Abstract

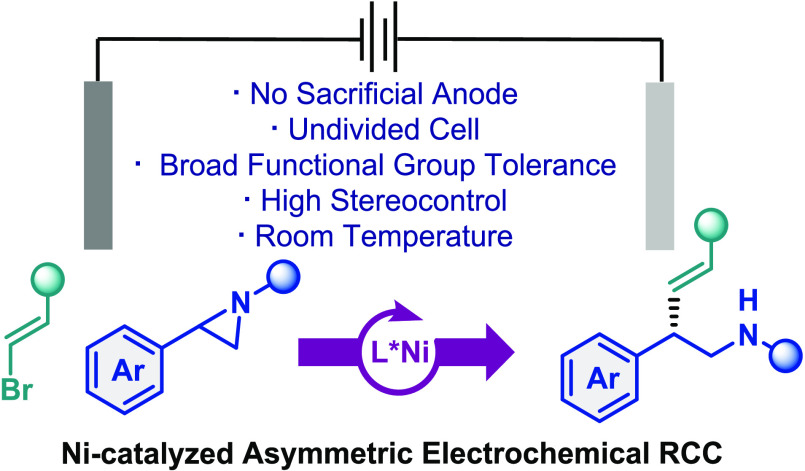

An electrochemically driven nickel-catalyzed enantioselective reductive cross-coupling of aryl aziridines with alkenyl bromides has been developed, affording enantioenriched β-aryl homoallylic amines with excellent E-selectivity. This electroreductive strategy proceeds in the absence of heterogeneous metal reductants and sacrificial anodes by employing constant current electrolysis in an undivided cell with triethylamine as a terminal reductant. The reaction features mild conditions, remarkable stereocontrol, broad substrate scope, and excellent functional group compatibility, which was illustrated by the late-stage functionalization of bioactive molecules. Mechanistic studies indicate that this transformation conforms with a stereoconvergent mechanism in which the aziridine is activated through a nucleophilic halide ring-opening process.

Introduction

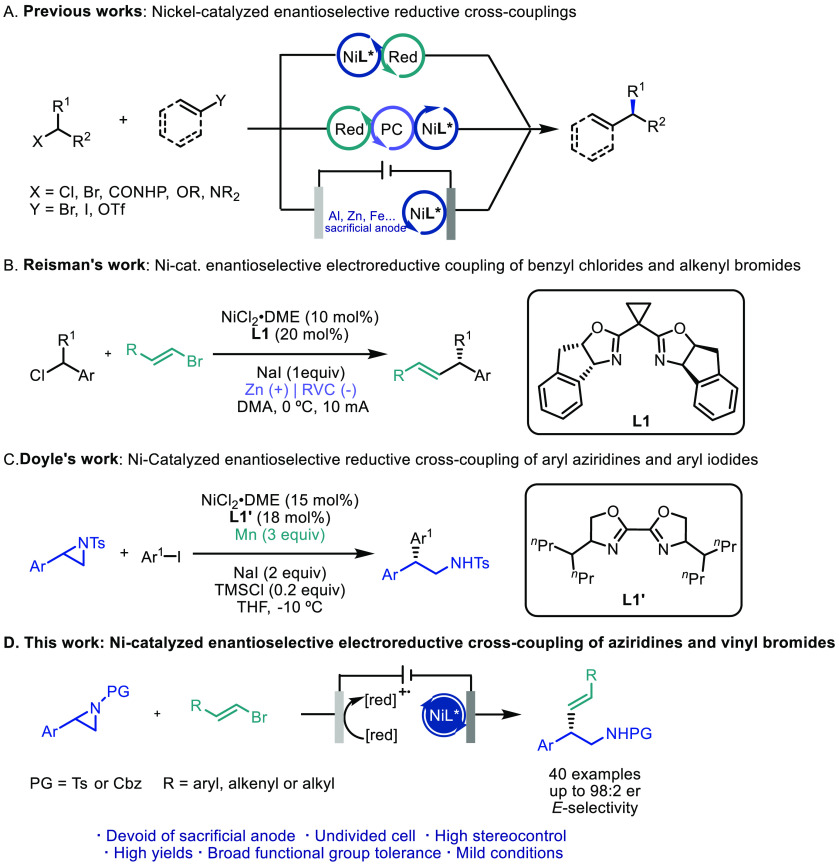

Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective cross-electrophile couplings represent a powerful strategy for the construction of stereogenic carbon centers.1 Compared to traditional asymmetric cross-coupling reactions,2 the direct coupling of two electrophiles precludes the preparation of sensitive organometallic species, thus enhancing both the operability and functional group compatibility of the overall process. A super stoichiometric amount of metal reductants such as manganese or zinc is typically required to turn over the nickel catalyst,3,4 which not only can lead to unpredictable results depending on stirring methods but also generates additional waste. Significant efforts have been undertaken to circumvent these challenges, including the use of organic reductants such as tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (TDAE) or bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2Pin2) among several others (Scheme 1A, top).5 Further, with the advent of photoredox/nickel dual catalysis,6 organic reducing reagents, including amines and Hantzsch esters (HEH), have also been successfully employed in asymmetric metallaphotoredox cross-electrophile couplings (Scheme 1A, middle).7

Scheme 1. Strategies for Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Cross-Electrophile Couplings.

In parallel to these developments, the past years have witnessed the renaissance of electrochemistry as a sustainable tool to replace chemical oxidants and reductants.8 The combination of cathodic reduction and nickel catalysis has proven to be an effective strategy for cross-couplings.9 Still, considerable limitations need to be addressed for these methodologies to attain their full potential. First and foremost, the use of metal sacrificial anodes (e.g., aluminum, zinc, iron, etc.) complicates the scalability of the processes. Second, the control of stereochemistry still represents a significant challenge10 and, despite a few examples,11 most nickel-catalyzed electrochemically mediated processes deliver the corresponding products in racemic form (Scheme 1A, bottom). Notably, Reisman’s group has reported a Ni-catalyzed enantioselective cross-coupling of benzylic chlorides and alkenyl bromides using zinc as a sacrificial anode (Scheme 1B).11c

Intrigued by these limitations, we set out to develop a nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive cross-coupling devoid of sacrificial anodes that would explore electrophiles beyond the well-studied C(sp2)–X and C(sp3)–X systems. Aziridines are versatile building blocks12 that have been successfully incorporated in Ni-catalyzed enantioselective cross-coupling processes.13 An elegant study from Doyle and co-workers reported the enantioselective reductive cross-coupling between aryl aziridines and aryl iodides by employing manganese as a stoichiometric reductant (Scheme 1C).13c Inspired by these precedents, we present the first example of a nickel-catalyzed asymmetric cross-electrophile coupling between aryl aziridines and alkenyl bromides, merging a constant current electrolysis process in a single cell with triethyl amine as a sustainable electron donor (Scheme 1D). Both the regio- and enantioselectivity of the reaction are controlled by a chiral bis(oxazoline) ligand. The obtained enantioenriched β-aryl homoallylic amines are not only important structural motifs found in pharmacologically and biologically active molecules14 but also useful synthetic intermediates to access a variety of valuable N-containing secondary metabolites.

Results and Discussion

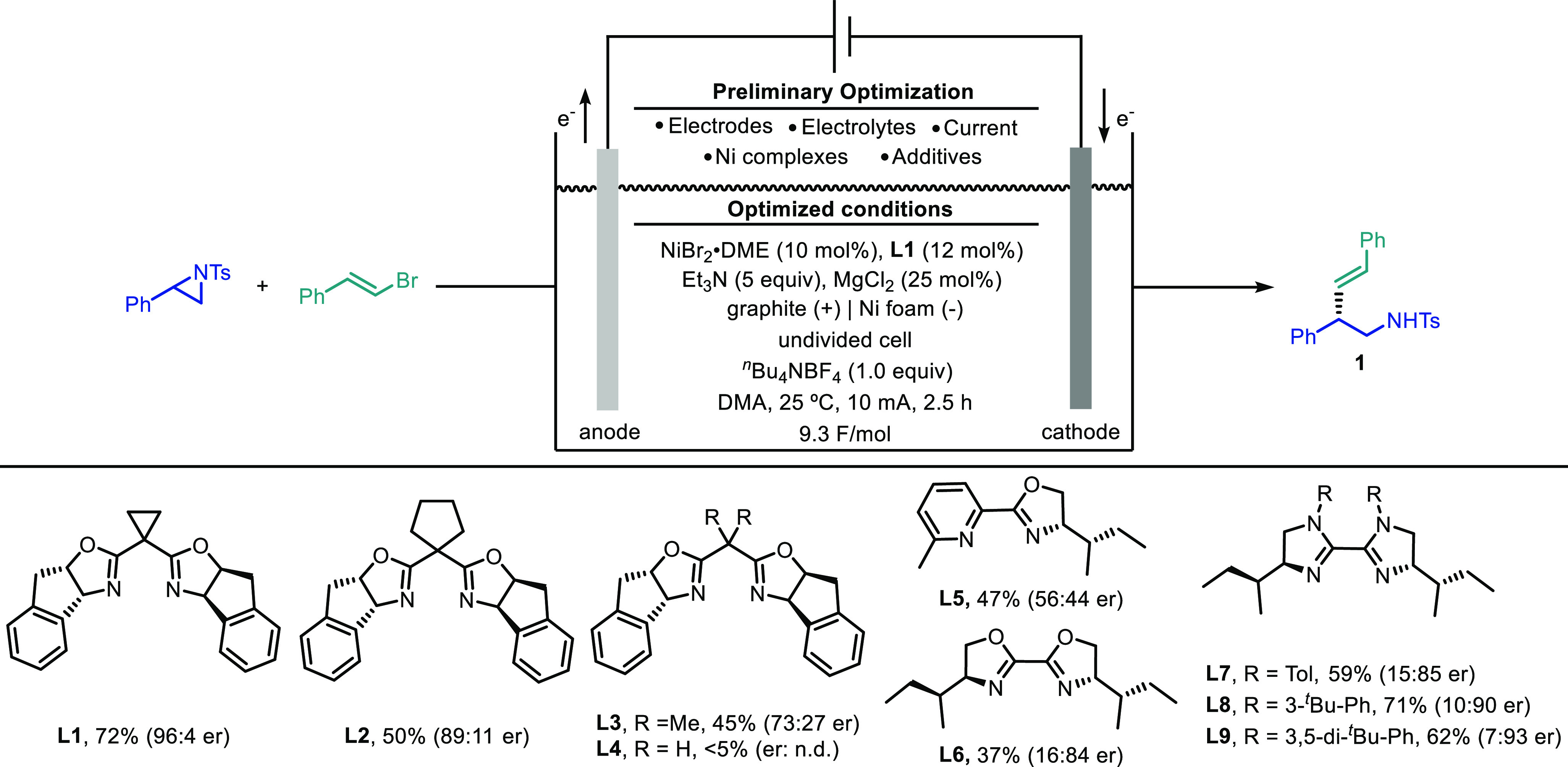

We began our investigations into this nickel-catalyzed asymmetric electroreductive cross-coupling with racemic 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine and β-bromostyrene as model reactants.15 After systematic evaluation of the reaction parameters (see the Tables S-1–S-9, Supporting Information), we were delighted to find that, in the presence of 10 mol % NiBr2·DME, 12 mol % chiral bis(oxazoline) L1, 25 mol % MgCl2, 5.0 equiv of Et3N, and 1.0 equiv of nBu4NBF4 in dimethylacetamide (DMA), the desired product (S,E)-N-(2,4-diphenylbut-3-en-1-yl)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide 1 could be obtained in 70% isolated yield. Gratifyingly, the reaction proceeded with excellent stereocontrol (96:4 er) by using a graphite anode and a nickel foam cathode in an undivided cell under 10 mA constant current electrolysis (Table 1, entry 1). The reaction showed excellent stereoselectivity, since only E-product 1 was obtained even when Z- or E/Z-mixed β-bromostyrenes were used as starting materials (see Table S-11 in the Supporting Information).3b,15,16 A screening of chiral indanyl-substituted bis(oxazoline) ligands with different central linkers revealed the cyclopropyl-substituted one (L1) as the best compromise between reactivity and enantioselectivity (L2–L4). In contrast, pyridine-oxazoline ligand L5 led to a low enantiomeric ratio, whereas chiral bioxazoline and bisimidazoline ligands (L6–L9) delivered the product in lower yields with moderate enantioselectivity. A slightly decreased yield was observed when the graphite anode was replaced with RVC foam or carbon felt (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). The choice of cathode material was essential: nickel or platinum plate cathodes resulted in near-complete failure of the reaction (Table 1, entry 4). This result could be attributed to the electrode surface area effect, as the large surface area of the Ni foam electrode might enhance the rate of surface reaction, thus increasing the overall efficiency of the system.17 Different nickel catalysts such as NiCl2·DME and NiBr2·diglyme afforded the product with lower yields but comparable er (Table 1, entries 5 and 6). Other electrolytes such as nBu4NPF6 or NaBF4 also provided good reactivity (Table 1, entries 7 and 8), while LiBF4 delivered 1 in lower yield (Table 1, entry 9). The reaction proceeded smoothly when the current was adjusted to 5 or 15 mA, albeit with lower yields (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). The yield decreased to 55% in the absence of MgCl2 (Table 1, entry 12), and MgBr2 had a weaker promoting effect compared with MgCl2 (Table 1, entry 13). Reducing the number of equivalents of Et3N or alkenyl bromide decreased the reaction efficiency (Table 1, entries 14 and 15). To our delight, a slight increase in yield was achieved when the reaction was performed on a 0.2 mmol scale (Table 1, entry 16). Control experiments indicated that the nickel source, the ligand, and the electrical current were all necessary for this transformation (Table 1, entry 17). It is worth noting that the use of stoichiometric amounts of Mn or Zn powder significantly reduced the yield and enantioselectivity of the process, likely as a result of unproductive pathways involving organometallic intermediates generated in the reaction media under these conditions (Table 1, entries 18 and 19).

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditionsa.

| entry | deviation from standard conditions | 1 yield (%)b | erc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 72 (70) | 96:4 |

| 2 | RVC (+) instead of graphite (+) | 63 | 96:4 |

| 3 | carbon felt (+) instead of graphite (+) | 65 | 96:4 |

| 4 | Ni (−) or Pt (−) instead of Ni foam (−) | <5 | n.d.f |

| 5 | NiCl2·DME instead of NiBr2·DME | 53 | 95:5 |

| 6 | NiBr2·diglyme instead of NiBr2·DME | 50 | 96:4 |

| 7 | nBu4NPF6 instead of nBu4NBF4 | 66 | 96:4 |

| 8 | NaBF4 instead of nBu4NBF4 | 70 | 95:5 |

| 9 | LiBF4 instead of nBu4NBF4 | 46 | 95:5 |

| 10 | 5 mA, 5 h instead of 10 mA, 2.5 h | 55 | 96:4 |

| 11 | 15 mA, 1.67 h instead of 10 mA, 2.5 h | 60 | 96:4 |

| 12 | Without MgCl2 | 55 | 96:4 |

| 13 | MgBr2 instead of MgCl2 | 61 | 96:4 |

| 14 | 3 equiv Et3N instead of 5 equiv Et3N | 53 | 96:4 |

| 15 | 2 equiv β-bromostyrene was used | 59 | 96:4 |

| 16d | 0.2 mmol reaction scale | 75 (73) | 96:4 |

| 17 | w/o electric current, Ni or L1 | 0 | n.d. |

| 18e | 3 equiv Mn instead of current and Et3N | 20 | 76:24 |

| 19e | 3 equiv Zn instead of current and Et3N | 25 | 80:20 |

Standard reaction conditions: graphite anode, nickel foam cathode, 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), β-bromostyrene (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv), nBu4NBF4 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Et3N (0.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv), MgCl2 (0.025 mmol, 25 mol %), NiBr2·DME (0.01 mmol, 10 mol %), L1 (0.012 mmol, 12 mol %), DMA (3.0 mL), constant current = 10 mA, undivided cell, N2, 2.5 h, 25 °C.

Yields were determined by 1H NMR using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as the internal standard; isolated yields after column chromatography are shown in brackets.

The enantiomeric ratios (er) were determined by chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Reaction time = 5 h.

Reaction time = 24 h.

n.d. = not determined.

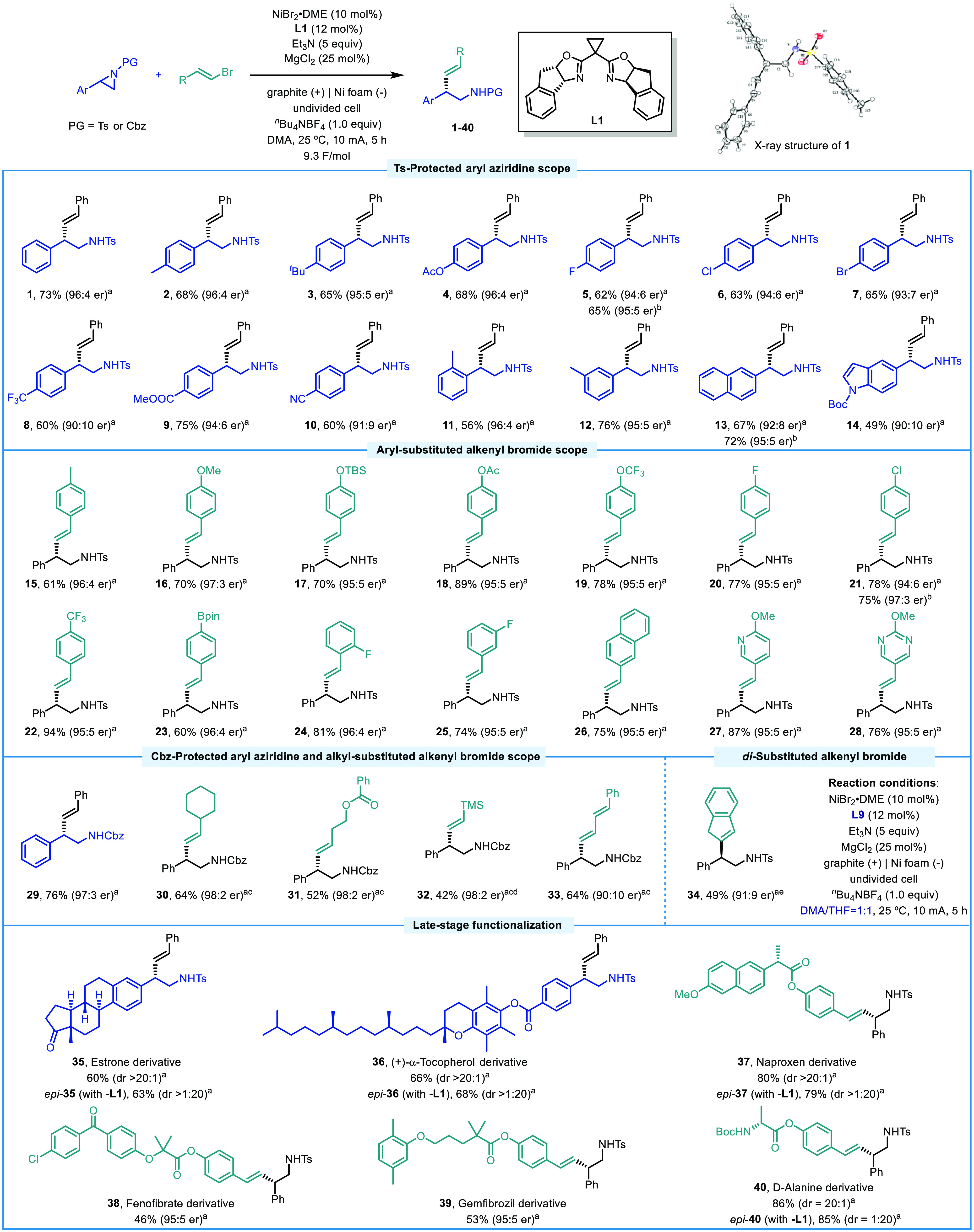

With the optimized conditions in hand, we sought to examine the generality of this transformation (Scheme 2). The absolute stereochemistry of compound 1 was unambiguously confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis, and the configuration of all other products was assigned by analogy.15 A wide range of 2-aryl-substituted N-tosyl-protected aziridines bearing electron-donating groups (−Me, −tBu, −OAc), halogens (−F, −Cl, −Br), and electron-withdrawing groups (−CF3, −COOMe, −CN) at the para-position of the phenyl ring readily underwent the cross-coupling with β-bromostyrene to form β-aryl E-configured homoallylic sulfonamides in moderate to good yields with high enantioselectivities (2–10). 2-(o-Tolyl)- and 2-(m-tolyl)-N-tosylaziridines were also well tolerated, demonstrating that increased steric hindrance has little effect on the reaction efficiency and enantioselectivity (11 and 12). Further, 2-naphthyl- and 5-indolyl-substituted aziridines also proved to be competent coupling partners (13 and 14). In some cases, the use of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) as the reductant improved both the yields and enantioselectivities as in the case of products 5 and 13 (see Table S12 in the Supporting Information for additional information).

Scheme 2. Substrate Scope.

Reaction conditions: See Table 1, entry 16. Isolated yields after column chromatography. Enantiomeric ratios (er) were determined by chiral HPLC.

DIPEA instead of Et3N.

20 mol % NiBr2·DME and 24 mol % L1.

Alkenyl bromide (5 equiv).

L9 was used as the ligand, and a 1:1 mixture of DMA/tetrahydrofuran (THF) was used as the solvent.

Different alkenyl bromide partners were explored next. Styrenyl bromides bearing a variety of functional groups, such as methyl (15), methoxy (16), (tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy (17), acetoxy (18), trifluoromethoxy (19), fluoro (20), chloro (21), trifluoromethyl (22), and pinacol boronate (23), turned out to be compatible with the established protocol delivering the corresponding products in good yields and high enantiomeric ratios (60–94% yield, 95:5–97:3 er). ortho- and meta-Fluorophenyl-substituted alkenyl bromides could also participate in the reaction efficiently (24 and 25). Notably, the tolerance to halogen and pinacol boronate functional groups opens the possibility of subsequent derivatization of the β-aryl homoallylic amines. Alkenyl bromides bearing naphthalene (26), pyridine (27), and pyrimidine (28) rings were also successfully converted to the desired products with high enantioselectivity, thus highlighting the potential of this strategy in the synthesis of medicinal chemistry-relevant compounds.

We were pleased to find that benzyloxycarbonyl (Cbz)-protected aziridines also reacted smoothly with β-bromostyrene under the standard reaction conditions, furnishing product 29 in 76% yield and 97:3 er. This result further emphasizes the advantage of this electrochemical reduction protocol, as this type of compound was inaccessible with previous Ni-catalyzed aziridine asymmetric cross-electrophile couplings.13c In addition to styrenyl bromides, β-alkyl substituted vinyl bromides (30 and 31), bromovinyl silane (32), and conjugated dienyl bromide (33) turned out to be suitable reaction partners delivering the corresponding Cbz-protected products with high to excellent enantioselectivities (up to 98:2 er). Remarkably, 2-bromo-1H-indene, a cyclic di-substituted alkenyl bromide, which is typically a challenging substrate in asymmetric alkenylations,3b,3e,11c was a viable partner delivering 34 under modified reaction conditions using L9 as the ligand in a DMA/THF binary solvent system.

The synthetic potential of this asymmetric electroreductive cross-coupling was further demonstrated through the late-stage functionalization of structurally diverse natural products and pharmaceutical agents. Specifically, aziridines derived from estrone (35) and (+)-α-tocopherol (36) could be readily incorporated into this protocol with excellent diastereocontrol. In addition, alkenyl bromides resembling derivatives of naproxen, fenofibrate, gemfibrozil, and d-alanine could all furnish chiral homoallylic amines 37–40 (epi-35, epi-36, epi-37, epi-40 were obtained by using ent-ligand-L1) in moderate to good yields with high levels of diastereocontrol.

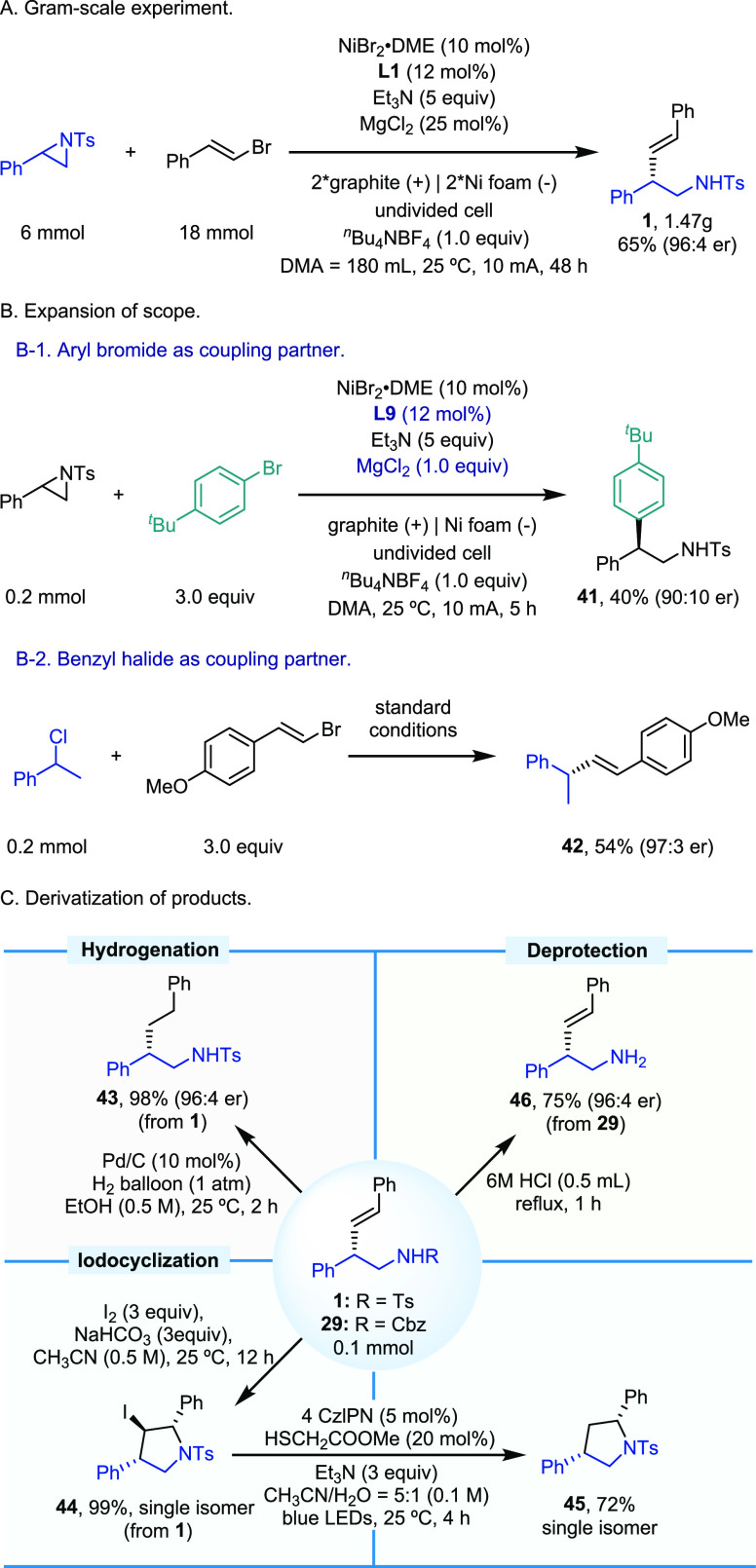

The practicality of this methodology could be demonstrated in multigram-scale experiments (Scheme 3A). The constant current electrolysis of 6 mmol of 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine with β-bromostyrene produced the desired product 1 in 65% isolated yield and 96:4 er. Moreover, our protocol can be extended to other coupling partners (Scheme 3B). The reductive cross-coupling of 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine with 1-bromo-4-(tert-butyl)benzene was achieved under modified reaction conditions (L9 as the ligand and 1 equiv of MgCl2 as the additive) furnishing β-aryl sulfonamide 41 in 40% yield and 90:10 er. Further, the coupling of (1-chloroethyl)benzene and (E)-1-(2-bromovinyl)-4-methoxybenzene under the standard reaction conditions delivered the desired product 42 in 54% yield and 97:3 er. Derivatization of the chiral homoallylic amine products could also be successfully accomplished (Scheme 3C). The palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation of 1 delivered the corresponding chiral β-branched alkylamine 43 with excellent stereofidelity. In the presence of I2 and NaHCO3, enantioenriched iodosubstituted pyrrolidine (44), containing three contiguous chiral centers, could be obtained in near-quantitative yield by diastereoselective iodocyclization of 1. A photoredox-catalyzed dehalogenation of 44 furnished chiral 2,4-disubstituted pyrrolidine (45) by using Et3N as the halogen-atom transfer agent and methyl thioglycolate–H2O as the hydrogen atom donor. Finally, deprotection of the N-benzyloxycarbonyl group in 29 was successfully accomplished by treatment with 6 M HCl under reflux to deliver chiral homoallylic primary amine (46).

Scheme 3. Synthetic Applications.

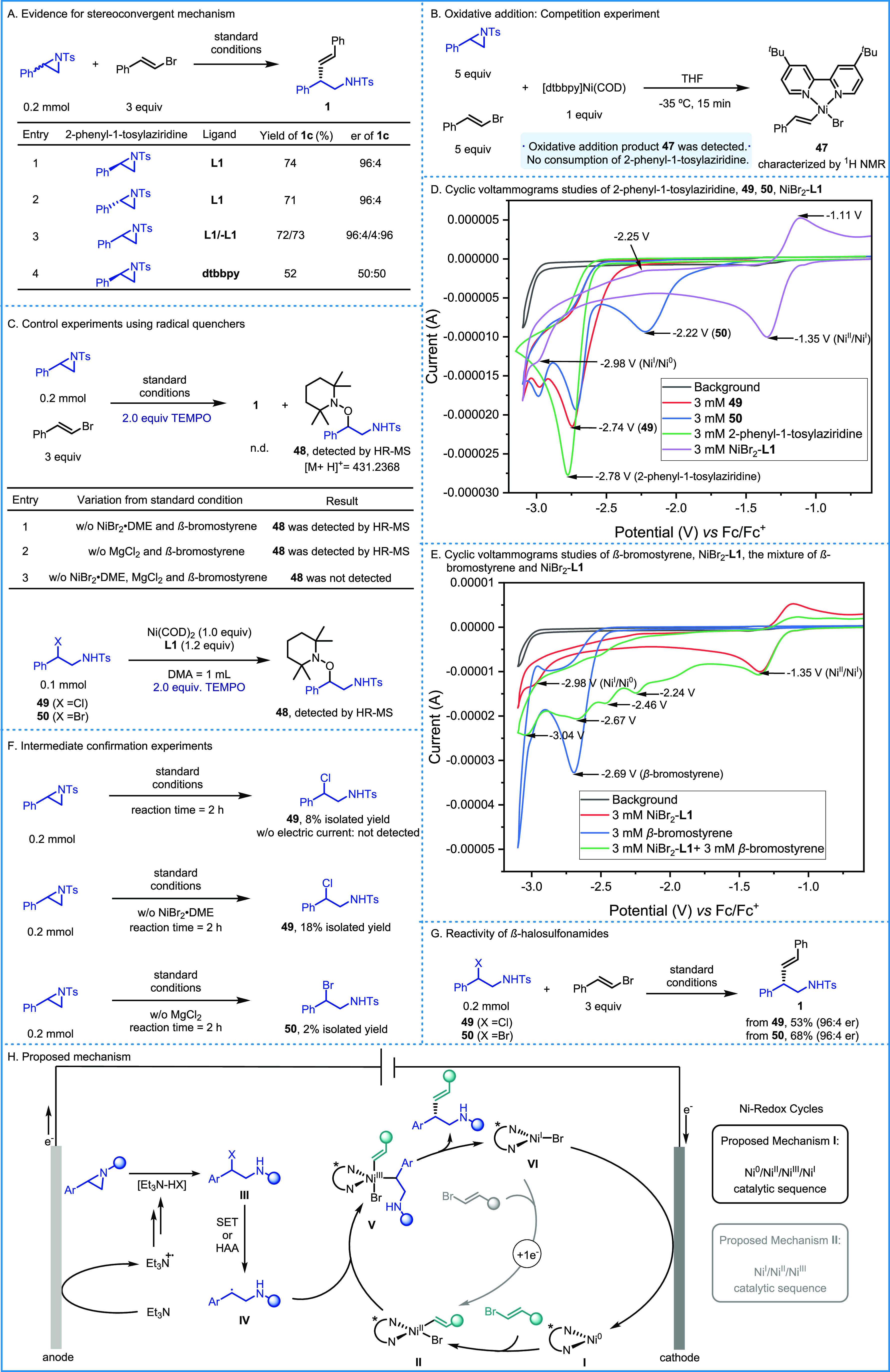

To acquire further insights into the mechanism of this transformation, several control experiments were designed.15 Both R and S enantiomers of 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine delivered the same enantioenriched product 1 under standard reaction conditions. The major enantiomer of the product was dictated by the stereochemistry of the ligand, demonstrating the stereoconvergent nature of this transformation (Scheme 4A, entries 1–3). The activation pathway for aziridine was investigated next.13 A competition experiment was designed featuring β-bromostyrene (5.0 equiv), 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine (5.0 equiv), and 1 equiv of [dtbbpy]Ni0(COD). The oxidative addition product of β-bromostyrene to Ni(0), complex 47, was clearly detected by 1H NMR15 with no detectable consumption of 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine, which indicates that the activation of aziridines through oxidative addition to Ni(0) is not a favorable process under the reaction conditions (Scheme 4B). A direct single-electron reductive activation was also considered. As shown in Scheme 4A, entry 4, the reaction of (R)-N-p-tolylsulfonyl-2-phenylaziridine in the presence of 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine ligand furnished the corresponding product 1 in racemic form, thus hinting toward the intermediacy of a benzyl radical derived from aziridine under the applied conditions. Further investigations were carried out involving radical quenchers (Scheme 4C, top). The reaction was completely suppressed by adding 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO, 2.0 equiv), and the TEMPO-benzyl adduct 48 could be detected by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) in the mixture. Adduct 48 could still be detected when the reaction was performed in the absence of MgCl2 or NiBr2·DME. However, when neither MgCl2 nor NiBr2·DME was present, 48 could not be found in the reaction mixture. These results deem a direct single-electron reductive activation of aziridines unlikely. Still, the participation of benzyl radicals in the reaction could be justified by the formation and subsequent reduction of β-halo-sulfonamides under the utilized conditions. Reduction of the β-halo-sulfonamides could occur either directly at the cathode or by in situ-generated low-valent nickel species. The former possibility is supported by the fact that the TEMPO adduct 48 can be formed in the absence of the nickel catalyst. On the other hand, the reaction of β-halo-sulfonamides with stoichiometric Ni(COD)2/L1 also delivered the TEMPO adduct 48, thus indicating that Ni0L1 species can also reduce the β-halo-sulfonamide to the benzyl radical (Scheme 4C, bottom). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) studies are also consistent with these results (Scheme 4D). The reductive potential of NiI/Ni0 (E1/2 = −2.62 V vs Fc/Fc+ in DMA, reductive peak observed at −2.98 V) is more negative than those of β-chloro-sulfonamide 49 (E1/2 = −2.61 V vs Fc/Fc+ in DMA, reductive peak observed at −2.74 V) and β-bromo-sulfonamide 50 (E1/2 = −2.06 V vs Fc/Fc+ in DMA, reductive peak observed at −2.22 V), indicating that the putative β-halo-sulfonamide intermediates can indeed be reduced by Ni0L1 species. These species are also more easily reduced than 2-phenyl-1-tosylaziridine (E1/2 = −2.70 V vs Fc/Fc+ in DMA, reductive peak observed at −2.78 V) so that, once formed, one would expect them to be preferentially reduced over the corresponding starting material. In contrast to previous reports,12f,18 the NiIBrL1 (E1/2 (NiII/NiI) = −1.23 V vs Fc/Fc+ in DMA, reductive peak observed at −1.35 V) is not competent for reducing the secondary halogens in the present reaction system. In order to unravel whether Ni(I) can undergo oxidative addition with alkenyl bromide, the cyclic voltammetry of NiBr2-L1 was carried out in the presence of 1.0 equiv of β-bromostyrene (Scheme 4E). Some new reductive peaks appeared, suggesting that the oxidative addition of alkenyl bromide to Ni(I) is also a feasible process.

Scheme 4. Mechanistic Studies and Proposed Mechanism.

To gain additional insights into the participation of putative halogenated intermediates, the reaction was analyzed by MS (Scheme 4F). Interestingly, β-chloro-sulfonamide 49 can be isolated in 8% yield after 2 h of electrolysis in the absence of alkenyl bromide and in 18% yield when both NiBr2·DME and alkenyl bromide are removed from the reaction mixture. In sharp contrast, 49 was not detected in the absence of an electric current. These results hint toward a potential activation via nucleophilic halide ring-opening of the aziridine by in situ-formed R3N–HX (X = Cl or Br), although neither MgCl2 nor NiBr2·DME seem to be essential to this activation process. Since the reaction can also proceed in the absence of the MgCl2 additive, bromides are likely implicated in the nucleophilic ring opening process of the phenyl aziridine partners used in this transformation. As expected, we observed the formation of β-bromo-sulfonamide in the absence of MgCl2, but it is not detected under the standard conditions as a result of its facile reduction compared to the corresponding chloride under the utilized electrochemical conditions (Scheme 4F). Last, we aimed to demonstrate whether or not the proposed β-halo-sulfonamides can indeed behave as productive intermediates. When β-chloro-sulfonamide (49) and β-bromo-sulfonamide (50) were subjected to the standard reaction conditions, the cross-coupled product 1 was obtained in 53 and 68% yield, respectively. The enantiomeric ratio was identical to that obtained with the aziridine precursor (Scheme 4G). Further, experiments combining different catalytic amounts of 49 or 50 (0.1–0.3 equiv) with 4-(1-tosylaziridin-2-yl)phenyl acetate (0.9–0.7 equiv) under the reaction conditions generated products 1 and 4 in consistent high yields with respect to the corresponding precursors (see Section 7-6 in the Supporting Information).15 These results indeed support the idea of β-halo-sulfonamides as productive intermediates in the present transformation.

Based on the abovementioned investigations, two plausible mechanisms for this nickel-catalyzed electrochemical reductive cross-coupling can be proposed in Scheme 4H. The first one involves a Ni0/NiII/NiIII/NiI catalytic sequence, wherein the oxidative addition of alkenyl bromide to Ni(0) I generates Ni(II) species II. In parallel, in situ-generated R3N–HX (X = Cl or Br) can mediate the nucleophilic halide ring-opening of the aryl aziridine delivering β-halo-sulfonamide intermediate III. Single-electron transfer (SET, through cathodic reduction or with Ni0L1) or halogen atom abstraction (HAA)19 can furnish the corresponding benzyl radical IV, which can then recombine with nickel-complex II to form Ni(III) species V. Reductive elimination produces the observed cross-coupled product, and the resulting Ni(I) species VI can be reduced to regenerate the Ni(0) at the cathode. This process is supported by the result that the operating potential of the cathode (−3.05 V vs Fc/Fc+) is more negative than that of NiI/Ni0 (E1/2 (NiI/Ni0) = −2.62 V vs Fc/Fc+) so that the cathode is competent to reduce Ni(I) species VI to Ni(0) I (see Section 7-8 in the Supporting Information).15 Concomitant anodic oxidation of Et3N to its radical cation is key to bypass the need for a sacrificial anode (Scheme 4H, black). The second pathway involves a NiI/NiII/NiIII catalytic sequence.11e As shown in Scheme 4E, the Ni(II)Br2 species can be reduced to Ni(I)Br VI at the cathode, and the subsequent oxidative addition of alkenyl bromide can directly deliver the key alkenyl-Ni(II) complex II under the reducing reaction conditions (Scheme 4H, gray).

Conclusions

In summary, the first example of a nickel-catalyzed enantioselective electrochemical reductive cross-coupling between aryl aziridines and alkenyl bromides using triethylamine as the terminal reductant is presented here. Active metal electrodes are not required as sacrificial anodes, making this method more atom-economical and scalable for synthetic applications. The transformation exhibits a broad substrate scope and excellent functional group tolerance, allowing efficient access to chiral β-aryl homoallylic amines with high enantioselectivities and excellent E-stereoselectivity. The synthetic potential of this methodology has been demonstrated by its successful application to pharmacologically relevant substrates, scalability, and subsequent derivatization of the products. Mechanistic studies indicate that this transformation is consistent with a stereoconvergent mechanism in which β-halo-sulfonamides generated through nucleophilic halide ring-opening are likely intermediates along the reaction pathway. We believe that the lessons obtained here from combining electro-reduction with organic reductants will inspire the development of enantioselective electrochemical reductive cross-coupling reactions in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. A. Linden for the X-ray diffraction analysis of 1. This publication was created as part of NCCR Catalysis, a National Centre of Competence in Research funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF es 200021_184986/1) is also acknowledged for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12869.

Experimental procedures, characterization data, NMR spectra, HPLC traces, and crystallographic data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Lucas E. L.; Jarvo E. R. Stereospecific and stereoconvergent cross-couplings between alkyl electrophiles. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0065 10.1038/s41570-017-0065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Moran J.; Richmond E. Recent Advances in Nickel Catalysis Enabled by Stoichiometric Metallic Reducing Agents. Synthesis 2017, 50, 499–513. 10.1055/s-0036-1591853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Poremba K. E.; Dibrell S. E.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Cross-Coupling Reactions. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8237–8246. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Tasker S. Z.; Standley E. A.; Jamison T. F. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang X.; Dai Y.; Gong H. Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Couplings. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 43 10.1007/s41061-016-0042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Weix D. J. Methods and Mechanisms for Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Csp(2) Halides with Alkyl Electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1767–1775. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Goldfogel M. J.; Huang L.; Weix D. J.. Cross-Electrophile Coupling: Principles and New Reactions. In Nickel Catalysis in Organic Synthesis; Ogoshi S., Ed.; Wiley, 2020; pp 183–222. [Google Scholar]

- a Cheng L. J.; Mankad N. P. C-C and C-X coupling reactions of unactivated alkyl electrophiles using copper catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8036–8064. 10.1039/D0CS00316F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cherney A. H.; Kadunce N. T.; Reisman S. E. Enantioselective and Enantiospecific Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organometallic Reagents To Construct C-C Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9587–9652. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Fu G. C. Transition-Metal Catalysis of Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions: A Radical Alternative to SN1 and SN2 Processes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 692–700. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Iwasaki T.; Kambe N. Ni-Catalyzed C-C Couplings Using Alkyl Electrophiles. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 66 10.1007/s41061-016-0067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Jana R.; Pathak T. P.; Sigman M. S. Advances in transition metal (Pd, Ni, Fe)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions using alkyl-organometallics as reaction partners. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1417–1492. 10.1021/cr100327p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Rudolph A.; Lautens M. Secondary alkyl halides in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2656–2670. 10.1002/anie.200803611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cherney A. H.; Kadunce N. T.; Reisman S. E. Catalytic asymmetric reductive acyl cross-coupling: synthesis of enantioenriched acyclic alpha,alpha-disubstituted ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7442–7445. 10.1021/ja402922w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cherney A. H.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive cross-coupling between vinyl and benzyl electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14365–14368. 10.1021/ja508067c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kadunce N. T.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling between Heteroaryl Iodides and alpha-Chloronitriles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10480–10483. 10.1021/jacs.5b06466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Poremba K. E.; Kadunce N. T.; Suzuki N.; Cherney A. H.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling To Access 1,1-Diarylalkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5684–5687. 10.1021/jacs.7b01705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Hofstra J. L.; Cherney A. H.; Ordner C. M.; Reisman S. E. Synthesis of Enantioenriched Allylic Silanes via Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 139–142. 10.1021/jacs.7b11707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f DeLano T. J.; Dibrell S. E.; Lacker C. R.; Pancoast A. R.; Poremba K. E.; Cleary L.; Sigman M. S.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive cross-coupling of alpha-chloroesters with (hetero)aryl iodides. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 7758–7762. 10.1039/D1SC00822F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Min Y.; Sheng J.; Yu J. L.; Ni S. X.; Ma G.; Gong H.; Wang X. S. Diverse Synthesis of Chiral Trifluoromethylated Alkanes via Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling Fluoroalkylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 9947–9952. 10.1002/anie.202101076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Sun D.; Ma G.; Zhao X.; Lei C.; Gong H. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive arylation of alpha-chlorosulfones with aryl halides. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 5253–5258. 10.1039/D1SC00283J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Banerjee A.; Yamamoto H. Nickel Catalyzed Regio-, Diastereo-, and Enantioselective Cross-Coupling of 3,4-Epoxyalcohol with Aryl Iodides. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4363–4366. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Zhao Y.; Weix D. J. Enantioselective cross-coupling of meso-epoxides with aryl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3237–3240. 10.1021/jacs.5b01909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang K.; Ding Z.; Zhou Z.; Kong W. Ni-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Diarylation of Activated Alkenes by Domino Cyclization/Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12364–12368. 10.1021/jacs.8b08190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jin Y.; Wang C. Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Arylalkylation of Unactivated Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6722–6726. 10.1002/anie.201901067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tian Z. X.; Qiao J. B.; Xu G. L.; Pang X.; Qi L.; Ma W. Y.; Zhao Z. Z.; Duan J.; Du Y. F.; Su P.; Liu X. Y.; Shu X. Z. Highly Enantioselective Cross-Electrophile Aryl-Alkenylation of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7637–7643. 10.1021/jacs.9b03863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d He J.; Xue Y.; Han B.; Zhang C.; Wang Y.; Zhu S. Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive 1,2-Carboamination of Unactivated Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2328–2332. 10.1002/anie.201913743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Anthony D.; Lin Q.; Baudet J.; Diao T. Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Diarylation of Vinylarenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3198–3202. 10.1002/anie.201900228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Tu H. Y.; Wang F.; Huo L.; Li Y.; Zhu S.; Zhao X.; Li H.; Qing F. L.; Chu L. Enantioselective Three-Component Fluoroalkylarylation of Unactivated Olefins through Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9604–9611. 10.1021/jacs.0c03708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Yang T.; Chen X.; Rao W.; Koh M. J. Broadly Applicable Directed Catalytic Reductive Difunctionalization of Alkenyl Carbonyl Compounds. Chem 2020, 6, 738–751. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Anka-Lufford L. L.; Huihui K. M. M.; Gower N. J.; Ackerman L. K. G.; Weix D. J. Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Coupling with Organic Reductants in Non-Amide Solvents. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 11564–11567. 10.1002/chem.201602668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Suzuki N.; Hofstra J. L.; Poremba K. E.; Reisman S. E. Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Cross-Coupling of N-Hydroxyphthalimide Esters with Vinyl Bromides. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2150–2153. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wei X.; Shu W.; Garcia-Dominguez A.; Merino E.; Nevado C. Asymmetric Ni-Catalyzed Radical Relayed Reductive Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13515–13522. 10.1021/jacs.0c05254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Charboneau D. J.; Hazari N.; Huang H.; Uehling M. R.; Zultanski S. L. Homogeneous Organic Electron Donors in Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Transformations. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 7589–7609. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhu Z.; Lin L.; Xiao J.; Shi Z. Nickel-Catalyzed Stereo- and Enantioselective Cross-Coupling of gem-Difluoroalkenes with Carbon Electrophiles by C–F Bond Activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202113209 10.1002/anie.202113209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lipp A.; Badir S. O.; Molander G. A. Stereoinduction in Metallaphotoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 1714–1726. 10.1002/anie.202007668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zuo Z.; Cong H.; Li W.; Choi J.; Fu G. C.; MacMillan D. W. Enantioselective Decarboxylative Arylation of alpha-Amino Acids via the Merger of Photoredox and Nickel Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1832–1835. 10.1021/jacs.5b13211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cheng X.; Lu H.; Lu Z. Enantioselective benzylic C-H arylation via photoredox and nickel dual catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3549 10.1038/s41467-019-11392-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Shu X.; Huan L.; Huang Q.; Huo H. Direct Enantioselective C(sp(3))-H Acylation for the Synthesis of alpha-Amino Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 19058–19064. 10.1021/jacs.0c10471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Rand A. W.; Yin H.; Xu L.; Giacoboni J.; Martin-Montero R.; Romano C.; Montgomery J.; Ruben M. Dual Catalytic Platform for Enabling sp3 α C–H Arylation and Alkylation of Benzamides. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 4671–4676. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Stache E. E.; Rovis T.; Doyle A. G. Dual Nickel- and Photoredox-Catalyzed Enantioselective Desymmetrization of Cyclic meso-Anhydrides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3679–3683. 10.1002/anie.201700097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Guo L.; Yuan M.; Zhang Y.; Wang F.; Zhu S.; Gutierrez O.; Chu L. General Method for Enantioselective Three-Component Carboarylation of Alkenes Enabled by Visible-Light Dual Photoredox/Nickel Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 20390–20399. 10.1021/jacs.0c08823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gandolfo E.; Tang X.; Raha Roy S.; Melchiorre P. Photochemical Asymmetric Nickel-Catalyzed Acyl Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16854–16858. 10.1002/anie.201910168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guan H.; Zhang Q.; Walsh P. J.; Mao J. Nickel/Photoredox-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling of Racemic alpha-Chloro Esters with Aryl Iodides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5172–5177. 10.1002/anie.201914175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lau S. H.; Borden M. A.; Steiman T. J.; Wang L. S.; Parasram M.; Doyle A. G. Ni/Photoredox-Catalyzed Enantioselective Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Styrene Oxides with Aryl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 15873–15881. 10.1021/jacs.1c08105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zheng P.; Zhou P.; Wang D.; Xu W.; Wang H.; Xu T. Dual Ni/photoredox-catalyzed asymmetric cross-coupling to access chiral benzylic boronic esters. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1646 10.1038/s41467-021-21947-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang H.; Zheng P.; Wu X.; Li Y.; Xu T. Modular and Facile Access to Chiral alpha-Aryl Phosphates via Dual Nickel- and Photoredox-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3989–3997. 10.1021/jacs.1c12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Qian P.; Guan H.; Wang Y. E.; Lu Q.; Zhang F.; Xiong D.; Walsh P. J.; Mao J. Catalytic enantioselective reductive domino alkyl arylation of acrylates via nickel/photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6613 10.1038/s41467-021-26794-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yan M.; Kawamata Y.; Baran P. S. Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13230–13319. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Little R. D.; Moeller K. D. Introduction: Electrochemistry: Technology, Synthesis, Energy, and Materials. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4483–4484. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wiebe A.; Gieshoff T.; Mohle S.; Rodrigo E.; Zirbes M.; Waldvogel S. R. Electrifying Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5594–5619. 10.1002/anie.201711060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ma C.; Fang P.; Liu Z.; Xu S.; Xu K.; Cheng X.; Lei A.; Xu H.; Zeng C.; Mei T. Recent advances in organic electrosynthesis employing transition metal complexes as electrocatalysts. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 2412–2429. 10.1016/j.scib.2021.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Novaes L. F. T.; Liu J.; Shen Y.; Lu L.; Meinhardt J. M.; Lin S. Electrocatalysis as an enabling technology for organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 7941–8002. 10.1039/D1CS00223F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Zhu C.; Ang N. W. J.; Meyer T. H.; Qiu Y.; Ackermann L. Organic Electrochemistry: Molecular Syntheses with Potential. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 415–431. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sengmany S.; Rahil R.; Le Gall E.; Léonel E. Nickel-Catalyzed Electrochemical Reductive Homocouplings of Aryl and Heteroaryl Halides: A Useful Route to Symmetrical Biaryls. Synthesis 2017, 50, 146–154. 10.1055/s-0036-1589100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Perkins R. J.; Pedro D. J.; Hansen E. C. Electrochemical Nickel Catalysis for Sp(2)-Sp(3) Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reactions of Unactivated Alkyl Halides. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3755–3758. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li H.; Breen C. P.; Seo H.; Jamison T. F.; Fang Y. Q.; Bio M. M. Ni-Catalyzed Electrochemical Decarboxylative C-C Couplings in Batch and Continuous Flow. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1338–1341. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Koyanagi T.; Herath A.; Chong A.; Ratnikov M.; Valiere A.; Chang J.; Molteni V.; Loren J. One-Pot Electrochemical Nickel-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Sp(2)-Sp(3) Cross-Coupling. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 816–820. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b04090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kumar G. S.; Peshkov A.; Brzozowska A.; Nikolaienko P.; Zhu C.; Rueping M. Nickel-Catalyzed Chain-Walking Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Alkyl and Aryl Halides and Olefin Hydroarylation Enabled by Electrochemical Reduction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6513–6519. 10.1002/anie.201915418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Jiao K. J.; Liu D.; Ma H. X.; Qiu H.; Fang P.; Mei T. S. Nickel-Catalyzed Electrochemical Reductive Relay Cross-Coupling of Alkyl Halides to Aryl Halides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6520–6524. 10.1002/anie.201912753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Truesdell B. L.; Hamby T. B.; Sevov C. S. General C(sp(2))-C(sp(3)) Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reactions Enabled by Overcharge Protection of Homogeneous Electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5884–5893. 10.1021/jacs.0c01475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Harwood S. J.; Palkowitz M. D.; Gannett C. N.; Perez P.; Yao Z.; Sun L.; Abruna H. D.; Anderson S. L.; Baran P. S. Modular terpene synthesis enabled by mild electrochemical couplings. Science 2022, 375, 745–752. 10.1126/science.abn1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Zhang B.; Gao Y.; Hioki Y.; Oderinde M. S.; Qiao J. X.; Rodriguez K. X.; Zhang H. J.; Kawamata Y.; Baran P. S. Ni-electrocatalytic Csp(3)-Csp(3) doubly decarboxylative coupling. Nature 2022, 606, 313–318. 10.1038/s41586-022-04691-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Lou T. S.; Kawamata Y.; Ewing T.; Correa-Otero G. A.; Collins M. R.; Baran P. S. Scalable, Chemoselective Nickel Electrocatalytic Sulfinylation of Aryl Halides with SO2. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202208080 10.1002/anie.202208080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Perkins R. J.; Hughes A. J.; Weix D. J.; Hansen E. C. Metal Reductant-Free Electrochemical Nickel-Catalyzed Couplings of Aryl and Alkyl Bromides in Acetonitrile. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019, 23, 1746–1751. 10.1021/acs.oprd.9b00232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; l Franke M. C.; Longley V. R.; Rafiee M.; Stahl S. S.; Hansen E. C.; Weix D. J. Zinc-free, Scalable Reductive Cross-Electrophile Coupling Driven by Electrochemistry in an Undivided Cell. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 12617–12626. 10.1021/acscatal.2c03033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Zhu C.; Yue H.; Rueping M. Nickel Catalyzed Multicomponent Stereodivergent Synthesis of Olefins Enabled by Electrochemistry, Photocatalysis and Photo-Electrochemistry. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3240 10.1038/s41467-022-30985-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chang X.; Zhang Q.; Guo C. Asymmetric Electrochemical Transformations. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 12612–12622. 10.1002/anie.202000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huang X.; Zhang Q.; Lin J.; Harms K.; Meggers E. Electricity-driven asymmetric Lewis acid catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 34–40. 10.1038/s41929-018-0198-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Fu N.; Song L.; Liu J.; Shen Y.; Siu J. C.; Lin S. New Bisoxazoline Ligands Enable Enantioselective Electrocatalytic Cyanofunctionalization of Vinylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 14480–14485. 10.1021/jacs.9b03296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhang Q.; Chang X.; Peng L.; Guo C. Asymmetric Lewis Acid Catalyzed Electrochemical Alkylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6999–7003. 10.1002/anie.201901801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Song L.; Fu N.; Ernst B. G.; Lee W. H.; Frederick M. O.; DiStasio R. A. J.; Lin S. Dual electrocatalysis enables enantioselective hydrocyanation of conjugated alkenes. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 747–754. 10.1038/s41557-020-0469-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wang Z. H.; Gao P. S.; Wang X.; Gao J. Q.; Xu X. T.; He Z.; Ma C.; Mei T. S. TEMPO-Enabled Electrochemical Enantioselective Oxidative Coupling of Secondary Acyclic Amines with Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 15599–15605. 10.1021/jacs.1c08671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhou Z.; Xu S.; Zhang J.; Kong W. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective electroreductive cross-couplings. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 3262–3265. 10.1039/D0QO00901F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Durandetti M.; Périchon J.; Nedéléc J. Y. Asymmetric Induction in the Electrochemical Cross-Coupling of Aryl Halides with alpha-Chloropropionic Acid Derivatives Catalyzed by Nickel Complexes. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7914–7915. 10.1021/jo971279d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c DeLano T. J.; Reisman S. E. Enantioselective Electroreductive Coupling of Alkenyl and Benzyl Halides via Nickel Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6751–6754. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Qiu H.; Shuai B.; Wang Y. Z.; Liu D.; Chen Y. G.; Gao P. S.; Ma H. X.; Chen S.; Mei T. S. Enantioselective Ni-Catalyzed Electrochemical Synthesis of Biaryl Atropisomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9872–9878. 10.1021/jacs.9b13117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Liu D.; Liu Z. R.; Wang Z. H.; Ma C.; Herbert S.; Schirok H.; Mei T. S. Paired electrolysis-enabled nickel-catalyzed enantioselective reductive cross-coupling between α-chloroesters and aryl bromides. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7318 10.1038/s41467-022-35073-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yudin A. K., Ed. Aziridines and Epoxides in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2006. [Google Scholar]; b Huang C. Y.; Doyle A. G. The Chemistry of Transition Metals with Three-Membered Ring Heterocycles. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 8153–8198. 10.1021/cr500036t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jensen K. L.; Standley E. A.; Jamison T. F. Highly Regioselective Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of N-Tosylaziridines and Alkylzinc Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 11145–11152. 10.1021/ja505823s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Duda M. L.; Michael F. E. Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of N-Sulfonylaziridines with Boronic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18347–18349. 10.1021/ja410686v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Takeda Y.; Ikeda Y.; Kuroda A.; Tanaka S.; Minakata S. Pd/NHC-Catalyzed Enantiospecific and Regioselective Suzuki–Miyaura Arylation of 2-Arylaziridines: Synthesis of Enantioenriched 2-Arylphenethylamine Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8544–8547. 10.1021/ja5039616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Steiman T. J.; Liu J.; Mengiste A.; Doyle A. G. Synthesis of beta-Phenethylamines via Ni/Photoredox Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Aliphatic Aziridines and Aryl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 7598–7605. 10.1021/jacs.0c01724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Davies J.; Janssen-Müller D.; Zimin D. P.; Day C. S.; Yanagi T.; Elfert J.; Martin R. Ni-Catalyzed Carboxylation of Aziridines en Route to β-Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4949–4954. 10.1021/jacs.1c01916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huang C. Y.; Doyle A. G. Nickel-Catalyzed Negishi Alkylations of Styrenyl Aziridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9541–9544. 10.1021/ja3013825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jensen K. L.; Nielsen D. U.; Jamison T. F. A General Strategy for the Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure Azetidines and Aziridines through Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 7379–7383. 10.1002/chem.201500886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Woods B. P.; Orlandi M.; Huang C. Y.; Sigman M. S.; Doyle A. G. Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Cross-Coupling of Styrenyl Aziridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5688–5691. 10.1021/jacs.7b03448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Schmidt U.; Schmidt J. The Total Synthesis of Eponemycin. Synthesis 1994, 1994, 300–304. 10.1055/s-1994-25464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Barrow R. A.; Moore R. E.; Li L.; Tius M. A. Synthesis of 1-Aza-cryptophycin 1, an Unstable Cryptophycin. An Unusual Skeletal Rearrangement. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 3339–3351. 10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00255-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Borzilleri R. M.; Zheng X.; Schmidt R. J.; Johnson J. A.; Kim S.; DiMarco J. D.; Fairchild C. R.; Gougoutas J. Z.; Lee F. Y. F.; Long B. H.; Vite G. D. A Novel Application of a Pd(0)-Catalyzed Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction to the Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of Lactam Analogues of the Epothilone Natural Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8890–8897. 10.1021/ja001899n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Smith A. B.; Rano T. A.; Chida N.; Sulikowski G. A.; Wood J. L. Total synthesis of the cytotoxic macrocycle (+)-hitachimycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 8008–8022. 10.1021/ja00047a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For additional information and control experiments, see Supporting Information. Deposition number CCDC 2223639 contains the supporting crystallographic data for compound 1 in this paper

- Bottcher S. E.; Hutchinson L. E.; Wilger D. J. Nickel-Catalyzed anti-Selective Alkyne Functionalization Reactions. Synthesis 2020, 52, 2807–2820. 10.1055/s-0040-1707885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston C.; Palkowitz M. D.; Takahira Y.; Vantourout J. C.; Peters B. K.; Kawamata Y.; Baran P. S. A Survival Guide for the ″Electro-curious″. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 72–83. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Qian D.; Bera S.; Hu X. Chiral Alkyl Amine Synthesis via Catalytic Enantioselective Hydroalkylation of Enecarbamates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 1959–1967. 10.1021/jacs.0c11630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lu X.; Wang Y.; Zhang B.; Pi J. J.; Wang X. X.; Gong T. J.; Xiao B.; Fu Y. Nickel-Catalyzed Defluorinative Reductive Cross-Coupling of gem-Difluoroalkenes with Unactivated Secondary and Tertiary Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12632–12637. 10.1021/jacs.7b06469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang S.; Zhang J. X.; Zhang T. Y.; Meng H.; Chen B. H.; Shu W. Enantioselective access to chiral aliphatic amines and alcohols via Ni-catalyzed hydroalkylations. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2771 10.1038/s41467-021-22983-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diccianni J. B.; Diao T. Mechanisms of Nickel-Catalyzed CrossCoupling Reactions. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 830–844. 10.1016/j.trechm.2019.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.