Abstract

Background & aims

Despite effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence is high among people who inject drugs (PWIDs) and non-adherence to therapy remains a major obstacle towards HCV elimination in this subpopulation. To overcome this issue, we have combined ongoing opioid agonist therapy (OAT) with DAAs in a directly-observed therapy (DOT) setting.

Method

From September 2014 until January 2021 PWIDs at high risk of non-adherence to DAA therapy, who were also on OAT, were included into this microelimination project. Individuals received their OAT and DAAs under supervision of healthcare workers as DOT in a pharmacy or low-threshold facility.

Results

In total, 504 HCV RNA-positive PWIDs on OAT (387 men, 76.8%; median age: 38 years [IQR 33–45], HIV: 4.6%; hepatitis B: 1.4%) were included into this study. Two thirds reported ongoing intravenous drug use (IDU) and half of them had no permanent housing. Only 41 (8.1%) were lost to follow-up and two (0.4%) died of reasons unrelated to DAA toxicity. Overall, 90.7% of PWIDs achieved sustained virological response 12 weeks after treatment (SVR12) (95% CI: 88.1–93.2%). By excluding those lost to follow-up and hose who had died of causes unrelated to DAAs, the SVR12 rate was 99.1% (95% CI: 98.3–100.0%; modified intention-to-treat analysis). Four PWIDs (0.9%) experienced treatment failure. Over a median follow-up of 24 weeks (IQR 12–39), 27 reinfections (5.9%) were observed in individuals with the highest IDU rates (81.2%). Importantly, even though some were lost to follow-up, all completed their DAA treatment. By using DOT, adherence to DAAs was excellent with only a total of 86 missed doses (0.3% of 25,224 doses).

Conclusions

In this difficult-to-treat population of PWIDs with high rates of IDU , coupling DAA treatment to OAT in a DOT setting resulted in high SVR12 rates equivalent to conventional treatment settings in non-PWID populations.

Keywords: PWID, HCV, Opioid, Drug use, Hepatitis, Directly observed therapy

1Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is a leading cause of liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver transplantation, and liver-related deaths worldwide.1,2 Medical procedures like operations and injections with inadequate equipment sterilization remain the main route of transmission globally,3,4 but in industrialized countries the majority of newly diagnosed CHC cases occur among people who inject drugs (PWIDs).4, 5, 6, 7, 8

The introduction of direct-acting agents (DAAs) was a paradigm shift for the treatment of hepatitis C(HCV) as new therapeutics showed cure rates in over 95% of cases, defined by sustained virological response 12 weeks after the end of treatment (SVR12) across all genotypes, in advanced liver disease and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 It was shown that successful HCV clearance also resulted in the regression of liver stiffness, a reduction in HCC incidence and of all-cause mortality.15, 16, 17 However, individuals with advanced liver disease remain at risk of developing HCC even after SVR12.18

With the introduction of DAAs in clinical practice, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a global health strategy on HCV elimination as a public health threat by 2030.19 High screening and diagnostic rates, unrestricted access to HCV treatment regardless of disease stage, and harm reduction by providing safe syringes and needles will be pivotal steps to reach this goal.4,19,20 Microelimination strategies targeting subpopulations with high prevalence of HCV (i.e., PWIDs, prisoners, and men-who-have-sex-with-men) are essential to reach this global goal.3,4,21, 22, 23

The prevalence of CHC is high among PWIDs at an estimated 30–50%.3,6,24, 25, 26 The majority of studies evaluating HCV treatment have excluded people with ongoing intravenous drug use (IDU), although this population represents the high-risk group for transmission and reinfection.27 More recent studies evaluating modern DAA regimens have shown high SVR12 rates,independent of IDU.14,27, 28, 29, 30 However, linkage to care in a considerable subgroup of PWIDs who we refer to as “PWIDs with a high risk for non-adherence to DAA-therapy” is difficult because of two main reasons: firstly, we have observed that these individuals rarely attend elective appointments at hospitals, even if specific outpatient clinics are available, and are often admitted in an emergency setting; secondly, challenging personal circumstances, including psychiatric co-morbidities and poor socio-economic status, may hinder adherence to therapy when established at a tertiary care center. As a consequence, regular medication intake may not be guaranteed, a factor greatly reducing DAA effectiveness for viral clearance.

However, many PWIDs in Vienna are on stable opioid agonist therapy (OAT) and visit a pharmacy or low-threshold facility to access it on a daily basis.31,32 Using the strong adherence to OAT to enable successful HCV antiviral treatment, a microelimination project for PWIDs was initiated in this city. We have established a hepatitis out-patient clinic at the biggest low-threshold facility for people with substance use disorder in Vienna, “Suchthilfe Wien” (SHW), where pretreatment evaluation and laboratory tests could be performed. To improve adherence to DAA therapy in PWIDs on OAT, we have dispensed and combined DAAs and OAT which were administered simultaneously at a pharmacy or a low-threshold facility under supervision of a medical professional (i.e., “directly observed therapy”, DOT). In this paper we report on the success of this local microelimination project.

2Methods

2.1. Study population

We have included in this retrospective study 504 PWIDs with CHC between July 2014 and January 2021. For each PWID presenting at the SHW or the Klinik Ottakring, a multidisciplinary team evaluated the likelihood of therapy adherence, taking into account personal circumstances and medical history. Two key factors for assignment to DOT were a low probability of regular medication intake without supervision and of attending appointments. Those with presumed good adherence to therapy received their medication for self-administration once a month (standard setting). Should the team arrive to the conclusion that adherence to DAAs in the standard setting seemed unlikely, these individuals were then enrolled in our DOT program and received DAAs alongside their OAT at their local pharmacy or at the low-threshold facility. Nearly all PWIDs had concomitant psychiatric co-morbidities and low socio-economic status (defined by alcohol use, unemployment, homelessness, lack of a stable relationship, history of previous imprisonment, and ongoing IDU).

2.2. The low-threshold facility: Suchthilfe Wien (SHW)

Low-threshold facilities or treatment programs are harm-reduction interventions for people with substance use disorder, where medical services or needle exchange programs are offered without restrictions regarding substance use. Suchthilfe Wien (SHW) is the largest low-threshold facility in Vienna and offers integrated care for people with substance use disorder. Individuals receive medical treatment from physicians of other specialties and nurses, as well as counseling by social workers, psychologists, and former peers. Medical treatment includes OAT, withdrawal therapy, psychiatric and general medical care as well as access to an HIV and hepatitis out-patient clinic. Temporary housing can be offered at such facility. Through the needle exchange program approximately 10,000 sterile needles and syringes are handed over to PWIDs each day.

2.3. Treatment setting up

Cooperation was built up between a tertiary care centre, Hospital Klinik Ottakring, the low-threshold drug treatment facility, SHW, and a large number of pharmacies in Vienna and surrounding areas. In addition to the hepatitis outpatient clinic at Hospital Klinik Ottakring, a second hepatitis outpatient clinic was established at SHW, where PWIDs were seen by a hepatologist from our team once a week.

The HCV treatment was conducted in all PWIDs according to the concept of DOT with DAAs received alongside OAT at a pharmacy under supervision of a pharmacist or at SHW under supervision of a nurse or a physician on a daily basis (or on a once, twice, or thrice weekly basis in selected cases).

During the pilot phase of this project, the first 109 PWIDs received treatment at SHW. Later on, DAAs and OAT were usually dispensed at the same local pharmacy where individuals had received their OAT previously; only those still in the process of establishing their ideal OAT dosage, who had to be seen by an addiction specialist on a daily basis, received their DOT exclusively at SHW.

2.4. Participant workup

Pretreatment workup included a medical history, physical examination, current medications, a comprehensive metabolic panel, HCV serology, RNA levels and genotype as well as assessment of baseline liver stiffness by transient elastography.

Transient elastography was performed using the Fibroscan® 502 Touch device with the M-probe (Echosens, Paris, France). Stiffness was classified according to the METAVIR scoring system (F0 no fibrosis, F1 mild fibrosis, F2 significant fibrosis, F3 severe fibrosis, and F4 cirrhosis). Cut-off values were defined as <7.1 for F0/F1 (absent/mild fibrosis), ≥7.1 kPa and <9.5 kPa for F2 (significant fibrosis), ≥9.5 kPa and <12.5 kPa for F3 (severe fibrosis) and ≥12.5 kPa for F4 (cirrhosis).33 Only evaluations of 10 measurements with an interquartile range (IQR) below 30% were considered as accurate. If testing by transient elastography was not successful, the stage of liver fibrosis was evaluated by the APRI score.34

The IDU was explored using the PWIDs' history. At least one reported injection within the three months prior to DAA initiation was defined as ongoing IDU. No additional assessment of current IDU other than a self-reported account was performed. All individuals, especially those with ongoing IDU, were regularly informed about harm-reduction measures like needle exchange programs and how to avoid HCV reinfection. Socio-economic circumstances were collected via a binary questionnaire.

2.5. Treatment regimens and “alarm plan”

Treatment regimens were selected according to current guidelines, taking into account the genotype, fibrosis stage, and insurance reimbursement policies. If an individual missed a DOT appointment, an “alarm plan” went into force and the dispensing pharmacy contacted one of our study physicians, who in turn informed the team at SHW. Which would try to reach the individual directly and, if this was unsuccessful, made contact with hospitals and prisons. When the individual was found, a SHW employee would personally bring the OAT and DAAs to the study participant. In case of hospitalization or incarceration, medication was transported to the respective hospital or prison immediately to prevent treatment interruption (see Fig. 1). For each missed appointment and DAA doses, treatment duration was prolonged for the respective number of days.

Fig. 1.

Alarm plan. Patients on OAT received DAAs with DOT at their local pharmacy or a low-threshold facility. Should an individual miss an OAT and DAA dispensing appointment, the pharmacy would inform a physician or the study team at Klinik Ottakring, who in turn would make contact with the low-threshold facility Suchthilfe Wien. If the individuals was not reachable by phone, hospitals and prisons in Vienna were contacted. Once the individual was located, the OAT and DAAs were transported to the individual's location. Abbreviations: OAT = opioid agonist therapy; DOT = directly observed therapy; DAAs = direct -acting antivirals CHC = chronic hepatitis C

2.6. Study end-points

The study primary end-point was sustained virological response (SVR) defined as HCV RNA levels below 15 IU/ml 12 weeks after completion of DAA therapy (SVR12).

Secondary end-points included rates of adherence to therapy, early treatment termination, serious adverse-events, as well as reinfections as assessed by laboratory follow-up every six months after achieving SVR12. In addition, events associated with a high risk of treatment interruption, like unplanned hospitalization, incarceration, or deportation to another country, were recorded.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics are described as median and IQR for continuous variables or absolutes and percentage for categorical variables. The SVR12 rate was evaluated by intention-to-treat (ITT) and modified ITT (mITT) analysis, excluding individuals having not achieved SVR12 for reasons other than virological failure (i.e., those lost to follow-up and those who died prior to SVR12 confirmation for reasons not related to therapy).

In the primary efficacy analyses, two-sided 95% exact confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Microsoft Excel, Version 16.6. and IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25 were used for data management and statistical analyses. Figures were generated using Microsoft Powerpoint, Version 16.6 and Graph Pad Prism 9, Version 9.3.1.

2.8. Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethikkommission der Stadt Wien, EK 16-098-VK), and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and local regulatory requirements. Due to the strictly anonymous analysis of participant data, the Ethics Committee waived the need for specific informed consent. However, to be absolutely sure to comply with data protection regulations, we obtained written informed consent from all participants.

3. Results

3.1. Participants (Table 1, Table 3)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics ofparticipants. (†) One individual had a mixed HCV genotype infection with GT 3a and GT 4 (no subtype specification).

| Variable | Number |

|---|---|

| n (%) | 504 (100.0%) |

| men | 387 (76.8%) |

| women | 117 (23.2%) |

| age, median (IQR) | 38 (33–45) |

| genotype | |

| 1 | 284 (56.4%) |

| 1a | 219 (43.5%) |

| 1b | 56 (11.1%) |

| 2 | 5 (1.0%) |

| 3† | 188 (37.3%) |

| 4† | 14 (2.8%) |

| unknown | 14 (2.8%) |

| HIV coinfection | 23 (4.6%) |

| HBV coinfection | 7 (1.4%) |

| HCV treatment-experienced | 50 (9.9%) |

| fibrosis stage | |

| F0/F1 | 200 (39.7%) |

| F2 | 127 (25.2%) |

| F3 | 71 (14.1%) |

| F4 | 104 (20.6%) |

| N/A | 2 (0.4%) |

| ongoing intravenous drug use | 294 (62.2% of 471) |

| ongoing harmful alcohol use | 65 (17.7% of 367) |

| history of incarceration | 253 (65.0% of 389) |

| no stable relationship | 242 (61.7% of 392) |

| no permanent housing | 177 (45.4% of 390) |

| unemployment | 338 (86.5% of 391) |

Abbreviations: PWID(s) = people who inject drugs; IQR = interquartile range; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HBV = hepatitis B virus; HCV = hepatitis C; N/A = not available.

Table 3.

Comparison ofthe participantbaseline characteristicswhoachievedsustained virological response at week 12 post-treatment (SVR12)or who were subsequently lost to follow-up (LFU) as well as ofthosewho had a reinfection after prior successfuldirect-acting antiviraltreatment. Patrticipants who were reinfected showed the highest rate of intravenous drug use (81.2%), harmful alcohol use (31.8%), coinfections with HIV (18.5%) and HBV (3.7%), and also the poorest socioeconomic status with the highest rates of unemployment (95.6%) and homelessness (69.6%).

| Variable | SVR12 | LFU | REINFECTION |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 457 | 41 | 27 |

| men | 350 (76.6%) | 32 (78.1%) | 20 (74.1%) |

| women | 107 (23.4%) | 9 (22.0%) | 7 (26.0%) |

| age, median (IQR) | 38 (33–45) | 40 (34–47) | 36 (29–37.5) |

| genotype | |||

| 1 | 253 (55.4%) | 28 (68.3%) | 19 (70.4% |

| 1a | 197 (43.1%) | 20 (48.8%) | 15 (55.6%) |

| 1b | 47 (10.3%) | 8 (19.5%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| 2 | 5 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 3 | 176 (38.5%) | 9 (22.0%) | 8 (29.6%) |

| 4† | 12 (2.6%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| unknown | 12 (2.6%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HIV coinfection | 19 (4.2%) | 4 (9.8%) | 5 (18.5%) |

| HBV coinfection | (8 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| HCV treatment-experienced | 42 (9.2%) | 7 (17.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| liver fibrosis stage | |||

| F0/F1 | 181 (39.6%) | 17 (41.5%) | 9 (33.3%) |

| F2 | 118 (25.8%) | 7 (17.1%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| F3 | 63 (13.8%) | 8 (19.5%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| F4 | 94 (20.6%) | 9 (22.0%) | 6 (22.2%) |

| N/A | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| ongoing intravenous drug use | 264 (62.0% 426) | 27 (65.9% of 41) | 18 (81.8% of 22) |

| ongoing harmful alcohol use | 63 (18.2% 346) | 1 (5.9% of 31) | 7 (31.8% of 23) |

| history of incarceration | 226 (63.7% of 355) | 22 (75.9% of 29) | 15 (65.2% of 23) |

| no stable relationship | 215 (60.2% of 357) | 23 (76.7% of 30) | 16 (69.6% of 23) |

| no permanent housing | 157 (44.1% of 356) | 16 (55.2% of 29) | 16 (69.6% of 23) |

| unemployment | 308 (86.3% of 357) | 25 (86.2% of 29) | 22 (95.6% of 23) |

A total of 504 individuals with CHC on OAT started DAAs under DOT from September 2014 till January 2021. They were predominately male (387 pts, 76.8%) with a median age of 38 years (33–45). Liver stiffness measured by vibration-controlled transient elastography found values ≥ 12.5 kPa (indicative of cirrhosis) in 104 individuals (20.6%) at baseline. The predominant genotype (GT) was GT-1 (284, 56.4%), followed by GT-3 (188, 37.3%); in our cohort, 23 individuals (4.6%) were coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and 7 (1.4%) with hepatitis B (HBV). Most were from a low socioeconomic status, with the majority reporting unemployment (86.5%), no permanent housing (45.5%), past incarceration (65.3%), and ongoing IDU (62.7%). Harmful alcohol use was not as common as in the overall population (18.7% of participants; for details see Table 1).

When comparing participants who had achieved SVR12 (n = 457), those who had been lost to follow-up (n = 41), and or who had been reinfected after successful treatment (n = 27), the latter group had the highest rates of unemployment (95.6%),homelessness (69.6%), coinfection with HBV (3.7%) and HIV (18.5%), ongoing IDU (81.8%) and harmful alcohol use (31.8%); for details see Table 3).

3.2. HCV treatment (Table 2)

Table 2.

Regimens of direct-acting antivirals(DAAs)usedfor hepatitis C (HCV) treatment in peoplewho inject drugsunderthe directly observed therapy.

| DAA regimens | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir | 197 (39.1%) |

| Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir | 182 (36.1%) |

| Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir | 63 (12.5%) |

| Elbasvir/Grazoprevir | 21 (4.2%) |

| Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir+Ribavirin | 9 (1.8%) |

| Elbasvir/Grazoprevir+Ribavirin | 8 (1.6%) |

| Sofosbuvir/Daclatasvir | 6 (1.2%) |

| Paritaprevir/Ombitasvir/Dasabuvir+Ribavirin | 6 (1.2%) |

| other | 12 (2.4%) |

Most participants had their first medical contact at the outpatient hepatitis clinic at SHW (n = 322; 64.9%), while 182 of them (36.1%) were first seen at the hepatitis outpatient clinic at Klinik Ottakring and subsequently received DOT at their respective OAT dispensing pharmacy. After an initial workup at SHW, 110 (21.6%) had DOT there and 212 (42.1%) at their local pharmacy. In total, 409 participants (78.4%) on stable OAT received their DAAs at the pharmacy where they had received their OAT in the past. This required a collaboration with more than 200 different pharmacies in Vienna and its metropolitan area.

The most commonly used DAA regimens were sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (197 participants, 39.1%, “SOF/VEL”), glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (182 participants, 36.1%, “G/P”), and sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (63 participants, 12.5%, “SOF/LED”; see Table 2).

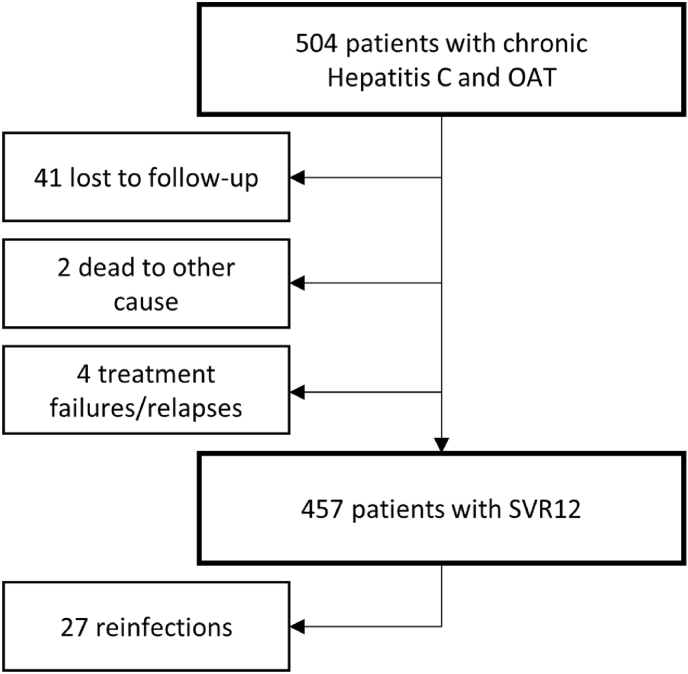

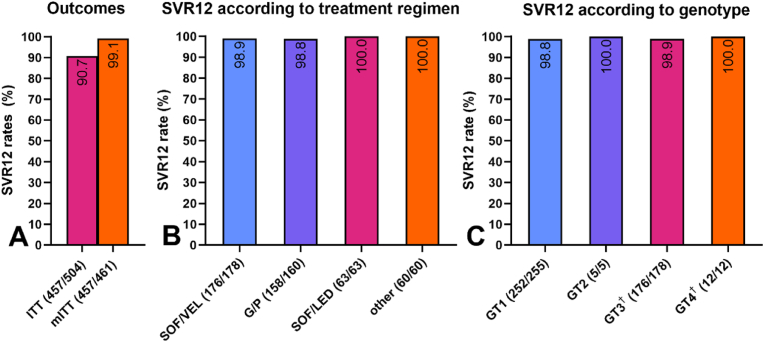

3.3. Virological outcomes (Fig. 2, Fig. 3)

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of participantsand outcomes. Although high-risk behavior like ongoing intravenous drug use was common in this population, SVR12 was achieved in 457 participants. Among these, 27 had a reinfection episode after viral clearance. Although 41 individuals did not attend follow-up visits to confirm SVR12 and were lost to follow-up, all had completed their treatment. Abbreviations: HCV = hepatitis C virus; SVR12 = sustained virological response 12 weeks after treatment.

Fig. 3.

Overall virological outcomes(A), per treatment regimen (B) and perhepatitis C (HCV)genotype (C). A) Virological outcomes according to intention-to-treat (ITT) and modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis. Despite challenging personal circumstances like ongoing intravenous drug use and homelessness, SVR12 was high at 90.7% percent (ITT). Two participants (0.4%) died of reasons unrelated to antiviral treatment and 41 (7.9%) completed DAA therapy, but never had confirmed SVR12 and were thus considered as lost to follow-up (LFU). mITT analysis (excluding LFU and unrelated deaths) showed an SVR12 rate of 99.1%. B) The mITT SVR12 rates as per treatment regimens. SVR12 rates above 98% were achieved for all regimens despite recent or ongoing intravenous drug use. C) mITT SVR12 rates per HCV genotype. High rates of HCV clearance were achieved independently of genotype. For 12 participants no data regarding their genotype was available, but all achieved SVR12. (†) One participant had a mixed GT infection (GT 3a and 4 [not specified]) and also achieved SVR12. Abbreviations: G/P = glecaprevir/pibrentasvir; GT = genotype; HCV = hepatitis C virus; mITT = modified intention-to-treat; SOF/LED = sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; SOF/VEL = sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; SVR12 = sustained virological response 12 weeks after treatment, DAA = direct-acting antiviral.

Two participants (0.4%) died due to reasons not related to DAA therapy before SVR12 was confirmed. Forty-one (8.1%) did not attend their follow-up visits and thus had no SVR12 documented and were labeled as “lost to follow-up” (LFU). However, all the participants who died or were lost to follow-up completed their DAA treatment. In 457 participants SVR12 was documented while not in 4 (0.8%) who were labeled as “treatment failure” (see Fig. 2).

The overall SVR12 rate, including participants lost-to-follow-up , was 90.7% (457/504; 95% CI: 88.1–93.2%). Modified intention-to-treat analysis (mITT) – excluding individuals lost to follow-up and those who had died of treatment-unrelated reasons – showed an SVR12 rate of 99.1% (457/461 individuals; 95% CI: 98.3–100.0%). Successful HCV clearance was independent of the DAA regimen or genotype (see Fig. 3).

3.4. Treatment failures and reinfections

Among the 461 participants analyzed according to mITT, four (0.9%) were classified as treatment failures. Three had completed DAA treatment, but had not attended their 12-week follow-up visit, thus SVR12 could not be confirmed. All three were shown to be viremic again at a later time-point and infected with the same genotype as prior to their antiviral treatment. All still exhibited high-risk behavior with ongoing IDU and needle-sharing. As a “worst-case calculation” they were considered as non-responders, although reinfection seemed likely. One individual completed his DAA DOT, but never showed decreased RNA levels throughout therapy.

During a median follow-up of 24 weeks (IQR 12–39 weeks), 27 participants were reinfected with HCV after having previously achieved SVR12 (27 of 457, 5.9%): 2/27 (7.4%) achieved spontaneous clearance, while for 16/27 (59.3%) DAA retreatment had to be postponed due to unstable personal circumstances. Altogether 9/27 (33.3%) participants received retreatment with DAA: 2/9 (22.2%) were still on reinfection treatment or post-treatment surveillance at the time of data analysis, 1/9 (11.1%) experienced treatment failure upon retreatment and 1/9 (11.1%) died due to endocarditis before SVR12 could be documented. We found that 5/9 (55.6%) individuals who were treated for HCV reinfection had achieved SVR12 and among those, 2 (40.0%) were found to be viremic again at a later visit and enrolled into a third round of DAA treatment: one of them achieved SVR12 again, while the other one currently remains on post-treatment surveillance at the time of the manuscript submission. Importantly, none of the participants who experienced reinfection were lost to follow-up.

3.5. Challenges during DAA therapy

During direct-acting antiviral therapy, 4 (0.8%) participants were imprisoned and 10 (2.0%) hospitalized. The DAAs were transported to the individuals’ whereabouts after their current location had been identified. Two (0.4%) were deported during therapy due to immigration issues but had received medication for the remaining duration of therapy before leaving the country.

3.6. Adherence to therapy

In total, 86 doses of DAAs were missed among 504 participants and later added to the scheduled length of therapy duration. In general, adherence to DOT was excellent with only 86 of 25,244 missed doses (0.3%) all by 34 individuals. While the majority (n = 28/34, 82.4%) missed only three doses or less, half of the missed doses (47/86, 54.7%) were by six individuals (three missed 4 doses, one 7, one 9, and one a total of 19 doses). Each missed dose was added to each individual's duration of DOT. Those who were subsequently lost to follow-up accounted for 14 DAA missed doses. Among individuals who had missed at least one dose, one (2.9%) was a treatment failure, five (13.2%) were lost to follow-up and 28 (82.3% of 34) had achieved SVR12 – including the individual who had missed the most doses.

3.7. Serious adverse events

No serious adverse events related to DAA therapy were reported in the 504 evaluated patients.

4. Discussion

In the industrialized world, IDU is the main route of HCV transmission7 and CHC prevalence among PWIDs in Europe and North America is estimated at 40%.25,31,35 In Austria, HCV antibody prevalence among PWIDs is 87%.31 To eliminate HCV as a public health threat, screening and treating populations at high risk of infection and transmission is necessary.4,23 In this study we have focused on PWIDs with an expected low adherence to therapy, who also did not have stable personal background. Most were characterized by concomitant psychiatric comorbidities, low socio-economic status, and ongoing IDU. Conducting treatment with a span of several weeks, which relies on regular medication intake like DAA therapy for CHC, represents a challenging task, especially in a tertiary care center as from our experience these participantss tend to be reluctant to consult a specialist clinic. However, Austria's opioid substitution program is widely accepted and shows excellent therapy adherence. In Vienna alone there are approximately 8,000 people enrolled in an OAT program,31,32 which we have used to improve adherence to DAA therapy.

The low-threshold facility SHW plays an essential role in the care of people with substance use disorder in Vienna. We have found that the institution's low-threshold for PWIDs to seek medical care there facilitates the first contact for microelimination programs and subsequent linkage to care. The cooperation of a tertiary care center with a low-threshold facility, SHW, allowed us to treat individuals who normally would not schedule an appointment at a medical center and who would not be able to maintain an interruption-free DAA treatment. Our close cooperation and alarm plan allowed to minimize the amount of missed DAA doses in our difficult-to-treat population, with only 0.4% of doses missed. It also limited the number of doses missed per patient as more than 80% of individuals who missed a dose did not miss more than three in total. Almost every participant who missed at least one dose still achieved SVR12 (96.5% not counting those lost to follow-up). While our approach resulted in excellent adherence to therapy in even our most difficult patients, it is indisputable though, that our system is labor- and time-intensive and relies on the determination of the involved individuals.

Despite these efforts, we have still observed treatment failures in four patients, defined by persistent HCV viremia. Among these, three did not attend their 12-week follow-up, technically did not achieve SVR12 and were found to be viremic again at a later date. However, in all of them we have assumed that DAA therapy was completed and that after viral clearance reinfection had occured. One individual never showed decreasing HCV RNA levels during therapy and we suspected that DAAs were not swallowed. All 4 participants were considered as “treatment failure/reinfection”, because proof of SVR12 was lacking. When looking at the 27 participants who were reinfected after SVR12, we found that they were characterized by the highest rates of ongoing IDU, harmful alcohol use, unemployment, homelessness, as well as co-infections with HBV and HIV. These characteristics may help deciding which individuals may benefit from screening for HCV and other blood-borne viruses as well as regular check-ups after SVR12.

Targeting and treating PWIDs with ongoing IDU using DAAs may provide a cost-effective prevention of disease transmission and its complications.36,37 In our population, cure rates were high (above 98% according to mITT) and independent of treatment regimen and genotype, even though about two thirds of our participants reported ongoing IDU. These excellent results despite a difficult-to-treat population are in line with previous studies, where DOT was shown to be an efficient way to increase therapy adherence, resulting in SVR12 rates equal to standard therapy (i.e., without direct observation of medication ingestion) in more accessible PWIDs or non-PWID populations.38, 39, 40, 41, 42 Of note, all individuals enrolled into our study had completed the entire DAA treatment duration, even if they were later lost to follow-up and SVR12 could not be assessed. We see this as confirmation of the advantages of combining OAT with DAAs to improve therapy adherence.

Some limitations of our study need to be addressed. Its scientific impact would have benefited from a control group with unsupervised medication intake, but as low adherence to therapy was the premise for enrolling patients in our DOT program and as treatment failure would have been likely, this approach seemed unethical to us. Furthermore, data is lacking in terms of individuals at high risk of non-adherence to therapy who had refuse OAT and therefore could not be treated in such a setting. For these, we have focused on stabilizing their personal and social environment through the support of social workers, before any medical intervention could be put into place.

Systematic screenings for HCV infection in high-risk populations such as PWIDs remain scarce, yet essential to reach the WHO goal of eliminating HCV as a public health threat by 2030. In our population of PWIDs in Vienna no systematic HCV screening program was available when this study was initiated and individuals were tested for CHC at random during hospitalization or visits at low-threshold facilities. Clearly, such program was urgently needed and initiated during the course of this study.43 As a strategy to facilitate DAA access, the Medical University of Vienna offers a physician-operated HCV hotline, allowing a low-barrier contact between individuals with CHC and medical providers via text messages and phone calls.44

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have observed high rates of HCV clearance in our difficult-to-treat population of PWIDs at risk of non-adherence to DAA therapy,regardless of HCV genotype, drug regimen or ongoing IDU. Combining excellent adherence to OAT and DAA administration for the duration of the HCV treatment resulted in high cure rates (>98%), regardless of regimen, genotype, or ongoing IDU. The use of DOT with the cooperation of a low-threshold facility proved to be an effective strategy to achieve linkage to care, therapy adherence, and cure rates similar to less challenging PWID and non-PWID populations.

Ethics approval and patient consent

- The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethikkommission der Stadt Wien, EK 16-098-VK), and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and local regulatory requirements. Due to the strict anonymous analysis of participant data, the Ethics Committee waived the need for specific informed consent. However, to be absolutely sure to comply with data protection regulations, we have obtained written informed consent from all participants.

Funding statement

- The authors have received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Clinical trial registration

- This study is not a registered clinical trial.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

- No copyrighted material was used for this publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

-

-

Michael Schwarz, Austria (schwarz.medizin@gmail.com): received speaking honoraria from BMS and travel support from BMS, AbbVie, Gilead, and MSD.

-

-

Caroline Schwarz, Austria (schwarz.caroline1990@gmail.com): received travel support from Gilead, Abbvie, and Gebro; speaking honoraria from Abbvie and Gilead; and served as a consultant for Gilead.

-

-

Angelika Schütz, Austria (angelika.schuetz@suchthilfe.at): no conflicts of interest.

-

-

Cornelia Schwanke, Austria (cornelia.schwanke@suchthilfe.at): no conflicts of interest.

-

-

Eva Krabb, Austria (eva.krabb@suchthilfe.at) no conflicts of interest.

-

-

Raphael Schubert, Austria (raphael.schubert@outlook.at): received travel support from Gilead.

-

-

Sophie-Therese Liebich, Austria (sophie-therese.liebich@suchthilfe.at): no conflicts of interest.

-

-

David Bauer (david.bauer@meduniwien.ac.at): received travel support from Gilead and Abbvie and speaker fees from Abbvie.

-

-

Lukas Burghart (lukas.burghart@gesundheitsverbund.at): no conflicts of interest.

-

-

Leonard Brinkmann (leonard-ruben.brinkmann@gesundheitsverbund.at): no conflicts of interest.

-

-

Enisa Gutic, Austria (enisa.gutic@extern.gesundheitsverbund.at): received travel support from Gilead and AbbVie.

-

-

Thomas Reiberger, Austria (thomas.reiberger@meduniwien.ac.at): received grant support from Abbvie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, MSD, Philips Healthcare, Gore; speaking honoraria from Abbvie, Gilead, Gore, Intercept, Roche, MSD; consulting/advisory board fee from Abbvie, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, Intercept, MSD, Siemens; and travel support from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead and Roche.

-

-

Hans Haltmayer, Austria (hans.haltmayer@suchthilfe.at): no conflicts of interest.

-

-

Michael Gschwantler, Austria (michael.gschwantler@gesundheitsverbund.at): received grant support from Abbvie, Gilead and MSD; speaking honoraria from Abbvie, Gilead, Intercept, Janssen, BMS, Roche, Norgine, AstraZeneca, Falk, Shionogi, and MSD; consulting/advisory board fees from Abbvie, Gilead, Intercept, Janssen, BMS, Roche, Alnylam, Norgine, AstraZeneca, Falk, Shionogi and MSD; and travel support from Abbvie and Gilead.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Tsochatzis E.A., Bosch J., Burroughs A.K. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1749–1761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blachier M., Leleu H., Peck-Radosavljevic M., Valla D.C., Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol. 2013;58(3):593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas D.L., Longo D.L. Global elimination of chronic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):2041–2050. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heffernan A., Cooke G.S., Nayagam S., Thursz M., Hallett T.B. Scaling up prevention and treatment towards the elimination of hepatitis C: a global mathematical model. Lancet. 2019;393(10178):1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32277-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villano S.A., Vlahov D., Nelson K.E., Lyles C.M., Cohn S., Thomas D.L. Incidence and risk factors for hepatitis C among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(12):3274–3277. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3274-3277.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page K., Hahn J.A., Evans J., et al. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(8):1216–1226. doi: 10.1086/605947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajarizadeh B., Grebely J., Dore G.J. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(9):553–562. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westbrook R.H., Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 Suppl):S58–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falade-Nwulia O., Suarez-Cuervo C., Nelson D.R., Fried M.W., Segal J.B., Sulkowski M.S. Oral direct-acting agent therapy for hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):637–648. doi: 10.7326/M16-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forns X., Lee S.S., Valdes J., et al. Glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, or 6 infection in adults with compensated cirrhosis (EXPEDITION-1): a single-arm, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(10):1062–1068. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawitz E., Mangia A., Wyles D., et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chromy D., Mandorfer M., Bucsics T., et al. High efficacy of interferon-free therapy for acute hepatitis C in HIV-positive patients. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(4):507–516. doi: 10.1177/2050640619835394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grebely J., Dore G.J., Alami N.N., et al. Safety and efficacy of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotypes 1-6 receiving opioid substitution therapy. Int J Drug Pol. 2019;66:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moser S., Kozbial K., Laferl H., et al. Efficacy of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 3 and compensated liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30(3):291–295. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvaruso V., Cabibbo G., Cacciola I., et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV-associated cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):411-–421 e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan J., Gogela N., Zheng H., et al. Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic HCV infection results in liver stiffness regression over 12 Months post-treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(2):486–492. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4749-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Meer A., Veldt B.J., Feld J.J., et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2584–2593. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.144878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Semmler G., Meyer E.L., Kozbial K., et al. HCC risk stratification after cure of hepatitis C in patients with compensated advanced chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2021;76(4):812–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . 2016. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016-2021 towards Ending Viral Hepatitis. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blach S., Terrault N.A., Tacke F., et al. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: a modelling study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2022;7(5):396–415. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han R., Zhou J., Francois C., Toumi M. Prevalence of hepatitis C infection among the general population and high-risk groups in the EU/EEA: a systematic review update. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):655. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4284-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jachs M., Binter T., Chromy D., et al. Outcomes of an HCV elimination program targeting the Viennese MSM population. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(13-14):635–640. doi: 10.1007/s00508-021-01898-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The European Union HCV Collaborators Hepatitis C virus prevalence and level of intervention required to achieve the WHO targets for elimination in the European Union by 2030: a modelling study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;2(5):325–336. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barror S., Avramovic G., Oprea C., et al. HepCare Europe: a service innovation project. HepCheck: enhancing HCV identification and linkage to care for vulnerable populations through intensified outreach screening. A prospective multisite feasibility study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(Suppl 5):v39–v46. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grebely J., Larney S., Peacock A., et al. Global, regional, and country-level estimates of hepatitis C infection among people who have recently injected drugs. Addiction. 2019;114(1):150–166. doi: 10.1111/add.14393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grebely J., Bruneau J., Bruggmann P., et al. Elimination of hepatitis C virus infection among PWID: the beginning of a new era of interferon-free DAA therapy. Int J Drug Pol. 2017;47:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajarizadeh B., Cunningham E.B., Valerio H., et al. Hepatitis C reinfection after successful antiviral treatment among people who inject drugs: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2020;72(4):643–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dore G.J., Altice F., Litwin A.H., et al. Elbasvir-grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):625–634. doi: 10.7326/M16-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grebely J., Hajarizadeh B., Dore G.J. Direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV infection affecting people who inject drugs. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(11):641–651. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schütz A., Moser S., Schwanke C., et al. Directly observed therapy of chronic hepatitis C with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in people who inject drugs at risk of nonadherence to direct-acting antivirals. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(7):870–873. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horvath I., Anzenberger J., Busch M., Gaiswinkler S., Schmutterer I., Schwarz T. Gesundheit Österreich; Wien: 2020. Bericht zur Drogensituation 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busch M., Anzenberger J., Brotherhood A., et al. Gesundheit Osterreich; Wien: 2021. Bericht zur Drogensituation 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castéra L., Vergniol J., Foucher J., et al. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):343–350. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Z.H., Xin Y.N., Dong Q.J., et al. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):726–736. doi: 10.1002/hep.24105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Academies of Sciences EM . In: A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Strom B.L., Buckley G.J., editors. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin N.K., Vickerman P., Grebely J., et al. Hepatitis C virus treatment for prevention among people who inject drugs: modeling treatment scale-up in the age of direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1598–1609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grebely J., Dore G.J. Treatment of HCV in persons who inject drugs: treatment as prevention. Clinical liver disease. 2017;9(4):77–80. doi: 10.1002/cld.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidbauer C., Schubert R., Schutz A., et al. Directly observed therapy for HCV with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir alongside opioid substitution in people who inject drugs-First real world data from Austria. PLoS One. 2020;15(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidbauer C., Schwarz M., Schutz A., et al. Directly observed therapy at opioid substitution facilities using sofosbuvir/velpatasvir results in excellent SVR12 rates in PWIDs at high risk for non-adherence to DAA therapy. PLoS One. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G., De Clercq E. Current therapy for chronic hepatitis C: the role of direct-acting antivirals. Antivir Res. 2017;142:83–122. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akiyama M.J., Norton B.L., Arnsten J.H., Agyemang L., Heo M., Litwin A.H. Intensive models of hepatitis C care for people who inject drugs receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(9):594–603. doi: 10.7326/M18-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wade A.J., Doyle J.S., Gane E., et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C in primary care, compared to hospital-based care: a randomized, controlled trial in people who inject drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(9):1900–1906. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwarz M., Gremmel S., Wurz M., et al. Let's end hepatitis C in Vienna” - the first HCV elimination program targeting homeless and people without medical insurance in Vienna. Z Gastroenterol. 2020;58:P61. 05. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steininger L., Chromy D., Bauer D., et al. Direct patient-physician communication via a hepatitis C hotline facilitates treatment initiation in patients with poor adherence. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(9-10):452–460. doi: 10.1007/s00508-020-01790-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.