Highlights

-

•

Pickering emulsions stabilized by tea water-insoluble protein nanoparticles (TWIPNPEs) could encapsulate resveratrol.

-

•

Resveratrol was located in a hydrophobic environment of emulsion droplets internal.

-

•

Reducing degradation of resveratrol under UV irradiation attributed to encapsulation of TWIPNPEs.

-

•

Encapsulation efficiency of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs reached more than 85%.

-

•

TWIPNPEs enhanced the bioavailability of resveratrol in the simulated digestion.

Keywords: Tea protein, Pickering emulsions, Resveratrol, Encapsulation, Bioavailability

Abstract

This study focused on the characteristics and in vitro digestion of resveratrol encapsulated in Pickering emulsions stabilized by tea water-insoluble protein nanoparticles (TWINs). The absolute value of zeta potential of Pickering emulsions stabilized by TWIPNs (TWIPNPEs) encapsulating resveratrol was above 40 mV. Resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs was located at a hydrophobic environment of emulsion droplets. Additionally, the encapsulation efficiency (EE) of TWIPNPEs at TWIPN concentrations of 3.0% and 4.0% was above 85%. The resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs at a TWIPN concentration of 4.0% was still greater than 80% after UV irradiation to reduce the susceptibility of resveratrol for photodegradation. Moreover, the bioavailability of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs was improved in the simulated in vitro digestion. The bioavailability of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs in the simulated system was two times higher than unencapsulated resveratrol. This research could be useful for the encapsulation and application of nutraceuticals like resveratrol based on TWIPNPEs.

1. Introduction

Improving the stability and bioavailability of functional ingredients is crucial to the research and development of functional foods. Encapsulation systems such as nanoparticles and emulsions are frequently used to encapsulate functional components. Emulsions can stabilize poorly stable functional components such as polyunsaturated fatty acids, polyphenols, and flavonoids (Đorđević et al., 2015). Aside from the characteristics of the functional components, many other factors, including the oil phase, emulsion droplet size, and external factors, can affect the encapsulation and delivery of functional components.

Emulsions can be used in the food industry and other related fields depending on the differences in their physical and chemical properties. Due to their safety, non-toxicity, and ease of degradation, food-grade Pickering emulsions have received a large amount of interest lately (Xiao, Li & Huang, 2016). Pickering emulsions can be used for the encapsulation and delivery of antibacterial, antioxidant, and other functional substances, especially some functional components that are sensitive to temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and light (Fu et al., 2019). Due to their short gastrointestinal residence times, poor gastrointestinal tract stability, and strict environmental requirements, unencapsulated functional components have a low bioavailability after digestion (Faraji, McClements & Decker, 2004). Formulating food-grade Pickering emulsions to encapsulate functional components is an effective method to solve the aforementioned challenges. Stable Pickering emulsions have sparked interest in areas such as plant protein, cellulose, and polysaccharide research. Plant proteins in particular offer excellent nutritional, safety, and emulsifying properties, making them the ideal delivery system for encapsulating and delivering functional components (Patel, 2018). Consequently, Pickering emulsions that use plant proteins to encapsulate and deliver functional components offer a wide range of applications.

Plant proteins used to stabilize Pickering emulsions primarily include zein, kafirin, soy protein isolates, gliadin, and hordein; however, there are still relatively few plant proteins available (Zhang, Xu, Chen, Wang, Wang & Zhong, 2021). Additionally, several studies have reported that tea water-insoluble protein nanoparticles (TWIPNs) can be used to prepare Pickering emulsions at an appropriate concentration and oil–water ratio (Ren et al., 2019, Ren et al., 2019). Pickering emulsions with excellent good stability and gelatin-like properties can form after high-pressure homogenization (Ren, Chen, Zhang, Lin & Li, 2020). The properties of Pickering emulsions prepared from these proteins have been studied under different high-pressure treatments, heat, pH, and ionic strength (Li et al., 2023, Luo et al., 2022, Singh and Sarkar, 2011). The properties and stability mechanism of Pickering emulsions stabilized by TWIPNs (TWIPNPEs) at different temperatures, pH and ionic strength have been discussed (Ren et al., 2021, Ren et al., 2022). However, whether TWIPNPEs can be used as a delivery system to encapsulate functional components to sustain release and improve the bioavailability of functional components in the simulated digestive system remains unknown.

Controlled-release systems, such as emulsions, are frequently employed for encapsulating and delivering poorly stable functional components, such as curcumin, β-carotene, lutein, and resveratrol (Boonlao et al., 2022, Fan et al., 2022, Li et al., 2020, Li et al., 2022, Xia et al., 2022). Resveratrol has poor photostability and thermal stability in an aqueous solution. The oral absorption rate of resveratrol reaches up to 75%; however, the bioavailability is<1% (Rotches-Ribalta, Andres-Lacueva, Estruch, Escribano & Urpi-Sarda, 2012). Resveratrol has a short retention time in the body and is susceptible to degradation in the gastrointestinal environment, limiting its bioavailability (Sessa et al., 2014). To improve its stability and bioavailability, resveratrol is primarily encapsulated using liposomes and traditional emulsion (Rehman et al., 2019). Several studies have demonstrated that entrapment in Pickering emulsions stabilized by chitosan/gum arabic (Sharkawy, Casimiro, Barreiro & Rodrigues, 2020) and chitosan hydrogel beads (Wu, Li, Li, Li, Ji & Xia, 2021) can improve the topical delivery and photostability of resveratrol. However, strategies to encapsulate and release resveratrol using TWIPNPEs still need to be explored.

This study aimed to analyze the characteristics of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol in terms of emulsion droplet size, zeta potential, and emulsion stability. Resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs was treated in vitro with simulated digestion, including simulated artificial saliva (SAS), simulated gastric fluid (SGF), and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF). The encapsulation efficiency (EE), release, and bioavailability of resveratrol were analyzed after being encapsulated in TWIPNPEs in the simulated digestive systems.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Tea residues were obtained from Shenbao Huacheng Tech. Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Soy oil was purchased from the local supermarket in Guangzhou of China. Trypsin (100 units/mg protein) and resveratrol (greater than99.0%) were purchased from TCI Chemical Industry Development Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Porcine gastric mucosa-derived pepsin (130 units/mg protein) and lipase (20,000 units/mg protein) were purchased from Merck Drugs & Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Bile extract porcine (≥60%) was purchased from New Probe Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), trichloromethane, and other reagents of analytical grade were obtained from Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory (Guangzhou, China). All water was deionized water.

2.2. Preparation of TWIPNs

TWIPNs were prepared using tea residues as described in a previous method (Ren et al., 2019). Tea residues were extracted at 90 °C for 1.5 h using a 0.3 mol/L NaOH solution at a mass-volume ratio of 1:30 (w/v). The TWIPN suspensions were centrifuged at 10,000 r/min for 15 min using an ultracentrifuge (Optima XE-100, Beckman, California, USA). The supernatant was then adjusted to pH 3.5 using 1 mol/L HCl after being decolorized with 30% H2O2 to precipitate the TWIPNs. The TWIPNs were collected after being washed to a neutral pH and dried with a freeze drier (ALPHA 1–2 LD Plus, Christ, Osterode, Germany). The hydrodynamic diameter of TWIPNs was 315.42 ± 51.28 nm at the concentration of 1.0 – 4.0% (w/v) with the zeta potential of −43.74 ± 0.72 mV (Ren et al., 2019).

2.3. Preparation of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol

TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol were prepared using TWIPNs and resveratrol as described in a previous report (Ren, Li et al., 2021). The TWIPN suspension of 1.0 – 4.0 % (w/v) was adjusted to pH 7.0. The suspension (20 mL) was mixed with 30 mL of soy oil either free of resveratrol or containing 200 μg/mL of resveratrol. Emulsions were prepared to homogenize the above solution using a shear emulsifying machine (AD500S-H, SUOTN, Shanghai, China) with a removable stator (diameter 12 mm) and a combined control button at 20,000 r/min for 2 min. The TWIPNPEs were obtained after being homogenized at 40 MPa with a high-pressure homogenizer (AH-Basic-II, ATS, Suzhou, China).

2.4. Determination of solubility of resveratrol

The solubility of resveratrol was determined according to a previous method (Davidov-Pardo & McClements, 2015). Firstly, resveratrol was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 100 µg/mL stock solution. The stock solution was then diluted with chloroform to 0.2, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10 µg/mL, and the absorbance at 307 nm was determined using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (UV-1100, MAPADA, Shanghai, China) at 307 nm to obtain the resveratrol standard curve.

The solubility of resveratrol at different temperatures was determined using a UV–vis spectrophotometer. Resveratrol (50 mg) was dispersed into soybean oil (10 mL) and stirred with a magnetic stirrer for 1 h in the dark. The dispersed system was stored at different temperatures (4, 20, 25 and 37 °C) for 24 h and protected from light. Then the solution was centrifuged at 8000 r/min for 15 min at 25 °C. The supernatant was diluted 100 times with trichloromethane and the absorbance at 307 nm was determined. Soybean oil without resveratrol was used as blank.

2.5. Measurement of droplet size and zeta potential of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol

The droplet size and particle size distribution of TWIPNPEs were measured at 25 °C with a laser particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). Deionized water and 1.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution were used as the dispersed system for assessing the TWIPNPEs. The shading rate was 10% – 20% at 2500 r/min, the background and samples were detected for 10 s, and the relative refractive index of the TWIPNPEs was 1.095, which is the ratio of soybean oil to water (1.456:1.33). The imaginary refractive index of the sample was 0.01. The volume-averaged size (d4,3) and particle size distribution of the TWIPNPEs were measured using the light scattering theory according to Eq. (1).

| (1) |

where ni and di represent the diameter of the ith emulsion droplet and the number of emulsion droplets, respectively.

The zeta potential of the TWIPNPEs was determined using a Zetasizer (Nano ZS90, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) according to a previous method (Yang, Gao & Yang, 2020). The TWIPNPEs were diluted 100 times before analysis. The diluent was added to the electric swimming pool and analyzed at 25 °C.

2.6. Fluorescence spectrum of resveratrol

The fluorescence spectra of resveratrol in solution and TWIPNPEs were determined using a multi-mode microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices, Silicon Valley, USA) with a photomultiplier detector. The excitation wavelength was 280 nm and the emission wavelength was 320 – 500 nm. The excitation and emission bandwidths were both 15 nm. Industry-leading SoftMax® Pro Software was used to test and examine the 96-well fluorescent plate.

2.7. Determination of encapsulation efficiency (EE) of resveratrol

The TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol were shaken at a speed of 170 r/min at 37 °C for 24 h. Then TWIPNPEs were centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 30 min. The supernatant was diluted by DMSO and centrifuged at 8000 r/min for 15 min at 25 °C. The absorbance at 307 nm was determined using a UV–vis spectrophotometer. The mass of resveratrol was determined according to the resveratrol standard curve. The EE of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs was calculated according to Eq. (2).

| (2) |

where ResE and ResT represent the mass (μg) of resveratrol encapsulated by TWIPNPEs in the final digestive system and initial addition, respectively.

2.8. Determination of stability of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs

The stability of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs was determined as described in a previous method (Sessa, Tsao, Liu, Ferrari & Donsì, 2011). A volume of 6 mL of the samples was added into a transparent petri dish with no cover (diameter, 47 mm) and illuminated for 24 h under a 365 nm UV lamp. Then the samples were centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 30 min. The supernatant was diluted by DMSO and centrifuged at 8000 r/min for 15 min at 25 °C. The absorbance of samples at 307 nm was determined using a UV–vis spectrophotometer. The percentage of remaining resveratrol was analyzed according to the standard curve.

2.9. In vitro simulated digestion of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs

TWIPNPEs without resveratrol were used as blank. Oil and water phases containing resveratrol were used as control. The samples were taken for further analysis (resveratrol content and appearance observation). The in vitro simulated digestion of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol was performed as follows.

The SAS system was used to evaluate the release profile of resveratrol in saliva according to a previous method (Pool, Mendoza, Xiao & McClements, 2013). The concentration of compounds in the SAS system is shown in Table S1. The SAS solution was adjusted to pH 6.8 with either 0.1 mol/L HCl or NaOH. Equal volumes of the SAS solution and TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol were mixed. The mixtures were wrapped with aluminum foil to prevent exposure to light and shaken at 95 r/min at 37 °C for 15 min.

The in vitro SGF system was used to evaluate the release profile of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs as described in previous reports, with minor modifications (Anwesha, Kelvinkt, Rpaul & Harjinder, 2009). The concentration of compounds in the SGF system is shown in Table S2. The SAS solution was adjusted to pH 1.2 with 1 mol/L HCl. The SAS solution (20 mL) was mixed with 10 mL of the SGF solution. The mixtures were wrapped with aluminum foil to prevent exposure to light and shaken at 95 r/min at 37 °C for 2 h. Before sampling and testing, the pH was adjusted to 7 to inactivate enzymes using 1 mol/L NaOH solution.

The in vitro SIF system was used to evaluate the process of resveratrol encapsulation in TWIPNPEs as described in previous reports, with slight modifications (Pool et al., 2013). The SGF digested mixtures were mixed with 5 mL bile extract solution (187.5 mg choline and 45 mg trypsin dissolved in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 and 37 °C), 1.0 mL CaCl2 solution (188 mmol/L CaCl2 dissolved in deionized water at 37 °C), and 1.0 mL NaCl solution (5.625 mol/L NaCl dissolved in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 and 37 °C). The above samples were adjusted to pH 7.0 and mixed with 1.5 mL freshly prepared lipase solution (60 mg lipase dissolved in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 and 37 °C).

After in vitro SGF and SIF, the resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs was centrifuged at 8000 r/min for 30 min at 4 °C. The middle liquid was obtained to determine the absorbance at 307 nm at various time intervals using UV–vis spectrophotometry at 307 nm.

2.10. Determination of bioavailability of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs

The bioavailability of resveratrol was evaluated after the SIF study. The samples were centrifuged at 20,000 r/min for 30 min at 10 °C. The samples were separated into the opaque sedimentary phase at the bottom and the supernatant micellar phase. The supernatant micellar phase was mixed with DMSO at a ratio of 1:25 (v/v) and centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 10 min at 25 °C. The absorbance of the supernatant at 307 nm was determined using UV–vis spectrophotometry. Resveratrol bioavailability (RB) was calculated according to Eq. (3).

| (3) |

where RESM and RESI represent resveratrol content in micelles of the simulation system and emulsion/oil phase, respectively.

2.11. Data analysis

All tests were carried out in triplicate. The results were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) was applied to test in Origin Pro 9.0.5. The differences between the data were analyzed at a significant level of P < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of temperature on the solubility of resveratrol

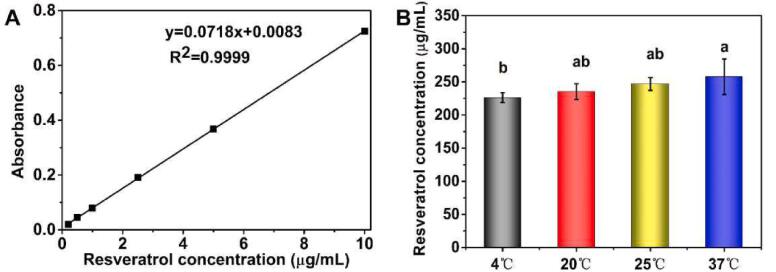

Temperature is an important factor that affects the solubility of resveratrol. Firstly, the standard curve of resveratrol in DMSO was described as shown in Fig. 1A. The regression equation of the standard curve was y = 0.0718x + 0.0083 (R2 = 0.9999). The solubility of resveratrol in soybean oil at different temperatures was analyzed to encapsulate resveratrol in TWIPNPEs as shown in Fig. 1B. The solubility of resveratrol was lowest at 4 °C. The concentration of resveratrol in the oil phase should be lower than its minimum solubility of 226.23 ± 7.39 µg/mL to prevent precipitation and poor encapsulation efficiency of water-insoluble functional components during the preparation, storage, and use of the emulsion delivery system. Based on this, a resveratrol concentration of 200 µg/mL in the oil phase was chosen for subsequent encapsulation and release experiments.

Fig. 1.

Standard curve of resveratrol and solubility of resveratrol at different temperatures * Upper lowercase letters in the figure indicate significance at P < 0.05.

3.2. Stability of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol

The particle size distribution, d4,3, and zeta potential of the TWIPNPEs before and after encapsulating resveratrol were compared as shown in Fig. 2. No difference was observed in the particle size distribution of the TWIPNPEs after encapsulating resveratrol at the same TWIPN concentration (Fig. 2A and B). The d4,3 of the TWIPNPEs without encapsulating resveratrol decreased with the increase in TWIPN concentrations (1% – 4% (w/v)) in similar with that encapsulating resveratrol. The d4,3 of the TWIPNPEs slightly increased after encapsulating resveratrol using TWIPN concentrations of 1.0% and 2.0% (w/v) and decreased at 3.0% and 4.0% (w/v) compared to that without encapsulating resveratrol at the same TWIPN concentration (Fig. 2C). The introduction of resveratrol may have affected the oil–water interface, leading to a change in the emulsion droplet size (Shi et al., 2021). Meanwhile, the d4,3 of TWIPNPEs after encapsulating resveratrol increased with increasing TWIPN concentration, similar to the d4,3 trend of TWIPNPEs before encapsulating resveratrol.

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of TWIPNPEs before and after encapsulating resveratrol (A: Before; B: After; C: d4,3; D: zeta potential.).

The zeta potential of TWIPNPEs after encapsulating resveratrol is shown in Fig. 2D. The absolute value of the zeta potential decreased after encapsulating resveratrol at the same TWIPN concentrations (1.0% and 2.0%, w/v) and increased at 3.0% and 4.0% (w/v). The changing trend of zeta potential of the TWIPNPEs after encapsulating resveratrol was the same as those without encapsulating resveratrol. At TWIPN concentrations between 1.0% and 4.0% (w/v). the absolute zeta potential value of the TWIPNPEs after encapsulating resveratrol was above 40 mV, indicating a strong repulsion between the TWIPNPEs as previously reported (Santos et al., 2018, Sow et al., 2019). Therefore, the TWIPNPEs were still stable after encapsulating resveratrol and the addition of resveratrol did not affect their stability.

3.3. Characteristics of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs

3.3.1. Fluorescence spectra of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs

The environment significantly affects the fluorescence spectra of resveratrol, and the hydrophobic interaction between resveratrol and emulsion is determined to identify resveratrol (Shi et al., 2021). The fluorescence spectra of resveratrol in the water phase, soybean oil, and TWIPNPEs are shown in Fig. 3. From the water phase to TWIPNPEs, the emission peak position of resveratrol was at a shorter wavelength, indicating a blue shift. From the water system (hydrophilic system) to the soybean oil system (hydrophobic system), the peak position shifted from 400 nm to 378 nm. The emission peak position of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs prepared at different TWIPN concentrations of 1.0% – 4.0% (w/v) were 380 nm, 382 nm, 382 nm, and 384 nm, respectively, indicating that resveratrol was located in a hydrophobic environment, namely in the emulsion droplets. This result is consistent with a previous report that the blue shift of resveratrol encapsulated in nanoemulsions occurred, with the emission peak position shifting from 400 nm in the aqueous phase to 386 nm in the emulsions (Sessa et al., 2014).

Fig. 3.

(A) Fluorescence emission spectra of resveratrol dissolved in water, soybean oil, and TWIPNPEs; (B) Encapsulation efficiency of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs; (C) Percentage of remaining resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs irradiated with UV light at 365 nm for 24 h* Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences under P < 0.05.

The emission peak position of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs showed a red shift with increasing TWIPN concentration, indicating that resveratrol was affected by TWIPN concentration. This may be attributable to tryptophan residues in proteins being transferred to an environment with a relatively low hydrophobicity (Rampon, Genot, Riaublanc, Anton, Axelos & McClements, 2003). Additionally, the fluorescence intensity of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs was higher than that of resveratrol in the aqueous and soybean oil phases (Fig. 3A). The fluorescence intensity of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs at 2.0% – 4.0% (w/v) gradually decreased. This result indicated that TWIPNPEs prepared at a high TWIPN concentration with small emulsion droplet sizes could protect against resveratrol exposure in the lipophilic microenvironment of internal droplets.

3.3.2. Encapsulation efficiency of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs

The EE of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs is important for the delivery system due to the change in its chemical stability in different environmental conditions. The EE of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs prepared at different concentrations is shown in Fig. 3B. The TWIPNPE prepared using 1.0% TWIPN had an EE < 50%, which was low. This can be attributed to the fact that large emulsion droplets do not enhance the encapsulation of resveratrol. The EE of resveratrol improved with increasing TWIPN concentration and reached more than 85% at 3.0% and 4.0% (w/v), which is higher than that in emulsions stabilized by whey protein/gum Arabic mixtures (Shao, Feng, Sun & Ritzoulis, 2019). This result indicated that most of the resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs prepared at TWIPN concentrations of 3.0% and 4.0% (w/v) occupied the oil phase, which was also confirmed by the fluorescence spectra of resveratrol (Fig. 3A).

The proportion of resveratrol in the aqueous phase was calculated as described in previous reports (McClements, 2012). It was shown in Eq. (4).

| (4) |

Where ϕm,w, ϕo, and Kow are the percentage of functional components in the aqueous phase, oil phase ratio (0.6), and oil/water distribution coefficient (1050), respectively. According to this equation, the proportion of resveratrol in the aqueous phase at equilibrium was 6.35%. This is also an important reason why the EE of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs is<100%.

3.3.3. Stability of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs

Resveratrol is prone to photochemical degradation during storage, especially when exposed to the UV-light. The percentage of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs irradiated with UV light at 365 nm for 24 h was determined as shown in Fig. 3C. The EE of resveratrol in the control group was significantly lower than that in the TWIPNPEs. The EE of resveratrol in TWIPNPEs significantly (P < 0.05) increased with the increase in TWIPN concentration. TWIPNPEs prepared at the TWIPN concentration of 4.0% (w/v) were selected for encapsulation and in vitro digestion based on the EE and stability of resveratrol in the TWIPNPEs.

3.4. In vitro digestion profiles of TWIPNPEs

Lipids in foods may be consumed in various forms (e.g., emulsified, bulk, and structural oil), and the digestion, absorption, and biotransformation of lipid and lipid-soluble nutrients are quite important in product design (Lomova, Sukhorukov & Antipina, 2010). The physicochemical properties of TWIPNPEs were investigated using in vitro digestion.

3.4.1. d4,3 and zeta potential of TWIPNPEs during in vitro digestion

The integrity of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol in the digestion simulation system was assessed. The d4,3 and zeta potential of TWIPNPEs are presented in Fig. 4A and B. In the whole stages, the d4,3 and zeta potential of TWIPNPEs with or without resveratrol had no significant change (P < 0.05). Firstly, the d4,3 of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol was analyzed in the SAS, SGF and SIF systems as shown in Fig. 4A.

Fig. 4.

D4,3 (A), zeta potential (B) and particle size distribution (C: TWIPNPEs without encapsulating resveratrol; D: TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol.) of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol in different simulated digestion stages* SAS: simulated artificial saliva; SGF: simulated gastric fluid; SIF: simulated intestine fluid.

In the SAS stage, the d4,3 of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol was the same as the initial emulsion particle size. In the SGF stage, the d4,3 of TWIPNPEs sharply increased and remained constant for 1.5 h after the SGF digestion. As previously reported, this is mainly due to the acidic environment of the SGF system close to the TWIPN isoelectric point of 3.5, greatly promoting droplet flocculation due to the aggregation of proteins (Ren et al., 2022). Meanwhile, the flocculation of emulsion droplets was eliminated by increasing the pepsin and salt ion digestion time.

To further clarify the changes of TWIPNPEs in the different digestion simulation stages, the zeta potential of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol is shown in Fig. 4B. In the SAS and GIF stages, the TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol were negatively charged and their absolute zeta potential value was above 40 mV. In the SGF stage, the zeta potential of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol was positive and the absolute value was below 20 mV. These results indicated that the digestion fluids were in a relatively stable state in the SAS and SIF system; however, the emulsions in the digestive systems could not stably exist in the SGF system prone to flocculation. The reduction in the absolute value of zeta potential in the SGF system may be attributed to the electrostatic shielding effect of ionic strength and protein flocculation between different emulsion interfaces in the SGF. This result also showed the d4,3 changes in the TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol (Fig. 4A).

3.4.2. Particle size distribution of TWIPNPEs during in vitro digestion

The particle size distribution of the TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol was further compared in the digestive simulation system as shown in Fig. 4C and D. The particle size distribution of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol in the SAS presented a bimodal distribution from 1 to 10 μm. However, the particle size distribution of the TWIPNPEs in the SGF became wide and the d4,3 even reached several hundred microns; meanwhile, the particle size distribution of the TWIPNPEs in the SGF ranged from 1 to 500 μm. This indicated that the emulsion droplets underwent flocculation and coalescence (Zhou, Zeng, Yin, Tang, Yuan & Yang, 2018). The TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol had the same particle size distribution as the TWIPNPEs without resveratrol. This is consistent with the results of the droplet size of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol (Fig. 4A).

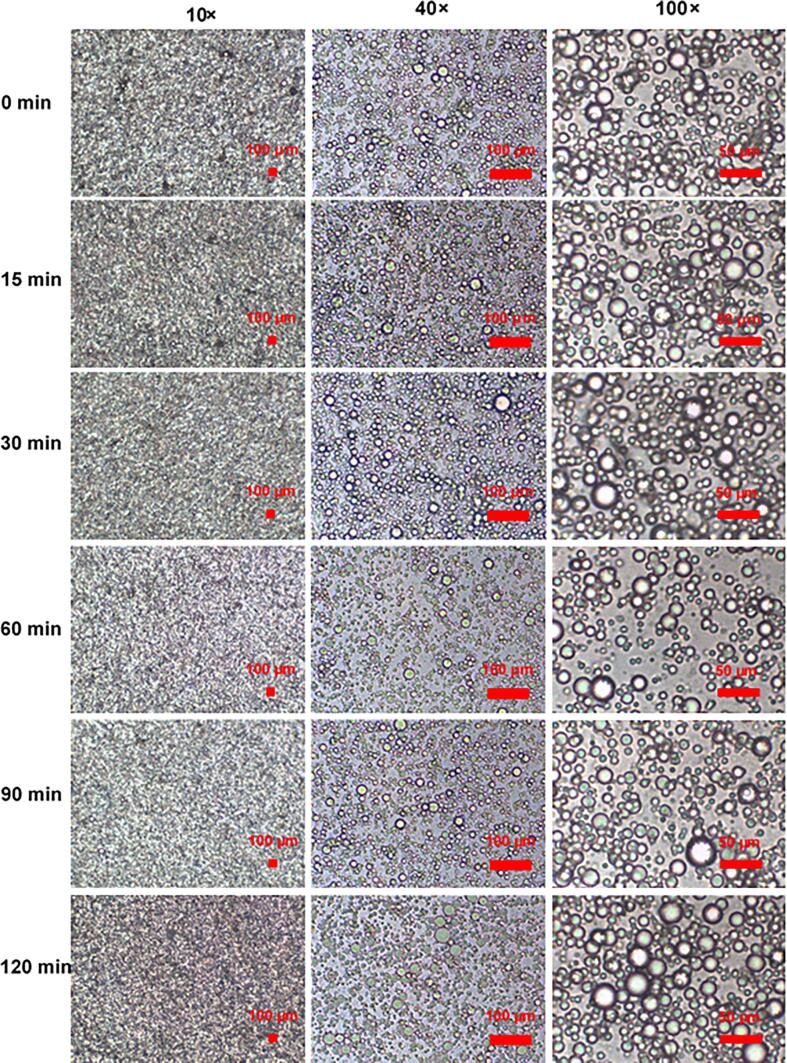

3.4.3. Microscopic observation of TWIPNPEs in vitro digestion

The microscopic observation results of the TWIPNPEs in the simulated digestive system are shown in Fig. 5, Fig. 6 and Fig. S1-4. These results were consistent with the results of particle size and particle size distribution. After the SAS, the microscopic observation results of the TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol and TWIPNPEs without resveratrol are shown in Fig. S1 and Fig. S2. The SAS had no significant change in the particle size, which is consistent with the results in Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Microscopic observation of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol in the simulated gastric fluid stage.

Fig. 6.

Microscopic observation of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol in the simulated intestine fluid stage.

Whether or not resveratrol was encapsulated in the Pickering emulsions, a large amount of flocculation was observed at different moments in the SGF stage (Fig. 5 and Fig. S3). The d4,3 of the TWIPNPEs had a slight increase and the absolute value of zeta potential was significantly lower than 20 mV as shown in Fig. 4B. These results indicated that the TWIPNPEs were extremely unstable and thus formed a large number of floccules. When pH is close to the isoelectric point of TWIPNs (pH 1.2), the aggregation of the TWIPNPEs increases in the SGF stage (Ren et al., 2022). Additionally, the colloidal systems are unstable when the absolute value of zeta potential is below 30 mV (Sow et al., 2019).

In the SIF stage, the TWIPNPE floccules formed during the digestion process dispersed uniformly regardless of resveratrol encapsulation in the TWIPNPEs as shown in Fig. 6 and Fig. S4, but the size of emulsions increased slightly after a series of simulation digestions. This may be attributed to the effect of different simulation digestion stages involving a variety of digestive enzymes and salt ions, leading to a change in emulsion droplet size.

3.5. In vitro release and bioavailability of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs

Resveratrol is easily metabolized in the intestine and liver to generate glucuronic acid or sulfuric acid conjugated compounds, which have a half-life of 9.2 h in vivo and are not easily decomposed (Zu et al., 2016). Besides, the extensive metabolism and absorption of resveratrol in the body are severely limited due to that resveratrol is mainly excreted through the kidney as sulfate and glucuronic acid conjugates (Urpi-Sarda et al., 2007). Based on the analysis of the characteristics of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol in the simulated digestive system, the in vitro release and bioavailability of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs in the SAS and SGF systems were evaluated as shown in Fig. S5. Resveratrol in soybean oil released more than 50% in the SAS stage and appropriately 60% of resveratrol was released after 2 h of digestion (Fig. S5A). This is mainly because resveratrol lacks a delivery system protection during the SAS and SGF digestion and degrades with the change in the environmental conditions of the digestion simulation. However, resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs was protected by the emulsion system and not easily degraded in the SAS and SGF systems. After proceeding with the SGF system, the release of resveratrol from the TWIPNPEs was greater than 80%. Besides, TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol exhibited a gel-like behavior as shown in Fig. S6, which could improve the release of resveratrol. As previously reported, Pickering emulsions stabilized by alginate/κ-carrageenan hydrogel beads can enhance the release of resveratrol (Wu, Li, Li, Li & Xia, 2022). These results indicated that TWIPNPEs could improve the stability of resveratrol and maintain the sustained release of resveratrol in the simulated digestive system.

The bioavailability of TWIPNPEs encapsulating resveratrol is shown in Fig. S5B. The bioavailability of resveratrol in soybean oil was lower than 3% in the SIF systems. Although the release of resveratrol in soybean oil was above 50% in the SAS and SGF systems, resveratrol was largely degraded under the action of trypsin, lipase, and choline after entering the SIF system. The bioavailability of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs after 2 h digestion in the SIF system was above 10%. This can be attributed to the chylous formation after resveratrol is encapsulated in TWIPNPEs, slowing down the degradation of resveratrol with the action of trypsin, lipase, and choline in the SIF system, thus improving the bioavailability of resveratrol.

Resveratrol is easily degraded by UV light. In the simulated digestive system, unencapsulated resveratrol may be degraded by external factors such as dissolved oxygen, temperature, and light (Sessa et al., 2014). According to the aforementioned results, the metabolic degradation of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs can be reduced in the SAS and SGF digestion stage, enabling more undegraded resveratrol to reach the SIF to improve its intestinal absorption. This is beneficial for improving the bioavailability of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs. The emulsion system plays a critical role in protecting functional components during simulated digestion (Sessa et al., 2011).

The in vitro digestion of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs is illustrated in Fig. S7. Pickering emulsions encapsulating resveratrol prepared by high-speed and high-pressure homogenization could protect resveratrol from photodegradation (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The above results also showed that TWIPNPEs at a concentration of 4.0% continued to keep resveratrol encapsulated in the oil phase during the in vitro digestion (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). As a result, resveratrol was not metabolized in the SAS and SGF stages but reached the colon in its active form for intestinal absorption. TWIPNPEs can be regarded as an efficient delivery system to enhance the bioavailability of nutritional and functional food ingredients.

Along with the lipids that are digested by humans, the digest products, such as free fatty acids, monoacylglycerols, and diacylglycerols can be released to interact with the body’s secreted bile salts, phospholipids, and cholesterol to form mixed micelles (Fan et al., 2022). The originally dissolved resveratrol in the internal phase (soy oil) with human digestion becomes available for absorption in the human body. This is a complicated process in vivo digestion compared with that in the in vitro digestion simulation. Therefore, the in vivo digestion of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs can be considered for further research.

4. Conclusion

This study showed that the TWIPNPEs could encapsulate resveratrol. The d4,3 of the TWINPEs after encapsulating resveratrol had no significant change and their absolute value of zeta potential was above 40 mV compared to those without resveratrol. The stability of the TWIPNPEs before and after encapsulating resveratrol was further demonstrated by particle size distribution and microscopy. However, the characteristics of resveratrol encapsulated in the TWIPNPEs changed. The emission peaks of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs stabilized at TWIPN concentrations of 1.0 – 4.0% (w/v) shifted from 380 nm to 384 nm. This result showed that resveratrol was present in a hydrophobic environment, namely in the emulsion droplets. Additionally, the EE of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs at TWIPN concentrations of 3.0% and 4.0% was greater than that of the other groups, reaching more than 85%. The EE of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs at the TWIPN concentration of 4.0% was greater than 80% after UV irradiation at 365 nm for 24 h, indicating a reduction in the susceptibility of resveratrol to photodegradation. The bioavailability of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs was improved in the process of simulated in vitro digestion. In the SAS and SGF systems, the sustained release of resveratrol from the TWIPNPEs was better than that observed in the unencapsulated resveratrol. The bioavailability of resveratrol encapsulated in TWIPNPEs in the SIF system was improved, reaching more than 10%. These results may be useful for designing effective delivery systems for nutraceuticals based on Pickering emulsions and broadening the application of tea byproducts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhongyang Ren: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Data curation, Resources. Zhongzheng Chen: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Yuanyuan Zhang: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Xiaorong Lin: Validation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Wuyin Weng: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Bin Li: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shenzhen Shenbao Huacheng Tech. Co., Ltd. for kindly providing the tea leaves. This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD2100204), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province in China (2021J01835), Fujian Science and Technology Project (2021N5013), Special Fund from the Modern Agricultural Industry of China (CARS-19), Project of Education Department of Fujian Province (JAT200268) and the Scientific Research Foundation of Jimei University in China (ZQ2020011).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100642.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Anwesha S., Kelvinkt G., Rpaul S., Harjinder S. Behaviour of an oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by β-lactoglobulin in an in vitro gastric model. Food Hydrocolloids. 2009;23(6):1563–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Boonlao N., Ruktanonchai U.R., Anal A.K. Enhancing bioaccessibility and bioavailability of carotenoids using emulsion-based delivery systems. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2022;209 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.112211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov-Pardo, G., & McClements, D. J. (2015). Nutraceutical delivery systems: resveratrol encapsulation in grape seed oil nanoemulsions formed by spontaneous emulsification. Food Chemistry, 167(Supplement C), 205-212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Đorđević V., Balanč B., Belščak-Cvitanović A., Lević S., Trifković K., Kalušević A.…Nedović V. Trends in encapsulation technologies for delivery of food bioactive compounds. Food Engineering Reviews. 2015;7(4):452–490. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Luo D., Yi J. Resveratrol-loaded α-lactalbumin-chitosan nanoparticle-encapsulated high internal phase Pickering emulsion for curcumin protection and its in vitro digestion profile. Food Chemistry: X. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraji H., McClements D.J., Decker E.A. Role of continuous phase protein on the oxidative stability of fish oil-in-water emulsions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004;52(14):4558–4564. doi: 10.1021/jf035346i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D., Deng S., McClements D.J., Zhou L., Zou L., Yi J.…Liu W. Encapsulation of β-carotene in wheat gluten nanoparticle-xanthan gum-stabilized Pickering emulsions: Enhancement of carotenoid stability and bioaccessibility. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;89:80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Zhang B., Li C., Fu X., Huang Q. Pickering emulsion gel stabilized by octenylsuccinate quinoa starch granule as lutein carrier: Role of the gel network. Food Chemistry. 2020;305 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wang Y., Luo Y. High internal phase Pickering emulsions stabilized by egg yolk low density lipoprotein for delivery of curcumin. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2022;211 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Xiong Y., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Luo Y. Low density lipoprotein-pectin complexes stabilized high internal phase pickering emulsions: The effects of pH conditions and mass ratios. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;134 [Google Scholar]

- Lomova M.V., Sukhorukov G.B., Antipina M.N. Antioxidant coating of micronsize droplets for prevention of lipid peroxidation in oil-in-water emulsion. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces. 2010;2(12):3669–3676. doi: 10.1021/am100818j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Cheng L., Zhang R., Yang Z. Impact of high-pressure homogenization on physico-chemical, structural, and rheological properties of quinoa protein isolates. Food Structure. 2022;32 [Google Scholar]

- McClements D.J. Crystals and crystallization in oil-in-water emulsions: Implications for emulsion-based delivery systems. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2012;174:1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A.R. Functional and engineered colloids from edible materials for emerging applications in designing the food of the future. Advanced Functional Materials. 2018;1806809 [Google Scholar]

- Pool H., Mendoza S., Xiao H., McClements D.J. Encapsulation and release of hydrophobic bioactive components in nanoemulsion-based delivery systems: Impact of physical form on quercetin bioaccessibility. Food & Function. 2013;4(1):162–174. doi: 10.1039/c2fo30042g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampon V., Genot C., Riaublanc A., Anton M., Axelos M.A., McClements D.J. Front-face fluorescence spectroscopy study of globular proteins in emulsions: Influence of droplet flocculation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(9):2490. doi: 10.1021/jf026167o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman A., Ahmad T., Aadil R.M., Spotti M.J., Bakry A.M., Khan I.M.…Tong Q. Pectin polymers as wall materials for the nano-encapsulation of bioactive compounds. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2019;90:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Lin X., Li Z., Weng W.…Li B. Effect of heat-treated tea water-insoluble protein nanoparticles on the characteristics of Pickering emulsions. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2021;149 [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Lin X., Weng W., Liu G., Li B. Characteristics of Pickering emulsions stabilized by tea water-insoluble protein nanoparticles at different pH values. Food Chemistry. 2022;375 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Lin X., Li B. Novel food-grade Pickering emulsions stabilized by tea water-insoluble protein nanoparticles from tea residues. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;96:322–330. [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Lin X., Li B. Characteristics and rheological behavior of Pickering emulsions stabilized by tea water-insoluble protein nanoparticles via high-pressure homogenization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;151:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Zhao T., Ye X., Gao X.…Li B. Functional properties and structural profiles of water-insoluble proteins from three types of tea residues. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2019;110:324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z., Li Z., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Lin X., Weng W.…Li B. Characteristics and application of fish oil-in-water pickering emulsions structured with tea water-insoluble proteins/κ-carrageenan complexes. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;114 [Google Scholar]

- Rotches-Ribalta M., Andres-Lacueva C., Estruch R., Escribano E., Urpi-Sarda M. Pharmacokinetics of resveratrol metabolic profile in healthy humans after moderate consumption of red wine and grape extract tablets. Pharmacological Research. 2012;66(5):375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M.B., Da Costa N.R., Garcia-Rojas E.E. Interpolymeric complexes formed between whey proteins and biopolymers: Delivery systems of bioactive ingredients. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2018;17(3):792–805. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa, M., Balestrieri, M. L., Ferrari, G., Servillo, L., Castaldo, D., D Onofrio, N., Donsì, F., & Tsao, R. (2014). Bioavailability of encapsulated resveratrol into nanoemulsion-based delivery systems. Food Chemistry, 147(Supplement C), 42-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sessa M., Tsao R., Liu R., Ferrari G., Donsì F. Evaluation of the stability and antioxidant activity of nanoencapsulated resveratrol during in vitro digestion. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2011;59(23):12352–12360. doi: 10.1021/jf2031346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao P., Feng J., Sun P., Ritzoulis C. Improved emulsion stability and resveratrol encapsulation by whey protein/gum arabic interaction at oil-water interface. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2019;133:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkawy A., Casimiro F.M., Barreiro M.F., Rodrigues A.E. Enhancing trans-resveratrol topical delivery and photostability through entrapment in chitosan/gum arabic Pickering emulsions. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;147:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi A., Wang J., Guo R., Feng X., Ge Y., Liu H.…Wang Q. Improving resveratrol bioavailability using water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) emulsion: Physicochemical stability, in vitro digestion resistivity and transport properties. Journal of Functional Foods. 2021;87 [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., Sarkar A. Behaviour of protein-stabilised emulsions under various physiological conditions. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2011;165(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sow L.C., Toh N.Z.Y., Wong C.W., Yang H. Combination of sodium alginate with tilapia fish gelatin for improved texture properties and nanostructure modification. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;94:459–467. [Google Scholar]

- Urpi-Sarda M., Zamora-Ros R., Lamuela-Raventos R., Cherubini A., Jauregui O., de la Torre R.…Andres-Lacueva C. HPLC-tandem mass spectrometric method to characterize resveratrol metabolism in humans. Clinical Chemistry. 2007;53(2):292. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.071936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Li Y., Li Y., Li H., Ji S., Xia Q. Pickering emulsions-chitosan hydrogel beads carrier system for loading of resveratrol: Formulation approach and characterization studies. Reactive and Functional Polymers. 2021;169 [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Li Y., Li Y., Li H., Xia Q. The influence of Ca2+/K+ weight ratio on the physicochemical properties and in vitro digestion behavior of resveratrol-loaded Pickering emulsions encapsulated in alginate/κ-carrageenan hydrogel beads. Reactive and Functional Polymers. 2022;181 [Google Scholar]

- Xia T., Gao Y., Liu Y., Wei Z., Xue C. Lactoferrin particles assembled via transglutaminase-induced crosslinking: Utilization in oleogel-based Pickering emulsions with improved curcumin bioaccessibility. Food Chemistry. 2022;374 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., Li Y., Huang Q. Recent advances on food-grade particles stabilized Pickering emulsions: Fabrication, characterization and research trends. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2016;55:48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Gao S., Yang H. Effects of sucrose addition on the rheology and structure of iota-carrageenan. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;99 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Xu J., Chen J., Wang Z., Wang X., Zhong J. Protein nanoparticles for Pickering emulsions: A comprehensive review on their shapes, preparation methods, and modification methods. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2021;113:26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Zeng T., Yin S., Tang C., Yuan D., Yang X. Development of antioxidant gliadin particle stabilized Pickering high internal phase emulsions (HIPEs) as oral delivery systems and the in vitro digestion fate. Food & Function. 2018;9(2):959–970. doi: 10.1039/c7fo01400g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu Y., Zhang Y., Wang W., Zhao X., Han X., Wang K., Ge Y. Preparation and in vitro/in vivo evaluation of resveratrol-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles. Drug Delivery. 2016;23(3):971–981. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.924167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.