.1) | 36/452 | 8.1% (5.9-11.1) | 25/306 | 7.6% (5.1-11.1) |

| Other | 49/537 | 9.1% (7.0-11.9) | 49/425 | 12.5% (9.5-16.3) | 40/315 | 14.1% (10.5-18.7) |

| Household members occupation | ||||||

| Not essential | 44/913 | 4.8% (3.6-6.4) | 57/522 | 11.3% (8.8-14.4) | 39/395 | 9.9% (7.2-13.3) |

| Essential, not health | 30/441 | 6.8% (4.8-9.6) | 24/242 | 10.7% (7.2-15.5) | 22/192 | 12.3% (8.2-18.1) |

| Not essential | 21/267 | 7.9% (5.2-11.8) | 12/166 | 8.0% (4.5-13.8) | 17/131 | 12.8% (8.1-19.8) |

| Annual household incomea,b | ||||||

| < $100,000 CAD | 39/329 | 11.9% (8.8-15.8) | 37/270 | 14.9% (10.9-19.9) | 23/202 | 12.8% (8.6-18.6) |

| ≥ $100,000 CAD | 40/686 | 5.8% (4.3-7.9) | 47/585 | 8.3% (6.3-10.9) | 41/401 | 10.3% (7.6-13.8) |

Significant relationship with seroprevalence at baseline.

Significant relationship with seroprevalence in the second round of data collection.

Significant relationship with seroprevalence in the third round of data collection.

CI, confidence interval.

Seroconversion estimates

The overall average crude rate of seroconversion over the study period was 12.8 per 100 person-years (194 episodes in 1520 person-years, 95% CI 11.0-14.7). In round 2, the rate was 15.7 episodes in 100 person-years (67 episodes in 426 person-years, 95% CI 12.0-19.5), and in round 3, the rate was 11.3 episodes in 100 person-years (32 in 284 person-years, 95% CI 7.4-15.2). Of the 194 infection-induced seroconversions, 137 (71%) did not have a positive self-reported RT-PCR or antigen test before the DBS. Across all rounds of data collection, there were 82 occurrences where a participant self-reported a positive RT-PCR or antigen test at least 21 days before their DBS, with 25 (30%) having had a negative serology test.

The adjusted hazard rates of seroconversion by child and household characteristics showed higher rates in children who were female, whose parent identified as a racial or ethnic minority, in households with incomes less than $100,000 CAD, and in households with higher bedroom density (>1.5 persons per bedroom) (Table 3 ). The West Island had lower seroconversion rates than the other three neighborhoods. There was a higher seroconversion rate associated with the Delta variant than the Alpha variant. The sensitivity analyses with data on children seronegative at round 1 or seropositive with a positive RT-PCR or antigen date and followed for up to two subsequent rounds of serology testing found little evidence of an association with the Delta variant and a weaker association with females and household income but a stronger association with bedroom density and variants that are not of concern (STable 3, see also SFigure 2). The findings from the complete case analyses were similar to the main seroconversion analysis findings, with the exception of a weaker association with bedroom density (STable 4).

Table 3.

Adjusted relative likelihood of seroconversion through follow-up.

| Hazard ratio* (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | ref | |

| Female | 1.48 (1.10-2.00) | 0.01 |

| Age, years | ||

| 2-4 | ref | |

| 5-11 | 1.21 (0.79-1.83) | 0.38 |

| 12-18 | 1.05 (0.67-1.63) | 0.84 |

| Body mass index | ||

| Underweight or normal weight | ref | |

| Overweight | 0.77 (0.49-1.21) | 0.26 |

| Chronic medical conditions | ||

| None | ref | |

| Yes | 1.17 (0.67-2.03) | 0.58 |

| Neighborhood | ||

| Plateau | ref | |

| Montréal North | 1.38 (0.84-2.28) | 0.20 |

| HOMA | 1.11 (0.74-1.67) | 0.62 |

| West Island | 0.47 (0.27-0.81) | 0.007 |

| Parental respondent's level of education | ||

| No Bachelor's degree | ref | |

| Bachelor's degree | 1.09 (0.73-1.62) | 0.68 |

| Graduate degree | 1.18 (0.80-1.76) | 0.41 |

| Parental respondent's race and ethnicity | ||

| White | ref | |

| Racial or ethnic minority | 1.92 (1.30-2.82) | 0.001 |

| Bedroom density (persons per bedroom) | ||

| <1.5 | ref | |

| 1.5+ | 1.34 (0.99-1.82) | 0.059 |

| Dwelling type | ||

| Other | ||

| Single family | 0.84 (0.60-1.16) | 0.28 |

| Annual household income | ||

| < $100,000 CAD | ref | |

| ≥ $100,000 CAD | 0.59 (0.42-0.82) | 0.002 |

| Household member occupation | ||

| Not essential | ref | |

| Essential, not health | 1.17 (0.83-1.65) | 0.38 |

| Essential | 1.22 (0.83-1.81) | 0.31 |

| Predominant variant | ||

| Alpha | ref | |

| Not a variant of concern | 0.52 (0.26, 1.03) | 0.06 |

| Delta | 2.20 (1.37, 3.53) | 0.001 |

| Omicron | 1.51 (0.74, 3.05) | 0.26 |

*longitudinal data from 1690 children; a minimum of 45 days of follow-up (half the risk set period) was required for inclusion in the analysis.

CI, confidence interval.

Seroreversion estimates

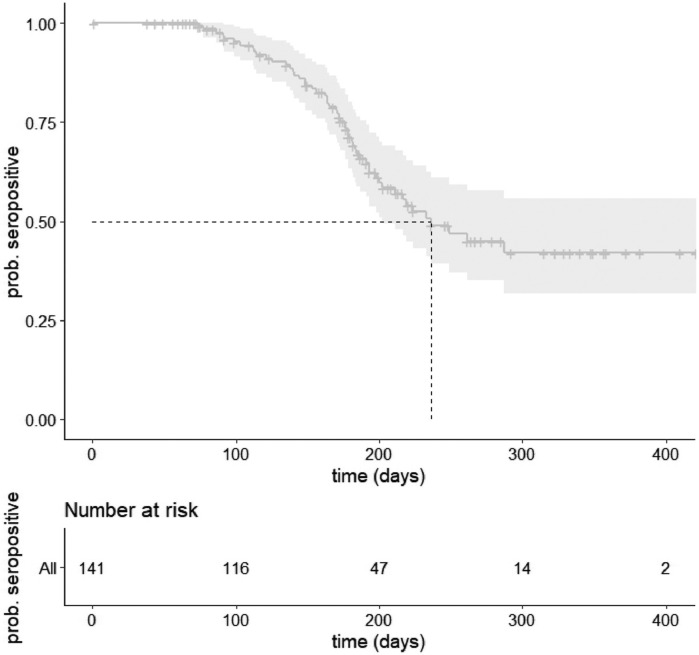

In the main analysis, which included children who were seropositive during any round with at least one follow-up serology test, unvaccinated at seroconversion, and censored at vaccination (n = 141), the median time to seroreversion was 236 days (95% CI 202-NA) (Figure 1 , STable 5). The likelihood of remaining seropositive at 6 months was 68% (95% CI 60-77). The likelihood of remaining seropositive at 1 year dropped to 42% (95% CI 32-56%) (STable 6). In the sensitivity analysis, excluding seropositive children at baseline without a positive RT-PCR or antigen test (n = 84), the median time to seroreversion was 322 days, and the likelihood of remaining positive at 6 months and 1 year was 71% and 30%, respectively. In the sensitivity analysis, without censoring at vaccination (n = 146), the median time to seroreversion was 228 days, and the likelihood of remaining seropositive at 6 months and 1 year were 67% and 19%, respectively (STable 5-6).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to seroreversion in the sample of unvaccinated children and vaccinated children censored at vaccination. In the upper figure, the darker gray line represents the estimated likelihood of remaining seropositive to at least that time point, with the light gray representing the 95% confidence intervals. The lower figure represents the number of seropositive children that remain at risk of seroreversion at five points in time.

Discussion

The data reported here provide estimates of pre-Omicron seroprevalence and seroconversion rates, by household and participant characteristics and time to seroreversion in a school-based cohort of children and adolescents from Montréal, Canada. We also identified the significant risk factors for seroconversion over the study period. These results support other study findings in that the seroprevalence estimates increased over time and that the risk of seroconversion was significantly different in subgroups regarding sex, household income, children of parents who identify as a racial or ethnic minority, household density, and neighborhood of residence. It also provides further evidence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody waning with a median seroreversion time of approximately 7.5 months and the likelihood of remaining seropositive at 1 year dropping to 42%.

The increase in seroprevalence over time was consistent with the pandemic context of Québec, as well as with other seroprevalence studies [18,19]. A blood donor seroprevalence survey among Montréal adults had an estimated 6.4% seroprevalence of anti-N antibodies a few months before our round 1 study period [19]. For children from other regions of Canada, the seroprevalence estimates from the pre-Omicron waves (waves 1-4) have been lower, ranging from 2.8% [20] to 4.6% [21], whereas internationally, the estimates are higher in children in the United States with 44.2% [22], 20.9-36.3% in England [18], and 21.5% [6] in Germany.

In our study, racial and ethnic minority status, lower household income, and higher household density was associated with increased risk of seropositivity and seroconversion in children. It has been established that there has been a disproportionate impact of the pandemic on racial and ethnic communities and lower income households due to social inequalities that have amplified the risk of infection, including household crowding, type of occupation, and reduced access to health care [23]. In our study population, female participants were at a higher risk of seroconversion and seropositivity, which has not been found by most other studies [24]. Participants from the West Island neighborhood were consistently less at risk for seropositivity than the other neighborhoods. In addition to the populations living in the West Island being more affluent and highly educated than Montréal North and Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, it is also a mainly residential suburb of the city, therefore having a lower population density. These disparities in social determinants of health likely attribute to the different seroprevalence estimates between the neighborhoods.

In our study, 37-55% of our seropositive participants (that had at least two serology results) seroreverted during follow up. We also estimated that from the time of seroconversion, the likelihood of remaining seropositive at 6 months was 67-71%, which dropped to 19-42% after 1 year. In other pediatric serological studies, the follow-up time has generally been shorter but studies have found that over time there is a waning of SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels [7,25]. Other pediatric studies have not found an association with waning and asymptomatic versus symptomatic infections [7] but have with age [5] and comorbidities, such as respiratory disease and obesity. The waning appears to be more pronounced in adults and is associated with obesity, older age, and belonging to a racial or ethnic minority [13]. We also found that 30% of children with a self-reported positive test result had a seronegative DBS sample at least 21 days later. Though a portion of these may be attributed to the imperfect sensitivity of our serology tests, the rates of pediatric seroconversion after a positive RT-PCR have been found to differ according to the causative strain, perhaps due to factors, such as differential viral loads, duration of viral shedding, and illness severity [26].

This study has several limitations. There was significant loss to follow-up and, based on anecdotal reports from parents, this was largely associated with the DBS procedure. There was little difference in the losses by household or participant characteristics. Correcting for selection bias in seroprevalence estimates by IPCW showed modest changes in the seroprevalence point estimates, providing some evidence that the loss to follow-up did not substantially impact our results (median percent changes in rounds 2 and 3 were 6% and 5%, respectively). Our infection-acquired seroprevalence estimate among vaccinated children in round 3 is likely underestimated due to the lower sensitivity of the N assay than the RBD assay and the possible more rapid waning of anti-N antibodies [2,27]. Misclassification may also have occurred among unvaccinated children, given the imperfect sensitivity and specificity of antibody testing. Though anti-RBD antibodies are relatively long-lasting, they appear more likely to fall below the threshold of detection than anti-Spike antibodies. Therefore, using only the RBD assay to determine the seropositivity among unvaccinated children may have limited our ability to detect antibodies to infection in this group; although, some studies suggest that RBD is more correlated with neutralizing antibodies and thus more correlated with protection [28,29].

Another limitation of the study is that it was powered for precision of neighborhood seroprevalence estimates, and given the substantial loss to follow-up, the seroreversion and seroconversion analyses may have lacked the power to detect meaningful associations and estimate time to event with sufficient precision. The seroconversion analyses uncovered interesting associations with ethnic/racial minority, household income, and neighborhood, but a larger number of seroreversions and/or longer follow-up would have been needed to more precisely estimate the time to seroreversion. Serostatus was only assessed periodically (e.g., on average at 6-month intervals), which resulted in error being introduced into the timing of seroconversion and seroreversion. Though pooled logistic regression was well suited to this context of periodic assessments, by estimating, then pooling hazard rates in successive intervals of the study period, there was likely a measurement error in the estimation of the rates of seroconversion and the time to seroreversion, given that either event could have occurred weeks before the timing of the blood sample.

A major contribution of our study is its prospective longitudinal design, which continues to be relevant, given the introduction of variants and the waning of infection-induced antibodies. Given the limited RT-PCR testing, serological studies provide valuable contributions for infection prevalence estimates, in addition to helping us better understand the dynamics of antibody levels after infection, which can inform public health efforts and recommendations regarding risk mitigation and vaccination.

Declaration of competing interest

JP reports grants from MedImmune, grants and personal fees from Merck and AbbVie, and personal fees from AstraZeneca; all outside the submitted work. All other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding

The funding for this study was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada through the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force to Dr Zinszer.

Ethical approval

The research ethics boards of the Université de Montréal and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine approved this study in accordance with the laws of the Government of Québec. All parents and children gave written informed consent before participation.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all of the children, teens, and their parents for their precious contribution to our study. The authors also thank all of the day cares, schools, and school boards for their help with recruitment. The authors are grateful for the support and guidance of our partners: the Direction régionale de santé publique de Montréal, the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force, the Institut national de santé publique du Québec, and the Observatoire pour l’éducation et la santé des enfants.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: KZ, JP, GDS, CQ; Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: KZ, KC, LP, AS, MBDT, IC, JP, MEH, BM, JC, CN, GB, GDS; Drafting of the manuscript: KZ, KC; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KZ, KC, BM, LP, AS, IC, MBDT, JP, MEH, JC, CN, GB, GDS, CQ; Statistical analysis: KC; Obtained funding: KZ, GDS, CQ; Administrative, technical, or material support: KZ, KC, BM, LP, AS, MBDT, IC, MEH, JC, CN, GB; Supervision: KZ, LP, BM, GB, GDS. KZ had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.03.036.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

SFigure 1 Directed acyclic graph for seroconversion regression analysis to identify the minimally sufficient adjustment set for household income

SFigure 3 Round 1 sample sizes by serostatus, vaccination status and for self-reported positive test

SFigure 4 Round 2 sample size by serostatus, vaccination status and for self-reported positive test

SFigure 5 Round 3 sample size by serostatus, vaccination status and for self-reported positive test

SFigure 2 Weekly number of EnCORE DBS, percentage of variants of concern (VOC) and Montréal incidence rate per 100. Data from the Institut national de santé publique du Québec https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees.

References

- 1.Long QX, Liu BZ, Deng HJ, Wu GC, Deng K, Chen YK, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isho B, Abe KT, Zuo M, Jamal AJ, Rathod B, Wang JH, et al. Persistence of serum and saliva antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poehlein E, Rane MS, Frogel D, Kulkarni S, Gainus C, Profeta A, et al. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies following COVID-19 diagnosis: a longitudinal study of patients at a major urgent care provider in New York. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022;103 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2022.115720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.COVID-19 Community Research Partnership Study Group Duration of SARS-CoV-2 sero-positivity in a large longitudinal sero-surveillance cohort: the COVID-19 Community Research Partnership. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:889. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06517-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Chiara CD, Cantarutti A, Costenaro P, Donà D, Bonfante F, Cosma C, et al. Long-term immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and adults after mild infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.21616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsten C, Kahre E, Blankenburg J, Schumm L, Haag L, Galow L, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in German secondary schools from October 2020 to July 2021: a longitudinal study. Infection. 2022;50:1483–1490. doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renk H, Dulovic A, Seidel A, Becker M, Fabricius D, Zernickel M, et al. Robust and durable serological response following pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2022;13:128. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barcellini L, Forlanini F, Sangiorgio A, Gambacorta G, Alberti L, Meta A, et al. Does school reopening affect SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among school-age children in Milan? PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ulyte A, Radtke T, Abela IA, Haile SR, Berger C, Huber M, et al. Clustering and longitudinal change in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in school children in the canton of Zurich, Switzerland: prospective cohort study of 55 schools. BMJ. 2021;372:n616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statistics Canada . 2016. Census profile, 2016 Census: Montréal [Census metropolitan area], Québec and Canada [Country]https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CMACA&Code1=462&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=Montréal&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&TABID=1&B1=All [accessed 31 August 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinszer K, McKinnon B, Bourque N, Zahreddine M, Charland K, Papenburg J, et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among school and daycare children and personnel: protocol for a cohort study in Montreal, Canada. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Racine É, Boivin G, Longtin Y, McCormack D, Decaluwe H, Savard P, et al. The REinfection in COVID-19 Estimation of Risk (RECOVER) study: reinfection and serology dynamics in a cohort of Canadian healthcare workers. Influ Other Respir Viruses. 2022;16:916–925. doi: 10.1111/irv.12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naing L, Winn T, Rusli BN. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci. 2006;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2017. Clinical Growth Charts.https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/clinical_charts.htm [accessed 31 July 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanji JN, Bailey A, Fenton J, Ling SH, Rivera R, Plitt S, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies formed in response to the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1237 mRNA vaccine by commercial antibody tests. Vaccine. 2021;39:5563–5570. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allison PD. Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13:61. doi: 10.2307/270718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladhani SN, Ireland G, Baawuah F, Beckmann J, Okike IO, Ahmad S, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant, infection rates, antibody seroconversion and seroprevalence rates in secondary school students and staff: active prospective surveillance, December 2020 to March 2021, England. J Infect. 2021;83:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Héma-Québec . 2022. Phase 4 of the study on seroprevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in Québec.https://www.covid19immunitytaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/hema-quebec-seroprevalence-report-march-2022.pdf [accessed 31 August 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 20.TARGetKids! COVID-19 study for children and families https://www.targetkids.ca/covid-19 [Accessed 23 September 2022].

- 21.Bushnik T, Earl S, Clark J, Cabot J. COVID-19 infection in the Canadian household population. Health Rep. 2022;33:24–33. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202200400003-eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke KEN, Jones JM, Deng Y, Nycz E, Lee A, Iachan R, et al. Seroprevalence of infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies - United States, September 2021–February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:606–608. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7117e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saarinen S, Moustgaard H, Remes H, Sallinen R, Martikainen P. Income differences in COVID-19 incidence and severity in Finland among people with foreign and native background: a population-based cohort study of individuals nested within households. PLOS Med. 2022;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pijls BG, Jolani S, Atherley A, Dijkstra JI, Franssen GH, Hendriks S, et al. Temporal trends of sex differences for COVID-19 infection, hospitalisation, severe disease, intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death: a meta-analysis of 229 studies covering over 10M patients. F1000Res. 2022;11:5. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.74645.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez-Saez J, Zaballa ME, Yerly S, DO Andrey, Meyer B, Eckerle I, et al. Persistence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: immunoassay heterogeneity and implications for serosurveillance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1695.e7–1695.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toh ZQ, Mazarakis N, Nguyen J, Higgins RA, Anderson J, Do LA, et al. Comparison of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 variants in Australian children. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7185. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34983-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371:eabf4063. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner A, Guzek A, Ruff J, Jasinska J, Scheikl U, Zwazl I, et al. Neutralising SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific antibodies persist for at least six months independently of symptoms in adults. Commun Med (Lond) 2021;1:13. doi: 10.1038/s43856-021-00012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAndrews KM, Dowlatshahi DP, Dai J, Becker LM, Hensel J, Snowden LM, et al. Heterogeneous antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain and nucleocapsid with implications for COVID-19 immunity. JCI Insight. 2020;5 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.142386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SFigure 1 Directed acyclic graph for seroconversion regression analysis to identify the minimally sufficient adjustment set for household income

SFigure 3 Round 1 sample sizes by serostatus, vaccination status and for self-reported positive test

SFigure 4 Round 2 sample size by serostatus, vaccination status and for self-reported positive test

SFigure 5 Round 3 sample size by serostatus, vaccination status and for self-reported positive test

SFigure 2 Weekly number of EnCORE DBS, percentage of variants of concern (VOC) and Montréal incidence rate per 100. Data from the Institut national de santé publique du Québec https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees.