Abstract

Context:

While laparoscopy has been the standard procedure for gallstone treatment, recent advances including the use of indocyanine green (ICG) in laparoscopic cholecystectomy have made it easier to understand the biliary tree and reduce the risk of bile duct injury.

Aims:

In this retrospective study, we aim to determine the efficacy of ICG in near-infrared fluorescence cholangiography (NIRFC) for visualising biliary anatomy.

Settings and Design:

A total of 90 patients with the symptoms of cholelithiasis were enrolled for this retrospective study.

Subjects and Methods:

All the patients underwent cholecystectomy approximately 53.8 min (40–90 min) after the intravenous administration of mean volume 1.6 ml (1–2 ml) ICG. The surgeons used NIRFC along with ICG for real-time visualisation of biliary anatomy.

Results:

The mean operative time for the surgery was 65.7 min (25-120 min) with no post-surgical complications observed in the patients. The average length of stay was 2 days (1–3 days). ICG usage with NIRFC enabled identification of cystic duct, common hepatic and common bile duct, the junction between common hepatic and bile duct, right and left hepatic duct in 87.7%, 94.4%, 80% and 14.4% of cases, respectively.

Conclusions:

ICG fluorescence allowed successful visualisation of at least 1 biliary structure in 100% of cases.

Keywords: Biliary anatomy, cholecystectomy, indocyanine green, infrared fluorescence

INTRODUCTION

For several years now, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been used for the treatment of symptomatic gallstones. Since the early 1990s, it has largely replaced the open technique for cholecystectomies,[1] thereby becoming one of the most frequently performed procedures in general surgery.[2] It has also proven to be feasible, safe, cost-effective and represents the gold standard treatment for gallstone disease.[2] The procedure’s most important risk factors are acute cholecystitis, adhesions, high body mass index, anatomical variations, bleeding and bile duct injury (BDI).[2] The incidence of BDI in laparoscopic cholecystectomy ranges from 0.4% to 0.7%. However, it remains a serious complication and a major cause for morbidity or mortality after surgery.[2] For a patient undergoing an elective cholecystectomy, BDI is an unexpected and devastating complication. It is associated with high morbidity, even mortality and generally requires invasive treatment.[3] Even a minor injury may lead to considerable morbidity due to persistent bile leakage and biliary sepsis.[3] Late complications include biliary strictures, anastomotic strictures, recurrent cholangitis and biliary cirrhosis that further increases a patient’s morbidity and mortality.[3] Moreover, BDI patients show impaired quality of life years after cholecystectomy.[3]

One of the major reasons for BDI is related to misperception and improper identification of the biliary duct.[4] Endeavours to increase the safety of the procedure has led to optimised intraoperative processes, such as photographic documentation of the “critical view of safety” (CVS), first described by Strasberg and colleagues almost 20 years ago.[4] Using the CVS technique, the calot’s triangle is completely unfolded by mobilising the gallbladder neck from the gallbladder bed of the liver.[4] The Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons with Safe Cholecystectomy Task Force has launched an initiative to improve safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The aim is to encourage a culture of safety in the procedure and reduce biliary injury.[4] The following are the top five most important factors linked to safe practice in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[4]

Establishing “CVS”

Relevant anatomy identification

Appropriate retraction and exposure

To call for help if needed

Recognising the need to switch to open cholecystectomy or an alternate procedure.

Different dissection techniques (anterograde dissection and infundibular dissection) and landmark techniques such as identification of Rouviere’s sulcus and Calot’s node, can be employed to perform a stepwise cholecystectomy.[4] Cohort analysis of medicare patients undergoing cholecystectomy from 1992 to 1999 suggested that BDI increases in the absence of intraoperative cholangiography.[5] Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is currently the gold standard for the diagnosis of biliary obstruction. It is one of several invasive direct cholangiography techniques.[6] However, it is an imperfect diagnostic tool and other procedures may be more appropriate gold standards for the diagnosis in the future.[6] Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an alternative to diagnostic ERCP for biliary tree imaging and investigating biliary obstruction. MRCP was developed in 1991 and techniques are improving continuously.[6] MRCP also does not have the small but definite morbidity and mortality associated with ERCP.[6]

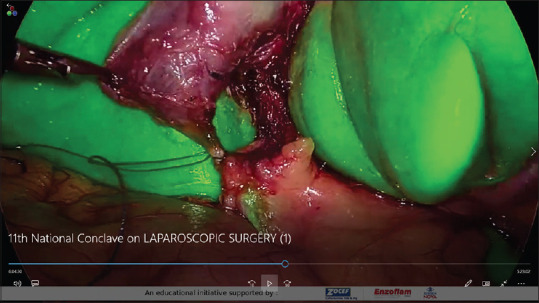

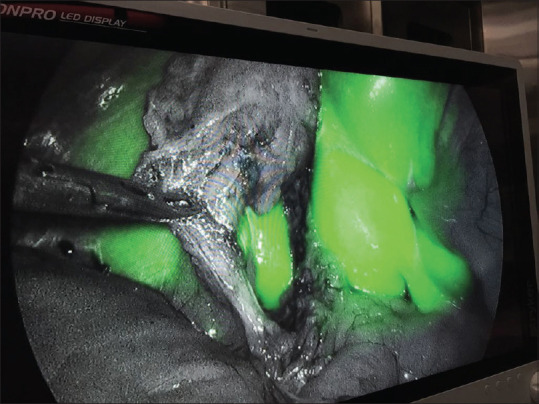

Fluorescent imaging introduced a non-invasive option for better delineation of biliary anatomy [Figure 1]. In recent years, several centres have proposed near-infrared fluorescence cholangiography (NIRFC) with indocyanine green (ICG) as a potential method of dynamic intraoperative extrahepatic bile duct mapping.[7] ICG is a hydrophilic tricarbocyanine dye with fluorescent properties developed by Eastman Kodak as a sensitising agent in photograph development in the early 1950s.[7] It is a water-soluble dye, and after entering the human blood circulation, it binds to plasma protein and rapidly enters hepatocytes.[8] The dye remains mainly intravascular, with a half-life of 2–5 min which is then metabolized almost exclusively by the hepatic parenchymal cells and secreted entirely into the bile.[2] When illuminated with near-infrared light, protein-bound ICG shows fluorescence at a wavelength of around 840 nm.[8] NIRFC requires pre-operative intravenous injection of ICG. This allows surgeons to have a high-resolution vision of near-infrared images of blood flow, organ perfusion and biliary structures [Figure 2].[2]

Figure 1.

Visualisation of biliary structures using indocyanine green

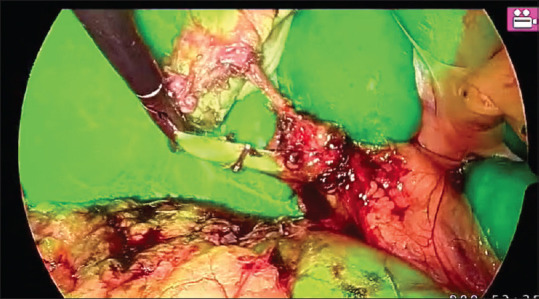

Figure 2.

Representation of intraoperative images

The use of ICG fluorescence has no radiation hazard for the patient. It neither prolongs operative time nor extend the learning curve.[2] Furthermore, the risk of anaphylactic reactions is approximately 0.003% at doses exceeding 0.5 mg/kg.[9] Hence, ICG fluorescent cholangiography is a safe and effective procedure that helps in real-time visualisation of the biliary duct anatomy [Figure 3]. The allergic reaction risk is minimal, and essentially, there is no increase in operative time. It can help in the identification of the Calot’s triangle structures even in challenging situations observed in acute cholecystitis and obese patients.[2]

Figure 3.

View of anatomy following cystic duct dissection

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

In this retrospective study, 90 patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy using NIRFC after injecting ICG for better visualisation of biliary anatomy [Graph 1]. The patient data, including demographics, intraoperative findings, post-operative complications and structures seen before and after dissection of the Calot’s triangle were recorded.

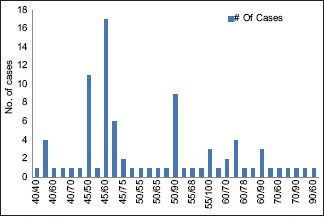

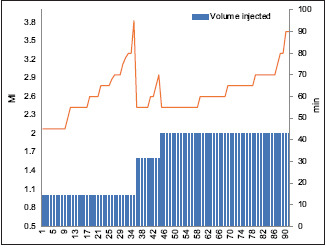

Graph 1.

Majority of the cases were injected with ICG 45–60 min before the surgery. The time taken for visualization was between 45 min and 60 min for majority of the patients

The inclusion criteria to select the patients consisted of specific age group (18–60 years), American Society of Anaesthesiologists score 1–3, symptoms of gallbladder disease and gallstones confirmed by ultrasound. The exclusion criteria were acute cholecystitis, biliary pancreatitis, suspicion of common bile duct stones and gross deviation of liver function tests. Previous upper abdominal open surgery was also considered as a contraindication. Furthermore, severe systemic illness, a history of adverse reaction to ICG, and any medical condition including pregnancy contraindicating a surgical approach were considered reasons not to proceed with the surgery. The selected patients gave their written consent for the study, and surgeries were performed by the authors of the article. Out of 90 laparoscopic surgeries performed with ICG fluorescent cholangiography. On inspection, the perioperative diagnosis was cholelithiasis for 53 patients and thick-walled gallbladder for 37 patients. After the completion of the surgery, the mean duration for a stay in the hospital was 2 days (1–3 days). The patients were then observed for postoperative complications and a.

Near-infrared imaging and surgical technique

For the surgical procedure, mean volume of 1.6 ml (1–2 ml) of ICG was administered intravenously. The timing of ICG administration varied with the mean time of 53.8 min (40–90 min) [Graph 2]. After the administration of anaesthesia, an incision of average size 1 cm (1–1.2 cm) was made at the umbilical site on the abdomen. NIFC was used to assess the intraoperative visualisation of hepatic structures (cystic duct, common bile duct, common hepatic duct, right and left hepatic ducts and the junction between cystic duct and hepatic duct). The surgeon could easily switch from normal mode to fluorescent mode at any time during the surgical procedure to visualize the images. Then, the Calot’s triangle was dissected, and fluorescent imaging was used for the second time to assess the biliary anatomy.

Graph 2.

In majority of the cases, the average time taken for visualisation after injection was found to be 50–70 min irrespective of the volume injected

RESULTS

In our experience with the study, we observed that the use of NIRFC and ICG improved efficacy of biliary anatomy visualisation. During the study period, it was observed that the mean operative time of the procedure was 65.7 min (25–120 min), and the estimated blood loss was found to be an average of 13 ml (5–50 ml). The average age of 83 patients selected for the study was 41 years (18–60 years). The average size of the incision made was 1 cm (1–1.2 cm) with no additional requirement for blood transfusion observed during the surgery. The mean time for intravenous administration of ICG before the dissection of Calot’s triangle was observed to be 53.8 min (40–90 min). Patients didn’t experience any intraoperative complications or allergic reactions to the dye. The incidence of post-operative complications was observed to be zero in their length of stay spanning an average of 02 days (1–3 days).

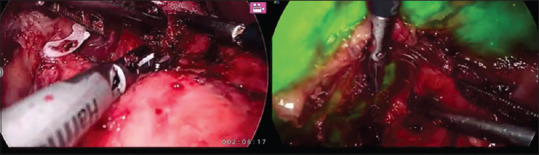

Before the dissection of Calot’s triangle, use of ICG for fluorescence imaging allowed visualisation of 1 structure in 94.4% of the cases [Figure 4]. Overall, the cystic duct was visualised in 86.6% of patients, the common bile and hepatic duct was visualised in 34.4% of patients, the junction between common bile and hepatic duct was visualised in 11.1% of patients. After the dissection of Calot’s triangle, use of ICG for fluorescence imaging allowed visualisation of 1 structure in 100% of cases. Overall, the cystic duct was visualised in 87.7% of patients, the common bile and hepatic duct were visualised in 94.4% of patients, the junction between common bile and hepatic duct was visualised in 80% of patients and right and left hepatic duct was visualised in 14.4% of patients. All four structures were visualized in 13.3% of patients. Before the injection of ICG dye, only in 11.1% of the cases 3 more structures were visualised. After introduction of ICG dye, 3 or more structures were visualised in 80% cases.

Figure 4.

View of anatomy following cystic duct in the fluorescence mode

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study confirms the superior efficacy of NIRFC using ICG in laparoscopic cholecystectomies. In 12 cases, all four structures were recognised after ICG injection. In 80% cases, 3 structures were recognised after the dissection of Calot’s triangle and administering intravenous ICG. ICG administration is found to be well-tolerated and safe with no allergic reactions reported during the present study. These results align with the conclusions from the previous studies. The recognition of biliary structures is an important step during the dissection of Calot’s triangle. The use of ICG coupled with a near-infrared camera for laparoscopic surgeries has the benefit of being a non-ionising method to better understand the biliary anatomy and avoid injuries. The dye is injected before the surgery, and the structures are visualised with the help of a camera. Furthermore, a surgeon can easily toggle between the normal and infrared modes of the camera. Since the biliary anatomy is visualised again after the dissection of the Calot’s triangle, it provides significant evidence on the efficacy of NIRFC with ICG for understanding biliary anatomy. The procedure was able to identify at least 1 structure in 100% of patients and all 4 anatomical structures in 13.3% of patients. There were no injuries or complications reported during the procedure, and the ICG was well tolerated in all patients. A study by Ishizawa et al. on 52 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy reported a 100% successful visualisation of the cystic duct with ICG fluorescent cholangiography. Our study supports the findings that in 87.7% of patients, the cystic duct was visualised with the use of ICG.

ICG fluorescent cholangiography in laparoscopic cholecystectomy has proven to be a very useful tool for real-time biliary imaging. The only demerit associated with the use of ICG is its inability to detect common bile duct stones. Due to its proven benefits and very low adverse effects, the use of ICG fluorescent imaging is an important method to study biliary anatomy. It can become a standard practice for cholecystectomies as it gives a surgeon the confidence to distinguish biliary structures with the help of fluorescent light.

CONCLUSION

Constant efforts are made to improve the outcomes of laparoscopic cholecystectomies as it is one of the most common surgeries performed for gallstone treatment. Introduction of ICG in NIRFC aims to increase the visualisation and reduce the injuries associated with this procedure. During the surgery, operating the camera and switching the mode from normal to fluorescent is easy, thereby helping in contrasting procedure. This enables the surgeon to visualise the operating field effectively and minimize injury to the gallbladder and structures in its surrounding. We found the use of ICG in NIRFC for laparoscopic cholecystectomies to be more efficient for visualising biliary duct anatomy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hassler KR, Collins JT, Philip K, Jones MW. In:StatPearls Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. [[Last updated on 2021 Apr 21]]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448145/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daskalaki D, Fernandes E, Wang X, Bianco FM, Elli EF, Ayloo S, et al. Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescent cholangiography during robotic cholecystectomy:Results of 184 consecutive cases in a single institution. Surg Innov. 2014;21:615–21. doi: 10.1177/1553350614524839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreuder AM, Busch OR, Besselink MG, Ignatavicius P, Gulbinas A, Barauskas G, et al. Long-term impact of iatrogenic bile duct injury. Dig Surg. 2020;37:10–21. doi: 10.1159/000496432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renz BW, Bösch F, Angele MK. Bile duct injury after cholecystectomy:Surgical therapy. Visc Med. 2017;33:184–90. doi: 10.1159/000471818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hope WW, Fanelli R, Walsh DS, Narula VK, Price R, Stefanidis D, et al. SAGES clinical spotlight review:Intraoperative cholangiography. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2007–16. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaltenthaler EC, Walters SJ, Chilcott J, Blakeborough A, Vergel YB, Thomas S. MRCP compared to diagnostic ERCP for diagnosis when biliary obstruction is suspected:A systematic review. BMC Med Imaging. 2006;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong G, Smith A, Toogood G. An overview of near infrared fluorescent cholangiography with indocyanine green during cholecystectomy. J Surg Transplant Sci. 2017;5:1051. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Peng W, Yang J, Li Y, Yang J, Hu X, et al. Application of near-infrared fluorescent cholangiography using indocyanine green in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:1–10. doi: 10.1177/0300060520979224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchs NC, Hagen ME, Pugin F, Volonte F, Bucher P, Schiffer E, et al. Intra-operative fluorescent cholangiography using indocyanin green during robotic single site cholecystectomy. Int J Med Robot. 2012;8:436–40. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]