Abstract

Introduction:

Many in the U.S. are not up to date with cancer screening. This systematic review examined the effectiveness of interventions engaging community health workers (CHWs) to increase breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening.

Methods:

Authors identified relevant publications from previous Community Guide systematic reviews of interventions to increase cancer screening (1966 through 2013) and from an update search (January 2014 to November 2021). Studies written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals were included if they assessed interventions implemented in high-income countries; reported screening for breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer; and engaged CHWs to implement part or all of the interventions. CHWs needed to come from, or have close knowledge of, the intervention community.

Results:

The review included 76 studies. Interventions engaging CHWs increased screening use for breast (median increase of 11.5 percentage points [pct pts]; interquartile interval [IQI] 5.5 to 23.5), cervical (median increase of 12.8 pct pts; IQI 6.4 to 21.0), and colorectal cancers (median increase of 10.5 pct pts; IQI 4.5 to 17.5). Interventions were effective whether CHWs worked alone or as part of a team. Interventions increased cancer screening independent of race or ethnicity, income, or insurance status.

Discussion:

Interventions engaging CHWs are recommended by the Community Preventive Services Task Force to increase cancer screening. These interventions are typically implemented in communities where people are underserved to improve health and can enhance health equity. Further training and financial support for CHWs should be considered to increase cancer screening uptake.

INTRODUCTION

Breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers accounted for more than 419,000 new cancer diagnosis and 98,000 deaths in 2019.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for these cancers among age- and sex-appropriate populations at regular intervals.2–4 Screening, with appropriate follow-up for abnormal test results, reduces cancer-related morbidity and mortality.2–4 Screening rates in 20185 were below Healthy People 2020 targets,6 especially for people from some racial and ethnic groups and people with lower incomes or who are uninsured.7 Disparities in screening can lead to increases in late-stage cancer diagnoses and mortality among these populations.8,9

Interventions engaging community health workers (CHWs) have increasingly been used to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate healthcare services to under-resourced communities.10,11 CHWs are trained frontline health workers who serve as a bridge between communities where people are underserved and healthcare systems. They are from, or have a close understanding of, the community served.12 They often receive on-the-job training and work without professional degrees or titles.13 CHWs may be paid or serve as volunteers,14 and they may work independently or as part of a team that includes other healthcare professionals.15

Interventions engaging CHWs have shown effectiveness in improving health outcomes across a variety of other health conditions, including asthma,16 diabetes,17 and HIV infection.18 Several systematic reviews have shown these interventions to be effective in increasing cancer screening, however they are limited to specific populations,19,20 focus only on breast cancer screening,21,22 or report broadly across various disease topics.20,23 This systematic review is a comprehensive assessment of interventions engaging CHWs to increase screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer across settings and populations, whether implemented alone or in a team of public health professionals. Extensive stratified analyses were conducted to identify characteristics of effective interventions engaging CHWs.

METHODS

Guide to Community Preventive Services (“Community Guide”) methods were used.24–26 The search for evidence included 2 steps. First, reviewers identified relevant publications from studies included in previous Community Guide systematic reviews of interventions to increase breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer screening (included studies published 1966 through 2013).27–30 Next, CDC librarians conducted an updated search for papers published between January 1, 2014, and November 5, 2021, evaluating interventions to promote cancer screening. Databases for this review included PubMed, Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane, and CINAHL. The detailed search strategy is available from www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/cancer.

Studies were included if they evaluated interventions engaging CHWs to increase breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer screening; engaged CHWs to implement part or all of the intervention; recruited and trained CHWs who were from or had close knowledge of the targeted community; reported 1 or more outcomes of interest; and were conducted in a World Bank-designated high-income economy31 and published in English. Community Guide methods allow for an array of study designs to assess effectiveness of public health interventions. Studies were excluded if they were single group pre-post studies where the study population was not up to date with screening at baseline, since these studies would only provide favorable results and potentially bias the review finding.

Two review team members independently screened search results and abstracted qualifying studies. Differences were reconciled first by the 2 abstractors, with unresolved differences brought to full review team. Reviewers considered the following when assessing study quality of execution25,26: description of the intervention, population, and sampling frame; assessment of intervention exposure and outcome reliability; description and use of appropriate analytic methods; attrition (i.e., whether more than 20% of study population was lost to follow-up); ability to control for confounding or biasing factors. For RCTs, reviewers also assessed reporting of the randomization process,25,26 accounting for missing outcome data due to loss to follow-up and controlling for cross-contamination bias. Reviewers described studies as having good (0–1 limitation), fair (2–4), or limited (>4) quality of execution. Studies with limited quality of execution were excluded from the analyses.24,25

Primary outcomes of interest were recent2–4 or repeat screenings for breast (mammography), cervical (Pap test), or colorectal (colonoscopy, fecal occult blood testing [FOBT], fecal immunochemical test [FIT], sigmoidoscopy) cancers. Repeat screenings were defined as the completion of 2 or more consecutive, on-time tests.

Changes in recent or repeat screenings compared with no intervention were calculated separately for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening (up to date with any colorectal cancer test, colonoscopy, FOBT or FIT, or sigmoidoscopy based on the recommended frequency). For studies with a comparison group and reporting baseline data, the net differences in pre-to-post-intervention screening use were calculated. If baseline data were unavailable, differences in post-intervention screening use were calculated. For studies without a comparison group, changes in pre-to-post-intervention screening use were calculated. Screening at the longest follow-up was used to determine post-intervention screening use. Participants lost to follow-up were imputed and treated as not up to date with screening whenever possible.

Outcomes were stratified based on whether CHWs delivered all or part of the intervention. “CHW alone” indicates CHWs independently delivered the entire intervention. Some studies with multiple study arms evaluated the effect of adding CHWs on cancer screening, such as comparing CHW-delivered one-on-one education plus small media (videos and printer materials such as letters, brochures, and newsletters) small media alone.32 For these studies, “CHW added” was used to indicate CHWs delivered the intervention as part of a team of public health or healthcare professionals and the effect of adding CHWs can be determined. “CHW in a team” indicates CHWs worked in a team and only overall effectiveness could be determined.

For summary measures, medians and interquartile intervals (IQI) were calculated for outcomes with >4 data points. For study arms where CHWs delivered part of the intervention and when both “CHW added” and “CHW in a team” can be determined, “CHW added” was used in summary measure calculations. For study arms that reported on multiple colorectal cancer screening tests, only 1 test result was used in summary measure calculations and tests were chosen in the following order: up to date with any colorectal cancer test, colonoscopy, FOBT or FIT, or sigmoidoscopy. Additionally, analyses were performed for each cancer type based on whether CHWs delivered all or part of the intervention.

Stratified analyses were performed using all included studies to examine the influence of settings, population characteristics, intervention characteristics, and CHW-specific characteristics on intervention effectiveness.

RESULTS

Search Yield

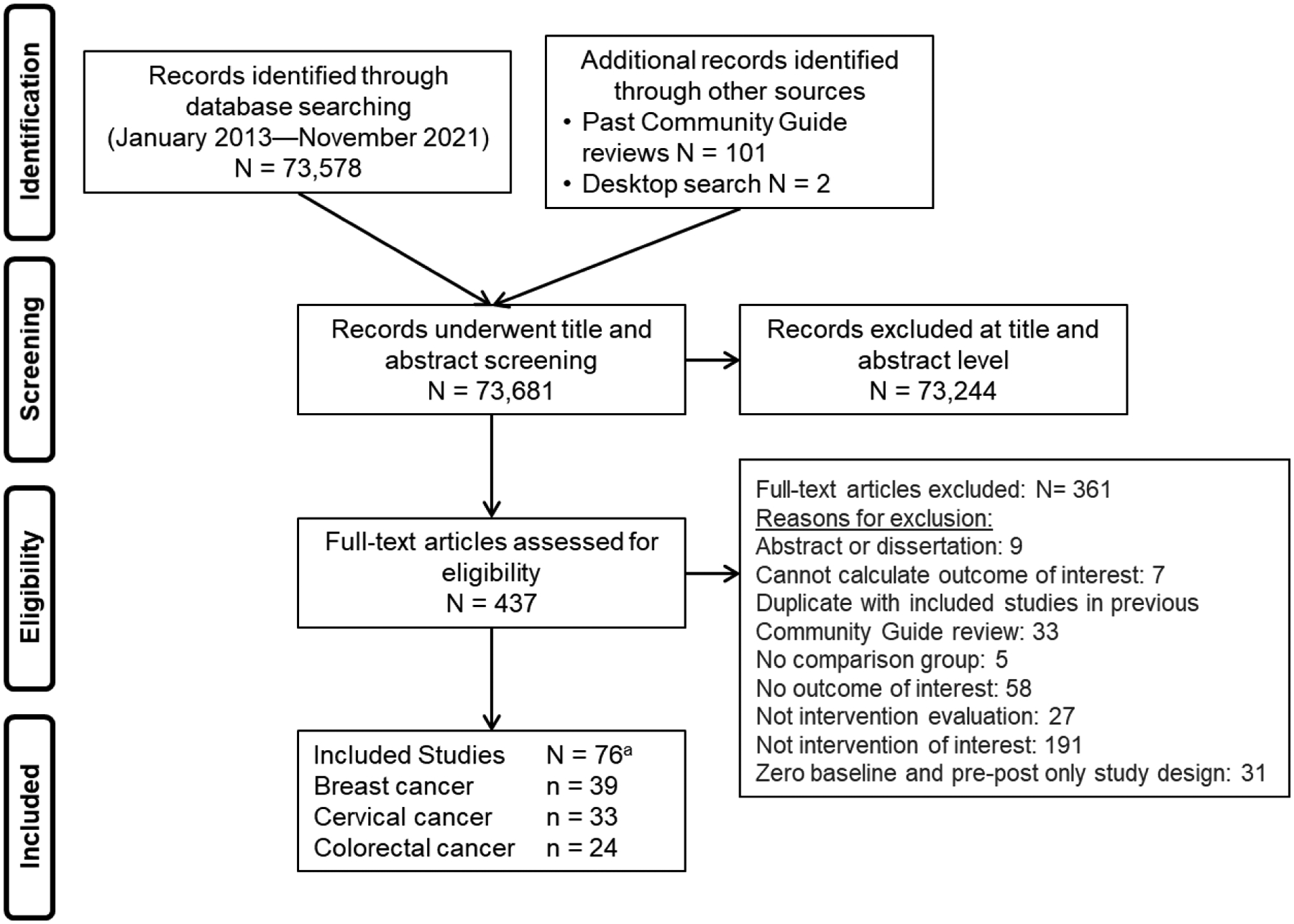

The review team identified 101 potentially relevant publications from previous Community Guide systematic reviews.27–30 The updated search identified 73,578 publications, of which 437 underwent full text screening. Overall, 76 studies32–107 met the inclusion criteria, with 39 studies reporting breast cancer screening,32,34–39,42,43,47–49,52–57,60,62–64,71,75,76,78,80,83,85,87–93,95,104,106 33

studies reporting cervical cancer screening,36,38,39,41,46,47,49,51,52,56,59,68,72,73,77,78,81,83,84,86,87,93–100,103,104,106,107 and 24 studies reporting colorectal cancer screening33,36,39,40,44,45,49,50,53,58,61,62,65–67,69,70,74,79,82,101,102,104,105 (Figure 1). The main reasons for exclusion among the 361 studies excluded during full text screening included reporting on interventions that did not engage CHWs, not reporting recent or repeat cancer screening outcomes, and duplicate studies included in previous Community Guide reviews. Summaries of included studies are available on The Community Guide website.108–110

Figure 1.

Search process and results.

aSome interventions focused on more than 1 cancer type.

Quality of Execution Assessment

Included studies were individual RCTs,33,34,37,39,41,44,46,53,58,60,63–65,68,75,77,80,84–86,90,93–95,97,99,100,102,107 group RCTs,32,45,49,51,52,56,57,66,69,73,74,76,78,79,82,87,91,96,98,101,105 pre-post design with comparison group,38,42,43,47,48,50,55,67,72,81,103 or pre-post only.35,36,40,54,59,61,62,70,71,83,88,89,92,104,106 Ten included studies had good quality of execution;40,43,44,47,55,76,85,90,100,107 the remaining studies had fair quality of execution.32–39,41,42,45,46,48–54,56–75,77–84,86–89,91–99,101–106 The most commonly assigned limitations were convenience sampling,32,35–37,40–42,44–46,49,52,54,56–58,61–66,68,69,71–75,77–82,87–95,98,99,101,102,104–107 use of self-reported data without verification,32,33,36–39,42,45,46,48,49,51,54,56,57,61–63,66–69,71,72,75–83,86,87,91,93,94,96–98,101,102,104,106 and lack of description for CHWs or the study population.32,34,35,38,39,41,42,46,48,50–53,55,57–60,62–65,67,69–71,73,74,81,84,86,87,89,92,97–99,103,105,106

Study and Intervention Characteristics

Detailed description of CHW work and intervention characteristics can be found in Table 1 and Appendix Table 1. Studies were mostly conducted in the U.S.,32–46,48–54,56–58,61–96,98–106 with 1 each in Australia,59 Belgium,55 Canada,47 Hong Kong, China,107 and the United Kingdom.60 One study evaluated an intervention implemented in both the U.S. and Canada.97 Most interventions were offered in urban settings.32,36–38,42,44,47,49,50,53,56,60,65,66,68,70,75–82,84,87–92,95,97–99,101–103,106

Table 1.

CHW Work Characteristics of Included Studies

| Characteristics | Number of studies reporting | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Level of involvement in intervention delivery | ||

| Implemented everything | 39 | 33, 35, 39, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 50, 52, 54, 57, 61, 62, 66, 70–73, 75, 76, 78, 79, 82–86, 88, 89, 91, 95, 96, 99–101, 103, 104, 107 |

| Implemented majority of components | 27 | 32, 34, 36–38, 40, 46, 48, 53, 55, 56, 60, 63, 65, 67–69, 74, 77, 80, 90, 92–94, 97, 98, 102 |

| Implemented minority of components | 10 | 42, 44, 51, 58, 59, 64, 81, 87, 105, 106 |

| Received formal training | ||

| Yes | 65 | 32–36, 38, 39, 41, 43–50, 52–58, 60–73, 75–80, 82, 83, 85, 86, 88–96, 98–105, 107 |

| Not reported | 11 | 37, 40, 42, 51, 59, 74, 81, 84, 87, 97, 106 |

| Supervision of CHW performance | ||

| Yes | 31 | 33, 35, 36, 38, 39, 46, 47, 52, 53, 55, 63, 65, 67, 69, 71, 75, 76, 78, 82–91, 94, 95, 102 |

| Not reported | 45 | 32, 34, 37, 40–45, 48–51, 54, 56–62, 64, 66, 68, 70, 72–74, 77, 79–81, 92, 93, 96–101, 103–107 |

| CHWs matched to the community | ||

| Yes | 72 | 33–58, 60–69, 71–86, 88–107 |

| Not reported | 4 | 32, 59, 70, 87 |

| Reimbursement | ||

| Yes | 19 | 35, 36, 38, 45, 49, 54, 62, 64, 66, 68, 77, 79, 80, 82, 85, 90, 91, 101, 105 |

| Not reported | 57 | 32–34, 37, 39–44, 46–48, 50–53, 55–61, 63, 65, 67, 69–76, 78, 81, 83, 84, 86–89, 92–100, 102–104, 106, 107 |

| Core roles111 | ||

| Cultural mediation among individuals, communities, and health and social service systems | 61 | 32–41, 43–49, 52, 56, 58, 59, 61–64, 66–69, 71–80, 82, 83, 85–91, 93–104, 107 |

| Providing culturally appropriate education and information | 70 | 32–52, 55, 56, 58–66, 68, 69, 71–105, 107 |

| Care coordination, case management, and system navigation | 38 | 34–37, 39, 47, 49–54, 58, 65, 66, 68, 70, 71, 73–77, 80, 85, 88–90, 93, 95, 97–100, 103, 104, 106, 107 |

| Providing coaching and social support | 59 | 32–41, 43, 44, 47–50, 52, 54, 56, 57, 61–72, 75–80, 82, 83, 85–95, 97, 98, 100, 102–105, 107 |

| Advocating for individuals and communities | 1 | 80 |

| Building individual and community capacity | 70 | 32–45, 47–52, 54–59, 61–80, 82–92, 94–103, 105–107 |

| Providing direct services | 0 | |

| Implementing individual and community assessments | 1 | 104 |

| Conducting outreach | 41 | 32–35, 39, 41–49, 52, 54, 56, 57, 60, 66, 71, 72, 77–82, 85, 86, 89, 91, 93–95, 97, 98, 100, 101, 104, 106 |

| Participating in evaluation and research | 1 | 104 |

CHW, community health worker.

Interventions engaged CHWs to increase screening for breast,32,34,35,37,42,43,48,54,55,57,60,63,64,71,75,76,80,85,88–92 cervical,41,46,51,59,68,72,73,77,81,84,86,94,96–100,103,107 colorectal,33,40,44,45,50,58,61,65–67,69,70,74,79,82,101,102,105 or multiple cancer types.36,38,39,47,49,52,53,56,62,78,83,87,93,95,104,106 Most interventions engaged CHWs to deliver all33,35,39,41,43,45,47,49,50,52,54,57,61,62,66,70–73,75,76,78,79,82–86,88,89,91,95,96,99–101,103,104,107 or a major part32,34,36–38,40,46,48,53,55,56,60,63,65,67–69,74,77,80,90,92–94,97,98,102 of the intervention. CHWs increased demand for screening services through one-on-one32–37,39,41,43,44,46,48–50,52,54–58,60,63–65,69,75,82,85–91,93–95,97–102,104 and group35,36,38,40,42,45,47–49,51,56,59,61,62,66–69,71–74,76–84,87,89,92,96,98,101,103,105,107 education, client reminders,39,44,47,53,66,70,88,89,100 and small media distribution.67,73,86,88,90,103 CHWs increased clients’ access to services by assisting with appointment scheduling,35,37,39,47,49,50,68,70,71,73,75,77,79,80,85,88–90,97,98,100,103,104,106,107 providing translation,47,73,97,103 arranging transportation35,47,73,88–90,97,98,103 or childcare,39 and reducing administrative barriers by completing paperwork and accompanying participants to appointments when needed.39,40,47,49,50,53,75,79,88,89,98,104,107

CHW Work Characteristics

The Community Health Worker Core Consensus Project recommends 10 core roles frequently performed by CHWs that can improve community health.111 CHWs often performed several of these core roles in combination, such as providing cultural mediation among individuals, communities, and health and social service systems;32–41,43–49,52,56,58,59,61–64,66–69,71–80,82,83,85–91,93–104,107 providing culturally appropriate education and information;32–52,55,56,58–66,68,69,71–105,107 providing coaching and social support;32–41,43,44,47–50,52,54,56,57,61–72,75–80,82,83,85–95,97,98,100,102–105,107 and building individual and community capacity32–45,47–52,54–59,61–80,82–92,94–103,105–107 (Table 1). In roughly half of the interventions, CHWs conducted outreach32–35,39,41–49,52,54,56,57,60,66,71,72,77–82,85,86,89,91,93–95,97,98,100,101,104,106 and provided care coordination, case management, and system navigation services.34–37,39,47,49–54,58,65,66,68,70,71,73–77,80,85,88–90,93,95,97–100,103,104,106,107 In very few studies, CHWs advocated for individuals and communities80 or implemented individual and community assessment and participated in evaluation and research.104 No CHWs provided direct services since all cancer screenings need to be delivered in healthcare settings. In most interventions, CHWs performed 4 or more core roles.32–41,43–45,47–50,52,54,56,58,61–66,68,69,71–80,82,83,85–91,93–95,97–104,107

Nearly all included studies reported that CHWs were matched to the community in which they served.33–58,60–69,71–86,88–107 Many studies did not report on the educational background of CHWs, however most studies reported that CHWs received formal training,32–36,38,39,41,43–50,52–58,60–73,75–80,82,83,85,86,88–96,98–105,107 approximately half reported that CHWs received supervision of their performance, and several reported that CHWs received some form of reimbursement for their services.35,36,38,49,54,64,66,68,77,79,80,82,85,90,91,101,105

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in Included Studies

Detailed information on demographic characteristics of study participants can be found in Table 2. Study participants had a median age of 54 years.32–34,36,37,39,42,46,47,51,56–58,60,61,63–66,68–72,74,76–78,80–86,88–91,93,100–103,105,107 Across studies evaluating interventions to increase colorectal cancer screening, a median of 68% of participants were female.33,39,40,44,45,50,53,58,61,65,66,69,70,74,79,82,101,102,104,105 Thirty36–38,42,43,46,48,49,52,53,57,61,72,74–76,78,79,82,83,90,92–95,101,102,104,105,107 of the included studies reported a majority of participants with annual household incomes less than $40,000 and 5 studies33,47,65,87,106 focused on low-income communities. Three-quarters of participants had a high school education or less.36–39,42,43,46,48,51,56,57,61,63,66,67,69,73,75,76,83–87,91,94,95,100,102,103,105

Table 2.

Population Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristics | Number of Studies Reporting | Citation | Distribution Median (IQI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Reported in years | 46 | 32–34, 36, 37, 39, 42, 46, 47, 51, 50–58, 60, 61, 63–66, 68–72, 74, 76–78, 80–86, 88–91, 93,100–103,105,107 | 54 years (46 to 60) |

| Reported in ranges | 25 | 35, 38, 43–45, 48–50, 52, 53, 59, 67, 73, 75, 79, 87, 92, 94–99, 104, 106 | Not applicable |

| Not reported | 5 | 40, 41, 54, 55, 62 | Not applicable |

| Sexa | |||

| Female | 20 | 33, 39, 40, 44, 45, 50, 53, 58, 61, 65, 66, 69, 70, 74, 79, 82, 101, 102, 104, 105 | 68% (57% to 76%) |

| Male | 20 | 33, 39, 40, 44, 45, 50, 53, 58, 61, 65, 66, 69, 70, 74, 79, 82, 101, 102, 104, 105 | 32% (24% to 43%) |

| 100% Female | 2 | 36, 67 | Not applicable |

| Not reported | 1 | 62 | Not applicable |

| Race and ethnicity, U.S. only (71 studies) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | 85 | 42% |

| Asian-American | 4 | 39, 50, 65, 102 | 29% (9% to 46%) |

| Black or African American | 10 | 34, 37, 50, 53, 65, 67, 85, 87, 94, 105 | 33% (27% to 50%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 | 34, 37, 40, 42, 50, 65, 102 | 45% (12% to 58%) |

| White | 12 | 33, 34, 40, 50, 53, 64, 65, 67, 85, 86, 94, 105 | 50% (22% to 85%) |

| Recruited specific populations | |||

| 100% American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 | 46, 58 | Not applicable |

| 100% Asian American | 18 | 38, 45, 51, 56, 66, 68, 73, 74, 77, 79–82, 97–99, 101, 103 | Not applicable |

| 100% Black or African American | 12 | 32, 42, 48, 54, 57, 61, 62, 69, 75, 90, 91, 95 | Not applicable |

| 100% Hawaiian and Pacific Islander | 3 | 35, 76, 96 | Not applicable |

| 100% Hispanic/Latino | 15 | 36, 41, 43, 44, 49, 52, 72, 78, 83, 84, 92, 93, 100, 104, 106 | Not applicable |

| 100% Serbo-Croatian | 2 | 88, 89 | Not applicable |

| Not reported | 3 | 63, 70, 71 | Not applicable |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 36 | 36, 38, 42, 43, 45, 49, 51, 54, 56, 61, 63, 66–68, 72–74, 76–84, 86, 87, 90, 94–96, 101, 102, 104, 107 | 48% (27% to 58%) |

| Not reported | 40 | 32–35, 37, 39–41, 44, 46–48, 50, 52, 53, 55, 57–60, 62, 64, 65, 69–71, 75, 85, 88, 89, 91–93, 97–100, 103, 105, 106 | Not applicable |

| Incomeb | |||

| ≥50% with annual household income less than $40,000 | 30 | 36–38, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49, 52, 53, 57, 61, 72, 74–76, 78, 79, 82, 83, 90, 92–95, 101, 102, 104, 105, 107 | Not applicable |

| Focused on low-income communitiesc | 5 | 33, 47, 65, 87, 106 | Not applicable |

| Not reported | 34 | 34, 35, 39–41, 44, 50, 51, 54–56, 58–60, 62, 64, 67, 68, 70, 71, 73, 77, 80, 84, 85, 88, 89, 91, 96–100, 103 | Not applicable |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school education | 37 | 33, 36, 39, 40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 61, 66–69, 73–75, 77–82, 85–87, 89, 94, 95, 99, 100, 103, 104, 106 | 41% (28% to 64%) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 25 | 33, 36, 39, 42, 43, 45, 46, 51, 54, 61, 66, 67, 69, 73–75, 79, 85–87, 94, 95, 97, 100, 103 | 31% (25% to 36%) |

| More than high school education | 33 | 33, 36, 37, 39, 42, 43, 45, 46, 51, 56, 57, 61, 63, 66, 67, 69, 73–76, 79, 83–86, 91, 94, 95, 100, 102, 103, 105, 107 | 32% (16% to 55%) |

| Not reported | 18 | 34, 35, 41, 44, 47, 50, 53, 55, 58–60, 62, 64, 65, 70, 88, 92, 96 | Not applicable |

| Insurance status | |||

| Insured | 46 | 32, 33, 36–38, 40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48–54, 56, 57, 65–67, 70–72, 74, 76, 78–86, 90, 93, 94, 96, 100, 101, 103, 104, 106, 107 | 67% (46% to 81%) |

| 100% insured | 8 | 34, 39, 47, 55, 59, 60, 88, 92 | Not applicable |

| Not reported | 20 | 35, 41, 44, 58, 61–64, 68, 69, 73, 77, 87, 91, 95, 97–99, 102, 105 | Not applicable |

Only studies examining intervention impact on colorectal cancer screening.

Seven studies provided income data measured in various ways and could not be summarized.

Study authors stated interventions were implemented in communities with low income, but no specific numbers provided.

Fifty-two32,35,36,38,41–46,48,49,51,52,54,56–58,61,62,66,68,69,72–84,88–93,95–101,103,104,106 of the 71 U.S. studies implemented interventions among racial and ethnic minority populations. Among the other U.S. studies, a median 50% of participants self-identified as White,33,34,40,50,53,64,65,67,85,86,94,105 33% as Black or African American,34,37,50,53,65,67,85,87,94,105 29% as Asian-American,39,50,65,102 45% as Hispanic or Latino,34,37,40,42,50,65,102 and 1 study reported 42% of participants were American Indian/Alaska Native.85

Changes in Breast Cancer Screening

Interventions engaging CHWs increased recent breast cancer screening by a median of 11.5 pct pts (IQI: 5.5 to 23.5; 16 study arms had 0% baseline)32,34–39,42,43,47–49,52–56,60,62–64,71,75,76,78,80,83,85,87–93,95,104,106 (Table 3). Interventions increased screening when stratified by “CHW alone,” “CHW added,” and “CHW in a team,” with “CHW in a team” demonstrating the greatest increase (Table 3). One study57 provided narrative results and reported no change in mammography screening rates. Two studies38,62 provided results on repeated screening and reported a 1.2 pct pts decrease in mammography maintenance among intervention participants (range: −7.6 to 22.0).

Table 3.

Impact of Interventions Engaging CHWs on Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Screening

| Cancer type/ Screening test/ Effect of CHW | Citations | Median (IQI) |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | ||

| Mammography | ||

| Overall (42 study arms) | 32, 34–39, 42, 43, 47–49, 52–56, 60, 62–64, 71, 75, 76, 78, 80, 83, 85, 87–93, 95, 104, 106 | Median increase of 11.5 percentage points (IQI: 5.5 to 23.5) |

| CHW alone (21 study arms) | 35, 39, 43, 47, 49, 52, 54, 55, 62, 71, 75, 76, 78, 83, 85, 88, 89, 91, 95, 104 | Median increase of 9.2 percentage points (IQI: 4.7 to 22.8) |

| CHW added (6 study arms) | 32, 34, 43, 48, 60, 80 | Median increase of 11.0 percentage points (IQI: 2.3 to 13.5) |

| CHW in a team (17 study arms) | 34, 36–38, 42, 43, 48, 53, 55, 56, 63, 64, 87, 92, 93, 106 | Median increase of 13.7 percentage points (IQI: 9.1 to 29.7) |

| Cervical cancer | ||

| Pap test | ||

| Overall (31 study arms) | 36, 38, 39, 41, 47, 49, 51, 52, 56, 68, 72, 73, 77, 78, 81, 83, 84, 86, 87, 93–100, 103, 104, 106, 107 | Median increase of 12.8 percentage points (IQI: 6.4 to 21.0) |

| CHW alone (18 study arms) | 39, 41, 47, 49, 52, 72, 73, 78, 83, 84, 86, 95, 96, 99, 100, 103, 104, 107 | Median increase of 13.7 percentage points (IQI: 7.6 to 20.2) |

| CHW added (3 study arms) | 68, 77, 94 | Median increase of 11.0 percentage points (Range: 6.4 to 16.8) |

| CHW in a team (10 study arms) | 36, 38, 51, 56, 81, 87, 93, 97, 98, 106 | Median increase of 15.4 percentage points (IQI: 3.0 to 34.0) |

| Colorectal cancer | ||

| Colonoscopy, FOBT/FIT, or sigmoidoscopy | ||

| Overall (25 study arms) | 33, 36, 39, 40, 44, 45, 49, 53, 58, 61, 62, 65, 66, 69, 70, 74, 79, 82, 101, 102, 104, 105 | Median increase of 10.5 percentage points (IQI: 4.5 to 17.5) |

| CHW alone (15 study arms) | 33, 39, 40, 45, 49, 61, 62, 66, 70, 79, 82, 101, 104 | Median increase of 10.5 percentage points (IQI: 4.0 to 13.0) |

| CHW added (4 study arms) | 44, 102, 105 | Median increase of 6.5 percentage points (IQI: 5.1 to 29.7) |

| CHW in a team (8 study arms) | 33, 40, 45, 58, 62, 74, 93, 96, 104, 107 | Median increase of 16.1 percentage points (IQI: 4.4 to 27.3) |

| Colonoscopy | ||

| CHW alone (7 study arms) | 39, 61, 62, 70, 104 | Median increase of 10.5 percentage points (IQI: 7.1 to 13.0) |

| FOBT/FIT | ||

| Overall (17 study arms) | 39, 40, 44, 45, 49, 58, 61, 62, 66, 70, 101, 102, 104, 105 | Median increase of 7.8 percentage points (IQI: 5.2 to 16.5) |

| CHW alone (12 study arms) | 39, 40, 45, 49, 61, 62, 66, 70, 101, 104 | Median increase of 7.7 percentage points (IQI: 3.7 to 17.9) |

| CHW added (4 study arms) | 44, 102, 105 | Median increase of 6.8 percentage points (IQI: 5.1 to 29.8) |

| CHW in a team (3 study arms) | 44, 58, 102 | Median increase of 13.5 percentage points (Range: 12.5 to 28.6) |

| Sigmoidoscopy | ||

| CHW alone (5 study arms) | 61, 62, 104 | Median increase of 3.5 percentage points (IQI: −2.3, 58.5) |

| Colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy | ||

| CHW alone (4 study arms) | 45, 49, 66, 101 | Median increase of 6.6 percentage points (IQI: 4.3, 8.2) |

CHW, community health worker; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; IQI, interquartile interval; pct pts, percentage points.

Changes in Cervical Cancer Screening

Interventions increased recent cervical cancer screening by a median of 12.8 pct pts (IQI: 6.4 to 21.0; 14 study arms had 0% baseline).36,38,39,41,47,49,51,52,56,68,72,73,77,78,81,83,84,86,87,93–100,103,104,106,107 Interventions increased screening when stratified by “CHW alone,” “CHW added,” and “CHW in a team,” with “CHW in a team” demonstrating the greatest increase (Table 3). Two studies provided narrative results and reported increased Pap test use.46,59 One study38 provided results on repeated screening and reported 22.0 pct pts increase in Pap test maintenance among intervention participants.

Changes in Colorectal Cancer Screening

Interventions engaging CHWs increased colorectal cancer screening overall using colonoscopy, FOBT, FIT, or sigmoidoscopy by a median of 10.5 pct pts (IQI: 4.5 to 17.5; 7 study arms had 0% baseline).33,36,39,40,44,45,49,53,58,61,62,65,66,69,70,74,79,82,101,102,104,105 Interventions increased screening when stratified by “CHW alone,” “CHW added,” and “CHW in a team,” with “CHW in a team” demonstrating the greatest increase (Table 3). Colorectal cancer screening increased whether using colonoscopy (median increase of 10.5 pct pts; IQI: 7.1 to 13.0; 0 study arms had 0% baseline),39,61,62,70,104 or FOBT or FIT (median increase of 7.8 pct pts; IQI: 5.2 to 16.5; 2 study arms had 0% baseline).39,40,44,45,49,58,61,62,66,70,101,102,104,105 A small increase in screening was observed when sigmoidoscopy was used alone (median increase of 3.5 pct pts; IQI: −2.3 to 58.5; 0 study arms had 0% baseline).61,62,104 Four studies reported an increase in screening using either colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy (range: 3.7 to 8.6 pct pts; 0 study arms had 0% baseline).45,49,66,101 Two studies provided narrative results and reported increases in colorectal cancer screening using any test.50,67 No studies provided results on repeated screening.

Stratified Analysis Based on Intervention Characteristics

Single factor stratified analyses were performed across all 76 included studies. Detailed results can be found in Appendix Table 2. Interventions engaging CHWs produced similar increases in cancer screening whether inside32–45,48,49,51–54,56,58,61–66,68–89,91–96,98–106 or outside47,55,60,107 the U.S. Interventions that were designed to increase demand for and access to cancer screening services35,37,39,40,47,49,53,68,70,71,73,75,77,79,80,85,88–90,97,98,100,103,104,107 resulted in larger increases in screening than interventions increasing demand alone.32–34,36,38,41–45,48,51,52,54–56,58,60–66,69,72,74,76,78,81–84,86,87,91–96,99,101,102,105 Only 1 study106 was designed to improve access to services alone.

Screening increased regardless of the number of intervention components, but larger increases were observed when CHWs implemented 4 or more components.35,39,47,49,73,88–90,97,98,103 Greater increases in screening were reported for interventions that provided group education35,36,38,40,42,45,47–49,51,56,61,62,66,68,69,71–74,76–84,87,89,96,98,101,103,105,107 than those that provided one-on-one education.32–34,36,37,39,41,43,44,48,49,52,54–56,58,60,64,65,69,75,82,85–91,93–95,97–102,104 Among interventions that increased access to services, largest increases were observed when CHWs assisted with translation47,73,97,103 or addressed transportation barriers.35,47,73,88–90,97,98,103

Interventions were effective whether CHWs delivered services face-to-face,34,35,38,40–42,45,48,51,60–63,68,71,72,76,78,81,83,84,87,91,92,94–96,98,103,105,106 remotely,37,53,55,64,65,70,102 or a combination of the two,33,36,39,43,44,47,49,52,54,56,58,66,69,73–75,77,79,80,82,85,86,88–90,93,97,99–101,104,107 with slightly larger increases in screening reported when both methods were used. Interventions were effective across different levels of intensity as similar increases were reported when CHWs met with study participants one34,35,41,47,60,63,71,72,88,97,99,105,106 or more times.32,33,36,40,42,43,45,49,51–56,61,62,64–66,68–70,75–80,82–86,89–91,93–96,98,100,101,103,104,107 The duration of interventions with multiple sessions ranged from half a month to 60 months (median: 4 months). While interventions were effective across durations, slightly larger effects were reported by studies with longer intervention durations.34,36–38,49,51,54,56,58,81,83,85–89

Stratified Analysis Based on CHW Work Characteristics

Detailed results can be found in Appendix Table 3. Interventions were effective across the 9 types of core roles CHWs performed in the included studies, though interventions where CHWs provided care coordination, case management, and system navigation34–37,39,47,49,51–54,58,65,66,68,70,71,73–77,80,85,88–90,93,95,97–100,103,104,106,107 or focused on building individual and community capacity32–45,47–49,51,52,54–56,58,61–66,68–80,82–92,94–103,105–107 reported the largest increases. No clear pattern was observed across the number of core roles CHWs performed.

Stratified Analysis Based on Demographic Characteristics

Detailed results can be found in Appendix Table 4. Interventions were effective for age-appropriate populations with different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Interventions engaging CHWs were effective across racial and ethnic groups examined; however a larger increase was observed among Asian-American populations (median increase of 12.1 pct pts; IQI: 6.1 to 45.3)38,45,51,56,66,68,73,74,77,79–82,97–99,103 than Black or African-American (median increase of 7.8 pct pts; IQI: 2.2 to 14.0)32,42,48,54,61,62,69,75,91,95 or Hispanic or Latino populations (median increase of 8.6 pct pts; IQI: 1.4 to 14.0).36,41,43,44,49,52,72,78,83,84,92,93,100,101,104,106 Even though only a few studies recruited exclusively from American Indian Alaskan Native58 or Pacific Islanders,35,76,96 large increases in screening use were observed. Screening use increased for populations with different educational, employment, insurance, and income levels, with the largest increase observed among low-income communities.47,65,87,106 Interventions were effective regardless of whether participants had a regular source of health care.

Interventions implemented among populations with baseline screening rates of 0%33,34,37,41,43,44,47,51–53,55,56,58,60,64,65,72–74,76,79,85,86,90,93,94,96,100,103,107 or below 50%35,38,39,45,48,49,61,62,66,70,77,78,83,87,89,91,95,97–99,101,102,104,106 reported greater increases than those implemented among populations with higher baseline screening rates, although screening use increased across baseline levels.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review found that interventions engaging CHWs increased breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening use. Findings from this review served as the basis for Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) recommendations to use these interventions to increase screening for breast cancer by mammography,108 cervical cancer by Pap test,109 and colorectal cancer by colonoscopy or FOBT.110 Currently, there are approximately 67,000 CHWs employed in the U.S. and this number is expected to grow by 16% from 2021 to 2031.112

Downstream health benefits from increases in breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening could include earlier diagnosis and treatment and reduced cancer-related morbidity.2–4,113 Interventions produced similar results whether inside or outside the U.S. They were effective across different settings with different population and intervention characteristics, suggesting intervention composition can be flexible. CHWs worked alone or as part of a team and implemented interventions with a heterogeneous mix of components, duration, and intensity. This suggests that decision makers have flexibility in considering the local population, needs, and context when designing interventions and determining the optimal extent of CHW involvement.

Interventions where CHWs delivered the intervention with other team members (“CHW in a team”) were more effective at increasing screening than those where CHWs independently delivered the entire intervention (“CHW alone”). One possible explanation is that interventions engaging CHWs as part of a team tend to deliver more intervention components (median of 4 components) when compared with interventions CHWs deliver services alone (median of 1 component). Both the current review and the previous Community Guide reviews on multicomponent interventions27–29 found that cancer screening increased with the number of intervention components.

Interventions engaging CHWs were more effective when designed to increase both demand for and access to cancer screening services, as found in previous Community Guide reviews.27–29 Nearly all studies included in this review provided either group or one-on-one education. Interventions where CHWs provided group education reported larger increases in cancer screening than those with one-on-one education. Similar findings were reported by Seven et al., who compared the effects of group versus individually delivered education on breast cancer screening.114 These findings may suggest that social norms and modeling play an important role in motivating participants to obtain screening, as seeing others like themselves overcome similar barriers to receive cancer screening could influence participants’ decision to receive screening.115 Studies have shown that group education resulted in similar cancer screening rates,116,117 knowledge,116 or satisfaction with care118 when compared with individual education while costing less.117

For interventions offering multiple sessions, those spanning 6 months or longer were more effective than those with shorter durations. This might suggest that extending the overall duration of interventions might lead to a greater increase in cancer screening. Programs may choose to retain CHWs once trained and continue offering services on a recurring basis.

Several core roles were either not reported or not performed by CHWs included in this review. These roles include advocating for individuals and communities, implementing individual and community assessment, providing direct services, and participating in evaluation and research. Interventions engaging CHWs already apply many elements of community-based participatory research to assess community needs. Involving CHWs in needs assessment could ensure a community’s needs are understood and addressed. CHWs can also provide valuable input from intervention conceptualization through evaluation.

Most studies did not report on CHW reimbursement and the review team cannot determine whether CHWs received payments for their services, and no conclusions could be made on whether providing reimbursement could improve intervention effectiveness. Policies regarding payment from insurance payers vary by state, with only 7 authorizing Medicaid or other insurer reimbursement for CHW services.119 In other countries, community health workers such as social prescribing link workers120 in the United Kingdom and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers in Australia121 are paid positions.

Several interventions reported additional benefits of engaging CHWs in the delivery of services. CHWs reported satisfaction with their work55,105 and that the experience had a positive impact on their personal development.47 CHWs in one study expressed an interest to continue their work.66 Participants expressed gratitude to CHWs35 and some reported wishing to participate as CHWs in the future.68 One study reported an increase in check-up appointments in the intervention city, possibly indicating the intervention increased general healthcare usage in addition to increasing screening.38

Interventions were effective when implemented among uninsured and low-income populations and when focusing on specific racial and ethnic groups. This is particularly important because in 2018, people without health insurance or with incomes below 139% of the federal poverty level had lower cancer screening use than their counterparts.5 Asian American persons, American Indian persons, and Alaska Native persons also had lower cervical and colorectal cancer screening rates than other racial and ethnic groups. Foreign-born persons are less likely to be screened for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers than those born in the U.S.122 Interventions where CHWs provided language translation services47,73,97,103 reported large increases in screening, suggesting language is an important barrier faced by non-English speaking populations. CHWs often closely identify with the populations they serve and can be especially effective at addressing the existing disparities and improving health equity.

Advances in technology have led to a rapidly changing healthcare industry and provide opportunities for CHWs to utilize different intervention delivery methods. Video conferencing technologies allow for face-to-face communication via a remote connection, potentially expanding the reach of one-on-one or group education, especially for those in rural areas or with transportation barriers. As medical facilities continue to integrate telemedicine and adopt new technologies, there may be increased opportunities for streamlining appointment scheduling, allowing CHWs to better serve their clients.

Additional research and evaluation are needed to fill remaining gaps in the evidence base. The impact of interventions engaging CHWs on repeat screening could not be determined, and few studies included American Indian/Alaska Native populations. Also, more evidence is needed to determine if intervention effectiveness is influenced by the supervision, training, or compensation of CHWs, or by involving CHWs in research and evaluations.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. Over half of the included studies provided limited description of interventions or populations and many relied on convenience sampling. Some studies relied on self-reported screening results without verification. However, while self-reported breast, cervical, and colorectal screening outcomes are often overestimated, these measures are still considered reasonably valid.123–126 Lastly, publication bias cannot be ruled out, and it is possible that studies with null results are missing from the dataset.

CONCLUSIONS

The CPSTF also recommends interventions engaging CHWs to increase breast,108 cervical,109 and colorectal cancer screening,110 improve cardiovascular disease management,127 diabetes prevention,128 and diabetes management.129 The findings that provided the basis for those recommendations, combined with findings from the current review, suggest that interventions engaging CHWs are effective in preventing and managing multiple chronic conditions. A systematic review of the economic evidence found that interventions engaging CHWs to increase cervical and colorectal cancer screening use are cost-effective, and interventions to increase colonoscopy use are associated with net healthcare cost savings.130 As of June 2016, 6 states had enacted laws to authorize a certification process for CHWs, 5 of which authorized the creation of a standardized curricula based on core competencies.111 Additionally, 7 states authorized Medicaid or other insurer reimbursement for services performed by CHWs.119 Standardizing the role of CHWs and providing certification opportunities could ensure CHW proficiency and increase their credibility. Allowing for reimbursement could also encourage more people to become CHWs, reduce attrition, and enable more decision makers to fund interventions that engage CHWs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Onnalee A. Gomez and Yolanda Strayhorn (formerly or currently with the Library Science Branch, Division of Public Health Information Dissemination, CDC, respectively), for conducting the searches. Krista Hopkins Cole, from Cherokee Nation Assurance, Arlington, VA, provided input into the development of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The work of Devon L. Okasako-Schmucker, Jamaicia Cobb and Ka Zang Xiong was supported with funds from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE).

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Shawna L. Mercer was affiliated with the Community Guide Office at the time this review was conducted and is currently affiliated with the Office of the Director, Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Names and affiliations of Community Preventive Services Task Force members can be found at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/task-force/community-preventive-services-task-force-members.

- Devon L. Okasako-Schmucker: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Validation; Roles/Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

- Yinan Peng: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Supervision; Validation; Roles/Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

- Jamaicia Cobb: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Validation; Writing – review & editing

- Leigh Ramsey Buchanan: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Validation; Roles/Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

- Ka Zang Xiong: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Validation; Roles/Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

- Shawna L. Mercer: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Susan A. Sabatino: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Stephanie Melillo: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Patrick L. Remington: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Shiriki K. Kumanyika: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Beth Glenn: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Erica S. Breslau: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Cam Escoffery: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Maria E. Fernandez: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Gloria D. Coronado: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Karen Glanz: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Patricia Dolan. Mullen: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Sally W. Vernon: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing

- Community Preventive Services Task Force: Conceptualization; Validation; Writing – review & editing

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2021 submission data (1999–2019): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute, released in June 2022 www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 2.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: screening. Bethesda (MD): January 2016a. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-screening. Accessed October 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical cancer: screening. Bethesda (MD): August 2018. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed October 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal cancer: screening. Bethesda (MD): May 2021. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening. Accessed October 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, White MC, et al. Cancer screening test receipt - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(2):29–35. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7002a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healthy People 2030. Cancer objectives. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 7.White A, Thompson TD, White MC, et al. Cancer screening test use-United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:201–206. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, et al. Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):541–553. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong MD, Ettner SL, Boscardin WJ, Shapiro MF. The contribution of cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis and survival to racial differences in years of life expectancy. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):475–481. 10.1007/s11606-009-0912-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bureau of Labor Statistics USDoL. Occupational outlook handbook, health educators and community health workers. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/community-and-social-service/health-educators.htm. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 11.Lehmann U, Sanders D. Community health workers: what do we know about them? The state of evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Public Health Association. APHA Governing Council Resolution 2001–15. Recognition and support for community health workers’ contributions to meeting our nation’s health care needs. 2001. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/15/13/24/recognition-and-support-community-health-workers-contrib-to-meeting-our-nations-health-care-needs. Accessed October 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kash BA, May ML, Tai-Seale M. Community health worker training and certification programs in the United States: findings from a national survey. Health Policy. 2007;80(1):32–42. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherrington A, Ayala GX, Elder JP, Arredondo EM, Fouad M, Scarinci I. Recognizing the diverse roles of community health workers in the elimination of health disparities: from paid staff to volunteers. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(2):189–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacob V, Chattopadhyay SK, Hopkins DP, et al. Economics of community health workers for chronic disease: findings from Community Guide systematic reviews. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(3):e95–e106. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger JW, Takaro TK, Song L, Weaver M. The Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project: a randomized, controlled trial of a community health worker intervention to decrease exposure to indoor asthma triggers. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(4):652–659. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):544–556. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenya S, Jones J, Arheart K, et al. Using community health workers to improve clinical outcomes among people living with HIV: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2927–2934. 10.1007/s10461-013-0440-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roland KB, Milliken EL, Rohan EA, et al. Use of community health workers and patient navigators to improve cancer outcomes among patients served by Federally Qualified Health Centers: a systematic literature review. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):61–76. 10.1089/heq.2017.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhagen I, Steunenberg B, de Wit NJ, Ros WJG. Community health worker interventions to improve access to health care services for older adults from ethnic minorities: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):497. 10.1186/s12913-014-0497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadler BM, Judge CM, Prout M, Allen JD, Geller AC. Improving breast cancer control via the use of community health workers in South Africa: a critical review. J Oncol. 2011;2011:150423. 10.1155/2011/150423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells KJ, Luque JS, Miladinovic B, et al. Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1580–1598. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):39. 10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briss P, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to Community Preventive Services-methods. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(15):35–43. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(Suppl 1):44–74. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guide to the Community Preventive Services. Methods Manual for Community Guide Systematic Reviews. 2021. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/methods-manual. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 27.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cancer screening: Multicomponent Interventions - Breast Cancer. 2016. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cancer-screening-multicomponent-interventions-breast-cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 28.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cancer screening: Multicomponent Interventions - Cervical Cancer. 2016. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cancer-screening-multicomponent-interventions-cervical-cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cancer screening: Multicomponent Interventions - Colorectal Cancer. 2016. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cancer-screening-multicomponent-interventions-colorectal-cancer. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 30.Sabatino SA, Lawrence B, Elder R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to increase screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers: nine updated systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):97–118. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519#High_income. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 32.Husaini BA, Emerson JS, Hull PC, Sherkat DE, Levine RS, Cain VA. Rural-urban differences in breast cancer screening among African American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4):1–10. 10.1353/hpu.2005.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adegboyega A, Aleshire M, Wiggins AT, Palmer K, Hatcher J. A motivational interviewing intervention to promote CRC screening: a pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45(1):E229–E237. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed NU, Haber G, Semenya KA, Hargreaves MK. Randomized controlled trial of mammography intervention in insured very low-income women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(7):1790–1798. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aitaoto N, Braun KL, Estrella J, Epeluk A, Tsark J. Design and results of a culturally tailored cancer outreach project by and for Micronesian women. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E82. 10.5888/pcd9.100262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen JD, Pérez JE, Tom L, Leyva B, Diaz D, Torres MI. A pilot test of a church-based intervention to promote multiple cancer-screening behaviors among Latinas. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(1):136–143. 10.1007/s13187-013-0560-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen B Jr, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Evaluating a tailored intervention to increase screening mammography in an urban area. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(10):1350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bird JA, McPhee SJ, Ha N-T, Le B, Davis T, Jenkins CN. Opening pathways to cancer screening for Vietnamese-American women: lay health workers hold a key. Prev Med. 1998;27(6):821–829. 10.1006/pmed.1998.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun KL, Thomas WL Jr, Domingo JLB, et al. Reducing cancer screening disparities in Medicare beneficiaries through cancer patient navigation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):365–370. 10.1111/jgs.13192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briant KJ, Sanchez JI, Ibarra G, et al. Using a culturally tailored intervention to increase colorectal cancer knowledge and screening among Hispanics in a rural community. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1283–1288. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Byrd TL, Wilson KM, Smith JL, et al. AMIGAS: a multicity, multicomponent cervical cancer prevention trial among Mexican American women. Cancer. 2013;119(7):1365–1372. 10.1002/cncr.27926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardarelli K, Jackson R, Martin M, et al. Community-based participatory approach to reduce breast cancer disparities in south Dallas. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(4):375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coronado GD, Beresford SA, McLerran D, et al. Multilevel intervention raises Latina participation in mammography screening: findings from ¡Fortaleza Latina! Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(4):584–592. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coronado GD, Golovaty I, Longton G, Levy L, Jimenez R. Effectiveness of a clinic-based colorectal cancer screening promotion program for underserved Hispanics. Cancer. 2011;117(8):1745–1754. 10.1002/cncr.25730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuaresma CF, Sy AU, Nguyen TT, et al. Results of a lay health education intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among Filipino Americans: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2018;124:1535–1542. 10.1002/cncr.31116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dignan MB, Michielutte R, Wells HB, et al. Health education to increase screening for cervical cancer among Lumbee Indian women in North Carolina. Health Educ Res. 1998;13(4):545–556. 10.1093/her/13.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn SF, Lofters AK, Ginsburg OM, et al. Cervical and breast cancer screening after CARES: a community program for immigrant and marginalized women. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):589–597. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Earp JA, Eng E, O’Malley MS, et al. Increasing use of mammography among older, rural African American women: results from a community trial. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):646–654. 10.2105/AJPH.92.4.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elder J, Haughton J, Perez L, et al. Promoting cancer screening among churchgoing Latinas: Fe en Accion/faith in action. Health Educ Res. 2017;32(2):163–173. 10.1093/her/cyx033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elkin EB, Shapiro E, Snow JG, Zauber AG, Krauskopf MS. The economic impact of a patient navigator program to increase screening colonoscopy. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5982–5988. 10.1002/cncr.27595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang CY, Ma GX, Handorf EA, et al. Addressing multilevel barriers to cervical cancer screening in Korean American women: A randomized trial of a community- based intervention. Cancer. 2017;123(6):1018–1026. 10.1002/cncr.30391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernández ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Effectiveness of Cultivando la Salud: a breast and cervical cancer screening promotion program for low-income Hispanic women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):936–943. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fiscella K, Humiston S, Hendren S, et al. A multimodal intervention to promote mammography and colorectal cancer screening in a safety-net practice. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(8):762–768. 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30417-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fouad MN, Partridge E, Dignan M, et al. Targeted intervention strategies to increase and maintain mammography utilization among African American women. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2526–2531. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goelen G, De Clercq G, Hanssens S. A community peer-volunteer telephone reminder call to increase breast cancer-screening attendance. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(4):E312–317. 10.1188/10.ONF.E312-E317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Han H-R, Song Y, Kim M, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening literacy among Korean American women: a community health worker-led intervention. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):159–165. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hatcher J, Schoenberg N, Dignan M, Rayens M. Promoting mammography with African-American women in the emergency department using lay health workers. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 2016;27(1):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haverkamp D, English K, Jacobs-Wingo J, Tjemsland A, Espey D. Effectiveness of interventions to increase colorectal cancer screening among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17. 10.5888/pcd17.200049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirst S, Mitchell H, Medley G. An evaluation of a campaign to increase cervical cancer screening in rural Victoria. Community Health Stud. 1990;14(3):263–268. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1990.tb00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoare T, Thomas C, Biggs A, Booth M, Bradley S, Friedman E. Can the uptake of breast screening by Asian women be increased? A randomized controlled trial of a linkworker intervention. J Public Health. 1994;16(2):179–185. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holt C, Litaker M, Scarinci I, et al. Spiritually based intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: screening and theory-based outcomes from a randomized trial. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):458–468. 10.1177/1090198112459651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holt CL, Tagai EK, Santos SLZ, et al. Web-based versus in-person methods for training lay community health advisors to implement health promotion workshops: Participant outcomes from a cluster-randomized trial. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(4):573–582. 10.1093/tbm/iby065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Howze EH, Broyden RR, Impara JC. Using informal caregivers to communicate with women about mammography. Health Commun. 1992;4(3):227–244. 10.1207/s15327027hc0403_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janz NK, Schottenfeld D, Doerr KM, et al. A two-step intervention of increase mammography among women aged 65 and older. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(10):1683–1686. 10.2105/AJPH.87.10.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jean-Jacques M, Kaleba EO, Gatta JL, Gracia G, Ryan ER, Choucair BN. Program to improve colorectal cancer screening in a low-income, racially diverse population: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):412–417. 10.1370/afm.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jo AM, Nguyen TT, Stewart S, et al. Lay health educators and print materials for the promotion of colorectal cancer screening among Korean Americans: A randomized comparative effectiveness study. Cancer. 2017;123(14):2705–2715. 10.1002/cncr.30568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katz ML, Tatum C, Dickinson SL, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007;110(7):1602–1610. 10.1002/cncr.22930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lam TK, Mc Phee SJ, Mock J, et al. Encouraging Vietnamese- American women to obtain Pap tests through lay health worker outreach and media education. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(7):516–524. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leone LA, Allicock M, Pignone MP, et al. Cluster randomized trial of a church-based peer counselor and tailored newsletter intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening and physical activity among older African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2016;43(5):568–576. 10.1177/1090198115611877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu G, Perkins A. Using a lay cancer screening navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening rates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(2):280–282. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.02.140209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Livaudais JC, Coronado GD, Espinoza N, Islas I, Ibarra G, Thompson B. Educating Hispanic women about breast cancer prevention: evaluation of a home-based promotoraled intervention. J Womens Health. 2010;19(11):2049–2056. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luque JS, Tarasenko YN, Reyes-Garcia C, et al. Salud es Vida: a cervical cancer screening intervention for rural Latina immigrant women. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32(4):690–699. 10.1007/s13187-015-0978-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma GX, Fang C, Tan Y, Feng Z, Ge S, Nguyen C. Increasing cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans: a community-based intervention trial. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(2 Suppl):36. 10.1353/hpu.2015.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ma GX, Lee M, Beeber M, et al. Community-clinical linkage intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening among underserved Korean Americans. Cancer Health Disparities. 2019;3:e1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marshall JK, Mbah OM, Ford JG, et al. Effect of patient navigation on breast cancer screening among African American Medicare beneficiaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):68–76. 10.1007/s11606-015-3484-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mishra SI, Bastani R, Crespi CM, Chang LC, Luce PH, Baquet CR. Results of a randomized trial to increase mammogram usage among Samoan women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(12):2594–2604. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mock J, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, et al. Effective lay health worker outreach and media-based education for promoting cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1693–1700. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Navarro AM, Senn KL, McNicholas LJ, Kaplan RM, Roppé B, Campo MC. Por La Vida model intervention enhances use of cancer screening tests among Latinas. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(1):32–41. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nguyen BH, Stewart SL, Nguyen TT, Bui-Tong N, McPhee SJ. Effectiveness of lay health worker outreach in reducing disparities in colorectal cancer screening in Vietnamese Americans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2083–2089. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nguyen TT, Le G, Nguyen T, et al. Breast cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans: a randomized controlled trial of lay health worker outreach. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(4):306–313. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Gildengorin G, et al. Papanicolaou testing among Vietnamese Americans: results of a multifaceted intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):1–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nguyen TT, Tsoh JY, Woo K, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and Chinese Americans: efficacy of lay health worker outreach and print materials. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):e67–e76. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nuño T, Martinez ME, Harris R, García F. A promotora-administered group education intervention to promote breast and cervical cancer screening in a rural community along the US-Mexico border: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(3):367–374. 10.1007/s10552-010-9705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O’Brien MJ, Halbert CH, Bixby R, Pimentel S, Shea JA. Community health worker intervention to decrease cervical cancer disparities in Hispanic women. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1186–1192. 10.1007/s11606-010-1434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Paskett E, Tatum C, Rushing J, et al. Randomized trial of an intervention to improve mammography utilization among a triracial rural population of women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(17):1226–1237. 10.1093/jnci/djj333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paskett ED, McLaughlin JM, Lehman A, Katz ML, Tatum C, Oliveri JM. Evaluating the efficacy of lay health advisors for increasing risk-appropriate Pap test screening: a randomized controlled trial among Ohio Appalachian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(5):835–843. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paskett ED, Tatum CM, D’Agostino R, et al. Community-based interventions to improve breast and cervical cancer screening: results of the Forsyth County Cancer Screening (FoCaS) Project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(5):453–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Percac-Lima S, Ashburner JM, Bond B, Oo SA, Atlas SJ. Decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally tailored patient navigation. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1463–1468. 10.1007/s11606-013-2491-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Percac-Lima S, Milosavljevic B, Oo SA, Marable D, Bond B. Patient navigation to improve breast cancer screening in Bosnian refugees and immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):727–730. 10.1007/s10903-011-9539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Russell KM, Champion VL, Monahan PO, et al. Randomized trial of a lay health advisor and computer intervention to increase mammography screening in African American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(1):201–210. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Wu P, Alisangco J, Castañeda SF, Kelly C. A cluster randomized controlled trial to increase breast cancer screening among African American women: the black cosmetologists promoting health program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(8):735. 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sauaia A, Min S-j, Byers T, Lack D, Apodaca C, Osuna D, et al. Church-based breast cancer screening education: impact of two approaches on Latinas enrolled in public and private health insurance plans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(4):A99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Savas LS, Atkinson JS, Figueroa-Solis E, et al. A lay health worker intervention to improve breast and cervical cancer screening among Latinas in El Paso, Texas: A randomized control trial. Prev Med. 2021;145:106446. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Studts CR, Tarasenko YN, Schoenberg NE, Shelton BJ, Hatcher-Keller J, Dignan MB. A community-based randomized trial of a faith-placed intervention to reduce cervical cancer burden in Appalachia. Prev Med. 2012;54(6):408–414. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sung JF, Blumenthal DS, Coates RJ, Williams JE, Alema-Mensah E, Liff JM. Effect of a cancer screening intervention conducted by lay health workers among inner-city women. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13(1):51–57. 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tanjasiri SP, Mouttapa M, Sablan-Santos L, et al. Design and outcomes of a community trial to increase pap testing in Pacific Islander women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28(9):1435–1442. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Taylor VM, Hislop TG, Jackson JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interventions to promote cervical cancer screening among Chinese women in North America. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002a;94(9):670–677. 10.1093/jnci/94.9.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Taylor VM, Jackson JC, Yasui Y, et al. Evaluation of an outreach intervention to promote cervical cancer screening among Cambodian American women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2002b;26(4):320–327. 10.1016/S0361-090X(02)00055-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Taylor VM, Jackson JC, Yasui Y, et al. Evaluation of a cervical cancer control intervention using lay health workers for Vietnamese American women. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1924–1929. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thompson B, Carosso EA, Jhingan E, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to increase cervical cancer screening among rural Latinas. Cancer. 2017;123(4):666–674. 10.1002/cncr.30399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tong EK, Nguyen TT, Lo P, et al. Lay health educators increase colorectal cancer screening among Hmong Americans: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2017;123(1):98–106. 10.1002/cncr.30265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Walsh JM, Salazar R, Nguyen TT, et al. Healthy colon, healthy life: a novel colorectal cancer screening intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(1):1–14. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang X, Fang C, Tan Y, Liu A, Ma GX. Evidence-based intervention to reduce access barriers to cervical cancer screening among underserved Chinese American women. J Womens Health. 2010;19(3):463–469. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Warner EL, Martel L, Ou JY, et al. A Workplace-based intervention to improve awareness, knowledge, and utilization of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings among Latino service and manual labor employees in Utah. J Community Health. 2019;44(2):256–264. 10.1007/s10900-018-0581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Weinrich SP, Weinrich MC, Stromborg MF, Boyd MD, Weiss HL. Using elderly educators to increase colorectal cancer screening. Gerontologist. 1993;33(4):491–496. 10.1093/geront/33.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.White K, Garces IC, Bandura L, McGuire AA, Scarinci IC. Design and evaluation of a theory-based, culturally relevant outreach model for breast and cervical cancer screening for Latina immigrants. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(3):274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wong CL, Choi KC, Chen J, Law BMH, Chan DNS, So WKW. A community health worker-led multicomponent program to promote cervical cancer screening in south Asian women: a cluster RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(1):136–145. 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cancer screening: interventions engaging community health workers - breast cancer. 2019. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/SET-Breast-Cancer-Screening-CHW-508.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 109.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cancer screening: interventions engaging community health workers - cervical cancer. 2019. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/SET-Cervical-Cancer-Screening-CHW-508.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 110.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cancer screening: interventions engaging community health workers - colorectal cancer. 2019. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/SET-Colorectal-Cancer-Screening-CHW-508.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 111.The Community Health Worker Core Consensus Project. C3 Project findings: roles & competencies. 2020. https://www.c3project.org/roles-competencies. Accessed October 12, 2022.

- 112.Bureau of Labor Statistics USDoL. Health Education Specialists and Community Health Workers. Occupational Outlook Handbook. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/community-and-social-service/health-educators.htm. Accessed October 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stang A, Jöckel KH. The Impact of Cancer Screening on All-Cause Mortality. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(29–30):481–486. 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Seven M, Akyüz A, Robertson LB. Interventional education methods for increasing women’s participation in breast cancer screening program. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(2):244–252. 10.1007/s13187-014-0709-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bandura A Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Calderón-Mora J, Byrd TL, Alomari A, et al. Group versus individual culturally tailored and theory-based education to promote cervical cancer screening among the underserved Hispanics: a cluster randomized trial. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34(1):15–24. 10.1177/0890117119871004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Larkey LK, Herman PM, Roe DJ, et al. A cancer screening intervention for underserved Latina women by lay educators. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(5):557–566. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Spalluto LB, Audet CM, Murry VM, et al. Group versus individual educational sessions with a promotora and Hispanic/Latina women’s satisfaction with care in the screening mammography setting: a randomized controlled trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213(5):1029–1036. 10.2214/AJR.19.21516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State Law Face Sheet: A Summary of State Community Health Worker Laws. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/SLFS-Summary-State-CHW-Laws.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2022.