Abstract

Clinical interest into the function of tuft cells in human intestine has increased in recent years. However, no quantitative study has examined intestinal tuft cells in pathological specimens from patients. This study quantified tuft cell density by using a recently identified marker, specific for tyrosine phosphorylation (pY1798) of girdin (also known as CCDC88A or GIV) in the duodenum of pediatric patients. Deidentified sections with pathological diagnosis of acute duodenitis, ulcer, or celiac disease, and age-matched normal control were analyzed under double-blind conditions. Immunostaining for pY1798-girdin demonstrated the distinct shape of tuft cells with and filopodia-like basolateral membrane structure and a small apical area, which densely expressed gamma-actin. As compared to normal tissues, the specimens diagnosed as celiac disease and duodenal ulcer had significantly fewer tuft cell numbers. In contrast, acute duodenitis showed varied population of tuft cells. The mucosa with severe inflammation showed lower tuft cell numbers than the specimens with none to mild inflammation. These results suggest that loss of tuft cells may be involved in prolonged inflammation in the duodenal mucosa and disrupted mucosal integrity. pY1798-girdin and gamma-actin are useful markers for investigating the distribution and morphologies of human intestinal tuft cells under healthy and pathological conditions.

Tuft cells, also known as brush, caveolated, multivesicular, or fibrillovesicular cells, were morphologically identified in the 1950s through electron microscopy by their long, stiff microvilli and well-developed tubulovesicular system (8, 17). This rare population of cells is scattered in many organs, including airway, salivary gland, bile duct, and gastrointestinal epithelia. However, the functions of tuft cell in humans remain unclear. In mouse and rat gastrointestinal tissues, tuft cells are visualized by immunostaining for doublecortin-like protein kinase 1 (DCLK1), gustducin, TRPM5, PLCβ2, and cyclooxygenases, implicating sensory functions of these cells in monitoring the luminal environment (1, 5, 6, 10). In genetically engineered mouse studies, intestinal DCLK1 deficiency decreases epithelial cell proliferation and survival rate after mucosal injury, suggesting that tuft cells may promote stem cell activity and mucosal restitution (12, 19). Furthermore, mouse tuft cell numbers are increased and secretion of interleukin-25 is elevated in response to pathogen infection, suggesting that intestinal tuft cells take part in the type 2 immune response and may regulate adaptation against luminal microorganisms (4, 7, 18). We recently found that tuft cell differentiation was specifically inhibited in a congenital diarrheal disease model that is induced by myosin Vb deletion in mice (9). These observations in animal models suggest that the intestinal tuft cells serve an important role in regulation of mucosal integrity and the pathogenesis of diarrhea. Nevertheless, human tuft cells have not yet been studied as thoroughly as in the mouse. McKinley et al. reported the immunoreactivities for phosphorylated epidermal growth factor receptor (pEGFR) in human intestinal tuft cells (13). However, no quantitative study has examined intestinal tuft cells in pathological specimens from patients. Recently, specific tyrosine phosphorylation (pY1798) of girdin (also known as CCDC88A or GIV), which is an EGFR target, has been identified in human tuft cells (11). Using specific antibodies against pY1798-girdin, we have investigated alterations in the duodenal tuft cell population in different pathological conditions, including celiac disease, acute duodenitis, and duodenal ulcer. These diseases can present with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and malabsorption, and can cause failure to thrive in children.

Experiments were approved by the IRB committee for Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Archival paraffin-embedded diagnostic biopsy specimens from duodenum of pediatric patients (age mean ± SD, 11.7 ± 5.1 y, n = 32) were obtained from the Translational Pathology Shared Resource at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Deidentified sections with acute duodenitis, duodenal ulcer, or celiac disease, and age-matched normal tissues (control: age, 11.2 ± 4.7 y, n = 15) were analyzed under double-blind conditions. Severity of acute duodenitis was evaluated by a gastrointestinal pathologist (W.J.H). It was graded by neutrophilic infiltration into the epithelium and lamina propria: mild (less than 33% of the area), moderate (33–66% of the area), and severe (more than 66% of the area). Slides were deparaffinized, heated in a pressure cooker in Dako Target Retrieval Solution (S1699; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), pre-incubated with Protein Blocking solution (Dako), and stained with antibodies against human girdin (pY1798; 1 μg/mL; IBL America, Minneapolis, MN) and gamma actin (1 : 100; sc-65638, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) overnight. The slides were rinsed in PBS and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/mL: ThennoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and slides were cover-slipped with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (ThermoFisher Scientific).

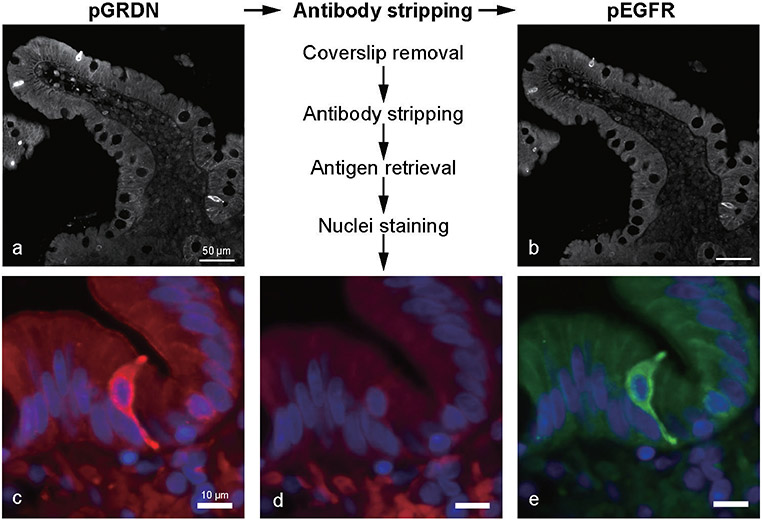

To investigate double-positive cells for pY1798-girdin (pGRDN) and pEGFR, the same sections were stained with rabbit anti-pEGFR antibody (1 : 500; ab40815; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) after the staining with rabbit anti-pY1798-girdin followed by antibody stripping (3). Antibodies were removed from the tissues by boiling the slides in Tris-HCl buffer containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.8% β-mercaptoethanol for 20 min. The tissue autofluorescence and the absence of prior staining signals were confirmed before each staining with primary antibodies. The slides were cover-slipped with 50% glycerol in 0.1 M PBS containing Hoechst 33342.

Immunofluorescence staining was visualized using a Nikon Ti-E microscope with an A1R laser scanning confocal system (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY), and whole slide images were scanned using a Leica/Aperio Versa 200 with 20× objective (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) for quantitative analysis. Mucosal area was determined by background fluorescence signal in Digital Image Hub (Leica), and pGRDN positive cell number was manually counted in Review software (Leica).

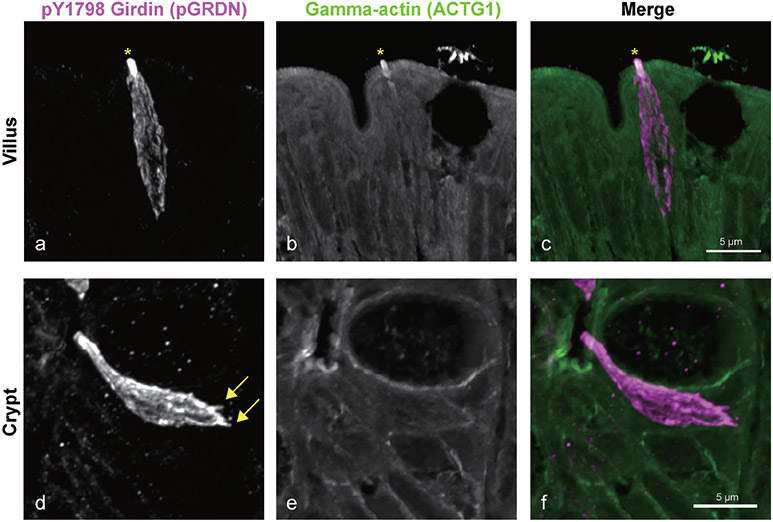

In patient biopsy sections, pY1798-girdin (pGRDN) antibodies strongly labeled distinct apical tuft and cell bodies of tuft cells in duodenal crypts and villi. Epithelial apical membrane in crypt and lower villus regions was weakly stained with pGRDN. Most of villus tuft cells were spindle shaped with a narrow basal cytoplasm and small apical membrane area, which densely expressed pGRDN and gamma-actin (ACTG1) (Fig. 1a-c). Immunoreactivities for ACTG1 were predominant in long microvilli, similar to the villin or fibular actin (F-actin) structure in mouse intestinal tuft cells (5, 6). To detect F-actin, a dyeconjugated phalloidin is most widely used, but this method does not work in paraffin sections. The ACTG1 antibodies can be a useful marker of complexed actin filaments in paraffin sections of human intestine. The long ACTG1-positive microvilli were not obvious in crypt tuft cells (Fig. 1e), indicating that gamma-actin accumulation is specific in mature tuft cells. Filopodia-like structures in the basal regions of cells were identified by pGRDN in some tuft cells (Fig. 1d), consistent with an interaction with other cells, such as neurons (15). Girdin is a multidomain signaling protein, which is encoded by CCDC88A, and binds to actin filaments triggering cell migration downstream of its tyrosine phosphorylation by EGFR (16). To compare the distribution of pGRDN and pEGFR, we performed multiplexed immunostaining on the same specimens. The results revealed that most tuft cells expressed both pGRDN and pEGFR in a similar distribution pattern (Fig. 2). The apparent coincidence of phosphorylation of girdin and EGFR in tuft cells indicates that EGFR ligands may activate the tuft cells.

Fig. 1.

Identification of duodenal tuft cells. z-stack confocal images of immunoreactivities for pY1798-girdin (pGRDN, a and d) and gamma-actin (ACTG1, b and e) in normal duodenal mucosa. pGRDN staining demonstrates the distinct shape of tuft cells with narrow apical area. Villus tuft cells demonstrate dense and long microvilli that consist of both pGRDN and ACTG1 (asterisk) (a–c). Tuft cells in crypt regions lack the dense gamma-actin structure. Filopodia-like structures are frequently identified in the basal part of tuft cells (arrows) (d–f).

Fig. 2.

Multiplexed immunostaining for pY1798-girdin (pGRDN) and pEGFR in the intestinal tuft cells. After staining with pGRDN antibody (a and c), the antibodies are stripped off, and the absence of fluorescence is conformed (d). The same sections are then stained with pEGFR antibody (b and e). Nuclei are counterstained every round of imaging (c–e, blue). Distribution of these two markers is mostly identical in the villi and crypts, as well as in the microvilli and long basal root-let of tuft cells.

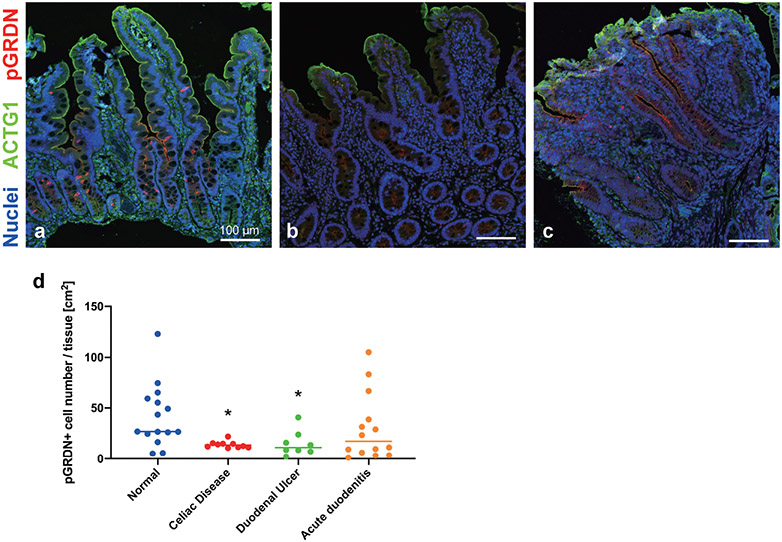

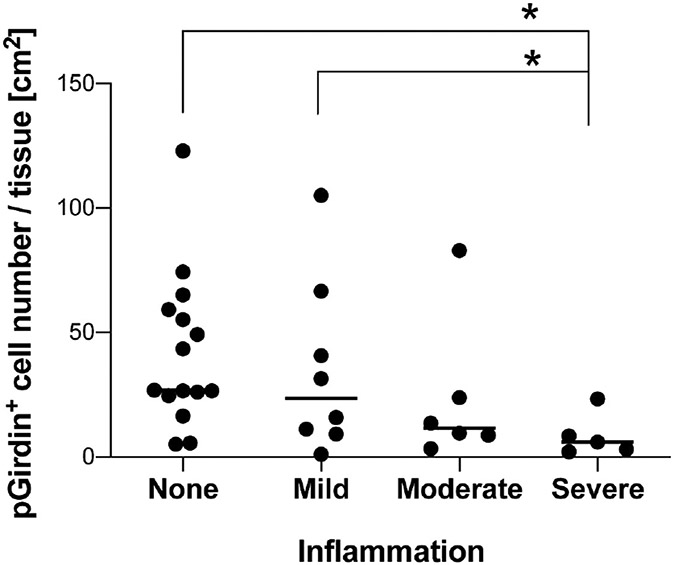

The frequency of pGRDN+ tuft cells was calculated per mucosal area in a variety of pediatric patients. Compared to normal tissues, the specimens diagnosed as celiac disease had significantly fewer tuft cell numbers (Fig. 3a, b, and d). Celiac disease is an autoimmune enteropathy, which shows an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes and/or villus blunting, resulting in malabsorption. Experimental helminth infection in early clinical trials suppresses inflammation in patients with celiac disease (2, 14). Mouse intestinal tuft cells are upregulated by helminth infection and activating type 2 immune response (18). While there is no report about the change in human tuft cell population under these infections, tuft cell maturation might be associated with mucosal healing. Patients with duodenal ulcers also demonstrated significantly lower tuft cell frequency than normal tissues (Fig. 3c and d). These observations indicate that the impaired differentiation of pGRDN+ tuft cells correlates with the pathology in the duodenal mucosa. In contrast, 6 of 14 patients with acute duodenitis showed higher tuft cell numbers, while the other 8 patients had fewer tuft cells when compared to the median value of normal specimens (Fig. 3d). We then graded the inflammation severity (mild, moderate, and severe) in the specimens without metaplasia based on the extent of neutrophil infiltration in the epithelium and lamina propria. Mucosa with severe inflammation demonstrated >75% decrease in tuft cell numbers as compared to specimens with no to mild inflammation (Fig. 4). Similar to our results, Gerbe et al. proposed the involvement of prostaglandin-producing tuft cells in the intestinal carcinogenesis, because immunoreactivities of hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase disappear in advanced adenocarcinoma as compared to early adenoma tissues (5). These observations suggest that the loss of differentiated tuft cells may be a result of prolonged inflammation in the duodenal mucosa. On the other hand, tuft cell hyperplasia might be an indicator of the active mucosal repair process involved in mucosal integrity. To clarify the relationship between inflammation status and tuft cells, further studies are needed to characterize accumulated neutrophils in each case.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of pY1798-girdin-positive (pGRDN+) tuft cells in duodenal specimens. a–c: Representative images of specimens diagnosed as normal (a), celiac disease (b), and duodenal ulcer (c). Whole-slide images of immunostaining for pGRDN (red), ACTG1 (green), and nuclei (blue) are scanned and analyzed. Compared to normal mucosa, specimens with celiac disease (b) or inflamed mucosa with duodenal ulcer (c) show fewer tuft cells. d: Tuft cell numbers are counted and calculated per mucosal area. *P < 0.05 vs. Normal by Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s test. Each datapoint indicates the average for each slide from one patient (n = 8–15 patients), including 1–8 specimens per patient. Bars indicate median of each group.

Fig. 4.

More severe inflammation is associated with tuft cell loss in specimens with duodenitis and/or ulcer. pGRDN+ cell numbers per mucosal area are calculated in duodenal biopsies with mild, moderate, or severe inflammation, and compared to that in not inflamed specimens (same as normal in Fig. 3). Each datapoint indicates the value of each slide from one patient (n = 5–15), and the bars indicate median of each group. *P < 0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s test.

Clinical interest into the function of intestinal tuft cells in human physiology and pathology has increased in recent years. However, a quantitative analysis had not been performed in human pathological specimens. In the present study, we demonstrate that pY1798-girdin and gamma-actin are useful tools to visualize the distinct morphologies of human tuft cells and to quantify their distribution. Tuft cell frequency was significantly decreased in celiac disease and ulceration, and tuft cell loss was correlated with inflammation severity. The population of intestinal tuft cells is likely influenced by mucosal inflammatory status and transient tuft cell hyperplasia might indicate mucosal repair responses in human enteropathy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to Professor James Goldenring in Vanderbilt University Medical Center for financial support (NIH grant R01 DK48370 and support from the Christine Volpe Foundation). This work was supported by core resources of the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Center (P30 DK058404), the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485), and imaging supported by the Vanderbilt Digital Histology Shared Resource (supported by a VA Shared Equipment Grant 1IS1BX003097).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bezencon C, le Coutre J and Damak S (2007) Taste-signaling proteins are coexpressed in solitary intestinal epithelial cells. Clieni Senses 32, 41–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming JO and Weinstock JV (2015) Clinical trials of helminth therapy in autoimmune diseases: rationale and findings. Parasite Immunol 37, 277–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gendusa R, Scalia CR, Buscone S and Cattoretti G (2014) Elution of high-affinity (>10-9 KD) antibodies from tissue sections: Clues to the molecular mechanism and use in sequential immunostaining. J Histochem Cytochem 62, 519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerbe F, Sidot E, Smyth DJ, Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, et al. (2016) Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature 529, 226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerbe F, van Es JH, Makrini L, Brulin B, Mellitzer G, et al. (2011) Distinct ATOH1 and Neurog3 requirements define tuft cells as a new secretory cell type in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol 192. 767–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofer D, Puschel B and Drenckhahn D (1996) Taste receptor-like cells in the rat gut identified by expression of alpha-gustducin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 6631–6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howitt MR, Lavoie S, Michaud M, Blum AM, Tran SV, et al. (2016) Tuft cells, taste-chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science 351, 1329–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarvi O and Keyrilainen O (1956) On the cellular structures of the epithelial invasions in the glandular stomach of mice caused by intramural application of 20-methylcholantren. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl 39, 72–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaji I, Roland JT, Engevik AC, Goldstein AE and Goldenring JR (2019) Lysophosphatidic acid treatment ameliorates the function of apical Sglt1, but does not prevent the formation of microvillus inclusions or loss of tuft cell differentiation in Myo5b deficient mice. Gastroenterology 156, S106–S107. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokrashvili Z, Mosinger B and Margolskee RF (2009) Taste signaling elements expressed in gut enteroendocrine cells regulate nutrient-responsive secretion of gut hormones. Am J Clin Nutr 90, 822s–825s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuga D, Ushida K, Mii S, Enomoto A, Asai N, et al. (2017) Tyrosine phosphorylation of an actin-binding protein girdin specifically marks tuft cells in human and mouse gut. J Histochem Cytochem 65, 347–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May R, Qu D, Weygant N, Chandrakesan P, Ali N, et al. (2014) Brief report: Dclk1 deletion in tuft cells results in impaired epithelial repair after radiation injury. Stem Cells 32, 822–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKinley ET, Sui Y, Al-Kofahi Y, Millis BA, Tyska MJ, et al. (2017) Optimized multiplex immunofluorescence single-cell analysis reveals tuft cell heterogeneity. JCI Insight 2, e93487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McSorley HJ, Gaze S, Daveson J, Jones D, Anderson RP, et al. (2011) Suppression of inflammatory immune responses in celiac disease by experimental hookworm infection. PloS one 6. e24092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morroni M, Cangiotti AM and Cinti S (2007) Brush cells in the human duodenojejunal junction: an ultrastructural study. J Anat 211, 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omori K, Asai M, Kuga D, Ushida K, Izuchi T, et al. (2015) Girdin is phosphorylated on tyrosine 1798 when associated with structures required for migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 458, 934–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodin J and Dalhamn T (1956) Electron microscopy of the tracheal ciliated mucosa in rat. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat 44, 345–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Moltke J, Ji M, Liang HE and Locksley RM (2016) Tuft-cell-derived IL-25 regulates an intestinal ILC2-epithelial response circuit. Nature 529, 221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westphalen CB, Asfaha S, Hayakawa Y, Takemoto Y, Lukin DJ, et al. (2014) Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. J Clin Invest 124, 1283–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]