Abstract

Anencephaly, the most severe form of neural tube defect, has no known cure, and in most cases, patients die before or shortly after birth. To date, no surgical intervention has been reported in the management of anencephaly. This study presents a case of dichorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy in which 1 twin was anencephalic and describes the surgical management of this complex case. We aimed to share the problems experienced during the follow up of a patient who survived for a long time after surgery. We also aimed to highlight several clinical issues, including the challenges of managing anencephaly in twin pregnancies, problems experienced during the follow up process in our case, diagnosis of brain death in anencephaly cases, and ethical dilemmas related to organ donation. This case is notable because of the challenging nature of the surgical procedure and complexity of postoperative care. By highlighting the difficulties encountered during the follow up period, we hope to provide insights to health professionals that can inform the management of similar cases in the future.

Keywords: anencephaly, anomaly, neural tube defects, twin pregnancy

1. Introduction

Anencephaly, one of the most severe forms of neural tube defects (NTDs), is a central nervous system (CNS) malformation characterized by the absence of the cerebral hemispheres, skull, and scalp, which is often incompatible with life. This severe fetal anomaly can be safely diagnosed using routine ultrasound (US) at 10 to 14 weeks of pregnancy.[1] Pregnancy with an anencephalic fetus carries risks to the fetus and the mother. Approximately 2-thirds of anencephalic patients die during intrauterine life and the termination of pregnancy. Very rare cases can reach delivery, but these patients usually die within the first 24 hours after birth.[2]

The CNS, which consists of the brain and the spinal cord, develops from the embryonic ectoderm. CNS development begins as early as the third and 4th weeks of embryonic life, starting with the neurulation process, which involves development of the neural tube. During this developmental period, the neural tube spontaneously closes, both rostrally and caudally.[3] However, any disruption of the neural tube closure process can lead to NTDs. Anencephaly may occur if the rostral neuropore of the neural tube fails to close in the 4th week.[4]

Despite many years of intensive epidemiological, clinical, and experimental research, the exact etiology of anencephaly remains complex and poorly understood. The etiology of anencephaly includes various maternal-related environmental and genetic risk factors, including folate deficiency, diabetes mellitus, obesity, use of valproic acid, exposure to different toxins, zinc deficiency, hyperthermia, positive family history of NTDs, genetic polymorphisms, and mutations.[5,6]

One of the most important factors in the development of anencephaly is insufficient folate intake coupled with increased folate demands during pregnancy. Adequate folate intake during pregnancy is crucial for proper neural tube closure and proper brain development. Folate supplementation reduces the risk of anencephaly and other NTDs.[4,5]

Similar to most NTDs, anencephaly has a multifactorial pattern of inheritance. Once a mother has had a child with anencephaly, the risk of recurrence in future pregnancies is significantly higher than that in the general population. The risk of recurrence depends on several factors, including the severity of anencephaly in the affected child, presence of other affected family members, and maternal folate status. Therefore, preconception counseling and careful monitoring of folate levels during pregnancy are essential for women with a history of anencephaly or other NTDs.[4,5]

The frequency of anencephaly varies across different regions of the world. A recent meta-analysis by Salari et al[6] is one of the most comprehensive studies to determine the prevalence of anencephaly worldwide. This meta-analysis included 360 studies with a sample size of more than 200 million people. According to this study, the worldwide prevalence of anencephaly was reported to be 5.1 per 10,000 births.

Owing to the defect’s incompatibility with life in the short and medium terms, pregnancy termination is recommended when an anencephalic fetus is detected in the early period of pregnancy. This is to prevent the fetus from reaching later gestational weeks, minimize physical and mental trauma to the mother, and prevent possible complications that may occur during pregnancy and delivery. Additionally, psychosocial problems faced by parents in cases where they do not have a healthy baby have become a significant challenge. Another important problem in anencephaly cases is the ongoing ethical and medical discussions regarding the diagnosis of brain death in these cases and the patient’s candidacy for organ transplantation.

To date, no case of anencephaly in which surgical intervention has been performed has been reported. This article presents a case study of an anencephalic patient who was born from a dichorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy and was able to survive for more than 3 years on life support following surgical treatment. This study aimed to share our surgical experience in keeping an anencephalic baby alive with healthcare professionals, provide useful information about the management of this challenging process, and draw attention to the importance of NTD prevention.

2. Case presentation

Anencephaly was detected in a girl born as a second baby at 37 weeks of gestation from a dichorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy obtained after the fifth in vitro fertilization (IVF) attempt of a 36-year-old primigravida mother. No risk factors other than twinning were identified during pregnancy. The mother used folic acid during the pregnancy. There was no consanguinity between the parents. An anencephalic fetus was detected using US in the first trimester of pregnancy. The patient’s family member did not undergo intrauterine termination. The birth weight was 2110 g (10–25p), and the height was 37 cm (<10 p). Physical examination revealed the absence of the scalp, calvarium, dura mater, and cerebral hemispheres; neural tissue compatible with the immature brainstem within the large defect; and multiple small cystic sacs around it (Fig. 1A and B). On neurological examination, the 4 extremities were mobile and myoclonus was present. The sucking reflex was hypoactive and the Moro and Grasp reflexes were normal. The pupils were isochoric, and there was no spontaneous eye movement. Light, corneal, and oculocephalic reflexes are absent. The patient, with moderate to mild spasticity in the extremities and spontaneous respiration, was being followed-up in the intensive care unit (ICU) and had tonic extremity contractions triggered by touch. The patient was provided with nutrition through an orogastric tube. When central hypothyroidism and diabetes insipidus were observed during follow up, L-thyroxine (Euthrox) and desmopressin (Minirin) treatment was initiated.

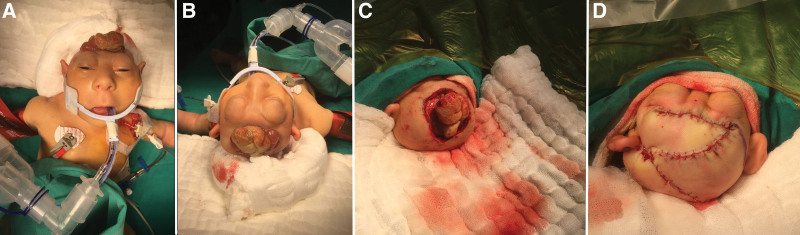

Figure 1.

Side (A) and superior, (B) views of a newborn with anencephaly. The figure shows 2 views of an infant with anencephaly: a severe neural tube defect characterized by the absence of the fetal brain and skull above the base of the skull. Panel A shows a side view of the infant’s head highlighting the absence of a cranial vault above the skull base. Panel B shows the superior view of the infant’s head, revealing the exposed brainstem.

3. Surgical technique

The recommended treatment for open NTDs is prenatal surgical repair or postnatal surgical closure within the first few days after birth. Early intervention after delivery increased the survival rates in these cases. The rationale for the recommendation of rapid postpartum closure is to prevent infectious complications and protect the exposed neural tissue from possible trauma.[7]

The most important factors affecting NTD prognosis are low birth weight and high lesion levels in the spinal cord. In addition, the presence of congenital abnormalities, chromosomal abnormalities, and genetic syndromes accompanying NTDs is a poor prognostic factor.[8]

We performed this surgical procedure to close the defect that was open to the external environment and to stop the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak as soon as possible, as is performed for the treatment of other congenital NTDs. The surgical procedure was performed 3 weeks after birth once the patient reached a weight of 2500 g. Surgery was performed with the patient under general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation in the supine position. The patient’s head was positioned on a pediatric silicone cap and routine arterial monitoring was performed. Left subclavian and Foley catheters were inserted and the patient’s body was wrapped in cotton drapes to prevent intraoperative hypothermia. The surgical site was then cleaned and sterile draping was applied (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

(A) Perioperative front view of the patient. (B) Perioperative superior view of the patient. (C) Intraoperative view of the explored brain stem. (D) Immediate postoperative appearance after reconstruction of the scalp defect. The surgical procedure involved exploration of the brainstem and reconstruction of scalp defects. The images presented in panels A and B show the patient before surgery, while panel C shows a view of the brainstem during surgery. Panel D shows the immediate postoperative appearance after reconstruction of the scalp defect.

Initially, we performed microsurgical dissection to remove immature neural tissue and surrounding multiple CSF vesicles from the brainstem. Subsequently, the borders of the dura were exposed through microsurgical dissection to facilitate an effective duraplasty using a dural graft. After excising the nonfunctional perineural tissues and identifying the dural lateral borders, the brainstem was fully exposed. (Fig. 2C). Subsequently, the edges of the dura mater are released along the borders of the skull base. Owing to the insufficient availability of autologous flaps, a xenograft (DuraGen Classic-Bovine pericardium) was used to close the dural defect. The xenograft was hydrated, measured, and cut to an appropriate size and shape that allowed for an approximately 1 cm overlap with the dural defect. After positioning the graft, watertight closure was achieved using a 4 to 0 silk suture using a running-locked technique.

Extensive duraplasty prevents the compression of neural tissue, improves the chances of free passage of CSF around the brainstem, and prevents the development of adhesions. Fibrin glue was applied to reduce the possibility of CSF leakage further.

CSF leakage after closure surgery for NTDs poses a serious threat to the clinical prognosis of surgical cases, increasing the risk of infection, prolonging the hospital stay, and necessitating reoperation. In addition to the distressing situation, it creates for the patient and neurosurgeon, and preventing this complication is crucial. Identifying the risk factors for CSF leakage and applying appropriate dural closure techniques can significantly reduce associated morbidity.

During the surgery and radiological examination of the patient, we did not observe the choroid plexus tissue responsible for CSF production. We believe that this absence may have contributed to the lack of CSF leakage in the postoperative period and absence of significant collection under the skin.

After duraplasty, a rotational advancement flap was used to close the large scalp defect. Cranioplasty was not performed to avoid hairy skin grafting due to insufficient hairy skin, early complications, and infections associated with the cranioplasty material (Fig. 2D). During the surgical procedure, the blood vessels feeding the already exposed neural tissue were carefully preserved. Saline-buffered irrigation was preferred for hemostasis in the first step and coagulation was avoided as much as possible. In cases where bleeding persisted, hemostatic materials such as oxidized regenerated cellulose were used temporarily. No surgical drain was used during the procedure.

After skin closure, the operative field was disinfected using standard protocols and the wound was covered with sterile gauze to prevent further injury.

Early postoperative complications following this surgery may include skin healing problems, CSF or interstitial fluid collection under the skin, hematoma, surgical site infection, wound dehiscence, CSF leak, meningitis, and worsening neurological levels. However, in the present case, no early or late postoperative complications were observed during follow up.

4. Postoperative course

After the operation, the patient was transferred to the neonatal ICU and was intubated. Tracheostomy was performed in the second week after intubation. Six months after surgery, the patient was followed up in the ICU with intermittent spontaneous breathing and mechanical ventilation. Because the sucking and swallowing reflexes of this anencephalic patient were insufficient, nutritional support and medical treatment were provided using a nasogastric tube.

Anencephalic cases require hormone replacement therapy because of pituitary hypoplasia and the absence of the hypothalamus. In this particular case, growth hormone, levothyroxine, desmopressin, and low-dose prednisolone were administered as hormone replacement therapy.

During the patient’s hospital stay, practical applications and special training were provided to the family regarding patient care while using the portable ventilator at home. The patient was discharged from the hospital with tracheostomy 6 months after birth. The family reported that the baby slept for most of the day, rarely opened his eyes, and moved his extremities intermittently (Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Anencephalic infant at 1 and 2 years of age. (A) Photo of the anencephalic infant at 1 year of age. (B) Photo of the same anencephalic infant at 2 years of age. The photos presented in panels A and B show the progression of the condition in the same infant over the course of 1 year.

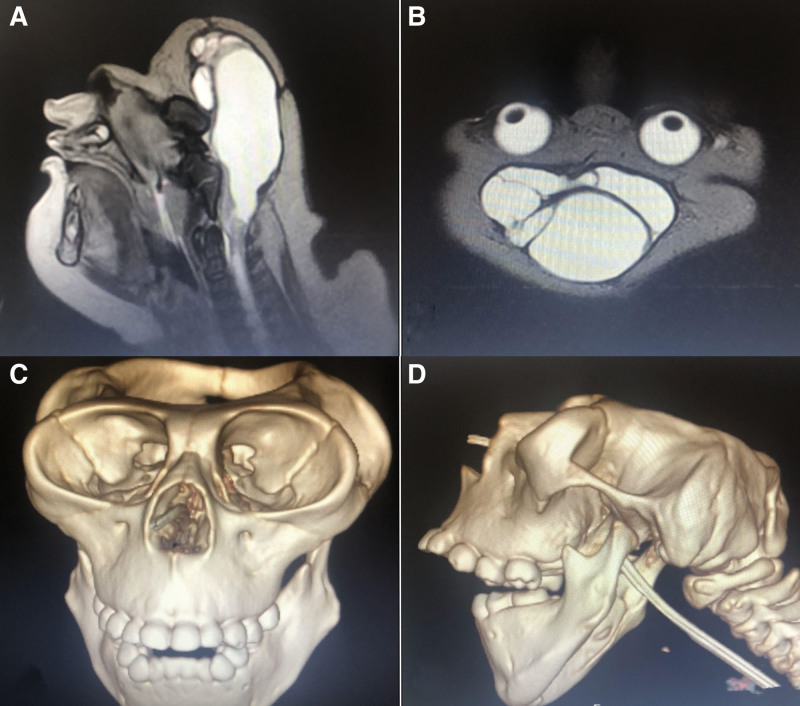

During the follow up period, magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 4A and B) and computerized tomography (Fig. 4C and D) were performed at the age of 2 years.

Figure 4.

MRI and CT Imaging of Patient’s Head at Age 2 Years. (A) T2-weighted sagittal MRI image of the patient’s head. (B) T2-weighted axial MRI image of the patient’s head. (C) Anterior view of 3D CT imaging of the patient’s head at age 2 years, showing the absence of a major portion of the skull. (D) Lateral view of 3D CT imaging of the patient’s head at age 2 years, showing the absence of a major portion of the skull. The MRI resonance imaging revealed the presence of cerebrospinal fluid-filled membranous structures in the region of the head and the absence of a cerebrum and cerebellum. CT showed the absence of a major portion of the skull, as seen in the anterior and lateral views presented in panels C and D. CT = computerized tomography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Unfortunately, this extraordinary case could only last for 3 years and a week. However, since the beginning of this process, families have not taken a positive approach to issues such as genetic studies and organ and tissue donations.

5. Discussion

Today, the prevalence of anencephaly cases in live births has decreased significantly due to the fact that they can be detected in the prenatal period with easily accessible imaging methods such as US, so they can be prevented at a high rate with low-cost measures such as folic acid and food supplements. When such an anomaly is detected, pregnancy terminates.

Studies investigating the worldwide prevalence of tube defects have reported that the prevalence of anencephaly varies according to geographical region and time, and tends to decrease gradually.[9,10] The prevalence of anencephaly was found to be 4.92 per 10,000 people in a population-based study of 1600 anencephaly cases conducted by Gong et al[9] in China, which is one of the studies with the largest number of cases in the literature. While this rate is 0.3 per 10,000 live births in high-income countries, it has been reported to be as high as 113 per 10,000 in low-income countries. The authors also reported that the prevalence of the disease decreased by 10% to 15% annually between 2006 and 2015.[9] More recently, Salari et al[6] published a study on the worldwide prevalence of anencephaly that analyzed 360 studies with over 200 million participants. Their findings showed a prevalence of 5.1 per 10,000 births.

In a systematic literature review published by Johnson et al[11], the frequency of pregnancy termination following the prenatal diagnosis of various malformations was estimated. This study revealed an 83% termination rate in cases of anencephaly.

5.1. Anencephaly in twin pregnancies

In dichorionic twin pregnancies, in which one of the fetuses is anencephalic, the already existing risks and complications further increase. The probability of survival of unaffected twins is related to 2 main factors. The first factor is the spontaneous death of the anencephalic fetus, while the other factor is the development of polyhydramnios. The development of polyhydramnios leads to a decreased swallowing ability in anencephalic twins.[12,13] In the management of such pregnancies, it is necessary to minimize the risk of death of normal twins; however, it is also important to prevent premature birth. Therefore, the dilemma of choosing the best management strategy emerges in the first trimester, when such cases are detected. In such cases, 3 different management options can be followed: Selective feticide; Intermittent US examination for polyhydramnios and, if necessary, amnio drainage or selective fluoride, and; Observation management.[14]

Unfortunately, studies on the management and outcomes of dichorionic twin pregnancies in women with anencephaly are scarce. In a review published by Vandecruys et al[14], the observation method was preferred in 35 of 44 dichorionic pregnancies with anencephalic fetuses, and selective feticide was applied in 9 cases. It has been reported that polyhydramnios developed in 20 (57.7%) dichorionic pregnancies for which the expectant method was preferred. It has been reported that the mean gestational age of 35 cases was 36 weeks, and non-encephalic twins were born alive in 34 cases (97%). In Lust et al[15] systematic literature review regarding dichorionic anencephalic twins, in which the selective feticide method was compared with expectant management, it was concluded that selective feticide did not reduce perinatal mortality of the unaffected twin, but it could provide long-term pregnancy and higher birth weight. Leeker et al[16] also emphasized that in twin pregnancies with an anencephalic fetus, selective feticide administration before the 15th week is a treatment option that reduces the risk of polyhydramnios and preterm delivery.

It should be noted that in terms of ethical considerations, the selective feticide procedure desired for an anencephalic fetus should be considered differently from the feticide procedure applied to a healthy and/or nonfatal fetus because anencephaly is an inevitably fatal condition at all stages of pregnancy and post-birth. Although a selective feticide procedure is recommended in anencephalic cases in which there is an unaffected twin, this method has an approximately 3% to 16% risk of miscarriage.[15,17] In our case, the selective feticide procedure offered to the family during pregnancy was unacceptable because of the risk of pregnancy termination. Furthermore, this pregnancy was a precious pregnancy after IVF for the family, and the other fetus looked healthy. Additionally, the culture and belief system of the family did not allow termination of the existing pregnancy.

5.2. Problems with treatment for anencephaly

There is currently no definitive standard treatment for anencephaly. Therefore, only supportive treatment is recommended and applied to patients who are usually lost in the early postpartum period, since there is no long-term life expectancy. Moreover, it is necessary to provide psychological counseling and support services to help parents cope with the loss of their children.

An opinion in the literature and in pediatric neurosurgery practice suggests that surgical treatment cannot be applied in anencephaly cases, and there are no published studies on the surgical technique and case management that can be successfully applied in this fatal malformation. Owing to advances in neurosurgery and scientific and technological innovations, treatment modalities continue to be developed for the management of cases of anencephaly, giant encephaloceles, amniotic band syndrome, placenta-cranial adhesions, and conjoined twins with craniopagus, which are among the most severe neurological malformations. These treatment modalities have been successfully applied owing to their multidisciplinary nature.[18–21] Such a multidisciplinary approach is particularly necessary for the management of anencephalic cases that can reach the delivery stage and are born alive. Neurosurgeons, neuroradiologists, plastic surgeons, neonatologists, and neuropediatric anesthetists collaborate and play important roles in the management of this process.

From the perspective of neurosurgery, as is practiced in routine surgical approaches for other NTDs such as meningocele, meningomyelocele, and encephalocele, the defect and neural tissue that are open to the external environment are closed as soon as possible, cutting off their relationship with the external environment. Successful closure of skull and scalp tissues is vital for preventing CSF leakage. In this case, the surgical closure procedure was successful when suitable surgical conditions were provided.

5.3. Cases with a long-term survival

Long-term survival in patients with anencephaly is rare, and the number of cases reported in the literature is limited. Dickman et al[22] reported an anencephalic case in which the patient lived for 28 months and did not require surgical intervention or medical support. McAbee et al[23] also presented 2 cases that did not require any surgical intervention and survived for 7 and 10 months without the need for mechanical ventilation. The Anencephaly Medical Task Force reported 2 cases: 1 in which the baby survived for 2, 3 months, and the other for 14 months.[2]

One of the most important features that makes our case unique is that it is a twin pregnancy. To our knowledge, this is also the first case in the literature to incorporate a surgical procedure for closure defects observed in this malformation. Furthermore, the patient had a long-term survival period of 37 months with medical support in the postoperative period.

5.4. Difficulties for parents

Today, because of advanced imaging technologies and serum screening tests, many parents experience fatal malformations before birth. In such cases, 2 different options await the family and each option is more difficult than the others. The first is to terminate the pregnancy and the second is to decide to continue the pregnancy, knowing that the baby will die prematurely. In the case under discussion, the family preferred continuation of the pregnancy because of twin pregnancy after the 5th IVF trial, with the other baby being healthy.

Having a baby with severe congenital malformations, such as anencephaly, presents an emotionally difficult situation for the parents. However, some mothers with a baby with a congenital malformation who have a high risk of fatality in the perinatal period and whose babies need palliative care may have higher positive motivation, contrary to expectations. Additionally, the cooperation of health care professionals and families during this period facilitates the care, acceptance, attachment, and adaptation processes of these cases. Thanks to the training, practical applications, and psychological support provided to the family during the hospitalization process in the case under discussion, the home care process continued for 3 years without any problems.

5.5. Brain death procedures and approach to organ donation in anencephaly

Controversial issues that arise in the presence of anencephaly include the definition of brain death in these cases, and the issue of organ donation candidacy. However, the ethical and legal issues remain unresolved. Because the cerebral cortex is not present in anencephalic cases, it is not possible to perform cerebral blood flow and electroencephalogram tests, which are generally used in the diagnosis of brain death. Therefore, in these cases, the concept of “brain stem death diagnosis” emerges instead of “brain death diagnosis” For the diagnosis of brain stem death, a positive apnea test with loss of observable cranial nerve functions and spontaneous movements for at least 48 hours is required.[2] Since the patient in our case died during follow up at home, it was not possible to diagnose brain stem death in the pre-death period.

Anencephaly has led to discussions regarding the availability of these cases for organ transplantation. Organ donation is based on volunteerism and sacrifice, and the organ donation rates are higher in developed countries. However, in most societies, the lack of organ donation due to beliefs, myths, and fears is unfortunately a reality, even today. Legal and ethical problems and dilemmas associated with organ donation in anencephalic patients remain.

In 2008, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Standing Committee on Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction presented 2 opinions considering the potential ethical problem regarding anencephaly and organ transplantation.[24] First, the mother’s wish to continue her anencephalic pregnancy for organ donation has created an ethical basis. However, parents should be counseled about organ donation by people who do not have conflicts of interest. The second opinion was that if an anencephalic baby was born with vital signs, it could be connected to a ventilator device for organ donation after natural death, with the permission of the parent.

However, the case under discussion is subject to the law of study location, namely Turkey. Although organ transplantation is important and in demand in Turkey, the number of organ donations is low for several reasons including legal issues. Law No. 2238 on “Organ and Tissue Retrieval, Storage, Vaccination and Transplantation,” which is still in force in Turkey, forbids the acquisition of organs and tissues from people who have not completed the age of 18 and who are not qualified to donate for other reasons.[25] Therefore, for the case we presented, organ transplantation would not have been possible even if the family consented, due to the relevant law.

Our study had some limitations. First, the rarity of the issue we analyzed means that we were able to include only 1 case in our analysis. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings is limited. Additionally, our study involves a challenging ethical decision that neurosurgeons may face, which can be subjective and vary depending on the specific circumstances.

6. Conclusion

Anencephalic pregnancies that reach the delivery stage result in a series of complex problems for infants, families, and health professionals. In cases where patients usually die in the early postnatal period, long-term life is possible with multidisciplinary cooperation. With the example case reported here, we can see that a longer life can be achieved following surgical closure performed under the appropriate conditions. In many countries, there are dilemmas regarding brain death in patients with anencephalic disease and their candidacy for organ donation. Therefore, it would be beneficial to discuss medical, ethical, and legal approaches in the management of anencephaly cases with a longer life expectancy than expected and to establish a consensus on this issue.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Güner Menekşe, Dilek Kahvecioğlu, Hatice Tatar Aksoy, Yüksel Kankaya.

Data curation: Güner Menekşe, Dilek Kahvecioğlu, Hatice Tatar Aksoy.

Investigation: Güner Menekşe.

Methodology: Güner Menekşe, Dilek Kahvecioğlu, Yüksel Kankaya.

Resources: Dilek Kahvecioğlu, Hatice Tatar Aksoy, Yüksel Kankaya.

Supervision: Güner Menekşe, Mehmet Akif Bayar.

Validation: Mehmet Akif Bayar.

Writing – original draft: Güner Menekşe.

Writing – review & editing: Güner Menekşe.

Abbreviations:

- CNS

- central nervous system

- CSF

- cerebrospinal fluid

- ICU

- intensive care unit

- IVF

- in vitro fertilization

- NTD

- neural tube defect

- US

- ultrasound

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

This manuscript is a technical note and a review. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required for this study.

Informed consent form was obtained from parents.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

How to cite this article: Menekşe G, Kahvecioğlu D, Aksoy HT, Kankaya Y, Bayar MA. First report of surgery for anencephaly in twin pregnancies: Technical notes and postoperative management. Medicine 2023;102:12(e33358).

Contributor Information

Dilek Kahvecioğlu, Email: dileksaracoglu@yahoo.com.

Hatice Tatar Aksoy, Email: haticetatar@yahoo.com.

Yüksel Kankaya, Email: ykankaya@gmail.com.

Mehmet Akif Bayar, Email: akifleyla@hotmail.com.

References

- [1].Johnson SP, Sebire NJ, Snijders RJ, et al. Ultrasound screening for anencephaly at 10-14 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:14–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Medical Task Force on Anencephaly. The infant with anencephaly. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:669–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rewane A, Munakomi S. Embryology, central nervous system, malformations. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Munteanu O, Cîrstoiu MM, Filipoiu FM, et al. The etiopathogenic and morphological spectrum of anencephaly: a comprehensive review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61:335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Padmanabhan R. Etiology, pathogenesis and prevention of neural tube defects. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). 2006;46:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Salari N, Fatahi B, Fatahian R, et al. Global prevalence of congenital anencephaly: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2022;19:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pektaş A, Boyaci MG, Koyuncu H, et al. Relevance of postnatal surgery in newborns with open neural tube defects: single center experience. Turk J Pediatr. 2021;63:683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lupo PJ, Agopian AJ, Castillo H, et al. Genetic epidemiology of neural tube defects. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2017;10:189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gong TT, Wu QJ, Chen YL, et al. Changing trends in the prevalence of anencephaly in Liaoning province of Northeast China from 2006-2015: data from a population-based birth defects registry. Oncotarget. 2017;8:52846–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zaganjor I, Sekkarie A, Tsang BL, et al. Describing the prevalence of neural tube defects worldwide: a systematic literature review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Johnson CY, Honein MA, Dana Flanders W, et al. Pregnancy termination following prenatal diagnosis of anencephaly or spina bifida: a systematic review of the literature. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:857–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lipitz S, Meizner I, Yagel S, et al. Expectant management of twin pregnancies discordant for anencephaly. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:969–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sebire NJ, Sepulveda W, Hughes KS, et al. Management of twin pregnancies discordant for anencephaly. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vandecruys H, Avgidou K, Surerus E, et al. Dilemmas in the management of twins discordant for anencephaly diagnosed at 11 + 0 to 13 + 6 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:653–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lust A, De Catte L, Lewi L, et al. Monochorionic and dichorionic twin pregnancies discordant for fetal anencephaly: a systematic review of prenatal management options. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Leeker M, Beinder E. Twin pregnancies discordant for anencephaly-management, pregnancy outcome and review of literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114:15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Evans MI, Goldberg JD, Dommergues M, et al. Efficacy of second-trimester selective termination for fetal abnormalities: international collaborative experience among the world’s largest centers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:90–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Menekse G, Mert MK, Olmaz B, et al. Placento-cranial adhesions in amniotic band syndrome and the role of surgery in their management: an unusual case presentation and systematic literature review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2015;50:204–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Menekse G, Celik H, Bayar MA. Giant parietal encephalocele with massive brain herniation and suboccipital encephalocele in a neonate: an unusual form of double encephalocele. World Neurosurg. 2017;98:867.e9–867.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Heuer GG, Madsen PJ, Flanders TM, et al. Separation of craniopagus twins by a multidisciplinary team. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pai KM, Naidu RC, Raja A, et al. Surgical nuances in the separation of craniopagus twins - Our experience and a follow up of 15 years. Neurol India. 2018;66:426–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dickman H, Fletke K, Redfern RE. Prolonged unassisted survival in an infant with anencephaly. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].McAbee G, Sherman J, Canas JA, et al. Prolonged survival of two anencephalic infants. Am J Perinatol. 1993;10:175–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].FIGO Committee for the Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women’s Health. Anencephaly and organ transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102:99.18423469 [Google Scholar]

- [25].Elmas I, Soysal Z, Tüzün B. Use of fetus with scientific investigation and transplantation purposes: medical, legal and ethical issues. Perinatol J (Turkish). 2000;8:65–8. [Google Scholar]