Abstract

Background

In this study we evaluated the imaging capabilities of a novel Multi-pinhole collimator (MPH-Cardiac) specially designed for nuclear cardiology imaging on a Triple-NaI-detector based SPECT/CT system.

Methods

99mTc point source measurements covering the field of view (FOV) were used to determine tomographic sensitivity (TSpointsource) and spatial resolution. Organ-size tomographic sensitivity (TSorgan) was measured with a left ventricle (LV) phantom filled with typical myocardial activity of a patient scan. Reconstructed image uniformity was measured with a 140 mm diameter uniform cylinder phantom. Using the LV phantom once filled with 99mTc and after with 123I, Contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) was measured on the reconstructed images by ROI analysis on the myocardium activity and on the LV cavity. Furthermore, a polar map analysis was performed determining Spill-Over-Ratio in water (SORwater) and image noise. The results were compared with that of a dual-head parallel-hole low energy high resolution (LEHR) collimator system. A patient with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) was scanned on the LEHR system using local protocol of 16 min total acquisition time, followed by a 4-min MPH-Cardiac scan.

Results

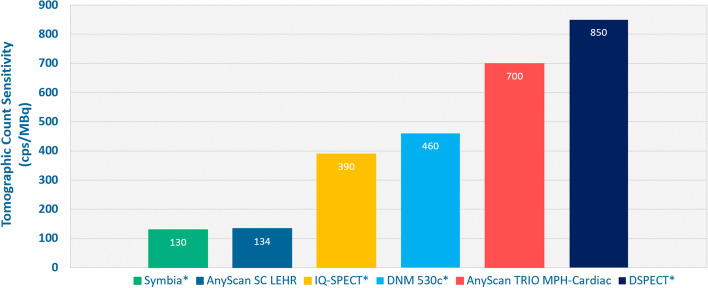

Peak TSpointsource was found to be 1013 cps/MBq in the axial center of the FOV while it was decreasing toward the radial edges. TSorgan in the CFOV was found to be 134 cps/MBq and 700 cps/MBq for the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac, respectively. Average spatial resolution throughout the FOV was 4.38 mm FWHM for the MPH-Cardiac collimator. Reconstructed image uniformity values were found to be 0.292% versus 0.214% for the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac measurements, respectively. CNR was found to be higher in case of MPH-Cardiac than for LEHR in case of 99mTc (15.5 vs. 11.7) as well as for 123I (13.5 vs. 8.3). SORwater values were found to be 28.83% and 21.1% for the 99mTc measurements, and 31.44% and 24.33% for the 123I measurements for LEHR and MPH-Cardiac, respectively. Pixel noise of the 99mTc polar maps resulted in values of 0.38% and 0.24% and of the 123I polar maps 0.62% and 0.21% for LEHR and MPH-Cardiac, respectively. Visually interpreting the patient scan images, MPH-Cardiac resulted in better image contrast compared to the LEHR technique with four times shorter scan duration.

Conclusions

The significant image quality improvement achieved with dedicated MPH-Cardiac collimator on triple head SPECT/CT system paves the way for short acquisition and low-dose cardiovascular SPECT applications.

Keywords: SPECT, SPECT/CT, Multi-pinhole, Nuclear cardiology, Image quality

Background

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) solutions for Myocardial Perfusion Imaging (MPI) were used for almost four decades as diagnostic tools for patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) [1, 2]. The visual interpretation of SPECT images along with image-derived quantitative measures (e.g., summed scores or total perfusion deficit (TPD)) [3, 4] provide high sensitivity diagnosis of the extent and severity of ischemia. Beyond perfusion, 123I-metaiodobensylguanidine (123I-mIBG) SPECT was also effectively introduced for the molecular level diagnosis of innervation disorders related to cardiomyopathies [5–8] as well as accurate prognosis [9] and clinical decision making [10] in case of patients with chronic heart failure (HF). While these clinically proven applications are widely used, the image quality of conventional NaI(Tl) dual-head SPECT with parallel-hole collimators remained limited due to the relatively low tomographic sensitivity and spatial resolution of this technique. During a conventional SPECT scan, only a few parts-per-million of the injected radiopharmaceutical is detected. Attempting to overcome this limitation several scanner design concepts were introduced, including heart-focused astigmatic collimators convergent on the image center [11–13] or organ-specific dedicated multi-pinhole (MPH) SPECT collimators [14–16] on Sodium Iodide (NaI(Tl)) crystal detectors, or the recently widely emerging solid-state Cadmium-Zinc-Telluride (CZT) detector-based heart-focused dedicated cardiac SPECT systems [17–19]. In addition, it is worth mentioning the Alcyone aperture approach, which is a combination of an MPH collimator focused on the heart with CZT technology in case of the MyoSPECT and the Discovery NM 530c systems [20–22]. All of the above-mentioned approaches can provide four to seven times higher tomographic sensitivity at the myocardium region compared to conventional SPECT imaging. The major clinical impact of myocardial SPECT sensitivity improvement is that it paves the way for shorter acquisition times and consequently lower probability of patient motion. Furthermore, it can also offer imaging protocols with reduced dose but uncompromised image quality. Moreover, these SPECT systems may provide a widely available opportunity to measure quantitative parameters from first-pass dynamic SPECT, such as absolute myocardial blood flow (aMBF) and myocardial flow reserve (MFR) which are proven prognostic markers improving risk stratification of CAD patients [23–25].

While the diagnostic and prognostic advantages of dedicated cardiac SPECT systems are already well reported [1, 2, 16–18, 23, 26], the clinical use of general-purpose SPECT systems equipped with cardiac specific collimators is still very relevant [2, 15, 16, 27]. In case of the heart-focused collimators the imaging performance [11, 13, 28, 29] along with the accurate clinical use [12, 30–34] has been already thoroughly investigated. Furthermore, the image quality performance of these systems was compared with CZT based and conventional SPECT using both phantom and patient scans [35]. MPH collimators specifically designed for SPECT imaging of the heart were also introduced [36, 37], featuring nine [38], twenty [39] or a combination of sixteen and twenty [40] pinholes for dual-detector SPECT as well as six pinhole collimators for a triple-detector system [41]. These approaches revealed better tomographic sensitivity and image quality performance compared to conventional low energy high resolution (LEHR) collimator NaI(Tl) SPECT. In this study we assessed the imaging performance of a new MPH collimator technology featuring thirty-six pinholes specifically designed for nuclear cardiology examinations on a triple-NaI-detector-based SPECT/CT system [42, 43]. We evaluated tomographic sensitivity, spatial resolution, reconstructed image uniformity, image quality phantom measurements and a proof-of-principle patient scan. Where applicable, we compared these results with that of a conventional LEHR collimator-based dual-head SPECT/CT system. In case of the image quality measurements, both 99mTc and 123I were used to evaluate the performance with these isotopes to ensure appropriate perfusion and innervation imaging applications.

Materials and methods

Triple-NaI-detector SPECT system with multi-pinhole collimator

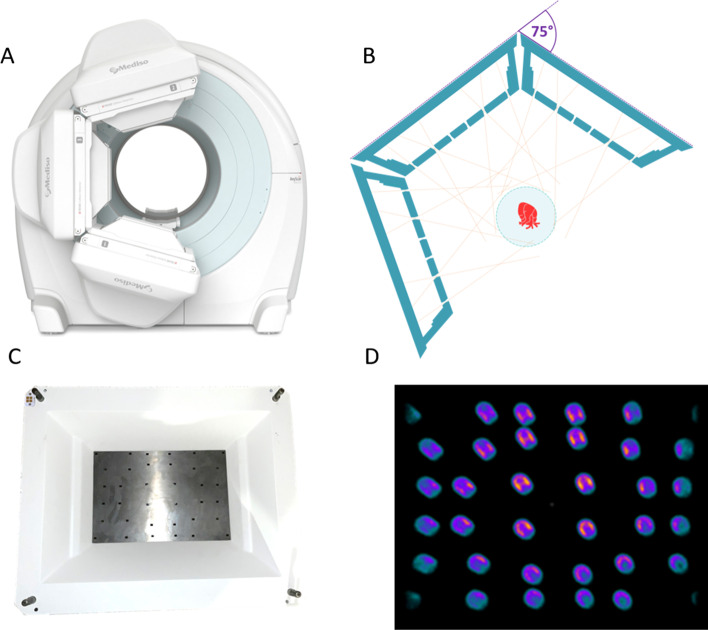

A general-purpose triple-NaI-detector SPECT/CT system, the AnyScan® TRIO (Mediso Medical Imaging Systems, Budapest, Hungary) was used in this study (Fig. 1. Panel A). Each SPECT detector head includes a 3/8″ NaI(Tl) scintillation crystal with 593 mm (transaxial) × 470 mm (axial) dimensions. Each detector head includes 94 photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) providing 2.9 mm UFOV intrinsic resolution of the detector, which is important for precise reconstruction since MPH is minifying projections on the detector surface. MPH-Cardiac collimator was designed for dedicated SPECT imaging with high count sensitivity at the location of the left ventricle (LV). The collimator features an 18 mm thick solid tungsten aperture plate including thirty-six pinholes (Fig. 1. Panel D). They are arranged to maximize count sensitivity and avoid multiplexing artifacts in the myocardium region [42, 44, 45] (Fig. 1. Panel C, D and E). The SPECT/CT system features a lateral-direction motion of the patient bed, allowing to position the myocardium in the rotational center of all three detector heads. Furthermore, the step-and-shoot detector movement is synchronized with table translation during the image acquisition process providing a helical scan trajectory. The MPH-Cardiac collimator system was designed to focus on the heart at maximum detector radius, avoiding collisions due to patient body proximity to the detector surface. In addition, a pressure sensitive touch foil is used for crash prevention on the surface of the MPH-Cardiac collimator and on the sides of the pyramids. Comparison measurements were taken with a general-purpose dual-head SPECT/CT system and LEHR collimators, the AnyScan® SC (Mediso Medical Imaging Systems, Budapest, Hungary) was used in this study. Each SPECT detector head is including 3/8″ NaI(Tl) scintillation crystal with 593 mm (transaxial) × 470 mm (axial) dimensions and 60 PMTs, providing 3.3 mm UFOV intrinsic resolution of the detector.

Fig. 1.

C-shape detector configuration of the triple-NaI-detector SPECT/CT system with MPH-Cardiac collimators (A); Schematic figure of projection trajectories of myocardium activity distribution for the MPH-Cardiac collimator system (B); A photograph of the rear view of the MPH-Cardiac collimator (C); Single projection image of the anthropomorphic phantom LV insert filled with 99mTc (D)

Image acquisition and reconstruction settings

Image acquisitions were performed with LEHR collimators on a dual-detector head SPECT system in 90° detector configuration, 64 views covering 180° scan arc, and the MPH-Cardiac collimators on a triple-NaI-detector SPECT system (AnyScan TRIO) in 75° detector configuration rotating 225° scan arc, 40 mm table movement helical scan with 24 gantry rotation steps. Helical scan means 40 mm in total table movement throughout the scan with 40/24 mm table movement in each step. Acquisition scan duration was 16 min in case of the LEHR and 4 min in case of the MPH-Cardiac measurements. These are net acquisition times excluding gantry rotation and table movement. Image reconstructions were performed with Tera-Tomo™ 3D SPECT-Q using the following settings: 8 iterations 4 subsets 3.3 mm voxel size in case of the LEHR measurements, 24 iterations 3 subsets 3.6 mm voxel size for the MPH-Cardiac measurements. In all cases we used vendor specific scatter correction and CT-based attenuation correction. The scatter of gamma rays in both the human tissue and the material of the collimator is modeled in the reconstruction software including changes in the energy of the photons. Only those counts are used for the image reconstruction, which fall into the predefined energy window in the acquisition protocol. In case of 123I, the reconstruction simulates more than one gamma photons simultaneously from the same isotope location, to more accurately model the actual emission, scattering, penetration in the edge of the pinholes as well as in the body of the patient. A more detailed description of the Tera-Tomo™ reconstruction method is described in a previous work [46]. A Gaussian post-filter was applied with 3 kernels and 4 sigma on both image sets. Any alteration from these acquisitions or reconstructions are indicated in the sections below.

Tomographic sensitivity

Two types of tomographic sensitivity measurements were performed: first using a point source prepared in a small Eppendorf tube to represent the point-by-point sensitivity profile (TSpointsource), and secondly a clinically more relevant organ-specific tomographic sensitivity (TSorgan) using a cardiac LV insert phantom. A 5 µl point source of 20.5 MBq 99mTc was prepared and measured throughout the central axis of the field of view (FOV) with 1 cm steps. This measurement series were repeated at 5 cm, and 10 cm transaxial offsets with 2 cm steps using the same point source. Radial sensitivity profile was measured with 2 cm steps using the same point source. Each measurement was taken with acquisition settings described above, but with no table movement and 120 s time duration. All measurements were decay corrected and tomographic sensitivity (TSpointsource.) was calculated based on the accumulated counts according to Eq. 1:

| 1 |

where Asst. refers to source activity at scan start, Tacq. refers to acquisition time duration. Tomographic organ sensitivity (TSorgan) was determined using the 99mTc filled DataSpectrum LV phantom measurements and image reconstructions described below. A large, 150 mm diameter VOI was applied on reconstructed SPECT images including the entire myocardium phantom to determine the accumulated counts. Using the total accumulated counts, the filled radioactivity and net acquisition time of these measurements, the TSorgan was calculated as proposed by Imbert et al.[35] as follows:

| 2 |

where Alv refers the activity in the left ventricle in MBq, Tacq refers to acquisition time duration in seconds.

Spatial resolution

Spatial resolution was determined in terms of Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) and Full Width at Tenth Maximum (FWTM) using the acquired image data for point source tomographic sensitivity. Point source images were reconstructed using Tera-Tomo™ 3D SPECT-Q with the settings and post filters described above, except for using 1.8 mm voxel size. ImageJ NMQC plugin [47] was used to calculate FWHM and FWTM on each reconstructed image set. Mean and Standard Deviation (St.Dev.) in axial, transaxial and radial directions were calculated for all axial and radial measurement series, as well as the absolute average spatial resolution of all point-source measurements.

Reconstructed image uniformity

A uniform cylinder phantom with 140 mm diameter [48], 105 mm length and 1200 ml total volume was filled with 16.32 ± 1.64 MBq 99mTc at the start of the acquisition. Two different imaging modes were used as described above along with the defined image reconstruction settings and post filters. A spherical volume of interest (VOI) with 50 mm diameter was applied on the reconstructed images to investigate reconstructed image noise. Mean and St.Dev. values were calculated on voxels within the applied VOIs.

Spill-over-ratio and noise analysis on polar maps

The commercially available LV insert phantom (Data Spectrum Corporation, Hillsborough, NC, USA) that mimics a perfusion deficit was used to carry out image quality comparison based on a myocardium shape activity distribution. The cold deficit chamber was filled with water. The LV walls for the first set of measurements were filled with a solution containing 10.00 ± 0.53 MBq 99mTc, and for the second set of measurements with 8.50 ± 0.26 MBq 123I. Image acquisitions of 16 min were performed for the LEHR, while in case of the MPH-Cardiac measurement a 4-min dataset was generated from the list-mode data of the 16 min measurements. The same single energy window was applied for LEHR and MPH-Cardiac when using the same isotope. In case of 123I the lower and upper limits of this window was set to ± 10% from the primary peak of 159 keV. For the 99mTc measurements, the applied energy window was ± 10% from the primary peak of 140 keV. Image reconstructions were performed with Tera-Tomo™ 3D SPECT-Q using the settings and post filters described above. Contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) was measured on the reconstructed images of all cases by applying a half-moon shaped ROIs on myocardium activity and circular ROIs on the LV cavity as indicated in Fig. 4 and calculating CNR as:

| 3 |

where MMyo refers to the mean of the myocardium ROI, MLVcav. is the mean of the LV cavity ROI, SDMyo refers to the standard deviation of the myocardium ROI, SDLVcav. is the standard deviation of the LV cavity ROI. Perfusion polar maps were generated using InterView™ XP software (Mediso Medical Imaging Systems, Budapest, Hungary) from all LV phantom measurements. A large asymmetric manual ROI was placed on the uniform area, while an elliptical manual ROI on the deficit area of all four polar maps. Spill-Over-Ratio in water (SORwater) was calculated as mean value of the deficit ROI voxel values divided by mean value of the uniform ROI voxel values and multiplied by 100. Noise was calculated as square of the St.Dev. of the uniform ROI voxel values divided by mean value of the uniform ROI voxel values and multiplied by 100.

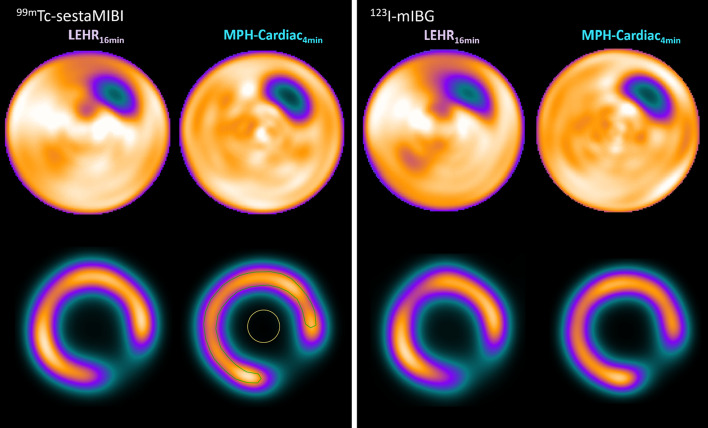

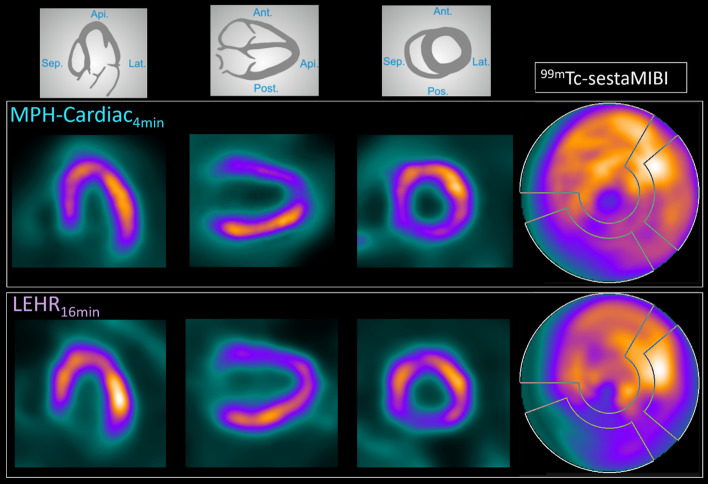

Fig. 4.

Polar Map representations of the Data Spectrum LV insert phantom filled with 99mTc (left upper row) and 123I (right upper row) measured with the AnyScan SC with LEHR 16 min acquisition and the AnyScan TRIO with MPH-Cardiac collimator 4 min acquisition. Short axis images of the reconstructed LV inserts are presented for the 99mTc (left lower row) and 123I (right lower row) measurements. Half-moon shaped ROI was applied on both the myocardium region of the phantom (green) and a circular ROI within the LV cavity (yellow). These ROIs were applied on all four LV SPECT images and CNR values were calculated based on Eq. 3

Patient scan

A 67 years old male patient (BMI = 35,5) with suspected CAD was injected with 342 MBq 99mTc-sestaMIBI. Pharmacological stress was performed using i.v. injection of 0.56 mg/kg dipyridamole. A 16 min acquisition was performed in supine position with a dual-head SPECT system using the local routine imaging protocol as described above, followed by a 4 min acquisition in supine position with the triple-NaI-detector SPECT using MPH-Cardiac with the imaging and reconstruction settings described above.

Results

Tomographic sensitivity

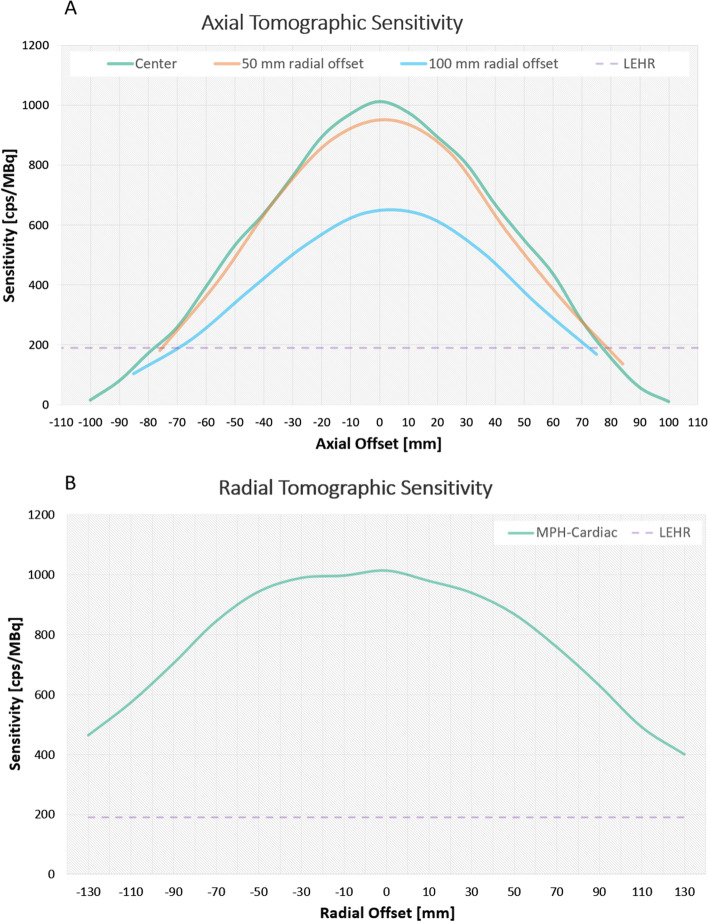

Peak tomographic sensitivity measured with the point source was found to be 1013 cps/MBq in the absolute axial center of the FOV (CFOV) while it is decreasing toward the radial edges: 951 cps/MBq at 5 cm radial offset from the CFOV and 641 cps/MBq at 10 cm radial from the CFOV. Meanwhile tomographic sensitivity decreases more drastically toward the axial edges of the FOV: 532 cps/MBq at 5 cm axial offset from the CFOV and 15 cps/MBq at 10 cm axial offset from the CFOV as can be depicted in Fig. 2. Panel A. TSorgan was found to be 134 cps/MBq versus 700 cps/MBq for the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac, respectively. Therefore, more than fivefold tomographic sensitivity gain can be achieved in the myocardium region with the MPH-Cardiac collimator and triple-NaI-detector SPECT.

Fig. 2.

Axial (A) and Radial (B) tomographic sensitivity profiles of the MPH-Cardiac collimator system. The axial sensitivity profile was measured at 50 mm and 100 mm radial offsets. The reference line of the LEHR tomographic sensitivity is displayed as a dashed purple line

Spatial resolution

The absolute average spatial resolution was found to be 4.38 mm FWHM calculated from the measurements with the MPH-Cardiac collimators along the central axis of the FOV and through the centrum of the FOV in the radial directions. The separate axial and radial Mean FWHM results are presented in Table 1. Along with the St.Dev. values.

Table 1.

Mean and Standard Deviation (St. Dev.) values of FWHM spatial resolution results calculated on the reconstructed images, measured along the central axis and through the centrum of the FOV in the radial directions

| Axial measurements FWHM [mm] | Radial measurements FWHM [mm] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X (axial) | Y (transaxial) | Z (radial) | X (axial) | Y (transaxial) | Z (radial) | |

| Mean | 4.91 | 4.85 | 3.36 | 4.85 | 4.21 | 4.10 |

| St.Dev | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.67 | 0.53 |

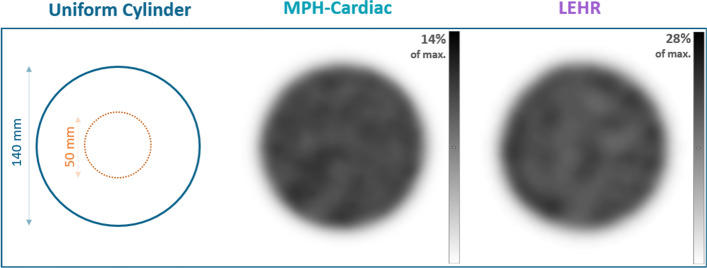

Image uniformity

Reconstructed SPECT images of the uniformity cylinder measurements can be seen in Fig. 3. The Mean and St.Dev values from the VOI analysis are presented in Table 2. The VOI analysis resulted 0.292% versus 0.214% uniformity values for the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac measurements, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Schematic figure and real images of the uniform cylinder (140 mm diameter) filled with 99mTc acquired on the AnyScan SC LEHR system and AnyScan TRIO with MPH-Cardiac collimator system. The upper limit of the inverted gray color bar compared to the maximum intensity in percentage is also indicated

Table 2.

The table displays the measured Mean and St.Dev. accumulated count values within the applied 50 mm diameter VOI, and the calculated image uniformity

| Collimator and Detector Configuration | 50 mm diameter VOI Mean [counts] | 50 mm diameter VOI St.Dev. [counts] | Image uniformity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LEHR 90° | 37.55 | 2.03 | 0.292 |

| MPH-CARDIAC 75° | 287.16 | 13.29 | 0.214 |

CNR, Spill-over-ratio and noise analysis

CNR was found to be 15.5 in case of MPH-Cardiac 11.7 for LEHR in case of 99mTc, while it was 13.5 and 8.3, respectively, when using 123I. Polar map analysis was performed on the LV phantom measurements with 99mTc and 123I. The MPH-Cardiac images showed much better contrast and image noise compared to the conventional LEHR technique as can be depicted in Fig. 4 and Table 3. Perfusion polar maps revealed SORwater values of 28.8% versus 21.1% for the 99mTc measurements with the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac configuration, respectively, as indicated in Table 3. In case of the 123I measurements, SORwater values were found to be 31.4% versus 24.3% for the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac measurements, respectively. Pixel noise of the 99mTc polar maps resulted values of 0.38% versus 0.24% for the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac, respectively. Meanwhile, 123I polar maps resulted values of 0.62% versus 0.21% for the LEHR and MPH-Cardiac, respectively. Visually interpreting the polar maps, in each case the MPH-Cardiac measurements resulted in better image contrast compared to the LEHR measurements for both isotopes despite of the shortened acquisition time as can be seen in Fig. 4.

Table 3.

SOR and Noise values calculated from ROI analysis of reconstructed SPECT image Polar Maps generated from DataSpectrum LV insert filled with 99mTc-sestaMIBI and 123I-mIBG measurements on the AnyScan TRIO MPH-Cardiac and AnyScan SC LEHR systems

| Collimator and Clinical Detector Configuration | 123I | 99mTc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNR | SORwater [%] | Noise [%] | CNR | SORwater [%] | Noise [%] | |

| LEHR 90° 16 min | 8.3 | 31.4 | 0.62 | 11.7 | 28.8 | 0.38 |

| MPH-CARDIAC 75° 4 min | 13.5 | 24.3 | 0.21 | 15.5 | 21.1 | 0.24 |

Patient scan

Reconstructed images and perfusion polar maps for the 16 min LEHR acquisition and 4 min MPH-Cardiac acquisition of the same patient are presented in Fig. 5. The reconstructed images revealed better contrast for MPH-Cardiac, as well as more homogenous polar map in the anterior wall region.

Fig. 5.

Representative post-stress SPECT image slices and polar maps of a 67 years old male CAD patient. Reconstructed images of the four minutes MPH-Cardiac acquisition (upper row) and sixteen minutes LEHR acquisition (lower row)

Discussion

There is a well-known trade-off between spatial resolution and tomographic sensitivity in case of MPI with conventional SPECT collimators. Several scanner configurations have been evaluated in the last decades to overcome these limitations, providing high tomographic sensitivity in the myocardial region with uncompromised spatial resolution. Imaging performance and clinical relevance of high sensitivity CZT SPECT systems has been thoroughly reported [17–19, 26, 35, 49, 50], including pitfalls and artifacts [51] related to the specific imaging scheme of the heart in case of these dedicated cardiac scanners. CZT detectors have improved energy response compared to conventional NaI(Tl) crystals which significantly reduces scatter fraction of the measured data. CZTs also incorporate superior intrinsic resolution, however the high sensitivity characteristics of solid-state SPECT systems are often mistakenly attributed to the CZT crystal [17]. Indeed, the density of CZT is higher compared to NaI(Tl), however due to cost considerations the detectors are thinner, and therefore, the intrinsic detector efficiency is comparable to the conventional detectors. The overall improvement in tomographic sensitivity at the myocardial region is gained by the innovative, heart-focused scanner and collimator designs. While many dedicated cardiac SPECT systems are available with excellent imaging performance [1, 16–22, 50], the NaI(Tl) crystal based, large field of view general-purpose SPECT scanners can also provide high sensitivity solutions for MPI [15, 16]. Imaging performance of heart-focused astigmatic collimators on dual-head systems were thoroughly reported [11, 13, 28–30, 33, 34]. Furthermore, MPH collimators on a dual-detector or triple-detector SPECT scanners were also studied [14, 38–41] revealing the clinical potential of this concept. Improved sensitivity in the myocardium region provides shorter acquisition with lower probability of patient motion, imaging protocols with reduced dose, and offers the possibility to measure aMBF and MFR from first-pass dynamic SPECT. The AnyScan TRIO is a large field of view, Triple-NaI-detector-based Whole-Body SPECT system that can be easily transformed into a dedicated cardiac scanner with a simple exchange of LEHR and MPH-Cardiac collimators. The AnyScan TRIO was already studied with the dedicated MPH-Brain collimator for imaging performance in case of 123I-ioflupane DAT-scan [46] and the clinical accuracy of this dedicated brain imaging technique was also reported [52]. This current study summarizes the imaging performance of the AnyScan TRIO SPECT/CT with the MPH-Cardiac collimator system specially designed for nuclear cardiology imaging applications. The MPH-Cardiac collimator uses a similar projection method as the MPH-Brain, however, both the collimator pyramids, pinhole numbers (36 vs. 20) and the pattern of projections differ between the two techniques. The central pinholes of the MPH-Cardiac collimator represent an overlap-free sampling of the LV, therefore there will be no overlapping artifact when the final image is reconstructed. On the other hand, peripheral pinholes are focused both on the LV and the surrounding tissues. The central region would be underutilized if a stand-alone myocardium was imaged. In reality, activity uptake outside of the central FOV is present (in the liver, intestine, etc.). Therefore, a distortion-free reconstruction requests that enough independent and unambiguous measurements of the myocardium and its surroundings should be provided. This condition is satisfied using projections of both the central and the peripheral pinholes. In all cases where image reconstruction was applicable, we used the same settings as for the patient scan, except in case of the spatial resolution results where lower reconstructed voxel size of 1.8 mm was applied. Measurements revealed increased TSpointsource of the triple-NaI-detector system with MPH-Cardiac up to 1013 cps/MBq compared to the conventional dual-detector LEHR sensitivity of 190 cps/MBq [46]. This increased sensitivity gain is attributed to both the MPH-Cardiac collimator design and the triple-NaI-detector in contrast to the parallel-hole and dual-detector conventional technique. In addition, this sensitivity gain is localized in the center of the FOV and decreasing toward the axial and radial edges, while for LEHR the sensitivity is relatively uniform throughout the entire FOV [46]. The limited useful FOV with high sensitivity gain demands cautious patient preparation to position the myocardium in the optimal FOV position, however, this phenomenon is also well reported for other heart-focused dedicated SPECT systems as well [11, 19, 51, 53]. The LV size tomographic sensitivity (i.e., TSorgan) for the AnyScan TRIO MPH-Cardiac configuration resulted 700 cps/MBq, more than five folds higher than that of the LEHR dual-detector imaging. These results were lower than the count sensitivity results reported for the CZT-based D-SPECT system, while 1.5 times higher than that of the CZT-based Discovery NM 530 and 1.8 time higher than that of the NaI(Tl)-based focused collimator dual-detector IQ-SPECT system as it was reported by Imbert et al. [35], and as it is presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

LV size tomographic count sensitivity (TSorgan) data measured on reconstructed images of the DataSpectrum LV phantom in case of AnyScan SC LEHR and AnyScan TRIO MPH-Cardiac, compared to several cardiac SPECT imaging systems of different vendors [35].*measured data from publication: Imbert et al. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2012, 53:1987–1903; https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.112.107417

Spatial resolution results are presented using the dedicated reconstruction method (Tera-Tomo™ 3D SPECT-Q) and not the gold standard Filtered Back Projection (FBP), since this method was not available for the MPH-Cardiac collimator system. However, this limitation is well reported for other dedicated SPECT systems as well [19, 48]. Both the visual assessment and the VOI analysis performed on the reconstructed images of uniform cylinder measurement confirmed that the triple-NaI-detector MPH-Cardiac technique provides better reconstructed image uniformity compared to the dual-detector LEHR technique. The applied activity for the DataSpectrum LV phantom 99mTc measurements was comparable to the mean value of a large VOI placed on the myocardium region of four randomly chosen real CAD patient reconstructed images with mean injected activity of 377 MBq, resulting a mean reconstructed value of 11.4 MBq within the applied VOI. CNR was found to be better in case of MPH-Cardiac than for LEHR in case of 99mTc (15.5 vs. 11.7) as well as for 123I (13.5 vs. 8.3). However, since many publications highlight the importance of summed difference scores (SDS) calculated on polar maps to diagnose reversible perfusion deficits, it is very important to evaluate the image quality not only on the reconstructed SPECT images but also on the polar maps. The LV phantom derived polar map analysis revealed that when using 99mTc the SORwater values were better in case of the MPH-Cardiac compared to LEHR 21.1 versus 28.8, respectively, while acquisition time was four times shorter (4 min). Polar map pixel uniformity was also superior for the MPH-Cardiac compared to LEHR: 0.24% and 0.38% regardless of the shortened acquisition time in case of MPH-Cardiac. Similarly, for the 123I isotope, SORwater was found to be superior for MPH-Cardiac (24.3) compared to LEHR (31.4). Polar map pixel uniformity was better for MPH-Cardiac (0.21%) when comparing to LEHR (0.62%). Since the polar map analysis of the current study revealed similarly good SORwater and pixel noise values for the 123I measurements as for the 99mTc measurement, the MPH-Cardiac collimator design could provide good image quality results for clinically relevant [5] 123I-mIBG cardiac innervation applications as well. The MPH-Cardiac features a solid tungsten aperture plate, which minimizes the potential of penetration of high energy photons in case of 123I, originating from the high energy peaks above the primary 159 keV [54]. A representative CAD patient scan revealed that excellent image quality can be achieved with the novel multi-pinhole technique of the MPH-Cardiac collimator even in case of four times shorter acquisition time compared to the conventional technique. These results anticipate fast and low-dose routine clinical applications in the future. It is important to emphasize that the imaging performance of the MPH-Cardiac system should be always evaluated while considering the equipment together with the dedicated image reconstruction algorithm Tera-Tomo™ 3D SPECT-Q. Beyond all these promising results, this study has some limitations. While the widely accepted NEMA NU-1 measurements became gold standard in performance comparison of SPECT systems, it is hardly applicable for organ-specific dedicated cardiac SPECT devices, and therefore it was not relevant in the current study. However, it is need to be emphasized that MPH-Cardiac is just one imaging mode of the AnyScan TRIO system (beyond LEHR Whole-Body and MPH-Brain modes) and the NEMA performance is indeed relevant when using LEHR collimators in Whole-Body mode. Therefore, only reasonable imaging performance measurements were carried out on this system, some of them proposed by former publications [35, 48]. All of these measurements could be extended to have a broader view of the imaging characteristics of this novel MPH concept. We only performed LV phantom measurements without any scattering media or background activity. A more comprehensive study should include evaluation with background as well, similarly as reported by Zoccarato et al. [55]. We only performed 123I measurements in case of the LV insert phantom due to the limited availability of this isotope at our institution. In case of 123I we only used LEHR collimator for the dual-detector system, however some publications suggest medium energy collimators for this isotope, which was not evaluated in this study. Measurements with medium energy collimator may have a significant impact on the SOR results of the LV phantom measurements with 123I. A more comprehensive study should include the rest of the phantom measurements and a patient scan with 123I-mIBG to ensure appropriate image quality for cardiac innervation application. The tungsten aperture together with the unique feature of SPECT for differentiation of isotopes based on their photopeak energy holds the potential for dual isotope imaging in the future. The patient scan was performed only in supine position, not considering the well reported benefits of combined prone plus supine imaging [4, 56–58]. Furthermore, patient image comparison with other dedicated systems could be biased due to the effects of patient positioning on the evaluation of myocardial perfusion SPECT [34, 49, 59]. Ecg-gated SPECT and consequently the functional parameters, i.e., LV Ejection Fraction (LVEF) was not assessed and validated in this study, a further investigation should compare volume measurement accuracy of gated SPECT with the MPH-Cardiac. We did not use respiratory gating or any other motion correction techniques. Addition of these methods may improve the image quality and precision of the MPH-Cardiac technique. We included a single representative CAD patient MPH-Cardiac image set together with the conventional dual-detector LEHR SPECT images; however, a comprehensive clinical validation should include large population of patient images to analyze further the clinical relevance of the AnyScan TRIO MPH-Cardiac system.

Conclusions

Significant image quality improvement can be achieved with a novel multi-pinhole technology, the MPH-Cardiac combined with triple-NaI-detector SPECT, when comparing to conventional parallel-hole LEHR collimator dual-detector SPECT. This improvement can be attributed to the increased tomographic sensitivity and uncompromised spatial resolution in the myocardium region, provided by the novel collimator design. Image quality improvement in MPH-Cardiac with triple-NaI-detector SPECT paves the way for shorter acquisition times and lower effective doses for both perfusion and innervation imaging applications in nuclear cardiology.

Abbreviations

- aMBF

Absolute myocardial blood flow

- BMI

Body mass index

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CFOV

Central field of view

- CNR

Contrast-to-noise ratio

- cps

Counts per second

- CT

Computer tomography

- CZT

Cadmium zinc telluride

- FOV

Field of view

- FWHM

Full width at half maximum

- FWTM

Full width at tenth maximum

- HF

Heart failure

- LEHR

Low energy high resolution

- LV

Left ventricle

- MBq

Mega becquerel

- MFR

Myocardial flow reserve

- MPH

Multi-pinhole

- MPI

Myocardial perfusion imaging

- NaI(Tl)

Thallium doped sodium iodide

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PMT

Photomultiplier tube

- ROI

Region of interest

- SORwater

Spill-over-ration for water

- SPECT

Single photon emission computed tomography

- St.Dev.

Standard deviation

- Tacq

Acquisition time

- TPD

Total perfusion deficit

- TSorgan

Organ-size tomographic sensitivity

- TSpointsource

Point source size tomographic sensitivity

- VOI

Volume of interest

Author contributions

AKK designed the study, the phantom measurements and wrote the manuscript draft. AKK, KK and WAM performed the phantom measurements. ZS, LB and JK helped at the phantom measurements. BS gave advice on optimal reconstruction and acquisition settings. SN reviewed the manuscript from the clinical aspect and advised on technical writing. TB designed the collimator and provided technical aspects on the system. SB analyzed the results from medical aspects. AF helped to design the study and gave supervision, helped in the planning of the measurements and to analyze the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Nothing to disclose.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The patient scan presented in this study was performed with the ethical approval of the Hungarian National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition. Ethical approval number: OGYEI/38000/2019. A written consent from the patient presented in this study was acquired well before the start of the procedure (i.e., radiopharmaceutical administration and SPECT acquisition).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Aron K. Krizsan, Kornel Kukuts, Walid Al-Muhanna, Zoltan Szoboszlai, Sandor Barna, Ildiko Garai were full-time employees of Scanomed Nuclear Medicine Center Debrecen, Hungary at the time of the measurements of this study. In further, co-authors of this publication, Attila Forgacs, Tamas Bukki, Balazs Szabo, Laszlo Balazs hold position at Mediso Medical Imaging Systems, Budapest, Hungary, the manufacturer of the multi-pinhole collimator evaluated in this study. There is no further conflict of interest for any of the other authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dewey M, Siebes M, Kachelrieß M, et al. Clinical quantitative cardiac imaging for the assessment of myocardial ischaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0341-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyafil F, Gimelli A, Slart RHJA, et al. EANM procedural guidelines for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy using cardiac-centered gamma cameras. Eur J Hybrid Imaging. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s41824-019-0058-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slomka PJ, Nishina H, Berman DS, et al. Automated quantification of myocardial perfusion SPECT using simplified normal limits. J Nucl Cardiol. 2005;12:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakazato R, Tamarappoo BK, Kang X, et al. Quantitative upright-supine high-speed SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging for detection of coronary artery disease: correlation with invasive coronary angiography. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1724–1731. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.078782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gimelli A, Liga R, Agostini D, et al. The role of myocardial innervation imaging in different clinical scenarios: an expert document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and Cardiovascular Committee of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeab007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gimelli A, Liga R, Avogliero F, Coceani M, Marzullo P. Relationships between left ventricular sympathetic innervation and diastolic dysfunction: the role of myocardial innervation/perfusion mismatch. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018;25:1101–1109. doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gimelli A, Liga R, Genovesi D, Giorgetti A, Kusch A, Marzullo P. Association between left ventricular regional sympathetic denervation and mechanical dyssynchrony in phase analysis: a cardiac CZT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:946–955. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimelli A, Liga R, Giorgetti A, Genovesi D, Marzullo P. Assessment of myocardial adrenergic innervation with a solid-state dedicated cardiac cadmium-zinc-telluride camera: first clinical experience. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:575–585. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pontico M, Brunotti G, Conte M, et al. The prognostic value of 123I-mIBG SPECT cardiac imaging in heart failure patients: a systematic review. J Nucl Cardiol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12350-020-02501-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakajima K, Nakata T. Cardiac 123I-mibg imaging for clinical decision making: 22-year experience in Japan. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:11S–19S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.142794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caobelli F, Ren Kaiser S, Thackeray JT, et al. The importance of a correct positioning of the heart using IQ-SPECT system with multifocal collimators in myocardial perfusion imaging: a phantom study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2015;22:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s12350-014-9994-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gremillet E, Agostini D. How to use cardiac IQ•SPECT routinely? An overview of tips and tricks from practical experience to the literature. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:707–710. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajaram R, Bhattacharya M, Ding X, et al. Tomographic performance characteristics of the IQ•SPECT system. IEEE Nucl Sci Symp Conf Rec. 2011:2451–2456.

- 14.Ozsahin I, Chen L, Könik A, King MA, Beekman FJ, Mok GSP. The clinical utilities of multi-pinhole single photon emission computed tomography. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020;10:2006–2029. doi: 10.21037/qims-19-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slomka PJ, Patton JA, Berman DS, Germano G. Advances in technical aspects of myocardial perfusion SPECT imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:255–276. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Liu C. Recent advances in cardiac SPECT instrumentation and imaging methods. Phys Med Biol. 2019 doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab04de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slomka PJ, Miller RJH, Hu LH, Germano G, Berman DS. Solid-state detector SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:1194–1204. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.220657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambhir SS, Berman DS, Ziffer J, et al. A novel high-sensitivity rapid-acquisition single-photon cardiac imaging camera. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:635–643. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlandsson K, Kacperski K, Van Gramberg D, Hutton BF. Performance evaluation of D-SPECT: a novel SPECT system for nuclear cardiology. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2635–2649. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/9/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bocher M, Blevis IM, Tsukerman L, Shrem Y, Kovalski G, Volokh L. A fast cardiac gamma camera with dynamic SPECT capabilities: Design, system validation and future potential. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1887–1902. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1488-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duvall WL, Croft LB, Godiwala T, Ginsberg E, George T, Henzlova MJ. Reduced isotope dose with rapid SPECT MPI imaging: Initial experience with a CZT SPECT camera. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:1009–1014. doi: 10.1007/s12350-010-9215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esteves FP, Raggi P, Folks RD, et al. Novel solid-state-detector dedicated cardiac camera for fast myocardial perfusion imaging: Multicenter comparison with standard dual detector cameras. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:927–934. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9137-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otaki Y, Betancur J, Sharir T, et al. 5-year prognostic value of quantitative versus visual MPI in subtle perfusion defects: results from refine SPECT. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:774–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2011;124:2215–2224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lairez O, Hyafil F, Bouisset F, Manrique A, Agostini D, Rouzet F. Assessment of coronary flow reserve in nuclear cardiology. Med Nucl. 2020;44:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein E, Miller RJH, Sharir T, et al. Automated quantitative analysis of CZT SPECT stratifies cardiovascular risk in the obese population: analysis of the REFINE SPECT registry. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12350-020-02334-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wetzl M, Sanders JC, Kuwert T, Ritt P. Effect of reduced photon count levels and choice of normal data on semi-automated image assessment in cardiac SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020;27:1469–1482. doi: 10.1007/s12350-018-1272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caobelli F, Kaiser SR, Thackeray JT, et al. IQ SPECT allows a significant reduction in administered dose and acquisition time for myocardial perfusion imaging: evidence from a phantom study. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:2064–2070. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.143560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shibutani T, Onoguchi M, Yoneyama H, Konishi T, Matsuo S, Nakajima K. Characteristics of iodine-123 IQ-SPECT/CT imaging compared with conventional SPECT/CT. Ann Nucl Med. 2019;33:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s12149-018-1310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibutani T, Nakajima K, Yoneyama H, et al. The utility of heart-to-mediastinum ratio using a planar image created from IQ-SPECT with Iodine-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Ronkainen AP, Eneh CTM, Linder PH, Hippeläinen E, Heikkinen JO. Assessment of ejection fraction and heart perfusion using myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography in Finland and Estonia: a multicenter phantom study. Nucl Med Commun. 2020;41:888–895. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000001234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okuda K, Nakajima K, Matsuo S, et al. Creation and characterization of normal myocardial perfusion imaging databases using the IQ·SPECT system. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018;25:1328–1337. doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0770-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leva L, Matheoud R, Sacchetti G, Carriero A, Brambilla M. Agreement between left ventricular ejection fraction assessed in patients with gated IQ-SPECT and conventional imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020;27:1714–1724. doi: 10.1007/s12350-018-1457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakajima K, Okuda K, Momose M, et al. IQ·SPECT technology and its clinical applications using multicenter normal databases. Ann Nucl Med. 2017;31:649–659. doi: 10.1007/s12149-017-1210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imbert L, Poussier S, Franken PR, et al. Compared performance of high-sensitivity cameras dedicated to myocardial perfusion SPECT: a comprehensive analysis of phantom and human images. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1897–1903. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.107417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan P, Chen L, Tsui BMW, Mok GSP. Evaluation of stationary and semi-stationary acquisitions from dual-head multi-pinhole collimator for myocardial perfusion SPECT. J Med Biol Eng. 2016;36:675–685. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Si C, Mok GSP, Chen L, Tsui BMW. Design and evaluation of an adaptive multipinhole collimator for high-performance clinical and preclinical imaging. Nucl Med Commun. 2016;37:313–321. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funk T, Kirch DL, Koss JE, Botvinick E, Hasegawa BH. A novel approach to multipinhole SPECT for myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowen JD, Huang Q, Ellin JR, et al. Design and performance evaluation of a 20-aperture multipinhole collimator for myocardial perfusion imaging applications. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:7209–7226. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/20/7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H, Wu J, Chen S, Wang S, Liu Y, Ma T. Development of stationary dedicated cardiac SPECT with multi-pinhole collimators on a clinical scanner. 2015 IEEE Nucl Sci Symp Med Imaging Conf NSS/MIC 2015. 2016;63.

- 41.Steele PP, Kirch DL, Koss JE. Comparison of simultaneous dual-isotope multipinhole SPECT with rotational SPECT in a group of patients with coronary artery disease. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1080–1089. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bagamery I, Bukki T, Wirth A. EP3309588B1. 2019.

- 43.Bagamery I, Bukki T, Wirth A. US11364001B2. 2022.

- 44.Lin J. On artifact-free projection overlaps in multi-pinhole tomographic imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2013;32:2215–2229. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2013.2277588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Audenhaege K, Vanhove C, Vandenberghe S, Van Holen R. The evaluation of data completeness and image quality in multiplexing multi-pinhole SPECT. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34:474–486. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2361051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tecklenburg K, Forgács A, Apostolova I, et al. Performance evaluation of a novel multi-pinhole collimator for dopamine transporter SPECT. Phys Med Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab9067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edam AN, Fornasier MR, De Denaro M, Sulieman A, Alkhorayef M, Bradley DA. Quality control in dual head gamma-cameras: comparison between methods and software used for image analysis. Appl Radiat Isot. 2018;141:288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi Y, Miyagawa M, Nishiyama Y, Ishimura H, Mochizuki T. Performance of a semiconductor SPECT system: comparison with a conventional anger-type SPECT instrument. Ann Nucl Med. 2013;27:11–16. doi: 10.1007/s12149-012-0653-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perrin M, Roch V, Claudin M, et al. Assessment of myocardial CZT SPECT recording in a forward-leaning bikerlike position. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:824–829. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.217695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Otaki Y, Manabe O, Miller RJH, et al. Quantification of myocardial blood flow by CZT-SPECT with motion correction and comparison with 15O-water PET. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s12350-019-01854-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allie R, Hutton BF, Prvulovich E, Bomanji J, Michopoulou S, Ben-Haim S. Pitfalls and artifacts using the D-SPECT dedicated cardiac camera. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathies F, Apostolova I, Dierck L, et al. Multiple-pinhole collimators improve intra- and between-rater agreement and the certainty of the visual interpretation in dopamine transporter SPECT. EJNMMI Res. 2022;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Hindorf C, Oddstig J, Hedeer F, Hansson MJ, Jögi J, Engblom H. Importance of correct patient positioning in myocardial perfusion SPECT when using a CZT camera. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s12350-014-9897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dobbeleir AA, Hambÿe ASE, Franken PR. Influence of high-energy photons on the spectrum of iodine-123 with low- and medium-energy collimators: consequences for imaging with 123I-labelled compounds in clinical practice. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:655–658. doi: 10.1007/s002590050434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zoccarato O, Lizio D, Savi A, et al. Comparative analysis of cadmium-zincum-telluride cameras dedicated to myocardial perfusion SPECT: a phantom study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23:885–893. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duvall WL, Slomka PJ, Gerlach JR, et al. High-efficiency SPECT MPI: comparison of automated quantification, visual interpretation, and coronary angiography. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20:763–773. doi: 10.1007/s12350-013-9735-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakazato R, Slomka PJ, Fish M, et al. Quantitative high-efficiency cadmium-zinc-telluride SPECT with dedicated parallel-hole collimation system in obese patients: results of a multi-center study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2015;22:266–275. doi: 10.1007/s12350-014-9984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Betancur J, Hu LH, Commandeur F, et al. Deep learning analysis of upright-supine high-efficiency SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging for prediction of obstructive coronary artery disease: A multicenter study. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:664–670. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.213538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kracskó B, Barna S, Sántha O, et al. Effect of patient positioning on the evaluation of myocardial perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018;25:1645–1654. doi: 10.1007/s12350-017-0865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.