Abstract

Background:

Though a growing body of research suggests that greater positive psychological well-being in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may be protective, existing brain–gut behavior therapies primarily target negative psychological factors. Little is known about how positive psychological factors in IBS relate to IBS symptoms, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), or adherence to key health behaviors, such as physical activity and diet modification. Accordingly, per the ORBIT model of behavioral treatment development for chronic diseases, we explored potential connections between psychological constructs and IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement (physical activity and dietary modification), and HRQoL in a qualitative study to inform the development of a novel brain–gut behavior therapy.

Methods:

Participants with IBS completed self-report assessments and semi-structured phone interviews about relationships between positive and negative psychological constructs, IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement, and HRQoL.

Key Results:

Participants (n = 23; 57% female) ranged in age from 25 to 79 (mean age = 54). IBS subtypes were similarly represented (IBS-diarrhea [n = 8], IBS-constipation [n = 7], and IBS-m ixed [n = 8]). Participants described opposing relationships between positive and negative psychological constructs, IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement, and HRQoL, respectively, such that experiencing positive constructs largely mitigated IBS symptoms, boosted health behavior participation, and improved HRQoL, and negative constructs exacerbated symptoms, reduced health behavior participation, and worsened HRQoL.

Conclusions and Inferences:

Participants with IBS linked greater positive psychological well-being to moderated IBS symptoms and better HRQoL and health behavior participation. An intervention to cultivate greater well-being may be a novel way to mitigate IBS symptoms, boost health behavior participation, and improve HRQoL in IBS.

Keywords: functional gastrointestinal disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, psychology, positive, psychosomatic medicine

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a disorder of gut–brain interaction (DGBI; also known as functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder)1 characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, represents a major clinical and public health problem. IBS affects approximately 11% of adults and accounts for up to 50% of all GI referrals in the United States.2 It is associated with high psychiatric comorbidity (as many as half of all patients with IBS may have a comorbid psychiatric disorder),3,4 high healthcare costs ($30 billion annually),5 and severe impairments in HRQoL (often more severe than many other chronic conditions).6 Current treatments are focused on symptom reduction rather than cure and include lifestyle modifications (e.g., dietary changes, increased exercise), patient education, pharmacotherapy, and brain–gut behavior therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs).7

Conceptualized as a biopsychosocial disorder,8 there has been an extensive prior examination of relationships between IBS and psychological factors9—both those that contribute to and those that protect against the development and maintenance of IBS symptoms. Self-reported depression and anxiety confer a twofold increased risk for IBS onset,10 and anxiety/mood disorders and the DGBI more broadly appear to have shared genetic susceptibilities.11 Comorbid psychiatric symptoms, as well as maladaptive or negative psychological constructs such as catastrophizing, symptom hypervigilance, and illness-specific cognitions, have been shown to exacerbate IBS symptomatology, amplify visceral hypersensitivity, and worsen quality of life.3,8,9,12,13 CBT, a well-established brain–gut psychotherapeutic approach, focuses on unlearning these perpetuating factors—through which IBS symptom improvement is thought to be primarily mediated—as well as treating comorbid psychiatric symptoms.14

Conversely, there is a growing body of research examining the potentially protective role of greater positive psychological well-being in IBS. Well-being transcends traditional definitions of quality of life and is comprised of a variety of positive psychological constructs, such as purpose in life, resilience, optimism, positive affect, and joy.15 Compared with healthy populations, individuals with IBS have lower levels of well-being,16–18 as well as lower levels of specific positive psychological constructs such as resilience,17,19–21 positive affect,22 self-efficacy,21,23 and emotion regulation.24 Lower well-being, in turn, is associated with impaired physical health (e.g., more severe IBS symptoms19,20,25), greater depression25–28 and anxiety,25,27,28 and worse HRQoL among patients with IBS.19,25,28,29 Improving well-being is becoming an aspirational goal in the care of digestive disorders.30,31 Interventions to cultivate greater well-being have shown promise in populations with other chronic illnesses32,33 and represent an area of much-needed investigation in IBS.30

Though prior research has examined the quantitative contribution of psychological factors to the development and severity of IBS, there has been relatively less qualitative examination of these factors. Furthermore, there has been little research on how psychological factors might relate to HRQoL or adherence to key health behaviors, such as physical activity or diet modification. Accordingly, to inform the development of a novel brain–gut behavior therapy per the ORBIT model of behavioral treatment development for chronic diseases,34 we completed a rigorous qualitative study to better understand potential connections between psychological constructs and IBS symptoms, engagement in health behaviors, and HRQoL among individuals with IBS.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

This qualitative study was the first step in a multiphase program—informed by the ORBIT model of behavioral treatment development34—to create a novel brain–gut behavior therapy to promote well-being in individuals with IBS. We performed 45-min-long, semi-structured qualitative interviews with individuals with IBS to explore psychological constructs as they relate to (1) IBS symptoms, (2) engagement in health behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity), and (3) HRQoL. This study followed the consolidated criteria for conducting and reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines.35 The Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board approved the research protocol (IRB #2020P001895), and all participants provided informed consent prior to participating in any study procedures.

2.2 |. Participants

Eligible participants were adults aged 18 or older with a diagnosis of IBS meeting Rome IV criteria.36 Exclusion criteria included limited English proficiency, lack of telephone access, cognitive deficits limiting participation (measured with a 6-item screen37), and current manic episode, psychosis, or active substance use disorder limiting participation (assessed via the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview38). Participants were purposively sampled from an urban academic medical center between October 2020 and August 2021, through GI clinician referral and using the institution’s research patient data registry. Potentially eligible patients were provided with study fact sheets by their referring GI clinicians or mailed opt-out letters if identified through the research patient data registry. All patients were screened for inclusion/exclusion criteria by phone. Recruitment continued until thematic saturation was reached39 within each sex and IBS subtypes (i.e., IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS-constipation (IBS-C), and IBS-mixed (IBS-M)) stratum.

2.3 |. Data collection

2.3.1 |. Participant characteristics and baseline assessments

Demographic and medical data were obtained at enrollment via self-report and electronic medical record review. Following the qualitative interview, participants completed self-report assessments through an online survey on REDCap. Self-report assessments included validated measures of optimism (Life Orientation Test-Revised [LOT-R]40), positive affect (positive affect items of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [PANAS]41), depression and anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]42), gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety (Visceral Sensitivity Index [VSI]43), IBS symptom severity (the IBS Symptom Severity Scale [IBS-SSS]44), IBS HRQoL (the IBS Quality of Life Instrument [IBS-QOL]45), pain catastrophizing (the Pain Catastrophizing Scale [PCS]46), physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire [IPAQ]44), and disordered eating (Nine-Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake disorder screen [NIAS]).47

2.3.2 |. Semi-structured qualitative interviews

Participants completed semi-structured, 45-min-long qualitative interviews by phone. Interview guides were developed based on the research group’s expertise with IBS as well as prior qualitative research investigating emotional experiences/constructs in the context of chronic illness.48–51 A multidisciplinary team reviewed the interview guide and consultation from a qualitative research expert was also obtained. See Table S1 for sample interview questions. All interviews (completed by E.N.M., a psychiatrist) were audio-recorded and then transcribed using a professional transcription service.

2.4 |. Analysis

2.4.1 |. Qualitative analysis

Transcribed interviews were uploaded to Dedoose Software (Sociocultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA). A coding framework was developed prior to analysis based on the iterative review of transcripts and using directed content analysis,52 following COREQ guidelines.35 Consultation from a qualitative research expert was also obtained. Two coders (E.N.M. and L.E.H.) independently coded the data and met weekly to review the coding for each interview, with all discrepancies resolved by consensus. Themes were derived from the iterative review of the coded data.

2.4.2 |. Descriptive statistics analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, SDs, frequencies, and ranges) were calculated to describe the population’s demographics, medical conditions, and self-reported characteristics.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Participant characteristics

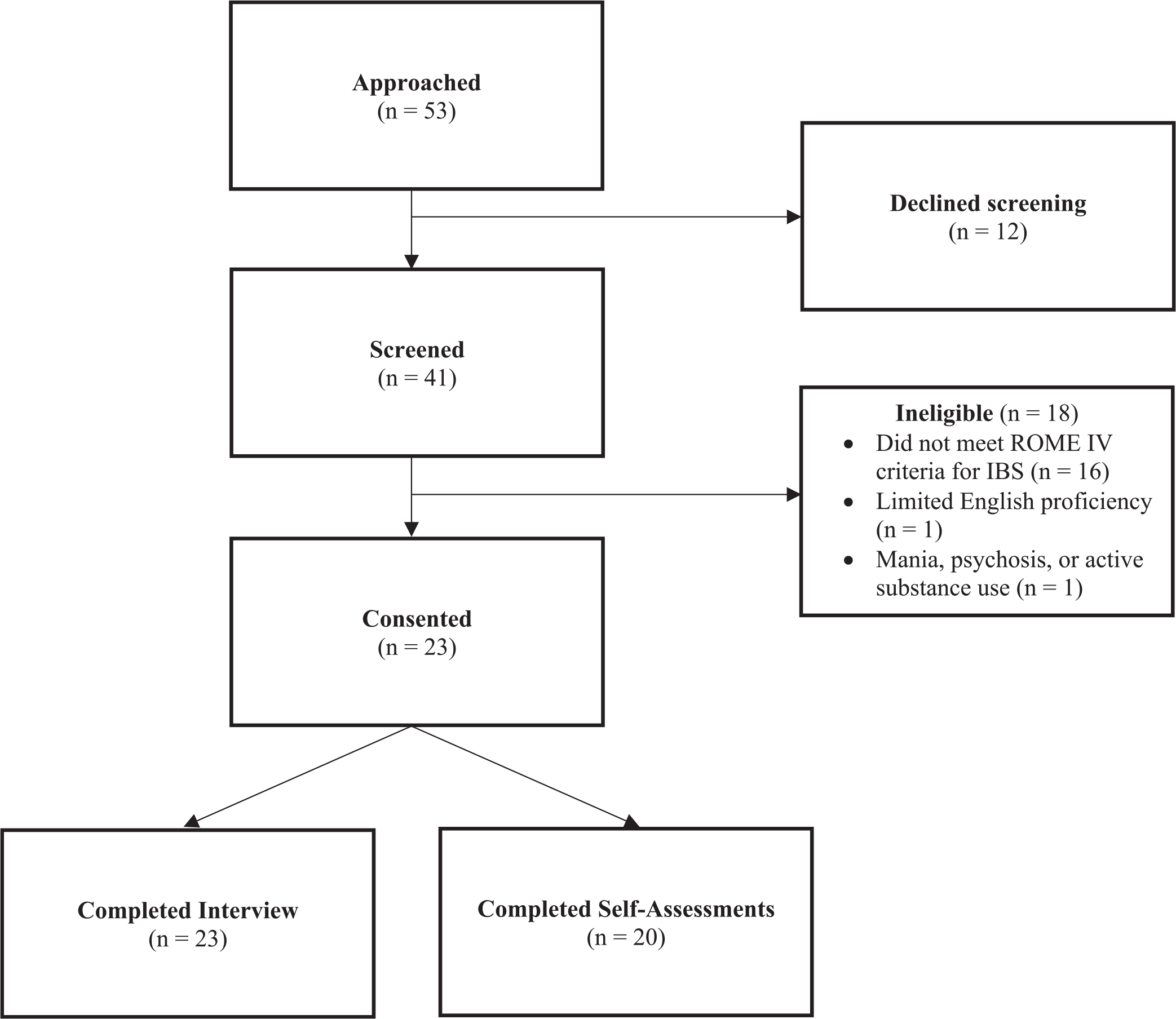

A diagram of study enrollment is explained in Figure 1. Of 53 potentially eligible participants, 12 declined screening, and 41 were screened by phone. Of those screened, 18 were found to be ineligible, and 23 (56%) enrolled and completed the qualitative interview. Twenty participants (87%) completed the self-report assessments. All completed interviews were included in the analyses.

FIGURE 1.

Enrollment

Baseline demographic, medical, and psychological characteristics of participants are included in Table 1. The mean age was 54 years (range 25–79) and 57% (n = 13) were female. Approximately one-third of participants had IBS-D (n = 8) versus IBS-C (n = 7) versus IBS-M (n = 8). Most participants had a history of depression (52%) or anxiety (70%) documented in their electronic medical record, though the HADS subscales suggested minimal to mild current symptoms (HADS-D (mean = 5.4, SD = 3.7); HADS-A (mean = 7.1, SD = 3.3)). Scores on optimism (mean = 14.0, SD = 5.4) and positive affect (mean = 32.1, SD = 8.3) were similar to normative samples.53–55 The mean score on the IBS-SSS (mean = 243.5, SD = 98.8) was consistent with moderate IBS symptom severity.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics (N = 23) and self-assessments (n = 20)

| Characteristics | n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, years, mean (range) | 54 (25–79) |

| Female | 13 (57%) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 2 (9%) |

| Black or African American | 1 (4%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) |

| White | 19 (83%) |

| Ethnicity—Hispanic/Latino | 1 (4%) |

| Medical characteristics | |

| IBS subtype | |

| IBS-diarrhea | 8 (35%) |

| IBS-constipation | 7 (30%) |

| IBS-mixed | 8 (35%) |

| Other GI disorders | |

| Other DGBI | 1 (4%) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0 (0%) |

| GERD | 17 (74%) |

| Celiac disease | 1 (4%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 3 (13%) |

| Fibromyalgia | 6 (26%) |

| Migraines | 9 (39%) |

| Autoimmune condition | 2 (9%) |

| History of psychiatric conditions | |

| Depression | 12 (52%) |

| Anxiety | 16 (70%) |

| PTSD | 3 (13%) |

| Eating disorder | 0 (0%) |

| Substance use disorder | 2 (9%) |

| Other psychiatric conditions | 4 (17%) |

| Self-assessmentsa | |

| Optimism (LOT-R; range: 0–24) | 12.2 (3.4) |

| Positive affect (PANAS; range: 10–50) | 32.1 (8.3) |

| Depression (HADS-D; range: 0–21) | 5.4 (3.7) |

| Anxiety (HADS-A; range: 0–21) | 7.1 (3.3) |

| GI symptom-specific anxiety (VSI; range: 0–75) | 50.4 (18.7) |

| IBS symptom severity (IBS-SSS; range: 0–500) | 243.5 (98.8) |

| IBS HRQoL (IBS-QOL; range: 0–100) | 64.6 (22.1) |

| Pain catastrophizing (PCS; range: 0–52) | 12.9 (10.1) |

| Physical activity (IPAQ; MET-minutes per week) | 2410.1 (2514.1) |

| Eating difficulties (NIAS; range: 0–45) | 14.5 (9.5) |

Abbreviations: DGBI, disorder of gut-brain interaction; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI, gastrointestinal; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-SSS, IBS-Symptom Severity Scale; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; LOT-R, Life Orientation Test-Revised; NIAS, Nine nine-item avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder screen; PANAS, positive and negative affect schedule; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS); VSI, Visceral Sensitivity Index.

Self-assessment data missing for n = 3.

3.2 |. Qualitative outcomes

We identified several key themes regarding the relationships between psychological constructs and IBS symptoms, health behaviors, and HRQoL (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Main themes in qualitative analysis

| Theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Positive psychological constructs | |

| Bidirectional relationships between positive psychological constructs and fewer IBS symptoms | “Being happy does not magically make my stomach feel better or any of the symptoms. Now, if I’m in a good place in my life, like work is good, good relationships at work, good support, an understanding partner, parents that, now, they understand - they get it - it makes your day-to-day easier...So in that regard, having positivity and feeling good about the people I was surrounded by made it a little bit easier to handle [my IBS symptoms] (ID 13).” “...when I wasn’t getting these pains more consistently like I am now...on a day where there’s nothing bothering me physically [in terms of IBS symptoms] and I do not feel tired, then I always have positive emotions (ID 18).” |

| Bidirectional relationships between positive psychological constructs and increased health behaviors | “So if I’m happy I’m energetic or I’m excited about anything I’m like, ‘Yeah. Okay. Yeah. That’s great. Let us go for a walk’ (ID 9).” “I have like this motto, bright neon pink, ‘No excuses.’ Like there’s no excuse because you could use that every day. ‘Oh, it’s too cold. I do not feel like it. Blah, blah, blah.’ So that’s my thing for this year, no excuses. So I bundled up as much as I could, and I only lasted [on my walk for] 30 minutes. But I said, ‘30 min is better than nothing.’ ...But I was so psyched to go on a walk. I was really psyched because I said, ‘I’m not going to let the weather get to me’ (ID 10).” “I mean, I feel accomplished. I feel really excited. I really enjoy kind of feeling like I get a workout in every day because I know it’s good for me. It feels kind of-- it got the juices flowing. Just I’m really good, do things the rest of the day. So I came home and I cut the lawn and did a pile of other things after work because I was really energized and feeling good (ID 17).” |

| Relationships between positive psychological constructs and improved HRQoL | “Well, I think when you are feeling positive, you have much more well-being (ID 14).” “I think it’s a pretty strong connection there...Yeah, it’s a really strong connection...Right now, I’m in a better [mental] state now, and definitely my quality of life is in a better state (ID23).” |

| Interconnected relationships between positive psychological constructs, fewer IBS symptoms, increased health behaviors, and improved HRQoL | “I’m one of those people that, when I feel like I’m doing something, I’m accomplishing something, or I did something great, I feel better [physically and emotionally] and I do better. So on days, like today I cannot go outside because of the weather, but when I walk four miles to the beach, I feel excited and happy, and...I feel better, feel more achievement, and I can do more. So I’ll come home and I’m able to do things that I had put off, like maybe vacuum clean the floor, put up some pictures, stuff like that (ID 1).” |

| Negative psychological constructs | |

| Bidirectional relationships between negative psychological constructs and worse IBS symptoms | “I think that it’s very strong. I mean, I notice the negative effects much more than I’ve ever-- I’ve never even thought about how being happy or content has affected my IBS, but being stressed just may affect it very directly and very quickly. Other negative emotions like being sad does not, or being upset does not. But an acute stress or even just ongoing stress for a long time, I’ll feel sick of it. So there’s definitely a direct relationship there... I mean, usually, it’s not the constant stress that I have. Usually, it’s an episode of stress, maybe a really stressful interview that I have to prepare for, or something like that, that can cause symptoms (ID 11).” “Yeah, like it [IBS] affects my mood. Yeah, it does. Yeah it definitely does, because if I have, I would say upset stomach, or cramps, I’m definitely more cranky, and probably a little snappy (ID1).” “I feel like it’s not fair. How could I have lived a completely normal life up until my 20 s, and then all of the sudden, I am constantly feeling sick? I feel angry. I feel like I’ve had a lot taken from me. I feel like it’s just another element of my life that has made living harder. It feels really unfair and infuriating...imagine having a stomach ache every day for an entire year, and then having the stress of, ‘I need to go to work. I need to make money. I do not have sick time.’ You spiral. You go down, and you feel like you are just, you are a mess. You cannot achieve things. You’re not successful. And then you spiral, and that becomes anxiety, and that anxiety just begins to encompass every aspect of your life (ID13).” |

| Bidirectional relationships between negative psychological constructs and reduced engagement in physical activity and healthy eating patterns | “If I’m feeling depressed or sad, I do not want to go out. I do not want to put clothes on. I do not want to put my shoes on. I do not want to brush my hair. So I definitely do not want to go for a walk... So my health kind of takes a backburner to it which has been the case with work and school my whole life. My health has always taken a back burner to work and school (ID 9).” “Yeah, because if I’m not happy, I do not make the best decisions. And I do not do what I’m supposed to do, I do not eat right...I find myself being an emotional eater. So if I’m sad, I want a bag of chips (ID 1).” |

| Dietary modifications increase negative psychological constructs | “It can be a point of insecurity sometimes. And...it can, certainly, get in the way of social events sometimes or having anxiety regarding food I eat and things like that...(ID 5).” “So it’s almost I have to pay more attention to see what ingredients are. I do not cook with anything I know will throw me. But as I said, sometimes-- but nowadays, it’s takeout, obviously. When I get some takeout, I really have to pay more attention...It’s just more of a kind of mind exercise if I’m going to get takeout, or my husband and I are going to go out to restaurants. I mean, I’m the one at the table that says, ‘Can you not have A, B, C, D?’...I feel limited and I feel discouraged (ID 6).” |

| Relationships between negative psychological constructs and worse HRQoL | “So that was the saddest time in my life...and I had very poor quality of life. I was sad all the time. And I mean, I was going to work, and I mean, I wasn’t enjoying anything. And people at work had asked me if I was sick or something because I must have looked stressed all the time. It was horrible. It was very, very hard (ID2).” |

| Interconnected relationships between negative psychological constructs and worse IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement, and HRQoL | “I certainly feel a very direct correlation between [them]. And the days that I-- I think it’s probably, again, going one way where if I am having symptoms, GI symptoms, flare-ups, things like that, it certainly heightens a lot of the more negative emotions and makes it really difficult to get sort of the things I need to get done for the day and kind of being motivated to do them as well (ID 5).” |

| Positive versus negative psychological constructs | |

| Opposing effects on IBS symptoms | “So in the same way that these negative emotions, negative feelings, not feeling great, kind of brings the IBS symptoms to my attention or makes them more pronounced, feeling positive and experiencing positive emotions take away from my almost complete awareness of how my stomach and gut feels. It’s almost like it puts it on the back burner. I’m experiencing something in that moment that just kind of allows me to-- I mean, obviously, it does not shut off the pain, or perhaps it does lessen it. Perhaps my mind is not as focused on it, but I feel like the discomfort is less. Or perhaps my tolerance is higher (ID13).” “I do notice that I flare up more when I’m really stressed out and have a lot of anxiety. If I’m on vacation and relaxed it’s less likely for me to have a flare-up than during the most important weeks of the year at work where it’s crunch time and I’m non-stop busy and really stressed out the most. I’m in school right now. So when my paper’s due it’s real high anxiety and real stress-inducing and then all of a sudden my stomach flares up and that’s even more anxiety. It’s definitely more of a negative emotion that I notice that I flare up more when I’m sad or depressed or irritable and just generally stressed and tired (ID 9).” |

| Opposing effects on HRQoL | “Seems pretty critical. I mean, waking up on the wrong side of the bed does not change the day; it’s just the way you see the day. So going through the day with a positive mindset is critical for enjoying and appreciating the day for what it is (ID 17).” “I mean, if you are feeling happy, excited about life, you are more likely to have a higher quality of life. So I think because a lot of it’s in the eyes of the beholder, I guess. If you are feeling particularly bad, then everything’s going to suck, and you are going to feel like your life is not going great (ID 22).” |

| Opposing interconnected relationships with IBS symptoms, health behaviors, and HRQoL | “I’d say when I’m happier, when I feel better about myself, I take better care of myself. I’m more likely to do smaller, positive things for myself, my family. If I’m down, then I’m more likely to eat more stuff. I’m more likely to stress-eat. I’m probably very guilty of that...I’ll eat way more than I need to...And I’ll overdo it. And the next day, I feel like crap. But when I’m more-- when I’m a little bit more positive, I’m less likely to go kind of that far. I’m more likely to be like, ‘No, I do not need that,’ and kind of practice more self-control and just better habits in general, I guess (ID21).” |

Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality of life; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

3.2.1 |. Positive psychological constructs

Participants reported that a variety of positive psychological constructs were associated with improvements in IBS symptoms, health behaviors, and HRQoL. Across interviews and question types, the most commonly reported positive psychological construct was “sense of calm/relaxation,” followed by “joy/happiness,” “connectedness,” “gratitude,” “pride/sense of accomplishment,” “determination/motivation,” “enthusiasm/increased energy,” “feeling understood/validated,” “contentment,” “inspiration,” “optimism/hope,” and “fulfillment.”

Positive psychological constructs and IBS symptoms

Participants shared their perceptions of the relationships between positive psychological constructs and IBS symptoms—both how positive constructs impact IBS symptoms and vice versa.

Positive psychological constructs impact IBS symptoms.

When asked about the relationships between emotions and IBS symptoms, many participants noted that experiencing greater positive emotions—in particular a sense of calm and relaxation—mitigates their experience of IBS symptoms. For example, one participant noted, “…sometimes I’ll just put my hands on my stomach and meditate, relax, if I feel a pain or something, and then [the pain] will just dissipate (ID 14).” For some participants, the connection between experiencing positive constructs and IBS symptoms was quite strong and direct, for example, “So I know if I’m in a great mood, then my stomach should be okay (ID 10),” whereas for other participants, the relationship was present but not as definitive: “The psychology and emotional stuff isn’t like a perfect correlation [to IBS symptoms]. But I think it helps. It doesn’t solve the issue, but it definitely helps (ID 23).”

IBS symptoms impact positive psychological constructs.

Many participants noted that experiencing fewer IBS symptoms was often associated with a boost in positive emotions. For example, one participant noted, “…if I’m feeling pretty good for the day physically [in terms of IBS symptoms], then I’m also just in a good place in my head. I’m happy, I’m peaceful, I feel relaxed (ID 22).”

Positive psychological constructs and health behaviors

Participants described reciprocal relationships between positive psychological constructs and health behaviors, such that experiencing positive constructs led to greater engagement in health behaviors, and engaging in health behaviors boosted positive constructs. Notably, when asked about relationships between emotions and health behaviors, links between positive constructs and physical activity were more often noted than links to dietary modifications.

Positive psychological constructs boost engagement in health behaviors.

Nearly, all participants noted a greater likelihood to participate in physical activity if experiencing greater positive emotions in general, for example, “I think if my emotions are more positive, I’m more inclined to exercise (ID 7).” Other participants felt that this relationship was also true for engaging in healthy eating patterns: “…if I’m in a good mood, and feel well, then I tend to exercise and eat better, and am more conscious of the things that I put in my body (ID 1).”

Engaging in health behaviors boosts positive psychological constructs.

The relationship between physical activity and positive psychological constructs was particularly robust, with all participants describing a boost in positive emotions—particularly a sense of accomplishment, motivation, focus, joy, happiness, relaxation, and greater energy—after participating in physical activity. For example, when asked about specific emotions experienced after exercising, one participant shared: “I felt good. I felt happy, very uplifted, again, joyful…I guess the word is grateful…A sense of accomplishment…I definitely feel that it was an increase in motivation, looking forward to going back out that evening [to walk again] (ID 13).” Some participants also noted similar effects from eating a good diet: “…basically you are what you eat. What you put in is what comes out, and if you can do better in terms of eating, it may help you feel better. And that’s physically and emotionally (ID 1).”

Positive psychological constructs and HRQoL

When asked about the relationship between emotions and HRQoL, and whether their emotions affect their HRQoL, participants uniformly reported that experiencing greater positive psychological constructs improved their HRQoL. As a representative example, one participant shared: “Well, I definitely feel like when I have more positive emotions my quality of life is better… I feel like the happier I am or the more relaxed I am, I feel better about life (ID 9).”

Interconnected relationships between positive psychological constructs, IBS symptoms, health behaviors, and HRQoL

Many participants noted robust interconnected relationships between health behavior engagement, reduced IBS symptoms, improved HRQoL, and greater positive psychological constructs: “I just feel better when I go out [for a walk]. And I think digestion moves along…like I can count on things being more of a normalized pattern instead of being erratic. As far as feeding into it…I think emotions play a part…So I think forcing yourself and getting out, and getting your mind off of it can help [IBS symptoms]…Even just going back to yesterday, I think I was more productive. I got a lot done because I went out for a walk early. I came back. I was ready to do what I had to do, and I felt like I got everything done. And just my mood was just…really good. And I think the whole thing ties in…(ID 10).” Other participants echoed the same sentiment: “…what I discovered, [exercising] is a good thing that helped me with IBS. Certainly, it did… because it removed the tension, and once it removed the tension, it removed my abdominal pain (ID 20).” And last, another participant stated: “When I have great days [in terms of IBS symptoms], I’m thrilled. I probably overdo it because I’m just so happy to be out and about and I’m happy to do whatever I feel like for the day…just a little browsing, shopping, or going for that longer walk. It makes you feel great that you can do more (ID 6).”

3.2.2 |. Negative psychological constructs

Participants reported that a variety of negative psychological constructs exacerbated each of the examined areas (i.e., IBS symptoms, health behaviors, and HRQoL). Across interviews and question types, the most commonly reported negative psychological construct was “anxiety,” followed by “helplessness/lack of control/feeling limited,” “stress/tension,” “depression/sadness,” “anger/frustration,” “lack of motivation,” “fatigue,” “discouragement,” “feeling uncomfortable,” “isolation/feeling unsupported/lack of understanding,” “embarrassment,” “unfairness,” “hopelessness,” and “disgust.”

Negative psychological constructs and IBS symptoms

Participants described bidirectional aggravating relationships between negative psychological constructs and IBS symptoms.

Negative psychological constructs exacerbate IBS symptoms.

When asked about the relationship between emotions and IBS symptoms, many participants noted that negative psychological constructs—in particular, stress and anxiety—exacerbate IBS symptoms: “I think they are connected…I think there is a relationship between your feelings or your state of mind, your stress, your anxiety, with IBS… So the stress is related to my constipation. That’s for sure (ID15).” Similarly, another participant shared: “I don’t have that job anymore where I was being just really stressed out by one individual. It got so every time I saw the individual, I’d have diarrhea. So every time I went into the office, I’d get diarrhea. So that trigger is gone…But if I saw that person, I probably would get diarrhea (ID 14).” Other participants felt that their negative emotions tended to land in their gut: “I’m not a person who is conscious of a lot of anxiety, but I think my gut feels it (ID 8),” and, “Because I’ve always been a very nervous person…I’ve always had a very nervous stomach because of it ever since I was a kid (ID 18).”

IBS symptoms increase negative psychological constructs.

Similarly, participants also noted how IBS symptoms amplify negative psychological constructs, in particular, anxiety, embarrassment, and anger. Regarding anxiety, one participant noted: “It definitely makes me anxious…If I’m having a flare-up, and it’s been like a few days, I’m starting to be anxious that it’s going to get worse (ID 5).” Other participants highlighted the experiences of embarrassment and anger: “I would say that would be the strongest emotion, embarrassed. I’m really not someone that gets caught up in shame, but more just embarrassed. And sometimes I could be a little angry, like, ‘Why me? Why does this shit have to happen to me?’ (ID 14).”

Negative psychological constructs and health behaviors

Participants shared their perceptions of the relationships between negative psychological constructs and health behaviors—both how negative constructs impact health behavior engagement and vice versa.

Negative psychological constructs reduce engagement in health behaviors.

Participants noted that experiencing negative psychological constructs reduced engagement in physical activity and healthy eating patterns. In terms of physical activity, one participant shared: “If I’m in a bad spot - if I’m feeling depressed or something or I’m stressed out for some reason, I may not bother to go exercise (ID 3).” And in terms of diet, one participant noted: “I’m definitely a stress eater. 100% I can tell you that when I’m stressed-out food is around me. I’ll wake up in the middle of the night and just snack on food. My husband can always tell when I’m really stressed out because I just buy a whole bunch of junk food at the supermarket and keep it within arm range (ID 9).”

Health behaviors contribute to negative psychological constructs.

Some participants noted how engaging in dietary modifications in particular (not physical activity) was challenging and could sometimes lead to negative emotions: “But in my case, because I can’t have those, every time I’m going to go out to have something to eat, either by myself or with others, or going over to a relative’s house, that is always a bit of a buzzkill for people… And so it ends up being a complication. And on a social level for people, food complications are— I think, even if it’s not shared, it’s experienced as kind of a drag, a negative…(ID 3).”

Negative psychological constructs and HRQoL

When asked about the relationship between emotions and HRQoL, and whether their emotions affect their HRQoL, all participants noted that negative psychological experiences—including those generated by IBS symptoms—worsened HRQoL. As a representative example, one participant shared: “…and when I’m feeling negative emotions or I’m really stressed out, I feel like my quality of life just tanks. I’m depressed, I don’t want to see my friends, I just want to focus on work or school and getting through what I have to get through. I don’t go to anybody…so I kind of bottle up all these emotions. Yeah. It’s stress-inducing… when I’m stressed or sad or depressed it’s like life sucks and that’s when I start hating on myself, ‘Oh, why do I have the IBS? If I didn’t have IBS my life would be so much better. I could go out and do things. I could go see people (ID 9).”

Interconnected relationships between negative psychological constructs, IBS symptoms, health behaviors, and HRQoL

Participants noted how a cascade of negative events could follow IBS symptom flares: “Especially when I’m having a flare-up, emotionally, I kind of – I emotionally tank. I end up going from being positive to all of a sudden, it creeps up on me. And next thing you know, I just feel like the day’s ruined or the week’s ruined, and I’m going to get really thrown off, and I spiral kind of emotionally. And that ends up probably being as bad for the rest of the day as the flare-up itself (ID 17).” Another participant echoed a similar sentiment: “Oh, it’s correlated [the relationships between emotions, IBS symptoms, and HRQoL]. Very much so. Because, again, if I’m having a bad day, it does eventually hit my stomach and my stomach will be off…if I’m not feeling well and my stomach’s off, it’s almost like a double whammy. I mean, that’s not a good day (ID 10).” Similarly, another participant noted how IBS symptoms contribute to negative psychological experiences and thereby worsen HRQoL: “It makes you think all the time. You start to build your life around the symptoms. So it becomes almost like a dominating factor…you also have to essentially kind of build your life around this. So I would say, well, it’s very difficult. It’s very difficult to deal with (ID 20).”

3.2.3 |. Positive and negative psychological constructs

Positive and negative psychological constructs have opposing effects on IBS symptoms

Many participants also shared the powerful ways in which their emotions affected their IBS symptoms in opposite ways: “So in the same way that these negative emotions, negative feelings, not feeling great, kind of brings the IBS symptoms to my attention or makes them more pronounced, feeling positive and experiencing positive emotions take away from my almost complete awareness of how my stomach and gut feels. It’s almost like it puts it on the back burner. I’m experiencing something in that moment that just kind of allows me to-- I mean, obviously, it doesn’t shut off the pain, or perhaps it does lessen it. Perhaps my mind isn’t as focused on it, but I feel like the discomfort is less. Or perhaps my tolerance is higher (ID 13).” Similarly, another participant noted: “There are times when…I get in the car and it’s a long car ride and I’m a bit worried about being away from a bathroom for a while, for hours, and the worry starts the feeling of the flare-up, and I start feeling like, ‘Oh my God, actually, I think I need to-- I actually think it’s happening right now.’ And then what I try to do is I try to think about all the times when I haven’t had a flare-up when going out and thinking about those and deep breathing, and then it passes. The feeling passes. It’s like, ‘Oh, that’s totally a function.’ Just like the feeling was a function of the negative feeling, the relief I’m feeling ended up being a function of positive feelings around it, the positive emotions around it (ID 17).”

Positive and negative psychological experiences have opposing effects on HRQoL

Similarly, many participants noted strong opposing effects of their psychological experiences on their HRQoL: “For me, having a good attitude definitely made my life better. Having a bad attitude definitely made my life worse. It’s very obvious (ID 12).” Similarly, another participant noted: “Seems pretty critical. I mean, waking up on the wrong side of the bed doesn’t change the day; it’s just the way you see the day. So going through the day with a positive mindset is critical for enjoying and appreciating the day for what it is (ID 17).” Another participant echoed a similar sentiment: “Well, I think if you were a down person no matter what you do, the quality of life is the pits. So if you don’t let it get to you, you can enjoy life, even though [the IBS symptoms] were always there. You know it’s there, but you can’t let it run your life (ID 16).”

Interconnected relationships between positive versus negative psychological experiences, IBS symptoms, health behaviors, and HRQoL

Many participants also noted opposing interconnected relationships between positive versus negative psychological experiences and their IBS symptoms, HRQoL, and health behavior engagement: “I think emotions have a lot to do with it [quality of life]. If you’re feeling really good, I think you can really do a good job at work, whereas if you’re not feeling that good, you’re not going to be as productive or— if I’ve had like a bad day with my stomach and…I work from home. But I know if my stomach’s bothering me…if you have this knot in your stomach, it’s hard to talk to people or do a good job when you’re in pain. So that’s foremost. You’re trying to talk to somebody, but you may have a headache because sometimes that goes along with it because you’re worried about your stomach and that type of thing. So absolutely, it does affect your productivity and how you’re just going to relate to people. You’re not going to be as bubbly or you might be more quiet (ID 10).” Last, another participant shared: “I certainly see a very direct correlation between [my emotions and my quality of life]. On the days when…I’m having GI symptoms and flare-ups…it heightens the more negative emotions and makes it really difficult to get things done or be motivated to do them. When I’m happy, it makes things a lot easier in terms of motivation and progress throughout the day (ID 5).”

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this qualitative examination of 23 patients with IBS, several key themes emerged regarding the relationships between psychological constructs and IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement, and HRQoL. Bidirectional relationships were described between experiencing greater positive psychological constructs (e.g., sense of calm, joy, connectedness) and fewer IBS symptoms, increased health behavior engagement, and improved HRQoL. Conversely, as expected, negative psychological constructs (e.g., anxiety, loss of control, stress) were described as amplifying IBS symptoms, reducing health behavior engagement, and worsening HRQoL. Interconnected relationships between each of these elements (e.g., participating in physical activity both improves IBS symptoms and leads to greater positive psychological constructs, collectively leading to better HRQoL) were also robustly described.

Our qualitative findings regarding the relationships between psychological constructs and IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement, and HRQoL extend the existing literature on IBS. These findings add the patient perspective to the well-established importance of negative psychological factors as a clinical target in IBS.14 Not only has it been shown that comorbid psychiatric symptoms and negative psychological constructs correlate with worse IBS symptom severity and HRQoL,3,8,9 but reductions in negative psychological constructs (negative illness-specific cognitions and avoidance behaviors) appear to mediate the effects of CBTs on IBS symptom severity.56,57 Additionally, our findings also reinforce what is known about positive psychological constructs in IBS: greater well-being in individuals with IBS has been associated with reduced IBS symptom severity and improved HRQoL.25,29 Furthermore, our findings also provide qualitative support to early research suggesting that increased physical activity in IBS has the potential to lead to reductions in IBS symptoms, fatigue, depression, and anxiety, and improved HRQoL.58,59

The interconnected relationships identified in our analyses between positive psychological constructs and health behavior engagement are worth highlighting. Notably, these relationships are consistent with the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions60 and upward spiral theory of lifestyle change.61 These theories postulate that positive emotions derived from physical activity increase adaptability,60 broaden coping resources,60 and motivate continued engagement in physical activity.61 In this study, we learned that many participants experience a chain of positive events after engaging in physical activity, including greater positive emotions, mitigated IBS symptoms, and improved HRQoL. Conversely, many participants described how experiencing negative emotions could sometimes land in their gut, setting off a cascade of reduced health behavior engagement and worse HRQoL.

Our findings, in combination with what is known in both healthy and other chronically medically ill populations, suggest that positive psychological factors merit greater attention as an additional potentially meaningful clinical target in IBS. In other populations, greater well-being has been prospectively linked to increased physical activity as well as improved health outcomes, including slowed disease progression and lower overall mortality, independent of sociodemographic and medical factors.62,63 And interventions to cultivate greater well-being in chronically medically ill populations have demonstrated promise in their ability to boost positive psychological constructs and increase physical activity.32,33 The role of positive psychological interventions in IBS represents an area of much-needed future investigation.

Potential limitations to this qualitative study should be noted. First, the study population was recruited from a single, urban, tertiary care academic medical center and predominantly identified as White (83%), which may limit generalizability. Second, it is possible that the interview guide prompts may have increased the likelihood of finding connections between the elements examined.64 To mitigate this, the interview guide, coding book, and analysis plan were carefully designed and reviewed by a multidisciplinary team with consultation from a qualitative research expert. Additionally, some of the results were unexpected, such as the relatively greater focus on relationships between physical activity (compared with diet) and psychological experiences, and the way in which dietary modifications can contribute to experiencing negative psychological constructs.

In summary, the findings of this qualitative study are novel in identifying robust, reciprocal, and interconnected relationships between psychological experiences, IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement, and HRQoL, respectively. Positive and negative psychological constructs appear to have largely opposing effects on IBS symptoms, health behavior engagement, and HRQoL. Thus, positive psychological constructs, like negative psychological constructs, may represent a clinically important target in IBS. Effective brain–gut behavior therapies targeting negative psychological factors in IBS already exist (e.g., CBTs), but interventions to cultivate greater positive psychological experiences in IBS have not yet been explored. Per the ORBIT model for behavioral treatment development, the next step would be to develop and then evaluate a positive psychological intervention for IBS in a proof-of-concept trial. The findings of this qualitative study suggest that the development and assessment of a positive psychological intervention for IBS is an important future area of investigation, with the potential to mitigate IBS symptoms, increase health behavior engagement, and improve HRQoL.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Individuals with IBS linked the experience of positive psychological constructs with mitigated IBS symptoms, increased health behavior participation, and improved health-related quality of life.

Individuals with IBS connected the experience of negative psychological constructs with exacerbated IBS symptoms, reduced health behavior participation, and worsened health-related quality of life.

An intervention to cultivate greater well-being and positive psychological experiences may be a novel way to mitigate IBS symptoms, boost health behavior participation, and improve health-related quality of life in IBS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Lara Traeger and the MGH Qualitative and Mixed Methods Research Unit for their consultation.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Time for analysis and article preparation was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, K23DK120945 (KS), K23DK131334 (HBM), R01DK121003 (BK), and U01DK112193 (BK), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, R01HL155301 (CMC) and R01HL133149 (JCH), and the Harvard Medical School Dupont Warren Research Fellowship (ENM). The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data or writing of the report.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing interests related to this research. KS has received research support from Ironwood and Urovant and has served as a consultant to Anji, Arena, Gelesis, GI Supply, Sanofi, and Shire/Takeda. HBM receives royalties from Oxford University Press for a book on rumination syndrome. CMC has received salary support for research from BioXcel Pharmaceuticals and honoraria for talks to Sunovion Pharmaceuticals on topics unrelated to this research. BK has received research support from Medtronic, Gelesis, Takeda, Vanda, and consulting/speaking arrangements with Arena, CinDom, Cin Rx, Medtronic, Entrega, Ironwood, Neurogastrix, Phathom, Serepta, Sigma Wasserman, and Takeda. LK receives consulting fees from Lilly, Takeda, Pfizer, Abbvie, Reckitt Health and Trellus Health and is a co-founder/equity owner for Trellus Health. There are no other funding sources to declare.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:151–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Person H, Keefer L. Psychological comorbidity in gastrointestinal diseases: update on the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchard EB, Scharff L. Psychosocial aspects of assessment and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in adults and recurrent abdominal pain in children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cash B, Sullivan S, Barghout V. Total costs of IBS: employer and managed care perspective. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S7–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diagnosis Camilleri M. and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a review. JAMA. 2021;325:865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zia JK, Lenhart A, Yang PL, et al. Risk factors for abdominal pain disorders of gut-brain interaction in adults and children: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:995–1023.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibelli A, Chalder T, Everitt H, Workman P, Windgassen S, Moss-Morris R. A systematic review with meta-analysis of the role of anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome onset. Psychol Med. 2016;46:3065–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eijsbouts C, Zheng T, Kennedy NA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 53,400 people with irritable bowel syndrome highlights shared genetic pathways with mood and anxiety disorders. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1543–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu JC. Psychological co-morbidity in functional gastrointestinal disorders: epidemiology. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsenbruch S, Rosenberger C, Enck P, Forsting M, Schedlowski M, Gizewski ER. Affective disturbances modulate the neural processing of visceral pain stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome: an fMRI study. Gut. 2010;59:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keefer L, Ballou SK, Drossman DA, Ringstrom G, Elsenbruch S, Ljotsson B. A Rome working team report on brain-gut behavior therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:300–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubzansky LD, Huffman JC, Boehm JK, et al. Positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular disease: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1382–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farhadi A, Banton D, Keefer L. Connecting our gut feeling and how our gut feels: the role of well-being attributes in irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahdadi H, Balouchi A, Shaykh A. Comparison of resilience and psychological wellbeing in women with irritable bowel syndrome and normal women. Mater Sociomed. 2017;29:105–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quek SXZ, Loo EXL, Demutska A, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:2187–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SH, Naliboff BD, Shih W, et al. Resilience is decreased in irritable bowel syndrome and associated with symptoms and cortisol response. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30:e13155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker CH, Naliboff BD, Shih W, et al. The role of resilience in irritable bowel syndrome, other chronic gastrointestinal conditions, and the general population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(12):2541–2550.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dabek-Drobny A, Mach T, Zwolinska-Wcislo M. Effect of selected personality traits and stress on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Folia Med Cracov. 2020;60:29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voci SC, Cramer KM. Gender-related traits, quality of life, and psychological adjustment among women with irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endo Y, Shoji T, Fukudo S, et al. The features of adolescent irritable bowel syndrome in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 3):106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selvi KBO. Group comparison of individuals with and without irritable bowel syndrome in terms of psychological and lifestyle-related factors. Dusunen Adam: J Psychiatry Neuro Sci. 2022;1:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sibelli A, Chalder T, Everitt H, Chilcot J, Moss-Morris R. Positive and negative affect mediate the bidirectional relationship between emotional processing and symptom severity and impact in irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2018;105:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Ezra M, Hamama-Raz Y, Palgi S, Palgi Y. Cognitive appraisal and psychological distress among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2015;52:54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torkzadeh F, Danesh M, Mirbagher L, Daghaghzadeh H, Emami MH. Relations between coping skills, symptom severity, psychological symptoms, and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taft TH, Keefer L, Artz C, Bratten J, Jones MP. Perceptions of illness stigma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1391–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melchior C, Colomier E, Trindade IA, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: factors of importance for disease-specific quality of life. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022;10:754–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keefer L Behavioural medicine and gastrointestinal disorders: the promise of positive psychology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keefer L, Bedell A, Norton C, Hart AL. How should pain, fatigue, and emotional wellness be incorporated into treatment goals for optimal management of inflammatory bowel disease? Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1439–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huffman JC, Golden J, Massey CN, et al. A positive psychology-motivational interviewing intervention to promote positive affect and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: the BEHOLD-8 controlled clinical trial. Psychosom Med. 2020;82:641–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Hoffman Z, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect induction to promote physical activity after percutaneous coronary intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, et al. From ideas to efficacy: the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015;34:971–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1262–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinninti NR, Madison H, Musser E, Rissmiller D. MINI international neuropsychiatric schedule: clinical utility and patient acceptance. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18:361–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Labus JS, Bolus R, Chang L, et al. The visceral sensitivity index: development and validation of a gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cain KL, Conway TL, Adams MA, Husak LE, Sallis JF. Comparison of older and newer generations of ActiGraph accelerometers with the normal filter and the low frequency extension. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, DiCesare J, Puder KL. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan MJBS, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM. Initial validation of the nine item avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder screen (NIAS): a measure of three restrictive eating patterns. Appetite. 2018;123:32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amonoo HL, Brown LA, Scheu CF, et al. Positive psychological experiences in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. 2019;28:1633–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feig EH, Harnedy LE, Golden J, Thorndike AN, Huffman JC, Psaros C. A qualitative examination of emotional experiences during physical activity post-metabolic/bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2022;32:660–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Celano CM, Beale EE, Freedman ME, et al. Positive psychological constructs and health behavior adherence in heart failure: a qualitative research study. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22:620–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Millstein RA, Huffman JC, Thorndike AN, et al. How do positive psychological constructs affect physical activity engagement among individuals at high risk for chronic health conditions? A qualitative study. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17:977–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23:42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glaesmer H, Rief W, Martin A, et al. Psychometric properties and population-based norms of the life orientation test revised (LOT-R). Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:432–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schou-Bredal I, Heir T, Skogstad L, et al. Population-based norms of the life orientation test-revised (LOT-R). Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2017;17:216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crawford JR, Henry JD. The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43:245–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chilcot J, Moss-Morris R. Changes in illness-related cognitions rather than distress mediate improvements in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms and disability following a brief cognitive behavioural therapy intervention. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ljotsson B What are the mechanisms of psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome? J Psychosom Res. 2019;118:9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johannesson E, Ringstrom G, Abrahamsson H, Sadik R. Intervention to increase physical activity in irritable bowel syndrome shows long-term positive effects. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:600–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johannesson E, Jakobsson Ung E, Sadik R, Ringstrom G. Experiences of the effects of physical activity in persons with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a qualitative content analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1194–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fredrickson BL. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1367–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Cappellen P, Rice EL, Catalino LI, Fredrickson BL. Positive affective processes underlie positive health behaviour change. Psychol Health. 2018;33:77–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DuBois CM, Lopez OV, Beale EE, Healy BC, Boehm JK, Huffman JC. Relationships between positive psychological constructs and health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2015;195:265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levine GN, Cohen BE, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. Psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e763–e783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meyrick J What is good qualitative research? A first step towards a comprehensive approach to judging rigour/quality. J Health Psychol. 2006;11:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.