Abstract

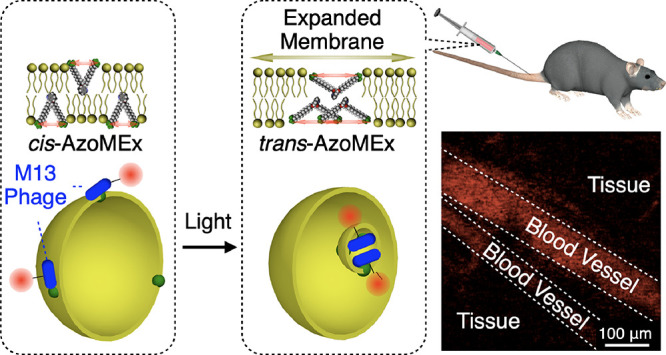

Biological membranes are functionalized by membrane-associated protein machinery. Membrane-associated transport processes, such as endocytosis, represent a fundamental and universal function mediated by membrane-deforming protein machines, by which small biomolecules and even micrometer-size substances can be transported via encapsulation into membrane vesicles. Although synthetic molecules that induce dynamic membrane deformation have been reported, a molecular approach enabling membrane transport in which membrane deformation is coupled with substance binding and transport remains critically lacking. Here, we developed an amphiphilic molecular machine containing a photoresponsive diazocine core (AzoMEx) that localizes in a phospholipid membrane. Upon photoirradiation, AzoMEx expands the liposomal membrane to bias vesicles toward outside-in fission in the membrane deformation process. Cargo components, including micrometer-size M13 bacteriophages that interact with AzoMEx, are efficiently incorporated into the vesicles through the outside-in fission. Encapsulated M13 bacteriophages are transiently protected from the external environment and therefore retain biological activity during distribution throughout the body via the blood following administration. This research developed a molecular approach using synthetic molecular machinery for membrane functionalization to transport micrometer-size substances and objects via vesicle encapsulation. The molecular design demonstrated in this study to expand the membrane for deformation and binding to a cargo component can lead to the development of drug delivery materials and chemical tools for controlling cellular activities.

Introduction

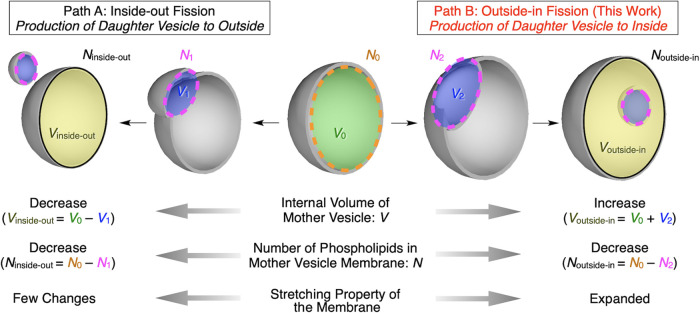

Biological membranes are essential components that regulate vital activities of cells and tissues. Major roles of membranes include segregating intra-/extracellular media, transport of substances and signals, and cell adhesion. Importantly, membrane proteins play central roles in these functions; therefore, the development of synthetic mimics is an effective approach for functionalizing artificial membranes for fabrication of membrane-based materials and regulating cellular membrane activities for biological studies. Among biological membrane transport systems, endocytosis1−14 is a universal cellular process in which a variety of extracellular substances, ranging from small biomolecules to micrometer-size substances that interact with the cell surface, are taken up via outside-in vesicle fission. Endocytic vesicle fission is closely related to viral infection,3−5 phagocytosis associated with immune responses,6,7 and signal transduction in neurons.8−11 In cellular endocytosis, biomolecular machines hybridized with phospholipid membranes, such as the clathrin/adaptor complex,12−14 enable the uptake of external substances in conjunction with outside-in vesicle fission. Although synthetic molecules that trigger dynamic membrane deformation and fusion have been reported,15−41 a molecular approach that enables endocytosis-like transport in which membrane deformation is synchronized with substance transport remains critically unexplored. Artificial vesicles such as polymersomes and dendrimersomes have also been developed for the design of dynamic membrane materials.42−45 However, adsorptions of colloidal objects onto membranes or changes in the external environment such as osmotic pressure are required in these systems for changing the membrane curvature or membrane tension, respectively, to induce membrane deformations. An important consideration for the realization of endocytosis-like fission is how to bias vesicles toward outside-in fission rather than inside-out fission. Vesicle fission is affected by several fundamental factors, such as the internal volume (V) of the vesicle and the number of lipid molecules (N) in the vesicular membrane. For example, inside-out fission resulting in the release of a daughter vesicle (i.e., outward budding) decreases both the Vinside-out and Ninside-out of the remaining mother vesicle relative to the original vesicle (Figure 1, path A). In contrast, outside-in fission (i.e., inward budding) increases the Voutside-in of the mother vesicle by incorporating external aqueous solution, despite the decrease in Noutside-in (Figure 1, path B).22 These relationships between V and N, which are associated with the stretching properties of the membrane during vesicle fission (Figure 1), suggest that membrane expansion would be a reasonable approach for biasing vesicles toward outside-in fission rather than inside-out fission. To this end, in the present study, we designed an amphiphilic, membrane-expanding molecular machine containing a diazocine core (AzoMEx; Figure 2a,b)46 that undergoes photoisomerization-associated mechanical opening/closing motions47,48 to change the distance between its two cationic hydrophilic moieties. AzoMEx embedded in a 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) giant unilamellar vesicle (GUVDOPC/AzoMEx) expands the liposomal membrane via photoisomerization to eventually induce outside-in fission. Micrometer-size M13 bacteriophage (M13 phage), which interacts with AzoMEx embedded in the GUVDOPC/AzoMEx membrane, is incorporated into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx more efficiently via the light-triggered outside-in fission than conventional encapsulation methods. Encapsulated M13 phages are transiently protected from the external environment, which preserves their infectivity. This method thus enables the delivery of M13 phages throughout the body after administration through the blood.

Figure 1.

Comparison of inside-out (path A) and outside-in fission (path B) processes in terms of internal volume of the mother vesicle, V (V0, V1, V2, Vinside-out, and Voutside-in), the number of phospholipid molecules in the mother vesicle membrane, N (N0, N1, N2, Ninside-out, and Noutside-in), and the stretching property of the membrane. Green sphere, blue spheres, and yellow spheres indicate V of the original vesicle, the daughter vesicle, and the mother vesicle after fission, respectively. N of corresponding vesicles is indicated with orange and magenta dashed lines and black lines, respectively.

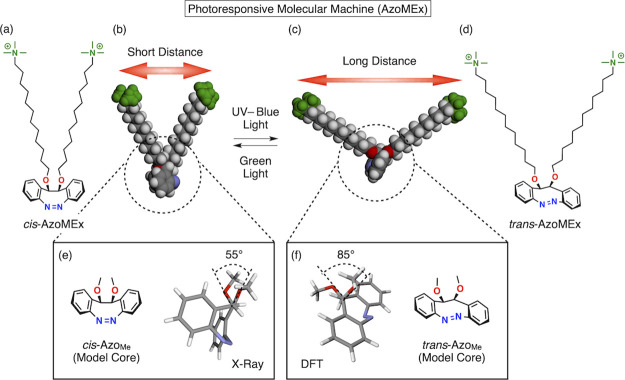

Figure 2.

(a, d) Molecular structures of a photoresponsive molecular machine, AzoMEx, in its cis-form (a) and trans-form (d) consisting of a diazocine core with appending −NMe3+ groups and an alkoxide spacer. (b, c) Schematic images of the mechanical motion of AzoMEx during cis–trans photoisomerization, which changes the distance between the −NMe3+ groups upon UV–blue (for cis-to-trans isomerization) and green (for trans-to-cis isomerization) light irradiation. By the surface pressure and area (π–A) isotherms of cis- and trans-AzoMEx, their molecular areas were estimated to be 0.25 ± 0.02 and 0.32 ± 0.01 nm2/mol, respectively (Figure 3d). Compared to the experimentally estimated areas, the molecular models in (b) and (c) showed comparable molecular areas (cis-AzoMEx: 0.23 nm2/mol, trans-AzoMEx: 0.33 nm2/mol, Figure S1). (e, f) Molecular structures of AzoMe, a model compound corresponding to the core of AzoMEx, in its cis-form (e) and trans-form (f). (e) X-ray crystallographic structure of cis-AzoMe and (f) calculated structure of trans-AzoMe (density functional B3LYP 6-311+G**) showing the torsional angles of the O–C–C–O bond in each form.

Results and Discussion

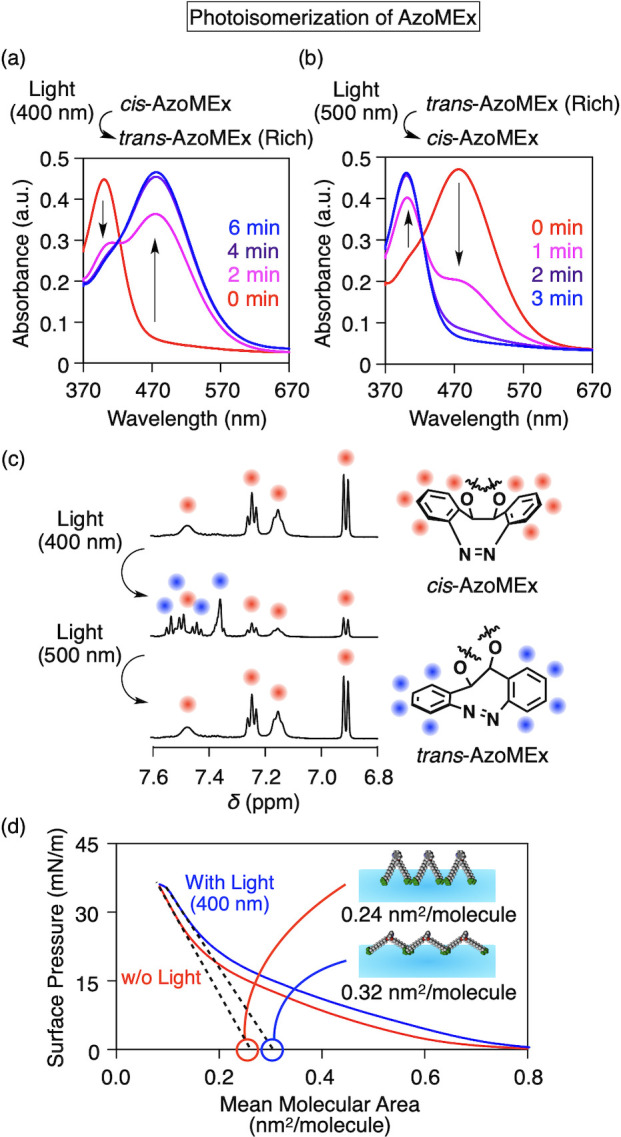

Structural Change in AzoMEx via Photoisomerization of the Diazocine Core

The AzoMEx membrane-expanding molecular machine consists of a diazocine-based core bearing two alkoxide chains with a hydrophilic quaternary ammonium group (−NMe3+) at each terminus (Figure 2a–d). Due to the bridged structure, the bent cis conformation is a thermodynamically stable isomer of the diazocine core. The amphiphilic structure of AzoMEx is suitable for insertion into phospholipid membranes, in which the two hydrophilic −NMe3+ groups would be exposed to the aqueous solution, and the distance between the −NMe3+ groups can be extended in conjunction with the cis-to-trans conformational change of the diazocine core (Figure 2b,c, and Figure S1). X-ray crystallographic analysis of cis-AzoMe, a dimethyl derivative of AzoMEx regarded as a model core structure, showed that the dihedral angle θcis of the O–C–C–O bond is 55° (Figure 2e). A comparable dihedral angle was also indicated by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (calculated θcis = 53°, Figure S2). DFT calculations of trans-AzoMe showed an increase in the corresponding angle θtrans to 85° (Figure 2f) due to the torsion of the azobenzene core. We investigated the changes in the properties of AzoMEx during photoisomerization in phospholipid-free solutions. Upon irradiation with UV–blue light (λ = 400 nm) in MeOH, cis-AzoMEx (880 μM) showed a change in the absorption spectrum, with the appearance of a more intense absorption band at 476 nm and a decrease in the absorption intensity at 400 nm, with an isosbestic point at 425 nm (Figure 3a). These characteristics are indicative of cis-to-trans isomerization of the diazocine core.46 The spectrum returned to the original state upon subsequent green-light irradiation (λ = 500 nm) for 15 min (Figure 3b). As calculated based on the intensities of 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic signals corresponding to the aromatic protons of the diazocine core (Figure 3c) and analyses of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fractions (Figure S6), 65–70% of cis-AzoMEx isomerized to trans-AzoMEx after UV–blue-light irradiation and the subsequent green-light irradiation allowed for a nearly quantitative backward isomerization to cis-AzoMEx (Figure 3c and Figure S6). We measured the surface pressure and area (π–A) isotherms of Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) films of AzoMEx at the air/water interface and evaluated the molecular occupied areas of cis- and trans-AzoMEx via extrapolation analysis of π–A curves (Figure 3d and Figure S7).49 Interestingly, the molecular occupied area of cis-AzoMEx increased from 0.25 ± 0.02 (Figure 3d, red) to 0.32 ± 0.01 nm2/molecule after UV–blue-light irradiation for 10 min (Figure 3d, blue). Considering the ratio between cis- and trans-AzoMEx based on NMR analysis of a sample irradiated with UV–blue light ([cis-AzoMEx]/[trans-AzoMEx] = 30/70) (Figure 3c), the molecular occupied area of trans-AzoMEx was estimated at 0.35 nm2/molecule. This result clearly demonstrates the mechanical expansion motion of AzoMEx due to cis-to-trans photoisomerization.

Figure 3.

Changes in UV–vis absorption spectra of AzoMEx (880 μM) in MeOH upon irradiation with 400 nm light for 6 min (a) and subsequent irradiation with 500 nm light for 3 min (b) at 25 °C. (c) 1H NMR spectra of AzoMEx in CD3OD before (upper) and after irradiation with 400 nm light for 10 min (middle) and subsequent irradiation with 500 nm light for 3 min (lower). Signals marked with red and blue circles are assignable to aromatic protons of cis-AzoMEx and trans-AzoMEx, respectively. The molar ratio between cis-AzoMEx and trans-AzoMEx after irradiation with 400 nm light in the NMR analysis was calculated as [cis-AzoMEx]/[trans-AzoMEx] = 30/70. (d) π–A curves of monolayers of AzoMEx before (red) and after (blue) irradiation with 400 nm light for 10 min.

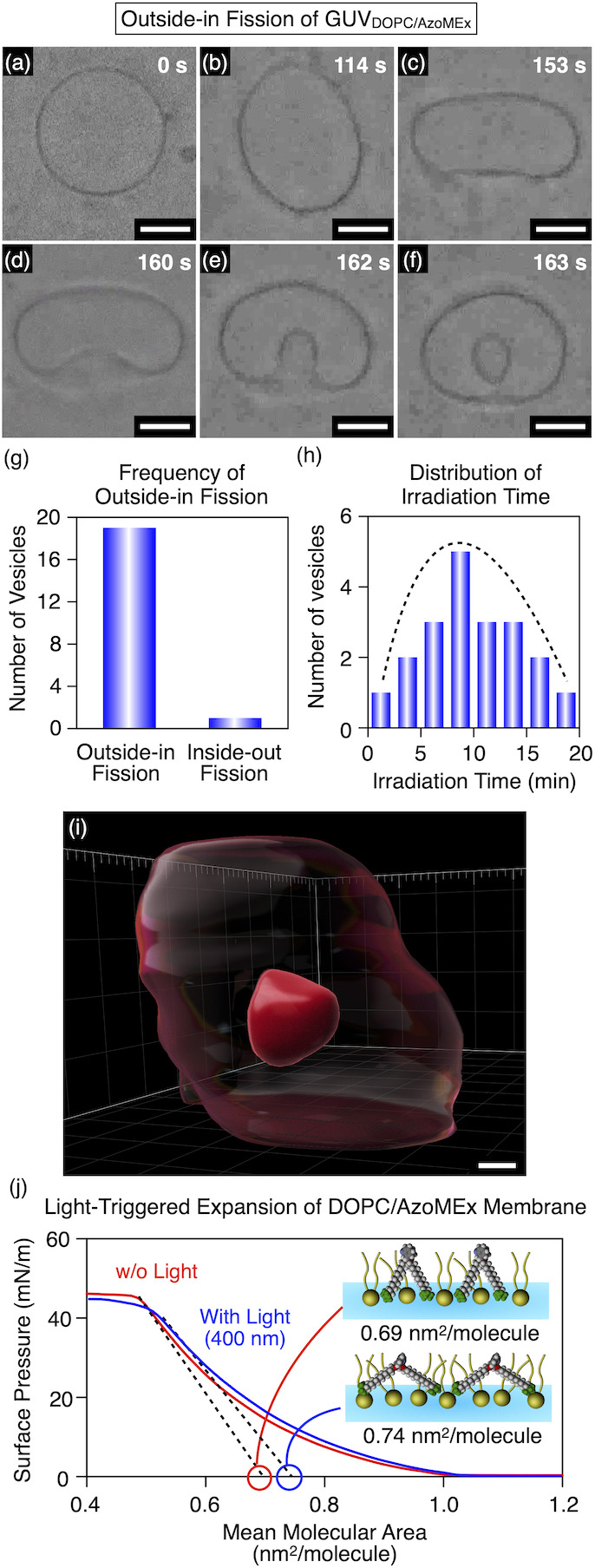

Light-Triggered Outside-in Fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx

By gentle hydration of a mixture of DOPC and AzoMEx evaporated from an organic solution, a giant unilamellar vesicle GUVDOPC/AzoMEx composed of DOPC and AzoMEx was prepared (180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx, Figure 4a). Interestingly, under phase-contrast microscopic observation with UV–blue-light irradiation, GUVDOPC/AzoMEx exhibited membrane fluctuation (Figure 4b), transformation into a flattened vesicle (Figure 4c), inward budding (Figure 4d,e), and eventually outside-in fission, which produced a daughter vesicle encapsulating the outer solution (Figure 4f, Figure S8, and Movie S1 for 370 nm irradiation, and Figure S9 for 420 nm irradiation). Of 20 GUVDOPC/AzoMEx observed for membrane deformation, 19 (95%) underwent outside-in fission, and one of them showed inside-out fission producing a daughter vesicle to the outside of the mother vesicle (Figure 4g and Figure S9). Based on a flow cytometric analysis using rhodamine dye-encapsulated GUVDOPC/AzoMEx, it was estimated that approximately half of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx underwent light-triggered outside-in fission (Figure S10). We also confirmed that the fission process ended within 20 min after irradiation with 370 nm light (Figure 4h and Figure S8), and the process was essentially irreversible, as no membrane deformation was observed upon green-light irradiation (λ = 540 nm) for 2 min following UV–blue-light irradiation (Figure S11). Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) 3D imaging of fluorescent Cy5-labeled GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (178 μM DOPC, 2 μM Cy5-labeled DOPE, 20 μM AzoMEx) irradiated with UV–blue light (λ = 400 nm) for 15 min suggested that the daughter vesicles generated by outside-in fission were spatially separated from the mother vesicle (Figure 4i and Figure S12). The average molecular area of LB films of a mixture of DOPC and AzoMEx ([DOPC]/[AzoMEx] = 90/10, mol/mol), which serves as a model GUVDOPC/AzoMEx membrane, increased from 0.69 ± 0.02 to 0.73 ± 0.01 nm2/molecule after UV–blue-light irradiation (Figure 4j and Figure S7). Also, the fluctuation in the GUVDOPC/AzoMEx membrane was amplified during the initial stage of the outside-in fission process (Figure 4a–c), as revealed by elliptical, triangular, and spatial fluctuations in the microscopic images (Figure S13), and this can reflect a decrease in the effective tension of the GUVDOPC/AzoMEx membrane.50,51 These results suggest that the cis-to-trans photoisomerization of AzoMEx (Figure S14) expands the GUVDOPC/AzoMEx membrane and likely biases the process toward outside-in fission (Figures 1 and 4j). Molecular dynamic (MD) simulation52 supported that trans-AzoMEx adopts its open-form conformation with an expanded distance between the two −NMe3+ groups not only in solution but also in a lipid membrane (Figure S15 and Movie S2). Photooxidation of the phospholipids or heat generation, which were possibly caused by UV–blue-light irradiation, induced only minimal membrane deformation (Figure S16). Because AzoMEx was poorly soluble in water, as confirmed by absorption spectroscopy (Figure S17), dissociation of AzoMEx from the liposomal membranes would be suppressed and outside-in fission can be induced when the GUVDOPC/AzoMEx concentration was varied from 80 μM (72 μM DOPC, 8 μM AzoMEx) to 400 μM (360 μM DOPC, 40 μM) (Figure S18). On the other hand, the ratio of AzoMEx in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx was important so that outside-in fission was observed only in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx containing 10–20 mol % AzoMEx (Figure S19). Membrane fluidity can be also an important factor for the light-triggered membrane deformation since deformation was not observed in the GUVs containing AzoMEx made of a crosslinked phospholipid or 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine forming a less-fluidic gel phase membrane (Figure S20). The light-triggered membrane deformation was suppressed by osmotic difference (Figure S21). These results indicate the importance of membrane fluidity and osmotic conditions for light-triggered membrane deformation.

Figure 4.

(a–f) Time-course phase-contrast microscopic observation of outside-in fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) in water under irradiation with 370 nm light for 162 s. Snapshots were taken at 0 s (a), 114 s (b), 153 s (c), 160 s (d), 162 s (e), and 163 s (f) after starting irradiation with 370 nm light. Scale bars: 5 μm. (g) Number of outside-in and inside-out fission events among 20 arbitrarily selected events of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx fission. (h) Histogram of the duration of light irradiation (λ = 370 nm) required to complete GUVDOPC/AzoMEx fission events among the 20 arbitrarily selected samples. (i) 3D CLSM image of a GUVDOPC/AzoMEx containing Cy5-labeled DOPE (178 μM DOPC, 2 μM Cy5-labeled DOPE, 20 μM AzoMEx) in water after irradiation with 400 nm light for 15 min. The transparent and the opaque red parts denote the mother vesicle and daughter vesicle, respectively. Scale bar: 1 μm. (j) π–A curves of monolayers of a mixture of DOPC and cis-AzoMEx ([DOPC]/[AzoMEx] = 90/10, mol/mol) before (red) and after (blue) irradiation with 400 nm light for 10 min.

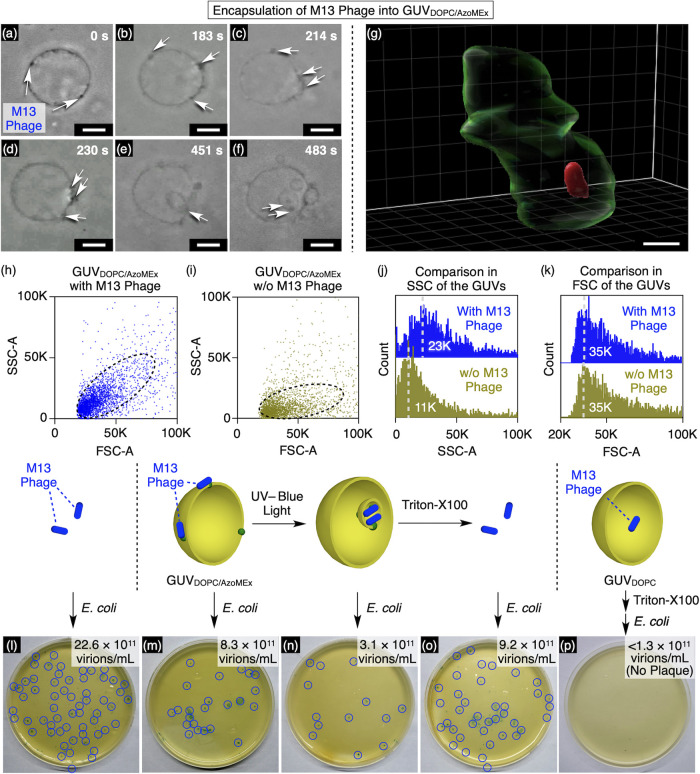

Incorporation of M13 Phages into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx via Endocytosis-Like Vesicle Fission

One of the important biological functions of endocytosis is the transport of membrane-bound large objects such as micrometer-size viruses, which are not readily transported through channels. To mimic biological endocytosis, we explored the use of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx to encapsulate M13 phages via light-triggered outside-in fission. M13 phages are rod-shaped, ∼1 μm-long viruses with an anionic surface, and they are typically used in phage displays to identify peptides that bind target molecules.53−59 Upon mixing M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL) with GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx), dark spots were observed on GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (Figure 5a). These spots were likely associated with M13 phages adsorbed onto cationic AzoMEx in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx, as similar dark spots were observed in a mixture of M13 phages and cationic 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP)-doped GUVDOPC (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phages, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM DOTAP), whereas these spots were not observed upon mixing M13 phages with GUVDOPC (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phage, 200 μM DOPC) (Figure S22). Unexpectedly, after 230 s of UV–blue-light irradiation of the mixture, the M13 phages bound to GUVDOPC/AzoMEx started to accumulate in the area of the membrane deformation (Figure 5a–d and Movie S3), and the M13 phages were eventually incorporated into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (Figure 5e,f). Also, CLSM of fluorescent Cy5-labeled M13 phages (M13 phageCy5) mixed with rhodamine-labeled GUVDOPC/AzoMEx revealed encapsulation of M13 phageCy5 into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx after the light irradiation (Figure 5g and Figure S23). This observation allowed us to predict that AzoMEx, which interacts with M13 phages, assembles in the area of membrane deformation in the outside-in fission process and can thereby contribute to the efficient incorporation of M13 phages and even membrane deformation. Indeed, the self-assembly of cationic AzoMEx in liposomal membranes under UV–blue-light irradiation was further supported by CLSM observation of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx containing fluorescent Cy5-labeled AzoMEx (Figure S24), localization of anionic polystyrene (PS) beads on the UV–blue light-irradiated GUVDOPC/AzoMEx membrane (Figure S25), the zeta potential profile of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (Figure S26), phase-mode atomic force microscopy (AFM) observations of a mixed membrane of DOPC and AzoMEx (Figure S27), and DFT calculations of the dipole moments at the diazocine core of AzoMEx (Figure S28). A decrease in the concentration of AzoMEx (190 μM DOPC, 10 μM AzoMEx) suppressed its assembly after the photoisomerization (Figure S29). Meanwhile, AFM observation indicated that AzoMEx in the cis form was dispersed in a DOPC membrane even in an increased concentration (160 μM DOPC, 40 μM AzoMEx, Figure S29), which was also supported by scattered localization of PS beads on the membrane (Figure S29). Therefore, cis- and trans-forms of AzoMEx have different self-assembling properties with a concentration dependency, i.e., cis-AzoMEx has a relatively high dispersity even at [AzoMEx]/[DOPC] = 20/80, while trans-AzoMEx forms assembly even at [AzoMEx]/[DOPC] = 10/90. According to the multi-domain area difference elasticity model, domain formation in a phospholipid membrane can lead to membrane deformation by reducing the unstable domain boundary.22 Here, as shown in the M13 phage encapsulation process (Figure 5a–f), the membrane deformation occurred after the assembly of AzoMEx. That is, it is likely that AzoMEx can assemble faster than the membrane deformation; therefore, endocytosis should occur from the spontaneously grown domain. The light-triggered membrane expansion and self-assembly of AzoMEx possibly facilitate the inward budding to elicit endocytosis-like outside-in fission. CLSM observation of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx containing Cy5-labeled AzoMEx showed weak fluorescence of Cy5-labeled AzoMEx in the membrane of the mother vesicle after the light-triggered outside-in fission (Figure S24), suggesting that a part of AzoMEx molecules remained in the membrane of the mother vesicle after the fission. Here, AFM observation suggested dispersion of cis-AzoNH2, a non-charged derivative of AzoMEx appending −NH2 groups at the termini, in the DOPC membrane, and only small aggregates were observed in the mixture of DOPC and trans-AzoNH2 (Figure S30). Since the π–A isotherm of DOPC/cis-AzoNH2 LB film showed collapse of the monolayer at significantly low pressure (Figure S31), it is suggested that AzoNH2 disturbs the lipid packing, possibly by inhomogeneous orientation in the membrane. Importantly, GUVs made of a mixture of DOPC and AzoNH2 neither showed light-triggered membrane deformation (Figure S32) nor bound with the M13 phage (Figure S33). Therefore, it is likely that the cationic charges of AzoMEx contribute to its directed orientation in the membrane and binding with the M13 phage by exposure to the aqueous phase. The self-assembly of AzoMEx upon its cis-to-trans isomerization should be mainly promoted by increased hydrophobicity at the diazocine core allowing for efficient lateral packing, and the resulting domain formation would induce membrane deformation. Flow cytometry analysis of a GUVDOPC/AzoMEx sample irradiated for 15 min with UV–blue light (λ = 400 nm) in the presence of M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phage, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) revealed a higher side scattering (SSC) profile (Figure 5h,j, peak top at 23 K) compared with irradiation of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx without M13 phages (Figure 5i,j, peak top at 11 K). As the SSC profile reflects the refractive index due to the internal structure of the particles,60 this result indicates that the M13 phages hybridized with GUVDOPC/AzoMEx. In this hybridization process, GUVDOPC/AzoMEx did not aggregate, because the forward scattering (FSC) profiles, which reflect particle size,60 were almost identical, regardless of the presence of M13 phages (Figure 5h,i,k, peak top at 35 K in both cases). The infectivity of M13 phages for Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells was monitored to evaluate the activity of M13 phages hybridized with GUVDOPC/AzoMEx. First, we incubated a mixture of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx and M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phage, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) in Tris–HCl buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0) at 25 °C for 1 h, and unbound M13 phages were subsequently removed by centrifugation (286,000 g) for 60 min, followed by re-dispersion of the precipitate in water. The resulting mixture was allowed to interact with E. coli cells (optical density at 600 nm > 0.5) in lysogeny broth medium at room temperature for 2 min, and the E. coli cells were then cultured at 37 °C overnight on hydrogel plates (X-gal plates) containing lysogeny broth medium, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal), and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The E. coli cells infected with M13 phages express β-galactosidase encoded by the M13 phage gene, and this enzyme degrades X-gal to produce a blue indigo dye. The degree of infection with M13 phages can thus be evaluated by the number of spots that appear on plates containing X-gal (plaque assay).61 In the present study, M13 phages mixed with GUVDOPC/AzoMEx exhibited 37% of the infectivity of M13 phages not mixed with GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (Figure 5l, [22.6 ± 5.3] × 1011 virions/mL, 100% [standard for comparison]). When the M13 phage/GUVDOPC/AzoMEx mixture (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phages, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) was irradiated with 400 nm light for 15 min to induce the outside-in fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx, the M13 phage infectivity decreased to 14% of that of the standard (Figure 5n, [3.1 ± 0.3] × 1011 virions/mL), suggesting that the encapsulated M13 phages were prevented from interacting with E. coli. Importantly, M13 phages in this sample retained their infectivity even after incorporation into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx. When the light-irradiated mixture was treated with Triton X-100 (1 wt %) for 30 min to lyse GUVDOPC/AzoMEx, the infectivity of the M13 phages recovered (Figure 5o, [9.2 ± 3.7] × 1011 virions/mL, 41% relative to the standard in Figure 5l) to the same level as the non-irradiated mixture of M13 phages and GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (Figure 5m, [8.3 ± 2.6] × 1011 virions/mL, 37% relative to the standard in Figure 5l). Notably, the endocytosis-like fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx encapsulated a markedly greater number of M13 phages (Figure 5o, 41% relative to the standard in Figure 5l) than a conventional gentle hydration method62 (Figure 5p, <1.3 × 1011 virions/mL, <6% relative to the standard in Figure 5l), as evaluated by the plaque assay, suggesting that GUVDOPC/AzoMEx is a useful carrier of micrometer-size M13 phages.

Figure 5.

(a–f) Phase-contrast microscopic observations of the uptake of M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL) into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) in Tris–HCl buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0) under irradiation with 370 nm light for 483 s. Snapshots were taken at 0 s (a), 183 s (b), 214 s (c), 230 s (d), 451 s (e), and 483 s (f) after starting the irradiation with 370 nm light. Scale bars: 5 μm. White arrows indicate M13 phages. (g) 3D CLSM image of a GUVDOPC/AzoMEx containing rhodamine-labeled DOPE (178 μM DOPC, 2 μM rhodamine-labeled DOPE, 20 μM AzoMEx) and M13 phagesCy5 (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL) in water after irradiation with 400 nm light for 15 min. The transparent green parts and the opaque red parts denote the GUVDOPC/AzoMEx and M13 phagesCy5, respectively. Scale bar: 2 μm. FSC-SSC scatterplots in flow cytometry analyses of light-irradiated (λ = 400 nm) GUVDOPC/AzoMEx samples (180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) with (h) and without (i) M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL) and the SSC (j) and FSC (k) distributions. Plaque assays of M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL) (l) and mixture of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx and M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phage, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) in Tris–HCl buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0) before (m) and after (n) irradiation with 400 nm light for 15 min, and the light-irradiated sample after incubation with Triton X-100 (1 wt %) for 30 min (o). (p) Plaque assay of M13 phages encapsulated in DOPC vesicles (200 μM) in Tris–HCl buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0) using a gentle hydration method. The sample was mixed with Triton X-100 (1 wt %) for 30 min before the plaque assay. The number of M13 phages in (l–p) as calculated by the plaque assay was (22.6 ± 5.3) × 1011 virions/mL (l), (8.3 ± 2.6) × 1011 virions/mL (m), (3.1 ± 0.3) × 1011 virions/mL (n), (9.2 ± 3.7) × 1011 virions/mL (o), and < 1.3 × 1011 virions/mL (p), respectively. Representative spots of M13 phage–infected E. coli in (l–o) are indicated by blue circles.

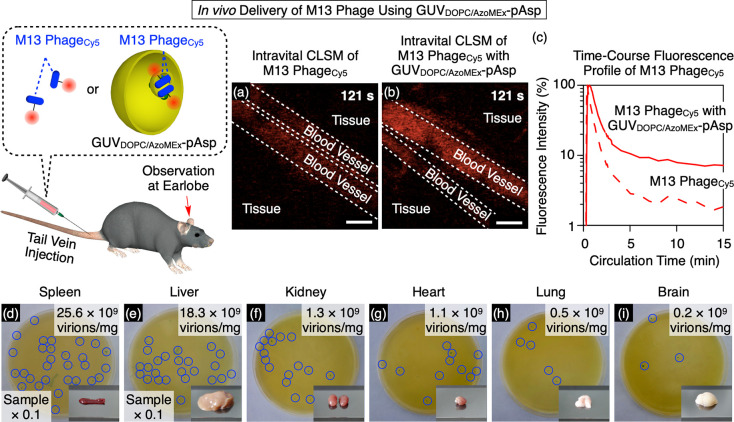

Administration of M13 Phages Encapsulated in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx through the Blood

Based on the effective encapsulation of M13 phages by GUVDOPC/AzoMEx, we examined the administration of encapsulated M13 phages through the blood. M13 phageCy5 encapsulated in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx were administered to mice via the tail vein. The stability of the phages in vivo was evaluated by observing the blood vessels in the earlobes using intravital CLSM,63,64 and the infectivity of non-labeled M13 phages distributed to the organs following administration was evaluated using the plaque assay. As outside-in fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx occurred in a glucose (50 mg/mL) solution isotonic with blood (Figure S34), we encapsulated M13 phagesCy5 within GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phage, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) in glucose-containing Tris–HCl buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mg/mL glucose, pH 7.0) under irradiation with 400 nm light for 15 min. The resulting mixture was subsequently incubated with an anionic block polymer composed of poly(aspartic acid) and poly(ethylene glycol) (2.6 mg/mL)65 in order to cover the cationic surface of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp) and prevent adsorption of vesicles onto biological tissues. Following intravenous administration of 100 μL of a solution of M13 phagesCy5 (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL) that had not been hybridized with GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp, intravital CLSM showed that the fluorescence signal derived from the Cy5 dye rapidly weakened within 121 s after injection (Figure 6a,c, 11% relative to the initial fluorescence intensity, and Movie S4), probably due to the degradation of M13 phagesCy5 in the blood vessels. In contrast, the fluorescence signal associated with M13 phagesCy5 encapsulated in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phageCy5, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) was still clearly observable in blood vessels 121 s after injection (Figure 6b,c, 26% relative to the initial fluorescence intensity, and Movie S5), and the fluorescence signal can be detected even after 15 min of circulation in the blood (Figure 6c). Encapsulation of M13 phagesCy5 in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp appears to play a more important role than the particle size of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp with regard to improving blood circulation of the phages, as there was no significant difference in the blood circulation profiles of M13 phageCy5-encapsulating GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp (or large unilamellar vesicles, LUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp) after filtration through 1 μm—for the preparation of LUVs—and 5 μm pore size filters (Figure S35). Thereafter, we extracted the liver, kidney, spleen, lung, heart, and brain 15 min after injection of M13 phages encapsulated in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp and examined the infectivity of the M13 phages distributed to these organs. Significantly, their infectivity was retained even after distribution to the respective organs through the blood circulation (spleen: [25.6 ± 13.2] × 109 virions/mg, Figure 6d; liver: [18.3 ± 3.2] × 109 virions/mg, Figure 6e; kidney: [1.3 ± 0.6] × 109 virions/mg, Figure 6f; heart: [1.1 ± 0.5] × 109 virions/mg, Figure 6g; lung: [0.5 ± 0.3] × 109 virions/mg, Figure 6h; and brain: [0.2 ± 0.1] × 109 virions/mg, Figure 6i). In contrast, M13 phages that were not hybridized with GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp prior to administration via the blood exhibited undetectable infectivity in all of the organs examined (Figure S36).

Figure 6.

Intravital CLSM images of blood vessels in a mouse earlobe 121 s after tail vein injection of 100 μL of M13 phagesCy5 (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL) (a) or GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp encapsulating M13 phagesCy5 (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phageCy5, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx) (b). Scale bars: 100 μm. (c) Time-course profiles over 15 min of the fluorescence intensity in the blood vessels of un-encapsulated M13 phagesCy5 (dashed line) and M13 phagesCy5 encapsulated into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp (solid line). Plaque assays of homogenized samples of spleen (d), liver (e), kidney (f), heart (g), lung (h), and brain (i) 15 min after injection of 100 μL of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp encapsulating M13 phages (22.6 × 1011 virions/mL M13 phage, 180 μM DOPC, 20 μM AzoMEx). The samples of spleen and liver were diluted 10-fold before the plaque assay. Insets: photographs of the corresponding organs. The number of M13 phages in (d–i) as calculated by the plaque assay was (25.6 ± 13.2) × 109 virions/mg (d), (18.3 ± 3.2) × 109 virions/mg (e), (1.3 ± 0.6) × 109 virions/mg (f), (1.1 ± 0.5) × 109 virions/mg (g), (0.5 ± 0.3) × 109 virions/mg (h), and (0.2 ± 0.1) × 109 virions/mg (i), respectively. Representative spots of M13 phage–infected E. coli in (d–i) are indicated by blue circles.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a photoresponsive membrane-expanding molecular machine, AzoMEx, which promoted endocytosis-like outside-in fission, enabling the transport of membrane-bound objects. The diazocine core of AzoMEx isomerized from the cis- to trans-form upon UV–blue-light irradiation (λ = 370–420 nm), with the torsional motion of the diazocine core producing an opening motion between the two cationic −NMe3+ groups of AzoMEx, as indicated by an increase in the molecular occupied area. Analogous to cellular endocytosis, the fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx, which enables the direct uptake of membrane-bound cargo components, effectively encapsulated micrometer-size M13 phages. M13 phages were incorporated into GUVDOPC/AzoMEx via light-driven outside-in fission more efficiently than by the conventional gentle hydration method. The M13 phages were protected from the external environment and retained their infectivity, indicating that GUVDOPC/AzoMEx is a useful carrier for M13 phages. M13 phages encapsulated in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx circulated in the blood longer after administration than bare M13 phages, enabling the delivery of M13 phages to whole organs.

This research provides a novel molecular approach using synthetic molecular machineries for membrane functionalization and transport of micrometer-size substances and objects by direct vesicle encapsulation. This approach is potentially useful for transporting biological materials under more biocompatible conditions than conventional membrane deformation induced by osmotic pressure and temperature changes. Protecting M13 phages from degradation in the blood by encapsulation and then releasing the phages in biological tissues through gradual decomposition66−69 is expected to facilitate various attractive applications of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx, such as in vivo phage display.57,58 The molecular design demonstrated in this study to expand the membrane for deformation and bind to a cargo component can lead to the development of membrane-deformable materials for encapsulation and delivery and chemical tools for controlling cellular activities.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Research Program of the “Five-star Alliance” in “NJRC Mater. & Dev.” and “Dynamic Alliance for Open Innovation Bridging Human, Environment and Materials” in the “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices”.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AzoMEx

membrane-expanding molecular machine

- -NMe3+

quaternary ammonium group

- GUV

giant unilamellar vesicle

- DOPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOTAP

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane

- DOPA

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate

- M13 phage

M13 bacteriophage

- M13 phageCy5

Cy5–labeled M13 phages

- DFT

density functional theory

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- π-A

pressure and area

- LB

Langmuir–Blodgett

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscopy

- SSC

side scattering

- FSC

forward scattering

- X-gal

β-d-galactopyranoside

- X-gal plate

hydrogel plates containing lysogeny broth medium, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactopyranoside, and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside

- E. coli

Escherichia coli.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12348.

Additional experimental details, materials, and methods, including 1H and 13C NMR spectral data, MS data, X-ray structural data, DFT calculation data, and microscopic images (PDF)

Outside-in vesicle fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (MP4)

trans-AzoMEx adopting its open-form conformation in solution (MP4)

Uptake of M13 phages by endocytosis-like vesicle fission of GUVDOPC/AzoMEx (MP4)

Intravital CLSM observation of M13 phagesCy5 at the earlobe of the mouse (MP4)

Intravital CLSM observation of M13 phagesCy5 encapsulated in GUVDOPC/AzoMEx-pAsp at the earlobe of the mouse (MP4 )

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (B) JP21H05096 (TMu), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) JP19H02828 (TMu), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas JP21H00391 (TMu), Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory) JP21K19209 (TMu), Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists JP19K15378 (NU), Japan Science Technology Agency CREST JPMJCR19S4 (TMu), FOREST JPMJFR2122 (TMu), Japan Association for Chemical Innovation (NU), Asahi Glass Foundation (NU, TMu), Moritani Foundation (NU), Tanaka Foundation (NU), Kose Cosmetology Foundation (NU), Izumi Foundation (NU), Konica Minolta Foundation (NU), Takeda Science Foundation (TMu), and Lotte Foundation (TMu).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Canton I.; Battaglia G. Endocytosis at the Nanoscale. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2718–2739. 10.1039/c2cs15309b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arandjelovic S.; Ravichandran K. S. Phagocytosis of Apoptotic Cells in Homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 907–917. 10.1038/ni.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov D. S. The Secret Life of ACE2 as a Receptor for the SARS Virus. Cell 2003, 115, 652–653. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igonet S.; Rey F. A. SnapShot: Viral and Eukaryotic Protein Fusogens. Cell 2012, 151, 1634–1634.e1. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B.; Guo H.; Zhou P.; Shi Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C.; Malta C. D.; Polito V. A.; Arencibia M. G.; Vetrini F.; Erdin S.; Erdin S. U.; Huynh T.; Medina D.; Colella P.; Sardiello M.; Rubinsztein D. C.; Ballabio A. TFEB Links Autophagy to Lysosomal Biogenesis. Science 2011, 332, 1429–1433. 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T.; Terebiznik M.; Yu L.; Silvius J.; Abidi W. M.; Philips M.; Levine T.; Kapus A.; Grinstein S. Receptor Activation Alters Inner Surface Potential during Phagocytosis. Science 2006, 313, 347–351. 10.1126/science.1129551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S.; Rost B. R.; Camacho-Pérez M.; Davis M. W.; Söhl-Kielczynski B.; Rosenmund C.; Jorgensen E. M. Ultrafast Endocytosis at Mouse Hippocampal Synapses. Nature 2013, 504, 242–247. 10.1038/nature12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin W.; Ge L.; Arpino G.; Villarreal S. A.; Hamid E.; Liu H.; Zhao W.-D.; Wen P. J.; Chiang H.-C.; Wu L.-G. Visualization of Membrane Pore in Live Cells Reveals a Dynamic-Pore Theory Governing Fusion and Endocytosis. Cell 2018, 173, 934–945.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelberg N. J.; Tsien R. Weakening Synapses to Cull Memories. Science 2019, 363, 31–32. 10.1126/science.aaw1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoli S. O.; Betz W. J. The Structural Organization of the Readily Releasable Pool of Synaptic Vesicles. Science 2004, 303, 2037–2039. 10.1126/science.1094682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner S. D.; Schmid S. L. Regulated Portals of Entry into the Cell. Nature 2003, 422, 37–44. 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhausen T. Adaptors for Clathrin-Mediated Traffic. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999, 15, 705–732. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse B. M. F.; Robinson M. S. Clathrin, Adaptors, and Sorting. Annu. Rev. Cell Bioi. 1990, 6, 151–171. 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin T. P. Recent Advances with Liposomes as Pharmaceutical Carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2005, 4, 145–160. 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick H.; Alves A. C.; Vogel H. Single-Vesicle Assays Using Liposomes and Cell-Derived Vesicles: From Modeling Complex Membrane Processes to Synthetic Biology and Biomedical Applications. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 8598–8654. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowsky R. Statistical Physics of Flexible Membranes. Phys. A 1993, 194, 114–127. 10.1016/0378-4371(93)90346-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T.; Sato Y. T.; Yoshikawa K.; Nagasaki T. Reversible Photoswitching in a Cell-Sized Vesicle. Langmuir 2005, 21, 7626–7628. 10.1021/la050885y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernpeintner C.; Frank J. A.; Urban P.; Roeske C. R.; Pritzl S. D.; Trauner D.; Lohmüller T. Light-Controlled Membrane Mechanics and Shape Transitions of Photoswitchable Lipid Vesicles. Langmuir 2017, 33, 4083–4089. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgart T.; Hess S. T.; Webb W. W. Imaging Coexisting Fluid Domains in Biomembrane Models Coupling Curvature and Line Tension. Nature 2003, 425, 821–824. 10.1038/nature02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer S.; Ganzinger K. A.; Franquelim H. G.; Schwille P. Synthetic Cell Division via Membrane-Transforming Molecular Assemblies. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 43. 10.1186/s12915-019-0665-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M.; Imai M.; Taniguchi T. Shape Deformation of Ternary Vesicles Coupled with Phase Separation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 148102 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev V. N.; Grafmüller A.; Bléger D.; Hecht S.; Kunstmann S.; Barbirz S.; Lipowsky R.; Dimova R. Area Increase and Budding in Giant Vesicles Triggered by Light: Behind the Scene. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert U. Configurations of Fluid Membranes and Vesicles. Adv. Phys. 1997, 46, 13–137. 10.1080/00018739700101488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osaki T.; Takeuchi S. Artificial Cell Membrane Systems for Biosensing Applications. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 216–231. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsi Z.; Preobraschenski J.; van den Bogaart G.; Riedel D.; Jahn R.; Woehler A. Single-Vesicle Imaging Reveals Different Transport Mechanisms between Glutamatergic and GABAergic Vesicles. Science 2016, 351, 981–984. 10.1126/science.aad8142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M.; Frohnmayer J. P.; Benk L. T.; Haller B.; Janiesch J.-W.; Heitkamp T.; Börsch M.; Lira R. B.; Dimova R.; Lipowsky R.; Bodenschatz E.; Baret J.-C.; Vidakovic-Koch T.; Sundmacher K.; Platzman I.; Spatz J. P. Sequential Bottom-up Assembly of Mechanically Stabilized Synthetic Cells by Microfluidics. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 89–96. 10.1038/nmat5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T.; Sugimoto R.; Vestergaard M. C.; Nagasaki T.; Takagi M. Membrane Disk and Sphere: Controllable Mesoscopic Structures for the Capture and Release of a Targeted Object. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10528–10532. 10.1021/ja103895b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara K.; Tamura M.; Shohda K. I.; Toyota T.; Suzuki K.; Sugawara T. Self-Reproduction of Supramolecular Giant Vesicles Combined with the Amplification of Encapsulated DNA. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 775–781. 10.1038/nchem.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y.; Imai M. Model System of Self-Reproducing Vesicles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 198101 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.198101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franquelim H. G.; Khmelinskaia A.; Sobczak J. P.; Dietz H.; Schwille P. Membrane Sculpting by Curved DNA Origami Scaffolds. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 811. 10.1038/s41467-018-03198-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. J.; Elisseeff J. H. Mimicking Biological Functionality with Polymers for Biomedical Applications. Nature 2016, 540, 386–394. 10.1038/nature21005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veshaguri S.; Christensen S. M.; Kemmer G. C.; Ghale G.; Møller M. P.; Lohr C.; Christensen A. L.; Justesen B. H.; Jørgensen I. L.; Schiller J.; Hatzakis N. S.; Grabe M.; Pomorski T. G.; Stamou D. Direct Observation of Proton Pumping by a Eukaryotic P-Type ATPase. Science 2016, 351, 1469–1473. 10.1126/science.aad6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirchi M.; Ziv G.; Riven I.; Cohen S. S.; Zohar N.; Barak Y.; Haran G. Single-Molecule Fluorescence Spectroscopy Maps the Folding Landscape of a Large Protein. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 493. 10.1038/ncomms1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande S.; Caspi Y.; Meijering A. E. C.; Dekker C. Octanol-Assisted Liposome Assembly on Chip. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10447. 10.1038/ncomms10447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiasen S.; Christensen S. M.; Fung J. J.; Rasmussen S. G. F.; Fay J. F.; Jorgensen S. K.; Veshaguri S.; Farrens D. L.; Kiskowski M.; Kobilka B.; Stamou D. Nanoscale High-Content Analysis Using Compositional Heterogeneities of Single Proteoliposomes. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 931–934. 10.1038/nmeth.3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morstein J.; Hill R. Z.; Novak J. E. A.; Feng S.; Norman D. D.; Donthamsetti P. C.; Frank J. A.; Harayama T.; Williams B. M.; Parrill A. L.; Tigyi G. J.; Riezman H.; Isacoff E. Y.; Bautista D. M.; Trauner D. Optical Control of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Formation and Function. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 623–631. 10.1038/s41589-019-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marguet M.; Bonduelle C.; Lecommandoux S. Multicompartmentalized Polymeric Systems: Towards Biomimetic Cellular Structure and Function. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 512–529. 10.1039/C2CS35312A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Alpizar G.; Kong L.; Vlieg R. C.; Rabe A.; Papadopoulou P.; Meijer M. S.; Bonnet S.; Vogel S.; van Noort J.; Kros A.; Campbell F. Light-Triggered Switching of Liposome Surface Charge Directs Delivery of Membrane Impermeable Payloads in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3638. 10.1038/s41467-020-17360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Bahreman A.; Daudey G.; Bussmann J.; Olsthoorn R. C. L.; Kros A. Drug Delivery via Cell Membrane Fusion Using Lipopeptide Modified Liposomes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 621–630. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walde P.; Umakoshi H.; Stano P.; Mavelli F. Emergent Properties Arising from the Assembly of Amphiphiles. Artificial Vesicle Membranes as Reaction Promoters and Regulators. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10177–10197. 10.1039/C4CC02812K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda W.; DeVane R.; Klein M. L. Computer Simulation Studies of Self-Assembling Macromolecules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012, 22, 175–186. 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher M. B.; Won Y.-Y.; Ege D. S.; Lee J. C.-M.; Bates F. S.; Discher D. E.; Hammer D. A. Polymersomes: Tough Vesicles Made from Diblock Copolymers. Science 1999, 284, 1143–1146. 10.1126/science.284.5417.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C. H.; Zeng J. Application of Polymersomes in Membrane Protein Study and Drug Discovery: Progress, Strategies, and Perspectives. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022, 8, e10350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostina N. Y.; Rahimi K.; Xiao Q.; Haraszti T.; Dedisch S.; Spatz J. P.; Schwaneberg U.; Michael L.; Klein M. L.; Percec V.; Möller M.; Rodriguez-Emmenegger C. Membrane-Mimetic Dendrimersomes Engulf Living Bacteria via Endocytosis. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 5732–5738. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b02349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewertsen R.; Neumann H.; Buchheim-Stehn B.; Herges R.; Näther C.; Renth F.; Temps F. Highly Efficient Reversible Z–E Photoisomerization of a Bridged Azobenzene with Visible Light through Resolved S1(nπ*) Absorption Bands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15594–15595. 10.1021/ja906547d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka T.; Kinbara K.; Aida T. Mechanical Twisting of a Guest by a Photoresponsive Host. Nature 2006, 404, 512–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima T.; Muraoka T.; Hamada T.; Morita M.; Takagi M.; Fukuoka H.; Inoue Y.; Sagawa T.; Ishijima A.; Omata Y.; Yamashita T.; Kinbara K. Micrometer-Size Vesicle Formation Triggered by UV Light. Langumuir 2014, 30, 7289–7295. 10.1021/la5008022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marget-Dana R. The Monolayer Technique: A Potent Tool for Studying the Interfacial Properties of Antimicrobial and Membrane-lytic Peptides and Their Interactions with Lipid Membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1462, 109–140. 10.1016/S0005-2736(99)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pécréaux J.; Döbereiner H.-G.; Prost J.; Joanny J.-F.; Bassereau P. Refined Contour Analysis of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Eur. Phys. J. 2004, 13, 277–290. 10.1140/epje/i2004-10001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimova R. Recent Developments in the Field of Bending Rigidity Measurements on Membranes. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 208, 225–234. 10.1016/j.cis.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. L.; Shinoda W. Large-Scale Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Self-Assembling Systems. Science 2008, 321, 798–800. 10.1126/science.1157834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe J. W.; Kay B. K. Filamentous Phage Display in the New Millennium. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 4056–4072. 10.1021/cr000261r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sojitra M.; Sarkar S.; Maghera J.; Rodrigues E.; Carpenter E. J.; Seth S.; Vinals D. F.; Bennett N. J.; Reddy R.; Khalil A.; Xue X.; Bell M. R.; Zheng R. B.; Zhang P.; Nycholat C.; Bailey J. J.; Ling C.-C.; Lowary T. L.; Paulson J. C.; Macauley M. S.; Derda R. Genetically Encoded Multivalent Liquid Glycan Array Displayed on M13 Bacteriophage. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 806–816. 10.1038/s41589-021-00788-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller-Salvia B.; Chin J. W. Efficient Phage Display with Multiple Distinct Non-Canonical Amino Acids Using Orthogonal Ribosome-Mediated Genetic Code Expansion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10844–10848. 10.1002/anie.201902658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. H.; Chung W. J.; McFarland S.; Lee S. W. Assembly of Bacteriophage into Functional Materials. Chem. Rec. 2013, 13, 43–59. 10.1002/tcr.201200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius F.; Kick B.; Behler K. L.; Honemann M. N.; Weuster-Botz D.; Dietz H. Biotechnological Mass Production of DNA Origami. Nature 2017, 552, 84–87. 10.1038/nature24650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson H. H.; Olshefsky A.; Sylvestre M.; Sellers D. L.; Pun S. H. Current State of in vivo Panning Technologies: Designing Specificity and Affinity into the Future of Drug Targeting. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2018, 130, 39–49. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J.; Dickerson M. T.; Owen N. K.; Landon L. A.; Deutscher S. L. Biodistribution of Filamentous Phage Peptide Libraries in Mice. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2004, 31, 121–129. 10.1023/B:MOLE.0000031459.14448.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parida B. K.; Garrastazu H.; Aden J. K.; Cap A. P.; McFaul S. J. Silica Microspheres Are Superior to Polystyrene for Microvesicle Analysis by Flow Cytometry. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 1000–1006. 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanga W.-J.; Shiuanb D. Plaque Reduction Test: An Alternative Method to Assess Specific Antibody Response to pIII-Displayed Peptide of Filamentous Phage M13. J. Immunol. Methods 2003, 276, 175–183. 10.1016/S0022-1759(03)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Huang H.; Zou H.; Tian X.; Hu J.; Qiu P.; Hu H.; Yan G. Liposome Encapsulation of Encolytic Virus M1 to Reduce Immunogenicity and Immune Clearance in vivo. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2019, 16, 779–785. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b01046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao A.; Huang G. L.; Igarashi K.; Hong T.; Liao S.; Stellacci F.; Matsumoto Y.; Yamasoba T.; Kataoka K.; Cabral H. Polymeric micelles Loading Proteins through Concurrent Ion Complexation and pH-Cleavable Covalent Bonding for in vivo Delivery. Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, 1900161. 10.1002/mabi.201900161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto Y.; Nomoto T.; Cabral H.; Matsumoto Y.; Watanabe S.; Christie R. J.; Miyata K.; Oba M.; Ogura T.; Yamasaki Y.; Nishiyama N.; Yamasoba T.; Kataoka K. Direct and Instantaneous Observation of Intravenously Injected Substances Using Intravital Confocal Micro-Videography. Biomed. Opt. Express 2010, 1, 1209–1216. 10.1364/BOE.1.001209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anraku Y.; Kishimura A.; Oba M.; Yamasaki Y.; Kataoka K. Spontaneous Formation of Nanosized Unilamellar Polyion Complex Vesicles with Tunable Size and Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1631–1636. 10.1021/ja908350e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z.; Han J.; Wan Y.; Zhang Z.; Sun X. Anionic Liposomes Enhance and Prolong Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Expression in Airway Epithelia in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2011, 8, 673–682. 10.1021/mp100404q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S. J.; Peng K.-W.; Bell J. C. Oncolytic Virotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 658–670. 10.1038/nbt.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. C.; Galanis E.; Kirn D. Clinical Trial Results with Oncolytic Virotherapy: A Century of Promise, a Decade of Progress. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2007, 4, 101–117. 10.1038/ncponc0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miest T. S.; Cattaneo R. New Viruses for Cancer Therapy: Meeting Clinical Needs. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 23–34. 10.1038/nrmicro3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.