Abstract

The supply of school mental health (SMH) providers and services cannot meet the demand of students in-need, and this gap is expected to widen in coming years. One way to increase the reach of helpful services for youth is to grow the SMH workforce through task-shifting to paraprofessionals. Task-shifting could be especially promising in expanding Motivational Interviewing (MI) interventions, as MI can be molded to target a number of academic and behavioral outcomes important to schools. However, no review of training exclusively paraprofessional samples in MI has yet been conducted. The current paper provides a scoping review of 19 studies of training paraprofessional providers to use MI to evaluate trainee characteristics, training content and format, and outcomes. Of these 19 studies, 15 reported that paraprofessionals improved in using MI following training. Nine studies reported that task-shifting MI was positively received by clients and/or providers. Six studies examined task-shifting MI in youth-serving contexts, and four examined the practice in traditional school contexts, suggesting its potential for use in SMH. Other findings and implications, such as client behavior change and provider fidelity, are shared, along with ideas for advancing research, practice, and policy in this subfield.

Keywords: Motivational Interviewing, School mental health, Task-shifting, Paraprofessionals

Over recent decades, schools in the USA have become increasingly responsible for identifying and treating the mental health needs of children and adolescents (hereafter referred to as youth; Eklund et al., 2020b; Weist et al., 2017). In fact, schools are the most common source of youth mental health care for both the general population and samples of youth with diagnoses or elevated symptoms (Duong et al., 2021). Ninety-six percent of public schools provide mental health services for students (Institute of Education Sciences, 2022). Ideally, school mental health (SMH) approaches are integrated into schools’ multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) and focus on improving students’ social, emotional, behavioral, and academic (SEBA) functioning on a continuum of care to match levels of student need with treatment intensity (Eklund et al., 2020b; Kilgus et al., 2021; Vaillancourt et al., 2016). The field of SMH has made many advances in promoting positive outcomes for youth, including increasing academic achievement and engagement, and decreasing mental health symptomatology (Strait et al., 2017). At the same time, however, there is increased incidence and prevalence of youth mental health concerns: One in six children has a diagnosed behavioral, developmental, or mental disorder, and one in six adolescents has made a suicide plan (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2021). School systems remain limited by resource and workforce shortages that restrict the effectiveness of their programming (García & Weiss, 2019; Graves et al., 2023; Guerra et al., 2019).

In the current context of cascading consequences from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the increasing visibility of equity challenges in schools (Liang et al., 2020; Weeks & Sullivan, 2019), it is likely that need for youth mental health services will continue to increase at a rapid rate (García & Weiss, 2020). It is also likely that the limited supply of school-based services will be exhausted by the most extreme student cases (Maggin et al., 2016; Zabek et al., 2022). In other words, existing SMH systems are being overrun, which overburdens professional providers and prohibits some youth from receiving treatment (Moon et al., 2017). This plight is illustrated by school-psychologist-to-student ratios exceeding the 500:1 recommendation from the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) in all but one state (Connecticut) during the 2021–2022 school year (NASP, 2021; Eklund et al., 2020a). In the same year, eight states had ratios exceeding 2,000:1 (NASP, 2021). Similar trends are noted in neighboring service areas, including school counseling and school social work. As such, there is urgent need to rethink and restructure the development, design, and delivery of SMH services (Power et al., 2020).

One strategy that has previously been posited and shown promise in addressing youth mental health problems is expanding the SMH workforce to include paraprofessional providers (Hart et al., 2021; McQuillin et al., 2015). This approach includes task-shifting, which the World Health Organization (WHO, 2008) defines as “a process whereby specific tasks are moved, where appropriate, to health workers with shorter training and fewer qualifications” (p. 7). These workers may be called lay providers, non-professionals, or paraprofessionals interchangeably (Saxe-Custack & Weatherspoon, 2013), though they are referred to paraprofessionals herein. In addition to growing specialized workforces and thereby increasing access to care (Hart et al., 2022b; Schneeberger & Mathai, 2015), task-shifting has been recognized for yielding a more efficient distribution of resources and services by measures of money and time, and for enhancing the role of community providers in service delivery without sacrificing the quality of care provided (WHO, 2008; Zachariah et al., 2009). Though originally developed and studied in medical contexts, task-shifting has spread to other fields, such as mental health and education. Indeed, task-shifting is nearly ubiquitous in schools, where it is common for teacher aides or assistants—individuals without a certification or license—to provide academic remediation or behavioral support to select students (Page & Ferrett, 2018); there is federal legislation that outlines provisions for paraprofessionals within schools (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2004). In under-resourced schools, there is an even higher prevalence of community members or paraprofessionals supplementing services (Simon & Ward, 2014).

Notably, there is emerging evidence that paraprofessional providers can help mitigate or prevent common challenges in schools, such as externalizing behaviors, using Motivational Interviewing (MI; McQuillin & McDaniel, 2021). Previous SMH work that task-shifted an academic motivation-building intervention for middle schoolers found no significant differences in student outcomes by provider type (Strait et al., 2020), and similar work shows that paraprofessionals effectively delivered the Student Check-Up (SCU; Strait, 2018), an MI-based, semi-structured intervention, to middle school students who subsequently reported increased academic attitudes, commitment, effort, and self-efficacy (Hart et al., 2022a; Strait et al., 2017). It is possible that paraprofessional-delivered supports could complement and expand services provided at all levels of MTSS (Hart et al., 2021): Paraprofessionals may (a) facilitate access to evidence-based interventions, (b) enable or enforce skills application and practice, and (c) deliver treatments (McQuillin et al., 2021). Collectively, this research demonstrates how task-shifting select SMH services can simultaneously benefit youth and relieve professional providers, such as school counselors and psychologists, of certain direct-service responsibilities, thereby addressing systems-level accessibility and resource issues.

MI may be particularly promising to couple with task-shifting in expanding and strengthening SMH initiatives, given its flexibility (i.e., MI is considered a transdiagnostic helping strategy) and its previous successes in working with students, parents, teachers, and problem-solving teams (Herman et al., 2021). Employing MI can complement other skills-based interventions and reduce a variety of motivational barriers common in schools (Frey et al., 2017), leading to positive associations with student SEBA outcomes (Frey et al., 2019; Rollnick et al., 2016; Terry et al., 2020). Further, MI is considered a key component of engagement and retention programs for child mental health (Ingoldsby, 2010). MI is most often used by highly trained, professional providers (e.g., physicians; Lundahl et al., 2013), but has also been effectively used by others with less training (Madson et al., 2013). MI uses an interpersonal approach to foster behavior change when individuals feel ambivalent. Ambivalence refers to having mixed feelings toward changing behavior (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Background and Mechanisms of Motivational Interviewing

MI can affect behavior for a variety of concerns and populations (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), including adolescent and pediatric samples (Borrelli et al., 2015; Cushing et al., 2014). Small to medium effect sizes have been found in health and medical settings (Lundahl et al., 2013) and education (Snape & Atkinson, 2016), leading to interest in integrating MI within SMH (Frey et al., 2011; Söderlund et al., 2011). MI emphasizes individuals’ autonomy in making behavior changes by encouraging people to generate their own plans and reasons for change, and then strengthening their resolve to enact these changes. The process model of MI includes four stages: First, engaging refers to creating a connection between the client and provider, and requires that the provider suppresses their fixing reflex, or their well-intentioned desire to solve a problem on the client’s behalf. The fixing reflex might appear as correcting, explaining, or providing directives or unsolicited advice (Easton, 2021). To better engage with and focus on clients’ desires, MI encourages the use of open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries—a practice often referred to using the acronym “OARS.” Notably, while the use of OARS is introduced in the engaging stage, it is often employed throughout the practice of MI. The second stage of MI is focusing, in which the client and provider jointly determine and maintain a direction in the dialogue regarding change. Third, MI involves evoking, or eliciting change talk, defined as the proportion of language focused on behavior change, from the client. Lastly, planning involves developing and working on a strategy to implement behavior change in the client’s life. Regarding the mechanisms of stages three and four, eliciting change talk draws attention to the importance of change, and planning for change involves building confidence.

In sessions of MI, exploring client ambivalence and promoting change talk are linked to better client outcomes in the form of positive behavior change (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009). Conversely, when providers exhibit MI-inconsistent behaviors, such as use the fixing reflex, clients tend to demonstrate worse outcomes. Therefore, providers who facilitate MI sessions play a meaningful role in shaping clients’ experiences and can harm or help those seeking services. These findings underscore the importance of delivering MI with fidelity and skill, and therefore, of effectively training the providers who use MI (Madson & Campbell, 2006).

Motivational Interviewing Training

Considerable research has sought to identify best practices in training professional providers to use MI (e.g., Barwick et al., 2012; Hall et al., 2016; Madson et al., 2009). Most MI trainings employ manuals, workshops, or a combination of the two (Schwalbe et al., 2014), though videos have also become popular, particularly in conjunction with the other two methods (de Roten et al., 2013). Training is often associated with favorable subjective evaluations from participants. For example, trainees report increased comfort in interacting with clients following instruction (Sargeant et al., 2008), as well as an increase in MI skills (Barwick et al., 2012; Madson et al., 2009; Söderlund et al., 2011). Feedback and contextual practice have also been recognized as important means of learning to use MI.

Miller and Moyers (2006) identify stages in learning MI, which include gaining familiarity with the underlying philosophy and tenets of MI (e.g., collaborating with clients and emphasizing autonomy), and eliciting, recognizing, and reinforcing change talk. Acquiring and practicing client-centered counseling skills including OARS is also crucial to learning MI. Training often focuses on earlier parts of the four-stage process model of engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning. For example, trainings more often attend to building motivation and resolving ambivalence than to planning for change (Söderlund et al., 2011), and OARS was the one component of training present in every study included in Madson and colleagues’ (2009) systematic review of MI trainings. In teaching providers MI, it may be equally important to impart (a) how to use MI skills, and (b) how to suppress other approaches that are incompatible with MI, such as the fixing reflex (Hall et al., 2016; Söderlund et al., 2011).

Other studies have examined more specific aspects of MI training, such as the added value of demonstrations and feedback (Barwick et al., 2012; de Roten et al., 2013), and whether trainer expertise affects outcomes (Hall et al., 2016). Though this information is valuable in designing future programs, these large-scale studies of MI trainings limit inclusion criteria to professional providers (Hall et al., 2016; Söderlund et al., 2011), and therefore their future relevance may be restricted to training professionals. Especially in SMH, restricting the delivery of MI-based programs to professionals substantially limits the reach of programming that could benefit a wide range of youth.

Motivational Interviewing and Paraprofessional Providers

Despite relatively little inquiry into task-shifting MI to paraprofessional providers, previous findings suggest that this coupling is a promising approach to increasing the reach of mental health services. For instance, professionals are more likely than lay people to feel established and expert in their approach to working with clients and therefore may struggle to implement the heavily collaborative nature of MI (Ball et al., 2002a; Söderlund et al., 2011). Other work suggests the prior-to-training education level of trainees (i.e., whether trainees have a master’s degree) is negatively correlated with training effect sizes (Schwalbe et al., 2014), perhaps demonstrating that paraprofessionals make greater MI gains. Similarly, the length of time that professionals specialize in working with a certain population had no effect on MI training outcomes (de Roten et al., 2013). These findings indicate that clinical experience does not necessarily translate to a provider’s ability to learn MI, and paraprofessionals may be able to acquire MI skills and strategies as easily or better than those with prior specialized training.

Moreover, Schwalbe and colleagues (2014) identified that the following features enhance traditional MI workshops: First, chunking training into smaller segments and tailoring these units to specific contexts; second, using booster sessions in providing MI trainings; and third, employing computer-, video-, or web-based technologies to administer trainings. Each of these aspects aligns with just-in-time trainings (JITTs), which have been recognized for their fit with task-shifting, particularly in expanding psychosocial services to youth (Hart et al., 2022b; McQuillin et al., 2019). Just-in-time training is described as “only the training necessary, when it is necessary, to produce competent service provision” (p. 3–4). Notably, competent service provision refers to a basic or satisfactory level; it differs from mastery or proficiency. JITTs are noted for their portability, such as in the format of brief, on-demand videos. In providing a proof-of-concept supporting the combination of JITTs and task-shifting, McQuillin and colleagues (2019) discuss the expansion of SMH services to students who typically do not qualify for assistance from professional providers, echoing the value of this approach in the current context.

Goals of this Review

In sum, there is some empirical support (e.g., Simon & Ward, 2014; Snape & Atkinson, 2016; Strait et al., 2020) and ample theoretical support for task-shifting MI in SMH (Frey et al., 2011; Herman et al., 2021; McQuillin et al., 2019). Moreover, there are established lines of research devoted to harnessing the mechanisms of change in MI interventions (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009; Frey et al., 2021) and to identifying best practices in training professionals to use MI (e.g., Barwick et al., 2012; Söderlund et al., 2011). Unfortunately, however, work combining these efforts is underdeveloped. Based on extensive literature review, it appears there is no existing work that exclusively reviews MI training features that affect the transfer of skills to paraprofessionals, let alone with attention to SMH. The present paper aims to fill these two gaps in the literature and to offer a novel, actionable contribution to SMH.

To this end, this scoping review paper (Munn et al., 2018) uses similar approaches and criteria as previous reviews of training professionals to use MI. Specifically, the goal of this review is to examine the content, duration, format, measures, and outcomes of training paraprofessionals to use MI. Scoping reviews identify and map the existing literature on a given topic (Armstrong et al., 2011); they aim to characterize concepts or recognize knowledge gaps through a methodical synthesis of existing literature (Choi et al., 2022). Notably, scoping reviews are not synonymous with meta-analyses, though they can be helpful precursors to these systematic reviews (Munn et al., 2018). Scoping reviews are recommended when there is emerging or unclear evidence regarding which specific questions can be best answered through a more precise systematic review. Herein, authors evaluate the pertinent studies on their features of training and the transfer of skills to paraprofessionals, as well as on their relevance to SMH. We summarize the current body of literature and discuss future directions. In conclusion, we once more contextualize these findings and discuss the benefits they could imbue for youth when thoughtfully applied to SMH programs.

Methods

Literature Search

With the assistance of a masters-level University research librarian, the first author, a doctoral candidate in School Psychology, conducted a systematic search of studies evaluating the effectiveness and/or process of training paraprofessional providers to use MI. Using EBSCOhost PsycINFO, PubMed, and ScienceDirect databases, the first author searched the following keywords: Motivational Interviewing or Motivational Enhancement Therapy; training, teaching, or education; and lay provider, paraprofessional, student, or task-shifting. The first author also reviewed the references of relevant articles (e.g., Maslowski et al., 2021) and used the Google Scholar “Cited by” tool to identify other articles.

Reflecting the exclusion/inclusion criteria and other methodological aspects of review papers examining MI training among professionals, the current search was limited to studies available in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Further exclusion criteria included: (a) studies lacked reporting of training details and/or outcomes; (b) provider/trainee credentials were not sufficiently specified to classify them as a paraprofessional; (c) providers were not traditional clinicians but were still credentialed in a profession; (d) providers were not professionals, but were not paraprofessionals; or (e) providers were not adults. Examples of articles excluded due to criteria (c), (d), and (e) included studies that studied task-shifting MI to high school counselors, doctoral students in psychology, and individuals under 18 years of age, respectively. Existing review articles were also excluded from the present project. Titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine fit and relevance per inclusion of information about training in MI, as well as details regarding features of training. Due to the relative recency of this field, no limits were placed on the publication date of studies.

Study Eligibility and Selection

Given the high education level of those most often trained in MI, this work operationalizes paraprofessional providers as adults with a bachelor’s degree or less—including a degree in progress—as well as those to whom the original literature explicitly identified as paraprofessionals, such as community health workers (Cooperman et al., 2007; do Valle Nascimento et al., 2017). In some cases, samples included a small portion of individuals with education beyond a bachelor’s degree (e.g., Weir et al., 2009 in which one trainee had a master’s degree); however, authors specified that this person’s educational background was not related to counseling so they could still be considered a paraprofessional trainee in MI. For a study to be included in the present review, trainees needed to be entirely or primarily paraprofessionals. Papers also needed to include at least one feature of training (e.g., content, duration) and one finding or outcome related to training (e.g., acceptability, skill improvement). These aspects of inclusion criteria were kept intentionally broad due to the limited existing work on training paraprofessionals in MI.

Results

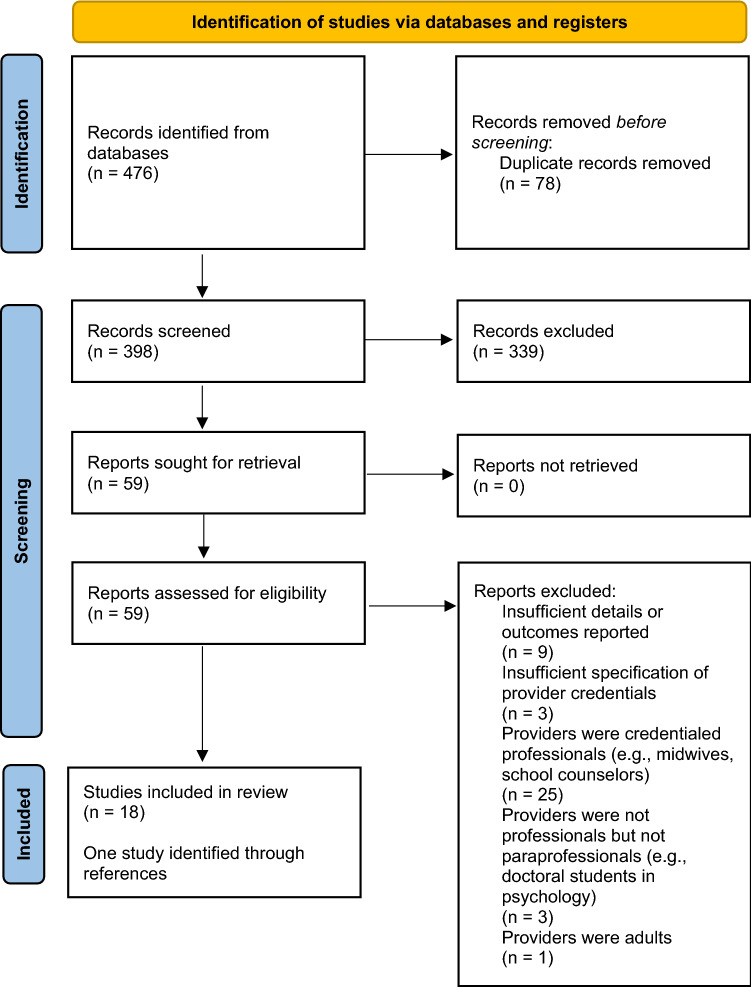

The PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1 depicts the number of records at each phase of the review. Of the 476 studies that were identified through initial searching, 398 abstracts were screened after removing duplicate articles. At this stage, 339 articles were excluded and full texts of the remaining 59 articles were reviewed. Forty-one of these articles were excluded due to meeting one or more of the five aforementioned exclusion criteria, leaving 18 studies remaining. One study identified through reference lists was added. In total, 19 studies of training paraprofessionals to use MI were included in the current review. Findings are summarized below, and Table 1 describes each study in more detail. Further, studies that were most relevant to school mental health are discussed in more detail at the end of this section.

Fig. 1.

The flow of information and records at the different phases of this scoping review

Table 1.

Studies of training paraprofessionals to use Motivational Interviewing (MI)

| Study | Program/study aim and context | Trainee details | Training features | Evaluation/measurement | Notes and results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperman et al., (2007) | Evaluate brief MI intervention to improve medication adherence among HIV-positive, opioid-dependent patients at methadone clinics in New York City | Paraprofessional adherence counselors with minimal prior experience with MI and cognitive-behavioral skills training | Initial two-day MI workshop conducted by experienced trainer who developed intervention (no details on training components); ongoing, weekly training and supervision in group and individual formats in which providers and supervisors review session tapes and debrief | No formal measures of provider MI fidelity/gains outside of supervisor report; medical data and structured questionnaires (e.g., adherence) provide patient health data | Program evaluation ongoing, but suggests that paraprofessional adherence counselors can be trained to provide semi-structured MI-based counseling; paraprofessional-delivered MI is well-positioned to complement existing programs; well-received by clinic staff in variety of roles, high patient interest |

| do Valle Nascimento et al., (2017) | Improve type 2 diabetes outcomes and self-management of adults in low-income São Paulo, Brazil via monthly home visits | Nineteen (19) salaried paraprofessional community health agents (CHAs) recruited locally; women aged 25–60; all had at least some secondary education | Forty hours of training in work duties prior to behavioral counseling training. Prior to intervention: 32 h of workshop training (no further details of format) focused on autonomy-supportive MI communication skills and devising action plans. Four hours of booster training per month over six-month intervention period | Researchers observed random sample of visits using adapted “One Pass Coding System” MI fidelity checklist; patients completed self-report surveys regarding health behaviors, quality of care | All but three CHAs obtained basic competency in MI (more listening and questioning than advice-giving); program well received by CHAs and patients; patient improvements in activity, diet, medication adherence |

| Gisore et al., (2014) | Improve newborn care practices and increase health facility (versus home) births among pregnant women in Kenya via health survey home visits | Four (4) paraprofessional community health workers (CHWs): community developer, human resource worker, retired nurse, and secretary. Two were fluent in the local dialect | Four-day residential MI training from a behavioral scientist (no content or format information included) | No measurement of MI information reported; patient health records used | Patients showed increased health facility delivery, knowledge of birth and newborn health, use of mosquito nets, indicating value of the MI-based intervention program relative to education/information alone |

| Grant et al., (1999) | Study home visit (~ 2/month) program over three years for alcohol- and drug-abusing mothers in greater Seattle, WA | Twelve (12) paraprofessional advocates in recovery from alcohol and/or drug abuse (≥ 6 years); most are mothers in their early 30s; diverse ethnic/racial composition; all have high school diplomas; background employment in social services | Formal training prior to program (~ 80 h) focused on background/process, included required readings on MI and program; shadowing more experienced advocates (~ 40 h); ongoing training (1 + hr/wk individual supervision, ~ 2 h/wk group supervision with clinician); joint workshops with other organizations (e.g., CPS, Planned Parenthood); accompanying manual and visit protocols | No formal measures of provider MI fidelity/gains outside of supervisor report; full-time program evaluator focused on client behavior change and program development | To maximize advocate retention and satisfaction: salary and benefits, manageable caseload, community recognition, creative problem-solving, staff retreats, annual evaluations, etc. Mothers’ outcomes (alcohol/drug use, care engagement, child well-being) exceeded those of standard community care controls |

| Madson et al., (2013) | Evaluate teaching undergraduates MI through formal coursework; controlled setting | Eighty-three (83) undergraduates in the southeastern USA (mean age = 23.7); majority female (~ 80%) and white non-Hispanic (~ 60%); 17% had prior counseling theories class; 16% had prior counseling-related job |

Three tracks: (1) 1-week intensive MI course, 8 h/day; (2) 16-week extended MI course, 2 mtgs for a total of 2.5 h/wk; (3) 1-h MI lecture (overview of major components) embedded into counseling theories course. Courses included opportunities for practice (with feedback), demonstrations, and theory via lectures, readings, videos |

Pre- and post-measures in order: Motivational Interviewing Knowledge Assessment Test (MIKAT); Motivational Interviewing Self-Skill Assessment (MISSA); Video Assessment of Simulated Encounters- Revised (VASE-R) | Undergraduates gained more knowledge and skills through the courses than through the one-hour lecture; undergraduate coursework can be an effective avenue for teaching MI |

| Naar-King et al., (2009) | Compare paraprofessional and masters-level providers in improving primary care engagement/retention among youth with HIV in Detroit | Four (4) African-American peer outreach workers (POW) ages 20–25; graduated from high school in local community | Both types of interventionists received two full days of MI training (no information regarding content or format) followed by program protocol reviews and role plays for several weeks; skills maintained by weekly MI coaching from trainer; providers could review their session tapes | Fidelity determined by reviewing and coding random segments of audiotaped sessions using the MITI | POW had equal or higher MI fidelity as clinicians; youth in both groups improved in appointment regularity but higher effect size among youth in POW group |

| Newman-Casey et al., (2020) | Improve medication adherence among patients with glaucoma | Eight (8) glaucoma paraprofessional staff (medical assistants and technicians), most had some college education; mean age = 32 years, 88% female | Three group MI training sessions (didactic) totaling 16 h, focused on OARS, problem-solving, identifying/reinforcing change-talk, and planning through presentations and role play; two hours of individualized coaching | Patient encounters coded on MITI by two MINT trainers; participants completed Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior (KAB) scale and satisfaction surveys, provided additional feedback via interviews; patient surveys | Improvements in global and relational (empathy, partnership) MI scores, reflections; staff-rated program highly (helpful and important); staff fell short of MI proficiency; patients reported higher autonomy in their care |

| Saxe-Custack & Weatherspoon, (2013) | Support and prompt positive behavior change among people with Type 2 diabetes in Michigan | ~ 200 community-based, trained paraprofessionals supported by professional staff | Paraprofessionals and supervisors participated in three-day workshop including nutrition and MI (techniques, practice activities); additional trainings twice a year; accompanying manual and support materials (ex: handouts) | No formal measures of provider behavior; patient health data gathered/studied, including attitude and behaviors | Paraprofessionals can effectively extend the reach of adjunctive care; patients received program well and demonstrated health-related changes |

| Simon & Ward, 2014 | Evaluate MI training program for paraprofessionals in high school academic advising roles | Seventeen (17) part-time paraprofessional academic advisors (75% female; 53% Black, 41% white, ranging 22–50 years old) with varying background experiences but minimal familiarity with MI | 16 h of initial training (background, core skills) via lecture, videos, and applied practice; two, two-hour booster sessions; five, two-hour group supervision sessions (reviewing videos) | MIKAT, VASE-R, and excerpts from the MITI code used to measure provider MI behavior/skills; motivation to use MI measured through Change Questionnaire Version 1.2 | Participants demonstrated higher MI knowledge, increased competency in application, and continued motivation to learn MI (no data on transfer to student outcomes) |

| Simper et al., (2017) | Evaluate an MI training for undergraduate nutrition majors | Thirty-two (32) final-year nutrition students (84% female, mean age = 20 years) in the UK, untrained in counseling | Five three-hour group sessions of initial training (background, demonstrations, role plays); one session of individual video feedback; supplemental materials available (handouts, videos) | Students’ behaviors coded using MITI 3.1 | Students exhibited more MI consistent behaviors (OARS) one month following training; training was well-received |

| Snape & Atkinson, (2015) | Study intervention designed to reduce disaffection among high school students in the UK over five weekly sessions | Five (5) paraprofessional school staff in various roles, three women two men | 90-min MI training session including background; session overviews to guide delivery | No formal measures of MI gains/skills (rely on supervisor report); providers took part in focus groups; pupils’ school motivation measured via survey | Findings indicate few/minimal effects on students’ school motivation; providers rated program highly (noted benefits of MI) and indicated interest in continued use; identified some barriers/limitations |

| Strait et al., (2017) | Evaluate (replication attempt) the Student Check-Up (SCU), an academic intervention for middle school students | Eleven (11) undergraduate psychology students, majority female | After four training sessions (including didactics and demonstrations of early-stage processes, format and length of trainings unspecified), paraprofessionals took a written test of MI and participated in role-play fidelity tests which included feedback and supervision (needed to pass to participate); SCU protocol review | Paraprofessionals needed to pass role play and written test (custom, unnamed) to evaluate MI fidelity/skills; student data obtained through school records and surveys | No difference between student treatment and control groups in grades, participation; intervention may have changed students’ beliefs (e.g., importance of participation); paraprofessional participants scored > 90% on self-report fidelity checklists |

| Strait et al., (2020) | Compare para- and professional delivery of a group, instrumental school-based mentoring program for sixth graders in SE/Hispanic Texas | Ten (10) undergraduates referred by psychology professors compared to second-year school psychology graduate students | Prior to program: All providers read program manual, watched five online training videos (~ 36 min. total) including overview of MI (OARS). Then, a 2.5-h in-person training (OARS and session plans) and a pre-program site visit including brief roleplay | MI measured via providers’ self-reported fidelity; supervisors conducted momentary time sampling and submitted Supervisor Confidence Scale; providers and students indicated acceptability; grades reflect academic effects | No significant differences in fidelity and students’ engagement by provider type; similar findings for academic improvements and treatment acceptability. Undergrad paraprofessionals demonstrated more non-instructional behavior (i.e., working alongside mentees) |

| Tollison et al., (2008) | Examine effects of peer-provided, structured MI intervention on college student drinking behavior | Three (3) undergraduate and three (3) graduate students served as peer facilitators | Training workshops (format and length unspecified) review program manual, MI basics, example videos, and allow practice exercises; weekly group follow-up trainings (including discussions, role plays) | MITI (Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity) coding system and Motivational Interviewing Skills Code 2.0 on recorded sessions | Peer facilitators reached mixed basic MI competency (ex: empathy, not complex reflections); more open ended questions associated with more participant contemplation (increasing readiness to change) |

| Tsai et al., (2017) | Evaluate MI-based training program for peer specialists working with multi-need veterans in Connecticut | Fourteen (14) peer specialists hired by VA at least three years prior to start of study; most were Black or White males in their 40s with at least some college education; all had histories of psychiatric issues; some had histories of homelessness | Two-day MI workshop including background/processes, skill demonstrations, practice; two, 1.5-h monthly booster sessions in group format (content review and supervision/troubleshooting) | MI fidelity assessed using Independent Tape Rater Scale (Ball et al., 2002b) | Specialists decreased in MI inconsistence (e.g., gave less unsolicited advice) and sharing personal experiences following trainings; no changes in overall MI competence |

| Wahab et al., (2014) | Address depression among African-American women victims of intimate partner violence | Peer IPV advocate from local community (African-American IPV survivor) with no prior clinical or MI training | Two-day initial MI workshop with booster training two weeks later (18 h total, content referenced but unspecified); individual bi-monthly training and supervision (debriefing, role plays, video review) | MITI 3.0 (Moyers et al., 2007) used to code audio recorded sessions | Increased MI skills particularly related to ongoing supervision sessions, though inconsistent competency; intervention was positively received by participants |

| Walters et al., (2010) | Compare MI-based probation supervision to waitlist control and to supervision-as-usual in Texas | Ten (10) probation officers carrying non-specialized caseload who volunteered for MI training | Two-day MI workshop (lecture, demonstrations, practice; content unspecified) followed by half-day booster session; one or two monthly supervision meetings for the following six months | Officer Responses Questionnaire used to measure reflective listening; Dual-Role Relationship Inventory used to assess relationship quality; role plays coded using MITI used to measure MI attitudes and skill | Training program improved officers’ skills; no significant changes in probationers’ outcomes over four months |

| Weir et al., (2009) | Reduce risk behaviors associated with HIV and/or intimate partner violence among women involved in the justice system in Oregon | Four (4) non-professional community health specialists; three with a bachelor’s degree, one with a master’s, none trained as counselors but had experience working with marginalized women | Interviews included role play to measure natural reflective listening; 65 h of initial MI training; monthly consultations/supervisions including performance reviews and group trainings throughout three-month-long intervention | Randomly selected audiotaped sessions coded using Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (Miller, 2000) | Health specialists delivered interventions with fidelity; service recipients in intervention group had reduced rates of unprotected sex, similar findings regarding drug risk behavior; minimal effects of intervention on violence-related measures |

| Yahne et al., (2014) | Increase educational attainment (HS graduation rate) among teen mothers in New Mexico | Six (6) paraprofessional peer mentors (teen moms) age 18–22 years who had graduated from high school | Interviews included role play to gauge natural communication style; training occurred over four half-day sessions in the same week, focused on MI background, research, demonstrations, guided practice, discussions; ongoing coaching/feedback for each session over duration of program | Randomly selected excerpts of audio recorded sessions coded using the MITI | Program well received by providers and participants; peer mentors obtained MI competency but experienced some struggles (e.g., using open versus closed questions) |

Aim, Context, Design, and Relevance to School Mental Health

Of the 19 studies reviewed, six sought to provide services to youth, and four of these projects occurred in K-12 school settings. The other studies engaged youth participants through a primary/community health clinic and a university office, respectively. One additional study aimed to induce positive behavior change among college students, thereby straying from a traditional (K-12) SMH context but still sharing similarities regarding aim and population. Eleven of the remaining studies reviewed occurred in medical and/or social service contexts and targeted majority adult populations: Three studies sought to support individuals with HIV; two studies each sought to support individuals with Type 2 diabetes, women who had been victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), and mothers at risk for negative child and/or maternal health outcomes; and one study each sought to support older adults with glaucoma, multi-need veterans, and individuals on probation. As such, some studies specified that target patients had complex or overlapping needs (e.g., women with HIV who had been victims of IPV). The remaining two studies measured the effects of training paraprofessionals in controlled versus applied settings, such as in the context of undergraduate coursework, and therefore did not target a specific population to receive services. The geographic reach of studies of task-shifting MI-based service delivery to paraprofessionals spanned multiple cities in the USA (n = 15), the UK (n = 2), Kenya, and Brazil.

Fifteen of the studies identified are best described as preliminary investigations of the development and feasibility of MI task-shifting programs. Three of the studies employed quasi-experimental designs. For example, one compared paraprofessionals’ service delivery to that of providers with more extensive and specialized training, and another compared multiple formats or methods for training. One study randomized provider participants into treatment, waitlist control, or “as usual” conditions and therefore can be considered a true experiment (Walters et al., 2010).

Characteristics of Paraprofessional Trainees

Studies included in the present review demonstrate substantial variability regarding characteristics of the paraprofessionals trained to provide MI. For example, trainee cohort size ranged from four individuals in multiple studies to approximately 200 people in one study. Although two studies did not specify the trainee cohort size and were therefore excluded from this brief analysis, the median number of paraprofessionals included was 12 across applied and controlled settings, and 10 when only applied settings were included.

The ages and education levels of trainees also ranged widely across studies. The youngest adult paraprofessionals trained in MI were 18 years old, while the oldest specified trainee age range went up to 60 years. Some studies also failed to report the education level of trainees, but when stated, most trainees had completed some college or were currently enrolled as undergraduates (n = 7), had obtained a high school diploma (n = 3) or bachelor’s degree (n = 2), or had completed some secondary education (n = 1).

Regarding cultural, ethnic, and/or racial diversity of paraprofessional trainees, only six studies included one or more specifying features of their participants. In three of these six studies, trainees were primarily Black or white non-Hispanic. In one study, participants were primarily Black or white Hispanic, and in two studies, participants were entirely African-American. In one of the former studies and the latter three studies, authors stated that paraprofessional providers were selected in part due to their backgrounds or identities being congruent with the communities they aimed to serve. Eight studies of the 17 that occurred in applied settings reported the demographics of MI service recipients. In two of these studies samples were predominantly white, but in the remaining studies, samples consisted entirely or predominantly of historically minoritized groups, including African-American and Hispanic individuals. In two studies, authors indicated that they obtained ethnic/racial demographic data for service recipients but did not report the data in their manuscripts.

When the genders of trainees were reported, it appeared more common that the cohorts were majority-women; however, several studies again noted the importance of congruent identities between paraprofessional providers and the populations they serve, which in the context of these studies may best explain the trend. For example, paraprofessionals working with mothers with substance abuse disorders were women (Grant et al., 1999) and paraprofessionals working with multi-need military veterans were majority men (Tsai et al., 2017). Five studies specifically noted the importance of recruiting paraprofessionals from the local community, and another five studies mentioned “peer” mentoring or outreach.

In addition to some studies’ attention to trainees’ personal backgrounds, a small subset of studies considered trainees’ professional backgrounds. For example, Grant and colleagues (1999) recruited paraprofessionals who had previously been employed by social services agencies, due to commonalities between social service work and their task-shifting efforts. Similarly, some studies included information about the process of recruiting and selecting paraprofessional trainees. One study that enlisted undergraduates to deliver a middle school-based mentoring program employed a referral process with professors in the university’s psychology department (Strait et al., 2020), while another required paraprofessionals to reach at least 90% competence/fidelity in a role play and written test before delivering services (Strait et al., 2017). Two other studies used a formal hiring process for paraprofessionals and included role plays in their interviews to gauge the natural communication style of potential trainees and to evaluate their natural congruence with MI.

Training Characteristics, Content, and Support

Each of the studies reviewed featured at least one initial workshop-style training led by an expert to teach paraprofessionals about MI. Only one study did not include information about the duration of the workshop; others ranged in length from 90 min to 80 h over multiple days. The modal workshop length spanned approximately two days, with seven of the 19 studies reviewed reporting this approach. When specified, workshop content/format included background information, general and specific MI skills and strategies like OARS, MI session demonstrations, and opportunities to practice with or without feedback. However, specific details regarding the material conveyed to paraprofessionals was lacking from studies overall. When applicable, some studies included program-specific training in these workshops as well.

Thirteen of the studies included some form of follow-up training, such as booster sessions, coaching, and supervision once paraprofessionals began delivering MI services. Ongoing supervision and training occurred in both group and individual formats, and allowed paraprofessionals to ask questions regarding their use of MI. Other subsequent trainings introduced paraprofessionals to progressively complex MI skills or reinforced skills conveyed in original trainings. Seven of the studies explicitly mentioned additional material supports for trainees, such as a manual or protocol to guide program delivery, supplemental readings, or links to demonstration videos. Table 2 depicts which training components were included in each study.

Table 2.

Components of training in efforts to task-shift MI to paraprofessionals

| Study | Refer or screen | Initial training | Booster or follow-up | Supervision | Manual or protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperman et al., (2007) | Two days | X | X | ||

| do Valle Nascimento et al., (2017) | 32 h | 4 h/month | |||

| Gisore et al., (2014) | Four days | ||||

| Grant et al., 1999 | 80-h + 40-h shadowing | X | X | X | |

| Madson et al., (2013) | Three tracks: 8 h/day for one week; 2.5 h/wk for 16 weeks; 1-h lecture | ||||

| Naar-King et al., (2009) | Two days | X | X | X | |

| Newman-Casey et al., (2020) | 16-h group; 2-h individualized | ||||

| Saxe-Custack & Weatherspoon, (2013) | Three days | Twice per year | X | ||

| Simon & Ward, (2014) | 16 h | 2, 2-h sessions | X | ||

| Simper et al., (2017) | Five three-hour sessions | X | |||

| Snape and Atkinson, (2015) | 90 min | X | |||

| Strait et al., (2017) | X | Four sessions (length unspecified) | X | ||

| Strait et al., (2020) | X | 2.5-h training + videos | X | ||

| Tollison et al., (2008) | Format and length unspecified | X | X | ||

| Tsai et al., (2017) | Two days | X | X | ||

| Wahab et al., (2014) | Two days | X | X | ||

| Walters et al., (2010) | Two days | X | X | ||

| Weir et al., (2009) | X | 65 h | X | ||

| Yahne et al., (2014) | X | Four half-days | X |

A mark of “X” denotes that a training feature was present, but no further details were provided in the original study

Measures of Motivational Interviewing

Fourteen of the 19 studies reported using formal MI measures in their evaluations of training paraprofessionals. Among the measures used, versions of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) code (Moyers et al., 2007) were most common; eight studies employed the MITI. In these studies, recordings of paraprofessionals delivering MI were reviewed by trained coders with attention to overall MI spirit as well as to counts of specific MI-consistent behaviors. Two studies each used the Motivational Interviewing Knowledge Assessment Test (MIKAT; Leffingwell, 2006) and the Video Assessment of Simulated Encounters- Revised (VASE-R; Rosengren et al., 2008) to measure paraprofessionals’ MI behavior and knowledge. Other formal measures, cited in one study each, include the Independent Tape Rater Scale (Ball et al., 2002b), the Motivational Interviewing Self-Skill Assessment (MISSA; Dyehouse, n.d.), and the One Pass Coding System for MI (McMaster & Reniscow, 2015). Three studies employed custom measures of MI, such as by building MI items into their program fidelity checklists. Some studies used multiple measures of their trainees’ behavior. The five remaining studies did not report information regarding a formal or validated measure of MI in their evaluation; however, three of these studies employed subjective evaluations or reports, such as from professionals who served as trainers or supervisors.

Study Findings; Outcomes

The most consistent conclusion among the studies reviewed was that paraprofessionals can be trained to deliver MI-based interventions, with 15 of the studies explicitly reporting increases in MI-consistent behaviors among trainees. Most paraprofessionals improved in MI competence and were able to deliver MI-based interventions with fidelity. The next most widespread finding, evident in nine of the studies reviewed, was a positive subjective response to task-shifting MI to paraprofessionals. For example, clients and/or providers indicated that the task-shifted program was a helpful and pleasant experience, and some studies noted systems-level improvements in program culture due to a more efficient allocation of work. Paraprofessional providers and their colleagues indicated a continued interest in participating in these programs. In seven of the studies reviewed, training paraprofessionals led to positive behavior change among clients; however, four of the studies reported mixed or null findings regarding translating paraprofessional training to client outcomes.

Studies Relevant to School Mental Health

As previously stated, four studies of task-shifting MI to paraprofessionals occurred in K-12 school settings and targeted youth as service recipients. Simon and Ward (2014) trained 17 (75% female; 53% Black, 41% white; ranging 22–50 years old) part-time, paraprofessional academic advisors to use MI to promote academic achievement and intrinsic motivation among low-income, minority, and urban youth. Following 16 h of initial training, two two-hour follow-up training sessions, and supervision, paraprofessionals demonstrated higher MI knowledge, increased competency in application, and continued motivation to learn MI per formal, validated measures. No data regarding this program’s effects on student outcomes were reported.

Snape and Atkinson (2015) trained five paraprofessional school staff (three women, two men) to use MI in hopes of reducing disaffection among high school students. Paraprofessionals participated in a 90-min training session and received materials to guide their weekly meetings with students over a five-week period. In post-program focus groups, paraprofessionals noted the benefits of MI and their interest in continued participation, while also identifying some barriers to the program. Students’ school motivation, measured via survey, was insignificantly affected.

Strait and colleagues (2017) trained 11 undergraduate students to deliver the Student Check-Up (SCU), an academic intervention for middle school students. These paraprofessionals completed four introductory training sessions (format and length unspecified) and a program-specific written test; then, role plays for which they received professional feedback prior to working with students. Students’ grades were insignificantly affected, but students increased in their endorsements of the importance of academic effort and in-class participation following the program.

Strait and colleagues (2020) compared paraprofessionals’ (10 undergraduates referred by psychology professors) and professionals’ (second-year psychology graduate students) delivery of a group, instrumental, school-based mentoring program for sixth graders. Prior to program delivery, all providers reviewed the program manual, viewed five online training videos, and completed a two-and-a-half hour in-person training that included a role play. Study findings showed no significant differences in program fidelity and students’ engagement by provider type. Academic improvements and treatment acceptability were also rated similarly. According to momentary time sampling conducted by supervisors, paraprofessionals demonstrated less instructional behavior in their meetings with students than did professionals, thus showing more consistency with MI.

Discussion

This scoping review examines previous studies of training paraprofessionals to use MI, thereby expanding the existing knowledge base of MI training in a novel way. Further, this review was conducted with attention to each study’s relevance to SMH, trainee characteristics, training content and measures, and outcomes. Findings largely support that, when trained in MI, paraprofessionals can complement and expand medical, mental health, and social service workforces, and can instill or prompt positive behavior changes among varied populations with whom they work. Though most studies reviewed in the present paper were preliminary investigations, their findings indicate that expanding and strengthening health- and social-service workforces by task-shifting MI holds potential.

These findings can be applied to SMH initiatives in efforts to close the current and projected wide gap between available professionals who traditionally provide SMH services and students who could benefit from or need additional, specialized supports. For example, paraprofessional school-based providers could deliver lower-intensity mental health interventions to students at mild or moderate risk for deleterious outcomes, while professionals’ attention and expertise would be directed to more severe cases. Similarly, more highly trained professionals could shift to systems-level consultation and intervention work. Hart and colleagues (2021) propose a detailed model for incorporating paraprofessional mentors into traditional school contexts, which could inform efforts to actualize task-shifting MI in SMH. These recommendations should be coupled with existing best practices for school-related trainings to allow for applications that are contextualized and effective.

The findings of this review suggest the promise of future efforts to task-shift MI: The range of study aims, contexts, and patient and provider populations, demonstrates the practice of task-shifting MI can be tailored or transferred to address unique needs. Given that SMH programs often encompass a wide range of initiatives and targets (Kilgus et al., 2021), these approaches may be particularly well-aligned. Further, the large proportion of studies that occurred in applied, direct-service contexts suggests that task-shifting MI to paraprofessionals offers an actionable way to reduce the need-to-access gap in SMH. In other words, this approach holds practical—as well as theoretical—promise and displays ample research-to-practice evidence.

In the current review, the formats and methods used to train paraprofessionals in MI were varied across studies. For example, there was a large range in trainee cohort sizes, as well as in the personal backgrounds of trainees. This variability may further suggest that employing paraprofessionals to deliver MI is a flexible approach that can be adapted to specific contexts and needs. However, as stated in several of the included studies, it appears valuable to engage paraprofessionals who share important characteristics or features to those receiving their services. In other words, it may be important that clients and facilitators/providers come from the same community or share similar life experience. In some cases, this type of congruence allows providers to better relate to, and therefore to better serve, their clients (Heinonen & Orlinsky, 2013). One way this may manifest is in allowing respective organizations to determine the specific roles and titles of paraprofessional providers, such as to reduce the stigma commonly associated with mental health services (Zhao et al., 2015).

Another key takeaway of the current review is the finding that some programs employed targeted recruitment and/or selection processes for paraprofessional providers. Among professionals and students-in-training, providers’ personal differences and traits have been linked to MI fidelity and subsequent client outcomes (Hall et al., 2016; Maslowski et al., 2021). As such, appealing to paraprofessionals with certain personal or professional qualities (e.g., a background in human services) may yield more effective programming. Similarly, screening potential providers by conducting role plays as part of the interview process, as done by Yahne et al., (2014), can help detect a natural aptitude or predisposition that is more congruent with MI. This practice might reduce training burdens and, in turn, could increase the effectiveness of task-shifting MI on a larger scale.

Among the included studies, trainings varied widely in duration and frequency; however, the most consistent training technique was at least one initial workshop-style exercise, suggesting that a basic introduction or orientation to MI is necessary for paraprofessionals to learn relevant skills and strategies. This design format echoes trainings of professionals, where workshop-style trainings are often considered more effective than other approaches in isolation (Schwalbe et al., 2014). Also echoing findings of studies with professionals, the current review found that training paraprofessionals to use MI often emphasizes more basic or earlier stages of the approach versus planning for change. Future work with paraprofessionals should further examine and quantify whether trends evident among training professionals are present among paraprofessionals. For example, combining training approaches (e.g., employing experiential exercises, providing coaching or feedback, or distributing accompanying guides or handouts in addition to or as part of didactic workshops) may strengthen training gains, as might ongoing practice and supervision (Hall et al., 2016; Madson et al., 2009).

However, these methods incur intensive training and supervision burdens for those in administrative or supervisory roles who are responsible for managing paraprofessional providers. Given that a primary goal of task-shifting is to relieve professional providers of certain duties to yield a more efficient service model (WHO, 2008), future work must explore ways to lessen these burdens. In other words, decreasing a professional’s direct service responsibilities, but simultaneously increasing their supervision and training duties, does little to offset the already-inequitable distribution and unavailability of professional services. As such, future work may seek to identify aspects of training that could be effectively automated (e.g., through computer or video systems, etc.) to be easily distributed and reproduced in scaling efforts (Schwalbe et al., 2014). Similarly, research might examine the utility of JITTs in providing booster sessions.

The measures used in examinations of task-shifting MI may also benefit from future refining and streamlining. In the current review, findings demonstrate inconsistency and, in some cases, a lack of rigor (e.g., relying only on subjective reports), across the measures of MI used. Though the largest proportion of studies used the MITI (Moyers et al., 2007) coding system, considered the “gold standard” in measuring MI, the MITI remains accompanied by several drawbacks, including that it is cumbersome and lengthy to complete (Moyers et al., 2016). This shortcoming is significant as MI providers speculate that the cost and time of completing fidelity assessments can cause low treatment fidelity (Browne et al., 2022). In general, the lack of standardization and usability among measures used to evaluate MI task-shifting indicate that future work is needed to make this an acceptable and effective approach. As examinations of task-shifting MI progress beyond preliminary work, clearly identifying intervention targets and corresponding measurement approaches will be crucial to advancing the field’s knowledge base. Though variability is common across research in MI—generally speaking—efforts to increase the reliability and validity of findings could also lay the groundwork for a future meta-analysis of training paraprofessionals to use MI (Munn et al., 2018).

Future work should also combine these preliminary findings of training paraprofessionals with existing findings and frameworks of task-shifting. For example, McQuillin and colleagues (2019) emphasize the needs to consider ethical responsibilities to clients and professions, identify specific tasks to shift, and recognize constraints of any proposed task-shifting model. To maximize the potential impact of task-shifting MI on SMH, piloting efforts must draw from the literature in several fields. Implementation science, for example, suggests that successfully executing an MI curriculum through task-shifting would first rely on obtaining buy-in and support from key stakeholders (Barwick et al., 2012; Simon & Ward, 2014).

Limitations

The primary limitation of the current review is the difficulty of drawing conclusions about optimal trainee or training features, due to the lack of controlled trials of task-shifting MI and to the substantial variability across studies reviewed. Trainings widely ranged in content and duration, and most of them lacked detailed, quantified, or standardized information regarding the content conveyed and the training methods used. As such, it would be difficult and problematic to compare these studies to one another in a way that identifies moderating effects of training components (e.g., in the context of a meta-analysis). Further, the inconsistent reporting and unstandardized measures across studies limit the generalizability of any specific findings to future trainings. The number of studies that strayed from a focus on SMH may also be considered a limitation of the present review.

Moreover, there was a widespread lack of information regarding the diversity of included samples and therefore of applicability to diverse populations. Future work should ensure that task-shifting MI in SMH efforts is intentional in considering cultural, racial, and other domains of diversity among providers and youth. Although the current findings hold implications for students and adults who serve them (e.g., guidance in creating wider availability of SMH services, and a reformed workforce and redistributed tasks) ensuring that practices are beneficial to and inclusive of all populations is paramount to the future development and broad impact of this emerging subfield (Clauss-Ehlers et al., 2013).

Conclusions

Expanding the SMH workforce to include paraprofessionals in prevention and treatment efforts may help to offset the drastic and growing need-to-service gap noted among youth in the USA. Specifically, having paraprofessionals deliver MI-based services is hopeful given MI’s flexible but widespread fit with SMH and past use by paraprofessional providers. This shift would require substantial planning and restructuring in determining how to best adjust responsibilities and roles for professional providers, in addition to rigorous ongoing evaluation. However, this approach may be worthwhile given the current need for SMH services and shortage of SMH providers. The present review indicates that equipping paraprofessionals with MI skills is promising in expanding the reach of services. It also reveals many possible follow-up questions for future research in SMH to explore. Specifically, there is a need for more controlled studies in this area to inform future task-shifting efforts.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mackenzie J. Hart, MJHART@email.sc.edu

Samuel D. McQuillin, Email: MCQUILLS@mailbox.sc.edu

Aidyn Iachini, Email: IACHINI@mailbox.sc.edu.

Mark D. Weist, Email: WEIST@mailbox.sc.edu

Kimberly J. Hills, Email: HILLSKJ@mailbox.sc.edu

Daniel K. Cooper, Email: dc47@mailbox.sc.edu

References

- Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction (abingdon, England) 2009;104(5):705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane Update. 'Scoping the scope' of a Cochrane review. Journal of public health (Oxford, England) 2011;33(1):147–150. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S. A., Martino, S., Corvino, J., Morganstern, J., & Carroll, K. M. (2002b). Independent Tape Rater Guide. Unpublished psychotherapy tape rating manual.

- Ball S, Bachrach K, DeCarlo J, Farentionos C, Keen M, McSherry T. Characteristics of community clinicians trained to provide manual-guided therapy for substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:309–318. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barwick MA, Bennett LM, Johnson SN, McGowan J, Moore JE. Training health and mental health professionals in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(9):1786–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Tooley EM, Scott-Sheldon LA. Motivational interviewing for parent-child health interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatric Dentistry. 2015;37(3):254–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne NE, Newton AS, Gokiert R, Holt NL, Gehring ND, Perez A, Ball GDC. The application and reporting of motivational interviewing in managing adolescent obesity: A scoping review and stakeholder consultation. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2022;23(11):e13505. doi: 10.1111/obr.13505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Data and statistics on children’s mental health. Author.

- Choi KR, O’Malley CO, Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Tascione E, Bath E, Zima BT. A scoping review of police involvement in school crisis response for mental health emergencies. School Mental Health. 2022;14:431–439. doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09477-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss-Ehlers C, Serpell S, Weist MD. Making the case for culturally responsive school mental health. In: Clauss-Ehlers C, Serpell S, Weist M, editors. Handbook of culturally responsive school mental health: Advancing research, training, practice, and policy. Springer; 2013. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman NA, Parsons JP, Chabon B, Berg KM, Arnsten J, H. The development and feasibility of an intervention to improve antiretroviral adherence among HIV-positive patients receiving primary care in methadone clinics. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services. 2007;6(1/2):101–120. doi: 10.1300/J187v06n01_07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing CC, Jensen CD, Miller MB, Leffingwell TR. Meta-analysis of motivational interviewing for adolescent health behavior: Efficacy beyond substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(6):1212–1218. doi: 10.1037/a0036912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roten Y, Zimmermann G, Ortega D, Despland J-N. Meta-analysis of the effects of MI training on clinicians’ behavior. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Valle Nascimento, T. M., Rescinow, K., Nery, M., Brentani, A., Kaselitz, E., Agrawal, P., Mand, S., Heisler, M. (2017). A pilot study of a community health-agent led Type 2 diabetes self-management program using Motivational Interviewing-based approaches in a public primary care center in São Paulo, Brazil. BMC Health Services Research, 17(32), 1-10. 10.1186/s12913-016-1968-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Lee K, Cox S, Coifman J, Mayworm A, Lyon AR. Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2021;48(3):420–439. doi: 10.1007/s10488-020-01080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyehouse, J. (n.d). Confidence in motivational interviewing questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript.

- Easton GP. Resisting the “righting reflex” in conversations about COVID vaccine hesitancy. BMJ. 2021;373:n1566. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with disabilities education act (2004). Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/guid/paraguidance.pdf.

- Eklund K, DeMarchena SL, Rossen E, Izumi JT, Vaillancourt K, Rader Kelly S. Examining the role of school psychologists as providers of mental and behavioral health services. Psychology in the Schools. 2020;57:489–501. doi: 10.1002/pits.22323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund K, Meyer L, Splett J, Weist MD. Policies and practices to support school mental health. In: Levin B, Hanson AK, editors. Foundations of behavioral health. New York: Springer; 2020. pp. 139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Frey AJ, Cloud RN, Lee J, Small JW, Seeley JR, Feil EG, Walker HM, Golly A. The promise of motivational interviewing in school mental health. School Mental Health. 2011;3:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9048-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frey AJ, Lee J, Small JW, Sibley M, Sarno Owens J, Skidmore B, Johnson L, Bradshaw CP, Moyers TB. Mechanisms of motivational interviewing: A conceptual framework to guide practice and research. Prevention Science. 2021;22:689–700. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey AJ, Lee J, Small JW, Walker HM, Seeley JR. Motivational interviewing training and assessment system (MITAS) for school-based applications. Report on Emotional & Behavioral Disorders in Youth. 2017;17(4):86–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey A, Small JW, Lee J, Crosby SD, Seeley JR, Forness S, Walker HM. Home base: Participation, engagement, alliance, and social validity of a motivational parenting intervention. Children & Schools. 2019 doi: 10.1093/cs/cdz016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García, E., & Weiss, E. (2019). The teacher shortage is real, large and growing, and worse than we thought. Economic Policy Institute.

- García, E., & Weiss, E., (2020). COVID-19 and student performance, equity, and U.S. Education Policy: Lessons from pre-pandemic research to inform relief, recover, and rebuilding. Economic Policy Institute.

- Gisore P, Kaseje D, Were F, Ayuku D. Motivational interviewing intervention on health-seeking behaviors of pregnant women in western Kenya. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2014;19(2):144–156. doi: 10.1111/jabr.12020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant TM, Ernst CC, Streissguth AP. Intervention with high-risk alcohol and drug abusing mothers: I. Administrative strategies of the Seattle model of paraprofessional advocacy. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(1):1–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199901)27:1<1::AID-JCOP1>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graves JM, Abshire DA, Mackelprang JL, Dilley JA, Amiri S, Chacon CM, Mason A. Geographic disparities in the availability of mental health services in U.S. public schools. American journal of preventive medicine. 2023;64(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra LA, Rajan S, Roberts KJ. The implementation of mental health policies and practices in schools: An examination of school and state factors. Journal of School Health. 2019;89(4):328–338. doi: 10.1111/josh.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall K, Staiger PK, Simpson A, Best D, Lubman DI. After 30 years of dissemination, have we achieved sustained practice change in motivational interviewing? Addiction. 2016;111(7):1144–1150. doi: 10.1111/add.13014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MJ, Flitner AM, Kornbluh ME, Thompson DC, Davis AL, Lanza-Gregory J, McQuillin SD, Gonzalez JE, Strait GG. Combining MTSS and community-based mentoring programs. School Psychology Review. 2021 doi: 10.1080/2372966x.2021.1922937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MJ, Sable R, Gupta A, Boddu J, McQuillin SD. Adapting a school-based motivational interviewing mentoring program for use in India. School Psychology International. 2022;43(2):196–216. doi: 10.1177/01430343221080782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MJ, Sung JY, McQuillin SD, Schleider JL. Expanding the reach of psychosocial services for youth: Untapped potential of mentors and single session interventions. Journal of Community Psychology. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jcop.22927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen E, Orlinsky DE. Psychotherapists’ personal identities, theoretical orientations, and professional relationships: Elective affinity and role adjustment as modes of congruence. Psychotherapy Research. 2013;23(6):718–731. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.814926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman K, Reinke W, Frey AJ. Motivational Interviewing in Schools: Strategies for Engaging Parents, Teachers, and Students. 2. Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM. Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(5):629–645. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Education Sciences. (2022). Roughly Half of Public Schools Report That They Can Effectively Provide Mental Health Services to All Students in Need.https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/05_31_2022_2.asp

- Kilgus SP, Eklund K, von der Embse NP, Weist M, Barber AJ, Kaul M, Dodge S. Structural validity and reliability of social, academic, and emotional behavior risk screener-student rating scale scores: A replication study. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 2021;46(4):259–269. doi: 10.1177/1534508420909527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leffingwell TR. Motivational interviewing knowledge and attitudes test (MIKAT) for evaluation of training outcomes. MINUET. 2006;13:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liang R, Ren H, Cao R, Hu Y, Qin Z, Li C, Mei S. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2020;91:841–852. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;93(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Campbell TC. Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C. Training in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Schumacher JA, Noble JJ, Bonnell MA. Teaching motivational interviewing to undergraduates: Evaluation of three approaches. Teaching of Psychology. 2013;40(3):242–245. doi: 10.1177/0098628313487450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maggin DM, Wehby JH, Farmer TW, Brooks DS. Intensive interventions for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Issues, theory, and future directions. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2016;24(3):127–137. doi: 10.1177/1063426616661498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowski AK, Owens RL, LaCaille RA, Clinton-Lisell V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational interviewing training effectiveness among students-in-training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1037/tep0000363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMaster F, Resnicow K. Validation of the one pass measure for motivational interviewing competence. Patient Education and Counseling. 2015;98(4):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillin SD, Hagler M, Werntz A, Rhodes JE. Paraprofessional youth mentoring: A framework for integrating youth mentoring with helping institutions and professions. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2021;69:201–220. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillin SD, Lyons MD, Becker KD, Hart MJ, Cohen K. Strengthening and expanding child services in low resource communities: The role of task-shifting and just-in-time training. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2019;63(3–4):355–365. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillin SD, McDaniel HL. Pilot randomized trial of brief school-based mentoring for middle school students with elevated disruptive behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2021;1483(1):127–141. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillin S, Smith B, Strait G, Ingram A. Brief instrumental school-based mentoring for first and second year middle school students: A randomized evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;43(7):885–889. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Motivational interviewing skill code (MISC) coder’s manual. University of New Mexico; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Moyers TB. Eight stages in learning motivational interviewing. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions. 2006;5:3–7. doi: 10.1300/J188v05n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moon J, Williford A, Mendenhall A. Educators’ perceptions of youth mental health: Implications for training and the promotion of mental health services in schools. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;73:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]