Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a consequence of complex interactions of age-related neurodegeneration and vascular-associated pathologies, affecting more than 44 million people worldwide. For the last decade, it has been suggested that chronic brain hypoperfusion and consequent hypoxia play a direct role in the pathogenesis of AD. However, current treatments of AD have not focused on restoring or improving microvascular perfusion. In a previous study, we showed that drag reducing polymers (DRP) enhance cerebral blood flow and tissue oxygenation. We hypothesized that hemorheologic enhancement of cerebral perfusion by DRP would be useful for treating Alzheimer’s disease. We used double transgenic B6C3-Tg(APPswe, PSEN1dE9) 85Dbo/Mmjax AD mice. DRP or vehicle (saline) was i.v. injected every week starting at four months of age till 12 months of age (10 mice/group). In-vivo 2-photon laser scanning microscopy was used to evaluate amyloid plaques development, cerebral microcirculation, and tissue oxygen supply/metabolic status (NADH autofluorescence). The imaging sessions were repeated once a month till 12 months of age. Statistical analyses were done by independent Student’s t-test or Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests where appropriate. Differences between groups and time were determined using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA analysis for multiple comparisons and post hoc testing using the Mann-Whitney U test. In the vehicle group, numerous plaques completely formed in the cortex by nine months of age. The development of plaques accumulation was accompanied by cerebral microcirculation disturbances, reduction in tissue oxygen supply and metabolic impairment (NADH increase). DRP mitigated microcirculation and tissue oxygen supply reduction – microvascular perfusion was 29.5 ± 5%, and tissue oxygen supply was 22 ± 4% higher than in the vehicle group (p < 0.05). In the DRP group, amyloid plaques deposition was substantially less than in the vehicle group (p < 0.05). Thus, rheological enhancement of blood flow by DRP is associated with reduced rate of beta amyloid plaques deposition in AD mice.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia is a consequence of complex interactions of age-related neurodegeneration and vascular-associated pathologies that presently affect more than 5 million Americans and are projected to increase to 16 million by 2050 [1]. Therapeutic interventions that can prevent, delay the onset, or slow the progression of this form of dementia are urgently needed. The quantitative neuropathologic criteria for AD diagnostics, as well as the main target of treatment, are the degree of deposition of amyloid plaques and Tau protein neurofibrillary tangles [2]. However, treatments aimed to prevent or remove amyloid plaques have not succeeded in preventing/reducing dementia [3, 4]. For the last decade, it has been suggested that chronic brain hypoperfusion and consequent hypoxia could play a direct role in the pathogenesis of AD or promote its development [5–7]. Individuals with low brain perfusion showed significantly larger white matter lesion volumes [8]; atherosclerosis was significantly more extensive in the AD population and was associated with impaired cognitive function [9–11]. However, current treatments of AD have not focused on restoring or improving microvascular perfusion. We propose a new treatment approach using modulation of hemorheology by drag reducing polymers (DRP). DRP are linear, soluble macromolecules that reduce flow separations at blood vessel bifurcations leading to a reduction of pressure gradients across the arterial system and an increase in the precapillary blood pressure enhancing capillary perfusion [12]. In a previous study, we showed that DRP enhance cerebral blood flow and tissue oxygenation [13]. Here we tested the efficacy of hemorheologic enhancement of cerebral perfusion by drag-reducing polymers for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

2. Materials and Methods

Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of New Mexico under the Animal Protocol #200640. As an AD model, we used six-week-old male double transgenic AD mice (B6C3-Tg(APPswe, PSEN1dE9) 85Dbo/Mmjax), obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). One transgene encoded a mouse/human chimeric amyloid-β (A4) precursor protein containing the double Swedish mutations (APPswe; K595 N/M596 L). The second transgene for human PS1 contained a deletion of exon 9 (dE9), corresponding to an early-onset form of AD. In this model, numerous plaques completely form in the hippocampus and cortex by nine months of age.

The overall design of the study.

DRP or vehicle (saline) were i.v. injected every week starting four months of age till 12 months of age (10 mice/group). In-vivo 2-photon laser scanning microscopy was used to evaluate amyloid plaques development, cerebral microcirculation, and tissue oxygen supply/metabolic state. The imaging sessions were repeated once a month till 12 months of age.

DRP preparation.

Polyethylene oxide (PEO, MW ~4000 kDa) was dissolved in saline to 0.1% (1000 ppm), dialyzed against saline using a 50 kD cutoff membrane, diluted in saline to 50 ppm, slow rocked for ~2 hours, and then sterilized using a 0.22 μm filter [13].

Two-Photon Laser Scanning Microscopy.

For long-term in-vivo imaging of mouse cortex, we used a polished and reinforced thinned-skull window, avoiding skin re-incision/stitching and preventing bone re-grow [14]. Plaques, microcirculation, and tissue oxygen supply were visualized using Olympus BX 51WI upright microscope and water-immersion XLUMPlan FI 20x/0.95W objective as previously described [13]. Excitation was provided by a Prairie View Ultima multiphoton laser scan unit powered by a Millennia Prime 10 W diode laser source pumping a Tsunami Ti: sapphire laser, centered at 774 nm (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA). Band-pass-filtered epifluorescence (560–660 nm) for fluorescent serum (tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (dextran, 500 kDa in physiological saline, 5 % wt/vol) and (425–475) nm for NADH was collected by photomultiplier tubes of the Prairie View Ultima system. Red blood cell flow velocity was measured in microvessels ranging from 3-50 μm diameter up to 500 μm below the surface of the parietal cortex, as described previously with[13]. NADH autofluorescence measurement was used to evaluate mitochondrial activity (metabolic status) and tissue oxygenation [13]. The amyloid plaques were evaluated at separate day from TAMRA and NADH by second harmonic generation (387 nm emission peak) and i.v. labeling with 0.001% of thioflavin S (450 nm emission peak) [15]. In offline analyses using NIH ImageJ software, three-dimensional anatomy of the vasculature in areas of interest was reconstructed from two-dimensional (planar) scans of the fluorescence intensity obtained at successive focal depths in the cortex (XYZ stack). Beta amyloid plaques were counted in an imaging volume of 0.075 mm3. The data were combined, averaged and normalized from both thioflavin S staining and SHG to 4 months of age (start of the treatment).

Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA by independent Student’s t-test or Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests where appropriate. Differences between groups and time were determined using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA analysis for multiple comparisons and post hoc testing using the Mann-Whitney U test. Variables are expressed as mean ± standard error. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

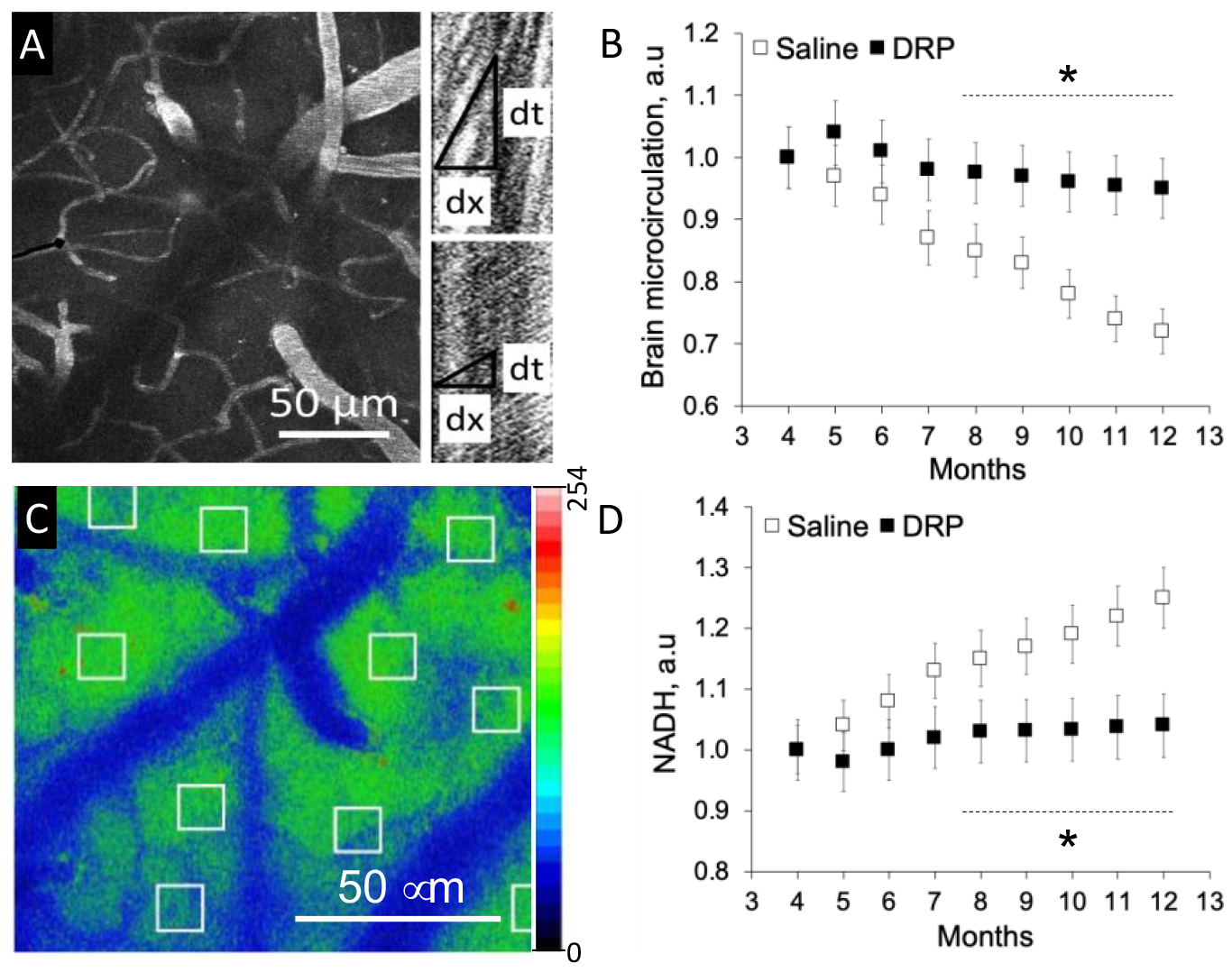

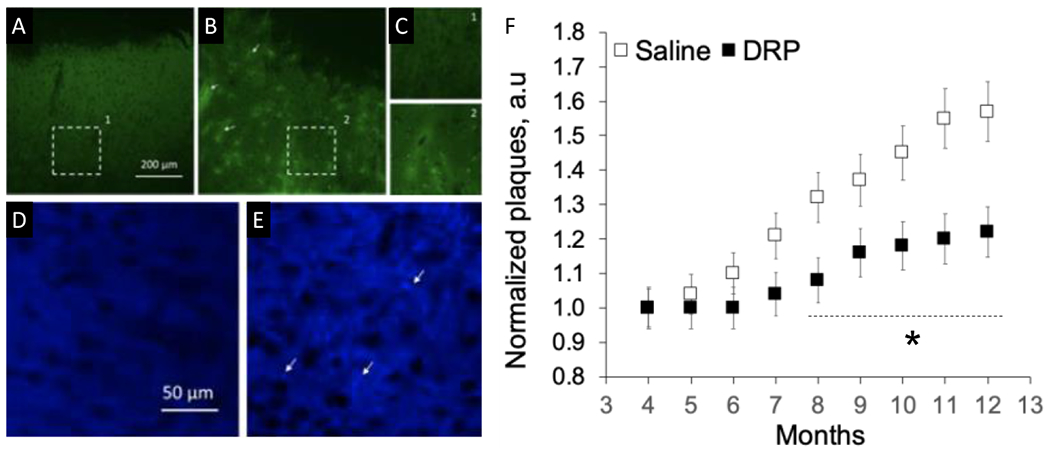

In the vehicle group, numerous plaques completely formed in the cortex by nine months of age. The development of plaques accumulation was accompanied by cerebral microcirculation disturbances, reduction in tissue oxygen supply and metabolic impairment (NADH increase), (Fig. 1, 2). DRP mitigated impairment of microcirculation and tissue oxygen supply – microvascular perfusion was 29.5 ± 5%, and tissue oxygen supply was 22 ± 4% higher than in the vehicle group by the end of the monitoring period (Fig 1, p < 0.05 from the saline group). In the DRP group, amyloid plaques deposition was substantially less than in the vehicle group (Fig 2, p < 0.05 from the saline group).

Fig. 1. Weekly treatment with drag reducing polymers (DRP) mitigate microcirculation reduction and improve tissue oxygen supply during Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) development.

A. Representative micrograph of a region from which microvascular flow was recorded (maximum intensity projection of five planar scans acquired with 10 mm steps, starting at 50 mm from brain surface). Right: Line-scan data for blood flow velocities in the outlined capillary (black line) in the left panel indicating the baseline RBC flow velocity (top scan) and its increase after DRP injection (bottom scan). The slope of the stripes inversely reflects RBC flow velocity. B. Cerebral microvascular perfusion dynamics. C. Representative micrograph of NADH autofluorescence in mouse cortex. D. NADH autofluorescence dynamics. Data presented as a mean ± SEM, N=10 per group, *p<0.05.

Fig. 2. Weekly treatment with drag reducing polymers (DRP) ameliorates β amyloid plaques deposition formation during Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) development.

A. Micrograph of thioflavin S stained saline-treated mouse cortex showing no fluorescence at 4 months and B. Bright β-amyloid plaques fluorescence (thioflavin S) at 12 months of AD development. C. Magnified views of the areas outlined in A and B. D. Micrographs with no β-amyloid plaques visible from the second harmonic generation (SHG) signal at 4 months in DRP-treated mouse brain and E. Bright β-amyloid plaques (SHG) signal at 12 months of AD development. F. Graph showing attenuation of b-amyloid plaques deposition in DRP group. Data presented as mean ± SEM, N=10 per group, *p<0.05, white arrows point plaques depositions.

Our work demonstrated that rheological enhancement of cerebral blood flow and tissue oxygen supply by DRP is associated with a decrease in beta amyloid plaques deposition in the cortex of AD double transgenic B6C3-Tg(APPswe, PSEN1dE9) 85Dbo/Mmjax mice. The mechanisms of this decrease in beta amyloid plaques deposition might include improvement of cerebral microvascular circulation, improved tissue oxygen supply, blood brain barrier preservation, and related reduction in inflammation.

DRPs increase the arteriolar blood volume flow via the increase of flow velocity by reducing flow separations and vortices at vessel bifurcations and decreasing pressure loss across the arterial network due to the viscoelastic properties of DRP [12]. This leads to a rise in pre-capillary blood pressure, thus enhancing capillary perfusion, countering capillary stasis, increasing the density of functioning capillaries and the number of red blood cells passing through capillaries to improve tissue oxygenation [12].

We have also previously shown that DRP attenuates blood brain barrier (BBB) degradation in traumatic brain injury (TBI) [13]. In this work, we have also observed better preserved BBB. It is known that the interaction between Aβ and the BBB affects the progression of AD [16]. Beta amyloid deposition leads to the destruction of the integrity and function of the BBB. BBB dysfunction, in turn, promotes beta amyloid production and accelerates its deposit in the brain [16]. Thus, better preserved BBB and reduced inflammation also could be involved in the mitigation of beta amyloid deposition, which could be another mechanism of DRP in delaying AD.

Another recently possible mechanism is the ability of DRP to reduce the near-wall cell-free layer [12], which increases wall shear stress, promoting the release of nitric oxide and vasodilation. Increased near-wall shear stress and occupation of the near-wall space by RBC, due to the presence of DRP in the blood, may explain the significant reduction in the inflammatory reaction potentially due to reduction of the near-wall rolling leukocytes, their attachment to vessel walls, and extravasation that may also add to the reduction of plaques deposition.

4. Conclusions

Rheological enhancement of cerebral blood flow and tissue oxygen supply by DRP is associated with a decrease in beta amyloid plaques deposition in the cortex of AD double transgenic B6C3-Tg(APPswe, PSEN1dE9) 85Dbo/Mmjax mice. The mechanisms of this decrease in beta amyloid plaques deposition might include improvement of cerebral microvascular circulation, improved tissue oxygen supply, blood brain barrier preservation, and related reduction in inflammation

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by RSF 22-45-04406, NIH 8P30GM103400 and R01NS112808.

5 References

- 1.2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. (2021) 17(3):327–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood JG, Mirra SS, Pollock NJ, et al. (1986) Neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer disease share antigenic determinants with the axonal microtubule-associated protein tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83(11):4040–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, et al. (2008) Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet 9;372(9634):216–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maarouf CL, Daugs ID, Kokjohn TA, et al. (2010)The biochemical aftermath of anti-amyloid immunotherapy. Mol Neurodegener 7;5:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorelick PB, et al. , (2011) Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 42(9):2672–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamel E (2015) Cerebral circulation: function and dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 65(4):317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maier FC, Wehrl HF, Schmid AM, et al. (2014) Longitudinal PET-MRI reveals β-amyloid deposition and rCBF dynamics and connects vascular amyloidosis to quantitative loss of perfusion. Nat Med 20(12):1485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A, Ikram MA, et al. (2008) Total cerebral blood flow and total brain perfusion in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28(2):412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalback W, Esh C, Castaño EM, et al. (2004) Atherosclerosis, vascular amyloidosis and brain hypoperfusion in the pathogenesis of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Res 26(5):525–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roher AE, Esh C, Rahman A, et al. (2004) Atherosclerosis of cerebral arteries in Alzheimer disease. Stroke 35(11Suppl 1):2623–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roher AE, Tyas SL, Maarouf CL, et al. (2011) Intracranial atherosclerosis as a contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Alzheimers Dement 7(4):436–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kameneva MV (2012) Microrheological effects of drag-reducing polymers in vitro and in vivo. International Journal of Engineering Science 59:168–183. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bragin DE, Kameneva MV, Bragina OA, et al. (2016) Rheological effects of drag-reducing polymers improve cerebral blood flow and oxygenation after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37(3):762–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih AY, Mateo C, Drew PJ, et al. (2012) A polished and reinforced thinned-skull window for long-term imaging of the mouse brain. J Vis Exp 7(61):3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwan AC, Duff K, Gouras GK, et al. (2009) Optical visualization of Alzheimer’s pathology via multiphoton-excited intrinsic fluorescence and second harmonic generation. Opt Express 2009 2;17(5):3679–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D, Chen F, Han Z, et al. (2021) Relationship Between Amyloid-β Deposition and Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 19;15:695479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]