Abstract

Background

The term potentially inadequate medication (PIM) is used to describe substances that may be unsuitable for use in the elderly and should be avoided. The PRISCUS list, published in 2010, was the first catalog of PIM designed for the German drug market to become adopted in practice. While 24% of German patients aged ≥ 65 years were prescribed at least one PIM per year in 2009, the proportion in 2019 was only 14.5%.

Methods

In a three-round Delphi process, experts from clinical practice and research evaluated whether selected substances are PIM for the elderly. The participants were provided with dedicated literature including systematic reviews carried out for the particular purposes of this project.

Results

Fifty-nine persons took part in the Delphi process and, in addition, contributed comments and therapeutic alternatives. Altogether, 187 substances were classed as PIM. One hundred thirty-three of the substances now listed were not in the original PRISCUS list: these include some oral antidiabetics, all of the selective COX-2 inhibitors, and moderately long acting benzodiazepines such as oxazepam. For some other substances, e.g., proton pump inhibitors (PPI), the advisability of treatment for more than 8 weeks was considered as potentially inappropriate, as was the use of ibuprofen in doses >1200 mg/day and for more than 1 week without PPI. Risperidone for more than 6 weeks is also PIM.

Conclusion

The new, greatly extended PRISCUS list must now be validated in epidemiological and prospective studies and its practicability in routine daily use must be verified.

Pharmacotherapy in the elderly has recently been addressed in national guidelines (1, 2). Along with attention to numerous factors such as patient preferences, compliance, and interactions, drug safety in old age can also be enhanced by avoidance of potentially inadequate medications (PIM). Many medications cause more—and sometimes different—side effects in the elderly than in younger patients, so the benefit–risk ratio may change. The substances primarily concerned are those that bring about dizziness or a rapid decrease in blood pressure, impair cognition, or increase the danger of falls (3, 4).

The PRISCUS list (Latin priscus: old, venerable) for the German drug market was published in 2010 (5) and has since found its way into textbooks and prescription software. Numerous studies have shown the association between the intake of PIM on the PRISCUS list and adverse drug events (ADE), in particular an elevated risk of hospital admission (6– 8).

One challenge in evaluating the safety and tolerability of drugs in old age is the frequent lack of data from clinical research (9). For this reason, PIM lists are compiled by experts, usually in a Delphi process (5).

Nevertheless, it is advisable to substantiate an expert survey with the best available evidence. For an update of the PRISCUS list, additional systematic reviews should therefore be performed and existing reviews should be processed and presented to experts as the basis for maximally evidence-based decisions. The PRISCUS list is also in urgent need of updating because of the changes in the drugs market since 2010.

Method

In order to facilitate preparation of a list of substances and substance classes for evaluation, the literature was searched for international PIM lists published since 2010 and a systematic literature review was conducted (eBox 1a). To narrow down the substances for assessment, prescription data from the statutory health insurance funds in Germany and Austria were analyzed, as a joint PRISCUS 2.0 list was to be compiled for use in both countries.

eBox 1. Method.

a) Compilation of the list of substances and substance classes to be evaluated

Literature search (PubMed, hand search of articles identified) for international PIM lists published since 2010

Systematic literature review to identify systematic reviews on adverse drug events (ADE) in elderly patients

Analysis of the German statutory health insurance funds’ prescription data from the year 2018 in patients aged ≥ 65 years

The prescription data of the statutory health insurance funds in Austria

→ Definition of the substances and substance classes to be evaluated

b) Pre-Delphi

Because finite time and resources meant that systematic reviews could not be carried out for all substances, an exploratory pre-Delphi process was conducted with four experts (specialties: clinical pharmacology, clinical care research, and clinical pharmacy). This served to assess whether the information from Micromedex and, if required, other sources (e.g., the summary of product characteristics) would suffice for evaluation of the substances without systematic review. To this end, the following questions were posed:

Is evaluation of this substance/class of substances feasible on the basis of data from Micromedex or the summary of product characteristics?

Is evaluation of this substance/class of substances feasible on the basis of the fact that it is included in one or more international PIM lists?

Is a literature review necessary for this substance/class of substances?

It emerged that an additional literature review was necessary for only four of the substances/categories examined: aluminum-containing antacids, sucralfate, butylscopolamine, and loratadine/desloratadine. Rapid reviews were planned for these substances/categories but could not be conducted owing to the resource-intensive systematic reviews. The latter were prioritized because of their higher evidential value.

c) Evidence generation and presentation of the information for the experts in the Delphi process

Sources of information for the suggested substances in the Delphi process

Data extracted from international PIM lists with the reasons given there for classification as PIM

Data extracted from Micromedex, or alternatively from the summary of product characteristics if there is no Micromedex entry for the substance concerned

Further literature from the original PRISCUS project

The modified version of the GRADE (15, 16) summary of findings (SOF) and evidence profile tables

The anticholinergic burden according to Kiesel et al. (e35)

Information on dosage and treatment duration in the elderly from the summary of product characteristics (included from the second Delphi round onwards, because many participants referred to this in their evaluation)

Literature mentioned by the participants (from the second Delphi round onwards)

Moreover, substances were prioritized for analysis in systematic reviews on the basis of prescription frequency. We were also able to take advantage of existing reviews from the PRIMA-eDS study (an EU project; for details see www.prima-eds.eu) (9– 13). Additionally, an exploratory survey was carried out to establish whether, for the remaining substances, information from other sources was sufficient for assessment by the participants (pre-Delphi; eBox 1b). The processing of the reviews’ findings was oriented on the standards for clinical practice guidelines (14– 16). A detailed description can be found in eBox 1. Furthermore, the experts had access to a collection of literature with complete texts and abstracts from publications cited in Micromedex (17), for example, and the other publications used (eBox 1c).

The substances were evaluated on a consensus basis over a three-round Delphi process (18, 19). For this purpose, persons with expertise in geriatric pharmacotherapy were identified (professional bodies, the Drug Commission of the German Medical Association, participants in the compilation of the original PRISCUS list [5] and the Austrian PIM list [e1]) and invited to take part. The participants evaluated the substances on a five-point Likert scale, from from 1 = potentially inappropriate (= PIM) to 5 (definitely not a PIM) (eBox 2a). The rating method is explained in eBox 2b.

eBox 2. Delphi process.

a) Rating of the substances on the Likert scale

“This substance/class of substances constitutes potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) for elderly patients and therefore should be avoided in this population”

1 – I strongly agree (that this substance is a PIM)

2 – I agree (that this substance is a PIM)

3 – Neutral (I neither agree nor disagree that this substance is a PIM)

4 – I disagree (that this substance is a PIM)

5 – I strongly disagree (that this substance is a PIM)

0 – No response/abstention*

*Served to mark an abstention and was not included in statistical analysis.

b) Classification of substances as PIM/non-PIM or ambiguous

A substance was rated to be definitely a PIM if the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of all evaluations was < 3 and definitely a non-PIM if the 95% CI of all evaluations was > 3. If the 95% CI included 3, the substance was considered to be ambiguously rated and thus a questionable PIM. The confidence intervals were calculated with Excel.

c) Feedback from the first Delphi round

Feedback for the participants in the second Delphi round

-

List of suggestions

Median, mean, and 95% confidence interval from the first round

Summary of the participants’ comments from the first round

PDF with list of substances definitely rated as PIM

PDF with list of substances definitely rated as non-PIM

In addition to their ratings on the Likert scale, the participants were asked, if possible, to give the following information:

Dose or time limit(s) from which the substance is a PIM

More appropriate alternatives

Monitoring of the effects if the substance is used

Contraindicating comedication and comorbidities

Any other comments

The participants also had the opportunity to suggest other substances for evaluation.

The results of the first Delphi round were provided to the participants as feedback (eBox 2c). Substances that were not rated unambiguously in the first round and those for which discrepancies emerged between expert evaluation and systematic reviews had to be evaluated anew in the second round. Based on the participants’ comments, some substances were evaluated in different doses and durations of use. In addition to the two Delphi rounds originally scheduled, a third round focused on one topic was added, because of inconsistencies between the evaluations and the participants’ comments with regard to the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID).

The results were available for (professional) public comment on the project website for 4 weeks in March 2021. Finally, all comments were summarized and incorporated into the complete version of PRISCUS 2.0.

Results

We identified 24 articles that listed PIM in the elderly (5, e1– e23) and eight relevant systematic reviews on ADE in older patients (20– 27). Evaluation of the international PIM lists, the prescription data of the German National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Fund (GKV), and the substances available for use in Austria resulted in identification of a total of 250 substances and substance classes to be considered for addition to the update of the PRISCUS list. No further substances were revealed by scrutiny of the identified systematic reviews.

Thirteen systematic reviews were carried out to provide evidence backing up the suggested additions for the update of the PRISCUS list. An overview of these reviews and their roles in the project can be found in eTable 1. Altogether, 21 GRADE summary of findings (SOF) and evidence profile tables for the results of the new and identified reviews were compiled. An example of the selected presentation can be found in Table 1.

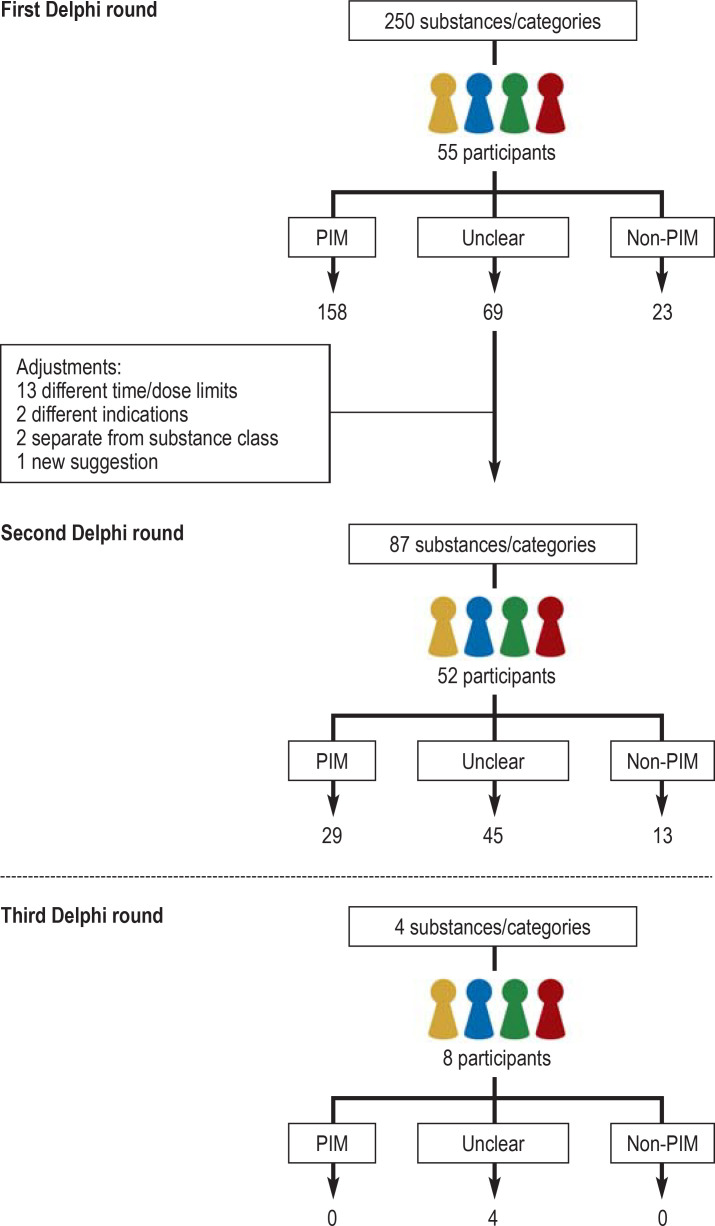

Of 101 persons contacted with regard to the Delphi process, 70 signed a declaration that they would participate. Fifty-five persons took part in the first round, 52 in the second round, and eight in the third round. Overall 59 persons took part in at least one Delphi round, representing a broad spectrum of medical specialties (including general medicine, geriatrics, clinical pharmacy, psychiatry, internal medicine, palliative medicine, clinical pharmacology, and cardiology). The distribution of the participants across the three rounds of the Delphi process is visualized in the eFigure.

The three-round Delphi process began in March 2020. Of the 250 substances/substance classes evaluated in the first round, 158 were rated as PIM and 23 as non-PIM. On the basis of the expert comments, 13 substances were differentiated in terms of time/dose limits, two according to indication, one substance was added to the list, and two substances were reconsidered in their own right rather than as part of their class. Thus a total of 87 substances were put forward for assessment in the second Delphi round, 29 of which were classified as PIM and 13 as non-PIM. There was still no unambiguous rating for 45 substances. In a third Delphi round, none of the four substances evaluated were unambiguously classified as PIM or non-PIM. Over the course of the Delphi process, therefore, 187 substances were rated as PIM, 36 as non-PIM, and the classification of 49 substances was ambiguous, i.e., they may be PIM (etable 4). The Delphi process is portrayed in the eFigure.

eTable 4. Substances that were classified neither as PIM nor as non-PIM.

| Substance/class of substances | No. of evaluations | Median | Mean | [95% CI] |

| Drugs for acidity-related diseases | ||||

| Famotidine | 43 | 3 | 2.81 | [2.56; 3.07] |

| Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders | ||||

| Butylscopolamine | 47 | 3 | 3.00 | [2.71; 3.29] |

| Drugs for constipation | ||||

| Bisacodyl > 10 mg/d, > 1 week | 41 | 2 | 2.71 | [2.37; 3.05] |

| Sennosides | 43 | 3 | 2.77 | [2.46; 3.07] |

| Sodium picosulfate | 42 | 3 | 3.14 | [2.87; 3.41] |

| Prucalopride | 33 | 3 | 3.03 | [2.68; 3.38] |

| Antidiarrhea drugs and intestinal anti-inflammatories/anti-infectives | ||||

| Racecadotril | 30 | 3 | 3.10 | [2.72; 3.48] |

| Antithrombotic drugs | ||||

| Dabigatran etexilate | 47 | 3 | 3.13 | [2.78; 3.47] |

| Cardiac treatment | ||||

| Digitoxin | 47 | 3 | 3.00 | [2.66; 3.34] |

| Amiodarone | 47 | 3 | 2.96 | [2.64; 3.28] |

| Vernakalant | 30 | 3 | 3.20 | [2.84; 3.56] |

| Ranolazine | 38 | 3 | 3.03 | [2.66; 3.39] |

| Antihypertensives | ||||

| Urapidil | 46 | 3 | 2.89 | [2.55; 3.24] |

| Potassium-sparing drugs | ||||

| Eplerenone > 25 mg/d | 39 | 3 | 2.77 | [2.47; 3.07] |

| Amiloride or compounds containing triamterene | 44 | 3 | 2.89 | [2.59; 3.18] |

| Beta-adrenoceptor antagonists | ||||

| Atenolol | 45 | 3 | 2.80 | [2.51; 3.09] |

| Calcium-channel blockers | ||||

| Slow-release nifedipine | 42 | 3 | 2.88 | [2.60; 3.17] |

| Selective calcium-channel blockers with predominantly cardiac action (verapamil, diltiazem) | 46 | 3 | 3.04 | [2.81; 3.28] |

| Sexual hormones and modulators of the genital system | ||||

| Raloxifene | 41 | 3 | 3.07 | [2.81; 3.33] |

| Urologics | ||||

| Alfuzosin | 43 | 3 | 3.12 | [2.85; 3.38] |

| Terazosin | 43 | 3 | 2.95 | [2.68; 3.23] |

| Silodosin | 39 | 3 | 3.03 | [2.75; 3.30] |

| Antibiotics for systemic use | ||||

| Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim | 48 | 3 | 2.79 | [2.52; 3.06] |

| Nitrofurantoin | 48 | 3 | 2.83 | [2.53; 3.13] |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic drugs | ||||

| Ibuprofen up to max. 3 × 400 mg/d, for max. 1 week | 7 | 4 | 3.43 | [2.53; 4.33] |

| Ibuprofen up to max. 3 × 400 mg/d, with PPI for max. 8 weeks | 5 | 4 | 3.60 | [2.49; 4.71] |

| Naproxen up to max. 2 × 250 mg/d, for max. 1 week | 6 | 4 | 3.67 | [2.81; 4.52] |

| Naproxen up to max. 2 × 250 mg/d, with PPI for max. 8 weeks | 7 | 4 | 3.43 | [2.53; 4.33] |

| Drugs for gout | ||||

| Colchicine | 45 | 3 | 2.76 | [2.46; 3.05] |

| Analgesics | ||||

| Selective serotonin-5HT-1 receptor agonists/ triptans (sumatriptan, naratriptan, zolmitriptan, rizatriptan, almotriptan, eletriptan, frovatriptan) | 43 | 3 | 2.86 | [2.57; 3.15] |

| Antiepileptics | ||||

| Topiramate | 40 | 3 | 2.90 | [2.66; 3.14] |

| Pregabalin | 43 | 3 | 2.88 | [2.55; 3.21] |

| Drugs for Parkinson’s disease | ||||

| Ropinirole | 40 | 3 | 2.80 | [2.49; 3.11] |

| Rotigotine | 36 | 3 | 2.75 | [2.44; 3.06] |

| Entacapone | 35 | 3 | 3.09 | [2.82; 3.35] |

| Opicapone | 34 | 3 | 2.91 | [2.66; 3.16] |

| Antipsychotics | ||||

| Melperone | 46 | 3 | 3.07 | [2.76; 3.37] |

| Pipamperone | 40 | 3 | 3.15 | [2.83; 3.47] |

| Quetiapine | 46 | 3 | 3.04 | [2.75; 3.34 |

| Lithium | 43 | 3 | 3.05 | [2.74; 3.35] |

| Antidepressants | ||||

| Trazodone | 45 | 3 | 2.84 | [2.59; 3.10] |

| Venlafaxine | 44 | 3 | 3.00 | [2.74; 3.26] |

| Milnacipran | 28 | 3 | 2.96 | [2.62; 3.31] |

| Duloxetine | 43 | 3 | 2.98 | [2.66; 3.30] |

| Drugs for obstructive respiratory tract diseases | ||||

| Ipratropium bromide | 42 | 4 | 3.29 | [2.97; 3.60] |

| Cough and cold remedies | ||||

| Noscapine | 39 | 3 | 3.15 | [2.85; 3.46] |

| Antihistamines for systemic use | ||||

| Second generation | ||||

| Mizolastine | 28 | 3 | 2.71 | [2.40; 3.03] |

| Fexofenadine | 32 | 3 | 2.84 | [2.53; 3.16] |

| Bilastine | 29 | 3 | 2.83 | [2.49; 3.17] |

*These substances are marketed only in Austria, not in Germany.

PPI, Proton pump inhibitors

In addition to the median, mean, and 95% confidence interval, the detailed version of PRISCUS 2.0 contains the following details on each substance:

Possible alternatives

Information about monitoring

Comedication/comorbidities to be avoided

Reason for classification as PIM

Discussion points

Substances that are no longer marketed in Germany or are not eligible for prescription are listed separately. This version is available on the project website (www.priscus2-0.de). PRISCUS 2.0 contains 177 substances/substance classes (Table 2, eTable 2).

Table 2. PRISCUS 2.0, short version.

| Substance/class | Possible alternatives depending on indication (expert opinion) |

| Drugs for acid-related diseases | |

| Antacids containing magnesium > 4 weeks | Antacids containing alginate PPI < 8 weeks |

| Compounds containing aluminum | Antacids containing alginate PPI < 8 weeks |

| Cimetidine, ranitidine*1 | PPI < 8 weeks when indicated, famotidine |

| Proton pump inhibitors > 8 weeks | PPI < 8 weeks when indicated, famotidine |

| Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders | |

| Mebeverine | E.g., psyllium, non-pharmacological |

| Metoclopramide, domperidone | E.g., setrons, herbal preparations |

| Alizapride | |

| Antiemetics and drugs for nausea | |

| Dimenhydrinate | E.g., setrons, herbal preparations |

| Scopolamine | E.g., corticosteroids, setrons |

| Drugs for constipation | |

| Liquid paraffin | E.g., macrogol, psyllium |

| Sennosides > 1 week | E.g., sennosides < 1 week, macrogol |

| Sodium picosulfate > 1 week | E.g., sodium picosulfate < 1 week, macrogol |

| Antipropulsives | |

| Loperamide > 3 d, > 12 mg/d | E.g., loperamide < 3 d, < 12 mg/d, racecadotril |

| Antidiabetic drugs | |

| Glibenclamide, gliquidone, gliclazide, glimepiride | E.g., metformin, DPP-4 inhibitors |

| Acarbose | E.g., metformin, DPP-4 inhibitors |

| Pioglitazone | E.g., metformin, DPP-4 inhibitors |

| Antithrombotic drugs | |

| Ticlopidine, prasugrel | E.g., clopidogrel, ASA |

| Cardiac treatment | |

| Digoxin and derivatives | E.g., beta-blockers, digitoxin |

| Lidocaine | E.g., beta-blockers, when indicated amiodarone |

| Propafenone as long-term medication | E.g., beta-blockers, when indicated amiodarone |

| Flecainide | Beta-blockers, when indicated amiodarone |

| Dronedarone | E.g., beta-blockers, when indicated amiodarone |

| Antihypertensives | |

| Methyldopa, clonidine, moxonidine | E.g., ACE inhibitors, other antihypertensives |

| Doxazosin | E.g., ACE inhibitors, other antihypertensives |

| Terazosin as antihypertensive | ACE inhibitors, other antihypertensives |

| Dihydralazine, hydralazine*2 | E.g., ACE inhibitors, other antihypertensives |

| Minoxidil | E.g., ACE inhibitors, other antihypertensives |

| Potassium-sparing drugs | |

| Spironolactone > 25 mg/d | E.g., spironolactone ≤ 25 mg/d |

| Peripheral vasodilators | |

| Pentoxifylline | E.g., memantine, ASA, memory/walking training |

| Naftidrofuryl, cilostazol | E.g., walking training, ASA |

| Beta-adrenoceptor antagonists | |

| Pindolol, propranolol, sotalol | Others (selective beta-blockers) |

| Calcium-channel blockers | |

| Non-slow-release nifedipine | E.g., long-acting calcium antagonists |

| Drugs acting on the renin–angiotensin system | |

| Aliskiren | ACE inhibitors, sartans |

| Sexual hormones and modulators of the genital system | |

| Testosterone | |

| Oral estrogens | Vaginal estrogens, black cohosh |

| Urologics | |

| Flavoxate | E.g., pelvic floor training, bladder training |

| Oxybutynin, propiverine, tolterodine, solifenacin, trospium, darifenacin, fesoterodine, desfesoterodine | Non-pharmacological |

| Mirabegron | Non-pharmacological |

| Hypophyseal and hypothalamic hormones and analogs | |

| Desmopressin | Tamsulosin, vaginal estrogens |

| Antibiotics for systemic use | |

| Fluoroquinolones | Depending on antibiogram |

| Endocrine treatment | |

| Medroxyprogesterone | Tamoxifen, fulvestrant, vaginal estrogens |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic drugs | |

| Phenylbutazone | E.g., topical agents, paracetamol |

| Indomethacin, diclofenac, acemetacin, proglumetacin, aceclofenac | E.g., topical agents, paracetamol |

| Piroxicam, meloxicam | E.g., topical agents, paracetamol |

| Ibuprofen > 3 × 400 mg/d, > 1 week or > 3 × 400 mg/d, with PPI > 8 weeks | E.g., ibuprofen ≤ 3 × 400 mg/d, ≤ 1 week, with PPI ≤ 8 weeks |

| Naproxen > 2 × 250 mg/d, > 1 week or > 2 × 250 mg/d, with PPI > 8 weeks | E.g., naproxen ≤ 2 × 250 mg/d, ≤ 1 week, with PPI ≤ 8 weeks |

| Ketoprofen, dexketoprofen | E.g., topical agents, paracetamol |

| Etofenamate | E.g., topical agents, paracetamol |

| Coxibs | E.g., topical agents, paracetamol |

| Nabumetone | E.g., topical agents, paracetamol |

| Muscle relaxants | |

| Methocarbamol, orphenadrine (citrate), baclofen, tizanidine | E.g., Paracetamol, tilidine |

| Pridinol | |

| Tolperisone | Paracetamol, metamizole |

| Other drugs for disorders of the musculoskeletal system | |

| Quinine | E.g., stretching exercises, magnesium < 4 weeks |

| Analgesics | |

| Dihydrocodeine, codeine as analgesic | |

| Pethidine, tapentadol, tramadol | E.g., tilidine, other opioids |

| Methadone, levomethadone | Other opioids |

| Acetylsalicylic acid as analgesic | E.g., paracetamol |

| Phenazone, propyphenazone | E.g., paracetamol |

| Ergotamine | Triptans, paracetamol |

| Antiepileptics | |

| Phenobarbital, primidone, phenytoin, carbamazepine | E.g., lamotrigine, valproate |

| Drugs for Parkinson’s disease | |

| Trihexyphenidyl, biperiden, procyclidine, bornaprine | E.g., levodopa, ropinirole |

| Amantadine | E.g., levodopa, ropinirole |

| Pramipexole, piribedil | E.g., levodopa, ropinirole |

| Dopaminergic ergot alkaloids (e.g., pergolide) | E.g., levodopa, ropinirole |

| Monoaminoxidase-B inhibitors (e.g., selegiline) | E.g., levodopa, ropinirole |

| Tolcapone | Entacapone, when indicated opicapone |

| Antipsychotics | |

| Levomepromazine, perazine, thioridazine, chlorprothixene, zuclopenthixol, prothipendyl | E.g., risperidone < 6 weeks |

| Fluphenazine, perphenazine, haloperidol, benperidol, bromperidol, flupentixol, fluspirilene, pimozide | E.g., risperidone < 6 weeks |

| Melperone > 100 mg/d, > 6 weeks | E.g., melperone < 100 mg/d, < 6 weeks |

| Pipamperone > 120 mg/d, > 6 weeks | E.g., pipamperone < 120 mg/d, < 6 weeks |

| Ziprasidone, clozapine, olanzapine, sulpiride, amisulpride, tiapride, aripiprazole, sertindole, paliperidone, cariprazine | E.g., risperidone < 6 weeks |

| Quetiapine > 100 mg/d, > 6 weeks | E.g., quetiapine < 100 mg/d, < 6 weeks |

| Risperidone > 6 weeks | E.g., risperidone < 6 weeks |

| Anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives | |

| Hydroxyzine | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine |

| Long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam) | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine |

| Lorazepam | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine, valerian |

| Moderately long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., oxazepam) | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine, valerian |

| Short-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., triazolam) | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine, valerian |

| Chloral hydrate | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine, valerian |

| Zopiclone, zolpidem | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine, valerian |

| Clomethiazole | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine |

| Doxylamine | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine, valerian |

| Promethazine | E.g., melatonin, mirtazapine, valerian |

| Antidepressants | |

| Tricyclics (e.g., amitriptyline), nortriptyline*3 | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Opipramol | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Doxepin | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Maprotiline, mianserin | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Sertraline > 100 mg/d | E.g., sertraline < 100 mg/d |

| Tranylcypromine, moclobemide | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| St John’s wort | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Bupropion | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Tianeptine | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Agomelatine | E.g., citalopram, mirtazapine |

| Psychostimulants | |

| Methylphenidate | |

| Pyritinol | E.g., memantine |

| Piracetam | E.g., memantine |

| Anti-dementia drugs | |

| Ginkgo leaf | E.g., memantine |

| Nicergoline | E.g., memantine |

| Nimodipine | E.g., memantine, amlodipine |

| Drugs for vertigo | |

| Betahistine | See long version |

| Cinnarizine*4, flunarizine | See long version |

| Drugs for obstructive respiratory tract diseases | |

| Sympathomimetics for systemic use, no inhalation (e.g., salbumatol) | Inhaled sympathomimetics |

| Theophylline, aminophylline | Inhaled salbutamol LABA, LAMA, ICS |

| Cough and cold remedies | |

| Codeine, dihydrocodeine as antitussive | E.g., phytopharmaceuticals, DMP |

| Antihistamines for systemic use | |

| First generation | |

| Diphenhydramine, clemastine, dimetindene, cyproheptadine, ketotifen | E.g., cetirizine, topical agents |

| Second generation | |

| Ebastine, rupatadine | E.g., cetirizine, loratadine |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; DMP, dextromethorphan; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta-2 sympathomimetics; LAMA long-acting muscarine antagonists; PPI, Proton pump inhibitors

*1 License suspended since January 2021 owing to nitrosamine contamination

*2 In Germany: only as a compound with atenolol and chlorthalidone

*3 According to comments, nortriptyline is tolerated better than other tricyclics; therefore, it was evaluated in its own right in the second round of the Delphi process

*4 In Germany: only as a compound with dimenhydrinate

Six substances in the original PRISCUS list were not suggested for inclusion in PRISCUS 2.0, either because they were no longer marketed (e.g., zaleplon) or because, going by the GKV prescription data, their prescription to patients aged 65 years or over had decreased to a very low level (e.g., triprolidine). Nitrofurantoin, in contrast to the original list, was no longer classified as a definite PIM. A total of 133 substances were newly classified as PIM; nine of these, however, are currently not on the market (e.g., rilmenidine) or not eligible for prescription (e.g., reboxetine).

Discussion

PRISCUS 2.0, with 177 substances listed, is more than twice as long as the original PRISCUS list. In several cases (e.g., neuroleptics and NSAID), the individual substances are listed separately rather than the substance class as a whole, in order to take account of possible differences among the substances. For some indications, such as diabetes mellitus, there was previously only one single substance listed; now numerous others have been added, not only for diabetes but also in the categories of beta-blockers, muscle relaxants, and drugs for use against Parkinson’s disease.

The need to update lists of PIM regularly because recommendations for the use of certain substances change over time can be illustrated by the example of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC). We conducted a systematic review specifically to clarify the safety of DOAC in the elderly. Although DOAC were not evaluated at all for the first PRISCUS list, they were classified as PIM in the EU(7) list published in 2015 (e2). In the PRISCUS 2.0 process, however, they were rated as non-PIM, with the exception of dabigatran, which was categorized as a possible PIM. In the current version of the Beers list, dabigatran and rivaroxaban are mentioned as substances that should be used with caution in the elderly (e3).

In comparison with the LUTS-FORTA list (e18), it is striking that the alpha-blockers used in urology are rated in PRISCUS 2.0 as unclear (e.g., terazosin) or as non-PIM (tamsulosin), whereas LUTS-FORTA classifies them as “use with caution” (C) or “avoid” (D). A systematic review of the safety of alpha-blockers in the elderly carried out specifically for PRISCUS 2.0 did not lead to any of them being classified as PIM (28). While oral antidiabetics such as glibenclamide, glimepiride, and acarbose were categorized as PIM, the FORTA list differentiates them: glibenclamide is classified as D, glimepiride and acarbose as C. This difference is reflected somewhat in the much lower mean rating for glibenclamide than for the other substances.

Taken together, these examples clearly illustrate the discrepancies among different lists of PIM. On the one hand, this is due to the changes in available evidence over time and the different publication times of the individual lists. On the other hand, it must be remembered that the classifications of the substances considered depend on the ratings assigned by the experts involved in the process. Differences in classification of individual substances between PIM lists may be attributable to the compositions of the groups of experts recruited.

When compiling PIM lists, other lists are often used as data sources (29). In this respect, our systematic research and the development of an adapted GRADE procedure (16) represent a considerable step forward in methodology. FORTA classifies DPP-4 inhibitors as A (absolutely suitable), whereas the systematic review conducted for PRISCUS 2.0 revealed evidence of a possible elevation in mortality risk and a slightly increased risk of hypoglycemia compared with the standard treatment; however, DPP-4 were definitely superior to the sulfonylureas (30). Nevertheless, overall this class of substances was not categorized as PIM.

Since the publication of the PRISCUS list in 2010, lists of PIM have been compiled in many other countries (29). A number of studies have shown that intake of PIM is associated with adverse effects (6– 8). Although there is not yet any evidence to show that discontinuation of PIM leads to reduction of morbidity and mortality (31), some analyses show a decline in the prescription of PIM in Germany (32).

Limitations

Restricting the list of substances suggested for PRISCUS 2.0 to those found in the GKV prescription data means that substances which can be obtained without prescription or are not eligible for prescription were not considered sufficiently. One example is the antihistamine triprolidine.

It remains the case that elderly persons are often excluded from clinical trials, leading to paucity of data (33). For reasons of time and resources, we were able to conduct systematic reviews only for certain substances, so that data on the remainder were limited to the findings of non-systematic research. In contrast to the original intention, some of the systematic reviews were completed only in time for the second round of the Delphi process.

The third Delphi round, focusing on NSAID, featured fewer participants than the previous rounds. It is possible that the results of the third round would have been different if a higher number of experts had taken part. In view of the participants’ comments on which the third Delphi round was based, however, this is unlikely.

PIM lists specify substances that may not be suitable for use in the elderly. Prescription of a PIM may still be necessary in an individual patient, however, so the presence of a substance on a PIM list is not equivalent to a universally valid negative rating or prohibition. Individual assessment of each patient’s clinical situation and the resulting choice of appropriate medication is and will remain a central task for the treating physicians. Whether a given drug is suitable or otherwise for the person concerned can be decided only in the knowledge of the particular patient’s clinical situation, of which PRISCUS 2.0 takes no account. Although on the one hand this represents a crucial limitation, it means that PRISCUS 2.0 can also be used by persons with restricted access (or none at all) to clinical data, e.g., pharmacists, community carers, and relatives, to identify drugs that may not be appropriate. At various points in the medication process, therefore, it is possible to analyze—and potentially optimize—the patient’s pharmaceutical treatment in consultation and cooperation with the physicians involved. Furthermore, the PRISCUS list is useful for pharmacoepidemiological analyses in situations where clinical data are sparse (32, 34).

Table 1. GRADE summary of findings: PPI compared with no treatment in elderly patients.

| Outcomes |

Expected absolute effects*1

[95% CI] |

Relative effect

[95% CI] |

Number of participants

(studies) |

Certainty of evidence

(GRADE) |

|

| Risk without treatment | Risk with PPI | ||||

| GERD symptoms (e24) measured in terms of: frequency Observation period: mean 5 years |

44 (1 observational study) |

Very low*2 | |||

| ● Comment: PPI may reduce GERD symptoms in the elderly (MD 10.6 times less common per month), but the evidence is uncertain. | |||||

| Mortality (e25) measured in terms of: events Observation period: 1 year |

10 410 per 100 000 | 15 295 per 100 000 [10 705; 26 251] |

HR 1.51 [1.03; 2.77] |

491 (1 observational study) |

Low*3, *4, *5 |

| Hospitalization – not reported | – | – | |||

| Quality of life – not reported | – | – | |||

| Clostridium difficile diarrhea (e26, e27) | 233 per 1000 | 291 per 1000 [152; 485] |

OR 1.35 [0.59; 3.10] |

281 cases, 279 controls (2 observational studies) |

Low*6, *7 |

| Hip joint fracture after > 4 years of PPI treatment (e28) measured in terms of: events Exposure time: 1 year |

40 per 1000 | 62 per 1000 [0; 0] |

OR 1.59 [1.39; 1.80] |

13 556 cases, 135 386 controls (1 observational study) |

Moderate*5, *8 |

| ● Comment: Absolute numbers were not reported and were calculated by study staff. The OR was determined for multiple covariates. | |||||

| Pneumonia – not reported | – | – | |||

| Dementia (e29, e30) | 7789 per 100 000 | 14 267 per 100 000 [10 845; 18 572) |

RR 1.97 [1.44; 2.70] |

2666 (2 observational studies) |

Low*9 |

| ● Comment: Three studies were excluded from the meta-analysis because absolute numbers were not reported. One study found an elevated risk of dementia from PPI use (e31; HR 1.44; 95 % CI [1.36; 1.52]). One study found no difference between PPI users and non-users (e32; only p-value reported [p = 0.66]). One study found a lower risk of dementia in PPI users (e33; HR 0.78; 95% CI [0.66; 0.9]). | |||||

| Hospitalization owing to acute kidney injury (e34) |

2 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 [4; 5] |

HR 2.45 [2.21; 2.71] |

58 1184 (1 observational study) |

Low*5 |

*1 The risk in the intervention group and the 95% confidence interval are based on the assumed risk in the control group and the relative effect of the intervention (and the and the 95% confidence interval)

*2 Before and after study with no control group; *3 cohort study with incomplete follow-up; *4 only hospitalized patients; *5 only one study;

*6 contradictory results in two studies;

*7 large 95% confidence interval, including a considerable positive benefit/risk ratio;

*8 case–control study;

*9 high risk of bias in individual studies

GRADE Working Group levels of evidence

High certainty: Considerable confidence that the true effect is similar to the estimated effect.

Moderate certainty: Moderate confidence in the effect estimator: the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect, but the possibility exists that it differs markedly.

Low certainty: Confidence in the effect estimator is limited: the true effect may be markedly different from the estimated effect.

Very low certainty: Confidence in the effect estimator is very low: the true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect.

CI, Confidence interval; GERD, gastro-esophageal reflux disease; HR, hazard ratio; MD, mean difference; OR, odds ratio; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; RR, relative risk

eFigure.

Delphi process

PIM, Potentially inappropriate medication

eTable 1. Overview of new and identified systematic reviews and GRADE tables.

| Review on | Firstround? | Second round? | GRADE table? | No. of GRADE tables | Place of entry in expert material |

| From: PIM Austria—project report | |||||

| PPI | No | Yes | Second round | 1 | A02BC PPI |

| Benzodiazepines | No | No | No | ||

| ● Comment: Irrelevant in second round due to lack of discrepancy between review and expert assessment | |||||

| Alpha blockers | No | Yes | Second round | 1 | G04CA alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists |

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances | |||||

| Ginkgo biloba | No | No | No | ||

| ● Comment: Irrelevant in second round due to lack of discrepancy between review and expert assessment | |||||

| Anticholinergic urologics and beta-3-adrenoceptor agonists | No | No | No | ||

| ● Comment: Irrelevant in second round due to lack of discrepancy between review and expert assessment | |||||

| Imidazoline receptor agonists | No | No | No | ||

| ● Comment: Irrelevant in second round due to lack of discrepancy between review and expert assessment | |||||

| Tramadol | No | Yes | Second round | 1 | N02AX02 Tramadol |

| Sulfonylureas | No | No | No | ||

| ● Comment: Irrelevant in second round due to lack of discrepancy between review and expert assessment | |||||

| Z substances | No | No | No | ||

| ● Comment: Irrelevant in second round due to lack of discrepancy between review and expert assessment | |||||

| Pregabalin | No | Yes | Second round | 1 | N03AX16 pregabalin |

| Aldosterone antagonists | No | Yes | Second round | 1 | C03DA aldosterone antagonists |

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances being evaluated | |||||

| From: generic review on aging | |||||

| Anabolic steroids after hip fracture | Yes | No | First round | 1 | G03BA03 testosterone |

| Second-generation antipsychotics: severe side effects | Yes | Yes | First round Second round |

1 | N05A antipsychotics |

| Second-generation antipsychotics: mortality | |||||

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances being evaluated | |||||

| Antibiotics in urinary tract infections | Yes | Yes | First round Second round |

1 | J01 antibiotics for systemic use |

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances being evaluated | |||||

| Laxatives and iatrogenic falls | Yes | Yes | First round Second round |

1 | A06A medications to treat constipation |

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances being evaluated | |||||

| Antihistamines and falls/fractures | Yes | Yes | First round Second round |

1 | R06A antihistamines for systemic use |

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances being evaluated | |||||

| Atypical antipsychotics BPSD | Yes (risperidone) |

Yes (risperidone) |

First round Second round |

1 | N05AX08 risperidone |

| Antidepressants in patients aged ≥ 65 years | Yes (duloxetine) |

Yes (duloxetine) |

First round Second round |

1 | N06AX21 duloxetine |

| From: PRIMA-eDS and update/new research | |||||

| DOAC | Yes (text form) |

No | No | B01AA vitamin-K antagonists | |

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances being evaluated | |||||

| DPP-4 | Yes (text form) |

Yes | Second round | 2 | A10BH DPP-4 inhibitors |

| ● Comment: Two GRADE PDFs, one for each control | |||||

| From: PRIMA-eDS | |||||

| Beta-blockers | Yes | Yes | First round Second round |

2 | C07A beta-blockers |

| ● Comment: Not entered for individual substances being evaluated Two GRADE PDFs, one for each control | |||||

| Metformin | Yes | No | First round | 5 | A10BA02 metformin |

| ● Comment: Five GRADE PDFs, one for each control | |||||

| Total | 21 | ||||

BPSD, Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulants; DPP-4, dipeptidylpeptidase-4; PPI, proton pump inhibitors

eTable 2. Substances classified as PIM (supplement to Table 2): number of ratings, mean, and confidence interval.

|

Substance/class

n = number of ratings |

Mean

[95% CI] |

| Drugs for acidity-related diseases | |

| Antacids containing magnesium > 4 weeks (n = 34) | 2.29 [2.00; 2.59] |

| Compounds containing aluminum (n = 43) | 2.60 [2.26; 2.95] |

| Cimetidine (n = 43) | 1.98 [1.72; 2.23] |

| Ranitidine*1 (n = 44) | 2.66 [2.35; 2.97] |

| Proton pump inhibitors > 8 weeks (n = 43) | 2.47 [2.16; 2.77] |

| Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders | |

| Mebeverine (n = 36) | 2.56 [2.24; 2.87] |

| Metoclopramide (n = 46) | 2.20 [1.90; 2.49] |

| Domperidone (n = 47) | 2.23 [1.95; 2.52] |

| Alizapride (n = 33) | 2.30 [1.97; 2.64] |

| Antiemetics and drugs for nausea | |

| Dimenhydrinate (n = 49) | 1.73 [1.44; 2.03] |

| Scopolamine (n = 48) | 1.65 [1.42; 1.87] |

| Drugs for constipation | |

| Liquid paraffin (n = 45) | 2.31 [1.93; 2.69] |

| Sennosides > 1 week (n = 42) | 1.95 [1.74; 2.17] |

| Sodium picosulfate > 1 week (n = 41) | 2.27 [2.01; 2.52] |

| Motility inhibitors | |

| Loperamide > 3 d > 12 mg/d (n = 42) | 2.02 [1.81; 2.24] |

| Antidiabetic drugs | |

| Glibenclamide (n = 46) | 2.00 [1.69; 2.31] |

| Gliquidone (n = 35) | 2.29 [1.91; 2.66] |

| Gliclazide (n = 37) | 2.27 [1.95; 2.59] |

| Glimepiride (n = 43) | 2.26 [1.95; 2.56] |

| Acarbose (n = 45) | 2.64 [2.32; 2.97] |

| Pioglitazone (n = 43) | 2.05 [1.73; 2.36] |

| Antithrombotic drugs | |

| Ticlopidine (n = 41) | 2.32 [2.01; 2.63] |

| Prasugrel (n = 42) | 2.64 [2.31; 2.98] |

| Cardiac treatment | |

| Digoxin and derivatives (n = 42) | 1.95 [1.69; 2.22] |

| Lidocaine (n = 45) | 2.51 [2.21; 2.82] |

| Propafenone as long-term medication (n = 43) | 2.53 [2.24; 2.83] |

| Flecainide (n = 40) | 2.38 [2.09; 2.66] |

| Dronedarone (n = 38) | 1.95 [1.63; 2.26] |

| Antihypertensives | |

| Methyldopa (n = 44) | 1.93 [1.59; 2.28] |

| Clonidine (n = 45) | 1.93 [1.69; 2.18] |

| Moxonidine (n = 40) | 2.03 [1.76; 2.29] |

| Doxazosin (n = 45) | 2.27 [1.98; 2.56] |

| Terazosin as antihypertensive (n = 40) | 2.30 [2.00; 2.60] |

| Dihydralazine (n = 21) | 2.24 [1.86; 2.62] |

| Hydralazine*2(n = 38) | 2.03 [1.76; 2.30] |

| Minoxidil (n = 41) | 2.29 [2.04; 2.55] |

| Potassium-sparing drugs | |

| Spironolactone > 25 mg/d (n = 43) | 2.51 [2.23; 2.79] |

| Peripheral vasodilators | |

| Pentoxifylline (n = 44) | 1.73 [1.48; 1.98] |

| Naftidrofuryl (n = 42) | 1.71 [1.46; 1.97] |

| Cilostazol (n = 34) | 2.26 [1.92; 2.61] |

| Beta-adrenoceptor antagonists | |

| Pindolol (n = 36) | 2.42 [2.07; 2.76] |

| Propranolol (n = 46) | 2.70 [2.47; 2.92] |

| Sotalol (n = 43) | 2.42 [2.09; 2.74] |

| Calcium-channel blockers | |

| Non-slow-release nifedipine (n = 42) | 1.88 [1.59; 2.17] |

| Drugs acting on the renin–angiotensin system | |

| Aliskiren (n = 41) | 2.66 [2.33; 2.99] |

| Sexual hormones and modulators of the genital system | |

| Testosterone (n = 42) | 2.24 [1.91; 2.57] |

| Oral estrogens (n = 41) | 2.17 [1.83; 2.51] |

| Urologics | |

| Flavoxate (n = 38) | 2.03 [1.80; 2.25] |

| Oxybutynin (n = 44) | 1.84 [1.61; 2.08] |

| Propiverine (n = 34) | 1.74 [1.54; 1.93] |

| Tolterodine (n = 39) | 2.03 [1.74; 2.31] |

| Solifenacin (n = 37) | 2.08 [1.80; 2.36] |

| Trospium (n = 44) | 2.36 [2.10; 2.63] |

| Darifenacin (n = 39) | 2.00 [1.71; 2.29] |

| Fesoterodine, desfesoterodine (n = 40) | 2.05 [1.77; 2.33] |

| Mirabegron (n = 37) | 2.62 [2.29; 2.95] |

| Hypophyseal and hypothalamic hormones and analogs | |

| Desmopressin (n = 39) | 2.51 [2.17; 2.86] |

| Antibiotics for systemic use | |

| Fluoroquinolones (n = 45) | 2.27 [1.98; 2.55] |

| Endocrine treatment | |

| Medroxyprogesterone (n = 38) | 2.42 [2.14; 2.70] |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic drugs | |

| Phenylbutazone (n = 45) | 1.38 [1.18; 1.57] |

| Indomethacin (n = 44) | 1.48 [1.26; 1.70] |

| Diclofenac (n = 45) | 1.96 [1.73; 2.18] |

| Acemetacin (n = 41) | 1.68 [1.42; 1.94] |

| Proglumetacin (n = 37) | 1.49 [1.22; 1.75] |

| Aceclofenac (n = 36) | 1.58 [1.34; 1.83] |

| Piroxicam (n = 47) | 1.62 [1.38; 1.85] |

| Meloxicam (n = 44) | 1.68 [1.45; 1.92] |

| Ibuprofen*3 > 3 × 400 mg/d, > 1 week or > 3 × 400 mg/d, with PPI > 8 weeks (n = 48) | 2.60 [2.30; 2.91] |

| Naproxen*3 > 2 × 250 mg/d, > 1 week or > 2 × 250 mg/d, with PPI > 8 weeks (n = 43) | 2.58 [2.26; 2.90] |

| Ketoprofen, dexketoprofen (n = 40) | 1.80 [1.51; 2.09] |

| Etofenamate (n = 34) | 1.82 [1.56; 2.09] |

| Coxibs (n = 42) | 2.07 [1.83; 2.31] |

| Nabumetone (n = 31) | 2.19 [1.77; 2.62] |

| Muscle relaxants | |

| Methocarbamol (n = 34) | 2.00 [1.64; 2.36] |

| Orphenadrine (citrate) (n = 40) | 1.78 [1.50; 2.05] |

| Baclofen (n = 47) | 2.19 [1.91; 2.48] |

| Tizanidine (n = 37) | 1.89 [1.59; 2.19] |

| Pridinol (n = 26) | 2.00 [1.64; 2.36] |

| Tolperisone (n = 32) | 2.16 [1.85; 2.46] |

| Other drugs for disorders of the musculoskeletal system | |

| Quinine (n = 43) | 1.77 [1.52; 2.02] |

| Analgesics | |

| Dihydrocodeine, codeine as analgesic (n = 40) | 2.45 [2.10; 2.80] |

| Pethidine (n = 46) | 1.91 [1.66; 2.17] |

| Tramadol (n = 46) | 2.65 [2.33; 2.97] |

| Tapentadol (n = 37) | 2.59 [2.30; 2.89] |

| Methadone, levomethadone (n = 40) | 2.30 [2.00; 2.60] |

| Acetylsalicylic acid as analgesic (n = 47) | 2.45 [2.12; 2.77] |

| Phenazone (n = 35) | 1.89 [1.65; 2.12] |

| Propyphenazone (n = 36) | 2.19 [1.87; 2.52] |

| Ergotamine (n = 44) | 1.59 [1.41; 1.77] |

| Antiepileptics | |

| Phenobarbital (n = 40) | 1.53 [1.35; 1.70] |

| Primidone (n = 39) | 2.23 [1.95; 2.51] |

| Phenytoin (n = 40) | 2.43 [2.13; 2.72] |

| Carbamazepine (n = 46) | 2.39 [2.13; 2.65] |

| Drugs for Parkinson’s disease | |

| Trihexyphenidyl (n = 33) | 1.73 [1.47; 1.98] |

| Biperiden (n = 38) | 2.26 [1.94; 2.58] |

| Procyclidine (n = 34) | 1.91 [1.59; 2.24] |

| Bornaprine (n = 33) | 2.06 [1.73; 2.39] |

| Amantadine (n = 41) | 2.49 [2.16; 2.82] |

| Pramipexole (n = 41) | 2.66 [2.37; 2.95] |

| Piribedil (n = 30) | 2.43 [2.14; 2.72] |

| Dopaminergic ergot alkaloids (e.g., pergolide) (n = 40) | 2.05 [1.81; 2.29] |

| Monoaminoxidase-B inhibitors (e.g., selegiline) (n = 35) | 2.46 [2.12; 2.79] |

| Tolcapone (n = 33) | 2.48 [2.25; 2.72] |

| Antipsychotics | |

| Levomepromazine (n = 44) | 1.57 [1.33; 1.81] |

| Fluphenazine (n = 35) | 1.54 [1.33; 1.75] |

| Perphenazine (n = 39) | 1.79 [1.52; 2.06] |

| Perazine (n = 31) | 2.13 [1.78; 2.48] |

| Thioridazine (n = 39) | 1.59 [1.32; 1.85] |

| Haloperidol (n = 45) | 2.16 [1.86; 2.46] |

| Melperone > 100 mg/d, > 6 weeks (n = 36) | 1.92 [1.73; 2.10] |

| Pipamperone > 120 mg/d, > 6 weeks (n = 36) | 2.06 [1.80; 2.31] |

| Bromperidol (n = 33) | 1.82 [1.58; 2.06] |

| Benperidol (n = 31) | 1.84 [1.57; 2.11] |

| Sertindole (n = 35) | 1.77 [1.49; 2.05] |

| Ziprasidone (n = 37) | 2.08 [1.78; 2.38] |

| Flupentixol (n = 41) | 1.90 [1.67; 2.13] |

| Chlorprothixene (n = 41) | 1.71 [1.45; 1.96] |

| Zuclopenthixol (n = 40) | 1.73 [1.53; 1.92] |

| Fluspirilene (n = 33) | 1.79 [1.47; 2.10] |

| Pimozide (n = 35) | 1.49 [1.29; 1.68] |

| Clozapine (n = 42) | 2.12 [1.84; 2.40] |

| Olanzapine (n = 43) | 2.28 [1.99; 2.57] |

| Quetiapine > 100 mg/d, > 6 weeks (n = 43) | 2.23 [1.97; 2.50] |

| Sulpiride (n = 40) | 2.30 [2.01; 2.59] |

| Tiapride (n = 37) | 2.30 [2.03; 2.57] |

| Amisulpride (n = 38) | 2.24 [1.96; 2.52] |

| Prothipendyl (n = 39) | 2.13 [1.82; 2.44] |

| Risperidone > 6 weeks (n = 45) | 2.69 [2.38; 2.99] |

| Aripiprazole (n = 39) | 2.41 [2.10; 2.72] |

| Paliperidone (n = 32) | 2.47 [2.10; 2.83] |

| Cariprazine (n = 27) | 2.00 [1.73; 2.27] |

| Anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives | |

| Hydroxyzine (n = 44) | 1.70 [1.46; 1.95] |

| Long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam) (n = 44) | 1.45 [1.29; 1.62] |

| Lorazepam (n = 43) | 2.26 [1.95; 2.56] |

| Moderately long-acting benzodiazepines(e.g., oxazepam) (n = 46) | 2.13 [1.91; 2.35] |

| Short-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., triazolam) (n = 44) | 2.20 [1.90; 2.51] |

| Chloral hydrate (n = 40) | 1.78 [1.54; 2.01] |

| Zopiclone (n = 39) | 2.23 [1.93; 2.53] |

| Zolpidem (n = 43) | 2.35 [2.06; 2.64] |

| Clomethiazole (n = 40) | 1.93 [1.62; 2.23] |

| Doxylamine (n = 40) | 1.63 [1.42; 1.83] |

| Promethazine (n = 39) | 1.92 [1.60; 2.25] |

| Antidepressants | |

| Tricyclics (e.g., amitriptyline) (n = 46) | 1.65 [1.42; 1.88] |

| Opipramol (n = 41) | 2.24 [1.98; 2.51] |

| Nortriptyline*4 (n = 37) | 2.22 [1.95; 2.48] |

| Doxepin (n = 41) | 1.88 [1.57; 2.19] |

| Maprotiline (n = 42) | 1.83 [1.61; 2.06] |

| Fluoxetine (n = 43) | 2.23 [1.97; 2.50] |

| Paroxetine (n = 45) | 2.29 [2.01; 2.57] |

| Sertraline > 100 mg/d (n = 40) | 2.33 [2.06; 2.59] |

| Fluvoxamine (n = 41) | 2.17 [1.91; 2.43] |

| Tranylcypromine (n = 37) | 1.81 [1.51; 2.11] |

| Moclobemide (n = 42) | 2.62 [2.31; 2.93] |

| St John’s wort (n = 45) | 2.53 [2.22; 2.84] |

| Mianserin (n = 38) | 2.45 [2.14; 2.75] |

| Bupropion (n = 41) | 2.59 [2.28; 2.89] |

| Tianeptine (n = 36) | 2.56 [2.28; 2.83] |

| Agomelatine (n = 40) | 2.45 [2.12; 2.78] |

| Psychostimulants | |

| Methylphenidate (n = 36) | 1.78 [1.53; 2.02] |

| Pyritinol (n = 33) | 1.94 [1.66; 2.22] |

| Piracetam (n = 42) | 1.81 [1.58; 2.04] |

| Antidementives | |

| Ginkgo leaf (n = 41) | 2.61 [2.23; 2.99] |

| Nicergoline (n = 40) | 2.08 [1.83; 2.32] |

| Nimodipine (n = 34) | 2.15 [1.89; 2.41] |

| Drugs for vertigo | |

| Betahistine (n = 39) | 2.62 [2.27; 2.96] |

| Cinnarizine*5 (n = 40) | 2.13 [1.81; 2.44] |

| Flunarizine (n = 34) | 2.35 [2.06; 2.65] |

| Drugs for obstructive respiratory tract diseases | |

| Sympathomimetics for systemic use, no inhalation (e.g., salbumatol) (n = 44) | 2.34 [2.10; 2.59] |

| Theophylline, aminophylline (n = 42) | 1.83 [1.60; 2.07] |

| Cough and cold remedies | |

| Codeine, dihydrocodeine as antitussive (n = 42) | 2.29 [2.03; 2.54] |

| Antihistamines for systemic use | |

| First generation | |

| Diphenhydramine (n = 43) | 1.67 [1.45; 1.89] |

| Clemastine (n = 37) | 1.78 [1.50; 2.07] |

| Dimetindene (n = 39) | 1.87 [1.62; 2.12] |

| Cyproheptadine (n = 33) | 1.67 [1.42; 1.91] |

| Ketotifen (n = 35) | 2.31 [2.02; 2.61] |

| Second generation | |

| Ebastine (n = 34) | 2.50 [2.25; 2.75] |

| Rupatadine (n = 24) | 2.63 [2.30; 2.95] |

CI, Confidence interval; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; PPI, proton pump inhibitors

*1 License suspended since January 2021 owing to nitrosamine contamination

*2 In Germany: only as a compound with atenolol and chlorthalidone

*3 Additional evaluation in third round with time and dose limitation; data on confidence interval etc. for evaluation without time and dose limitation

*4 According to comments, nortriptyline is tolerated better than other tricyclics; therefore, it was evaluated in its own right in the second round of the Delphi process

*5 In Germany: only as a compound with dimenhydrinate

eTable 3. Substances classified as non-PIM.

| Substance/class | No. of ratings | Median | Mean | [95% CI] |

| Drugs for acidity-related diseases | ||||

| Magnesium hydroxide (as an example of antacids containing magnesium) | 44 | 3 | 3.34 | [3.09; 3.59] |

| Proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, dexlansoprazole, rabeprazole) | 46 | 4 | 3.74 | [3.49; 3.99] |

| Sucralfate | 43 | 4 | 3.44 | [3.13; 3.75] |

| Drugs for constipation | ||||

| Macrogol | 46 | 4 | 4.24 | [4.00; 4.47] |

| Drugs for diarrhea and intestinal anti-inflammatories/anti-infectives | ||||

| Loperamide | 44 | 4 | 3.30 | [3.02; 3.57] |

| Antidiabetic drugs | ||||

| Insulins and analogs for injection, rapid-acting (“sliding scale insulins”, (treatment without basal insulin/long-acting insulins) | 43 | 4 | 3.47 | [3.07; 3.86] |

| Metformin | 47 | 4 | 4.00 | [3.74; 4.26] |

| Dipeptidylpeptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin…) | 45 | 4 | 3.67 | [3.38; 3.95] |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (exenatide, liraglutide,albiglutide, dulaglutide, lixisenatide*) | 39 | 3 | 3.44 | [3.13; 3.74] |

| Sodium-glucose-cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, canagliflozin*) | 44 | 3.5 | 3.32 | [3.03; 3.61] |

| Antithrombotic drugs | ||||

| Warfarin | 36 | 4 | 3.83 | [3.50; 4.16] |

| Phenprocoumon | 45 | 4 | 3.80 | [3.52; 4.08] |

| Acenocoumarol* | 29 | 4 | 3.66 | [3.27; 4.04] |

| Rivaroxaban | 44 | 4 | 3.36 | [3.06; 3.67] |

| Apixaban | 44 | 4 | 3.89 | [3.65; 4.12] |

| Edoxaban | 46 | 4 | 3.63 | [3.33; 3.93] |

| Cardiac treatment | ||||

| Propafenone as “single shot” | 38 | 4 | 3.58 | [3.33; 3.83] |

| Ivabradine | 44 | 4 | 3.39 | [3.08; 3.70] |

| Potassium-sparing drugs | ||||

| Spironolactone | 46 | 4 | 3.63 | [3.38; 3.88] |

| Eplerenone | 40 | 4 | 3.58 | [3.31; 3.84] |

| Calcium-channel blockers | ||||

| Moderately long-acting and long-acting calcium-channel blockers with predominantly vascular action (amlodipine, felodipine, isradipine, nisoldipine, nitrendipine, manidipine, lercanidipine) | 42 | 4 | 3.98 | [3.73; 4.22] |

| Drugs acting on the renin–angiotensin system | ||||

| Valsartan and sacubitril | 45 | 4 | 3.71 | [3.41; 4.01] |

| Urologics | ||||

| Tamsulosin | 43 | 4 | 3.58 | [3.36; 3.81] |

| Calcium homeostasis | ||||

| Teriparatide | 38 | 4 | 3.42 | [3.07; 3.78] |

| Drugs for treating bone diseases | ||||

| Denosumab | 37 | 4 | 3.49 | [3.12; 3.85] |

| Analgesics | ||||

| Metamizole | 46 | 4 | 3.96 | [3.74; 4.17] |

| Antiepileptics | ||||

| Gabapentin | 41 | 4 | 3.39 | [3.09; 3.69] |

| Levetiracetam NEW | 40 | 4 | 3.43 | [3.09; 3.76] |

| Antipsychotics | ||||

| Risperidone | 45 | 4 | 3.53 | [3.29; 3.78] |

| Antidepressants | ||||

| Citalopram, escitalopram | 45 | 4 | 3.51 | [3.27; 3.76] |

| Sertraline | 41 | 4 | 3.54 | [3.27; 3.80] |

| Mirtazapine | 42 | 4 | 3.45 | [3.15; 3.75] |

| Antidementives | ||||

| Memantine | 42 | 4 | 3.36 | [3.01; 3.70] |

| Drugs for obstructive respiratory tract diseases | ||||

| Inhaled anticholinergics (ipratropium bromide, tiotropium bromide, aclidinium bromide, glycopyrronium bromide, umeclidinium bromide) | 43 | 4 | 3.65 | [3.36; 3.94] |

| Antihistamines for systemic use | ||||

| Second generation | ||||

| Cetirizine, levocetirizine | 43 | 4 | 3.44 | [3.19; 3.70] |

| Loratadine, desloratadine | 38 | 4 | 3.47 | [3.19; 3.76] |

*These substances are marketed only in Austria, not in Germany.

CI, Confidence interval; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Funding

The study was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (project no. BMBF 01KX1812) and by the Association of Austrian Social Insurance Funds (Dachverband der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger; project no. FA636A0504).

Acknowledgments

For their participation in the Delphi process, we thank the following: Eva Blozik, Birgit Böhmdorfer, Juliane Bolbrinker, Harald Dormann, Peter Dovjak, Corinna Drebenstedt, Günther Egidi, Gottfried Endel, Heinz Endres, Alexander Friedl, Thomas Frühwald, Gerald Ohrenberger, Markus Gosch, Athe Grafinger, Gerhard Gründer, Thomas Günnewig, Walter E. Haefeli, Ekkehard Haen, Sebastian Harder, Steffen Härterich, Siegfried Hartmann, Hans Jürgen Heppner, Walter Hewer, Christine Hofer-Dückelmann, Ulrich Jaehde, Petra Kaufmann-Kolle, Rainer Kiefmann, Michael Klock, Karin Kraft, Reinhold Kreutz, Renke Maas, Eva Mann, Werner-J. Mayet, Reli Mechtler, Guido Michels, Veselin Mitrovic, Klaus Mörike, Ursula Müller-Werdan, Beate Mussawy, Wilhelm-Bernhard Niebling, Roman Pfister, Susanne Rabady, Ina Richling, Thomas Riemer, Christoph Ritter, Martin Scherer, Guido Schmiemann, Jochen Schuler, Oliver Senn, Michael Smeikal, Isabel Waltering, Dietmar Weixler, Andreas Wiedemann, Hans Wille, Stefan Wilm, Rainer Wirth, Ursula Wolf, Joachim Zeeh, Michael Zieschang.

Für supporting our project in other ways, we thank: Tobias Dreischulte, Birol Knecht, Katja Niepraschk-von Dollen, Helmut Schröder, Carsten Telschow, Anette Zawinell.

References

- 1.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin. Multimorbidität. S3-Leitlinie. DEGAM-Leitlinie Nr. 20. https://www.degam.de/files/Inhalte/Leitlinien-Inhalte/Dokumente/DEGAM-S3-Leitlinien/053-047_Multimorbiditaet/053-047l_%20Multimorbiditaet_redakt_24-1-18.pdf (last accessed on 30 November 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pharmakotherapie LHH. Hausärztliche Leitlinie Multimedikation, Version 2.00. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi S, Morike K, Klotz U. The clinical implications of ageing for rational drug therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:183–199. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies EA, O‘Mahony MS. Adverse drug reactions in special populations—the elderly. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80:796–807. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thurmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:543–551. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endres HG, Kaufmann-Kolle P, Steeb V, Bauer E, Bottner C, Thurmann P. Association between Potentially Inappropriate Medication (PIM) use and risk of hospitalization in older adults: an observational study based on routine data comparing PIM use with use of PIM alternatives. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146811. e0146811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henschel F, Redaelli M, Siegel M, Stock S. Correlation of incident potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions and hospitalization: an analysis based on the PRISCUS list. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015;2:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s40801-015-0035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer TK, Lindenbaum K, Stroka MA, Engel S, Linder R, Verheyen F. Fall risk increasing drugs and injuries of the frail elderly—evidence from administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:1321–1327. doi: 10.1002/pds.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez YV, Renom-Guiteras A, Reeves D, et al. A set of systematic reviews to help reduce inappropriate prescribing to older people: study protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0570-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schott G, Martinez YV, Ediriweera de Silva RE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors in the management of type 2 diabetes in older adults: a systematic review and development of recommendations to reduce inappropriate prescribing. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0571-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlender L, Martinez YV, Adeniji C, et al. Efficacy and safety of metformin in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: a systematic review for the development of recommendations to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogele A, Johansson T, Renom-Guiteras A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of beta blockers in the management of hypertension in older adults: a systematic review to help reduce inappropriate prescribing. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0575-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommerauer C, Schlender L, Krause M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vitamin K antagonists and new anticoagulants in the prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation in older adults—a systematic review of reviews and the development of recommendations to reduce inappropriate prescribing. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0573-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) AWMF-Regelwerk Leitlinien. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer G, Meerpohl JJ, Perleth M, Gartlehner G, Kaminski-Hartenthaler A, Schunemann H. [GRADE guidelines: 1 Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables] Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhewes. 2012;106:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathes T, Mann N-K, Thürmann P, Sönnichsen A, Pieper D. Assessing the quality of evidence on safety: specifications for application and suggestions for adaptions of the GRADE-criteria in the context of preparing a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older adults. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22 doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01715-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IBM. Micromedex. www.ibm.com/watson-health/about/micromedex (last accessed on 30 November 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PloS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. e20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farooqi V, van den Berg ME, Cameron ID, Crotty M. Anabolic steroids for rehabilitation after hip fracture in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008887.pub2. CD008887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider-Thoma J, Efthimiou O, Bighelli I, et al. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs and short-term somatic serious adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:753–765. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed H, Davies F, Francis N, Farewell D, Butler C, Paranjothy S. Long-term antibiotics for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015233. e015233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloch F, Thibaud M, Dugué B, Brèque C, Rigaud AS, Kemoun G. Laxatives as a risk factor for iatrogenic falls in elderly subjects: myth or reality? Drugs Aging. 2010;27:895–901. doi: 10.2165/11584280-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho H, Myung J, Suh HS, Kang HY. Antihistamine use and the risk of injurious falls or fracture in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29:2163–2170. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4564-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee PE, Gill SS, Freedman M, Bronskill SE, Hillmer MP, Rochon PA. Atypical antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329 doi: 10.1136/bmj.38125.465579.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider-Thoma J, Efthimiou O, Huhn M, et al. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs and short-term mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomised controlled trials. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:653–663. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tham A, Jonsson U, Andersson G, Söderlund A, Allard P, Bertilsson G. Efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants in people aged 65 years or older with major depressive disorder—a systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;205:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansbart F, Kienberger G, Sönnichsen A, Mann E. Efficacy and safety of adrenergic alpha-1 receptor antagonists in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the development of recommendations to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing PREPRINT (Version 1). Research Square. www.europepmc.org/article/PPR/PPR440769 (last accessed on 30 November 2022) 2022 doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motter FR, Fritzen JS, Hilmer SN, Paniz ÉV, Paniz VMV. Potentially inappropriate medication in the elderly: a systematic review of validated explicit criteria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:679–700. doi: 10.1007/s00228-018-2446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doni K, Bühn S, Weise A, et al. Safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in older adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2022;13 doi: 10.1177/20420986211072383. 20420986211072383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudolf H, Thiem U, Aust K, et al. Reduction of potentially inappropriate medication in the elderly—results of a cluster-randomized, controlled trial in German primary care practices (RIME) Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118:875–882. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selke Krulichová I, Selke GW, Thürmann PA. Trends and patterns in EU(7)-PIM prescribing to elderly patients in Germany. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77:1553–1561. doi: 10.1007/s00228-021-03148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Florisson S, Aagesen EK, Bertelsen AS, Nielsen LP, Rosholm JU. Are older adults insufficiently included in clinical trials?—an umbrella review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;128:213–223. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scherag A, Andrikyan W, Dreischulte T, et al. POLAR - „POLypharmazie, Arzneimittelwechselwirkungen und Risiken“ - wie können Daten aus der stationären Krankenversorgung zur Beurteilung beitragen? Präv Gesundheitsf (2022) doi.org/10.1007/s11553-022-00976-8. [Google Scholar]

- E1.Mann E, Bohmdorfer B, Fruhwald T, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication in geriatric patients: the Austrian consensus panel list. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:160–169. doi: 10.1007/s00508-011-0061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Renom-Guiteras A, Meyer G, Thurmann PA. The EU(7)-PIM list: a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:861–875. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1860-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Chang CB, Yang SY, Lai HY, et al. Using published criteria to develop a list of potentially inappropriate medications for elderly patients in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:1269–1279. doi: 10.1002/pds.3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Chang CB, Lai HY, Hwang SJ, et al. The updated PIM-Taiwan criteria: a list of potentially inappropriate medications in older people. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10 doi: 10.1177/2040622319879602. 2040622319879602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Clyne B, Bradley MC, Hughes CM, et al. Addressing potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients: development and pilot study of an intervention in primary care (the OPTI-SCRIPT study) BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Fimea FMA. Meds75 Database of Medications for Older Persons. 2020. www.fimea.fi/web/en/databases_and_registeries/medicines_information/database_of_medication_for_older_persons (last accessed on 19 December 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E10.Khodyakov D, Ochoa A, Olivieri-Mui BL, et al. Screening tool of older person‘s prescriptions/screening tools to alert doctors to right treatment medication criteria modified for US. nursing home setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:586–591. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Kim DS, Heo SI, Lee SH. Development of a list of potentially inappropriate drugs for the korean elderly using the Delphi method. Healthc Inform Res. 2010;16:231–252. doi: 10.4258/hir.2010.16.4.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Kim SO, Jang S, Kim CM, Kim YR, Sohn HS. Consensus validated list of potentially inappropriate medication for the elderly and their prevalence in South Korea. Int J Gerontol. 2015;9:136–141. [Google Scholar]

- E13.Kojima T, Mizukami K, Tomita N, et al. Screening tool for older persons‘ appropriate prescriptions for Japanese: report of the Japan Geriatrics Society Working Group on „Guidelines for medical treatment and its safety in the elderly“. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:983–1001. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Kuhn-Thiel AM, Weiss C, Wehling M. Consensus validation of the FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list: a clinical tool for increasing the appropriateness of pharmacotherapy in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2014;31:131–140. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Maio V, Del Canale S, Abouzaid S. Using explicit criteria to evaluate the quality of prescribing in elderly Italian outpatients: a cohort study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010;35:219–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Mazhar F, Akram S, Malhi SM, Haider N. A prevalence study of potentially inappropriate medications use in hospitalized Pakistani elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Nyborg G, Straand J, Klovning A, Brekke M. The Norwegian General Practice—Nursing Home criteria (NORGEP-NH) for potentially inappropriate medication use: a web-based Delphi study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33:134–141. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2015.1041833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Oelke M, Becher K, Castro-Diaz D, et al. Appropriateness of oral drugs for long-term treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older persons: results of a systematic literature review and international consensus validation process (LUTS-FORTA 2014) Age Ageing. 2015;44:745–755. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.O‘Mahony D, O‘Sullivan D, Byrne S, O‘Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M. The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List 2015: update of a validated clinical tool for improved pharmacotherapy in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2016;33:447–449. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M. The EURO-FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List: International consensus validation of a clinical tool for improved drug treatment in older people. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:61–71. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M. The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List 2018: third version of a validated clinical tool for improved drug treatment in older people. Drugs Aging. 2019;36:481–484. doi: 10.1007/s40266-019-00669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Tommelein E, Petrovic M, Somers A, Mehuys E, van der Cammen T, Boussery K. Older patients‘ prescriptions screening in the community pharmacy: development of the Ghent Older People‘s Prescriptions community Pharmacy Screening (GheOP(3)S) tool. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:e158–e170. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Kuwabara M, Nagano M, Okamoto T, Tanaka M. Long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease therapy improves reflux symptoms in elderly patients: five-year prospective study in community medicine. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:639–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Maggio M, Corsonello A, Ceda GP, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of 1-year mortality and rehospitalization in older patients discharged from acute care hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:518–523. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Shah S, Lewis A, Leopold D, Dunstan F, Woodhouse K. Gastric acid suppression does not promote clostridial diarrhoea in the elderly. QJM. 2000;93:175–181. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Yearsley KA, Gilby LJ, Ramadas AV, Kubiak EM, Fone DL, Allison MC. Proton pump inhibitor therapy is a risk factor for Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:613–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006;296:2947–2953. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Haenisch B, von Holt K, Wiese B, et al. Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Herghelegiu AM, Prada GI, Nacu R. Prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors and cognitive function in older adults. Farmacia. 2016;64:262–267. [Google Scholar]

- E31.Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:410–416. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Gray SL, Walker RL, Dublin S, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and dementia risk: prospective population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:247–253. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Goldstein FC, Steenland K, Zhao L, Wharton W, Levey AI, Hajjar I. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1969–1974. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2015;3:E166–E171. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]