Highlights

-

•

Grass carp tl1a is induced after infection with Aeromonas hydrophila.

-

•

CiTL1A regulates inflammation.

-

•

CiTL1A interacts with DR3.

-

•

CiTL1A induces apoptosis via DR3.

Keywords: TL1A, Death receptor 3, Inflammation, Apoptosis, Grass carp

Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor like ligand 1A (TL1A), a member of TNF superfamily, regulates inflammatory response and immune defense. TL1A homologues have recently been discovered in fish, but their functions have not been studied. In this study, a TL1A homologue was identified in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) and its bioactivities were investigated. The grass carp tl1a (Citl1a) gene was constitutively expressed in tissues, with the highest expression detected in the liver. It was upregulated in response to infection with Aeromonas hydrophila. The recombinant CiTL1A was produced in bacteria and was shown to stimulate the expression of il1β, tnfα, caspase 8 and ifnγ in the primary head kidney leucocytes. In addition, co-immunoprecipitation assay revealed that CiTL1A interacted with DR3 and induced apoptosis via activation of DR3. The results demonstrate that TL1A regulates inflammation and apoptosis and is involved in the immune defense against bacterial infection in fish.

1. Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor superfamily (TNFSF) is an important group of cytokines that play key roles in regulating immunity, metabolism and morphological development. The TNFSF is composed of 19 ligands which bind to 29 receptors [1]. TNFSF members are typical type II membrane proteins and contain a characteristic "TNF homologous domain (THD)", which is located in the C-terminus [2]. Many TNFSFs are proteolytically cleaved to generate soluble forms via ectodomain shedding by metalloproteinases such as TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE) [3,4]. Soluble monomers form stable trimers which are capable of transmitting signals by binding to their cognate receptors [5].

TNF-like ligand 1A (TL1A), also known as TNF superfamily member 15 (TNFSF15) and vascular endothelial growth inhibitor (VEGI), was first reported in mammals in 1997 [6]. Like other members of TNFSF, TL1A is a type II transmembrane protein with a THD at the C-terminal region. TL1A undergoes TACE-mediated shedding from the cell surface to generate a soluble form able to bind to its receptors [7]. TL1A is produced mainly by vascular endothelial cells and a variety of other cell types including antigen-presenting cells, monocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, dendritic cells and T cells [4,[8], [9], [10]]. Its expression can be upregulated by TNFα, IL1α and PMA [11]. Death receptor 3 (DR3) and decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) are known receptors of TL1A. DR3, also known as TNF receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) 25, APO-3, TRAMP, LARD, and WSL-1, is a death domain (DD) containing TNFRSF member and is upregulated in the activated T cells [4,12]. TL1A exerts pleiotropic effects on cell proliferation, differentiation and activation of immune cells, including helper T cells and regulatory T cells [4,[13], [14], [15]]. TL1A induces NF-κB activation and also apoptosis in the DR3-expressing cells while DcR3 antagonizes such functions [11,16]. TL1A-DR3 interaction triggers the formation of signaling complexes containing TRADD, TRAF2, and RIP, activating the NF-κB and MAPK pathways to mediate inflammation and apoptosis [4,17].

The network of TL1A-DR3 axis regulating biological processes is complex. TL1A and DR3 have been extensively studied in mammals, but little is known about TL1A and its receptors in fish. The TL1A homologue was reported in zebrafish (Danio rerio) [18] and rock bream (Oplegnathus fasciatus) [19]. TL1A was modulated in response to infection and vaccination of rock bream iridovirus (RBIV) [19]. However, the functions of fish TL1A have not been investigated. In this study, a tl1a homologue was sequenced in grass carp and the expression investigated after infection with Aeromonas hydrophila (A. hydrophila). The recombinant TL1A protein was produced and its biological activities were determined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fish and challenge experiment

Grass carp (15 ± 2 g) were kept in the Binhai Base of Shanghai Ocean University. Fish were disinfected with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min, transferred to the indoor aquarium and maintained at 25 ± 2 °C for at least 2 weeks before experiments. They were fed daily and fasted for 24 h prior to the challenge experiment. Fish experiments were performed under local guidelines for the use of animals for research and approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ocean University (SHOU-DW-2021–027).

To examine C. idella tl1a (Citl1a) expression profiles in tissues, brain, skin, gills, gut, thymus, spleen, head kidney, trunk kidney and liver were sampled and homogenized using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed as described by Zhang et al. [20]. In addition, the expression of Citl1a in the hindgut, gills and head kidney of grass carp upon A. hydrophila stimulation was analyzed. A. hydrophila was provided by the National Pathogen Collection Center for Aquatic Animals, Shanghai Ocean University, and the challenge experiment was conducted as previously described [21]. In brief, a single colony of A. hydrophila was inoculated in the LB medium and cultured with constant shaking (at 170 rpm) overnight at 28 °C. The bacterial suspension was resuspended in PBS and adjusted to 1 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. Thirty-two fish were randomly placed in two tanks, each containing 16 fish, and intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 15 μl of 1 × 107 CFU/ml of A. hydrophila or an equal volume of PBS. Head kidney, gills and hindgut were collected from 4 fish from each group at 24, 48 and 72 h after infection and homogenized in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent for RNA extraction.

2. .2 cDNA cloning of the CiTL1A gene

Total RNA was extracted from head kidney of grass carp using the TRIzol reagent. First-strand cDNA was synthesised from total RNA using the PrimeScript™Ⅱ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Partial cDNA sequence of Citl1a was obtained from the whole-genome sequence database of grass carp (http://www.ncgr.ac.cn/grasscarp/) [22]. The full-length sequence of Citl1a was amplified using 5′ and 3′ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) PCR according to the instructions (Life Technology, USA) using the gene specific primers listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.3. Bioinformatics analysis

The nucleic acid and protein sequences were downloaded from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the ClustalW program (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). Protein domains were predicted using the SMART program (http://smart.emblheidelberg.de). The N-glycosylation sites and molecular weight were predicted using the softwares listed on the ExPASy server (https://www.expasy.org/). Genomic structures and gene synteny of zebrafish and human tl1a were obtained from the Ensembl database (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the Neighbor-Joining method using the MEGA X program and bootstrapped by repeating 10,000 times [23].

2.4. Production and purification of recombinant CiTL1A in bacteria

The putative mature CiTL1A peptide (Lys69-Thr240) was amplified with primers pET-F and pET-R (Supplementary Table 1) which contained two restriction enzyme sites BamH I and Hind III for cloning. The PCR products were digested with BamH I and Hind III and inserted into the pEHISTEVb plasmid to obtain pEHISTEVb-CiTL1A which was verified by sequencing. pEHISTEVb-CiTL1A was transformed into the E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells for production and purification of recombinant CiTL1A (rCiTL1A) using the method previously published [24]. The rCiTL1A was further verified using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against a synthetic CiTL1A peptide. Peptide synthesis (KHAREPDHPGYFDLDEDG) and antibody production and purification were undertaken by Cusabio (China).

2.5. Expression analysis of primary head kidney leucocytes after stimulation with rCiTL1A

Primary head kidney leucocytes (HKLs) were prepared as previously described [25] and seeded in 6-well plates (5 × 106 cells/well). The cells were cultured at 28 °C, 5% CO2 for 12 h and incubated with 1 and 10 ng/ml of rCiTL1A (rCiTL1A) for 24 h. Control cells were incubated with protein buffer. The adherent cells together with cells in suspension were harvested for total RNA extraction and gene expression analysis. Primers are given in Supplementary Table 1.

2.6. Interaction between CiTL1A and CiDR3

pcDNA3.1-CiTL1A-HA and pcDNA3.1-CiDR3-FLAG were synthesized by Genewiz Biotech (China) to examine the interaction between CiTL1A and CiDR3. The HEK293T cells were cultured in 25 cm2 flasks at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator with DMEM (Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA). When the cells reached 80% confluence, the cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-CiTL1A-HA plus pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-CiDR3-FLAG using the jetOPTIMUS reagent (PolyPlus, France). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and lysed in 500 μl RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma, USA). The cell lysates were placed on a rocker platform at 4 °C for 30 min and centrifuged (12,000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C) to remove cell debris. The lysate supernatants were incubated with 40 μl conjugated mouse anti-FLAG mAb agarose beads at 4 °C overnight. The agarose beads were collected at 2000 × g for 3 min, washed 4 times with ice-cold PBS buffer. The immunoprecipitated proteins and whole-cell lysates were mixed with 5 × SDS loading buffer and boiled for 10 min before SDS-PAGE.

For Western blotting, the immunoprecipitates and whole-cell lysates were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with TBS buffer containing 5% skimmed milk and 0.1% tween 20 at room temperature for 1 h, and incubated with the indicated primary and secondary antibodies (diluted in blocking buffer) at 4 °C overnight. After washing three times with TBST buffer (TBS buffer containing 0.1% tween 20), the membranes were photographed using an Odyssey CLx Imaging System (LI-COR, USA).

2.7. Effect of CiTL1A on apoptosis

HEK293T cells were cultured in 12-well plates and transfected with pcDNA3.1-CiTL1A-HA plus pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-CiDR3-FLAG. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were collected and analyzed using an Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Solarbio, China). Briefly, the cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min, washed twice with ice-cooled PBS, and resuspended in protein binding buffer (50 mM HEPES, 700 mM NaCl, 12.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). The cells were then stained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed by flow cytometry on a cytometer C6 PLUS (BD, USA). In addition, the cells were examined under a microscope Axio Observer (Zeiss, Germany).

2.8. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was run in triplicate on the Light Cycler® 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, Switzerland). The qRT-PCRs were set up as follows: 5 μl Hieff UNICON® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen, China), 1 μl cDNA template, 0.2 μl forward primer (10 μM), 0.2 μl reverse primer (10 μM) and 3.6 μl double distilled water, and were performed by the following conditions: 1 cycle of 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 62 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 10 s, followed by 1 cycle of 95 °C for 10 s, 65 °C for 60 s, 97 °C for 1 s. Primers are described in Supplementary Table 1. Elongation factor 1α (ef1α) was used as an internal reference housekeeping gene to normalize gene expression. Relative expression levels were calculated by comparing the expression levels of target genes against that of the housekeeping gene. Fold changes of expression were calculated by comparing the average levels of normalized gene expression of the experimental groups with those of the corresponding control groups.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The qRT-PCR data were analyzed using the SPSS package 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way ANOVA and the LSD post hoc test were used to analyze the expression data of challenge experiments, with “P < 0.05″ or “P < 0.01″ considered significant.

3. Result

3.1. Cloning and sequence analysis of CiTL1A

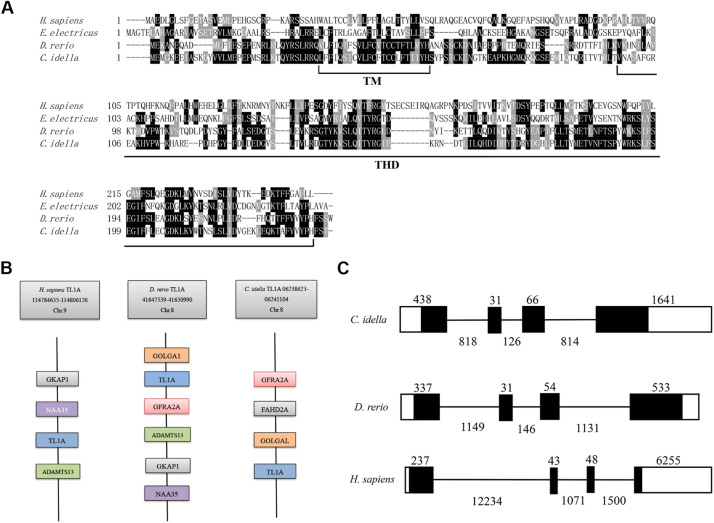

The full length of cDNA encoding Citl1a is 1095 bp in length, including a 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of 37 bp, an open reading frame (ORF) of 723 bp and a 3′-UTR of 335 bp, which has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession number: MN264645.1). The translated protein consists of 240 amino acids with a theoretical molecular mass of 27.9 kDa and an isoelectric point of 6.79. The CiTL1A protein has a predicted transmembrane region (TM, Leu36-His58) and a THD (Val98-His237) (Supplementary Fig. 1). An N-terminal cleavage site (between Ala72 and Pro73) is predicted to generate soluble CiTL1A (Supplementary Fig. 1). Multiple sequence alignment reveals that the transmembrane region and THD of TL1A are well conserved in fish and humans (Fig. 1A). CiTL1A shares low amino acid identities (18.2%−23.7%) with homologues from human, chicken (Gallus gallus), mouse (Mus musculus), electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Supplementary Table 2). Comparatively, CiTL1A has high sequence identity (53.3%) with zebrafish TL1A.

Fig. 1.

Bioinformatics analysis of CiTL1A. (A) Multiple alignment of protein sequences. The conserved amino acid residues are shaded. The TM and THD are indicated below the alignment. (B) Gene synteny of tl1a genes. The genomic data of human and zebrafish tl1a genes were retrieved from the Ensembl database. The Citl1a data were obtained from the grass carp genome database and annotated manually. (C) Genomic structure of tl1a genes. Blank and solid boxes indicate the untranslated regions and coding exons, respectively. Lines represent introns. The size (bp) of exons and introns is shown. Note that the size of exons and introns is disproportionate.

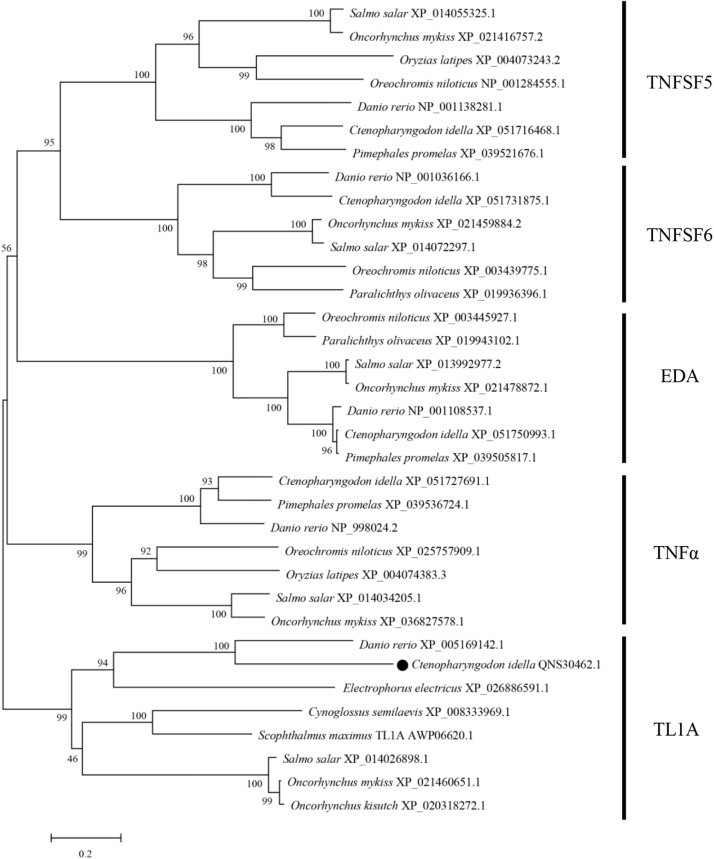

Gene synteny analysis showed that genes of the tl1a locus are conserved between zebrafish and humans (Fig. 1B). In humans, the tl1a gene is located in chromosome 9 and clustered with adamts13, naa35 and gkap1. In zebrafish chromosome 8, a conserved locus could be identified, where tl1a, adamts13, naa35 and gkap1 are present. In addition to the conserved synteny, the genomic structure of tl1a was obtained by comparing the genomic and cDNA sequences, revealing that the tl1a genes from zebrafish, human and grass carp consist of four exons and three introns. Moreover, exons 2 and 3 of tl1a are comparable in size (Fig. 1C). Phylogenetic tree was constructed to further explore the evolutionary relationship of CiTL1A. As shown in Fig. 2, members of teleost TNFSF are clustered into separate branches. Of note, the TL1A proteins including CiTL1A form a branch with a bootstrap value of 99%.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of TL1A proteins. The tree was constructed using the MEGA X program using the Neighbor-Joining method. Numbers at tree nodes represent the percentages of bootstrap values from 10,000 replicates. CiTL1A was indicated by “●”. EDA, ectodysplasin-a; TNFSF, TNF superfamily; TL1A, TNF-like ligand 1A.

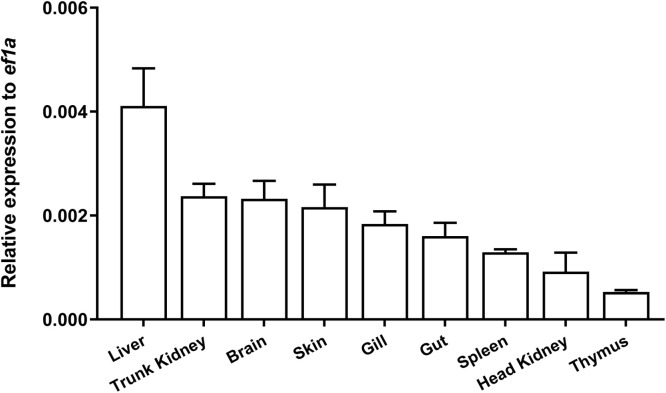

3.2. In vivo expression analysis of CiTL1A

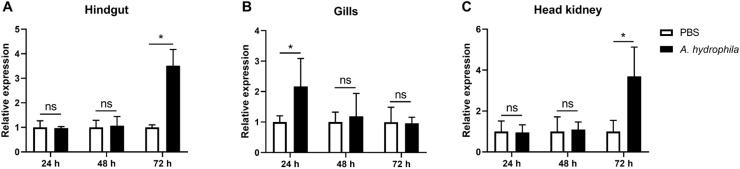

The expression of Citl1a was examined in the brain, skin, gills, gut, thymus, spleen, head kidney, trunk kidney and liver. As shown in Fig. 3, the Citl1a gene was constitutively expressed in all tissues. Liver showed the highest expression, followed by trunk kidney and brain. In contrast, the expression levels of Citl1a in the thymus, head kidney and spleen were relatively low (Fig. 3). A. hydrophila is a major bacterial pathogen affecting freshwater fish farming and was used to challenge fish by i.p. injection. Infection with A. hydrophila resulted in upregulation of Citl1a in the gills at 24 h but not at 48 and 72 h. However, the expression of Citl1a was upregulated approximately 3- fold in the hindgut and head kidney at 72 h, however not at 24 and 48 h (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Expression of Citl1a in tissues. The expression levels of Citl1a were determined by qRT-PCR and were normalized to that of ef1α. Data are presented as mean + SEM (N = 4).

Fig. 4.

The expression of Citl1a after infection with A. hydrophila. Grass carp were i.p. injected with 15 μl of A. hydrophila (1 × 107 CFU/ml) or an equal volume of PBS (control). Hindgut (A), gills (B) and head kidney (C) were sampled at 24, 48 and 72 h for gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR. The expression levels of tl1a were normalized to that of ef1α and the relative expression levels were calculated by comparing the average expression levels of the infected group with that of control (defined as 1). Data are shown as mean + SEM (N = 4). Significant difference is indicated by * (P < 0.05). ns = no significant difference.

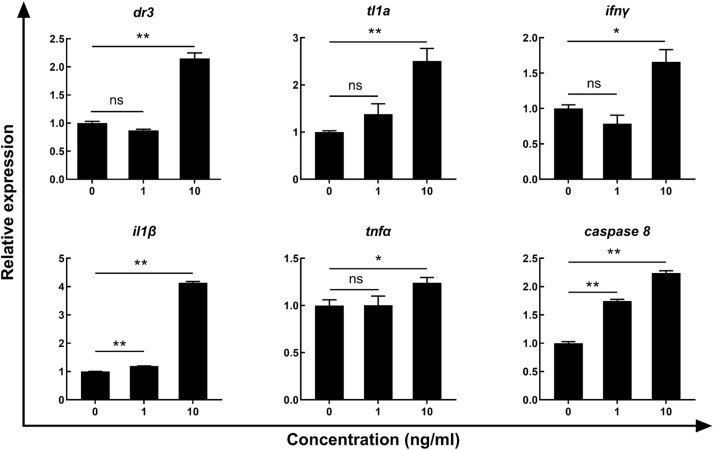

3.3. Analysis of gene expression in the primary head kidney leucocytes after stimulation with rCiTL1A

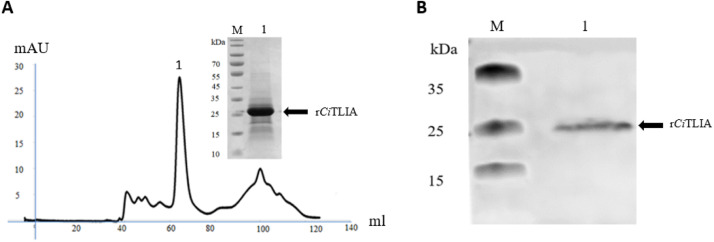

To evaluate the biological activity of CiTL1A, the rCiTL1A was produced in bacteria and purified using size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 5A) and verified using the CiTL1A polyclonal antibody by Western blotting (Fig. 5B). SDS-PAGE analysis revealed a single protein band of approx. 24 kDa, matching the expected size of the HISTEV-CiTL1A fusion protein (mature CiTL1A peptide of 20 kDa plus the HISTEV-tag of 4 kDa). The rCiTL1A was then used to stimulate the primary HKLs and the expression of immune genes were evaluated by qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 6, the expression levels of the tl1a, dr3, tnfα and ifnγ elevated after treatment of 10 ng/ml rCiTL1A. Similarly, the expression of il1β and caspase 8 increased significantly relative to the control cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Purification and verification of rCiTL1A expressed in bacteria. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified rCiTL1A protein and the curve of protein purification by size chromatography. (B) Western blotting analysis of rCiTL1A with anti-CiTL1A polyclonal antibody. M, marker; lane 1: elution fraction 1.

Fig. 6.

The effects of rCiTL1A on the expression of immune genes in the primary head kidney leucocytes. The primary HKLs were stimulated with 1 or 10 ng/ml of rCiTL1A for 24 h and analyzed by qRT-PCR. The control cells were incubated with protein buffer. The expression levels of target genes were normalized to that of ef1α and the relative expression levels were calculated by comparing the average expression levels of the treated cells with that of control cells. Data are shown as mean + SEM (N = 4). Significant differences are indicated by * (P < 0.05) and ** (P < 0.01). ns = no significant difference.

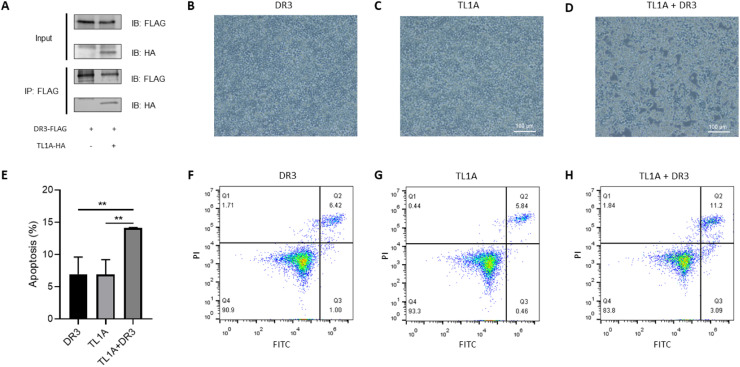

3.4. CiTL1A induces apoptosis via DR3

DR3 is a known receptor of TL1A in mammals [11]. In our previous study, we identified a CiDR3 homologue in grass carp [26]. To explore whether CiTL1A binds to CiDR3, the HEK293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-CiTL1A-HA and pcDNA3.1-CiDR3-FLAG plasmids for 24 h and harvested for co-immunoprecipitation assay. The results showed that CiTL1A could be co-immunoprecipitated with CiDR3, indicating that CiTL1A bound to CiDR3 (Fig. 7A). Next, we assessed whether CiTL1A induces apoptosis via DR3. We showed that the HEK293T cells overexpressing CiTL1A and CiDR3 displayed more apparent retardation of growth than those expressing CiTL1A or CiDR3 alone (Fig. 7B-D). Further, the apoptotic effect of CiTL1A was analyzed by flow cytometry using Annexin V-FITC and PI (Fig. 7F-H). The percentages of early (11.2%) and late (3.09%) apoptotic cells were significantly higher in the HEK293T cells transfected with Citl1a and Cidr3 than the cells transfected with Cidr3 or Citl1a (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

CiTL1A induces apoptosis via CiDR3. (A) The HEK293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-CiDR3-FLAG/pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-CiTL1A-HA/pcDNA3.1-CiDR3-FLAG plasmids for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with agarose conjugated-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. (B-D, F-H) The HEK293T cells were transfected with tl1a or/and dr3 expression plasmids for 24 h. (B-D) Morphology of HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids for 24 h. (F-H) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic cells transfected with indicated plasmids for 24 h. The cells were stained by Annexin V-FITC and PI and analysed by flow cytometry. (E) Statistical analysis of apoptotic cells in F-H. Apoptotic cells were defined as early (Q3) plus late (Q2) apoptotic cells. Data are shown as mean + SEM (N = 3). Significant difference is indicated by ** (P < 0.01).

4. Discussion

In this study, a homologue of TL1A (termed CiTL1A) was identified in grass carp. Our data show that synteny of the tl1a genes is conserved during evolution and the genomic organization of 4 exons and 3 introns remains unchanged. Despite low sequence identities with human TL1A, CiTL1A contains a transmembrane region and a THD, which are well conserved in vertebrate TL1A proteins (Fig. 1A). TL1A is mainly expressed as a membrane-bound protein, but could be cleaved by matrix metalloproteinases such as a disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 (ADAM17) and released to form a 20 kDa soluble protein [4,7]. In humans, membrane bound TL1A induces the expression of inflammatory cytokines in T cells while soluble TL1A was shown to promote intestinal type 2 inflammation independently of T cells [27]. Besides, membrane bound TL1A can bind DR3 through cell-cell contact to enhance IFNγ secretion [28]. In contrast, soluble trimeric TL1A has pro- and anti-apoptotic activities via activation of DR3 [29]. It has been shown that THD is essential for the trimeric formation of soluble TL1A protein and binding of TL1A with DR3 to activate the downstream signaling pathways [5]. The presence of a THD in fish TL1As suggests that TL1A functions may be conserved between fish and mammals [30].

Our results showed that the Citl1a gene was widely expressed in tissues. High levels of expression were detected in the liver, trunk kidney and brain but relatively low expression levels in the immune tissues such as thymus, head kidney and spleen (Fig. 3). This observation is consistent with previous studies in rock bream where high tl1a expression was detected in the liver but low expression in the head kidney and spleen [19]. However, in humans, the expression of tl1a was rarely detectable in the brain and liver, but predominantly in the prostate, placenta and stomach [11]. A. hydrophila is an etiology that infects grass carp and other freshwater species and causes severe enteritis, leading to huge economic losses [31], [32], [33]. Grass carp infected with A. hydrophila exhibited strong inflammatory responses and induced the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as il1β, il8, and tnfα [32]. Similarly, we observed that the Citl1a gene was also upregulated by A. hydrophila, suggesting that it is involved in the immune response to bacterial infection (Fig. 4). Moreover, rCiTL1A was able to induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines (il1β, ifnγ and tnfα) in the primary HKLs (Fig. 6), in line with the findings in mammals where the expression of TL1A and DR3 in the lamina propria mononuclear cells had a significant impact on the severity of mucosal inflammation [34]. IFNγ is a Th1 cytokine and activates lymphocytes such as CD4 and CD8 T cells [35,36]. The upregulation of ifnγ by CiTL1A suggests that it may regulate T cell functions through induction of T cell associated cytokines in fish.

It has been well documented that TL1A binds to DR3 to facilitate the formation of FADD-containing and caspase-8-containing death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), which subsequently activates apoptosis in cells that express DR3 [37]. In this study, we demonstrated that CiTL1A and CiDR3 could be co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 7A). This indicates that CiTL1A physically interacts with CiDR3. We found that HEK293T cells expressing exogenous CiTL1A and CiDR3 showed more cells undergoing apoptosis than those expressing CiDR3 or CiTL1A alone, supporting that CiTL1A initiates cell apoptosis through activation of CiDR3. Consistently, CiTL1A upregulated the expression of caspase 8 (Fig. 6), which is known to be involved in apoptosis pathway [38].

In summary, a CiTL1A homologue was identified in grass carp. It was constitutively expressed in tissues and could be induced by A. hydrophila infection. Functional analysis showed that CiTL1A upregulated the expression of genes promoting inflammation and apoptosis and that it activated cell apoptosis via DR3. Our results suggest that the functions of TL1A may be conserved in fish.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers: 32030112 and U21A20268) and Key Laboratory of Marine Biotechnology of Fujian Province (Grant number: 2020MB01), China.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.fsirep.2023.100090.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Dostert C., Grusdat M., Letellier E., Brenner D. The TNF family of ligands and receptors: communication modules in the immune system and beyond. Physiol. Rev. 2019;99(1):115–160. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiens G.D., Glenney G.W. Origin and evolution of TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011;35(12):1324–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locksley R.M., Killeen N., Lenardo M.J. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104(4):487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiba Y., Nakamura M. The role of TL1A and DR3 in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/258164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodmer J.L., Schneider P., Tschopp J. The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan K.B., Harrop J., Reddy M., Young P., Terrett J., Emery J., Moore G., Truneh A. Characterization of a novel TNF-like ligand and recently described TNF ligand and TNF receptor superfamily genes and their constitutive and inducible expression in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells. Gene. 1997;204(1–2):35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muck C., Herndler-Brandstetter D., Micutkova L., Grubeck-Loebenstein B., Jansen-Durr P. Two functionally distinct isoforms of TL1A (TNFSF15) generated by differential ectodomain shedding. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2010;65(11):1165–1180. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bamias G., Martin C., 3rd, Marini M., Hoang S., Mishina M., Ross W.G., Sachedina M.A., Friel C.M., Mize J., Bickston S.J., Pizarro T.T., Wei P., Cominelli F. Expression, localization, and functional activity of TL1A, a novel Th1-polarizing cytokine in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Immunol. 2003;171(9):4868–4874. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bamias G., Mishina M., Nyce M., Ross W.G., Kollias G., Rivera-Nieves J., Pizarro T.T., Cominelli F. Role of TL1A and its receptor DR3 in two models of chronic murine ileitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103(22):8441–8446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510903103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassatella M.A., Pereira-da-Silva G., Tinazzi I., Facchetti F., Scapini P., Calzetti F., Tamassia N., Wei P., Nardelli B., Roschke V., Vecchi A., Mantovani A., Bambara L.M., Edwards S.W., Carletto A. Soluble TNF-like cytokine (TL1A) production by immune complexes stimulated monocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Immunol. 2007;178(11):7325–7333. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Migone T.S., Zhang J., Luo X., Zhuang L., Chen C., Hu B., Hong J.S., Perry J.W., Chen S.F., Zhou J.X., Cho Y.H., Ullrich S., Kanakaraj P., Carrell J., Boyd E., Olsen H.S., Hu G., Pukac L., Liu D., Ni J., Kim S., Gentz R., Feng P., Moore P.A., Ruben S.M., Wei P. TL1A is a TNF-like ligand for DR3 and TR6/DcR3 and functions as a T cell costimulator. Immunity. 2002;16(3):479–492. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward-Kavanagh L.K., Lin W.W., Sedy J.R., Ware C.F. The TNF receptor superfamily in co-stimulating and co-inhibitory responses. Immunity. 2016;44(5):1005–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber T.H., Wolf D., Tsai M.S., Chirinos J., Deyev V.V., Gonzalez L., Malek T.R., Levy R.B., Podack E.R. Therapeutic Treg expansion in mice by TNFRSF25 prevents allergic lung inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120(10):3629–3640. doi: 10.1172/JCI42933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taraban V.Y., Slebioda T.J., Willoughby J.E., Buchan S.L., James S., Sheth B., Smyth N.R., Thomas G.J., Wang E.C., Al-Shamkhani A. Sustained TL1A expression modulates effector and regulatory T-cell responses and drives intestinal goblet cell hyperplasia. Mucosal. Immunol. 2011;4(2):186–196. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meylan F., Richard A.C., Siegel R.M. TL1A and DR3, a TNF family ligand-receptor pair that promotes lymphocyte costimulation, mucosal hyperplasia, and autoimmune inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2011;244(1):188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsters S.A., Sheridan J.P., Donahue C.J., Pitti R.M., Gray C.L., Goddard A.D., Bauer K.D., Ashkenazi A. Apo-3, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family, contains a death domain and activates apoptosis and NF-κB. Curr. Biol. 1996;6(12):1669–1676. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70791-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pobezinskaya Y.L., Choksi S., Morgan M.J., Cao X., Liu Z.G. The adaptor protein TRADD is essential for TNF-like ligand 1A/death receptor 3 signaling. J. Immunol. 2011;186(9):5212–5216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glenney G.W., Wiens G.D. Early diversification of the TNF superfamily in teleosts: genomic characterization and expression analysis. J. Immunol. 2007;178(12):7955–7973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim J., Park T., Kim J., Hong S. Cloning and characterization of tumor necrosis factor superfamily 15 in rock bream, Oplegnathus fasciatus; phylogenetic, in silico, and expressional analysis. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2020.103685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C., Zhang Q., Wang J.Y., Tian J.Y., Song Y.J., Xie H.X., Chang M.X., Nie P., Gao Q., Zou J. Transcriptomic responses of S100 family to bacterial and viral infection in zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;94:685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng J., Jia Z., Yuan G., Zhu X., Liu Q., Wu K., Wang J., Zou J. Expression and functional characterization of three beta-defensins in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2022.104616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Lu Y., Zhang Y., Ning Z., Li Y., Zhao Q., Lu H., Huang R., Xia X., Feng Q., Liang X., Liu K., Zhang L., Lu T., Huang T., Fan D., Weng Q., Zhu C., Lu Y., Li W., Wen Z., Zhou C., Tian Q., Kang X., Shi M., Zhang W., Jang S., Du F., He S., Liao L., Li Y., Gui B., He H., Ning Z., Yang C., He L., Luo L., Yang R., Luo Q., Liu X., Li S., Huang W., Xiao L., Lin H., Han B., Zhu Z. The draft genome of the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) provides insights into its evolution and vegetarian adaptation. Nat. Genet. 2015;47(6):625–631. doi: 10.1038/ng.3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K., MEGA X. molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang X., Wang J., Wan S., Xue Y., Sun Z., Cheng X., Gao Q., Zou J. Distinct expression profiles and overlapping functions of IL-4/13A and IL-4/13B in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Aquacult. Fisheries. 2020;5(2):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.aaf.2019.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xue Y.J., Jiang X.Y., Gao J.D., Li X., Xu J.W., Wang J.Y., Gao Q., Zou J. Functional characterisation of interleukin 34 in grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;92:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng X., Jiang X., Song Y., Gao J., Xue Y., Hassan Z., Gao Q., Zou J. Identification and modulation of expression of a TNF receptor superfamily member 25 homologue in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Aquacult. Fisheries. 2020;5(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aaf.2019.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferdinand J.R., Richard A.C., Meylan F., Al-Shamkhani A., Siegel R.M. Cleavage of TL1A differentially regulates its effects on innate and adaptive immune cells. J. Immunol. 2018;200(4):1360–1369. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biener-Ramanujan E., Gonsky R., Ko B., Targan S.R. Functional signaling of membrane-bound TL1A induces IFN-γ expression. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(11):2376–2380. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bittner S., Knoll G., Fullsack S., Kurz M., Wajant H., Ehrenschwender M. Soluble TL1A is sufficient for activation of death receptor 3. FEBS J. 2016;283(2):323–336. doi: 10.1111/febs.13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Xiao T., Zou J. Fish TNF and TNF receptors. Sci. China Life Sci. 2021;64(2):196–220. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasmussen-Ivey C.R., Hossain M.J., Odom S.E., Terhune J.S., Hemstreet W.G., Shoemaker C.A., Zhang D., Xu D.H., Griffin M.J., Liu Y.J., Figueras M.J., Santos S.R., Newton J.C., Liles M.R. Classification of a hypervirulent Aeromonas hydrophila pathotype responsible for epidemic outbreaks in warm-water fishes. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1615. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song X.H., Zhao J., Bo Y.X., Liu Z.J., Wu K., Gong C.L. Aeromonas hydrophila induces intestinal inflammation in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella): an experimental model. Aquaculture. 2014;434:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi W.M., Mo W.Y., Wu S.C., Mak N.K., Bian Z.X., Nie X.P., Wong M.H. Effects of traditional Chinese medicines (TCM) on the immune response of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) Aquacult. Int. 2014;22(2):361–377. doi: 10.1007/s10499-013-9644-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prehn J.L., Mehdizadeh S., Landers C.J., Luo X., Cha S.C., Wei P., Targan S.R. Potential role for TL1A, the new TNF-family member and potent costimulator of IFN-γ, in mucosal inflammation. Clin. Immunol. 2004;112(1):66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasahara T., Hooks J.J., Dougherty S.F., Oppenheim J.J. Interleukin 2-mediated immune interferon (IFN-γ) production by human T cells and T cell subsets. J. Immunol. 1983;130(4):1784–1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsushita H., Hosoi A., Ueha S., Abe J., Fujieda N., Tomura M., Maekawa R., Matsushima K., Ohara O., Kakimi K. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes block tumor growth both by lytic activity and IFNγ-dependent cell-cycle arrest. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015;3(1):26–36. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi C., Wang X., Shen Z., Chen S., Yu H., Williams N., Wang G. Anti-mitotic chemotherapeutics promote apoptosis through TL1A-activated death receptor 3 in cancer cells. Cell Res. 2018;28(5):544–555. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu W., Vetreno R.P., Crews F.T. Hippocampal TNF-death receptors, caspase cell death cascades, and IL-8 in alcohol use disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2021;26(6):2254–2262. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0698-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.