Abstract

Policy Points.

First, policymakers can create conditions that will facilitate public trust in health care organizations by making creating and enforcing health policies that make exploitative behavior costly.

Second, policymakers can bolster the trustworthiness of health care markets and organizations by using their regulatory authority to address and mitigate harm from conflicts‐of‐interest and regulatory capture.

Third, policymakers and government agencies can further safeguard the public's trust by being transparent and effective about their role in the provision of health services to the public.

Context

Trust plays a critical role in facilitating health care delivery and calls for rebuilding trust in health care are increasingly commonplace. This article serves as a primer on the trust literature for health policymakers, organizational leaders, clinicians, and researchers based on the long history of engagement with the topic among health policy and services researchers.

Methods

We conducted a synthetic review of the health services and health policy literatures on trust since 1970. We organize our findings by trustor–trustee dyads, highlighting areas of convergence, tensions and contradictions, and methodological considerations. We close by commenting on the challenges facing the study of trust in health care, the potential value in borrowing from other disciplines, and imperatives for the future.

Findings

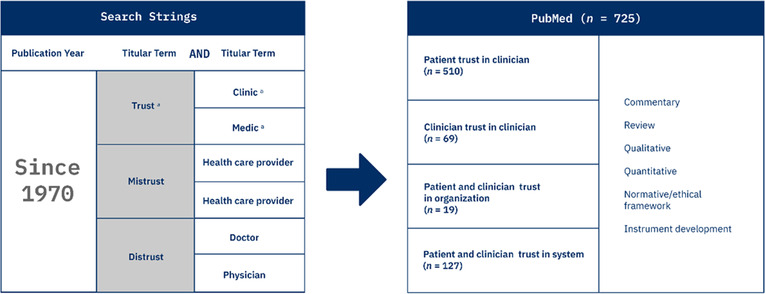

We identified 725 articles for review. Most focused on patients’ trust in clinicians (n = 499), but others explored clinicians’ trust in patients (n = 11), clinicians’ trust in clinicians (n = 69), and clinician/patient trust in organizations (n = 19) and systems (n = 127). Across these five subliteratures, there was lack of consensus about definitions, dimensions, and key attributes of trust. Researchers leaned heavily on cross‐sectional survey designs, with limited methodological attention to the relational or contextual realities of trust. Trust has most commonly been treated as an independent variable related to attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. We suggest two challenges have limited progress for the field: (1) conceptual murkiness in terms and theories, and (2) limited observability of the phenomena. Insights from philosophy, sociology, economics, and psychology offer insights for how to advance both the theoretical and empirical study of health‐related trust.

Conclusion

Conceptual clarity and methodological creativity are critical to advancing health‐related trust research. Although rigorous research in this area is challenging, the essential role of trust in population health necessitates continued grappling with the topic.

The literature on trust can be as frustrating as it is voluminous. Anyone who has tried to consult what has been written will share some version of a similar experience—what appear to be simple questions are met with complicated answers. Addressing this frustration is urgent, as the health policy and health services research communities have become refocused on trust as a matter of critical, real‐world importance. The COVID‐19 pandemic has clarified the role that trust plays in virtually every element of health care delivery. 1 , 2 , 3 Trust deficits among patients appear to have delayed COVID‐19 care, routine care, and vaccine uptake, thereby negatively impacting health. 4 , 5 , 6 But it was not only patients who harbored reasonable misgivings about whom and when to trust. Physicians and other clinicians working amidst an infectious disease pandemic realized just how much of their and their families’ safety relied on trusting others—their colleagues, their employers, and their patients. 2 In spite of countless heroic efforts to preserve life, the sense within the health care community is that the pandemic diminished already modest levels of trust in many, if not all, of the key actors in health care delivery. 7 In response, foundations, professional societies, and peer‐reviewed journals have recently committed themselves to the task of rebuilding trust. 8 , 9 We conducted a synthetic review of the literature to inform these efforts.

Contemporary experiences with the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States expose the importance of reservoirs of trust among people, between people and institutions, and between people and social systems of care. Trust is, at its core, a belief “that individuals and institutions will act appropriately and perform competently, responsibly, and in a manner considerate of our interests.” 10 This belief, for patients and clinicians alike, varies in terms of both levels of trust and the relationships between trustors (entities who trust) and trustees (entities who are trusted). Trust can be either general, whereby the trustor broadly finds the trustee worthy of their trust, or specific. Specific trust means that the trustor expects the trustee to undertake a particular action. Trust also operates at multiple levels or between different individuals and institutions. The expectations of a relationship between two clinicians, for example, differ from expectations between a clinician and their patient. Similarly, trust in systems or institutions is characterized by different beliefs and expectations than trust among individuals. 11 , 12 , 13 People (patients, clinicians, researchers, administrators, etc.) navigate each of these levels over the course of their experience with health care. 14

We have two primary goals in this article. First, we present high‐level themes from a review of the health services research and health policy literature on trust since 1970. This literature is voluminous, so we have elevated key findings, contradictions, and methodological gaps, organizing them by trustor—trustee dyads. Second, we describe some of the reasons that 50 years of literature can leave readers with little guidance for how to measure, much less build, trust. We suggest that there are two main reasons. First, the definitions of key terms, including both trust and trustworthiness, remain contested. Second, trustworthiness is incompletely observable to trustors and researchers, which creates a rash of methodological problems for a field that is committed to empirical observation. We explore these two challenges in light of what other, more theoretically inclined disciplines have to say on the subject and suggest a renewed role for theory in pointing the way forward on trust research.

Review

Methods

The purpose of a synthetic review is to summarize and assess the state of research in a given area to highlight gaps and opportunities for future scholarship. 15 We were interested in capturing empirical research and theoretical frameworks that would inform a future body of work on measuring and improving relationships based on trust. Our primary data source for this review was the health and medical literature, accessed using the PubMed database. We searched titles of journal articles published between 1970 and 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Articles aWe used these stem terms to search for several iterations of the words, for example, “clinic,” “clinical,” and “clinician.” [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Papers were restricted to those in the English language. We included only empirical studies conducted in the United States but included review and conceptual papers regardless of research setting. After cleaning the initial data set, the research team organized papers according to the trustor–trustee relationship being examined: patient–clinician; clinician–patient; clinician–clinician; patient– or clinician–organization; and patient–, clinician–, or general public–system. We refer to the papers that fall under each of these dyads as a subliterature. Based on a title and abstract review, papers were categorized according to methodology: commentary, qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, normative, or review.

Evaluating the strength of each subliterature required a subjective evaluation by the research team. We took the following into account: the relative size of the literature, the robustness of methodological approaches, the robustness of conceptual models, and the degree to which the literature was instructive for practitioners. Within each subliterature, we first identified systematic and scoping reviews. We then prioritized the findings of robust theoretical essays and empirical studies over commentaries in determining where there were settled questions or clear conceptual convergence. We then identified key research questions and made note of particularly surprising or interesting findings in individual articles. To do this, the research team met weekly for 4 months to discuss their assessment of each level of trust relationship and extract key themes and takeaways.

To triangulate and validate our findings, we conducted eleven 30‐minute interviews with researchers and key thought leaders in health and/or trust. These were conducted after reviewing the literature described above to validate our initial findings and provide additional expertise to inform the synthesis. We sought fresh perspective on the topic of trust by reviewing additional literature published in the fields of business/management, economics, sociology, and philosophy (and therefore not indexed in PubMed.) These papers were identified based on the expertise of the research team, references in papers identified in the core data set, and expert interviews.

The review that follows is synthetic in the sense that it simultaneously summarizes and assesses more than 700 papers. Our goal was not so much to report the findings of individual papers as to paint readers a more general picture of where the literature on trust in health care stands and how it can be moved forward. A list of all papers reviewed appears in the Appendix.

Findings

We structured our review according to key relationships in health care, focusing on patients and clinicians as the trustors and on patients, clinicians, organizations, and systems as the trustees. The result is five subliteratures: (1) patient trust in clinician, (2) clinician trust in patient, (3) clinician trust in clinician, (4) patient and clinician trust in organization, which we combined because of the small sample sizes, and (5) general trust in health care system, which includes papers that take patients, clinicians, and the general public as trustors. We organize our synthesis according to these relationships (Table 1 ). For each, we provide a summary of key findings and a reflection on areas of consensus, contradictions or tensions, and methodological considerations. Throughout, we describe study samples using the investigating authors' language (e.g., Black and African American). We summarize the relative strength of the subliteratures at the end of this section (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Subliteratures Within Health Services Research Literature on Trust

| Trustor (Entity Doing the Trusting) | Trustee (Entity Being Trusted) | |

|---|---|---|

| Subliterature #1 | Patient | Clinician |

| Subliterature #2 | Clinician | Patient |

| Subliterature #3 | Clinician | Clinician |

| Subliterature #4 | Patient or clinician | Organization |

| Subliterature #5 | Patient or clinician or general public | System |

Figure 2.

Quantity of Research Activity Among Trust Subliteratures. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Abbreviation: org, organization. aThis was the reference group.

Subliterature #1: Patient Trust in Clinician

Summary

The largest proportion of trust‐related papers considers patient trust in clinicians (n = 499) and specifically aims to grapple with the roots of mistrust or lacking trust among patients.

The prominent role that patient trust in clinicians plays in the trust literature is clear in a recent review of trust scales and measures by Ozawa and Sripad. 1 , 6 Among 45 trust scales and indices evaluated, the majority (n = 23) assessed patient trust in doctors, nurses, or other clinicians. Reviewed studies used measures of patient trust, mistrust, and distrust. Among the reviewed scales and indices, the most commonly assessed domain was communication, whereas other common domains included honesty, confidence, and competence. 17 Researchers studying trust continue to use a fairly wide set of measures without significant convergence. Researchers studying mistrust and distrust have converged more quickly on a small number of favored scales and measures. As evidence, see Williamson and Bigman's systematic review of 185 articles using mistrust and distrust measures. 18 Among the roughly three quarters of studies that used validated scales, the Group‐Based Medical Mistrust Scale, Medical Mistrust Index, and Health Care System Distrust Scale were most frequently used.

Researchers who have subjected trust‐related scales and indices to psychometric evaluation have found that additional development and testing is warranted. In a particularly rigorous treatment, Müller and team concluded: “the overall quality of [trust in physicians] measures’ psychometric properties was intermediate.” 19 Within the orbit of trust scales, mistrust scales, capturing patient attitudes and beliefs of doubt and skepticism, have been subject to fewer validation studies but held up well to psychometric scrutiny, perhaps because they have been developed and validated on more narrowly scoped demographic samples. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Those samples are most often made up of minoritized communities (e.g., African American, mixed race, and sexual minorities). 24

Within the patient trust in clinician subliterature, it is more common to consider trust an input (or predictor) to various outcomes of interest to the health system than to study trust as an outcome. To date, patient trust in clinicians has been frequently linked to improved behavioral outcomes and rarely to improved health outcomes. 25 In a systematic review of papers published on trust prior to 2004, Calnan and Rowe cautioned that the “evidence base to support the claims about the impact of trust on therapeutic outcomes is in short supply.” 26 Although that evidence base is stronger 15 years on, the number of commentaries that espouse the import of trust still outpace the number of empirical studies, and the vast majority of said studies are cross‐sectional surveys or qualitative interview papers. 18 Calnan and Rowe's diagnosis as to why the evidence base disappoints—“a lack of intervention studies or quasi‐experimental studies”remains relevant.

A review by Kelley and colleagues provides a potential exception to a general claim that the link between trust and health outcomes is modest. 2 , 7 It is a potential exception because the authors sought to assess whether the patient–clinician relationship general trust, rather than sole trust, has a beneficial effect on health care outcomes. 27 That said, the authors held a high evidentiary bar and included only randomized control trials (n = 13) in their systematic review. They found a range of interventions used to improve the patient–clinician relationship, including six designed to improve communication, three using motivational interviewing, one based on shared decision making, one using patient‐centered care, one using empathic care, and one using cultural competency training. The results indicated that the patient–clinician relationship has a small but statistically significant (p = 0.02) effect on health care outcomes such as pain scores, anxiety scale scores, and glycated hemoglobin. 28 , 29 , 30

Tensions and Contradictions

The conceptual differences among low trust, distrust, and mistrust need to be clarified so that scholarly discussion of these topics can take more meaningful shape. By and large, scholars have converged in their thinking that low trust is different from distrust in the following way: low trust is a modest (rather than fulsome) willingness to make oneself vulnerable at the hands of a trustee, whereas distrust is a negative expectation about the other's behavior, or an expectation that the trustee will attempt harmful behavior. 31 In light of this definition, Mechanic suggested that distrust is not the opposite of trust but is more accurately a functional alternative. 32

Where there remains rate‐limiting ambiguity, however, is in the distinction between mistrust and distrust. A recent paper by Griffith and colleagues attempted to disentangle these concepts by suggesting that distrust is an attitude toward a specific person or organization, whereas mistrust is a generalized skepticism based on historical injustice and systemic racism. 33 Griffith reiterated this distinction a year later in an article with Anderson. 17 This distinction is consistent with Brennan's 2013 systematic mapping review of distrust and mistrust, which suggests that although the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably, distrust refers more often to a lack of trust based on prior experience (particular), whereas mistrust refers to a general sense of unease (global). 34 Benkert and team's 2019 conceptual framing of mistrust in a systematic review of the concept takes a different view, suggesting that mistrust is a particular form of distrust (thereby inverting the relationship proposed by Griffith et al. and Brennan et al.). 24 , 33 , 34 The research community should continue to be intentional in seeking convergence on the conceptual definitions of low trust, mistrust, and distrust and, in so doing, be clear about what, if anything, is methodologically at stake in using these related terms.

Methodological Considerations

We see several avenues to deepen the available insights from the literature on patient trust in clinicians. First, the psychometric validity of the available scales should be further tested and refined. In spite of the large number of papers reviewed, there appears to be little convergence on the best tools to measure patient trust in clinician. Ozawa and Sripad identified 19 measures for evaluating doctor–patient interactions, most of which were unidimensional in 2013. 16 A year later, a review paper authored by Müller and colleagues evaluated the seven most popular measures for assessing patient trust in physicians, which ranged from five‐item abbreviated measures (Abbreviated Wake Forest Patient Trust Scale) to 51‐item measures (Trust Scale for Patient–Physician Dyad). 19 Both papers noted the lack of psychometric stability and need for further testing and validation, but Müller and colleagues offer a more action‐oriented assessment of the tradeoffs between brevity and reliability for the most commonly used. 19 Ozawa and Sripad also uncovered that few existing measures are designed for use with other kinds of health care professionals, including nurses, pharmacists, and researchers—a shortcoming of the trust literature that should be remedied by future research. 16 As team‐based care becomes increasingly standard, assessing patient trust in teams will also be warranted.

Second, the challenge of reciprocity and embedded relations must be addressed. In both survey research and qualitative studies of patient trust in clinicians, the literature routinely considers patient attitudes about their clinicians without recognizing that those attitudes are embedded in reciprocal relationships in which clinicians are simultaneously faced with a choice about whether, and how much, to trust patients. Similarly, patient trust in individual clinicians is embedded in patient attitudes about clinicians in general, the organization that employs said physician, and the US health system. These are broader challenges that face the entirety of the “trust” literature and will be, in some sense, a recurring suggestion for most levels of analysis.

Third, additional insight can and should be harvested from prior work indicating different levels of trust in different types of clinicians. Notably, the difference between trust in nurses, which is generally quite high, and trust in doctors, which is not always very high, deserves further investigation. 35 , 36 For researchers and scholars interested in trust in health care, it is worth asking what lies behind this disparity and whether physicians could deliberately “borrow” trust from nurses or mimic their trust‐building behaviors.

Our analysis also led us to consider areas in which there has been less energy to date but in which significant impact could be made. For instance, the literature would be strengthened by studies that treat trust as an outcome and assess how trust in clinicians is formed rather than treating trust as an input and asking what trust in clinicians predicts. Studies evaluating how patients make judgments of clinician competence or intent are particularly welcome. Mechanic noted this need in 1996, and it remains an open issue: “Physicians who seek to behave competently, responsibly and in a caring fashion often simply do not know how to convey these attributes in short, episodic encounters.” 32 Whether trust is treated as an input or an outcome, additional longitudinal work is critically needed to understand the trust formation process and the change in trust levels over time.

Subliterature #2: Clinician Trust in Patient

Summary

The subliterature of patient trust in clinician described in Subliterature #1: Patient Trust in Clinician far outpaces the literature on clinician trust in patients described here (n = 11). In a recent JAMA commentary, Grob and coauthors situate the lack of focus on physician trust in patients as an artifact of paternalism in the medical profession. 37 If “doctor knows best,” the main concern for trust researchers has been whether a patient is willing to trust said knowledge.

One review paper by Wilk and Platt from 2016 summarizes the growing literature on physicians as trustors. 38 Wilk and Platt's scoping review assessed not only the state of the literature on physicians’ trust in patients, but also physicians’ trust in other health care providers, institutions, and data systems or technology. 38 The authors found that “among articles examining physicians’ trust, rigorous investigations of trust are rare, narrowly focused, and imprecise in their discussion of trust.”

The few studies that do exist have found traction in the context of shared decision‐making and “partnership” models of patient–clinician relationships. Thom has been a pioneer in this area of research, and he and his colleagues are among the few who have developed a measure of clinician trust in patients. Said measure focuses on whether the physician views the patient as “good” (i.e., are patients honest and accurate in their communication, do they follow recommendations, and are they respectful toward the clinician?).

Tensions and Contradictions

Assuming that trust means something akin to “willingness to be vulnerable at the risk of exploitation,” then the literature on clinician trust in patients would benefit from more precision about what kind of vulnerability clinicians face in their relationship to patients. This precision will enable improved measurement and more consistent commentaries on the topic. For instance, physicians may need to trust that patients will not physically harm them, and efforts to measure and build this kind of trust may yield a series of concrete steps to ensure physical safety. Physicians may also need to trust patients to be reliable reporters of their symptoms, and efforts to measure and build this kind of trust are likely to look quite different. Thom's work on physician trust in patients has focused more on the latter kind of trust.

To their credit, studies that do examine clinicians’ trust in patients frequently note the mutuality of clinician and patient trust. 37 , 40 , 42 One can beget the other. The recognition that clinician trust in patients and patient trust in clinicians are mutual must be nuanced with an appreciation that the two instances of trust are based on different kinds of vulnerability. The rise of physical violence at sites of health care delivery remind us that clinicians can be risking bodily harm when they care for a patient, but more often what is at stake for clinicians in a therapeutic relationship is professional and reputational. 43 , 44

Methodological Considerations

Researchers have an opportunity to gain considerable insight into the complexity of trust by taking dyads as a unit of analysis. Social scientists and policymakers both have tended to focus more on individual factors and behaviors rather than traits of patient–physician pairs. This leaves exciting opportunities for researchers to undertake studies that explicitly examine the way in which patient trust in clinician is influenced by clinician trust in patients, and vice versa. Doing so might suggest taking trustworthiness to be an attribute of the relationship rather than of an individual. 45 Buchman and colleagues’ analysis entitled “You present like a drug addict: patient and clinician perspectives on trust and trustworthiness in chronic pain management” points the field in the right direction; although, in their study, the patient and clinician participants were not in therapeutic relationships to one another. 46

Well‐suited designs might include longitudinal evaluations that take patient–clinician pairs as the unit of analysis. Repeated questionnaires following visits (or other interactions) or interviews could inform the production of an empirically grounded process model of how small acts of trust coming from either the patient or clinician can invite reciprocal efforts. These designs could also grapple more directly with the constraints that unequal power might present for efforts to build trust in patientclinician relationships.

Subliterature #3: Clinician Trust in Clinician

Summary

The subliterature on clinician trust in other clinicians (n = 69) was modestly sized, and the plurality of papers were commentaries, which varied widely in relevance and quality. In many cases, the word “trust” was used in the title but was not a focus of the writing itself. Qualitative research papers were also prevalent, with several authors undertaking to describe the nature of collaboration among clinicians with different backgrounds. 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 A handful of papers were quantitative, most of which relied on cross‐sectional surveys of clinicians. Generally, this literature focuses on trust as a function of clinician competence. 49 , 52 , 53

In many cases, research investigating studies of clinicians’ trust in peers is motivated by an interest in how practicing doctors perceive colleagues in other professional roles, such as medical students or trainees, managers or administrators, and other types of clinicians such as pharmacists or chaplains. 47 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 Rather than using clinician trust in other clinicians to predict patient health outcomes, these papers commonly sought to use clinician experiences (e.g., position, time in role, and trauma) to predict clinician's trust in themselves and others. This is a useful example of trust being studied as an outcome rather than an input.

Linzer's 2019 paper in JAMA stood out for its thoroughness among the quantitative papers. 60 Therein, authors used conditions of the clinician's employment (e.g., high versus low autonomy and emphasis on quality versus productivity) to predict clinicians’ trust among a sample of internal and family medicine physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. That outcome measure was a composite trust scale that included measures assessing belonging, loyalty, safety focus, sense of trust, and responsibility to clinicians in need. This finding aligns with prior work by Succi and colleagues indicating that physician power over hospital decisions was a significant predictor of physician trust in managers. 61

This subliterature relies strongly on conceptualizations of trustworthiness as clinical competence. 49 , 52 , 53 Duijin and colleagues' qualitative paper is an exception in this regard, insomuch as it conceptualizes trustworthiness as a function of both competence and integrity. 48 Also instructive was Rushton and colleagues' investigation of trust‐forming and trust‐breaking behaviors among pediatric critical care teams, which suggested an alternative means of thinking about a multifactoral basis of trust among clinicians, including not only competence but also contracts and communication. 62 Lundh and colleagues offered an especially considered definition that went beyond a competence‐only perspective on trust:

Trust is a judgement by the trustor, requiring the acceptance of resultant vulnerability and risk, that the trustee (individual or organization) has the competence, willingness, integrity and capacity (i.e. trustworthiness) to perform a specified task under particular conditions. 51

Tensions and Contradictions

Researchers continue to contest with one another, albeit often indirectly, about what characteristics predict clinician trust in another clinician. Most treatments of the topic circle the same concepts (e.g., trust as competency and integrity), but the precision many clinicians demand of empirical research is elusive in studies of a topic as socially constructed as trust. The precise coefficients that should be assigned to each of the characteristics in a regression model may ultimately be too context dependent to be stable for generalized predictions.

Methodological Considerations

A plurality of papers on clinician trust in other clinicians were commentaries or editorials in which trust was undefined or not a key focus of the writing. 56 , 63 , 64 , 65 The literature on clinician trust in clinician could be strengthened by taking up new methods and questions. Methodologically, the nature of professional relationships may allow for trust to be measured between parties (A's trust in B and B's trust in A) rather than simply in one direction or the other. Given the field's clear interest in inter‐professional trust, dyads of people who work closely together but have different professional backgrounds may be a natural unit of analysis.

Finally, several papers suggested that more work is warranted on the clinician's trust in him‐ or herself. Several of our interviews highlighted the need for this work on clinician trust to begin as a process of introspection. Two recent papers suggest that trust in oneself is the core of trust in other people, but additional work more precisely identify the relationship between trust in oneself and trust in others and evaluate pedagogical tools for enhancing trainee self‐trust. 66 , 67 Also worth investigating is the role of hierarchy and the potential for some degree of mistrust to be inherent to relationships with formal power differentials. 68

Subliterature #4: Patient and Clinician Trust in Organization

Summary

The sub‐literature on trust in health care organizations is a small literature relative to other levels of analysis (n = 19), leading Anderson and Griffith to recently suggest that the topic has been “largely overlooked” in the context of health care organizations. 17 Though small, this subliterature includes a number of particularly strong conceptual papers. 69 , 70 , 71 , 72

The literature on trust in organizations began in earnest with an emphasis on clinicians as the trustors. A handful of early studies throughout the 1990s and early 2000s focused on clinician trust in new organizational forms, such as health maintenance organizations. Mechanic's 1996 paper “Changing medical organization and the erosion of trust” is notable as one of the first papers to explicitly take up trust in health care organizations as a focus. 32 Therein, he suggested that the shift to managed competition presented a challenge to the trust patients had previously had in health care organizations. The shift from a patient to a consumer mindset carried with it a number of potentially deleterious implications, one of which was that it positions health care services as just one of many market‐based goods and leads people to “question the motives and decisions of these organizers and providers of care.”

More recently, levels of patient mistrust in health care organizations have been associated with underutilization of health care services among the general public in quantitative and qualitative analyses. 20 , 73 Motivated by this kind of finding, Lee and colleagues authored a 2019 Viewpoint that outlined actions for health care organizations to take to increase trust among patients. 74 Based on a work group of 17 health care leaders and patient advocates who attended the 2018 American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, the authors suggested health system leadership should recognize that a trusting organizational environment is essential for achieving good processes and outcomes. The urgency of the authors’ language combined with relatively few references reflect a core challenge for the field: the importance of trust is widely recognized, but the evidence base for how to create it is thin.

Earlier this year, Anderson and Griffith suggested a strategy for measuring how trustworthy patients perceive health care organizations to be. 17 Taking leave from philosopher Hardin's view of encapsulated self‐interest, they suggest assessing how much patients see agreement between their own interests and the organization's interests. 12 Although such an approach appears conceptually sound, the authors note a series of hurdles to implementing this measurement approach, including patients’ lack of insight into what a hospital or health systems’ interests actually are.

Tensions and Contradictions

Once again, the relationship among levels of analysis deserves further consideration in this arena. For most patients, their relationship with a clinician is embedded in their relationship with the organization. In 2004, Mechanic suggested that physician trust can serve as a gateway for patient trust in organizations, writing, “Our trust in doctors and nurses often generalizes to their organizations and affects our willingness to bring our custom to them.” 75 More than a decade later, Smith's work on institutional betrayal in health care found that high trust in physicians is not protective in cases of institutional betrayal; no matter what the levels of trust in physicians are, trust in the organization decreases when betrayal occurs. 76 These findings are not necessarily contradictory, but they indicate a need for future research deciphering the cases in which trust in one level creates positive spillovers to another and those in which it does not.

There remains some question about whether the foundations of trust in individuals and trust in organizations are conceptually comparable. Many in health care have relied on a conception of trust in clinicians that rests heavily on assessments of clinician competence. If this is to become the dominant definition of trust for the field, thinking about trust in an analogous way at the organization level presents no problem. Clearly, organizations can be more and less competent. However, definitions of trust that rely on both competence and some kind of integrity may demand additional consideration at organizational levels of analysis. People frequently anthropomorphize organizations by describing them as caring or having integrity—but greater clarity on what constitutes organizational trustworthiness is warranted. 77 , 78 Goold has led this effort for 25 years, though additional work could further clarify how organizational trustworthiness is different from closely related terms like organizational reliance or confidence. 79 , 80 , 81 , 82

Methodological Considerations

The challenge of disentangling levels of trust becomes especially clear in evaluating studies of trust in organizations, as it is not clear how to isolate the organization level from patients’ experience with their clinician or their impressions of the system writ large. 11 Qualitative analysis of patients’ thought processes and perceived relationships between clinicians and organizations has the potential to provide necessary insight on these complex interactions.

Further investigation of clinician's trust in their employers is also warranted. For decades, insurers and health systems have attempted to change physician behavior (handwashing, fall prevention, prescribing practices, etc.) through the rejiggering of financial incentives. According to Dranove and Burns, it has become clear that financial incentives alone are unlikely to generate the scale of behavior change required for increased value creation. 83 The pair suggest that a main ingredient that has been missing from past efforts at “integration” and “coordination” of medical care is trust. Press Ganey's recent turn toward investigations of workforce trust in health systems suggests the importance of trust in one's employer extends beyond physicians. 2

Subliterature #5: General Trust in System

Summary

The subliterature on trust in the system is moderately sized relative to other literature on dimensions of trust (n = 127). We categorized papers as “trust in system” when the object of trust was generalized to evaluate attitudes toward the medical profession (i.e., general trust) or more than one stakeholder group (e.g., physicians, insurance companies, and/or professions). The most common article type was quantitative papers using cross‐sectional survey data to link patients’ trust with various attitudinal or behavioral outcomes. A considerable portion of research on trust in the “system” is conducted via nationally representative telephone surveys capturing point‐in‐time assessments. 84 , 85 , 86 Definitions of the “system” were varied, as were the ways that trust was assessed. A surprising number of papers operationalized trust, or mistrust, as belief in alternative medicine or conspiracy theories. 87 , 88 , 89 Approaches to measuring trust in the system were widely varied, yet the Medical Mistrust Index was used most frequently, and a handful of papers have offered modifications to the Medical Mistrust Index for group and other settings.

Benkert and colleagues’ 2019 systematic review of medical mistrust, which defines mistrust as “a tendency to distrust medical systems and personnel believed to represent the dominant culture,” is an especially strong treatment of system‐level dynamics. 24 Therein, authors reviewed 124 papers that linked medical mistrust with a patient‐level behavioral response (e.g., care seeking and medication adherence). Synthesizing the findings, the authors found that medical mistrust was often linked to prior negative interpersonal experiences with health care personnel and that medical mistrust predicted a variety of health‐related and service outcomes but no health outcomes (e.g., disease state). The drawbacks of the medical mistrust literature were a strong reliance on narrowly bounded racial and ethnic samples (specifically, African American and Native American) and lack of evidence that mistrust predicts, or contributes to, poor health outcomes.

Tensions and Contradictions

As in the literature on patient trust in clinicians, some work on patients’ trust in the system has linked trust to health behaviors such as using the emergency department as a usual source of care and in one case, self‐rated health status. 84 , 90 None linked directly to clinically documented health outcomes.

Although a number of studies look at Black–White differences in trust and distrust in the health system, findings are more variable than is often assumed. First, like the broader trust literature, the literature on racial differences suffers from a lack of precision about the trustee and trustor roles, as well as the trust object. Some studies include measures of both trust in clinicians and trust in systems, but findings are conflated or combined. 91 Second, the literature tends to oversimplify the relationship between race and trust by treating racial identity as a predictor of trust. The literature inconsistently includes other variables that are likely to impact trust for racially minoritized people, such as experiences of discrimination, oppression, and structural racism. 92

The widely assumed notion that Black people have less trust in the health system than White people on account of historical betrayals (e.g., Tuskegee Syphilis Studies) is inconsistently supported by the literature. 93 More generally, it may be that the differences in trust between Black and White patients, or members of the public, has been overstated. A recent analysis of national survey data, published by Greene and Long, found no difference between how much Black and White people reported trusting their own physician but significant differences in reported trust among income groups. 94 This confirmed a 2006 finding by Stepanikova and colleagues that reported trust in physicians does not differ between White and non‐White respondents in a nationwide survey sample. 95 These studies remind readers that there is nothing about racial identity that determines willingness to trust. Rather, people of color's experiences of racism and discrimination offer more explanatory power. 93 , 96

Hua and colleagues argue that mistrust does not explain racial disparities in health care utilization, but rather, experiences of discrimination and specifically having grown up in Jim Crow era and living in the South do. 97 These findings are consistent with Armstrong and colleagues’ observation that Black and White patients do not score differently in terms of trust in competence (i.e., the belief that professionals are good at their jobs) but do score differently in terms of trust in values (i.e., the system reflects and shares my values). The research team further finds that discrimination rather than racial identity explains lower system trust observed in their sample among African American respondents compared with White respondents. 98 Across these analyses, the importance of system values, experiences of discrimination, and life course factors provide valuable insight into racial differences that contradict the common assumption that Black patients consistently report lower trust.

Methodological Considerations

Several areas of methodological improvement are available to researchers interested in trust in the system. First, more precise and consistent definitions of what constitutes trust in the “system” would help to speed the pace of progress and facilitate convergence among scholars. To date, the system has been taken to mean the sum total of organizations and individuals who participate in the delivery of health care, biomedicine as a concept (contrasted with homeopathic or alternative medicine), and many other tangentially related ideas. This murkiness hampers clean measurement. When it comes to empirically assessing patients’ views of a health care system, Ozawa and Sripad identified 12 available tools. 16 Three tools measured mistrust, two measured distrust, and the remainder measured trust. Although the Medical Mistrust Index does appear to have become the widely accepted method for studying mistrust at this level of analysis, there appears to be less convergence in how best to measure distrust and trust in health systems.

Second, more work on clinician trust in the system is warranted, particularly in light of recent news about low or slow vaccine uptake among certain types of medical professionals. To date, the views of people who work as clinicians have been studied very rarely given in light of how much patients report trusting nurses, the extent to which nurses trust “the system” should be of considerable import to public health and health system leadership.

Third, disentangling levels of analysis deserves continued close consideration. A handful of papers have tried to simultaneously assess whether trust in providers or trust in the system (sometimes referred to as global trust) is more strongly associated with health behaviors. No clear pattern of results has emerged, but Hall's “Trust and satisfaction with physicians, insurers and the medical profession” points to the interrelatedness of trust across stakeholder groups and levels. 99 Brincks yielded similarly head‐tilting results when evaluating trust in individual clinicians and the system among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). 100 The authors concluded their review of the literature with the statement, “these studies suggest that feelings of mistrust toward the health care delivery system are distinct from feelings of mistrust toward an individual's physician and may influence HIV health care utilization differently.” Their own research found that higher levels of physician mistrust, but not medical system mistrust, were associated with longer time since the last visit to an HIV provider. Understanding how these levels are simultaneously related and distinct would help potential influences of trust target their efforts more precisely.

Rate‐Limiting Challenges

Two Big Challenges

Others have commented on how discordant and ultimately frustrating the health services literature on trust can be. 14 Toward the conclusion of our review, we stepped back to ask, why is that?We identified two major challenges for the literature, which we believe impede the health services research community's ability to develop clear recommendations to strengthen trust in key actors.

Conceptual Murkiness in Defining Terms

Many of the reviewed papers effectively talk “past” one another because of the lack of clarity around what authors mean by the terms trust and trustworthiness. Trust is used in at least two ways. Some researchers talk about trust as an attitude, or what is sometimes referred to as “affective trust.” 69 These researchers approach empirical tasks by asking questions such as “How much do you trust…?” and look for answers ranging between none and a lot. Others talk about trust as a behavior, or what can be called “enacted trust.” 34 Researchers who take this view tend to be economists who rely on theories of revealed preferences and dislike the idea of asking people to self‐report trust on a Likert‐type scale. Instead, these researchers look to behaviors or a set of choices. Most famously, economists’ “trust game” is a variant of experiments in game theory that relies on participants’ willingness to share money to indicate trust. 101

Table 2 provides a set of exemplary definitions of trust organized by trustor–trustee pairs to demonstrate the variability. It is easy to pick out general themes across the definitions—trust says something about the fidelity of one to another and implies a vulnerability in a relationship, for example—but the differences in definitions within and across levels stymie attempts to generalize findings or to effectively navigate to the practical implications of trust, mistrust, or distrust.

Table 2.

Examples of Trust Definitions by Trustor–Trustee Dyad

| Trust in Patient | Trust in Clinician | Trust in Organization | Trust in System | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician Trust in Patient | Patient Trust in Clinician | Clinician Trust in Clinician | Clinician Trust in Organization | Patient Trust in Organization | Clinician, Patient, and General Public Trust in System |

| “Trust in another person refers to an expectation that the other person will behave in a way that is beneficial, or at least not harmful, and allows for risks to be taken based on this expectation.” 40 | “A sense of safety and security in a situation and a feeling of reliance upon the staff.” 141 | “Trust is a judgement by the trustor, requiring the acceptance of resultant vulnerability and risk, that the trustee (individual or organization) has the competence, willingness, integrity and capacity (i.e. trustworthiness) to perform a specified task under particular conditions.” 51 | “The extent to which organizations and clinical personnel are perceived to be functioning in the interests of patients and the public, acting as their agents and as advocates for their needs and welfare.” 143 | “Trust is commonly understood as 'the optimistic acceptance of a vulnerable situation in which the trustor believes the trustee will care for the trustor's interests.'” 70 | “Trust is a continuous interaction that symbolizes verification of honesty, reliability, and confidence.” 144 |

| “…the expectation that the other is being honest and has good intentions.” 46 | “Trust exists when one party has confidence in an exchange partner's reliability and integrity.” 145 | “Interpersonal trust is a human belief (or referred to as an attitude in some sources that is broadly defined based on three main dimensions, namely, benevolence, integrity, and ability.” 146 | “A firm belief and confidence in the reliability, integrity and ability of another.” 147 | “…Trust is a forward‐looking assessment of an overall relationship.” 99 | “Psychologically, trust can be interpreted as involving attachment or as a causal factor in the development of the self. …Behaviorally, trust and its counterpart, betrayal, are understood as dichotomous forces that affect the quality of relationships at the organizational, team, interpersonal, and intrapersonal levels.” 62 |

| “Trust in physician can be defined as the patient's optimistic acceptance of a vulnerable situation and the belief that the physician will care for the patient's interests.” 19 | “Trust is the belief that someone or something is reliable, good, honest, effective…” 50 | “Trust is defined as a firm belief in the reliability, truth, ability, or strength of someone or something.” 148 | “…the five dimensions of trust derived from our conceptual approach [are]: competence (technical and interpersonal); fiduciary responsibility and agency; control; disclosure; and confidentiality.” 149 | “Public trust is trust placed by a group or a person in a societal institution or system, also described as 'being confident that you will be adequately treated when you are in need of health care.'” 89 | |

The literature on trustworthiness can appear equally dissonant. The term has been lazily defined as “the quality of being trusted,” but trustworthiness more precisely means the quality of being deserving of trust. Rather than existing as a binary (worthy or not), trustworthiness is most usefully conceptualized as existing on a continuum from low to high. From this agreement, two lines of inquiry have sprung forth—one led by those interested in describing and predicting the behavior of trustors and another interested in influencing the behavior of trustees.

The first line of inquiry is led by empirically focused researchers focused on description. According to these scholars, we trust people whenever we perceive that the risk of relying on them to act a certain way is low. In empirical experiments, the relationship between expectations of trustworthiness and trust is strong, in accordance with Hardin's “risk‐assessment view of trust.” 12 , 102 That said, retaining trustworthiness as a separate concept from trust enables researchers to explain why it is that some trustors choose to rely on trustees but turn out to be exploited. In these cases, empiricists suggest that the trustor chose to trust the trustee because they perceived them as trustworthy but misjudged the trustee's true trustworthiness and therefore were exploited. This happens frequently, as it is impossible to know for sure what someone will do in the future, including whether they will exploit you. Empirical researchers often resist making normative prescriptions about how a trustee can appear trustworthy because each trustor may have their own priors and preferences that shape their risk tolerance, expectations, and perceptions. Researchers can, however, use retrospective analyses to definitively say whether a trustee was trustworthy based on whether they exploited the trustor. On this point, a 2020 review of trust in the Annual Review of Sociology suggested that future work should focus on measuring how well trustors predict a trustee's actual trustworthiness. 13

The second line of inquiry is led by researchers focused on making normative prescriptions about health care actors should act. These authors use the term trustworthy to refer to a set of values or behaviors that a trustee should seek to embody in order to be deserving of a prospective trustee's trust. This approach is most common in bioethics but can be found in the many papers we reviewed that put forward multidimensional frameworks for thinking about trustworthiness. Similar to the themes identified in defining trust, trustworthiness often boils down to lists of virtuous traits such as “caring,” “competence,” “integrity,” etc. When considering the trustworthiness of individuals in health care, trait lists can beg the question of whether the critical traits (e.g., caring) are innate or can be cultivated. As conversations move to consider trustworthiness of health care organizations and systems, attributing traits to groups or corporate persons propels the conversation to a higher level of abstraction. Future work could helpfully aim to pinpoint what it is about teams, organizations, or systems that effectively communicates the presence or absence of these traits.

Similar to the busy landscape of trust definitions (Table 2 ), normative frameworks describing trustworthiness often include similar concepts—communication, competence, integrity, compassion, and humility—but continue to be developed and published as new, potentially more specific or clearer, restatements (Table 3 ). 11 , 62 , 74 , 103 , 104 The challenge with all framework development is to put forward a set of key terms that are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive—a tall task when definitions remain moving targets and the ordinary use of terms is at odds with technical definitions. The result is a framework landscape that conveys a reasonable overall impression of what is at the heart of the matter but leaves a trying decision for researchers having to choose an allegiance.

Table 3.

Examples of Trust Frameworks and Key Terms

| Focal Relationship | Framework Source | Key Framework Terms |

|---|---|---|

| Nonspecific | Frei and Morriss 103 |

|

| Ozawa and Sripad 16 |

|

|

| Patient–clinician | Wolfson 16 |

|

| Clinician–patient | No available frameworks | |

| Clinician–clinician | Rushton 62 |

|

| Clinician– and patient–organization | Hall et al. 108 |

|

| Patient–organization | Mechanic and Rosenthal 143 |

|

| Clinician– and patient–system |

Shoff and Yang 150 |

|

Protracted discussions of trust and trustworthiness can feel circular and risk being tautological. This led us to wonder: what value does a study of trustworthiness add to the already robust lines of work on high quality care, or patient‐centered care, or culturally appropriate care? Researchers should confront this question head on.

One reasonable answer to that question is that it can help us identify, and perhaps sort out, some legitimate conceptual puzzles. It is likely we can all bring to mind people or institutions that we believe are trustworthy but not trusted. Alternatively, people or institutions sometimes enjoy a great deal of trust without being trustworthy. As Goold wrote in 1998, “trust can be misplaced and distrust can be unjustified.” 81 To make sense of these scenarios, it is critical to have a concept of trustworthiness that is independent from trust. In these instances, what is often meant is that the person or institution is (or is not) trustworthy in the speaker's view, even as the person or institution faces a different assessment in the view of a third party.

Maintaining a concept of trustworthiness as a property of prospective trustees also enables researchers to consider questions such as: what is the optimal level of trust that patients, or the public, should put forward? Particularly against a cultural backdrop in which declining trust is framed as a problem, discussions of trust in health care can mistakenly assume that more trust is always better. Buchanan's 2000 essay entitled “Trust in managed care” is a rare paper that suggests it is appropriate for patients to withhold some trust in the face of a health care actor (managed care organizations). He argues that the goal should be “optimal, not maximal trust.” 105

A second answer to the question “what's the value of the term trustworthiness?” is that studies of trustworthiness, rather than trust, have value insomuch as they place the onus of responsibility on the entity looking to be trusted—most commonly, the clinician, the organization, or the system—to be worthy of trust. Recognizing how easy it can be to slip into blaming patients for low, mis‐, or distrust, efforts to place implicit responsibility on the high‐powered parties to change their behavior may be laudable. Anderson and Griffith illustrate this line of thinking:

“It is possible that interventions to improve [patient] trust may have been ineffective because they have rarely centered on improving the trustworthiness of health care organizations and systems.”

and

“…encouraging marginalized groups to place their trust in untrustworthy health systems undermines efforts to achieve health care equity.” 17

Efforts to shift responsibility may be less welcome in thinking about clinicians’ trust in patients—and specifically, how patients might face pressure to make themselves trustworthy in the eyes of the clinician, which is already a pressure frequently faced by patients of color. 106 , 107 Those who are most enthusiastic about helping clinicians and organizations become more trustworthy may find themselves less comfortable when it comes time to coach patients on how to be more trustworthy.

Observability of the Phenomena

Even in cases in which trust or trustworthiness is well defined, these concepts prove elusive for an empirically driven field such as health services research. This challenge occurs at two levels.

The first is that people in the trustor position cannot directly observe the trustworthiness of a prospective trustee (clinician, organization, system, etc.). In one of his many foundational papers for the field, Mechanic emphasized this point: “Although we can test the likelihood of expected behavior in a variety of ways, we have no firm way of knowing the future, thus trust is always accompanied by risk.” 32 In some sense, the prospective trustee's future behavior may even be unknown to them. As a result, their trustworthiness cannot be perfectly reported by themselves or anyone else. The best we can do is query people about their subjective perceptions of trustworthiness—or willingness to trust.

The second challenge is that researchers face incomplete information about how trustors make judgments about trustees’ trustworthiness. What is often missing in researchers’ data about trust in health care is information about what a “4 out of 5” means to the respondent on a trust scale, what kind of signals a trustor might have interpreted subconsciously, relevant past experiences in health care, the duration of the relationship in question, and what the trustor is considering trusting the trustee to do. What's more, levels of trust can vacillate day to day and minute to minute, but this dynamism is impossible to fully capture with current technology. The willingness of a research participants to disclose how much trust they really feel in a doctor or hospital is also likely influenced by that participants’ trust in the researcher. It is an inconvenient truth that these temporal and contextual factors likely matter for researchers’ understanding of observed trust. Unfortunately, institutional pressures at academic institutions push researchers away from grappling with these complexities. Although collecting complete information about how people form perceptions of trustworthiness may be impossible, future research could improve undertake creative research designs to attempt a fuller capture.

The flood of trust measures available to researchers is indicative of the challenges empiricists have had capturing these complex topics in survey form. For decades, researchers have tried to measure perceptions of trustworthiness (or lack thereof). The most common measures of trust evaluate it by proxy as an action or as a self‐reported effect. Economists have been the most likely to rely on action as a proxy for trust. More commonly, researchers have relied on a variety of self‐reported measures, scales, and indices. (Curiously, these are generally described as unidimensional in spite of the consistently multifactoral conceptual frameworks put forward. For a particularly thoughtful discussion of this puzzle, see the article by Hall and colleagues.)108p623 Within the trust in health care space, no fewer than 50 measures are available for researchers’ use.

Borrowing Insights from Other Fields

Consulting what has been written in other disciplines and collaborating with those trained in other disciplines—particularly philosophy, sociology, economics, and psychology—can enhance the theoretical and methodological toolbox of health services researchers. Below, we outline a handful of assumptions and findings from these disciplines that may be fruitfully applied to health‐related trust problems. We offer these nuggets as an invitation to colleagues to dig deeper into these fields. Those who call these disciplines home will likely find our synopses insufficient. Indeed, there are several useful papers to be written on the relationship among each of these social sciences and health services.

Philosophy

The philosophy literature differentiates trust as an attitude—one we have toward those we hope will be trustworthy—and trustworthiness as a property. Baier famously further distinguished trust from “mere reliance” on the basis that trust involves an expectation of goodwill, whereas reliance involves an expectation that someone or something will act out of selfishness or habit. Trust can be betrayed, whereas reliance can only be disappointed. 82 As an example, one relies on their alarm clock to go off at a certain time. If it does not, they are disappointed but not betrayed. On the other hand, one trusts a friend to keep their confidence, and when the friend does not, they feel betrayed. Health services researchers have not yet taken this distinction up in their own work, but it may bear relevance for organizational and system‐level studies.

For some philosophers, the question of trust rests on assessments of a prospective trustee's motives. For example, the “risk‐assessment” views of trust that have become popular in economics and beyond are primarily concerned with assessing the expected probability that a trustee will exploit. People are trustworthy if they are willing (motivated), for any reason, to do what the trustor needs done. This view has been criticized by philosophers who believe they make insufficient distinctions between trust and mere reliance. For others who do make this distinction, the mere existence of the trustee's motivation to do something is not sufficient (as it is for risk‐assessment proponents); the nature of the motivation matters as well. These scholars are sometimes referred to as proposing “motives‐based theories” of trust. Hardin's encapsulated self‐interest view is a particular form of a motive‐based theory that Anderson and Griffith most recently took up in their treatment of organizational trustworthiness. 12 , 17

“Nonmotive‐based theories” also differentiate trust from mere reliance but avoid assigning particular motives or feelings to prospective trustees. Under this umbrella, some writers have suggested that trust is not so much a question of what a trustee is motivated to do or will do, as it is a question of what a trustee should do (for more, see normative expectation theories of trust). Walker, a leader in this field, believes that a focus on normative expectations helps to explain why it may be reasonable to trust someone who takes great pride in their job, even if they are not motivated by goodwill. 109 Hawley has offered related, nonmotive‐based accounts of trust based on conceptions of commitment. 110 These theories may be worthy of close consideration in a field as heavily regulated and institutionalized as medicine.

Finally, the philosophy literature offers the community of health‐related trust researchers the concept of “trust pluralism.” Trust pluralists are those thinkers who accept that trust may not be able to be captured in a complete or unified theory. 111 , 112 the majority of philosophers continue to push for a singular theory that consistently distinguishes trust from reliance, there may be a certain freedom for health‐related fields in accepting pluralism as the most intellectually honest position.

Sociology

Sociological literature provides conceptual insight on important distinctions among aspects of trust, types of trust, and related social roles or expectations. In addition to widely used definitions of trust, sociologists have contributed to the development of related concepts like distrust and trustworthiness in a variety of contexts like health care, workplaces, the state, and social media. 10 , 70 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 Across this literature, general trust is consistently differentiated from particularized trust, which appears to be a distinction that the mistrust and distrust discourse in health services is beginning to adopt. 118

The sociological literature generally focuses its analytic power on identifying predictors or antecedents of trust, with less focus on what trust produces. 13 This tendency is evident in the literature on how social position, experiences, and opinions may cultivate trust. 119 , 120 , 121 Much of this work is survey based and provides methodological examples of how to analyze and understand differences in the antecedents of trust across populations or communities. 122 To the extent that the sociological focus on predictors of trust can inform a conceptually and methodologically rigorous approach to analyzing trustworthiness, it may be of particular importance to those who are increasingly exploring the trustee side of the relationship in health care.

Two books from the sociology literature stand out as potentially most relevant for health care. The first is Imber's Trusting Doctors: The Decline of Moral Authority in American Medicine, wherein the author closely aligns patients’ trust with the sense that medicine is a profession. 123 The second is Seligman's more general treatment, entitled The Problem of Trust. 124 Writing roughly 30 years ago, Seligman distinguishes trust from confidence on the basis that we trust people and have confidence in institutions and systems. He links these two ideas by suggesting that trust becomes more important when we see the breakdown of institutions and systems. Both books do a job that sociology does best, which is illustrate the relationship between individual trust and social structures. For health‐related researchers who have to date struggled to integrate levels of analysis, these works may be instructive.

Economics

Economics offers a handful of theoretical insights to those studying trust in health services. Economist Ho usefully compiles several decades of economic insights in his recently published book titled Why Trust Matters: The Ties that Bind, drawing from the work of founding fathers like Arrow and Frank. 125 , 126 , 127 One insight from game theory is the value of repeated interactions in building trust and cooperate behavior. 128 Thanks to the field's commitment to formal, mathematical modeling, economists have demonstrated how rational actors in a risky interaction may behave differently depending on their expectations of encountering one another again. When repeated interactions are expected, people are less likely to exploit one another for fear of retaliation—hence, they tend to behave in more trustworthy ways.

A second theoretical insight stems from a foundational assumption of economics: no one knows another's value set. In other words, I cannot know whether a clinician I see will exploit me (or why). This concession has propelled economists to develop signaling theory, wherein the key insight is that costly actions provide more information about a person's underlying values (or, for our purposes, trustworthiness) than so‐called cheap talk. Gambetta and Hammill famously employed signaling theory as a theoretical frame in their multiyear, qualitative study of trust between taxi drivers and passengers. 129 Hammill subsequently borrowed from that seminal study to research how Tanzanian and Ghanaian patients assess the trustworthiness of herbal clinics with colleague Hampshire. 130 This study can serve as a model for US‐based researchers interested in how patients made inferences about a clinician or organizations’ trustworthiness.

From a methodological perspective, the economics literature also offers a parsimonious, if contrived, way of testing for the presence or absence of trust in a laboratory called “the trust game.” Designed in 1995 by Berg, Dickhaut, and McCabe, the game presents a trustor with a choice between a sure outcome and trust, which could yield a higher (or lower) outcome. 131 More specifically, the game is structured so that a player is given money and asked how much they are willing to share with another player under various conditions. The more money a player shares, the more trust researchers deduce is present among the players. The game has been used in hundreds of publications that either discuss or are explicitly focused on trust. 101 The reliance on behavior as a marker of trust is standard for the field. To economists, trust is about making a choice: do I rely on this person or do I not? Economists assume that where they see a trusting behavior, a trusting attitude is present. What the trust game offers trust researchers generally is a means of formally modeling limited‐scope decisions of participating players.

Psychology

Even a limited review of the psychology literature on trust brings three key insights to the fore for health services researchers. First, psychological treatments of trust and trustworthiness very often focus on the role of the subconscious and heuristics in deciding when exposing vulnerability is safe. In the psychology literature, the ability to make accurate appraisals of trustworthiness is often referred to as an evolutionary adaptation that promotes individual and group fitness. The individual who can most swiftly discern a trustworthy cooperator is less likely to be duped out of vital resources for survival, and the group with the most efficient system for communicating and discerning trustworthy individuals is most likely to prosper by cooperating successfully. Heuristic cognitive processes are therefore an asset in making quick judgments of other's trustworthiness. DeSteno's work supports the assertion that much of the decision to trust is based on unconscious processes and is conveniently summarized in his 2015 book The Truth about Trust. 132 , 133 Field and lab studies support this claim, as immediately perceptible cues like torso posture, tilts of heads, and placement of arms seem to meaningfully affect a trustor's judgment, even though these poses are not directly linked to trustworthiness. 134 , 135 If these small cues matter as much as psychological evidence suggests, health services literature should incorporate these un‐ and subconscious influences on trust decisions into existing models.

Second, psychologists tend to focus on integrity rather than competence in their evaluations of trustworthiness. This makes the field a ready complement to health services, which has historically paid outsized attention to competence in evaluating trustworthiness. An integrity‐focused conception of trustworthiness emphasizes the conflicting mental mechanisms of selfishness and selflessness. A trustworthy person prioritizes selflessness, attending to another's well‐being to promote the relationship. An untrustworthy person prioritizes selfishness, prioritizing one's own needs and desires over the well‐being of others. Prioritizing others’ needs also promotes one's own long‐term goals, as an individual benefits from a good reputation and a reciprocal relationship in the future, whereas prioritizing one's own needs may lead to immediate benefits. By this logic, psychologists open the door to self‐control as a key characteristic of trustworthiness. A trustworthy person possesses the self‐control to choose long‐term over short‐term benefits.

Third, psychologists have most clearly enunciated a theory of trusting oneself, which is especially relevant for the literature on trust among medical trainees. By incorporating this temporal trade‐off between short‐term selfishness and long‐term selflessness into assessments of trustworthiness, the issue of trusting oneself becomes of a piece with issues of trusting other people. One can imagine a person as two personifications. Psychologists interested in restraint and the avoidance of temptation have most often considered people's current and future selves. Can the version of myself who wishes to spend less money trust my future self to do so—or must I cut up my credit cards? In health care, the relationship between present and past selves may be just as relevant, particularly for patients who may struggle to trust themselves in reporting symptoms or experiences. Long‐COVID patients, for instance, have faced struggles to trust themselves in the course of reporting their health experiences fully to clinicians. 136

These four disciplines—philosophy, sociology, economics, and psychology—each offer health service researchers useful ways of approaching trust. Metaphorically, each can be understood as a pair of glasses that helps the wearer to “see” unique features of social relations and interpret empirical results. As a result, researchers who take up the economics glasses will “see” things quite differently than those who choose to wear the psychology glasses, with empirical analyses unfolding from distinct starting assumptions. The practical problem is people wearing different disciplinary glasses are likely to speak past one another in reference to that things that others fail to recognize. Moreover, it is difficult—though perhaps not impossible—for a person to wear multiple pairs of glasses at once. Fully reconciling the differences among these disciplines may never come to pass, but it is possible for health services research to account for and explicitly enumerate the differences among them in studies of trust in health care. Below, we offer suggest some ideas of how health services research, as an interdisciplinary field, can more proactively manage this issue.

The Future of Health‐Related Trust Research

Improving the literature on trust in health care requires a clear confrontation of the rate‐limiting challenges we describe above. To some extent, trust is a complex phenomenon and will always force a certain level of definitional pluralism and epistemic humility on researchers. Still, some coordinated, intellectual elbow grease could advance the field. First, advancement requires more precise articulation of what various terms mean and, importantly, how they relate to one another, which is a theoretical undertaking. We have begun some of this work here, but surely others can take it on more explicitly. Second, improvement requires researchers to be both more careful and more ambitious when it comes to the methods used to study trust: more careful in the sense that measurement tools need to be thoughtfully selected and vetted and more ambitious in that study designs other than cross‐sectional surveys and point‐in‐time interview studies deserve wider consideration. In Table 4, we compile theoretical and methodological recommendations made throughout the paper into a roadmap of strategic imperatives and exemplary research questions for the field.

Table 4.

Recommendations for the Future of Health‐Related Trust Research

| Rate‐Limiting Domain | Strategic Imperative | Exemplary Research Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Theory development | Clarify definitions |

|

| Clarify necessary and sufficient conditions |

|

|

| Clarify whether trust/worthiness is the appropriate term for all potentially relevant trustees |

|

|

| Methodological considerations | Focus on trust and trustworthiness as outcomes |

|

| Pursue causal inference when appropriate |

|

|

| Conduct longitudinal studies |

|

|

| Conduct dyadic/relational studies |

|

|

| Assess the role of trust “spillovers” among systems, organizations, teams, and individual |

|

|

| Account for racism and other forms of discrimination in research designs |

|

|

| Pursue measures of optimality |

|

|

| Adopt a reflexive stance |

|

Theoretical Advancement

A 2016 paper from the Journal of Business Economics remarked that “theoretical trust research has outpaced empirical research by far,” which seems to be the opposite of the trends within health services, in which empirical research has seemingly outpaced theoretical work. 137 To remedy this, we suggest several theoretical tasks. First, health services researchers should more explicitly discuss and, ideally, converge on an understanding of the relationship between trust and trustworthiness and the distinction between distrust and mistrust. Second, the field should consider whether all levels of analysis can be discussed using the same vocabulary (trust and trustworthiness) or nonhuman trustees require different language (e.g., reliance, confidence, or other related terms). Finally, empirical researchers should make every effort to be explicit about whether the trust they are analyzing is (1) generalized or particularized, (2) placed in individuals, organizations, or social groups, and (3) to what end the trustee is being trusted. 13 , 138