Abstract

Dietary nutrients are associated with the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) both through traditional pathways (inducing hyperlipidemia and chronic inflammation) and through the emergence of a metaorganism-pathogenesis pathway (through the gut microbiota, its metabolites, and host). Several molecules from food play an important role as CVD risk-factor precursors either themselves or through the metabolism of the gut microbiome. Animal-based dietary proteins are the primary source of CVD risk-factor precursors; however, some plants also possess these precursors, though at relatively low levels compared with animal-source food products. Various medications have been developed to treat CVD through the gut-microbiota–circulation axis, and they exhibit potent effects in CVD treatment. Nevertheless, such medicines are still being improved, and there are many research gaps that need to be addressed. Furthermore, some medications have unpleasant or adverse effects. Numerous foods and herbs impart beneficial effects upon health and disease. In the past decade, many studies have focused on treating and preventing CVD by modulating the gut microbiota and their metabolites. This review provides an overview of the available information, summarizes current research related to the gut-microbiota–heart axis, enumerates the foods and herbs that are CVD-risk precursors, and illustrates how metabolites become CVD risk factors through the metabolism of gut microbiota. Moreover, we present perspectives on the application of foods and herbs—including prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and antibiotic-like substances—as CVD prevention agents to modulate gut microbiota by inhibiting gut-derived CVD risk factors.

Taxonomy (classification by EVISE)

Cardiovascular disease, gut microbiota, herbal medicine, preventive medicine, dietary therapy, nutrition supplements.

Keywords: Gut microbiota, Microbial metabolite, Cardiovascular disease, Food, Herbs

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Dietary nutrients can act as CVD risk factor precursors in gut microbiota metabolism.

-

•

Dietary nutrients may be a double-edged sword if not taken properly.

-

•

Foods/herbs can prevent CVD by modulating gut microbiota and their metabolites.

List of abbreviations

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- CntA/B

carnitine monooxygenase (CntA) and associated reductase (CntB)

- cutC/D

choline trimethylamine-lyase (CutC) and activating protein (CutD)

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- Cyp7a1

cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase

- DOCA

deoxycorticosterone acetate

- Egr1

early growth response protein 1

- FGF15

fibroblast growth factor 15

- FMO3

flavin monooxygenase

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- Gcg

proglucagon

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- P9

glucagon-like peptide-1-inducing protein

- PAGln

phenylacetylglutamine

- PAGly

phenylacetylglycine

- Pcsk1

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1

- SCFA

short-chain fatty acid

- TMA

trimethylamine

- TMAO

trimethylamine-N-oxide

- TML

N6,N6,N6-trimethyl-ʟ-lysine

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- TorA

trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- yeaW/X

carnitine oxygenase subunit (yeaW) and a reductase subunit (yeaX)

- γBB

γ-butyrobetaine

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is responsible for nearly one-third of all deaths globally.1,2 An unhealthy diet, alcohol consumption, smoking, and obesity are recognized as traditional health risk factors for CVD.3 In the past decade, numerous studies have revealed the relationship between the novel CVD pathogenesis pathway and gut microbiota and their metabolites, which are largely modifiable by diet.4, 5, 6, 7 Several CVD treatments have been developed to suppress the production of adverse metabolites by the gut-microbiota endocrine organ, including antibiotics, bacterial/host enzyme inhibitors, and fecal microbiota transplantation.8, 9, 10, 11 However, these treatments are still under development, and the taxa and functions of the gut microbiome in human health and disease have not been completely elucidated. Study of the gut microbiome and its function may be forever ongoing. Diet and herbal medicines have a long history of use in the treatment of CVD, although our ancestors did not know that the gut microbiota and their metabolites were risk factors for CVD. Some foods and herbs exhibit antimicrobial effects that inhibit harmful bacteria in the gut.12, 13, 14 In this review, we provide an overview of the available information, briefly summarize current research related to the gut-microbiota–heart axis, present current knowledge regarding foods that may increase CVD risk, and illustrate how metabolites become CVD risk factors via gut-microbiota metabolism. In addition, this review aims to promote the application of foods and herbs for CVD prevention through the inhibition of gut-derived CVD risk factors.

2. Links between gut microbiota, their metabolites, and cardiovascular disease

Intake of an unhealthy diet is a risk factor for the development of CVD through its traditional pathogenesis pathway, as it raises blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels and induces systemic inflammation.15,16 Several gut-microbiome–derived metabolites have been proven as potential CVD inducers in the past decade.17,18 Previously, the gut microbiota was not considered a CVD risk factor. Later, scientific evidence revealed the crucial roles of gut microbiota in several diseases, including obesity, metabolic disorders, and CVD.17,19,20 The phrase “we are what we eat” implies that eating healthy food induces better health conditions. Foods and nutrients are not only essential to human health, but are also vital for gut-microbiota health.21 Hence, feeding the proper nutrients to the gut microbiota is beneficial for the body; by contrast, providing inappropriate nutrients results in adverse effects on body health.22 Therefore, knowledge of feeding appropriate nutrients to the gut microbiome is essential for everyone, as embodied by the phrase, “eat wisely, stay healthy.” The gut microbiome plays an important role at the intersection of diet and human health because gut microbes utilize ingested nutrients for their growth and vital biological processes. In addition to gut bacterial cells, the metabolic outputs of the biological processes of the gut microbiota have crucial consequences for human health.23

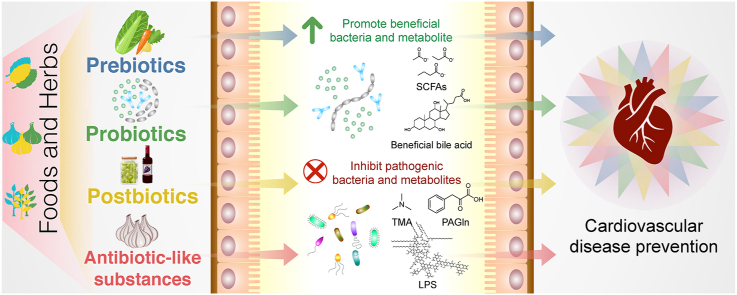

Typically, food is digested and absorbed by the intestine, and nutrients are delivered via the portal vein to the liver for utilization. Like digested essential nutrients, the byproducts of gut-microbiota metabolism—including trimethylamine (TMA), phenylacetic acid, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), flagellin, peptidoglycan, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—are absorbed through the intestinal epithelial cells and delivered to the liver via the portal vein (Fig. 1).24,25 Some metabolites—such as TMA, phenylacetic acid, and LPS—are pro-CVD risk factors,18,26 but others exert anti-inflammatory effects on human health (SCFAs and particularly bile acid).27,28 Both gut microbiota and their metabolites can translocate to the liver and other organs through the portal vein. Intestinal barrier strength or intestinal permeability is also essential for reducing the content of harmful metabolites; a more strengthened intestinal barrier can lessen the translocation of bacterial products to the liver.29, 30, 31 An unhealthy diet—such as a high-fat, high-sugar diet—can deteriorate the intestinal barrier strength.32

Fig. 1.

Link between gut microbiota and their metabolites and cardiovascular disease (CVD). ① Food and diet can cause CVD risk both through traditional pathways (increasing systemic lipidomics and inflammation) and through the metaorganism pathogenesis pathway (gut microbiota and host). ② Most food is digested and absorbed by the intestine, and nutrients are delivered via the portal vein to the liver for utilization. ③ Undigested food and nutrients can be utilized by gut microbiota for their growth; the byproducts after such utilization are known as gut-microbiota metabolites. ④ The metabolites of the gut microbiota, including trimethylamine (TMA), phenylacetic acid, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), flagellin, peptidoglycan, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), are generated by gut microbiota. Some metabolites are pro-CVD risk factors, but others exert anti-inflammatory effects on human health. Both gut microbiota and their metabolites can translocate to the liver and other organs through the portal vein. ⑤ The liver is the first organ in the body's system to detoxify harmful gut-microbiota metabolites, and hepatic enzymes convert several compounds into CVD risk factors. ⑥ Gut-microbiota–derived metabolites increase CVD risk and systemic inflammation.

The liver is known for its function in metabolically neutralizing toxins and harmful metabolites from the gut microbiota.33, 34, 35 Several food and gut-microbiota metabolites are transformed into CVD risk factors by hepatic enzymes (e.g., TMA to TMA N-oxide (TMAO); phenylacetic acid to phenylacetylglutamine (PAGln)).36, 37, 38 The hepatic enzyme–converted bacterial metabolites are released into the blood circulation system, increasing CVD risk and inducing systemic inflammation.39

3. Dietary nutrients as cardiovascular disease risk factor precursors in gut-microbiota metabolism

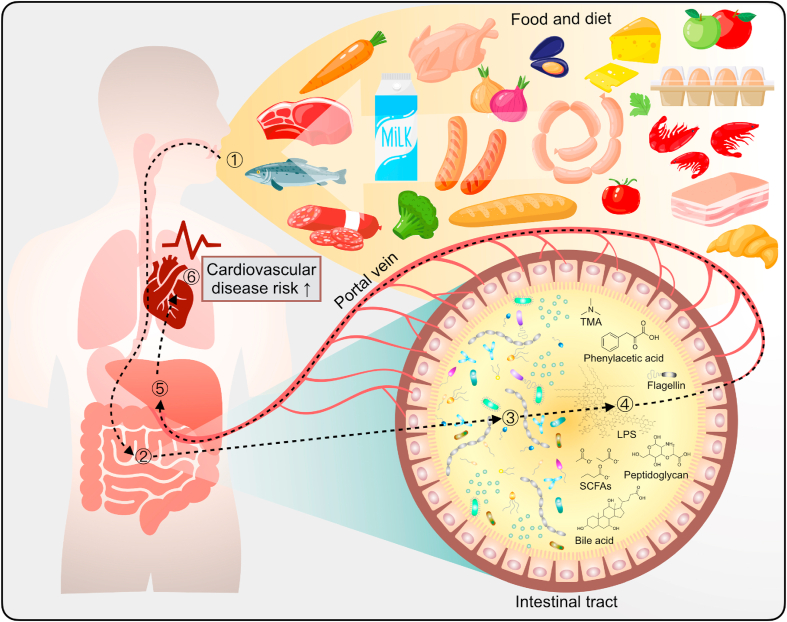

Various gut microorganisms produce different CVD precursors or CVD risk factor components from dietary precursors. Several microbial pathways and their corresponding genes, with or without the involvement of the host enzyme, are associated with the formation of CVD risk factors.4, 5, 6 Numerous foods, mainly from animal-protein sources, have been proven to contain pro-CVD precursor biomolecules such as molecules containing a TMA moiety and phenylalanine. However, these amino acids can also be found in plant-based products and fungi, and some CVD precursors are only derived from plants and mushrooms.40 These food biomolecules are subsequently metabolized by metaorganisms41 (host and gut microbiota) to produce CVD risk factors.8 Intake of TMA moiety–containing food may allow TMA to be absorbed into the body. In addition, some studies suggest that TMA is a toxin and a marker of gut-derived CVD risk factors similar to TMAO.42 CVD risk factors and their precursors include TMA, TMAO, ʟ-carnitine, γ-butyrobetaine (γBB), trimethyllysine, δ-valerobetaine, choline, betaine, ergothioneine, and phenylalanine (Fig. 2). Dietary nutrients that are CVD risk factor precursors in gut-microbiota metabolism are described below.

Fig. 2.

Diet–gut-microbiota–host interaction for cardiovascular disease (CVD) development. Various foods contain pro-CVD precursor biomolecules that are principally derived from animal protein. CVD risk factors and their precursors incorporate trimethylamine (TMA), TMA N-oxide (TMAO), ʟ-carnitine, γ-butyrobetaine (γBB), trimethyllysine (TML), δ-valerobetaine, choline, betaine, sinapine, ergothioneine, and phenylalanine. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), peptidoglycan, and flagellin also cause systemic inflammation, followed by an increase in CVD risk. The imbalance of the bile acid ratio also causes cardiometabolic disease. The gut microbiome metabolizes non-digestible carbohydrates to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, butyrate, and propionate, and thereby exerts anti-inflammatory effects and protects against CVD.

TMA is detected in marine products; it provides ammonia-like and fishy off-flavors, and hence acts as a fish spoilage indicator.43, 44, 45 TMAO is found in saltwater fish and seafood in various ranges.45 The function of TMAO in deep-sea fishes is to prevent the protein-destabilizing effects of osmotic and hydrostatic pressures.46 TMAO is reduced to TMA by the TMAO reductase in bacteria such as Vibrio and Shewanella spp.47 TMA can also be metabolized to TMAO by gut microbes, using TMA monooxygenase. The TMA moiety includes phosphatidylcholine, choline, betaine, carnitine, N6,N6,N6-trimethyl-ʟ-lysine (TML), sinapine, and ergothioneine.40 Specific gut bacteria can metabolize food-derived TMA moieties to produce TMA, which is subsequently oxidized to TMAO by hepatic flavin monooxygenase (FMO3).48, 49, 50 Epidemiological studies have revealed that high concentrations of blood TMAO are strongly associated with the development of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.51,52 TMAO enhances atherosclerotic and thrombotic activities, reduces reverse cholesterol transport, induces platelet aggregation, and eventually leads to foam-cell formation.8,48,50,53 In addition, TMAO has been reported to enhance platelet aggregation and induce thrombosis in both in vitro and human studies.54, 55, 56

ʟ-Carnitine is a water-soluble compound that humans can absorb from food or produce by endogenous synthesis from trimethyllysine. Carnitine is essential for cell function as a component of several mitochondrial enzymes.54 Carnitine concentration can be as high as 6 g/kg of animal meat. It can also be detected in dairy products and plant-derived foods, in which its concentration is moderately lower than that in animal muscle.57 A Rieske-type microbial CntA/B enzyme, carnitine monooxygenase, has been reported to convert carnitine to TMA.53 The CntA/B enzyme is oxygen-dependent, and its activity may be restricted in the anaerobic conditions of the gut.

γBB is produced as an intermediary metabolite by gut bacteria from ʟ-carnitine, and its conversion rate is 1000-fold higher than that of TMA formation.58 γBB can be derived from the reaction of carnitine and carnitine CoA-transferase. A recent study suggested that ʟ-carnitine is transformed into TMA via two sequential gut-microbiota–dependent transformations: (1) generation of the atherogenic intermediate γBB, followed by (2) conversion into TMA by low-abundance microbiota in omnivores, and to a considerably lower amount in vegans or vegetarians. Emergencia timonensis is capable of anaerobically transforming γBB to TMA and may be a critical bacterium for TMA production.37 However, the mechanism by which gut microorganisms and the relevant enzymes convert carnitine to TMA has only been partially elucidated. TML is an amino acid that was identified using a metabolomics approach and has been reported as a TMAO-producing nutrient precursor. TML is abundant in both plant- and animal-derived foods.59 TML can be metabolized by multiple enzymes to produce the intermediate γBB, which is subsequently transformed into TMA by TMA lyase.60,61 δ-Valerobetaine is another precursor of TMA, similar to γ-BB, and is found in ruminant meat and milk.62

Choline is a necessary dietary nutrient for humans because it is involved in a wide range of critical physiological functions, including synthesizing phospholipids, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, and the methyl-group donor betaine. Dietary choline is present in both water-soluble (e.g., free choline, phosphocholine, and glycerophosphocholine) and lipid-soluble (e.g., phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin) forms.63 Choline content is higher in animal-source foods than in vegetables. Foods containing a high choline content include liver, eggs, beef, fish, pork, chicken, milk, and dairy products.63,64 Choline can be oxidized to betaine, which functions as an osmoregulator, and is a substrate in the betaine–homocysteine methyltransferase reaction.65 CutC/D, which encodes choline TMA-lyase, is involved in the catabolic reactions that convert dietary choline into TMA.66,67 A variety of intestinal microorganisms can convert choline to TMA, including Anaerococcus hydrogenalis, Clostridium asparagiforme, Clostridium hathewayi, Clostridium sporogenes, Edwardsiella tarda, Escherichia fergusonii, Proteus penneri, and Providencia rettgeri.68

Betaine is detected in microorganisms, plants, and animals, and is a part of many foods, including cereal grains, grain-based products, wheat, shellfish, spinach, and sugar beets.69,70 Selenocysteine-containing betaine reductase from particular bacteria can produce TMA from glycine betaine.71,72 The microbial enzyme yeaW/X exhibits TMA-lyase activity for multiple compounds containing TMA moieties, including betaine, γBB, carnitine, and choline.58

Ergothioneine is produced by fungi, mycobacteria, and some cyanobacteria. Mushrooms are a rich source of ergothioneine. Ergothioneine is also found throughout the human body, including red blood cells, liver, kidneys, and semen.73,74 The enzyme ergothionase from some bacteria can degrade ergothioneine to TMA.75,76

Phenylalanine is an amino acid derived from meat, meat products, grain products, milk, dairy products, eggs, and vegetables.77,78 Phenylalanine can be metabolized by gut microbes possessing the porA gene, which is responsible for converting phenylalanine to PAGln and phenylacetylglycine (PAGly). Both PAGln in humans and PAGly in rodents were found to be associated with CVD and incite major adverse cardiovascular events by enhancing platelet-activation–related phenotypes and thrombosis potential. PAGln stimulates platelet responsiveness and thrombosis through G-protein–coupled receptors, including α2A, α2B, and β2-adrenergic receptors.38

Overemphasis of the fact that dietary proteins generate CVD risk factors might obscure their importance for the body. Although the dietary substances mentioned above are CVD-risk precursors, some compounds are beneficial—or even crucial—for human health. Dietary nutrients may be a double-edged sword, if not consumed appropriately. Precision medicine is another issue to consider. Feeding of gut microbiota should consider how they utilize dietary substrates. Different individuals exhibit diverse gut microbiome compositions and functions; for example, gut microbes and vegan hosts exhibit less ability to form plasma and urine TMAO from ʟ-carnitine than omnivorous individuals.79,80 Vegetarians do not consume animal protein. Hence, some essential amino acids are crucial for their health. By contrast, for people who consume a high amount of animal protein, these amino acids may be excessive for health; therefore, gut microbiota may utilize these excessive amino acids to generate pro-CVD risk-factor substances.

LPS and peptidoglycan from the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria, and flagellin from bacterial flagella, can induce systemic inflammation and consequently increase CVD risk (Fig. 2).81 Moreover, an imbalance in the bile-acid ratio also generates a cardiometabolic risk.82, 83, 84 Not all bacterial metabolites cause CVD risk. Dietary fiber can reduce CVD risk because non-digestible carbohydrates are metabolized to SCFAs such as acetate, butyrate, and propionate, which exhibit anti-inflammatory and protective effects against CVD.85

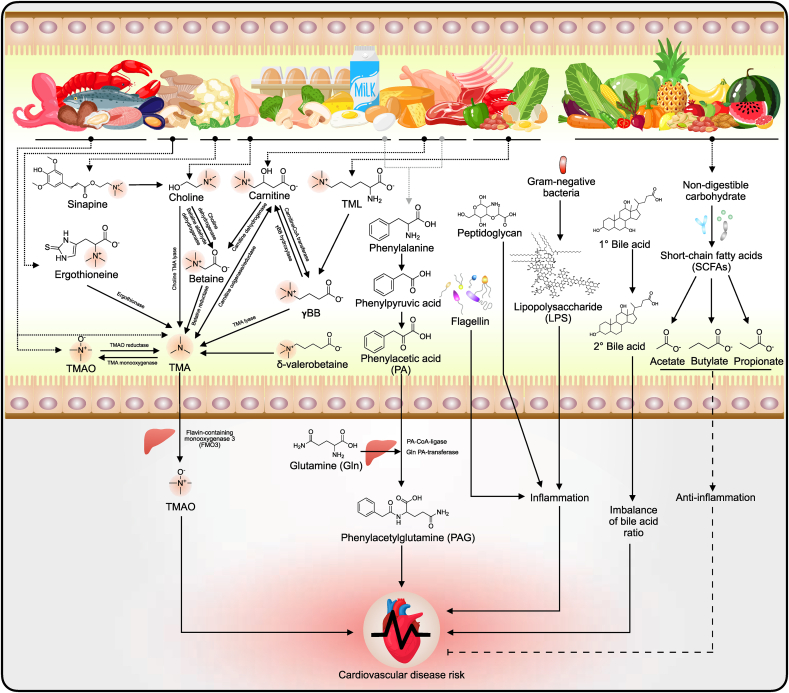

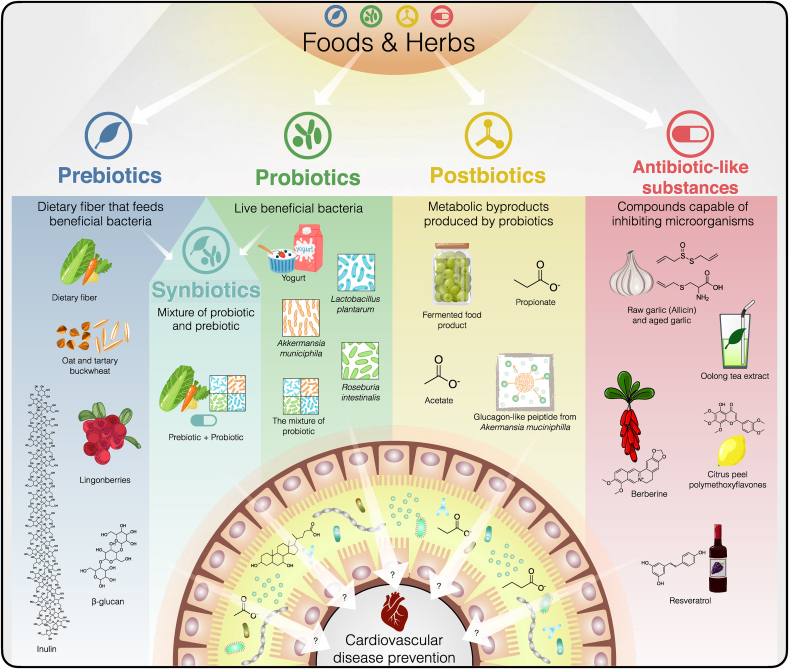

4. Application of foods/herbs as prebiotics, probiotics, postbiotics, and antibiotic-like substances can prevent CVD through modulation of gut microbiota and their metabolites

Studies on how food and herb components interact with gut microbiota have allowed the expansion of knowledge about modifying dietary intake behaviors to promote health.23,86 Current strategies to alleviate CVD through manipulation of the gut microbial endocrine organ include the use of dietary interventions, application of host enzymes involved in the generation of metaorganismal metabolites, fecal microbial transplantation, intake of pre- and probiotics, and the use of bacterial enzyme inhibitors and antimicrobials.8, 9, 10, 11 However, these strategies are still being improved and may pose safety concerns; hence, they require validation using human studies. In this review, we focus on the application of foods and herbs that target the gut microbiota and their metabolites to decrease CVD risk. We collated recent studies related to foods and herbs that protect against CVD, as well as their association with the gut microbiota. Our perspectives on the use of foods and herbs to modulate the gut–host–CVD axis encompass prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and antibiotic-like substances (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Application of foods and herbs as prebiotics, probiotics, postbiotics, and antibiotic-like substances for preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD) through the modulation of gut microbiota and their metabolites, as well as the application perspective. These strategies can help understand how to use foods and herbs as preventive medicines and self-health management kits to reduce CVD risk.

4.1. Prebiotics

Dietary fiber impacts gut microbial ecology, host physiology, and health.87 Dietary fiber is a non-digestible form of carbohydrate from vegetables, fruits, legumes, etc., which human enzymes are unable to digest. Dietary fiber intake reduces CVD risk.85 Dietary fibers comprise both water-soluble and water-insoluble types.88 Water-soluble fibers comprise pectin, gums, mucilage, fructans, and some resistant starches. Water-insoluble fibers include lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose.89 Indigestible fiber can be fermented by gut microbiota to produce SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, butyrate, and total SCFAs, which have been reported to reduce blood cholesterol levels.12,90 Some studies suggest that a lack of prebiotic dietary fiber results in hypertension due to deficient SCFA production by gut microbiota and implicate G-protein–coupled receptor signaling.91 Based on the current literature, the roles of prebiotics in preventing cardiovascular disease through the gut microbiota include controlling the balance of the intestinal microbiome, strengthening the gut barrier, and enhancing the increase of beneficial bacteria and SCFA-producing bacteria by reducing the translocation to the liver of harmful gut-microbiota metabolites.92 Several prebiotics prevent CVD; oats and tartary buckwheat, for example, reduce plasma lipid levels in hypercholesterolemic hamsters by inhibiting cholesterol absorption, promoting fecal lipid and bile acid excretion, and inducing the gut microbiome to produce SCFAs (Table 1).90 Consumption of high-molecular-weight β-glucan in breakfast for five weeks has been shown to shift the gut-microbiota composition in humans.93 This shift in gut microbiota was positively associated with an improvement in the CVD risk-factor profile, including body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, and triglyceride levels. Intake of a β-glucan–rich mixture from mushrooms alters the gut-microbiota composition.94,95 Supplementation of lingonberries containing high amounts of dietary-fiber polysaccharides resulted in a decline in triglyceridemia and atherosclerosis, an improvement in gut-microbiota composition and SCFA profile, and an increase in hepatic bile acid gene expression in apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-deficient mice fed a high-fat diet.96 A combination of a high-fiber diet and supplementation with SCFA and acetate prevented the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice by decreasing systolic and diastolic blood pressures, cardiac fibrosis, and left ventricular hypertrophy, as well as by reducing gut dysbiosis.97 These studies emphasize that prebiotics are essential for CVD prevention. However, some studies showed that prebiotics such as inulin only modulated gut microbiota and increased the level of SCFAs but did not ameliorate atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic ApoE∗3-Leiden.CETP mice.98

Table 1.

Foods and herbs as prebiotics for CVD prevention through modulation of gut microbiota and their metabolites.

| Prebiotic | Study model | Important finding | Effect on gut microbiota and their metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oat and tartary buckwheat90 | Four-week-old male gold hamsters were fed a high-fat diet with buckwheat-based food for 30 days. Buckwheat-based food was composed of oats (65 g/100 g) and tartary buckwheat (25 g/100 g). | Plasma total cholesterol ↓, LDL cholesterol ↓, liver total cholesterol ↓, cholesterol ester ↓, triglycerides ↓, and fecal weight ↑ in group fed buckwheat-based food. | Bile acids ↑, acetate ↑, propionate ↑, butyrate ↑ and total SCFAs ↑. Buckwheat-based food shaped the structure of the gut microbiota. Erysipelotrichaceae ↓, Ruminococcaceae ↓, Lachnospiraceae ↓, and Eubacteriaceae ↑. |

| High-molecular-weight β-glucan93 | In a randomized, controlled crossover study design, individuals took—for 5 weeks—a breakfast containing either 3 g of high-molecular-weight β-glucan, 3 g of low-molecular-weight β-glucan, 5 g of low-molecular-weight barley β-glucan, or wheat and rice. | Intake of high-molecular-weight β-glucan shaped gut-microbiota composition, changed microbiota profile, and was associated with reduced CVD risk markers. | At the phylum level, high-molecular-weight β-glucan: Bacteroidetes ↑, Firmicutes ↓. At the genus level: Bacteroides ↑, Prevotella ↑, Dorea ↓. Diets containing low-molecular-weight β-glucan and low-molecular-weight barley β-glucan did not modify the gut-microbiota composition. Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Dorea composition was associated with alterations of CVD risk factors, including body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, and triglyceride levels. |

| Lingonberries96 | Male ApoE knockout mice were fed a high-fat diet with 44% lingonberries for 8 weeks. | Intake of lingonberries reduced triglyceridemia and atherosclerosis. Triglycerides ↓, atherosclerotic plaques ↓, and hepatic bile-acid gene (Cyp7a1) ↑. | Bacteroides ↑, Parabacteroides ↑, and Clostridium ↑. Cecal levels of total SCFAs ↓ and proportion of propionic acid ↑. |

| High-fiber diet supplemented with SCFAs97 | Deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)–salt C57Bl/6 mouse model. Mice received a high-fiber diet (72.7% fiber) supplementation 3 weeks before DOCA surgery. After 3 weeks of diet intervention, mice underwent a left uninephrectomy and were implanted with a 21-day slow-release DOCA pellet. | High-fiber diet supplementation: systolic ↓ and diastolic blood pressures ↓, cardiac fibrosis ↓, and left ventricular hypertrophy ↓. Cardiac and renal Egr1 ↓, a master cardiovascular regulator associated with cardiac hypertrophy, cardiorenal fibrosis, and inflammation. | Gut microbiota were modified, acetate-producing bacteria ↑, ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ↓, and Bacteroides acidifaciens ↑. |

| Inulin98 | Atherosclerosis ApoE∗3-Leiden.CETP (E3L.CETP) mouse model. Female E3L.CETP mice were fed a western diet containing 0.1% or 0.5% cholesterol with or without 10% inulin for 11 weeks. | Inulin did not reduce hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerosis development in E3L.CETP mice but induced hepatic inflammation when coupled with a high portion of dietary cholesterol. | Inulin exhibited prebiotic activity by increasing cecal SCFA levels (propionate ↑ and butyrate ↑). Inulin with 0.5% dietary cholesterol promoted the growth of bacteria from specific genera, including Coprococcus and Allobaculum, and inhibited the growth of bacteria from the genera Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Prevotella, Mucispirillum, Clostridium, and Coprobacillus. |

4.2. Probiotics

Probiotics are live bacteria that are beneficial to health. They have been reported to alleviate CVD through antioxidative, anti–platelet-aggregating, anti-inflammatory, anti-lipidemic, and TMAO-reducing–related mechanisms.92 The health benefits and safety of traditional probiotics including Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium spp. have been proven.99 These traditional probiotics can be found in fermented food products such as yogurt and fermented milk. Several probiotics have been reported to prevent CVD. Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04 has been reported to exert its probiotic activity by lowering blood TMAO levels and modulating the gut microbiota composition in mice supplemented with choline. In addition, L. plantarum ZDY04 suppressed the development of TMAO-induced atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice supplemented with choline (Table 2).100 A mixture of probiotics (Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus) reduced atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation in high-fat-diet–induced ApoE knockout mice.101 No studies currently present in the literature report probiotic bacteria contributing to TMA or TMAO production. Recently, two next-generation CVD-reversion probiotics—Roseburia intestinalis and Akkermansia muciniphila—were discovered. Roseburia intestinalis is a butyrate-producing bacterium that is inversely associated with atherosclerotic lesion development. It cooperated with dietary plant polysaccharides to lower systemic inflammation and ameliorate atherosclerosis in germ-free ApoE-deficient mice colonized with synthetic microbial communities. In addition, intestinal treatment with butyrate ameliorated endotoxemia and development of atherosclerosis.102 Akkermansia muciniphila, a mucin-degrading bacterium, diminished atherosclerotic lesions by ameliorating metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation through the recovery of the gut barrier in ApoE−/− mice treated by daily oral gavage for eight weeks.103 Owing to the potential revealed in such studies, the use of next-generation probiotics for developing fermented food products and functional foods may be another route to expand their usage in daily life. In addition, it is important to retain intestinal probiotic colonization because it may wash out from the intestine. Although several probiotics have been discovered, it is necessary to study them at the clinical level, and their safety needs to be considered for application. Although probiotics can reduce CVD risk, the pH differences between the gastric system and small intestine should inform development of probiotic delivery routes via consumption, to maintain probiotic cell survival during passage to the intestine. Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics that act as nutrients for the synergistic growth of probiotics.104,105 The benefits of synbiotics have been verified against several diseases, including irritable bowel syndrome.106 The potential benefit to human health of co-encapsulated synbiotics and immobilized probiotics via the gut-microbiota modulation pathway has been confirmed.107 Currently, there are few studies into the beneficial effects of synbiotics on CVD. However, the use of prebiotics and probiotics for CVD prevention provides strong evidence that synbiotics can protect against CVD.

Table 2.

Foods and herbs as probiotics for CVD prevention through modulation of gut microbiota and their metabolites.

| Probiotic | Study model | Important finding | Effect on gut microbiota and their metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04100 | Female BALB/c mice received 1 × 109 CFU of L. plantarum ZDY04 daily for 4 weeks by oral gavage. Male C57BL/6J ApoE−/− mice were fed a chow diet supplemented with 1.3% choline and L. plantarum ZDY04 daily for 16 weeks. | L. plantarum ZDY04 supplementation in ApoE−/− mice: atherosclerotic lesion formation ↓ and no effect on FMO3 activity. |

L. plantarum ZDY04 supplements in BALB/c mice: serum TMAO ↓ and cecal TMA ↓; modulated relative abundance of the families Lachnospiraceae ↑, Erysipelotrichaceae ↑, Bacteroidaceae ↑, Aerococcaceae ↓, and the genus Mucispirillum ↓. L. plantarum ZDY04 supplementation in ApoE−/− mice: TMAO ↓. |

| Mixture of probiotics (8 strains of probiotics including Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Streptococcus thermophilus)101 | Female 6-week-old C57BL/6 ApoE−/− mice were fed a high-fat diet with a mixture of probiotics (2.78 × 1011 CFU/day) for 12 weeks. | Aortic lesions ↓, vascular inflammation ↓, and satiety hormone peptide YY ↑, without change in weight and food intake. | The probiotic mixture modified the dominant bacterial composition in both the ileum and colon. |

| Roseburia intestinalis102 | Germ-free ApoE−/− mice were colonized with synthetic microbial communities and R. intestinalis, and then fed a high-fat diet (33 kcal% fat from cocoa butter) supplemented with 1% cholesterol or high content of plant polysaccharides. | R. intestinalis influenced gene expression in the intestine, shifted metabolism away from glycolysis and toward fatty acid utilization, decreased systemic inflammation, and reduced atherosclerosis. | Cecal levels of SCFAs ↑ and LPS ↓ in mice fed high content of plant polysaccharides. |

| Akkermansia muciniphila103 | Eight-week-old male ApoE−/− mice were fed a Western diet and treats with A. muciniphila by daily oral gavage for 8 weeks. | A. muciniphila supplement group: atherosclerotic lesions ↓, inflammation in the circulation ↓, local atherosclerotic lesions ↓, endotoxemia ↓, and tight junction proteins ↓. | Serum LPS ↓ |

4.3. Postbiotics

Postbiotics are metabolic products produced by microorganisms that have beneficial effects on health. Typically, postbiotics contain only bacterial metabolites and their substrates, and there are no live microorganisms. Postbiotics include cell-free supernatants, exopolysaccharides, enzymes, cell-wall fragments, SCFAs, bacterial lysates, and metabolites produced by microorganisms.108 Because postbiotics comprise the spectrum of compounds produced by microorganisms, they act on health via the gut-microbiota–CVD axis broadly by modulating gut-microbiota composition, boosting innate immunity, decreasing pathogen-induced inflammation, and enhancing the survival of intestinal epithelial cells, etc.104 Gut microbes can metabolize microbiota-accessible carbohydrates to produce SCFAs that may interact with the host in multiple ways and play an essential role in health.23 SCFAs have been widely studied for CVD treatment. An acute microbial SCFA bolus decreases blood pressure via the endothelial G-protein–coupled receptor 41.109 Propionate treatment attenuated cardiac ventricular arrhythmias in angiotensin II–infused wild-type NMRI mice; moreover, it diminished atherosclerotic aortic lesions in ApoE knockout mice (Table 3). Propionate also acted as an immunomodulator in this study. The cardioprotective effects of propionate are principally dependent on regulatory T cells.110 Lipoteichoic acid from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BPL1 has been found to have a fat-reducing function through the insulin-like growth factor–1 pathway. Several postbiotics have been proven to function against obesity and metabolic diseases; for example, the membrane protein and pasteurized cells of A. muciniphila improved metabolism and prevented diabetes in a rodent model.111 Moreover, A. muciniphila can secrete a peptide called glucagon-like peptide-1–inducing protein that ameliorates metabolic diseases and enhances glucose homeostasis.112 Since studies on postbiotics have primarily focused on obesity and metabolic disorders, the use of postbiotics for CVD–gut-microbiota treatment requires further research. Postbiotics present an advantage over probiotics because they are bacterial byproducts that are simple to control compared with live cells, for which colonization efficiency—and safety in case of overgrowth in the intestine—need to be considered. Several fermented foods include SCFAs, functional proteins, and beneficial compounds that may modulate the gut microbiota and their metabolites. Such fermented foods represent a new opportunity for the development of functional foods to prevent CVD through the modulation of gut microbiota and their metabolites.

Table 3.

Foods and herbs as postbiotics for CVD prevention through modulation of gut microbiota and their metabolites.

| Postbiotic | Study model | Important finding | Effect on gut microbiota and their metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propionate110 | Angiotensin II infusion-induced hypertension model of wild-type NMRI or ApoE knockout mice supplemented with propionate (200 mmol/L) in the drinking water for 28 days. | Propionate alleviated cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, vascular dysfunction, and hypertension in both models. Cardiac ventricular arrhythmias ↓, aortic atherosclerotic lesion area ↓, and systemic inflammation ↓. | – |

| Acetate111 | Deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)–salt C57BL/6 mouse model. Mice received 200 mmol/L magnesium acetate supplementation 3 weeks before sham or DOCA surgery. After 3 weeks of SCFA intervention, mice underwent a left uninephrectomy and were implanted with a 21-day slow-release DOCA pellet. | Acetate supplementation: systolic ↓ and diastolic blood pressures ↓, cardiac fibrosis ↓, left ventricular hypertrophy ↓, and renal fibrosis ↓. Cardiac and renal Egr1 ↓, a master cardiovascular regulator associated with cardiac hypertrophy, cardiorenal fibrosis, and inflammation. | Acetate: acetate-producing bacteria ↑, ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ↓, and Bacteroides acidifaciens ↑. |

| Glucagon-like peptide from Akkermansia muciniphila112 | C57BL/6J mice fed a high-fat diet and orally administered a purified glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)-inducing protein (P9) daily for 8 weeks. | P9 from A. muciniphila prevented obesity and regulated glucose homeostasis by boosting thermogenesis. Weight gain ↓, food intake ↓, adipose tissue volume ↓, glucose intolerance ↓, ileal Gcg ↓ and Pcsk1 ↑, thermogenesis ↑, expression of BAT-specific genes ↑, and body temperature ↑. | – |

In the current studies, there is a lack of molecular mechanistic insight into how prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics specifically mediate gut-derived CVD risk factors. Most studies chiefly demonstrate the role of prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics in maintaining the balance of gut microbiota, strengthening the gut barrier, improving the beneficial bacteria, and suppressing harmful bacteria and their metabolites. Investigating the molecular mechanism of particular foods and herbs (prebiotic, probiotic, and postbiotic) could explain how these substances interact with the metaorganism to achieve CVD treatment and prevention.

4.4. Antibiotic-like substances

An antibiotic-like substance is a compound possessing antimicrobial properties that can be derived from food, plants, and herbs.113 Several ingredients in food exhibit antimicrobial activity, especially in spices and herbs. The intake of herbs can affect the gut microbiota. Some studies suggest that the intake of uncooked food can affect the gut-microbiota composition because raw food possesses antimicrobial agents; cooking may result in the inactivation of such agents, reducing the antimicrobial activity against the gut microbiome.114 Several studies have reported the effects of food components against CVD through the gut-microbiota pathway, especially against TMAO modulation, because it is a well-documented pathway. For example, garlic (Allium sativum L.) has a long history of use as a spice in human food and as a dietary treatment for cardiovascular and other diseases.115, 116, 117, 118 Garlic is a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent that exhibits natural antibiotic-like activity.119 Allicin is the primary compound in raw garlic; when garlic cloves are crushed, alliin is converted into allicin by the enzyme alliinase.120 Allicin has been reported to modify the gut microbiome associated with fatty liver disease.14,121,122 Allicin supplementation also reportedly altered the gut-microbiota composition and decreased TMAO generation by the gut microbiota in mice administered carnitine (Table 4).123 Allicin relieves atherosclerosis in ApoE−/−, and raw garlic juice (containing allicin) reduces plasma TMAO and increases beneficial bacteria, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Akkermansia spp. in humans. Moreover, it is capable of inhibiting the γBB-producing bacteria (Proteus penneri, Escherichia fergusonii, and Edwardsiella tarda) and TMA-producing bacteria (Emergencia timonensis) and high-TMAO-producing microbiota to produce γBB and TMA.124 Daily intake of aged garlic extract containing S-allylcysteine for three months by humans was found to reduce central blood pressure, pulse pressure, arterial stiffness, and levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6, as well as to improve gut microbiota in terms of microbial richness, diversity, and proportion of beneficial Lactobacillus and Clostridium spp.125

Table 4.

Foods and herbs as antibiotic-like substances for CVD prevention through modulation of gut microbiota and their metabolites.

| Antibiotic-like substances | Study model | Important finding | Effect on gut microbiota and their metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw garlic (Allicin)123 | Male C57BL/6 mice fed with 0.02% ʟ-carnitine in the drinking water and supplemented with 10 mg/kg/day allicin by oral gavage. | Allicin reduced plasma TMAO and influenced gut-microbiota composition. | Plasma TMAO levels ↓, gut-microbiota composition was modified, and Robinsoniella peoriensis ↓. |

| Raw garlic juice and allicin124 | Male C57BL/6 and Female ApoE−/− mice with 1.3% ʟ-carnitine in the drinking water and supplemented with 10 mg/kg/day allicin by oral gavage. Human subjects exhibiting high TMAO production intake 55 mL of raw garlic juice (48 mg of allicin equivalent) once a day for one week. Gut-microbiota inhibition study of raw garlic juice and allicin against carnitine → γBB → TMA pathways using in vitro and ex vivo models. | Allicin alleviates atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. Raw garlic juice reduced TMAO-producing capacity and shaped the gut microbiome by enhancing beneficial gut bacteria in humans. Raw garlic juice and allicin inhibited microbial carnitine → γBB → TMA pathways in vitro and ex vivo. | Allicin significantly reduces TMA, TMAO, and γBB in C57BL/6 mice. Allicin decreases TMA/TMAO, and changes the microbiome shifts in ApoE−/− mice. Raw garlic juice reduces plasma TMAO and increases beneficial bacteria, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Akkermansia spp. in humans. Allicin and raw garlic juice inhibit the γBB-producing bacteria (Proteus penneri, Escherichia fergusonii, and Edwardsiella tarda) and TMA-producing bacteria (Emergencia timonensis) and high-TMAO producer microbiota to produce γBB and TMA. |

| Aged garlic extract125 | Participants with uncontrolled hypertension completed a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial, intake of aged garlic extract (1.2 g, containing 1.2 mg S-allylcysteine) for 12 weeks. | Blood pressure ↓, central blood pressure ↓, pulse pressure ↓, and arterial stiffness ↓. | Gut microbial richness ↑, diversity ↑, Lactobacillus ↑, and Clostridia ↑. |

| Oolong tea extract and citrus peel polymethoxyflavones131 | Female C57BL/6 mice treated with 1.3% carnitine in drinking water for 6 weeks. Mice were fed a 1% oolong tea extract or 1% citrus peel polymethoxyflavone diet. | Both oolong tea extract and citrus peel polymethoxyflavones reduced TMAO production and protected against vascular inflammation. Oolong tea extract: necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) ↓, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) ↓, and E-selectin ↓. Citrus peel polymethoxyflavones: VCAM-1↓. |

Oolong tea extract: plasma TMAO ↓, altered gut-microbiota composition, and Lactobacillus ↑. Citrus peel polymethoxyflavones: plasma TMAO ↓, altered gut-microbiota composition, Bacteroides ↑, and Akkermansia ↑. |

| Berberine133 | Female C57BL/6J mice and ApoE−/− mice with a C57BL/6 genetic background. Mice were fed a choline diet (1% additional choline) with additional berberine (100 and 200 mg/kg bw). C57BL/6J mice and ApoE−/− mice were fed for 6 and 16 weeks, respectively. | Berberine exhibited anti-atherosclerosis effects by inhibiting commensal microbial TMA production via gut-microbiota modulation, and subsequently by inducing TMAO production by the host. | C57BL/6J mice: TMAO ↓, changed gut-microbiota composition, Alistipes ↑, Ruminiclostridium ↑, Odoribacter ↑, Anaerofustis ↑, Gastranaerophilales ↑, Desulfovibrio ↑, Roseburia ↑, Christensenellaceae ↑, Tyzzerella 3 ↑, Anaeroplasma ↑, Lachnospiraceae UCG-001 ↑. ApoE−/− mice: aortic lesions ↓, TMA ↓, TMAO ↓, FMO3 ↓, changed gut-microbiota composition, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group ↑, Bacteroidales S24-7 group ↑, Eubacterium ↑, etc., and gut-microbiota functional gene cutC ↓. |

| Resveratrol134 | Female C57BL/6J mice were administered choline (400 mg/kg bw) or TMA (40 mg/kg bw) and supplemented with resveratrol (0.4%) for 30 days. Female ApoE−/− C57BL/6J mice were administered choline (400 mg/kg bw) and supplemented with resveratrol (0.4%) for 30 days. |

Resveratrol attenuated TMAO-induced atherosclerosis by lowering TMAO levels and enhancing hepatic bile acid neosynthesis through gut-microbiota improvement. Bile acid neosynthesis was associated with the modulation of the enterohepatic FXR-FGF15 axis. | C57BL/6J mice: plasma TMA ↓, TMAO ↓, FMO3 ↑, Lactobacillus ↑, Akkermansia ↑, Bacteroides ↑, Bifidobacterium ↑, and enhanced bile acid de-conjugation and fecal excretion through the FXR-FGF15 axis. ApoE−/− mice: aortic lesions ↓, plasma TMA ↓, TMAO ↓, FMO3 ↑, total cholesterol ↓, Lactobacillus ↑, Akkermansia ↑, Bacteroides ↑, Bifidobacterium ↑, Erysipelotrichaceae spp. ↑, and enhanced bile acid de-conjugation and fecal excretion through the FXR–FGF15 axis. |

Examples of dietary phenols include blueberry and cocoa polyphenols.126,127 Dietary polyphenols can bi-directionally interact with the gut microbiota and selectively promote or inhibit microbial growth and proliferation.128 Flavonoids have been reported to maintain the balance of gut microbiota by suppressing the growth of harmful bacteria and increasing the proliferation of beneficial microorganisms.129 Tea is composed of several polyphenols, polysaccharides, and tea saponins. The beneficial effects of tea on gut-microbiota modulation have also been studied. Tea exhibited a prebiotic-like effect and could reverse gut-microbiota dysbiosis induced by several disease models.130 Oolong tea extract and citrus peel polymethoxyflavones have been reported to suppress ʟ-carnitine transformation to TMAO and reduce vascular inflammation in mice supplemented with high concentrations of ʟ-carnitine.131 Thus, tea may act as an antibiotic-like substance that affects the gut microbiota. Curcumin is a bioactive compound present in Curcuma longa. An in vitro colonic simulation study found that curcumin induced the production of butyric and propionic acids. Curcumin can be metabolized and biotransformed into other phenolic compounds.132 Berberine is an isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from herbal plants including Coptis chinensis and Berberis vulgaris. Berberine reduced TMA and TMAO levels in choline-fed mice and inhibited atherosclerotic lesion formation in ApoE knockout mice. Moreover, it shaped gut-microbiota composition, microbiome functionality, and cutC/cntA gene abundance.133 Resveratrol is a natural phytoalexin found in red wine. It ameliorated TMAO-induced atherosclerosis in ApoE knockout mice by suppressing TMA and TMAO levels. Resveratrol also enhanced the levels of such beneficial bacteria as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp. and improved bile-acid metabolism.134 Many foods and herbs exhibit antibiotic-like activities. The use of antibiotic-like foods and herbs to mediate the gut microbiota may be an excellent strategy to prevent CVD. However, the use of natural antibiotic-like substances from food and herbs may result in the inhibition of beneficial bacteria. Therefore, to successfully modulate the gut–heart axis, the antibiotic-like activity of each food/herb should be understood.

5. Conclusion

This manuscript overviews the general framework of the connection between gut microbiota and their metabolites and CVD. We presented the essential information that dietary nutrients may act as CVD risk-factor precursors in gut-microbiota metabolism. Some dietary nutrients may be precursors of CVD risk-factors. However, specific food nutrients are beneficial and essential to health. Dietary nutrients may therefore work in either way, if not consumed appropriately. Incorporated with precision medicine, identification of our gut-microbiota status and function allows us to know how to feed gut microbiota with the proper dietary substrates to achieve optimal health benefit and reduce the gut-derived risk factor. Thus, the future targeting of the gut microbiota with precision medicine may be an exciting research area. In addition, we have provided an overview of the use of foods and herbs classified as prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and antibiotic-like substances to target gut microbiota and their metabolites to prevent CVD. Such approaches can help us to understand which kinds of dietary nutrients are CVD risk-factor precursors and how to choose the proper foods/herbs as preventive medicines and self-health management tools to reduce CVD risks and achieve well-being and healthiness.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

References

- 1.Zhao D., Liu J., Wang M., Zhang X., Zhou M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: current features and implications. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(4):203–212. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth G.A., Johnson C., Abajobir A., et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noble N., Paul C., Turon H., Oldmeadow C. Which modifiable health risk behaviours are related? A systematic review of the clustering of Smoking, Nutrition, Alcohol and Physical activity ('SNAP') health risk factors. Prev Med. 2015;81:16–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke G., Stilling R.M., Kennedy P.J., Stanton C., Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G. Minireview: gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(8):1221–1238. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.David L.A., Maurice C.F., Carmody R.N., et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jie Z., Xia H., Zhong S.L., et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):845. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beale A.L., O'Donnell J.A., Nakai M.E., et al. The gut microbiome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(13) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witkowski M., Weeks T.L., Hazen S.L. Gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2020;127(4):553–570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown J.M., Hazen S.L. The gut microbial endocrine organ: bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:343–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts A.B., Gu X., Buffa J.A., et al. Development of a gut microbe-targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1407–1417. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0128-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smits L.P., Kootte R.S., Levin E., et al. Effect of vegan fecal microbiota transplantation on carnitine- and choline-derived trimethylamine-N-oxide production and vascular inflammation in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(7) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng W., Ao H., Peng C. Gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and herbal medicines. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1354. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng W., Ao H., Peng C., Yan D. Gut microbiota, a new frontier to understand traditional Chinese medicines. Pharmacol Res. 2019;142:176–191. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panyod S., Sheen L.Y. Beneficial effects of Chinese herbs in the treatment of fatty liver diseases. J Tradit Complement Med. 2020;10(3):260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand S.S., Hawkes C., de Souza R.J., et al. Food consumption and its impact on cardiovascular disease: importance of solutions focused on the globalized food system: a report from the workshop convened by the world heart federation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(14):1590–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korakas E., Dimitriadis G., Raptis A., Lambadiari V. Dietary composition and cardiovascular risk: a mediator or a bystander? Nutrients. 2018;10(12) doi: 10.3390/nu10121912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang W.H.W., Kitai T., Hazen S.L. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ Res. 2017;120(7):1183–1196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z.N., Zhao Y.Z. Gut microbiota derived metabolites in cardiovascular health and disease. Protein Cell. 2018;9(5):416–431. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0549-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim M.H., Yun K.E., Kim J., et al. Gut microbiota and metabolic health among overweight and obese individuals. Sci Rep-Uk. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76474-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kao T.W., Huang C.C. Recent progress in metabolic syndrome research and therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13) doi: 10.3390/ijms22136862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T., Roest D.I.M., Smidt H., Zoetendal E.G. In: How Fermented Foods Feed a Healthy Gut Microbiota: A Nutrition Continuum. Azcarate-Peril M.A., Arnold R.R., Bruno-Bárcena J.M., editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2019. “We are what we eat”: how diet impacts the gut microbiota in adulthood; pp. 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ercolini D., Fogliano V. Food design to feed the human gut microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(15):3754–3758. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gentile C.L., Weir T.L. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018;362(6416):776–780. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji Y., Yin Y., Li Z., Zhang W. Gut microbiota-derived components and metabolites in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Nutrients. 2019;11(8) doi: 10.3390/nu11081712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohira H., Tsutsui W., Fujioka Y. Are short chain fatty acids in gut microbiota defensive players for inflammation and atherosclerosis? J Atherosclerosis Thromb. 2017;24(7):660–672. doi: 10.5551/jat.RV17006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heianza Y., Ma W., Manson J.E., Rexrode K.M., Qi L. Gut microbiota metabolites and risk of major adverse cardiovascular disease events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(7) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bach Knudsen K.E., Laerke H.N., Hedemann M.S., et al. Impact of diet-modulated butyrate production on intestinal barrier function and inflammation. Nutrients. 2018;10(10) doi: 10.3390/nu10101499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambers E.S., Preston T., Frost G., Morrison D.J. Role of gut microbiota-generated short-chain fatty acids in metabolic and cardiovascular health. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018;7(4):198–206. doi: 10.1007/s13668-018-0248-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly J.R., Kennedy P.J., Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G., Clarke G., Hyland N.P. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marzullo P., Di Renzo L., Pugliese G., et al. From obesity through gut microbiota to cardiovascular diseases: a dangerous journey. Int J Obes Suppl. 2020;10(1):35–49. doi: 10.1038/s41367-020-0017-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin L., Zhang J. Role of intestinal microbiota and metabolites on gut homeostasis and human diseases. BMC Immunol. 2017;18(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12865-016-0187-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jamar G., Ribeiro D.A., Pisani L.P. High-fat or high-sugar diets as trigger inflammation in the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Crit Rev Food Sci. 2021;61(5):836–854. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1747046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H., He J., Jia W. The influence of gut microbiota on drug metabolism and toxicity. Expet Opin Drug Metabol Toxicol. 2016;12(1):31–40. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2016.1121234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Usami M., Miyoshi M., Yamashita H. Gut microbiota and host metabolism in liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(41):11597–11608. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao B., Lu M., Katz S.C., et al. A host lipase detoxifies bacterial lipopolysaccharides in the liver and spleen. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(18):13726–13735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koeth R.A., Lam-Galvez B.R., Kirsop J., et al. l-Carnitine in omnivorous diets induces an atherogenic gut microbial pathway in humans. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(1):373–387. doi: 10.1172/JCI94601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z.N., Roberts A.B., Buffa J.A., et al. Non-lethal inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine production for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2015;163(7):1585–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemet I., Saha P.P., Gupta N., et al. A cardiovascular disease-linked gut microbial metabolite acts via adrenergic receptors. Cell. 2020;180(5):862–877 e822. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Velmurugan G., Dinakaran V., Rajendhran J., Swaminathan K. Blood microbiota and circulating microbial metabolites in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2020;31(11):835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simo C., Garcia-Canas V. Dietary bioactive ingredients to modulate the gut microbiota-derived metabolite TMAO. New opportunities for functional food development. Food Funct. 2020;11(8):6745–6776. doi: 10.1039/d0fo01237h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bosch T.C.G., McFall-Ngai M.J. Metaorganisms as the new frontier. Zoology. 2011;114(4):185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaworska K., Hering D., Mosieniak G., et al. TMA, A forgotten uremic toxin, but not TMAO, is involved in cardiovascular pathology. Toxins. 2019;11(9) doi: 10.3390/toxins11090490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gram L., Dalgaard P. Fish spoilage bacteria--problems and solutions. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13(3):262–266. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung W., Keski-Rahkonen P., Assi N., et al. A metabolomic study of biomarkers of meat and fish intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(3):600–608. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.146639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Summers G., Wibisono R.D., Hedderley D.I., Fletcher G.C. Trimethylamine oxide content and spoilage potential of New Zealand commercial fish species. New Zeal J Mar Fresh. 2017;51(3):393–405. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ufnal M., Zadlo A., Ostaszewski R. TMAO: a small molecule of great expectations. Nutrition. 2015;31(11-12):1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dos Santos J.P., Iobbi-Nivol C., Couillault C., Giordano G., Mejean V. Molecular analysis of the trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) reductase respiratory system from a Shewanella species. J Mol Biol. 1998;284(2):421–433. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koeth R.A., Wang Z.E., Levison B.S., et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):576–585. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tilg H.A. Gut feeling about thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(25):2494–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1604458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Z.N., Klipfell E., Bennett B.J., et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472(7341):57–U82. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schiattarella G.G., Sannino A., Toscano E., et al. Gut microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(39):2948. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang W.H., Wang Z., Levison B.S., et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1575–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu Y., Jameson E., Crosatti M., et al. Carnitine metabolism to trimethylamine by an unusual Rieske-type oxygenase from human microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(11):4268–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316569111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adeva-Andany M.M., Calvo-Castro I., Fernandez-Fernandez C., Donapetry-Garcia C., Pedre-Pineiro A.M. Significance of l-carnitine for human health. IUBMB Life. 2017;69(8):578–594. doi: 10.1002/iub.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu W., Gregory J.C., Org E., et al. Gut microbial metabolite TMAO enhances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell. 2016;165(1):111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu W.F., Wang Z.N., Tang W.H.W., Hazen S.L. Gut microbe-generated trimethylamine N-oxide from dietary choline is prothrombotic in subjects. Circulation. 2017;135(17):1671–1673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seline K.G., Johein H. The determination of L-carnitine in several food samples. Food Chem. 2007;105(2):793–804. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koeth R.A., Levison B.S., Culley M.K., et al. Gamma-butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metabol. 2014;20(5):799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li X.M.S., Wang Z.N., Cajka T., et al. Untargeted metabolomics identifies trimethyllysine, a TMAO-producing nutrient precursor, as a predictor of incident cardiovascular disease risk. Jci Insight. 2018;3(6) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kazaks A., Makrecka-Kuka M., Kuka J., et al. Expression and purification of active, stabilized trimethyllysine hydroxylase. Protein Expr Purif. 2014;104:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maas M.N., Hintzen J.C.J., Porzberg M.R.B., Mecinovic J. Trimethyllysine: from carnitine biosynthesis to epigenetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24) doi: 10.3390/ijms21249451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Servillo L., D'Onofrio N., Giovane A., et al. Ruminant meat and milk contain delta-valerobetaine, another precursor of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) like gamma-butyrobetaine. Food Chem. 2018;260:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeisel S.H., da Costa K.A. Choline: an essential nutrient for public health. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(11):615–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiedeman A.M., Barr S.I., Green T.J., Xu Z., Innis S.M., Kitts D.D. Dietary choline intake: current state of knowledge across the life cycle. Nutrients. 2018;10(10) doi: 10.3390/nu10101513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ueland P.M. Choline and betaine in health and disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(1):3–15. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Craciun S., Balskus E.P. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(52):21307–21312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215689109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rath S., Heidrich B., Pieper D.H., Vital M. Uncovering the trimethylamine-producing bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2017;5 doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romano K.A., Vivas E.I., Amador-Noguez D., Rey F.E. Intestinal microbiota composition modulates choline bioavailability from diet and accumulation of the proatherogenic metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. mBio. 2015;6(2) doi: 10.1128/mBio.02481-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Craig S.A. Betaine in human nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(3):539–549. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Filipcev B., Kojic J., Krulj J., Bodroza-Solarov M., Ilic N. Betaine in cereal grains and grain-based products. Foods. 2018;7(4) doi: 10.3390/foods7040049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andreesen J.R. Glycine metabolism in anaerobes. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66(1-3):223–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00871641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jones H.J., Krober E., Stephenson J., et al. A new family of uncultivated bacteria involved in methanogenesis from the ubiquitous osmolyte glycine betaine in coastal saltmarsh sediments. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0732-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kalaras M.D., Richie J.P., Calcagnotto A., Beelman R.B. Mushrooms: a rich source of the antioxidants ergothioneine and glutathione. Food Chem. 2017;233:429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Halliwell B., Cheah I.K., Tang R.M.Y. Ergothioneine - a diet-derived antioxidant with therapeutic potential. FEBS Lett. 2018;592(20):3357–3366. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Janeiro M.H., Ramirez M.J., Milagro F.I., Martinez J.A., Solas M. Implication of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) in disease: potential biomarker or new therapeutic target. Nutrients. 2018;10(10) doi: 10.3390/nu10101398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muramatsu H., Matsuo H., Okada N., et al. Characterization of ergothionase from Burkholderia sp. HME13 and its application to enzymatic quantification of ergothioneine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(12):5389–5400. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Araujo A., Araujo W.M.C., Marquez U.M.L., Akutsu R., Nakano E.Y. Table of phenylalanine content of foods: comparative analysis of data compiled in food composition Tables. JIMD Rep. 2017;34:87–96. doi: 10.1007/8904_2016_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Górska-Warsewicz H., Laskowski W., Kulykovets O., Kudlińska-Chylak A., Czeczotko M., Rejman K. Food products as sources of protein and amino acids—the case of Poland. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1977. doi: 10.3390/nu10121977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu W.K., Chen C.C., Liu P.Y., et al. Identification of TMAO-producer phenotype and host-diet-gut dysbiosis by carnitine challenge test in human and germ-free mice. Gut. 2019;68(8):1439–1449. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu W.K., Panyod S., Liu P.Y., et al. Characterization of TMAO productivity from carnitine challenge facilitates personalized nutrition and microbiome signatures discovery. Microbiome. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00912-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moludi J., Maleki V., Jafari-Vayghyan H., Vaghef-Mehrabany E., Alizadeh M. Metabolic endotoxemia and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review about potential roles of prebiotics and probiotics. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;47(6):927–939. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ryan P.M., Stanton C., Caplice N.M. Bile acids at the cross-roads of gut microbiome-host cardiometabolic interactions. Diabetol Metab Syndrome. 2017;9:102. doi: 10.1186/s13098-017-0299-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Staley C., Weingarden A.R., Khoruts A., Sadowsky M.J. Interaction of gut microbiota with bile acid metabolism and its influence on disease states. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101(1):47–64. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-8006-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Charach G., Grosskopf I., Rabinovich A., Shochat M., Weintraub M., Rabinovich P. The association of bile acid excretion and atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4(2):95–101. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10388682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McRae M.P. Dietary fiber is beneficial for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. J Chiropr Med. 2017;16(4):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barabasi A.L., Menichetti G., Loscalzo J. The unmapped chemical complexity of our diet (vol 1, pg 33, 2019) Nat Food. 2020;1(2) 140-140. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Makki K., Deehan E.C., Walter J., Backhed F. The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(6):705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Theuwissen E., Mensink R.P. Water-soluble dietary fibers and cardiovascular disease. Physiol Behav. 2008;94(2):285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Soliman G.A. Dietary fiber, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2019;11(5) doi: 10.3390/nu11051155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun N.X., Tong L.T., Liang T.T., et al. Effect of oat and tartary buckwheat - based food on cholesterol - lowering and gut microbiota in hypercholesterolemic hamsters. J Oleo Sci. 2019;68(3):251–259. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess18221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaye D.M., Shihata W.A., Jama H.A., et al. Deficiency of prebiotic fiber and insufficient signaling through gut metabolite-sensing receptors leads to cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141(17):1393–1403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Olas B. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics-A promising strategy in prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24) doi: 10.3390/ijms21249737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang Y.A., Ames N.P., Tun H.M., Tosh S.M., Jones P.J., Khafipour E. High molecular weight barley beta-glucan alters gut microbiota toward reduced cardiovascular disease risk. Front Microbiol. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morales D., Shetty S.A., Lopez-Plaza B., et al. Modulation of human intestinal microbiota in a clinical trial by consumption of a beta-d-glucan-enriched extract obtained from Lentinula edodes. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60(6):3249–3265. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cerletti C., Esposito S., Iacoviello L. Edible mushrooms and beta-glucans: impact on human health. Nutrients. 2021;13(7) doi: 10.3390/nu13072195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Matziouridou C., Marungruang N., Nguyen T.D., Nyman M., Fak F. Lingonberries reduce atherosclerosis in Apoe(-/-) mice in association with altered gut microbiota composition and improved lipid profile. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60(5):1150–1160. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marques F.Z., Nelson E., Chu P.Y., et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice. Circulation. 2017;135(10):964–+. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hoving L.R., Katiraei S., Pronk A., et al. The prebiotic inulin modulates gut microbiota but does not ameliorate atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic APOE∗3-Leiden. CETP mice. Sci Rep-Uk. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34970-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ishibashi N., Yamazaki S. Probiotics and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(2 Suppl):465S–470S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.465s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Qiu L., Tao X.Y., Xiong H., Yu J., Wei H. Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04 exhibits a strain-specific property of lowering TMAO via the modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Food & Function. 2018;9(8):4299–4309. doi: 10.1039/c8fo00349a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chan Y.K., El-Nezami H., Chen Y., Kinnunen K., Kirjavainen P.V. Probiotic mixture VSL#3 reduce high fat diet induced vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis in ApoE(-/-) mice. Amb Express. 2016;6 doi: 10.1186/s13568-016-0229-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kasahara K., Krautkramer K.A., Org E., et al. Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(12):1461–1471. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li J., Lin S.Q., Vanhoutte P.M., Woo C.W., Xu A.M. Akkermansia muciniphila protects against atherosclerosis by preventing metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in apoe(-/-) mice. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2434–+. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peluzio M.D.G., Martinez J.A., Milagro F.I. Postbiotics: metabolites and mechanisms involved in microbiota-host interactions. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;108:11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hadi A., Pourmasoumi M., Kazemi M., Najafgholizadeh A., Marx W. Efficacy of synbiotic interventions on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1888278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Simon E., Calinoiu L.F., Mitrea L., Vodnar D.C. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics: implications and beneficial effects against irritable bowel syndrome. Nutrients. 2021;13(6) doi: 10.3390/nu13062112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kvakova M., Bertkova I., Stofilova J., Savidge T.C. Co-encapsulated synbiotics and immobilized probiotics in human health and gut microbiota modulation. Foods. 2021;10(6) doi: 10.3390/foods10061297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zolkiewicz J., Marzec A., Ruszczynski M., Feleszko W. Postbiotics-A step beyond pre- and probiotics. Nutrients. 2020;12(8) doi: 10.3390/nu12082189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Natarajan N., Hori D., Flavahan S., et al. Microbial short chain fatty acid metabolites lower blood pressure via endothelial G protein-coupled receptor 41. Physiol Genom. 2016;48(11):826–834. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00089.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bartolomaeus H., Balogh A., Yakoub M., et al. Short-chain fatty acid propionate protects from hypertensive cardiovascular damage. Circulation. 2019;139(11):1407–1421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Plovier H., Everard A., Druart C., et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):107–113. doi: 10.1038/nm.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yoon H.S., Cho C.H., Yun M.S., et al. Akkermansia muciniphila secretes a glucagon-like peptide-1-inducing protein that improves glucose homeostasis and ameliorates metabolic disease in mice. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6(5):563–573. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00880-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Waksman S.A. What is an antibiotic or an antibiotic substance. Mycologia. 1947;39(5):565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Carmody R.N., Bisanz J.E., Bowen B.P., et al. Cooking shapes the structure and function of the gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(12):2052–2063. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0569-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Banerjee S.K., Maulik S.K. Effect of garlic on cardiovascular disorders: a review. Nutr J. 2002;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liperoti R., Vetrano D.L., Bernabei R., Onder G. Herbal medications in cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(9):1188–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rahman K., Lowe G.M. Garlic and cardiovascular disease: a critical review. J Nutr. 2006;136(3 Suppl):736S–740S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.736S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sobenin I.A., Pryanishnikov V.V., Kunnova L.M., Rabinovich Y.A., Martirosyan D.M., Orekhov A.N. The effects of time-released garlic powder tablets on multifunctional cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary artery disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9 doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Harris J.C., Cottrell S.L., Plummer S., Lloyd D. Antimicrobial properties of Allium sativum (garlic) Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;57(3):282–286. doi: 10.1007/s002530100722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ankri S., Mirelman D. Antimicrobial properties of allicin from garlic. Microb Infect. 1999;1(2):125–129. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]