Abstract

Purpose:

Little is known about factors affecting HIV care engagement and retention among rural people with HIV (PWH) in the South. About half of PWH in Arkansas reside in rural areas. The purpose of this study was to explore factors affecting engagement and retention in HIV care among PWH in rural areas of Arkansas.

Methods:

We conducted an exploratory qualitative study in 2020 and completed individual interviews (N = 11) with PWH in rural counties in Arkansas.

Findings:

Content analysis revealed the following themes: (1) Barriers to HIV care included long distances to the nearest HIV clinic and transportation issues along with anticipating and/or experiencing HIV-related stigma; (2) facilitators of HIV care included having a helpful HIV care provider and Ryan White case manager and a social support network that aided them in prioritizing their own health; (3) participants had the most favorable reactions to Ryan White case management, peer navigators, and telemedicine for HIV treatment/care; and (4) participants demonstrated resilience overcoming various obstacles as they worked toward being healthy mentally and physically while living with HIV.

Conclusion:

Interventions need to address multilevel factors, including hiring PWH as peer navigators and/or caseworkers and offering HIV care via telemedicine, to improve HIV care engagement and retention among rural populations.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, PLWHA, rural, HIV care, qualitative

INTRODUCTION

While the HIV epidemic in the United States is largely stable, the HIV incidence rate remains high in the Southern United States.1 Over half of new HIV diagnoses and people with HIV (PWH) lived in the South in 2019.2 Black/African American (B/AA) individuals remain disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and make up 50% of new HIV diagnoses in the South.2 Additionally, some other populations continue to be disproportionately affected, including gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), persons who inject drugs, transgender persons, and women.3 In fact, B/AA women make up 54% of new HIV cases among females despite being only 13% of the female population in the United States.3 Known contributors to the HIV/AIDS epidemic among particularly vulnerable populations include stigma,4 poor health care access,5 poor education,6 and poverty.7 These factors are prominent barriers to care in Arkansas as well.8,9

Arkansas is a southern state and one of the target areas defined by the “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America” (EtHE) due to its substantial rural HIV/AIDS burden and significant health care disparities.10 Estimated HIV incidence in Arkansas rose from 9.5 per 100,000 in 2018 to 13.1 per 100,000 in 2019.11 Over 40% of state residents live in rural areas,12 and nearly half of PWH in Arkansas live in rural areas.13 PWH in the South and rural areas have limited access to HIV care, when compared to PWH living in non-rural areas.10,14

Furthermore, evidence indicates rural residence is a risk factor for lower rates of HIV testing, delayed HIV diagnosis, later adoption of advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART), and consequently, increased HIV-related mortality.14 Also, rural residents with HIV infection often face challenges such as stigma, social isolation, long distances to care, limited transportation, and lack of access to providers with HIV expertise.14 However, additional research is needed to explore factors affecting HIV care engagement in rural areas, particularly in poor southern states such as Arkansas.

Significant gaps exist across the HIV care continuum in Arkansas, despite the efficacy of current treatment options. HIV testing in Arkansas lags behind the national average, with only 33.9% of residents reporting they had ever been tested for HIV in 2017.15 About 26% of PWH were newly diagnosed with stage 3 AIDS at their first diagnosis of HIV/AIDS in 2019.16 Additionally, over 80% of PWH in Arkansas are “out of care” (defined as not attending two HIV care visits within a 12-month period).17 Of those out of care, 40% are B/AA.17 A greater understanding of the factors PWH in Arkansas face is needed to inform interventions and to improve rates of HIV care engagement. Little is understood about barriers and opportunities for retaining rural people in HIV care in the Southern United States. This study’s purpose was to explore factors affecting engagement and retention in HIV care among PWH in rural areas of Arkansas, particularly those disproportionately affected by HIV (i.e., B/AA individuals, MSM, persons who inject drugs, transgender persons, and women).

METHODS

Recruitment

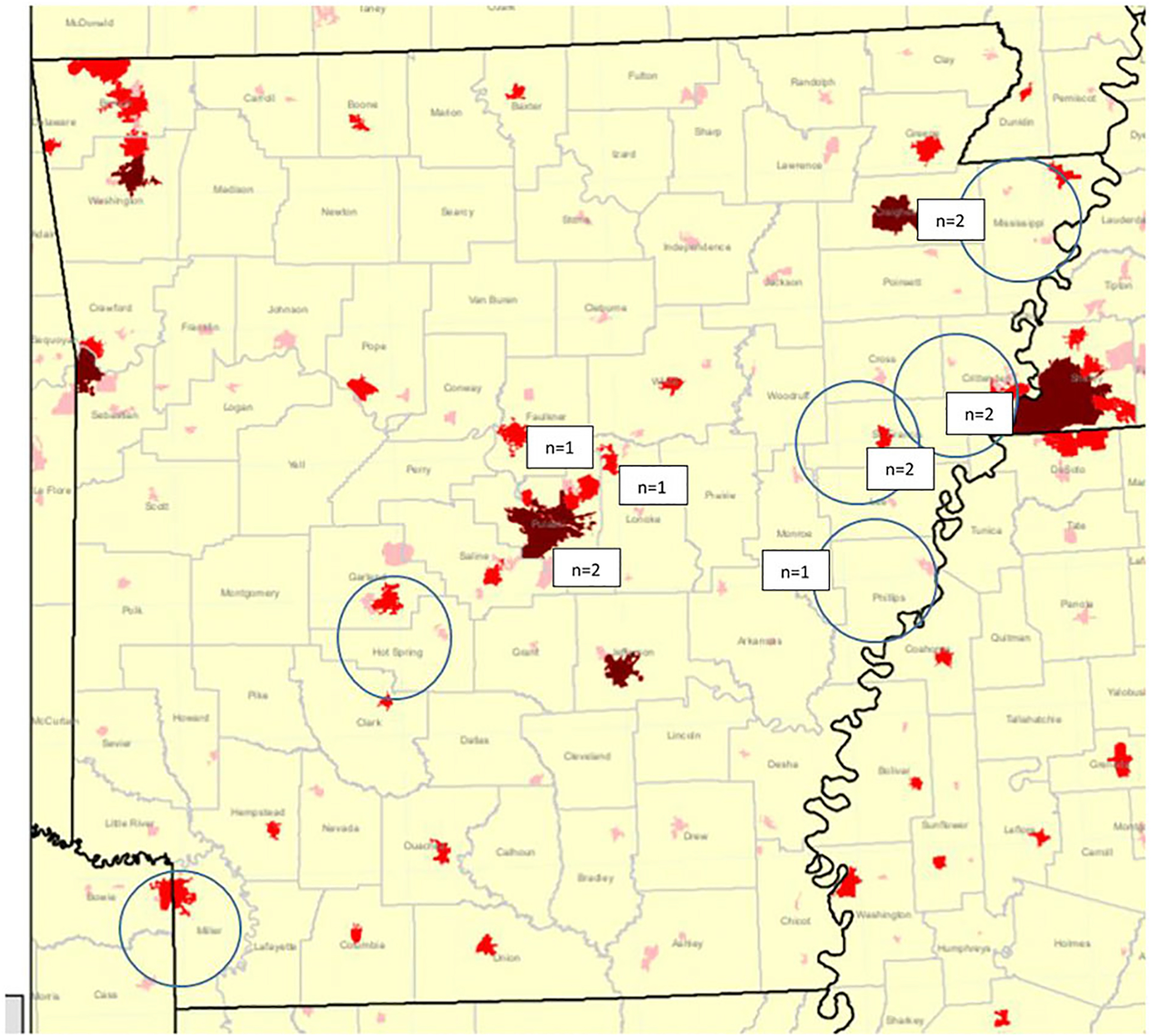

We recruited PWH who currently or previously resided in Arkansas counties with high rural HIV burden, including Mississippi, Hot Spring, Phillips, St. Francis, Crittenden, and Miller counties. (Note: The first four counties listed are eligible for rural health grants18 and are categorized as non-metro counties.19) Individuals were considered for inclusion in the study if they (a) were 18 years of age or older; (b) had a confirmed diagnosis of HIV; and (c) either currently or previously lived in or directly adjacent to the counties named (see Figure 1). The researchers used snowball sampling and a purposeful sampling strategy to capture the perspectives of vulnerable populations and those disproportionately affected by HIV (i.e., B/AA individuals, MSM, persons who inject drugs, transgender persons, and women).20–22 The researchers partnered with a community connector (i.e., a Black man with HIV) to help recruit participants. The community member had connections with PWH in several of the counties targeted for recruitment. Recruitment strategies, led by the community connector, included advertising on that person’s Facebook page and posting in a private Facebook group for PWH. Information about the study was primarily spread by word-of-mouth.

FIGURE 1.

Targeted “hot spots” and counties of interview participants. Note: The areas circled are the “hot spots” indicating rural areas with high HIV burden. The numbers indicate the number of participants and their approximate location by county of current residence

Procedure

Between January and August 2020, the researchers conducted semi-structured individual interviews. Participants verbally consented to the interview and self-reported demographic and health information through a survey completed at the time of the interview. Completion of the survey was facilitated by the interviewer. Interview questions addressed the following domains: (a) structural- and individual-level facilitators and barriers to access in HIV care; (b) the impact of HIV-related stigma on HIV testing and linkage to care; (c) structural- and individual-level facilitators and barriers to ART initiation and adherence; (d) obstacles to achieving viral suppression; (e) potential intervention components and related content to support engagement in HIV care; and (f) cultural nuances about HIV testing and engagement in the HIV care continuum. Interviews typically lasted 1 h. Initially, interviews occurred in person but after the first documented COVID-19 case in Arkansas in March 2020, interviews occurred over the phone. Enrollment continued until thematic saturation was reached. Each participant was compensated $50. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences approved the study.

Qualitative data analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded with verbal consent from the participants and transcribed by an outside HIPAA-certified transcription company and reviewed for accuracy by research staff. Interview data were coded by two independent raters using Dedoose.23 Qualitative data were analyzed iteratively during data collection using content analysis, frequently used by health researchers for interview data interpretation24 which allows classification of sections of interview passages into categories representing overarching themes.25 We performed both deductive and inductive coding26 to address any unanticipated, emerging themes. This method also allowed the researchers to determine when saturation was reached. We identified themes using a two-phase coding scheme following the basic procedures of grounded theory.20

RESULTS

Participants (N = 11) had an age range of 35–84 with a median age of 49 and mean age of 49.5. Two participants were cisgender men, eight were cisgender women, and one was a transgender woman. Eight identified as non-Hispanic Black/African American (72.7%) and three identified as non-Hispanic White (37.3%). Nine (81.8%) participants identified as straight/heterosexual and two identified as gay (18.2%). (Table 1 includes additional demographic data.)

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of interview participants (N = 11)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 11 | 100 |

| Race | ||

| Black or African American | 8 | 72.7 |

| White | 3 | 37.3 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight or heterosexual | 9 | 81.8 |

| Gay or homosexual | 2 | 18.2 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 5 | 45.5 |

| Not employed | 1 | 9.1 |

| Retired | 1 | 9.1 |

| Disabled | 4 | 36.4 |

| Highest educational level | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 4 | 36.4 |

| Some college | 5 | 45.5 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 | 9.1 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 1 | 9.1 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single and never married | 4 | 36.4 |

| Married or in a domestic partnership | 3 | 27.3 |

| Divorced | 4 | 36.4 |

All participants (100%) reported currently having health insurance and all (100%) reported currently taking medications for HIV and attending health care appointments for HIV multiple times per year. Participants’ year of HIV diagnosis ranged from 1996 to 2015. The average time that participants had been living with HIV is 15 years, and the median length of time was 19 years. Two (18.2 %) reported ever having injected drugs. Seven (63.6%) reported having a previous sex partner who was living with HIV.

Content analysis of the interviews revealed four themes. First, barriers to HIV care included long distances to the nearest HIV clinic and transportation issues (n = 7) as well as anticipating HIV-related stigma (n = 7) and/or not wanting to acknowledge their diagnosis (n = 10), which was dually captured by codes “fear of testing/knowing diagnosis.” Second, key facilitators of HIV care included having a helpful HIV care provider (n = 10), Ryan White case management services (n = 8), family support (n = 6), and having a positive mindset (n = 9) and prioritizing their health (n = 11). Third, all participants (n = 11) offered their reactions to and recommendations for HIV care engagement programs/interventions, and identified Ryan White case management and telemedicine/TelePrEP as favorable programs/services and suggested hiring more PWH. Lastly, most participants demonstrated resilience overcoming various obstacles as they worked toward becoming mentally and physically healthy while living with HIV; most did not feel that they currently experienced many major challenges in life or barriers to HIV care (n = 7) even if they had in the first year(s) of their diagnosis. Each of these themes is described along with brief, illustrative quotes. (Table 2 includes full quotes.) Where large portions of data were excluded from a quote to save space, this is indicated by nine dots [………].

TABLE 2.

Illustrative quotes from interview participants

| Theme with codes and subcodes | Quote |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Barriers to HIV care included long distances to the nearest HIV clinic and transportation issues as well as anticipating and/or experiencing HIV-related stigma. | |

| Code: Barriers to HIV care Subcode: transportation/travel distance |

|

|

|

|

|

| Code: Barriers to HIV care Subcodes: HIV related stigma, anticipating stigma |

|

| Code: HIV testing barriers Subcode: HIV related stigma |

|

| Codes: Barriers to HIV care; challenges in life Subcodes: HIV related stigma; experienced stigma |

|

|

|

| Codes: Barriers to HIV care; challenges in life; HIV testing barriers Subcode: Fear of testing; knowing diagnosis |

|

| Theme 2: Facilitators of HIV care included having a helpful HIV care provider and RyanWhite case manager and a social support network that aided them in prioritizing their own health. | |

| Code: Facilitators to HIV care Subcode: Helpful providers |

|

|

|

| Code: Facilitators to HIV care Subcode: Case managers |

|

|

|

|

|

| Code: Facilitators to HIV care Subcode: Helpful providers |

|

| Code: Facilitators to HIV care Subcode: Prioritizing health |

|

| Code: Facilitators to HIV care Subcode: Support system |

|

|

|

|

|

| Theme 3: Regarding programs or services, participants had the most favorable reactions to Ryan White case management, peer navigators, and telemedicine for HIV treatment/care. | |

| Code: Reactions to programs/services Subcodes: Positive reactions; Ryan White |

|

| Code: Reactions to programs/services Subcodes: Positive reactions; negative reactions; Ryan White |

|

| Codes: Reactions to programs/services; program recommendations Subcodes: Negative reactions; Ryan White; peer navigators; hiring PWH |

|

|

|

| Code: Program recommendations Subcodes: peer navigators; hiring PWH |

|

|

|

|

|

| Code: Telemedicine/TelePrEP |

|

|

|

|

|

| Theme 4: Most participants demonstrated resilience overcoming various obstacles as they worked towards being healthy mentally and physically while living with HIV. | |

| Code: Challenges in life Subcode: optimistic/positive outlook on life |

|

| Code: Challenges in life Subcode: Health care challenges |

|

| Code: Challenges in life |

|

| Code: Challenges in life Subcode: optimistic/positive outlook on life |

|

|

|

Theme 1: Barriers to HIV care included long distances to the nearest HIV clinic and transportation issues as well as anticipating and/or experiencing HIV-related stigma.

While all interview participants were engaged in HIV care at the time of the interviews, and reported few current barriers to HIV care, many talked about challenges they, or others in their communities, had previously experienced including travel distance to HIV care, HIV-related stigma, and limited HIV provider options. When asked about any challenges to HIV care, many participants spoke about past issues, and they had either addressed them or accepted them as part of their HIV care routine. For instance, one participant said, “Probably the distance to get to the doctor and to…my caseworkers” (Participant #6, 35 years old, White cisgender woman) was an issue she had encountered. While this participant sometimes struggled to make a 40-min drive to and from her appointments, she also mentioned she recently moved and was going to have to identify another provider. She anticipated potentially having to drive even farther but remained optimistic. Yet another participant said, “I had terrible transportation. . … It was very hard at first. …A lot of times I had to walk……… They started helping me… It got a little easier on me…” (Participant #4, 52 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Some participants described travel distance as a manageable part of their care but talked about how it is a current barrier for other people. One participant said, “Well, by me staying here in [county name], there’s no doctors here……… as long as I got transportation, I’m fine. Maybe another person may not…” (Participant #1, 50 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Regarding another potential barrier to HIV care, one participant discussed the way anticipating/expecting stigma prompted her to seek HIV care in another town. She said, “I wasn’t ready for people to know. Because I didn’t want to be judged or stigmatized” (Participant #9, 51 years old, Black cisgender woman).

While participants mentioned issues that affect their HIV care access, they also mentioned factors perceived to affect HIV testing in their communities. One participant explained how anticipating stigma discourages people from taking an HIV test. “If somebody sees you go in to get an HIV test, then they’re going to assume that you have HIV…” (Participant #10, 46 years old, Black cisgender woman).

In addition to describing anticipating stigma, other participants described actual experiences of stigma. One participant described herself as having a positive outlook on life but also reported that experiencing HIV-related stigma was the main challenge in her life. She said, “Being so strong as an advocate I still have some, not necessarily shame, but fear of stigma” (Participant #6, White cisgender woman). Another participant recounted a neighbor in an apartment complex who told other people about her HIV status: “…my son, he’d be outside, sometimes he would hear little kids say, ‘She got AIDS. The lady downstairs says she’s got AIDS,’ …it went on for a long time till [the neighbor] finally moved…” (Participant #3, 49 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Yet another participant initially struggled with denial about her HIV diagnosis, which created a barrier to her seeking treatment at first. She said, “I guess the only challenge was the denial process. That was my biggest challenge. Because I was in denial that it was even happening” (Participant #5, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman). Once this same participant accepted her diagnosis, sought assistance from a local social service agency and sought counsel at her church, where she encountered discrimination and experienced stigma, just as she had feared, and thus, she could understand why others may anticipate stigma and not seek testing or confirm their HIV diagnosis. Therefore, HIV-related stigma—whether experienced or anticipated/perceived—was a barrier reported by most participants preventing either HIV testing or seeking HIV care, particularly during the time immediately following diagnosis.

Theme 2: Facilitators of HIV care included having a helpful HIV care provider and Ryan White case manager and a social support network that aided them in prioritizing their own health.

Many participants discussed their HIV medical providers and support staff, including Ryan White case managers, as being important facilitators to their HIV care. Some participants talked about the importance of their ability to discuss issues with their doctor. One participant said “My HIV doctor he’s very straight to the point. I feel confident in asking him any kind of question, I get a straightforward answer” (Participant #6, 35 years old, White cisgender woman). One participant explained the role of his medical team saying: “You’re looking at a person that probably shouldn’t be even on the Earth …but somehow……… My doctor meets me with open arms” (Participant #2, 84 years old, Black cisgender man).

Another participant described being connected to his Ryan White case manager and support staff directly after release from incarceration. He said “Anytime I have a problem, I just call her and she’ll get it straightened out. I couldn’t ask for a better case worker” (Participant #7, 39 years old, White cisgender man). One participant said, “I have a great case manager… I have a personal relationship with her … I’m not going to lie when I say this: I rely on her” (Participant #8, 50 years old, White transgender woman). Similarly, another participant explained, “I have a case worker……… helps remind me of my doctor’s appointment, and they’re there at the appointment with me…so, that’s a big help” (Participant #5, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Another participant described personal attention she received from her medical providers “…even when I would miss an appointment they made sure, ‘[Participant’s name], are you coming,’ or ‘you didn’t come; are you okay?’…” (Participant #9, 51 years old, Black cisgender woman). While most participants recounted only positive experiences with current HIV doctors and Ryan White case managers, some participants provided more nuanced perspectives. Two participants described overt stigma experienced from previous medical providers, which prompted them to seek health care elsewhere (going from a rurally located clinic to an urban one).

Additionally, several participants indicated that they had strong support networks and prioritized their health, and thus, they were motivated to adhere to their HIV treatment plan. For instance, one participant said, “I think it’s just best that I focus on work, my family, and my health. Health being my number one…” (Participant #8, 50 years old, White transgender woman).

Another participant described how acceptance from family was important to her own self-acceptance after receiving her diagnosis. She explained, “I was worried … that I couldn’t touch and kiss, and hug them like I usually do, but they never changed and that made me feel…accepted” (Participant #9, 51 years old, Black cisgender woman).

While none of the participants described experiencing stigma currently based on their HIV status from friends or family (although several experienced it from other sources), at least one mentioned the burden of hiding their diagnosis, and some participants mentioned keeping their diagnosis private from children, particular family members, or friends. Their fear of disclosure appeared linked to anticipating stigma if they disclosed their HIV status.

Several participants talked about the role of their support networks and other strategies they used to maintain their health and well-being. One participant talked about the importance of her social support network to help her through times of depression. For her, this support network included her doctor, her church, and her family. She said, “……… I find that talking to people and praying changes things. It helps. It really helped me” (Participant #4, 52 years old, Black cisgender woman). Another participant shared this about her support system and acknowledged that not everyone who is living with HIV/AIDS has one. “Oh, I have some really good friends… Then, my family is really, really supportive. ……… Because I have that support system, it makes it a little easier for me. But not everyone has that” (Participant #5, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Theme 3: Regarding programs or services, participants had the most favorable reactions to Ryan White case management, peer navigators, and telemedicine for HIV treatment/care.

Participants offered their reactions to and recommendations for a number of HIV care engagement programs and services. One common thread that was shared by these particular programs or services (e.g., Ryan White case management, peer navigators, and telemedicine for HIV treatment/car) is how they facilitated access and helped people overcome real or perceived barriers to HIV-related care.

One participant applauded the Ryan White program and his case-worker when they said, “I mean, the Ryan White program, that’s the greatest thing I’ve ever heard!” (Participant #7, 39 years old, White cisgender man). However, other participants had mixed feelings about Ryan White case management based on their experiences. One participant reacted this way: “Some have been good; some have been not so good” (Participant #6, 35 years old, White cisgender woman).

Another participant said this: “I think the Ryan White case management is a great idea. The way it’s been handled in the state I think is problematic. …they need to maybe invest in hiring people who are already HIV positive…” (Participant #10, 46 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Yet another participant said, “If more people were concerned about HIV, it would be a better program” (Participant #2, 84 years old, Black cisgender man). Another participant added, “Some people will appreciate the fact of having somebody that understands and knows what they’re going through” (Participant #5, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman). Several participants shared that sentiment.

Again, in order to have more buy-in and support from caseworkers, some participants believed it to be important to hire people who were also living with HIV themselves. Notably, this idea emerged from several of the interview participants as a suggestion and was not a program or service included in the interview prompt. The idea of hiring more people living with HIV in case management roles was also recommended by one participant who said, “If you’re positive, then there should be somebody available immediately to talk to that person, and I think we need to use more positive people” (Participant #11, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman). This same participant also highlighted the value of connecting with a newly diagnosed person and being able to show them that their diagnosis “is not the end of the world.” Another participant described it this way:

Because I remember when I was newly diagnosed, even though I did seek care faster than

some people……… Some people do take a little while, but … if they know that

they can meet a person that can understand where they’ve been or where they are right

now, ……… I think that would be a benefit…

(Participant #5, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman)

Another way to facilitate HIV care engagement beyond having effective, caring case managers is to meet people where they are. One participant recommended telemedicine by saying, “I think it’ll be great” (Participant #4, 52 years old, Black cisgender woman). Another participant shared: “I think telemedicine, it would be just the most awesome thing in the world!” (Participant #5, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Another participant when asked about their reactions to telemedicine said, “I think telemedicine and TelePrEP are great new innovations because they can reach the hard to reach clients and it cuts down time that people have to take off from work” (Participant #10, 46 years old, Black cisgender woman). Similarly, another participant shared this feeling that telemedicine visits would be more accommodating, “…because most of us are working class people” (Participant #11, 44 years old, Black cisgender woman). In sum, telemedicine/TelePrEP was believed to facilitate access to HIV treatment and preventive care and was believed to be innovative and accommodating, which made this service very appealing.

Theme 4: Most participants demonstrated resilience overcoming various obstacles as they worked toward being healthy mentally and physically while living with HIV.

Many participants described challenges faced earlier in their HIV diagnosis and explained the ways in which their lives were different now. When asked about any challenges they had experienced, one participant revealed her adaptability (an indicator of resilience) and shared, “… I’m the type of person where if I’m faced with a challenge, I like to meet it head on…I’m focusing more on me and my health as opposed to in my past…” (Participant #8, 50 years old, White transgender woman).

Some participants talked about challenges they had experienced around comorbidities. One participant recounted the challenge of addressing her initial HIV diagnosis and a heart condition simultaneously. She said, “I think me being sick with my heart, it tripled my HIV…” (Participant #3, 49 years old, Black cisgender woman).

One participant happily reported no challenges from their current HIV care, and talked about more routine concerns like trying to eat healthy and adjusting to life now that she is an “empty nester” (Participant #4, 52 years old, Black cisgender woman). When asked about challenges in life, another participant mentioned the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on her mental health and well-being, and she said, “…because one of the things I realized was I’ve never lived alone in my 46 years…” (Participant #10, 46 years old, Black cisgender woman).

Additionally, most participants had positive things to say about their lives in general. One participant said, “I don’t live a really exciting life, but it’s fulfilling for me” (Participant #9, 51 years old, Black cisgender woman). When asked how life was going for them generally, another participant said, “Oh, it’s going great. My kids, they don’t know the situation [referring to the HIV diagnosis], but they’re in my life. I got a fiancé. I got a job. I have a place to live…” (Participant #7, 39 years old, White cisgender man).

To summarize, when asked to describe how life was going in general or to describe any challenges they experienced, most participants talked about physical or mental health challenges they had previously experienced and presented them as obstacles they had overcome, demonstrating resilience in their health and well-being. Furthermore, many participants currently had a favorable outlook on life overall despite living with HIV in rural Arkansas. Plus, several participants described feelings of fulfillment even if their lives seemed rather simple or unexciting.

DISCUSSION

This study identified six “hot spots” which were mostly rural counties with a high HIV burden. From these areas, the research team recruited 11 PWH and interviewed them about their experiences seeking HIV care. Our study findings provide insight into the lived experiences of individuals who are representative of special populations vulnerable to HIV and have been disproportionately affected by HIV. Notably, the most common themes identified were as follows: (1) previous or perceived barriers to HIV care included long distances to the nearest HIV clinic and transportation issues as well as anticipating and/or experiencing HIV-related stigma; (2) facilitators of HIV care included having a helpful HIV care provider and Ryan White case manager and a social support network that aided them in prioritizing their own health; (3) regarding programs or services, participants had the most favorable reactions to Ryan White case management, peer navigators, and telemedicine for HIV treatment/care; and (4) most participants demonstrated resilience overcoming various obstacles as they worked toward being healthy mentally and physically while living with HIV. These themes have some similarities but are rather different from the lived experiences shared by rural PWH in a Midwestern state, in particular how they viewed HIV diagnosis as a death sentence, whereas our PWH seemed to be able to speak from a more optimistic outlook.27

Notably, all participants reported being engaged in medical care and having an undetectable viral load, with few current barriers to their continued engagement in care. Therefore, they are among the 20% minority of rural Arkansans living with HIV who are engaged in medical care, but they can offer valuable insight into the factors leading to their retention in HIV care.13 Furthermore, although most of our participants reported no major health care challenges at the time of the interview, many spoke of their trouble initiating or maintaining HIV care in the past. Structural factors such as long distances to the nearest HIV clinic and access to reliable transportation frequently posed barriers to care; factors that have been presented by other researchers,14 yet remain as barriers to HIV care for PWH in this rural southern state. Participants talked about multiple strategies they had used to overcome these obstacles over time while living with HIV (e.g., walking long distances, taking unreliable bus rides, moving to live closer to preferred providers, and receiving assistance from case management and other community members). Most participants were able to address distance and/or transportation barriers by obtaining a personal vehicle or through wraparound services such as transportation assistance and peer support. These facilitating factors appear instrumental for retention in care among this sample, and future interventions should continue to incorporate these programs/services.

Participants also frequently talked about the value of their support networks and having an optimistic outlook (or positive mindset) as facilitators of their HIV care engagement. Being optimistic and being adaptable to challenges are indicators of resilience.28 These study participants demonstrated resilience and spoke about known key factors that contribute to how well individuals adapt to challenges, such as having a support system.28 These findings highlight the importance of assisting newly diagnosed individuals in building their resilience to ensure engagement and retention in HIV care. Future research studies may want to test the effectiveness of educational strategies, such as internalized stigma reduction strategies, among individuals newly diagnosed with HIV. Additionally, researchers may want to test an intervention that trains peer health educators and/or case managers (who are also PWH) in motivational interviewing techniques to facilitate retention in HIV care.

HIV stigma, both internalized and anticipated/perceived in the community, particularly related to the fear of disclosure, remains a significant barrier to HIV testing and treatment in their communities as highlighted in other research studies.14,27,29 Some participants also spoke about the stigmatization experienced or impersonal care delivered by some health care providers. Conversely, many participants discussed finding helpful medical providers and support staff as being instrumental to their successful retention in care. Thus, interpersonal factors in clinical settings, in the form of interactions with providers and staff, appear instrumental in HIV care engagement and have the potential to promote retention in care and meaningfully improve patient satisfaction with care. A stigma reduction strategy may be helpful and could be disseminated through rural clinics to reach the communities like those where our participants were located. Participants also recommended hiring PWH as caseworkers because they could relate to newly diagnosed individuals and compassionately work with them to connect them to health care providers and support services. Having this shared, lived experience may also buoy the spirit of HIV caseworkers who require resiliency and perform HIV advocacy constantly.30 Telemedicine for HIV care or case management may be a delivery strategy that appeals to PWH, especially newly diagnosed individuals, who may be uncomfortable going in-person to their initial appointments. Studies examining experiences of telemedicine for HIV care among PWH in urban areas early in the COVID19 pandemic reveal promise but identify concerns that must be addressed for sustainable use.31,32 Future research likely involves testing an intervention that includes telemedicine and/or peer support as strategies to facilitate HIV care engagement examining dual outcomes of treatment initiation and care retention among rural PWH. Based on a recent scoping review of peer support for PWH, research on the topic has increased in the last decade and yet gaps in evidence warrant continued study.33

Limitations

Our study consisted of a small sample of PWH in rural Arkansas. All of the participants in this study were notably actively engaged in HIV care and adherent to their medications. In addition, these individuals mentioned possessing several protective factors including a social support network and an optimistic mindset, and we did not have as many individuals participating in our study from some demographic subgroups disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS (e.g., Black MSM) in order for our findings to be representative of the total population of PWH in Arkansas. Thus, these features of our participants may present a bias in our findings. Due the sample size alone, the findings are not generalizable. Nonetheless, they do provide valuable insight and nuance to our understanding of the lived experiences of PWH in rural Arkansas, particularly highlighting what is needed to support HIV care engagement and retention for PWH.

CONCLUSIONS

These qualitative findings revealed perceived barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in HIV care among a sample of PWH in rural Arkansas. These findings suggest that an intervention package with outreach programs and support services, including hiring PWH as peer navigators and/or case managers as well as offering HIV care via telemedicine, could be promising to engage/re-engage PWH in HIV care, to retain them in care, and to help curb the rural HIV epidemic, particularly in Arkansas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There were no additional contributors to the manuscript other than the individuals identified as authors. This study was funded by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853). A portion of the time spent on the study described was also supported by the Arkansas Center for Health Disparities (ARCHD) grant [5U54MD002329] through the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2020;26(1). Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/incidence.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2020. HIV Surveillance Report. 2022;33. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/diagnoses.html [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. HIV surveillance report, 2020. 2022;33. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-33/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. “Triply cursed”: racism, homo-phobia, and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence, and disclosure among young Black gay men. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(6):710–722. 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorell CG, Sutton MY, Oster AM, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in health care settings among young African American men who have sex with men: implications for the HIV epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(11):657–664. 10.1089/apc.2011.0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S39–S45. 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reif SS, Whetten K, Wilson ER, et al. HIV/AIDS in the Southern USA: a disproportionate epidemic. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):351–359. 10.1080/09540121.2013.824535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham TH, McBain SA, Goudie A et al. “It’s been like a miracle”: low-income Arkansans and access to health care services following Medicaid reform. INQUIRY. 2020;57. 10.1177/0046958020981169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Population Review. Poverty rate by state. 2022. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/poverty-rate-by-state

- 10.CDC. HIV in the Southern United States, issue brief. 2019. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf

- 11.CDC National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention AtlasPlus. 2021. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas/index.htm

- 12.Arkansas-Rural Definitions: State-Level Maps. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53180/25558_AR.pdf?v=0

- 13.Author J, Author SA. Using a big-data approach to characterize disparities in the HIV care continuum and viral suppression among rural communities in Arkansas. 2020 National Ryan White Virtual Conference. 2020. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://targethiv.org/sites/default/files/RWNC2020/15901_Tao.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schafer KR, Albrecht H, Dillingham R, et al. The continuum of HIV care in rural communities in the United States and Canada: what is known and future research directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(1):35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS): graph of current HIV-AIDS testing among adults. 2019. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://chronicdata.cdc.gov/Behavioral-Risk-Factors/BRFSS-Graph-of-Current-HIV-AIDS-testing-among-adul/gbdh-6xcr

- 16.Arkansas Department of Health. 2019 Arkansas HIV surveillance report. 2020. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/images/uploads/pdf/2019_HIV_Surveillance_Reports.pdf

- 17.2017–2021 Integrated HIV Prevention and Care Plan Statewide Coordinated Statement of Need. 2016. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/images/uploads/pdf/AR_Integrated_HIV_Prevention_and_Care_Coordinated_Plan.pdf

- 18.HRSA. Rural health grants eligibility analyzer. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/rural-health

- 19.USDA. Rural-urban continuum codes. 2020. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Procedures and Techniques for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson J The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and issues. Nurse Res. 2004;12(1):84–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. Dedoose Version 8.0.35, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. 2018. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.dedoose.com/resources/articledetail/dedoose-desktop-app

- 24.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuendorf K The Content Analysis Guidebook. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens C, Voorheis E, Struble N, et al. A community-based study of clients’ lived experiences of going through the rural HIV care continuum. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2021;20(1):33–57. 10.1080/15381501.2021.1906819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychological Association. Resilience. 2022. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience

- 29.Hubach R, Dodge B, Schick V, et al. Experiences of HIV-positive gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men residing in relatively rural areas. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(7):795–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owens C, Vooheis E, Lester JN, et al. The lived experiences of rural HIV social workers. AIDS Care. 2021:1–5. 10.1080/09540121.2021.1981817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galaviz KI, Shah NS, Gutierrez M, et al. Patient experiences with telemedicine for HIV care during the first COVID-19 wave in Atlanta, Georgia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2022;38(5):415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harsono D, Deng Y, Chung S, et al. Experiences with telemedicine for HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(6):2099–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Øgård-Repål A, Berg RC, Fossum M. A scoping review of the empirical literature on peer support for people living with HIV. J Int Assoc Providers AIDS Care. 2021;20. 10.1177/23259582211066401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]