Available treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) result in a significant reduction in symptoms in only 30% of individuals. Residual symptoms frequently persist and relapses occur; this reality has propelled continued research on fear extinction mechanisms, and effective therapies for PTSD. One such advancement has been Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. Notwithstanding the risks of bias in consensus guidelines and the meta-analyses on which they are based, EMDR is described as equally effective as trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) and superior to stress management in the treatment of PTSD in the Canadian Clinical Guidelines put out by the Anxiety Disorders Association of Canada in 2014. Further, EMDR is a first-line recommended treatment, along with TF-CBT, in the National Institute of Care Excellence (NICE) and Australian and New Zealand treatment guidelines. During EMDR, patients are instructed to recall a traumatic memory while simultaneously orienting to alternating bilateral visual stimulation. EMDR appears to interfere with memory reconsolidation after traumatic memory recollection.

Pre-clinical work suggests the involvement of superior colliculus-mediodorsal thalamic-amygdalar pathways as potential neural substrates underlying clinical responses to EMDR. 1 Further, a growing body of research demonstrating an intersection between the oculomotor and hippocampal memory systems suggests that eye position might play a crucial role in this relation, and thus in EMDR therapy. 2 Eye fixations on the same spatial location(s) as when an item was learned appears to play an important role in its successful memory retrieval, though scan path (i.e., eye movement) is also critical. 3 Since EMDR was developed, various adaptations have emerged. These variants share common features: awareness of body sensations, imagination-based exposure, and visuo-motor attention.

BrainspottingTM (BSP) therapy, developed by David Grand in 2003, may be a particularly promising improvement of EMDR. A key difference is that BSP requires attentional control while attending to a specific “spot” within the visual field that is linked to heightened physical sensations while recollecting a traumatic memory. A small (N = 53) trial 4 demonstrated that just three BSP sessions were as effective as EDMR in treating PTSD symptoms (EMDR typically averages 8–12 sessions). Emerging data also suggests that BSP might be better tolerated by patients, easier for therapists to learn, and more easily integrated into other forms of trauma therapy owing to its flexibility and relatively short duration. Spurred by this encouraging data, we (J.T.) first implemented BSP therapy in one case, as outlined below:

M. was a 49-year-old male who witnessed mass killings during a civil war. He described severe PTSD symptoms and chronic headaches. Treatment with multiple medications, TF-CBT, and EMDR resulted in only modest symptom relief. During the first BSP session, however, M. accessed a forgotten memory of being beaten. This was accompanied by high-intensity arousal, fear, and a sudden onset of arm pain (same arm he remembered defending himself with). Six weeks later, M. reported that his chronic headaches had stopped. During four additional BSP sessions (1x/week), other forgotten memories gradually integrated in a way that allowed him to experience the trauma as an event firmly in the past, and to develop an alternate meaning to his experiences. After 5 BSP sessions, there was a substantial reduction in hyperarousal, intrusive memories, and avoidance.

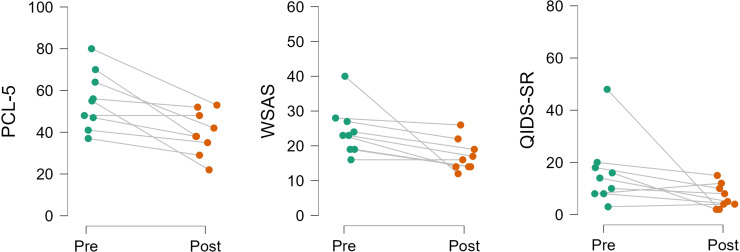

This client's compelling response propelled us to assess the effectiveness of six sessions of BSP in a pilot study of N = 9 patients with PTSD (referred to a general psychiatry practice; no change in medication as patients received BSP sessions). We noted a pronounced improvement in PTSD symptoms, daily functioning, and depression symptoms, as assessed using validated questionnaires (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Paired sample t-tests after six brainspotting (BSP) sessions showed a significant [t(8)=3.67, P = .006] drop in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms as measured by the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). There were also small improvements in levels of functioning as measured with the Work and Social Functioning (WSAS) scale [t(8)=2.65, P = .03] and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS; Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test: Z = −2.13, P = .03).

Following up on anecdotal data that BSP is more flexible and easier to learn than EMDR by therapists, in 2021, we conducted a survey of N = 112 therapists attending BSP training (all had EMDR experience and most were using BSP in therapy). A total of 82% of surveyed therapists reported that, on average, clients responded “better” or “much better” to BSP versus EMDR; 82% also reported that BSP versus EMDR integrated more easily into other treatment approaches. While acknowledging the biases of such self-report data and its limited generalizability, it is nevertheless informative as a recent meta-analysis of 26 trials indicated that the mean drop-out rate was substantially higher for trauma-focused (27%) versus non-trauma-focused (16%) treatments. 5 As such, directives for improving retention in trauma-focused treatments should be prioritized. Finally, most relevant to improving access-to-care, 72% of respondents reported that they felt more able to use BSP therapy after a “level 1” BSP training versus “level 1” EMDR training.

In sum, BSP is a variant of EMDR that may offer more flexibility, increased cost-effectiveness, and, ultimately lead to greater improvements in patient outcomes. The above summary of preliminary evidence for the potential utility and effectiveness of BSP is presented to help generate hypotheses that can be verified by randomized clinical trials. Future research assessing eye position and trauma memory reconsolidation and work focused on assessing the neuronal underpinnings of BSP might improve treatments available to those living with the sequelae of trauma-related effects.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Sara de la Salle https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1698-5938

Natalia Jaworska https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5643-8210

References

- 1.Baek J, Lee S, Cho T, et al. Neural circuits underlying a psychotherapeutic regimen for fear disorders. Nature. 2019;566(7744):339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan JD, Shen K, Liu ZX. The intersection between the oculomotor and hippocampal memory systems: empirical developments and clinical implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1464(1):115–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bochynska A, Laeng B. Tracking down the path of memory: eye scan paths facilitate retrieval of visuospatial information. Cogn Process. 2015;16(Suppl 1):159-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hildebrand A, Grand D, Stemmler M. Brainspotting—the efficacy of a new therapy approach for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in comparison to eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. Mediterr J Clin Psychol. 2017;5:1-17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards-Stewart A, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder treatment dropout among military and veteran populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34(4):808–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]