Abstract

Background

The causal pathway between complications after pancreatic cancer resection and impaired long-term survival remains unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of complications after pancreatic cancer resection on disease-free interval and overall survival, with adjuvant chemotherapy as a mediator.

Methods

This observational study included all patients undergoing pancreatic cancer resection in the Netherlands (2014–2017). Clinical data were extracted from the prospective Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Audit. Recurrence and survival data were collected additionally. In causal mediation analysis, direct and indirect effect estimates via adjuvant chemotherapy were calculated.

Results

In total, 1071 patients were included. Major complications (hazards ratio 1.22 (95 per cent c.i. 1.04 to 1.43); P = 0.015 and hazards ratio 1.25 (95 per cent c.i. 1.08 to 1.46); P = 0.003) and organ failure (hazards ratio 1.86 (95 per cent c.i. 1.32 to 2.62); P < 0.001 and hazards ratio 1.89 (95 per cent c.i. 1.36 to 2.63); P < 0.001) were associated with shorter disease-free interval and overall survival respectively. The effects of major complications and organ failure on disease-free interval (−1.71 (95 per cent c.i. −2.27 to −1.05) and −3.05 (95 per cent c.i. −4.03 to −1.80) respectively) and overall survival (−1.92 (95 per cent c.i. −2.60 to −1.16) and −3.49 (95 per cent c.i. −4.84 to −2.03) respectively) were mediated by adjuvant chemotherapy. Additionally, organ failure directly affected disease-free interval (−5.38 (95 per cent c.i. −9.27 to −1.94)) and overall survival (−6.32 (95 per cent c.i. −10.43 to −1.99)). In subgroup analyses, the association was found in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy, but not in patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy.

Conclusion

Major complications, including organ failure, negatively impact survival in patients after pancreatic cancer resection, largely mediated by adjuvant chemotherapy. Prevention or adequate treatment of complications and use of neoadjuvant treatment may improve oncological outcomes.

This nationwide observational cohort study included 1052 patients and showed that major complications, including organ failure, have a negative impact on disease-free interval and overall survival after resection of pancreatic cancer. This effect was largely mediated by the use of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Introduction

Optimal treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma consists of resection in combination with chemotherapy1–5. Unfortunately, most patients develop disease recurrence after resection within a median disease-free interval (DFI) of 10 months, greatly contributing to the poor 5-year survival of 12–17 per cent after resection3–5.

Pancreatic resection is technically challenging and is associated with around 50 per cent risk of complications1,6. Important short-term complications are postoperative pancreatic fistula and biliary leakage, which can lead to associated life-threatening events like sepsis, severe bleeding, organ failure, and death7–9. Other complications are leakage of the gastrojejunostomy, delayed gastric emptying, and pneumonia1,10. Previous studies have shown an association between postoperative complications and worse DFI and overall survival (OS) in colorectal, oesophageal, and gastric cancer11–14. For pancreatic cancer, the occurrence of major complications (that is Clavien–Dindo grade greater than or equal to III) has been identified as a potential risk factor for recurrence15–19. However, the contribution of individual complications is unknown. Besides, delayed recovery because of postoperative complications influences the patient’s eligibility to receive or complete adjuvant chemotherapy. Considering that adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with improved survival, the effect of complications on survival is expected to be largely mediated by the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy20–22. This hypothesis, however, has never been tested before. The causal pathway between complications and long-term oncological outcomes could also be explained by a direct effect. It has been shown that progression of microscopic residual disease after resection is promoted by a systemic inflammatory response17,23–25. To date, it remains unclear to what extent these pathways contribute to shorter DFI and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Relationships between certain factors and outcomes are traditionally assessed by regression analyses. With these methods, however, it is not possible to provide conclusions on the underlying mechanisms of identified associations. Insights in the causal pathway of postoperative complications to impaired survival and the extent of the mediation effect of adjuvant chemotherapy may, however, be valuable in determining the focus for improving oncological outcomes. To decompose the total effect of a factor into a direct effect and an indirect (mediated) effect, causal mediation analysis has been introduced26,27.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the impact of postoperative complications after pancreatic resection for pancreatic cancer on disease recurrence and survival, and to evaluate the role of adjuvant chemotherapy as a mediator.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

A nationwide, observational cohort study was performed. All patients undergoing resection for histologically proven primary pancreatic cancer between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2017 in all 18 centres collaborating in the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group were included. Amongst these centres were nine medium-/low-volume centres and nine high-volume centres, including eight academic teaching hospitals. The cut-off was defined as less than or equal to 45 for medium-/low-volume centres versus greater than 45 pancreatic resections annually for high-volume centres. This was based on the median of 45 resections performed in the Netherlands between 2014 and 2015. Exclusion criteria were death within 90 days after resection, (pathological) metastatic disease at surgery, and neoadjuvant treatment. This study was approved by the scientific committee of the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group and the ethics review committee of the participating centres (METC 18-036). They waived the need for informed consent. The authors adhered to the STROBE guidelines28. The conducted research was not preregistered.

Data collection

Baseline and perioperative data were extracted from the mandatory, prospective Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Audit, including age, sex, BMI, patient history, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score, information on vascular involvement on preoperative imaging, and details of the pancreatic resection. The patient history was used to calculate the Charlson co-morbidity index (CCI) with the MDCalc CCI calculator (without accounting for age)29. Furthermore, data on tumour biology and resection margin status were extracted. Additional data on complications, adjuvant chemotherapy, recurrence, and survival were collected retrospectively from hospital records. Postoperative complications included postoperative pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage, gastrojejunostomy leakage, and biliary leakage. All grade B/C complications, according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) and International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) classifications, were assumed to be clinically relevant30,31. Major complications were defined as Clavien–Dindo grade greater than or equal to III32. Organ failure was defined as failure of one of more organ systems. Definitions of all complications are provided in Table S1.

Outcomes

The main outcomes of interest were DFI and OS. DFI was defined as the time from the date of resection to the date of recurrence diagnosis or last follow-up33. Recurrence had to be either pathologically proven or suspected through cross-sectional imaging, confirmed by consensus at a multidisciplinary team meeting. During the study interval, follow-up varied between centres and commonly consisted of a periodic, symptomatic follow-up without routine serum tumour marker testing or imaging. However, a proportion of patients received standardized serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 testing and cross-sectional imaging during postoperative surveillance, after shared decision-making or trial participation. OS was defined as the time from the date of surgery to either the date of death from any cause or last follow-up. If recurrence or survival data were missing, patients were censored at the date of last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are presented using descriptive characteristics. Missing data on baseline characteristics were considered missing at random and managed by multiple imputation according to a Markov chain Monte Carlo method (five imputations, 10 iterations) (Table 1 and Table S2)34. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to calculate the association between postoperative complications and DFI and OS. Results are presented as hazards ratio (HR) with corresponding 95 per cent c.i.. This was done for each individual complication as well as for major complications altogether. Exploratory analyses were performed for patients after pancreatoduodenectomy and for patients after distal pancreatectomy. Furthermore, OS and DFI were evaluated for major complications and organ failure in the total patient cohort as well as for patients after pancreatoduodenectomy and after distal pancreatectomy using Kaplan–Meier analysis. The 1- and 3-year survival rates are also described in this analysis. Outcomes were compared using the log rank test and are presented as median with 95 per cent c.i.

Table 1.

Patient, tumour, and treatment characteristics of 1071 patients after resection for pancreatic cancer

| Variable | All patients, n = 1071 | Missing | After imputation, n = 1071 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 578:493 | – | 578:493 |

| Age (years), mean(s.d.) | 67(9) | – | 67(9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | – | 9 (1) | – |

| <25 | 597 (56) | 602 (56) | |

| ≥25 | 465 (43) | 469 (44) | |

| Charlson co-morbidity index | – | 67 (6) | – |

| <2 | 626 (58) | 668 (62) | |

| ≥2 | 378 (35) | 403 (38) | |

| ASA classification | – | 16 (1) | – |

| I–II | 796 (74) | 807 (75) | |

| III–IV | 259 (24) | 264 (25) | |

| ECOG performance score at primary diagnosis | – | 322 (30) | – |

| 0–1 | 663 (62) | 942 (88) | |

| 2–4 | 86 (8) | 129 (12) | |

| Preoperative serum CA 19-9 in U/mL, median (i.q.r.) | 150 (36–500) | 342 (32) | 151 (36–502) |

| Preoperative bilirubin (µmol/l), median (i.q.r.) | 32 (10–111) | 449 (42) | 31 (10–111) |

| Method of surgery* | – | 16 (1) | – |

| Open | 901 (84) | 913 (85) | |

| Laparoscopic | 106 (10) | 108 (10) | |

| Robot | 48 (4) | 50 (5) | |

| Type of resection | – | 26 (2) | – |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 854 (80) | 875 (82) | |

| Body/tail resection | 147 (14) | 152 (14) | |

| Total pancreatectomy | 36 (3) | 36 (3) | |

| Other | 8 (1) | 8 (1) | |

| Location of tumour | – | 51 (5) | – |

| Head | 862 (80) | 907 (85) | |

| Body/tail | 158 (15) | 164 (15) | |

| Vascular resection | 275 (26) | 3 (0) | 275 (26) |

| Microscopic perineural invasion | 795 (74) | 179 (17) | 945 (88) |

| Microscopic lymphovascular invasion | 554 (52) | 266 (25) | 716 (67) |

| Tumour size (mm), median (i.q.r.)† | 30 (25–40) | 16 (1) | 30 (25–40) |

| Tumour differentiation | – | 124 (12) | – |

| Well/moderate | 657 (61) | 742 (69) | |

| Poor | 290 (27) | 329 (31) | |

| Total number of resected lymph nodes, median (i.q.r.) | 15 (10–20) | 14 (1) | 15 (10–20) |

| No. of positive lymph nodes, median (i.q.r.) | 2 (0–5) | 6 (1) | 2 (0–5) |

| TNM stage 8th AJCC edition | – | 89 (8) | – |

| ≤Stage 2a | 262 (24) | 295 (28) | |

| ≥Stage 2b | 720 (67) | 776 (72) | |

| Resection margin status (mm) | – | 26 (2) | – |

| R0 >1.0 | 503 (47) | 519 (48) | |

| R1 ≤1.0 | 542 (51) | 552 (52) | |

| Major complications‡ | 306 (29) | 2 (0) | – |

| Length of hospital stay (days), median (i.q.r.) | 11 (8–16) | 3 (0) | – |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 663 (62) | 45 (4) | – |

| Type of adjuvant chemotherapy§ | – | 38 (6) | – |

| Gemcitabine monotherapy | 546 (82) | ||

| FOLFIRINOX | 8 (1) | ||

| Gemcitabine combination therapy | 62 (9) | ||

| Other | 9 (1) | ||

| No. of cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy, median (i.q.r.)§ | 6 (4–6) | 96 (14) | – |

| Greater than or equal to 80% of prescribed cycles completed§ | 400 (60) | 100 (15) | – |

| Overall survival (months), median (95% c.i.) | 20 (19 to 22) | 25 (2) | – |

| Disease-free interval (months), median (95% c.i.) | 15 (14 to 16) | 25 (2) | – |

| Recurrence | 753 (70) | 17 (2) | – |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. *Converted laparoscopic procedures are included as open procedures. †Maximum diameter of the tumour. ‡Clavien–Dindo classification grade greater than or equal to III; all postoperative complications requiring surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention, or causing organ failure or death. §Calculated in a subset of patients who started with adjuvant chemotherapy (663 patients). s.d., standard deviation; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; CA, carbohydrate antigen; i.q.r., interquartile range; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; FOLFIRINOX, 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin/irinotecan/oxaliplatin chemotherapy.

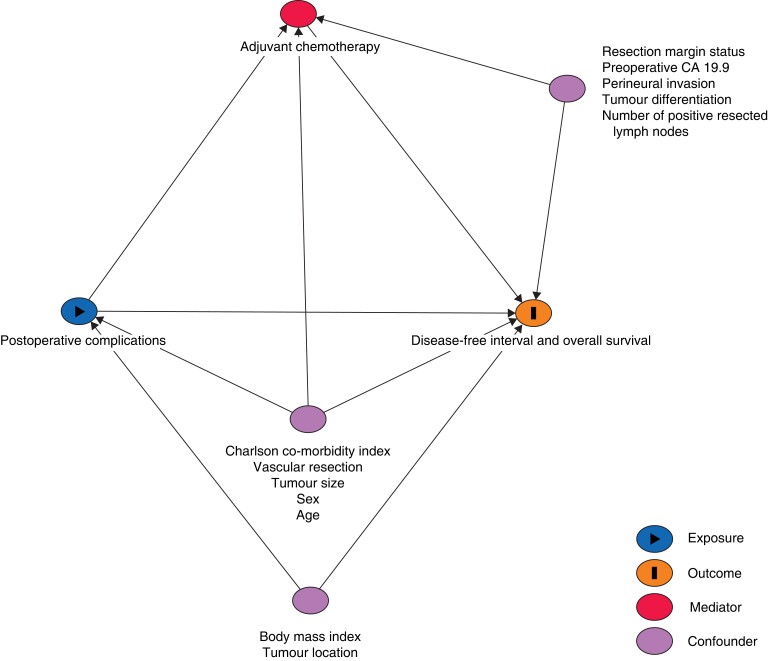

To address potential confounders for the effect of complications on DFI and OS, a directed acyclic graph (DAG) was designed based on the literature and clinical relevance (http://www.daggity.net) (Fig. 1). Multivariable analyses of the total effect of postoperative complications on DFI and OS were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, CCI, tumour size, tumour location, and vascular resection.

Fig. 1.

Directed acyclic graph to identify confounders in the association between major postoperative complications and adjuvant chemotherapy, and disease-free interval and overall survival after resection of pancreatic cancer

CA, carbohydrate antigen.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was considered a mediator for the effect of postoperative complications on DFI and OS, which means that it is an effect of the exposure (complications) and a cause of the outcome (survival). This implies that impaired survival in patients with postoperative complications might be explained by their inability to start with adjuvant chemotherapy because of a delayed recovery26,35,36. To assess the extent of the mediation effect and investigate potential direct effects, a causal mediation analysis was performed.

In this analysis, the total effect of complications on survival is decomposed into a direct effect and an indirect effect via adjuvant chemotherapy26. The statistical approach is based on three independent regression analyses, which are used to calculate estimates for each of these effects. This enables the calculation of counterfactual outcomes if the observed mediation status (that is adjuvant chemotherapy) was hypothetically set to another level27. The total effect was calculated using an accelerated failure time (AFT) model with Weibull distribution26. The indirect effect was based on two calculations: the independent association between the complication and adjuvant chemotherapy was established using a logistic regression model adjusted for relevant confounders (that is age, sex, CCI, tumour size, and vascular resection); and the independent association between adjuvant chemotherapy and survival was assessed using an AFT model adjusted for the concerning complication and potential confounders (that is age, sex, number of resected positive lymph nodes, tumour differentiation, resection margin status, tumour size, preoperative CA 19-9, and neural invasion). Finally, the unstandardized total, direct and indirect effects were computed with 100 simulations. Results are presented as effect estimates, derived from the causal mediation analysis as average causal mediation effects (ACME; the indirect effect) and average direct effects (ADE; the direct effect). For example, a calculated negative indirect effect indicates a negative impact of the postoperative complication on survival that is fully attributable to not receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. A calculated negative direct effect indicates that the systemic inflammatory response leading to local tumour growth fully explains the impaired survival. Results from the independent regression analyses are presented as odds ratios (OR) (resulting from the logistic regression model) and HR (calculated using the AFT model) with corresponding 95 per cent c.i.

Statistical analysis was performed with R language environment (version 1.1.463; http://www.R-project.org), including the ‘mice’ and ‘mediation’ packages. A two-sided P value <0.050 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 1278 patients underwent resection for pancreatic cancer, and 207 patients were excluded due to death within 90 days after resection (64 patients; 5.0 per cent), metastasized disease at the time of surgery (11 patients; 0.8 per cent), and neoadjuvant treatment (132 patients, 10.3 per cent). The final cohort included 1071 patients. The median follow-up interval was 54 (interquartile range (i.q.r.) 28–72) months. In total, 753 patients (70.3 per cent) developed recurrence after a median of 15 (95 per cent c.i. 14 to 16) months. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered in 663 patients (61.9 per cent). Median OS was 20 (95 per cent c.i. 19 to 22) months. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Postoperative complications

Among all complications, delayed gastric emptying (130 patients; 12.1 per cent), postoperative pancreatic fistula (82 patients; 7.7 per cent), pneumonia (76 patients; 7.1 per cent), and post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage (50 patients; 4.7 per cent) were the most common (Table 2). Two patients (less than 1 per cent) suffered from leakage of the gastrojejunostomy. In total, 306 patients (28.6 per cent) suffered from one or more major complications. Organ failure occurred in 42 patients (3.9 per cent). Admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) because of a complicated hospitalization course was required in 115 patients (10.7 per cent).

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis to assess the impact of postoperative complications on disease-free interval and overall survival in 1071 patients after resection of pancreatic cancer

| Complications | Patients | Disease-free interval | Overall survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% c.i.) | P | HR (95% c.i.) | P | ||

| Pancreatic fistula | 82 (7.7) | 1.30 (0.99 to 1.70) | 0.059 | 1.28 (0.99 to 1.65) | 0.063 |

| Post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage | 50 (4.7) | 1.14 (0.81 to 1.60) | 0.450 | 1.17 (0.86 to 1.61) | 0.316 |

| Biliary leakage | 28 (2.6) | 1.11 (0.70 to 1.76) | 0.653 | 1.07 (0.69 to 1.65) | 0.769 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 130 (12.1) | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.30) | 0.677 | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.23) | 0.965 |

| Pneumonia | 76 (7.1) | 1.21 (0.92 to 1.58) | 0.174 | 1.28 (0.99 to 1.64) | 0.056 |

| Major complications | 306 (28.6) | 1.22 (1.04 to 1.43) | 0.015 | 1.25 (1.08 to 1.46) | 0.003 |

| Organ failure | 42 (3.9) | 1.86 (1.32 to 2.62) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.36 to 2.63) | <0.001 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Confounders: age, sex, BMI, Charlson co-morbidity index, tumour size, tumour location, and vascular resection. HR, hazards ratio.

Of 306 patients with major complications, 150 patients (49.0 per cent) received adjuvant chemotherapy, as compared with 511/763 patients (67.0 per cent) without major complications (P < 0.001). Of patients with major complications, 95 patients (31.0 per cent) completed greater than 80 per cent of the prescribed cycles, which was the case for 306 patients (40.1 per cent) without major complications (P = 0.007). Gemcitabine monotherapy was administered in 132/150 patients (88.0 per cent) with major complications who received adjuvant therapy, gemcitabine combination therapy in 16/150 patients (10.7 per cent), and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin/irinotecan/oxaliplatin chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX) in one of 150 patients (0.7 per cent). In 511 patients without major complications who received adjuvant therapy, 443 patients (86.7 per cent) received gemcitabine monotherapy, 51 patients (10.0 per cent) received gemcitabine combination therapy, and 8 patients (1.6 per cent) received FOLFIRINOX (P = 0.768). In patients with organ failure, adjuvant chemotherapy was started in 11/42 patients (26.2 per cent) versus 637/952 patients (66.9 per cent) without organ failure (P < 0.001).

Survival analysis

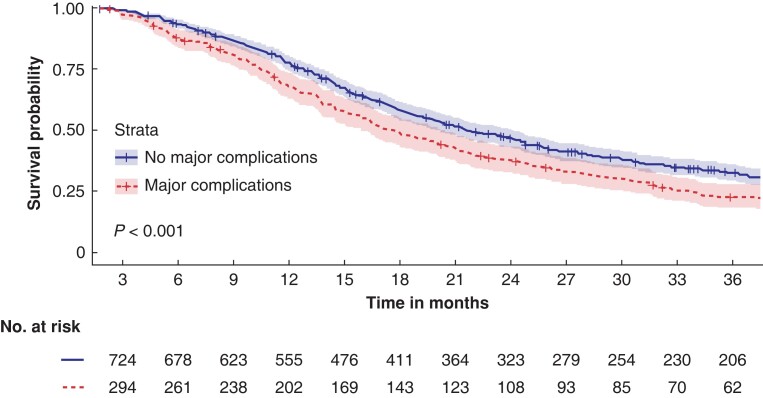

Results of the univariable analysis are presented in Table S3. The median OS for 304 patients with major complications was 18 (95 per cent c.i. 15 to 20) months versus 22 (95 per cent c.i. 20 to 24) months for 741 patients without major complications (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In this analysis, 26 patients (5.1 per cent) were excluded because of missing data. At 1 year after resection, 66.4 per cent of patients (202/304 patients) with major complications were still alive versus 74.9 per cent of patients (555/741 patients) without major complications. The 3-year survival was 20.4 per cent (62/304 patients) versus 27.8 per cent (206/741 patients) respectively.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival in 1045 patients with and without major postoperative complications

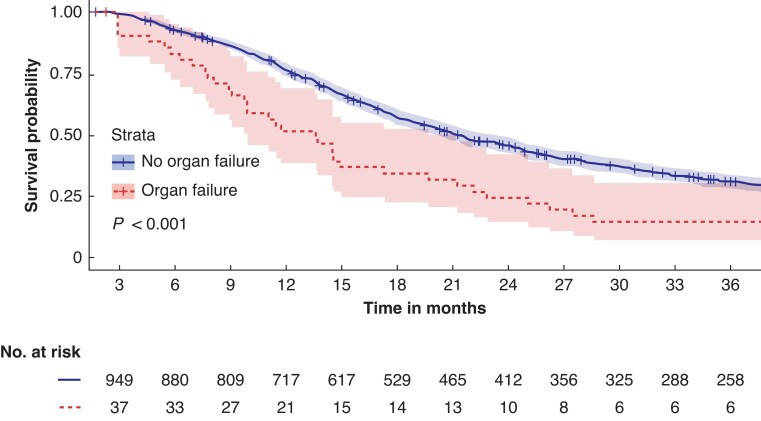

In 42 patients with organ failure, the median OS was also decreased (13 (95 per cent c.i. 10 to 20) months), as compared with 970 patients without organ failure (21 (95 per cent c.i. 20 to 23) months) (P < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 3. In this analysis, 59 patients (6.1 per cent) were excluded because of missing data. One-year survival was 50 per cent (21/42 patients) versus 73.9 per cent (717/970 patients) respectively. Three-year survival was 14 per cent (6/42 patients) versus 26.6 per cent (258/970 patients) respectively.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival in 1012 patients with and without postoperative organ failure

In multivariable analysis, individual postoperative complications were not statistically significant associated with DFI and OS (Table 2). Major complications were associated with both a reduction of DFI and OS (HR 1.22 (95 per cent c.i. 1.04 to 1.43); P = 0.015 and HR 1.25 (95 per cent c.i. 1.08 to 1.46); P = 0.003 respectively). Organ failure was also associated with reduced DFI and OS (HR 1.86 (95 per cent c.i. 1.32 to 2.62); P < 0.001 and HR 1.89 (95 per cent c.i. 1.36 to 2.63); P < 0.001 respectively).

Exploratory analyses

In the subgroup of patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy, post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage was associated with shorter OS (HR 1.40 (95 per cent c.i. 1.01 to 1.94); P = 0.042) (Table S4). Major complications were associated with both reduced DFI and OS (HR 1.29 (95 per cent c.i. 1.08 to 1.53); P < 0.001 and HR 1.31 (95 per cent c.i. 1.11 to 1.54); P = 0.002 respectively). Furthermore, organ failure was associated with both DFI and OS (HR 2.12 (95 per cent c.i. 1.46 to 3.07); P < 0.001 and HR 2.07 (95 per cent c.i. 1.44 to 2.97); P < 0.001 respectively). In patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy, no significant associations with DFI and OS were seen (Table S5).

In patients after pancreatoduodenectomy, the median OS for 249 patients with major complications was 17 (95 per cent c.i. 15 to 20) months versus 21 (95 per cent c.i. 20 to 24) months in 603 patients without major complications (P < 0.001) (Fig. S1). In this analysis, 23 patients (3.1 per cent) were excluded due to missing data. In 34 patients with organ failure, the median OS after pancreatoduodenectomy was 10 (95 per cent c.i. 8 to 21) months versus 20 (95 per cent c.i. 19 to 22) months in 789 patients without organ failure (P < 0.001) (Fig. S2). Data of 52 patients (5.9 per cent) were missing. For patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy, the median OS was 23 (95 per cent c.i. 16 to 49) months in 42 patients with major complications versus 26 (95 per cent c.i. 22 to 32) months in 109 patients without major complications (P = 0.860) (Fig. S3). In this analysis, one patient (1 per cent) was excluded due to missing data. In addition, four patients suffering from organ failure after distal pancreatectomy had a median OS of 16 (95 per cent c.i. 11 to not applicable) months versus 26 (95 per cent c.i. 23 to 32) months in 146 patients without organ failure (P = 0.750) (Fig. S4). Excluded were two patients (1 per cent), due to missing data.

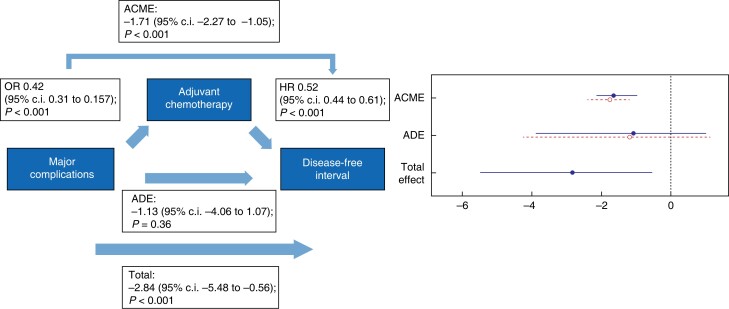

Causal mediation analysis

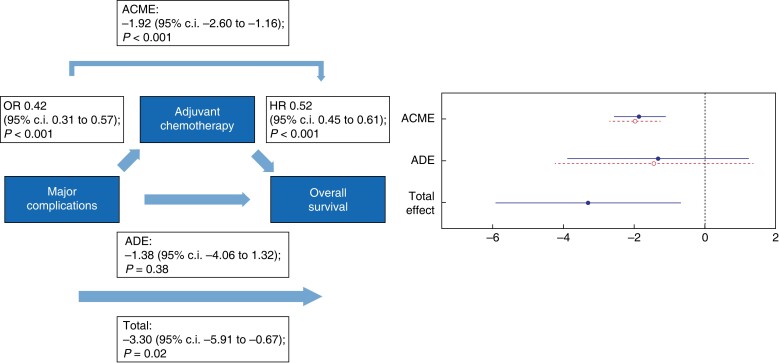

Causal mediation analysis was performed for major complications (Figs 4, 5) and organ failure (Figs 6, 7). Major complications had a negative total effect on DFI (−2.84 (95 per cent c.i. −5.48 to −0.56); P < 0.001) and OS (−3.30 (95 per cent c.i. −5.91 to −0.67); P = 0.015). This effect was, however, fully mediated via the start of adjuvant chemotherapy since an indirect effect on DFI (−1.71 (95 per cent c.i. −2.27 to −1.05); P < 0.001) and OS (−1.92 (95 per cent c.i. −2.60 to −1.16); P < 0.001) was found and major complications did not have a direct effect on both DFI (−1.13 (95 per cent c.i. −4.06 to 1.07); P = 0.360) and OS (−1.38 (95 per cent c.i. −4.06 to 1.32); P = 0.380).

Fig. 4.

Causal mediation analysis for adjuvant chemotherapy as a mediator in the causal pathway from major postoperative complications to disease-free interval

ACME, average causal mediation effect; OR, odds ratio, HR, hazards ratio; ADE, average direct effect.

Fig. 5.

Causal mediation analysis for adjuvant chemotherapy as a mediator in the causal pathway from major postoperative complications to overall survival

ACME, average causal mediation effect; OR, odds ratio, HR, hazards ratio; ADE, average direct effect.

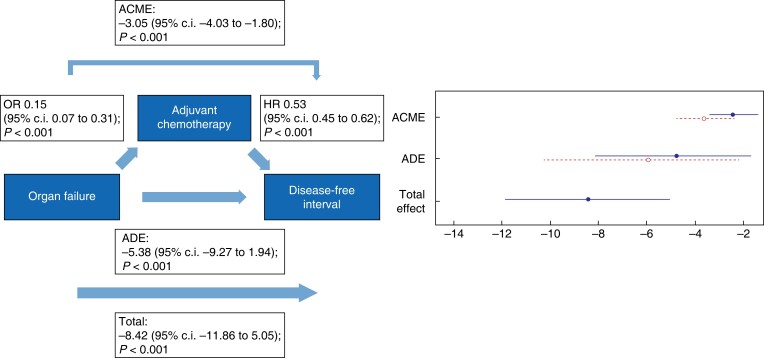

Fig. 6.

Causal mediation analysis for adjuvant chemotherapy as a mediator in the causal pathway from postoperative organ failure to disease-free interval

ACME, average causal mediation effect; OR, odds ratio, HR, hazards ratio; ADE, average direct effect.

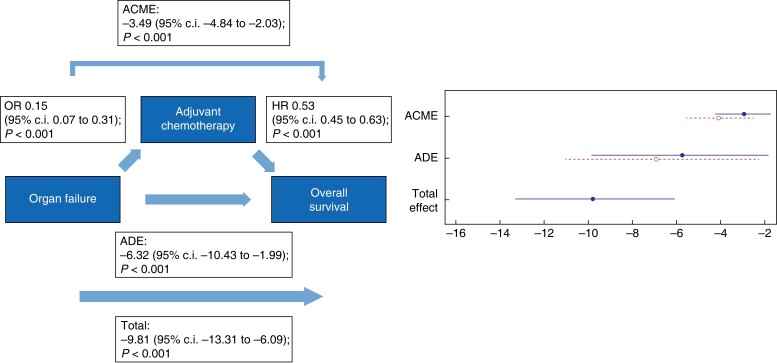

Fig. 7.

Causal mediation analysis for adjuvant chemotherapy as a mediator in the causal pathway from postoperative organ failure to overall survival

ACME, average causal mediation effect; OR, odds ratio, HR, hazards ratio; ADE, average direct effect.

The negative total effect of organ failure on DFI (−8.42 (95 per cent c.i. −11.86 to 5.05); P < 0.001) was only partly mediated via the start of adjuvant chemotherapy since both a direct effect (−5.38 (95 per cent c.i. −9.27 to −1.94); P < 0.001) and an indirect effect (−3.05 (95 per cent c.i. −4.03 to −1.80); P < 0.001) were found. The same accounts for the total effect of organ failure on OS (−9.81 (95 per cent c.i. −13.31 to −6.09); P < 0.001), in which the analysis showed both a negative direct effect (−6.32 (95 per cent c.i. −10.43 to −1.99); P < 0.001) and indirect effect (−3.49 (95 per cent c.i. −4.84 to −2.03); P < 0.001).

Discussion

This nationwide study showed that major complications, including organ failure, after pancreatic cancer resection were significantly associated with both reduced DFI and OS. The negative effect of major complications on survival appeared to be fully mediated by omission of adjuvant chemotherapy. The effect of organ failure on survival was partly mediated by the reduced rate of adjuvant chemotherapy.

The findings of this study are in line with previously published studies on this topic, showing that major complications in general are associated with early recurrence and worse long-term survival15–19. However, these concerned mainly single-centre studies. Moreover, the impact of individual complications on survival and the extent to which adjuvant chemotherapy mediates this effect has not been studied yet. Only two studies compared surgical versus non-surgical and infectious versus non-infectious complications and found no significant difference in survival15,19. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this study is the first to make a clear distinction between individual complications, when investigating their impact on long-term survival. In addition, to the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to elaborate on the underlying mechanisms through which postoperative complications impact long-term oncological outcomes.

Delayed recovery due to postoperative complications decreases the eligibility to start or complete adjuvant chemotherapy16,19,21,23,35. It has been shown that patients who suffer from a complicated hospitalization course often do not undergo adjuvant treatment, which is highly related to survival23. Moreover, patients who suffer from major complications poorly tolerate chemotherapy and its side-effects, and mostly fail to complete the entire treatment schedule16,19. They also have been shown to experience a prolonged interval between resection and initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy17. However, the ESPAC-3 trial showed that completion of all cycles of planned adjuvant chemotherapy rather than early initiation was an independent prognostic factor after resection of pancreatic cancer36. To increase the likelihood of receiving optimal systemic therapy, neoadjuvant treatment is considered a suitable alternative37,38. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to result in down-staging of the tumour, which prolongs DFI and OS37. Furthermore, the rate of postoperative complications might be reduced37. Compliance, that is start and completion rates, with neoadjuvant chemotherapy is reported to be better than with adjuvant chemotherapy39. For patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, therefore, neoadjuvant therapy is recommended as first-choice treatment. The benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, however, needs to be further demonstrated through randomized studies.

Interestingly, the effect of organ failure on survival was only partly mediated through adjuvant chemotherapy. The significant direct effect of organ failure on both DFI and OS suggests the existence of another causal pathway. It has been shown that a systemic inflammatory response induces progression of microscopic residual disease after resection24,25. After the pro-inflammatory ‘hit’ of the surgical trauma, complications lead to secondary activation of the immune system24,40,41. The attendant increase in chemokine and cytokine production enhances tumour progression24,41. In addition, numbers of tumour-infiltrating natural killer (NK) cells and lymphocytes are reduced, leading to an immunosuppressive host. In turn, this contributes to the expansion of residual tumour cells or the formation of micro metastases42. Furthermore, systemic inflammatory response markers were shown to have prognostic value in previous studies19. Therefore, the authors hypothesize that the major pro-inflammatory response associated with organ failure attributes to early disease recurrence and impaired survival24,25,41,43.

Subgroup analysis of patients that underwent a pancreatoduodenectomy also showed that major complications and organ failure were significantly associated with shorter DFI and OS. Furthermore, post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage was significantly associated with shorter OS. For patients who underwent a distal pancreatectomy, no associations were found. Morbidity and mortality rates are known to be lower after distal pancreatectomy, as compared with pancreatoduodenectomy44. However, the absence of an association between complications and DFI and OS in the current study might also be a power issue. A larger patient cohort is necessary to accurately investigate this association in patients after distal pancreatectomy.

Despite many surgical quality improvement initiatives worldwide, postoperative complications do still occur in half of patients after pancreatic cancer resection1,6,45,46. In the Netherlands, this included around 23 per cent of major complications and 2–5 per cent of organ failure, in line with the results of the current study47,48. Therefore, these findings stress the importance of timely recognition and minimally invasive management of complications, before they lead to clinical deterioration47. Recently, the Dutch stepped-wedge randomized PORSCH trial has shown that implementation of an algorithm for early detection and minimally invasive management of complications after pancreatic resection led to an approximate 50 per cent reduction of a composite endpoint of severe bleeding, organ failure, and 90-day mortality rate47. In the context of the current study, this postoperative monitoring strategy may not only reduce postoperative mortality rate but also improve oncological outcomes. The number of patients who started with adjuvant chemotherapy, however, was comparable between both trial arms (53.9 per cent in the intervention group versus 56.1 per cent in the control group). Nevertheless, long-term outcomes of the PORSCH trial, including type of adjuvant chemotherapy, number of cycles, and survival, have to be awaited and can be used to test the findings of the current study. Furthermore, prehabilitation—that is preoperative exercise training to optimize functional deficits, nutritional interventions, psychological support, and coaching towards lifestyle changes—has been shown to reduce the risk of postoperative morbidity rate after pancreatic resection49,50. The implementation of prehabilitation programmes might therefore increase the likelihood of receiving adjuvant chemotherapy.

This study has several limitations. First, causal effect estimates are preferably retrieved from randomized trials. However, if randomization cannot be performed, causal mechanisms underlying identified associations can be investigated with observational data by means of causal inference27,51,52. This can only be done if sufficient data on confounders, such as explicated by a DAG, are available. Since these data were available in the current study, the presented causal mediation analysis is considered to provide a good approximation of the true effect estimates27,52. Second, individual postoperative complications were not significantly associated with worse long-term survival. However, the likelihood of a type II error is increased due to the limited number of events for each complication. These numbers may not be sufficient to substantiate conclusions. The same applies to the low number of events in patients that underwent distal pancreatectomy. Nevertheless, in comparison with previous studies, the patient cohort analysed in this study is relatively large and has a distinctive nationwide set-up. Third, although a prospective database was used for baseline and perioperative data, the retrospective character of the additional data collection has its inherent disadvantages. Confounding by indication might have occurred, since not all patients received standardized follow-up and treatment of recurrence. Therefore, it might be possible that patients who received standardized follow-up imaging and treatment of recurrence had a better a priori prognosis, as compared with patients who did not. Furthermore, varying intervals and frequency of regular follow-up imaging between patients might have influenced both DFI and OS outcomes. However, this reflects daily clinical practice and makes the results highly applicable. Fourth, considerations in shared decision-making that led to initiation, omission, or discontinuation of adjuvant chemotherapy could not be identified. This might have provided insights into the role of postoperative complications for the decision to refrain from adjuvant treatment.

Future research should focus on prevention, early recognition, and adequate treatment of complications, aiming to promote postoperative recovery and increase eligibility for adjuvant treatment. Furthermore, emphasis should be placed on patient selection for neoadjuvant treatment strategies. This might lead to improvement of long-term oncological prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors had complete access to the study data that support the publication. A.C.H., J.C.v.D., I.W.J.M.v.G., L.A.D., H.C.v.S., I.Q.M., and C.H.J.v.E. contributed to the conception and design of the work. A.C.H., J.C.v.D., I.W.M.v.G., and L.A.D. collected all data. A.C.H., J.C.v.D., and L.A.D. performed the data analyses. A.C.H. and J.C.v.D. drafted the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published. A.C.H., J.C.v.D., and I.W.J.M.v.G. share first authorship. L.A.D., H.C.v.S., I.Q.M., and C.H.J.v.E. share senior authorship. This paper is not based on a previous communication to a society or meeting.

Contributor Information

Anne Claire Henry, Department of Surgery, Regional Academic Cancer Center Utrecht, St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Jelle C van Dongen, Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Iris W J M van Goor, Department of Surgery, Regional Academic Cancer Center Utrecht, St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands; Department of Radiation Oncology, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

F Jasmijn Smits, Department of Surgery, Regional Academic Cancer Center Utrecht, St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Anne Nagelhout, Department of Surgery, Regional Academic Cancer Center Utrecht, St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Marc G Besselink, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Cancer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Olivier R Busch, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Cancer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Bert A Bonsing, Department of Surgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Koop Bosscha, Department of Surgery, Jeroen Bosch Hospital, Den Bosch, The Netherlands.

Ronald M van Dam, Department of Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Sebastiaan Festen, Department of Surgery, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Bas Groot Koerkamp, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Cancer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Erwin van der Harst, Department of Surgery, Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Ignace H de Hingh, Department of Surgery, Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

Marion van der Kolk, Department of Surgery, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Mike S L Liem, Department of Surgery, Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands.

Vincent E de Meijer, Department of Surgery, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Gijs A Patijn, Department of Surgery, Isala, Zwolle, The Netherlands.

Daphne Roos, Department of Surgery, Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft, The Netherlands.

Jennifer M Schreinemakers, Department of Surgery, Amphia Hospital, Breda, The Netherlands.

Fennie Wit, Department of Surgery, Tjongerschans, Heerenveen, The Netherlands.

Lois A Daamen, Department of Surgery, Regional Academic Cancer Center Utrecht, St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands; Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Hjalmar C van Santvoort, Department of Surgery, Regional Academic Cancer Center Utrecht, St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

I Quintus Molenaar, Department of Surgery, Regional Academic Cancer Center Utrecht, St Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, University Medical Center Utrecht Cancer Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Casper H J van Eijck, Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Funding

The authors have no funding to declare.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS Open online.

Data availability

Data, analytic methods, and study materials are available upon request.

References

- 1. Jones RP, Psarelli E, Jackson R, Jackson E, Ghaneh P, Halloran CHet al. . Patterns of recurrence after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a secondary analysis of the ESPAC-4 randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial. JAMA Surg 2019;154:1038–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roessel S, Veldhuisen E, Klompmaker S, Janssen QP, Abu Hilal M, Alseidi Aet al. . Evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer after neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX treatment. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1733–1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daamen LA, Groot VP, Besselink MG, Bosscha K, Busch OR, Cirkel GAet al. . Detection, treatment, and survival of pancreatic cancer recurrence in the Netherlands: a nationwide analysis. Ann Surg 2020;275:769–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Groot VP, Rezaee N, Wu W, Cameron JL, Fishman EK, Hruban RHet al. . Patterns, timing, and predictors of recurrence following pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2018;267:936–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown JA, Zenati MS, Simmons RL, Al Abbas AI, Chopra A, Smith Ket al. . Long-term surgical complications after pancreatoduodenectomy: incidence, outcomes, and risk factors. J. Gastrointest Surg 2020;24:1581–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neeman U, Lahat G, Goykham Y, Geva R, Peles-Avraham S, Nachmany Iet al. . Prognostic significance of pancreatic fistula and postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Surgeon 2020;18:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keck T, Wellner UF, Bahra M, Klein F, Sick O, Niedergethmann Met al. . Pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreatojejunostomy for reconstruction after pancreatoduodenectomy: perioperative and long-term results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2016;263:440–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Veillette G, Dominguez I, Ferrone C, Thayer SP, McGrath D, Warshaw ALet al. . Implications and management of pancreatic fistulas following pancreaticoduodenectomy: the Massachusetts General Hospital experience. Arch Surg 2008;143:476–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hank T, Sandini M, Ferrone CR, Rodrigues C, Weniger M, Qadan Met al. . Association between pancreatic fistula and long-term survival in the era of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. JAMA Surg 2019;154:943–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mackay TM, Smits FJ, Roos D, Bonsing BA, Bosscha K, Busch ORet al. . The risk of not receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a nationwide analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. Poor survival rate in patients with postoperative intra-abdominal infectious complications following curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1575–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miki C, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, Araki T, Ohi M, Mohri Yet al. . Perioperative host-tumor inflammatory interactions: a potential trigger for disease recurrence following a curative resection for colorectal cancer. Surg Today 2008;38:579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2005;92:1150–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamphues C, Bova R, Schricke D, Hippler-Benscheidt M, Klauschen F, Stenzinger Aet al. . Postoperative complications deteriorate longterm outcome in pancreatic cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:856–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crippa S, Belfiori G, Bissolati M, Partelli S, Pagnanelli M, Tamburrino Det al. . Recurrence after surgical resection of pancreatic cancer: the importance of postoperative complications beyond tumor biology. HPB (Oxford) 2021;23:1666–1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petermann D, Demartines N, Schäfer M. Severe postoperative complications adversely affect long-term survival after R1 resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. World J Surg 2013;37:1901–1908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi Y, Jin J, Qiu W, Weng Y, Wang J, Zhao Set al. . Short-term outcomes after robot-assisted vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy after the learning curve. JAMA Surg 2020;155:389–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lubrano J, Bachelier P, Paye F, Le Treut YP, Chiche L, Sa-Cunha Aet al. . Severe postoperative complications decrease overall and disease-free interval in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:1078–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahmad J, Grimes N, Farid S, Morris-Stiff G. Inflammatory response related scoring systems in assessing the prognosis of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatobil Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:474–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Abdelghani MB, Wei AC, Raoul Jet al. . FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2395–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Kondo N, Nakagawa Net al. . Early initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival of patients with pancreatic carcinoma after surgical resection. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2013;71:419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CMet al. . Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:1011–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001;357:539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hong S, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Song KB, Lee W, Kwak BJet al. . Usefulness of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with surgically treated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Med 2021;10:5784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abramovitch R, Marikovsky M, Meir G, Neeman M. Stimulation of tumor growth by wound-derived growth factors. Br J Cancer 1999;79:1392–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. VanderWeele TJ. Causal mediation analysis with survival data. Epidemiology 2011;22:582–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hernán MA. Methods of public health research—strengthening causal inference from observational data. New Engl J Med 2021;385:1345–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:867–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walker G. Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) Calculator. MDCalc. https://www.mdcalc.com/charlson-comorbidity-index-cci (accessed 12 October 2021)

- 30. Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham Met al. . The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 2017;161:584–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti Let al. . Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery 2011;149:680–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gyawali B, Eisenhauer E, Tregear M, Booth CM. Progression-free survival: it is time for a new name. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:328–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donders AR, van der Heijden GJ, Stijnen T, Moons KGM. Review: a gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1087–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, Tomlinson JS, Paruch JL, Fleming JB, Talamonti MSet al. . Postoperative complications reduce adjuvant chemotherapy use in resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 2014;260:372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Valle JW, Palmer D, Jackson R, Cox T, Neoptolemos JP, Ghaneh Pet al. . Optimal duration and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: ongoing lessons from the ESPAC-3 study. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:504–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lambert A, Schwarz L, Ducreux M, Conroy T. Neoadjuvant treatment strategies in resectable pancreatic cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hamad A, Brown ZJ, Ejaz AM, Dillhoff M, Cloyd JM. Neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: opportunities for personalizes cancer care. World J Gastroenterol 2021;27:4383–4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, Akkermans-Vogelaar JM, Besselink MG, Bonsing BAet al. . Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the Dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:1763–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang W, Wu L, Lu W, Chen W, Yan W, Qi Cet al. . Lipopolysaccharides increase the risk of colorectal cancer recurrence and metastasis due to the induction of neutrophil extracellular traps after curative resection. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2021;147:2609–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lagarde SM, Boer JD, Kate FJ, Busch OR, Obertop H, van Lanschot JJB. Postoperative complications after esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus are related to timing of death due to recurrence. Ann Surg 2008;247:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008;454:436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zügel N, Siebeck M, Geissler B, Lichtwark-Aschoff M, Gippner-Steppert C, Witte Jet al. . Circulating mediators and organ function in patients undergoing planned relaparotomy vs conventional surgical therapy in severe secondary peritonitis. Arch Surg 2002;137:590–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lof S, van der Heijde N, Abuawwad M, Al-Sarireh B, Boggi U, Butturini Get al. . Robotic versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: multicentre analysis. Br J Surg 2021;108:188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Portuondo JI, Shah SR, Singh H, Massarweh NN. Failure to rescue as a surgical quality indicator: current concepts and future directions for improving surgical outcomes. Anesthesiology 2019;131:426–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boldingh QJ, de Vries FE, Boermeester MA. Abdominal sepsis. Curr Opin Crit Care 2017;23:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smits FJ, Henry AC, Besselink MG, Busch OR, van Eijck CH, Arntz Met al. . Algorithm-based care versus usual care for the early recognition and management of complications after pancreatic resection in the Netherlands: an open-label, nationwide, stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2022;399:1867–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nota CLMA, Hagendoorn J, Borel Rinkes IHM, van der Harst E, Te Riele WW, van Santvoort HCet al. . Robot-assisted Whipple resection; results of the first 100 procedures in the Netherlands. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2019;163:D3682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Augustin T, Burstein MD, Schneider EB, Morris-Stiff G, Wey J, Chalikonda Set al. . Frailty predicts risk of life-threatening complications and mortality after pancreatic resections. Surgery 2016;160:987–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berkel AEM, Bongers BC, Kotte H, Weltevreden P, de Jongh FHC, Eijsvogel MMMet al. . Effects of community-based exercise prehabilitation for patients scheduled for colorectal surgery with high risk for postoperative complications: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2022;275:e299–e306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods 2013;18:137–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pearl J. Interpretation and identification of causal mediation. Psychol Methods 2014;19:459–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data, analytic methods, and study materials are available upon request.

References

- 1. Jones RP, Psarelli E, Jackson R, Jackson E, Ghaneh P, Halloran CHet al. . Patterns of recurrence after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a secondary analysis of the ESPAC-4 randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial. JAMA Surg 2019;154:1038–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roessel S, Veldhuisen E, Klompmaker S, Janssen QP, Abu Hilal M, Alseidi Aet al. . Evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer after neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX treatment. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1733–1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daamen LA, Groot VP, Besselink MG, Bosscha K, Busch OR, Cirkel GAet al. . Detection, treatment, and survival of pancreatic cancer recurrence in the Netherlands: a nationwide analysis. Ann Surg 2020;275:769–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Groot VP, Rezaee N, Wu W, Cameron JL, Fishman EK, Hruban RHet al. . Patterns, timing, and predictors of recurrence following pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2018;267:936–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown JA, Zenati MS, Simmons RL, Al Abbas AI, Chopra A, Smith Ket al. . Long-term surgical complications after pancreatoduodenectomy: incidence, outcomes, and risk factors. J. Gastrointest Surg 2020;24:1581–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neeman U, Lahat G, Goykham Y, Geva R, Peles-Avraham S, Nachmany Iet al. . Prognostic significance of pancreatic fistula and postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Surgeon 2020;18:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keck T, Wellner UF, Bahra M, Klein F, Sick O, Niedergethmann Met al. . Pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreatojejunostomy for reconstruction after pancreatoduodenectomy: perioperative and long-term results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2016;263:440–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Veillette G, Dominguez I, Ferrone C, Thayer SP, McGrath D, Warshaw ALet al. . Implications and management of pancreatic fistulas following pancreaticoduodenectomy: the Massachusetts General Hospital experience. Arch Surg 2008;143:476–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hank T, Sandini M, Ferrone CR, Rodrigues C, Weniger M, Qadan Met al. . Association between pancreatic fistula and long-term survival in the era of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. JAMA Surg 2019;154:943–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mackay TM, Smits FJ, Roos D, Bonsing BA, Bosscha K, Busch ORet al. . The risk of not receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a nationwide analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. Poor survival rate in patients with postoperative intra-abdominal infectious complications following curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1575–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miki C, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, Araki T, Ohi M, Mohri Yet al. . Perioperative host-tumor inflammatory interactions: a potential trigger for disease recurrence following a curative resection for colorectal cancer. Surg Today 2008;38:579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2005;92:1150–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamphues C, Bova R, Schricke D, Hippler-Benscheidt M, Klauschen F, Stenzinger Aet al. . Postoperative complications deteriorate longterm outcome in pancreatic cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:856–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crippa S, Belfiori G, Bissolati M, Partelli S, Pagnanelli M, Tamburrino Det al. . Recurrence after surgical resection of pancreatic cancer: the importance of postoperative complications beyond tumor biology. HPB (Oxford) 2021;23:1666–1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petermann D, Demartines N, Schäfer M. Severe postoperative complications adversely affect long-term survival after R1 resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. World J Surg 2013;37:1901–1908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi Y, Jin J, Qiu W, Weng Y, Wang J, Zhao Set al. . Short-term outcomes after robot-assisted vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy after the learning curve. JAMA Surg 2020;155:389–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lubrano J, Bachelier P, Paye F, Le Treut YP, Chiche L, Sa-Cunha Aet al. . Severe postoperative complications decrease overall and disease-free interval in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:1078–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahmad J, Grimes N, Farid S, Morris-Stiff G. Inflammatory response related scoring systems in assessing the prognosis of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatobil Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:474–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Abdelghani MB, Wei AC, Raoul Jet al. . FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2395–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Kondo N, Nakagawa Net al. . Early initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival of patients with pancreatic carcinoma after surgical resection. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2013;71:419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CMet al. . Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:1011–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001;357:539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hong S, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Song KB, Lee W, Kwak BJet al. . Usefulness of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with surgically treated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Med 2021;10:5784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abramovitch R, Marikovsky M, Meir G, Neeman M. Stimulation of tumor growth by wound-derived growth factors. Br J Cancer 1999;79:1392–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. VanderWeele TJ. Causal mediation analysis with survival data. Epidemiology 2011;22:582–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hernán MA. Methods of public health research—strengthening causal inference from observational data. New Engl J Med 2021;385:1345–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:867–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walker G. Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) Calculator. MDCalc. https://www.mdcalc.com/charlson-comorbidity-index-cci (accessed 12 October 2021)

- 30. Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham Met al. . The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 2017;161:584–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti Let al. . Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery 2011;149:680–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gyawali B, Eisenhauer E, Tregear M, Booth CM. Progression-free survival: it is time for a new name. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:328–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donders AR, van der Heijden GJ, Stijnen T, Moons KGM. Review: a gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1087–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, Tomlinson JS, Paruch JL, Fleming JB, Talamonti MSet al. . Postoperative complications reduce adjuvant chemotherapy use in resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 2014;260:372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Valle JW, Palmer D, Jackson R, Cox T, Neoptolemos JP, Ghaneh Pet al. . Optimal duration and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: ongoing lessons from the ESPAC-3 study. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:504–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lambert A, Schwarz L, Ducreux M, Conroy T. Neoadjuvant treatment strategies in resectable pancreatic cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hamad A, Brown ZJ, Ejaz AM, Dillhoff M, Cloyd JM. Neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: opportunities for personalizes cancer care. World J Gastroenterol 2021;27:4383–4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, Akkermans-Vogelaar JM, Besselink MG, Bonsing BAet al. . Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the Dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:1763–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang W, Wu L, Lu W, Chen W, Yan W, Qi Cet al. . Lipopolysaccharides increase the risk of colorectal cancer recurrence and metastasis due to the induction of neutrophil extracellular traps after curative resection. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2021;147:2609–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lagarde SM, Boer JD, Kate FJ, Busch OR, Obertop H, van Lanschot JJB. Postoperative complications after esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus are related to timing of death due to recurrence. Ann Surg 2008;247:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008;454:436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zügel N, Siebeck M, Geissler B, Lichtwark-Aschoff M, Gippner-Steppert C, Witte Jet al. . Circulating mediators and organ function in patients undergoing planned relaparotomy vs conventional surgical therapy in severe secondary peritonitis. Arch Surg 2002;137:590–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lof S, van der Heijde N, Abuawwad M, Al-Sarireh B, Boggi U, Butturini Get al. . Robotic versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: multicentre analysis. Br J Surg 2021;108:188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Portuondo JI, Shah SR, Singh H, Massarweh NN. Failure to rescue as a surgical quality indicator: current concepts and future directions for improving surgical outcomes. Anesthesiology 2019;131:426–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boldingh QJ, de Vries FE, Boermeester MA. Abdominal sepsis. Curr Opin Crit Care 2017;23:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smits FJ, Henry AC, Besselink MG, Busch OR, van Eijck CH, Arntz Met al. . Algorithm-based care versus usual care for the early recognition and management of complications after pancreatic resection in the Netherlands: an open-label, nationwide, stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2022;399:1867–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nota CLMA, Hagendoorn J, Borel Rinkes IHM, van der Harst E, Te Riele WW, van Santvoort HCet al. . Robot-assisted Whipple resection; results of the first 100 procedures in the Netherlands. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2019;163:D3682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Augustin T, Burstein MD, Schneider EB, Morris-Stiff G, Wey J, Chalikonda Set al. . Frailty predicts risk of life-threatening complications and mortality after pancreatic resections. Surgery 2016;160:987–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berkel AEM, Bongers BC, Kotte H, Weltevreden P, de Jongh FHC, Eijsvogel MMMet al. . Effects of community-based exercise prehabilitation for patients scheduled for colorectal surgery with high risk for postoperative complications: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2022;275:e299–e306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods 2013;18:137–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pearl J. Interpretation and identification of causal mediation. Psychol Methods 2014;19:459–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]