Abstract

The academic literature seldom views information and communication technology (ICT) as a means to empower merchant seafarers in terms of their active and positive contributions to their mental health (MH) and overall well-being. Seafarers are often viewed as recipients and not the sources of health interventions. Using mixed methods, this paper examines how seafarers’ MH has not been the top priority among seafarers themselves, and how ICT and formal education might empower seafarers in health promotion. The pervasive culture of “ship first” in the maritime industry is palpable in the findings of this study, where seafarers do not prioritize their MH because the ship’s safe operations take precedence over everything else. Data shows that seafarers perceive MH interventions provided by companies as more useful when these have direct implications or effects on their families. In effect, seafarers may not see a priorities the physical and mental health support directly impacting their well-being. Nevertheless, there are some fundamental changes in the maritime industry in using technology to improve the MH of seafarers and their overall well-being, such as the development of MH applications (“apps”), helplines, or websites, coupled with the growing comfort of seafarers to use ICT.

Keywords: seafarers’ mental health, mental health, mental health education, empowerment of seafarers, health promotion for seafarers, education as health promotion

What do we already know about this topic?

Though mental health (MH) research on merchant seafarers has increased especially during this pandemic, there is an international recognition that people with MH problems (e.g., migrant workers) do not have a collective voice to address MH concerns including merchant seafarers.

How does your research contribute to the field?

This study addresses a gap in the academic literature on mental health research on seafarers, which is silent on the use of information and communication technology to empower merchant seafarers in terms of their active and positive contributions to their mental health.

What are your research’s implications towards theory, practice, or policy?

This paper has implications towards practice and policy on the use of seafarers of information and communication technology (ICT), particularly as means to improve mental health services for seafarers, and to empower seafarers in health promotion programs and activities such as mental health education for seafarers.

Introduction

Internationally, there is a pervasive awareness of the importance of mental health (MH) to everyone’s well-being, especially workers. MH problems are influenced by social context,1 including work environments. A great deal of attention has been paid recently to MH. However, for working-class groups such as seafarers working on international merchant vessels, the significance of MH in their well-being as workers has yet to be fully explored. Sampson et al2 reports that short-term MH problems increased between 2011 and 2016, indicating 37% of seafarers experienced MH problems. MH concerns of seafarers were recognized less than twenty years ago.3 Various seafaring national cultures where communicating MH issues remain taboo constitute a significant proportion of the 1.8 million seafarers worldwide. These cultures come from low- and middle-income countries such as China, India, Indonesia, Philippines, and others. In addition, a lower-visibility but higher-risk category of workers is not always covered by MH support,4 and seafarers are considered in such a category.

Before and during the COVID-19 crisis, research on seafarers’ mental health concerns focused on either one or a combination of the following: suicide, depression, post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), fatigue (including chronic fatigue syndrome), and stress (i.e., both physical and psychosocial).3,5-13 Seafarers’ MH are often associated with various risk factors characteristic of seafarings such as long-term separation from home vis-a-vis social isolation, work intensification, multinational crewing, poor life-work balance, job insecurity, criminalization of seafaring activities, working in constrained space, bullying, piracy, lack of shore leave, or short port stay.

In the maritime industry, seafarers’ human rights and decent work are considered under the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) 2006.14 The MLC 2006 highlights the importance of “mental occupational health effects, the physical and mental health effects of fatigues” under the Guideline B4.3.1: Provisions on occupational accidents, injuries, and diseases. However, the MLC’s understanding of MH is limited only to work-related concerns, where for example, it recommends that flag states and shipping companies are responsible for conducting risk assessments. Such recommendations would be important and useful. However, there are complex factors influencing seafarers’ MH, which require a wider understanding, including the network of support that individual seafarers might need especially, in times of MH crises.

Previous research identifies a range of MH support provided by various maritime stakeholders, including shipping companies, welfare organizations, families, and seafarers themselves.12,13 While the vulnerability of seafarers in a challenging socio-cultural workplace on board ships is recognized,15 it is seldom viewed that seafarers are empowered and autonomous individuals in terms of their active and positive contributions to the promotion of their MH. Indeed, seafarers are often viewed as recipients and not as independent sources of MH strategies. It is important to examine the role of seafarers in the promotion of MH, not only as recipients of care but also as active and autonomous agents who contribute to safer work environments. Historically, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that people with MH problems do not have a collective voice.16 Hence, WHO has implemented its vision of “empowerment,” where empowerment is used as a core concept in health promotion and involves “a multidimensional process through which individuals and groups gain better understanding and control over their lives” by understanding and acting on their MH concerns.16

Framed within the WHO’s interrelated concepts of empowerment and health promotion strategies,16 this study examines the lack of understanding of seafarers’ capacity and autonomy in health promotion, particularly MH promotion. By employing the concept of empowerment proposed by WHO, this study examines how seafarers’ MH has not been one of the top priorities among seafarers and how technology and formal education might empower seafarers in health promotion initiatives including MH education.

Literature on Empowerment and MH of Seafarers

The participation of individual seafarers in their health promotion is an important process for the global seafaring community to take control and responsibility for actions impacting their well-being in their profession and fulfilling their seafaring careers. Peer support in MH is one of the effective measures among seafarers.12,13 However, the process of seafarers’ engagement in health promotion has not been theorized in the literature. Seafarers understand the interplay between socio-economic constraints and political power relationships, which collectively engender what they can and cannot do especially in terms of protecting or enhancing their MH in their workplace. Though seafarers are not MH experts, they have lived experiences and understanding of how various factors are influencing their MH while working and living on board ships. In fact, health empowerment emerged from a synthesis of personal resources (e.g., seafarers’ capacity and autonomy) and social-contextual resources (e.g., support from social networks and social service support).17 While it is observable that health empowerment is one of the existing solutions for seafarers, their physical and mental health were not always considered to be the highest priority. Indeed, in globalized maritime businesses, power relationships between employers and employees have been highlighted in a capitalist and Marxist ideology of exploiting the poor by the rich.18

Located in the wider discussions on power influenced by the philosopher Michél Foucault, this section reviews and attempts to expand the concept of empowerment originally proposed by the WHO16 and applied to the context of MH research on seafarers. For the WHO and in the context of MH promotion strategies, empowerment is associated fundamentally with decision-making (i.e., autonomy), particularly the capacity to choose, influence or control mental health services available in the course of one’s life.16 Building on this definition, this study intends to expand the notion of empowerment by advocating for an improvement in the active participation of workers classified as vulnerable (e.g., seafarers) in decision-making regarding their MH concerns.

Theorizing Power

Autonomy and power are two-interrelated concepts. Building on Foucault’s examination of power, this paper assumes that power is exercised by different agents (e.g., individuals, nation-states, etc.). For Foucault, power means the socio-cultural “interaction of warring parties, as the decentered network of bodily, face-to-face confrontations, and ultimately as the productive penetration and subjectivizing subjugation of a bodily opponent.”19 Foucault sees the exercise of power as routinary, ubiquitous, and circulating. An interpretation of Foucault’s conception of power suggests that it is located at various levels of struggle between individuals or collectives, and power demonstrates itself in its effects.20 In the mind of Foucault, the individual (e.g., seafarer) is both subjugated and constituted through power and an agent who circulates power at the same time. Related to his examination of power is knowledge, what he referred to as “power/knowledge” regime. For Foucault the application and effectiveness of the power/knowledge regime is influential. Knowledge is associated fundamentally with power; firstly, because power assumes the authority of “truth” (or science) and, secondly, because power has the capacity to make itself true or manifest itself as the “truth.”19 In other words, the power/knowledge regime is both productive and constraining. It is productive because it opens up new ways of how we think of ourselves and how we behave; but it is also constraining because it limits the way we view ourselves. In practical terms, this might mean that if individuals view themselves as independent, autonomous, and capable of deciding what is important for themselves then this is an exercise of power. This exercise of power might not be true for many, especially vulnerable workers such as seafarers.21

In the context of seafarers, they can be positioned in various power relationships. Firstly, seafarers are employed by shipping companies or recruitment agencies, and their healthy bodies are contracted for the duration of voyages to operate ships. Their healthy bodies are the condition of employment by submitting a health certificate issued by an authorized doctor who assures their health conditions have met the standards. Secondly, seafarers work in a hierarchical organization where seniors and juniors are assigned to a clear division of labor, which determines their organizational ranks in the echelon of an absolute authority—the Captain. Thirdly, seafarers are continuously subjected to surveillance by authorities, such as Port State Control and shore-side management of their companies, where a regular surveillance exercise of the condition of the ship and its equipment for compliance is conducted. In other words, there are many layers of authorities that control the level of autonomy of seafarers, where it does appear that their autonomy is almost zero, because they are not allowed to challenge the authorities. These power relationships legitimate the “knowledge” that seafarers must obey and accept.

Empowerment in Seafarers’ Health

Such power and knowledge coined by Foucault can be seen in seafarers’ attitudes in MH situations where seafarers do not always feel comfortable talking about their MH problems. This might stem from the “employment fears” of seafarers, a fear which looks incompatible with the notion of healthy minds and bodies. WHO’s concept of empowerment is primarily associated with clinical MH service users where the key to empowerment is the removal of formal or informal barriers and the transformation of power relations between individuals, communities, services, and governments.16 In other words, users of MH services and interventions see themselves as empowered individuals capable of transforming themselves and the wider community. For the WHO, empowerment has four elements: self-reliance, participation in decisions, dignity and respect, and sense of belonging and the ability to contribute to the wider community.16

The WHO’s concept of empowerment evolved from the widely used health belief model. Broadly defined, it is a theoretical model which attempts to examine key factors of the individual’s health-promoting behavior based on various risk and benefit perceptions. Though not exhaustive, commonly used perceptions in the model are perceived susceptibility (i.e., the individual’s perceived threat to a sickness), perceived benefits, perceived severity (i.e., perception of consequences for action or inaction), perceived barriers to action, and confidence in the potential for successful action or changed behavior.22,23

Additionally, empowerment is recognized in the relationship between humans and technology in health promotion, where technology would potentially, and does, empower humans to increase their capacity to improve their well-being. Haraway24 understands how machines and organisms can be combined and blended into material reality. This notion of empowerment in seafarers’ health through technology opens up a new, modern potential of recognizing seafarers as active agents of promoting their well-being on board ships. Recent enthusiasm in automation and digitalization seen in the maritime industry has been anticipated as further crew reduction on board25; however, technology can be considered a booster of empowerment for seafarers. This collection of ideas about where technology might further empower seafarers inspired this study, particularly the analysis of MH support through technology is used to further this point (presented below).

MH of Seafarers in Recent Literature

It is notable that various stakeholders recently paid attention to the MH of seafarers. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, research focused on either comparing seafarers’ MH with land-based workers,3 or investigated occupational stressors of seafaring which contributed to poor MH outcomes.26

Company-based strategies were suggested to improve or protect seafarers’ MH.11,27,28 Unsurprisingly, the focus of these recommendations was not to empower seafarers because the recommendations were mostly company-level policies and practices imposed on the seafarers such as anti-bullying and anti-harassment strategies and the promotion of healthy lifestyles (e.g., good nutrition, rest, and social activities). The MLC 2006 sets the minimum labor and welfare standards for seafarers; hence it is used as one of the bases to examine seafarers’ MH. However, the MLC 2006 falls short in explicitly promoting seafarers as agents responsible for their MH. That is, its recommendations state the necessity of investigating “special physiological or psychological problems created by the shipboard environment” [Guideline B4.3.6(c)] and “problems arising from physical stress on board a ship” [Guideline B4.3.6(d)].5 These statements and other related provisions in the MLC, 2006 have limitations in empowering seafarers because they are viewed as recipients of MH strategies instead of active co-contributors with maritime administrators, ship owners, and other stakeholders.

It is widely held that MH is crucial for the overall welfare of seafarers. Seafaring remains to be a dangerous and risky occupation, and since the pandemic began, research on the impact of COVID-19 on seafarers’ MH has painted a bleak picture. For example, self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, and general psychiatric disorders were higher during the pandemic than before.12,29-34 Mental and physical exhaustion due to extended contracts and/or lack of shore leave and wastage (i.e., seafarers retiring early or leaving the industry) were also reported.12,35,36 Suicide among seafarers and abandonment of seafarers by ship owners during this pandemic remains a serious but generally publicly unknown issue.37-40 Except for one study,12 none of the literature cited has investigated how seafarers are the sources of psychosocial support of their fellow crewmember during this pandemic. The above discussion demonstrates a gap in the literature on empowerment of seafarers as agents of MH for themselves and their peers.

The strategies and potential benefits of empowering seafarers to be active contributors in promoting their MH have not been previously considered in research. Building on the elements of empowerment, it is also expected that the formal education and training of seafarers on MH would improve their participation in decisions on their MH and enhance their abilities to contribute actively and positively to welfare regulations and programs, including on MH. Indeed, the role of formal MH education or training for seafarers has only been recently explored,41,42 but its potential impacts have not been documented and examined.

Research Methods

This paper is based on a research project examining the psychosocial interventions provided to international seafarers during this pandemic. Research ethics clearance was granted by a university’s research ethics committee. Informed consent, the anonymity of participants, and confidentiality of data were observed. The study used a two-phase strategy, which employed both qualitative and quantitative methods. The first phase of the study focused on collecting qualitative data from in-depth interviews, which was carried out from March to June 2021. In-person and remote interviews (i.e., by phone, Internet call, email, or Facebook’s private messenger) were conducted with 26 individuals from 8 countries, namely Brazil (1), China (9), India (1), Jamaica (1), Japan (2), Nigeria (1), Philippines (10), and the United Kingdom (1). Participants were recruited using convenience sampling and snowballing techniques. Interviewees included seafarers (14), spouses of seafarers (2), chaplains (2), a representative of maritime administration (1), representatives of shipping or crewing companies (5), and representatives of maritime schools (2) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profiles of in-depth interviewees.

| Variable | Description | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nationalities | Brazilian | 1 (3.8) |

| Chinese | 9 (34.7) | |

| Indian | 1 (3.8) | |

| Jamaican | 1(3.8) | |

| Japanese | 2 (7.7) | |

| Nigerian | 1 (3.8) | |

| Filipino | 10 (38.6) | |

| British | 1 (3.8) | |

| Gender | Male | 21 (80.8) |

| Female | 5 (19.2) | |

| Role of social status in the industry | Seafarers (both ratings and officers) | 14 (53.8) |

| NGOs (i.e., chaplains) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Representatives of crewing or shipping companies | 5 (19.3) | |

| Representative of maritime administration | 1 (3.8) | |

| Representatives of maritime schools | 2 (7.7) | |

| Family of seafarers (i.e., spouses) | 2(7.7) |

The seafarer-interviewees were asked if they knew of any MH intervention provided to them by various stakeholders (i.e., government agencies, maritime companies, NGOs, trade unions, family, colleagues, etc.). Then questions were asked whether they used or experienced these interventions, including the perceived usefulness of these support to their mental well-being. Finally, other interviewees were asked what MH support they provided, and if they knew of any other support in the industry. From the interview data, the study managed to list the various supportive measures provided to or used by seafarers.

In the second phase of the data collection, a survey was conducted from July to September 2021, where a total of 1,412 seafarers participated. However, only 817 respondents were included in the analysis because they answered all the questions. The majority of the respondents were Filipinos (85.1%), males (96.7%), and officers (67%) (as compared to ratings). The average age was 31, with an age range of 18 to 69. A complete overview of the demographic profile of respondents is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic Information of the survey participants.

| Variable | Descriptions | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | In years | Average age: 31 |

| In years | Age range: 18-69 | |

| Nationality | Filipino | 695 (85.1%) |

| Chinese | 70 (8.6%) | |

| Undeclared nationality | 34 (4.1%) | |

| Bangladeshi | 7 (0.9%) | |

| Indian | 5 (0.6%) | |

| Jamaican | 3 (0.4%) | |

| British | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Indonesian | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Australian | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Gender | Male | 790 (96.7%) |

| Female | 15 (1.8%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 12 (1.5%) | |

| Rank | Officers | 547 (67%) |

| Other (i.e., cadets) | 145 (17.7%) | |

| Ratings | 125 (15.3%) |

For the first stage, the interview data were transcribed, coded, and thematically analyzed.43 For analysis of the survey data, descriptive statistics were performed using STATA SE version 12.

Limitations of the Study

This paper recognizes the following limitations. Firstly, the survey results might suffer from recall bias because the data were collected more than a year after the COVID-19 crisis began. That is, it is possible that the respondent’s views and experiences of COVID-19 and the support that they might have received could have changed. Secondly, due to its convenient sampling, the survey’s results cannot be generalized to a larger population. The sample also reflected the predominantly male seafarers’ perspectives though the ratio of female participants (1.8%) was higher than the estimated population of women seafarers (1.28%) found in the literature.44 Finally, using an online web-based survey might exclude respondents who are either not confident in using or do not have access to this type of platform.

Results and Discussion

Less Priorities on Supporting Seafarers’ MH and Well-Being

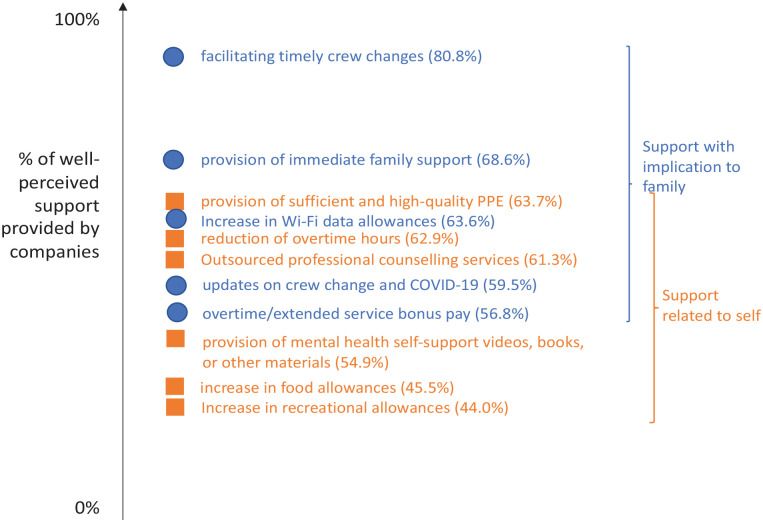

According to our survey, the respondents perceived as highly useful the eleven forms of support directly provided by companies as, and at different degrees between 80.8% and 44.0% (see Figure 1). Five of the 11 supportive interventions viewed as implying the seafarers’ families were color-coded in blue; while the 6 remaining strategies were coded in orange as these interventions related only to seafarers.

Figure 1.

Highly useful company support perceived by seafarers.

This coding analysis indicates seafarers perceive the supportive interventions that directly affect their families as highly useful. These interventions are “facilitating timely crew changes” (80.8%), “provision of immediate family support” (68.6%), “Increase in Wi-Fi data allowance” (63.6%), “updates on crew change and COVID-19” (59.5%), and “overtime/extended service bonus pay” (56.8%). These interventions identified as highly useful by the respondents would either allow seafarers to return home, communicate with their families, or financially assist them during the crisis caused by the pandemic.

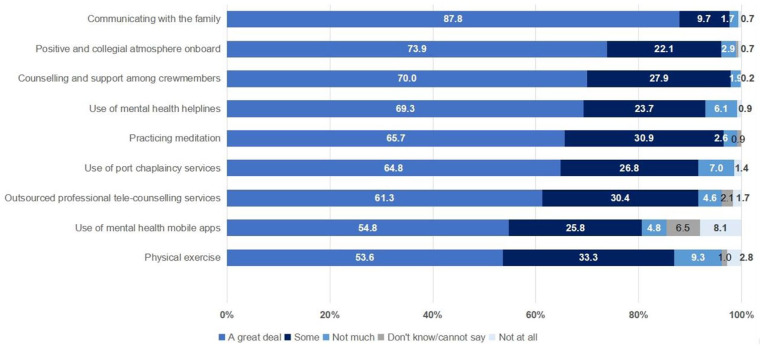

Figure 3 shows that communicating with their respective families is perceived as the most effective MH support (87.8%) despite challenges since it might need efficient, quality, and cheap internet connectivity. In this study, 15% of the respondents had no access to the internet, and among those who had access, more than a quarter (27%) were unsatisfied due to poor connectivity. It has been reported that it was not the availability of the internet per se that has contributed to the improvement of seafarers’ mental well-being but the speed and stability of the internet.6 The use of technology in health promotion to improve the mental well-being of seafarers while on board is slowly developing in the industry. Though, there is a need to improve the internet infrastructure, logistical support, and capability and increase awareness of the benefits of these technology-based MH interventions.

Figure 3.

Perceived usefulness of technology and non-technology-based MH interventions.

When it comes to interventions relating to seafarers’ own happiness and needs, the data shows relatively lower usefulness felt by seafarers, such as “provision of sufficient and high-quality personal protective equipment or PPE” (63.7%), “reduction of overtime hours” (62.9%), “outsourced professional counselling services” (61.3%), “provision of mental health self-support videos, books, or other materials” (54.9%), “increase food allowance” (45.5%), and “increase in recreational allowance” (44.0%). Figure 1 demonstrates that seafarers perceive interventions provided by companies as more useful when these have direct implications or effects on their families. In effect, seafarers may not see as priorities the physical and mental health support directly impacting them.

From a perspective of health “empowerment,” seafarers could be encouraged to prioritize their (mental) health at the workplace. Our analysis indicates that seafarers may accept sacrificing their own health over the well-being of others such as their families. That is, our data implies a lack of awareness among seafarers that their health including their MH might be considered as necessity or priority. Baumler and colleagues have suggested that a “ship first” attitude among seafarers might be observed where ship safety and efficient operations are prioritized over the seafarers’ health and safety concerns.45 Seafaring culture is built around the work organization aboard ships where the individuals’ needs are not prioritized over the collective objectives of the ship.45,46 Seafarers were observed to prioritize the ship’s operations over their MH because these operations are associated with their employee performance and are related to the bigger concern of job insecurity among seafarers. In effect, awareness of promoting their health or MH might be needed. A cultural change that values the individual physical and mental health needs as priorities might be needed. To do so, seafarers should understand their autonomy and capacity as active agents to change the occupational culture on board ships.

Our data indicates that seafarers are aware of their supportive role to their fellow crew members. Positive psychology has suggested that a healthy dose of self-reflection, including seeing oneself as a powerful agent to manage stress, might be an important psychological technique to develop. In our interview data, some seafarers are aware that they contribute to the positive MH of their fellow crewmembers by providing peer support through peer counselling, as the following quotes suggest: “I would often provide encouragement to colleagues tell colleagues that we had to accept the present realities” (Nigerian Chief Engineer, male); “I received casual psychological counselling from older leaders on board” (Chinese Master Mariner, male); “By interacting with everyone, I am somehow contributing to helping them avoid the negative mental effects of social isolation” (Filipino Second Officer, male); while some Filipino seafarers said that “We extend some support to our seafaring relatives and friends whose contracts were extended by encouraging them to be patient and to pray” (Focus Group with Filipino seafarers). From these selected quotes from various seafaring nationalities, seafarers provide informal peer counselling, and this practice appears common among seafarers. In summary, on the one hand, some seafarers do not view themselves as agents for their MH. Still, on the other, some acknowledge that they potentially contribute to the positive MH of their fellow seafarers. For the latter, our survey demonstrates that 8 in 10 seafarers have engaged in a positive and collegial atmosphere onboard. A recent study showed that regular social interactions on board benefit seafarers’ overall MH. Collegial activities reduce stress and anxiety and help seafarers create safe and efficient teamwork.47

Where seafarers have been trained to be psychologically resilient, it might have been expected that they see themselves as agents who cultivate and protect their MH. In this regard, training on MH and well-being is an important intervention. Lately, IMO member States have been conscious about the MH of seafarers in response to bullying and harassment on board, which was discussed during the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) 105 and the Human Element, Training, and Watchkeeping Sub-Committee (HTW) 9 will make a follow-up in terms of training.

Empowerment Through Technology

The empowerment of seafarers as active agents who promote their health and well-being at sea will be more effective with the help of information and communication technology (ICT). According to our interviews and survey data, MH interventions with technology mean seafarers’ access to reliable and cheap internet, their use of MH apps, MH helplines, or the tele-counselling. The role of ICT, particularly the use of the internet, smartphones, computers, and web-based applications, have been proposed to promote seafarers’ MH. Nowadays, shipping companies have provided internet facilities on board ships. Internet-based communication applications such as WhatsApp, Messenger, or emails are used to communicate with families for free or at a minimal cost. As part of MLC 2006, onboard internet access has become mandatory, with some companies offering unlimited internet access to crew members.

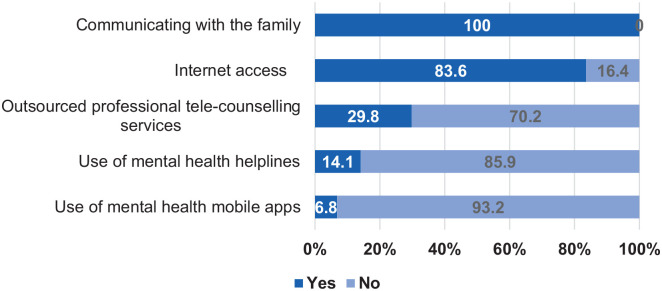

As shown in Figure 2, all respondents have communicated with their families. It means seafarers treasure family relationships, and connecting with them is important, especially during the current pandemic. Although not shown in the graph, the frequency of communication varies where seafarers communicate to their families either monthly (10.9%), twice a week (7.2%), once a week (20.6%), or daily (61.2%). Shipping companies should continue to ensure free access and good internet connectivity, which might increase seafarers’ retention rate, work performance, and mental wellness.48

Figure 2.

Use of technology-based MH interventions.

From the qualitative data, a wife of a Filipino seafarer suggested that companies should improve facilities where seafarers can “get in touch with family.” It is consistent with a Chinese master mariner’s wish where companies “make sure that the crew can communicate with their families.”

Figure 2 shows that most respondents (83.6%) have experienced internet access onboard. Although not shown in the graph, internet access is not always free, and some have to pay (22.6%). One in 5 respondents enjoyed free and unlimited internet access, while 2 in 5 have free but limited daily use. A chaplain’s response also suggests this point in an interview where she reported that “Many ships still do not have free wi-fi on board, and this makes it difficult for seafarers to stay in touch with their families at home. This is even more vital in this pandemic” (British Chaplain, female). In other words, the results showed that providing free, reliable, and fast internet access onboard remains a problem for seafarers.

Tele-counselling is a primary care-level MH service that involves specialists such as psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, chaplains, and social workers, who use technology-based communication to counsel a patient. As one chaplain reported, “We provide a 24-hour digital chaplaincy service which seafarers can access via our website, so that they can speak to someone online at any time. Our chaplains are trained in post-trauma care and mental health awareness” (British Chaplain, female).

Using technology to conduct online clinical therapy sessions with clients has shown various benefits for clients. It has been reported that the client’s MH outcomes vis-à-vis face-to-face therapy are comparable.49 From observations, seafarers who might be experiencing MH symptoms but are afraid to talk to their families or work colleagues prefer someone anonymous who listens, respects confidentiality, and is without bias. In this study, however, only 3 in 10 seafarers have used outsourced tele-counseling services during this pandemic. Moreover, the use of MH mobile apps (6.8%) and MH helplines (14.1%), are low. A probable reason for the low use of these two MH interventions is the cultural taboo among seafarers surrounding MH. In a traditionally masculine occupation, men are often not comfortable or ready to talk about their MH problems, especially to strangers or through digital apps.

In short, seafarers have not widely utilized technology-based interventions since they need ICT infrastructure (i.e., internet, smartphones), and knowledge on how to use both the technology and the apps, aside from willingness and confidence in using the MH apps or MH helplines.

Further, in this study, 5 non-technology based MH interventions are perceived as important (e.g., communicating with the family). As shown in Figure 3, these are a positive and collegial atmosphere onboard (73.9%), counseling and support among crewmembers (70.0%), practicing meditation (65.7%), and use of port chaplaincy service (64.8%). The survey results show that health promotion should urgently focus on utilizing more affordable, available, and easily accessible MH interventions while simultaneously reminding the maritime industry and employers to provide reliable, easy-to-use, and cheap ICT infrastructure to every vessel. In addition, increasing awareness of the availability and benefits of these MH interventions through capability building might be necessary, such as through education and training of seafarers on these interventions.

Conclusion

This study has shown that empowerment of seafarers in health promotion has the potential to promote MH and well-being on board ships. The family remains one of the most important sources of strength for them and serves as anchor to their well-being. However, the pervasive culture of “ship first” among the participating seafarers is palpable where seafarers do not prioritize their MH and overall health and safety because the ship’s safe operations take precedence over everything else. Nevertheless, there are fundamental changes in using technology to improve the MH of seafarers, such as the development of MH apps, helplines, or websites, coupled with the growing comfort of seafarers to use ICT despite the weaknesses shown here. Developing formal education on MH for seafarers has not been tapped though the IMO member States have just begun discussing the need for seafarer’s training. Overall, the changes in using technology to improve seafarers’ MH and the potential of MH education for seafarers are seen as invaluable and long-term solutions to empower seafarers in health promotion. Future research directions might include developing MH education and training for seafarers, which are culture-specific and sensitive to gender. As seafaring is a multi-national occupation ship-owning and labor-sending countries might benefit if they respectively and collaboratively develop MH education and training that address MH concerns. They also need to ensure that MH education for seafarers is sensitive to the seafarers’ culture and informed by the occupational culture of international seafaring, given the unique characteristics of this important profession.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Sanley Abila wishes to acknowledge Fulbright-Philippines and the Institute of International Education of the Department of State of the United States of America for an advanced research scholarship grant which afforded him time to work on this paper.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors would like to thank Lloyd’s Register Foundation (LRF) in the UK for funding the study from which this paper is based on. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the various universities to which the authors are affiliated, respectively.

Ethics, Informed Consent and Ethical Approval: The World Maritime University’s research ethics committee granted the ethics clearance on 15th February 2021 for the study where this paper is based, with reference number REC-21-03(R). Informed consent, anonymity of participants, and confidentiality of data were observed from recruitment of research participants, management of research data, and up to the writing of the final report. During the recruitment process, copies of the research information sheet and informed consent form were provided to interviewees to ensure that their participation was voluntary and informed.

ORCID iDs: Sanley Abila  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0654-2348

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0654-2348

Lijun Tang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6815-0625

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6815-0625

References

- 1. Vos J, Roberts R, Davies J. Visions for mental health care. In: Vos J, Roberts R, Davies J, eds. Mental Health in Crisis. SAGE; 2019:120-128. doi: 10.4135/9781526492579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sampson H, Ellis N, Acejo I, Turgo N., Changes in. seafarers’ health 2011–2016: A summary report. SIRC; 2017. https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/116526/1/Changes%20to%20seafarers'%20health%202011-2016.pdf (accessed January 5, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iversen RT. The mental health of seafarers. Int Marit Health. 2012;63(2):78 89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deloitte. Mental health and employers: Refreshing the case for investment. January 2020. https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/consulting/articles/mental-health-and-employers-refreshing-the-case-for-investment.html (accessed November 15, 2022).

- 5. Mellbye A, Carter T. Seafarers’ Depression and Suicide. Int Marit Health. 2017;68(2):108-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seyle C, Fernandez K, Dimitrivech A, Bahri C. The long-term impact of maritime piracy on seafarers’ behavioral health and work decisions. Mar Policy. 2018;87:23-28. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dohrman SB, Leppin A. Determinants of seafarers’ fatigue: a systematic review and quality assessment. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;90:30-37. doi: 10.1007/s00420-016-1174-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hystad S, EID J. Sleep and fatigue among seafarers: the role of environmental stressors, duration at sea, and psychological capital. Saf Health Work. 2016;7(4):363-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chowdhury SAA, Smih J, Trowsdale S, Leather S. HIV/AIDS, health and wellbeing study among International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) seafarer affiliates. Int Marit Health. 2016:67(1):42-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lefkowitz RY, Slade MD, Redlich CA. Rates and occupational characteristics of international seafarers with mental illness. Occup Med. 2019;69(4):279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lefkowitz RY, Slade MD. Seafarer Mental Health Study. ITF Seafarers Trust & Yale University; 2019:49-60. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pauksztat B, Grech M, Kitada M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on seafarers’ mental health and chronic fatigue: beneficial effects of onboard peer support, external support and Internet access. Mar Policy. 2022;137:104942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tang L, Abila S, Kitada M, Malecosio S, Jr, Montes K. Seafarers’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: an examination of current supportive measures and their perceived effectiveness. Mar Policy. 2022;145:105276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. International Labour Organization. Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), 2006. ILO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gekara VO, Sampson H. The World of the Seafarer: Qualitative Accounts of Working in the Global Shipping Industry. Springer; 2021. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/43276/2021_Book_TheWorldOfTheSeafarer.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization. User empowerment in mental health: A statement by the WHO Regional Office for Europe-empowerment is not a destination, but a journey. 2010. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/113834/E93430.pdf

- 17. Shearer NBG. Health empowerment theory as a guide for practice. Geriatr Nurs. 2009;30(2 Suppl):4-10. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitada M . Gender and work within the maritime sector. In: Wright T, Budd L, Ison S, eds. Women, Work and Transport. Emerald; 2022:229-248. doi: 10.1108/S2044-994120220000016015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Foucault M. Two lectures. In: Michael Kelly, ed. Critique and Power: Recasting the Foucault/Habermas Debate. MIT Press; 1994:17-46. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haugaard M. The Constitution of Power: A Theoretical Analysis of Power, Knowledge, and Structure. Manchester University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bin WU. Vulnerability of Chinese contract workers abroad. Discussion paper 32. 2008; China Policy Institute, China House, The University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maiman LA, Becker MH. The health belief model: origins and correlates in psychological theory. Health Educ Monog. 1974;2(4):336-353. [Google Scholar]

- 23. O’connor PJ, Martin B, Weeks CS, Ong L. Factors that influence young people’s mental health help-seeking behaviour: a study based on the Health Belief Model. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(11):2577-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haraway DJ. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Maritime University. Transport 2040: Automation, Technology, Employment - The Future of Work. London: World Maritime University; 2019. doi: 10.21677/itf.20190104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sampson H., Ellis N. Seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing. IOSH. https://iosh.com/media/6306/seafarers-mental-health-wellbeing-full-report.pdf.2019 (accessed December 8, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sampson H, Ellis N. The need for proactive employer investment in safeguarding seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing. Marit Policy Manag. 2021;48(8):1069-1081. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blackburn P. Mentally Healthy Ships: Policy and Practice to Promote Mental Health on Board. ISWAN; 2020. https://www.seafarerswelfare.org/seafarer-health-information-programme/good-mental-health/mentally-healthy-ships (accessed December 7, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brooks SK, Greenberg N. Mental health and psychological wellbeing of maritime personnel: a systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):1-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baygi F, Mohammadian Khonsari N, Agoushi A, Hassani Gelsefid S, Mahdavi Gorabi A, Qorbani M. Prevalence and associated factors of psychosocial distress among seafarers during COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qin W, Li L, Zhu D, Ju C, Bi P, Li S. Prevalence and risk factors of depression symptoms among Chinese seafarers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6): e048660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clayton R. Seafarer mental health is not just a pandemic panic. Lloyd’s List. Published October 11, 2021. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1138465/Seafarer-mental-health-is-not-just-a-pandemic-panic (accessed January 8, 2023).

- 33. Clayton R. Seafarer mental health issues on the rise, study finds. Lloyd’s List. Published March 08, 2021. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1136047/Seafarer-mental-health-issues-on-the-rise-study-finds (accessed December 18, 2022).

- 34. Pougnet R, Pougnet L, Dewitte JD, Lucas D, Loddé B. COVID-19 on cruise ships: preventive quarantine or abandonment of patients? Int Marit Health. 2020;71(2):147-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Devereux H, Wadsworth E. Forgotten keyworkers: the experiences of British seafarers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ Labour Relat Rev. 2022;33(2):272-289. doi: 10.1177/10353046221079136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hebbar AA, Mukesh N. COVID-19 and seafarers’ rights to shore leave, repatriation and medical assistance: a pilot study. Int Marit Health. 2020;71(4):217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bush D. Suicides at sea go uncounted as crew change crisis drags on. Lloyd’s List. Published February 22, 2021. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1135870/Suicides-at-sea-go-uncounted-as-crew-change-crisis-drags-on (accessed November 18, 2022).

- 38. Lloyd’s List. Crew abandonment cases increase 138% during pandemic. Published February 14, 2022. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1139848/Crew-abandonment-cases-increase-138-during-pandemic (accessed January 10, 2023).

- 39. Ramos C. Filipina cruise ship worker commits suicide while awaiting repatriation. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Published June 11, 2020. https://globalnation.inquirer.net/188383/filipina-cruise-ship-worker-commits-suicide-while-awaiting-repatriation. https://globalnation.inquirer.net/188383/filipina-cruise-ship-worker-commits-suicide-while-awaiting-repatriation (accessed January 8, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 40. McVeigh J, MacLachlan M, Cox H, et al. Effects of an on-board psychosocial programme on stress, resilience, and job satisfaction amongst a sample of merchant seafarers. Int Marit Health. 2021;74(4):268-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abila S. Minding the gap: Mental health education and Standards of Seafarers’ education. In: Senbursa N. ed. Handbook of Research on the Future of the Maritime Industry. IGI Publishing; 2022:69-90. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-9039-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Le Gac JM, Texier S. Training in the detection of psychological distress on board ships through health simulation during the COVID-19 epidemic. Int Marit Health. 2022;73(2):89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) and International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). Seafarers Workforce Report. The global demand and supply for seafarers 2021.BIMCO and International Chamber of Shipping; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baumler R, Bhatia B, Kitada M. Ship first: Seafarers’ adjustment of records on work and rest hours. Mar Policy. 2021;130: 104186. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kitada M. Women Seafarers and their Identities. Cardiff University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47. International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network. Social Interaction Matters - What works for seafarers onboard. Published April 01, 2021. https://www.seafarerswelfare.org/news/2021/social-interaction-matters-what-works-well-on-board (accessed January 14, 2023).

- 48. Papachristou A, Stantchev D, Theotokas I. The role of communication to the retention of seafarers in the profession. WMU J Marit Aff. 2015;14(1):159-176. doi: 10.1007/s13437-015-0085-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Robledo Yamamoto F, Voida A, Voida S. From therapy to teletherapy: relocating mental health services online. Proc ACM Human Comput Interact. 2021;5(CSCW2):1-30.36644216 [Google Scholar]