Abstract

Leishmaniasis is one of the tropical diseases which affects over 12 million people mainly in the tropical regions of the world and is caused by the leishmanial parasites transmitted by the female sand fly. The lack of vaccines to prevent leishmaniasis, as well as limitations of existing therapies necessitated this study which was focused on a combined virtual docking screening and 3-D QSAR modeling approach to design some diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs, while also performing pharmacokinetic analysis and Molecular Dynamic (MD) simulation to ascertain their drug-ability. As a result, the built 3-D QSAR model was found to satisfy the requirement of a good model with R2 = 0.9777, SDEC = 0.0593, F-test = 105.028, and Q2LOO = 0.6592. The template (compound 9, MolDock score = − 161.064) and all seven newly designed analogs were found to possess higher docking scores than the reference drug (Pentamidine, Moldock score = − 137.827). The results of the pharmacokinetic analysis suggest 9 and the new molecules (9a, b, c, e, and f) as orally bioavailable with good ADME and safe toxicological profiles. These molecules also showed good binding interactions with the receptor (pyridoxal kinase). Additionally, the MD simulation result confirmed the stability of the tested protein–ligand complexes, with an estimated ∆G binding (MM/GBSA) of − 65.2177 kcal/mol and − 58.433 kcal/mol for 9_6K91 and 9a_6K91 respectively. Hence, the new compounds, especially 9a could be considered potential anti-leishmanial inhibitors.

Keywords: Leishmaniasis, Diarylidene cyclohexanone, 3-D QSAR, Molecular docking, ADMET, Molecular dynamics

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease that infects over 12 million people settling mainly in tropical Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America (Clementino et al. 2021). Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the deadliest of all leishmanial infections and always proves fatal if left untreated. VL is caused by the leishmanial (L) parasites majorly L. donovani and L. infantum which are transmitted by the female sand flies (Upadhyay et al. 2019). Major health conditions associated with leishmaniasis include weight loss, weakness, fever, and hepatosplenomegaly (Yousuf et al. 2015). Owing to the lack of a vaccine to prevent this infection, a major treatment approach has been the use of chemotherapy with drugs such as amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, and miltefosine among others (Ugbe et al. 2022a, b, c). However, these therapies are either not effective enough or are associated with adverse effects such as nausea, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, eye irritation, lethargy, and cardiotoxicity (Brito et al. 2019; Ugbe et al. 2022a, b, c). More so, resistance posed by target organisms to existing therapies is on the rise (Fan et al. 2018). Additionally, leishmaniasis is only taken less seriously compared to other infections such as cancer, diabetes, malaria, stroke, hepatitis, and AIDS (Ugbe et al. 2022a, b, c). Therefore, efforts geared toward the discovery and development of new medicines that overcome the limitations of existing therapies are necessary.

Computer-aided modeling approaches such as Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and pharmacokinetics properties prediction among others play a critical role in drug discovery and development owing to their advantages over the traditional methods such as time-saving, cost-effectiveness, and reliability (Adeniji et al. 2020; Ugbe et al. 2021). The pyridoxal kinase (PdxK) protein (PDB: 6K91) was reported previously to play a key role in the formation of pyridoxal -5’-phosphate, an active form of vitamin B6 by catalyzing the phosphorylation of the 5’-hydroxyl group of the pyridoxal (Are et al. 2020). PdxK is a key enzyme for the growth of parasites and is also useful in host infection (Kumar et al. 2018). Some well-known anti-malarial medicines have previously been reported to show inhibition against PdxK such as primaquine and chloroquine (Kumar et al. 2018). Hence, PdxK could serve as an interesting enzyme target for new leishmanial inhibitors.

Bis-(arylmethylidine)-cycloalkanones have been reported to show a wide range of activities such as anti-tumor, anti-tubercular, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidants (Din et al. 2018). The two aromatic moieties in bis-aryl-α, β unsaturated ketones have also been reported to be important for the potential binding of the ligands to a given target protein (Chandru et al. 2007). Therefore, this work was focused on a combined virtual molecular docking screening and 3-D QSAR modeling to design some substituted 2,6-diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs, while also performing pharmacokinetic analysis and molecular dynamic simulation to establish their drug-likeness status and stability of the resulting ligand–protein complexes respectively.

Materials and methods

Data sourcing

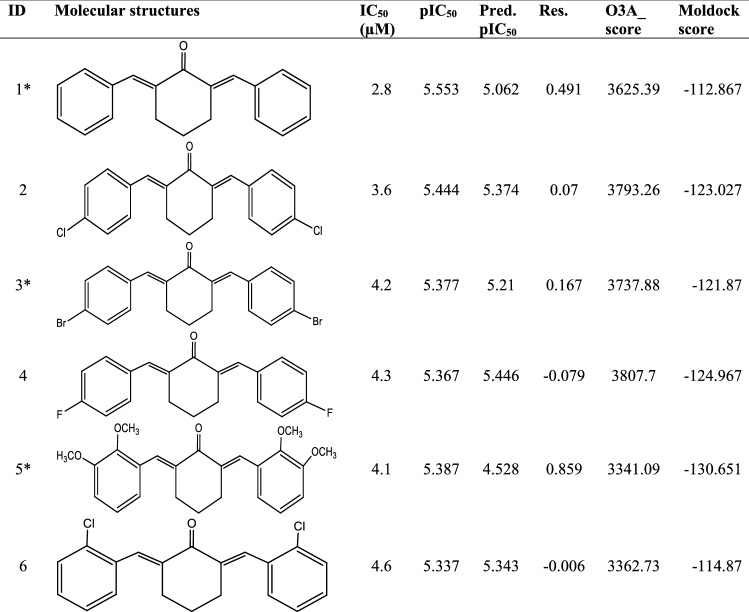

Din et al. 2018 reported the synthesis of a series of symmetrical and unsymmetrical substituted 2,6-diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs, as part of the anti-leishmanial drug discovery effort. Their biological activities were tested against promastigotes of L. amazonensis and reported in micromolar (µM). Consequently, a dataset of Twenty-five (25) compounds with relatively better half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were obtained from their report and used for this theoretical study. The molecular structures, bioactivities (IC50), and pIC50 obtained as a logarithmic function of IC50 for these compounds were reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecular structures, bioactivities, and protein–ligand binding scores of the various diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs, as well as the binding score of the reference drug pentamidine

*Testset compounds

Ref Reference drug (Pentamidine), O3A Open3DAlign, Res Residual

Hardware, software, and web services

The hardware used was an HP laptop computer with the following specifications: Processor (Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-4210U CPU @ 1.70 GHz 2.40 GHz), Installed RAM (8.00 GB), System type (64-bit operating system, × 64-based processor), Edition (Windows 10 Home Single Language), Version 21H2. Software used includes Chemdraw Ultra v. 12.0.2, Spartan’14 v. 1.1.4, and Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer v. 16.1.0.15350. Others include Open3Dtools, Maestro v. 12.3, Molegro Virtual Docker v. 6.0, a product of the A CLC Bio Company, NAMD v 2.14, and VMD v 1.9.3 OpenGL Display. The online web servers; http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm and admetSAR (ecust.edu.cn) were used for the pharmacokinetics properties prediction, while https://www.charmm-gui.org was used for generating ligand parameter files for MD simulation (Baell and Holloway 2010; Pires et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2016; Daina et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2018).

Structural optimization

The molecular structures of all the compounds in Table 1 were drawn using the ChemDraw Ultra, saved as MDL molfile format, and thereafter fed separately onto the Spartan’14 Graphical User Interface. Energy minimization was first performed on the imported molecules and then saved in Spartan file format. The resulting structures were then subjected to full-scale optimization first by using Molecular Mechanics Force Field (MMFF) and thereafter Density Functional Theory (DFT) with Becke’s three-parameter read-Yang-Parr hybrid (B3LYP) option and utilizing the 6-31G** basis set. The optimized structures were saved as SD and PDB file formats for subsequent use in 3-D QSAR modeling and molecular docking studies respectively (Wang et al. 2020; Ugbe et al. 2021).

Docking protocol

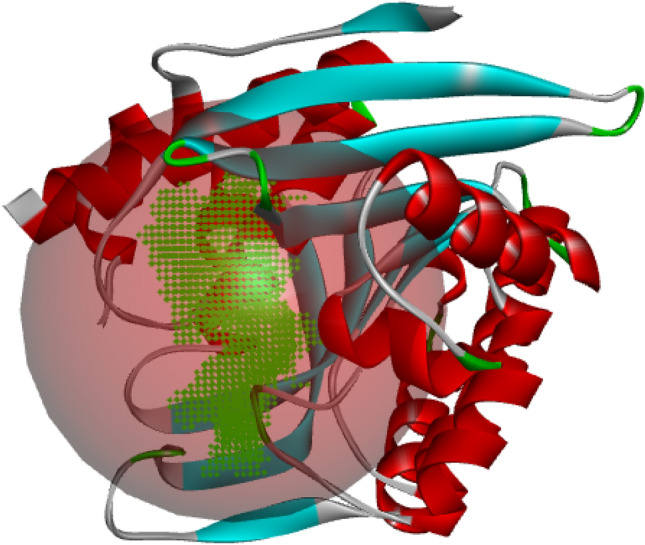

The crystal structure of the target protein, PdxK (PDB: 6K91) was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank in PDB file format and then prepared using the Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) by eliminating water molecules, cofactors, and co-crystallized ligand contained within the protein structure (Ugbe et al. 2022a, b, c). The protein comprises two similar chains (A and B) but B was utilized. The software allows for the repair (rebuild) of all affected residues. The receptor’s binding cavities were defined and that which has the largest volume and surface (volume: 399.872 and surface: 974.08) was adopted for the docking simulation. Figure 1 shows the 3D representation of PdxK with a sphere of the defined binding site. All ligands were imported in PDB file format and prepared appropriately. The simulation was performed using the parameter settings in Table 2. The binding scores were then recorded, while the predicted ligand–protein interaction profiles were visualized using the Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer. A similar method was earlier reported elsewhere (Ibrahim et al. 2020; Abdullahi et al. 2022).

Fig. 1.

3D representation of PdxK showing the binding site

Table 2.

Parameter settings utilized for the molecular docking simulation

| Setting | Selected option |

|---|---|

| Scoring function | |

| Score | MolDock score |

| Grid resolution | 0.30Å |

| Binding site | |

| Origin | Volume: 399.872; Surface: 974.08 |

| Center | X: 20.80, Y: -2.55, Z: 35.90 |

| Radius | 15 |

| Search algorithm | |

| Algorithm | MolDock SE |

| Number of runs | 10 |

| Constrain poses to cavity | YES |

| After docking: Energy minimization | YES |

| After docking: Optimize H-bonds | YES |

| Parameter setting | |

| Maximum iteration | 1500 |

| Maximum population size | 50 |

3-D QSAR modeling

Molecular structure alignment plays a critical role in 3D-QSAR modeling as it strongly determines the predictive accuracy and statistical quality of the built 3D-QSAR model (ElMchichi et al. 2020; Al-Attraqchi et al. 2022). The atom-based alignment method which attempts to match the atoms of the various structures to be aligned with those of the template structure, based on the atom’s properties was adopted using the Open3DAlign (O3A) tool (Zhang et al. 2020).

The aligned structures were utilized for building the 3-D QSAR model using the Open3DQSAR software (Zhang et al. 2020). The Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) which is concerned with steric and electrostatic fields’ contributions was studied (ElMchichi et al. 2020). A dataset of 25 compounds was divided into a training set and a test set of 18 and 7 molecules respectively, i.e. percentage ratio of 70:30. The steric and electrostatic Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs) analysis was carried out on the aligned compounds placed within a 3-D cubic lattice of grid size 1.5 Å and a 5.0 Å out gap (Tosco and Balle 2011). Variables pretreatment was carried out as follows; energy cut-off (30.0 kJ/mol), elimination of variables having constant or near-constant values, and standard deviation cut-off (level = 2.0) (Al-Attraqchi et al. 2022). The Un-informative Variable Elimination-Partial Least Square (UVE-PLS) was used to build the statistical model and for generating the steric and electrostatic contour plots (Edache et al. 2022). The resulting model was then cross-validated using the Leave-One-Out (LOO), Leave-Two-Out (LTO), and Leave-Many-Out (LMO), while the steric and electrostatic contour maps were visualized on Maestro v. 12.3.

Drug design

3-D QSAR is a sophisticated tool for designing new drug compounds because it tends to utilize the 3-D properties of the molecules to predict their activities (Verma et al. 2010). Here, Seven (7) compounds (9a– g) were designed using the template structure (Compound 9) mainly by the substitution of some substituent groups or chemical moieties following the information provided by the 3-D contour maps. The molecular structures of the newly designed compounds were prepared as earlier described (see ‘molecular geometry minimization’ section). Molecular docking simulation was then performed between the newly designed molecules and the target protein (PdxK), using MVD, while the resulting pharmacological interactions were visualized using the Biovia Discovery Studio.

Prediction of pharmacokinetic properties

Drug-likeness and ADMET properties prediction both constitute an absolutely necessary stage in drug discovery’s early phase because only molecules with good drug-likeness properties and excellent ADMET profiles advance into the pre-clinical research phase (Ugbe et al. 2021). Here, the pharmacokinetic properties of the template molecule (9) and the newly designed compounds (9a, b, c, d, e, f, and g) were predicted using two online web servers; http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm and admetSAR (ecust.edu.cn) for drug-likeness/ADME and toxicity profiling respectively. The choices of molecules for oral bioavailability have been guided by several rules such as Lipinski’s ‘rule of five’ (ROF), Veber rule, Ghose rule, Egan, and Muegge, etc. (Sun et al. 2020). The compounds would be assessed for oral bioavailability using the ROF, a widely used criterion for oral bioavailability (Lipinski et al. 2001).

Molecular dynamics simulation

MD simulations of the complexes of compound 9 (template) and compound 9a with PdxK were performed separately using the combined approach of Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics (CHARMM) force field, Nano-scale Molecular Dynamics (NAMD), and Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD). The CHARMM-GUI, an established web-based platform that utilizes the CHARMM force field, was used to generate the input files for the simulation by NAMD (Lee et al. 2016). The periodic boundary condition was utilized while fitting the system into a cubic water box for solvation. The protein was solvated and neutralized explicitly in an aqueous solution of 0.15 M concentration of potassium chloride salt (Edache et al. 2022). The simulation process involving energy minimization, equilibration (100 ps time frame), and production (500,000 steps or 1 ns time frame) was performed on the resulting system, while the results were visualized using VMD and the Biovia discovery studio (Muniba 2019). A similar procedure was described elsewhere (Ugbe et al. 2023). Additionally, MolAICal software was used to compute the ligand-binding affinity by Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) method based on the resulting MD log files obtained with NAMD (Bai et al. 2020). MM/GBSA is estimated using Eqs. (1) – (3).

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where, ∆EMM is the gas phase MM energy, − T∆S represents the conformational entropy, ∆EMM is the sum of ∆Eele, van der Waals energy ∆Evdw and ∆Einternal of bond, angle, and dihedral energies, ∆Gsol is the solvation free energy equal to the sum of the non-electrostatic solvation component ∆GSA and electrostatic solvation energy ∆GGB.

Results and discussion

Virtual docking screening

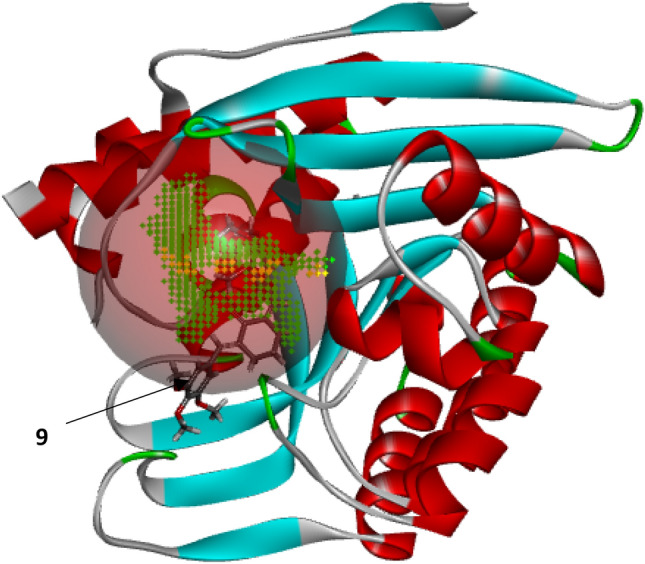

The results (Moldock scores) of the docking simulation conducted between PdxK and the various diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs, as well as the reference drug (Pentamidine), were reported in Table 1, while Fig. 2 shows the 3D representation of the template compound in the active site of the receptor.

Fig. 2.

3D representation of compound 9 in the active site of PdxK

The binding score which is a measure of the degree of affinity between a ligand and a receptor is most often used in the screening of a large library of compounds to find more active molecules that interact strongly with a receptor of interest. The binding affinities (Moldock scores) available in Table 1 range from − 112.03 to − 161.064, with only compounds 9 and 22 showing higher negative binding scores than the reference drug pentamidine (Moldock score = − 137.827). The higher binding scores associated with compounds 9 and 22 could be attributed to the relatively larger number of methoxy group substituents on both aromatics rings. Compound 1 with no substitution on the aromatic rings has a binding score of − 112.867, while compound 10 with a single methoxy group has − 121.342. The binding score tends to further increase as more of the methoxy groups are incorporated as seen in compound 17 (2 methoxy groups, moldock score = − 122.289), compound 24 (4 methoxy groups, moldock score = − 136.02), compound 22 (5 methoxy groups, moldock score = − 138.109), and compound 9 (6 methoxy groups, moldock score = − 161.064). Higher-degree alkoxy groups such as ethoxy, isopropoxy, and tert-butoxy were not tested. Also, substitutions with electron-withdrawing or electronegative substituents such as the fluoro, chloro, and Bromo groups contributed only a little to the binding affinity. Consequently, compound 9 with the highest Moldock score of − 161.064 was selected as the template molecule for designing more prominent inhibitors. Therefore, the virtual docking screening has proved effective as the most active analog was identified and extracted for further evaluation.

3-D QSAR modeling

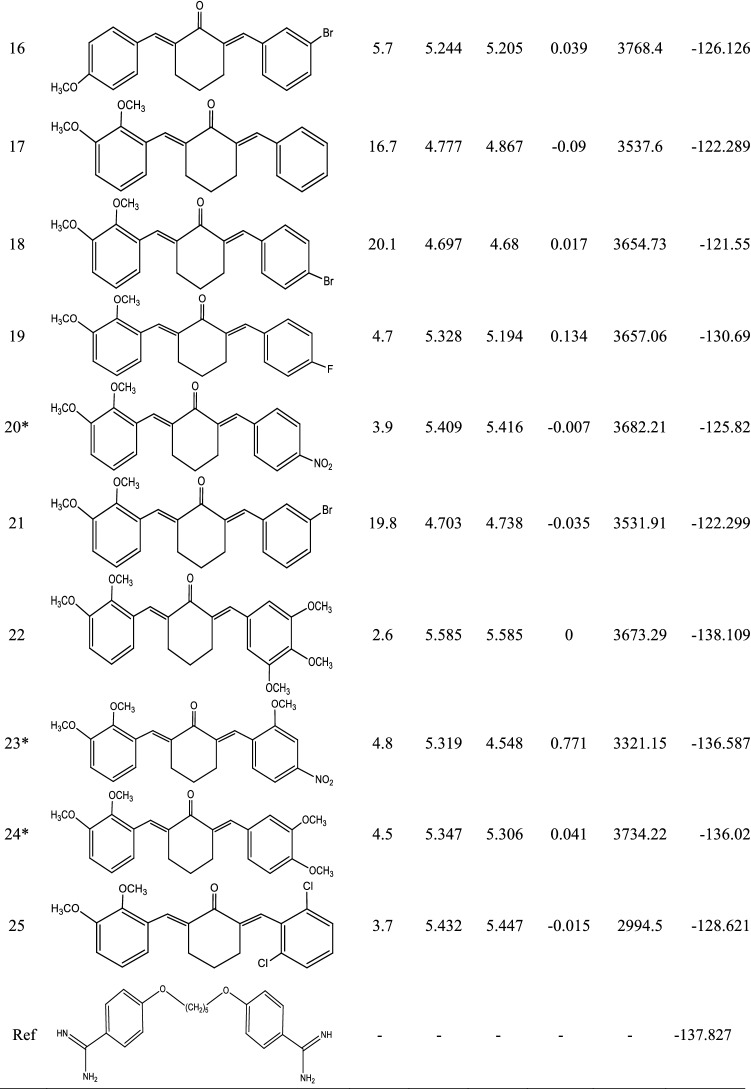

Molecular structural alignment represents a key factor in ascertaining the predictive strength of a built 3-D QSAR model. Figure 3(a-b) shows the molecular structure of the alignment template (compound 9) and the aligned structures as obtained from the super-imposition of the remaining 25 molecules on the template structure. The UVEPLS approach was used to develop the model. Some significant statistical parameters calculated for the model were presented in Table 3. Reported in Table 1 were the observed pIC50, predicted pIC50, and their residuals together with their O3A scores. Additionally, a plot showing the correlation between predicted and observed activities for both training and test sets was obtained and presented in Fig. 4. Also, the CoMFA model equation was summarized graphically as 3D contour maps as shown in Figs. 5 (a-b) and 6 (a-b).

Fig. 3.

Molecular alignment of structures for the QSAR modeling A Alignment template (compound 9 with the highest O3A_Score of 4002.51). B All structures aligned

Table 3.

Statistical parameters of the built model

| Parameters | (UVEPLS) |

|---|---|

| PC | 5 |

| R2 | 0.9777 |

| SDEC | 0.0593 |

| F-test | 105.028 |

| Q2LOO | 0.6592 |

| SDEPLOO | 0.2314 |

| Q2LTO | 0.6176 |

| SDEPLTO | 0.2451 |

| Q2LMO | 0.5206 |

| SDEPLMO | 0.2717 |

| Field contributions | |

| Steric | 0.6532 (65.32%) |

| Electrostatic | 0.3468 (34.68%) |

Fig. 4.

Correlation between predicted and observed pIC50 for training and test sets

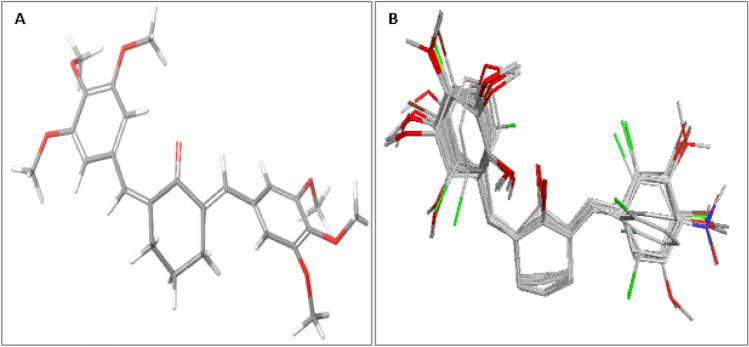

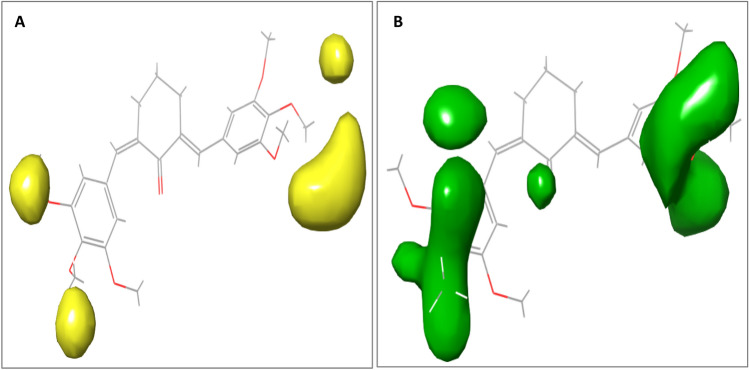

Fig. 5.

Steric field contour maps of compound 9 A Red contours showing regions of unfavorable steric bulk. B Blue contours represent regions of favorable steric bulk

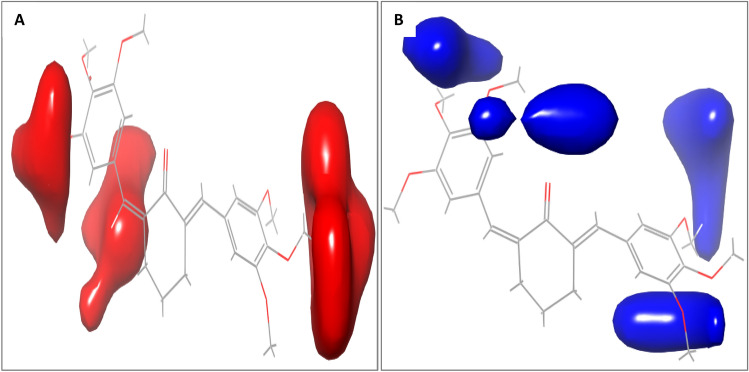

Fig. 6.

Electrostatic field contour maps of compound 9 A Yellow contours represent regions favored by high electron density or unfavorable to electron-withdrawing substituents. B Green contours showing regions of unfavorable high electron density or favorable to electron-withdrawing groups

The alignment process involves an early step that provided all the 25 compounds the opportunity of being chosen as the alignment template based on the compound displaying the highest Open3DAlign (O3A) score. The O3A scores of the various compounds were included in Table 1. Compound 9 had the highest O3A score of 4002.51 and hence was selected as the template upon which the remaining structures were superimposed. The model’s statistical parameters were computed for Five (5) Principal Components (PC) amongst which the fifth PC (PC = 5) performed relatively better with R2 value of 0.9777, SDEC = 0.0593, and F-test = 105.028. The statistical parameters available in Table 3 were those associated with PC = 5. The predictive strength of the regression models on new datasets of compounds can be estimated by cross-validation (Grohmann and Schindler 2008). A cross-validated coefficient of correlation (Q2) ≥ 0.50 indicates a good QSAR model. Here, three (3) types of Q2 were calculated; Leave-one-out (LOO), Leave-two-out (LTO), and Leave-many-out (LMO), together with their associated Standard Error of Prediction (SDEP), which all passed the criterion (i.e. Q2 ≥ 0.50).

A linear correlation between the CoMFA descriptors (independent variables) and the activity values (dependent variables) was established by the PLS analysis method. The lower residual values between the predicted and observed activity values (Table 1) shows a strong predictive strength of the model. This was supported by the clustering of points along the lines of best fit in the plots of predicted pIC50 versus the observed pIC50 (Fig. 4). The CoMFA QSAR equation is summarized graphically as a 3D contour map, which shows the regions within the molecules’ 3-D structural space where steric and electrostatic fields are associated with extreme values. The underlying principle behind CoMFA is that variations in the shape and strength of non-covalent interaction fields surrounding the molecules, such as steric or electrostatic fields can be related to changes in binding affinities (Kakarla et al. 2016). Therefore, molecular fields are key factors in binding affinity. The steric and electrostatic field contributions were 65.32 and 34.68% respectively (Table 3).

From the steric field contour maps available in Fig. 5 (a-b), the red contours represent regions of unfavorable steric bulk, while the blue contours show regions of favorable steric bulk. Regions in which steric bulk may reduce the activity or affinity of the compound include position 3 on the left-sided aromatic ring and position 4 on the right-sided aromatic ring (Fig. 5a). For example, substituting the methoxy group on position 3 or 4 with a less heavy hydroxyl group could improve the binding affinity of the compound. On the other hand, more steric bulk favorable regions were identified (Fig. 5b), which include positions 3 and 5 of the right-sided benzene ring and positions 4 and 5 of the left-sided aromatic ring. This implies that the introduction of bulky substituent groups at these positions will improve the inhibitory activity of the molecule. From the electrostatic field contour maps available in Fig. 6 (a-b), yellow contours represent regions favored by high electron density or unfavorable to electron-withdrawing substituents, while the green contours represent regions of unfavorable high electron density or favorable to electron-withdrawing groups. The various regions in which the introduction of electron-withdrawing groups could reduce or improve the inhibitory activity or binding affinity are shown in Fig. 6. The electrostatic field contribution is 34.68% and therefore influenced the binding affinity of the compounds far less than the steric field. In general, contour map analysis serves as a guide to designing new molecules with improved potency by adhering to the information encoded in the contour maps.

Drug design

A total of seven (7) compounds were designed using the information provided by the 3-D QSAR (CoMFA) contour maps, while also performing a molecular docking study to provide insight into their mode of binding interactions with PdxK. Their molecular structures and docking scores were presented in Table 4, while Table 5 shows their predicted pharmacological interaction profiles with PdxK as well as those of the template molecule (Compound 9) and reference drug (Pentamidine). Also, the binding interactions of compound 9, pentamidine, and these compounds (excluding 9b, d, and g) with the active sites of PdxK as visualized via Biovia discovery studio were presented in Figs. 7 and 8.

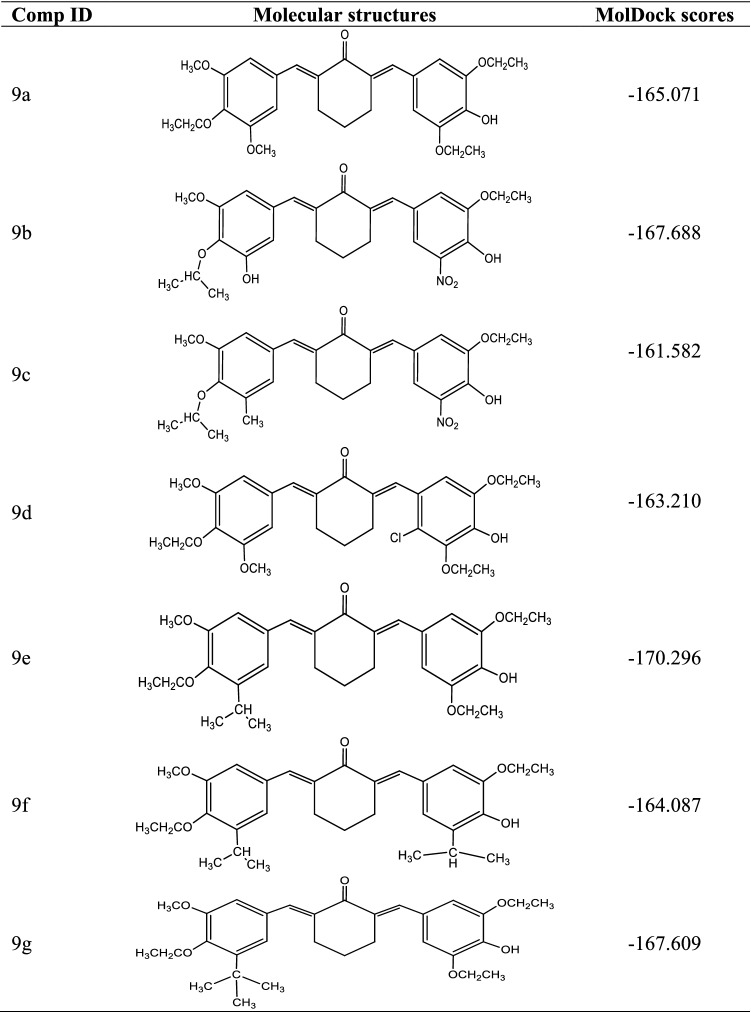

Table 4.

Molecular structures and MolDock scores of the newly designed compounds

9* Template

Table 5.

Predicted binding interaction profiles of compound 9, pentamidine, and the newly designed molecules with PdxK receptor

| ID | Hydrogen bond interactions | Electrostatic/Hydrophobic interactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid | Type | Distance (Å) | ||

| 9* | SER-188 | Conventional | 2.16, 2.50 | HIS-46 (π- π T-shaped), LYS-187 (π-alkyl) |

| GLY-230 | Conventional | 1.88 | ||

| THR-229 | Conventional | 3.55 | ||

| HIS-46 | Conventional | 2.84 | ||

| GLY-230 | C–H | 2.77 | ||

| SER-47 | C–H | 2.56 | ||

| ASP-125 | C–H | 2.97 | ||

| 9a | SER-188 | Conventional | 2.09 | Alkyl (ARG-127, LEU-198, VAL-19, VAL-121), π-alkyl (HIS-46, LYS-187) |

| GLY-230 | Conventional | 1.60 | ||

| THR-229 | Conventional | 3.78 | ||

| THR-229 | C–H | 2.79 | ||

| SER-47 | C–H | 2.40 | ||

| 9c | SER-188 | Conventional | 2.18 | Alkyl (LEU-198, VAL-19, VAL-121), π-alkyl (LYS-187, HIS-46) |

| GLY-230 | Conventional | 1.33 | ||

| THR-229 | Conventional | 2.48 | ||

| GLY-230 | C–H | 2.74 | ||

| 9e | GLY-228 | Conventional | 2.13 | LYS-187 (π-cation), ASP-231 (π-anion), π-alkyl (TYR-85, TYR-129, TYR-152, PHE-233, VAL-19, HIS-46), Alkyl (LEU-257, LYS-187, VAL-121, VAL-19) |

| SER-47 | C–H | 3.09 | ||

| ASP-124 | C–H | 2.74 | ||

| TYR-226 | C–H | 2.54 | ||

| THR-227 | C–H | 2.95 | ||

| THR-229 | C–H | 2.78 | ||

| 9f | SER-188 | Conventional | 2.29 | Alkyl (VAL-19, LEU-198, VAL-121, LYS-187), π-alkyl (PHE-233, LYS-187, TYR-129, HIS-46) |

| GLY-230 | Conventional | 1.49 | ||

| THR-229 | Conventional | 3.58 | ||

| SER-47 | C–H | 2.44 | ||

| ASP-124 | C–H | 2.26 | ||

| Pentamidine | SER-47 | Conventional | 2.52 | VAL-19 (π-alkyl) and unfavorable donor-donor clash with SER-12 |

| THR-229 | Conventional | 2.53 | ||

| TYR-129 | C-H | 2.36 | ||

| GLY-228 | π-donor | 2.39 | ||

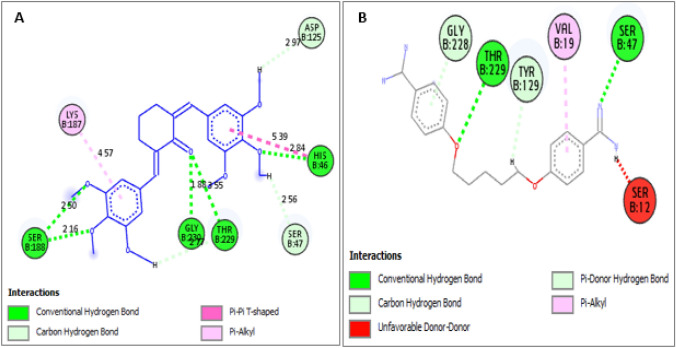

Fig. 7.

Binding interactions of PdxK with A Compound 9. B Pentamidine

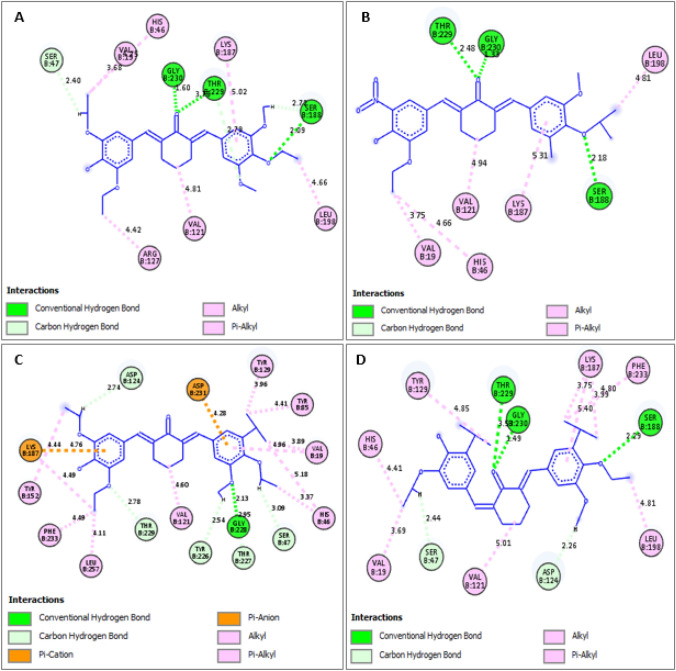

Fig. 8.

Binding interactions of PdxK with A 9a, B 9c C, 9e, and D 9f

The newly designed analogs were found to possess higher binding affinities (MolDock scores) than the template compound and reference drug (pentamidine) in the order 9e (− 170.296) > 9b (− 167.688) > 9 g (− 167.609) > 9a (− 165.071) > 9f (− 164.087) > 9d (− 163.210) > 9c (− 161.582) > 9 (− 161.064) > pentamidine (− 137.827). The major modification carried out was the steric field adjustment by either substituting the methoxy group with bulkier group substituents such as ethoxy, isopropoxy, isopropyl, and tert-butyl in areas where increased steric bulk improves the binding affinity and introduction of the less bulky hydroxyl group in areas where reduced steric bulk improves the binding affinity. The electrostatic field modification did not improve the binding affinity as such. In fact, the incorporation of an electron-withdrawing group (Chloro substituent) into 9a to form 9d reduced the binding score from 165.071 to − 163.210. This justified the finding that the steric field contribution is 65.32%. Also, the template together with these newly designed analogs showed excellent binding interactions with the receptor (PdxK). More interactions were visible in the binding profiles of the template molecule and the newly designed compounds than that in the reference drug, Pentamidine. Additionally, none of the new compounds including the template molecule bind unfavorably with the target protein, unlike pentamidine with an unfavorable donor-donor clash with SER-12 (Fig. 7). Hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, the two most important interactions in drug-receptor binding were dominant in the binding interaction profiles of the new compounds including the template. The π-anion and π-cation electrostatic interactions were only visible in the binding interaction profile of compound 9e. Therefore, the newly designed diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs have shown great potential in targeting pyridoxal kinase, an absolutely important enzyme for the growth and viability of leishmanial organisms.

Evaluation of pharmacokinetic properties

Drug-likeness analysis and ADMET studies were conducted on compound 9 and the seven (7) newly designed analogs to ascertain their oral bioavailability, toxicity, and safety profiles. The results of the investigations were presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Predicted drug-likeness/ADMET properties of compound 9 and the newly designed diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs

| Molecular/ADMET properties | 9* | Newly designed compounds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9a | 9b | 9c | 9d | 9e | 9f | 9 g | ||

| Molecular properties | ||||||||

| Molecular weight | 454.52 | 482.57 | 483.52 | 481.55 | 517.02 | 494.63 | 492.66 | 508.66 |

| LogP | 4.96 | 5.83 | 5.42 | 6.02 | 6.48 | 6.94 | 7.67 | 7.11 |

| Rotatable bonds | 8 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| Hydrogen bond acceptors | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Hydrogen bond donors | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Human oral bioavailability | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Absorption | ||||||||

| Human intestinal absorption (%) | 98.59 | 93.96 | 95.69 | 100 | 92.84 | 92.94 | 92.71 | 92.84 |

| Skin permeability | − 2.79 | − 2.81 | − 2.74 | − 2.74 | − 2.81 | − 2.75 | − 2.73 | − 2.74 |

| P-glycoprotein substrate | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| P-glycoprotein I inhibitor | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| P-glycoprotein II inhibitor | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Distribution | ||||||||

| BBB permeability (LogBB) | − 0.885 | − 0.743 | − 0.335 | − 0.778 | − 0.902 | − 0.55 | − 0.823 | − 0.507 |

| CNS permeability (LogPS) | − 2.846 | − 2.86 | − 2.695 | − 1.975 | − 2.797 | − 2.557 | − 1.643 | − 2.461 |

| Metabolism | ||||||||

| CYP2D6 substrate | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| CYP3A4 substrate | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Excretion | ||||||||

| Total clearance (Log ml/min/kg) | 0.645 | 0.733 | 0.519 | 0.733 | 0.397 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.441 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | |

| toxicity | ||||||||

| AMES toxicity | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| hERG inhibitor | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Hepatotoxicity | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Skin sensitization | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Eye irritation | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Carcinogenicity | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Nephrotoxicity | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

Lipinski’s approach to ascertaining the oral bioavailability of compounds has been widely applied in the discovery of new drug molecules (Ugbe et al. 2021; Sadeghi et al. 2022). It asserts that a drug molecule may likely not be orally bioavailable when it has a Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) of greater than 5, a Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) > 10, Molecular Weight (MW) > 500, oil/water distribution coefficient (LogP) > 5, and a number of rotatable bonds > 10 (Lipinski et al. 2001). Whenever a molecule passed at least four of the provisions of the ROF, it is said to comply with Lipinski’s rule for oral bioavailability (Ibrahim et al. 2020). As observed in Table 6, all the tested compounds passed the drug-likeness test with an exception of 9d and 9 g. The template molecule passed all of the five provisions, while the new compounds (9a, b, c, e, and f) violated only the provision for LogP. Therefore, all the tested molecules are said to be orally bioavailable.

The estimated ADMET properties reported in Table 6, showed good Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA) (greater than 90%) for all tested compounds. Skin permeability is a key factor in transdermal drug delivery development, with skin permeation constant LogKp > − 2.50 indicating poor skin permeability. As a result, the various compounds showed LogKp values < − 2.50, connoting good skin permeability. Drug molecule penetration through the Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) and Central Nervous System (CNS) comes with certain criteria, which specify that for a drug molecule to penetrate the BBB and CNS readily, the logarithmic ratio of brain-to-plasma drug concentration (logBB) must be > 0.3 and the blood–brain permeability-surface area product (logPS) be > − 2 respectively. Consequently, none of these molecules were predicted to readily penetrate the BBB and CNS with an exception of 9c and f which were predicted to be CNS permeable.

Furthermore, some group of enzymes called cytochrome P450 enzymes are important in the body to facilitate drug metabolism and to help in their excretion. The two major isoforms enhancing drug metabolism, CYP-34A and CYP-2D6 were tested. The tested molecules were found to be substrates and inhibitors of CYP-34A only. Also, all the tested molecules are inhibitors of P-glycoprotein, an enzyme that acts as a biological barrier by extruding toxins and xenobiotics, including drugs out of cells. This means that these molecules when taken into the human system may likely not be effluated out of the target cells by this enzyme. The extent of drug removal from the body is determined by the drug’s total clearance. The range of values of total clearance for all the tested molecules is good. The renal Organic Cation Transporter 2 (OCT2) plays a critical role in the disposition and renal clearance of drugs and endogenous compounds. However, the activities of OCT2 may cause unwanted drug-drug interactions, which makes it necessary to ascertain whether a drug molecule is an OCT2 substrate or inhibitor. As seen in Table 6, all the tested compounds are non-OCT2 substrates.

Additionally, some toxicity indices were predicted to ascertain the safety profiles of these molecules. The Ames test is a widely applied method to ascertain a compound’s mutagenic potential. A positive test indicates that the compound is mutagenic. Interestingly, all the tested compounds showed negative Ames toxicity, thereby showing no risk of mutagenicity. The inhibition of the human ether-a-go-go gene (hERG) is responsible for the acquired long QT syndrome, resulting in heartbeat irregularity issues. However, none of the tested compounds was implicated in this regard. Furthermore, all the tested compounds showed negative hepatotoxicity except 9b. Creditably, all the molecules showed negative skin sensitization, eye irritation, carcinogenicity, and nephrotoxicity. Similar results were obtained elsewhere for the toxicity evaluation of some isoquinoline alkaloids by Sadeghi and Miroliaei (2022). Based on the toxicity analysis conducted, all the tested compounds were considered to exhibit safe toxicity profiles. Therefore, the newly designed compounds have displayed excellent pharmacokinetic profiles, especially in the areas of bioavailability (excluding 9d and g) and toxicity.

Molecular dynamics study

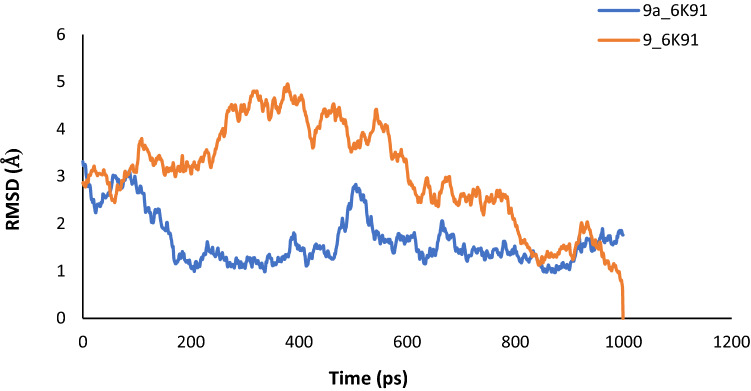

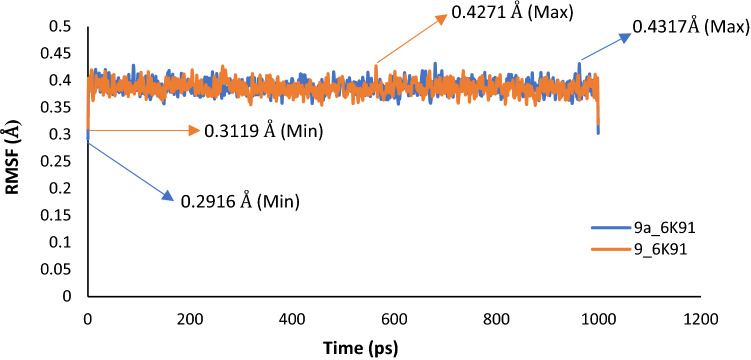

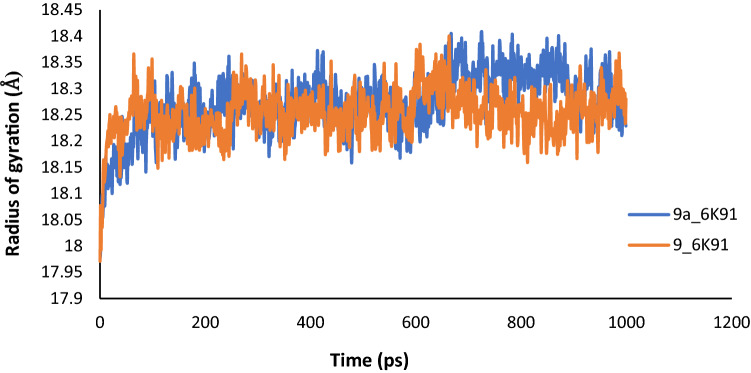

To ascertain the stability and rigidity of the protein–ligand interactions, the complexes of compound 9 (template) and compound 9a were subjected to MD simulation. The results of the simulation summarized as plots of Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF), and Radius of gyration (Rg) versus the time in picoseconds (ps), were presented in Figs. 9, 10 and 11.

Fig. 9.

RMSD plot for MD simulation of Compound 9 and 9a with PdxK

Fig. 10.

RMSF plot for MD simulation of Compound 9 and 9a with PdxK

Fig. 11.

Plot of Radius of gyration (Rg) versus time for MD simulation of Compound 9 and 9a with PdxK

The average RMSD values were estimated as 3.0601 Å and 1.6435 Å for 9_6K91 and 9a_6K91 respectively, indicating that 9a_6K91 was relatively more stable during the trajectory. The RMSD plot (Fig. 9) for the various complexes showed that the complexes were fast attaining stability and nearing equilibrium as the simulation progresses especially after 500 ps. This is because the deviation tends to drop as the simulation progresses (Edache et al. 2020). The RMSF is more like a calculation of the flexibility or the extent of movement of individual residue during a simulation. The RMSF plot in Fig. 10 showed that the flexibilities of the protein residues were almost constant during the trajectory, as shown by a negligible difference between the minimum and maximum fluctuation values of 0.1152 Å for 9_6K91 and 0.1401 Å for 9a_6K91. This is an indication of the stability of the interactions during the simulation. The Rg is the measure of the degree of compactness of a protein during the trajectory. Decreasing Rg indicates a decreasing residues’ flexibilities and more stability for the protein. The predicted average Rg values for 9_6K91 and 9a_6K91 were 18.2542Å and 18.2716 Å respectively, and all through the trajectory, the variation of Rg with time (Fig. 11) was less than 0.50 Å for both complexes, connoting slight changes in the protein compactness as the simulation progresses, which therefore means the stability of the complexes.

Furthermore, the result of binding free energy (MM/GBSA) estimated for 9_6K91 and 9a_6K91 by MolAICal is shown in Table 7. The negative values of the estimated binding free energy (MM/GBSA) for both complexes (− 65.2177 kcal/mol and − 58.433 kcal/mol for 9_6K91 and 9a_6K91 respectively) show the favorability of the ligand–protein binding, are energetically stable and binds strongly with the receptor. A similar observation was reported elsewhere for binding free energy change (MM/GBSA) calculated for some analogs of 2-arylbenzimidazole in a complex with PdxK (Ugbe et al. 2023).

Table 7.

Binding free energy parameters of 9_6K91 and 9a_6K91 complexes

| Energy (kcal/mol) | 9_6k91 | 9a_6k91 |

|---|---|---|

| ∆E(internal) | − 4.2275 | 17.8685 |

| ∆E(electrostatic) + ∆G(solvation) | − 9.8912 | − 24.5187 |

| ∆E (Van der Waal) | − 51.099 | − 51.7828 |

| ∆G binding (MM/GBSA) | − 65.2177 | − 58.433 |

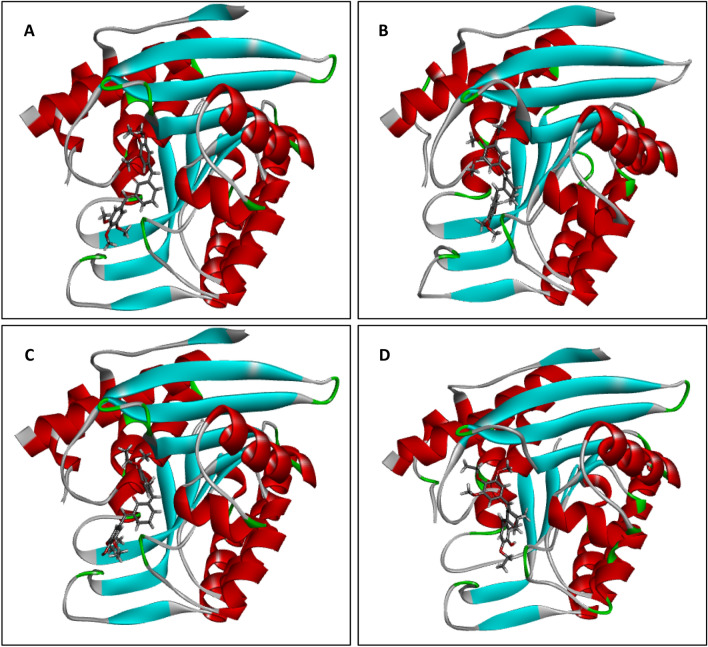

To further confirm the stability of the ligand–protein interactions during the simulation, the complexes were visualized using the Biovia discovery studio. The orientations of the template (9) and the new analog (9a) in the active site of the receptor before and after the MD simulation were shown in Fig. 12, while the resulting binding interactions were presented in Fig. 13. As shown in Fig. 12, there is no significant change in the structural orientation of both complexes, that is, the positions of both inhibitors (9 and 9a) in the active site of the receptor were retained during simulation. This is also, a confirmation that both complexes were stable during the trajectory. From Fig. 13, several interactions were visible majorly H-bonding and hydrophobic interactions, that further confirmed the stability of the complexes during the trajectory. A total of Four (4) H-bonding interactions were visible in 9_6K91 including Two (2) conventional H-bonding with THR-229 and GLY-230 at distances of 3.09 Å and 2.52Å respectively, and C – H bonding with SER-12 and LYS-187 at 2.58 Å and 2.84 Å respectively. Others are alkyl and π-alkyl hydrophobic interactions with VAL-121. For 9_6K91 on the other hand, only Two (2) H-bonding interactions were formed including One (1) conventional H-bonding with HSD-46 at 2.24 Å and One (1) C-H bonding with GLY-224 at 2.97 Å. Others include alkyl and π-alkyl hydrophobic interactions with VAL-121, TYR-85, TYR-129, ILE-261, and LEU-257. H-bonding dominated the binding interactions of 9 with PdxK, while 9a_6k91 was more hydrophobic interactions after the MD simulation.

Fig. 12.

3D structural orientation of the ligand–protein complexes. A Non-simulated 9_6K91, B Simulated 9_6K91, C Non-simulated 9a_6K91, D Simulated 9a_6K91

Fig. 13.

2D representation of binding interactions of the simulated complexes A 9_6K91, B 9a_6K91

Conclusions

The combined molecular docking screening and 3-D QSAR modeling approach led to the design of Seven (7) diarylidene cyclohexanone analogs (9a, b, c, d, e, f, and g) using the most active molecule (compound 9, MolDock score = − 161.064) as the template. These molecules were predicted to be orally bioavailable (except 9d and 9 g), less toxic (except 9b which is hepatotoxic), and possessed excellent pharmacokinetic profiles. The predicted pharmacological interaction profiles of these compounds generally showed a good fitting into the target site cavities. Also, the MD simulation revealed the stability of the ligand–protein interactions of 9 and 9a. Hence, the newly designed molecules especially 9a could be developed and further evaluated as potential drug candidates for the treatment of leishmaniasis.

Acknowledgements

All authors are well acknowledged.

Author contributions

GAS and AU conceived and designed the study. FAU carried out the study and drafted the manuscript. IA conducted the technical editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Data availability

All data related to this study are included herein otherwise available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdullahi SA, Uzairu A, Shallangwa GA, Uba S, Umar AB. In-silico activity prediction, structure-based drug design, molecular docking and pharmacokinetic studies of selected quinazoline derivatives for their antiproliferative activity against triple negative breast cancer (MDA-MB231) cell line. Bullet Nat Res Centre. 2022;46:2. doi: 10.1186/s42269-021-00690-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adeniji SE, Arthur DE, Abdullahi M, Abdullahi A, Ugbe FA. Computer-aided modeling of triazole analogues, docking studies of the compounds on DNA gyrase enzyme and design of new hypothetical compounds with efficient activities. J Biomole Structure Dyn. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1852963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Attraqchi OH, Mordi MN. 2D- and 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and virtual screening of pyrido [2,3-d] pyrimidin-7-one-based CDK4 inhibitors. J Appl Pharma Sci. 2022;12(01):165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Are S, Gatreddi S, Jakkula P, Qureshi IA. Structural attributes and substrate specificity of pyridoxal kinase from Leishmania donovani. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;152:812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell JB, Holloway GA. New substructure filters for removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J Med Chem. 2010;53(7):2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Q, Tan S, Xu T, Liu H, Huang J, Yao X. MolAICal: a soft tool for 3D drug design of protein targets by artificial intelligence and classical algorithm. Brief Bioinform. 2020;00(2020):1–12. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito CCB, da Silva HVC, Brondani DJ, de Faria AR, Ximenes RM, da Silva IM, de Albuquerque JFC, Castilho MS. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thiazole derivatives as LbSOD inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2019;34(1):333–342. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1550752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandru H, Sharada AC, Bettadaiah BK, Kumar CSA, Rangappa KS, Sunila JK. In vivo growth inhibitory and anti-angiogenic effects of synthetic novel dienone cyclopropoxy curcumin analogs on mouse Ehrlich ascites tumor. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:7696–7703. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementino LDC, Fernandes GFS, Prokopczyk IM, Laurindo WC, Toyama D, Motta BP. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of N-oxide derivatives with potent in vivo antileishmanial activity. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11):e0259008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Din ZU, Trapp MA, Soman de Medeiros L, Lazarin-Bidóia D, Garcia FP, Peron F, Rodrigues-Filho E. Symmetrical and unsymmetrical substituted 2,5-diarylidene cyclohexanones as anti-parasitic compounds. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;155:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edache EI, Samuel H, Sulyman YI, Arinze O, Ayine OI. QSAR and molecular docking analysis of substituted tetraketone and benzyl-benzoate analogs as anti-tyrosine: a novel approach to anti-tyrosine kinase drug design and discovery. Chem Res J. 2020;5(6):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Edache EI, Uzairu A, Mamza PA, Shallangwa GA. Computational modeling and analysis of the theoretical structure of thiazolino 2-pyridone amide inhibitors for Yersinia pseudo-tuberculosis and Chlamydia trachomatis Infectivity. Bull Sci Res. 2022;4(1):14–39. [Google Scholar]

- ElMchichi L, Belhassan A, Lakhlifi A, Bouachrine M. 3D-QSAR study of the chalcone derivatives as anticancer agents. Hindawi J Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/5268985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Lu Y, Chen X, Tekwani B, Li X, Shen Y. Anti-Leishmanial and cytotoxic activities of a series of maleimides: synthesis, biological evaluation and structure-activity relationship. Molecules. 2018;23:2878. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann R, Schindler T. Toward robust QSPR models: synergistic utilization of robust regression and variable elimination. J Comput Chem. 2008;29(6):847–860. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MT, Uzairu A, Shallangwa GA, Uba S. Lead identification of some anti-cancer agents with prominent activity against Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) and structure-based design. Chem Afr. 2020;3:1023–1044. doi: 10.1007/s42250-020-00191-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kakarla P, Inupakutika M, Devireddy AR, Gunda SK, Willmon TM, Ranjana KC, Shrestha U, Ranaweera I, Hernandez AJ, Barr S, Varela MF. 3D-QSAR and contour map analysis of tariquidar analogues as Multidrug Resistance Protein-1 (MRP-1) inhibitors. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2016;7(2):554–572. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.7(2).554-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Sharma M, Rakesh BR, Malik CK, Neelagiri S, Neerupudi KB, Garg P, Singh S. Pyridoxal kinase: a vitamin B6 salvage pathway enzyme from Leishmania donovani. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;119:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Cheng X, Swails JM, Yeom MS, Eastman PK, Lemkul JA, Wei S, Buckner J, Jeong JC, Qi Y, Jo S, Pande VS, Case DA, Brooks CL, MacKerell AD, Jr, Klauda JB, Im M. CHARMM-GUI input generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM simulations using the CHARMM36 additive force field. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016;12:405–413. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniba F (2019) Tutorial: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation using Gromacs. Bioinformatics Review 5(12). https://bioinformaticsreview.com/20191210/tutorial-molecular-dynamics-md-simulation-using-gromacs/. Accessed 22 Apr 2022

- Pires DE, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic properties using graph-based signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58(9):4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi M, Miroliaei M. Inhibitory effects of selected isoquinoline alkaloids against main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2, in silico study. In Silico Pharmacology. 2022;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40203-022-00122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi M, Miroliaei M, Taslimi P, Moradi M. In silico analysis of the molecular interaction and bioavailability properties between some alkaloids and human serum albumin. Struct Chem. 2022;33:1199–1212. doi: 10.1007/s11224-022-01925-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Yang AW, Hung A, Lenon GB. Screening for a potential therapeutic agent from the herbal formula in the 4th edition of the Chinese national guidelines for the initial-stage management of COVID-19 via molecular docking. Evid Based Comp Alt Med. 2020;2020:3219840. doi: 10.1155/2020/3219840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosco P, Balle T. Open3DQSAR: a new open-source software aimed at high-throughput chemometric analysis of molecular interaction fields. J Mol Model. 2011;17(1):201–208. doi: 10.1007/s00894-010-0684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugbe FA, Shallangwa GA, Uzairu A, Abdulkadir I. Activity modeling, molecular docking and pharmacokinetic studies of some boron-pleuromutilins as anti-wolbachia agents with potential for treatment of filarial diseases. Chem Data Collect. 2021;36:100783. doi: 10.1016/j.cdc.2021.100783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ugbe FA, Shallangwa GA, Uzairu A, Abdulkadir I. A combined 2-D and 3-D QSAR modeling, molecular docking study, design, and pharmacokinetic profling of some arylimidamide-azole hybrids as superior L. donovani inhibitors. Bull Nat Res Centre. 2022;46:189. doi: 10.1186/s42269-022-00874-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ugbe FA, Shallangwa GA, Uzairu A, Abdulkadir I. Theoretical modeling and design of some pyrazolopyrimidine derivatives as Wolbachia inhibitors, targeting lymphatic flariasis and onchocerciasis. In Silico Pharmacol. 2022;10:8. doi: 10.1007/s40203-022-00123-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugbe FA, Shallangwa GA, Uzairu A, Abdulkadir I. Theoretical activity prediction, structure-based design, molecular docking and pharmacokinetic studies of some maleimides against Leishmania donovani for the treatment of leishmaniasis. Bull Nat Res Centre. 2022;46:92. doi: 10.1186/s42269-022-00779-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ugbe FA, Shallangwa GA, Uzairu A, Abdulkadir I. A 2-D QSAR modeling, molecular docking study and design of 2-Arylbenzimidazole derivatives as novel leishmanial inhibitors: a molecular dynamics study. Advan J Chem Sect A. 2023;6(1):50–64. doi: 10.22034/AJCA.2023.365873.1337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A, Chandrakar P, Gupta S, Parmar N, Singh SK, Rashid M, Kushwaha P, Wahajuddin M, Sashidhara KV, Kar S. Synthesis, biological evaluation, structure−activity relationship, and mechanism of action studies of quinoline−metronidazole derivatives against experimental visceral Leishmaniasis. J Med Chem. 2019;62:5655–5671. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma J, Khedkar V, Coutinho E. 3D-QSAR in drug design—a review. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10(1):95–115. doi: 10.2174/156802610790232260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dong H, Qin Q. QSAR models on aminopyrazole-substituted resorcylate compounds as Hsp90 inhibitors. J Comput Sci Eng. 2020;48:1146–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Lou C, Sun L, Li J, Cai Y, Wang Z, Tang Y. AdmetSAR 2.0: web service for prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Bioinformatics. 2018;35(6):1067–1069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf MD, Mukherjee D, Pal A, Dey S, Mandal S, Pal C, Adhikari S. Synthesis and biological evaluation of Ferrocenylquinoline as a potential antileishmanial agent. ChemMedChem. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yan J, Wang H, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhao D. Molecular docking, 3D-QSAR, and molecular dynamics simulations of thieno [3, 2-b] pyrrole derivatives against anticancer targets of KDM1A/LSD1. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1726819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data related to this study are included herein otherwise available on request.