Abstract

Background & Aims

Oxidative stress-mediated ferroptosis and macrophage-related inflammation play an important role in various liver diseases. Here, we explored if and how hepatocyte ferroptosis regulates macrophage stimulator of interferon genes (STING) activation in the development of spontaneous liver damage, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis.

Methods

We used a transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) deficiency-induced model of spontaneous liver damage, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis to investigate hepatocyte ferroptosis and its impact on macrophage STING signalling. Primary hepatocytes and macrophages were used for in vitro experiments.

Results

Significant liver injury and increased numbers of intrahepatic M1 macrophages were found in hepatocyte-specific TAK1-deficient (TAK1ΔHEP) mice, peaking at 4 weeks and gradually decreasing at 8 and 12 weeks. Meanwhile, activation of STING signalling was observed in livers from TAK1ΔHEP mice at 4 weeks and had decreased at 8 and 12 weeks. Treatment with a STING inhibitor promoted macrophage M2 polarisation and alleviated liver injury, fibrosis, and tumour burden. TAK1 deficiency exacerbated liver iron metabolism in mice with a high-iron diet. Moreover, consistent with the results from single-cell RNA-Seq dataset, TAK1ΔHEP mice demonstrated an increased oxidative response and hepatocellular ferroptosis, which could be inhibited by reactive oxygen species scavenging. Suppression of ferroptosis by ferrostatin-1 inhibited the activation of macrophage STING signalling, leading to attenuated liver injury and fibrosis and a reduced tumour burden. Mechanistically, increased intrahepatic and serum levels of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine were detected in TAK1ΔHEP mice, which was suppressed by ferroptosis inhibition. Treatment with 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine antibody inhibited macrophage STING activation in TAK1ΔHEP mice.

Conclusions

Hepatocellular ferroptosis-derived oxidative DNA damage promotes macrophage STING activation to facilitate the development of liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis. Inhibition of macrophage STING may represent a novel therapeutic approach for the prevention of chronic liver disease.

Impact and implications

The precise mechanism by which hepatocyte ferroptosis regulates macrophage STING activation in the progression of liver damage, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis remains unclear. Herein, we show that deletion of TAK1 in hepatocytes caused oxidative stress-mediated ferroptosis and macrophage-related inflammation in the development of spontaneous liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Keywords: TAK1, STING, Oxidative stress, Ferroptosis, Tumorigenesis

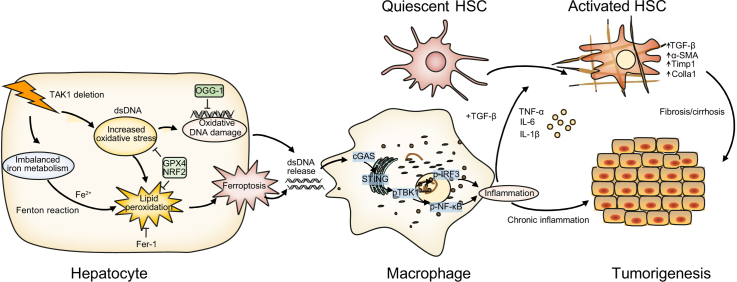

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

TAK1 deficiency promotes hepatic ferroptosis by inducing oxidative stress and imbalanced iron metabolism.

-

•

Oxidative DNA damage from hepatocytes promotes activation of macrophage STING signalling in TAK1-deficient livers.

-

•

Targeting macrophage STING signalling or hepatocellular ferroptosis could be beneficial in the treatment of liver injury, fibrosis, and tumours.

Introduction

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by excessive phospholipid peroxidation.1 Various types of organ injuries and degenerative pathologies are driven by ferroptosis. Excessive or defective ferroptosis contributes to tissue damage and tumorigenesis.2 Both anti- and protumorigenic roles of ferroptosis have been reported in different models.3 Unrestricted cell death or tissue damage may cause an inflammation-related immunosuppressive microenvironment, leading to tumour progression or recurrence.4 Ferroptosis has also been implicated in the development and therapeutic responses of various types of tumours. The proferroptotic activity of several antitumour drugs, including sorafenib and sulfasalazine, has been revealed in preclinical models.5

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) represent a group of highly reactive molecules that have a role in a number of important cellular signalling pathways. The overproduction of ROS has been implicated in a variety of diseases, including cancer, inflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases.6 Excessive accumulation of ROS can also trigger programmed cell death (PCD), of which ferroptosis is initiated by the failure of antioxidant defences, resulting in continued lipid peroxidation, eventual cell death, and release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to activate inflammation.7

The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase- (cGAS-) stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway has emerged as a key mediator of inflammation.8 Beyond the vital role of cGAS-STING signalling in the antimicrobial innate immune response, emerging evidence has indicated its function in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases and antitumour immunity. Both antitumorigenic and protumorigenic functions of STING signalling have been reported, which are dependent on the specific context and stage of tumour progression.9 DNA or cGAMP from apoptotic and necrotic malignant cells can be engulfed or transferred into the cytosol of dendritic cells and macrophages, which further activates cGAS-STING signalling and promotes the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and primes other immune cells, such as CD8 T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, to restrict tumorigenesis.10 In contrast, mutation of the proto-oncogene KRAS induced chronic activation of cGAS-STING signalling, leading to nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)-mediated persistent inflammation and cancer progression.11

Oxidative DNA damage not only contributes to genomic instability, which is a typical cancer hallmark as well as an important driving force of cancer, but also plays prominent roles in cGAS-STING pathway-related antitumour immunity or promoting inflammation-driven carcinogenesis.12 Inflammation plays a vital role in liver injury, regeneration, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis. A low-level inflammatory response is essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis in response to potential insults such as infection, trauma, and metabolic stress.13 Overactivation or persistent inflammation results in tissue damage, remodelling, and cancer development. Up to 20% of cancers are linked to chronic infections.14

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) is a member of the MAP kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K) family. NF-κB and JNK activation by TAK1 plays a key role in regulating cell survival, inflammation, and tumorigenesis.15 TAK1 is critical for the survival of both haematopoietic cells and hepatocytes. TAK1 deletions or losses can be detected in various types of human cancers and are positively associated with tumour progression and poor patient survival.[16], [17], [18], [19], [20] Elevated TAK1 expression and activity have also been detected in several human cancers,[21], [22], [23], [24] including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),25,26 indicating a dual role of TAK1 in regulating tumour initiation, progression, and metastasis. Mice with hepatocyte-specific deletions of TAK1 developed spontaneous liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis.27 Therefore, further studies are needed to determine the role of TAK1 signalling in regulating liver tumour initiation, progression, metastasis, and therapeutic response.

Various types of cell death regulated by TAK1 have been reported. TAK1 deficiency triggered inflammasome activation and pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis of TLR-primed macrophages.28 Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers pyroptosis of macrophages.29 However, the precise molecular and cellular mechanisms by which TAK1 regulates liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis remain unclear.

In the present study, we investigated the interplay of TAK1 deficiency-induced hepatocellular ferroptosis in regulating macrophage STING signalling. Ferroptosis of hepatocytes promoted oxidative DNA damage to activate macrophage STING signalling, which in turn facilitated the development of spontaneous liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis in hepatocyte-specific TAK1-deficient mice. Our findings suggest a critical role of oxidative DNA damage from hepatocellular ferroptosis in regulating macrophage STING signalling during liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis. Inhibition of hepatocellular ferroptosis or the macrophage STING signalling pathway would be a promising therapeutic target for intervening in chronic liver disease.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

Patients with acute liver injury (ALI), fibrosis, HCC, and normal control patients (six/group) undergoing liver surgery in the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University Hospital were enrolled in the current study (Table S2). Liver samples were obtained from patients who underwent hepatectomy or percutaneous liver biopsy. Liver samples were collected from six patients with ALI; six patients with pathologically diagnosed liver fibrosis, and six patients with pathologically diagnosed HCC. The control individuals that were included had no history of diabetes, alcohol abuse, or viral hepatitis. Control samples were taken from normal liver tissues at the edge of resected haemangioma. All samples were kept frozen (-80 °C). Informed consent was obtained from each patient. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Mice and treatments

TAK1-LoxP mice (TAK1FL/FL) were crossed with hepatocyte-specific Cre mice (Alb-Cre) to generate hepatocyte-specific TAK1 knockout mice (TAK1ΔHEP), which were housed at GemPharmatech Co. Ltd. (Nanjing, China). All mice were on the C57BL/6 background, and their genotype was determined by PCR from tail DNA. Cre-negative animals were used as wild-type controls. The mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions with free access to water and standard chow with supplements. The animal studies were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the protocol, which was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University.

For ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1, cat# HY-100579, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) treatment, ferrostatin-1 (5 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl) was administered to the mice by i.p. injection every day from 2 weeks of age to 12 weeks of age. Serum and liver samples were collected at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of age.

For C-176 (cat# HY-112906, MedChemExpress) treatment, 200 μmol of C-176 or vehicle (0.9% NaCl) was given to the mice twice a week from 2 weeks of age to 12 weeks of age. Serum and liver samples were collected at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of age, respectively.

For NAC (cat# HY-B0215, MedChemExpress) treatment, NAC (150 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl) was administered to the mice by i.p. injection every day from 2 weeks of age to 4 weeks of age.

For anti-8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (anti-8-OHdG) antibody (cat# GTX41980, GeneTex, CA, USA) treatment, anti-8-OHdG antibody (5 mg/kg body weight) and control IgG (5 mg/kg, cat# MAB004, R&D Systems) were administered to the mice by i.p. injection twice a week from 2 weeks of age to 4 weeks of age.

Liver function assay/biochemical assays

Mice blood was collected from mice via the inferior vena cava with a heparin-coated microhaematocrit tube and centrifugation for 15 min at 2,000 × g to obtain plasma. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using an automatic chemical analyser (Olympus Company AU5800, Tokyo, Japan).

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence

Liver specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 24 h and then embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm thick) were cut for H&E, Sirius Red staining, and Perls’ Prussian Blue staining.

For immunohistochemistry, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinised and used to assess α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (1:400, cat# 19245, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), F4/80 (1:200, cat# 70076, Cell Signaling Technology), 8-OHdG (1:200, cat# sc-66036, Santa Cruz, USA) and Ki67 (1:400, cat# 12202, Cell Signaling Technology). Images were acquired using a microscope (Nikon Ci-E).

For immunofluorescence, liver cryosections were deposited on glass slides. After blocking with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.2% Triton X-100, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies, including anti-F4/80 (1:200, cat# ab6640 Abcam, USA), anti-STING (1:200, cat# 19851-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-CD68 (1:200, cat# 26042, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-iNOS (1:200, cat# 18985-1-AP, Proteintech), and anti-CD206 (1:200, cat# 18704-1-AP, Proteintech) at 4 °C overnight. The secondary antibodies were conjugated with Alexa 488 (1:200, cat# 4408, or # 4412, Cell Signaling Technology) or Alexa 594 (1:200, cat# 8889, Cell Signaling Technology), and the nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

Cell isolation and treatment

Hepatocytes from TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice were isolated by two-step collagenase perfusion. In brief, livers were perfused in situ via the portal vein with 50 ml warmed (37 °C) HBSS (Ca2+ and Mg2+ free) containing EGTA (0.5 M), followed by collagenase IV (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA, 0.05% w/v, dissolved in HBSS with Ca2+ and Mg2+). Perfused livers were dissected and teased through 70-mm nylon mesh cell strainers. Hepatocytes were separated by an initial centrifugation at 50 × g for 3 min (the supernatant was collected for non-parenchymal cell isolation later, [NPC fraction]). The hepatocyte pellets were resuspended in DMEM (including 10% foetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, and 1% pen/strep) and centrifuged again. Then, the pellets were seeded into collagen-precoated plates.

For primary macrophage isolation, the collected NPC fraction was centrifuged at 500 × g for 8 min at 4 °C. Then, 25% Percoll was placed carefully on top of the 50% Percoll layer. The pellets were pooled, and the NPC suspension was carefully and slowly placed on top of the 25% density-gradient solution layer in such a way that a clear separation of the two layers was achieved. Then, centrifugation was performed at 800 × g for 15 min at 4 °C until the rotor stopped by itself. The NPCs were located in the interphase between the 25% and 50% density gradient layers. The cells were washed with PBS, centrifuged at 500 × g for 8 min at 4 °C, and then seeded for 30 min to increase macrophage purity. Nonadherent cells were removed by replacing the culture medium. Macrophages were cultured for 6 h in vitro. Cells were collected for further experiments.

To study the effects of STING inhibitors on macrophage polarisation, primary liver macrophages were pretreated for 1 h with C-176 (0.5 μM) or vehicle and co-cultured with TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP primary hepatocytes for 6 h. Primary macrophages were collected for Western blot analysis and RT-qPCR.

For co-culture study, isolated primary hepatocytes from TAK1FL/FL or TAK1ΔHEP mice were pretreated with or without Fer-1 (2 μM, MedChemExpress) and then co-cultured with primary macrophages for 12 h. Cells were harvested for Western blot analysis.

Data collection and gene set enrichment analysis

The data analysed in this study were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at GSE148859. Then, the dataset containing TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice was selected for subsequent analysis, and it included 18,495 cells. Hepatocytes were reclustered by using the CCA algorithm of Seurat (version 4.0.3). Downstream analysis was performed using Seurat (version 4.0.3) and the R package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) designed for single-cell gene expression datasets. Differentially expressed genes (cluster markers) were determined using the function FindAllMarkers of Seurat. Then, gene set enrichment analysis was implemented using the package clusterProfiler (version 3.16.1) with these genes, and a value of p <0.05 was set as the threshold to determine statistically significant enrichment of the gene sets. FerrDb was used to analyse hepatocyte ferroptosis-related genes.30 The ferroptosis gene set enrichment score was determined with the VISION v3.0.0 R package according to instructions provided on GitHub (https://github.com/YosefLab/VISION) using ferroptosis gene sets obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database.31 The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the gene expression between TAK1FL/FL macrophages and TAK1ΔHEP macrophages, and a value of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Transmission electron microscopy

Liver tissues were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) followed by 1% OsO4. After dehydration, thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for observation under an FEI Tecnai G2 electron microscope.

Measurement of malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal, superoxide dismutase, and the ratio of glutathione/glutathione disulfide

Liver sample malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels and glutathione/glutathione disulfide (GSH/GSSG) ratio were measured using an MDA Assay kit (Cat#S0131S, Beyotime, China), Lipid Peroxidation (4-HNE) Assay Kit (cat#ab238538, Abcam), SOD Assay Kit (Cat#S0109, Beyotime), and GSH/GSSG Assay Kit (Cat#S0053, Beyotime), respectively, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of serum and hepatic levels of ferritin and hepcidin

Serum and hepatic levels of ferritin and hepcidin were measured using the Mouse Ferritin ELISA Kit (cat#ab157713, Abcam) and Mouse Hepcidin ELISA Kit (cat#ab285280, Abcam) respectively, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Dihydroethidium and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate staining

To measure in situ ROS levels, frozen liver sections were incubated with dihydroethidium (DHE; 3 μM, Invitrogen) and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) (5 μM, Molecular Probes) at 37 °C for 30 min protected from light and were examined under a fluorescence microscope.

Measurement of C11-BODIPY content

Primary hepatocytes from TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilised with 0.2% Triton X-100. After washing with PBS, the hepatocytes were incubated with BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 (Invitrogen™ D3861, 5 μmol/L) for 30 min at 37 °C. DAPI was used to stain cell nuclei. Images were obtained on a Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 confocal microscope.

Measurement of serum and culture media levels of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine

The concentration of serum and culture media (8-OHdG) were determined by an 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine Assay Kit (cat# H165, Nanjing Jiancheng, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from liver tissue using TRIzol and subjected to reverse transcription with the Takara reverse transcriptase kit (Takara Bio, Tokyo, Japan). A SYBR RT–PCR Kit (Takara) was used for reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis. The PCR primer sequences are listed in Table S1. The expression of the respective genes was normalised to that of GAPDH as an internal control.

Western blotting analysis

Proteins from the liver tissue and macrophages were separated by 10–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking, the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including cGAS antibody (1:1000, cat# 31659, CST), STING antibody (1:1000, cat# 13647, CST), phospho-TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) antibody (1:1000, cat# 5483, CST) phospho-STING antibody (1:1000, cat#72971, CST), phospho-IRF3 antibody (1:1000, cat#29047, CST), phospho-NF-κB antibody (1:1000, cat#3033, CST), α-SMA antibody (1:1000, cat# 19245, CST), TAK1 antibody (1:1000, cat# ab109526 Abcam), GPX4 antibody (1:1000, cat# ab125066, Abcam), OGG1 antibody (1:1000, cat# 15125-1-AP, Proteintech), GAPDH antibody (1:1000, cat# 5174, CST), NRF2 antibody (1:1000, cat# 12721, CST), Lamin B1 antibody (1:1000, cat# 12586, CST), phospho-STAT1 antibody (1:1000, cat# 9167, CST), Arginase-1 (ARG-1) antibody (1:1000, cat# 93668, CST), NLRP3 antibody (1:1000, cat# 15101, CST) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature. The signals were detected using chemiluminescence horseradish peroxidase substrate (WBKL0100; Millipore Sigma) and an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. Proteins in Western blots were quantified in optical density units with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Statistical analysis

Two-group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, whereas for more than two groups, Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM and a value of p <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

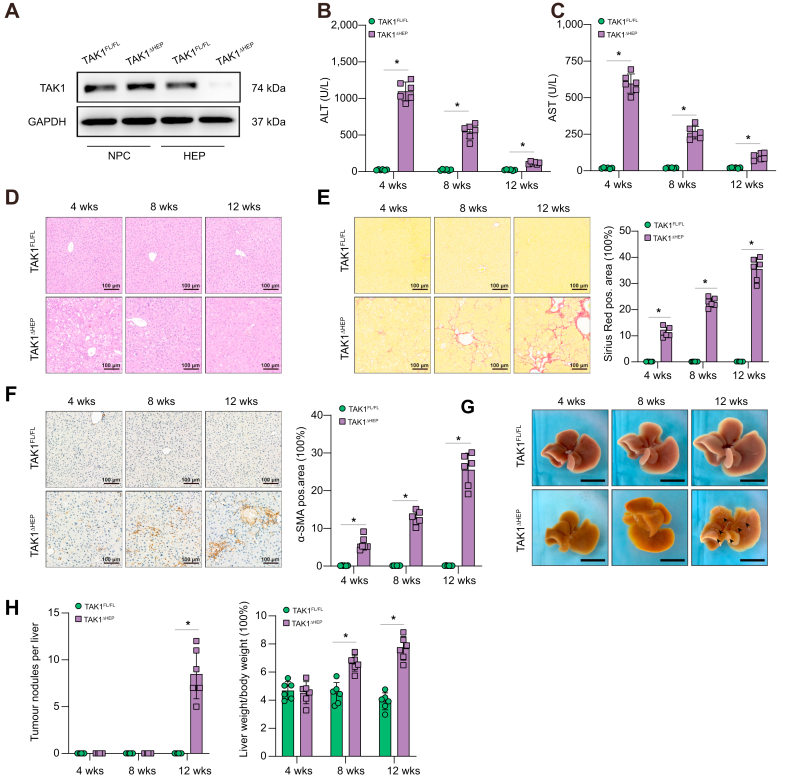

Deletion of TAK1 in hepatocytes caused the development of spontaneous liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma

Spontaneous liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma have been found previously in mice with TAK1 deficiency in hepatocytes.32 To study the precise role and mechanism of TAK1 in hepatocytes, TAK1ΔHEP mice were generated by crossing TAK1flox/flox mice with albumin-Cre mice. Protein expression of TAK1 in isolated hepatocytes and liver nonparenchymal cells confirmed the efficient and specific deletion of TAK1 in TAK1ΔHEP mice (Fig. 1A). Liver injury was found in TAK1ΔHEP mice early at 4 weeks of age and decreased by 8 and 12 weeks of age, as indicated by significantly increased serum ALT and AST levels (Fig. 1B and C) and liver pathologic examination (Fig. 1D). Liver fibrosis was detected in TAK1ΔHEP mice from 4 weeks of age, as shown by immunostaining with Sirius Red (Fig. 1E) and α-SMA (Fig. 1F). To further study the mechanism of hepatic TAK1 in affecting liver fibrosis, we conducted a macrophage-hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) co-culture experiment. Primary mouse HSCs were incubated with TAK1FL/FL or TAK1ΔHEP primary macrophage conditioned media (CM) for 24 h (Fig. S1A). The α-SMA protein expression indicated that CM from TAK1ΔHEP primary macrophage markedly promote the activation of HSCs (Fig. S1B). The gene expression of fibrotic markers (TGFβ-1, Colla1, Timp1) further confirmed these findings (Fig. S1C). Moreover, TAK1ΔHEP mice developed liver tumour nodules at 12 weeks old and had an increased liver-to-body weight ratio from 4 to 12 weeks old (Fig. 1G and H). These results confirmed that deletion of TAK1 in hepatocytes resulted in spontaneous development of liver injury, fibrosis, and HCC.

Fig. 1.

Deletion of TAK1 in hepatocytes caused the development of spontaneous liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

(A) Specific deletion of TAK1 in hepatocytes was confirmed by Western blot analysis. Liver function and histological staining were performed at three different time points. (B, C) Serum ALT and AST levels; n = 6/group. (D) Representative H&E staining, (E) Sirius Red staining, and (F) immunohistochemistry images of α-SMA in liver sections (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm, n = 6/group). (G) Representative liver images from different-week-old mice. Arrowheads denote tumours (scale bars = 1 cm). (H) Tumour nodules number and the ratio of liver-to-body weight. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ∗p <0.05 Mann–Whitney U test. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HEP, hepatocytes; NPC: nonparenchymal cells; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; w, weeks.

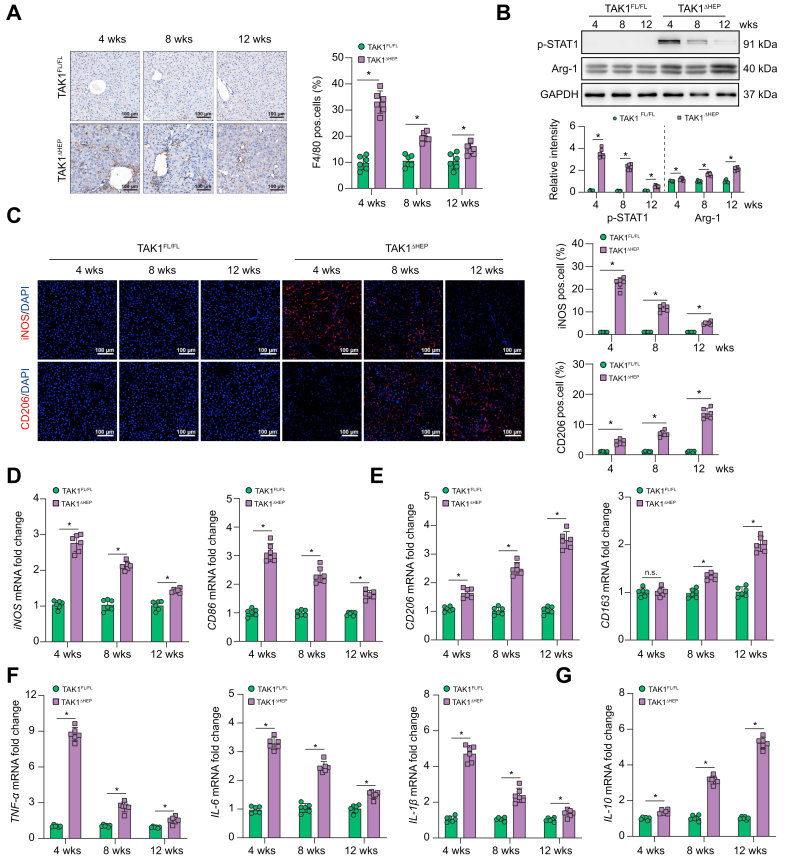

Hepatocyte-specific TAK1 deficiency regulated macrophage polarisation at different stages of liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis in TAK1ΔHEP mice

Macrophages play an important role in regulating various types of liver diseases. Therefore, we determined whether macrophages function in regulating liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis in TAK1ΔHEP mice. Significantly increased numbers of F4/80+ macrophages were detected in the livers of TAK1ΔHEP mice, peaking at 4 weeks and gradually decreasing by 8 and 12 weeks (Fig. 2A). Macrophage M1/M2 polarisation was evaluated at different time points by Western blotting of p-STAT1 and Arg-1 (Fig. 2B), immunostaining of iNOS and CD206 (Fig. 2C) and gene induction of iNOS, CD86, CD206, CD163 (Fig. 2D and E), and inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2F and G). The results showed that intrahepatic macrophages of TAK1ΔHEP mice were predominantly the M1 phenotype at 4 weeks and gradually shifted to the M2 phenotype at 8 and 12 weeks. These findings indicated that hepatocyte TAK1 deficiency promoted intrahepatic macrophage M1 polarisation during liver injury, M2 polarisation during fibrosis, and tumorigenesis.

Fig. 2.

Hepatocyte-specific TAK1 deficiency regulated macrophage polarisation at different stages.

Histological staining and RT-qPCR were performed using TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP samples from mice of different ages. (A) Representative immunohistochemistry staining of F4/80 in liver tissues (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm). (B) The protein levels of p-STAT1, Arg-1, and GAPDH in liver tissues. (C) Representative dual immunofluorescence staining for iNOS or CD206 with DAPI (200 × magnification, scale bars = 100 μm). (D, E) The gene expression of iNOS, CD86, CD206, and CD163 in liver tissues. (F, G) The gene expression of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-10. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ns, not significant, ∗p <0.05 Mann–Whitney U test. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; w, weeks.

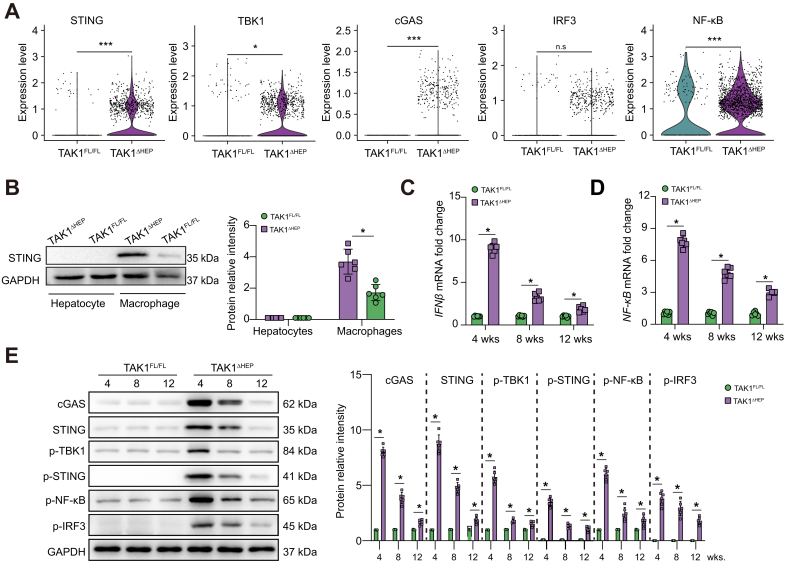

Macrophage STING signalling contributed to liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis in TAK1ΔHEP mice

Macrophage STING signalling has been implicated in various liver diseases.33 To investigate the changes in macrophage STING signalling affected by TAK1 depletion in hepatocytes, graph-based clustering with Seurat was performed on the single-cell RNA-Seq dataset (GSE148859). As STING and TBK1 are important components of the STING signalling pathway, we evaluated the expression of these two genes by bioinformatic analysis. Gene expression violin plots and feature plots of all clusters were constructed using the Seurat VlnPlot and featureplot function with the parameter pt. size = 0. The results showed that STING expression was predominantly observed in endothelial cells, macrophages and plasma cells, whereas TBK1 was predominantly expressed in endothelial cells, hepatocytes, macrophages, T cells, and NK cells in TAK1FL/FL mice (Fig. S2A and B). Moreover, TAK1ΔHEP mice showed higher expression levels of STING and TBK1 in macrophages (Fig. S2C and Fig. 3A), suggesting that TAK1 deficiency in hepatocytes upregulated STING signalling in macrophages. In addition, some other types of liver parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells, such as macrophages and endothelial cells, also demonstrated increased STING activation in TAK1-deficient mice. Interestingly, previous studies have shown the important role of STING signalling in regulating inflammation and cell death in endothelial cells.34,35 It would be interesting to investigate the role of STING signalling in other liver cells of TAK1ΔHEP mice in future studies.

Primary hepatocytes and macrophages were isolated to further check STING expression in both cell lines by Western blotting. The results showed that hepatocytes lacked STING expression compared with macrophages (Fig. 3B). The mRNA expression levels of interferon-beta (IFN-β) and NF-κB, two major target genes downstream of STING activation,36 showed a significant increase at 4 weeks and decreased at 8 and 12 weeks (Fig. 3C and D). Consistently, Western blotting results showed that the cGAS-STING signalling pathway was significantly activated in livers from TAK1ΔHEP mice at 4 weeks and decreased at 8 and 12 weeks (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Macrophage STING signalling contributed to liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis in TAK1ΔHEP mice.

(A) Violin plot from the single-cell RNA-Seq dataset (GSE148859) depicting higher expression of STING, TBK1, cGAS, IRF3, and NF-κB in the TAK1ΔHEPgroup, n.s., not significant, ∗p <0.05, ∗∗∗p <0.001 Wilcoxon rank sum test. (B) Western blot was performed to analyse the levels of STING in primary hepatocytes and macrophages isolated from TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice. (C, D) The gene expression of IFN-β and NF-κB in primary mouse macrophages. (E) The protein levels of cGAS-STING signalling in primary mouse macrophages. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ∗p <0.05, Mann–Whitney U test. cGAS, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IFN-β, interferon-beta; IRF3, IFN regulatory factor 3; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; TBK1, TANK-binding kinase 1; w, weeks.

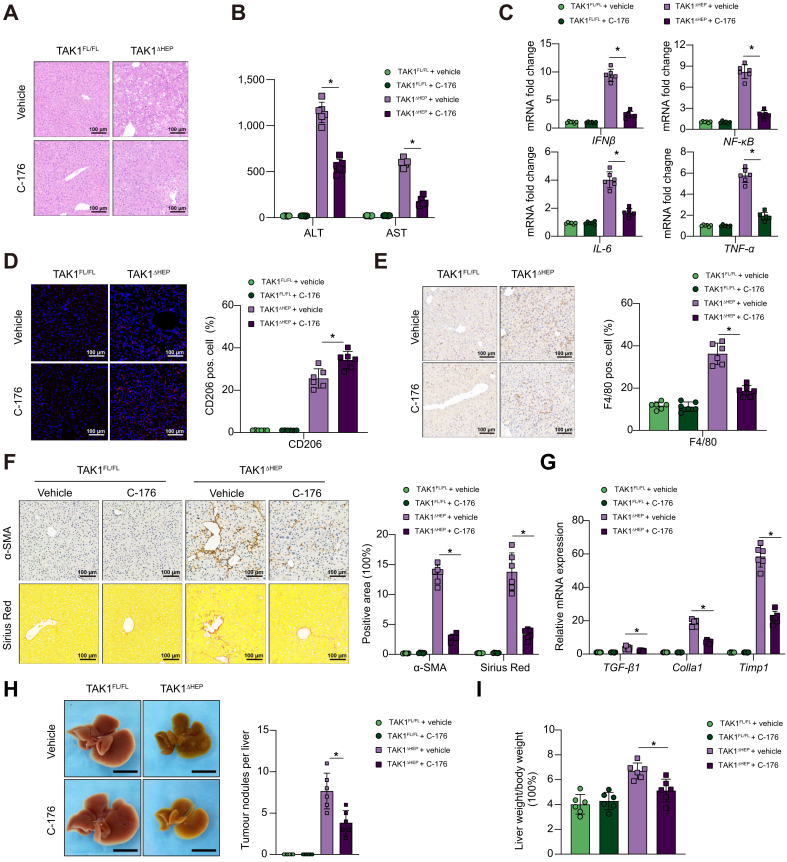

To further determine the essential role of macrophage STING signalling, the STING inhibitor C-176 was used to block STING activation. We previously found that STING regulated NLRP3 signalling in M1 macrophage polarisation.37,38 In vitro, STING inhibition by its antagonist promoted M2 polarisation but inhibited M1 polarisation of macrophages (Fig. S3A-D). In vivo, treatment with the STING inhibitor alleviated liver injury and inflammation at 4 weeks (Fig. 4A–E) and attenuated liver fibrosis at 8 weeks (Fig. 4F and G). In addition, in vivo STING inhibition resulted in reduced tumour burden and restored liver-to-body weight ratio in TAK1ΔHEP mice (Fig. 4H and I), which provided more evidence about the relationship between macrophage STING signalling and HCC progression. Together, these results suggested that macrophage STING signalling contributed to the disease progression of TAK1ΔHEP mice.

Fig. 4.

STING inhibitor attenuates hepatic inflammation, injury, and fibrosis in the early stage.

TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice were treated with i.p. injections of C-176 at a dose of 200 μmol or vehicle twice a week from 2 weeks of age. At 4 weeks of age, (A) liver and serum samples were collected for H&E staining (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm, n = 6/group), (B) ALT/AST measurement, (C) and RT-qPCR analysis for the expression of IFN-β, NF-κB, IL-6, and TNF-α. (D) Dual immunofluorescence staining for CD206 with DAPI (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm) and (E) immunohistochemistry staining of F4/80 in liver tissues (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm) to evaluate inflammation; By 8 weeks of age, (F) liver sections were stained for F4/80, α-SMA and Sirius Red (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm, n = 6/group) and (G) RT-qPCR analysis of TGF-β, Colla1, and Timp1. By 12 weeks of age, liver tissues were collected to assess tumour burden (H) and determine the liver-to-body weight ratio (I). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ∗p <0.05 Mann–Whitney U test. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; IFN-β, interferon-beta; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha.

TAK1 deficiency promoted ferroptosis of hepatocytes by inducing oxidative stress and disordered iron metabolism

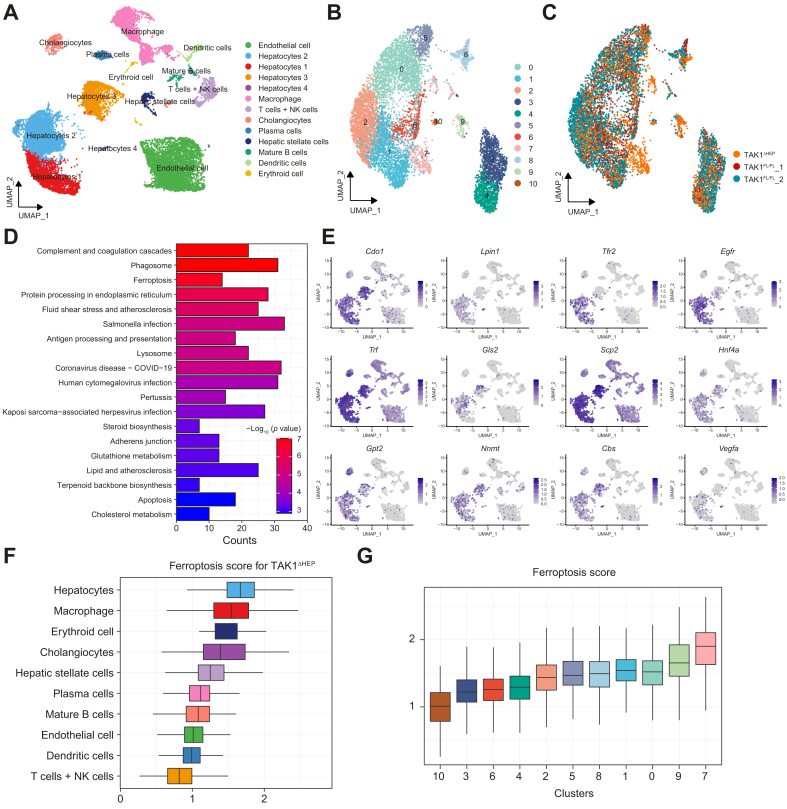

We next determined the type of hepatocellular cell death caused by TAK1 depletion. The viability of primary hepatocytes was checked, and results of CCK-8 and cellular supernatant lactate dehydrogenase level showed that TAK1 deficiency decreased hepatocytes viability (Fig. S4A and B). Graph-based clustering with Seurat on the single-cell RNA-Seq dataset (GSE148859) showed that all isolated cells were grouped into 13 distinct clusters (Fig. 5A). Based on the cell annotation in the study by Tan et al.,39 we reclustered hepatocytes from TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice into 11 clusters (Fig. 5B and C), of which the vast majority of hepatocytes in Cluster 7 belonged to TAK1ΔHEP mouse livers. As shown in Fig. 5D of the KEGG enrichment analysis, Cluster 7 differentially expressed genes (Table S3) were mainly enriched in the ferroptosis and apoptosis signalling pathways. However, no significant difference was found in the necroptosis signalling pathway. These results suggested that, in addition to apoptosis, ferroptosis would also be one of the important forms of hepatocyte cell death caused by TAK1 deficiency. FerrDb was used to analyse hepatocyte ferroptosis-related genes. Ferroptosis marker gene expression and distribution for each population in UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) plots showed that these genes were upregulated predominantly in hepatocytes compared with other cell types (Fig. 5E). In addition, we also evaluated ferroptosis scores in various types of hepatic cells and the highest scores were found in hepatocytes (Fig. 5F). Moreover, among the 11 clusters of hepatocytes, Cluster 7 hepatocytes had the highest ferroptosis scores (Fig. 5G).

Fig. 5.

ScRNA-seq data analysis of livers with TAK1 deficiency and TAK1 floxed mice.

(A) UMAP visualisation of single cells profiled in the dataset (from GEO at GSE148859). (B, C) Hepatocyte reclustering analysis. (D) Enrichment analysis of most DEGs of reclustered hepatocytes. (E) Representative gene expression and distribution of ferroptosis marker genes for each population in UMAP plots. (F, G) Ferroptosis geneset enrichment scores were performed for all cell types and all reclusters of hepatocytes. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; NK cells, natural killer cells; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

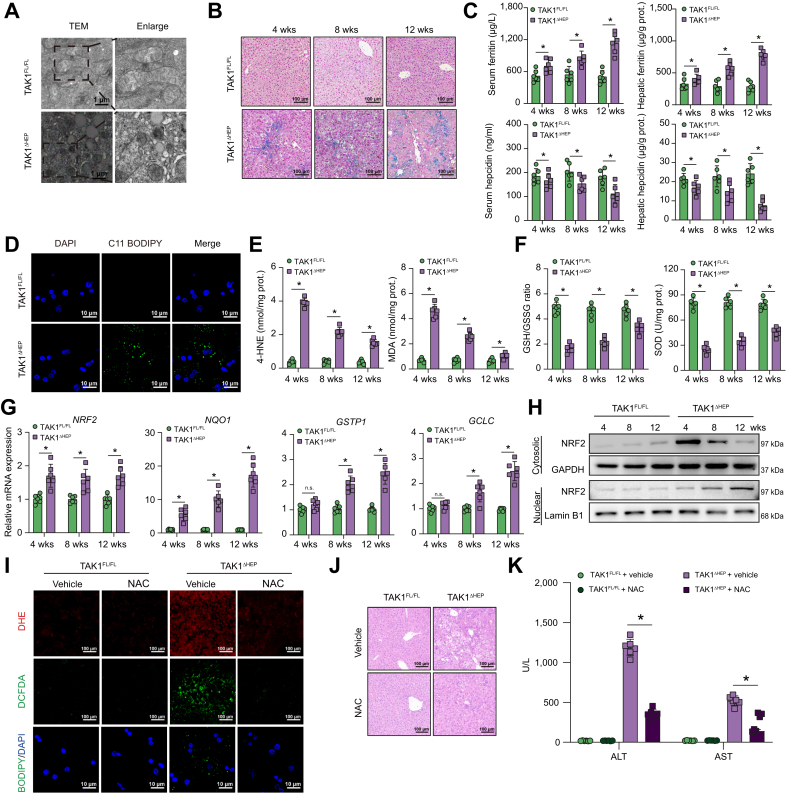

Moreover, KEGG pathway analysis showed that some ROS-related pathways were involved in TAK1-deficient hepatocytes, including glutathione metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, and fatty acid metabolism. Features of ferroptosis, including mitochondrial volume reduction, increased bilayer membrane density, and rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane, were found by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in TAK1-deficient hepatocytes (Fig. 6A). Iron metabolism disorders is also an important characteristic of ferroptosis. Increased hepatic iron accumulation was found in livers from TAK1ΔHEP mice, as shown by Prussian Blue staining (Fig. 6B). Elevated levels of ferritin but decreased levels of hepcidin in both liver tissues and serum were found in TAK1ΔHEP mice (Fig. 6C). These results further suggested dysregulated iron metabolism in TAK1ΔHEP mice. We further evaluated liver injury and inflammation in mice treated with a high-iron diet or normal diet. The results showed that treatment with an iron-rich diet increased liver injury and inflammation in TAK1ΔHEP mice, as shown by serum ALT and AST levels and H&E and F4/80 staining of liver tissues (Fig. S5A–C).

Fig. 6.

TAK1 deficiency promoted ferroptosis of hepatocytes by inducing oxidative stress.

(A) Representative TEM images from liver tissues (4,800× magnification, scale bars = 1 μm, n = 6 per group). (B) Perls’ Prussian Blue staining of liver samples at different times. (C) Serum and hepatic levels of ferritin and hepcidin. (D) Representative confocal images of primary hepatocytes labelled with C11-BODIPY and DAPI (200× magnification, scale bars = 25 μm). (E, F) Hepatic MDA, 4-HNE, and SOD levels and GSH/GSSG ratio at different times. (G) The expression levels of gene NRF2, NQO1, GSTP1, and GCLC in liver tissue, n = 6 mice/group. (H) Western blot was performed to analyse the levels of NRF2 in cytosolic and nuclear of primary hepatocytes of TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice. TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice were treated with i.p. injections of NAC (150 mg/kg/day) or vehicle from 2 weeks of age to 4 weeks of age, (I) representative immunofluorescence staining images of DHE and DCFDA in liver sections (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm) and primary hepatocytes labelled with C11-BODIPY and DAPI (200× magnification, scale bars = 25 μm). (J) Representative H&E staining images in liver sections. (K) Serum ALT and AST levels. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ∗p <0.05 Mann–Whitney U test. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DCFDA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; MDA, malondialdehyde; NAC, N-Acetyl cysteine; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; w, weeks.

TAK1-deficient hepatocytes also demonstrated accumulation of lipid ROS products, which were labelled with the fluorescent probe C11-BODIPY (581/591) (Fig. 6D). Increased lipid peroxidation and decreased antioxidant activity were found in livers from TAK1ΔHEP mice, as shown by MDA, 4-HNE, and SOD expression and the GSH/GSSG ratio (Fig. 6E and F). Transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) is a key player in antioxidant defence. NRF2 and its responsive genes, such as NQO1, GSTP1, and GCLC, were all upregulated in TAK1-deficient livers, suggesting enhanced NRF2 activity (Fig. 6G). The NRF2 nuclear translocation was also evaluated by Western blotting. Protein levels of NRF2 were gradually increased in nuclear but decreased in cytoplasm over the different time points, indicating sustained translocation of NRF2 to the nucleus in TAK1-deficient hepatocytes (Fig. 6H). As the role of GPX4 in ferroptosis is widely described, we measured the expression of GPX4 protein. Results showed that GPX4 expression was increased in TAK1-deficient liver tissue (Fig. S6A), possibly as a result of a compensatory antioxidant response against TAK1-deficiency-induced imbalance ROS. Moreover, ROS inhibition by NAC effectively suppressed oxidative stress in hepatocytes, ferroptosis, and liver injury (Fig. 6I–K). These results suggested that TAK1 deficiency promoted ferroptosis of hepatocytes by inducing oxidative stress and disordered iron metabolism.

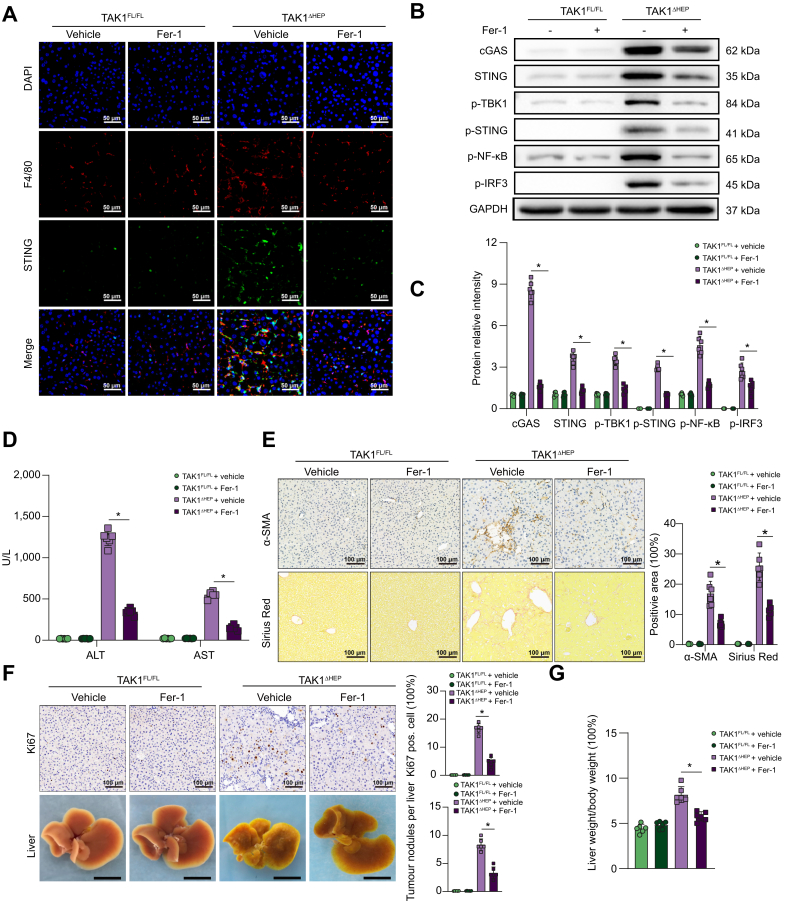

Inhibition of hepatocellular ferroptosis decreased macrophage STING activation and suppressed liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis in TAK1ΔHEP mice

Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), a specific inhibitor of ferroptosis, was used to evaluate the role of ferroptosis in regulating liver injury, fibrosis, and tumour development caused by TAK1 deficiency. Consequently, suppression of hepatocellular ferroptosis significantly inhibited the activation of macrophage STING signalling, as evidenced by fewer F4/80 and STING double-positive cells (Fig. 7A) and decreased protein levels of cGAS-STING signal pathway (Fig. 7B and C). Moreover, suppression of ferroptosis by Fer-1 effectively decreased liver injury (Fig. 7D) and liver fibrosis (Fig. 7E). TAK1ΔHEP mice treated with Fer-1 also showed decreased cell proliferation and a reduced tumour burden (Fig. 7F and G). Overall, we found that TAK1 depletion in hepatocytes promoted macrophage STING activation to facilitate liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis by inducing hepatocellular ferroptosis, suggesting a therapeutic role for the suppression of macrophage STING activation or hepatocellular ferroptosis in liver disease.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of hepatocellular ferroptosis decreased macrophage STING activation and suppressed liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis in TAK1ΔHEP mice.

TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice were treated with Fer-1 (5 mg/kg/day) or vehicle from 2 weeks of age. Mice were sacrificed at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of age. At 4 weeks of age, (A) representative immunofluorescence images from liver tissues stained with STING and F4/80 (400 × magnification, scale bars = 50 μm); (B, C) Western blot analysis of cGAS-STING signalling in primary macrophages; (D) Serum ALT and AST levels. At 8 weeks of age, liver sections were stained for (E) α-SMA and Sirius Red by immunohistochemistry (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm). At 12 weeks of age, (F) tumorigenesis was evaluated by Ki67 immunostaining in liver sections (200 × magnification, scale bars = 100 μm), tumour nodules of livers (scale bars = 1 cm), and liver-to-body weight ratio (G). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ∗p <0.05 Mann–Whitney U test. α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; cGAS, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IRF3, IFN regulatory factor 3; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; TBK1,TANK-binding kinase 1.

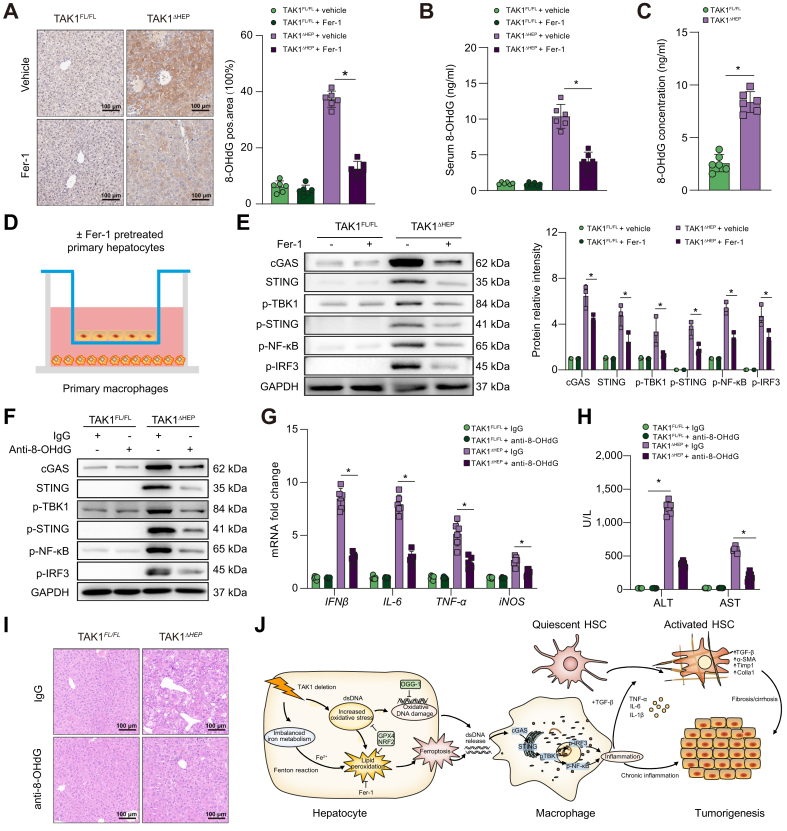

Hepatocyte ferroptosis promoted oxidative DNA damage to activate macrophage cGAS-STING signalling

To investigate whether macrophage STING activation was caused by oxidative DNA damage from injured/damaged hepatocytes, we measured the expression of 8-OHdG, a marker of oxidative DNA damage, in both livers and serum from TAK1ΔHEP mice. The results showed that the levels of hepatic and serum 8-OHdG were suppressed by Fer-1 treatment (Fig. 8A and B). Additionally, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 (OGG1) expression was increased in TAK1 deficiency liver tissue (Fig. S6A), which is the major DNA glycosylase in the repairment of damaged DNA bases. Moreover, 8-OHdG levels of cellular supernatant from TAK1-deleted hepatocytes had higher level of oxidative damaged DNA release (Fig. 8C). Isolated primary hepatocytes from TAK1FL/FL or TAK1ΔHEP mice were pretreated with or without Fer-1 and then co-cultured with primary liver macrophages for 12 h (Fig. 8D). As shown in Fig. 8E, Fer-1 pretreatment significantly suppressed the activation of cGAS-STING signalling in primary liver macrophages co-cultured with TAK1-deficient hepatocytes. Moreover, in vivo treatment with an anti-8-OHG antibody effectively suppressed macrophage cGAS-STING signal activation (Fig. 8F) and decreased the gene expression of IFN-β, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and iNOS (Fig. 8G) in TAK1ΔHEP mice. In addition, anti-8-OHdG-treated TAK1ΔHEP mice also showed attenuated liver injury (Fig. 8H and I). Taken together, these findings indicated that oxidative DNA damage caused by hepatocyte ferroptosis promoted macrophage cGAS-STING activation signalling and intrahepatic inflammation (Fig. 8J).

Fig. 8.

Hepatocyte ferroptosis promoted oxidative DNA damage to activate macrophage cGAS-STING signalling.

Mice were treated with Fer-1 (5 mg/kg/day, from 2 weeks to 4 weeks of age) or vehicle, (A) immunohistochemical detection of 8-OHdG in liver samples (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm), and (B) serum levels of 8-OHdG. (C) Level of 8-OHdG in the culture media of primary hepatocytes. (D) Isolated primary hepatocytes from TAK1FL/FL or TAK1ΔHEP mice were pretreated with or without Fer-1 (2 μM) for 6 h and then co-cultured with primary macrophages for 12 h. Primary macrophages were harvested to perform Western blots for (E) cGAS-STING signal pathway. TAK1FL/FL and TAK1ΔHEP mice were i.p. injected with control IgG or anti-8-OHG antibody from 2 weeks to 4 weeks of age, primary liver macrophages were isolated for (F) Western blots for cGAS-STING signal pathway and (G) RT-qPCR analysis was performed for IFN-β, IL-6, TNF-α and iNOS gene expression, (H) serum ALT and AST levels, (I) representative H&E staining images in liver sections (200× magnification, scale bars = 100 μm). (J) Schematic illustration of how TAK1 deficiency induce hepatocyte ferroptosis to promote liver tumorigenesis via macrophage cGAS-STING signalling. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ∗p <0.05 Mann–Whitney U test. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; cGAS, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1; HSC, hepatic stellate cells; IFN-β, interferon-beta; IRF3, IFN regulatory factor 3; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; OGG-1, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1; 8-OHdG, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; TBK1, TANK-binding kinase 1; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha.

Macrophage STING expression in patients with ALI, fibrosis, and HCC

Finally, we evaluated macrophage STING activation in patients with ALI, fibrosis, and HCC. Liver tissues from patients with ALI, fibrosis, or HCC, and normal controls were collected, and STING expression was analysed. Significantly increased protein levels of STING were found in liver tissues from patients with ALI, fibrosis, and HCC (Fig. S7A). Moreover, positive STING staining was observed in CD68-positive macrophages (Fig. S7B). These data suggest the critical role of macrophage STING signalling in the pathogenesis of ALI, fibrosis, and HCC in humans.

Discussion

The interplay between hepatic parenchymal cell death and macrophage-related inflammation plays a vital role in various liver diseases.40 However, the underlying mechanism by which hepatocellular ferroptosis regulates macrophage STING signalling during liver injury, fibrosis, and tumorigenesis remains unclear. Here, we found that TAK1 deficiency promoted hepatocellular ferroptosis, which facilitated macrophage STING activation and subsequent liver injury and inflammation. Liver injury and fibrosis were attenuated by suppression of STING activation in macrophages. Inhibition of ferroptosis suppressed liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocarcinogenesis.

Emerging evidence suggests that TAK1 signalling plays a crucial role in human liver cancers. Increased TAK1 expression in human HCCs was associated with vascular invasion and poor overall survival.26 Another study revealed a correlation between high TAK1 expression and low GRAMD4 expression in HCC patients. Mechanistically, GRAMD4 inhibited HCC migration, invasion, and metastasis by promoting TAK1 degradation.25 Recent research has demonstrated the clinical relevance of TAK1 in promoting HCC and sorafenib resistance. Combining TAK1 inhibitors with sorafenib inhibited the growth of sorafenib-resistant HCCLM3 xenografts in mouse models.41

In contrast, numerous studies have documented spontaneous liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis in mice with hepatocyte-specific deletion of TAK1,27,32,39,42 which seemed to contradict the findings in human liver cancers. Studies with mouse models of hepatocyte-specific TAK1 deficiency focused primarily on the role of TAK1 in regulating tumorigenesis, whereas human samples were utilised to investigate the effects of TAK1 on regulating progression, metastasis, and therapeutic response. In addition, TAK1A but not TAK1B functioned as a tumour cell migratory mediator, revealing an isoform-specific role of TAK1.26 Taken together, TAK1 is theorised to have potential roles that differ by stage. Although TAK1 depletion can promote the initial development of chronic liver injury and tumorigenesis, TAK1 inhibition exerts a therapeutic effect in tumour treatment. Therefore, further basic and clinical research are needed to determine the precise context dependent, cell type-dependent and isoform-specific role of TAK1 signalling in regulating liver tumour initiation, progression, metastasis, and therapeutic response.

Oxidative stress is an imbalance between the production of free radicals and antioxidants and is implicated in many human diseases. Overproduction of ROS is a constant threat to cytosolic DNA, both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA; when left unrepaired, this damage also seems to be involved in mutagenicity and cancer promotion.43 Oxidative DNA damage has been demonstrated to result in cytotoxic effects and is implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammation-associated diseases.44 It was found that the levels of markers of lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage, such as HNE and 8-OHdG, are correlated with the severity of necroinflammation and fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.45 Increased hepatic oxidative DNA damage was found in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis who developed hepatocellular carcinoma, and 8-OHdG content in liver tissue may serve as a marker of oxidative stress and could be a particularly useful predictor of hepatocarcinogenesis.46 Additionally, patients with high serum alpha-fetoprotein and a high degree of ballooning showed accumulation of oxidative DNA damage that could be responsible for hepatocarcinogenesis.47

Studies have shown the critical role of TAK1 in regulating cellular redox homeostasis. TAK1 deficiency induced increase of ROS and cell death in keratinocytes, intestinal epithelial cells, and bone marrow-derived macrophages.[48], [49], [50] In the present study, we found that TAK1 deficiency caused accumulation of ROS in hepatocytes, contributing to hepatocytes ferroptosis. Different types of cell death can cause different extents of immune and inflammatory responses. In contrast to apoptosis, ferroptosis is a form of inflammatory cell death caused by the release of DAMPs, such as HMGB1 and mtDNA, or lipid oxidation products.3 Ferroptosis-associated inflammation plays a critical role in modulating various types of liver diseases. Inhibition of iron overload-induced ferroptosis attenuated liver injury and fibrosis.51 Ferroptosis inhibition protected hepatocytes from necrotic death and suppressed the initial inflammatory reaction in steatohepatitis.52 The ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 rescued liver fibrosis induced by either high dietary iron or carbon tetrachloride injections.53 Ferroptosis has been implicated in the development and therapeutic responses of various types of tumours.5 Several drugs that are already in clinical use, such as sorafenib, can induce ferroptosis in different solid tumour cells.54 However, ferroptotic damage could also promote tumour growth by triggering inflammation-associated immunosuppression in the tumour microenvironment. KRASG12D, a DAMP released from ferroptotic cancer cells, can be taken up by macrophages to promote M2 polarisation and subsequent pancreatic tumour growth.55

Increasing evidence has shown the interplay between ferroptosis and STING signalling.56 DAMPs released from ferroptotic cells activated cGAS-STING signalling. Ferroptosis promoted 8-OHG release and thus activated the STING-dependent DNA sensor pathway to promote pancreatic tumorigenesis.57 Another study also found that DNA damage-induced STING activation promoted autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells.58 STING activation produces excessive lipid peroxidation, leading to macrophage cell death during intestinal ischemic injury.59 In the present study, macrophage STING was continuously activated, although its degree of activation gradually decreased at the late stage of liver fibrosis and tumour development. Interfering with STING signalling pathway has shown promise in the treatment of inflammatory, autoimmune, and cancerous diseases.60 STING inhibitors were developed by inhibiting the binding of cGAMP to STING or the post-translational modification of STING.61 Currently, several STING antagonist programs are undergoing pre-clinical research and the drug discovery procedure, but none have yet reached the clinical evaluation stage.8,62,63 There are still many challenges that need to be overcome to fully realise the therapeutic potential of targeting the STING pathway, such as, patient heterogeneity, specificity, and efficacy of the inhibitors, and the complex interactions between the STING signalling pathway and other cellular pathways. Accumulating evidence indicates that ferroptosis and STING interact in both human diseases and mouse models. In patients with colon cancer, STING-related genes were interrelated with ferroptosis at the levels of genes and proteins.64 Ferroptosis promoted 8-OHG release and thus activated the STING-dependent DNA sensor pathway to promote pancreatic tumorigenesis.57 The inhibition of ferroptosis ameliorated acute liver damage by inhibiting STING activation.65 However, STING signalling plays a crucial role in numerous forms of cell death, including ferroptosis.66,67 Moreover, co-immunoprecipitation studies demonstrated that STING could interact with the TAK1 protein, indicating an interaction between STING and TAK1.68 However, the relationship between STING expression and TAK1 expression in human diseases remains unclear.

In conclusion, these findings reveal the critical interplay between hepatocyte ferroptosis and macrophage STING activation. Hepatocellular ferroptosis promotes the activation of macrophage STING signalling, which in turn facilitates the development of spontaneous liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Our study uncovered a novel mechanism of STING activation and suggests a new approach for modulating ferroptosis- and STING-dependent immunopathologies. Strategies targeting macrophage STING signalling or hepatocellular ferroptosis could be beneficial in the treatment of liver injury, fibrosis, and tumours.

Financial support

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071798, 81971495) and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (No. 2019-I2M-5-035).

Authors’ contributions

Drafted the manuscript: WS, WG. Conducted the experiments and analysed the data: WS, WG, RZ, QW, L. Li, QB, ZX, ZL, MW. Participated in the research design: WS, WG, HZ, XW, L. Lu. Revised the manuscript: YZ, GW, HZ, XW. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100695.

Contributor Information

Yaqing Zhu, Email: doctorzhuyq@163.com.

Guoping Wu, Email: drgpwu@aliyun.com.

Haoming Zhou, Email: hmzhou@njmu.edu.cn.

Xun Wang, Email: wangxun@njmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Jiang X., Stockwell B.R., Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cel Biol. 2021;22:266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Y., Zhang S., Gong X., Tam S., Xiao D., Liu S., et al. The epigenetic regulators and metabolic changes in ferroptosis-associated cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:39. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01157-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang D., Chen X., Kang R., Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021;31:107–125. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X., Zeh H.J., Kang R., Kroemer G., Tang D. Cell death in pancreatic cancer: from pathogenesis to therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:804–823. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X., Kang R., Kroemer G., Tang D. Broadening horizons: the role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:280–296. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-00462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan C., Cunningham-Bussel A. Beyond oxidative stress: an immunologist’s guide to reactive oxygen species. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang D., Minikes A.M., Jiang X. Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Mol Cel. 2022;82:2215–2227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decout A., Katz J.D., Venkatraman S., Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:548–569. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon J., Bakhoum S.F. The cytosolic DNA-sensing cGAS-STING pathway in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:26–39. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus A., Mao A.J., Lensink-Vasan M., Wang L., Vance R.E., Raulet D.H. Tumor-Derived cGAMP triggers a STING-mediated interferon response in non-tumor cells to activate the NK cell response. Immunity. 2018;49:754–763.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbie D.A., Tamayo P., Boehm J.S., Kim S.Y., Moody S.E., Dunn I.F., et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature. 2009;462:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T., Chen Z.J. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1287–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed O., Robinson M.W., O'Farrelly C. Inflammatory processes in the liver: divergent roles in homeostasis and pathology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:1375–1386. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00639-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal B.B., Vijayalekshmi R.V., Sung B. Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:425–430. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shim J.H., Xiao C., Paschal A.E., Bailey S.T., Rao P., Hayden M.S., et al. TAK1, but not TAB1 or TAB2, plays an essential role in multiple signaling pathways in vivo. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2668–2681. doi: 10.1101/gad.1360605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu W., Chang B.L., Cramer S., Koty P.P., Li T., Sun J., et al. Deletion of a small consensus region at 6q15, including the MAP3K7 gene, is significantly associated with high-grade prostate cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5028–5033. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamothe B., Lai Y., Hur L., Orozco N.M., Wang J., Campos A.D., et al. Deletion of TAK1 in the myeloid lineage results in the spontaneous development of myelomonocytic leukemia in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu M., Shi L., Cimic A., Romero L., Sui G., Lees C.J., et al. Suppression of Tak1 promotes prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2833–2843. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roh Y.S., Song J., Seki E. TAK1 regulates hepatic cell survival and carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:185–194. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0931-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordas Dos Santos D.M., Eilers J., Sosa Vizcaino A., Orlova E., Zimmermann M., Stanulla M., et al. MAP3K7 is recurrently deleted in pediatric T-lymphoblastic leukemia and affects cell proliferation independently of NF-kappaB. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:663. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen J., Hu Y., Luo K.J., Yang H., Zhang S.S., Fu J.H. Positive transforming growth factor-beta activated kinase-1 expression has an unfavorable impact on survival in T3N1-3M0 esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin P., Niu W., Peng C., Zhang Z., Niu J. The role of TAK1 expression in thyroid cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:14449–14456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y., Qiu Y., Tang M., Wu Z., Hu W., Chen C. Expression and function of transforming growth factor-beta-activated protein kinase 1 in gastric cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:3103–3110. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao P., Wang S., Jiang J., Liu H., Zhu X., Zhao N., et al. TIPE2 sensitizes osteosarcoma cells to cis-platin by down-regulating MDR1 via the TAK1- NF-kappaB and - AP-1 pathways. Mol Immunol. 2018;101:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge Q.Y., Chen J., Li G.X., Tan X.L., Song J., Ning D., et al. GRAMD4 inhibits tumour metastasis by recruiting the E3 ligase ITCH to target TAK1 for degradation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:e635. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridder D.A., Urbansky L.L., Witzel H.R., Schindeldecker M., Weinmann A., Berndt K., et al. Transforming growth factor-beta activated kinase 1 (Tak1) is activated in hepatocellular carcinoma, mediates tumor progression, and predicts unfavorable outcome. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:430. doi: 10.3390/cancers14020430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inokuchi-Shimizu S., Park E.J., Roh Y.S., Yang L., Zhang B., Song J., et al. TAK1-mediated autophagy and fatty acid oxidation prevent hepatosteatosis and tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3566–3578. doi: 10.1172/JCI74068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malireddi R.K.S., Gurung P., Kesavardhana S., Samir P., Burton A., Mummareddy H., et al. Innate immune priming in the absence of TAK1 drives RIPK1 kinase activity-independent pyroptosis, apoptosis, necroptosis, and inflammatory disease. J Exp Med. 2020:217. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orning P., Weng D., Starheim K., Ratner D., Best Z., Lee B., et al. Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin D and cell death. Science. 2018;362:1064–1069. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou N., Bao J. FerrDb: a manually curated resource for regulators and markers of ferroptosis and ferroptosis-disease associations. Database (Oxfofd) 2020:2020. doi: 10.1093/database/baaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeTomaso D., Jones M.G., Subramaniam M., Ashuach T., Ye C.J., Yosef N. Functional interpretation of single cell similarity maps. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4376. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inokuchi S., Aoyama T., Miura K., Osterreicher C.H., Kodama Y., Miyai K., et al. Disruption of TAK1 in hepatocytes causes hepatic injury, inflammation, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:844–849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909781107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C., Yang R.X., Xu H.G. STING and liver disease. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:704–712. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01803-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao Y., Luo W., Zhang L., Wu W., Yuan L., Xu H., et al. STING-IRF3 triggers endothelial inflammation in response to free fatty acid-induced mitochondrial damage in diet-induced obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:920–929. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domizio J.D., Gulen M.F., Saidoune F., Thacker V.V., Yatim A., Sharma K., et al. The cGAS-STING pathway drives type I IFN immunopathology in COVID-19. Nature. 2022;603:145–151. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04421-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopfner K.P., Hornung V. Molecular mechanisms and cellular functions of cGAS-STING signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cel Biol. 2020;21:501–521. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong W., Rao Z., Rao J., Han G., Wang P., Jiang T., et al. Aging aggravated liver ischemia and reperfusion injury by promoting STING-mediated NLRP3 activation in macrophages. Aging Cell. 2020;19 doi: 10.1111/acel.13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Q., Zhou H., Bu Q., Wei S., Li L., Zhou J., et al. Role of XBP1 in regulating the progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2022;77:312–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan S., Zhao J., Sun Z., Cao S., Niu K., Zhong Y., et al. Hepatocyte-specific TAK1 deficiency drives RIPK1 kinase-dependent inflammation to promote liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:14231–14242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005353117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luedde T., Kaplowitz N., Schwabe R.F. Cell death and cell death responses in liver disease: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:765–783.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia S., Ji L., Tao L., Pan Y., Lin Z., Wan Z., et al. TAK1 is a novel target in hepatocellular carcinoma and contributes to sorafenib resistance. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12:1121–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang L., Inokuchi S., Roh Y.S., Song J., Loomba R., Park E.J., et al. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in hepatocytes promotes hepatic fibrosis and carcinogenesis in mice with hepatocyte-specific deletion of TAK1. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1042–1054.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mao P., Wyrick J.J. Organization of DNA damage, excision repair, and mutagenesis in chromatin: a genomic perspective. DNA Repair (Amst) 2019;81 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawanishi S., Ohnishi S., Ma N., Hiraku Y., Murata M. Crosstalk between DNA damage and inflammation in the multiple steps of carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1808. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takaki A., Kawai D., Yamamoto K. Multiple hits, including oxidative stress, as pathogenesis and treatment target in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:20704–20728. doi: 10.3390/ijms141020704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka S., Miyanishi K., Kobune M., Kawano Y., Hoki T., Kubo T., et al. Increased hepatic oxidative DNA damage in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis who develop hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1249–1258. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0739-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishida N., Yada N., Hagiwara S., Sakurai T., Kitano M., Kudo M. Unique features associated with hepatic oxidative DNA damage and DNA methylation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1646–1653. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Omori E., Morioka S., Matsumoto K., Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 regulates reactive oxygen species and cell death in keratinocytes, which is essential for skin integrity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26161–26168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804513200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kajino-Sakamoto R., Omori E., Nighot P.K., Blikslager A.T., Matsumoto K., Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TGF-beta-activated kinase 1 signaling maintains intestinal integrity by preventing accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the intestinal epithelium. J Immunol. 2010;185:4729–4737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez-Perez W., Sai K., Sakamachi Y., Parsons C., Kathariou S., Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 inhibition elicits mitochondrial ROS to block intracellular bacterial colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023647118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu A., Feng B., Yu J., Yan L., Che L., Zhuo Y., et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 attenuates iron overload-induced liver injury and fibrosis by inhibiting ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2021;46 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsurusaki S., Tsuchiya Y., Koumura T., Nakasone M., Sakamoto T., Matsuoka M., et al. Hepatic ferroptosis plays an important role as the trigger for initiating inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:449. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1678-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu Y., Jiang L., Wang H., Shen Z., Cheng Q., Zhang P., et al. Hepatic transferrin plays a role in systemic iron homeostasis and liver ferroptosis. Blood. 2020;136:726–739. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lachaier E., Louandre C., Godin C., Saidak Z., Baert M., Diouf M., et al. Sorafenib induces ferroptosis in human cancer cell lines originating from different solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:6417–6422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dai E., Han L., Liu J., Xie Y., Kroemer G., Klionsky D.J., et al. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis drives tumor-associated macrophage polarization via release and uptake of oncogenic KRAS protein. Autophagy. 2020;16:2069–2083. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1714209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang R., Kang R., Tang D. The STING1 network regulates autophagy and cell death. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:208. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00613-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dai E., Han L., Liu J., Xie Y., Zeh H.J., Kang R., et al. Ferroptotic damage promotes pancreatic tumorigenesis through a TMEM173/STING-dependent DNA sensor pathway. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6339. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuang F., Liu J., Li C., Kang R., Tang D. Cathepsin B is a mediator of organelle-specific initiation of ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;533:1464–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu J., Liu Q., Zhang X., Wu X., Zhao Y., Ren J. STING-dependent induction of lipid peroxidation mediates intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;163:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guerini D. STING agonists/antagonists: their potential as therapeutics and future developments. Cells. 2022;11:1159. doi: 10.3390/cells11071159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feng X., Liu D., Li Z., Bian J. Bioactive modulators targeting STING adaptor in cGAS-STING pathway. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sheridan C. Drug developers switch gears to inhibit STING. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:199–201. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0060-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding C., Song Z., Shen A., Chen T., Zhang A. Small molecules targeting the innate immune cGAS‒STING‒TBK1 signaling pathway. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2272–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nie J., Shan D., Li S., Zhang S., Zi X., Xing F., et al. A novel ferroptosis related gene signature for prognosis prediction in patients with colon cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.654076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Y., Yu P., Fu W., Wang S., Zhao W., Ma Y., et al. Ginsenoside Rd inhibited ferroptosis to alleviate CCl(4)-induced acute liver injury in mice via cGAS/STING pathway. Am J Chin Med. 2022;28:1–15. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X23500064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li C., Liu J., Hou W., Kang R., Tang D. STING1 promotes ferroptosis through MFN1/2-dependent mitochondrial fusion. Front Cel Dev Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.698679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu X., Zhang H., Zhang Q., Yao X., Ni W., Zhou K. Emerging role of STING signalling in CNS injury: inflammation, autophagy, necroptosis, ferroptosis and pyroptosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:242. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02602-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Falco F., Cutarelli A., Catoi A.F., Uberti B.D., Cuccaro B., Roperto S. Bovine delta papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein negatively regulates the cGAS-STING signaling pathway in cattle in a spontaneous model of viral disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.937736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.