Abstract

Community health centers (CHCs) are a crucial source of care for reproductive-aged women. Some CHCs receive funding from the federal Title X program to provide family planning services. We described provision of most effective (intrauterine devices and implants) and moderately effective (short acting hormonal methods) contraceptive methods in a large network of 384 CHCs across 20 states, 2016–2018. Title X clinics provided more most and moderately effective contraception at all time points and for all age groups (adolescent, young adult, adult). Title X clinics provided 52% more (aRR=1.52, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.88) most effective contraceptives to women at risk of pregnancy than those not funded by Title X. This finding was especially notable for adolescents (58% more; aRR=1.58, 95% CI: 1.24, 2.02). Title X clinics play a key role in access to effective contraception across the United States safety net. Strengthening the Title X program should continue to be a policy priority for the Biden-Harris administration.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly half (45%) of the over 6 million annual pregnancies in the United States (US) are unintended(1); reduction of unintended pregnancy is a national public health priority for both individual and community health(2, 3). Unintended pregnancy is associated with negative health and economic consequences(4), including delays in initiating prenatal care, reduced likelihood of breastfeeding, increased risks of maternal depression and intimate partner violence during pregnancy(4, 5) and lower educational and economic achievement(6, 7). Disparities in who experiences unintended pregnancy are widening, becoming more concentrated among adolescents, women of color, and women living in poverty(1). Access to effective contraception is key to promoting reproductive autonomy by ensuring individuals can realize their decisions about if and when to become pregnant(8).

Community health centers (CHCs), which include Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), rural health centers, and county health departments are a crucial source of care for low-income reproductive-aged women(9). CHCs meet the needs of their community by providing care regardless of insurance or documentation status, or ability to pay. As part of the obligations under Section 330(10), FQHCs must provide or arrange for access to voluntary family planning and reproductive health services. However, individual FQHCs vary considerably in the scope and quality of family planning services they deliver(11, 12), and barriers persist to delivering contraceptive services, especially the most effective methods, long-acting reversible contraception (LARC; IUDs and implants,). These barriers include difficulties stocking devices on site, making provision of same-day LARC provision challenging(13–16); the cost of contraceptive care, especially challenging when serving low-income and uninsured populations(13, 17, 18); and lack of staff trained in LARC insertions and removals(13–19).

Some CHCs participate in the federal Title X family planning program, which provides supplemental funding for clinics to provide contraceptive services and supplies, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment, and related sexual and reproductive healthcare(20). The Title X program is a key payor for contraceptive services for low-income individuals(21). In contrast to Section 330 funding, Title X funding requires that clinics provide on-site access to a broad range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods(22) and adhere to national family planning quality guidelines(23). Title X provides targeted funding, including site-level incentives to stock LARC devices by covering up-front costs, which facilitates same-day provision(13); and training for staff to ensure appropriate staffing to provide a wide range of methods. Health centers that participate in Title X are therefore be expected to provide more robust contraceptive services compared with non-Title X-funded CHCs(12, 24), as previous literature has found.

In 2019, the Trump-Pence administration weakened the Title X program, implementing non-evidence based guidelines, including the prohibition of abortion referrals; removal of the requirement to provide a full range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods; and removal of confidentiality provisions for adolescents(25). Many grantees and clinic sites left the Title X program rather than comply with these changes, and the number of clients served by Title X dropped from 3.9 million in 2018 to 1.5 million in 2020(26, 27). The Biden-Harris administration recently reversed those changes(28); studies about the impact of weakening Title X require a baseline for comparison and this study fills that gap. We need comprehensive information about the role of Title X in the US Safety net prior to the 2019 rule changes.

The purpose of this study was to describe provision of contraception in CHCs by Title X status and patient age, in 2016–2018, prior to the 2019 implementation of rule changes that weakened the Title X program(25, 29). Using patient-level electronic health record (EHR) data from 384 CHC clinics across the US, we assessed provision of most (LARC; IUD or implant) and moderately effective (oral pill, patch, contraceptive injection, vaginal ring) contraceptive methods using the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) quality metric(30). We hypothesized that Title X CHCs were more likely to provide most effective methods of contraception than non-Title X CHCs, especially for adolescents (15–19 years old).

METHODS

We used individual-level EHR data to conduct a retrospective cohort study to examine clinic-quarter rates of contraception provision by Title X funding status, adjusted for state, clinic, and individual patient characteristics.

We used the Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Center Network (ADVANCE) clinical research network, a member of PCORnet(31). A total of 144 independent health systems in 26 states contribute data to ADVANCE. For this study, CHC clinics (i.e., brick-and-mortar care locations) were selected when meeting certain care type characteristics and patient volume criteria, described below. We used patient data from 384 CHC clinics in 20 states that were live on the EHR system by September 1, 2015 (four months before study start) and through the study end of December 31, 2018. We excluded clinics that did not provide primary care services (e.g. dental clinics) or provided fewer than 50 visits to women of reproductive age (15–49) per year (see Technical Appendix for details(32)).

Within included clinics, we identified people documented as female in the EHR, at risk of pregnancy, between ages of 15–49 years, with at least one ambulatory encounter between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2018. We were unable to comprehensively assess gender identity and will use the term ‘women’ throughout the analysis to refer to these patients. We used the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) metric specifications to identify women at risk of pregnancy(30). The OPA metric is intended for use with claims or EHR data and does not incorporate pregnancy intention. Patients were determined to be at risk of pregnancy in the absence of any EHR evidence of sterilization, infecundity, or current pregnancy among structured EHR fields, consistent with previous literature and national metrics(30, 33, 34) (see Technical Appendix for details(32)). We determined each woman’s eligibility for inclusion in the denominator each quarter.

Our outcomes were woman-level rates of provision of most effective (LARC; IUDs and implants) or moderately effective (short-acting hormonal contraception methods of oral contraceptives, injectables, vaginal ring or patch)(35) contraception, following Office of Population Affairs (OPA) quality metric specifications(34). We extracted contraception information from several structured EHR fields, including prescription orders as identified by medication code and name searches, records of medical procedures using CPT, HCPCS and ICD-10 procedure codes, as well as ICD-10 diagnosis codes (see Technical Appendix(32)).

After identifying contraception provision by woman-quarter level, we aggregated data to the clinic-quarter level. We summed the incidence of most and moderately effective method provision at the clinic-quarter level, and then divided that sum by the total number of patients at risk of pregnancy in that clinic-quarter. This resulted in the unadjusted proportion of all patients at risk of pregnancy (denominator) who received most or moderately effective contraception (numerator) per clinic-quarter.

Our main independent variable, clinic Title X funding status, was obtained by cross-referencing ADVANCE CHC and clinic locations with a list of Title X-funded clinics that we obtained from the Office of Population Affairs through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) records request.

We included patient covariates extracted from EHR records and aggregated to the clinic level overall. We classified women as adolescents (15–19 years old), young adults (20–24 years old), or adults (25–49 years old). We included proxy measures of systemic disparities affecting health care access(36): clinic level patient mix by race/ethnicity and poverty level. Latinx ethnicity was captured from patient self-reported Hispanic ethnicity or Spanish language preference. Non-Latinx Black and White race were ascertained from patients’ EHR-recorded race and ethnicity. The clinic proportion of low-income patients (0 to <138% of the Federal Poverty Level [FPL]) was based on patients’ first reported household income during the study period.

We included additional characteristics of the overall patient population at study clinics. We calculated the mean number of patients seen with ambulatory encounters during the study time period. We calculated ‘patient mix’ as the proportion of ambulatory encounters with reproductive aged women relative to ambulatory encounters with all ages and genders and ‘payor mix’ as the proportion of uninsured ambulatory encounters divided by the total number of ambulatory encounters per clinic. The proportion of women’s health specialist visits (‘provider mix’) was the total count of ambulatory encounters to women of reproductive age at the clinic with an ambulatory encounter to women’s healthcare specialist divided by the total number of ambulatory encounters to women of reproductive age. Data on medical specialty was captured from each providers National Provider Identifier (NPI) data. We classified women’s health specialists as obstetricians, gynecologists, midwives, women’s health advanced practice clinicians (APCs), or maternal/fetal medicine providers.

Clinic location was categorized as rural based on the clinic site address using 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes; small town cores and lower were categorized as rural(37). We also included state level indicators: Medicaid expansion status (as of Jan 1 2016)(38), and presence of a state family planning program (1115/State Plan Amendment/Family Planning waiver) status(39). We classified Wisconsin as a Medicaid expansion state following previous literature(40, 41), given that they expanded Medicaid to 100% of the Federal Poverty Level in 2014, although outside of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

We first calculated the mean clinic proportion of patients with demographic characteristics described above by clinic Title X status, in addition to clinic- and state-level characteristics of study clinics. Next, we calculated clinic-quarter rates of provision of most and moderately effective contraception encounters.

We used a generalized estimating equation Poisson model to estimate rates of contraception provision, adjusted for the clinic, patient, and state characteristics described above, and we plotted the model-predicted population rates for each quarter by Title X status. The analytic unit for the models was the clinic-quarter. A total of 605,621 patients, comprising 149,909 patients with contraceptive provision and 455,712 patients without contraceptive provision, were observed at 384 clinics over the 3 years (12 quarters) of the study. All clinics contributed data for each quarter. Utilizing this patient-level data, aggregated to the clinic-quarter level, a total of 4,608 clinic-quarters of data were utilized in the models.

Models were performed for the overall sample and stratified by age group (adolescents, young adults, adults). To compare results in aggregate across the entire study period, we calculated adjusted squares means estimates for all quarters, and compared averaged Title X estimates to those from clinics not funded by Title X. We used an autoregressive correlational structure and an empirical sandwich variance estimator to account for temporal correlation, and included an offset of the log of the total number of women at risk of pregnancy in each clinic to account for differences in overall clinic size.

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, to account for clinics that do not have a reproductive health focus, we excluded 55 clinics with a large proportion of mental health encounters (>75th percentile) despite not being classified as mental health clinics in EHR metadata. Second, we excluded 97 ‘lower-volume’ clinics that were in the bottom quartile of visits for women of reproductive age. We did this to remove clinics not likely to provide contraceptive services. Results were robust to these changes, and we present our main analysis only. All analyses were conducted in SAS (version 7.15); figures were prepared in R (version 3.6.2). This study was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB).

Limitations

Our sample of CHCs may not be generalizable to all patients in CHCs, CHC clinics, or states. However, our data come from the largest national set of data from people accessing care in safety net settings, and the ADVANCE patient population is demographically and clinically similar to the overall CHC population(31). Similarly, our sample of Title X clinics may not represent the universe of Title X clinics. We compared our sample patient characteristics to data reported by the Title X program; our sample skews younger and has a lower proportion of women who are Black and non-Latina than the overall Title X program(27). However, few studies are able to compare clinics with Title X funding to those without it across multiple states and with patient-level objective data as we have done using this dataset. Third, there may be unmeasured differences between Title X and non-Title X CHCs that our study does not capture. We control for patient, provider, and payor mix at the clinics in our sample. Fourth, we are not able to comprehensively identify gender identity among patients in our sample and we did not have access to an organ inventory to assess risk of pregnancy. This may result in misclassification of risk of pregnancy(42), however small.

RESULTS

Of 384 CHCs included in the analysis, 12% (n=46) were Title X funded clinics and 88% (n=338) were non-Title X funded clinics (Exhibit 1). Title X clinics served a lower proportion of Black non-Latinx patients (9.0%) compared with non-Title X clinics (16.6%). Non-Title X clinics saw a slightly smaller proportion of adolescents (26.9% vs. 29.0% Title X) and reproductive aged women (34.6% vs 44.1% Title X,). Nearly all (98.0%) Title X clinics were in states that expanded Medicaid; approximately two thirds of non-Title X clinics (66.0%) were in Medicaid expansion states.

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics of study Community Health Center clinics by Title X funding status. 2016–2018.

| Title X | Not Title X | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of clinics | 46 | 338 | - |

| Mean number of patients per clinic | 4,272 | 3,228 | <0.001 |

| Patient Variables (mean proportion of clinic patients (SE)) | |||

| Latinx | 29.1 | 30.5 | 0.748 |

| Black, non-Latinx | 9.0 | 16.6 | 0.021 |

| White, non-Latinx | 31.1 | 25.4 | 0.109 |

| Adolescent (15–19 years old) | 29.0 | 26.9 | 0.686 |

| Young adult (20–24 years old) | 13.9 | 11.1 | 0.013 |

| Income < 138% of Federal Poverty Level | 63.2 | 59.8 | 0.506 |

| Clinic Variables (mean unless otherwise specified) | |||

| Rural clinics (count, % of clinics) | 6 (13.0%) | 33 (9.8%) | 0.491 |

| Patient mix: Proportion of encounters to women aged 15–49 out of all encounters | 44.1 | 34.6 | <0.001 |

| Provider mix: Proportion of encounters to women’s health specialists out of encounters to women aged 15–49 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 0.831 |

| Payor mix: Proportion of uninsured encounters out of all encounters | 21.5 | 22.9 | 0.477 |

| State Variables (count, percentage of clinics) | |||

| Medicaid expansion (count, %) | 45 (98.0%) | 225 (66.0%) | <0.001 |

| State Family Planning Program (State Plan Amendment/1115 Waiver) (count, %) | 40 (85.0%) | 298 (88.0%) | 0.813 |

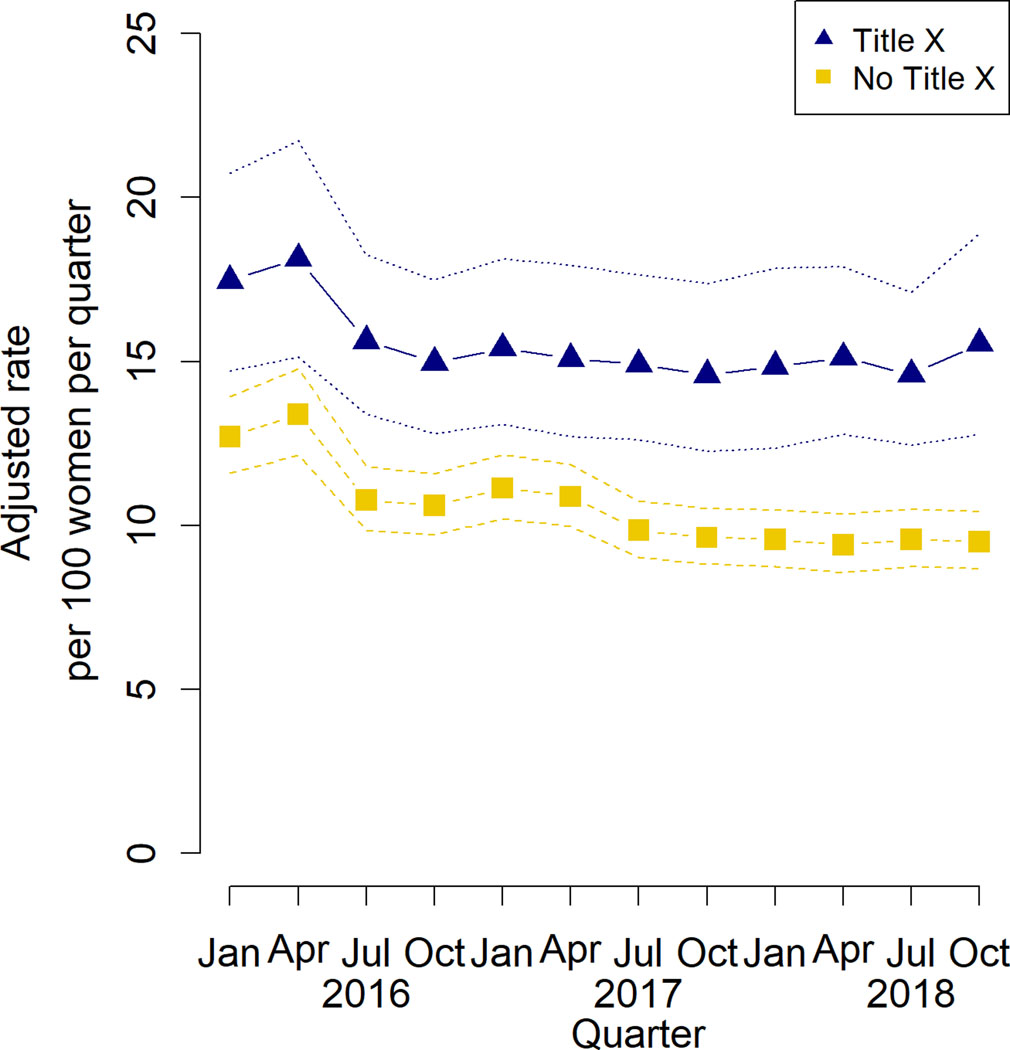

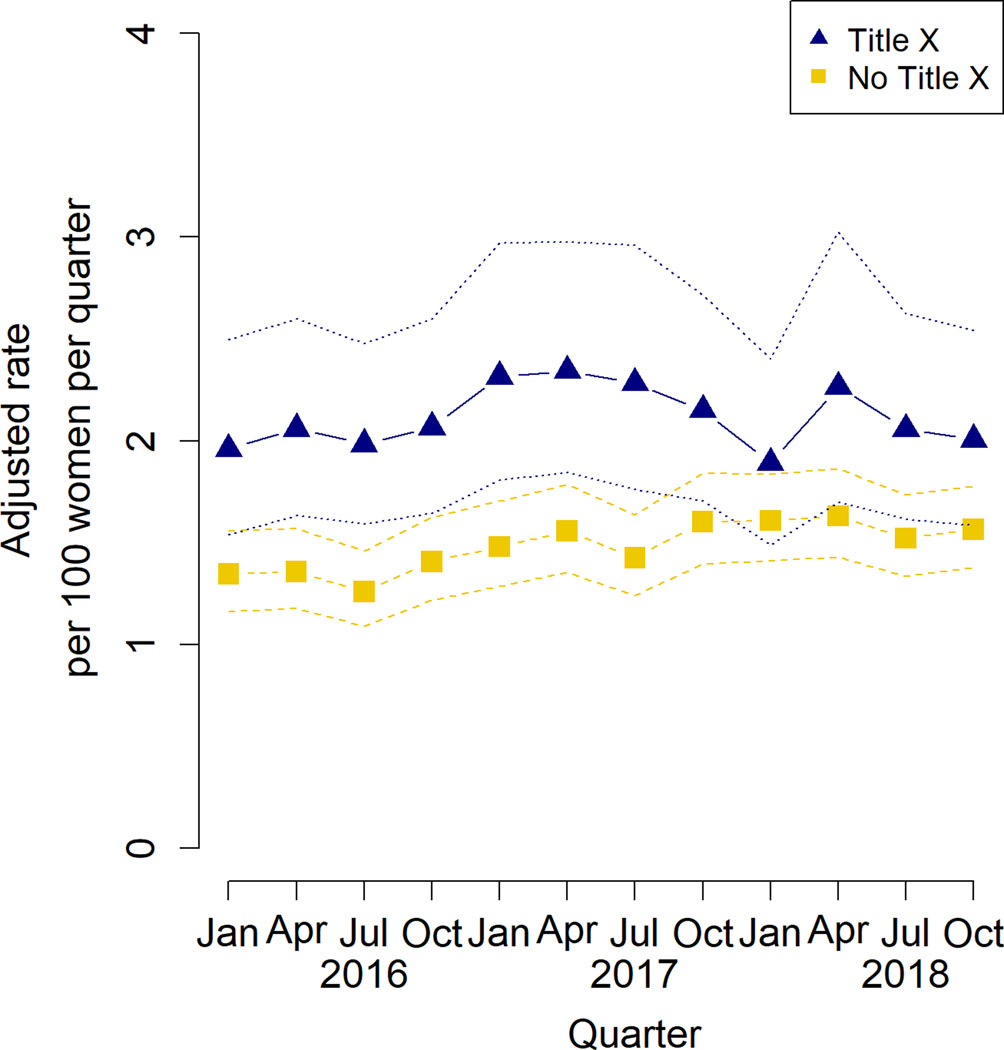

Over the three-year study period, adjusted clinic-quarter rates of most and moderately effective contraceptive methods remained stable, with Title X clinics providing both most and moderately effective methods at a higher rate than non-Title X clinics (Exhibits 2 and 3, respectively). In the last quarter of the study, Title X funded clinics provided most effective methods to 2.2% of women at risk of pregnancy, and moderately effective methods to 15.8% of at-risk women, compared to 1.6% and 9.5%, respectively, among CHC clinics not funded by Title X (p = 0.001 modst effective, p < 0.001 moderately effective).

Exhibit 2.

Adjusted quarterly rates of provision of most effective contraception by Title X status to women at risk of pregnancy.

SOURCE: Study-generated data. NOTES: Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals per quarter. Model results were calculated using Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Poisson with indicators for each clinic-quarter, adjusting for clinic-level patient demographics, clinic- and state-level covariates.

Exhibit 3.

Adjusted quarterly rates of provision of moderately effective contraception by Title X status to women at risk of pregnancy.

SOURCE: Study-generated data. NOTES: Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals per quarter. Model results were calculated using Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Poisson with indicators for each clinic-quarter, adjusting for clinic-level patient demographics, clinic- and state-level covariates.

Title X clinics had the highest rates of most effective method provision among young adults and adolescents over the study period(Appendix Exhibit A(43)). Averaging across all study quarters (n = 4,608 clinic-quarters), Title X funded clinics provided 52% more most effective contraceptives to women at risk of pregnancy than non-Title X funded clinics (aRR=1.52, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.88), p = 0.001; Exhibit 4). Most effective contraception provision at Title X clinics was more pronounced among adolescents (58% higher, 95% CI 24% - 100%) than among young adults (26% higher, 95% CI 2% - 61%) and adults (46% higher, 95% CI 17% - 83%), compared with non-Title X clinics.

Exhibit 4.

Adjusted relative rate of most or moderately effective contraception provision by Title X funding status, 2016–2018

| Relative increase for Title X clinics compared to non-Title X clinics | 95% confidence interval (lower bound, upper bound) | |

|---|---|---|

| Most effective | ||

| Overall | 1.52 | (1.23, 1.88) |

| Adolescents (15–19 years) | 1.58 | (1.24, 2.02) |

| Young Adults (20–24 years) | 1.26 | (0.98, 1.61) |

| Adults (25–49 years) | 1.46 | (1.17, 1.83) |

| Moderately effective | ||

| Overall | 1.49 | (1.29, 1.73) |

| Adolescents (15–19 years) | 1.35 | (1.11, 1.62) |

| Young Adults (20–24 years) | 1.34 | (1.13, 1.58) |

| Adults (25–49 years) | 1.61 | (1.33, 1.94) |

SOURCE: Study-generated data.

NOTE: Most effective contraceptives: intrauterine devices or contraceptive implants. Moderately effective contraceptives: oral pill, patch, contraceptive injection, vaginal ring.

Adjusted means estimate (relative rate) of prevalence of contraception provision by Title X clinics vs non-Title X clinics, averaged across the entire study period, from a total of 4,608 clinic-quarters, 2016–2018. Estimates obtained from Poisson regression model with log link and autoregressive correlation structure with robust variance estimator; relative rate estimates from LSM estimate contrast statement of quarter*Title X interaction.

DISCUSSION

Using EHR data across the US safety net, we show that CHC clinics that receive Title X funding consistently provide access to most and moderately effective contraception at higher rates (52% more most and 49% moderately effective) than CHC clinics that do not. This finding was consistent during each quarter of the three-year study period and across all age groups. Our findings demonstrate that CHCs in the Title X program provide access to most and moderately effective contraceptive methods. We found that Title X clinics were 58% more likely to provide most effective contraception and 35% more likely to provide moderately effective contraception to adolescents compared with non-Title X clinics.

Our results support previous work, which has shown that Title X clinics provide access to effective contraception. However, evidence that compares Title X clinics to other safety net providers has been limited to single states(44–47), relied on site-level data(47–49), or focused on the Medicaid expansion period(33). Previous work has highlighted the important role of Title X in states that did not expand Medicaid in providing access to contraception(50, 51) and in School-Based Health Center (SBHC) clinics(52), key access points for adolescents. We find a similar important role for Tile X in providing access to effective contraception across states and safety net clinics.

Title X CHC clinics are key access points for effective contraception for adolescents. Adolescents have been shown to choose and continue LARC methods when cost barriers are removed(53, 54), but provider bias and lack of provider training can pose barriers to adolescent access to LARC(55, 56). Young women and women of color are more likely to report experiences of coercion or lack of autonomy; it is critical that all contraceptive counseling be centered in a reproductive justice framework that focuses on meeting the needs of the individual(57, 58). The Title X program ensures that their clinics received specialized trainings in evidence based reproductive health care, including specialty training in patient-centered counseling, that centers on the needs of the individual and avoids coercion(59). Developmentally-appropriate, patient centered-counseling and shared decision-making can emphasize attention to the needs and preferences of adolescents(60, 61) and ensure human rights(62). Adolescents were specifically targeted under the Trump-Pence administrations changes to the Title X program; confidentiality provisions, known to be especially important to adolescents(63, 64), were removed, prioritizing parental involvement in care. We show that Title X clinics are key to supporting access to LARC for adolescents who seek care in CHCs; the Biden-Harris reversal of the Trump-era changes re-instates confidentiality provisions, ensuring the ability of the Title X network to provide quality contraceptive care to adolescents.

Policy Implications

Our results provide key evidence about contraceptive service delivery at CHCs, and the important role of Title X funding in the CHC network. Our results are from 2016–2018, the period of time preceding important changes made to the Title X program by the Trump-Pence administration. These changes included: prohibition of abortion referrals; complete financial and physical separation of abortion services from other services; removal of the requirement to provide a full range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods; and removal of confidentiality provisions for adolescents(25). These changes significantly decreased the capacity of the Title X program, with one out of 5 grantees leaving the program(27, 65). The impacts of these changes are expected to be most harmful among adolescents, and women who are un- or under-insured or rely on Title X funding to access contraception(20, 66, 67). The Biden-Harris administration recently reversed the Trump-Pence administration changes(25, 68), inviting former grantees to re-apply for Title X funding(26). Future work focusing on the impact of this disruption in the Title X network, such as the impact that the 2019 rule changes had on national rates of adolescent pregnancy, requires a baseline for comparison. Our results clearly show that Title X expands access to effective contraception in the US safety net; strengthening Title X should continue to be a national health policy priority.

Conclusion

In sum, we find that in a large network of safety net clinics, CHCs that receive funding through the Title X family planning program provide most and moderately effective contraception at higher rates than non-Title X funded CHCs. Their impacts are especially notable for adolescents, underscoring the role of Title X in providing access to contraception for the adolescent population across the safety net. Recent action by the Biden-Harris administration to reverse the Trump-era rule changes(69) is a promising step to protect and enhance access to effective contraception for low-income women nationally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was conducted with the Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Center Network (ADVANCE) ClinicalResearch Network (CRN). OCHIN leads the ADVANCE network in partnership with Health Choice Network, Fenway Health, Oregon Health and Science University, and the Robert Graham Center HealthLandscape. ADVANCE is funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), contract number RI-CRN-2020-001.

Funding Information:

This work is supported by the Office of Population Affairs (OPA)(1 FPRPA006071-01-00; Darney, PI) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (1R01HS025155-01; Cottrell, PI)

Disclosures:

Dr. Darney’s institution receives research support from Merck/Organon. Dr. Darney serves on the Board of directors of the Society of Family Planning (SFP)

References:

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2021 Apr 27];374(9):843–52. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa1506575 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Healthy People 2030 [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on Core Metrics for Better Health at Lower Cost; Institute of Medicine. Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Health Care Progress. Blumenthal D, Malphrus E, McGinnis JM, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US) [Internet]; 2015. Apr 28 [cited 2021 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/19402/vital-signs-core-metrics-for-health-and-health-care-progress. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE. Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies. Epidemiol Rev [Internet]. 2010. [cited 2021 Apr 21];32(1):152–74. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3115338/pdf/mxq012.pdf DOI: 10.1093/epirev/mxq012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception [Internet]. 2009. [cited 2021 Apr 21];79(3):194–8. Available from: https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(08)00457-5/fulltext DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman SD, Foster EM, Furstenberg FF Jr., Reevaluating the costs of teenage childbearing. Demography [Internet]. 1993. [cited 2021 Apr 27];30(1):1–13. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2061859 DOI: 10.2307/2061859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JB, Philip Morgan S, Harris KM, Guilkey DK. The educational consequences of teen childbearing. Demography [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2021 Apr 21];50(6):2129–50. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3944136/pdf/nihms528300.pdf DOI 10.1007/s13524-013-0238-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Upadhyay UD, Dworkin SL, Weitz TA, Foster DG. Development and validation of a reproductive autonomy scale. Stud Fam Plann [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2021 Nov 13];45(1):19–41. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00374.x DOI: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Association of Community Health Centers. Community Health Center Chartbook. 2021. January. [cited 2021 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Chartbook-Final-2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbaum S, Sharac J, Shin P, Tolbert J. Community Health Center Financing: the Role of Medicaid and Section 330 Grant Funding Explained [Internet]. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019. [updated 2019 March 21; cited 2021 Nov 19]. Available from: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Community-Health-Center-Financing-The-Role-of-Medicaid-and-Section-330-Grant-Funding-Explained. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost JJ, Gold RB, Frohwirth LF, Blades N. Variation in Service Delivery Practices Among Clinics Providing Publicly Funded Family Planning Services in 2010 [Internet]. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute; 2012. [updated 2012 May; cited 2021 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/clinic-survey-2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood S, Beeson T, Bruen B, Goldberg DG, Mead H, Shin P, et al. Scope of family planning services available in Federally Qualified Health Centers. Contraception. 2014. [cited April 21, 2021];89(2):85–90. Available from: https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(13)00640-9/fulltext DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Factors Influencing Access to Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives at Federally Qualified Health Centers. Washington, DC; Waxman Strategies; 2019. [updated 2019 July; cited 2021 Nov 07]. Available from https://waxmanstrategies.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/FQHC-LARC-Project_Policy-White-Paper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janiak E, Clark J, Bartz D, Langer A, Gottlieb B. Barriers and Pathways to Providing Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives in Massachusetts Community Health Centers: A Qualitative Exploration. Perspect Sex Reprod Health [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2021 Nov 5];50(3):111–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29940086/ DOI: 10.1363/psrh.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood S, Goldberg DG, Beeson T, Bruen BK, Johnson K, Mead H, et al. Health Centers and Family Planning: Results of a Nationwide Study. Washington, DC: George Washington University, School of Public Health & Health Services; 2013. 56 p.Available from: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1059&context=sphhs_policy_facpubs [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper CC, Stratton L, Raine TR, Thompson K, Henderson JT, Blum M, et al. Counseling and provision of long-acting reversible contraception in the US: National survey of nurse practitioners. Prev Med [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2021 Nov 10];57(6):883–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3890255/ DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg DG, Wood SF, Johnson K, Mead KH, Beeson T, Lewis J, et al. The organization and delivery of family planning services in community health centers. Womens Health Issues [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2021 Nov 3];25(3):202–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1049-3867(15)00024-9 DOI: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beeson T, Wood S, Bruen B, Goldberg DG, Mead H, Rosenbaum S. Accessibility of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) in Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs). Contraception [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2021 Nov 13];89(2):91–6. Available from: DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enhancing Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) Uptake and Reimbursement at Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Toolkit for States. New York, NY: The National Institute for Reproductive Health; 2016. Oct. 19 p. Available from: https://www.nirhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/LARC-Toolkit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold RB, Sonfield A. Title X Family Planning Services: Impactful but at Severe Risk. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute [Internet]; 2019. [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2019/10/title-x-family-planning-services-impactful-severe-risk. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost JJ, Zolna MR, Frohwirth L, Douglas-Hall A, Blades N, Mueller J, et al. Publicly Supported Family Planning Services in the United States: Likely Need, Availability and Impact, 2016 [Internet]. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute; 2019. [cited 2021 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/publicly-supported-FP-services-US-2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Title X Family Planning Program [Internet]. Washington, DC: Office of Population Affairs; 2021. 2 p. Available from: https://opa.hhs.gov/grant-programs/title-x-service-grants/about-title-x-service-grants [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, Curtis K, Glass E, Godfrey E, et al. Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep [Internet].2014. [cited 2021 Apr 17];63(Rr-04):1–54. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6304a1.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fowler CI, Ahrens KA, Decker E, Gable J, Wang J, Frederiksen B, et al. Patterns and trends in contraceptive use among women attending Title X clinics and a national sample of low-income women. Contracept X [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2021 Apr 4];1:100004. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7286153/ DOI: 10.1016/j.conx.2019.100004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Federal Register 42 CFR Part 59 Subpart A [HHS-OS-2018–0008]. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Oct 7. 16 p. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2020-title42-vol1/pdf/CFR-2020-title42-vol1-part59.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frederiksen B, Gomez I, Salganicoff A. Rebuilding Title X: New Regulations for the Federal Family Planning Program [Internet]. Washington, DC. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. [updated 2021 Nov 3; cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/rebuilding-title-x-new-regulations-for-the-federal-family-planning-program/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fowler CI, Gable J, Lasater B. Family Planning Annual Report: 2020 National Summary. Washington, DC: Office of Population Affairs; 2021. Sep [cited November 13]. 168 p. Available from: https://opa.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/title-x-fpar-2020-national-summary-sep-2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Title X Statutes, Regulations, and Legislative Mandates [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Office of Population Affairs; 2021. [cited 2021 Aug 2]. Available from: https://opa.hhs.gov/grant-programs/title-x-service-grants/title-x-statutes-regulations-and-legislative-mandates [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobel L, Rosenzweig C, Salganicoff A, Long M. Proposed Changes to Title X: Implications for Women and Family Planning Providers. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. Nov 21 [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/proposed-changes-to-title-x-implications-for-women-and-family-planning-providers/. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Measure CCW: Contraceptive care – all women ages 15–44. Washington, D.C.: Office of Population Affairs; 2019. [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://opa.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/2019-measure-specifications-ccw-for-opa-website.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeVoe JE, Gold R, Cottrell E, Bauer V, Brickman A, Puro J, et al. The ADVANCE network: accelerating data value across a national community health center network. J Am Med Inform Assoc [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2021 Mar 23];21(4):591–5. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4078289/ DOI: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Technical Appendix. To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 33.Darney B, Jacob R, Hoopes M, Rodriguez M, Hatch B, Marino M, et al. Evaluation of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act and Contraceptive Care in US Community Health Centers. JAMA Netw. Open [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Mar 20]. 3(6): e206874. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2766783. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Performance Measures Washington, DC: Office of Population Affairs; 2021. [updated 2021 Nov 23; cited 2021 Nov 23]. Available from: https://opa.hhs.gov/research-evaluation/title-x-services-research/contraceptive-care-measures [Google Scholar]

- 35.Effectiveness of Family Planning Methods. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2014. [cited Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/pdf/family-planning-methods-2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Ann Rev [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2021 May 3];40(1):105–25. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6532402/ DOI: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2019. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision [Internet]. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. [updated 2018 Sep 11; cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medicaid Family Planning Eligibility Expansions [Internet]. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute; 2021. [cited 2021 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/medicaid-family-planning-eligibility-expansions [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angier H, Hoopes M, Marino M, Huguet N, Jacobs EA, Heintzman J, et al. Uninsured Primary Care Visit Disparities Under the Affordable Care Act. Ann Fam Med [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2021 Jun 17];15(5):434–42. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5593726/ DOI: 10.1370/afm.2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garfield R, Damico A, Orgera K. The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. Jan 21 [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moseson H, Zazanis N, Goldberg E, Fix L, Durden M, Stoeffler A, et al. The Imperative for Transgender and Gender Nonbinary Inclusion: Beyond Women’s Health. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Jun 23];135(5). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7170432/ DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Appendix Exhibit A. To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 44.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Maguire F, Hulett D, Horsley K, Puffer M, Brindis C. Enhancing service delivery through Title X funding: Findings from California. Perspect Sex Reprod Health [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2021 Mar 22];44(4):262–9. Available from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0j82010c. DOI: 10.1363/4426212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Cross Riedel J, Menz M, Darney PD, Brindis CD. Onsite provision of specialized contraceptive services: does Title X funding enhance access? J Womens Health (Larchmt) [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2021 Mar 22];23(5):428–33. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4011460/ DOI: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boudreaux M, Xie L, Choi YS, Roby DH, Rendall MS. Changes to Contraceptive Method Use at Title X Clinics Following Delaware Contraceptive Access Now, 2008–2017. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Jun 23];110(8):1214–20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32552027/ doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park HY, Rodriguez MI, Hulett D, Darney PD, Thiel de Bocanegra H. Long-acting reversible contraception method use among Title X providers and non-Title X providers in California. Contraception [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2021 Apr 23];86(5):557–61. Available from: https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(12)00179-5/fulltext DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hale N, Khoury A, Smith M. Use of Highly Effective Reversible Contraception in Title X Clinics: Variation by Selected State Characteristics. Women’s Health Issues [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2021 Jun 25];28(4):289–96. Available from: https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(17)30500-5/fulltext DOI: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bornstein M, Carter M, Zapata L, Gavin L, Moskosky S. Access to long-acting reversible contraception among US publicly funded health centers. Contraception [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2021 Jun 23];97(5):405–10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29253581/ DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darney BG, Jacob RL, Hoopes M, Rodriguez MI, Hatch B, Marino M, et al. Evaluation of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act and Contraceptive Care in US Community Health Centers. JAMA Net Open [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Jun 23];3(6):e206874-e. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2766783 DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darney BG, Biel FM, Rodriguez MI, Jacob RL, Cottrell EK, DeVoe JE. Payment for Contraceptive Services in Safety Net Clinics: Roles of Affordable Care Act, Title X, and State Programs. Med Care [Internet]. 2020. [cited Jun 14];58(5):453–60. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7148195/ DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boniface ER, Rodriguez MI, Heintzman J, Knipper S, Jacobs R, Darney BG. Contraceptive provision in Oregon school-based health centers: Method type trends and the role of Title X. Contraception [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Aug 3];104(2):P206–210. Available from: https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(21)00092-5/fulltext DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diedrich JT, Klein DA, Peipert JF. Long-acting reversible contraception in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2021 Jul 25];216(4):364.e1-.e12. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002-9378(16)46213-7 DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mestad R, Secura G, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Acceptance of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods by adolescent participants in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Contraception [Internet]. 2011. [cited 2021 Jul 25];84(5):493–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3505875/ DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy MK, Stoffel C, Nolan M, Haider S. Interdependent Barriers to Providing Adolescents with Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Qualitative Insights from Providers. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2021 Jun 14];29(5):436–42. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4974172/ DOI: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.01.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bryson A, Koyama A, Hassan A. Addressing long-acting reversible contraception access, bias, and coercion: supporting adolescent and young adult reproductive autonomy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021. [cited 2021 Nov 17];33(4):345–353. Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33797464/ DOI: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000001008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Higgins JA, Kramer RD, Ryder KM. Provider Bias in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) Promotion and Removal: Perceptions of Young Adult Women. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2016. Nov [cited 2021 Apr 23];106(11):1932–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27631741/ DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspect Sex Reprod Health [Internet]. 2014. May 23 [cited 2021 Jun 8];46(3):171–5. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4167937/ DOI: 10.1363/46e1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Federal Title X Training Requirements Summary [Internet]. Kansas City, MO: Family Planning National Training Center; 2021. [updated 2021 May 5; cited 2021 Nov 17]. 2p. Available from: https://rhntc.org/sites/default/files/resources/rhntc_fed_training_reqs_2021-02-16.pdf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gavin L, Pazol K, Ahrens K. Update: Providing Quality Family Planning Services - Recommendations from CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2017. Dec 22 [cited May 4];66(50):1383–5. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6650a4.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raidoo S, Kaneshiro B. Contraception counseling for adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynec [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2021 Jun 13];29(5):310–315. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28682927/ DOI: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: Guidance and recommendations. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. p34. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/102539/9789241506748_eng.pdf;jsessionid=39663580535CCDA28104DEA641E480E4?sequence=1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fuentes L, Ingerick M, Jones R, Lindberg L. Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Reports of Barriers to Confidential Health Care and Receipt of Contraceptive Services. J Adolesc Health [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2021 Jun 23];62(1):36–43. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5953199/ DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coleman-Minahan K, Hopkins K, White K. Availability of Confidential Services for Teens Declined After the 2011–2013 Changes to Publicly Funded Family Planning Programs in Texas. J Adolesc Health [Internet]. 2020. [cited Jun 23];66(6):719–24. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7263963/ DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dawson R. Trump Administration’s Domestic Gag Rule Has Slashed the Title X Network’s Capacity by Half [Internet]. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute; 2020. [cited 2021 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2020/02/trump-administrations-domestic-gag-rule-has-slashed-title-x-networks-capacity-half?utm_source=Guttmacher+Email+Alerts&utm_campaign=3646e4086e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_02_05_06_40_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_9ac83dc920-3646e4086e-244280589. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wood S, Strasser J, Sharac J, Wylie J, Tahao-Chi T, Rosenbaum S, et al. Community Health Centers and Family Planning an Era of Policy Uncertainty [Internet]. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. [updated 2018 Mar 15; cited 2021 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/community-health-centers-and-family-planning-in-an-era-of-policy-uncertainty/. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hasstedt K. Federally Qualified Health Centers: Vital Sources of Care, No Substitute for the Family Planning Safety Net [Internet]. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute; 2017. [cited 2021 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2017/05/federally-qualified-health-centers-vital-sources-care-no-substitute-family-planning [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frederiksen B, Salganicoff A, Sobel L, Gomez I. Key Elements of the Biden Administration’s Proposed Title X Regulation [Internet]. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. [updated 2021 May 5; cited 2021 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/key-elements-of-the-biden-administrations-proposed-title-x-regulation/. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frederiksen B, Gomez I, Salganicoff A, Sobel L. Potential Scenarios for Issuing New Title X Regulations [Internet]. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. [updated 2021 Mar 18; cited 2021 May 4]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/potential-scenarios-for-issuing-new-title-x-regulations/. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.