Abstract

A dynamic field of study has emerged involving long-range electron transport by extracellular filaments in anaerobic bacteria, with Geobacter sulfurreducens being used as a model system. The interest in this topic stems from the potential uses of such systems in bioremediation, energy generation and new bio-based nanotechnology for electronic devices. These conductive extracellular filaments were originally thought, based upon low resolution observations of dried samples, to be type IV pili (T4P). However, the recently published atomic structure for the T4P from G. sulfurreducens, obtained by cryo-electron microscopy, is incompatible with the numerous models that have been put forward for electron conduction. As with all high resolution structures of T4P, the G. sulfurreducens T4P structure shows a partial melting of the α-helix that substantially impacts the aromatic residue positions such that they are incompatible with conductivity. Furthermore, new work using high resolution cryo-EM shows that conductive filaments thought to be T4P are actually polymerized cytochromes, with stacked heme groups forming a continuous conductive wire, or extracellular DNA. Recent atomic structures of three different cytochrome filaments from G. sulfurreducens suggest that such polymers evolved independently on multiple occasions. The expectation is that such polymerized cytochromes may be found emanating from other anaerobic organisms.

Keywords: nanowires, type IV pili, Geobacter, cryo-EM

Overview

While most respirations use soluble electron acceptors such as oxygen or nitrate, some anaerobic bacteria are capable of respiration using insoluble metals, minerals, electrodes and even other cells as electron acceptors. Geobacter sulfurreducens has been intensively studied due to its ability to transfer electrons to extracellular acceptors that can be many microns from the cell and through thick biofilms. Over 15 years ago, extracellular conductive filaments extending from Geobacter were found to be required for this long-range electron transport [1]. Early data suggested that these filaments were type IV pili (T4P) [1–6]: mutations disrupting T4P production disrupted Geobacter electron transport [1], and mutations in the pilA gene encoding the T4P major pilin, which substituted aromatic residues thought to mediate electron transport, altered the apparent conductivity in these extracellular filaments [7]. Thus, extracellular conductivity in G. sulfurreducens was attributed to T4P and the e-pili hypothesis has since been echoed in hundreds of papers. Major technological developments in cryo-EM [8–11] have resulted in an atomic structure for the Geobacter type IV pilus [12,13] (Fig. 1), which is incompatible with the models for electron transport in e-pili. Furthermore, cryo-EM of the G. sulfurreducens conductive filaments reveal that these are in fact cytochrome filaments and not T4P. The atomic structures of these cytochrome filaments provide a plausible mechanism for electron transport [13–15]. Together, these studies have completely reshaped our understanding in this field.

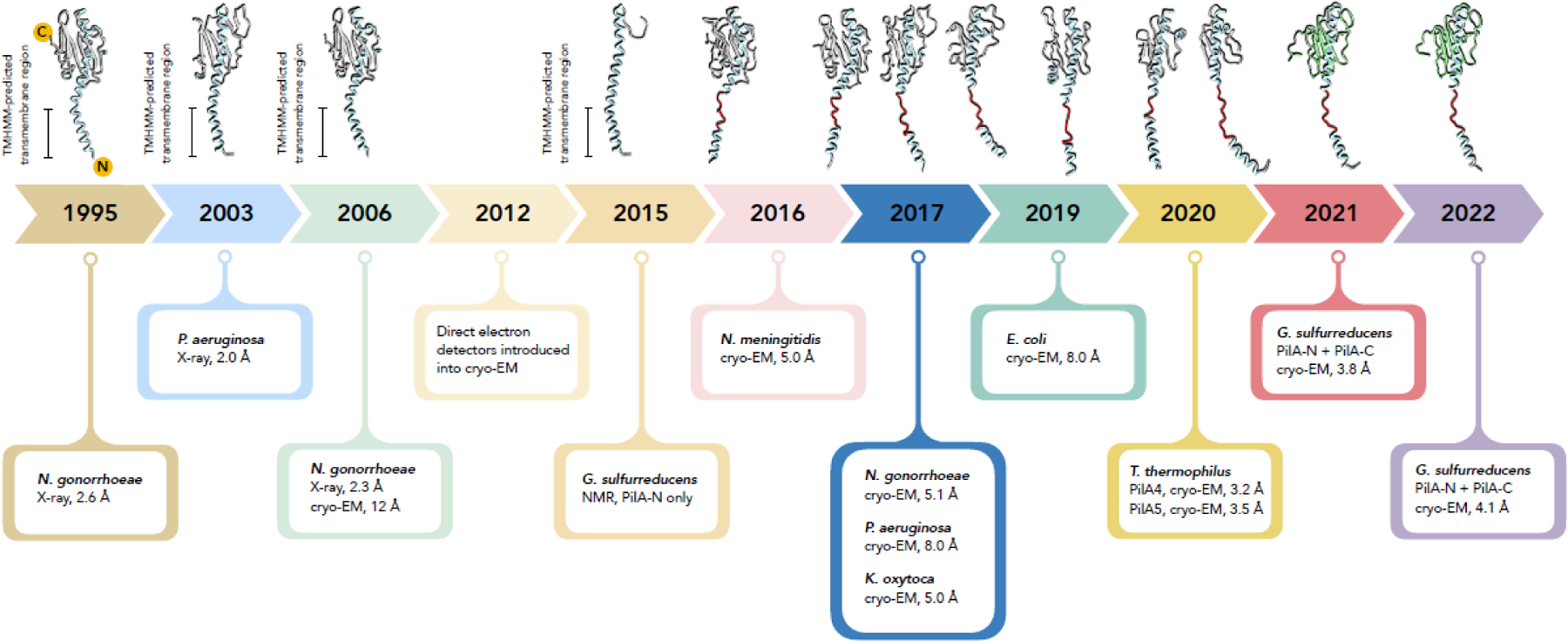

Figure 1.

A timeline for structures of bacterial type IV pilin and pili. The first crystal structure of a detergent solubilized type IV pilin was in 1995. In 2006 a higher resolution 2.3 Å crystal structure was combined with a low resolution cryo-EM reconstruction of a pilus to generate a filament model. A structure of detergent solubilized G. sulfurreducens PilA-N protein was determined by NMR in 2015, showing that it looks the same as the N-terminal portion of other t4p, but lacking a globular C-terminal domain. The field of cryo-EM was transformed starting about 2012 with the introduction of direct electron detectors, making near-atomic resolution routinely possible. Direct electron detectors led to seven atomic models for T4P. For all these filament structures, the cryo-EM map reveals a partially melted N-terminal helix (red). In 2021 a cryo-EM reconstruction of filaments produced when PilA-N and PilA-C are overexpressed in G. sulfurreducens showed that these two chains form the subunit in the pilus. While this is the first example of a two-polypeptide pilin subunit, the G. sulfurreducens pilus is otherwise unexceptional, having the canonical T4P structure, including the partially melted N-terminal helix. In 2022 the structure of a naturally expressed G. sulfurreducens pilus showed that it was indistinguishable from the overexpressed one.

The historical notion that microbial nanowires are composed of T4P

G. sulfurreducens and other anaerobic soil bacteria rely on long range electron transport to carry out respiration. The presence of extracellular filaments in Geobacter cultures, and of T4P genes in the Geobacter genome led researchers to propose that T4P mediate long range charge transfer [1]. T4P are thin filaments of 6–8 nm in diameter, with lengths of microns or more [16], and thus able to connect bacteria with distant cells, surfaces or other electron acceptors. While proteins are known to be poor electron conductors [17], T4P have conserved aromatic residues that, it was argued [18], could be positioned along the inner length of the pilus such that electrons could hop from one aromatic side chain to the next. This is the “e-pilus” hypothesis [1]. In the absence of a structure for the polymerized G. sulfurreducens T4P, computational models were generated to predict the e-pilus structure and its electron transport mechanism. However, these models relied on two assumptions, which have since proved to be incorrect. One is that the G. sulfurreducens e-pilus is built entirely from the PilA-N gene product, which we now know to be less than one half of the pilin subunit. The second is that the secondary structure bearing the conserved aromatic residues responsible for electron transfer is a continuous α-helix within the e-pilus. Cryo-EM has revealed the true structure of the G. sulfurreducens T4P [12,13], which is incompatible with electron conductivity.

All type IV pilins share a common architecture, with a hydrophobic N-terminal α-helical domain and a globular C-terminal domain (Fig. 1). While many structures of both the T4P monomer and polymer show a largely β-stranded globular C-terminal domain [16], a recent structure of a type IV pilin from Gram-positive bacteria has shown that the C-terminal domain can be purely α-helical [19]. The sequence of the N-terminal hydrophobic domain of the pilin is highly conserved, while the C-terminal globular domain is highly variable. It has been suggested that archaeal T4P and flagellar filaments are homologs of bacterial T4P [20,21], but a more accurate statement, based upon a number of recent atomic structures for these archaeal filaments, is that the N-terminal domain alone and not the entire pilin of archaeal filaments is a homolog of the N-terminal domain in the bacterial proteins. This is because the C-terminal domains in the archaeal T4P and flagellar filaments have an Ig-fold and show no homology to any C-terminal domains in the bacterial T4P, suggesting that both the bacterial and archaeal T4P may have resulted from gene fusions, combining these two domains.

The G. sulfurreducens PilA protein was purported in many early papers [22–25] to be the product of the pilA-N gene, which almost entirely lacks the globular C-terminal domain that is present in all T4P filaments that have been solved at high resolution [26] (Fig. 1). We now know that there are two PilA genes in G. sulfurreducens, pilA-N and pilA-C, that together encode a PilA-N/C subunit that contains two chains [12]. A truncated pilin composed of only the PilA-N chain, if it could polymerize on its own, would produce a pilus much thinner than the 6–8 nm T4P filaments seen for other bacteria. Early identification of Geobacter filaments as T4P used atomic force microscopy (AFM) [1], a very low-resolution imaging method susceptible to many artifacts [27] due to the dehydration of the Geobacter samples. A published electron micrograph of negatively stained “pili” from G. sulfurreducens in Malvankar et al. [18] has now been analyzed to show that these are not in fact T4P but are instead polymers of the cytochrome OmcS [13].

A preprint claims that 3 nm diameter filaments from the extracellular fraction of G. sulfurreducens imaged by cryo-EM were formed from PilA [28] but the published paper (Filman et al.) is less certain, stating that these filaments were “presumably” composed of PilA [29]. After almost four years, the electron micrographs used in Filman et al. have been deposited in a public repository (https://empiar.org/11228). These thinner filaments are quite sparse and the published micrograph in Filman et al. showing two thin filaments was not representative. Out of 538 good micrographs, only 19 contained images of these filaments, typically only one thin filament for each of these 19 micrographs, although the images are filled with OmcS filaments. This contrasts greatly with the assertion that putative PilA filaments account for 90% of the extracellular filaments expressed by Geobacter sulfurreducens, as judged by AFM [30]. While it is impossible to be conclusive given the very sparse data set, our best estimate is that these filaments are DNA, as observed in other Geobacter sulfurreducens preparations [12,13].

In the absence of empirical structures for the putatively conductive e-pili, a number of atomic models were proposed for the G. sulfurreducens filament, built from only the PilA-N chain [18,25,31–33], as well an atomic model for the Shewanella oneidensis T4P [32] that was also suggested to be conductive. A hypothetical filament formed from the truncated G. sulfurreducens PilA-N pilin is likely to be extremely hydrophobic and insoluble [12,13] as its many hydrophobic residues would be exposed to the aqueous environment. An experimental high resolution structure of a 3 nm Geobacter filament comprised of the PilA-N gene product alone has never been reported. In almost all of these models, the explanation for the hypothetical conductivity is electron hopping via aromatic side chains on the N-terminal α-helix in PilA, which are stacked in these filament models. All these models are built using an early cryo-EM reconstruction (Fig. 1) of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae T4P [34] or a computational model of the P. aeruginosa pilus [35]. The N. gonorrhoeae T4P model was built by docking a crystal structure of the detergent-solubilized monomeric pilin [36] into a 12 Å resolution cryo-EM reconstruction of the polymeric type IV pilus [34]. Importantly, this low resolution reconstruction did not resolve the N-terminal α-helices in the filament core, which were modelled as the curved but continuous α-helices seen in the crystal structure. With the advent of high-resolution cryo-EM, it was subsequently shown that the N-terminal helix is partially melted in the assembled filament for N. gonorrhoeae as well as for the closely related Neisseria meningitidis T4P [37,38] (Fig. 1). A very similar melting of the N-terminal α-helix has been observed in all subsequent cryo-EM structures of T4P: in the P. aeruginosa pilus [37], the Klebsiella oxytoca T2SS PulG endopilus (previously called pseudopilus) [39], the Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) PpdD T4P [40], and two distinctly different T4P from T. thermophilus [41], suggesting that it is a universal feature of all bacterial T4P.

The very hydrophobic N-terminal half of the N-terminal domain is actually a transmembrane α-helix (Fig. 1) that is embedded in the bacterial inner membrane before polymerization of T4P. Thus, the continuous N-terminal α-helix observed in the crystal structure likely represents the membrane-anchored form of the protein. The melting of the α-helix is thought to occur to allow subunit packing within the pilus filament.

The cryo-EM structure of the G. sulfurreducens T4P is incompatible with electron transfer

A cryo-EM structure of the G. sulfurreducens T4P was recently published, revealing features that call into question its role in electron conduction. First, these pili are not 3 nm filaments comprised of the 60 amino acid PilA gene product, but are in fact 6.5 nm diameter filaments containing two chains, the products of pilA, now more aptly called pilA-N, plus the neighboring pilA-C gene [12,13]. PilA-N and -C associate to form a canonical pilin structure with a hydrophobic N-terminal α-helix and a globular β-sheet C-terminal domain. The presence of the two chains is consistent with the conclusion from archaea that the bacterial type IV pilins may have resulted from a gene fusion. It is also consistent with the observation that the pilin C-terminal domain in at least one Gram-positive bacterium lacks homology with those of Gram-negative bacteria [19]. Second, as seen for all other T4P, the N-terminal α-helix of the G. sulfurreducens PilA-N/C filaments is partially melted (Fig. 1) positioning the conserved aromatic side chains such that they could not possibly facilitate electron hopping along the filament. Consistent with this observation, the PilA-N/C filaments were shown to be non-conductive [12]. The G. sulfurreducens T4P cryo-EM structure was obtained from extracellular filaments produced when the pilA-N and pilA-C genes were overexpressed [12]. It has been argued that these filaments, not previously reported, are artifacts of overexpression [42]. This is a rather unusual argument, as most crystallographic structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank have come from overexpressed protein. But in a second paper, amino acid substitutions in another protein (the cytochrome OmcS) that were expected to disrupt electron transport led to the appearance of naturally expressed PilA-N/C filaments, as well as filaments formed from another cytochrome, OmcE [13].

If the G. sulfurreducens T4P is in fact a 6.5 nm filament, what is the identity of the ~ 3 nm filaments in the dried samples imaged by AFM [12,13]? It is possible that these are either the polymerized cytochrome OmcZ [15,43] or extracellular DNA molecules (eDNA), known to be highly abundant in bacterial biofilms [44–46]. In fact, cryo-EM of Geobacter preparations has now revealed the ~ 36 Å pitch and double-helical structure for some ~3 nm filaments [12,13], consistent with eDNA rather than PilA-N T4P, as proposed based upon AFM observations (Fig. 2). It is also most likely that these filaments are the highly abundant OmcS polymers, as a recent paper described such OmcS filaments as having a 3.5 nm diameter when measured by AFM of dried samples [43].

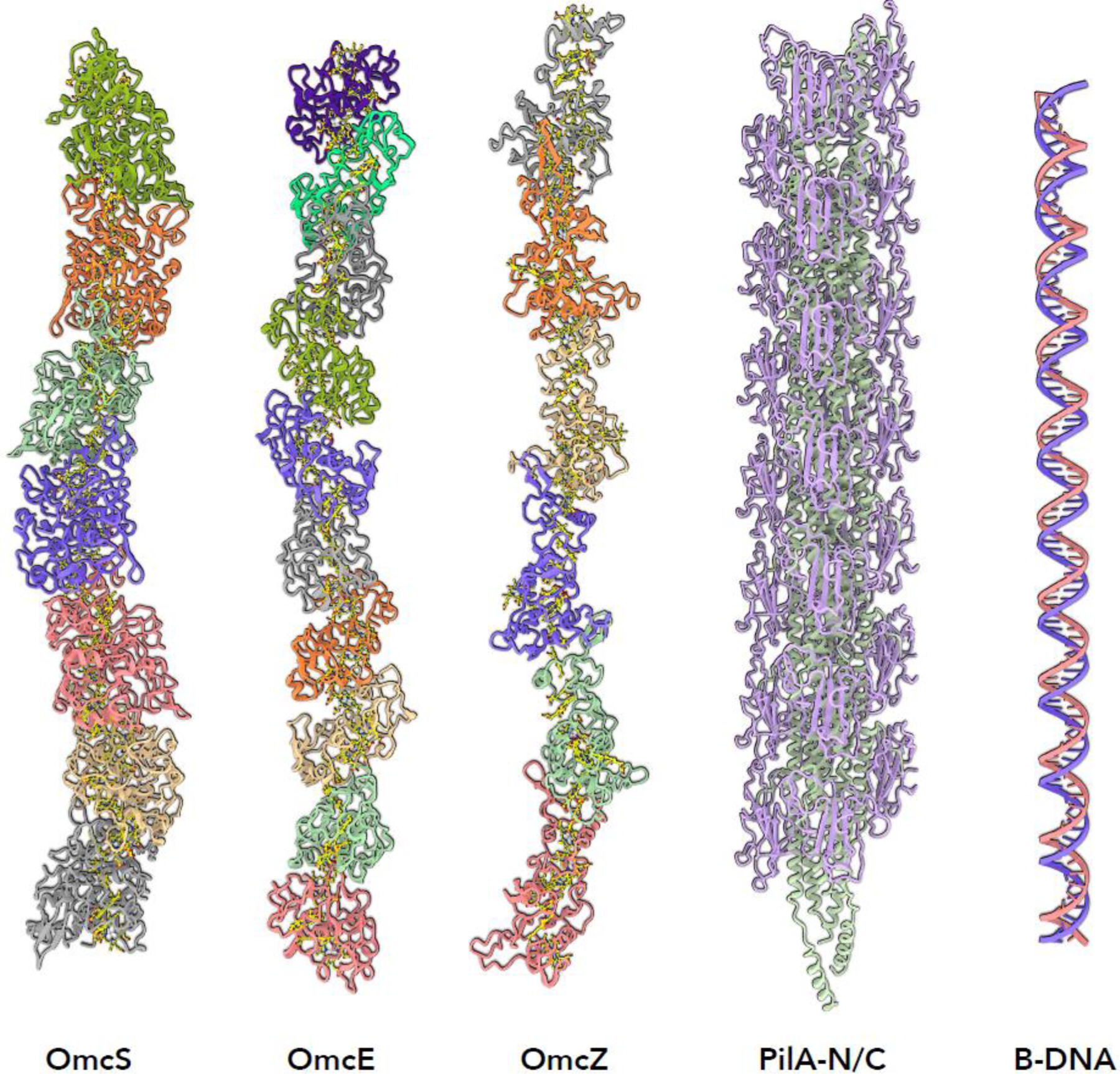

Figure 2.

The only G. sulfurreducens extracellular filaments observed thus far by high resolution cryo-EM. The multi-heme cytochrome filaments OmcS, OmcE and OmcZ are the microbial nanowires that have been mistakenly called e-pili. The actual type IV pilus from G. sulfurreducens has a subunit containing two polypeptide chains, PilA-N and PilA-C. These pili are normally not seen extracellularly. What is frequently seen in G. sulfurreducens extracellular preparations are thin filaments that have been shown to be DNA.

Recently discovered cytochrome polymers

If T4P are not capable of long range extracellular electron transport, how does this occur in G. sulfurreducens and other anaerobic bacteria? A major breakthrough in our understanding of bacterial electron conduction occurred when high resolution cryo-EM was first used to reconstruct the extracellular G. sulfurreducens filaments [14]. It was found that these filaments are polymers of a hexaheme cytochrome, OmcS. Several earlier papers had actually suggested an important role for this cytochrome [47–49]. The bound hemes in OmcS form a continuous chain through the filaments that can be many microns long, providing a mechanism for long range electron transport [18]. The details of how the electrons are conducted along the heme chain, such as whether there is a quantum cloud of electrons due to their delocalization [50], hopping of electrons, or coherent transport [51] still remains to be determined. These different conduction models are all consistent with the stacked heme structures in the cytochrome filaments, while none of these models are consistent with the spacing of aromatic residues in the partially melted helix of the PilA-N/C filament.

Multiple cytochromes have been previously observed to stack together, such as in the MtrABC complex [52,53], but cytochrome filaments have never been observed previously. What is novel in the OmcS filament is that a His residue in one subunit coordinates a heme in an adjacent subunit, forming a seamless conductive heme chain, with the surrounding protein acting as an insulator [53]. Knowing the structure of the OmcS filament, it was a simple matter to analyze previously published images of “e-pili” [18] and show that they are actually OmcS filaments [13].

As mentioned, one of the foundations for the hypothesis that the conductive extracellular filaments in Geobacter were made of PilA involved genetic manipulation of PilA. What we now understand is that there are complex regulatory interactions among different gene products involved in long range electron transport in Geobacter. Mutations in pilA have now been shown to decrease the production of OmcS and increase the production of a different filament, composed of another cytochrome, OmcZ [43]. OmcZ is an octaheme cytochrome, and OmcZ filaments have even greater apparent conductivity than OmcS [43]. An atomic structure for the OmcZ filament, solved using cryo-EM, can explain this much greater apparent conductivity due to a branched, rather than linear, heme chain in the filament, resulting in one surface-exposed heme in every subunit, creating an array of electron paths rather than a single linear path from one end of the filament to the other [15]. Notably, mutations in omcS designed to disrupt the electron transfer chain result in the appearance of a third cytochrome polymer, formed from OmcE [13].

What can we learn from comparing these three cytochrome polymers? One of the most striking observations was that while OmcS is a hexaheme protein, and OmcE is a tetraheme protein, the four hemes in OmcE can be superimposed on the first four hemes in OmcS, revealing a remarkable degree of similarity. While there is no apparent sequence or structural similarity between the OmcS and OmcE proteins (in fact, the root mean square deviation between the two chains is ~ 19 Å, what one might expect from two random proteins), 28 backbone atoms in one can be aligned to the corresponding atoms in the other with only 1.1 Å rms deviation [13], which is almost at the level of experimental error. Not coincidentally, these are the backbone atoms involved in the coordination of the heme groups. The picture that has emerged is that the role of the cytochrome proteins is to coordinate the hemes, position them so as to form a chain, and to insulate the heme chain. Providing these criteria are met, the intervening sequences between the heme-coordinating motifs are free to diverge in both sequence and structure. This conservation of a heme chain framework suggests that OmcE and OmcS have a common ancestor, but one would never detect this homology with sequence or even structure-based searches.

The octaheme OmcZ filament differs from OmcS and OmcE filaments, such as having a branched, rather than linear, arrangement of hemes. In addition, all of the hemes in OmcZ are coordinated by histidine residues located within the same subunit. The large differences between OmcZ, on the one hand, and OmcE and OmcS, on the other, suggest that polymers of multi-heme cytochromes may have arisen independently at least twice in evolution. Since the G. sulfurreducens genome encodes for more than 75 multi-heme cytochromes, we suspect that yet other cytochrome polymers might be formed by this organism under different conditions.

The identification of three distinct extracellular cytochrome filaments capable of conducting electrons, together with the high resolution structure of the non-conductive Geobacter T4P, overwhelmingly support a model in which long range electron transport in G. sulfurreducens is mediated by cytochrome filaments and not by T4P.

Role of Type IV pili in Geobacter long range electron transport

While it is clear that PilA is involved in long-range electron transport in Geobacter, several studies have suggested that it has a role in nanowire secretion, but does not itself, under normal conditions form the extracellular conductive filaments [54,55]. This was previously stated by Lovley inter alia in 2009 [56]: “These results suggest that pili may not be directly involved in the homogenous ET [electron transfer] (step 3), owing to conductivity of the ΔpilA biofilm, but that pili may play a structural role in formation of thick biofilms and in localization of extracellular c-type cytochromes”. Such a structural role would explain the requirement for these T4P in expression of extracellular Geobacter cytochrome filaments. Most probably, PilA-N and PilA-C together form a periplasmic filament analogous to the Type II secretion endopilus [57], which is necessary for both the assembly and export of these cytochrome polymers [12,14]. While these short filaments confined to the periplasmic space have been called pseudopili, we prefer the term endopili, just as the periplasmic flagellar filament in spirochetes has been referred to as an endoflagellum [58]. Endopili, by definition, are not normally extracellular, but are contained within the periplasmic space and probably function as a dynamic piston or Archimedean screw in transporting substrates through the periplasmic space and into the extracellular environment [39]. With overexpression of a major endoopilin such as PulG, endopili can be found as extracellular filaments [39]. Understanding the exact role that PilA-N/C filaments play in the expression of cytochrome filaments will be an important topic for future research.

Conclusion

The study of microbial long-range electron transport has been of great interest for many reasons, including potential uses in bioremediation, energy generation and nanotechnology. Incredible advances in cryo-EM over the past 10 years [8–11] have transformed structural biology, and reaching a near-atomic level of resolution when studying macromolecular complexes and filaments has become routine. In fact, these advances have extended beyond proteins to assemblies of small peptides [59]. This means that unambiguous identification of extracellular filaments can be made based upon their atomic structures, as opposed to characterization of these filaments by their diameters. We have also learned for G. sulfurreducens that genetic manipulation can be problematic, as it is now clear that mutations in one protein can change the expression levels of other proteins [13,43]. Therefore, phenotype cannot be simply related to genotype. With the new high-resolution results, it has become clear that long range extracellular electron conduction in G. sulfurreducens occurs via cytochrome filaments and not e-pili, prompting a reconsideration of most previous literature in this field. Given the ubiquity of multi-heme cytochromes, we have a reasonable expectation that cytochrome filaments will prove to be rather widespread in biology, and not limited to G. sulfurreducens.

Outstanding Questions:

How is electricity actually conducted in cytochrome-stacked nanowires: electron hopping or electron quantum cloud?

Are there other long range electron transfer mechanisms in biological systems in addition to stacked multiheme cytochromes?

How are cytochrome stacked heme nanowires assembled?

What is the role of type IV pili in cytochrome nanowire assembly?

Do other Geobacter species and other microbes also express cytochrome heme-stacked nanowires?

Highlights.

Early studies using low resolution imaging methods and dehydrated samples erroneously identified extracellular Geobacter nanowires as type IV pili (T4P).

Models for conductive T4P used an incomplete pilin subunit, containing only PilA-N, and were based on crystal and NMR structures of monomeric T4P. It is now known that when T4P subunits polymerize there is a significant conformational change.

Cryo-EM structures of the Geobacter T4P show that its pilin subunit contains two polypeptide chains, PilA-N plus PilA-C, and that the aromatic residues in PilA-N are not close enough to each other to permit electron hopping.

High resolution structures of three different extracellular Geobacter filaments reveal cytochrome polymers with stacked hemes that form an insulated chain capable of conducting electrons.

Analysis of Geobacter extracellular preparations reveal putative T4P nanowires to be either DNA or filaments of the cytochrome OmcZ.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH GM22510 (E.H.E.) and GM138756 (F.W.) and by a New Frontiers in Science Fund grant NFRFE-2019–00757 (L.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Reguera G et al. (2005) Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435, 1098–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malvankar NS et al. (2012) Lack of cytochrome involvement in long-range electron transport through conductive biofilms and nanowires of Geobacter sulfurreducens. Energy & Environmental Science 5, 8651–8659 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malvankar NS and Lovley DR (2014) Microbial nanowires for bioenergy applications. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 27C, 88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malvankar NS and Lovley DR (2012) Microbial nanowires: a new paradigm for biological electron transfer and bioelectronics. ChemSusChem 5, 1039–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovley DR (2012) Long-range electron transport to Fe(III) oxide via pili with metallic-like conductivity. Biochemical Society transactions 40, 1186–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovley DR (2012) Electromicrobiology. Annu Rev Microbiol 66, 391–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adhikari RY et al. (2016) Conductivity of individual Geobacter pili. Rsc Advances 6, 8354–8357 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egelman EH (2016) The Current Revolution in Cryo-EM. Biophys. J 110, 1008–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai XC et al. (2015) How cryo-EM is revolutionizing structural biology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhlbrandt W (2014) Cryo-EM enters a new era. eLife 3, e03678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhlbrandt W (2014) Biochemistry. The resolution revolution. Science 343, 1443–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu Y et al. (2021) Structure of Geobacter pili reveals secretory rather than nanowire behaviour. Nature 597, 430–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang F et al. (2022) Cryo-EM structure of an extracellular Geobacter OmcE cytochrome filament reveals tetrahaem packing. Nat Microbiol 7, 1291–1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang F et al. (2019) Structure of Microbial Nanowires Reveals Stacked Hemes that Transport Electrons over Micrometers. Cell 177, 361–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F et al. (2022) Structure of Geobacter OmcZ filaments suggests extracellular cytochrome polymers evolved independently multiple times. eLife 11, e81551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig L et al. (2019) Type IV pili: dynamics, biophysics and functional consequences. Nature reviews. Microbiology 17, 429–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zotti LA and Cuevas JC (2018) Electron Transport Through Homopeptides: Are They Really Good Conductors? ACS Omega 3, 3778–3785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malvankar NS et al. (2015) Structural basis for metallic-like conductivity in microbial nanowires. mBio 6, e00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheppard D et al. (2020) The major subunit of widespread competence pili exhibits a novel and conserved type IV pilin fold. J Biol Chem 295, 6594–6604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayley DP and Jarrell KF (1998) Further evidence to suggest that archaeal flagella are related to bacterial type IV pili. J.Mol.Evol 46, 370–373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faguy DM et al. (1994) Molecular analysis of archael flagellins: similarity to the type IV pilin-transport superfamily widespread in bacteria. Can J Microbiol 40, 67–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen Y et al. (2010) Structural characterization of novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilins. J. Mol. Biol 395, 491–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding Y-HR et al. (2008) Proteome of Geobacter sulfurreducens grown with Fe(III) oxide or Fe(III) citrate as the electron acceptor. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1784, 1935–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lebedev N et al. (2015) On the electron transfer through Geobacter sulfurreducens PilA protein. Journal of Polymer Science Part B-Polymer Physics 53, 1706–1717 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reardon PN and Mueller KT (2013) Structure of the type IVa major pilin from the electrically conductive bacterial nanowires of Geobacter sulfurreducens. J Biol Chem 288, 29260–29266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egelman EH (2017) Cryo-EM of bacterial pili and archaeal flagellar filaments. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 46, 31–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kemp AD et al. (2012) Effects of tissue hydration on nanoscale structural morphology and mechanics of individual Type I collagen fibrils in the Brtl mouse model of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J. Struct. Biol 180, 428–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filman DJ et al. (2018) Structure of a cytochrome-based bacterial nanowire. bioRxiv, 492645 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filman DJ et al. (2019) Cryo-EM reveals the structural basis of long-range electron transport in a cytochrome-based bacterial nanowire. Commun Biol 2, 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X et al. (2021) Direct observation of electrically conductive pili emanating from Geobacter sulfurreducens. mBio, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shu C et al. (2017) Predicting and Interpreting the Structure of Type IV Pilus of Electricigens by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Molecules 22, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorgel M et al. (2015) High-resolution structure of a type IV pilin from the metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. BMC Struct Biol 15, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feliciano GT et al. (2015) Structural and functional insights into the conductive pili of Geobacter sulfurreducens revealed in molecular dynamics simulations. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP 17, 22217–22226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Craig L et al. (2006) Type IV pilus structure by cryo-electron microscopy and crystallography: implications for pilus assembly and functions. Molecular Cell 23, 651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig L et al. (2004) Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat.Rev.Microbiol 2, 363–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parge HE et al. (1995) Structure of the fibre-forming protein pilin at 2.6 A resolution. Nature 378, 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang F et al. (2017) Cryoelectron microscopy reconstructions of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Neisseria gonorrhoeae type IV pili at sub-nanometer resolution. Structure 25, 1423–1435 e1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolappan S et al. (2016) Structure of the Neisseria meningitidis Type IV pilus. Nat. Commun 7, 13015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez-Castilla A et al. (2017) Structure of the calcium-dependent type 2 secretion pseudopilus. Nat Microbiol 2, 1686–1695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bardiaux B et al. (2019) Structure and Assembly of the Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli Type 4 Pilus. Structure 27, 1082–1093 e1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neuhaus A et al. (2020) Cryo-electron microscopy reveals two distinct type IV pili assembled by the same bacterium. Nat. Commun 11, 2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lovley DR (2022) On the Existence of Pilin-Based Microbial Nanowires. Front Microbiol 13, 872610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yalcin SE et al. (2020) Electric field stimulates production of highly conductive microbial OmcZ nanowires. Nature Chemical Biology 16, 1136–+ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodman SD and Bakaletz LO (2022) Bacterial Biofilms Utilize an Underlying Extracellular DNA Matrix Structure That Can Be Targeted for Biofilm Resolution. Microorganisms 10, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campoccia D et al. (2021) Extracellular DNA (eDNA). A Major Ubiquitous Element of the Bacterial Biofilm Architecture. Int J Mol Sci 22, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devaraj A et al. (2019) The extracellular DNA lattice of bacterial biofilms is structurally related to Holliday junction recombination intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 116, 25068–25077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehta T et al. (2005) Outer membrane c-type cytochromes required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxide reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 71, 8634–8641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qian X et al. (2011) Biochemical characterization of purified OmcS, a c-type cytochrome required for insoluble Fe(III) reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1807, 404–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim B-C et al. (2005) OmcF, a putative c-Type monoheme outer membrane cytochrome required for the expression of other outer membrane cytochromes in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Journal of bacteriology 187, 4505–4513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakagawa H et al. (1994) Cytochrome c electronic structure characterization toward the analysis of electron transfer mechanism. J Biochem 115, 891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eshel Y et al. (2020) Coherence-assisted electron diffusion across the multi-heme protein-based bacterial nanowire. Nanotechnology 31, 314002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edwards MJ et al. (2020) Role of multiheme cytochromes involved in extracellular anaerobic respiration in bacteria. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society 29, 830–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edwards MJ et al. (2020) The Crystal Structure of a Biological Insulated Transmembrane Molecular Wire. Cell 181, 665–673.e610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ye Y et al. (2022) Dissecting the Structural and Conductive Functions of Nanowires in Geobacter sulfurreducens Electroactive Biofilms. mBio, e0382221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu X et al. (2018) Syntrophic growth with direct interspecies electron transfer between pili-free Geobacter species. The ISME Journal 12, 2142–2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richter H et al. (2009) Cyclic voltammetry of biofilms of wild type and mutant Geobacter sulfurreducens on fuel cell anodes indicates possible roles of OmcB, OmcZ, type IV pili, and protons in extracellular electron transfer. Energy & Environmental Science 2, 506–516 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Korotkov KV et al. (2012) The type II secretion system: biogenesis, molecular architecture and mechanism. Nature reviews. Microbiology 10, 336–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.San Martin F et al. (2022) Diving into the complexity of the spirochetal endoflagellum. Trends in microbiology, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pieri L et al. (2022) Atomic structure of Lanreotide nanotubes revealed by cryo-EM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 119, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]