Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death worldwide and display complex phenotypic heterogeneity caused by many convergent processes, including interactions between genetic variation and environmental factors. Despite the identification of a large number of associated genes and genetic loci, the precise mechanisms by which these genes systematically influence the phenotypic heterogeneity of CVD is not well understood. In addition to DNA sequence, understanding the molecular mechanisms of CVD requires data from other omics levels, including the epigenome, the transcriptome, the proteome, as well as the metabolome. Recent advances in multi-omics technologies have opened new precision medicine opportunities beyond genomics that can guide precise diagnosis and personalized treatment. At the same time, network medicine has emerged as an interdisciplinary field that integrates systems biology and network science in order to focus on the interactions among biological components in health and disease, providing an unbiased framework through which to integrate systematically these multi-omics data. In this review, we briefly present such multi-omics technologies, including bulk omics and single-cell omics technologies, and discuss how they can contribute to precision medicine. We then highlight network medicine-based integration of multi-omics data for precision medicine and therapeutics in CVD. We also include a discussion of current challenges, potential limitations, and future directions in the study of CVD using multi-omics network medicine approaches.

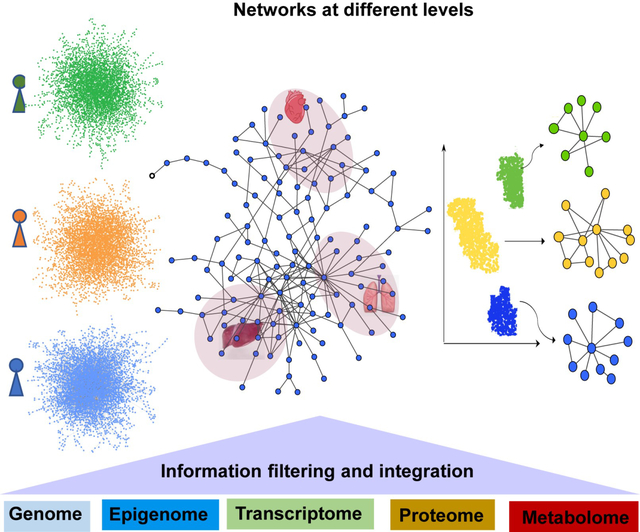

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are caused by a combination of behavioral risk factors, genetic variation, and environmental differences [1]. Despite recent advances in effective therapies that have improved cardiovascular outcomes, CVD remain the leading cause of mortality globally. CVD are complex states displaying heterogeneity at the genotype, endophenotype, and clinical phenotype levels that cannot be fully elucidated by conventional reductionism [2]. Traditional experimental methods focus on specific targets and rarely explore systems context. A deep understanding of CVD (or any other disease) requires investigation of many biological levels such as the genome, the epigenome, the transcriptome, the proteome, and the metabolome, which are collectively denoted ‘omics’. Bulk and single-cell omics technologies allow one to investigate multiple targets simultaneously in an efficient manner by offering unbiased high-throughput approaches and have generated omics data for many diseases, including CVD, providing an unprecedent opportunity for the development of true precision medicine and therapeutics [3].

While each level of omics data has individual advantages and characterizes a specific feature of a disease, each only provides a limited perspective that is often insufficient to describe the entirety of pathological processes needed to understand the underlying causes of complex human diseases. Multi-omics integrates the analysis of multiple data sets from different omics layers, which can, in turn, be used to identify mechanisms of action, pathways, biomarkers, and other relationships present in pathological processes [4]. While a wealth of omics data for CVD has been accumulated over the last two decades, how best to integrate and utilize these multi-omics datasets is an emerging opportunity and challenge.

Many computational methods have been developed to integrate these different omics data sets, such as Bayesian integration approaches [4], graph-linked embedding [5], and machine learning [6]. Network medicine is an emerging interdisciplinary field that uses methods and tools from network science in order to identify disease pathways and repurpose effective drugs [7]. It provides an unbiased framework through which to integrate large-scale multi-omics data systematically and enhance our understanding of disease mechanisms. The power of multi-omics network medicine approaches lies in emphasizing, identifying, and dissecting disease heterogeneity in a population, rather than applying conventional reductionism and focusing on the most prevalent phenotype or genetic variant. The ultimate goal of these approaches is to guide tailored drug treatments and precision medicine by deciphering the phenotypic heterogeneity of human diseases.

Bulk and single-cell omics approaches

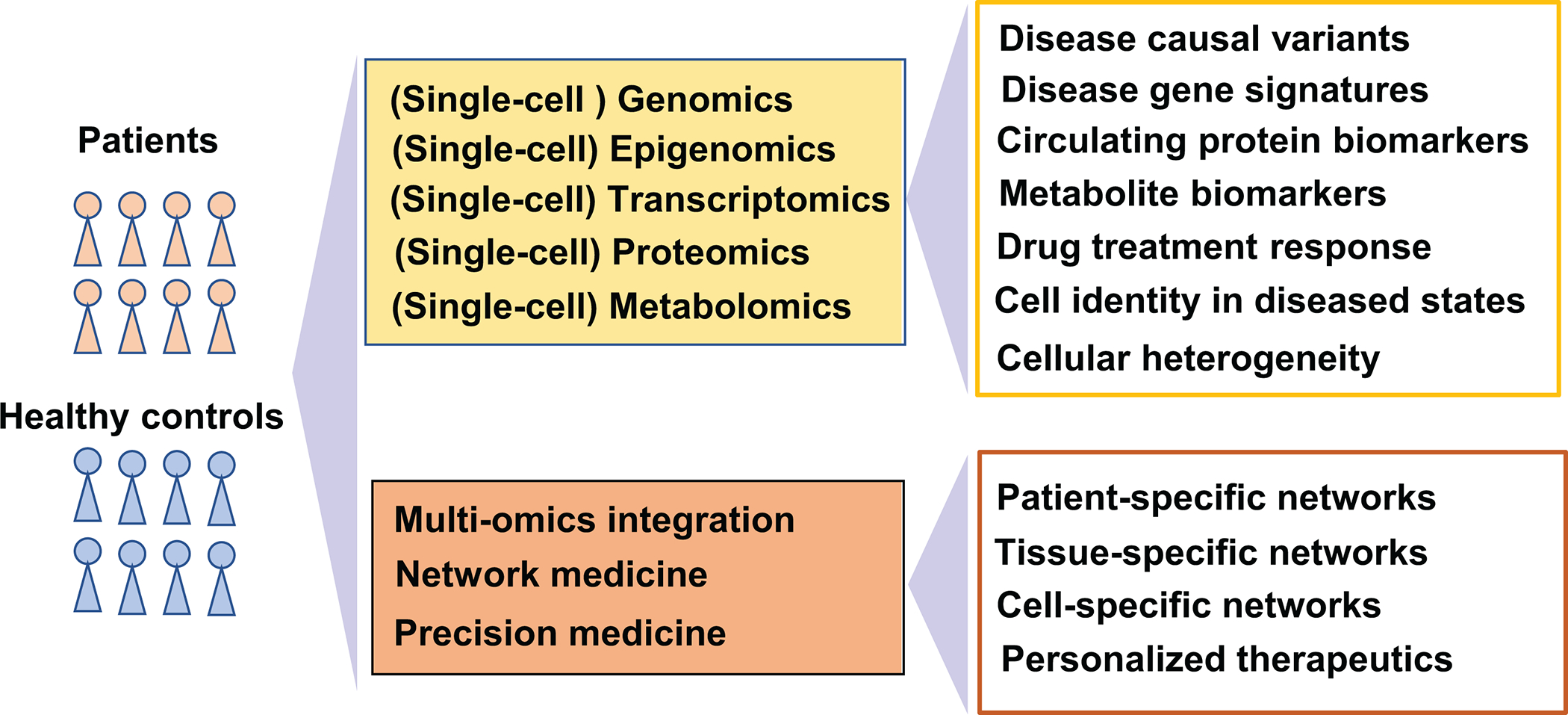

After sequencing the human genome, the post-genomic era began and inspired the development of other omics technologies, including epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics (Figure 1). Next-generation sequencing technologies, which determine the sequence of a given nucleic acid strand with ultra-high scalability and speed, drove the post-genomic era into a newer stage--- omics-based precision medicine of which cardiovascular research has taken advantage, as well. Nevertheless, data generated by these omics technologies are average measurements on bulk populations of cells, which, by its very nature, may cause the loss of information on cell type-specific changes, especially if those changes are modest or involve a small percentage of the total cell population. Single-cell omics technologies generate measurements from individual cells and provide a high-resolution picture of biologically complex, heterogeneous systems. Recent advances in single-cell technologies offer an unprecedented opportunity to dissect this heterogeneity of CVD at a single-cell level.

Figure 1. Bulk and single-cell omics data types and their applications in human diseases.

Genomics

Genomics, the study of an organism’s entire genome, is the most mature omics. Whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) analyses have been widely utilized to identify potential pathogenic or causative variants in different CVD which directly contribute to improved understanding of the underlying pathobiology. For example, three pathogenic-segregating variants were identified by a WES analysis of patients with familial congenital heart disease [8]. Another WES analysis of 83 patients with idiopathic or familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) prioritized variants for 247 genes [9]. A rare variant analysis of 4,241 pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) cases with exome or genome sequencing data identified a few rare de novo variants in PAH [10].

In addition to rare pathogenic variants, common causative genetic variations for CVD can be discovered through a genome-wide association study (GWAS) when the patient cohort is adequately sized for robust statistical analysis. For example, a large-scale meta-analysis of 48 GWASs confirmed most of the known coronary artery disease (CAD)-associated loci and also identified 10 new loci [11]. More recently, genetic loci for CAD were further enriched by GWAS analyses of the UK biobank data [12] and the Japan biobank data [13]. Novel genetic factors associated with idiopathic and familial PAH in the absence of BMPR2 mutations have been identified in a GWAS based on two independent case-control studies [14].

Single-cell genomics is the study of the genome of a cell using single-cell sequencing technologies, which provides genetic insights at cellular resolution. Single-cell genomics allows the accurate detection of genomic variants, clonal decomposition, and DNA replication states in single cells (e.g., genetic mosaicism) [15]. Through single-cell whole-genome sequencing of wild-type and mutational states of individual disease cells, cell-to-cell structural variation that contributes to the origins of phenotypic and evolutionary diversity can be discovered [16].

Epigenomics

Epigenomics is the study of the complete set of epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA regulation of the genome. Epigenetics is conceptually highly relevant to CVD, which display multigenic complexity and environmental modulation. Epigenetic modifications can be measured through DNA methylation analysis, DNA–protein interaction analysis, and chromatin accessibility analysis using sequencing-based techniques, such as ATAC-Seq. These analyses can discover epigenetic biomarkers for early CVD diagnosis and treatment response prediction [17]. For example, an epigenome-wide association study using DNA methylation analysis of incident CVD blood samples in two independent cohorts was performed and two epigenetic modules highly enriched with immune-related processes were found to correlate with CVD risk [18]. The cause–effect relationship between DNA methylation changes in these module genes and CVD risk needs to be further determined.

Single-cell epigenomics is an omics technology that allows one to assess epigenetic heterogeneity across cells through single-cell bisulfite sequencing and single-cell chromatin accessibility profiling [19]. Single-cell epigenomics has the potential to be applied to the diagnosis and prognosis of CVD, where epigenetic profiles may inform genetic biomarkers, knowledge of disease evolution and response to treatment. For example, to investigate cell-specific patterns of cis-regulatory elements and interpret CAD-relevant noncoding genetic variation, single-nucleus chromatin accessibility profiling of human atherosclerotic lesions was performed using scATAC-seq, and five major cell types were identified. CAD-associated genetic variants were found to be particularly enriched in endothelial and smooth muscle cell–specific open chromatin [20]. Putative target genes and candidate regulatory elements for known CAD loci from GWAS can be prioritized based on single-cell coaccessibility and cis-expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) information. Recently, coupled with GWAS, single-cell genomics enabled prioritization of risk variants and genes in single cells obtained from human hearts and identified putative causal variants at 122 atrial fibrillation-associated loci [21]. These studies illustrate a general framework for integration of single-cell epigenomics with GWAS to reveal relative the contributions of distinct cell types to diseases and identify genes likely to be associated with complex traits.

Transcriptomics

Next generation sequencing technologies have also revolutionized transcriptomics analysis. RNA-seq uses deep-sequencing technologies to profile the entire transcriptome and provides a far more precise measurement of levels of transcripts than conventional microarray methodologies [22]. RNA-seq analysis has been widely used to identify gene expression signatures for CVD. For example, an RNA-seq-based whole-transcriptome profiling of human cardiac tissue from healthy controls and patients with different types of cardiomyopathies revealed novel determinants and regulatory networks in nonfailing and failing human hearts [23]. As a complement to GWAS, transcriptome-wide association studies that leverage the effects of multiple cis-eQTL variants on gene expression can also identify gene-trait associations and discover novel susceptibility genes, as well [24]. Whole-blood transcriptomic profiles of idiopathic and heritable PAH identified a model of 25 genes distinguished PAH with 87% accuracy [25]. Transcriptome signatures identified through transcriptomic analysis can distinguish disease states and shed light on underlying dysregulated pathways in CVD that go well beyond simple GWAS which can only identify variants associated with a pathophenotype without regard for levels of tissue expression and its consequences for function. Of course, a limitation of this approach is the need ideally for determining the transcriptome in the involved tissue, which limits are broad applicability and, equally important, the potential for monitoring changes in the transcriptome over time.

Transcriptomic data can also be utilized to discovery drug targets and distinguish patients’ treatment responses, an important step towards personalized therapeutics. For example, in a recent study, Takeuchi and colleagues investigated the transcriptomic response to different types of antihypertensive drugs in the heart and kidney [26]. Similarly, a transcriptomic biomarker to predict therapeutic response to beta-blocker therapy in heart failure was discovered through comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of molecular pathways in endomyocardial biopsies that are affected by beta-blocking agents [27].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is by far the most widely used single-cell technology and in a relatively short period has had a transformative effect on biomedical research, including cardiovascular medicine [28]. scRNA-seq enables the profiling of the transcriptomes of single cells at unprecedented resolution and throughput; it has been used to uncover cellular heterogeneity to facilitate the identification of cell types and cell-specific biomarkers in the heart and vasculature that are most relevant to disease states, offering a path forward for cell type-targeted intervention in CVD. For example, a human cardiac cell atlas was created through analyses of large-scale single-cell transcriptomics of six adult hearts, and the cellular heterogeneity of cardiomyocytes, pericytes, and fibroblasts was revealed [29]. In a very recent study, extensive molecular alterations in failing hearts at single-cell resolution have been identified through single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) of nuclei in left ventricular samples from hearts with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), as well as non-failing hearts [30]. Reichart and colleagues performed scRNA-seq on cardiac samples from healthy controls and patients with cardiomyopathies with or without known genetic causes and identified 10 major cell types and biological signaling pathways associated with the pathophenotype [31]. In addition, scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq analyses of left ventricular cardiac tissue from health donors and DCM patients revealed cell composition of the healthy and failing human heart and cell-specific transcriptional signatures [32]. The ventricular cell atlases created in these studies are valuable data resources for investigating DCM and HCM.

In addition to DCM and HCM, single-cell transcriptomics also helps to uncover the mechanisms of other CVD. For example, Hill and colleagues performed snRNA-seq on nuclei from control hearts and hearts from patients with CHD and identified CHD-specific cell states and signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes [33]. In addition, single-cell transcriptomics enables the identification of a large number of novel dynamic eQTL in individual cells, which provides new insight into the gene regulatory changes that occur among heterogeneous cell types during cardiomyocyte differentiation [34]. Recent comprehensive reviews on scRNA-seq in CVD provide additional information for interested readers [35].

Spatial transcriptomics is a recent groundbreaking profiling method that allows one to measure the transcripts of a gene at distinct spatial locations in a tissue sample and, thereby, capture the positional context of transcriptional activity. Recently, a spatial multi-omics map of myocardial infarction was created using single-cell gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and spatial transcriptomic profiling of multiple physiological zones at distinct time points in myocardial infarction [36]. By describing changes in the transcriptome and epigenome that are associated with different processes and identifying disease-specific cardiac cell states of major cell types, this map reveals novel insights into late-stage myocardial infarction pathobiology. As an effort of the Human Cell Atlas project, a high-resolution single cell-type map of human tissues has been created through single-cell transcriptomics analysis combined with spatial antibody-based protein profiling [37].

Proteomics

Characterization of all ascertainable proteins in the human proteome in cells, tissues, or the circulation provides an even richer source of knowledge and offers the potential for a transformative impact on cardiovascular health and disease [38]. A quantitative protein map of the complete human organism, including 32 normal tissues, has been developed as a valuable data resource for discovering tissue-specific disease protein signatures [39]. As with transcriptomics, proteomics can identify predictive protein biomarkers and dysregulated biological pathways of CVD. For example, numerous circulating protein biomarkers for CVD were ascertained via a discovery proteomic platform that targeted proteins in blood plasma samples from 3,523 Framingham Heart Study participants [40]. In a retrospective study, a comprehensive set of 157 cardiovascular and inflammatory protein biomarkers from circulating plasma were evaluated for their possible association with cardiovascular death using proximity extension assays in patients with chronic coronary heart disease (CHD) [41].

Quantitative proteomics also offers the possibility of prioritizing risk biomarkers and therapeutic targets for complex human diseases, including CVD. Recently, circulating protein levels of 90 cardiovascular biomarkers were investigated for those associated with incident heart failure using affinity-based proteomic assays [42]. Among the 44 circulating proteins that were associated with incident heart failure, 8 had causal relationships with mechanisms of heart failure and 7 were druggable. In another retrospective study, proximity extension assays were used to perform targeted proteomics of whole blood sera from patients with different stages of heart failure; distinct proteomic signatures during treatment were found for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and correlated with severity [43].

Single-cell proteomics enables more parameters to be measured at a higher resolution and reveals wide variation in protein levels in different cells [44]. For example, in order to reveal specific characteristics of dysregulated immune cells within atherosclerotic lesions that may lead to different clinical events, Fernandez and colleagues performed single-cell proteomic and transcriptomic analyses of T cells and macrophages in carotid artery plaques of patients with or without clinically symptomatic disease, and identified specific features of innate and adaptive immune cells in plaques that are associated with cerebrovascular events [45], features that could not have been identified using bulk proteomics or transcriptomics. This type of analysis can, therefore, provide valuable insights into the design of more precisely tailored cardiovascular immunotherapies.

Spatially cell-resolved proteome changes can be revealed by image analysis of cellular phenotypes combined with single-cell ultra-high-sensitivity mass spectrometry [46]. Single-cell proteomics also has great potential as a drug discovery platform through analysis of drug response at cellular resolution [47]. Although single-cell proteomics is not yet as widely used as single-cell transcriptomics in CVD owing to its relatively underdeveloped stage, it can provide many opportunities for future cardiovascular research.

Metabolomics

Metabolomics is the large-scale measurement of low-molecular-weight metabolites in a cell, tissue, biofluid, or organism. It represents a powerful tool for measuring the changes in both global and cardiac-specific metabolism that occur across different disease states [48]. Similar to transcriptomics and proteomics, metabolomics has contributed to identification of new CVD biomarkers at another omics level—that of direct effector. For example, in a population-based study, 141 metabolites were analyzed to find circulating metabolite biomarkers associated with incident CHD using a targeted approach in serum samples from 10,741 individuals [49]. Five phosphatidylcholines were significantly associated with the risk of incident CHD and demonstrated comparable prognostic value as classic risk factors.

Metabolomics has played a vital part in drug discovery and precision medicine, as well, through the development of personalized phenotyping and individualized drug-response monitoring [50]. In a recent study, comprehensive serum metabolomics and gut microbiome data were analyzed for 199 patients with acute coronary syndrome [51]. Interestingly, this study demonstrated that metabolic deviations in the patients compared with controls were patient-specific with respect to their potential genetic or environmental origin and correlated with cardiovascular outcomes. This study proves the utility of the serum metabolome in understanding the basis of molecular heterogeneity in cardiovascular disease, highlighting the power of metabolomics for precision medicine.

Single-cell metabolomics is a relatively new yet potentially very powerful omics technology; it gives a snapshot of small molecules, intermediates, and products of cellular metabolism and allows the characterization of the biochemical content within a cell [52]. With the rapid development of various techniques, this cutting-edge omics tool has discovered many key factors regulating tumor metabolism in cancer [53]. CVD share many common risk factors and pathogenesis with cancer, as, for example, the existence of aerobic glycolysis in normal human endothelial cells. There is no doubt that single-cell metabolomics will play a vital role in identifying cell-specific metabolic biomarkers and predicting drug responses at the metabolic level and, thereby, contribute to precision medicine for CVD.

Network medicine-based integration of multi-omics data

With the wider availability of multi–omics platforms as we described in the last section, reconciling information across these omics and other biological data sets has emerged as a contemporary goal defining the field of big data and cardiovascular medicine [54]. The importance of pursuing analyses that facilitate convergence of orthogonal data sets is rooted in several observations. For example, the precision of any individual omics data output hinges, in part, on the methods and analytical tools used to interpret the results. Read-alignment algorithm selection has important implications for transcript detection and read quantification [22], while aptamer- or antibody-based platforms provide high-throughput but semi-quantitative results [55] compared to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry [56]. Additionally, most omics data represent a snapshot of system relationships, which necessitates inference on the interrelatedness of gene expression profiles, may include transient changes in transcriptional or proteomic programs of unclear functional relevance, and do not readily account for dynamic flux in these biological systems [57]. Innovative methods that converge biological data, in turn, are well-positioned to optimize the specificity of data outputs and in so doing boost confidence in the conclusion that a particular molecular pathway is functional and pathogenic.

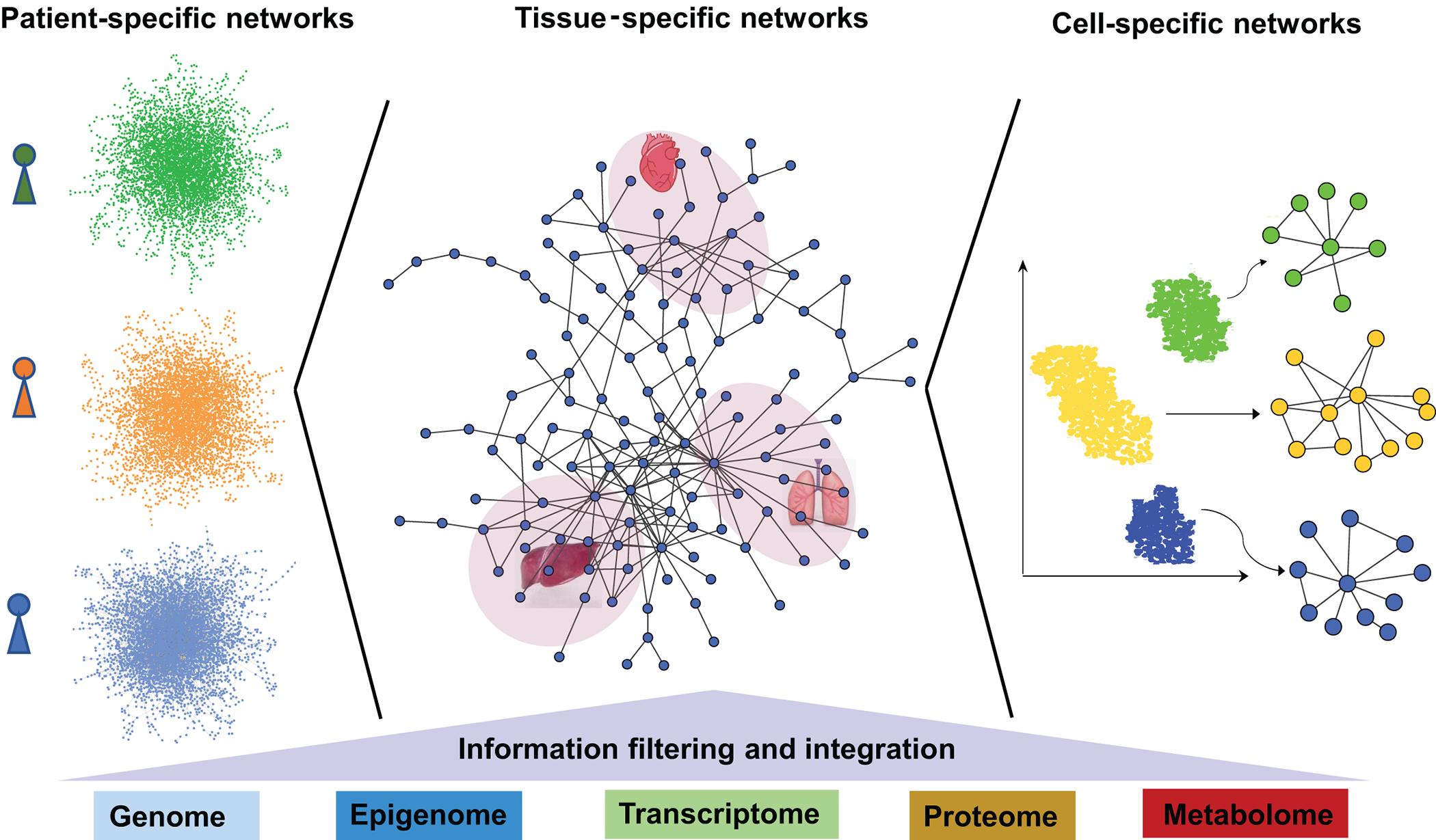

Network medicine is an interdisciplinary field that utilizes or adapts tools from network science to understand, prevent, and treat diseases [7]. Network medicine approaches, deploying the human protein-protein interactome and other biological networks, have been successfully applied to identifying disease pathways and deciphering the relationships among drugs, their targets and diseases. Importantly, network medicine provides an unbiased framework for systematically integrating multi-omics data at different biological levels to enhance precision medicine and therapeutics for CVD [58]. In this section, we highlight examples of network medicine-based integration covering a wide spectrum from the patient-level to the single-cell level (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Network integration of multi-omics data across a wide spectrum from the patient level to the single-cell level.

Patient-level omics data, tissue-specific omics data, and cell-specific omics data can be mapped to the human interactome to derive patient-specific networks, tissue-specific networks, and cell-specific networks. Such integrated networks are quite powerful for resolving the phenotypic heterogeneity in human diseases and guiding precise drug treatments.

Common types of biological networks

In complex cellular systems, biological components, such as genes, proteins, and metabolites, do not function alone. Instead, they often interact with each other across spatial and temporal scales and form different types of biological networks. A biological network is a graphic representation of binary interactions between various biological entities, where nodes are biological components and edges represent the interactions [59]. Transcriptional regulatory networks illustrate transcription factor-gene binding relationships which can be determined by Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-Seq). Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks consist of physical interactions, i.e., physical binding between proteins discovered through yeast two-hybrid screening or mass spectrometry. A signaling transduction network is a complex set of signaling pathways through which the cell converts one kind of signal to another. Metabolic networks display biochemical reactions in a cell. While these four types of networks represent direct interactions between biological entities, there are two additional types of networks that display indirect relationships between genes: gene co-expression networks show coordinated expression patterns across a group of genes constructed from transcriptomic data, and genetic interaction networks represent the functional interactions between pairs of genes and are useful for deciphering the relation between genotype and phenotype. Emerging tools in systems biology and network medicine can be used to analyze these networks and provide a comprehensive, holistic view of cellular systems.

Patient-specific networks integrating omics data

Characterizing monogenic variants in patients with complex cardiovascular pathophenotypes has advanced knowledge on fundamental mechanisms of HCM [60], pulmonary arterial hypertension [61], and Marfan syndrome [62], among other cardiovascular pathophenotypes. Incomplete penetrance [63] and wide phenotypic heterogeneity among patient cohorts that harbor the same purportedly pathogenic genotype [64], however, underscores the importance of implementing refined approaches to understanding the relevance of patient-level genetic data and omics context. This issue gains particular importance as variability in steady-state mRNA levels is reported across systems defined by alterations in the variant type and loci of the same gene [65].

Our group recently studied paired genetic and transcriptomic data from obstructive HCM patients referred for myectomy to treat symptomatic heart failure [66]. When focusing on 17 putative HCM-causing genes [67], we observed that the gene expression profile varied substantially between patients, implying an unpredictable genotype-mRNA relationship in HCM. We assembled patient-specific PPI networks derived from myectomy RNA-seq outputs and human protein interactome, and mapped HCM-causing genes to these networks. Interestingly, we determined that <0.1% of all PPIs involved these genes [68]. By contrast, network features, such as the prevalence of fibrosis pathways in each individual network, correlated strongly with phenotypic parameters and prognostic clinical variables, such as cardiac output and pulmonary vascular resistance. In this regard, interfacing genotype with functional PPI data (derived from affected tissue) contextualized the contribution of individual gene variant(s) to the wider molecular milieu underpinning patient-level phenotype. This study demonstrated that network integration of transcriptomic data enables identification of personalized biological mechanisms and offers a direct strategy for precision health care and prevention strategies.

Tissue-specific networks

Tissues and cells are the basic core of human biology and diseases. Modern omics technologies facilitate the creation of many human cross-tissue cell atlases, providing unprecedented resources towards systematically revealing tissue-specific features of human diseases [69]. Combined with broader network approaches, these data can generate tissue-specific networks that enable the identification of tissue-specific gene regulation and perturbation responses. For example, tissue-specific PPI networks were constructed through Bayesian integration of transcriptomic data from diverse experiments spanning tissue and disease states [70]. Mapping significant genes from GWAS to tissue-specific networks facilitates the identification of disease-gene associations more accurately than GWAS alone. In a recent study, tissue-specific gene co-expression networks were constructed through genome-wide transcriptomic analysis on tissue samples from the heart and other metabolically active tissues. Analysis of these networks revealed tissue-specific metabolic crosstalk after myocardial infarction and highlighted both common and specific biological responses to MI across a wide range of tissues [71]. Such tissue-specific networks facilitate identification of tissue-specific drug targets as a guide to tissue-specific drug delivery strategies.

Cell-specific networks

Accumulation of single-cell omics data expands the application areas of network medicine and systems biology to the cellular level to generate various types of single-cell biological networks. Some useful methods have been developed for constructing single-cell networks recently. A statistical model was developed to construct cell-specific gene coexpression networks from scRNA-seq data based on the statistical dependency of a pair of genes among single cells [72]. This method was further generalized to preserve cell-level network heterogeneity by retaining the networks from the statistical dependency of gene pairs [73]. Single-cell network medicine approaches are powerful for resolving cellular heterogeneity of human diseases at a systems level, and, as a result, have great potential for driving precision medicine. For example, cis-regulatory elements have been defined in the four cardiac chambers at single-cell resolution, and candidate transcription factors associated with cardiac cell types have been discovered spatially during the development of heart failure [74]. This atlas of human cardiac cis-regulatory elements provides the foundation for constructing cell type–specific gene regulatory networks in human hearts in health and disease. Single-cell network approaches can aid in drug repositioning, as well. Cell-specific gene regulatory networks for four major brain cell types were constructed by integrating single-cell multi-omics datasets from control and Alzheimer disease brains and cell type-specific candidate drugs were identified through drug-disease-module association analysis [75]. These studies demonstrate the wide-ranging opportunities that cell-specific networks will create for precision medicine in CVD. A rapid paradigm shift toward single-cell network medicine can be envisioned in the near future [76].

Other network medicine integration approaches

Similarity network fusion (SNF) incorporates multiple layers of omics data to form an individualized composite profile, which may then be compared to other patients for the purpose of identifying patient clusters [77]. Integrating mRNA, DNA methylation, and miRNA data using SNF in samples from patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction effectively identified unique subgroups defined by variable survival [78]. Talukdar and colleagues used a similar approach to define regulatory networks across different tissue types that are important in CAD [79]. They performed a gene co-expression network analysis that was based on topological overlap matrix visualization of tissue-specific expression profiles. Linear and non-linear relationships between co-expression network data with biochemical (e.g., plasma cholesterol, HbA1c, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, etc.) and clinical (e.g., coronary artery angiographic features) parameters that are important to CAD were used to establish module-phenotype associations. Functional genetics, emphasizing localization of eQTLs to CAD modules, was then used to explore causality with further interrogation of data output using Bayesian analytics and validation experiments, and led to the recognition of the importance of THP-1 foam cells in affected patients.

Recently, a few other platforms for multi-omics network integration have been developed. OmicsNet 2.0 accepts list inputs from common omics types, including genes, proteins, transcription factors, miRNAs, metabolites, and SNPs which are used as ‘seeds’ to search for interacting partners in compatible databases and to generate a heterogeneous network [80]. PaintOmics 4 is an updated web server for the integrative analysis and visualization of multi-omics datasets using biological pathway maps from major pathway databases [81]. Mergeomics 2.0 is an online tool for integrating multi-omics disease association data to derive essential regulators of disease-associated pathways and networks [82]. NeDRex is an interactive network medicine platform for disease module identification and drug repurposing through a heterogeneous biological network constructed by integrating data from multiple biomedical databases and gene expression data [83]. These multi-omics network medicine platforms are useful in identifying putative biomarkers and key drivers in translational cardiovascular research.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

In this review, we briefly present bulk omics, single-cell omics technologies, and network-based integration of multi-omics with applications to CVD. Multi-omics network medicine approaches present tremendous opportunities for systematic characterization of cardiovascular heterogeneity in health and disease, and will continue to play an important, expanding role in the development of cardiovascular medicine. The power of these approaches lies in emphasizing, identifying, and dissecting heterogeneity, rather than applying the conventional strategy of suppressing biological noise and focusing on the most prevalent phenotype or genetic variant in an otherwise quite heterogeneous population. The ultimate goal of multi-omics network medicine approaches is to use integrated information for deciphering the heterogeneity of human diseases and guide tailored drug treatments and precision medicine [84].

There are some potential challenges and limitations in multi-omics network medicine approaches. Network-based integration of multi-omics depends on the human protein-protein interactome which is currently incomplete. In addition, with the advances in chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) techniques for genome-wide profiling of DNA-binding proteins, it would be extremely useful to build a genome-wide human gene-regulatory network parallel to the human protein-protein interactome for network medicine. Ideally, a multilayer biological molecular network composed of genome-wide gene regulations, proteome-scale protein-protein interactions, spatial metabolic interactions, and biological coupling between them reflects the true molecular interactome essential for a complete understanding of human diseases [85].

Highlights.

The post-genomic era inspired the development of other omics technologies, including epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, at both bulk and single-cell levels.

Cardiovascular diseases are complex states displaying heterogeneity at the genotype, endophenotype, and clinical phenotype levels that can only be fully elucidated by investigation of multiple biological levels.

Network medicine provides an unbiased framework for systematically integrating multi-omics data at different biological levels to enhance precision medicine and therapeutics for cardiovascular diseases.

The power of multi-omics network medicine approaches lies in emphasizing, identifying, and dissecting cardiovascular heterogeneity in health and disease and guiding tailored drug treatments and precision medicine.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Stephanie C. Tribuna for expert secretarial assistance.

Sources of funding

This work was supported, in part, by NIH grants HL155107, HL155096, HG007692, and HL119145; by AHA grants D700382 and AHA957729; and by EU grant 101057619 to JL.

Abbreviations:

- CVD

Cardiovascular diseases

- ChIP-Seq

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- DCM

Dilated cardiomyopathy

- eQTL

Expression quantitative trait loci

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- THP-1

Human monocytic leukemia cell line

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- PAH

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- SNF

Similarity network fusion

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- snRNA-seq

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing

- WES

Whole exome sequencing

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- [1].Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, Barengo NC, Beaton AZ, Benjamin EJ, Benziger CP. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;76:2982–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Leopold JA, Maron BA, Loscalzo J. The application of big data to cardiovascular disease: paths to precision medicine. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2020;130:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Joshi A, Rienks M, Theofilatos K, Mayr M. Systems biology in cardiovascular disease: a multi-omics approach. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2021;18:313–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hasin Y, Seldin M, Lusis A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biology. 2017;18: 83. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1215-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cao ZJ, Gao G. Multi-omics single-cell data integration and regulatory inference with graph-linked embedding. Nature Biotechnology. 2022;40:1458–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cai Z, Poulos RC, Liu J, Zhong Q. Machine learning for multi-omics data integration in cancer. iScience. 2022;25:103798. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103798, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barabási A-L, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12:56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].LaHaye S, Corsmeier D, Basu M, Bowman JL, Fitzgerald-Butt S, Zender G, Bosse K, McBride KL, White P, Garg V. Utilization of whole exome sequencing to identify causative mutations in familial congenital heart disease. Circulation Cardiovascular Genetics. 2016;9:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ramchand J, Wallis M, Macciocca I, et al. Prospective evaluation of the utility of whole exome sequencing in dilated cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020;9:e013346. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhu N, Swietlik EM, Welch CL, et al. Rare variant analysis of 4241 pulmonary arterial hypertension cases from an international consortium implicates FBLN2, PDGFD, and rare de novo variants in PAH. Genome Medicine. 2021;13:80. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00891-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nikpay M, Goel A, Won H-H, Hall LM, Willenborg C, Kanoni S, Saleheen D, Kyriakou T, Nelson CP, Hopewell JC. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nature Genetics. 2015;47:1121–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Harst P, Verweij N. Identification of 64 Novel Genetic Loci Provides an Expanded View on the Genetic Architecture of Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation Research. 2018;122:433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Germain M, Eyries M, Montani D, Poirier O, Girerd B, Dorfmüller P, Coulet F, Nadaud S, Maugenre S, Guignabert C. Genome-wide association analysis identifies a susceptibility locus for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nature Genetics. 2013;45:518–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Aragam KG, Jiang T, Goel A, et al. Discovery and systematic characterization of risk variants and genes for coronary artery disease in over a million participants. Nature Genetics 2022;54:1803–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Auerbach BJ, Hu J, Reilly MP, Li M. Applications of single-cell genomics and computational strategies to study common disease and population-level variation. Genome Research. 2021;31:1728–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Funnell T, O’Flanagan CH, Williams MJ, et al. Single-cell genomic variation induced by mutational processes in cancer. Nature. 2022;612:106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sarno F, Benincasa G, List M, et al. Clinical epigenetics settings for cancer and cardiovascular diseases: real-life applications of network medicine at the bedside. Clinical Epigenetics. 2021;13:66. doi: 10.1186/s13148-021-01047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Westerman F, Sebastiani P, Jacques P, Liu S, DeMeo D, Ordovás JM. DNA methylation modules associate with incident cardiovascular disease and cumulative risk factor exposure. Clinical Epigenetics, 2019;11:142. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Smallwood SA, Lee HJ, Angermueller C, Krueger F, Saadeh H, Peat J, Andrews SR, Stegle O, Reik W, Kelsey G. Single-cell genome-wide bisulfite sequencing for assessing epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat Methods. 2014;11:817–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Örd T, Õunap K, Stolze LK, Aherrahrou R, Nurminen V, Toropainen A, Selvarajan I, Lönnberg T, Aavik E, Ylä-Herttuala S. Single-Cell Epigenomics and Functional Fine-Mapping of Atherosclerosis GWAS Loci. Circulation Research. 2021;129:240–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Selewa A, Luo K, Wasney M, Smith L, Tang C, Eckart H, Moskowitz I, Basu A, He X, Pott S. Single-cell genomics improves the discovery of risk variants and genes of cardiac traits. medRxiv. 10.1101/2022.02.02.22270312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liu C-F, Ni Y, Moravec CS, Morley M, Ashley EA, Cappola TP, Margulies KB, Tang WH. Whole-Transcriptome Profiling of Human Heart Tissues Reveals the Potential Novel Players and Regulatory Networks in Different Cardiomyopathy Subtypes of Heart Failure. Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine. 2021;14:e003142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.120.003142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li L, Chen Z, Scheidt M, et al. Transcriptome-wide association study of coronary artery disease identifies novel susceptibility genes. Basic Research in Cardiology. 2022;117:6. doi: 10.1007/s00395-022-00917-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rhodes CJ, Otero-Núñez P, Wharton J, Swietlik EM, Kariotis S, Harbaum L, Dunning MJ, Elinoff JM, Errington N, Thompson AAT. Whole-Blood RNA Profiles Associated with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Clinical Outcome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2020;15;202:586–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Takeuchi F, Liang Y-Q, Isono M, Ang MY, Mori K, Kato N. Transcriptomic Response in the Heart and Kidney to Different Types of Antihypertensive Drug Administration. Hypertension. 2022;79:413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Heidecker B, Kittleson MM, Kasper EK, Wittstein IS, Champion HC, Dussell S, Baughman KL, Hare JM. Transcriptomic Analysis Identifies the Effect of Beta-Blocking Agents on a Molecular Pathway of Contraction in the Heart and Predicts Response to Therapy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Basic Translational Science. 2016;1:107–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Paik DT, Cho S, Tian L, Chang HY, Wu JC. Single-cell RNA sequencing in cardiovascular development, disease and medicine. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2020;17:457–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Litviňuková M, Talavera-López C, Maatz H, et al. Cells of the adult human heart. Nature. 2020;588:466–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chaffin M, Papangeli I, Simonson B, , et al. Single-nucleus profiling of human dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nature. 2022;608:174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Reichart D, Lindberg DL, Maatz H, et al. Pathogenic variants damage cell composition and single cell transcription in cardiomyopathies. Science. 2022;377:eabo1984. doi: 10.1126/science.abo1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Koenig AL, Shchukina I, Amrute J, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals cell-type-specific diversification in human heart failure. Nature Cardiovascular Research. 2022;1: 263–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hill MC, Kadow ZA, Long H, et al. Integrated multi-omic characterization of congenital heart disease. Nature. 2022;608;181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Elorbany R, Popp JM, Rhodes K, Strober BJ, Barr K, Qi G, Gilad Y, Battle A. Single-cell sequencing reveals lineage-specific dynamic genetic regulation of gene expression during human cardiomyocyte differentiation. PLoS Genet 2022;18: e1009666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Paik DT, Cho S, Tian L, Chang HY, Wu JC. Single-cell RNA sequencing in cardiovascular development, disease and medicine. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2020;17:457–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kuppe C, Flores ROR, Li Z, et al. Spatial multi-omic map of human myocardial infarction. Nature 2022;608:766–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Karlsson M, Zhang C, Méar L, Zhong W, Digre A, Katona B, Sjöstedt E, Butler L, Odeberg J, Dusart P, et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Science Advances. 2021;7:eabh2169. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lindsey ML, Mayr M, Gomes AV, et al. Transformative Impact of Proteomics on Cardiovascular Health and Disease A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:852–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jiang L, Wang M, Lin S, Jian R, Li X, Chan J, Dong G, Fang H, Robinson AE. GTEx Consortium; Snyder MP. A Quantitative Proteome Map of the Human Body. Cell. 2020;183:269–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ho JE, Lyass A, Courchesne P, Chen G, Liu C, Yin X, Hwang S-J, Massaro JM, Larson MG, Levy D. Protein Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in the Community. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7:e008108. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wallentin L, Eriksson N, Olszowka M, et al. Plasma proteins associated with cardiovascular death in patients with chronic coronary heart disease: A retrospective study. PLoS Medicine 2021;18:e1003513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Henry A, Gordillo-Marañón M, Finan C, et al. Therapeutic Targets for Heart Failure Identified Using Proteomics and Mendelian Randomization. Circulation. 2022;145:1205–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Michelhaugh SA, Camacho A, Ibrahim NE, Gaggin H, D’Alessandro D, Coglianese E, Lewis GD, Januzzi JL Jr. Proteomic Signatures During Treatment in Different Stages of Heart Failure. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2020;13:e006794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Brunner AD, Thielert M, Vasilopoulou C, et al. Ultra‐high sensitivity mass spectrometry quantifies single‐cell proteome changes upon perturbation. Molecular Systems Biology. 2022;18: e10798. doi: 10.15252/msb.202110798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fernandez DM, Rahman AH, Fernandez NF, et al. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nature Medicine. 2019;25:1576–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mund A, Coscia F, Kriston A, et al. Deep Visual Proteomics defines single-cell identity and heterogeneity. Nature Biotechnology. 2022;40:1231–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Straubhaar J, D’Souza A, Niziolek Z, Budnik B. Single Cell Proteomics Analysis of Drug Response Shows its Potential as a Drug Discovery Platform. ChemRxiv. doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-js9wz-v2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].McGarrah RW, Crown SB, Zhang G-F, Shah SH, Newgard CB. Cardiovascular Metabolomics. Circulation Research. 2018;122:1238–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cavus E, Karakas M, Ojeda FM, et al. Association of Circulating Metabolites With Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in a European Population: Results From the Biomarkers for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe (BiomarCaRE) Consortium. JAMA Cardiology. 2019;4:1270–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wishart, David S. Emerging applications of metabolomics in drug discovery and precision medicine. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2016; 15:.473–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Talmor-Barkan Y, Bar N, Shaul AA, et al. Metabolomic and microbiome profiling reveals personalized risk factors for coronary artery disease. Nature Medicine. 2022;28::295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Guo S, Zhang C, Le A. The limitless applications of single-cell metabolomics. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2021;71:115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wei D, Xu M, Wang Z, Tong J. The Development of Single-Cell Metabolism and Its Role in Studying Cancer Emergent Properties. Frontiers in Oncology. 2022;11:814085. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.814085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Rhodes CJ, Sweatt AJ, Maron BA. Harnessing Big Data to Advance Treatment and Understanding of Pulmonary Hypertension. Circulation Research. 2022;130:1423–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Jay SM, et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 2013;153: 828–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Abdul-Salam VB, Wharton J, Cupitt J, Zerryman M, Edwards RJ, Wilkins MR. Proteomic analysis of lung tissues from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:2058–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sun X, Dalpiaz D, Wu D, Liu JS, Zhong W, Ma P. Statistical inference for time course RNA-Seq data using a negative binomial mixed-effect model. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016; 17:324. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1180-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Emerging Role of Precision Medicine in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation Research. 2018;122:1302–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Chen L, Wang RS, Zhang XS. Biomolecular Networks: Methods and Applications in Systems Biology. Wiley Series in Bioinformatics, 1st edition. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Jarcho JA, McKenna W, Pare JA, Solomon SD, Holcombe RF, Dickie S, Levi T, Donis-Keller H, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Mapping a gene for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to chromosome 14q1. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321:1372–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Newman JH, Wheeler L, Lane KB, Loyd E, Gaddipati R, Phillips JA, Loyd JE. Mutation in the gene for bone morphogenetic protein receptor II as a cause of primary pulmonary hypertension in a large kindred. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Dietz HC, Pyeritz RE, Hall BD, Cadle RG, Hamosh A, Schwartz J, Meyers DA, Francomano CA. The Marfan syndrome locus: confirmation of assignment to chromosome 15 and identification of tightly linked markers at 15q15-q21.3. Genomics. 1991;9:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hamid R, Cogan JD, Hedges LK, Austin E, Phillips JA, Newman JH, Loyd JE. Penetrance of pulmonary arterial hypertension is modulated by the expression of normal BMPR2 allele. Hum Mutation. 2009;30:649–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Repetti GG, Kim Y, Pereira AC, et al. Discordant clinical features of identical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. U.S.A. 2021;118:e2021717118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021717118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Stranger BE, Forrest MS, Clark AG, et al. Genome-wide associations of gene expression variation in humans. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Maron BA, Wang RS, Shevtsov S, et al. Individualized interactomes for network-based precision medicine in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with implications for other clinical pathophenotypes. Nature Communications. 2021;12:873. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21146-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Maron BJ, Maron MS, Christopher Semsarian. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 20 years: clinical perspectives. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:705–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Maron BA, Wang RS, Carnethon MR, Rowin EJ, Loscalzo L, Maron BJ, Maron MS. What Causes Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy? American Journal of Cardiology. 2022;179:74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Zhang P, Li S. Human cross-tissue cell atlases: unprecedented resources towards systematic understanding of physiology and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2022;7: 352. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01201-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Greene CS, Krishnan A, Wong AK, et al. Understanding multicellular function and disease with human tissue-specific networks. Nature Genetics. 2015;47:569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Arif M, Klevstig M, Benfeitas R, et al. Integrative transcriptomic analysis of tissue-specific metabolic crosstalk after myocardial infarction. Elife. 2021;10:e66921. doi: 10.7554/eLife.66921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Dai H, Li L, Zeng T, Chen L. Cell-specific network constructed by single-cell RNA sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47:e62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wang X, Choi D, Roeder K. Constructing local cell-specific networks from single-cell data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 2021;118:e2113178118. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21146-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hocker JD, Poirion OB, Zhu F, et al. Cardiac cell type-specific gene regulatory programs and disease risk association. Science Advances. 2021;7:eabf1444. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abf1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Gupta C, Xu J, Jin T, Khullar S, Liu X, Alatkar S, Cheng F, Wang D. Single-cell network biology characterizes cell type gene regulation for drug repurposing and phenotype prediction in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Computational Biology. 2022;18:e1010287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Cha J, Lee I. Single-cell network biology for resolving cellular heterogeneity in human diseases. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2020;52:1798–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wang B, Mezlini AM, Demir F, Fiume M, Tu Z, Brudno M, Haibe-Kains B, Goldenberg A. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nature Methods. 2014;11:333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wu Y, Wang H, Li Z, Cheng J, Fang R, Cao H, Cui Y. Subtypes identification on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction via network enhancement fusion using multi-omics data. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2021;19:1567–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Talukdar HA, Asl HF, Jain RK, et al. Cross-Tissue Regulatory Gene Networks in Coronary Artery Disease. Cell Systems. 2016;2:196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Zhou G, Pang Z, Lu Y, Ewald J, Xia J. OmicsNet 2.0: a web-based platform for multi-omics integration and network visual analytics. Nucleic Acids Research, 2022;50: W527–W533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Liu T, Salguero P, Petek M, Martinez-Mira C, Balzano-Nogueira L, Ramšak Z, McIntyre L, Gruden K, Tarazona S, Conesa A. PaintOmics 4: new tools for the integrative analysis of multi-omics datasets supported by multiple pathway databases. Nucleic Acids Research. 2020; 50:W551–W559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Ding J, Blencowe M, Nghiem T, Ha S, Chen YW, Li G, Yang X. Mergeomics 2.0: a web server for multi-omics data integration to elucidate disease networks and predict therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2021;49:W375–W387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Sadegh S, Skelton J, Anastasi E, et al. Network medicine for disease module identification and drug repurposing with the NeDRex platform. Nature Communications. 2021;.12:6848. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27138-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Wang RS, Croteau-Chonka DC, Silverman EK, Loscalzo J, Weiss ST, Hall KT. Pharmacogenomics and Placebo Response in a Randomized Clinical Trial in Asthma. Clinical and Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2019;106:1261–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Liu X, Maiorino E, Halu A, Glass K, Prasad RB, Loscalzo J, Gao J, Sharma A. Robustness and lethality in multilayer biological molecular networks. Nature Communications. 2020;11:6043. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]